My Get Up and Go Got Up and Went

- Posted May 10, 2021

- By Andrew Bauld

- Counseling and Mental Health

- Disruption and Crises

- Social Emotional Learning

- Student Achievement and Outcomes

- Teachers and Teaching

EVERYONE KNEW learning during a pandemic wouldn’t be easy, but could we have guessed it would be quite this hard?

Schools are still battling everything from poor internet service to low attendance. Parents are overwhelmed in homes that have also become workplaces and classrooms. Teachers are demoralized. And students are exhausted, burned out after hours of online classes, and that is if they even show up at all.

The result is students — and teachers — who have lost so much of what used to keep them motivated. Without the ballast of most extracurricular activities like athletics, drama, and band to keep them engaged, many students lost the motivation this year to turn in homework or turn on cameras during remote lessons. Teachers are burnt out, many discouraged by not keeping up with curriculum standards and constantly having to find new ways to keep their students invested in their learning.

Some schools have gone back, but with a return to “normal” school unlikely for many districts until the fall of 2021, teachers and students are having to find new ways to stay motivated to learn during a school year unlike any other.

The Science of Motivation

Abigail Williamson, Ed.M.’15, teaches English Language Development on Martha’s Vineyard. Her middle school students are brand new to the United States, working hard to learn a new language, many of them also taking care of younger siblings at home during remote learning while their parents are at work.

But for five minutes every day, students put aside the challenges they are facing and turn on their favorite song. Some students don sunglasses or fun hats, others grab stuffed animals to join them onscreen for their class DJ Dance Party.

“I wanted to give the kids jobs to keep them engaged and give them some ownership,” says Williamson. “The dance party offers some lightness and fun, but I believe also contributes to our strong attendance and participation.”

Especially during these stressful times, it is important for teachers to think about how students are doing not only academically but also emotionally, and to find ways to inject joy into their lessons.

Christina Hinton, Ed.M.’06, Ed.D.’12, founder and CEO of Research Schools International, which partners with schools to carry out collaborative research, says lessons like the DJ Dance Party can make a huge impact for students.

“There’s a misconception that learning can either be rigorous or fun. That’s not what we’re finding in our research,” Hinton says. “The more they are flourishing and happy, the better, on average, students are doing academically.”

Happy students are also motivated ones. Research has found that motivation is driven by a combination of a person’s earliest experiences and innate biological factors. According to a recent report from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, there are two types of motivation: one that seeks out pleasure (known as approach motivation) and the other that avoids danger (known as avoidance motivation).

Both of these types of motivation develop early in childhood, and both are influenced by intrinsic (like a child’s desire to explore or master a skill) and extrinsic factors (external validation from grades or awards). A healthy motivation system is one built on intrinsic drivers supported by positive extrinsic feedback.

For teachers and parents, there are many ways to encourage motivation. Activities like the DJ Dance Party that provide children space for playful exploration help fuel intrinsic motivation. Activities that appropriately challenge students are also great, but they must be carefully selected as students will lose motivation when an activity is too hard or too easy. Students are also more motivated when they feel a sense of ownership over their work.

These types of activities can also spur in students a sense of curiosity, another good driver of motivation. Ed School associate professor and cognitive research scientist Elizabeth Bonawitz says that curiosity is a core drive that all human beings are born with.

“It’s a drive like hunger or thirst, and it can get us learning very rapidly,” Bonawitz says. Under particularly stressful environments, however, say like during a global pandemic, the body must balance all its needs. “Do I have time to be curious or am I worried about my next meal, or if grandma is going to get sick? If you’re under a lot of duress, you don’t have time to indulge your curiosity,” so actively finding ways to encourage curiosity in the classroom is so important.

Williamson came up with the idea for the dance party at the beginning of this unusual school year, trying to think of ways to replicate traditional classroom management techniques for online learning. Some of her more hesitant learners were hooked from the beginning. Besides the opportunity to get up and move around, it also provided students a chance to show a bit about their personalities, connect over shared interests, and extend their learning, since the songs they choose have connections to the vocabulary they are learning.

Williamson says this break in the day has also given her a unique insight into her students. In her first year at a new school, Williamson says she was initially worried about building connections with students she had never met, but she says the same theories for building community when in-person apply to remote learning.

“Their creativity in activities like the dance party motivates me to find more ways to let them express their personalities,” Williamson says. “I ask students about their lives and listen and incorporate that into my lessons. You can have deep relationships with students even online.”

Find New Ways to Connect

Those relationships are a critical component of motivation. As Bonawtiz has found in her research, humans are social beings with minds designed to learn from other people. When students lose those important relationships with teachers and peers, they are far less likely to be motivated to learn.

The pandemic and remote learning have seriously disrupted those important connections, resulting in huge numbers of students losing the motivation to even show up for virtual classes, let alone participate. Bellwether Education Partners, an education nonprofit, estimates that between 1 million and 3 million U.S. students haven’t attended school since pandemic-related school closures began in March 2020, hitting high-risk groups including homeless students and children with disabilities particularly hard. And there is no silver bullet to solving the problem. Sruti Sriram is a current Ed School student and teaches English to 11th- and 12th-graders at a boarding school in Pune, India. Sriram says her school has tried different ways to keep students engaged, trying to find a balance between learning models. While there was early success with each new attempt, student engagement would inevitably drop off.

Sriram says from her own positive experience as a student in her Ed School classes, she has been inspired to be more intentional using tools like virtual breakout rooms to build relationships. She’s also recognized that, this year especially, the emphasis needs to be on how students are doing emotionally, not just academically.

“My students are going through so much at home. I’ve realized how important it is for students to feel supported in the classroom before I can harangue them about incomplete homework or give them a lot of corrections,” she says. “That’s always been true, but in remote learning it’s an even more apparent reminder that the job is to care for the whole student.”

Even during normal times, these relationships are important to academic development. During the pandemic, they are crucial. Research has shown that when teachers can build a good rapport with their students, those students are more motivated to do well in school. To build that rapport, students need to believe that their teacher has a good sense of their abilities.

“It’s critical to learning that a teacher has an accurate understanding of their students,” says Bonawitz. “When a child thinks a teacher doesn’t have a good sense of their abilities, it totally shapes what kind of exploration and projects they think they can pursue.”

In one lab experiment, Bonawitz has found that when children as young as 6 think their teacher is overestimating their abilities, they will choose less challenging work, while if a teacher underestimates their abilities, they will seek work that might be too difficult for them.

With the pandemic removing much of the one-on-one time for students and teachers to get to know each other well, it’s important for teachers to find new ways to show their students they know them.

“Reciprocity is really critical to make sure there is maximum engagement,” Bonawitz says. “Regular feedback and mini-assessments can help so that students know the teacher is aware of their current place and the teacher is using that information for tailoring the learning.”

Hinton says making room to provide students extra emotional support this year is so important, and finding additional opportunities, like through virtual office hours, can make a big difference for students and teachers to build relationships while apart and maintain motivation.

Jill Goldberg, Ed.M.’93, credits her students staying motivated thanks to recognizing new ways of building relationships. Goldberg, who teaches sixth grade English language arts in upstate New York, says it was challenging at first teaching to static profile pictures of students or empty black rectangles because her district, like many across the county, does not require students to turn on cameras when remote.

But then students, some shy or just unwilling to turn their cameras on during full class activities, started to reach out in other ways. Many found their voice over email. Others requested private Zoom breakout meetings to connect between classes or after school, sometimes to talk about academic work, other times just to share something personal, like a pair of twins in her class excited to share news of a new pet.

“It’s wonderful how many kids are so much more comfortable and proficient and proactive in initiating contact” over digital platforms, Goldberg says. Remote learning has also given Goldberg and her students a change of pace to their normal in-person schedule that left little time in the day to connect. Now, students have breaks between periods and teachers can use that time for extra help sessions or just one-on- one check-ins.

