- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

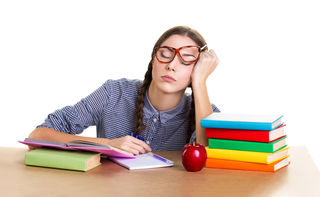

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

When Is Homework Stressful? Its Effects on Students’ Mental Health

Are you wondering when is homework stressful? Well, homework is a vital constituent in keeping students attentive to the course covered in a class. By applying the lessons, students learned in class, they can gain a mastery of the material by reflecting on it in greater detail and applying what they learned through homework.

However, students get advantages from homework, as it improves soft skills like organisation and time management which are important after high school. However, the additional work usually causes anxiety for both the parents and the child. As their load of homework accumulates, some students may find themselves growing more and more bored.

Students may take assistance online and ask someone to do my online homework . As there are many platforms available for the students such as Chegg, Scholarly Help, and Quizlet offering academic services that can assist students in completing their homework on time.

Negative impact of homework

There are the following reasons why is homework stressful and leads to depression for students and affect their mental health. As they work hard on their assignments for alarmingly long periods, students’ mental health is repeatedly put at risk. Here are some serious arguments against too much homework.

No uniqueness

Homework should be intended to encourage children to express themselves more creatively. Teachers must assign kids intriguing assignments that highlight their uniqueness. similar to writing an essay on a topic they enjoy.

Moreover, the key is encouraging the child instead of criticizing him for writing a poor essay so that he can express himself more creatively.

Lack of sleep

One of the most prevalent adverse effects of schoolwork is lack of sleep. The average student only gets about 5 hours of sleep per night since they stay up late to complete their homework, even though the body needs at least 7 hours of sleep every day. Lack of sleep has an impact on both mental and physical health.

No pleasure

Students learn more effectively while they are having fun. They typically learn things more quickly when their minds are not clouded by fear. However, the fear factor that most teachers introduce into homework causes kids to turn to unethical means of completing their assignments.

Excessive homework

The lack of coordination between teachers in the existing educational system is a concern. As a result, teachers frequently end up assigning children far more work than they can handle. In such circumstances, children turn to cheat on their schoolwork by either copying their friends’ work or using online resources that assist with homework.

Anxiety level

Homework stress can increase anxiety levels and that could hurt the blood pressure norms in young people . Do you know? Around 3.5% of young people in the USA have high blood pressure. So why is homework stressful for children when homework is meant to be enjoyable and something they look forward to doing? It is simple to reject this claim by asserting that schoolwork is never enjoyable, yet with some careful consideration and preparation, homework may become pleasurable.

No time for personal matters

Students that have an excessive amount of homework miss out on personal time. They can’t get enough enjoyment. There is little time left over for hobbies, interpersonal interaction with colleagues, and other activities.

However, many students dislike doing their assignments since they don’t have enough time. As they grow to detest it, they can stop learning. In any case, it has a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Children are no different than everyone else in need of a break. Weekends with no homework should be considered by schools so that kids have time to unwind and prepare for the coming week. Without a break, doing homework all week long might be stressful.

How do parents help kids with homework?

Encouraging children’s well-being and health begins with parents being involved in their children’s lives. By taking part in their homework routine, you can see any issues your child may be having and offer them the necessary support.

Set up a routine

Your student will develop and maintain good study habits if you have a clear and organized homework regimen. If there is still a lot of schoolwork to finish, try putting a time limit. Students must obtain regular, good sleep every single night.

Observe carefully

The student is ultimately responsible for their homework. Because of this, parents should only focus on ensuring that their children are on track with their assignments and leave it to the teacher to determine what skills the students have and have not learned in class.

Listen to your child

One of the nicest things a parent can do for their kids is to ask open-ended questions and listen to their responses. Many kids are reluctant to acknowledge they are struggling with their homework because they fear being labelled as failures or lazy if they do.

However, every parent wants their child to succeed to the best of their ability, but it’s crucial to be prepared to ease the pressure if your child starts to show signs of being overburdened with homework.

Talk to your teachers

Also, make sure to contact the teacher with any problems regarding your homework by phone or email. Additionally, it demonstrates to your student that you and their teacher are working together to further their education.

Homework with friends

If you are still thinking is homework stressful then It’s better to do homework with buddies because it gives them these advantages. Their stress is reduced by collaborating, interacting, and sharing with peers.

Additionally, students are more relaxed when they work on homework with pals. It makes even having too much homework manageable by ensuring they receive the support they require when working on the assignment. Additionally, it improves their communication abilities.

However, doing homework with friends guarantees that one learns how to communicate well and express themselves.

Review homework plan

Create a schedule for finishing schoolwork on time with your child. Every few weeks, review the strategy and make any necessary adjustments. Gratefully, more schools are making an effort to control the quantity of homework assigned to children to lessen the stress this produces.

Bottom line

Finally, be aware that homework-related stress is fairly prevalent and is likely to occasionally affect you or your student. Sometimes all you or your kid needs to calm down and get back on track is a brief moment of comfort. So if you are a student and wondering if is homework stressful then you must go through this blog.

While homework is a crucial component of a student’s education, when kids are overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to perform, the advantages of homework can be lost and grades can suffer. Finding a balance that ensures students understand the material covered in class without becoming overburdened is therefore essential.

Zuella Montemayor did her degree in psychology at the University of Toronto. She is interested in mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- Healing with Heart: Monica Patino’s Mission in Support of Latinx Families

- A Visit From the 49ers Scores Smiles at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford

- Beat the Heat: Keep Kids Safe in the Autumn Sun

- Wildfires: Health Risks and How to Keep Children Safe

- Cause for Celebration—and Concern

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford School of Medicine

- Stanford Health Care

- Stanford University

- How It Works

- Sleep Meditation

- VA Workers and Veterans

- How It Works 01

- Sleep Meditation 02

- Mental Fitness 03

- Neurofeedback 04

- Healium for Business 05

- VA Workers and Veterans 06

- Sports Meditation 07

- VR Experiences 08

- Social Purpose 11

Does Homework Cause Stress? Exploring the Impact on Students’ Mental Health

How much homework is too much?

Homework has become a matter of concern for educators, parents, and researchers due to its potential effects on students’ stress levels. It’s no secret students often find themselves grappling with high levels of stress and anxiety throughout their academic careers, so understanding the extent to which homework affects those stress levels is important.

By delving into the latest research and understanding the underlying factors at play, we hope to curate insights for educators, parents, and students who are wondering whether homework causing stress in their lives?

