Kreitzberg Library for CGCS Students

Get started with research, what is a research strategy.

- Developing Your Research Topic

- Creating Keywords

- Constructing an Effective Search

- Refining or Broadening Your Search Results

- What is a Research Strategy Video Transcript PDF Transcript of the video, What is a Research Strategy?

- Next: Developing Your Research Topic >>

- Last Updated: Dec 22, 2022 2:32 PM

- URL: https://guides.norwich.edu/online/howtostart

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

The research process : a guide: strategy.

- Research Guides

- Finding Books

- Reference Books in Print

- Reference Works Online

- Finding Articles

- Managing Citations

Comprehensive research using scholarly resources is essential when writing a research paper. The following key resources will be helpful in determining a research strategy for any topic.

Determine a topic. If your topic is too broad, you may find too many sources. If it is too narrow, you may find very little information. If at all possible, try to discuss your topic with your GSI or professor prior to beginning the research process. When you have evaluated several of the basic sources recommended, it is always a good idea to REFINE YOUR TOPIC mid-way through the research process, by clarifying the scope or depth of the subject you are doing research on. See the section below for more information on refining your topic.

Standardize note-taking. Most students who are doing research for a paper consult various sources and often, half-way through the research process, forget which sources they've used, or have forgotten to take down important information such as dates, pages, and are never able to locate the source again. To save time, keep consistent notes about sources in one place. Consider using bibliographic software such as Endnote or Zotero.

Examine standard historical texts. General art historical texts can provide good overviews that cover many periods and artists. Bibliographies are usually included at the end of each chapter. Footnotes citing additional publications can also be useful.

Consult an encyclopedia. A general (Encyclopedia Britannica) or subject-specific (Grove Art Online) encyclopedia can provide an excellent overview of a topic, and often provide historical context. Encyclopedia articles are authored by scholars in the field, and often contain excellent bibliographies which can lead to additional sources.

Refining Your Topic

How to narrow a topic.

How do you know if your topic is too broad and needs to be narrowed?

- You are finding too much information on the topic – more sources exist than you can reasonably go through.

- You feel you are attempting to cover more information than you have room for in your paper.

Example: I would like to research Surrealist art.

This is a very broad subject which needs to be narrowed. When considering the categories below, we can narrow our topic to a specific Surrealist artist and one aspect of their work: 'Science in the Art of Remedios Varo'.

How to Broaden a Topic

How do you know if your topic is too narrow and needs to be broadened?

- You are finding very little information on the topic – you can't find many sources.

- Your topic is too new and not much research has been published on the topic yet.

Example: I want to research Thomas Campbell, a contemporary Bay Area artist.

This artist may not yet have a lot of sources published about his work or life. You may need to broaden your research to include the context within which he has worked, such as the Bay Area art in the 1990s+ and the Mission School artists group, and then focus on a aspect or event from this broader context.

Source Types

Dictionaries (general or subject-specific) can be useful for tracking down unknown or obscure words and terms, and for related terms. Examples include: A Concise Dictionary of the Avant-gardes ; The Edinburgh Dictionary of Modernism ; Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art .

Catalogues Raisonné present the complete works of an artist, often accompanied by a comprehensive bibliography. Search of these in UC Library Search and include 'catalogue raisonne' as a keyword.

Books Search by author, title, keyword, or subject in UC Library Search .

Art-related periodical indexes lead to both popular and scholarly articles in the journal literature. List of Indexes.

Reference Sources are sources such as handbooks, dictionaries and encyclopedias. Examples include: the Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism ; Bloomsbury International Encyclopedia of Surrealism ; Oxford Art Online . See our guide page on reference works for more information.

Book Reviews written by authorities in the field can help evaluate scholarship. Book reviews are often found in professional journals or a publication such as BookForum . You can also search in UC Library Search and include the keyword 'book review'.

Dissertations can be found in UC Library Search or Dissertations & Theses.

Exhibition catalogs contain scholarly essays and high quality images. Search in UC Library Search and include 'exhibition catalog' as a keyword.

