- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Water Crisis in South Africa: Causes, Effects, And Solutions

Both the failing water infrastructure and the ever-increasing population have exacerbated the water crisis in South Africa, forcing its residents to adopt strict habits. Official mandates regarding significant reductions in water usage have led to overcrowded communal water taps, dangerous bore-holing, and the desperate acceptance of contaminated groundwater sources, all to combat a drought that has plagued the South African locale for over seven years. While local crisis response groups are available to support residents, there is only so much that can be done to solve the water crisis in South Africa when there are simply no sources of clean, freshwater available.

South Africa is a country known for many things: its resilient beauty, its diverse cultures, and more recently, its social and economic growth. According to the World Bank , the Republic of South Africa (RSA), a newly industrialised nation, boasts the 33rd largest economy, and the 23rd largest population on the planet.

The RSA is also the most populated nation south of the equator, home to over 59 million people. This number is only expected to increase as citizens from poorer countries in the vicinity migrate to look for new homes, work and other opportunities.

Unfortunately, South Africa’s consistent population increases are spelling trouble for a vastly underprepared water infrastructure. This, combined with low rainfall in recent years, has caused a severe and trying water crisis, the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the Cape Town water shortage that affected the life of residents in 2018.

You might also like: One Woman’s Mission to Fight Water Scarcity in Africa

What Led to A Water Crisis in South Africa?

As experts in the field have agreed , the water crisis in South Africa can likely be attributed to economic (a lack of investment), as well as physical (a lack of rain) water scarcity.

In an article , spokesman for the government committee appointed to respond to the water crisis in South Africa Luvuyo Bangazi described how dire the situation in South Africa has become.

“We haven’t had good rains for more than seven years and we’ve had a sharp increase in water consumption from across sectors, be it residential, business, or other. So, compounding that with obviously ailing infrastructure that leads to severe water leaks … almost 25-30% of our water [is] being lost due to water leaks caused by failing infrastructure.”

It is estimated that 70 million litres of treated, clean, drinkable water is lost daily as a result of the thousands upon thousands of leaks that characterise South Africa’s water piping system. Thankfully, a recently formed local group known as the Water Crisis Committee has pushed the RSA administration to respond to the damage; since June 2022, an emergency response team has managed to fix over 9,700 leaks.

The water leaks are of course serious, but the consistent lack of rain, year after year, has officials far more concerned. South Africa is already a normally arid locale, with an average yearly rainfall almost half the global average and ranked 29th driest out of 193 nations.

Since 2015 , South Africa has experienced record-low levels of precipitation, likely the result of anthropogenic climate change. A study completed by researchers at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, International Food Policy Research Institute, and CGIAR found that there was a chance greater than 50% that South Africa’s mid-century temperatures would experience a threefold increase over the current climate’s variability range, meaning whatever temperature changes South Africa experiences will likely be three times higher than normal. What’s more, the risk of decreased precipitation in the country is three to four times higher than the risk of increased precipitation.

The Sacrifice of Local Residents

The Cape Town water crisis that occurred four years ago nearly left the South African economic hub completely without water. To quell water usage, car washes, swimming pools, and fountains were all banned, residents were told to consume no more than 50 litres per household, and new strict agricultural water quota limits were put in place. The city had become so hopelessly desperate that officials were encouraging residents to shower for no more than two minutes, to recycle and reuse greywater, and to flush their toilets only when absolutely necessary.

Today, the residents of the Nelson Mandela Bay, otherwise known as Port Elizabeth, are suffering the greatest shortages. The Kouga, Churchill, Impofu, Loerie, and Groendal Dams–-the dams that supply the Nelson Mandela Bay locale–are a mere 16% full on average . This has left their sizeable population of 1.28 million people worried for the future, forced to take precautions and watch their water usage very carefully.

“There needs to be a very conscious reduction in water demand,” said Sputnik Ratau, media liaison for the South African Ministry of Water and Environmental Affairs. “We should be able to get through this period”.

According to the Safe Drinking Water Foundation , the average human, at minimum, requires 235 litres of sanitary water every day. The residents of Nelson Mandela Bay, much like those of Cape Town four years prior, are currently being asked to consume a maximum of 50 litres of water per day.

“Nelson Mandela Bay currently faces an unprecedented crisis in the delivery of basic water supply,” said members of a local community-based committee in a statement .

You might also like: Water Shortage: Causes and Effects

Overcoming the Water Crisis in South Africa: The Problem with the “Solution”

To prepare for a possible “day zero” (the day municipal taps are shut off), Gift of the Givers , a non-governmental South African disaster relief organisation, has been drilling boreholes near public locations like hospitals and schools to access water deposits deep beneath the South African landscape. The boreholes have been a true lifesaver for the locals who use them. However, some experts worry that they may cause more trouble than it’s worth.

“What is not being revealed [to citizens] is that because of the geological nature of the coastal zone, [fresh]water being extracted may be replaced by saline water intrusion coming from the sea via certain fissures in the rocks.” said Phumelele Gama, head of the botany department at Nelson Mandela University in an interview with Mongabay. According to Gama, the saline water intrusions would eventually render the borehole water deposits completely undrinkable in as little as six months after “day zero”.

