- Social Sciences

- Natural Sciences

- Formal Sciences

- Professions

- Extracurricular

Frida Kahlo Essay

Frida Kahlo By: Heather Waldroup

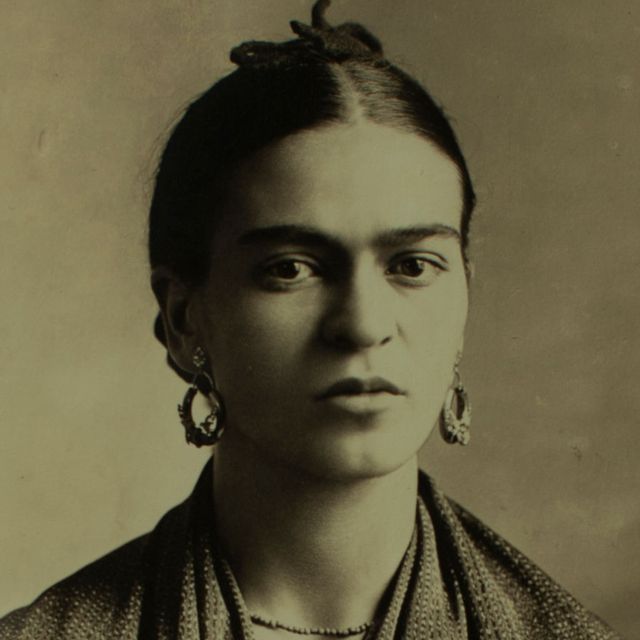

Frida Kahlo was a female Mexican painter of mixed heritage, born on July 6, 1907 and lived 47 painful years before passing away on July 13, 1954. Within her short life, Frida was slightly crippled from polio, suffered from a serious streetcar accident that left her infertile, married famous muralist Diego Rivera, divorced, remarried Rivera, became a political activist and rose to fame through her oil paintings all before succumbing to her poor health. She was an intelligent female in a society that wanted women to be pretty, submissive wives and mothers. She struggled with cultural demands of her gender in a time when women were demanding a change in their role. All these aspects of her life, and more, affected her art. She was a modern woman but her art had an indigenous background. Her most common genre was self-portrait and through a dramatic views of herself, she was capable of showing her view of the world. Frida was an active member of global society and was a powerful speaker for her beliefs through her art. Her art was controversial and attracted attention. She gained global recognition of her work because it’s complex and provocative, demanding discussion.

Frida Kahlo’s art seems very closely tied to the ups and downs of her marriage and her health. Her and her husband, Diego Rivera, had an unconventional, rocky relationship. There was a lack of fidelity on both parts. Diego was a well-known womanizer and it is thought that Kahlo reacted in kind as vengeance. A struggle exists between an artist and their work, I can only imagine the battles that occur when two artist marry. Within the beginning of their marriage, Frida painted Frida and Diego Rivera (Figure 1). At the time, Rivera was already a well known muralist twenty years her senior and her painting was thought to be no more than a hobby for a quiet wife. Throughout the years they knew each other, they continually painted the other. Frida overlaid his face on her forehead in Diego on my Mind (Figure 2) within which she also wears a dramatic, traditional Mexican headdress. Often times, in her self-portraits she’s wearing traditional Tahuana dress, as in Figure 1. Their marriage seemed to deteriorate in time with Kahlo’s rising success (Lindauer, 1999) until they divorced in 1939. Often times she has been criticized for focusing too much on her work instead of being the docile wife expected of her. The two remarried later that year but it was a financial arrangement and they did not share a marital bed.

While her husband is a common theme so are issues of her health. She often depicted her physical pain and struggle with graphic self-portraits. She “usually located narrative impact . . . directly onto her own body.” (Zavala, 2010) During her accident, she was impaled by a metal pole in her torso that exited through her vagina, breaking her pelvis in the process. She had extreme pain and struggled with the aftermath of her accident. The Broken Column (Figure 3) shows Kahlo’s nude torso with nails in her skin and her torso torn open to reveal a cracked column. The cracked pillar could be representative of the “broken column” of her spine. She was told she would most likely never carry a pregnancy to full term and this turned out to be true, unfortunately. After one of her miscarriages, Kahlo painted Henry Ford Hospital (Figure 4). It depicts the once again nude Kahlo on a bloody hospital bed, crying and holding images of a baby and a pelvis. She went through over 30 surgeries to try to repair the damage and she was just left in more pain. She’d started to lose faith in medicine when she painted Tree of Hope (Figure 5) where a prone, assumed Frida lies cut up and bleeding on a gurney while another Frida in a traditional dress holds a back brace. These self-portraits were a way for her to process the pain she felt. “In Frida’s work oil paint mixes with the blood of her inner monologue.” (Tibol, 1993) They are disturbing images that invoke fear in the viewer. Her pain is so blatantly displayed in her blood and nakedness that can be felt so strongly by the viewer. She demands you feel it with her direct stare.

Kahlo invoked such strong reactions to her work because they challenged traditional values with modern ideas, mixed with often violent and sexualized imagery. She used her art to bring attention to the mistreatment of women and to aid the feminist movement. A Few Small Nips (Figure 6) was painted after she read in the newspaper about a man who stabbed his cheating wife. Frida was herself a sexually promiscuous woman who’d had affairs with both men and women (Lindauer, 1999) so she would feel invested in how such women are viewed. She fought against the expectation of the meek female dressed up in lace and bows. She painted Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (Figure 7) in which she’s wearing a man’s suit and has sheared her hair off. Men felt extremely threatened by this and took it as an assault on all males after her divorce from Rivera. They insinuated her to be a fallen woman and their fury further showed the social imbalance (Lindauer, 1999).