The Link Between Homework and Stress: What the Research Says

Over the years, numerous studies investigated the relationship between homework and stress levels in students.

One study published in the Journal of Experimental Education found that students who reported spending more than two hours per night on homework experienced higher stress levels and physical health issues . Those same students reported over three hours of homework a night on average.

This study, conducted by Stanford lecturer Denise Pope, has been heavily cited throughout the years, with WebMD producing the below video on the topic– part of their special report series on teens and stress :

Additional studies published by Sleep Health Journal found that long hours on homework on may be a risk factor for depression , suggesting that reducing workload outside of class may benefit sleep and mental fitness .

Homework’s Potential Impact on Mental Health and Well-being

Homework-induced stress on students can involve both psychological and physiological side effects.

1. Potential Psychological Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Anxiety: The pressure to perform well academically and meet homework expectations can lead to heightened levels of anxiety in students. Constant worry about completing assignments on time and achieving high grades can be overwhelming.

• Sleep Disturbances : Homework-related stress can disrupt students’ sleep patterns, leading to sleep anxiety or sleep deprivation, both of which can negatively impact cognitive function and emotional regulation.

• Reduced Motivation: Excessive homework demands could drain students’ motivation, causing them to feel fatigued and disengaged from their studies. Reduced motivation may lead to a lack of interest in learning, hindering students’ overall academic performance.

2. Potential Physiological Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Impaired Immune Function: Prolonged stress could weaken the immune system, making students more susceptible to illnesses and infections.

• Disrupted Hormonal Balance : The body’s stress response triggers the release of hormones like cortisol, which, when chronically elevated due to stress, can disrupt the delicate hormonal balance and lead to various health issues.

• Gastrointestinal Disturbances: Stress has been known to affect the gastrointestinal system, leading to symptoms such as stomachaches, nausea, and other digestive problems.

• Cardiovascular Impact: The increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure associated with stress can strain the cardiovascular system, potentially increasing the risk of heart-related issues in the long run.

• Brain impact: Prolonged exposure to stress hormones may impact the brain’s functioning , affecting memory, concentration, and other cognitive abilities.

The Benefits of Homework

It’s important to note that homework also offers many benefits that contribute to students’ academic growth and development, such as:

• Development of Time Management Skills: Completing homework within specified deadlines encourages students to manage their time efficiently. This valuable skill extends beyond academics and becomes essential in various aspects of life.

• Preparation for Future Challenges : Homework helps prepare students for future academic challenges and responsibilities. It fosters a sense of discipline and responsibility, qualities that are crucial for success in higher education and professional life.

• Enhanced Problem-Solving Abilities: Homework often presents students with challenging problems to solve. Tackling these problems independently nurtures critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

While homework can foster discipline, time management, and self-directed learning, the middle ground may be to strike a balance that promotes both academic growth and mental well-being .

How Much Homework Should Teachers Assign?

As a general guideline, educators suggest assigning a workload that allows students to grasp concepts effectively without overwhelming them . Quality over quantity is key, ensuring that homework assignments are purposeful, relevant, and targeted towards specific objectives.

Advice for Students: How to balance Homework and Well-being

Finding a balance between academic responsibilities and well-being is crucial for students. Here are some practical tips and techniques to help manage homework-related stress and foster a healthier approach to learning:

• Effective Time Management : Encourage students to create a structured study schedule that allocates sufficient time for homework, breaks, and other activities. Prioritizing tasks and setting realistic goals can prevent last-minute rushes and reduce the feeling of being overwhelmed.

• Break Tasks into Smaller Chunks : Large assignments can be daunting and may contribute to stress. Students should break such tasks into smaller, manageable parts. This approach not only makes the workload seem less intimidating but also provides a sense of accomplishment as each section is completed.

• Find a Distraction-Free Zone : Establish a designated study area that is free from distractions like smartphones, television, or social media. This setting will improve focus and productivity, reducing time needed to complete homework.

• Be Active : Regular exercise is known to reduce stress and enhance mood. Encourage students to incorporate physical activity into their daily routine, whether it’s going for a walk, playing a sport, or doing yoga.

• Practice Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques : Encourage students to engage in mindfulness practices, such as deep breathing exercises or meditation, to alleviate stress and improve concentration. Taking short breaks to relax and clear the mind can enhance overall well-being and cognitive performance.

• Seek Support : Teachers, parents, and school counselors play an essential role in supporting students. Create an open and supportive environment where students feel comfortable expressing their concerns and seeking help when needed.

How Healium is Helping in Schools

Stress is caused by so many factors and not just the amount of work students are taking home. Our company created a virtual reality stress management solution… a mental fitness tool called “Healium” that’s teaching students how to learn to self-regulate their stress and downshift in a drugless way. Schools implementing Healium have seen improvements from supporting dysregulated students and ADHD challenges to empowering students with body awareness and learning to self-regulate stress . Here’s one of their stories.

By providing students with the tools they need to self-manage stress and anxiety, we represent a forward-looking approach to education that prioritizes the holistic development of every student.

To learn more about how Healium works, watch the video below.

About the Author

Sarah Hill , a former interactive TV news journalist at NBC, ABC, and CBS affiliates in Missouri, gained recognition for pioneering interactive news broadcasting using Google Hangouts. She is now the CEO of Healium, the world’s first biometrically powered immersive media channel, helping those with stress, anxiety, insomnia, and other struggles through biofeedback storytelling. With patents, clinical validation, and over seven million views, she has reshaped the landscape of immersive media.

- For Authors

- Collaboration

- Privacy Policy

- Conferences & Symposiums

Tools & Methods

How does homework affect students.

Posted by Kenny Gill

Homework is essential in the learning process of all students. It benefits them in managing time, being organized, and thinking beyond the classroom work. When students develop good habits towards homework, they enjoy good grades. The amount of homework given to students has risen by 51 percent. In most cases, this pushes them to order for custom essays online. A lot of homework can be overwhelming, affecting students in negative ways.

How homework affects the psyche of students Homework plays a crucial role in ensuring students succeeds both inside and outside the classroom. The numerous hours they spend in class, on school work, and away from family and friends lead to them experiencing exhaustion. Too much homework leads to students becoming disheartened by the school, and it chips away at their motivation for succeeding.

As a result, homework becomes an uphill battle, which they feel they will never win despite putting an effort. When they continue to find homework difficult, they consider other ways of working on it, such as cheating.

Getting enough time to relax, engage with friends and family members helps the students to have fun, thus, raising their spirit and their psyche on school work. However, when homework exceeds, it affects their emotional well-being making them sad and unproductive students who would rather cheat their way through school.