Furthermore, the water deposits being accessed by these boreholes often contain an unhealthy and possibly deadly amount of bacteria. A 2020 study out of South Africa’s University of Venda and the Tshwane University of Technology, for example, found that 33% of the water found in borehole deposits near Vhembe rural areas in South Africa’s Limpopo province was contaminated with E. coli bacteria. Another study completed in South Africa came to similar conclusions, discovering that the boreholes near 10 public schools in the Giyani region of Limpopo contained multiple bacterial strains, including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacteria and E. coli.

Building a Better Tomorrow

Though the climate forecast of Nelson Mandela Bay, as well as all of South Africa as a whole, continues to look grim, there are many who relentlessly strive for a better tomorrow. A multidisciplinary academic team from universities in the Western Cape province came together after the Cape Town water crisis to better understand water scarcity, and how best to respond to it in the future. The collaboration, known as “Cities facing escalating water shortages,” workshopped with 50 stakeholders, assessing political, economic, technical science, natural science, social science, and civil society facets. As described in an article published in Brookings , the team formulated five key lessons:

- Build water-sensitive and resilient cities

- Practice integrated water planning and management that ensure sustainable and equitable water access.

- Build water-smart cities that are connected with real-time relevant data and information that is shared widely.

- Ensure a collaborative and supportive governance environment to unlock synergies.

- Cultivate informed and engaged water citizens, and empower residents, government, businesses, NGOs, and the agricultural sector to make a difference.

If you are looking to help with the water crisis in South Africa yourself, The Water Project, a top-rated non-profit organisation, provides an easy-to-use platform for sending donations on their website , as does Greenpeace , and World Vision . The Water Institute of South Africa is also asking for support, internationally and within. Local citizens are encouraged to donate empty water bottles, to provide their time at water points, or to act as deliverers.

Featured Image by Jeff Ackley on Unsplash

This article was originally published on October 5, 2022

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

About the Author

Dylan Stoll

The World’s Top 10 Biggest Rainforests

10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

How Does Deforestation Affect the Environment?

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

Water Scarcity In South Africa: A Result Of Physical Or Economic Factors?

Introduction

“Water scarcity” refers to the volumetric abundance, or non-abundance, of water supply. It is expressed as the ratio of human water consumption to available water supply in a given area. It is a physical reality that can be measured consistently across regions and over time. [1] Water scarcity is driven by two factors (i) physical (physical or absolute water scarcity) or economic (economic water scarcity).

South Africa is considered a water-scarce country. [2] ; [3] ; [4] This is based principally on physical descriptors like climatic conditions and escalating water demands. This brief investigates whether observed water scarcity in South Africa can be attributed to physical or economic factors, or both.

Physical Water Scarcity

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization ( FAO ), [5] physical water scarcity occurs when there is not enough water to meet all demands, or inadequate natural water resources to supply a region's demand. According toFalkenmark [6] , there are four drivers of physical water scarcity: (i) demand-driven water scarcity, (ii) population-driven water scarcity, (iii) climate-driven water scarcity and (iv) pollution-driven water scarcity.

Demand-driven water scarcity occurs when water demand is higher than the capacity of available water sources. In cases where demand is population-driven, high population levels place pressure on the amount of water physically available, leading to per capita water shortages. This is termed population-driven water scarcity . According to UN Water, physical water scarcity is exacerbated by rapidly growing urban areas which place heavy pressure on adjacent water resources. [7]

According to the FAO (2007), areas more susceptible to severe physical water scarcity are those located where high population densities converge with low availability of freshwater. Typical examples in South Africa are the Gauteng and Western Cape provinces. Estimates suggest that Gauteng will receive a net immigration of 1.02 million people between 2016 and 2021. [8] According to Stats SA (2018), the Province remains the leading centre for both international (cross-border) migrants and domestic migrants (from rural areas of Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal, and Eastern Cape).

The Western Cape is the second major immigration attraction centre in South Africa (Ibid). For example, between 1995 and 2018, Cape Town’s population grew by 79% — a growth not matched by sufficient increase in dam storage capacity (up by only about +15 percent over the same period). Population growth resulted in increased water demand at the residential level. [9]

Localised population growth coupled with profligate water use exert pressure on available resources, resulting in gross imbalances between water demand and supply. For instance, it is estimated that South Africans consume about 237 litres of water per person per day. This is well above the world average of 173 litres per day. [10]

Climate-driven water scarcity occurs when insufficient precipitation and high evaporation create low available stream run-off. This leads to limited water availability. Climate-driven water scarcity is exacerbated by global climate change, climate variability and recurrent droughts. South Africa, as has been noted is recognised as a water-scarce country. The country’s mean annual precipitation is 450 mm. This is well below the world average of 860 mm per year [11] . In terms of a commonly used definition, namely that of the average “Total Actual Renewable Water Resources” ( TARWR ) per person per year, South Africa is already ranked the 29 th driest country out of 193. [12] According to the Department of Communication and Information System, South Africa is the 30 th driest country in the world. [13]

In addition, South African precipitation concentration has been observed to exhibit variability in space and time (spatio-temporal variability). Spatial variability : South Africa experiences precipitation that varies significantly between its western and eastern regions. Annual precipitation in the north-western region often remains below 200 mm, whereas much of the eastern Highveld receives between 500 mm and 900 mm (occasionally exceeding 2000 mm) per annum (Botai et al ., 2016).

