- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- Healing with Heart: Monica Patino’s Mission in Support of Latinx Families

- A Visit From the 49ers Scores Smiles at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford

- Beat the Heat: Keep Kids Safe in the Autumn Sun

- Wildfires: Health Risks and How to Keep Children Safe

- Cause for Celebration—and Concern

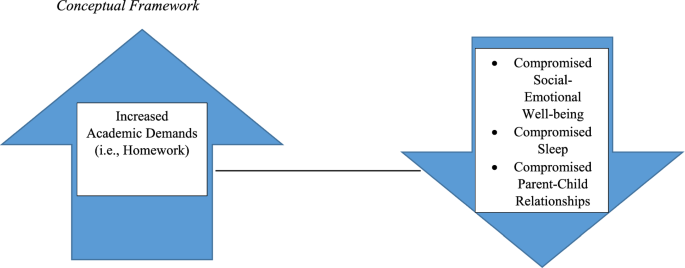

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford School of Medicine

- Stanford Health Care

- Stanford University

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

School Stress Takes A Toll On Health, Teens And Parents Say

Patti Neighmond

Colleen Frainey, 16, of Tualatin, Ore., cut back on advanced placement classes in her junior year because the stress was making her physically ill. Toni Greaves for NPR hide caption

Colleen Frainey, 16, of Tualatin, Ore., cut back on advanced placement classes in her junior year because the stress was making her physically ill.

When high school junior Nora Huynh got her report card, she was devastated to see that she didn't get a perfect 4.0.

Nora "had a total meltdown, cried for hours," her mother, Jennie Huynh of Alameda, Calif., says. "I couldn't believe her reaction."

Nora is doing college-level work, her mother says, but many of her friends are taking enough advanced classes to boost their grade-point averages above 4.0. "It breaks my heart to see her upset when she's doing so awesome and going above and beyond."

And the pressure is taking a physical toll, too. At age 16, Nora is tired, is increasingly irritated with her siblings and often suffers headaches, her mother says.

Teens Talk Stress

When NPR asked on Facebook if stress is an issue for teenagers, they spoke loud and clear:

- "Academic stress has been a part of my life ever since I can remember," wrote Bretta McCall, 16, of Seattle. "This year I spend about 12 hours a day on schoolwork. I'm home right now because I was feeling so sick from stress I couldn't be at school. So as you can tell, it's a big part of my life!"

- "At the time of writing this, my weekend assignments include two papers, a PowerPoint to go with a 10-minute presentation, studying for a test and two quizzes, and an entire chapter (approximately 40 pages) of notes in a college textbook," wrote Connor West of New Jersey.

- "It's a problem that's basically brushed off by most people," wrote Kelly Farrell in Delaware. "There's this mentality of, 'You're doing well, so why are you complaining?' " She says she started experiencing symptoms of stress in middle school, and was diagnosed with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in high school.

- "Parents are the worst about all of this," writes Colin Hughes of Illinois. "All I hear is, 'Work harder, you're a smart kid, I know you have it in you, and if you want to go to college you need to work harder.' It's a pain."

Parents are right to be worried about stress and their children's health, says Mary Alvord , a clinical psychologist in Maryland and public education coordinator for the American Psychological Association.

"A little stress is a good thing," Alvord says. "It can motivate students to be organized. But too much stress can backfire."

Almost 40 percent of parents say their high-schooler is experiencing a lot of stress from school, according to a new NPR poll conducted with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard School of Public Health. In most cases, that stress is from academics, not social issues or bullying, the poll found. (See the full results here .)

Homework was a leading cause of stress, with 24 percent of parents saying it's an issue.

Teenagers say they're suffering, too. A survey by the American Psychological Association found that nearly half of all teens — 45 percent — said they were stressed by school pressures.

Chronic stress can cause a sense of panic and paralysis, Alvord says. The child feels stuck, which only adds to the feeling of stress.

Parents can help put the child's distress in perspective, particularly when they get into what Alvord calls catastrophic "what if" thinking: "What if I get a bad grade, then what if that means I fail the course, then I'll never get into college."

Then move beyond talking and do something about it.

Colleen pets her horse, Bishop. They had been missing out on rides together because of homework. Toni Greaves for NPR hide caption

Colleen pets her horse, Bishop. They had been missing out on rides together because of homework.

That's what 16-year-old Colleen Frainey of Tualatin, Ore., did. As a sophomore last year, she was taking all advanced courses. The pressure was making her sick. "I didn't feel good, and when I didn't feel good I felt like I couldn't do my work, which would stress me out more," she says.

Mom Abigail Frainey says, "It was more than we could handle as a family."

With encouragement from her parents, Colleen dropped one of her advanced courses. The family's decision generated disbelief from other parents. "Why would I let her take the easy way out?" Abigail Frainey heard.

But she says dialing down on academics was absolutely the right decision for her child. Colleen no longer suffers headaches or stomachaches. She's still in honors courses, but the workload this year is manageable.

Even better, Colleen now has time to do things she never would have considered last year, like going out to dinner with the family on a weeknight, or going to the barn to ride her horse, Bishop.

Psychologist Alvord says a balanced life should be the goal for all families. If a child is having trouble getting things done, parents can help plan the week, deciding what's important and what's optional. "Just basic time management — that will help reduce the stress."

- Children's Health

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

Is Homework Necessary? Education Inequity and Its Impact on Students

The Problem with Homework: It Highlights Inequalities

How much homework is too much homework, when does homework actually help, negative effects of homework for students, how teachers can help.

Schools are getting rid of homework from Essex, Mass., to Los Angeles, Calif. Although the no-homework trend may sound alarming, especially to parents dreaming of their child’s acceptance to Harvard, Stanford or Yale, there is mounting evidence that eliminating homework in grade school may actually have great benefits , especially with regard to educational equity.

In fact, while the push to eliminate homework may come as a surprise to many adults, the debate is not new . Parents and educators have been talking about this subject for the last century, so that the educational pendulum continues to swing back and forth between the need for homework and the need to eliminate homework.

