Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 20 January 2023.

Exploratory research is a methodology approach that investigates topics and research questions that have not previously been studied in depth.

Exploratory research is often qualitative in nature. However, a study with a large sample conducted in an exploratory manner can be quantitative as well. It is also often referred to as interpretive research or a grounded theory approach due to its flexible and open-ended nature.

Table of contents

When to use exploratory research, exploratory research questions, exploratory research data collection, step-by-step example of exploratory research, exploratory vs explanatory research, advantages and disadvantages of exploratory research, frequently asked questions about exploratory research.

Exploratory research is often used when the issue you’re studying is new or when the data collection process is challenging for some reason.

You can use this type of research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Exploratory research questions are designed to help you understand more about a particular topic of interest. They can help you connect ideas to understand the groundwork of your analysis without adding any preconceived notions or assumptions yet.

Here are some examples:

- What effect does using a digital notebook have on the attention span of primary schoolers?

- What factors influence mental health in undergraduates?

- What outcomes are associated with an authoritative parenting style?

- In what ways does the presence of a non-native accent affect intelligibility?

- How can the use of a grocery delivery service reduce food waste in single-person households?

Collecting information on a previously unexplored topic can be challenging. Exploratory research can help you narrow down your topic and formulate a clear hypothesis , as well as giving you the ‘lay of the land’ on your topic.

Data collection using exploratory research is often divided into primary and secondary research methods, with data analysis following the same model.

Primary research

In primary research, your data is collected directly from primary sources : your participants. There is a variety of ways to collect primary data.

Some examples include:

- Survey methodology: Sending a survey out to the student body asking them if they would eat vegan meals

- Focus groups: Compiling groups of 8–10 students and discussing what they think of vegan options for dining hall food

- Interviews: Interviewing students entering and exiting the dining hall, asking if they would eat vegan meals

Secondary research

In secondary research, your data is collected from preexisting primary research, such as experiments or surveys.

Some other examples include:

- Case studies : Health of an all-vegan diet

- Literature reviews : Preexisting research about students’ eating habits and how they have changed over time

- Online polls, surveys, blog posts, or interviews; social media: Have other universities done something similar?

For some subjects, it’s possible to use large- n government data, such as the decennial census or yearly American Community Survey (ACS) open-source data.

How you proceed with your exploratory research design depends on the research method you choose to collect your data. In most cases, you will follow five steps.

We’ll walk you through the steps using the following example.

Therefore, you would like to focus on improving intelligibility instead of reducing the learner’s accent.

Step 1: Identify your problem

The first step in conducting exploratory research is identifying what the problem is and whether this type of research is the right avenue for you to pursue. Remember that exploratory research is most advantageous when you are investigating a previously unexplored problem.

Step 2: Hypothesise a solution

The next step is to come up with a solution to the problem you’re investigating. Formulate a hypothetical statement to guide your research.

Step 3. Design your methodology

Next, conceptualise your data collection and data analysis methods and write them up in a research design.

Step 4: Collect and analyse data

Next, you proceed with collecting and analysing your data so you can determine whether your preliminary results are in line with your hypothesis.

In most types of research, you should formulate your hypotheses a priori and refrain from changing them due to the increased risk of Type I errors and data integrity issues. However, in exploratory research, you are allowed to change your hypothesis based on your findings, since you are exploring a previously unexplained phenomenon that could have many explanations.

Step 5: Avenues for future research

Decide if you would like to continue studying your topic. If so, it is likely that you will need to change to another type of research. As exploratory research is often qualitative in nature, you may need to conduct quantitative research with a larger sample size to achieve more generalisable results.

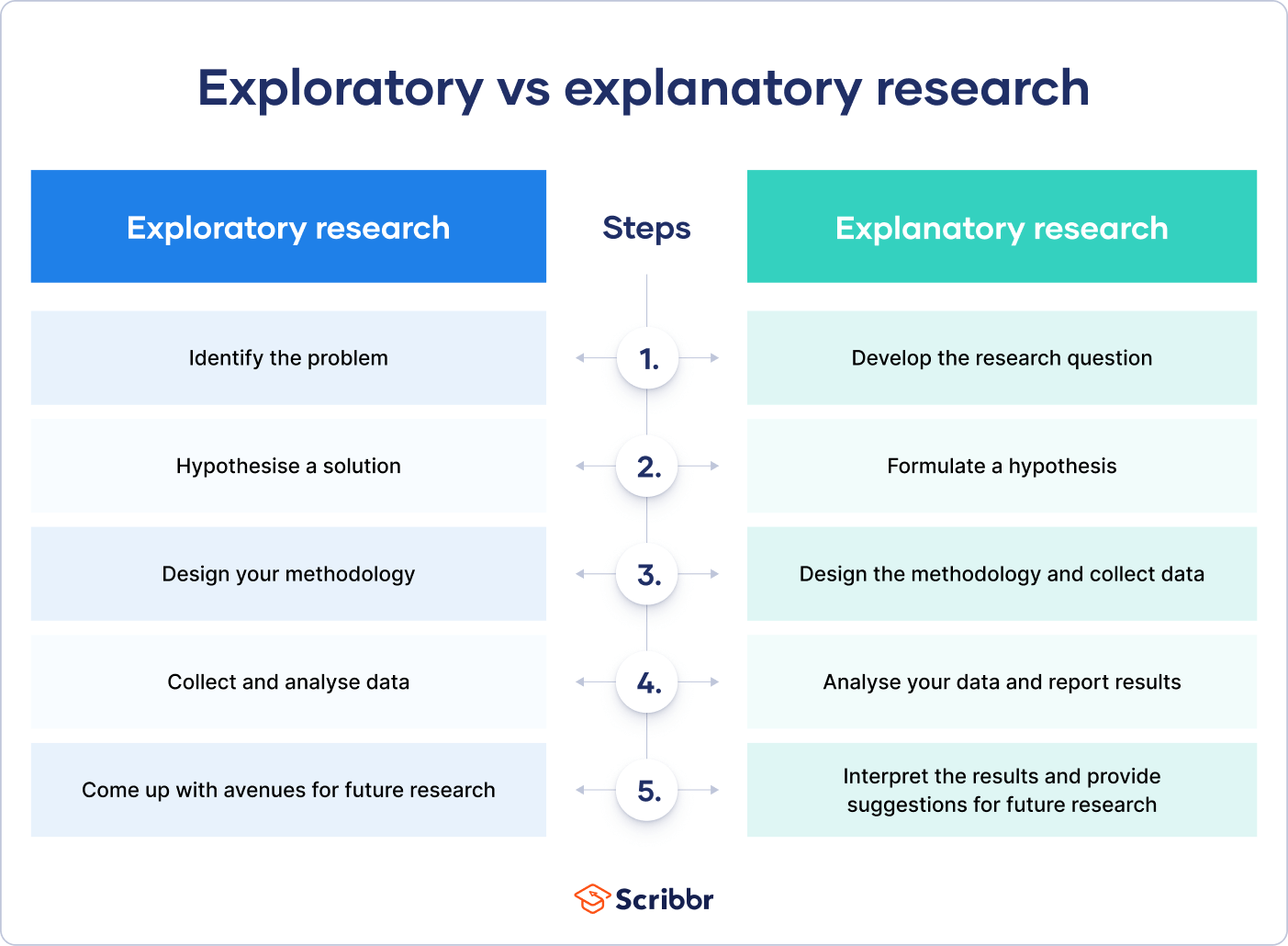

It can be easy to confuse exploratory research with explanatory research. To understand the relationship, it can help to remember that exploratory research lays the groundwork for later explanatory research.