Newspaper Articles can be useful when searching for current artists and exhibition reviews. Search in News Databases.

Primary Sources represent first-hand accounts, such as oral histories, personal interviews, an artist's archives, etc. The Bancroft Library, and the Berkeley Art Museum are excellent sources for finding original source material. Also see Calisphere for digitized collections from libraries and archives around California. See the Digital Public Library of America for digital collections from archives and libraries around the U.S. Also search WorldCat and limit to Archival Materials. You may also use an archive directory such as Archive Finder or ArchiveGrid to find archives with relevant holdings.

Videos/Film can provide documentaries on artists or works by artists and can be viewed in the Media Resources Center, Moffitt Library or viewed online via one of our online streaming collections such as Kanopy or Art and Architecture in Video . You may also search UC Library Search and limit 'material type' to 'video/film'. Also see our guide on art film & video .

Concept Mapping

- Next: Research Guides >>

- Last Updated: Jan 3, 2024 9:58 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchprocess_art

Writing a Research Strategy

This page is focused on providing practical tips and suggestions for preparing The Research Strategy, the primary component of an application's Research Plan along with the Specific Aims. The guidance on this page is primarily geared towards an R01-style application, however, much of it is useful for other grant types as well.

Developing the Research Strategy

The primary audience for your application is your peer review group. When writing your Research Strategy, your goal is to present a well-organized, visually appealing, and readable description of your proposed project and the rationale for pursuing it. Your writing should be streamlined and organized so your reviewers can readily grasp the information. If it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again. Add more emphasis by putting the text in bold , or bold italics . If writing is not your forte, get help. For more information, please visit W riting For Reviewers .

How to Organize the Research Strategy Section

How to organize a Research Strategy is largely up to the applicant. Start by following the NIH application instructions and guidelines for formatting attachments such as the research plan section.

It is generally structured as follows:

Significance

For Preliminary Studies (for new applications) or a Progress Report (for renewal and revision applications).

- You can either include preliminary studies or progress report information as a subsection of Approach or integrate it into any or all of the three main sections.

- If you do the latter, be sure to mark the information clearly, for example, with a bold subhead.

Helpful tips to consider when formatting:

- Organize using bold headers or an outline or numbering system—or both—that are used consistently throughout.

- Start each section with the appropriate header: Significance, Innovation, or Approach.

- Organize the Approach section around the Specific Aims.

For most applications, you need to address Rigor ous Study Design by describing the experimental design and methods you propose and how they will achieve robust and unbiased results. See the NIH guidance for elaboration on the 4 major areas of rigor and transparency emphasized in grant review. These requirements apply to research grant, career development, fellowship, and training applications.

Tips for Drafting Sections of the Research Strategy

Although you will emphasize your project's significance throughout the application, the Significance section should give the most details. The farther removed your reviewers are from your field, the more information you'll need to provide on basic biology, importance of the area, research opportunities, and new findings. Reviewing the potentially relevant study section rosters may give you some ideas as to general reviewer expertise. You will also need to describe the prior and preliminary studies that provide a strong scientific rationale for pursuing the proposed studies, emphasizing the strengths and weaknesses in the rigor and transparency of these key studies.

This section gives you the chance to explain how your application is conceptually and/or technically innovative. Some examples as to how you might do this could include but not limited to:

- Demonstrate the proposed research is new and unique, e.g., explores new scientific avenues, has a novel hypothesis, will create new knowledge.

- Explain how the proposed work can refine, improve, or propose a new application of an existing concept or method.

If your proposal is paradigm-shifting or challenges commonly held beliefs, be sure that you include sufficient evidence in your preliminary data to convince reviewers, including strong rationale, data supporting the approach, and clear feasibility. Your job is to make the reviewers feel confident that the risk is worth taking.

For projects predominantly focused on innovation and outside-the-box research, investigators may wish to consider mechanisms other than R01s for example (e.g., exploratory/developmental research (R21) grants, NIH Director's Pioneer Award Program (DP1), and NIH Director's New Innovator Award Program (DP2).