Professor Jal Mehta isn’t surprised that some students and teachers are finding positives during remote learning. Mehta says that while traditional in-person school can be exhausting for students required to be “on” and engaged all day with teachers and peers, remote learning has given some students a chance to slow down. “Teachers have reported more contact and conversations with students and families. I think some people have experienced that there’s less rush and a chance to do things in more depth,” Mehta says.

Caring for the Adults in the Room

Of course, not everyone is finding remote learning a happy new environment. In November, the Education Week Research Center found that nearly 75% of teachers say their morale is lower than it was before the pandemic. Trying to learn new technology, keep students invested, and deal with the challenges of their own lives is leaving many teachers burnt out.

With teachers feeling dejected from not keeping up with curriculum standards or blaming themselves for students falling behind, Hinton says now it’s more important than ever for teachers to not only show compassion for their students but also for themselves.

“Teachers have to treat this as a totally different year and be patient with themselves,” she says. “A great rule of thumb for practicing self-compassion is to treat yourself the way you would treat a best friend.”

That change in mentality was important for Ian Malmstrom, Ed.M.’10, a middle school history teacher and athletic director in Illinois.

“The most discouraging thing was realizing I wasn’t going to accomplish as much as I have in past years. That bothered me at first, the feeling I wasn’t doing as well as a teacher. But putting that stress on myself wasn’t going to work. I’ve accepted that,” Malmstrom says.

Malmstron isn’t alone. A survey by the RAND Corporation found in its American Educator Panels Survey in October that most classrooms are not proceeding at their normal pace, with 56% of teachers saying that they had covered half, or less than half, of their normal curriculum, and only 1 in 5 teachers saying they were on the same schedule as years past.

Rather than putting pressure on themselves to jam as much of the old curriculum into this year, experts like Mehta are advocating a “Marie Kondo” approach to curriculum, borrowing from the Japanese tidying expert. In his recent New York Times opinion piece, Mehta encourages teachers to accept a “less is more” attitude by “discarding the many topics that have accumulated like old souvenirs, while retaining essential knowledge and topics that spark joy.”

At her school in Providence, Rhode Island, academic dean Kaitlin Moran, Ed.M.’20, has worked with faculty and administrators to reduce their academic program to the most essential content and setting realistic learning goals. The school day itself has been shortened and longer blocks of instruction in subjects like math, science, and social studies have been shortened to accommodate students, including taking into account time spent on screens.

“I think what has helped students and teachers feel more motivated is by setting bite-size achievable goals that work towards a grade-level standard. As much as we can collaborate on best practices, that has also helped keep our team engaged and motivated,” Moran says.

To that end, Moran has also worked with teachers to implement targeted learning goals to address missed learning from the spring by having each student complete a diagnostic assessment, allowing teachers to know which areas of instruction to focus on to help close gaps. Not everything can simply be replaced virtually. One of the biggest losses since the pandemic hit has been extracurriculars. Malmstrom says athletics have been virtually nonexistent in Illinois since the start of the pandemic, and without them, many students have just given up.

“My students have just been starved for athletic opportunities,” Malmstrom says, citing several academically thriving students who have lost their motivation to do well in school. “We have more time, but people don’t have the desire to do as much as we used to. I have students who were mainly doing schoolwork to stay eligible for sports, and they’ve quit trying.”

Malmstrom and his colleagues have tried to find some replacements. In the fall, when the weather was nice, they started an afterschool running club, which had a great turnout of students eager to do any sort of outdoor activity. His school also launched a virtual chess club and quiz bowl team, offering online practices.

Malmstrom is realistic that these activities are only stopgaps until students can return to regular activities, but they have been helpful in keeping morale and motivation up.

“The students aren’t going to be interested in everything, but our hope is that each student can find something that engages him or her in addition to their regular classwork,” he says.

Eventually, the world will return to some new normal, and schools with it. While there are many challenges that students and teachers have faced during this year, there are some areas of remote learning that might endure.

Researchers like Mehta say the lessons learned during remote learning and the changes made to support students and teachers should spur an even greater effort to reimagine and rebuild schools.

“Schools weren’t working well for students pre-pandemic. To put things back exactly as they were is ignoring inequities and disengagement,” says Mehta.

When schools can be fully reopened, Mehta says leaders need to think about areas that helped keep students motivated this year and amplify them, including giving students greater agency over their learning and providing more time for teachers to connect with families.

“How do we create the space to do more of those things when we come back to regular school,” he says, “and what do we want to let go of to allow those things to grow? I think those are the questions I would ask everybody.”

Andrew Bauld, the communications coordinator at the Berkeley Carroll School in New York City, is a frequent contributor to Ed.

Happy Students Are Motivated Students

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

A Curious Mind

How educators and parents can help children's natural curiosity emerge — in the classroom and at home

Tools Help Schools in India With SEL During COVID

Creating Learning Environments to Support Student Motivation Post-Pandemic

On March 30, 2022, TLL hosted a talk by Professor Carlton Fong of Texas State University on the many ways the COVID-19 pandemic impacted student motivation. Professor Fong discussed evidence-based strategies to maximize student confidence, learning, support, and belonging.

Why Discuss Motivation?

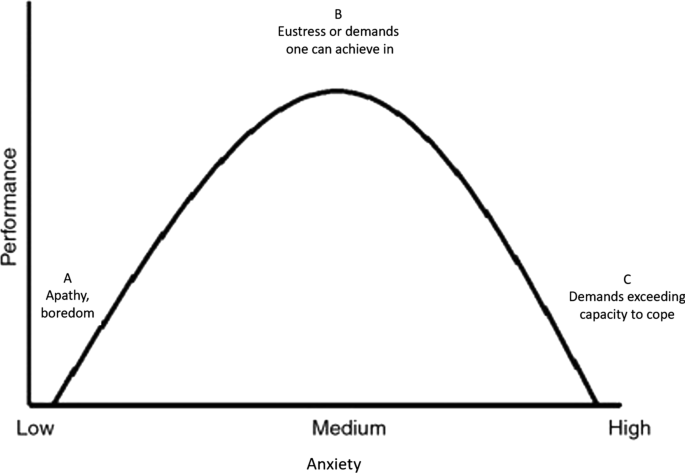

The COVID-19 pandemic brought many challenges and uncertainties into the lives of adolescents, including mental/physical health concerns, disruptions to social connections, socio-economic concerns, worries about catching COVID-19 or complying with restrictions, uncertainties about the future, and academic challenges. Of these factors, Scott et al. (2021) found that academics, and specifically academic motivation, was the most common worry among adolescents.

In a meta-analysis of over 150 studies that used the Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI), Fong and a team of educational psychologists concluded that of the ten LASSI subscales, motivation strategies were the strongest predictors of GPA and persistence (Fong et al., 2021).

Some studies found that aspects of students’ motivation, such as their sense of self-efficacy for learning, decreased significantly at the start of the pandemic with the rapid shift to online instruction ( Hilpert et al., 2021 ). Given this, it is imperative to adopt practices that rekindle motivation if colleges want their students to be academically successful.

Motivation theories

In a recent article , Professor Fong synthesized five theories of motivation to create a framework for student motivation during the pandemic. These theories are described briefly below and in more depth in the associated paper.

- Self-Determination Theory considers how a student’s environment can satisfy or thwart the student’s feelings of competence, autonomy, and relatedness and describes how these three basic needs, in turn, influence students’ motivation to engage in a learning environment.

- Attribution Theory focuses on how students identify the causes of their success or failure, considering the extent to which students feel they can control the outcome.

- Social Cognitive Theory explores the relationship between students and their environment, self-efficacy and perception of the situation, and behavior. Determinations of self-efficacy can include mastery experiences, vicarious experiences (i.e., the success or failure of peers), messages and feedback received from others (e.g., teachers), and emotions.

- Situated Expectancy-Value Theory considers how achievement choices are informed by expected outcomes and perceptions of the value and costs of engaging in an activity.