One of the most pressing talking points around homework is how it disproportionately affects students from less affluent families. The American Psychological Association (APA) explained:

“Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs.”

[RELATED] How to Advance Your Career: A Guide for Educators >>

While students growing up in more affluent areas are likely playing sports, participating in other recreational activities after school, or receiving additional tutoring, children in disadvantaged areas are more likely headed to work after school, taking care of siblings while their parents work or dealing with an unstable home life. Adding homework into the mix is one more thing to deal with — and if the student is struggling, the task of completing homework can be too much to consider at the end of an already long school day.

While all students may groan at the mention of homework, it may be more than just a nuisance for poor and disadvantaged children, instead becoming another burden to carry and contend with.

Beyond the logistical issues, homework can negatively impact physical health and stress — and once again this may be a more significant problem among economically disadvantaged youth who typically already have a higher stress level than peers from more financially stable families .

Yet, today, it is not just the disadvantaged who suffer from the stressors that homework inflicts. A 2014 CNN article, “Is Homework Making Your Child Sick?” , covered the issue of extreme pressure placed on children of the affluent. The article looked at the results of a study surveying more than 4,300 students from 10 high-performing public and private high schools in upper-middle-class California communities.

“Their findings were troubling: Research showed that excessive homework is associated with high stress levels, physical health problems and lack of balance in children’s lives; 56% of the students in the study cited homework as a primary stressor in their lives,” according to the CNN story. “That children growing up in poverty are at-risk for a number of ailments is both intuitive and well-supported by research. More difficult to believe is the growing consensus that children on the other end of the spectrum, children raised in affluence, may also be at risk.”

When it comes to health and stress it is clear that excessive homework, for children at both ends of the spectrum, can be damaging. Which begs the question, how much homework is too much?

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association recommend that students spend 10 minutes per grade level per night on homework . That means that first graders should spend 10 minutes on homework, second graders 20 minutes and so on. But a study published by The American Journal of Family Therapy found that students are getting much more than that.

While 10 minutes per day doesn’t sound like much, that quickly adds up to an hour per night by sixth grade. The National Center for Education Statistics found that high school students get an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, a figure that is much too high according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It is also to be noted that this figure does not take into consideration the needs of underprivileged student populations.

In a study conducted by the OECD it was found that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance .” That means that by asking our children to put in an hour or more per day of dedicated homework time, we are not only not helping them, but — according to the aforementioned studies — we are hurting them, both physically and emotionally.

What’s more is that homework is, as the name implies, to be completed at home, after a full day of learning that is typically six to seven hours long with breaks and lunch included. However, a study by the APA on how people develop expertise found that elite musicians, scientists and athletes do their most productive work for about only four hours per day. Similarly, companies like Tower Paddle Boards are experimenting with a five-hour workday, under the assumption that people are not able to be truly productive for much longer than that. CEO Stephan Aarstol told CNBC that he believes most Americans only get about two to three hours of work done in an eight-hour day.

In the scope of world history, homework is a fairly new construct in the U.S. Students of all ages have been receiving work to complete at home for centuries, but it was educational reformer Horace Mann who first brought the concept to America from Prussia.

Since then, homework’s popularity has ebbed and flowed in the court of public opinion. In the 1930s, it was considered child labor (as, ironically, it compromised children’s ability to do chores at home). Then, in the 1950s, implementing mandatory homework was hailed as a way to ensure America’s youth were always one step ahead of Soviet children during the Cold War. Homework was formally mandated as a tool for boosting educational quality in 1986 by the U.S. Department of Education, and has remained in common practice ever since.

School work assigned and completed outside of school hours is not without its benefits. Numerous studies have shown that regular homework has a hand in improving student performance and connecting students to their learning. When reviewing these studies, take them with a grain of salt; there are strong arguments for both sides, and only you will know which solution is best for your students or school.

Homework improves student achievement.

- Source: The High School Journal, “ When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math ,” 2012.

- Source: IZA.org, “ Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement? ,” 2014. **Note: Study sample comprised only high school boys.

Homework helps reinforce classroom learning.

- Source: “ Debunk This: People Remember 10 Percent of What They Read ,” 2015.

Homework helps students develop good study habits and life skills.

- Sources: The Repository @ St. Cloud State, “ Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement ,” 2017; Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

- Source: Journal of Advanced Academics, “ Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework ,” 2011.

Homework allows parents to be involved with their children’s learning.

- Parents can see what their children are learning and working on in school every day.

- Parents can participate in their children’s learning by guiding them through homework assignments and reinforcing positive study and research habits.

- Homework observation and participation can help parents understand their children’s academic strengths and weaknesses, and even identify possible learning difficulties.

- Source: Phys.org, “ Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework ,” 2018.

While some amount of homework may help students connect to their learning and enhance their in-class performance, too much homework can have damaging effects.

Students with too much homework have elevated stress levels.

- Source: USA Today, “ Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In ,” 2021.

- Source: Stanford University, “ Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework ,” 2014.

Students with too much homework may be tempted to cheat.

- Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education, “ High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame ,” 2010.

- Source: The American Journal of Family Therapy, “ Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background ,” 2015.

Homework highlights digital inequity.

- Sources: NEAToday.org, “ The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’ ,” 2016; CNET.com, “ The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind ,” 2021.

- Source: Investopedia, “ Digital Divide ,” 2022; International Journal of Education and Social Science, “ Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework ,” 2015.

- Source: World Economic Forum, “ COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it ,” 2021.

Homework does not help younger students.

- Source: Review of Educational Research, “ Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003 ,” 2006.

To help students find the right balance and succeed, teachers and educators must start the homework conversation, both internally at their school and with parents. But in order to successfully advocate on behalf of students, teachers must be well educated on the subject, fully understanding the research and the outcomes that can be achieved by eliminating or reducing the homework burden. There is a plethora of research and writing on the subject for those interested in self-study.