Exploratory research investigates research questions that have not been studied in depth. The preliminary results often lay the groundwork for future analysis.

Explanatory research questions tend to start with ‘why’ or ‘how’, and the goal is to explain why or how a previously studied phenomenon takes place.

Like any other research design , exploratory research has its trade-offs: it provides a unique set of benefits but also comes with downsides.

- It can be very helpful in narrowing down a challenging or nebulous problem that has not been previously studied.

- It can serve as a great guide for future research, whether your own or another researcher’s. With new and challenging research problems, adding to the body of research in the early stages can be very fulfilling.

- It is very flexible, cost-effective, and open-ended. You are free to proceed however you think is best.

Disadvantages

- It usually lacks conclusive results, and results can be biased or subjective due to a lack of preexisting knowledge on your topic.

- It’s typically not externally valid and generalisable, and it suffers from many of the challenges of qualitative research .

- Since you are not operating within an existing research paradigm, this type of research can be very labour-intensive.

Exploratory research is a methodology approach that explores research questions that have not previously been studied in depth. It is often used when the issue you’re studying is new, or the data collection process is challenging in some way.

You can use exploratory research if you have a general idea or a specific question that you want to study but there is no preexisting knowledge or paradigm with which to study it.

Exploratory research explores the main aspects of a new or barely researched question.

Explanatory research explains the causes and effects of an already widely researched question.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2023, January 20). Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 26 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/exploratory-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples, case study | definition, examples & methods.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.9(8); 2019

Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research

Katharine a rendle.

1 Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Corey M Abramson

2 School of Sociology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA

Sarah B Garrett

3 Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA

Meghan C Halley

4 Palo Alto Medical Foundation for Health Care Research and Education, Palo Alto, California, USA

Daniel Dohan

Associated data.

The objective of this commentary is to develop a framework for assessing the rigour of qualitative approaches that identifies and distinguishes between the diverse objectives of qualitative health research, guided by a narrative review of the published literature on qualitative guidelines and standards from peer-reviewed journals and national funding organisations that support health services research, patient-centered outcomes research and other applied health research fields. In this framework, we identify and distinguish three objectives of qualitative studies in applied health research: exploratory, descriptive and comparative. For each objective, we propose methodological standards that may be used to assess and improve rigour across all study phases—from design to reporting. Similar to hierarchies of quality of evidence within quantitative studies, we argue that standards for qualitative rigour differ, appropriately, for studies with different objectives and should be evaluated as such. Distinguishing between different objectives of qualitative health research improves the ability to appreciate variation in qualitative studies and to develop appropriate evaluations of the rigour and success of qualitative studies in meeting their stated objectives. Researchers, funders and journal editors should consider how further developing and adopting the framework for assessing qualitative rigour outlined here may advance the rigour and potential impact of this important mode of inquiry.

Article summary

- Qualitative research in health services research (HSR) and allied fields has maintained steady, yet unsettled, interest and value over recent decades.

- Qualitative methods are epistemologically and theoretically diverse, which is a strength. However, it also means that investigators do not necessarily approach qualitative research using a unified set of evidentiary rules. As such, assessing rigour and quality across studies can be challenging.

- To help address these challenges, we propose a framework for assessing the rigour of qualitative approaches that identifies and distinguishes between three diverse study objectives. For each type of study, we propose preliminary methodological considerations to help improve rigour across all study phases. As is the case for quantitative studies, we argue that standards for qualitative rigourdiffer, appropriately, for different kinds of studies.

- The objective of this commentary is not to resolve all potential conflicts between philosophical assumptions of different qualitative approaches, but rather help to advance a broader and richer understanding of qualitative rigour in relationship to other evidence hierarchies.

In recent decades, the role of qualitative research in health services research (HSR) and allied fields has maintained steady, yet unsettled, interest and value. Evidence of steady interest includes publication of qualitative reviews and guidelines by leading journals including Health Services Research , 1 2 Medical Care Research and Review 3–5 and BMJ , 6 7 and by funders including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 8 National Institutes of Health 9 10 and National Science Foundation. 11 12 In fields such as Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) and implementation science, qualitative research has been embraced with particular enthusiasm for its ability to capture, advance and address questions meaningful to patients, clinicians and other healthcare system stakeholders. 2 13 The majority (82%) of inaugural projects awarded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) incorporated qualitative research methods. 13 More recently, reflective of the continued prevalence of these approaches in the field, PCORI incorporated qualitative methods into their methodological standards.

Yet, despite this sustained interest, the status of qualitative health research remains unsettled, as illustrated by the BMJ’s changing engagement with the method. After championing qualitative methods in 2008, 7 14–17 BMJ editors in 2016 noted that they tended to assign low priority to qualitative studies because such studies are ‘usually exploratory by their very nature’. 18 This statement came in response to an open letter from scholars arguing that BMJ should adopt formal policies and training for editorial staff on what distinguishes ‘good from poor qualitative research’ rather than de-emphasising the method in toto . 19 In sum, despite sustained interest from the HSR community, the status of qualitative research remains contested. This status reflects debate over the purpose of qualitative research—is it a valuable tool to advance the field or a low-priority exercise in exploration? —and an ongoing desire for guidance on how best to distinguish high-quality from low-quality qualitative research.

Assessing rigour and quality in qualitative research is challenging because qualitative methods are epistemologically diverse. 20–22 This diversity is a strength because it allows for the theoretical and methodological flexibility necessary to fully understand a specific topic from multiple perspectives. 16 However, it also means that investigators do not necessarily approach qualitative research using a unified set of evidentiary rules. 22 Thus, scholars may measure the quality of studies using different or even incompatible yardsticks.

The challenge of diverse epistemologies has become more acute as qualitative health research has expanded beyond its historical roots in phenomenological or grounded theory studies. Contemporary researchers may use qualitative data and methods to improve the descriptive accuracy of health-related phenomena that have already been characterised by exploratory work or are difficult to capture using other approaches. 23 Researchers also use larger scale, comparative qualitative studies in ways that resemble quantitative efforts to identify explanatory pathways. 24 Therefore, assessing the rigour of a specific qualitative study benefits from first identifying the analytic goals and objectives of the study—that is, identifying which yardstick investigators themselves have adopted—and then using this yardstick to examine how the study measures up.