- Goal Orientation Theory ascribes meaning to the attainment of mastery goals (i.e. developing competence) and performance goals (i.e. demonstrating competence).

When viewed collectively, these five theories describe a range of past, present, and future factors that influence student motivation. Students arrive at college having been shaped by their identities, upbringing, interactions, successes, and failures. In college, student motivation is impacted by their sense of agency, how they can apply the assets they bring to the academic context, the personal and collective value of what they are learning, and their sense of belonging. Students are also considering their learning in the context of their future personal and familial goals, their sense of meaning, and their sense of what is possible for them given the realities of disparate opportunity structures.

COVID-Related Shifts

During the COVID-19 pandemic, students experienced instructional, social, future-oriented, and racial/sociocultural shifts that impacted their motivation in a variety of ways.

Instructional shifts included the use of new technology and assessment types and a reduction in certain types of hands-on learning. Many students experienced lower self-efficacy because they had fewer mastery experiences in online contexts, limited background in online learning, limited vicarious experiences, limited verbal encouragement, and increased anxiety. Shifts in student feelings of autonomy were mixed. Many students felt that they had less autonomy due to the sudden mandatory shift online and the tendencies of some instructors to be more controlling due to their personal feelings of stress and burnout. At the same time, some students gained additional autonomy as instructors implemented asynchronous, student-paced learning options and more open-ended assessments such as projects.

Socially, students had less reliable access to peers and instructors and many students faced mental health challenges. One study found that regardless of student beliefs about the effectiveness of online learning, a lower sense of belonging led to lower academic motivation. Similarly, poor mental health conditions also reduced motivation. Fortunately, virtual interactions increased positive emotions and feelings of relatedness, buffering some of the negative impacts of physical isolation from others.

Student perceptions of the future also shifted as they contemplated a bleak economic outlook, gained new admiration for healthcare professionals, or struggled to stay engaged with their current academic work. The uncertainty about the future made it harder to derive motivation from a sense of utility value or clear mastery goals. Some students also worried about the cost of higher education, particularly if they were forced to take an extra semester or year to make up missed coursework. However, some students experienced a renewed interest in STEM, and medicine in particular, due to its perceived value during the pandemic.

Race and sociocultural factors were also prominent during 2020 and 2021 as students witnessed increased attention to racialized police brutality, disparities in healthcare, and increased violence against APIDA individuals. In response, many students developed increased prosocial motivation aligned with community-oriented values. Many students also experienced oppression firsthand, which may have decreased their motivation or sparked motivational resilience.

While these shifts were amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, they will continue to matter long after the pandemic ends. The college experience nearly always includes these four shifts, though their magnitude will vary by student, institution, and the state of the world.

Instructional Strategies

While certain aspects of student motivation remain outside of an instructor’s control, there are several strategies instructors can adopt to make their classroom a more motivating environment. To promote feelings of autonomy among students, instructors should take care to give students meaningful choices about what they work on and how. The more ownership students can take, the more motivated they will be to learn.

Constructive feedback can also motivate students, but instructors should be mindful of how they deliver feedback. Positive feedback is more likely to increase student feelings of competence, but criticism can still be motivating if it outlines concrete ways to improve. When giving critical feedback, instructors should emphasize that they have high standards but believe in their students’ ability to meet those standards. Fong also highlighted the difference between feedback and grades. To effectively motivate students, instructors should deemphasize competition and numerical grades in favor of mastery. Practices like allowing assignment revisions can help students build competence and become more comfortable seeking and responding to feedback.

Fong also recommends that instructors share their rationales for assigning particular work or including particular topics in a course. This additional context can help students relate their coursework to their personal goals and increase its perceived value.

To increase students’ sense of social belonging , Fong recommended that instructors try to normalize challenges and growth. Make it clear to students that struggling is common and feelings of belonging take time, but that you as the instructor believe in their ability to surmount the obstacles they face. Students with a growth mindset are more likely to seek feedback and put in the effort required to learn and improve.

While Fong’s talk primarily focused on classroom learning, he directed faculty working with graduate students in research contexts to check out the work of Professor Nathan Hall at McGill University .

Guest Speaker

Carlton Fong, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Curriculum and Instruction, Texas State University

Dr. Carlton J. Fong is an assistant professor in the Graduate Program in Developmental Education and the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Texas State University. As a scholar-practitioner at the intersection of educational psychology and higher education, Dr. Fong uses a sociocultural lens to study motivational factors influencing postsecondary student engagement, achievement, and persistence. He is also an expert in meta-analysis and research synthesis and is currently the chair of the Motivation in Education Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association (AERA). In 2021, he was recognized as an Association for Psychological Science Rising Star and an AERA Deeper Learning Fellow .

Fong, C. J. (2022) Academic motivation in a pandemic context: a conceptual review of prominent theories and an integrative model, Educational Psychology , https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2022.2026891

Fong, C. J., Krou, M. R., Johnston-Ashton, K., Hoff, M. A., Lin, S., & Gonzales, C. (2021). Lassi’s great adventure: A meta-analysis of the Learning and Study Strategies Inventory and academic outcomes. Educational Research Review , 34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100407

Hilpert, J. C., Bernacki, M. L., & Cogliano, M. C. (2022) Coping with the transition to remote instruction: Patterns of self-regulated engagement in a large post-secondary biology course. Journal of Research on Technology in Education , 54:sup1, S219-S235, https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1936702

Scott, S. R., Rivera, K. M., Rushing, E., Manczak, E. M., Rozek, C. S., & Doom, J. R. (2021). “I Hate This”: A qualitative analysis of adolescents’ self-reported challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Adolescent Health , 68(2), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.010

Written by Kate Weishaar

assessment belonging community growth mindset inclusive classroom student engagement student motivation wellbeing

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld director of growth modeling and data analytics - nwea jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea karyn lewis , and karyn lewis vice president of research and policy partnerships - nwea emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.

These numbers are alarming and potentially demoralizing, especially given the heroic efforts of students to learn and educators to teach in incredibly trying times. From our perspective, these test-score drops in no way indicate that these students represent a “ lost generation ” or that we should give up hope. Most of us have never lived through a pandemic, and there is so much we don’t know about students’ capacity for resiliency in these circumstances and what a timeline for recovery will look like. Nor are we suggesting that teachers are somehow at fault given the achievement drops that occurred between 2020 and 2021; rather, educators had difficult jobs before the pandemic, and now are contending with huge new challenges, many outside their control.

Clearly, however, there’s work to do. School districts and states are currently making important decisions about which interventions and strategies to implement to mitigate the learning declines during the last two years. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) investments from the American Rescue Plan provided nearly $200 billion to public schools to spend on COVID-19-related needs. Of that sum, $22 billion is dedicated specifically to addressing learning loss using “evidence-based interventions” focused on the “ disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups. ” Reviews of district and state spending plans (see Future Ed , EduRecoveryHub , and RAND’s American School District Panel for more details) indicate that districts are spending their ESSER dollars designated for academic recovery on a wide variety of strategies, with summer learning, tutoring, after-school programs, and extended school-day and school-year initiatives rising to the top.

Comparing the negative impacts from learning disruptions to the positive impacts from interventions

To help contextualize the magnitude of the impacts of COVID-19, we situate test-score drops during the pandemic relative to the test-score gains associated with common interventions being employed by districts as part of pandemic recovery efforts. If we assume that such interventions will continue to be as successful in a COVID-19 school environment, can we expect that these strategies will be effective enough to help students catch up? To answer this question, we draw from recent reviews of research on high-dosage tutoring , summer learning programs , reductions in class size , and extending the school day (specifically for literacy instruction) . We report effect sizes for each intervention specific to a grade span and subject wherever possible (e.g., tutoring has been found to have larger effects in elementary math than in reading).