For teachers looking for a more in-depth approach or for educators with a keen interest in educational equity, formal education may be the best route. If this latter option sounds appealing, there are now many reputable schools offering online master of education degree programs to help educators balance the demands of work and family life while furthering their education in the quest to help others.

YOU’RE INVITED! Watch Free Webinar on USD’s Online MEd Program >>

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Homework could have an impact on kids’ health. Should schools ban it?

Professor of Education, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Gerald K. LeTendre has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Reformers in the Progressive Era (from the 1890s to 1920s) depicted homework as a “sin” that deprived children of their playtime . Many critics voice similar concerns today.

Yet there are many parents who feel that from early on, children need to do homework if they are to succeed in an increasingly competitive academic culture. School administrators and policy makers have also weighed in, proposing various policies on homework .

So, does homework help or hinder kids?

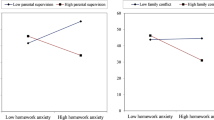

For the last 10 years, my colleagues and I have been investigating international patterns in homework using databases like the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) . If we step back from the heated debates about homework and look at how homework is used around the world, we find the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher social inequality.

Does homework result in academic success?

Let’s first look at the global trends on homework.

Undoubtedly, homework is a global phenomenon ; students from all 59 countries that participated in the 2007 Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) reported getting homework. Worldwide, only less than 7% of fourth graders said they did no homework.

TIMSS is one of the few data sets that allow us to compare many nations on how much homework is given (and done). And the data show extreme variation.

For example, in some nations, like Algeria, Kuwait and Morocco, more than one in five fourth graders reported high levels of homework. In Japan, less than 3% of students indicated they did more than four hours of homework on a normal school night.

TIMSS data can also help to dispel some common stereotypes. For instance, in East Asia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan – countries that had the top rankings on TIMSS average math achievement – reported rates of heavy homework that were below the international mean.

In the Netherlands, nearly one out of five fourth graders reported doing no homework on an average school night, even though Dutch fourth graders put their country in the top 10 in terms of average math scores in 2007.

Going by TIMSS data, the US is neither “ A Nation at Rest” as some have claimed, nor a nation straining under excessive homework load . Fourth and eighth grade US students fall in the middle of the 59 countries in the TIMSS data set, although only 12% of US fourth graders reported high math homework loads compared to an international average of 21%.

So, is homework related to high academic success?

At a national level, the answer is clearly no. Worldwide, homework is not associated with high national levels of academic achievement .

But, the TIMSS can’t be used to determine if homework is actually helping or hurting academic performance overall , it can help us see how much homework students are doing, and what conditions are associated with higher national levels of homework.

We have typically found that the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher levels of social inequality – not hallmarks that most countries would want to emulate.

Impact of homework on kids

TIMSS data also show us how even elementary school kids are being burdened with large amounts of homework.

Almost 10% of fourth graders worldwide (one in 10 children) reported spending multiple hours on homework each night. Globally, one in five fourth graders report 30 minutes or more of homework in math three to four times a week.

These reports of large homework loads should worry parents, teachers and policymakers alike.

Empirical studies have linked excessive homework to sleep disruption , indicating a negative relationship between the amount of homework, perceived stress and physical health.

What constitutes excessive amounts of homework varies by age, and may also be affected by cultural or family expectations. Young adolescents in middle school, or teenagers in high school, can study for longer duration than elementary school children.

But for elementary school students, even 30 minutes of homework a night, if combined with other sources of academic stress, can have a negative impact . Researchers in China have linked homework of two or more hours per night with sleep disruption .

Even though some cultures may normalize long periods of studying for elementary age children, there is no evidence to support that this level of homework has clear academic benefits . Also, when parents and children conflict over homework, and strong negative emotions are created, homework can actually have a negative association with academic achievement.

Should there be “no homework” policies?

Administrators and policymakers have not been reluctant to wade into the debates on homework and to formulate policies . France’s president, Francois Hollande, even proposed that homework be banned because it may have inegaliatarian effects.

However, “zero-tolerance” homework policies for schools, or nations, are likely to create as many problems as they solve because of the wide variation of homework effects. Contrary to what Hollande said, research suggests that homework is not a likely source of social class differences in academic achievement .

Homework, in fact, is an important component of education for students in the middle and upper grades of schooling.

Policymakers and researchers should look more closely at the connection between poverty, inequality and higher levels of homework. Rather than seeing homework as a “solution,” policymakers should question what facets of their educational system might impel students, teachers and parents to increase homework loads.

At the classroom level, in setting homework, teachers need to communicate with their peers and with parents to assure that the homework assigned overall for a grade is not burdensome, and that it is indeed having a positive effect.

Perhaps, teachers can opt for a more individualized approach to homework. If teachers are careful in selecting their assignments – weighing the student’s age, family situation and need for skill development – then homework can be tailored in ways that improve the chance of maximum positive impact for any given student.

I strongly suspect that when teachers face conditions such as pressure to meet arbitrary achievement goals, lack of planning time or little autonomy over curriculum, homework becomes an easy option to make up what could not be covered in class.

Whatever the reason, the fact is a significant percentage of elementary school children around the world are struggling with large homework loads. That alone could have long-term negative consequences for their academic success.

- Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)

- Elementary school

- Academic success

Editorial Internship

Research Fellow in Dark Matter Particle Phenomenology

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- NeuroLaunch

The Dark Side of Homework: Why It’s Harmful and What the Statistics Say

- Stress in Education

- NeuroLaunch editorial team

- August 18, 2024

- Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

Pencils down, backpacks zipped—the after-school battle that’s eroding our children’s well-being and widening educational gaps has a name: homework. This seemingly innocuous academic tradition has become a contentious issue in recent years, sparking debates among educators, parents, and policymakers alike. As we delve into the dark side of homework, we’ll explore its history, examine its impact on students, and consider alternatives that could reshape the future of education.