To address these challenges, we propose a tailored framework for designing and informing assessments of different types of qualitative health research common within HSR. The framework recognises that qualitative investigators have different objectives and yardsticks in mind when undertaking studies and that rigour should be assessed accordingly. We distinguish three central types of qualitative study objectives common in applied health research: exploratory, descriptive and comparative. For each objective, we propose preliminary methodological considerations to help improve rigour across all study phases—from design to reporting. As is the case for quantitative studies, we argue that standards for qualitative rigour differ, appropriately, for different kinds of studies. The objective of this commentary is not to resolve all potential conflicts between philosophical assumptions of different qualitative approaches, but rather help to advance a broader and richer understanding of qualitative rigour in relationship to other evidence hierarchies. The proposed framework offers a nuanced set of categories by which to conduct and recognise high-quality qualitative research. The framework also supports efforts to shift debates over the value of qualitative research to discussions on how we can promote rigour across different types of valuable qualitative studies, and underscore how qualitative methods can advance clinical and applied health research.

Designing a tailored framework: methods and results

Our framework is based on a team-based review of published guidelines and standards discussing the scientific conduct of qualitative health research. Guided by expert consensus and a targeted literature scan, we identified and reviewed 17 peer-reviewed articles and expert reports published by journals widely read by the HSR community and by major funders or sponsors of qualitative health research (1–12, 21, 33–36). In contrast to previous reviews, 25 we did not seek to synthesise these guidelines. Rather we drew on them to develop a conceptual framework for designing and informing formal assessments of rigorous qualitative research.

Range of approaches in qualitative research

Qualitative research incorporates a range of methods including in-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnography and many others. 26 Even within a single method, accepted approaches and standards for rigour vary depending on disciplinary and theoretical orientations. Correspondingly, qualitative research cannot be defined by a single theoretical approach or data collection procedure. Rather many, often debated, approaches exist with distinct implications for appropriate standards for data collection, analysis and interpretation.

On one end of the spectrum, qualitative researchers guided by realism subscribe to the assumption that rigorous scientific research can provide an accurate and objective representation of reality, and that objectivity should be a primary goal of all scientific inquiries, including qualitative research. 27 These qualitative researchers generally consider standards such as validity, reliability, reproducibility and generalisability as similarly legitimate yardsticks for qualitative research as they are in quantitative research. 28 On the other end of the spectrum, relativist philosophical approaches to qualitative research typically argue that all research is inherently subjective and/or political, 29 and some relativists criticise the scientific approach specifically because it claims to be objective. 30 31 Much of applied qualitative health research falls somewhere between the two ends of the spectrum. For example, Mays and Pope consider themselves ‘subtle realists’. 6 They acknowledge that all research involves subjectivity and includes political dimensions, but they also contend that qualitative research should, nevertheless, be assessed by a similar set of quality criteria as quantitative studies. Although we recognise the value strictly relativist approaches provide, the framework and design considerations we propose are largely guided by a realist (or subtle realist) orientation. However, in addition to resonating with those who operate under similar orientations, we hope this framework will serve to advance discussions of how best to communicate and assess qualitative research using different theoretical and epistemological standpoints.

Tailored framework for qualitative health research

Given the diversity of approaches, a foundational step to improving the assessment of rigour in qualitative research is to abandon the attempt to develop a single standard for the best practices regardless of study orientation and objective. Instead, standards must begin with an assessment of epistemological assumptions and corresponding study objectives, an approach that is similar to standards for quantitative PCOR research 32 and mixed-methods research. 33 In this vein, we identified and defined three general types of study objectives broadly used in applied qualitative health research (see figure 1 ). These three types reflect differences in primary study objectives and existing knowledge within a topic area.

Three broad types of qualitative health research.

In table 1 , we provide preliminary distinctions on how exploratory, descriptive and comparative studies compare across a range of standards and guidelines that have been proposed for qualitative research (see table 1 ). Regardless of study type, researchers should report study details in clear, comprehensive ways, using standardised reporting guidelines whenever possible. 34 35

Framework for designing different types of applied qualitative health research and developing evaluative instruments to assess their rigour

| Exploratory studies | Descriptive studies | Comparative studies | |

| Epistemological framework | All studies should identify the epistemological framework under which the study and/or the investigators are guided. | ||

| State of evidence | Little to no data exist on the specific topic. | Exploratory data on the topic exist. | Exploratory and descriptive data on the topic exist. |

| Research aims | Define aims in broad, exploratory questions guided by the theoretical framework. A priori hypotheses are unnecessary and inappropriate. | Define aims based on existing knowledge and/or theoretical framework. hypotheses may be useful, but not needed. | Define aims based on existing knowledge and/or theoretical framework. hypotheses are recommended. |

| Sampling strategy | Appropriate to use a single, homogeneous sample. Convenience, purposeful or theoretical sampling is appropriate. | It may be appropriate to use a single, homogeneous sample if little is known about a specific subgroup or site. Purposeful or theoretical sampling is appropriate. | Include a diverse sample that supports comparison between groups. May consider integrating probability-based sampling stratified by groups of interest. Convenience sampling is inappropriate. |

| Data collection | Document interview or focus group data using audio recording and transcribe data verbatim, whenever possible. Any qualitative or ethnographical data that cannot be audio recorded should be collected using a systematic field note process. | ||

| Instrument | Develop an unstructured or semistructured guide based on aims. Adapt as new themes emerge. | Develop semistructured guide based on the aims and existing knowledge. Avoid changing key domains of interest; however, adding new themes is likely appropriate. | |

| Data analysis | Develop clear analytic steps, guided by a theoretical or conceptual framework. | ||

| Coding | Inductive, iterative coding is appropriate. Consider developing a coding dictionary and using independent coders to code data. | A mix of deductive coding based on aims, and inductive, iterative coding to explore new themes is appropriate. Develop and systematically apply a coding dictionary. Use independent coders to code data, if possible. | A primarily deductive coding approach based on aims is appropriate. Develop and systematically apply a coding dictionary. Use independent coders to code data and assess intercoder reliability. Consider using data triangulation and negative case review to improve reliability. |

| Researcher reflexivity | Consider and declare potential biases of researchers. | Consider and declare potential biases of researchers. Consider ways to mitigate biases in study design. | Consider and declare potential biases of researchers. Identify ways to address and/or avoid strong biases. |

| Reporting results | Include clear details on study aims, sampling data collection and analysis. Consider using standardised reporting guidelines, such as the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) or Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR). | ||

| Level of evidence produced | Evidence of phenomena within a specific sample. Findings do not establish wider significance or prevalence of phenomena. | Evidence of previously known phenomena in different setting or group. Findings support the wider significance of phenomena. | Evidence of the wider significance and possible prevalence of defined phenomena within the bounds of the study populations or settings. |

Compared with descriptive or comparative studies, exploratory studies approach the topic of study primarily in an inductive fashion to investigate the areas of potential research interest that remain mostly or wholly unexamined by the scientific community. Investigators undertaking exploratory studies typically have few expectations for what they might find, and their research design and approach may shift dramatically as they learn more about the phenomena of interest. An example of an exploratory study is a study that uses convenience sampling and unstructured interviews to explore what patients think about a new treatment in a single healthcare setting.