As a result, they have to struggle with a lack of enough sleep, loss of weight, stomach problems, headaches, and fatigue. Poor eating habits where students rely on fast foods also occasions as they struggle to complete all their assignments. When combined with lack of physical activity, the students suffer from obesity and other health-related conditions. Also, they experience depression and anxiety. The pressure to attend all classes, finish the much homework, as well as have time to make social connections cripples them.

How can parents help with homework? Being an active parent in the life of your child goes a long way towards promoting the health and well-being of children. Participating in their process of doing homework helps you identify if your child is facing challenges, and provide the much-needed support.

The first step is identifying the problem your child has by establishing whether their homework is too much. In elementary school, students should not spend over twenty minutes on homework while in high school they should spend an average of two hours. If it exceeds these guidelines, then you know that the homework is too much and you need to talk with the teachers.

The other step is ensuring your child focuses on their work by eliminating distractions. Texting with friends, watching videos, and playing video games can distract your child. Next, help them create a homework routine by having a designated area for studying and organizing their time for each activity.

Why it is better to do homework with friends Extracurricular activities such as sports and volunteer work that students engage in are vital. The events allow them to refresh their minds, catch up, and share with friends, and sharpen their communication skills. Homework is better done with friends as it helps them get these benefits. Through working together, interacting, and sharing with friends, their stress reduces.

Working on assignments with friends relaxes the students. It ensures they have the help they need when tackling the work, making even too much homework bearable. Also, it develops their communication skills. Deterioration of communication skills is a prominent reason as to why homework is bad. Too much of it keeps one away from classmates and friends, making it difficult for one to communicate with other people.

Working on homework with friends, however, ensures one learns how to express themselves and solve issues, making one an excellent communicator.

How does a lot of homework affect students’ performance? Burnout is a negative effect of homework. After spending the entire day learning, having to spend more hours doing too much homework lead to burnout. When it occurs, students begin dragging their feet when it comes to working on assignments and in some cases, fail to complete them. Therefore, they end up getting poor grades, which affects their overall performance.

Excessive homework also overshadows active learning, which is essential in the learning process. It encourages active participation of students in analyzing and applying what they learn in class in the real world. As a result, this limits the involvement of parents in the process of learning and children collaboration with friends. Instead, it causes boredom, difficulties for the students to work alongside others, and lack of skills in solving problems.

Should students have homework? Well, this is the question many parents and students ask when they consider these adverse effects of homework. Homework is vital in the learning process of any student. However, in most cases, it has crossed the line from being a tool for learning and becomes a source of suffering for students. With such effects, a balance is necessary to help students learn, remain healthy, and be all rounded individuals in society.

Related Articles:

One Response to How does homework affect students?

Great info and really valuable for teachers and tutors. This is a really very wonderful post. I really appreciate it; this post is very helpful for education.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Top Keywords

Diabetes | Alzheimer’s disease Cancer | Breast cancer | Tumor Blood pressure | Heart Brain | Kidney | Liver | Lung Stress | Pain | Therapy Infection | Inflammation | Injury DNA | RNA | Receptor | Nanoparticles Bacteria | Virus | Plant

See more …

Proofread or Perish: Editing your scientific writing for successful publication

Lab Leader makes software applications for experiment design in life science

Cyagen Biosciences – Helping you choose the right animal model for your research

Labcollector lims and eln for improving productivity in the lab.

Image Cytometer – NucleoCounter® NC-3000™

Recent posts.

- Is multiple sclerosis triggered by immunological cross-recognition between an ancient virus and brain cell proteins?

- UCLA researchers develop high-sensitivity paper-based sensor for rapid cardiac diagnostics

- Unlocking new treatments for bone diseases: using PEPITEM to strengthen bones and prevent loss

- The Manikin Challenge: manikin-based simulation in the psychiatry clerkship

- Does UV-B radiation modify gene expression?

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

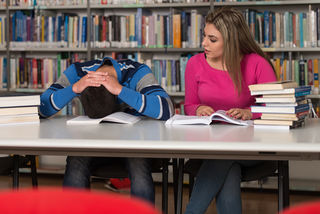

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

The Baker Orange

Screen-time and its effects on student’s mental health

How many hours of screen-time does the average college student rack up in a day? From laptops to smartphones to tablets, the average amount of screen-time for college students is more than an average day of school for grades K-12. Over 8 hours a day are devoted to social media, online homework and other personal uses for many students all across the country.

For Baker students specifically, managing their screen-time usage can be challenging.

Sutton Dye is a freshman and says that “I definitely know I’m on my devices more than I should be. I’d say I’m on my phone more mainly because it’s always with me wherever I go.”

He notes that with the start of the school year and practices after classes, his amount of screen-time has gotten better.

Sophomore Kate Gifford explained that using screens can take away from other things she enjoys.

“I feel trapped in a hole of scrolling, when I could be outside or reading the Bible,” Gifford said.

Screen time can take away from hobbies and activities and it can be difficult to switch off social media or other online platforms.

Most social media platforms are designed to be addictive and more engaging than homework or emails. This is why so many students have trouble with turning off social media specifically. As these platforms become more accessible and engaging, they can have a bigger influence in the lives of many students.

After so much time is dedicated to using a screen, lots of students start to notice a decline in their mental health. Heavy screen usage overtime can lead to feelings of isolation, anxiety, tiredness, insomnia, body dysmorphia and depression. There are many strategies out there to combat these feelings even though they may feel challenging to overcome.