The practice of assigning homework has been a cornerstone of education for centuries, with its roots tracing back to the early days of formal schooling. Initially conceived as a way to reinforce classroom learning and instill discipline, homework has evolved into a complex and often controversial aspect of modern education. Today, the homework debate rages on, with proponents arguing for its necessity in academic achievement and critics pointing to its detrimental effects on student well-being and family life.

The importance of examining homework’s impact on students cannot be overstated. As our understanding of child development and learning processes advances, it’s crucial to reevaluate long-standing educational practices. The homework question touches on fundamental issues of equity, mental health, and the very purpose of education itself. By critically analyzing the role of homework in our educational system, we can work towards creating more effective and supportive learning environments for all students.

The Negative Effects of Homework on Student Well-being

One of the most significant concerns surrounding homework is its impact on student well-being. The Alarming Reality: What Percent of Students Are Stressed by Homework? reveals that a staggering number of students experience stress and anxiety related to their after-school assignments. This stress can manifest in various ways, from physical symptoms like headaches and stomach aches to emotional distress and feelings of overwhelm.

The pressure to complete homework often comes at the expense of valuable family time and social interactions. As students struggle to balance their academic responsibilities with extracurricular activities and personal interests, family dinners become rushed affairs, and quality time with loved ones becomes a luxury. This erosion of family connections can have long-lasting effects on a child’s emotional development and sense of security.

Moreover, the time-consuming nature of homework can significantly impact students’ sleep patterns and physical health. Late nights spent completing assignments lead to sleep deprivation, which in turn affects cognitive function, mood regulation, and overall well-being. Understanding Homeostatic Imbalance and Stress: A Comprehensive Guide with Worksheet Answers sheds light on how disrupted sleep patterns can contribute to a cascade of health issues.

Perhaps most concerning is the potential for homework to diminish students’ interest in learning and contribute to academic burnout. When learning becomes synonymous with tedious, repetitive tasks, students may lose their natural curiosity and enthusiasm for education. This disengagement can have far-reaching consequences, affecting not only academic performance but also future career aspirations and lifelong learning attitudes.

Homework and Academic Performance: A Surprising Relationship

Contrary to popular belief, the relationship between homework and academic achievement is not as straightforward as one might assume. Numerous studies have shown a limited correlation between homework and improved performance, particularly for younger students. This surprising finding challenges the long-held assumption that more homework inevitably leads to better academic outcomes.

The law of diminishing returns applies to homework as well. While some homework may be beneficial, there comes a point where additional assignments yield little to no academic benefit. This threshold varies depending on the student’s age, with high school students generally able to handle more homework than elementary or middle school students. However, even for older students, excessive homework can lead to burnout and decreased motivation.

It’s important to note that the effectiveness of homework differs across age groups. For younger children, homework has been shown to have minimal impact on academic achievement. As students progress through middle and high school, homework can become more beneficial, but only when it’s carefully designed and appropriately challenging.

The quality of homework assignments is far more important than quantity. Meaningful, engaging tasks that reinforce classroom learning or encourage independent exploration are more likely to yield positive results than rote memorization or busywork. Educators and policymakers must focus on creating homework policies that prioritize quality over quantity, ensuring that out-of-school assignments truly contribute to student learning and growth.

Stress and Homework: What the Statistics Reveal

The statistics surrounding homework-related stress are alarming. Studies have consistently shown that a high percentage of students report experiencing stress and anxiety due to homework demands. In some surveys, as many as 70-80% of students indicate that homework is a significant source of stress in their lives.

When comparing stress levels across different educational systems, it becomes clear that homework practices vary widely. Countries with high-performing education systems, such as Finland, often assign less homework than their counterparts, challenging the notion that more homework equates to better academic outcomes. These international comparisons provide valuable insights into alternative approaches to education that prioritize student well-being alongside academic achievement.

The long-term effects of academic stress on mental health are a growing concern among researchers and mental health professionals. Chronic stress during childhood and adolescence can lead to increased risk of anxiety disorders, depression, and other mental health issues later in life. Overcoming Math Stress: Strategies for Confidence and Success in Mathematics explores how subject-specific stress, such as math anxiety, can have lasting impacts on students’ academic and personal lives.

Interestingly, gender differences in homework-related stress have been observed in various studies. Girls often report higher levels of stress and anxiety related to homework compared to boys. This disparity may be attributed to societal expectations, differences in coping strategies, or other factors that require further investigation to fully understand and address.

The Equity Issue: How Homework Perpetuates Inequality

One of the most troubling aspects of homework is its potential to exacerbate existing educational inequalities. Students from different socioeconomic backgrounds often face vastly different circumstances when it comes to completing homework assignments. Disparities in home resources and support can significantly impact a student’s ability to succeed academically.

For students from low-income families, homework can present numerous challenges. Limited access to technology, quiet study spaces, or academic resources can make completing assignments difficult or impossible. Parents working multiple jobs may have less time to assist with homework, putting their children at a disadvantage compared to peers with more available parental support. The Pervasive Daily Stress of Poverty: Unraveling Its Impact on Brain Development highlights how these socioeconomic factors can have far-reaching effects on a child’s cognitive development and academic potential.

Homework’s role in widening the achievement gap is a critical concern. As students from privileged backgrounds benefit from additional resources and support, those from disadvantaged backgrounds may fall further behind. This cycle can perpetuate and even amplify existing inequalities, making it increasingly difficult for students from low-income families to achieve academic success and social mobility.

Cultural biases in homework assignments can further compound these issues. Assignments that assume certain cultural knowledge or experiences may inadvertently disadvantage students from diverse backgrounds. Educators must be mindful of these potential biases and strive to create inclusive, culturally responsive homework practices that support all students’ learning and growth.

Alternatives to Traditional Homework

As the drawbacks of traditional homework become increasingly apparent, educators and researchers are exploring alternative approaches to out-of-school learning. Project-based learning approaches offer one promising alternative, encouraging students to engage in long-term, interdisciplinary projects that foster creativity, critical thinking, and real-world problem-solving skills.