Figure 1 shows the standardized drops in math test scores between students testing in fall 2019 and fall 2021 (separately by elementary and middle school grades) relative to the average effect size of various educational interventions. The average effect size for math tutoring matches or exceeds the average COVID-19 score drop in math. Research on tutoring indicates that it often works best in younger grades, and when provided by a teacher rather than, say, a parent. Further, some of the tutoring programs that produce the biggest effects can be quite intensive (and likely expensive), including having full-time tutors supporting all students (not just those needing remediation) in one-on-one settings during the school day. Meanwhile, the average effect of reducing class size is negative but not significant, with high variability in the impact across different studies. Summer programs in math have been found to be effective (average effect size of .10 SDs), though these programs in isolation likely would not eliminate the COVID-19 test-score drops.

Figure 1: Math COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) Table 2; summer program results are pulled from Lynch et al (2021) Table 2; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span; Figles et al. and Lynch et al. report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. We were unable to find a rigorous study that reported effect sizes for extending the school day/year on math performance. Nictow et al. and Kraft & Falken (2021) also note large variations in tutoring effects depending on the type of tutor, with larger effects for teacher and paraprofessional tutoring programs than for nonprofessional and parent tutoring. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

Figure 2 displays a similar comparison using effect sizes from reading interventions. The average effect of tutoring programs on reading achievement is larger than the effects found for the other interventions, though summer reading programs and class size reduction both produced average effect sizes in the ballpark of the COVID-19 reading score drops.

Figure 2: Reading COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; extended-school-day results are from Figlio et al. (2018) Table 2; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) ; summer program results are pulled from Kim & Quinn (2013) Table 3; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: While Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span, Figlio et al. and Kim & Quinn report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

There are some limitations of drawing on research conducted prior to the pandemic to understand our ability to address the COVID-19 test-score drops. First, these studies were conducted under conditions that are very different from what schools currently face, and it is an open question whether the effectiveness of these interventions during the pandemic will be as consistent as they were before the pandemic. Second, we have little evidence and guidance about the efficacy of these interventions at the unprecedented scale that they are now being considered. For example, many school districts are expanding summer learning programs, but school districts have struggled to find staff interested in teaching summer school to meet the increased demand. Finally, given the widening test-score gaps between low- and high-poverty schools, it’s uncertain whether these interventions can actually combat the range of new challenges educators are facing in order to narrow these gaps. That is, students could catch up overall, yet the pandemic might still have lasting, negative effects on educational equality in this country.

Given that the current initiatives are unlikely to be implemented consistently across (and sometimes within) districts, timely feedback on the effects of initiatives and any needed adjustments will be crucial to districts’ success. The Road to COVID Recovery project and the National Student Support Accelerator are two such large-scale evaluation studies that aim to produce this type of evidence while providing resources for districts to track and evaluate their own programming. Additionally, a growing number of resources have been produced with recommendations on how to best implement recovery programs, including scaling up tutoring , summer learning programs , and expanded learning time .

Ultimately, there is much work to be done, and the challenges for students, educators, and parents are considerable. But this may be a moment when decades of educational reform, intervention, and research pay off. Relying on what we have learned could show the way forward.

Related Content

Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Karyn Lewis

December 3, 2020

Lindsay Dworkin, Karyn Lewis

October 13, 2021

Early Childhood Education Education Access & Equity Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Catherine Mata

October 21, 2024

Dick Startz

October 17, 2024

Mary Burns, Rebecca Winthrop, Michael Trucano, Natasha Luther

October 15, 2024

Covid-19’s Impact on Students’ Academic and Mental Well-Being

The pandemic has revealed—and exacerbated—inequities that hold many students back. Here’s how teachers can help.

Your content has been saved!

The pandemic has shone a spotlight on inequality in America: School closures and social isolation have affected all students, but particularly those living in poverty. Adding to the damage to their learning, a mental health crisis is emerging as many students have lost access to services that were offered by schools.

No matter what form school takes when the new year begins—whether students and teachers are back in the school building together or still at home—teachers will face a pressing issue: How can they help students recover and stay on track throughout the year even as their lives are likely to continue to be disrupted by the pandemic?

New research provides insights about the scope of the problem—as well as potential solutions.

The Achievement Gap Is Likely to Widen

A new study suggests that the coronavirus will undo months of academic gains, leaving many students behind. The study authors project that students will start the new school year with an average of 66 percent of the learning gains in reading and 44 percent of the learning gains in math, relative to the gains for a typical school year. But the situation is worse on the reading front, as the researchers also predict that the top third of students will make gains, possibly because they’re likely to continue reading with their families while schools are closed, thus widening the achievement gap.

To make matters worse, “few school systems provide plans to support students who need accommodations or other special populations,” the researchers point out in the study, potentially impacting students with special needs and English language learners.

Of course, the idea that over the summer students forget some of what they learned in school isn’t new. But there’s a big difference between summer learning loss and pandemic-related learning loss: During the summer, formal schooling stops, and learning loss happens at roughly the same rate for all students, the researchers point out. But instruction has been uneven during the pandemic, as some students have been able to participate fully in online learning while others have faced obstacles—such as lack of internet access—that have hindered their progress.

In the study, researchers analyzed a national sample of 5 million students in grades 3–8 who took the MAP Growth test, a tool schools use to assess students’ reading and math growth throughout the school year. The researchers compared typical growth in a standard-length school year to projections based on students being out of school from mid-March on. To make those projections, they looked at research on the summer slide, weather- and disaster-related closures (such as New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina), and absenteeism.

The researchers predict that, on average, students will experience substantial drops in reading and math, losing roughly three months’ worth of gains in reading and five months’ worth of gains in math. For Megan Kuhfeld, the lead author of the study, the biggest takeaway isn’t that learning loss will happen—that’s a given by this point—but that students will come back to school having declined at vastly different rates.

“We might be facing unprecedented levels of variability come fall,” Kuhfeld told me. “Especially in school districts that serve families with lots of different needs and resources. Instead of having students reading at a grade level above or below in their classroom, teachers might have kids who slipped back a lot versus kids who have moved forward.”

Disproportionate Impact on Students Living in Poverty and Students of Color

Horace Mann once referred to schools as the “great equalizers,” yet the pandemic threatens to expose the underlying inequities of remote learning. According to a 2015 Pew Research Center analysis , 17 percent of teenagers have difficulty completing homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection. For Black students, the number spikes to 25 percent.

“There are many reasons to believe the Covid-19 impacts might be larger for children in poverty and children of color,” Kuhfeld wrote in the study. Their families suffer higher rates of infection, and the economic burden disproportionately falls on Black and Hispanic parents, who are less likely to be able to work from home during the pandemic.

Although children are less likely to become infected with Covid-19, the adult mortality rates, coupled with the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic, will likely have an indelible impact on their well-being.

Impacts on Students’ Mental Health

That impact on well-being may be magnified by another effect of school closures: Schools are “the de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” providing mental health services to 57 percent of adolescents who need care, according to the authors of a recent study published in JAMA Pediatrics . School closures may be especially disruptive for children from lower-income families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools.

“The Covid-19 pandemic may worsen existing mental health problems and lead to more cases among children and adolescents because of the unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and economic recession,” write the authors of that study.

A major concern the researchers point to: Since most mental health disorders begin in childhood, it is essential that any mental health issues be identified early and treated. Left untreated, they can lead to serious health and emotional problems. In the short term, video conferencing may be an effective way to deliver mental health services to children.

Mental health and academic achievement are linked, research shows. Chronic stress changes the chemical and physical structure of the brain, impairing cognitive skills like attention, concentration, memory, and creativity. “You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University in a 2014 interview . In her research, Wellman discovered that chronic stress causes the connections between brain cells to shrink in mice, leading to cognitive deficiencies in the prefrontal cortex.

While trauma-informed practices were widely used before the pandemic, they’re likely to be even more integral as students experience economic hardships and grieve the loss of family and friends. Teachers can look to schools like Fall-Hamilton Elementary in Nashville, Tennessee, as a model for trauma-informed practices .

