Defense Mechanisms In Psychology Explained (+ Examples)

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Sigmund Freud (1894, 1896) noted a number of ego defenses, which he refers to throughout his written works.

His daughter Anna Freud (1936) developed these ideas and elaborated on them, adding ten of her own. Many psychoanalysts have also added further types of ego defenses.

Defense mechanisms are psychological strategies that are unconsciously used to protect a person from anxiety arising from unacceptable thoughts or feelings. According to Freudian theory, defense mechanismss involve a distortion of relaity in wome way so that we are better able to cope with a situation.

10 Defense Mechanisms: What Are They and How They Help Us Cope

We use defense mechanisms to protect ourselves from feelings of anxiety or guilt, which arise because we feel threatened, or because our id or superego becomes too demanding.

Defense mechanisms operate at an unconscious level and help ward off unpleasant feelings (i.e., anxiety) or make good things feel better for the individual.

Ego-defense mechanisms are natural and normal. When they get out of proportion (i.e., used with frequency), neuroses develop, such as anxiety states, phobias, obsessions, or hysteria.

Here are a few common defense mechanisms: There are a large number of defense mechanisms; the main ones are summarized below.

Denial is a defense mechanism proposed by Anna Freud that involves a refusal to accept reality, thus blocking external events from awareness.

If a situation is just too much to handle, the person may respond by refusing to perceive it or denying that it exists.

As you might imagine, this is a primitive and dangerous defense – no one disregards reality and gets away with it for long!

It can operate by itself or, more commonly, in combination with other, more subtle mechanisms that support it.

What is an example of denial?

Many people use denial in their everyday lives to avoid dealing with painful feelings or areas of their life they don’t wish to admit.

For example, a husband may refuse to recognize obvious signs of his wife’s infidelity. A student may refuse to recognize their obvious lack of preparedness for an exam!

Repression is an unconscious defense mechanism employed by the ego to keep disturbing or threatening thoughts from becoming conscious.

Repression, which Anna Freud also called “motivated forgetting,” is just that: not being able to recall a threatening situation, person, or event.

Thoughts that are often repressed are those that would result in feelings of guilt from the superego.

This is not a very successful defense in the long term since it involves forcing disturbing wishes, ideas or memories into the unconscious, where, although hidden, they will create anxiety.

Repressed memories may appear through subconscious means and in altered forms, such as dreams or slips of the tongue ( Freudian slips ).

What is an example of repression?

For example, in the oedipus complex , aggressive thoughts about the same sex parents are repressed and pushed down into the unconscious.

Projection is a psychological defense mechanism proposed by Anna Freud in which an individual attributes unwanted thoughts, feelings, and motives to another person.

Projection is generally understood as a defense mechanism that protects self-esteem by externalizing undesirable aspects of the self.

Projection, which Anna Freud also called displacement outward, is almost the complete opposite of turning against the self. It involves the tendency to see your own unacceptable desires in other people.

In other words, the desires are still there, but they’re not your desires anymore.

What is an example of projection?

Thoughts most commonly projected onto another are the ones that would cause guilt such as aggressive and sexual fantasies or thoughts.

For instance, you might hate someone, but your superego tells you that such hatred is unacceptable. You can ‘solve’ the problem by believing that they hate you.

Displacement

Displacement is the redirection of an impulse (usually aggression) onto a powerless substitute target. The target can be a person or an object that can serve as a symbolic substitute.

Displacement occurs when the Id wants to do something which the Superego does not permit. The Ego thus finds some other way of releasing the psychic energy of the Id.

Thus there is a transfer of energy from a repressed object-cathexis to a more acceptable object.

Turning against the self is a very special form of displacement, where the person becomes their own substitute target.

It is normally used in reference to hatred, anger, and aggression, rather than more positive impulses, and it is the Freudian explanation for many of our feelings of inferiority, guilt, and depression.

The idea that depression is often the result of the anger we refuse to acknowledge is accepted by many people, Freudians and non-Freudians alike.

What is an example of displacement?

Someone who feels uncomfortable with their sexual desire for a real person may substitute a fetish.

Someone who is frustrated by his or her superiors may go home and kick the dog, beat up a family member, or engage in cross-burnings.

Regression is a defense mechanism proposed by Anna Freud whereby the the ego reverts to an earlier stage of development usually in response to stressful situations.

Regression functions as a form of retreat, enabling a person to psychologically go back in time to a period when the person felt safer.

What is an example of regression?

When we are troubled or frightened, our behaviors often become more childish or primitive.

A child may begin to suck their thumb again or wet the bed when they need to spend some time in the hospital.

Teenagers may giggle uncontrollably when introduced into a social situation involving the opposite sex.

Sublimation

Sublimation is similar to displacement, but takes place when we manage to displace our unacceptable emotions into behaviors which are constructive and socially acceptable, rather than destructive activities.

Sublimation is one of Anna Freud’s original defense mechanisms.

Sublimation for Freud was the cornerstone of civilized life, as arts and science are all sublimated sexuality.

(NB. this is a value-laden concept, based on the aspirations of European society at the end of the 1800 century).

What is an example of sublimation?

Many great artists and musicians have had unhappy lives and have used the medium of art of music to express themselves. Sport is another example of putting our emotions (e.g., aggression) into something constructive.

For example, fixation at the oral stage of development may later lead to seeking oral pleasure as an adult through sucking one’s thumb, pen or cigarette.

Also, fixation during the anal stage may cause a person to sublimate their desire to handle faeces with an enjoyment of pottery.

Rationalization

Rationalization is a defense mechanism proposed by Anna Freud involving a cognitive distortion of “the facts” to make an event or an impulse less threatening.

We do it often enough on a fairly conscious level when we provide ourselves with excuses.

But for many people, with sensitive egos, making excuses comes so easy that they never are truly aware of it.

In other words, many of us are quite prepared to believe our lies.

What is an example of rationalization?

When a person finds a situation difficult to accept, they will make up a logical reason why it has happened.

For example, a person may explain a natural disaster as “God’s will”.

Reaction Formation

Reaction formation , which Anna Freud called “believing the opposite,” is a psychological defense mechanism in which a person goes beyond denial and behaves in the opposite way to which he or she thinks or feels.

Conscious behaviors are adopted to overcompensate for the anxiety a person feels regarding their socially unacceptable unconscious thoughts or emotions.

Usually, a reaction formation is marked by exaggerated behavior, such as showiness and compulsiveness.

By using the reaction formation, the id is satisfied while keeping the ego in ignorance of the true motives.

Therapists often observe reaction formation in patients who claim to strongly believe in something and become angry at everyone who disagrees.

What is an example of reaction formation?

Freud claimed that men who are prejudiced against homosexuals are making a defense against their own homosexual feelings by adopting a harsh anti-homosexual attitude which helps convince them of their heterosexuality.

Another example of reaction formation includes the dutiful daughter who loves her mother is reacting to her Oedipus hatred of her mother.

Introjection

Introjection, sometimes called identification, involves taking into your own personality characteristics of someone else, because doing so solves some emotional difficulty.

Introjection is very important to Freudian theory as the mechanism by which we develop our superegos.

What is an example of introjection?

A child who is left alone frequently, may in some way try to become “mom” in order to lessen his or her fears.

You can sometimes catch them telling their dolls or animals not to be afraid.

And we find the older child or teenager imitating his or her favorite star, musician, or sports hero in an effort to establish an identity.

Identification with the Aggressor

Identification with the aggressor is a defense mechanism proposed by Sandor Ferenczi and later developed by Anna Freud.

It involves the victim adopting the behavior of a person who is more powerful and hostile towards them.

By internalizing the behavior of the aggressor the “victim” hopes to avoid abuse, as the aggressor may begin to feel an emotional connection with the victim which leads to feelings of empathy.

What is an example of identification with the aggressor?

Identification with the aggressor is a version of introjection that focuses on the adoption, not of general or positive traits, but of negative or feared traits.

If you are afraid of someone, you can partially conquer that fear by becoming more like them.

An extreme example is Stockholm Syndrome , where hostages establish an emotional bond with their captor(s) and take on their behaviors.

Patty Hearst was abused by her captors, yet she joined their Symbionese Liberation Army and even took part in one of their bank robberies.

At her trial, she was acquitted because she was a victim suffering from Stockholm Syndrome.

Baumeister, R. F., Dale, K., & Sommer, K. L. (1998). Freudian defense mechanisms and empirical findings in modern social psychology: Reaction formation, projection, displacement, undoing, isolation, sublimation, and denial. Journal of Personality , 66 (6), 1081-1124.

Cramer, P. (2015). Defense mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Personality Assessment , 97 (2), 114-122.

Ferenczi, S. (1933). Confusion of tongues between adults and the child (pp. 156-67) .

Freud, A. (1937). The Ego and the mechanisms of defense , London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Freud, S. (1894). The neuro-psychoses of defence . SE, 3: 41-61.

Freud, S. (1896). Further remarks on the neuro-psychoses of defense . SE, 3: 157-185.

Freud, S. (1933). New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis . London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis. Pp. xi + 240.

Freud, S. (1936). Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly , 5 (1), 1-28.

Holmes, D. S. (1978). Projection as a defense mechanism. Psychological Bulletin , 85 (4), 677.

Liberman, A., & Chaiken, S. (1992). Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 18 (6), 669-679.

Newman, L. S., Duff, K. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1997). A new look at defensive projection: Thought suppression, accessibility, and biased person perception. Journal of personality and social psychology , 72 (5), 980.

Paulhus, D. L., Fridhandler, B., & Hayes, S. (1997). Psychological defense: Contemporary theory and research. In R. Hogan, J. A. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 543-579). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50023-8

Further Reading

- Name the Defense Mechanism Activity

- BPS Article on Repression

- Cramer, P. (2015). Understanding defense mechanisms. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(4), 523-552.

- Freudian Defense Mechanisms and Empirical Findings in Modern Social Psychology: Reaction Formation, Projection, Displacement, Undoing, Isolation, Sublimation, and Denial

- Defense Mechanisms Summary Table

Sigmund Freud discussed defense mechanisms in several of his works, but he did not write a book solely dedicated to this topic. Defense mechanisms were integrated into his broader psychoanalytic theory.

Here are some key works where Freud explored defense mechanisms:

- “The Neuro-Psychoses of Defence” (1894) – This early paper introduced the concept of defense mechanisms.

- “Studies on Hysteria” (1895) – Co-authored with Josef Breuer, this book discussed repression as a defense mechanism.

- “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1900) – While primarily about dreams, this book also touched on defense mechanisms.

- “The Psychopathology of Everyday Life” (1901) – This work explored various defense mechanisms in daily life.

- “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” (1905) – This book discussed sublimation as a defense mechanism.

- “Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety” (1926) – This later work provided a more comprehensive theory of defense mechanisms.

METHODS article

The hierarchy of defense mechanisms: assessing defensive functioning with the defense mechanisms rating scales q-sort.

- 1 Department of Surgical, Medical and Molecular Pathology, Critical and Care Medicine, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

- 2 McGill University Department of Psychiatry at the Institute of Community and Family Psychiatry, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada

The psychodynamic concept of defense mechanisms is nowadays considered by professionals with various theoretical orientations of great importance in the understanding of human development and psychological functioning. More than half century of empirical research has demonstrated the impact of defensive functioning in psychological well-being, personality organization and treatment process-outcome. Despite the availability of a large number of measures for their evaluation, only a few instruments assess the whole hierarchy of defenses, based on the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales (DMRS), which arguably offers an observer-rated gold standard of assessment. The present article illustrates the theoretical and methodological background of the DMRS-Q, the Q-sort version of the DMRS for clinical use. Starting from the definition and function of the 30 defense mechanisms included in the hierarchy, we extracted 150 items that captured a full range of defensive manifestations according to the DMRS theory. The DMRS-Q set is described in this paper with reference to the DMRS manual. Directions are also provided for using the DMRS-Q online software for the free and unlimited coding of defense mechanisms. After each coding, the DMRS-Q software provides a report including qualitative and quantitative scores reflecting the individual’s defensive functioning. Qualitative scores are displayed as the Defensive Profile Narratives (DPN), while quantitative scores are reported as Overall Defensive Functioning (ODF), defensive categories, defense levels, and individual defense mechanisms. Syntax for the scoring is displayed in the results and a clinical vignette of a psychotherapy session coded with the DMRS-Q is provided. The DMRS-Q is an easy-to-use, free, computerized measure that can help clinicians in monitoring changes in defense mechanisms, addressing therapeutic intervention, fostering symptoms decreasing and therapeutic alliance. Moreover, the DMRS-Q might be a valid tool for teaching the hierarchy of defense mechanisms and increase the observer-rated assessment of this construct in several research fields.