The flipped classroom model is another innovative approach that reimagines the role of homework. In this model, students engage with instructional content at home through videos or readings, while class time is devoted to collaborative problem-solving and hands-on activities. This approach allows for more personalized instruction and support during school hours, potentially reducing the need for extensive homework assignments.

Personalized learning strategies, facilitated by advancements in educational technology, offer yet another alternative to traditional homework. These approaches tailor assignments to individual students’ needs, interests, and learning styles, potentially increasing engagement and reducing unnecessary stress. Gloria’s Study Challenge: The Impact of One More Hour and the Hidden Costs of Interruptions explores how personalized study strategies can impact learning outcomes.

Emphasizing in-class practice and collaboration is another way to reduce the burden of homework while still promoting learning and skill development. By providing more opportunities for guided practice during school hours, teachers can ensure that students receive immediate feedback and support, potentially reducing the need for extensive at-home practice.

Conclusion: Rethinking Homework for a Better Educational Future

As we’ve explored throughout this article, the traditional approach to homework is fraught with challenges. From its negative impact on student well-being to its potential to exacerbate educational inequalities, homework as we know it may be doing more harm than good. The limited correlation between homework and academic achievement, particularly for younger students, further calls into question the value of extensive out-of-school assignments.

A balanced approach to out-of-school learning is crucial. While some form of independent practice and exploration outside of school hours may be beneficial, it’s essential to consider the quality, quantity, and purpose of these assignments. Educators and policymakers must prioritize student well-being, equity, and meaningful learning experiences when developing homework policies.

The need for education reform and policy changes is clear. Is Homework Necessary? Examining the Debate and Its Impact on Student Well-being delves deeper into this question, challenging long-held assumptions about the role of homework in education. As we move forward, it’s crucial to consider alternative approaches that support student learning without sacrificing their mental health, family time, or love of learning.

Encouraging further research and discussion on homework practices is essential for developing evidence-based policies that truly serve students’ best interests. By critically examining our current practices and remaining open to innovative approaches, we can work towards an educational system that nurtures well-rounded, engaged, and lifelong learners.

As we conclude this exploration of the dark side of homework, it’s clear that the time has come to reevaluate our approach to out-of-school learning. By addressing the stress, inequity, and limited benefits associated with traditional homework, we can pave the way for a more effective, equitable, and student-centered education system. The Power of Playtime: How Recess Reduces Stress in Students reminds us of the importance of balance in education, highlighting the need for policies that support both academic growth and overall well-being.

The homework debate is far from over, but by continuing to question, research, and innovate, we can work towards educational practices that truly serve the needs of all students. As parents, educators, and policymakers, it’s our responsibility to ensure that our children’s education nurtures their curiosity, supports their well-being, and prepares them for success in an ever-changing world. Let’s reimagine homework not as a nightly battle, but as an opportunity for meaningful learning, growth, and discovery.

References:

1. Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 1-62.

2. Galloway, M., Conner, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81(4), 490-510.

3. OECD (2014). Does homework perpetuate inequities in education? PISA in Focus, No. 46, OECD Publishing, Paris.

4. Kralovec, E., & Buell, J. (2000). The end of homework: How homework disrupts families, overburdens children, and limits learning. Beacon Press.

5. Marzano, R. J., & Pickering, D. J. (2007). Special topic: The case for and against homework. Educational Leadership, 64(6), 74-79.

6. Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs. ASCD.

7. Kohn, A. (2006). The homework myth: Why our kids get too much of a bad thing. Da Capo Press.

8. Pressman, R. M., Sugarman, D. B., Nemon, M. L., Desjarlais, J., Owens, J. A., & Schettini-Evans, A. (2015). Homework and family stress: With consideration of parents’ self confidence, educational level, and cultural background. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 43(4), 297-313.

9. Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

10. Sahlberg, P. (2015). Finnish lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? Teachers College Press.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

About NeuroLaunch

- Copyright Notice

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise With Us

- Mental Health

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Barriers Associated with the Implementation of Homework in Youth Mental Health Treatment and Potential Mobile Health Solutions

Brian e bunnell, lynne s nemeth, leslie a lenert, nikolaos kazantzis, esther deblinger, kristen a higgins, kenneth j ruggiero.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Brian Bunnell], [Lynne Nemeth], [Kenneth Ruggiero], and [Kristen Higgins]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Brian Bunnell] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Correspondence: Brian E. Bunnell, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, 3515 E. Fletcher Ave Tampa, FL 33613; Phone: (813) 794-8607; [email protected] .

Issue date 2021 Apr.

Background:

Homework, or between-session practice of skills learned during therapy, is integral to effective youth mental health TREATMENTS. However, homework is often under-utilized by providers and patients due to many barriers, which might be mitigated via m Health solutions.

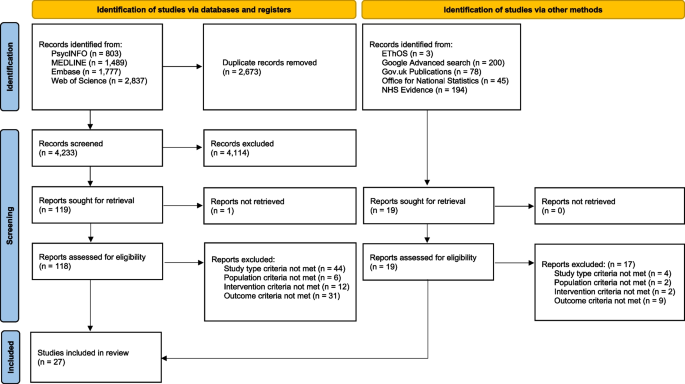

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with nationally certified trainers in Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT; n =21) and youth TF-CBT patients ages 8–17 ( n =15) and their caregivers ( n =12) to examine barriers to the successful implementation of homework in youth mental health treatment and potential m Health solutions to those barriers.