There was an excess of disparity in her art between the traditional and the modern. This is shown most clearly in two of her pieces: My Dress Hangs There (Figure 8) and Self-Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States (Figure 9). Both paintings have clear American references, as well as other global iconography, as drastic comparisons to traditional Mexican culture. In Figure 8, the US capitol is centered and the Statue of Liberty is in the background. Capitalist iconography is represented by the billboard of a well-dressed woman and the gas pump, all placed in a metropolitan setting with the populous barely noticeable at the bottom of the painting. The artist’s Tehuana dress hangs in the center, offering the juxtaposition of the two. Figure 9 shows the inequality between the two nations with the artist straddling the line separating them. On the Mexican side there are symbols representing ancient Mexican religion and flowers are growing out of the dirt. The American side is completely urbanized. The paintings are considered her most politically explicit because they “portray the corruption, alienation and/or dehumanization” of Americans (Lindauer, 1999). Both of these pieces would’ve sparked discussion in the early 1930’s when they were painted. Nothing makes a topic more well known than controversy.

Frida Kahlo’s harsh life produced provocative images that challenged society. She was wise beyond her years and was a fiery, rebellious spirit. She was a member of las pelonas in college, a group of young, Mexican women who cut their hair, learned how to drive cars and wore androgynous clothing. While consulting a specialist on another serious spinal surgery, she told her physicians to send him every, to write him letters describing her character, so he would understand that she’s a fighter (Lindauer, 1999). She taught painting to youth across Mexico, affecting hundreds of lives with her mentorship. In her final days she left the hospital, despite doctors’ orders, to participate in a political protest. She was in a wheelchair, having lost a leg to gangrene, sickly thin, with colorful yarn tied into her hair. The things she saw and experienced led to the dramatic works that flowed from her brush. She hadn’t planned to follow in the artistic footsteps of her photographer father and grandfather. Yet, look at the silver lining of the tragedy of her accident. Instead of becoming a doctor, she painted pictures that made people talk and discuss. She is now recognizable worldwide for her unique self-portraits.

Bibliography

Zavala, Adriana. Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender, and

Representation in Mexican Art. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP,

2010. Print.

Lindauer, Margaret A. Devouring Frida: The Art History and Popular Celebrity of Frida

Kahlo. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1999. Print.

Tibol, Raquel. Frida Kahlo: An Open Life . University of New Mexico Press, 1993. Print.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Frida Kahlo, introduction

Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas) , 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City)

Sixty, more than a third of the easel paintings known by Frida Kahlo are self-portraits. This huge number demonstrates the importance of this genre to her artistic oeuvre. The Two Fridas , like Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair , captures the artist’s turmoil after her 1939 divorce from the artist Diego Rivera. At the same time, issues of identity surface in both works. The Two Fridas speaks to cultural ambivalence and refers to her ancestral heritage. Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair suggests Kahlo’s interest in gender and sexuality as fluid concepts.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair , 1940, oil on canvas, 40 x 27.9 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City)

Kahlo was famously known for her tumultuous marriage with Rivera, whom she wed in 1929 and remarried in 1941. The daughter of a German immigrant (of Hungarian descent) and a Mexican mother, Kahlo suffered from numerous medical setbacks including polio, which she contracted at the age of six, partial immobility—the result of a bus accident in 1925, and her several miscarriages. Kahlo began to paint largely in response to her accident and her limited mobility, taking on her own identity and her struggles as sources for her art. Despite the personal nature of her content, Kahlo’s painting is always informed by her sophisticated understanding of art history, of Mexican culture, its politics, and its patriarchy.

The Two Fridas

Exhibited in 1940 at the International Surrealist Exhibition , The Two Fridas depicts a large-scale, double portrait of Kahlo, rare for the artist, since most of her canvases were small, reminiscent of colonial retablos , small devotional paintings. To the right Kahlo appears dressed in traditional Tehuana attire, different from the nineteenth century wedding dress she wears at left and similar to the one worn by her mother in My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) (1936).

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) , 1936, oil and tempera on zinc, 30.7 x 34.5 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City)

Whereas the white dress references the Euro-Mexican culture she was brought up in, in which women are “feminine” and fragile, the Tehuana dress evokes the opposite, a powerful figure within an indigenous culture described by some at the time as a matriarchy. This cultural contrast speaks to the larger issue of how adopting the distinctive costume of the indigenous people of Tehuantepec, known as the Tehuana, was considered not only “a gesture of nationalist cultural solidarity,” but also a reference to the gender stereotype of “ la india bonita. ” [1] Against the backdrop of post-revolutionary Mexico, when debates about indigenismo (the ideology that upheld the Indian as an important marker of national identity) and mestizaje (the racial mixing that occurred as a result of the colonization of the Spanish-speaking Americas) were at stake, Kahlo’s work can be understood on both a national and personal level. While the Tehuana costume allowed for Kahlo to hide her misshapen body and right leg, a consequence of polio and the accident, it was also the attire most favored by Rivera, the man whose portrait the Tehuana Kahlo holds. Without Rivera, the Europeanized Kahlo not only bleeds to death, but her heart remains broken, both literally and metaphorically.

Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair

Frida Kahlo, detail with hemostat, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas) , 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City) (photo: Dave Cooksey, CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In opposition, the painting Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair boldly denounces the femininity of Two Fridas . In removing her iconic Tehuana dress, in favor of an oversized men’s suit, and in cutting off her braids in favor of a crew cut, Kahlo takes on the appearance of none other than Rivera himself. At the top of the canvas, Kahlo incorporates lyrics from a popular song, which read, “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.” In weaving personal and popular references, Kahlo creates multilayered self-portraits that while rooted in reality, as she so adamantly argued, nevertheless provoke the surrealist imagination. This can be seen in the visual disjunctions she employs such as the floating braids in Self Portrait with Cropped Hair and the severed artery in Two Fridas . As Kahlo asserted to Surrealist writer André Breton, she was simply painting her own reality.