Introduction

The psychodynamic concept of defense mechanisms, defined as automatic psychological mechanisms that mediate the individual’s reaction to emotional conflicts and to internal or external stressors ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ; Perry, 2014 ), has been extensively studied since its first appearance in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory ( Freud, 1894 ). After a century of clinical and theoretical work, and a quarter century of empirical research, an assessment of defense mechanisms was included in an Axis for the assessment of defense mechanisms in the DSM-IV ( Cramer, 1987 , 2015 ; Kernberg, 1988 ; American Psychiatric Association, 1994 ; Hoffman et al., 2016 ). The main contribution to the gold-standard approach to the study of defense mechanisms has been provided by the theory of defensive adaptiveness and the hierarchical organization of defense mechanisms proposed by Vaillant (1971 , 1992) and operationalized by Perry (1990) . In his extensive and valuable work, Vaillant described excellent clinical vignettes of defenses as they operate in real life – both in momentary examples, and those that recur over time – and integrated findings from several longitudinal studies demonstrating the evolution of defense mechanisms over the life cycle. With the development of the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales (DMRS), Perry has provided a comprehensive, accurate and valid observer-rated methodology for assessing individual’s defensive functioning based on the whole hierarchy of defense mechanisms ( Perry and Henry, 2004 ). In recent years, the authors of this paper have adapted the DMRS theory to additional assessment methods, by developing both the Q-sort version (DMRS-Q; Di Giuseppe et al., 2014 ) and the self-report version (DMRS-SR-30; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020a ) of the DMRS. Our main aim was to provide new measures based on the DMRS theory of defense mechanisms applicable in different clinical or research contexts, without the requirement of training for their valid and reliable use ( Békés et al., 2021 ; Conversano and Di Giuseppe, 2021 ). In this article, we describe theoretical background, coding procedure, scoring system and results interpretation of the DMRS-Q, a computerized observer-rated Q-sort for the assessment of defense mechanisms in clinical setting.

The Hierarchy of Defense Mechanisms

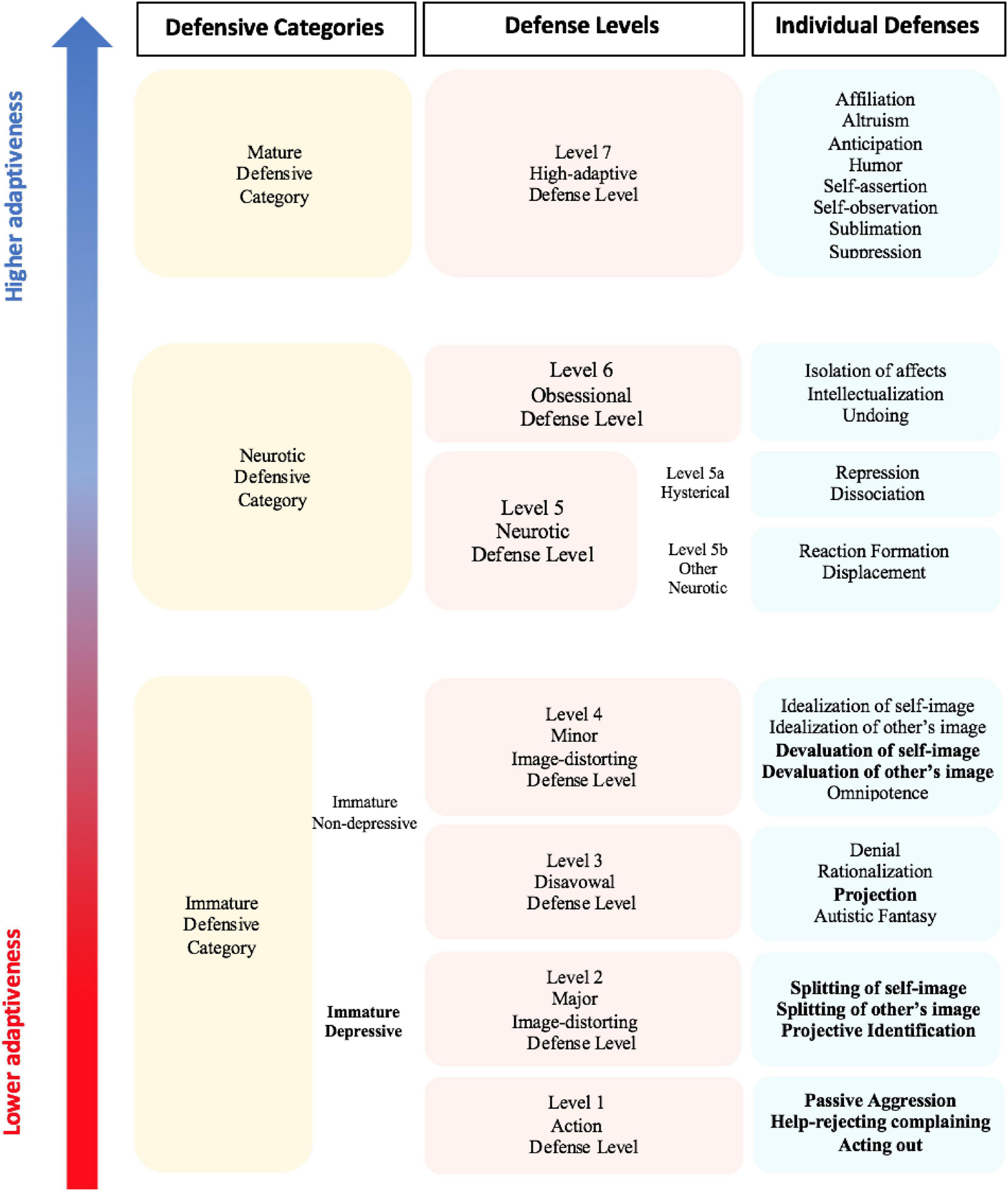

All DMRS-based measures refer to the generally accepted hierarchy of defense mechanisms ( American Psychiatric Association, 1994 , 2013 ; Hoglend and Perry, 1998 ; Lingiardi et al., 1999 ; Drapeau et al., 2003 ; Hilsenroth et al., 2003 ; Perry, 2014 ; Di Giuseppe et al., 2019 , 2021 ; Tanzilli et al., 2021 ). A graphical summary of the hierarchy of defense mechanisms is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. The DMRS hierarchical organization of defensive categories, defense levels and individual defenses. Table adapted from Perry and Bond (2012) , Table 1 . So-called depressive defenses are in bold.

This hierarchy describes 30 defense mechanisms organized into seven defense levels, each of which has some general functions that the constituent defenses share in how they protect the individual from anxiety, or a sense of threat from internal or external sources, or conflicts.

In addition to the seven defense levels, there is level 0, describing defensive dysregulation, the so-called Psychotic Defenses Level. Defenses belonging to this defense level are not included in the DMRS manual although they can be assessed using another DMRS-derived measure, the Psychotic-DMRS (P-DMRS; Berney et al., 2014 ; Boldrini et al., 2020 ). Defense levels can be further organized into three defensive categories of relatively similar degree of maturity, often used for describing in summary the individual defensive functioning. The three defensive categories, from the least to the most adaptive, respectively, include immature, neurotic and mature defenses. The immature defensive category is the most populated and includes all defenses belonging to action, disavowal and both image distortion defense levels. This defensive category can be further divided into two subcategories. The first is named depressive defenses, including acting out, help-rejecting complaining, passive aggression, splitting of self-image, splitting of other’s image, projective identification, projection, devaluation of self-image, and devaluation of other’s image. The second subcategory is the non-depressive defenses, including denial, rationalization, autistic fantasy, omnipotence, idealization of self-image, and idealization of other’s image. Greater reliance on immature defenses informs on the subject’s defensive vulnerability and his or her scarce awareness of both emotional and cognitive sides of internal conflicts or external stressful situations. These defenses inhibit awareness of unacceptable ideas, feelings, and actions, bypassing them to protect oneself from feeling threatened.

The neurotic defensive category represents the middle-range of adaptiveness and includes all defenses belonging to neurotic and obsessional defense levels. High use of these middle-range defenses describes the individual’s ability to deal with either the emotional or the cognitive side of internal or external stressors, which can be handled one at a time. These defenses help the individual in keeping out of awareness parts of the conflict (e.g., associated feelings, desires and thoughts), which would generate intolerable anxiety if perceived as an integrated psychological experience. Finally, the mature defensive category corresponds to the high-adaptive defense level and includes the most adaptive defense mechanisms, which overlap with what are called positive coping strategies in other theoretical frameworks. High use of mature defenses fosters the integrated and partially aware experience of feelings, ideas, desires and thoughts associated to an internal conflict or external stressful situation. These defenses help the individual in dealing with his or her psychologically stressful experiences by integrating affects with ideas, therefore optimizing and possibly resolving the internal or external cause of distress ( Vaillant, 1977 , 1992 ). This tripartite model of DMRS hierarchical organization of defenses is often used for summarizing the defensive maturity of an individual by looking at the proportional scores obtained in each of the three defensive categories.

For a deeper understanding of individual’s defensive functioning, the seven defense levels can be used as the generally accepted hierarchical organization of defense mechanisms ( American Psychiatric Association, 1994 ). Defense levels differentiate one from another for their defensive function and level of adaptiveness, which are described in Table 1 . Their assessment may inform about the most used defensive patterns, which reveal what defensive function is more frequently activated in response to internal conflicts or external stressors. For example, two individuals who use 40% of defenses belonging to the neurotic defensive category can have a very different defensive profile depending on whether they use a more obsessional or neurotic defense level. Similarly, high use of action and major image-distorting defense levels is very different from high use of disavowal and minor image-distorting defense levels, although they are all included in the immature defensive category. Furthermore, these differentiations among individuals’ defensive functioning are extremely evident when we look at the deepest level of investigation, the individual’s use of 30 individual defense mechanisms.

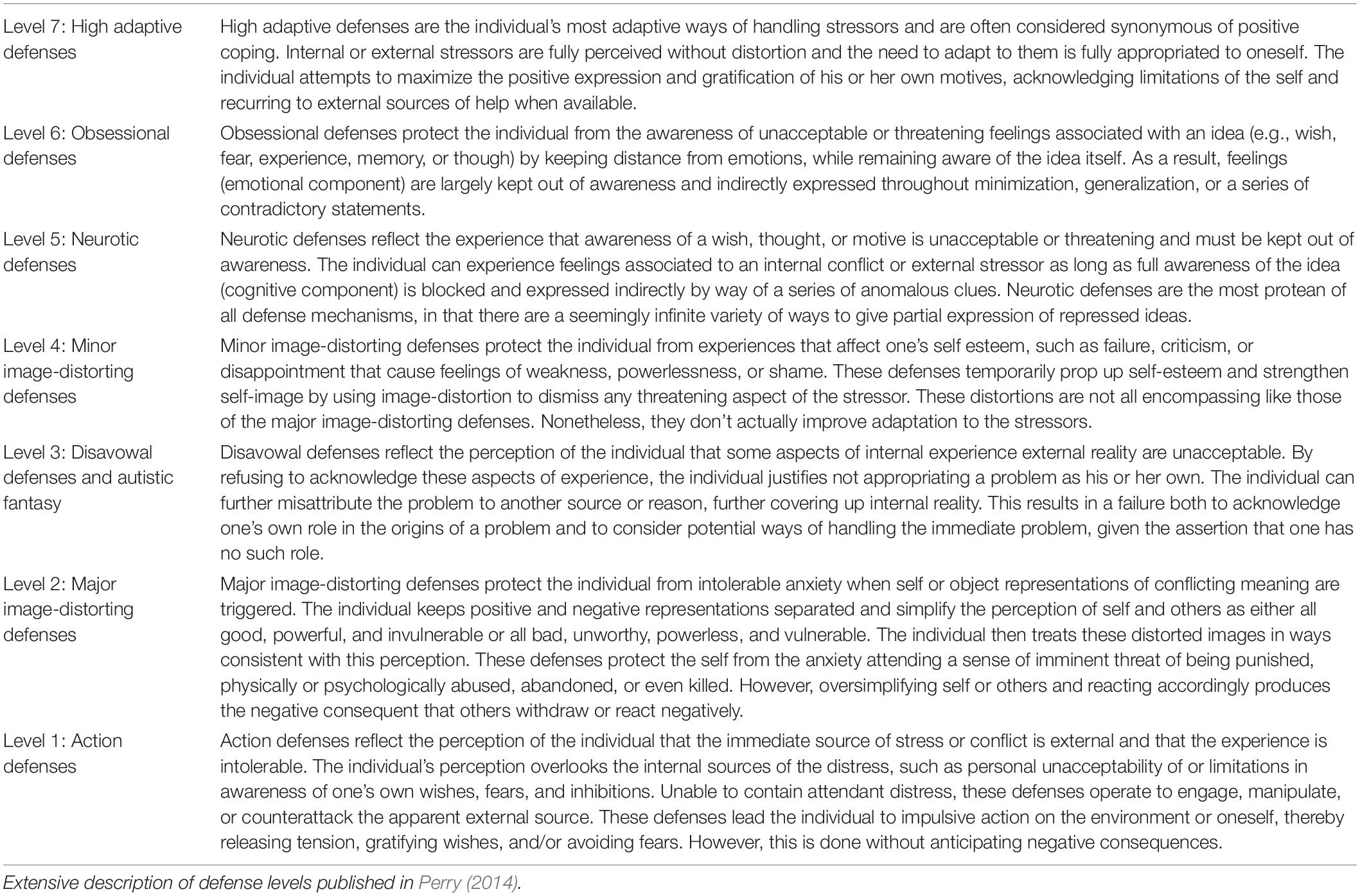

Table 1. The defensive function of the seven hierarchically ordered defense levels.