Temporal variability. According to Schulze (2007), the average amount of precipitation need not necessarily be a constraint for successful water resources operations. In fact, one can get by with, and adapt one’s practices and operating rules to, a low precipitation if one has the assurance that the rains will fall when needed or as expected. [14] While the amount of precipitation received may be an issue of concern, the temporal precipitation variability seems to be a critical dimension in South Africa’s water scarcity. In addition, droughts are recurrent and climate is unpredictable. On an annual timescale, South African precipitation concentration has been observed to be highly irregular in most parts of the country.

Pollution-driven water scarcity : water quality can degrade to the point that it is unusable. In this case the water may be available but remain unsuitable for beneficial uses resulting in water scarcity. Water scarcity is thus not merely a volumetric (quantity) issue but equally a quality issue. Consequently, the Rand Water [15] recognised that in South Africa the scarcity of freshwater is exacerbated by major increase in pollutant fluxes into river systems arising from river catchments. These are caused by urbanisation, deforestation, destruction of wetlands, industry, mining, agriculture, energy use, and accidental water pollution. These factors lead to the major reduction of available water resources.

Economic Water Scarcity

Economic water scarcity or social water scarcity (second-order water scarcity) is caused by a lack of investment in water or a lack of human capacity to satisfy the demand for water, even in places where water is abundant. It is induced by political power, policies, and/or socioeconomic relations. Symptoms include inadequate infrastructure development.

In 2006, the United Nations Development Programme ( UNDP ) human development report concluded that water scarcity is not solely rooted in the physical availability of water, but in unbalanced power relations, poverty, and inequality. [16] As a result, the FAO [17] emphatically posits water scarcity as an issue of poverty, where unclean water and lack of sanitation have been observed to be the destiny of poor people world-wide.

The observed water scarcity in South Africa is not exclusively attributable to physical drivers. It also has economic causes. Economic water scarcity is caused by a lack of investment in infrastructure or technology to draw water from rivers, aquifers or other water sources. In addition, insufficient human capacity to satisfy the demand for water may exacerbate scarcity (Schulte, 2014).

Geospatial aspects of economic water scarcity

South Africa’s history of apartheid geospatial planning has resulted in many rural areas not having access to basic water supply and sanitation services (Masindi & Duncker, 2016). [18] In eradicating the historical geospatial inequalities and socio-economic disparities numerous programs have been initiated since 1994.

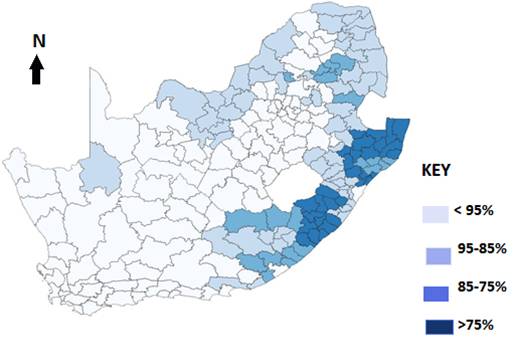

Despite these programs, overt inequalities in water infrastructure delivery still exist between rural and urban areas. Predominately rural provinces and small towns are characterised by relatively high water-infrastructure backlog and low water service reliability. For instance, Stats South Africa (2016), observed that the municipalities with the largest percentage backlog are generally located in the largely rural areas along the Eastern seaboard in Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, and to a lesser extent in Limpopo ( See infrastructure backlog map in the appendix ). The highest backlogs are observed in Ngquza Hill (81,7%), Port St Johns (81,3%) and Mbizana (77,8%). By contrast, municipalities such as Cape Town (0,2%), Drakenstein and Saldanha Bay (both 0,5%), and Witzenberg, and Sol Plaatjie (both 0,7%) barely registered any backlog.

In 2019, the investment disparities have not changed as predominantly rural provinces still lag behind.

This subjects rural households disproportionately to economic water scarcity. Similarly, the Parliamentary Monitoring Group, [19] points out there are gross inequalities in relation to access to safe water and sanitation. Individuals at a disadvantage are largely those in the rural areas, meaning, in demographic terms, poor, African residents of Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo.

It is apparent that observed water scarcity in South Africa is to a large extent attributable to physical causes. These are exacerbated by the impact of global climate change, climate variability and increasing demand on available water resources.

However, the root causes are not exclusively limited to physical conditions. The observed water scarcity in some parts of the country can be explained by uneven investment in water infrastructure, where geospatial disparities are obvious. Rural communities, small towns and rural provinces remain inadequately serviced. This subjects rural communities to the effects of both observed national physical water scarcity and localised economic water scarcity.

Nhlanhla Mnisi Researcher [email protected]

Appendix: Infrastructure backlog map

Water infrastructure backlog data sourced from: Water Services Knowledge System (URL: www.dwa.gov.za/wsks )

[1] Schulte, 2014. URL: https://pacinst.org/water-definitions/

[2] Muller et al . (2009), URL: https://www.dbsa.org/EN/About-Us/Publications/Documents/DPD%20No12.%20Water%20security%20in%20South%20Africa.pdf

[3] URL: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/water.pdf

[4] URL: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/03/world-water-day-water-crisis-explained/

[5] http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/en/c/218939/

[6] Falkenmark (2007), URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42765865_On_the_Verge_of_a_New_Water_Scarcity_A_Call_for_Good_Governance_and_Human_Ingenuity

[7] https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/

[8] Stas SA (2018), URL: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=11331

[9] Environmental and energy study institute. URL: https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/cape-towns-water-crisis-how-did-it-happen

[10] South African Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation (2019), URL: http://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/speeches/budapest.pdf

[11] Botai et al . (2017).