[1] Adriana Zavala, Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender, and Representation in Mexican Art (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), p. 3

Bibliography

Frida Kahlo: Embracing Her Masculinity on ArtUK

Faces of Frida, Google Cultural Institute

Read about Freida and Diego Rivera

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Frida Kahlo

Introduction.

- Scholarly Biographies

- General Interest Biographies

- Bibliographies and Review Essays

- Artist’s Correspondence, Writings, and Medical Records

- Accounts and Memoirs by Contemporaries

- Catalogue Raisonné

- Retrospective Exhibition Catalogues

- Thematic Exhibition Catalogues

- Group Exhibition Catalogues

- General Overviews

- Postrevolutionary Aesthetics and Culture

- Feminist Approaches

- Sexuality and Gender

- Self-Fashioning

- Home and Nature

- Spirituality and Religion

- Medical Imagery and Interpretation

- Kahlo’s Diary

- Kahlo as Art World Inspiration

- Kahlo and Forgery

- Frida Kahlo as Photographic Subject

- Guillermo Kahlo

- Documentaries, Films, and Scholarly Analysis

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Diego Rivera

- Marxism and Art

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Artists in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Brazil

- Color in European Art and Architecture

- European Art and Diplomacy in the Global Early Modern Period

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Frida Kahlo by Adriana Zavala LAST REVIEWED: 30 March 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 30 March 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199920105-0108

Although Frida Kahlo (b. 1907–d. 1954) is one of the world’s most widely recognized artists, that attention is often focused more on her dramatic life story than on the complexity of her intellect and artistic production. She is known for her self-portraits, which may appear straightforward and narrative, but throughout her career she employed allegory and complex symbolism. Like the muralists, not least her husband Diego Rivera (see the separate Oxford Bibliographies article “ Diego Rivera ”), Kahlo considered painting a social and political act central to the creation of a revolutionary Mexico, yet she produced fewer than two hundred paintings and fewer than one hundred works on paper. In a 1943 essay, Rivera praised her as the paragon of Mexican revolutionary painting. While her formal academic training was relatively minimal, her proximity to Rivera provided access to intellectual and political circles in Mexico and abroad, and this influenced both the style and conceptual basis of her painting. Kahlo was also exceptionally educated; she read or spoke English, German, and French. She enrolled at Mexico City’s prestigious National Preparatory School in 1922 where she was one of only thirty-five women among the 2000 students; early on, her aim was to study medicine. In 1925 she was involved in a traffic accident that ended her formal studies. She turned to painting. Early works demonstrate intellectual curiosity about avant-garde innovations, combined with the deliberately naïve style of painting in vogue in postrevolutionary Mexico and elsewhere that drew inspiration from folk art and provincial and nonacademic painting. She deployed both to create work that was culturally and politically resonant as well as transgressive and transcultural. Kahlo’s work must therefore be examined in relation to her knowledge of art history, avant-garde movements, and modernist innovation, as well as her life’s events and cultural context. Her influences range from Italian early Renaissance and Mannerist painting to Indian miniatures, Mexican folk art and social realism, and German Neue Sachlichkeit and the Italian pittura metafisica , and of course, surrealism. While she may have drawn inspiration from her life’s experience, her art was much more than unmediated psychological expression or autobiography in paint as some sources claim. During her life, she was known principally as Rivera’s flamboyant wife, but in the early 21st century, Kahlo is one of the world’s most celebrated women. Biographies, monographs, and retrospective exhibitions abound, and the market for trade and scholarly publications on Kahlo is evidently insatiable. There is no question that she was an extraordinary personality. Her approach to depicting physical pain and emotional complexity along with her interest in self-portraiture has fueled the myth that her paintings are illustrations of her life events in chronological order rather than allegorical works that spring from the personal, as well as mediated engagements with political and cultural trends. Kahlo’s present iconic status results in part from an oversimplified understanding as well as admiration for her creativity and perseverance, all of which fuel the mythologizing phenomenon known as Fridamania .

Biographies

Kahlo biographies are a lucrative commercial industry aimed at readers at all levels from children to teens, general audiences, and college students. Even the best tend to sublimate her artistic production to a narrative focused on tragedy, emotional and physical pain, and marital strife. Given the personal basis of much of Kahlo’s iconography, there is no question that her biography can be of value in interpreting her painting, but serious students are cautioned not to reduce her work to autobiographical painting. Claims, explicit and implicit, that Kahlo herself is more interesting than her painting are unfounded but not uncommon. Students of Kahlo should be sure to seek informed art historical analysis. Kahlo lived during one of Mexico’s most tumultuous eras, yet even the best biographies tend to decontextualize her art and intellect, treating her work in relative isolation. Several widely cited biographies lack citations to primary or secondary sources, and this approach often perpetuates a psychologized interpretation of her painting. Biographies are, therefore, grouped as Scholarly Biographies and General Interest Biographies .

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Art History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Activist and Socially Engaged Art

- Adornment, Dress, and African Arts of the Body

- Alessandro Algardi

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Ancient Pueblo (Anasazi) Art

- Angkor and Environs

- Art and Archaeology of the Bronze Age in China

- Art and Architecture in the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary

- Art and Propaganda

- Art of Medieval Iberia

- Art of the Crusader Period in the Levant

- Art of the Dogon

- Art of the Mamluks

- Art of the Plains Peoples

- Art Restitution

- Artemisia Gentileschi

- Arts of Senegambia

- Arts of the Pacific Islands

- Assyrian Art and Architecture

- Australian Aboriginal Art

- Aztec Empire, Art of the

- Babylonian Art and Architecture

- Bamana Arts and Mande Traditions

- Barbizon Painting

- Bartolomeo Ammannati

- Bernini, Gian Lorenzo

- Bohemia and Moravia, Renaissance and Rudolphine Art of

- Borromini, Francesco

- Brazilian Art and Architecture, Post-independence

- Burkina Art and Performance

- Byzantine Art and Architecture

- Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da

- Carracci, Annibale

- Ceremonial Entries in Early Modern Europe

- Chaco Canyon and Other Early Art in the North American Sou...