3 Ways Teachers Can Prepare

When schools reopen, many students may be behind, compared to a typical school year, so teachers will need to be very methodical about checking in on their students—not just academically but also emotionally. Some may feel prepared to tackle the new school year head-on, but others will still be recovering from the pandemic and may still be reeling from trauma, grief, and anxiety.

Here are a few strategies teachers can prioritize when the new school year begins:

- Focus on relationships first. Fear and anxiety about the pandemic—coupled with uncertainty about the future—can be disruptive to a student’s ability to come to school ready to learn. Teachers can act as a powerful buffer against the adverse effects of trauma by helping to establish a safe and supportive environment for learning. From morning meetings to regular check-ins with students, strategies that center around relationship-building will be needed in the fall.

- Strengthen diagnostic testing. Educators should prepare for a greater range of variability in student learning than they would expect in a typical school year. Low-stakes assessments such as exit tickets and quizzes can help teachers gauge how much extra support students will need, how much time should be spent reviewing last year’s material, and what new topics can be covered.

- Differentiate instruction—particularly for vulnerable students. For the vast majority of schools, the abrupt transition to online learning left little time to plan a strategy that could adequately meet every student’s needs—in a recent survey by the Education Trust, only 24 percent of parents said that their child’s school was providing materials and other resources to support students with disabilities, and a quarter of non-English-speaking students were unable to obtain materials in their own language. Teachers can work to ensure that the students on the margins get the support they need by taking stock of students’ knowledge and skills, and differentiating instruction by giving them choices, connecting the curriculum to their interests, and providing them multiple opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

- Share article

In this video, Navajo student Miles Johnson shares how he experienced the stress and anxiety of schools shutting down last year. Miles’ teacher shared his experience and those of her other students in a recent piece for Education Week. In these short essays below, teacher Claire Marie Grogan’s 11th grade students at Oceanside High School on Long Island, N.Y., describe their pandemic experiences. Their writings have been slightly edited for clarity. Read Grogan’s essay .

“Hours Staring at Tiny Boxes on the Screen”

By Kimberly Polacco, 16

I stare at my blank computer screen, trying to find the motivation to turn it on, but my finger flinches every time it hovers near the button. I instead open my curtains. It is raining outside, but it does not matter, I will not be going out there for the rest of the day. The sound of pounding raindrops contributes to my headache enough to make me turn on my computer in hopes that it will give me something to drown out the noise. But as soon as I open it up, I feel the weight of the world crash upon my shoulders.

Each 42-minute period drags on by. I spend hours upon hours staring at tiny boxes on a screen, one of which my exhausted face occupies, and attempt to retain concepts that have been presented to me through this device. By the time I have the freedom of pressing the “leave” button on my last Google Meet of the day, my eyes are heavy and my legs feel like mush from having not left my bed since I woke up.

Tomorrow arrives, except this time here I am inside of a school building, interacting with my first period teacher face to face. We talk about our favorite movies and TV shows to stream as other kids pile into the classroom. With each passing period I accumulate more and more of these tiny meaningless conversations everywhere I go with both teachers and students. They may not seem like much, but to me they are everything because I know that the next time I am expected to report to school, I will be trapped in the bubble of my room counting down the hours until I can sit down in my freshly sanitized wooden desk again.

“My Only Parent Essentially on Her Death Bed”

By Nick Ingargiola, 16

My mom had COVID-19 for ten weeks. She got sick during the first month school buildings were shut. The difficulty of navigating an online classroom was already overwhelming, and when mixed with my only parent essentially on her death bed, it made it unbearable. Focusing on schoolwork was impossible, and watching my mother struggle to lift up her arm broke my heart.

My mom has been through her fair share of diseases from pancreatic cancer to seizures and even as far as a stroke that paralyzed her entire left side. It is safe to say she has been through a lot. The craziest part is you would never know it. She is the strongest and most positive person I’ve ever met. COVID hit her hard. Although I have watched her go through life and death multiple times, I have never seen her so physically and mentally drained.

I initially was overjoyed to complete my school year in the comfort of my own home, but once my mom got sick, I couldn’t handle it. No one knows what it’s like to pretend like everything is OK until they are forced to. I would wake up at 8 after staying up until 5 in the morning pondering the possibility of losing my mother. She was all I had. I was forced to turn my camera on and float in the fake reality of being fine although I wasn’t. The teachers tried to keep the class engaged by obligating the students to participate. This was dreadful. I didn’t want to talk. I had to hide the distress in my voice. If only the teachers understood what I was going through. I was hesitant because I didn’t want everyone to know that the virus that was infecting and killing millions was knocking on my front door.

After my online classes, I was required to finish an immense amount of homework while simultaneously hiding my sadness so that my mom wouldn’t worry about me. She was already going through a lot. There was no reason to add me to her list of worries. I wasn’t even able to give her a hug. All I could do was watch.

“The Way of Staying Sane”

By Lynda Feustel, 16

Entering year two of the pandemic is strange. It barely seems a day since last March, but it also seems like a lifetime. As an only child and introvert, shutting down my world was initially simple and relatively easy. My friends and I had been super busy with the school play, and while I was sad about it being canceled, I was struggling a lot during that show and desperately needed some time off.

As March turned to April, virtual school began, and being alone really set in. I missed my friends and us being together. The isolation felt real with just my parents and me, even as we spent time together. My friends and I began meeting on Facetime every night to watch TV and just be together in some way. We laughed at insane jokes we made and had homework and therapy sessions over Facetime and grew closer through digital and literal walls.

The summer passed with in-person events together, and the virus faded into the background for a little while. We went to the track and the beach and hung out in people’s backyards.

Then school came for us in a more nasty way than usual. In hybrid school we were separated. People had jobs, sports, activities, and quarantines. Teachers piled on work, and the virus grew more present again. The group text put out hundreds of messages a day while the Facetimes came to a grinding halt, and meeting in person as a group became more of a rarity. Being together on video and in person was the way of staying sane.

In a way I am in a similar place to last year, working and looking for some change as we enter the second year of this mess.

“In History Class, Reports of Heightening Cases”

By Vivian Rose, 16

I remember the moment my freshman year English teacher told me about the young writers’ conference at Bread Loaf during my sophomore year. At first, I didn’t want to apply, the deadline had passed, but for some strange reason, the directors of the program extended it another week. It felt like it was meant to be. It was in Vermont in the last week of May when the flowers have awakened and the sun is warm.

I submitted my work, and two weeks later I got an email of my acceptance. I screamed at the top of my lungs in the empty house; everyone was out, so I was left alone to celebrate my small victory. It was rare for them to admit sophomores. Usually they accept submissions only from juniors and seniors.

That was the first week of February 2020. All of a sudden, there was some talk about this strange virus coming from China. We thought nothing of it. Every night, I would fall asleep smiling, knowing that I would be able to go to the exact conference that Robert Frost attended for 42 years.

Then, as if overnight, it seemed the virus had swung its hand and had gripped parts of the country. Every newscast was about the disease. Every day in history, we would look at the reports of heightening cases and joke around that this could never become a threat as big as Dr. Fauci was proposing. Then, March 13th came around--it was the last day before the world seemed to shut down. Just like that, Bread Loaf would vanish from my grasp.

“One Day Every Day Won’t Be As Terrible”

By Nick Wollweber, 17

COVID created personal problems for everyone, some more serious than others, but everyone had a struggle.

As the COVID lock-down took hold, the main thing weighing on my mind was my oldest brother, Joe, who passed away in January 2019 unexpectedly in his sleep. Losing my brother was a complete gut punch and reality check for me at 14 and 15 years old. 2019 was a year of struggle, darkness, sadness, frustration. I didn’t want to learn after my brother had passed, but I had to in order to move forward and find my new normal.