Training individuals to rate defenses reliably is time consuming, as are making the ratings themselves, both of which limit the use of such ratings in clinical setting. While the DMRS is necessary for some types of research, we developed the DMRS-Q to meet the needs of a quicker, more user-friendly computerized tool for the assessment of defense mechanisms in clinical setting ( Di Giuseppe et al., 2020b , c ).

The present article aims to illustrate the DMRS-Q and its assessment and scoring methodology. We will provide the definition and function of 30 defense mechanisms as reported in the DMRS manual ( Perry, 1990 ) and present the five DMRS-Q items corresponding to each defense mechanisms. Moreover, we will provide instructions for coding defenses with the DMRS-Q online software 1 and syntax for the scoring. Finally, we will provide directions for data interpretations of the DMRS-Q qualitative and quantitative output.

Measure Development

Based on the DMRS definition and function, and discriminations from near-neighbor defenses, we developed a pool of 300 items – 10 statements for each defense mechanism – that refer to verbal and nonverbal expressions, distorted perceptions, personal mental states, relational dynamics, and way of coping that emerge on occasions when the subject experiences internal or external stress or conflict. A group of researchers trained on the DMRS was asked to indicate the five items for each defense mechanism that best captured a full range of manifestations according to the DMRS criteria. Following reviewers’ comments and basing on item’s clarity, simplicity, and non-redundancy, we selected the best five items for each defense mechanisms obtaining a final set of 150 items that constitute the DMRS-Q. We decided to select the DMRS-Q item pool, based on the coverage of manifestations of each DMRS defense, rather than on maximizing internal consistency of the items to overall defense score. This methodological approach was based on author’s hypothesis that reproducing the widely validated DMRS in an easy-to-use Q-sort version would guarantee strong psychometric properties because of the gold-standard theoretical background. Although we are aware that this is far from the usual methodological approach applied for the development of new psychometric tools, our preliminary analyses on validity and reliability of the DMRS-Q ( Di Giuseppe et al., 2014 ; Békés et al., 2021 ; Tanzilli et al., 2021 ) confirmed our hypothesis on the importance of a strong theoretical base for a measure with statistically relevant properties.

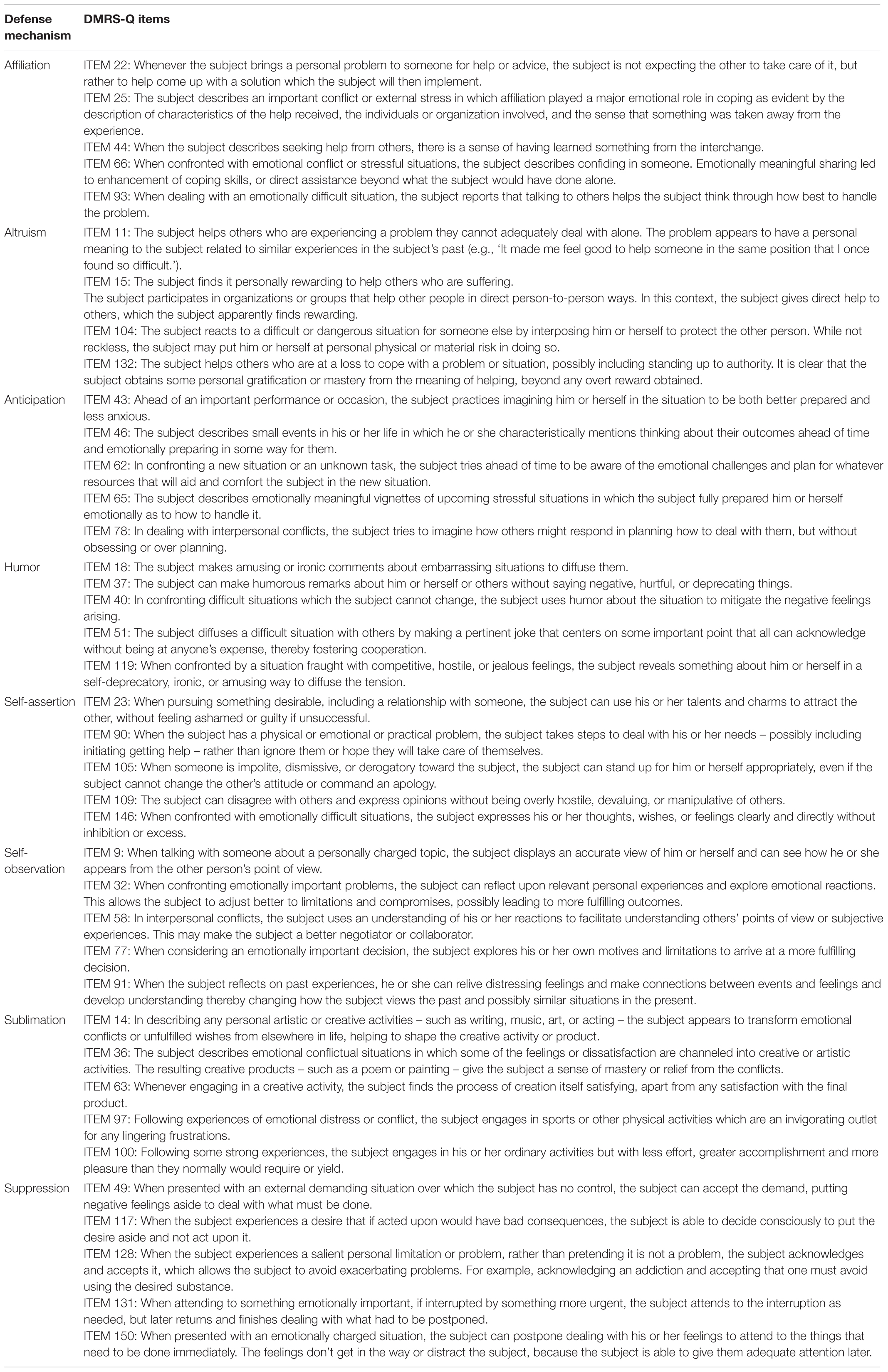

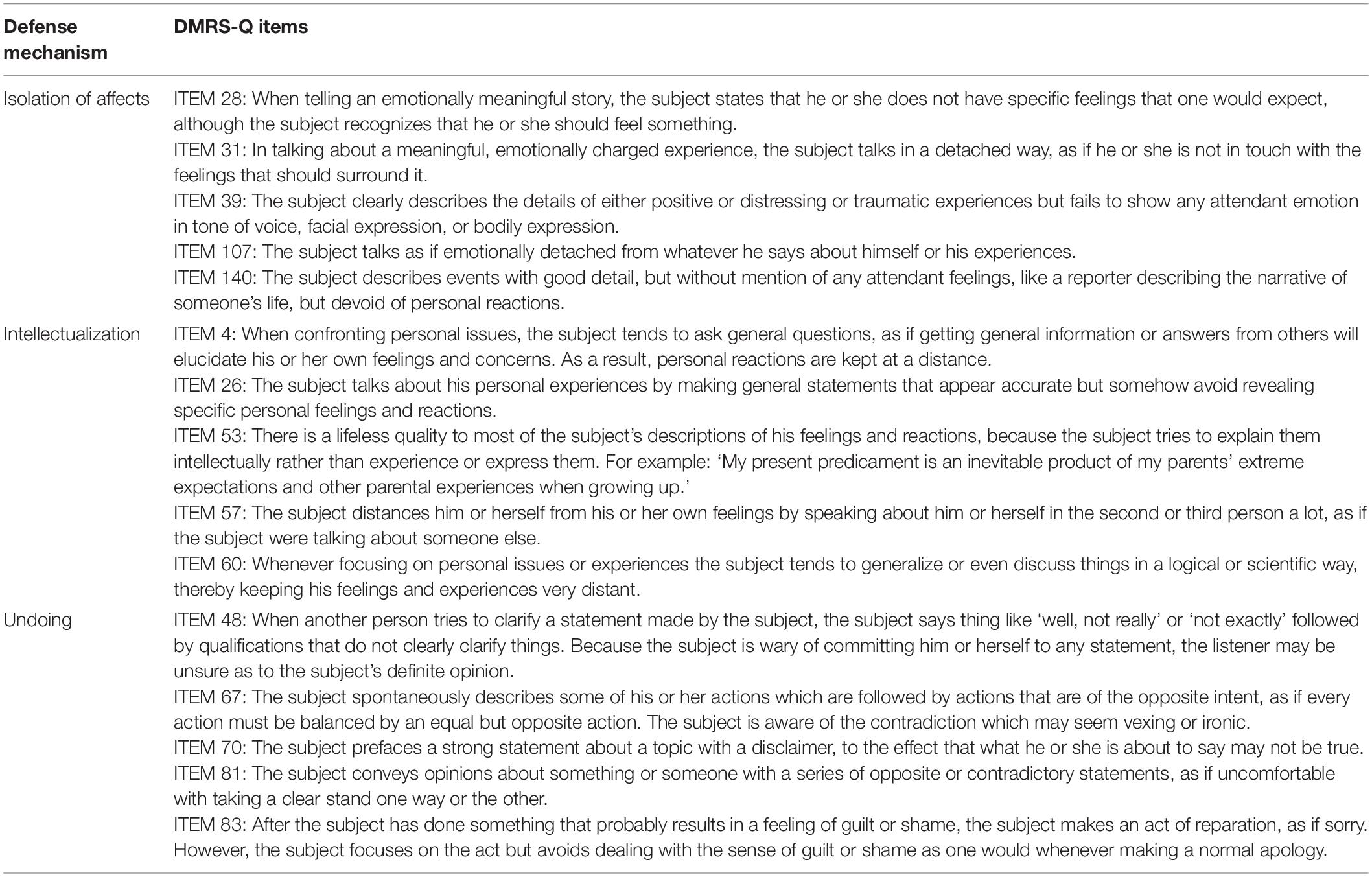

Definitions and Function of Defense Mechanisms and Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-Sort Items

The DMRS-Q provides five items for each of the 30 defense mechanisms included in the hierarchy. A comprehensive overview of definitions, functions and DMRS-Q items is provided below. Tables 2 – 8 display DMRS-Q items for each defense included in each defense level; they are reported in descending order of defensive maturity. The following descriptions of the individual defenses are reproduced or adapted from the DMRS manual ( Perry, 1990 ), with permission of the author, JP to provide the definitional basis for the DMRS-Q items in Tables 2 – 8 .

Table 2. High-adaptive defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses affiliation, altruism, anticipation, humor, self-assertion, self-observation, sublimation, and suppression.

Table 3. Obsessional defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses isolation of affects, intellectualization and undoing.