- Chicana/o Art

- Chimú Art and Architecture

- Colonial Art of New Granada (Colombia)

- Conceptual Art and Conceptualism

- Contemporary Art

- Courbet, Gustave

- Czech Modern and Contemporary Art

- Daumier, Honoré

- David, Jacques-Louis

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Design, Garden and Landscape

- Destruction in Art

- Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS)

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Early Christian Art

- Early Medieval Architecture in Western Europe

- Early Modern European Engravings and Etchings, 1400–1700

- Eighteenth-Century Europe

- Ephemeral Art and Performance in Africa

- Ethiopia, Art History of

- European Art, Historiography of

- European Medieval Art, Otherness in

- Expressionism

- Eyck, Jan van

- Feminism and 19th-century Art History

- Festivals in West Africa

- Francisco de Zurbarán

- French Impressionism

- Gender and Art in the Middle Ages

- Gender and Art in the Renaissance

- Gender and Art in the 17th Century

- Giotto di Bondone

- Gothic Architecture

- Gothic Art in Italy

- Goya y Lucientes, Francisco José

- Great Zimbabwe and its Legacy

- Greek Art and Architecture

- Greenberg, Clement

- Géricault, Théodore

- Iconography in the Western World

- Installation Art

- Islamic Art and Architecture in North Africa and the Iberi...

- Japanese Architecture

- Japanese Buddhist Painting

- Japanese Buddhist Sculpture

- Japanese Ceramics

- Japanese Literati Painting and Calligraphy

- Jewish Art, Ancient

- Jewish Art, Medieval to Early Modern

- Jewish Art, Modern and Contemporary

- Jones, Inigo

- Josefa de Óbidos

- Jusepe de Ribera

- Kahlo, Frida

- Katsushika Hokusai

- Lastman, Pieter

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Luca della Robbia (or the Della Robbia Family)

- Luisa Roldán

- Markets and Auctions, Art

- Medieval Art and Liturgy (recent approaches)

- Medieval Art and the Cult of Saints

- Medieval Art in Scandinavia, 400-800

- Medieval Textiles

- Meiji Painting

- Merovingian Period Art

- Modern Sculpture

- Monet, Claude

- Māori Art and Architecture

- Museums in Australia

- Museums of Art in the West

- Native North American Art, Pre-Contact

- Nazi Looting of Art

- New Media Art

- New Spain, Art and Architecture

- Pacific Art, Contemporary

- Palladio, Andrea

- Parthenon, The

- Paul Gauguin

- Performance Art

- Perspective from the Renaissance to Post-Modernism, Histor...

- Peter Paul Rubens

- Philip II and El Escorial

- Photography, History of

- Pollock, Jackson

- Polychrome Sculpture in Early Modern Spain

- Postmodern Architecture

- Pre-Hispanic Art of Columbia

- Psychoanalysis, Art and

- Qing Dynasty Painting

- Rembrandt van Rijn

- Renaissance and Renascences

- Renaissance Art and Architecture in Spain

- Rimpa School

- Rivera, Diego

- Rodin, Auguste

- Romanticism

- Science and Conteporary Art

- Sculpture: Method, Practice, Theory

- South Asia and Allied Textile Traditions, Wall Painting of

- South Asia, Modern and Contemporary Art of

- South Asia, Photography in

- South Asian Architecture and Sculpture, 13th to 18th Centu...

- South Asian Art, Historiography of

- The Art of Medieval Sicily and Southern Italy through the ...

- The Art of Southern Italy and Sicily under Angevin and Cat...

- Theory in Europe to 1800, Art

- Timurid Art and Architecture

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William

- van Gogh, Vincent

- Warburg, Aby

- Warhol, Andy

- Wari (Huari) Art and Architecture

- Wittelsbach Patronage from the late Middle Ages to the Thi...

- Women, Art, and Art History: Gender and Feminist Analyses

- Yuan Dynasty Art

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Famous Artists — Frida Kahlo

Essays on Frida Kahlo

Brief description of frida kahlo.

Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist known for her powerful self-portraits and depiction of indigenous Mexican culture. Her work is celebrated for its raw emotion and unapologetic portrayal of pain and resilience. Kahlo's impact extends beyond the art world, as she is an icon of feminism, disability rights, and Mexican identity.

Importance of Writing Essays on This Topic

Essays on Frida Kahlo offer a unique opportunity to explore the intersections of art, identity, and activism. By analyzing Kahlo's life and work, students can gain insight into the complexities of gender, nationality, and physical and emotional pain. Writing about Kahlo also allows for critical engagement with the representation of marginalized voices in art history.

Tips on Choosing a Good Topic

- Consider themes in Kahlo's work, such as identity, pain, and resilience, and how they relate to contemporary issues.

- Explore lesser-known aspects of Kahlo's life, such as her political activism or her relationships with other artists.

- Examine the influence of Kahlo's Mexican heritage on her art and how it shapes her representation in the global art world.

Essay Topics

- The portrayal of physical and emotional pain in Frida Kahlo's self-portraits.

- The intersection of feminism and nationalism in Kahlo's art.

- The impact of Kahlo's disability on her artistic practice.

- Exploring the symbolism in Kahlo's use of indigenous Mexican imagery.

- How Kahlo's personal life influenced her artistic style and subject matter.

- The enduring legacy of Frida Kahlo's art in contemporary culture.