[12] Muller et al . (2009), URL: https://www.dbsa.org/EN/About-Us/Publications/Documents/DPD%20No12.%20Water%20security%20in%20South%20Africa.pdf

[13] Department of Communication and Information System (2020), URL: https://www.gov.za/about-government/government-programmes/national-water-security-2015

[14] Schulze (2007), URL: http://sarva2.dirisa.org/resources/documents/beeh/Section%2006.3%20CV%20of%20Precip.pdf

[15] Rand Water (2017). URL: http://www.randwater.co.za/corporateresponsibility/wwe/pages/waterpollution.as px

[16] UNDP (2006), URL: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/2006%20Global%20HDR/HDR-2006-Beyond%20scarcity-Power-poverty-and-the-global-water-crisis.pdf

[17] FAO, URL: http://fao.org/3/a-aq444e.pdf

[18] Masindi & Duncker (2016), URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311451788_State_of_Water_and_Sanitation_in_South_Africa

[19] Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2017), URL: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/23868/)

Publications

Quick links.

South Africa has had lots of rain and most dams are full, but water crisis threat persists

Associate Professor and Research Specialist in Integrated Water Resource Management, University of South Africa

Disclosure statement

Anja du Plessis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of South Africa provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Most parts of South Africa, specifically its summer rainfall areas, have received above average rainfall since October 2021. This has led to an increase in the country’s national average water levels.

The total percentage of water stored in reservoirs nationally rose from 84.6% in mid-December 2021 to 88.7% at the end of the year . By mid March in 2022, the national average was 94% compared to 85% for the same period last year, with all provinces showing an overall increase .

The normal national water storage percentage for South Africa is typically between 85% and 80%. The drought from 2015 to 2018 depleted the country’s water storage levels, especially during the first half of 2016 when overall water storage fell below 50% .

South Africa is classified as being “water short” and moving towards “water stressed” in global terms. The country’s average annual rainfall is 450mm compared to the global average of 860mm . Highly variable rainfall has always led to skewed spatial distribution of water resources .

The skewed spatial distribution is clear when looking at runoff, which is water that drains from the surface of an area into river systems. Only 8% of the country’s land area generates 50% of the volume of water in its river systems – which in turn account for most of the country’s water.

The national storage capacity of major reservoirs in South Africa is currently 33,900 million cubic metres, created by 252 large dams . The country has long passed the stage where water requirements can be met from natural availability alone. Storage of water is essential for securing water supply. It’s also necessary because of the high variability in river flow within and between years.

Despite the recent rains, some areas have still not recovered from continued effects of the drought which has been ongoing since 2015. It’s been described as one of the worst droughts experienced by South Africa in recent times .

Read more: Why full dams don't mean water security: a look at South Africa

Communities, especially in the Eastern Cape province, are still facing water shortages or erratic water supply even though some major dams in other parts of the country are full. For example, the major water system of the Eastern Cape province, the Algoa Water Supply System, containing five dams supplying water to the Nelson Mandela Bay metropolitan area, hasn’t recovered. Its water levels are still at only 17.9% .

This shows that even though South Africa has received above average rainfall over most of its summer rainfall areas since October 2021, the country’s water resources are still under continued pressure. The primary drivers of this based on the findings of numerous reports and research , include unsustainably high water use and demand, persistent pollution from various sources, misappropriation of funds, collapsing or non-functional municipal sewage systems and a lack of skilled personnel.

The challenges

Climate scientists predict that increased climate variability will expose South Africa to more frequent and prolonged droughts . Population growth, rural-urban migration, industrialisation, and water pollution all place additional stress on scarce water resources.

Energy challenges also have a profound negative effect on water supply. Almost every step of the water cycle – producing, moving, treating and heating water, as well as collecting and treating wastewater – requires and consumes energy . South Africa’s energy challenges therefore also affect water provision, because power cuts interrupt water supply and negatively affect this water-energy nexus .

Poor water usage behaviour, especially by domestic water users, is a persistent issue. South Africans’ average domestic water use is an estimated 237 litres per capita per day. This is 64 litres higher than the international benchmark of 173 litres . This high use is partly attributed to high municipal non-revenue water. Approximately 41% of water that’s pumped or produced in South Africa is “lost” in a variety of ways before it reaches the water user or customer. This far exceeds the global best practice figure of 15% .

Non-revenue water includes physical losses due to leakage, which is often a result of poor operation and maintenance. It also includes commercial losses caused by meter manipulation or other forms of water theft as well as unbilled authorised consumption. These water losses vary across municipalities and service providers but an estimated average of 35% of physical losses occur in municipal systems .

Continued lack of proper investment in the maintenance of existing infrastructure has led to dilapidated water infrastructure. It’s the main reason for increasing levels of non-revenue water.