At the opposite end of this spectrum, investigators conducting comparative studies aim to use a primarily deductive approach designed to compare and document how well-defined qualitative phenomena are represented in different settings or populations. The qualitative methods employed in a comparative study are typically defined in advance, sampling should be systematic and structured by aims, and investigators enter the field with hypothesised ideas of what findings they may uncover and how to interpret those findings in light of previous research. An example of a comparative study is a multisite ethnography that seeks to compare how patient-provider communication varies by location, and uses random sampling of patient-provider interactions to collect data.

Descriptive studies occupy a middle position, building on previously conducted exploratory work so researchers will be able to proceed with more-focused inquiry. This should include well-defined procedures including sampling protocols and analytical plans, and investigators should usually articulate expected findings prior to beginning the study. However, as researchers investigate phenomena in new settings or patient populations, it is reasonable to expect descriptive studies to generate surprises. Thus, descriptive studies also feature inductive elements to detect unexpected findings, and must be flexible enough in design to accommodate shifts in research focus and methods based on empirical findings. An example of a descriptive study is a longitudinal study of patients with ovarian cancer that employs semistructured interviews and directed content analysis to examine decision-making across patients in a novel setting.

Our review identified a number of qualitative standards and guidelines that have been published. The conceptual framework we present here draws on those extant guidelines through the recognition that qualitative health research includes studies of diverse theoretical and epistemological orientations, each of which has distinct understandings of scientific quality and rigour. Given this intellectual diversity, it is inappropriate to use a single yardstick for all qualitative research. Rather, assessments of qualitative quality must begin with an assessment of a study’s theoretical orientations and research objectives to ensure that rigour is assessed on a study’s own terms. This framework and suggested approaches may help to advance evaluations of qualitative rigour that acknowledge and differentiate between the studies that report exploratory, descriptive or comparative study objectives.

Existing standards for conducting health research and grading evidence, such as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE), 36 do not capture the diversity of qualitative studies—often designating all qualitative studies as providing weak levels of evidence. PCORI’s own methodological standards have been largely silent regarding qualitative methods until recently, 32 leaving applicants without clear direction on how to conduct rigorous qualitative research. Incorporation of tailored qualitative standards could help to clarify and improve the rigour of proposal design, review and completion. The establishment and integration of such standards could also guide journal editors in developing transparent standards for deciding priorities for publication. For example, editors may decide against publication of exploratory or descriptive studies, but prioritise well-executed comparative studies that advance the field in ways quantitative studies could not.

In addition to these immediate applications, implementing standards that incorporate the diversity of objectives within applied qualitative research has the potential to address broader challenges facing qualitative health research. These include: (1) the need to educate broader audiences about the many goals of qualitative research, including but not limited to exploration; (2) the need to create rigorous standards for conducting and reporting various types of qualitative studies to help audiences, editors and funders evaluate studies on their own merits and (3) the challenges of publishing qualitative research in prestigious and high-impact journals that will reach a wide range of practitioners, researchers and lay audiences. We contend that these challenges can be reframed as opportunities to advance the science of qualitative research, and its potential for improving outcomes for patients, providers and communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Portions of this work were presented at the 2016 Academy Health Annual Research Meeting and 2017 Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting. The authors thank Katherine Gillespie and members of our Stakeholder Advisory Board for their invaluable contributions to the project.

Presented in: Earlier version presented at the 2016 Academy Health Annual Research Meeting in Boston, MA, USA.

Contributors: All authors (KAR, CMA, SBG, MCH and DD) helped to design and conceptualise this work including reviewing guidelines and conceptualising the proposed framework. KAR drafted the manuscript, and CMA, SBG, MCH and DD provided substantial review and writing to revisions.

Funding: This work was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (ME-1409-22996).

Disclaimer: The views presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Funders had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Types of Research Designs

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Introduction

Before beginning your paper, you need to decide how you plan to design the study .

The research design refers to the overall strategy and analytical approach that you have chosen in order to integrate, in a coherent and logical way, the different components of the study, thus ensuring that the research problem will be thoroughly investigated. It constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and interpretation of information and data. Note that the research problem determines the type of design you choose, not the other way around!

De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

General Structure and Writing Style

The function of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables you to effectively address the research problem logically and as unambiguously as possible . In social sciences research, obtaining information relevant to the research problem generally entails specifying the type of evidence needed to test the underlying assumptions of a theory, to evaluate a program, or to accurately describe and assess meaning related to an observable phenomenon.

With this in mind, a common mistake made by researchers is that they begin their investigations before they have thought critically about what information is required to address the research problem. Without attending to these design issues beforehand, the overall research problem will not be adequately addressed and any conclusions drawn will run the risk of being weak and unconvincing. As a consequence, the overall validity of the study will be undermined.

The length and complexity of describing the research design in your paper can vary considerably, but any well-developed description will achieve the following :

- Identify the research problem clearly and justify its selection, particularly in relation to any valid alternative designs that could have been used,

- Review and synthesize previously published literature associated with the research problem,

- Clearly and explicitly specify hypotheses [i.e., research questions] central to the problem,

- Effectively describe the information and/or data which will be necessary for an adequate testing of the hypotheses and explain how such information and/or data will be obtained, and

- Describe the methods of analysis to be applied to the data in determining whether or not the hypotheses are true or false.

The research design is usually incorporated into the introduction of your paper . You can obtain an overall sense of what to do by reviewing studies that have utilized the same research design [e.g., using a case study approach]. This can help you develop an outline to follow for your own paper.

NOTE: Use the SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases and the SAGE Research Methods Videos databases to search for scholarly resources on how to apply specific research designs and methods . The Research Methods Online database contains links to more than 175,000 pages of SAGE publisher's book, journal, and reference content on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research methodologies. Also included is a collection of case studies of social research projects that can be used to help you better understand abstract or complex methodological concepts. The Research Methods Videos database contains hours of tutorials, interviews, video case studies, and mini-documentaries covering the entire research process.

Creswell, John W. and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018; De Vaus, D. A. Research Design in Social Research . London: SAGE, 2001; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Leedy, Paul D. and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design . Tenth edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2013; Vogt, W. Paul, Dianna C. Gardner, and Lynne M. Haeffele. When to Use What Research Design . New York: Guilford, 2012.

Action Research Design

Definition and Purpose

The essentials of action research design follow a characteristic cycle whereby initially an exploratory stance is adopted, where an understanding of a problem is developed and plans are made for some form of interventionary strategy. Then the intervention is carried out [the "action" in action research] during which time, pertinent observations are collected in various forms. The new interventional strategies are carried out, and this cyclic process repeats, continuing until a sufficient understanding of [or a valid implementation solution for] the problem is achieved. The protocol is iterative or cyclical in nature and is intended to foster deeper understanding of a given situation, starting with conceptualizing and particularizing the problem and moving through several interventions and evaluations.