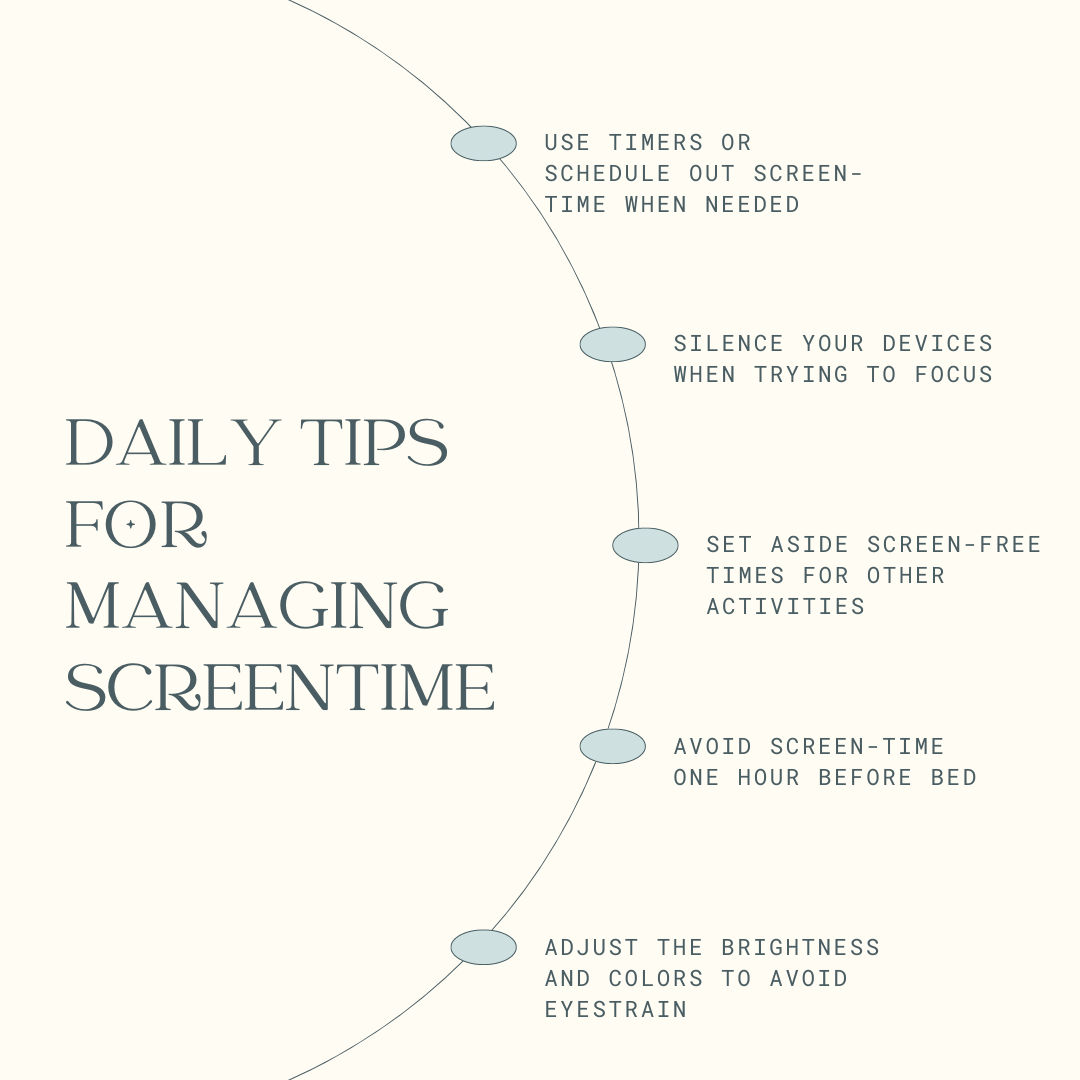

Limiting screen time is probably the most effective way to reduce anxiety and even procrastination. Another strategy can be to schedule when to use certain apps or programs so that less time is spent on unrelated activities. Silencing devices can be helpful when trying to focus.

Participating in screen-free activities like exercise, meditation or just hanging out with friends can be great mood-boosters. Going to on-campus events or joining a club can also help.

To get better sleep, try to avoid looking at a screen before bed for at least one hour. Or if homework sessions late at night are more the style, lower the brightness and adjust the colors to more yellow hues to get a less harsh effect and to avoid eye strain.

For more help, the Baker Student Counseling Center is open Monday through Friday and offers different solutions. There are also numerous online resources that are available 24/7. Screen-time is just one of the many things college students have on their plates and it is worthwhile knowing that there are ways to improve and feel more positive.

- Baker student life

- screen time

Opinion | Social-Emotional Learning

If we’re serious about student well-being, we must change the systems students learn in, here are five steps high schools can take to support students' mental health., by tim klein and belle liang oct 14, 2022.

Shutterstock / SvetaZi

This article is part of the collection: Making Sense of K-12 Student Mental Health.

Educators and parents started this school year with bated breath. Last year’s stress led to record levels of teacher burnout and mental health challenges for students.

Even before the pandemic, a mental health crisis among high schoolers loomed. According to a survey administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019, 37 percent of high school students said they experienced persistent sadness or hopelessness and 19 percent reported suicidality. In response, more than half of all U.S. states mandated that schools have a mental health curriculum or include mental health in their standards .

As mental health professionals and co-authors of a book about the pressure and stress facing high school students, we’ve spent our entire careers supporting students’ mental health. Traditionally, mental health interventions are individualized and they focus on helping students manage and change their behaviors to cope with challenges they’re facing. But while working with schools and colleges across the globe as we conducted research for our book , we realized that most interventions don’t address systemic issues causing mental health problems in the first place.

It’s time we acknowledge that our education systems are directly contributing to the youth mental health crisis. And if we are serious about student well-being, we must change the systems they learn in.

Here are five bold steps that high schools can take to boost mental health.

Limit Homework or Make it Optional

Imagine applying for a job, and the hiring manager informs you that in addition to a full workday in the office, you’ll be assigned three more hours of work every night. Does this sound like a healthy work-life balance? Most adults would consider this expectation ridiculous and unsustainable. Yet, this is the workload most schools place on high school students.

Research shows that excessive homework leads to increased stress, physical health problems and a lack of balance in students' lives. And studies have shown that more than two hours of daily homework can be counterproductive , yet many teachers assign more.

Homework proponents argue that homework improves academic performance. Indeed, a meta-analysis of research on this issue found a correlation between homework and achievement. But correlation isn’t causation. Does homework cause achievement or do high achievers do more homework? While it’s likely that homework completion signals student engagement, which in turn leads to academic achievement, there’s little evidence to suggest that homework itself improves engagement in learning.

Another common argument is that homework helps students develop skills related to problem-solving, time-management and self-direction. But these skills can be explicitly taught during the school day rather than after school.

Limiting homework or moving to an optional homework policy not only supports student well-being, but it can also create a more equitable learning environment. According to the American Psychological Association, students from more affluent families are more likely to have access to resources such as devices, internet, dedicated work space and the support necessary to complete their work successfully—and homework can highlight those inequities .

Whether a school limits homework or makes it optional, it’s critical to remember that more important than the amount of homework assigned, is designing the type of activities that engage students in learning. When students are intrinsically motivated to do their homework, they are more engaged in the work, which in turn is associated with academic achievement.

Cap the Number of APs Students Can Take

Advanced Placement courses give students a taste of college-level work and, in theory, allow them to earn college credits early. Getting good grades on AP exams is associated with higher GPAs in high school and success in college, but the research tends to be correlational rather than causational.