The Approach section is where the experimental design is described. Expect your assigned reviewers to scrutinize your approach: they will want to know what you plan to do, how you plan to do it, and whether you can do it. NIH data show that of the peer review criteria, approach has the highest correlation with the overall impact score. Importantly, elements of rigorous study design should be addressed in this section, such as plans for minimization of bias (e.g. methods for blinding and treatment randomization) and consideration of relevant biological variables. Likewise, be sure to lay out a plan for alternative experiments and approaches in case you get uninterpretable or surprising results, and also consider limitations of the study and alternative interpretations. Point out any procedures, situations, or materials that may be hazardous to personnel and precautions to be exercised. A full discussion on the use of select agents should appear in the Select Agent Research attachment. Consider including a timeline demonstrating anticipated completion of the Aims.

Here are some pointers to consider when organizing your Approach section:

- Enter a bold header for each Specific Aim.

- Under each aim, describe the experiments.

- If you get result X, you will follow pathway X; if you get result Y, you will follow pathway Y.

- Consider illustrating this with a flowchart.

Preliminary Studies

If submitting a new application to a NOFO that allows preliminary data, it is strongly encouraged to include preliminary studies. Preliminary studies demonstrate competency in the methods and interpretation. Well-designed and robust preliminary studies also serve to provide a strong scientific rationale for the proposed follow-up experiments. Reviewers also use preliminary studies together with the biosketches to assess the investigator review criterion, which reflects the competence of the research team. Provide alternative interpretations to your data to show reviewers you've thought through problems in-depth and are prepared to meet future challenges. As noted above, preliminary data can be put anywhere in the Research Strategy, but just make sure reviewers will be able to distinguish it from the proposed studies. Alternatively, it can be a separate section with its own header.

Progress Reports

If applying for a renewal or a revision (a competing supplement to an existing grant), include a progress report for reviewers.

Create a header so reviewers can easily find it and include the following information:

- Project period beginning and end dates.

- Summary of the importance and robustness of the completed findings in relation to the Specific Aims.

- Account of published and unpublished results, highlighting progress toward achieving your Specific Aims.

Other Helpful Tips

Referencing publications.

References show breadth of knowledge of the field and provide a scientific foundation for your application. If a critical work is omitted, reviewers may assume the applicant is not aware of it or deliberately ignoring it.

Throughout the application, reference all relevant publications for the concepts underlying your research and your methods. Remember the strengths and weaknesses in the rigor of the key studies you cite for justifying your proposal will need to be discussed in the Significance and/or Approach sections.

Read more about Bibliography and References Cited at Additional Application Elements .

Graphics can illustrate complex information in a small space and add visual interest to your application. Including schematics, tables, illustrations, graphs, and other types of graphics can enhance applications. Consider adding a timetable or flowchart to illustrate your experimental plan, including decision trees with alternative experimental pathways to help your reviewers understand your plans.

Video may enhance your application beyond what graphics alone can achieve. If you plan to send one or more videos, you'll need to meet certain requirements and include key information in your Research Strategy. State in your cover letter that a video will be included in your application (don't attach your files to the application). After you apply and get assignment information from the Commons, ask your assigned Scientific Review Officer (SRO) how your business official should send the files. Your video files are due at least one month before the peer review meeting.

However, you can't count on all reviewers being able to see or hear video, so you'll want to be strategic in how you incorporate it into your application by taking the following steps:

- Caption any narration in the video.

- Include key images from the video

- Write a description of the video, so the text would make sense even without the video.

Tracking for Your Budget

As you design your experiments, keep a running tab of the following essential data:

- Who. A list of people who will help (for the Key Personnel section later).

- What. A list of equipment and supplies for the experiments

- Time. Notes on how long each step takes. Timing directly affects the budget as well as how many Specific Aims can realistically be achieved.

Jotting this information down will help when Creating a Budget and complete other sections later.