What do these studies tell you ?

- This is a collaborative and adaptive research design that lends itself to use in work or community situations.

- Design focuses on pragmatic and solution-driven research outcomes rather than testing theories.

- When practitioners use action research, it has the potential to increase the amount they learn consciously from their experience; the action research cycle can be regarded as a learning cycle.

- Action research studies often have direct and obvious relevance to improving practice and advocating for change.

- There are no hidden controls or preemption of direction by the researcher.

What these studies don't tell you ?

- It is harder to do than conducting conventional research because the researcher takes on responsibilities of advocating for change as well as for researching the topic.

- Action research is much harder to write up because it is less likely that you can use a standard format to report your findings effectively [i.e., data is often in the form of stories or observation].

- Personal over-involvement of the researcher may bias research results.

- The cyclic nature of action research to achieve its twin outcomes of action [e.g. change] and research [e.g. understanding] is time-consuming and complex to conduct.

- Advocating for change usually requires buy-in from study participants.

Coghlan, David and Mary Brydon-Miller. The Sage Encyclopedia of Action Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014; Efron, Sara Efrat and Ruth Ravid. Action Research in Education: A Practical Guide . New York: Guilford, 2013; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 18, Action Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Gorard, Stephen. Research Design: Creating Robust Approaches for the Social Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Kemmis, Stephen and Robin McTaggart. “Participatory Action Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000), pp. 567-605; McNiff, Jean. Writing and Doing Action Research . London: Sage, 2014; Reason, Peter and Hilary Bradbury. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001.

Case Study Design

A case study is an in-depth study of a particular research problem rather than a sweeping statistical survey or comprehensive comparative inquiry. It is often used to narrow down a very broad field of research into one or a few easily researchable examples. The case study research design is also useful for testing whether a specific theory and model actually applies to phenomena in the real world. It is a useful design when not much is known about an issue or phenomenon.

- Approach excels at bringing us to an understanding of a complex issue through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships.

- A researcher using a case study design can apply a variety of methodologies and rely on a variety of sources to investigate a research problem.

- Design can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research.

- Social scientists, in particular, make wide use of this research design to examine contemporary real-life situations and provide the basis for the application of concepts and theories and the extension of methodologies.

- The design can provide detailed descriptions of specific and rare cases.

- A single or small number of cases offers little basis for establishing reliability or to generalize the findings to a wider population of people, places, or things.

- Intense exposure to the study of a case may bias a researcher's interpretation of the findings.

- Design does not facilitate assessment of cause and effect relationships.

- Vital information may be missing, making the case hard to interpret.

- The case may not be representative or typical of the larger problem being investigated.

- If the criteria for selecting a case is because it represents a very unusual or unique phenomenon or problem for study, then your interpretation of the findings can only apply to that particular case.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 4, Flexible Methods: Case Study Design. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Greenhalgh, Trisha, editor. Case Study Evaluation: Past, Present and Future Challenges . Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2015; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1995; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Theory . Applied Social Research Methods Series, no. 5. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

Causal Design

Causality studies may be thought of as understanding a phenomenon in terms of conditional statements in the form, “If X, then Y.” This type of research is used to measure what impact a specific change will have on existing norms and assumptions. Most social scientists seek causal explanations that reflect tests of hypotheses. Causal effect (nomothetic perspective) occurs when variation in one phenomenon, an independent variable, leads to or results, on average, in variation in another phenomenon, the dependent variable.

Conditions necessary for determining causality:

- Empirical association -- a valid conclusion is based on finding an association between the independent variable and the dependent variable.

- Appropriate time order -- to conclude that causation was involved, one must see that cases were exposed to variation in the independent variable before variation in the dependent variable.

- Nonspuriousness -- a relationship between two variables that is not due to variation in a third variable.

- Causality research designs assist researchers in understanding why the world works the way it does through the process of proving a causal link between variables and by the process of eliminating other possibilities.

- Replication is possible.

- There is greater confidence the study has internal validity due to the systematic subject selection and equity of groups being compared.

- Not all relationships are causal! The possibility always exists that, by sheer coincidence, two unrelated events appear to be related [e.g., Punxatawney Phil could accurately predict the duration of Winter for five consecutive years but, the fact remains, he's just a big, furry rodent].

- Conclusions about causal relationships are difficult to determine due to a variety of extraneous and confounding variables that exist in a social environment. This means causality can only be inferred, never proven.

- If two variables are correlated, the cause must come before the effect. However, even though two variables might be causally related, it can sometimes be difficult to determine which variable comes first and, therefore, to establish which variable is the actual cause and which is the actual effect.

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Causal Case Study Methods: Foundations and Guidelines for Comparing, Matching, and Tracing . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016; Bachman, Ronet. The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice . Chapter 5, Causation and Research Designs. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 2007; Brewer, Ernest W. and Jennifer Kubn. “Causal-Comparative Design.” In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 125-132; Causal Research Design: Experimentation. Anonymous SlideShare Presentation; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 11, Nonexperimental Research: Correlational Designs. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007; Trochim, William M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006.

Cohort Design

Often used in the medical sciences, but also found in the applied social sciences, a cohort study generally refers to a study conducted over a period of time involving members of a population which the subject or representative member comes from, and who are united by some commonality or similarity. Using a quantitative framework, a cohort study makes note of statistical occurrence within a specialized subgroup, united by same or similar characteristics that are relevant to the research problem being investigated, rather than studying statistical occurrence within the general population. Using a qualitative framework, cohort studies generally gather data using methods of observation. Cohorts can be either "open" or "closed."

- Open Cohort Studies [dynamic populations, such as the population of Los Angeles] involve a population that is defined just by the state of being a part of the study in question (and being monitored for the outcome). Date of entry and exit from the study is individually defined, therefore, the size of the study population is not constant. In open cohort studies, researchers can only calculate rate based data, such as, incidence rates and variants thereof.

- Closed Cohort Studies [static populations, such as patients entered into a clinical trial] involve participants who enter into the study at one defining point in time and where it is presumed that no new participants can enter the cohort. Given this, the number of study participants remains constant (or can only decrease).

- The use of cohorts is often mandatory because a randomized control study may be unethical. For example, you cannot deliberately expose people to asbestos, you can only study its effects on those who have already been exposed. Research that measures risk factors often relies upon cohort designs.

- Because cohort studies measure potential causes before the outcome has occurred, they can demonstrate that these “causes” preceded the outcome, thereby avoiding the debate as to which is the cause and which is the effect.

- Cohort analysis is highly flexible and can provide insight into effects over time and related to a variety of different types of changes [e.g., social, cultural, political, economic, etc.].

- Either original data or secondary data can be used in this design.