Routine and always having things to do and places to go is what let me cope in the year after Joe died. Then COVID came and gave me the option to let up and let down my guard. I struggled with not wanting to take care of personal hygiene. That was the beginning of an underlying mental problem where I wouldn’t do things that were necessary for everyday life.

My “coping routine” that got me through every day and week the year before was gone. COVID wasn’t beneficial to me, but it did bring out the true nature of my mental struggles and put a name to it. Since COVID, I have been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety. I began taking antidepressants and going to therapy a lot more.

COVID made me realize that I’m not happy with who I am and that I needed to change. I’m still not happy with who I am. I struggle every day, but I am working towards a goal that one day every day won’t be as terrible.

Coverage of social and emotional learning is supported in part by a grant from the NoVo Foundation, at www.novofoundation.org . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the March 31, 2021 edition of Education Week as What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Remaining motivated despite the limitations: University students’ learning propensity during the COVID-19 pandemic

Maila dh rahiem.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Received 2020 Jul 17; Revised 2020 Dec 1; Accepted 2020 Dec 2; Issue date 2021 Jan.

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

Despite all the limitations, students stayed motivated and kept moving forward.

Students were driven autonomously by mental fortitude.

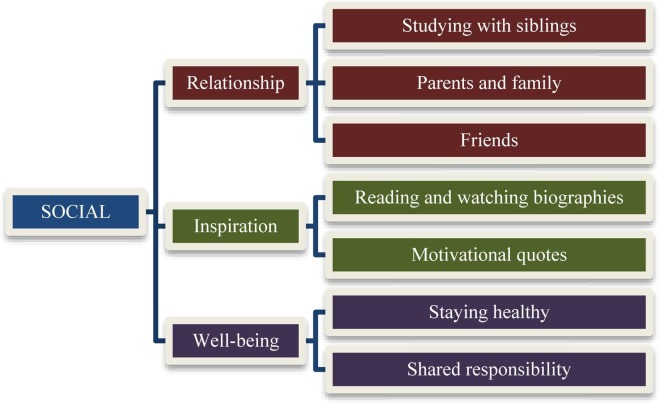

They were often influenced by their social groups, their families and friends.

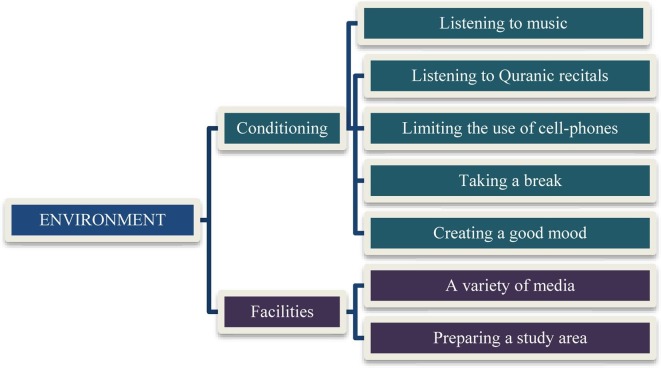

The students were motivated by their learning atmosphere and facilities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Emergency remote learning, University, Students, Youth, Online learning, Motivation, Resilience