Review and Finalize Your Research Plan

Critically review the research plan through the lens of a reviewer to identify potential questions or weak spots.

Enlist others to review your application with a fresh eye. Include people who aren't familiar with the research to make sure the proposed work is clear to someone outside the field.

When finalizing the details of the Research Strategy, revisit and revise the Specific Aims as needed. Please see Writing Specific Aims .

comments Want to contact NINDS staff? Please visit our Find Your NINDS Program Officer page to learn more about contacting Program Officer, Grants Management Specialists, Scientific Review Officers, and Health Program Specialists.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

VII. Researched Writing

7.3 Developing a Research Strategy

Deborah Bernnard; Greg Bobish; Jenna Hecker; Irina Holden; Allison Hosier; Trudi Jacobson; Tor Loney; Daryl Bullis; and Sarah LeMire

Sarah’s art history professor just assigned the course project and Sarah is delighted that it isn’t the typical research paper. Rather, it involves putting together a website to help readers understand a topic. It will certainly help Sarah get a grasp on the topic herself. Learning by attempting to teach others, she agrees, might be a good idea. The professor wants the website to be written for people who are interested in the topic and with backgrounds similar to the students in the course. Sarah likes that a target audience is defined, and since she has a good idea of what her friends might understand and what they would need more help with, she thinks it will be easier to know what to include in her site…well, at least easier than writing a paper for an expert like her professor.

An interesting feature of this course is that the professor has formed the students into teams. Sarah wasn’t sure she liked this idea at the beginning, but it seems to be working out okay. Sarah’s team has decided that their topic for this website will be 19 th century women painters. Her teammate Chris seems concerned: “Isn’t that an awfully big topic?” The team checks with the professor who agrees they would be taking on far more than they could successfully explain on their website. He suggests they develop a draft thesis statement to help them focus, and after several false starts, they come up with:

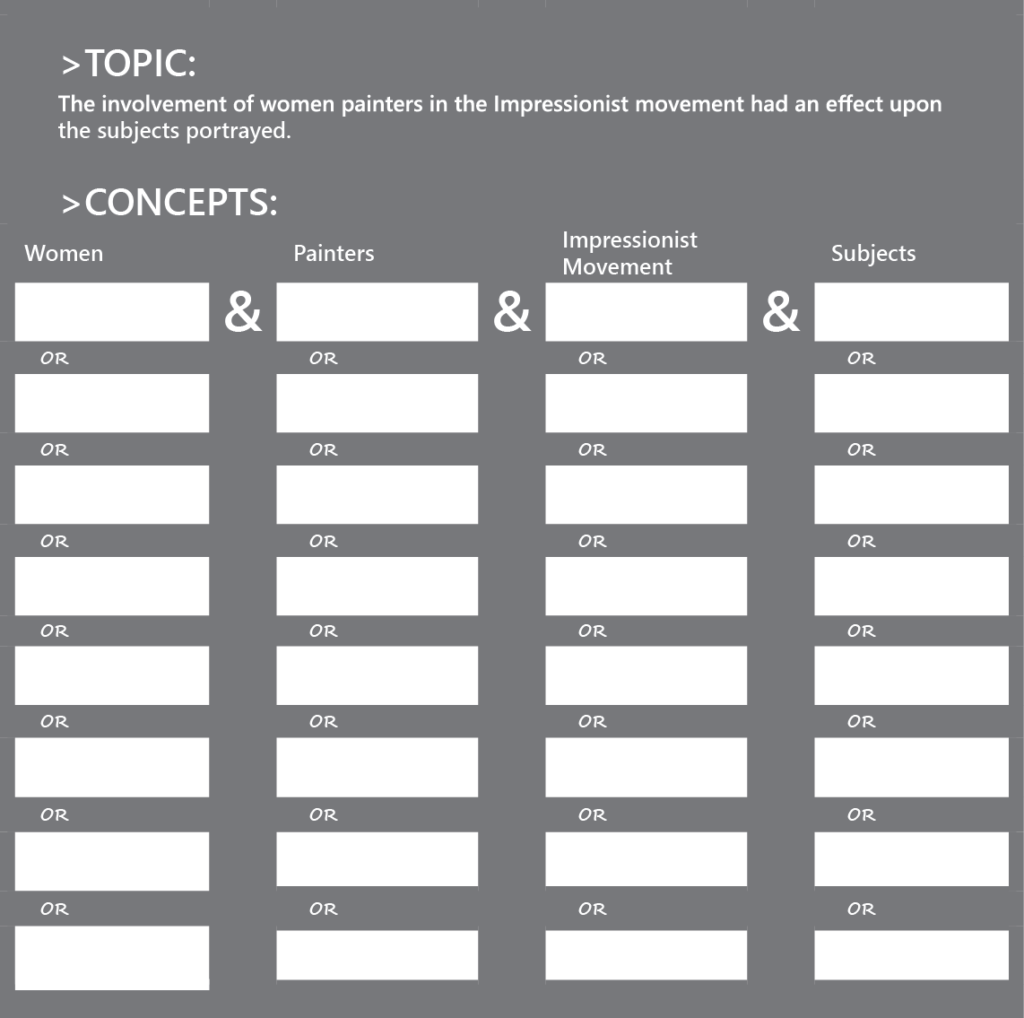

The involvement of women painters in the Impressionist movement had an effect upon the subjects portrayed.

They decide this sounds more manageable. Because Sarah doesn’t feel comfortable on the technical aspects of setting up the website, she offers to start locating resources that will help them to develop the site’s content. The next time the class meets, Sarah tells her teammates what she has done so far:

“I thought I’d start with some scholarly sources, since they should be helpful, right? I put a search into the online catalog for the library, but nothing came up! The library should have books on this topic, shouldn’t it? I typed the search in exactly as we have it in our thesis statement. That was so frustrating. Since that didn’t work, I tried Google, and put in the search. I got over 8 million results, but when I looked over the ones on the first page, they didn’t seem very useful. One was about the feminist art movement in the 1960s, not during the Impressionist period. The results all seemed to have the words I typed highlighted, but most really weren’t useful. I am sorry I don’t have much to show you. Do you think we should change our topic?”

Alisha suggests that Sarah talk with a reference librarian . She mentions that a librarian came to talk to one of her other classes about doing research, and it was really helpful. Alisha thinks that maybe Sarah shouldn’t have entered the entire thesis statement as the search, and maybe she should have tried databases to find articles. The team decides to brainstorm all the search tools and resources they can think of.

Here’s what they came up with:

Brainstormed List of Search Tools and Resources

Based on your experience, do you see anything you would add?

Sarah and her team think that their list is pretty good. They decide to take it further and list the advantages and limitations of each search tool, at least as far as they can determine.

Brainstormed Advantages and Disadvantages of Search Tools and Resources

Alisha suggests that Sarah should show the worksheet to a librarian and volunteers to go with her. The librarian, Mr. Harrison, says they have made a really good start, but he can fill them in on some other search strategies that will help them to focus on their topic. He asks if Sarah and Alisha would like to learn more.

Let’s step back from this case study and think about the elements that someone doing research should plan before starting to enter search terms in Google, Wikipedia, or even a scholarly database. There is some preparation you can do to make things go much more smoothly than they have for Sarah.

Self-Reflection

As you work through your own research quests, it is very important to be self-reflective. Consider:

- What do you really need to find?

- Do you need to learn more about the general subject before you can identify the focus of your search?

- How thoroughly did you develop your search strategy?

- Did you spend enough time finding the best tools to search?

- What is going really well, so well that you’ll want to remember to do it in the future?

Another term for what you are doing is metacognition, or thinking about your thinking. Reflect on what Sarah is going through. Does some of it sound familiar based on your own experiences? You may already know some of the strategies presented here. Do you do them the same way? How does it work? What pieces are new to you? When might you follow this advice? Don’t just let the words flow over you; rather, think carefully about the explanation of the process. You may disagree with some of what you read. If you do, follow through and test both methods to see which provides better results.