Concluding Thought

Writing essays on Frida Kahlo offers a rich opportunity for critical thinking and personal exploration. By delving into the life and work of this iconic artist, students can gain valuable insights into the complexities of identity, representation, and artistic expression. Embracing this topic can lead to a deeper understanding of art, history, and social justice.

Identity of Frida Kahlo in Her Art Works

A journey through the eyes of frida kahlo, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Frida Kahlo: Biography, Paintings and Facts

The life story of famous mexican artist frida kahlo, frida kahlo and the impact of her accomplishments on the world, life path of frida kahlo, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Role of Human Condition in Frida Kahlo Art Works

Contextual analysis of the two fridas by frida kahlo, analysis of frida kahlo’s art work "the two fridas", the power of art in speaking to the community: frida kahlo and andy warhol, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

A Critique of The Different Works of Frida Kahlo

Understanding frida kahlo’s "the two fridas" through rhetorical analysis, frida kahlo: accomplishments and life, the famous paintings and accomplishments of frida kahlo, romantic relationships in the poems the origin of the milky way and little houses, analysis of the two fridas painting and its historical context, magical realism in kahlo’s the wounded deer and kafka’s metamorphosis, analysis and interpretation of frida kahlo's painting two fridas, picasso and kahlo: a comparative study, picasso vs. frida kahlo:contrasting artistic legacies, relevant topics.

- Vincent Van Gogh

- Ethnography

- Art History

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Frida Kahlo’s Art Through a Biographical Study Essay

Introduction, works cited.

Frida Kahlo was a famous artist and master of surrealism, born in 1907 in Mexico. The Mexican artist’s extraordinarily lively and vivid biography is a fascinating story of rebellious art, romantic beliefs, eccentric love affairs, and endless physical suffering. After Kahlo’s death, not only canvases remained, but also burning lines of memoirs, illustrating the unbending will, infinite pain, and love that is not given to everyone. American feminists, lesbians, and gays consider Frida Kahlo their forerunner, and during the artist’s lifetime, even Andre Breton was counted among her camp. Frida was great and many-faced, and although more than half a century has passed since her death, admiration for this legendary woman has not faded to this day. The interest in the works and personality of Frida Kahlo turned out to be viable. Frida Kahlo was an extravagant and talented artist, and through all her creativity and work, themes of inner feelings and personal misfortunes have passed like a red thread.

The Perspective of the Artist through a Biographical Study

Frida Kahlo has been used to fighting for herself since childhood, although nothing foreshadowed a hard life at her birth. It is known that Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico, and she was the third daughter of Guillermo Kahlo and Matilde Calderón y González (Doeden 8). The girl fell ill with polio at 6, after which she was left limp, and her right leg became deformed and weak (Doeden 9-10). The ordeal of the disease hardened Frida, who had grown up as a wayward child before. Thus, overcoming the pain, she played football with boys and went swimming and boxing classes. Furthermore, she suffered a severe car accident in her teens, after which she had to undergo numerous surgeries that affected her entire life. In this case, one should note that her paintings are a reflection of herself, and all her life, she painted, loved, had fun, and worried, overcoming physical pain.

The illness and regular visits to medics formed the girl’s desire to become a doctor. At 15, she enrolled at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria and studied medicine (Doeden 11-12). However, the lack of formal art education did not prevent Kahlo from painting independently, relying on her taste and intuition. The education allowed her to apply medical knowledge in some paintings, for example, in “Frida and the Cesarean Operation” in 1932 (Souter 51). In this artwork, Frida tried to reproduce the aesthetics of the anatomical atlas because once she wanted to connect her life with the healthcare sphere.

Social and Historical Influences

The attributes of various social circles and historical epochs were reflected in the great artist’s paintings. The revolutionary spirit of twentieth-century Mexico, as well as Native American motifs, brought a combination of aesthetics and sufferings to Kahlo’s works. Thus, her works are full of symbols and fetishes, revealed through national traditions, and closely related to the Amerindian mythology of the pre-Hispanic period. Furthermore, Frida communicated with many well-known personalities based on shared views. She was a political activist who sympathized with communism; these interests were echoed in the plots of some of her works. Nonetheless, her husband, the famous muralist Diego Rivera, exerted the most significant influence on Frida Kahlo’s painting style.

Gender and Ethnicity in the Critical Acclaim

It is no secret that both the gender and ethnicity of Frida Kahlo played a significant role in the critical acclaim of her work and in no way prevented her from gaining fame and popularity. Through her artworks, she told the whole world clearly and vividly about the issues of choosing gender and her independence. The paintings of the Mexican artist have become illustrations of the deep world of a woman. Frida turned herself into a work of art, and her life story became a myth. In addition, she actively emphasized in the paintings that she identifies as a Mexican and is proud of her roots. Her paintings have become an explosive mixture of Mexican folk motifs and naive art in the spirit of French modernists. Unfortunately, she did not become financially successful, but critics’ reviews were friendly, laudatory reviews were often written in newspapers, and works by Frida Kahlo praised Picasso and Kandinsky (Souter 93). One of the paintings was even bought by the Louvre. Mostly, critics were fascinated by her, her image, and the originality of her paintings.

Connections to Other Modernists and Impacts

Indeed, Frida Kahlo had many connections with other modernist creators. For example, she was friends with artists such as Marc Chagall, Piet Mondrian, and Pablo Picasso and married Diego Rivera. Furthermore, she admired the works of such modernists as Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Max Jacob. Having moved with her husband to the wildest and most revolutionary Morelos, Frida took over several concepts from the local modernist masters. She absorbed and adapted some ideas that became the basis of her future style. They include a lack of perspective, saturated and aggressive colors, national motifs, and a crazy combination of pre-Columbian and colonial styles. The influence of these persons can be seen in the magical art of Kahlo. Moreover, it was mentioned earlier that Frida Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera, in a sense, determined Frida’s manner, style, and technique of painting (Souter 5). Diego’s interest in the history and culture of Mexico changed not only Frida’s works but also her personality. In particular, Rivera created murals, and she was inspired by him.