- In cases where a comparative analysis of two cohorts is made [e.g., studying the effects of one group exposed to asbestos and one that has not], a researcher cannot control for all other factors that might differ between the two groups. These factors are known as confounding variables.

- Cohort studies can end up taking a long time to complete if the researcher must wait for the conditions of interest to develop within the group. This also increases the chance that key variables change during the course of the study, potentially impacting the validity of the findings.

- Due to the lack of randominization in the cohort design, its external validity is lower than that of study designs where the researcher randomly assigns participants.

Healy P, Devane D. “Methodological Considerations in Cohort Study Designs.” Nurse Researcher 18 (2011): 32-36; Glenn, Norval D, editor. Cohort Analysis . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Levin, Kate Ann. Study Design IV: Cohort Studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry 7 (2003): 51–52; Payne, Geoff. “Cohort Study.” In The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods . Victor Jupp, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), pp. 31-33; Study Design 101. Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. George Washington University, November 2011; Cohort Study. Wikipedia.

Cross-Sectional Design

Cross-sectional research designs have three distinctive features: no time dimension; a reliance on existing differences rather than change following intervention; and, groups are selected based on existing differences rather than random allocation. The cross-sectional design can only measure differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. As such, researchers using this design can only employ a relatively passive approach to making causal inferences based on findings.

- Cross-sectional studies provide a clear 'snapshot' of the outcome and the characteristics associated with it, at a specific point in time.

- Unlike an experimental design, where there is an active intervention by the researcher to produce and measure change or to create differences, cross-sectional designs focus on studying and drawing inferences from existing differences between people, subjects, or phenomena.

- Entails collecting data at and concerning one point in time. While longitudinal studies involve taking multiple measures over an extended period of time, cross-sectional research is focused on finding relationships between variables at one moment in time.

- Groups identified for study are purposely selected based upon existing differences in the sample rather than seeking random sampling.

- Cross-section studies are capable of using data from a large number of subjects and, unlike observational studies, is not geographically bound.

- Can estimate prevalence of an outcome of interest because the sample is usually taken from the whole population.

- Because cross-sectional designs generally use survey techniques to gather data, they are relatively inexpensive and take up little time to conduct.

- Finding people, subjects, or phenomena to study that are very similar except in one specific variable can be difficult.

- Results are static and time bound and, therefore, give no indication of a sequence of events or reveal historical or temporal contexts.

- Studies cannot be utilized to establish cause and effect relationships.

- This design only provides a snapshot of analysis so there is always the possibility that a study could have differing results if another time-frame had been chosen.

- There is no follow up to the findings.

Bethlehem, Jelke. "7: Cross-sectional Research." In Research Methodology in the Social, Behavioural and Life Sciences . Herman J Adèr and Gideon J Mellenbergh, editors. (London, England: Sage, 1999), pp. 110-43; Bourque, Linda B. “Cross-Sectional Design.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods . Michael S. Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. (Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004), pp. 230-231; Hall, John. “Cross-Sectional Survey Design.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 173-174; Helen Barratt, Maria Kirwan. Cross-Sectional Studies: Design Application, Strengths and Weaknesses of Cross-Sectional Studies. Healthknowledge, 2009. Cross-Sectional Study. Wikipedia.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research designs help provide answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and how associated with a particular research problem; a descriptive study cannot conclusively ascertain answers to why. Descriptive research is used to obtain information concerning the current status of the phenomena and to describe "what exists" with respect to variables or conditions in a situation.

- The subject is being observed in a completely natural and unchanged natural environment. True experiments, whilst giving analyzable data, often adversely influence the normal behavior of the subject [a.k.a., the Heisenberg effect whereby measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems].

- Descriptive research is often used as a pre-cursor to more quantitative research designs with the general overview giving some valuable pointers as to what variables are worth testing quantitatively.

- If the limitations are understood, they can be a useful tool in developing a more focused study.

- Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations in practice.

- Appoach collects a large amount of data for detailed analysis.

- The results from a descriptive research cannot be used to discover a definitive answer or to disprove a hypothesis.

- Because descriptive designs often utilize observational methods [as opposed to quantitative methods], the results cannot be replicated.

- The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 5, Flexible Methods: Descriptive Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Given, Lisa M. "Descriptive Research." In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics . Neil J. Salkind and Kristin Rasmussen, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 251-254; McNabb, Connie. Descriptive Research Methodologies. Powerpoint Presentation; Shuttleworth, Martyn. Descriptive Research Design, September 26, 2008; Erickson, G. Scott. "Descriptive Research Design." In New Methods of Market Research and Analysis . (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017), pp. 51-77; Sahin, Sagufta, and Jayanta Mete. "A Brief Study on Descriptive Research: Its Nature and Application in Social Science." International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities 1 (2021): 11; K. Swatzell and P. Jennings. “Descriptive Research: The Nuts and Bolts.” Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants 20 (2007), pp. 55-56; Kane, E. Doing Your Own Research: Basic Descriptive Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities . London: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Experimental Design

A blueprint of the procedure that enables the researcher to maintain control over all factors that may affect the result of an experiment. In doing this, the researcher attempts to determine or predict what may occur. Experimental research is often used where there is time priority in a causal relationship (cause precedes effect), there is consistency in a causal relationship (a cause will always lead to the same effect), and the magnitude of the correlation is great. The classic experimental design specifies an experimental group and a control group. The independent variable is administered to the experimental group and not to the control group, and both groups are measured on the same dependent variable. Subsequent experimental designs have used more groups and more measurements over longer periods. True experiments must have control, randomization, and manipulation.

- Experimental research allows the researcher to control the situation. In so doing, it allows researchers to answer the question, “What causes something to occur?”

- Permits the researcher to identify cause and effect relationships between variables and to distinguish placebo effects from treatment effects.

- Experimental research designs support the ability to limit alternative explanations and to infer direct causal relationships in the study.

- Approach provides the highest level of evidence for single studies.

- The design is artificial, and results may not generalize well to the real world.

- The artificial settings of experiments may alter the behaviors or responses of participants.

- Experimental designs can be costly if special equipment or facilities are needed.

- Some research problems cannot be studied using an experiment because of ethical or technical reasons.

- Difficult to apply ethnographic and other qualitative methods to experimentally designed studies.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 7, Flexible Methods: Experimental Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Chapter 2: Research Design, Experimental Designs. School of Psychology, University of New England, 2000; Chow, Siu L. "Experimental Design." In Encyclopedia of Research Design . Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 448-453; "Experimental Design." In Social Research Methods . Nicholas Walliman, editor. (London, England: Sage, 2006), pp, 101-110; Experimental Research. Research Methods by Dummies. Department of Psychology. California State University, Fresno, 2006; Kirk, Roger E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013; Trochim, William M.K. Experimental Design. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Rasool, Shafqat. Experimental Research. Slideshare presentation.