The results indicated that many providers struggle to consistently develop, assign, and assess homework exercises with their patients. Patients are often difficult to engage and either avoid or have difficulty remembering to practice exercises, especially given their busy/chaotic home lives. Trainers and families had positive views and useful suggestions for m Health solutions to these barriers in terms of functionality (e.g., reminders, tracking, pre-made homework exercises, rewards) and user interface (e.g., easy navigation, clear instructions, engaging activities).

Conclusions:

This study adds to the literature on homework barriers and potential m Health solutions to those barriers, which is largely based on recommendations from experts in the field. The results aligned well with this literature, providing additional support for existing recommendations, particularly as they relate to treatment with youth and caregivers.

Keywords: Homework, Barriers, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Technology, m Health

Introduction

Homework, or between-session practice of skills learned during therapy, is one of the most integral, yet underutilized components of high-quality, evidence-based mental health care ( Kazantzis & Deane, 1999 ). Homework activities (e.g., self-monitoring, relaxation, exposure, parent behavior management) are assigned by providers in-session and completed by patients between sessions with the goal of “practicing” therapeutic skills in the environment where they will be most needed ( Kazantzis, Deane, Ronan, & L’Abate, 2005 ). There are numerous benefits to the implementation of homework during mental health treatment ( Kazantzis et al., 2016 ; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2004 ). Homework enables the generalization of skills and behaviors learned during therapy, facilitates treatment processes, provides continuity between sessions, allows providers to better grasp patients’ learning, and strengthens that learning, leading to improved maintenance of treatment gains ( Hudson & Kendall, 2002 ; Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004 ). Meta-analytic and systematic reviews have shown that homework use by providers and adherence by patients predict increased treatment engagement, decreased treatment dropout, and medium-to-large effects on improvements in clinical outcomes for use (Cohen’s d =.48–.77) and adherence ( d =.45–.54) ( Hudson & Kendall, 2002 ; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000 ; Kazantzis & Lampropoulos, 2002 ; Kazantzis, Whittington, & Dattilio, 2010 ; Mausbach, Moore, Roesch, Cardenas, & Patterson, 2010 ; Scheel et al., 2004 ; Sukhodolsky, Kassinove, & Gorman, 2004 ). Simply put, 68% vs . 32% of patients can be expected to improve when therapy involves homework ( Kazantzis et al., 2010 ).

Despite its many benefits, homework is implemented with variable effectiveness in mental health treatment. Only 68% of general mental health providers and ~55% of family providers report using homework “often” to “almost always” ( Dattilio, Kazantzis, Shinkfield, & Carr, 2011 ; Kazantzis, Lampropoulos, & Deane, 2005 ). Further, providers report using homework in an average of 57% of sessions, although this rate is higher for CBT practitioners (66%) vs . non-CBT practitioners (48%). Moreover, only 25% of providers report using expert recommended systematic procedures for recommending homework (i.e., specifying frequency, duration, and location; writing down homework assignments for patients) ( Kazantzis & Deane, 1999 ). A national survey revealed that 93% or general mental health providers estimate rates of patient adherence to homework to be low to moderate ( Kazantzis, Lampropoulos, et al., 2005 ), and research studies report low to moderate rates of youth/caregiver adherence during treatment (i.e., ~39–63%; ( Berkovits, O’Brien, Carter, & Eyberg, 2010 ; Clarke et al., 1992 ; Danko, Brown, Van Schoick, & Budd, 2016 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Gaynor, Lawrence, & Nelson-Gray, 2006 ; Helbig & Fehm, 2004 ; Lyon & Budd, 2010 ; Simons et al., 2012 ).

Numerous barriers to the successful implementation of homework during mental health treatment have largely been suggested by experts in the field, rather than specifically measured ( Dattilio et al., 2011 ), and have generally been classified as occurring on the provider-, patient-, task-, and environmental-level ( Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Provider-level barriers can relate to the therapeutic relationship and the degree to which a collaborative approach is used, provider beliefs about homework and the patient’s adherence, and providers’ ability to effectively design homework tasks ( Callan et al., 2012 ; Coon, Rabinowitz, Thompson, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2005 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Patient-level barriers can include patient avoidance and symptomatology, negative beliefs toward the task, not understanding the rationale or how to do the task, forgetting, and beliefs about their ability to complete homework tasks. ( Bru, Solholm, & Idsoe, 2013 ; Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ; Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ; Leahy, 2002 ). Relatedly, core beliefs central to the patients’ psychopathology can be activated during homework–thereby triggering withdrawal and avoidance patterns ( Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Task-level barriers include poor match between tasks and therapy goals, tasks that are perceived as vague or unclear, tasks that are perceived as too difficult or demanding in terms of time or effort, tasks being viewed as boring, and general aversiveness of the idea of completing homework ( Bru et al., 2013 ; Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ). Environmental factors have been noted to include practical obstacles, lack of family/caregiver support, dysfunctional home environments, lack of time due to busy schedules, and lack of reward or reinforcement ( Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ).

The advancement and ubiquitousness of technologies such as m Health resources (e.g., mobile- and web-based apps) provide a tremendous opportunity to overcome barriers to homework use and adherence and resultantly, improve the quality of mental health treatment. m Health solutions to improve access and quality of care, have been widely investigated, are effective in facilitating behavior change, practical, desired by patients and providers, and available at low cost ( Amstadter, Broman-Fulks, Zinzow, Ruggiero, & Cercone, 2009 ; Boschen & Casey, 2008 ; Donker et al., 2013 ; Ehrenreich, Righter, Rocke, Dixon, & Himelhoch, 2011 ; Hanson et al., 2014 ; Heron & Smyth, 2010 ; Krebs & Duncan, 2015 ; Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, 2011 ; Ruggiero, Saunders, Davidson, Cook, & Hanson, 2017 ). Existing m Health resources include features that can support homework implementation (e.g., voice and SMS reminders and feedback, self-monitoring and assessment, and modules and activities that can be used to facilitate between-session practice; Bakker, Kazantzis, Rickwood, & Rickard, 2016 ; Tang & Kreindler, 2017 ), but these resources were not designed with the express intention of addressing barriers to homework implementation, particularly for youth and family patient populations.