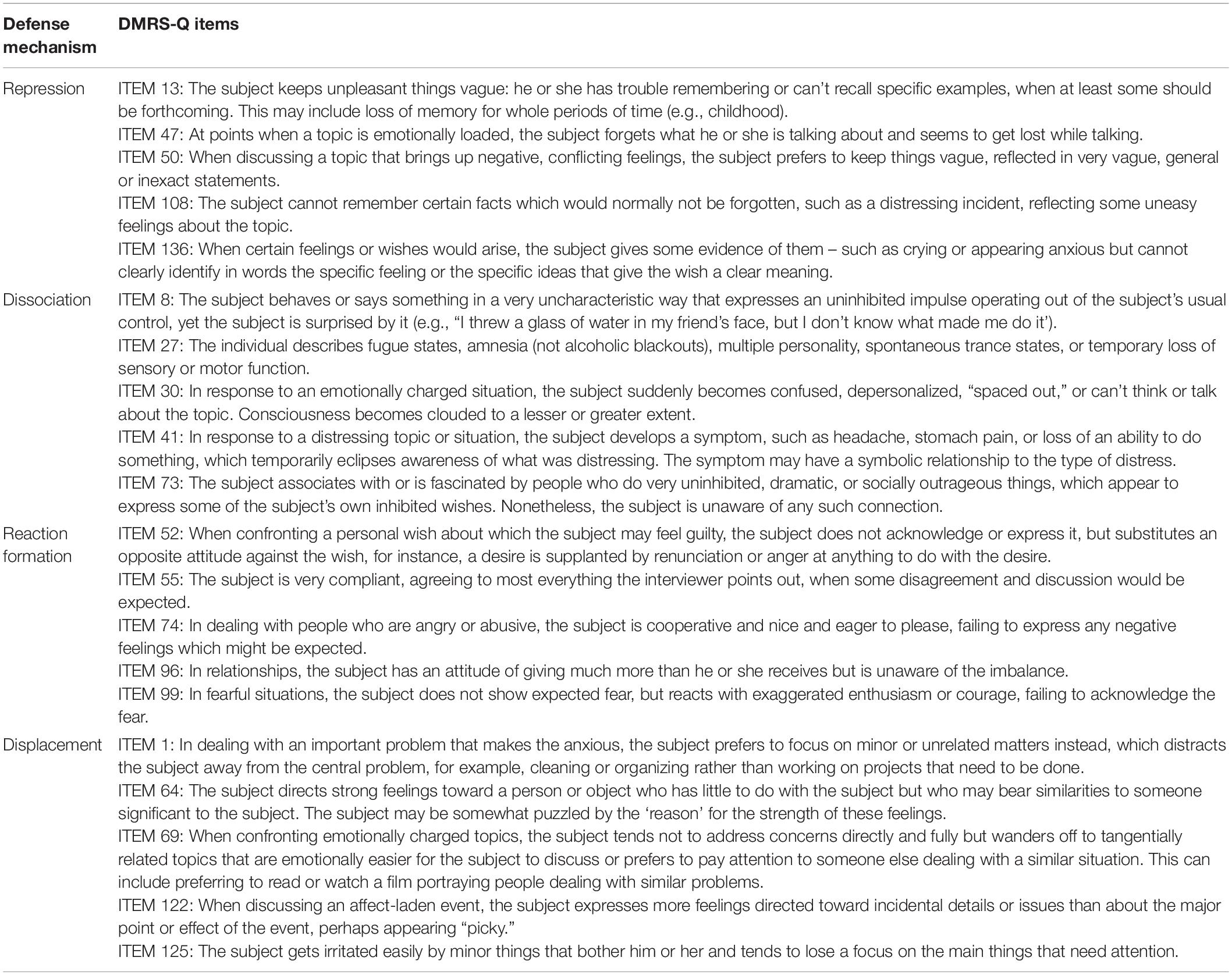

Table 4. Neurotic defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses repression, dissociation, reaction formation, and displacement.

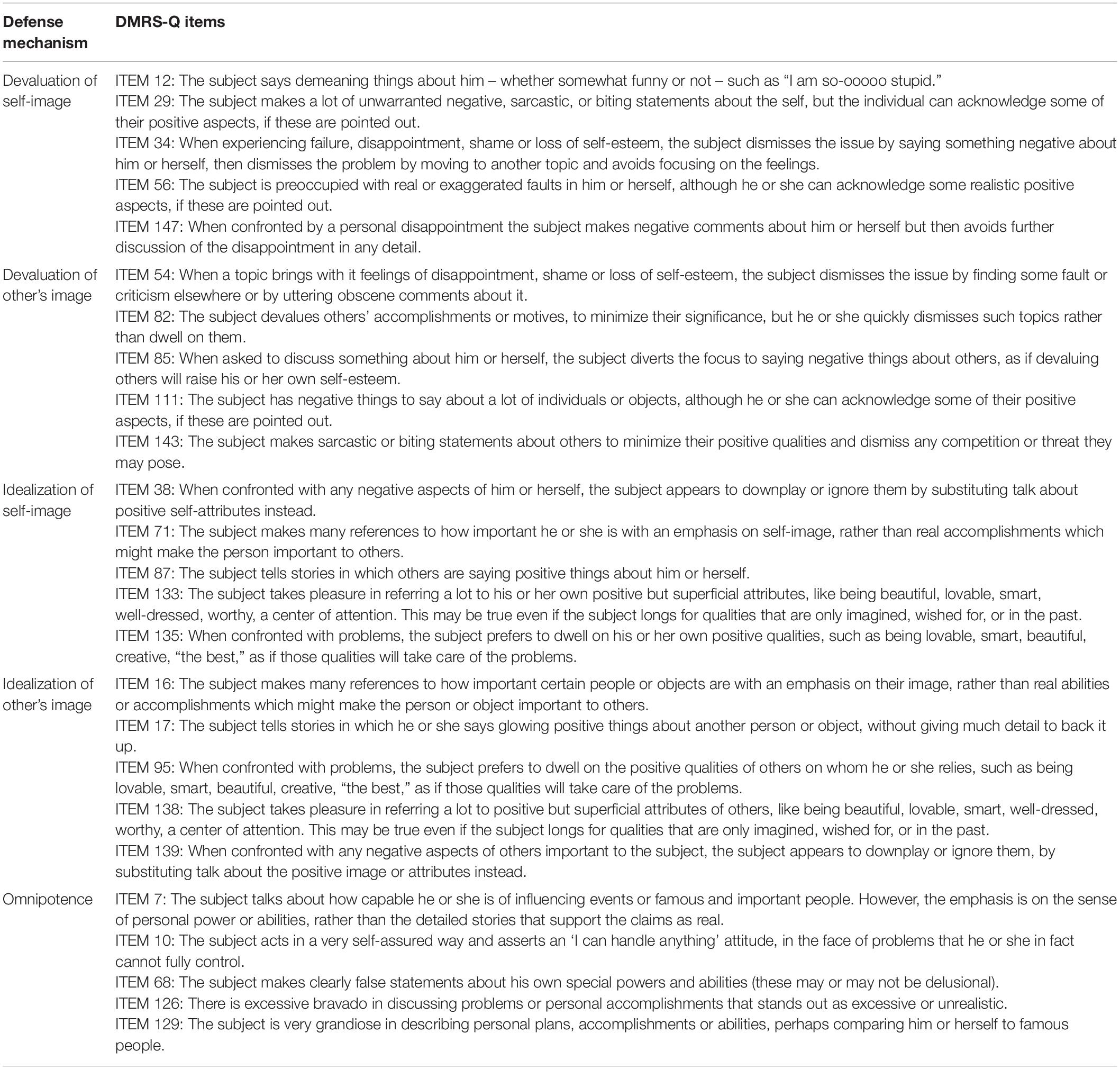

Table 5. Minor image-distorting defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses devaluation of Self-image, devaluation of other’s image, idealization of self-image, idealization of other’s image, and omnipotence.

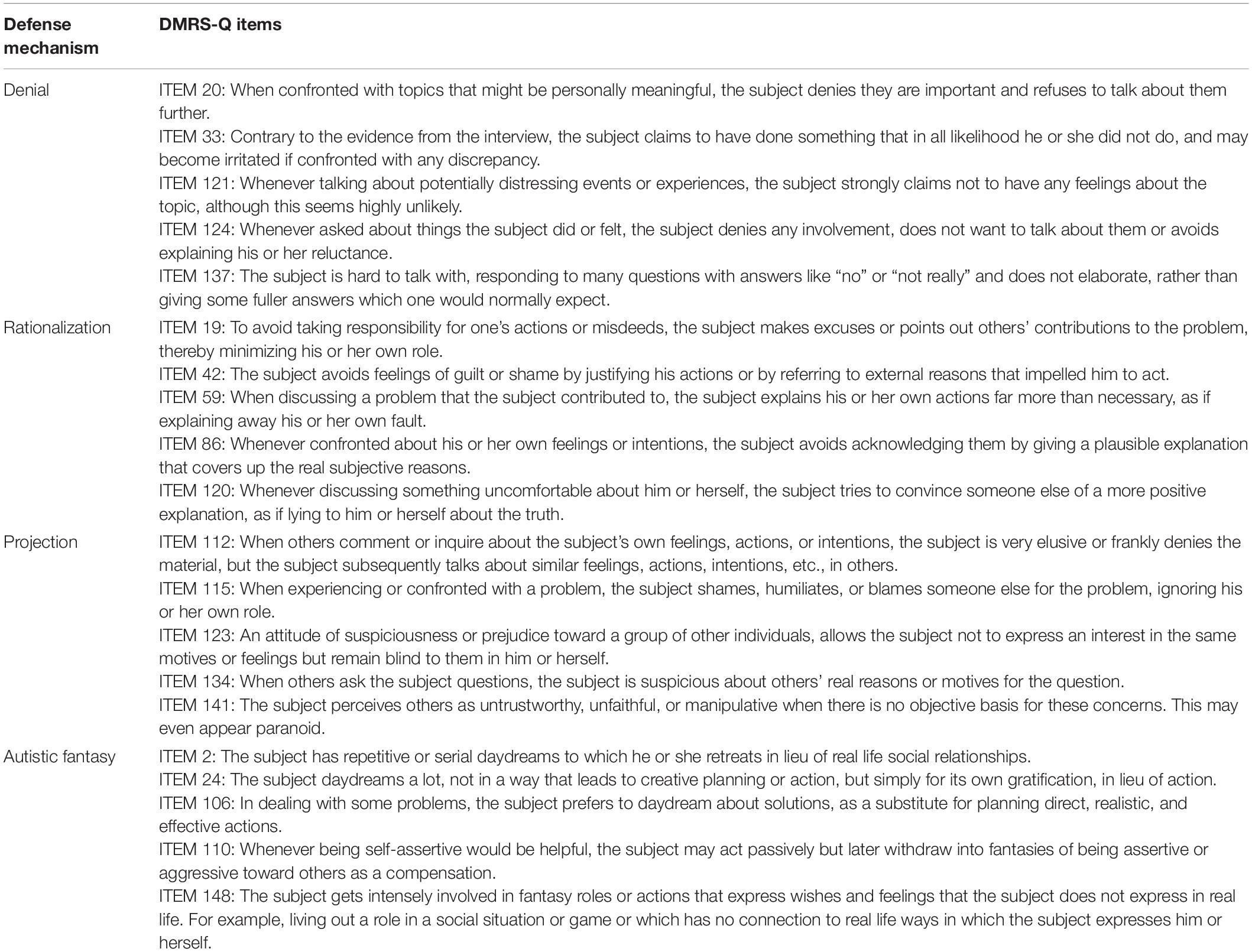

Table 6. Disavowal defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses denial, rationalization, projection, and autistic fantasy.

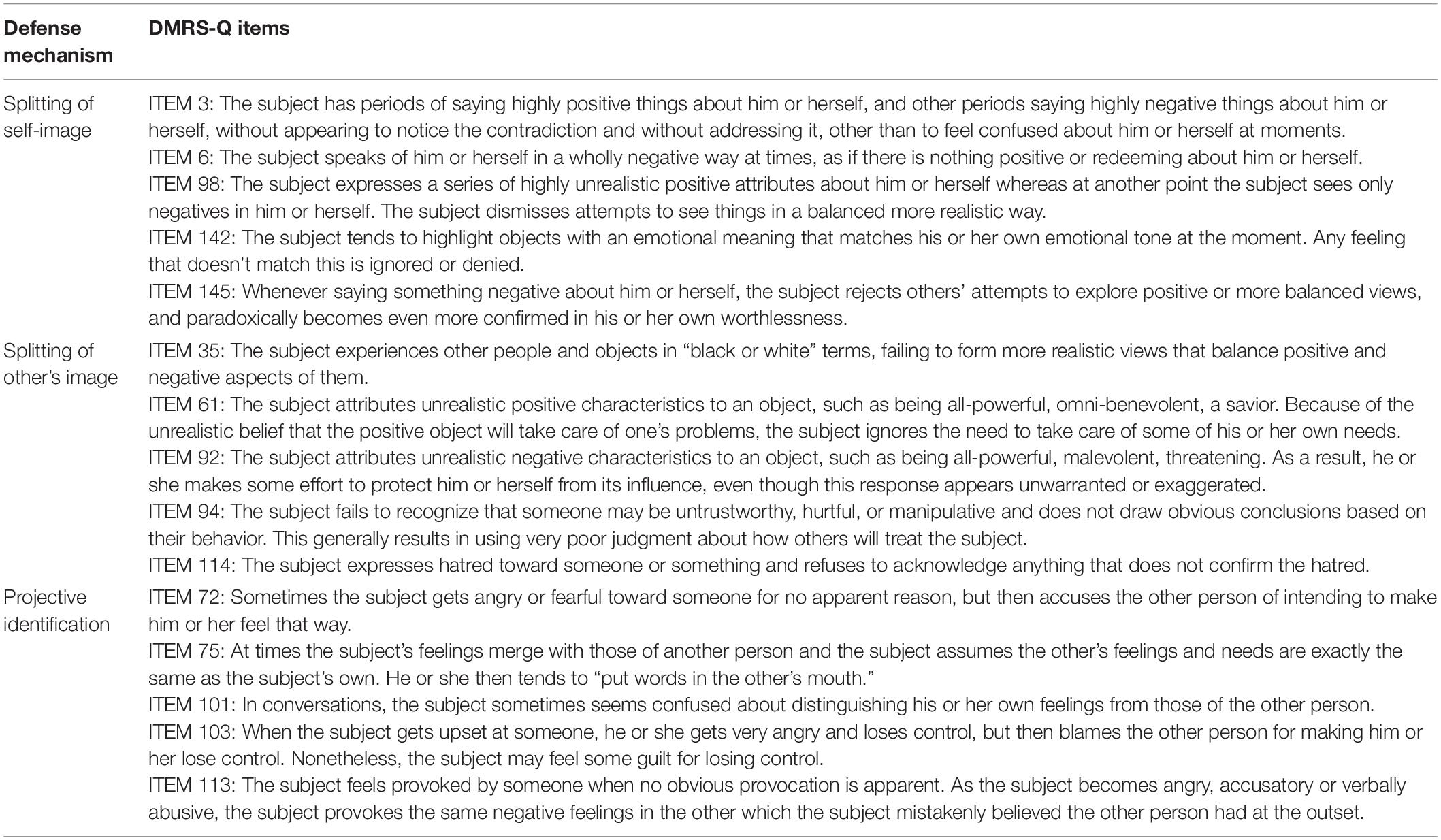

Table 7. Major image-distorting defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses splitting of self-image, splitting of other’s image, and projective identification.