In 2008, a little over 180,000 students took three or more AP exams. By 2018, that number had ballooned to almost 350,000 students .

However, this expansion has come at the expense of student well-being.

Over the years, we’ve heard many students express that they feel pressure to take as many AP classes as possible, which overloads them with work. That’s troubling because studies show that students who take AP classes and exams are twice as likely to report adverse physical and emotional health .

AP courses and exams also raise complex issues of equity. In 2019, two out of three Harvard freshmen reported taking AP Calculus in high school, according to Jeff Selingo, author of “ Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions ,” yet only half of all high schools in the country offer the course. And opportunity gaps exist for advanced coursework such as AP courses and dual enrollment, with inequitable distribution of funding and support impacting which students are enrolling and experiencing success. According to the Center for American Progress, “National data from the Civil Rights Data Collection show that students who are Black, Indigenous, and other non-Black people of color (BIPOC) are not enrolled in AP courses at rates comparable to their white and Asian peers and experience less success when they are—and the analysis for this report finds this to be true even when they attend schools with similar levels of AP course availability.”

Limiting the number of AP courses students take can protect mental health and create a more equitable experience for students.

Eliminate Class Rankings

In a study we conducted about mental health problems among high school girls, we found that a primary driver of stress was their perception of school as a hypercompetitive, zero-sum game where pervasive peer pressure to perform reigns supreme.

Class rankings fuel these cutthroat environments. They send a toxic message to young people: success requires doing better than your peers.

Ranking systems help highly selective colleges decide which students to admit or reject for admission. The purpose of high school is to develop students to their own full potential, rather than causing them to fixate on measuring up to others. Research shows that ranking systems undercut students’ learning and damage social relationships by turning peers into opponents.

Eliminating class rankings sends a powerful message to students that they are more than a number.

Become an Admission Test Objector

COVID-19 ushered in the era of test-optional admissions. De-centering standardized tests in the college application process is unequivocally a good thing. Standardized tests don’t predict student success in college , they only widen the achievement gap between privileged and underprivileged students and damage students' mental health .

Going “test optional” is an excellent first step, but it's not enough.

Even as more colleges have made tests optional, affluent students submit test scores at a higher rate than their lower-income peers and are admitted at higher rates , suggesting that testing still gives them an edge.

High schools must adhere to standardized test mandates, but they don’t have to endorse them. They can become test objectors by publicly proclaiming that these tests hold no inherent value. They can stop teaching to the test and educate parents on why they are doing so. Counseling departments can inform colleges that their school is a test objector so admission teams won’t penalize students.

Of course, students and families will still find ways to wield these tests as a competitive advantage. Over time, the more schools and educators unite to denounce these tests, the less power they will hold over students and families.

Big change starts with small steps.

Stand For What You Value

Critics may argue that such policies might hurt student outcomes. How will colleges evaluate school rigor if we limit AP courses and homework? How will students demonstrate their merits without class rankings and standardized test scores?

The truth is, the best school systems in the world succeed without homework, standardized test scores or an obsession with rigorous courses. And many U.S. schools have found creative and empowering ways to showcase student merit beyond rankings and test scores.

If we aren’t willing to change policies and practices that have been shown to harm students’ well-being, we have to ask ourselves: Do we really value mental health?

Thankfully, it doesn’t have to be an either/or scenario: We can design school systems that help students thrive academically and psychologically.

Belle Liang and Tim Klein are mental health professionals and co-authors of “How To Navigate Life: The New Science of Finding Your Way in School, Career and Life.”

Making Sense of K-12 Student Mental Health

Tackling the Youth Mental Health Crisis Head-On

By aaliyah a. samuel.

Adolescents Need More Proactive, Preventative Mental Health Supports in School

By sara potler lahayne.

Coronavirus

Kids’ mental health is in crisis. schools can get them help through a $1 billion fund, by nadia tamez-robledo.

When Student Anxiety Gets in the Way of Attending School

By daniel mollenkamp, more from edsurge.

Phenomena-Based Learning and 3D Science: Inspiring Curiosity and Making Sense of the World

By steven smithwhite.

Teaching Feels Like a Dead-End Job. Here’s How Schools Can Change That.

By rachel herrera.

Education Workforce

How this district tech coach still makes time to teach — in a multi-sensory immersive room, by emily tate sullivan.

Teaching and Learning

How to make someone not hate math.

Journalism that ignites your curiosity about education.

EdSurge is an editorially independent project of and

- Write for us

- Advertising

FOLLOW EDSURGE

© 2024 All Rights Reserved

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Barriers Associated with the Implementation of Homework in Youth Mental Health Treatment and Potential Mobile Health Solutions

Brian e bunnell, lynne s nemeth, leslie a lenert, nikolaos kazantzis, esther deblinger, kristen a higgins, kenneth j ruggiero.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Brian Bunnell], [Lynne Nemeth], [Kenneth Ruggiero], and [Kristen Higgins]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Brian Bunnell] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Correspondence: Brian E. Bunnell, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, 3515 E. Fletcher Ave Tampa, FL 33613; Phone: (813) 794-8607; [email protected] .

Issue date 2021 Apr.

Background:

Homework, or between-session practice of skills learned during therapy, is integral to effective youth mental health TREATMENTS. However, homework is often under-utilized by providers and patients due to many barriers, which might be mitigated via m Health solutions.

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with nationally certified trainers in Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT; n =21) and youth TF-CBT patients ages 8–17 ( n =15) and their caregivers ( n =12) to examine barriers to the successful implementation of homework in youth mental health treatment and potential m Health solutions to those barriers.

The results indicated that many providers struggle to consistently develop, assign, and assess homework exercises with their patients. Patients are often difficult to engage and either avoid or have difficulty remembering to practice exercises, especially given their busy/chaotic home lives. Trainers and families had positive views and useful suggestions for m Health solutions to these barriers in terms of functionality (e.g., reminders, tracking, pre-made homework exercises, rewards) and user interface (e.g., easy navigation, clear instructions, engaging activities).

Conclusions:

This study adds to the literature on homework barriers and potential m Health solutions to those barriers, which is largely based on recommendations from experts in the field. The results aligned well with this literature, providing additional support for existing recommendations, particularly as they relate to treatment with youth and caregivers.