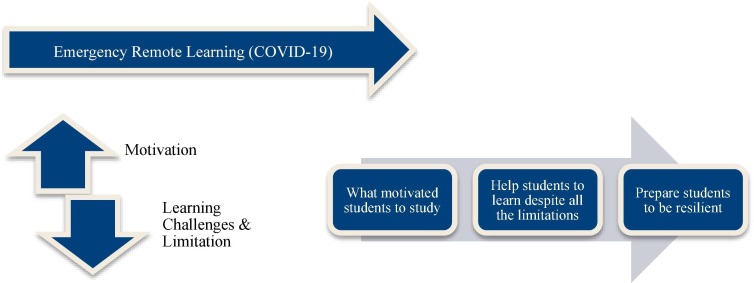

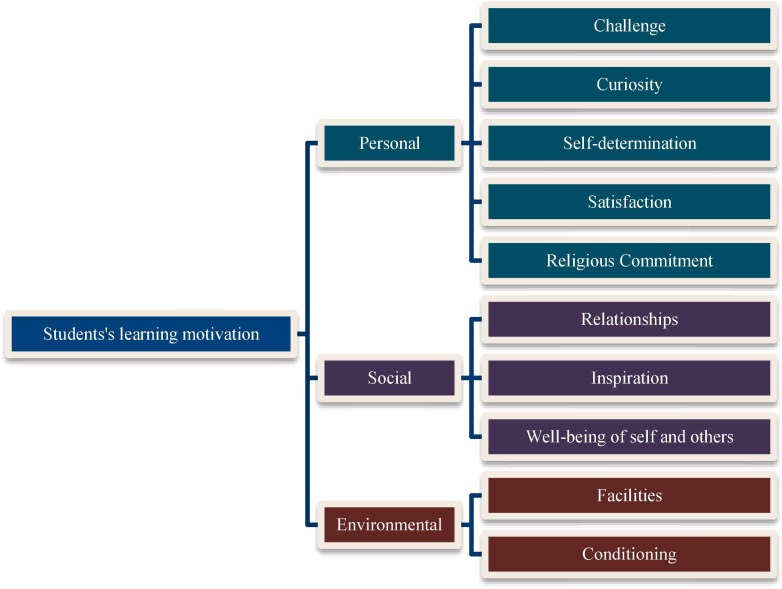

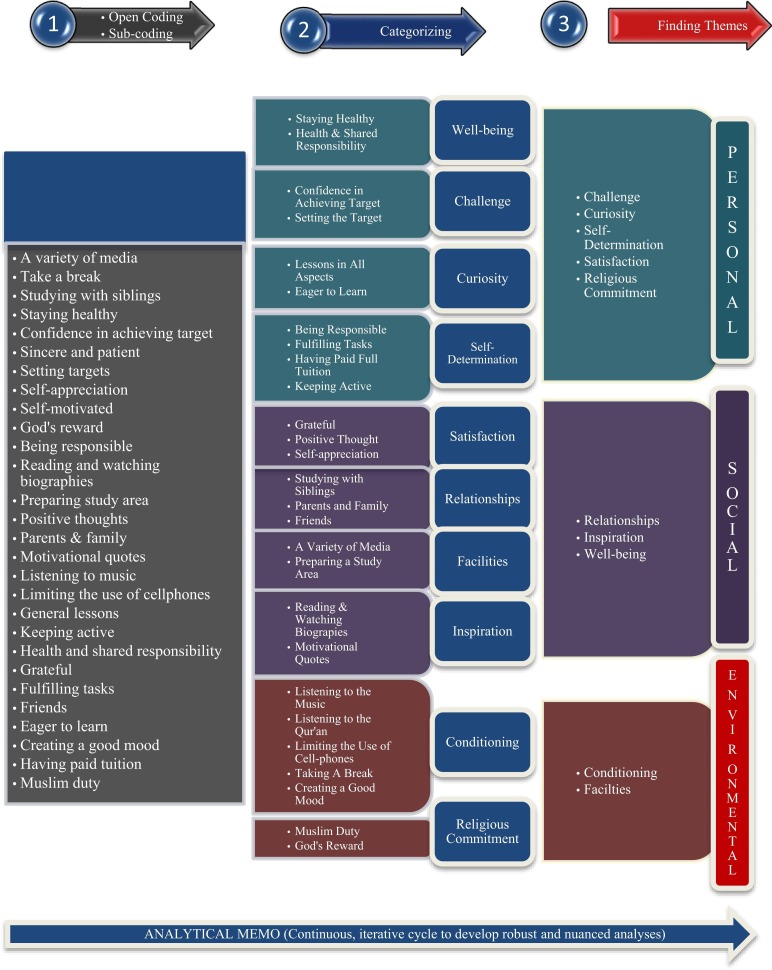

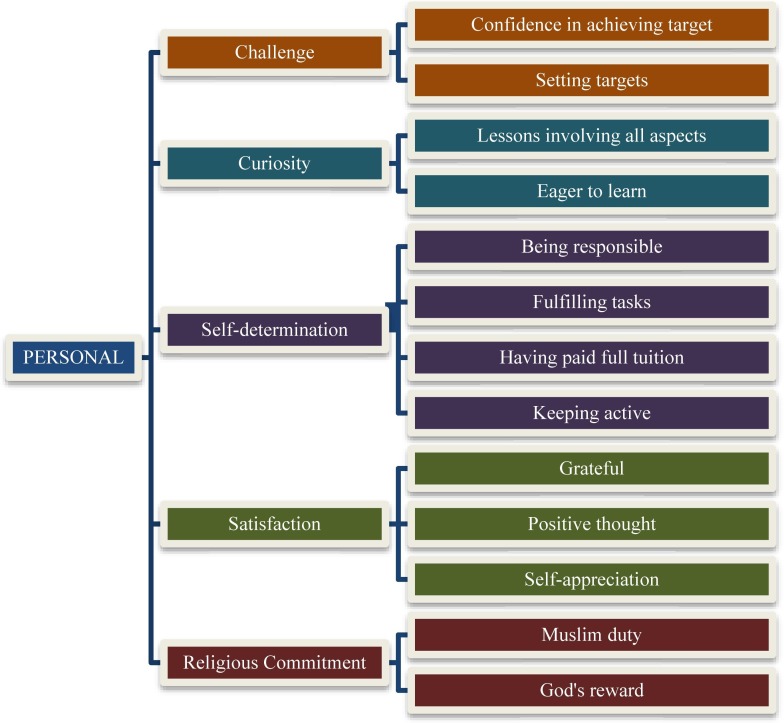

This study explored how university students remained motivated to learn, despite all the limitations they encountered and endured during the COVID-19 pandemic. This work was carried out in Indonesia, but the benefits are beyond a state boundary. The study examines how university students in developing countries have faced obstacles, and yet despite this, they are still trying their hardest to stay focused on achieving their personal goals during the pandemic. This research employed a qualitative phenomenological approach, involving eighty students that were studying at the Faculty of Education at a state university in Jakarta, Indonesia. As data collection techniques, students were asked to write learning log diaries and reflective essays and to participate in an online focus group discussion. The results showed that the students' motivation to remain learning during the COVID-19 pandemic fell into three key themes, each with associated sub-themes. The three themes and sub-themes described were: (a) personal, with sub-themes of challenge, curiosity, self-determination, satisfaction and religious commitment; (b) social, with sub-themes of relationships, inspiration, and well-being of self and others; and (c) environmental, with sub-themes of facilities and conditioning. The themes and sub-themes indicate the source of motivation for these university students to learn during the pandemic. This study concluded that these emerging adults were both intrinsically and extrinsically autonomously motivated and committed to their studies. Most of these students were motivated by their consequential aspirations, not by a controlled motivation, nor were they motivated by a reward, a penalty, or a rule that propelled them. By defining how the students managed to empower themselves, this study recommends the importance of preparing students to be more resilient and to enable them to cultivate the ability to remain optimistic and motivated to succeed and overcome any of life’s adversities.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created an extremely fast expanding health crisis with drastic implications throughout 2020 ( Gómez-Salgado, Andrés-Villas, Domínguez-Salas, Díaz-Milanés, & Ruiz-Frutos, 2020 ). Most nations responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by swiftly enforcing public health containment measures known as non-pharmaceutical interventions ( Anderson et al., 2020 , Cauchemez et al., 2008 , Cauchemez et al., 2009 , Chinazzi et al., 2020 , Djidjou-Demasse et al., 2020 ); and adopted a school closure strategy ( Anderson et al., 2020 , Ebrahim et al., 2020 ).

In the first week of April, the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization announced that 195 countries had implemented national school closures, affecting almost 91.3 percent of the student population, or 1.598.099.000 affected learners ( UNESCO, 2020 ). Courses moved from in-person learning to online learning, predominantly using information and communication technology (ICT) ( Evans et al., 2020 , Quezada et al., 2020 , Sandars et al., 2020 , Woolliscroft, 2020 ). These measures could not be easily enforced and created many issues due to a significant proportion of the curriculum being used, which was not originally planned for online or remote learning ( Bozkurt and Sharma, 2020 , Hodges et al., 2020 ); similarly educators themselves were not equipped for online learning or digital resource use ( Quezada et al., 2020 ); and many students did not have the required devices, internet access or resources needed to study remotely online ( Assunção Flores and Gago, 2020 , Rahiem, 2020a , Rahiem, 2020b ). Moreover, some learners and educators were not familiar with the digital platforms and online programs that they were required to use at such short notice ( Huber and Helm, 2020 , Rasmitadila et al., 2020 ).

The transition to working and studying from home, which took place rapidly, caused numerous issues for the education sector, including higher education with university students dealing with significant obstacles to their learning process. Schiff, Zasiekina, Pat-Horenczyk, and Benbenishty (2020) investigated the practical challenges and concerns that university students encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic in two countries: Israel and Ukraine, with two large samples of university students from both countries. Results showed that the students' key practical challenges in both countries included fears about their family health and their learning assignments. The study reported that the degree of exposure and difficulties in both countries varied, but their connection with the varying students' concerns appears robust. More precisely, the constant exposure to the threat posed to the community by the media contributed to their increased anxiety and affected the students' learning.

Huang et al. (2020) studied the Chinese government's policy on pandemic education, focusing on how the government ensured uninterrupted learning while classes were disrupted by transforming the entire education system and implementing online learning methods. They pointed out that there were many barriers to this rapid reform: 1) lack of preparation time, teachers had not prepared their learning material to enable them to adjust to online learning, and the preparation of such material was time-consuming; 2) teachers/students' isolation, left them frustrated and helpless; and 3) The need for an appropriate instructional approach to keep students motivated and engaged during the long period of online learning, especially because distance learning drop-out rates are typically higher than on-campus-based learning.

Many technologically advanced countries already had e-learning and online education programs in place when the pandemic first began. While in developing countries, where internet service and technological equipment availability is often limited, the learning adaptation was more complicated ( Farooq, Rathore, & Mansoor, 2020 ). Chung, Subramaniam, and Dass (2020) looked at online learning preparedness among university students in Malaysia. Data from 399 students in two different courses showed that respondents were generally prepared for online learning. However, more than half of the respondents implied that they did not want to continue studying online in the future, if they were given a choice. While internet access appears to be the biggest challenge for undergraduates, understanding the subject content was also a major issue for diploma students.

Emon, Alif, and Islam (2020) examined the problems in Bangladesh due to online learning in higher education during the COVID-19 enforced school closure. In Bangladesh, all the universities were directed by the Minister of Education to conduct online education. While some view this as an education-friendly policy, a recent survey of 2038 students in 45 higher education institutions run by BioTED, a novel training and research initiative, found that one-third of Bangladeshi students did not want to engage in online academic activities. The same study also found that 55 percent of students did not have adequate internet connectivity, and 44.7 percent did not have access to a computer (i.e., laptop, PC, tablet, etc.) to effectively participate in online teaching.

Ramij and Sultana (2020) researched the preparedness and practicality of online education in Bangladesh during the pandemic. The research analyzed primary information gathered through a survey. A logistic regression model was applied to explain the assumptions, in line with the collected data's descriptive interpretation. The results suggested that the lack of technical infrastructure, high internet prices, low internet speed, the financial crisis, and mental strain on students were the key barriers to online education in Bangladesh for the majority of students.

Another research in Bangladesh, Mamun, Chandrima, and Griffiths (2020) looked at the case of a private university student and his mother from Bogra, Bangladesh, who committed suicide together due to family issues that arose due to studying at home. He concluded that governments in Bangladesh and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) should think very carefully about online schooling before making it mandatory. LMIC students are much less likely to have the required access to the internet and technology needed to enable online education.