Exploratory Design

An exploratory design is conducted about a research problem when there are few or no earlier studies to refer to or rely upon to predict an outcome . The focus is on gaining insights and familiarity for later investigation or undertaken when research problems are in a preliminary stage of investigation. Exploratory designs are often used to establish an understanding of how best to proceed in studying an issue or what methodology would effectively apply to gathering information about the issue.

The goals of exploratory research are intended to produce the following possible insights:

- Familiarity with basic details, settings, and concerns.

- Well grounded picture of the situation being developed.

- Generation of new ideas and assumptions.

- Development of tentative theories or hypotheses.

- Determination about whether a study is feasible in the future.

- Issues get refined for more systematic investigation and formulation of new research questions.

- Direction for future research and techniques get developed.

- Design is a useful approach for gaining background information on a particular topic.

- Exploratory research is flexible and can address research questions of all types (what, why, how).

- Provides an opportunity to define new terms and clarify existing concepts.

- Exploratory research is often used to generate formal hypotheses and develop more precise research problems.

- In the policy arena or applied to practice, exploratory studies help establish research priorities and where resources should be allocated.

- Exploratory research generally utilizes small sample sizes and, thus, findings are typically not generalizable to the population at large.

- The exploratory nature of the research inhibits an ability to make definitive conclusions about the findings. They provide insight but not definitive conclusions.

- The research process underpinning exploratory studies is flexible but often unstructured, leading to only tentative results that have limited value to decision-makers.

- Design lacks rigorous standards applied to methods of data gathering and analysis because one of the areas for exploration could be to determine what method or methodologies could best fit the research problem.

Cuthill, Michael. “Exploratory Research: Citizen Participation, Local Government, and Sustainable Development in Australia.” Sustainable Development 10 (2002): 79-89; Streb, Christoph K. "Exploratory Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos and Eiden Wiebe, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010), pp. 372-374; Taylor, P. J., G. Catalano, and D.R.F. Walker. “Exploratory Analysis of the World City Network.” Urban Studies 39 (December 2002): 2377-2394; Exploratory Research. Wikipedia.

Field Research Design

Sometimes referred to as ethnography or participant observation, designs around field research encompass a variety of interpretative procedures [e.g., observation and interviews] rooted in qualitative approaches to studying people individually or in groups while inhabiting their natural environment as opposed to using survey instruments or other forms of impersonal methods of data gathering. Information acquired from observational research takes the form of “ field notes ” that involves documenting what the researcher actually sees and hears while in the field. Findings do not consist of conclusive statements derived from numbers and statistics because field research involves analysis of words and observations of behavior. Conclusions, therefore, are developed from an interpretation of findings that reveal overriding themes, concepts, and ideas. More information can be found HERE .

- Field research is often necessary to fill gaps in understanding the research problem applied to local conditions or to specific groups of people that cannot be ascertained from existing data.

- The research helps contextualize already known information about a research problem, thereby facilitating ways to assess the origins, scope, and scale of a problem and to gage the causes, consequences, and means to resolve an issue based on deliberate interaction with people in their natural inhabited spaces.

- Enables the researcher to corroborate or confirm data by gathering additional information that supports or refutes findings reported in prior studies of the topic.

- Because the researcher in embedded in the field, they are better able to make observations or ask questions that reflect the specific cultural context of the setting being investigated.

- Observing the local reality offers the opportunity to gain new perspectives or obtain unique data that challenges existing theoretical propositions or long-standing assumptions found in the literature.

What these studies don't tell you

- A field research study requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved with preparing for the gathering of information, including for example, examining background information about the study site, obtaining permission to access the study site, and building trust and rapport with subjects.

- Requires a commitment to staying engaged in the field to ensure that you can adequately document events and behaviors as they unfold.

- The unpredictable nature of fieldwork means that researchers can never fully control the process of data gathering. They must maintain a flexible approach to studying the setting because events and circumstances can change quickly or unexpectedly.

- Findings can be difficult to interpret and verify without access to documents and other source materials that help to enhance the credibility of information obtained from the field [i.e., the act of triangulating the data].

- Linking the research problem to the selection of study participants inhabiting their natural environment is critical. However, this specificity limits the ability to generalize findings to different situations or in other contexts or to infer courses of action applied to other settings or groups of people.

- The reporting of findings must take into account how the researcher themselves may have inadvertently affected respondents and their behaviors.

Historical Design

The purpose of a historical research design is to collect, verify, and synthesize evidence from the past to establish facts that defend or refute a hypothesis. It uses secondary sources and a variety of primary documentary evidence, such as, diaries, official records, reports, archives, and non-textual information [maps, pictures, audio and visual recordings]. The limitation is that the sources must be both authentic and valid.

- The historical research design is unobtrusive; the act of research does not affect the results of the study.

- The historical approach is well suited for trend analysis.

- Historical records can add important contextual background required to more fully understand and interpret a research problem.

- There is often no possibility of researcher-subject interaction that could affect the findings.

- Historical sources can be used over and over to study different research problems or to replicate a previous study.

- The ability to fulfill the aims of your research are directly related to the amount and quality of documentation available to understand the research problem.

- Since historical research relies on data from the past, there is no way to manipulate it to control for contemporary contexts.

- Interpreting historical sources can be very time consuming.

- The sources of historical materials must be archived consistently to ensure access. This may especially challenging for digital or online-only sources.

- Original authors bring their own perspectives and biases to the interpretation of past events and these biases are more difficult to ascertain in historical resources.

- Due to the lack of control over external variables, historical research is very weak with regard to the demands of internal validity.

- It is rare that the entirety of historical documentation needed to fully address a research problem is available for interpretation, therefore, gaps need to be acknowledged.

Howell, Martha C. and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001; Lundy, Karen Saucier. "Historical Research." In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods . Lisa M. Given, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 396-400; Marius, Richard. and Melvin E. Page. A Short Guide to Writing about History . 9th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2015; Savitt, Ronald. “Historical Research in Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 44 (Autumn, 1980): 52-58; Gall, Meredith. Educational Research: An Introduction . Chapter 16, Historical Research. 8th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2007.

Longitudinal Design

A longitudinal study follows the same sample over time and makes repeated observations. For example, with longitudinal surveys, the same group of people is interviewed at regular intervals, enabling researchers to track changes over time and to relate them to variables that might explain why the changes occur. Longitudinal research designs describe patterns of change and help establish the direction and magnitude of causal relationships. Measurements are taken on each variable over two or more distinct time periods. This allows the researcher to measure change in variables over time. It is a type of observational study sometimes referred to as a panel study.

- Longitudinal data facilitate the analysis of the duration of a particular phenomenon.

- Enables survey researchers to get close to the kinds of causal explanations usually attainable only with experiments.

- The design permits the measurement of differences or change in a variable from one period to another [i.e., the description of patterns of change over time].

- Longitudinal studies facilitate the prediction of future outcomes based upon earlier factors.

- The data collection method may change over time.

- Maintaining the integrity of the original sample can be difficult over an extended period of time.

- It can be difficult to show more than one variable at a time.