The extant literature on barriers to homework implementation is limited in that it is largely based on expert recommendations. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to explore provider, youth, and caregiver patient perspectives on barriers to the successful implementation of homework during youth mental health treatment. Further, m Health solutions to those barriers have not been explored, especially for youth and family patients. Thus, the second and third aims of this study were to obtain suggestions for m Health solutions to homework barriers and explore perceptions on the benefits and challenges associated with those m Health solutions.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to enrolling any participants in the study. The approach for this study was based on the constructivist grounded theory, which acknowledges the researcher’s prior knowledge and influence in the process and supports and guides conceptual framework development to understand interrelations between constructs ( Charmaz, 2006 ). This qualitative study used a thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews in a sample of nationally certified trainers in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TFCBT; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2017 ), youth who had engaged in TF-CBT, and their caregivers. The initial goal was to conduct interviews with 15–20 interviewees in each group to achieve theoretical saturation (i.e., no new information was derived), consistent with a prior study by members of the research team which used similar semi-structured interviews with national TF-CBT trainers ( Hanson et al., 2014 ), and recommendations by Morse (2000) given the relatively narrow scope and clear nature of the study. Interviews were conducted until interviewers and the study lead determined that no new pertinent information was being obtained.

Participants

National trainers..

Twenty-one national trainers in TF-CBT were interviewed. National trainers are mental health providers who completed a 15-month TF-CBT Train-the-Trainer program led by the TF-CBT developers. Trainers work extensively with numerous community mental health providers to problem-solve common barriers to clinical practice and thus, provide a unique perspective on the barriers to successful homework implementation and possible m Health solutions to those barriers. An e-mail invitation was sent to a list of approved TF-CBT trainers. Twenty-four trainers responded to this e-mail, 22 of whom agreed to participate in an interview, one of whom was unreachable after initial scheduling. Interviews were completed with a total of 21 trainers, who received a $25 gift card in compensation for their time.

Trainers had been treating children for an average of 23.29 years ( SD =8.80) and had been training providers for an average of 14.95 years ( SD =8.98). In the year prior to the interview, they led an average of 17 provider trainings ( SD =21.67) and trained roughly 345 providers ( SD =339.90). All trainers were licensed, and the majority were Clinical Psychologists (47.6%) and Social Workers (33.3%). The average age of trainers was 47.48 years ( SD =13.63) and the majority were female (71.4%), white (95.2%), and non-Hispanic/Latino (85.7%; see Table 1 ).

Trainer Demographics

Twelve families were interviewed for this study. Families were included if they had one or more youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years-of-age and a caregiver who had engaged in at least four sessions for TF-CBT. These criteria were chosen because TF-CBT is typically recommended for youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years-of-age and it was estimated that four sessions would have likely allowed for adequate time for patients to have received homework assignments, consistent with the authors’ experience and prior TF-CBT literature ( Deblinger, Pollio, & Dorsey, 2016 ; Scheeringa, Weems, Cohen, Amaya-Jackson, & Guthrie, 2011 ). Families were recruited via advertisements online and at local community mental health clinics, and from a participant pool from a prior study ( Davidson et al., 2019 ). Twenty-nine families initially expressed interest in participating in the study. Six families were ineligible because they had not received TF-CBT and contact was lost with six families after their initial contact. Seventeen families were scheduled for an interview, five of which were unreachable after initially being scheduled, and interviews were completed with 12 families. Written informed consent from caregivers and assent from youth above the age of 15 were obtained in-person for four families and via a telemedicine-based teleconsent platform (i.e., https://musc.doxy.me ) for eight families. Families received a $30 gift card in compensation for their time.

A total of 15 youth who had engaged in TF-CBT, and their caregivers ( n =12; three families had two youth who had received treatment) were interviewed. Six youth were still in treatment at the time of their interview and nine had finished treatment an average of 49 weeks ( SD =42.32) prior to the interview. The average age of youth was 13.20 years ( SD =3.19), roughly half were female (53.3%), the majority were white (80%), and all were non-Hispanic/Latino. The average age of caregivers was 44.83 years ( SD =7.90), 66.7% were female, and all were White and non-Hispanic/Latino. Youth and caregivers rated their comfort with technology, in general, on a 10-point Likert scale (i.e., 1–10) with higher scores representing higher levels of comfort. Youth reported being very comfortable with technology (M=9.62, SD =1.12), as did their caregivers (M=7.83, SD =2.63; see Table 2 ).

Family Demographics

= 6 families were still in treatment at the time of their interview and were not included in this average.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

TF-CBT is a well-established and widely disseminated mental health treatment ( Cohen et al., 2017 ; Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer, 2011 ; Silverman et al., 2008 ; Wethington et al., 2008 ). It is a conjoint youth-caregiver mental health treatment typically conducted over ~12, 90-minute sessions that address nine major treatment components (i.e., P sychoeducation; P arenting Skills; R elaxation Skills; A ffective Expression and Modulation Skills; C ognitive Coping and Processing Skills; T rauma Narration and Processing; I n Vivo Exposure; C onjoint Child Parent Activities; and E nhancing Future Safety and Development). TF-CBT also addresses a broad range of symptom domains including trauma- and stress-related disorders, disruptive behavior disorders/behaviors, depression/depressive symptoms, and anxiety disorders ( Cohen et al., 2017 ). TF-CBT was chosen as a model treatment for this study because of its broad symptom focus, inclusion of treatment components used in a variety of youth mental health treatments, and involvement of youth and their caregivers, offering potential to improve the applicability of the study’s results to a range of youth mental health treatment approaches.