Farooq et al. (2020) explored the problems faced by medical faculty members and students in Pakistan when participating in online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their data identified the following challenges: lack of faculty preparation and institutional support, internet accessibility problems, student engagement, online evaluation, and difficulties in recognizing the unique complexities of online education.

Kapasia et al. (2020) examined the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on undergraduate and postgraduate students from various colleges and universities in West Bengal, India, using an online survey involving 232 students that was conducted from 1 May to 8 May 2020. The study showed that students, particularly those from remote areas and disadvantaged parts, were confronted with various problems related to depression, poor network connectivity, and an unfavorable home study climate.

The study discussed in this article is part of a larger project on Emergency Remote Learning (ERL) in tertiary education in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research found that students had paradoxical viewpoints and insights into learning; ERL was viewed as flexible yet challenging ( Rahiem, 2020a ). Students said that studying remotely at home allowed them the flexibility to control their own time, which provided them with additional time for self-care, daily exercise at home, and a lot of family time. At the same time, they also study in a comfortable and quiet environment. Contradictory to the degree of flexibility, they argued that lecturers overwhelmed them with assignments, and they, therefore, found it difficult to control their time. They felt distracted by their siblings and the noise at home, while a few of them thought that, compared to face-to-face learning, remote learning was much more tiring. They complained about technological interference while studying, costly internet costs, less structured courses, and difficulties accessing learning materials during the ERL ( Rahiem, 2020a ). The study also explained the technology barriers and challenges in using ICT that the students faced: device issues, internet connectivity, technology costs, and lack of technology skills. Students had problems with incompatible devices, sharing devices with other family members, unstable internet connection, restricted or unavailable internet access, data costs, purchasing new appliances, new programs or apps, inexperience with ICT, lack of ICT skills, and inadequate learning platforms ( Rahiem, 2020b ).

Students need to overcome all of these unexpected learning changes as quickly as possible ( Dhawan, 2020 ); A lack of certainty, insecurity, volatility, and reduced autonomy and self-directedness are typical feelings encountered by students during the pandemic crisis ( Germani, Buratta, Delvecchio, & Mazzeschi, 2020 ). Staying at home, worrying about being affected by the virus, changing their usual school routine, and not being able to socialize with friends affect their mental well-being ( Husky et al., 2020 , Rahiem, 2020a , Son et al., 2020 ). The pandemic brought the infection risk of death and led to intolerable psychological strain ( Cao et al., 2020 , Horesh and Brown, 2020 ). Stress has an impact on students' motivation ( Martin, Cayanus, Weber, & Goodboy, 2006 ). Some students with psychological hardiness will suffer a loss in motivation to perform and, even worse, a few will experience a severe state of depressed mood ( Cole, Feild, & Harris, 2004 ). All of these factors mean that students are often at risk of significant learning loss ( Dorn, Hancock, Sarakatsannis, & Viruleg, 2020 ).

However, the exploration of students' experiences conducted by the researcher showed that students remained positive and kept moving forward on their learning despite all the limitations they faced ( Rahiem, 2020a ). The students were still eagerly attending the online courses, working on assignments, and maintained their grades despite all the barriers and challenges they faced. In recognizing this, the researcher continued the study and aimed to explore what kept the student's motivated to learn amid all the difficulties and constraints of learning remotely online? The research discussed in this paper, in particular, is the subsequent issue of looking at the experiences of university students studying during the pandemic, discovering that they remained motivated, which led to further exploration into the source of this motivation. By understanding their motivation, we can learn what could be done to help students succeed despite all the limitations and help prepare them to be motivated during this time of difficulty.

This study used the case of students in Indonesia, but the lessons learned are applicable beyond the country's borders, especially developing countries. Technologically advanced countries are equipped with all the resources required for online education while developing countries only have full-fledged online education ( Ramij & Sultana, 2020 ). Many public institutions in developing countries also do not have access to structured online learning management systems (LMS) to promote contact between students and/or faculty members ( Sobaih, Hasanein, & Abu Elnasr, 2020 ).

2. Theory/Calculation

2.1. learning.

Vermunt and Donche (2017) conducted a systematic literature search to identify empirical and theoretical work research on students' learning patterns in higher education using the ILS inventory in the reference period (2004–2016). Their study recognized four qualitatively different learning patterns: reproduction-directed learning, meaning-directed learning, application-directed learning, and undirected learning. In reproduction-directed learning, students strive to recall the learning material to enable them to replicate it in a test. They memorize the learning materials and sequentially pass through them, step by step, rarely thinking about the relationship between larger units. Students pay a great deal of attention to the regulations made available by teachers and other external agents. The reason they study is to pass the exam or to test their ability.

Students who study in a meaningful-directed way take a deeper approach to learn. They try to grasp the significance of what they understand, explore relationships between different facts or views, structure learning materials into a greater whole and engage critically in what they know. They learn in a self-regulatory way and do not restrict themselves to prescribed materials. Students who study in an application-directed way strive to explore the connection between what they know and the outside world. They're trying to find examples of what they're doing and think about how they're going to apply what they're learning in reality. Students who study in an undirected way do not know how to handle their studies. This trend can also be seen with students transitioning from one type of schooling to another, e.g., from secondary to higher education, from undergraduate to graduate, or students from another country with different pedagogical methods. They continue to follow the approach they have used previously, as they do not yet know how to learn better. They attach great importance to fellow students and teachers to provide support and help them adapt.

In this study's initial research report, the researcher addressed how the change in learning methods had impacted students' learning habits. Students had been used to face-to-face conventional teaching methods and had not found it easy to adapt to remote online learning ( Rahiem, 2020a , Rahiem, 2020b ). The initial investigation results indicated that students appeared to have reproduction-directed learning patterns before the pandemic, in which they studied mainly for the examination. Because the students had previously been highly reliant on the teachers, they found it hard to adjust and could not catch up quickly with the learning when they were expected to study independently at home. They claimed that they felt that they were not learning because there was no lecturer to guide them in grasping the lesson ( Rahiem, 2020a ).

The study also showed that the university and its community were not well prepared to face an emergency, such as closing the campus due to a pandemic. The major and dramatic change in learning resulted in the students learning in a largely undirected way. As Vermunt and Donche (2017) explained above, students have lost their way of learning because they continued to study in a way that they had used before. They faced challenges in adapting to new circumstances: curriculums and lessons originally designed for conventional learning, the unprecedented use of technology in teaching and learning programs ( Rahiem, 2020b ), the need to study independently and the subsequent lack of structure ( Rahiem, 2020a ). Teachers' support in this situation is very important ( Vermunt & Donche, 2017 ). University learning should allow students to learn independently through various methods, with prior planning into how remote learning could be implemented if needed.

The biggest lesson from the COVID-19 crisis is that disasters or health crises could arise at any moment; therefore, prior preparation should enable society to face such threats, students to adapt, and trainers to be prepared with direct learning skills for emergencies. It is imperative that universities are better aware of the latest ICT available, as it is an alternative to schooling when learning is disrupted due to an emergency, and are better positioned to use these facilities in the future if another crisis is to occur.

However, the use of ICT for learning is not without problems. The students in this study explained that they missed getting the opportunity to socialize, develop relationships with peers, and work as a team on a class project during online learning ( Rahiem, 2020a , Rahiem, 2020b ). Millis (2010) described cooperative learning as one of ten high-impact learning activities that improve student learning. Haggis (2004) clarified that learning in higher education is social and relational; it should be operating adeptly in a realistic environment, learning problem-solving and rational thinking, language and interpersonal skills. Lotz-Sisitka, Wals, Kronlid, and McGarry (2015) argued that higher education needs to provide students with opportunities for engaged and experienced transformative praxis. For this reason, it is essential to explore alternative ways for students to develop skills to communicate and work together during online learning.