Keywords: Homework, Barriers, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Technology, m Health

Introduction

Homework, or between-session practice of skills learned during therapy, is one of the most integral, yet underutilized components of high-quality, evidence-based mental health care ( Kazantzis & Deane, 1999 ). Homework activities (e.g., self-monitoring, relaxation, exposure, parent behavior management) are assigned by providers in-session and completed by patients between sessions with the goal of “practicing” therapeutic skills in the environment where they will be most needed ( Kazantzis, Deane, Ronan, & L’Abate, 2005 ). There are numerous benefits to the implementation of homework during mental health treatment ( Kazantzis et al., 2016 ; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2004 ). Homework enables the generalization of skills and behaviors learned during therapy, facilitates treatment processes, provides continuity between sessions, allows providers to better grasp patients’ learning, and strengthens that learning, leading to improved maintenance of treatment gains ( Hudson & Kendall, 2002 ; Scheel, Hanson, & Razzhavaikina, 2004 ). Meta-analytic and systematic reviews have shown that homework use by providers and adherence by patients predict increased treatment engagement, decreased treatment dropout, and medium-to-large effects on improvements in clinical outcomes for use (Cohen’s d =.48–.77) and adherence ( d =.45–.54) ( Hudson & Kendall, 2002 ; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000 ; Kazantzis & Lampropoulos, 2002 ; Kazantzis, Whittington, & Dattilio, 2010 ; Mausbach, Moore, Roesch, Cardenas, & Patterson, 2010 ; Scheel et al., 2004 ; Sukhodolsky, Kassinove, & Gorman, 2004 ). Simply put, 68% vs . 32% of patients can be expected to improve when therapy involves homework ( Kazantzis et al., 2010 ).

Despite its many benefits, homework is implemented with variable effectiveness in mental health treatment. Only 68% of general mental health providers and ~55% of family providers report using homework “often” to “almost always” ( Dattilio, Kazantzis, Shinkfield, & Carr, 2011 ; Kazantzis, Lampropoulos, & Deane, 2005 ). Further, providers report using homework in an average of 57% of sessions, although this rate is higher for CBT practitioners (66%) vs . non-CBT practitioners (48%). Moreover, only 25% of providers report using expert recommended systematic procedures for recommending homework (i.e., specifying frequency, duration, and location; writing down homework assignments for patients) ( Kazantzis & Deane, 1999 ). A national survey revealed that 93% or general mental health providers estimate rates of patient adherence to homework to be low to moderate ( Kazantzis, Lampropoulos, et al., 2005 ), and research studies report low to moderate rates of youth/caregiver adherence during treatment (i.e., ~39–63%; ( Berkovits, O’Brien, Carter, & Eyberg, 2010 ; Clarke et al., 1992 ; Danko, Brown, Van Schoick, & Budd, 2016 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Gaynor, Lawrence, & Nelson-Gray, 2006 ; Helbig & Fehm, 2004 ; Lyon & Budd, 2010 ; Simons et al., 2012 ).

Numerous barriers to the successful implementation of homework during mental health treatment have largely been suggested by experts in the field, rather than specifically measured ( Dattilio et al., 2011 ), and have generally been classified as occurring on the provider-, patient-, task-, and environmental-level ( Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Provider-level barriers can relate to the therapeutic relationship and the degree to which a collaborative approach is used, provider beliefs about homework and the patient’s adherence, and providers’ ability to effectively design homework tasks ( Callan et al., 2012 ; Coon, Rabinowitz, Thompson, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2005 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Patient-level barriers can include patient avoidance and symptomatology, negative beliefs toward the task, not understanding the rationale or how to do the task, forgetting, and beliefs about their ability to complete homework tasks. ( Bru, Solholm, & Idsoe, 2013 ; Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ; Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ; Leahy, 2002 ). Relatedly, core beliefs central to the patients’ psychopathology can be activated during homework–thereby triggering withdrawal and avoidance patterns ( Kazantzis & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Task-level barriers include poor match between tasks and therapy goals, tasks that are perceived as vague or unclear, tasks that are perceived as too difficult or demanding in terms of time or effort, tasks being viewed as boring, and general aversiveness of the idea of completing homework ( Bru et al., 2013 ; Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Friedberg & Mcclure, 2005 ; Garland & Scott, 2002 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ). Environmental factors have been noted to include practical obstacles, lack of family/caregiver support, dysfunctional home environments, lack of time due to busy schedules, and lack of reward or reinforcement ( Callan et al., 2012 ; Dattilio et al., 2011 ; Hudson & Kendall, 2005 ).

The advancement and ubiquitousness of technologies such as m Health resources (e.g., mobile- and web-based apps) provide a tremendous opportunity to overcome barriers to homework use and adherence and resultantly, improve the quality of mental health treatment. m Health solutions to improve access and quality of care, have been widely investigated, are effective in facilitating behavior change, practical, desired by patients and providers, and available at low cost ( Amstadter, Broman-Fulks, Zinzow, Ruggiero, & Cercone, 2009 ; Boschen & Casey, 2008 ; Donker et al., 2013 ; Ehrenreich, Righter, Rocke, Dixon, & Himelhoch, 2011 ; Hanson et al., 2014 ; Heron & Smyth, 2010 ; Krebs & Duncan, 2015 ; Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, 2011 ; Ruggiero, Saunders, Davidson, Cook, & Hanson, 2017 ). Existing m Health resources include features that can support homework implementation (e.g., voice and SMS reminders and feedback, self-monitoring and assessment, and modules and activities that can be used to facilitate between-session practice; Bakker, Kazantzis, Rickwood, & Rickard, 2016 ; Tang & Kreindler, 2017 ), but these resources were not designed with the express intention of addressing barriers to homework implementation, particularly for youth and family patient populations.

The extant literature on barriers to homework implementation is limited in that it is largely based on expert recommendations. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to explore provider, youth, and caregiver patient perspectives on barriers to the successful implementation of homework during youth mental health treatment. Further, m Health solutions to those barriers have not been explored, especially for youth and family patients. Thus, the second and third aims of this study were to obtain suggestions for m Health solutions to homework barriers and explore perceptions on the benefits and challenges associated with those m Health solutions.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to enrolling any participants in the study. The approach for this study was based on the constructivist grounded theory, which acknowledges the researcher’s prior knowledge and influence in the process and supports and guides conceptual framework development to understand interrelations between constructs ( Charmaz, 2006 ). This qualitative study used a thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews in a sample of nationally certified trainers in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TFCBT; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2017 ), youth who had engaged in TF-CBT, and their caregivers. The initial goal was to conduct interviews with 15–20 interviewees in each group to achieve theoretical saturation (i.e., no new information was derived), consistent with a prior study by members of the research team which used similar semi-structured interviews with national TF-CBT trainers ( Hanson et al., 2014 ), and recommendations by Morse (2000) given the relatively narrow scope and clear nature of the study. Interviews were conducted until interviewers and the study lead determined that no new pertinent information was being obtained.