Procedures for Data Collection

Interviews were conducted via telephone for trainers, and either in-person or via telephone for families based on their preference. A postdoctoral fellow and masters-level research assistant conducted the interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed using a professional transcription service. Interviews included three major components. The first component included demographic questions. The second included a brief orientation to the goal of the study, which was to develop a new technology-based resource to help providers and patients during the implementation of homework during mental health treatment. The third component included questions that aimed to assess perspectives on barriers to homework implementation, elicit suggestions for m Health solutions to those barriers, and examine perceptions on the benefits and challenges associated with m Health solutions to homework barriers. The average duration of interviews was 41 minutes for trainers and 37 minutes for families. See Supplementary Materials for complete interviews.

Data Analysis

Transcribed interviews were coded using NVivo qualitative analysis software. NVivo was used to identify common themes (nodes) as they related to (1) patient-, provider-, task-, and environmental-barriers to homework implementation, (2) suggestions for m Health solutions to homework barriers, and (3) benefits and challenges associated with m Health homework solutions. Initial and secondary coding passes were conducted to identify and refine theme classifications as they emerged and impose a data-derived hierarchy to the nodes identified. Focused coding was used to refine the coding and ensure that data were coded completely with minimal redundancy ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). Themes were initially proposed by the first author and reviewed by an expert in qualitative and mixed methods research (the second author) and an internationally recognized expert in the implementation of homework and related barriers during CBT (the fourth author). Divergent perspectives on theme descriptions ( n =2) and classifications ( n =1) were compared until agreement was reached.

Results are organized by the main topics explored in this study, including: 1) barriers to the successful implementation of homework, coded on provider, patient, task, and environmental levels; 2) potential m Health solutions to those homework barriers; and 3) perceived benefits and challenges of those potential m Health solutions. Results within each of these topics are presented first from the perspectives of trainers and second from the perspectives of families.

Barriers to the Successful Implementation of Homework

Trainer perspectives..

As displayed in Table 3 , trainers identified several barriers to homework implementation on the provider-, patient-, task-, and environmental-level.

Trainer Perspectives on Homework Barriers

Provider-Level Barriers.

Many trainers felt that providers tend to have difficulty engaging patients in assigned tasks, leading some providers to become discouraged by low levels of engagement. As stated by one trainer,

“I think they recognize that [homework assignments] do have value, but in terms of what I feel, a lot of clinicians are not having success with families completing homework, so it’s diminishing the sense of value…something they’ve tried to put into place and they are not feeling there’s any success in it.”

Trainers also noted that many providers do not see homework as an integral part of therapy. One trainer commented,

“I think there are a lot of concrete barriers, but to me probably the biggest barrier will be the–I think that still to this day [providers] like to think that therapy happens in that one hour.”

Other interrelated difficulties faced by providers related to their capacity to effectively and consistently develop, assess, and assign meaningful and patient-centered homework exercises.

As stated by one trainer,

“I see a lot of that just shooting from the hip, kind of off the cuff, ‘let’s do this,’ but yet, it’s not backed by anything concrete or tangible…I think probably one of the biggest pieces again is the failure on the clinician’s part to follow that up and too often review it at the end of the session.”

Another said,

“I think clinicians don’t always appreciate how hard it is to actually do homework that requires you to make some behavioral change.”

Barriers also related to providers’ time and resources for implementing homework, as conveyed by one trainer’s comment,

“I mean, these people…every minute of every day is filled up with doing, billing, writing, charting, going to meetings, getting supervision, and seeing patients, and then they go home exhausted.”

Patient-Level Barriers.

Many trainers stated that, similar to some providers, patients often do not see homework as an important part of therapy. Put by one trainer,

“I think that some [patients] just feel that coming to the session is enough and that should resolve everything, and that you know, doing homework is just kind of an extra thing…I don’t really need to do it to benefit from the therapy.”

Perhaps relatedly, trainers also noted that patients generally forget to do homework assignments, and often forget why, how, when, and where assignments should be done.

Task-Level Barriers.

Task-level barriers noted by trainers included assignments not always aligning with patient values or treatment goals and that the term ‘homework’ being aversive to patients of all ages. One trainer commented,

“I think it has to be something that [patients] see the value in. And again, we go back to that engagement and them trusting you as well as you explaining to them why this could be helpful…If it didn’t help, we need to change it.”

Another trainer laughed while stating,

“when we use the word homework, we might as well just throw a stink bomb in the room.”

Environmental-Level Barriers.

Finally, on the environmental-level, many trainers suggested that patients’ home lives are busy and chaotic, leaving little-to-no time for homework.

Explained by one trainer,

“I think that for parents…they have many other things in their life; work, parenting, partnerships that they are working on, just day to day chores or things that they have to do in terms of their family or other responsibilities. So, [homework] often feels like, I think for families, to add another thing…it just feels like a lot.”

Associated barriers included limited caregiver involvement and reinforcement for completing homework assignments. One trainer commented,

“So, let’s not forget that the parents need to be encouraged and checked on to make sure the kid is doing it. They have to work at it – It’s not going to just happen. So, helping the parents to see that they’re going to need to work to make sure the kids do it, because again, the kids would rather eat ice-cream than do the work. I mean change is hard.”

Another stated,

“I would say, lack of reinforcement for homework, so maybe for getting what you assign for homework and not reviewing it or the kiddo or the family learning pretty quickly, you know, why do it, because there’s not a lot of support around it. You know, if [patients] don’t get reinforced, whether tangibly or verbally, they may not continue that.”

Family Perspectives.

Families identified several barriers to homework implementation on the patient-, task-, and environmental-level which were similar to many of those noted by national trainers (see Table 4 ).

Family Perspectives on Homework Barriers

Families believed that patients often avoid homework as a result of their symptoms. In other words, the patient’s unhelpful coping strategies are being triggered.

One caregiver commented,

“Sometimes people don’t even want to dig into their feelings even to do the assignment either, you know. It stirs up things. You know, when you’re dealing with feelings, sometimes you don’t want to experience that feeling…you shut down. You don’t want to feel that at that time.”

“When you already have a child that has ADHD or behavior problems, it’s hard to get them motivated and to get them to do these exercises at home.”

Families also felt that patients simply forget to complete homework or bring it to their next session. One child stated,