Water degradation

Water degradation is also a major issue in South Africa. It contributes to increased water scarcity by causing water resources to be of an unacceptable quality for various uses.

The main pollution challenges include large volumes of wastewater discharged from dysfunctional wastewater treatment works. These introduce excessive nutrients, phosphates and coliforms (bacteria or pathogens) into rivers .

The discharge of mining waste also introduces heavy metals into water sources and agricultural practices – which use pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers – introduce salts, chemicals and other toxic substances into receiving water sources through runoff .

Non-functional municipal sewage systems have created a sewage pollution crisis of varying degrees across the country. More than 90% of the total 824 treatment plants release raw or partially treated sewage into water resources. In 2015, it was estimated that 80% of South Africa’s freshwater resources were so badly polluted that no purification processes in the country could make it fit for consumption .

Sewage pollution isn’t a new issue. It has been ongoing and worsening due to the continuous decline of South Africa’s infrastructure, misappropriation of funds and a lack of skilled personnel to manage water bodies which now requires major intervention .

Going forward

Persistently high demand for water is driven by poor water usage behaviour, physical and commercial water losses and ecological degradation. All this together with water pollution adds to the country’s water constraints.

South Africa might have sufficient supply to meet current demand, but current government estimates show that demand will outstrip supply by 2025 . Current predictions show that the country will experience a water deficit of 17% by 2030 . Some research suggests that demand exceeded available yield as far back as 2017. This means the country is already experiencing water stress due to total water consumption already exceeding the amount of total water available. This implies that various water sectors are using more water than what’s available. This unsustainable water consumption is creating a water deficit.

Both the government and the population need to be more knowledgeable about the state of the country’s water availability and quality. The government must improve the overall management of water resources and address the deteriorating infrastructure, poor water and sanitation service delivery and water pollution.

The culture of unsustainable water use and poor management of water resources needs to change. Despite numerous dams overflowing, South Africa needs to take action to avoid a major water crisis in the near future.

- Infrastructure

- Water pollution

- South Africa

- Water treatment

- Peacebuilding

- Water resources

- Heavy rainfall

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Project Manager – Contraceptive Development

Editorial Internship

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Day Zero: Where next?

Cape Town may have dodged the Day Zero bullet, but all across South Africa drought and rising demand is escalating a national water crisis.

As pellets of rain pounded the dry earth of Eastern Cape this January, a man launched himself into a puddle of water created by a broken drain. This spontaneous celebration seems symbolic of South Africa’s precarious but hopeful relationship with water: the country is desperately dry, making any precipitation extremely precious, but there are a few long-term solutions to help ease this ongoing water problem. In 2018, Cape Town’s ‘Day Zero’ became the focus for South Africa’s water crisis, but while its circumstances were certainly unique, the causes of its water problems were not—high demand and inadequate supply. As such, Cape Town’s situation is a warning for the whole country. South Africa relies on its rainwater, levels of which are unpredictable, unevenly distributed, and decreasing as a result of global warming. In October 2019, dams were at 10 to 60 percent below 2018’s levels. As of January 2020, some rain has fallen and some reservoirs are filling again, but the forecast is for more dry weather. And that means regions and cities across South Africa could soon be facing their own Day Zero—for some it has already arrived.

KwaZulu-Natal province is no stranger to drought. In 2019, rural communities south of Durban had to survive weeks without municipal water, depending instead upon unreliable tanker trucks. By November, protracted drought saw the province’s south coast suffering severe shortages as water sources dried up. There were calls for the town of Harding to be declared a disaster area, and urgent proposals for a bulk pipeline to secure its water supply- an expensive and complicated undertaking in a country where similar builds suffer from delays, cancellations, and poor workmanship. Meanwhile, Durban is losing around 35 percent of its municipal supply to theft and illegal connections, undermining the income needed to fund such vital improvements. Right now, the rains are falling, but unless supply improves and demand falls, towns across KwaZulu-Natal’s south coast district face their own looming Day Zero. It’s a familiar story across South Africa.

Gauteng province draws its water from the Integrated Vaal River System that includes a huge water transfer via the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. Last October, Johannesburg residents were hit with precautionary water restrictions when the Vaal Dam levels dropped to 53 percent, and planned maintenance stopped Lesotho’s water transfers for two months. To many, this highlighted the fragility of their water supply. Gauteng’s population is increasing rapidly, with domestic supply the fastest-growing sector, but its available water won’t increase until the Polihali Dam is completed in 2026. To avoid a water crisis, Gauteng must reduce water use in order to deal with population growth—cutting it by three percent per person per year. Last October’s heatwaves saw daily consumption rise by 264 million gallons (1,000 million liters), and compounded by infrastructure problems, suburban faucets ran dry in the capital. Without the certainty of six years of good rains, Johannesburg and Pretoria need to follow Cape Town’s lead and actively cut their water use.

In Eastern Cape, a crippling drought coupled with inadequate contingency plans left thousands without water last year. In the town of Adelaide, the dam dropped to just one percent of capacity and even then the authorities couldn’t act because they lacked funds. With no proper rain for at least five months, October saw councils in five municipalities declare drought disasters with calls for national disaster status. With many rivers and springs already dried up, even boreholes proved ineffective as groundwater became scarce because of the lack of rainfall to recharge it. Water recently released from a dam on the Kubusi River is providing some respite for towns like Butterworth, with supplies tankered out to surrounding communities, but the region is desperate for funds to be found for more substantial solutions to their ongoing water worries.