Participants

National trainers..

Twenty-one national trainers in TF-CBT were interviewed. National trainers are mental health providers who completed a 15-month TF-CBT Train-the-Trainer program led by the TF-CBT developers. Trainers work extensively with numerous community mental health providers to problem-solve common barriers to clinical practice and thus, provide a unique perspective on the barriers to successful homework implementation and possible m Health solutions to those barriers. An e-mail invitation was sent to a list of approved TF-CBT trainers. Twenty-four trainers responded to this e-mail, 22 of whom agreed to participate in an interview, one of whom was unreachable after initial scheduling. Interviews were completed with a total of 21 trainers, who received a $25 gift card in compensation for their time.

Trainers had been treating children for an average of 23.29 years ( SD =8.80) and had been training providers for an average of 14.95 years ( SD =8.98). In the year prior to the interview, they led an average of 17 provider trainings ( SD =21.67) and trained roughly 345 providers ( SD =339.90). All trainers were licensed, and the majority were Clinical Psychologists (47.6%) and Social Workers (33.3%). The average age of trainers was 47.48 years ( SD =13.63) and the majority were female (71.4%), white (95.2%), and non-Hispanic/Latino (85.7%; see Table 1 ).

Trainer Demographics

Twelve families were interviewed for this study. Families were included if they had one or more youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years-of-age and a caregiver who had engaged in at least four sessions for TF-CBT. These criteria were chosen because TF-CBT is typically recommended for youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years-of-age and it was estimated that four sessions would have likely allowed for adequate time for patients to have received homework assignments, consistent with the authors’ experience and prior TF-CBT literature ( Deblinger, Pollio, & Dorsey, 2016 ; Scheeringa, Weems, Cohen, Amaya-Jackson, & Guthrie, 2011 ). Families were recruited via advertisements online and at local community mental health clinics, and from a participant pool from a prior study ( Davidson et al., 2019 ). Twenty-nine families initially expressed interest in participating in the study. Six families were ineligible because they had not received TF-CBT and contact was lost with six families after their initial contact. Seventeen families were scheduled for an interview, five of which were unreachable after initially being scheduled, and interviews were completed with 12 families. Written informed consent from caregivers and assent from youth above the age of 15 were obtained in-person for four families and via a telemedicine-based teleconsent platform (i.e., https://musc.doxy.me ) for eight families. Families received a $30 gift card in compensation for their time.

A total of 15 youth who had engaged in TF-CBT, and their caregivers ( n =12; three families had two youth who had received treatment) were interviewed. Six youth were still in treatment at the time of their interview and nine had finished treatment an average of 49 weeks ( SD =42.32) prior to the interview. The average age of youth was 13.20 years ( SD =3.19), roughly half were female (53.3%), the majority were white (80%), and all were non-Hispanic/Latino. The average age of caregivers was 44.83 years ( SD =7.90), 66.7% were female, and all were White and non-Hispanic/Latino. Youth and caregivers rated their comfort with technology, in general, on a 10-point Likert scale (i.e., 1–10) with higher scores representing higher levels of comfort. Youth reported being very comfortable with technology (M=9.62, SD =1.12), as did their caregivers (M=7.83, SD =2.63; see Table 2 ).

Family Demographics

= 6 families were still in treatment at the time of their interview and were not included in this average.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

TF-CBT is a well-established and widely disseminated mental health treatment ( Cohen et al., 2017 ; Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer, 2011 ; Silverman et al., 2008 ; Wethington et al., 2008 ). It is a conjoint youth-caregiver mental health treatment typically conducted over ~12, 90-minute sessions that address nine major treatment components (i.e., P sychoeducation; P arenting Skills; R elaxation Skills; A ffective Expression and Modulation Skills; C ognitive Coping and Processing Skills; T rauma Narration and Processing; I n Vivo Exposure; C onjoint Child Parent Activities; and E nhancing Future Safety and Development). TF-CBT also addresses a broad range of symptom domains including trauma- and stress-related disorders, disruptive behavior disorders/behaviors, depression/depressive symptoms, and anxiety disorders ( Cohen et al., 2017 ). TF-CBT was chosen as a model treatment for this study because of its broad symptom focus, inclusion of treatment components used in a variety of youth mental health treatments, and involvement of youth and their caregivers, offering potential to improve the applicability of the study’s results to a range of youth mental health treatment approaches.

Procedures for Data Collection

Interviews were conducted via telephone for trainers, and either in-person or via telephone for families based on their preference. A postdoctoral fellow and masters-level research assistant conducted the interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed using a professional transcription service. Interviews included three major components. The first component included demographic questions. The second included a brief orientation to the goal of the study, which was to develop a new technology-based resource to help providers and patients during the implementation of homework during mental health treatment. The third component included questions that aimed to assess perspectives on barriers to homework implementation, elicit suggestions for m Health solutions to those barriers, and examine perceptions on the benefits and challenges associated with m Health solutions to homework barriers. The average duration of interviews was 41 minutes for trainers and 37 minutes for families. See Supplementary Materials for complete interviews.

Data Analysis

Transcribed interviews were coded using NVivo qualitative analysis software. NVivo was used to identify common themes (nodes) as they related to (1) patient-, provider-, task-, and environmental-barriers to homework implementation, (2) suggestions for m Health solutions to homework barriers, and (3) benefits and challenges associated with m Health homework solutions. Initial and secondary coding passes were conducted to identify and refine theme classifications as they emerged and impose a data-derived hierarchy to the nodes identified. Focused coding was used to refine the coding and ensure that data were coded completely with minimal redundancy ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). Themes were initially proposed by the first author and reviewed by an expert in qualitative and mixed methods research (the second author) and an internationally recognized expert in the implementation of homework and related barriers during CBT (the fourth author). Divergent perspectives on theme descriptions ( n =2) and classifications ( n =1) were compared until agreement was reached.

Results are organized by the main topics explored in this study, including: 1) barriers to the successful implementation of homework, coded on provider, patient, task, and environmental levels; 2) potential m Health solutions to those homework barriers; and 3) perceived benefits and challenges of those potential m Health solutions. Results within each of these topics are presented first from the perspectives of trainers and second from the perspectives of families.

Barriers to the Successful Implementation of Homework

Trainer perspectives..

As displayed in Table 3 , trainers identified several barriers to homework implementation on the provider-, patient-, task-, and environmental-level.

Trainer Perspectives on Homework Barriers

Provider-Level Barriers.