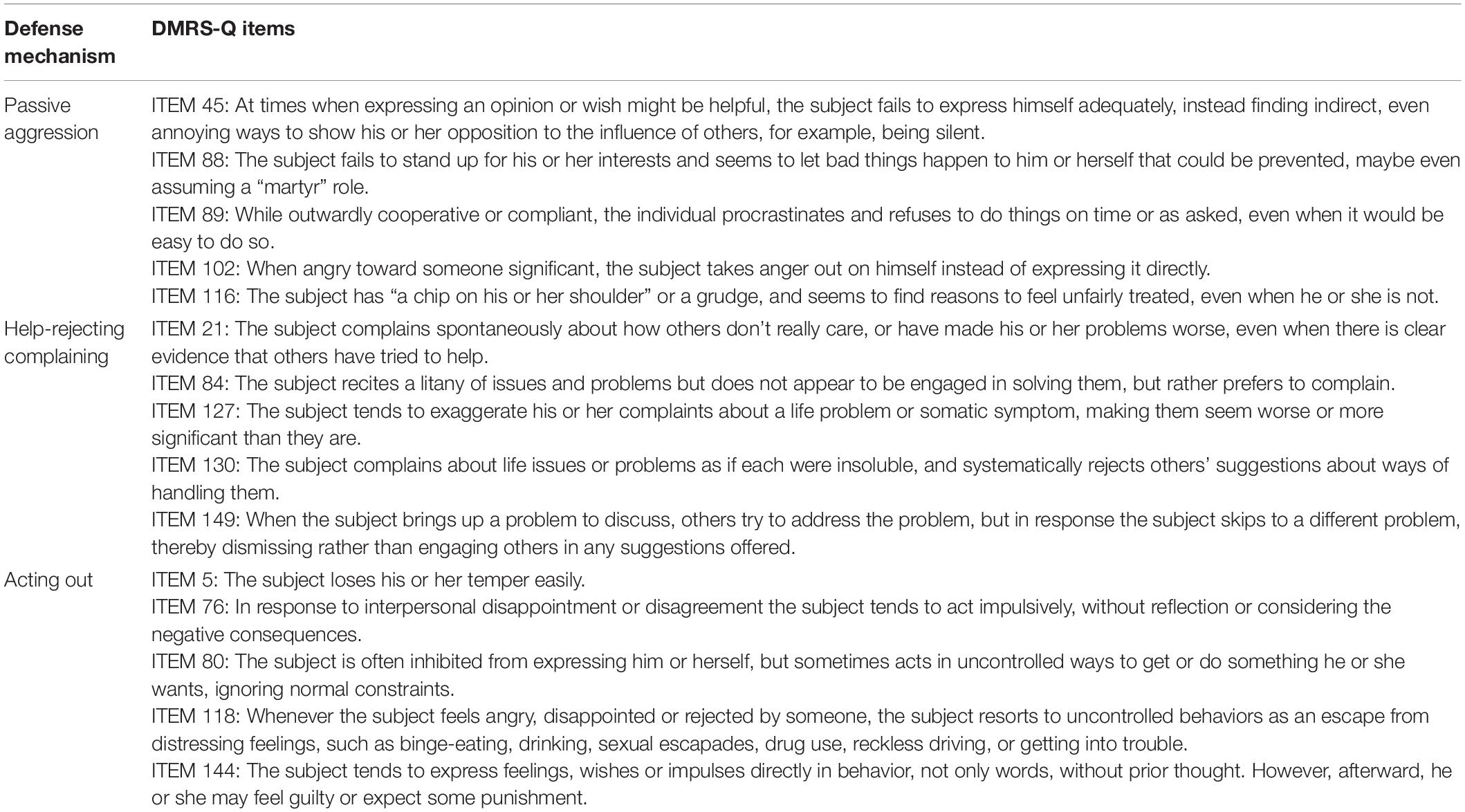

Table 8. Action defense level: Definition, function and DMRS-Q items of defenses acting out, help-rejecting complaining, and passive aggression.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Affiliation

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by turning to others for help or support. By affiliating with others, the individual can express him or herself, confide problems, and feel less alone or isolated with a conflict or problem. This may also result in receiving advice or concrete help from the “auxiliary ego” that improves the individual’s ability to cope. Confiding leads to an increase in the individual’s coping capacity as the other individual supplies emotional validation and support. Affiliation does not include trying to make someone else responsible for dealing with one’s own problems, nor does it imply coercing someone to help, or acting helpless to elicit help. Affiliation is not shown simply by belonging to an organization (e.g., church, social club, Alcoholics Anonymous) or by seeing a counselor or therapist. Rather it is demonstrated by the give and take around conflicts and problems that occurs in the context of belonging to the organization, or by the confiding with others.

Affiliation allies the individual’s emotional attachment needs with the wish to cope effectively with internal conflict or external stressors. The ability to cope is enhanced by seeking support from others, while attachment needs are also satisfied. Others may enhance the individual’s repertoire of ego skills by help with advice, modeling, planning, judgment, role playing, practicing, etc. Usually this is accompanied by a reduction in subjective tension achieved through expressing one’s feelings and sharing one’s conflicts.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Altruism

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by dedication to fulfilling the needs of others, in part as a way of fulfilling his or her own needs. By using altruism, the individual receives some partial gratification either vicariously or as a response from others. The subject is usually aware to some extent that his or her own needs or feelings underlie altruistic actions. There may also be a direct reward or overt self-interested reason for the subject’s altruistic actions. To rate altruism present, there must be a clear, demonstrable, functional relationship between the individual’s feelings and the altruistic response.

Altruism gratifies social and attachment needs while dealing with emotional conflict through helping others. In many cases, the conflict revolves around distress over past examples of confronting stressful situations for which one needed help that was somehow unavailable or insufficient. Altruism channels affects, such as anger, and experiences, such as powerlessness, into socially helpful responses that also enhance the individual’s sense of mastery over the past.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Anticipation

The individual mitigates emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by not only considering realistic, alternative solutions and anticipating emotional reactions to future problems, but experiencing the future distress by mentally bringing the distressing ideas and affects together. This rehearsal allows the individual to prepare a better adaptive response to the anticipated conflict or stressor.

Using anticipation allows the individual to mitigate the effects of future stressors or conflicts. It requires being able to tolerate the anxiety attendant to imagining how a future situation may be distressing. By affective rehearsal (e.g., ‘how will I feel when this occurs?’) and planning future responses, the subject decreases distressing aspects of the future stressor. Anticipation also increases the likelihood of positive external outcomes and more positive emotional responses.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Humor

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by emphasizing the amusing or ironic aspects of the conflict or stressor. Humor tends to relieve the tension around conflict in a way that allows everyone to share in it, rather than being at one person’s expense, as in derisive or cutting remarks. An element of self-observation or truth is often involved.

Humor allows some expression of affects and wishes that are involved with conflict or stressor. Whenever conflict or external stressors block full expression of the affects or satisfaction of wishes, humor allows some symbolic expression of them and of the source of the conflict. The frustration emanating from the conflict is transiently relieved in a way that both self and others can smile or laugh at. This is especially evident around issues of the human condition in which certain stressors are inescapable.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Self-Assertion

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by expressing one’s feelings and thoughts directly to achieve goals. Self-assertion is not coercive or indirect and manipulative. The goal or purpose of the self-assertive behavior is usually made clear to all parties affected by it.

Self-assertion deals with emotional conflict through the direct expression of one’s feelings or wishes, and thereby relieves the anxiety or distress that occurs whenever internal or external countervailing forces prevent expression. Self-assertion does not require that the individual get his or her own way to be successful as a defense or adaptive response. Rather, it is also emotionally useful because it allows the individual to function (1) without the anxiety or tension that builds whenever feelings and wishes are unexpressed and (2) without a sense of shame or guilt for not speaking up for oneself in emotionally conflictual situations. The emotional consequences are worse when self-assertion is blocked by internal prohibitions, rather than by external factors alone, such as by a domineering person in authority.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Self-Observation

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by reflecting on his or her own thoughts, feelings, motivation, and behavior. The person can “see himself as others see him” in interpersonal situations, and as a result is better able to understand other people’s reactions to him or her. The defense is not synonymous with simply making observations or talking about oneself.

This defense allows the person to make the best adaptation to the demands of external reality based on having an accurate view of one’s own affects, wishes and impulses, and behavior. While self-observation does not change one per se , it is a precursor for seeking better adaptations of internal states to external reality. This defense allows the individual to grow and adapt better as he or she deals with stress.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Sublimation

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by channeling rather than inhibiting potentially maladaptive feelings or impulses into socially acceptable behavior. This defense is to be rated present only when a strong functional relationship can be demonstrated between the feelings and response pattern. Classic examples of the use of sublimation are sports and games used to channel angry impulses, or artistic creation that expresses conflicted feelings.

Sublimation allows the expression of wishes, impulses, or affects that the subject voluntarily inhibits because of their potentially negative social repercussions. The subject channels them instead into socially acceptable expression. The original aims and objects of the impulses, wishes, and affects are often modified considerably, resulting in a creative activity or product. For example, a hostile-competitive urge may be channeled into competitive sports or work, or sexual impulses may be expressed through creative dance or art. The result of sublimation is that the original impulses, etc. are allowed some expression while the resulting activity or product may also bring some positive social approval or reward.

High-Adaptive Defense Level: Suppression

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by voluntarily avoiding thinking about disturbing problems, wishes, feelings, or experiences temporarily. This may entail putting things out of one’s mind until the right time to deal with them: it is postponing not procrastinating. Suppression may also entail avoiding thinking about something at the time because it would distract from engaging in another activity which one must do (e.g., not dwelling on tangential problems in order to deal with one pressing problem). The individual can call the suppressed material back to conscious attention readily, since it is not forgotten.

Suppression keeps both the idea and affect associated with a stressor out of awareness in the service of attending to something else; however, suppressed material may be voluntarily brought back into full awareness. Distressing feelings are acknowledged but dealing with them is postponed until the subject feels more able or the timing is more appropriate. Neurotic anxiety is minimized, since the material is not repressed, although anticipatory anxiety may still be present until the stressor is dealt with.

Obsessional Defense Level: Isolation of Affects

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by being unable to experience simultaneously the cognitive and affective components of an experience, because the affect is kept from consciousness. In the defense of isolation, the subject loses touch with the feelings associated with a given idea (e.g., a traumatic event) while remaining aware of the cognitive elements of it (e.g., descriptive details). Only the affect is lost or detached while the idea is conscious. It is the converse of repression, where the affect is retained but the idea is detached and unrecognized. Sometimes the affect can be detached temporarily from its associated idea. The affect is felt later without association to the original experience and idea. Instead, there is an intervening neutral interval between cognizance of the idea and experience of the associated affects.

Individuals who feel threatened by or anxious over the conscious experience of feelings can still deal with the related ideas and events comfortably when their associated affects are separated and kept out of awareness. Very often the isolated affects are associated with anxiety, shame, or guilt that would emerge if experienced directly. The tradeoff for avoiding the associated anxiety, shame, or guilt is that the individual misses out on experiencing the feelings in a way that adds evaluative information and which may be useful in making choices.