You May Also Like

Caitlin Ochs documents the Colorado River’s water shortage crisis

Your biggest AI questions, answered

Here’s what worries engineers the most about U.S. infrastructure

Northern Cape’s reliance on rain-fed agriculture has seen years of serious drought devastate its agricultural sector. Abnormally hot weather and below average rainfall has scorched grazing lands and dried up watering holes, with wholesale livestock deaths and crop failures bringing financial ruin to farmers and a spike in food prices. It’s estimated that at least $40 million (R600 million) is needed to alleviate the drought’s effects and secure more than 60,000 jobs dependent on agriculture. The drought has also wiped out more than two-thirds of the province’s game, and there is the threat of total water supply failure for some towns; Kimberley cut its water supplies at night to reduce consumption. In January the rain began falling again but there is still a clear need for water saving measures and more efficient methods of agriculture, from installing drip irrigation systems to planting crops that can survive the even harsher droughts that future climate change could bring.

YEAR-LONG ADVENTURE for every explorer on your list

For Cape Town itself, Day Zero hasn’t disappeared, it’s merely been delayed. While the catastrophic shortage that nearly turned off its faucets was narrowly averted, Capetonians continue to survive on much less than they were used to—just over 27 gallons (105 liters) per person per day. These stringent restrictions, combined with new dam projects and desalination schemes, are keeping Cape Town sated if not exactly splashing through the summer—its dams are currently at around 70 percent capacity. However, in Free State province the town of QwaQwa needed 5,000 water tankers to provide immediate relief for its water shortage, while elsewhere in South Africa, the last couple of years have seen water restrictions in Limpopo province, faucets running dry in in Mpumalanga province, and the allocation of $20 million (R300 million) to upgrade failing water infrastructure in the North West province.

Across South Africa, water stress is a priority problem, but with no single cause there is no single solution. Each area experiences water issues caused to different degrees by excessive use, growing demand, pollution, theft, thirsty plants, inadequate infrastructure, and poor practices. Solving these issues not only requires financial investment but also a change in attitude. South Africa cannot support the water lifestyle some residents consider to be their right, fueling a water consumption that’s 35 percent above the global average. The Draft National Water and Sanitation Masterplan laid it out clearly: without a fundamental mind shift in the way South Africa thinks about water to accompany and underpin a massive $60 billion (R899 billion) investment, the country will run out of water by 2030. It’s a sobering message; while for many South Africans a little rain brings hope, hope alone will not guarantee South Africa’s water supply.

Related Topics

- ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION

- WATER CONSERVATION

- WATER RESOURCES

10 of the best low-impact U.S. adventures

How travelers can help protect the Great Barrier Reef's corals

Sharks are still being killed at high rates—despite bans on finning

Steve Boyes traces life to its source in the Angolan Highlands

The Chicago River was a toxic wasteland. Now it's an urban oasis.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Cape Town almost ran out of water. Here's how it averted the crisis

South African dams are now over 80% full. Image: REUTERS/Euroluftbild.de

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Charlotte Edmond

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Fresh Water is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, fresh water.

Cape Town’s water crisis got so bad last year that there were competitions to see who could wash their shirts the least. Restaurants and businesses were encouraging people not to flush after going to the toilet. The city was just 90 days away from turning off the taps.

A year on, the South African city’s parched dams are now over 80% full . Water use restrictions have been relaxed. And Day Zero – the point at which Cape Town’s municipal water supply would be shut off – never came to pass.

Having been threatened by one of the worst-ever drought-induced municipal water crises, residents became water-wise.

A city united

In a dry climate, with rapid urbanization and relatively high per capita water consumption, Cape Town had all the makings of a water crisis. In 2018, after three years of poor rainfall, the city announced drastic action was needed to avoid running out.

Reducing demand was a key priority. The City of Cape Town worked to get residents and businesses on board with a host of water-saving initiatives. People were instructed to shower for no longer than two minutes. A campaign with the slogan “If it’s yellow, let it mellow” promoted flushing the toilet only when necessary. And the use of recycled water – so-called greywater – was also pushed.

The world is not on track to achieve Sustainable Development Goal No. 6 on water and sanitation. At the current rate, there will be a 40% gap between global water supply and demand by 2030.

We’re helping to close the gap between global water demand and supply. The 2030 Water Resources Group (2030 WRG) was launched at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2008 in Davos, Switzerland, to help close the gap between global water demand and supply by 2030.

Since its inception, the Forum-initiated 2030 WRG has grown into a vibrant network of more than 700 partners from the private sector, government and civil society. To date, the 2030 WRG and its network have facilitated over $893 million of financing for water-related programmes and demonstrated tangible results in a number of areas, including agricultural water efficiency, urban and industrial water management, wastewater treatment and improved livelihoods for farmers.

Want to join our mission to close the gap between global water supply and demand? Find out more about our impact , and help us improve the state of the world.