Frida Kahlo was one of the most striking figures in twentieth-century art. Despite polio and a terrible accident, Frida managed to find herself and become one of the best artists in the world, maintaining fortitude until the last days. Her medical education and historical and social context significantly influenced her artworks. Moreover, Frida did not hide her origin and strongly emphasized femininity and Mexican roots in her paintings. In particular, she was associated with many personalities-modernists, which contributed to the development of Frida’s imagination, creativity, and exciting ideas.

Doeden, Matt. Frida Kahlo: Artist and Activist. Lerner Publications™, 2020.

Souter, Gerry. Frida Kahlo . Parkstone International, 2019.

- Taylor Swift’s Depiction in Genre, Culture, and Society

- Pete Seeger's Music and Civic Activism

- The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo: Art and Design

- Analysis of "The Broken Column" by Frida Kahlo

- Kahlo and Pollock Pictures Review

- Modernist Art: Pablo Picasso and Umberto Boccioni

- Andre Masson's Artistic Automatism Aesthetics

- Dickinson and Van Gogh: Artistic Expressions of Life and Emotion

- Pablo Picasso on Lie and Truth in Art

- The Special Beauty and Significance of Numbers

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 7). Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study. https://ivypanda.com/essays/frida-kahlos-art-through-a-biographical-study/

"Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study." IvyPanda , 7 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/frida-kahlos-art-through-a-biographical-study/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study'. 7 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study." February 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/frida-kahlos-art-through-a-biographical-study/.

1. IvyPanda . "Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study." February 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/frida-kahlos-art-through-a-biographical-study/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Frida Kahlo's Art Through a Biographical Study." February 7, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/frida-kahlos-art-through-a-biographical-study/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Frida Kahlo

Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

(1907-1954)

Quick Facts:

Who was frida kahlo, family, education and early life, frida kahlo's accident, frida kahlo's marriage to diego rivera, artistic career, frida kahlo's most famous paintings, frida kahlo’s death, movie on frida kahlo, frida kahlo museum, book on frida kahlo.

FULL NAME: Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón BORN: JULY 6, 1907 BIRTHPLACE: Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Cancer

Artist Frida Kahlo was considered one of Mexico's greatest artists who began painting mostly self-portraits after she was severely injured in a bus accident. Kahlo later became politically active and married fellow communist artist Diego Rivera in 1929. She exhibited her paintings in Paris and Mexico before her death in 1954.

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Kahlo's father, Wilhelm (also called Guillermo), was a German photographer who had immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. She had two older sisters, Matilde and Adriana, and her younger sister, Cristina, was born the year after Kahlo.

Around the age of six, Kahlo contracted polio, which caused her to be bedridden for nine months. While she recovered from the illness, she limped when she walked because the disease had damaged her right leg and foot. Her father encouraged her to play soccer, go swimming, and even wrestle — highly unusual moves for a girl at the time — to help aid in her recovery.

In 1922, Kahlo enrolled at the renowned National Preparatory School. She was one of the few female students to attend the school, and she became known for her jovial spirit and her love of colorful, traditional clothes and jewelry.

While at school, Kahlo hung out with a group of politically and intellectually like-minded students. Becoming more politically active, Kahlo joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party.

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo and Alejandro Gómez Arias, a school friend with whom she was romantically involved, were traveling together on a bus when the vehicle collided with a streetcar . As a result of the collision, Kahlo was impaled by a steel handrail, which went into her hip and came out the other side. She suffered several serious injuries as a result, including fractures in her spine and pelvis.

After staying at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks, Kahlo returned home to recuperate further. She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year, which she gave to Gómez Arias.

In 1929, Kahlo and famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera married. Kahlo and Rivera first met in 1922 when he went to work on a project at her high school. Kahlo often watched as Rivera created a mural called The Creation in the school’s lecture hall. According to some reports, she told a friend that she would someday have Rivera’s baby.

Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. He encouraged her artwork, and the two began a relationship. During their early years together, Kahlo often followed Rivera based on where the commissions that Rivera received were. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. They then went to New York City for Rivera’s show at the Museum of Modern Art and later moved to Detroit for Rivera’s commission with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kahlo and Rivera’s time in New York City in 1933 was surrounded by controversy. Commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller , Rivera created a mural entitled Man at the Crossroads in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller halted the work on the project after Rivera included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the mural, which was later painted over. Months after this incident, the couple returned to Mexico and went to live in San Angel, Mexico.

Never a traditional union, Kahlo and Rivera kept separate, but adjoining homes and studios in San Angel. She was saddened by his many infidelities, including an affair with her sister Cristina. In response to this familial betrayal, Kahlo cut off most of her trademark long dark hair. Desperately wanting to have a child, she again experienced heartbreak when she miscarried in 1934.

Kahlo and Rivera went through periods of separation, but they joined together to help exiled Soviet communist Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia in 1937. The Trotskys came to stay with them at the Blue House (Kahlo's childhood home) for a time in 1937 as Trotsky had received asylum in Mexico. Once a rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin , Trotsky feared that he would be assassinated by his old nemesis. Kahlo and Trotsky reportedly had a brief affair during this time.

Kahlo divorced Rivera in 1939. They did not stay divorced for long, remarrying in 1940. The couple continued to lead largely separate lives, both becoming involved with other people over the years .

While she never considered herself a surrealist, Kahlo befriended one of the primary figures in that artistic and literary movement, Andre Breton, in 1938. That same year, she had a major exhibition at a New York City gallery, selling about half of the 25 paintings shown there. Kahlo also received two commissions, including one from famed magazine editor Clare Boothe Luce, as a result of the show.