Obsessional Defense Level: Intellectualization

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by the excessive use of abstract thinking to avoid disturbing feelings.

Intellectualization is a defense against affects or impulses in which the idea representing the affect or impulse is kept conscious and expressed as a generalization, thereby detaching or distancing the subject from the affect or impulse itself. The felt quality of emotions is lost, as is the urge in any impulse. The cognitive elements remain conscious, although in generalized or impersonal terms. The subject commonly refers to his or her experience in general terms or in the second or third person. One does not have to be bright or intelligent to use intellectualization. It is simply a cognitive strategy for minimizing the felt importance of problems in one’s affective life. Like other defenses, it can sometimes be seen in those with intellectual disabilities and organic brain syndromes.

Obsessional Defense Level: Undoing

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by behavior designed to symbolically make amends for negate previous thoughts, feelings, or actions.

In this defense the subject expresses an affect, impulse or commits an action which elicits guilt feelings or anxiety. He or she then minimizes the distress by expressing the opposite effect, impulse, or action. The act of reparation then removes the individual from experiencing the conflict. In conversation the subject’s statements are immediately followed by qualifications bearing the opposite meaning from the original statement. To the observer this coupling of statement with contradictory statement may make it difficult to see what the subject’s primary feeling or intention really is. Misdeeds may be followed by acts of reparation to the intended object of the misdeed. The subject appears compelled to erase or undo his or her original action.

Neurotic Defense Level: Repression

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by being unable to remember or be cognitively aware of disturbing wishes, feelings, thoughts or experiences.

Repression is a defense that protects the subject from being aware of what he is experiencing or has experienced in the past. The subject may experience a particular affect, impulse, or desire, but the actual awareness of what it is, that is, the idea associated with it, remains out of awareness. While the emotional elements are clearly present and experienced, the cognitive elements remain outside of consciousness.

Neurotic Defense Level: Dissociation

The individual deal with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by a temporary alteration in the integrative functions of consciousness or identity. In the defense of dissociation, a particular affect or impulse which the subject is not aware of operates in the subject’s life out of normal awareness. Both the idea and associated affect or impulse remain out of awareness but are expressed by an alteration in consciousness. While the subject may be dimly aware that something unusual takes place at such times, full acknowledgment that his or her own affect or impulses are being expressed is not made. Dissociation may result in a loss of function or in uncharacteristic behavior.

Dissociated material is commonly experienced as too threatening, too conflict-laden, or too anxiety-provoking to be allowed into awareness and fully acknowledged by the subject. Examples of common threatening material include recollection of a trauma with attendant fear of death and feelings of powerlessness, or a sudden impulse to kill an intimate associate. Dissociation allows expression of the affect or impulse by altering consciousness which allows the individual to feel less guilty or threatened.

Neurotic Defense Level: Reaction Formation

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by substituting behavior, thoughts, or feelings that are diametrically opposed to his or her unacceptable thoughts or feelings.

In reaction formation an original impulse or affect is deemed unacceptable by the subject and an unconscious substitution is made. Feelings, impulses, and behaviors of opposite emotional tone are substituted for the original ones. The observer does not see the alteration, per se , but only the end product. By supplanting the original unacceptable feelings by its opposite, the subject avoids feelings of guilt. In addition, the substitution may gratify a wish to feel morally superior. Reaction formation is reasonably inferred when a subject reacts to an event with an emotion opposite in tone to the usual feelings evoked in people.

Neurotic Defense Level: Displacement

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by generalizing or redirecting a feeling about or a response to an object onto another, usually less threatening, object. The person using displacement may or may not be aware that the affect or impulse expressed toward the displaced object was really meant for someone else.

Displacement allows the expression of an affect, impulse, or action toward a person or other object with some similarity to the actual object which initially aroused the affect or impulse. The affect or impulse is fully expressed and acknowledged but is misdirected to a less conflictual target. Displacement allows more expression and gratification, albeit toward the wrong targets, than other neurotic level defenses.

Minor Image-Distorting Defense Level: Devaluation

The individual deals with emotional conflicts or internal or external stressors by attributing exaggeratedly negative qualities to oneself or others.

Devaluation refers to the use of derogatory, sarcastic, or other negative statements about oneself or others to boost self-esteem. Devaluation may fend off awareness of wishes or the disappointment when wishes go unfulfilled. The negative comments about others usually cover up a certain sense of vulnerability, shame or worthlessness which the subject experiences vis a vis expressing his own wishes and meeting his own needs.

Minor Image-Distorting Defense Level: Idealization

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by attributing exaggerated positive qualities to self or others.

In the defense of idealization, the subject describes real or alleged relationships to others (including institutions, belief systems, etc.) who are powerful, revered, important, etc. This usually serves as a source of gratification as well as protection from feelings of powerlessness, unimportance, worthlessness, and the like. The defense accomplishes a sort of alchemy of worthiness by association. The subject believes certain others to be good and powerful in an exaggerated way and while able to acknowledge factual aspects of any faults or shortcomings in the idealized person, they dismiss their significance, thereby preserving a sterling image of the person, or object.

Minor Image-Distorting Defense Level: Omnipotence

Omnipotence is a defense in which the subject responds to emotional conflict or internal and external stressors by acting superior to others, as if one possessed special powers or abilities.

This defense commonly protects the subject from a loss of self-esteem that is a consequence whenever stressors trigger feelings of disappointment, powerlessness, worthlessness, and the like. Omnipotence subjectively minimizes the latter experiences, although they may remain objectively obvious to others. Self-esteem is artificially propped up at the expense of positively distorting one’s self-evaluation in response to real experiences which bring up contrary feelings.

Disavowal Defense Level: Denial

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by refusing to acknowledge some aspect of external reality or of his or her experience that would be apparent to others. The subject actively denies that a feeling, behavioral response, or intention (regarding the past or present) was or is not present, even though its presence is considered more than likely by the observer. The subject is blinded to both the ideational and emotional content of what is denied. This excludes ‘psychotic denial” in which the subject refuses to acknowledge a physical object or event within the subject’s field in the present time.

Neurotic denial serves to prevent the subject who uses it and anyone querying him from recognizing specific feelings, wishes, intentions, or actions for which the subject might be responsible. The denial avoids admitting or becoming aware of a psychic fact (idea and feeling) which the subject believes would bring him aversive consequences (such as shame, grief, or other painful affect). The evidence for this is clear whenever a subject breaks through his own denial and experiences shame or other emotion at what he learns about himself, often apologizing to the interviewer and so forth.

Disavowal Defense Level: Rationalization

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by devising reassuring or self-serving but incorrect explanations for his or her own or others’ behavior.

Rationalization involves the substitution of a plausible reason for a given action or impulse on the subject’s part, when a motive that is more self-serving or difficult to acknowledge is evident to the outsider. While the underlying covert motivation may be selfish, it may also involve caring or loving feelings which the subject finds uncomfortable. The subject is usually thought to be unaware or minimally aware of his true underlying motive; instead, he or she sees only the substituted, more socially acceptable reason for the action. The subject’s reasons commonly have nothing to do with any personal satisfaction, and thus disguise his or her real impulse or motive, although any related affect may still show.

Disavowal Defense Level: Projection

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by falsely attributing his or her own unacknowledged feelings, impulses, or thought to others. The subject disavows his or her own feelings, intentions, or experience by means of attributing them to others, usually by whom the subject feels threatened and to whom the subject feels some affinity.

Non-delusional projection allows the subject to deal with emotions and motives which make him feel too vulnerable (especially to shame or humiliation) to admit having himself. Instead he concerns himself with these same emotions and motives in others. The use of projection therefore commits the subject to a continual concern with those on whom he has projected his inner feelings as a way to minimize awareness of them himself.

Disavowal Defense Level: Autistic (or Schizoid) Fantasy

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by excessive daydreaming as a substitute for human relationships, more direct and effective action, or problem solving. Fantasy denotes the use of daydreaming as either a substitute for dealing with or solving external problems or as a way of expressing and satisfying one’s feelings and desires. While the subject may be aware of the ‘I’m just pretending’ quality of the fantasy, nonetheless, it may be the closest that he or she ever comes to expressing or gratifying the need for satisfying interpersonal relationships.

Fantasy allows the subject to obtain some temporary, vicarious gratification by daydreaming a solution to a real-world problem of conflict. The subject feels good while using fantasy and momentarily bypasses the conviction of powerlessness. In fact, during fantasy the opposite conviction (i.e., grandiosity) may be in operation, that one can do anything. Fantasy is maladaptive only when it short-circuits rather than rehearses attempts to deal with the real world by substituting dream world gratification. Sometimes, there may be a wholesale substitution of daydream activity in the place of real world attempts to meet needs and solve conflicts. This occurs without any loss of the ability to perceive and test external reality. The subject knows the difference between reality and fantasy life.

Major Image-Distorting Defense Level: Splitting

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by viewing himself or herself or others as all good or all bad, failing to integrate the positive and negative qualities of the self and others into cohesive images; often the same individual will be alternately idealized and devalued. Splitting of self-images often occurs alongside splitting of others’ images, since they both were learned in response to the unpredictability of one’s early significant others. In splitting of self-images, the subject demonstrates that he has contradictory views, expectations, and feelings about himself which he cannot reconcile into one coherent whole.

The self-images are divided into polar opposites: at a given time the subject’s awareness is limited to those aspects of the self-having the same emotional feeling tone. He sees himself in “black or white” terms. At one point in time the subject believes he himself has good attributes, such as being loving, powerful, worthy, or correct, and having good feelings, or he believes the opposite: that he is bad, hateful, angry, destructive, weak, powerless, worthless, or always wrong and has only negative feelings about himself. The subject cannot experience himself as a more realistic mixture of both positive and negative attributes.

In splitting of other’s images (object images), the subject demonstrates that his views, expectations, and feelings about others are contradictory and that he cannot reconcile these differences to form realistic and coherent views of others. Object images are divided into polar opposites, such that the subject can only see one emotional aspect or side of the object at a time. Objects are experienced in black or white terms. Splitting is revealed in two major ways. The subject may initially describe an object wholly in one way but later describe that same object in opposite ways. Second, each object is simply lumped with other objects into good and bad, positive and negative camps. When the subject uses splitting of object images, he cannot integrate anything that doesn’t match his immediate experience of and feeling about a given object. All the attributes with the same feeling tone are highlighted, and contradictory views, expectations, or feelings about the object arc excluded from emotional awareness, although not necessarily from cognitive awareness.

Splitting of object images and self-images is the subject’s defense against the anxiety of ruining the good images of people by allowing bad aspects of them to intrude upon the good. Splitting of self-images has one adaptive function: it minimizes the anxiety the subject would experience attempting to match his view of himself with how significant others will in fact see him and treat him. Instead, when seeing himself one way, the subject continues to see himself in the same valence no matter how others see him and treat him; contradictions then aren’t allowed into experience. This minimizes the disruptive, anxiety-provoking effects of trying to predict unpredictable people. The disadvantage is that the subject’s view of himself then becomes inflexible to the environmental realities, and the switch from good to bad views of himself is also unpredictable. This leaves the subject insensitive to more reasonable, predictable, and potentially more rewarding relationships outside of his original learning environment. In a better environment, the subject suffers from what was paradoxically so protective originally: an insensitivity to experiencing contradictory views of the self. Splitting of object images and self-images is the subject’s defense against the anxiety of ruining the good images of people by allowing bad aspects of them to intrude upon the good. Splitting of object images limits the anxiety the subject would feel in trying to discriminate how others will respond when he experiences or expresses his needs, feelings, etc. To see others as all good or all bad eliminates the anxiety-provoking task of trying to discern how others will behave toward the self, a task the subject believes to be impossible. Instead, the subject quickly categorizes people into good and bad camps based on subtle initial cues (e.g., ‘he frowned when I spoke, so he hates me”) or based largely on internal feeling states (e.g., “I feel so bad that I know you must hate me, so why should I open up to you?”). The defense is maladaptive, however, because the subject acts as unpredictably and irrationally toward others as he himself was treated; he forgoes the rewards he might attain if he were flexible in how he interacts with others. Using this defense, the subject wins some friends and makes some enemies, but not in a realistic way that considers the aggregate of others’ actual characteristics.