At the most extreme, residents were restricted to a maximum of 50 litres a day – not easy when showers alone can use up to 15 litres a minute. Backed up with data on each household’s water use , people pulled together, sharing tips on social media.

Restricted supply

The City of Cape Town introduced increasingly strict restrictions, which as well as limiting the volumes allowed, also restricted what the water was used for. Filling swimming pools , washing cars, and fountains were all banned.

Households using high volumes of water faced big fines. The city also significantly hiked tariffs as well as rolling out management devices, which set a daily limit on the water supply to properties.

What is the World Economic Forum on Africa?

With elections taking place in more than 20 African countries in 2019, the world’s youngest continent is facing a new era.

Held under the theme 'Shaping Inclusive Growth and Shared Futures in the Fourth Industrial Revolution' the 28th World Economic Forum on Africa will convene more than 1,000 regional and global leaders from government, business, civil society and academia.

The event (held 4-6 September 2019) will explore new regional partnerships and entrepreneurial and agile leadership to create pathways for shared prosperity and drive a sustainable future.

Participants will discuss ways to accelerate progress on five transformative pan-African agendas in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, addressing the African Union’s Agenda 2063 priorities.

Read more about the Forum's Impact in Africa and our launch of a new Africa Growth Platform to scale the region’s start-ups for success.

Read our guide to how to follow #af19 across our digital channels. We encourage followers to post, share, and retweet by tagging our accounts and by using our official hashtag.

Become a Member or Partner to participate in the Forum's year-round annual and regional events. Contact us now .

Another method of curbing use saw the city reduce the water pressure, which both cut overall consumption as well as decreased the loss through leaks.

Alongside measures targeted at domestic use, Cape Town also called on the agricultural and commercial sectors. Hard limits on agricultural water quotas were introduced.

Crisis averted… for now

By changing a city’s habits, along with the welcome return of some rain, Cape Town managed to avert the worst of the water scarcity crisis. However, the risk of future shortages remain. South Africa is one of the world’s driest countries and demand for water continues to climb .

According to the WWF, demand is set to reach 17.7 billion m³ by 2030 - up from 13.4 billion m³ in 2016 - outstripping what the country is able to allocate .

Have you read?

Climate change has influenced global drought risk for ‘more than a century’, 5 droughts that changed human history, cape town's drought is causing the economy to dry up too, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Nature and Biodiversity .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-zh0r2a{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;padding-left:0px;padding-right:0px;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-zh0r2a{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-zh0r2a{font-size:1rem;}} See all

What are neglected tropical diseases – and what are we doing about them?

Victoria Masterson and Rebecca Geldard

October 24, 2024

How innovative financing instruments are accelerating action on nature

Alessandro Valentini

October 23, 2024

Ocean biodiversity is under threat and technology can help save it

October 22, 2024

How sustainable tourism helps protect mountain gorillas in Rwanda and strengthens communities

Christian Benimana and Eugene Muntangana

October 21, 2024

Nature Finance and Biodiversity Credits: A Private Sector Roadmap to Finance and Act on Nature

How the Global Future Councils use 'knowledge collisions' to address today’s challenges

Mirek Dušek

share this!

October 22, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

reputable news agency

In South Africa, water shortages are the new reality

by Louise DEWAST

Joyce Lakela runs a nursery in Tembisa, a Johannesburg township, but these days she spends most of her time trying to find water.

"It's been going on for five days," she said, lamenting shortages affecting South Africa's largest city where temperatures are rising with the beginning of summer.

"This is a big challenge," the elderly woman said, after filling up a large bin with water from a tanker. "The kids have to wash their hands, we have to flush the toilets, and we also have to wash the kids."

The crisis is the result of daily restrictions imposed by the city to stop what they say is over-consumption and to allow maintenance work.

While there is enough water in the country's reserves, for individuals like Lakela, who already faced months of electricity shortages last year, the reality is that taps are going dry for hours and sometimes days.

Last week, residents of Westbury and Westdene, suburbs to the west of the central business district, blocked the streets in protest against water outages. They burned tires and blocked a road with rocks and debris.

Businesses and services have also been affected, including at least one hospital in northern Gauteng, the province of 16 million people which includes Johannesburg and the capital, Pretoria.

Delays, leaks

This comes after Rand Water, the water supplier for Gauteng, this month warned over high water consumption and instructed municipalities to impose daily limits.

"Water storage could soon be depleted if municipalities do not implement our recommendations. It is essential to act now to prevent the impending disaster," Rand Water said in a statement on October 12.

The water company is not just worried about consumers leaving taps on. There are also leaks and "illegal connections", or theft by individuals who divert pipelines and do not pay bills.

"We are losing an average of over 40 percent (of our water) if you look at it in Gauteng," Makenosi Maroo, a spokeswoman for the utility, told AFP.

Municipalities often cite leaks as a reason for maintenance-related outages.

"We're not replacing anywhere near as much infrastructure as we should be," said Craig Sheridan, director of the Center in Water Research and Development at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

For Chris Herold, another water expert, "one of the main problems is that they (the municipalities) are incompetently run, and there's also a lot of corruption which is hindering the efficient running of water systems."

Municipalities insist that they are doing what they can with the resources they have. According to at least one city in the province, Ekurhuleni, it is the utility that is not providing enough water and leaving the reservoirs empty.