In 1939, Kahlo went to live in Paris for a time. There she exhibited some of her paintings and developed friendships with such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso .

Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In 1953, Kahlo received her first solo exhibition in Mexico. While bedridden at the time, Kahlo did not miss out on the exhibition’s opening. Arriving by ambulance, Kahlo spent the evening talking and celebrating with the event’s attendees from the comfort of a four-poster bed set up in the gallery just for her.

After Kahlo’s death, the feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity.

Many of Kahlo’s works were self-portraits. A few of her most notable paintings include:

'Frieda and Diego Rivera' (1931)

Kahlo showed this painting at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists, the city where she was living with Rivera at the time. In the work, painted two years after the couple married, Kahlo lightly holds Rivera’s hand as he grasps a palette and paintbrushes with the other — a stiffly formal pose hinting at the couple’s future tumultuous relationship. The work now lives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

'Henry Ford Hospital' (1932)

In 1932, Kahlo incorporated graphic and surrealistic elements in her work. In this painting, a naked Kahlo appears on a hospital bed with several items — a fetus, a snail, a flower, a pelvis and others — floating around her and connected to her by red, veinlike strings. As with her earlier self-portraits, the work was deeply personal, telling the story of her second miscarriage.

'The Suicide of Dorothy Hale' (1939)

Kahlo was asked to paint a portrait of Luce and Kahlo's mutual friend, actress Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide earlier that year by jumping from a high-rise building. The painting was intended as a gift for Hale's grieving mother. Rather than a traditional portrait, however, Kahlo painted the story of Hale's tragic leap. While the work has been heralded by critics, its patron was horrified at the finished painting.

'The Two Fridas' (1939)

One of Kahlo’s most famous works, the painting shows two versions of the artist sitting side by side, with both of their hearts exposed. One Frida is dressed nearly all in white and has a damaged heart and spots of blood on her clothing. The other wears bold colored clothing and has an intact heart. These figures are believed to represent “unloved” and “loved” versions of Kahlo.

'The Broken Column' (1944)

Kahlo shared her physical challenges through her art again with this painting, which depicted a nearly nude Kahlo split down the middle, revealing her spine as a shattered decorative column. She also wears a surgical brace and her skin is studded with tacks or nails. Around this time, Kahlo had several surgeries and wore special corsets to try to fix her back. She would continue to seek a variety of treatments for her chronic physical pain with little success.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FRIDA KAHLO FACT CARD

About a week after her 47th birthday, Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at her beloved Blue House. There has been some speculation regarding the nature of her death. It was reported to be caused by a pulmonary embolism, but there have also been stories about a possible suicide.

Kahlo’s health issues became nearly all-consuming in 1950. After being diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot, Kahlo spent nine months in the hospital and had several operations during this time. She continued to paint and support political causes despite having limited mobility. In 1953, part of Kahlo’s right leg was amputated to stop the spread of gangrene.

Deeply depressed, Kahlo was hospitalized again in April 1954 because of poor health, or, as some reports indicated, a suicide attempt. She returned to the hospital two months later with bronchial pneumonia. No matter her physical condition, Kahlo did not let that stand in the way of her political activism. Her final public appearance was a demonstration against the U.S.-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2nd.

Kahlo’s life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida , starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

The family home where Kahlo was born and grew up, later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul, was opened as a museum in 1958. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, the Museo Frida Kahlo houses artifacts from the artist along with important works including Viva la Vida (1954), Frida and Caesarean (1931) and Portrait of my father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952).

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 book on Kahlo, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , helped to stir up interest in the artist. The biographical work covers Kahlo’s childhood, accident, artistic career, marriage to Diego Rivera, association with the communist party and love affairs.

Watch the 2024 documentary, titled Frida , about the artist's life on Amazon Prime Video.

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

- My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

- I think that, little by little, I'll be able to solve my problems and survive.

- The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

- I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.

- I love you more than my own skin.

- I am not sick, I am broken, but I am happy as long as I can paint.

- Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

- I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned how to swim, and now I am overwhelmed with this decent and good feeling.

- There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.

- I hope the end is joyful, and I hope never to return.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Famous Painters

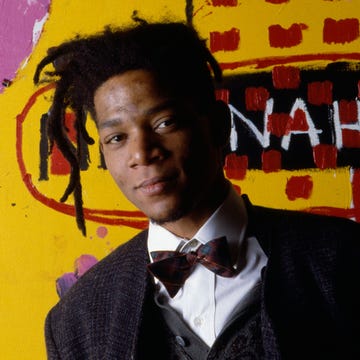

Jean-Michel Basquiat

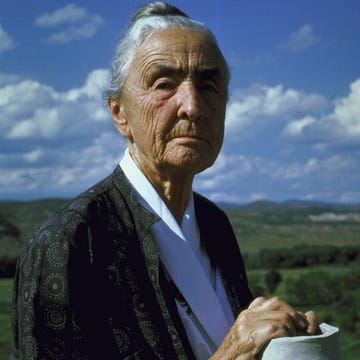

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Identity – Controversy – Justice

- #2 (no title)

- Picasso’s Guernica: The Story from a Bombing to a Painting

- Crying Girl Essay

- Barack Obama Essay

- Unsung Founders Essay

- A Tale of Two Hoodies

- El Agua Origen de la Vida Essay

Kahlo Essay

- Founding of Chicago Essay

- Japanese Triptych Essay

- Qing Vase Essay

- Crossing Sweeper Essay

- Begging for Change Essay

- Boy with Skittles Essay

- About this Exhibit

Frida Kahlo’s honest, often bizarre, self-portraits reflect a beauty beyond the physical– an impishness in the wide eyes, a small smirk teasing at the corners of her mouth. In her renderings, her cheeks are always heavily rouged, and exotic flowers adorn her raven hair. Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress uses the contrast of light — Kahlo’s glowing skin — and dark– the black background, and in doing so, this painting not only communicates the subject’s outward beauty. It also points to an unspoken turmoil inside of the painter: as dark as the night sky and as deep as rolling sea.