Major Image-Distorting Defense Level: Projective Identification

In projective identification the subject has an affect or impulse which he finds unacceptable and projects onto someone else, as if it was really that other person who originated the affect or impulse. However, the subject does not disavow what is projected – unlike in simple projection – but remains fully aware of the affects or impulses, and simply misattributes them as justifiable reactions to the other person! Hence, the subject eventually admits his affect or impulse, but believes it to be a reaction to those same feelings and impulses in others. The subject confuses the fact that it was he himself who originated the projected material. This defense is seen most clearly in a lengthy interchange in which the subject initially projects his feelings but later experiences his original feelings as reactions to the other. Paradoxically, the subject often arouses the very feelings in others he at first mistakenly believed to be there. It is then difficult to clarify who did what to whom first. This process is more extensive than simple projection, which involves the denial and subsequent external attribution of an impulse. Projective identification involves attribution of an image so that the whole object is seen and reacted to in a distorted light.

Projective identification is the defense of the traumatized person who felt irrationally responsible for his or her traumas. The defense is called into play when interpersonal cues stimulate memories of traumatic situations or interchanges or their residues. The individual experiences the other person as doing something to him or herself that is threatening, which make him or her feel powerless. The subject reacts to this imagined (or partially real) threat by attacking and believing that his or her own actions are justified, despite provoking the other. Guilt over having aggressive wishes toward the other person emerges and is handled by identification with the other, reinforced ‘by the belief that the alleged threat attack on oneself is deserved. Paradoxically the subject often induces the very feeling of powerlessness and guilt in others that he or she feels, which may result in others backing away.

Action Defense Level: Passive Aggression

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by indirectly and unassertively expressing aggression toward others. There is a facade of overt compliance masking covert resistance toward others. Passive aggression is characterized by venting hostile or resentful feelings in an indirect, veiled, and unassertive manner toward others. Passive aggression often occurs in response to demands for independent action or performance by the subject or when someone has disappointed the subject’s wish or sense of entitlement to be taken care of, regardless of whether the subject has made this wish known. This term includes ‘turning against the self.’

The person using passive-aggression has learned to expect punishment, frustration, or dismissal if he or she expresses needs or feelings directly to someone who has power or authority over him or her. The subject feels powerless and resentful. This expectation is most pronounced in hierarchical power relationships. Resentment is expressed by a passive stance: that the subject is entitled to the very things he doesn’t speak up for or that he is entitled to special dispensation. There is also some pleasure taken in the discomfort that the passive aggressive behavior causes others. Passive expression of anger through stubborn, inept, procrastinating, and forgetful behavior is quickly learned as a way to express: the conviction that the subject has the right to remain passive while expecting his needs to be met; to appear well-intentioned on the surface (overtly compliant), thus avoiding retaliation for the direct expression of affects, needs, or resentment; to express the resentment experienced toward those making demands by covert noncompliance that annoys others and obtain some satisfaction or vengeance, even if it means hurting oneself. In extremes, the resentment is not just expressed indirectly toward the other, but in fact, is turned 180 degrees around toward the self (turning against the self) to get at the other.

Action Defense Level: Help-Rejecting Complaining

Help-rejecting complaining (formerly called hypochondriasis, which term we do not us as it can be confused with the symptom disorder) involves the repetitious use of a complaint or series of complaint in which the subject ostensibly asks for help. However, covert feelings of hostility or resentment toward others are expressed simultaneously by the subject’s rejection of the suggestions, advice, or whatever others offer. The complaints may consist of either somatic concerns or life problems. Either type of complaint is followed by a ‘help-rejecting complainer’ response to whatever help is offered.

Help-rejecting complaining is a defense against the anger the subject experiences whenever he or she feels the need for emotional reliance on others. The anger rises from the conviction, or often the experience that nobody will really satisfy the subject’s perceived needs. The subject expresses the anger as an indirect reproach by rejecting help as “not good enough” while continuing to ask for more of it. Instead of driving the other person away by the expression of anger, the use of help-rejecting complaining binds the person to the subject by the overt request for help. The subject’s expression of helplessness over the problem at hand reflects a sense of powerlessness to get the right help, comfort, and attention, while discharging resentment for the expected disappointment that enough help will not be forthcoming.

Action Defense Level: Acting Out

The individual deals with emotional conflicts, or internal or external stressors, by acting without reflection or apparent regard for negative consequences. Acting out involves the expression of feelings, wishes or impulses in uncontrolled behavior with apparent disregard for personal or social consequences. It usually occurs in response to interpersonal events with significant people in the subject’s life, such as parents, authority figures, friends, or lovers. This definition is broader than the original concept of acting out transference feelings or wishes during psychotherapy. It includes behavior arising both within and outside of the transference relationship. It is not synonymous with “bad behavior,” or with any symptom per se , although acting out often involves socially disruptive or self-destructive behavior. So-called acting out behaviors, such as physical fighting, or compulsive drug use, must show some relationship to affects or impulses that the person cannot tolerate to serve as evidence for the defense of acting out.

Acting out allows the subject to discharge or express feelings and impulses rather than tolerate them and reflect on the painful events that stimulate them. The following elements are present. First, the subject has feelings or urges which he is inhibited from expressing. Experiencing the original impulse quickly results in a rise in tension and anxiety. Second, the individual bypasses awareness and ceases any attempt to delay, reflect upon, or plan a strategy to handle the impulse or feeling. Rather it is directly expressed in behavior without prior thought. This results in the expression of rather raw aggression, sex, attachment, or other impulses without taking the consequences into account. Following acting out, reflection may return, and the subject commonly feels guilty or expects some punishment, unless a further defense comes into play, such as denial or rationalization (“I was so angry, I had to do it. It was his fault for stirring me up.”). Acting out is maladaptive because it does not mitigate the effects of the internal conflict, and it often brings upon the subject serious, negative, external consequences.

Coding Procedure

The DMRS-Q is a computer-based measure that can be used for clinical, research and teaching purposes by registering on the DMRS-Q platform (see text footnote 1 for registration and login). The software use is free of charge and provides the user with several functions, such as starting a new coding, revising previous ratings, downloading outputs and scoring sheets. At present the DMRS-Q is available in English and in Italian, although other languages may be added on the platform after appropriate validation.

Like most Q-sort tools, the DMRS-Q coding procedure follows the rules of ranking items into a force distribution ( Block, 1978 ; Brown, 1993 , 1995 ). The 150 items must be ordered into seven ordinal ranks, corresponding to increasing level of descriptiveness, intensity or frequency. Higher ranks are less populated and include items that best describe the most characteristic defensive patterns activated by an individual. Conversely, lower ranks are more populated and include items that either do not apply or are only somewhat descriptive of the individual’s defensive profile. In ascending order of descriptiveness, DMRS-Q ranks are as follows: rank 1 (60 items) = not used at all; rank 2 (30 items) = very rarely used; rank 3 (20 items) = slightly or rarely used; rank 4 (16 items) = medium or sometimes used; rank 5 (10 items) = intensive or often used; rank 6 (8 items) = very intensive or frequently used; rank 7 (6 items) = almost always used. When all items are correctly ordered into the DMRS-Q forced distribution, as displayed in Figure 2 , the rating is complete and ready to be sent for scoring output. For detailed directions of the DMRS-Q rating procedure a video-tutorial is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PP1ykSrGLkY&t=87s .

Figure 2. The DMRS-Q forced distribution (image extracted from the DMRS-Q web-app).

Clinical Data and Training

Data required for a stable DMRS-Q rating might vary with the aim of its use. Coders must have sufficient information of the evaluated subject’s defensive functioning, directly observed or obtained from records. Since recorded and transcribed data are not essential, the DMRS-Q can be applied in multiple contexts. The required time for a DMRS-Q coding decreases depending on rater’s experience, ranging from about 60 min in the very first ratings to less than 15 min for expert coders. A 6-h training is highly suggested for reaching high reliability on all DMRS-Q quantitative scores, although a recent study demonstrated that untrained raters obtain acceptable to excellent reliability on most DMRS-Q scales (ICC ranging from 0.60 to 0.91) ( Békés et al., 2021 ). In any case, for the correct use of the DMRS-Q it is essential to read the present manual for understanding the theoretical and methodological background behind the measure.

Scoring System

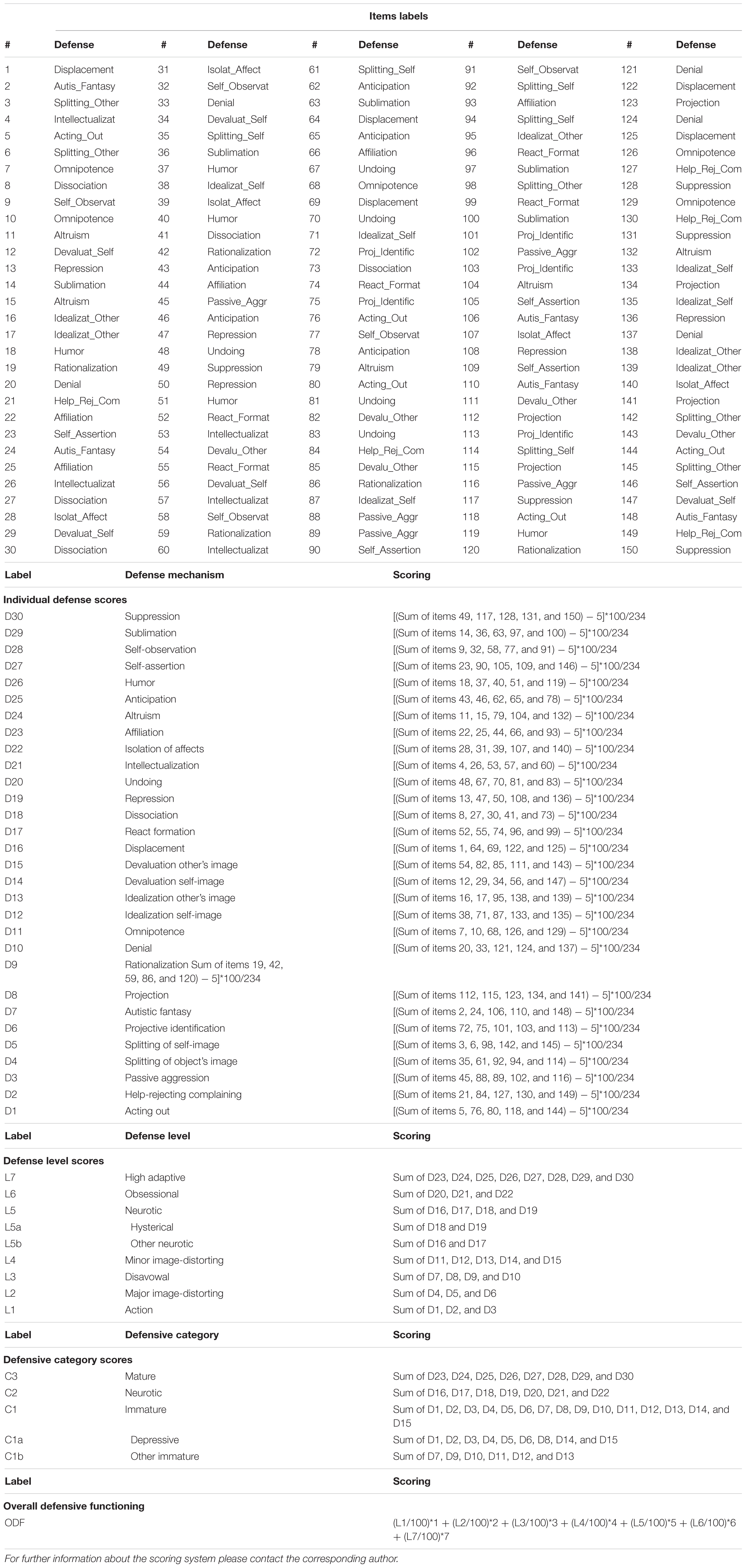

The DMRS-Q scoring procedure is made with a software that extracts DPN and quantitative scores from the completed DMRS-Q rating. Formulas for quantitative scoring are displayed in Table 9 .

Table 9. DMRS-Q quantitative scoring system.

Although the scoring software has not yet been uploaded in the DMRS-Q web-app in order to protect it from hackers, we will include it after the publication of the present article. This upgrade will allow the DMRS-Q web-app to automatically calculate qualitative and quantitative scores after each evaluation and immediately deliver the DMRS-Q report to the user.

The Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-Sort Report

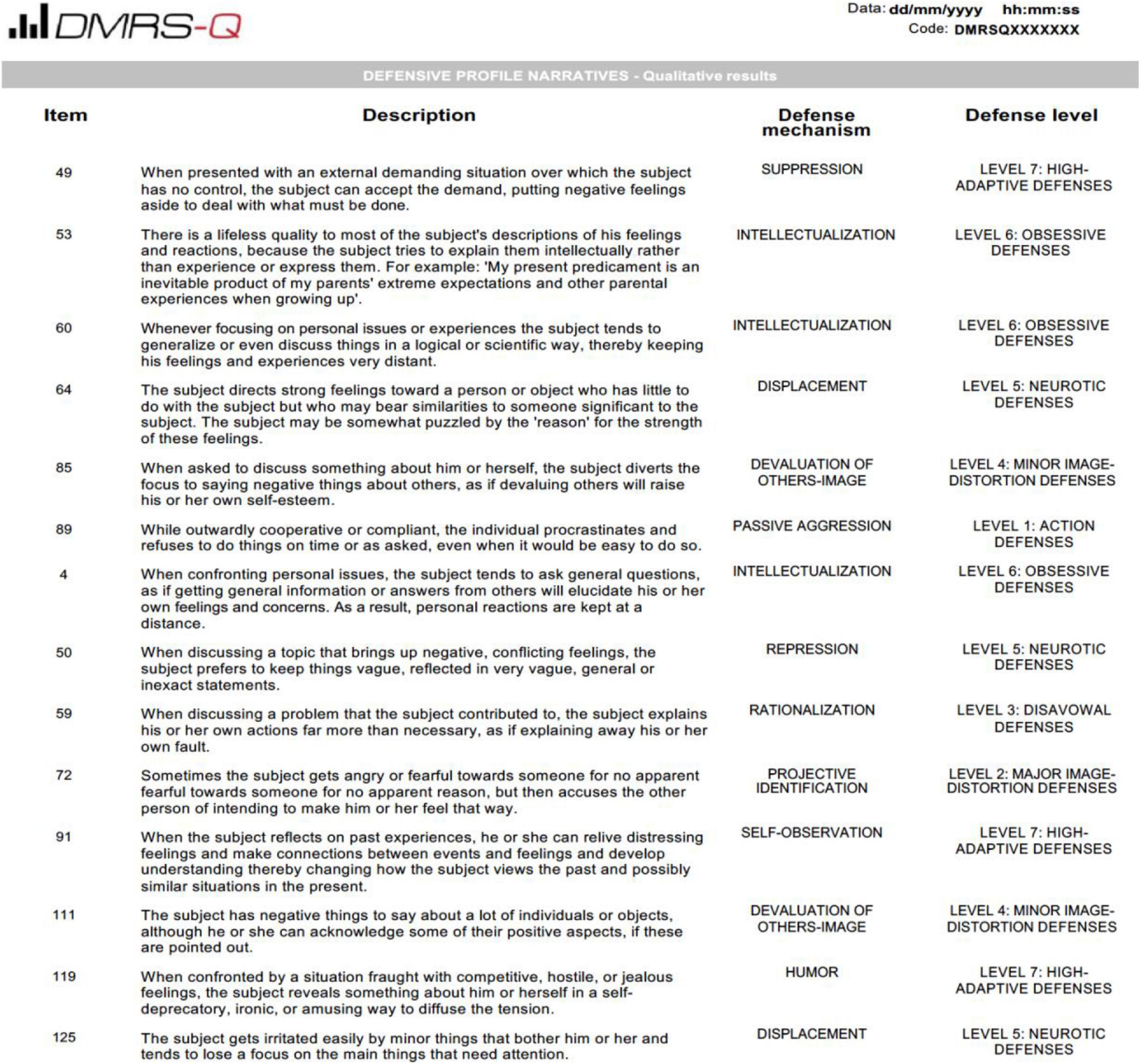

Like the original DMRS, the DMRS-Q provides qualitative and quantitative scores reflecting the individual’s defensive functioning. Qualitative scores are displayed as the Defensive Profile Narratives (DPN), a case description of the most characteristic ways the subject handles internal conflict and external stressors. The DPN comprises all items sorted in ranks 6 and 7 ( N = 14) and coded as highly descriptive of the subject’s defensive profile. The DMRS-Q software automatically lists these items and indicates the defense level and individual defense mechanism associated with each item. Figure 3 shows an example of a DPN displayed in the DMRS-Q report.

Figure 3. Defensive Profile Narrative (PDN) of a patient assessed with the DMRS.

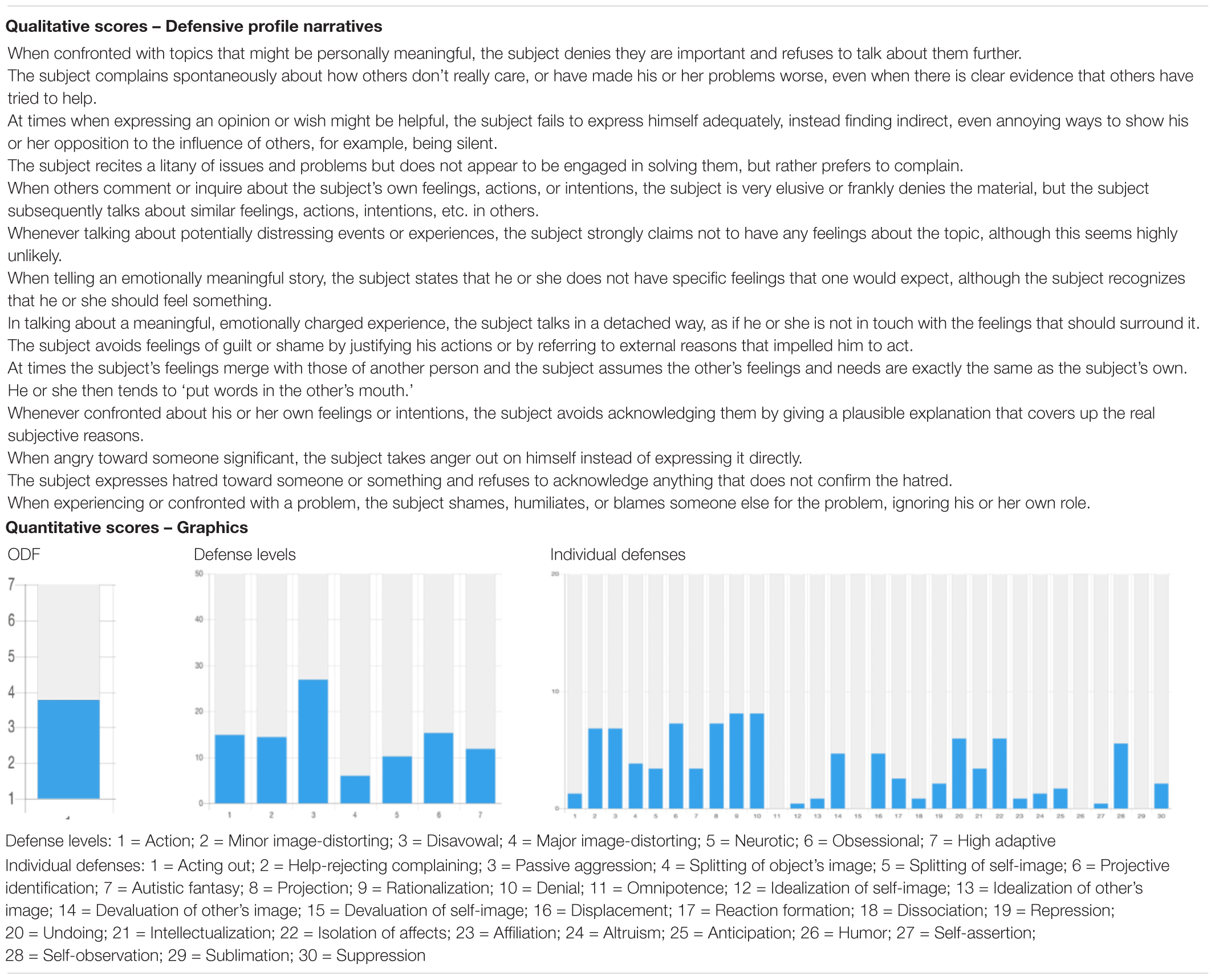

In addition to DPN, the DMRS-Q report provides the following quantitative scores: a summary Overall Defensive Functioning (ODF), ranging from 1 to 7; proportional scores for seven defense levels (see Table 1 for review); and proportional scores for 30 individual defense mechanisms (see Tables 2 – 8 for review). Future updates in the web-app software will also add scores for defensive categories and subcategories. Quantitative scores are displayed in both numerical and graphical forms in the DMRS-Q report, which can be downloaded from the user dashboard at any time.

Clinical Vignette and Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-Sort Rating

One example of how to use the DMRS-Q in clinical setting is offered by the following vignette. A brief description of patient-therapist interactions during the session is used for the DMRS-Q rating with no additional information about patient’s demographics, diagnosis, length of treatment, nor therapist’s approach, experience, etc. A summary of qualitative and quantitative evaluation of patient’s defense mechanisms analyzed with the DMRS-Q is displayed in Table 10 . The 14 items coded as the best descriptive of the patient’s defensive functioning in the session were included in the qualitative defensive profile (DPN), while all item scores contributed to the quantitative scores displayed in the graphics.

Table 10. Qualitative and quantitative DMRS-Q evaluation of the described in the clinical vignette.

The session started with the patient telling his negative experience with his lawyer and his attempt to solve a financial issue. While reporting on how the therapy had been helping him in enhancing his engagement in professional problems, the patient described himself with very devaluing terms. Even when the therapist tried to support him, saying that he was not aware of that difficulty, the patient made sarcastic comments toward the therapist and switched to another topic: the relationship with his girlfriend. The patient complained a lot about how frustrating this relationship was and justified his anger as the result of feeling too much pressure and low empathy at the same time. He made lots of devaluing comments about his girlfriend, although he could still see some positive aspects of her. Moreover, he reported on a series of passive aggressive behaviors toward a number of people (e.g., delay in return phone calls, calling up his ex-girlfriend, feeling bored in the session, feeling the therapist detached from him). Most of the session was characterized by the patient complaining about several aspects of his life, including the therapy, in which he had experienced ambivalence, detachment and frustration. When the therapist tried to interpret these feelings as defensive responses to the experience of a temporary unavailability of significant people, the patient denied the interpretation and perceived the therapist as manipulative. Despite therapist’s interpretations of his opposition, silence and emotional distancing as reactions to feeling frustrated by not getting what he wants when he wants, the patient rejected them and became even more oppositional. Toward the end of the session, after many therapist’s attempts of interpreting patient’s maladaptive pattern, the patient could finally reflect upon it and became more collaborative. However, his reflections were influenced by generalization, detachment and ambivalence. The patient described himself as stuck in silence, his inability to talk about his feelings, to see things in a different way. At this point the patient was able to let the therapist help him and get involved in a shared exploration of his fears, needs and desires. He reflected on his difficulty in listening to his girlfriend’s trouble but somehow justified it as a need of physical connection. However, when the therapist made further interpretations of the patient’s fantasy of emotional fusion, the patient seemed to reactivate the projective pattern, which was promptly interrupted by the therapist. This allowed the patient to keep reflecting in an ambiguous manner instead of complaining and activating all sorts of immature defense mechanisms.

Table 10 displays PND and graphics of patient’s defensive functioning, including ODF, defense levels, and individual defenses scores. Defensive maturity fell in the range of severe depression or personality disorders (ODF < 4; Presniak et al., 2010 ; Perry and Bond, 2012 ; Di Giuseppe et al., 2019 ), with about 70% of immature defenses in use during the session, in particular those belonging to disavowal defense level. Looking at the use of individual defense mechanisms, the legend shows that patient’s predominant defenses were help-rejecting complaining, passive aggression, projecting identification, projection, rationalization, and denial. This defensive constellation indicates a depressive, resistant and passive aggressive patient inclined to withdraw inside himself and view his problems as externally caused, instead of dealing with his internal conflicts and external stressful situations.

The utility of studying defenses with the DMRS approach is that it reveals the psychological function behind the use of defense mechanisms, the unconscious motives for protecting oneself from intolerable emotional experiences. It could be the need of withdrawing anger, the threat of self-esteem failures, the shame of guilt experienced in confronting with unacceptable thoughts and many others. Any of these functions suggests what internal conflicts the individual is experiencing and how adaptive is his or her defensive functioning. In the present article we described the theoretical and methodological background of the DMRS-Q, illustrated its computerized and free-of-charge online use, provided directions for coding and described the interpretation of results.

While the assessment of defense mechanisms has been a controversial issue debated among scholars for more than a century, in recent years research, including that with the DMRS ( Perry, 1990 ) convinced the American Psychiatric Association to include in the DSM-IV a provisional axis for the assessment of the hierarchy of defense mechanisms ( American Psychiatric Association, 1994 ). However, the excellence of this highly valid and reliable method is unfortunately accompanied by its time-consuming training and coding costs, which led to the elimination of the defense axis in the DSM-5 because of lack of empirical findings supporting the theory ( Vaillant, 1992 ).

With the development of the Q-sort version of the DMRS we provided a computerized and easy-to-use clinician-report measure for the assessment of the whole hierarchy of defense mechanisms observable in the routine practice of both dynamic and non-dynamic practitioners, as other have found ( Starrs and Perry, 2018 ).