Many trainers felt that providers tend to have difficulty engaging patients in assigned tasks, leading some providers to become discouraged by low levels of engagement. As stated by one trainer,

“I think they recognize that [homework assignments] do have value, but in terms of what I feel, a lot of clinicians are not having success with families completing homework, so it’s diminishing the sense of value…something they’ve tried to put into place and they are not feeling there’s any success in it.”

Trainers also noted that many providers do not see homework as an integral part of therapy. One trainer commented,

“I think there are a lot of concrete barriers, but to me probably the biggest barrier will be the–I think that still to this day [providers] like to think that therapy happens in that one hour.”

Other interrelated difficulties faced by providers related to their capacity to effectively and consistently develop, assess, and assign meaningful and patient-centered homework exercises.

As stated by one trainer,

“I see a lot of that just shooting from the hip, kind of off the cuff, ‘let’s do this,’ but yet, it’s not backed by anything concrete or tangible…I think probably one of the biggest pieces again is the failure on the clinician’s part to follow that up and too often review it at the end of the session.”

Another said,

“I think clinicians don’t always appreciate how hard it is to actually do homework that requires you to make some behavioral change.”

Barriers also related to providers’ time and resources for implementing homework, as conveyed by one trainer’s comment,

“I mean, these people…every minute of every day is filled up with doing, billing, writing, charting, going to meetings, getting supervision, and seeing patients, and then they go home exhausted.”

Patient-Level Barriers.

Many trainers stated that, similar to some providers, patients often do not see homework as an important part of therapy. Put by one trainer,

“I think that some [patients] just feel that coming to the session is enough and that should resolve everything, and that you know, doing homework is just kind of an extra thing…I don’t really need to do it to benefit from the therapy.”

Perhaps relatedly, trainers also noted that patients generally forget to do homework assignments, and often forget why, how, when, and where assignments should be done.

Task-Level Barriers.

Task-level barriers noted by trainers included assignments not always aligning with patient values or treatment goals and that the term ‘homework’ being aversive to patients of all ages. One trainer commented,

“I think it has to be something that [patients] see the value in. And again, we go back to that engagement and them trusting you as well as you explaining to them why this could be helpful…If it didn’t help, we need to change it.”

Another trainer laughed while stating,

“when we use the word homework, we might as well just throw a stink bomb in the room.”

Environmental-Level Barriers.

Finally, on the environmental-level, many trainers suggested that patients’ home lives are busy and chaotic, leaving little-to-no time for homework.

Explained by one trainer,

“I think that for parents…they have many other things in their life; work, parenting, partnerships that they are working on, just day to day chores or things that they have to do in terms of their family or other responsibilities. So, [homework] often feels like, I think for families, to add another thing…it just feels like a lot.”

Associated barriers included limited caregiver involvement and reinforcement for completing homework assignments. One trainer commented,

“So, let’s not forget that the parents need to be encouraged and checked on to make sure the kid is doing it. They have to work at it – It’s not going to just happen. So, helping the parents to see that they’re going to need to work to make sure the kids do it, because again, the kids would rather eat ice-cream than do the work. I mean change is hard.”

Another stated,

“I would say, lack of reinforcement for homework, so maybe for getting what you assign for homework and not reviewing it or the kiddo or the family learning pretty quickly, you know, why do it, because there’s not a lot of support around it. You know, if [patients] don’t get reinforced, whether tangibly or verbally, they may not continue that.”

Family Perspectives.

Families identified several barriers to homework implementation on the patient-, task-, and environmental-level which were similar to many of those noted by national trainers (see Table 4 ).

Family Perspectives on Homework Barriers

Families believed that patients often avoid homework as a result of their symptoms. In other words, the patient’s unhelpful coping strategies are being triggered.

One caregiver commented,

“Sometimes people don’t even want to dig into their feelings even to do the assignment either, you know. It stirs up things. You know, when you’re dealing with feelings, sometimes you don’t want to experience that feeling…you shut down. You don’t want to feel that at that time.”

“When you already have a child that has ADHD or behavior problems, it’s hard to get them motivated and to get them to do these exercises at home.”

Families also felt that patients simply forget to complete homework or bring it to their next session. One child stated,

“That’s my problem, she’ll give me homework, we met once a week, basically, and I would forget it because I’ve got a lot going on, and when I come in and she’s like, ‘Did you do your homework,’ I’m like, ‘Oh man’.”

Similar to trainers, families felt that patients often forget why, how, when and where assignments should be done. As stated by one caregiver,

“I think sometimes it can also be just, like maybe not fully understanding what is being asked of them to do. I know the therapist will ask them in the office, ‘do you understand?’ and of course the kids always go, ‘yes I do, can I go home now’?”

With respect to task-level barriers, most families viewed homework assignments as boring. General consensus from families was that patients–particularly youth– would more often than not just rather be doing something more interesting.

On the environmental level, all families noted that the home-life of patients is busy and chaotic, leaving little perceived time for homework. Everyday responsibilities such as schoolwork, employment, household chores, and familial responsibilities often take precedence. One caregiver stated,

“Well I think it sounds good in the office and then you get home and you just get quite busy and it gets pushed aside.”

Another commented,

“But I know what he’s saying…sometimes seven-and-a-half hours at school and then sometimes his therapy would be an hour-and-a-half. And thank goodness, his teacher was so flexible that on days he has therapy he did not have homework [for school], but he was just so emotionally and physically drained. When he got home, all he wanted to do was just rest or play. Because that’s the therapy, it can be just exhausting.”

Families also believed that that there is often a lack of reinforcement for completing homework assignments.

m Health Solutions to Homework Barriers

Trainer suggestions..

Trainers provided several suggestions for m Health solutions to homework barriers ( Table 5 ). Most trainers felt that reminders and schedules to help patients remember to complete homework assignments would be a crucial feature. One trainer suggested, “Maybe some kind of reminder feature, something that would kind of record into their daily calendars that they use, or an alarm, or something like a daily reminder…set to the times they are most likely to do the homework.”

Trainer Suggestions for m Health Solutions to Homework Barriers

Trainers also suggested including reports or activity summaries of homework completion along with behavior and symptom tracking tools. One trainer thoughtfully commented, “If the homework app can somehow help to provide some data on the actual implementation of certain skills during the week that would be very valuable because I think the constructive feedback and the positive feedback that’s offered by therapists about performance of those skills between sessions can be really valuable.”

Trainers suggested including a variety of interactive, fun, and rewarding activities that engage children and caregivers. For example, one trainer stated,