Much of Kahlo’s life was characterized by immense pain resulting from a lifelong battle with polio, and a bus accident in 1925 that left her crippled at the age of eighteen. It was in those lonely evenings, laid up in her hospital bed when Kahlo began to paint herself, as she was the only subject matter she had.

Frida Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907 in Mexico to Matilde Calderón and Guillermo Kahlo. She was a middle child of four, and she spent her childhood in Coyoacán, Mexico City in la Casa Azul, the Blue House. Though she was born in Mexico and stands today as a pioneer of Mexican folk art, Kahlo was actually ethnically half-European. “Frieda” was the original Hungarian spelling of her name, but she came to use the Spanish spelling, “Frida” furthering her carefully crafted persona. Her father, Wilhelm— he only later changed his name to Guillermo— was Hungarian, and her mother, Matilde was of Spanish, and indigenous, descent.

This work stands out among the rest of Kahlo’s collection for its references to European art and a European standard of beauty. The woman portrayed here is only a version of the artist. Her hand is placed delicately on her arm; her white neck, elongated. The piece conjures images of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in the subject’s knowing smile and Van Gogh’s Starry Night with the rolling waves in the background. These works in and of themselves were fitting inspirations, as both were, at their debuts, ill-received, misunderstood and wholly under-appreciated. At the time, critics questioned Mona Lisa’s smile, and scoffed at Van Gogh’s celestial cityscapes. Kahlo herself never saw much recognition in her lifetime, as she spent most of her career being tied to another artist, her husband, Diego Rivera.

The audience could interpret this use of the European style as a nod to the well-respected European greats like Da Vinci and Van Gogh, or one could interpret this as Kahlo’s attempt to thumb her nose at these painters. Take the exaggerated features of this work; one could suppose that the woman’s neck is too stretched, her tempting dress to too red, the cut of it too low. Consider these features, and this here Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress becomes a caricature-Kahlo and is no longer the genuine artifact.

This mockery is Kahlo’s rejection of the European standard, a rejection of the culture, and it acts as the artist’s way of further embracing her Mexican culture and identity. It would not be too hard to imagine, given that the artist was a notorious firecracker , a rebel and a patriot to the very end. “I was born a bitch,” she was once quoted for saying, “I was born a painter.”

With this piece, Frida Kahlo bucked tradition using a subtly that only skilled artists possess. Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress draws the audience in with its unintimidating size, holds them in a vice grip and fascinates them with its beauty. But, in truth, Kahlo was painting more than just a pretty picture. Kahlo’s Velvet offers a shining example of her own talent and versatility while never abandoning her signature style. Chiefly, it demonstrates the artist’s complexity and her ability to critically examine her cultural identity and herself, as only she could.

Works Cited

- “Frida Kahlo Biography.” Frida Kahlo Biography . N.p., 2015. Web. 16 July 2015.

- “Frida Kahlo Biography.” Bio.com . A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 17 July 2015.

- “Frida Kahlo: Her Photos.” 9788492480753: . Editorial RM, n.d. Web. 17 July 2015

- Search for:

Recent Comments

- No categories

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- All comments

COMMENTS

Frida Kahlo (born July 6, 1907, Coyoacán, Mexico—died July 13, 1954, Coyoacán) was a Mexican painter best known for her uncompromising and brilliantly colored self-portraits that deal with such themes as identity, the human body, and death.Although she denied the connection, she is often identified as a Surrealist.In addition to her work, Kahlo was known for her tumultuous relationship ...

Frida Kahlo Essay. Frida Kahlo was a female Mexican painter of mixed heritage, born on July 6, 1907 and lived 47 painful years before passing away on July 13, 1954. Within her short life, Frida was slightly crippled from polio, suffered from a serious streetcar accident that left her infertile, married famous muralist Diego Rivera, divorced ...

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940, oil on canvas, 40 x 27.9 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City) Kahlo was famously known for her tumultuous marriage with Rivera, whom she wed in 1929 and remarried in 1941. The daughter of a German immigrant (of Hungarian descent) and a Mexican mother, Kahlo ...

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website. If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

Introduction. Although Frida Kahlo (b. 1907-d. 1954) is one of the world's most widely recognized artists, that attention is often focused more on her dramatic life story than on the complexity of her intellect and artistic production. She is known for her self-portraits, which may appear straightforward and narrative, but throughout her ...

Writing essays on Frida Kahlo offers a rich opportunity for critical thinking and personal exploration. By delving into the life and work of this iconic artist, students can gain valuable insights into the complexities of identity, representation, and artistic expression. ... Introduction Pablo Picasso and Frida Kahlo are two of the most iconic ...

Introduction. Frida Kahlo was a famous artist and master of surrealism, born in 1907 in Mexico. The Mexican artist's extraordinarily lively and vivid biography is a fascinating story of rebellious art, romantic beliefs, eccentric love affairs, and endless physical suffering. After Kahlo's death, not only canvases remained, but also burning ...

Introduction of the essay. This essay will focus on the work of Frida Kahlo, a Mexican female artist. This analysis aims to reveal the personal characteristics of the artist, by examining Kahlo's choice of subject matter and investigating what drives her to create art that is so bold and defiant. To further the analysis it will look into to the ...

Kahlo's life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida, starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy ...

Frida Kahlo's honest, often bizarre, self-portraits reflect a beauty beyond the physical- an impishness in the wide eyes, a small smirk teasing at the corners of her mouth. In her renderings, her cheeks are always heavily rouged, and exotic flowers adorn her raven hair. Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress uses the contrast of light — Kahlo ...