- This design often needs qualitative research data to explain fluctuations in the results.

- A longitudinal research design assumes present trends will continue unchanged.

- It can take a long period of time to gather results.

- There is a need to have a large sample size and accurate sampling to reach representativness.

Anastas, Jeane W. Research Design for Social Work and the Human Services . Chapter 6, Flexible Methods: Relational and Longitudinal Research. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; Forgues, Bernard, and Isabelle Vandangeon-Derumez. "Longitudinal Analyses." In Doing Management Research . Raymond-Alain Thiétart and Samantha Wauchope, editors. (London, England: Sage, 2001), pp. 332-351; Kalaian, Sema A. and Rafa M. Kasim. "Longitudinal Studies." In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods . Paul J. Lavrakas, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008), pp. 440-441; Menard, Scott, editor. Longitudinal Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002; Ployhart, Robert E. and Robert J. Vandenberg. "Longitudinal Research: The Theory, Design, and Analysis of Change.” Journal of Management 36 (January 2010): 94-120; Longitudinal Study. Wikipedia.

Meta-Analysis Design

Meta-analysis is an analytical methodology designed to systematically evaluate and summarize the results from a number of individual studies, thereby, increasing the overall sample size and the ability of the researcher to study effects of interest. The purpose is to not simply summarize existing knowledge, but to develop a new understanding of a research problem using synoptic reasoning. The main objectives of meta-analysis include analyzing differences in the results among studies and increasing the precision by which effects are estimated. A well-designed meta-analysis depends upon strict adherence to the criteria used for selecting studies and the availability of information in each study to properly analyze their findings. Lack of information can severely limit the type of analyzes and conclusions that can be reached. In addition, the more dissimilarity there is in the results among individual studies [heterogeneity], the more difficult it is to justify interpretations that govern a valid synopsis of results. A meta-analysis needs to fulfill the following requirements to ensure the validity of your findings:

- Clearly defined description of objectives, including precise definitions of the variables and outcomes that are being evaluated;

- A well-reasoned and well-documented justification for identification and selection of the studies;

- Assessment and explicit acknowledgment of any researcher bias in the identification and selection of those studies;

- Description and evaluation of the degree of heterogeneity among the sample size of studies reviewed; and,

- Justification of the techniques used to evaluate the studies.

- Can be an effective strategy for determining gaps in the literature.

- Provides a means of reviewing research published about a particular topic over an extended period of time and from a variety of sources.

- Is useful in clarifying what policy or programmatic actions can be justified on the basis of analyzing research results from multiple studies.

- Provides a method for overcoming small sample sizes in individual studies that previously may have had little relationship to each other.

- Can be used to generate new hypotheses or highlight research problems for future studies.

- Small violations in defining the criteria used for content analysis can lead to difficult to interpret and/or meaningless findings.

- A large sample size can yield reliable, but not necessarily valid, results.

- A lack of uniformity regarding, for example, the type of literature reviewed, how methods are applied, and how findings are measured within the sample of studies you are analyzing, can make the process of synthesis difficult to perform.

- Depending on the sample size, the process of reviewing and synthesizing multiple studies can be very time consuming.

Beck, Lewis W. "The Synoptic Method." The Journal of Philosophy 36 (1939): 337-345; Cooper, Harris, Larry V. Hedges, and Jeffrey C. Valentine, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis . 2nd edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009; Guzzo, Richard A., Susan E. Jackson and Raymond A. Katzell. “Meta-Analysis Analysis.” In Research in Organizational Behavior , Volume 9. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1987), pp 407-442; Lipsey, Mark W. and David B. Wilson. Practical Meta-Analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001; Study Design 101. Meta-Analysis. The Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, George Washington University; Timulak, Ladislav. “Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis . Uwe Flick, editor. (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2013), pp. 481-495; Walker, Esteban, Adrian V. Hernandez, and Micheal W. Kattan. "Meta-Analysis: It's Strengths and Limitations." Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 75 (June 2008): 431-439.

Mixed-Method Design

- Narrative and non-textual information can add meaning to numeric data, while numeric data can add precision to narrative and non-textual information.

- Can utilize existing data while at the same time generating and testing a grounded theory approach to describe and explain the phenomenon under study.

- A broader, more complex research problem can be investigated because the researcher is not constrained by using only one method.

- The strengths of one method can be used to overcome the inherent weaknesses of another method.

- Can provide stronger, more robust evidence to support a conclusion or set of recommendations.

- May generate new knowledge new insights or uncover hidden insights, patterns, or relationships that a single methodological approach might not reveal.

- Produces more complete knowledge and understanding of the research problem that can be used to increase the generalizability of findings applied to theory or practice.

- A researcher must be proficient in understanding how to apply multiple methods to investigating a research problem as well as be proficient in optimizing how to design a study that coherently melds them together.

- Can increase the likelihood of conflicting results or ambiguous findings that inhibit drawing a valid conclusion or setting forth a recommended course of action [e.g., sample interview responses do not support existing statistical data].

- Because the research design can be very complex, reporting the findings requires a well-organized narrative, clear writing style, and precise word choice.

- Design invites collaboration among experts. However, merging different investigative approaches and writing styles requires more attention to the overall research process than studies conducted using only one methodological paradigm.

- Concurrent merging of quantitative and qualitative research requires greater attention to having adequate sample sizes, using comparable samples, and applying a consistent unit of analysis. For sequential designs where one phase of qualitative research builds on the quantitative phase or vice versa, decisions about what results from the first phase to use in the next phase, the choice of samples and estimating reasonable sample sizes for both phases, and the interpretation of results from both phases can be difficult.

- Due to multiple forms of data being collected and analyzed, this design requires extensive time and resources to carry out the multiple steps involved in data gathering and interpretation.

Burch, Patricia and Carolyn J. Heinrich. Mixed Methods for Policy Research and Program Evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2016; Creswell, John w. et al. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences . Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, 2010Creswell, John W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2014; Domínguez, Silvia, editor. Mixed Methods Social Networks Research . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy. Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice . New York: Guilford Press, 2010; Niglas, Katrin. “How the Novice Researcher Can Make Sense of Mixed Methods Designs.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3 (2009): 34-46; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Nancy L. Leech. “Linking Research Questions to Mixed Methods Data Analysis Procedures.” The Qualitative Report 11 (September 2006): 474-498; Tashakorri, Abbas and John W. Creswell. “The New Era of Mixed Methods.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (January 2007): 3-7; Zhanga, Wanqing. “Mixed Methods Application in Health Intervention Research: A Multiple Case Study.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 8 (2014): 24-35 .

Observational Design

This type of research design draws a conclusion by comparing subjects against a control group, in cases where the researcher has no control over the experiment. There are two general types of observational designs. In direct observations, people know that you are watching them. Unobtrusive measures involve any method for studying behavior where individuals do not know they are being observed. An observational study allows a useful insight into a phenomenon and avoids the ethical and practical difficulties of setting up a large and cumbersome research project.