But Rand Water is only licensed to withdraw a fixed amount approved by the Department of Water and Sanitation.

Already back in 2009, it was clear that more was needed as Gauteng's population was rapidly expanding. The government made a deal with neighboring Lesotho to expand the bulk water supply to Rand Water.

The project initially meant for 2018 has been delayed until 2028 and as a result, sporadic restrictions to reduce demand are likely to continue.

Climate change

The rules could become more severe if South Africans do not change their habits, authorities have warned, adding that there could also be "financial implications".

The country is already considered water scarce, with an average annual precipitation of 495mm compared to the global average of around 990mm per year, and a warming planet will exacerbate the issue.

Under a moderate climate change scenario, in which global emissions peak around 2040 and then decline, the amount of precipitation could fall by as much as 25 percent in South Africa by the end of the century.

The estimates were released in a report published this month by the Global Commission on the Economics of Water.

"There's definitely a sense of urgency," said Sheridan, who is particularly concerned by the health risks linked to turning water systems on and off, which has been South Africa's short term solution.

"When a pipe is full of water, the water leaks out of it. If the pipe is empty, then a leaking sewer next to it can potentially contaminate the supply."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Stoneflies have changed color as a result of human actions, new study shows

10 hours ago

Millions in the US may rely on groundwater contaminated with PFAS for drinking water supplies

Synthetic asexual reproduction system in hybrid rice shows promise for seed production

AI-generated news is harder to understand, study shows

Ion-pairing: A new approach to lyotropic chromonic liquid crystal assembly

Analysis shows no significant PFAS emissions under approved waste incineration conditions

Decades in the making: Researchers leverage cryo-EM to capture high-resolution structure of an elusive protein

11 hours ago

How volatile organic compounds enhance plant defense and offer sustainable pest control solutions

Crustacean with panda-like coloring confirmed to be a new species

Burmese pythons can eat bigger prey than previously thought

Relevant physicsforums posts, the secrets of prof. verschure's rosetta stones.

Oct 23, 2024

Tracking hurricane Milton and its category rating

Oct 20, 2024

Should We Be Planting More Trees?

Hurricanes and the coriolis effect.

Oct 19, 2024

Why does crude oil seep out of the ground on this beautiful Caribbean Island?

Sep 7, 2024

Alaska - Pedersen Glacier: Landslide Triggered Tsunami

Aug 23, 2024

More from Earth Sciences

Related Stories

South Africa's Gauteng province launches water data hub, so residents can now keep track of shortages and repair issues

Sep 18, 2024

Q&A: Johannesburg has been hit by severe water shortages—new plan to manage the crisis isn't the answer

Oct 5, 2023

Water crisis threatening world food production: report

Oct 17, 2024

South Africa's biggest cities are out of water, but the dams are full: What's gone wrong?

Oct 19, 2022

South Africa urges water restrictions as dam levels drop

Oct 28, 2019

Why full dams don't mean water security: A look at South Africa

May 25, 2021

Recommended for you

Wildfires are becoming faster and more dangerous in the Western US: Study

13 hours ago

$79 billion—the hidden climate costs of US materials production

23 hours ago

Future atmospheric rivers could bring catastrophic ocean level rise off the West Coast, simulation study shows

Scientists determine the timing and duration of a major hyperthermal event in the Early Jurassic

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Water Scarcity In South Africa Essay. Great Essays. 1417 Words. 6 Pages. Open Document. Essay Sample Check Writing Quality. Show More. Everyday about 30,000 children die from contaminated water. The lack of fresh water in South Africa has been the reason of most diseases in Africa for many children.

What Led to A Water Crisis in South Africa? As experts in the field have agreed, the water crisis in South Africa can likely be attributed to economic (a lack of investment), as well as physical (a lack of rain) water scarcity. In an article, spokesman for the government committee appointed to respond to the water crisis in South Africa Luvuyo ...

This brief investigates whether observed water scarcity in South Africa can be attributed to physical or economic factors, or both. South Africa is often described as a water-scarce country. This is based principally on physical descriptors like climatic conditions and escalating water demands.

The normal national water storage percentage for South Africa is typically between 85% and 80%. The drought from 2015 to 2018 depleted the country’s water storage levels, especially during...

OUTH AFRICA IS CONSIDERED TO BE A WATER SCARCE COUNTRY and, if the current rate of water usage continues, demand is likely to exceed supply at some point in the not-too-distant future. The improvement of water conserva-tion, water quality and water-use efficiency is a key national priority, when compared

Cape Town may have dodged the Day Zero bullet, but all across South Africa drought and rising demand is escalating a national water crisis.

Not only is South Africa plagued by severe drought conditions, but it also has a poor record of water conservation, outdated and inadequate water treatment infrastructure, and lingering...

By changing a city’s habits, along with the welcome return of some rain, Cape Town managed to avert the worst of the water scarcity crisis. However, the risk of future shortages remain. South Africa is one of the world’s driest countries and demand for water continues to climb.

South Africa is already considered water scarce, with an average annual precipitation of 450mm per year compared to the global annual average of 786mm per year, and a warming planet will ...

South Africa is a water-scarce country. Yet there are extant, affordable technologies that government, business and private individuals could employ to help realign supply and demand while ensuring water security for future generations.