Selecting Search Tools

After you have thought the planning process through more thoroughly, think about the best place to find information for your topic and for the type of paper. Part of planning to do research is determining which search tools will be the best ones to use. This applies whether you are doing scholarly research or trying to answer a question in your everyday life, such as what would be the best place to go on vacation. “Search tools” might be a bit misleading since a person might be the source of the information you need. Or it might be a web search engine , a specialized database , an association—the possibilities are endless. Often people automatically search Google first, regardless of what they are looking for. Choosing the wrong search tool may just waste your time and provide only mediocre information, whereas other sources might provide really spot-on information and quickly, too. In some cases, a carefully constructed search on Google, particularly using the advanced search option, will provide the necessary information, but other times it won’t. This is true of all sources: make an informed choice about which ones to use for a specific need.

So, how do you identify search tools? Let’s begin with a first-rate method. For academic research, talking with a librarian or your professor is a great start. They will direct you to those specialized tools that will provide access to what you need. If you ask a librarian for help, they may also show you some tips about searching in the resources. This section will cover some of the generic strategies that will work in many search tools, but a librarian can show you very specific ways to focus your search and retrieve the most useful items.

If neither your professor nor a librarian is available when you need help, take a look at the TAMU Libraries website . There is a Help button in the top right corner of the website that will direct you to assistance via phone, chat, text, and email. Under the Guides button, you’ll find class- and subject-related guides that list useful databases and other resources for particular classes and majors to assist researchers. There is also a directory of the databases the library subscribes to and the subjects they cover. Take advantage of the expertise of librarians by using such guides. Novice researchers usually don’t think of looking for this type of help and, as a consequence, often waste time.

When you are looking for non-academic material, consider who cares about this type of information. Who works with it? Who produces it or the help guides for it? Some sources are really obvious and you are already using them—for example, if you need information about the weather in London three days from now, you might check Weather.com for London’s forecast. You don’t go to a library (in person or online), and you don’t do a research database search. For other information you need, think the same way. Are you looking for anecdotal information on old railroads? Find out if there is an organization of railroad buffs. You can search on the web for this kind of information or, if you know about and have access to it, you could check the Encyclopedia of Associations. This source provides entries for all U.S. membership organizations which can quickly lead you to a potentially wonderful source of information. Librarians can point you to tools like these.

Consider Asking an Expert

Have you thought about using people, not just inanimate sources, as a way to obtain information? This might be particularly appropriate if you are working on an emerging topic or a topic with local connections. There are a variety of reasons that talking with someone will add to your research.

For personal interactions, there are other specific things you can do to obtain better results. Do some background work on the topic before contacting the person you hope to interview. The more familiarity you have with your topic and its terminology, the easier it will be to ask focused questions. Focused questions are important if you want to get into the meat of what you need. Asking general questions because you think the specifics might be too detailed rarely leads to the best information. Acknowledge the time and effort someone is taking to answer your questions, but also realize that people who are passionate about subjects enjoy sharing what they know. Take the opportunity to ask experts about sources they would recommend. One good place to start is with the librarians at the Texas A&M University Libraries. Visit the library information page for details on how to contact a librarian. [1]

Determining Search Concepts and Keywords

Once you’ve selected some good resources for your topic, and possibly talked with an expert, it is time to move on to identify words you will use to search for information on your topic in various databases and search engines. This is sometimes referred to as building a search query . When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Don’t enter an entire sentence or a full question. Different databases and search engines process such queries in different ways, but many look for the entire phrase you enter as a complete unit rather than the component words. While some will focus on just the important words, such as Sarah’s Google search that you read about earlier in this chapter, the results are often still unsatisfactory. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic. In addition, think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term doesn’t produce any or enough results. This may sound strange since, if you are looking for information using a Web search engine, you almost always get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

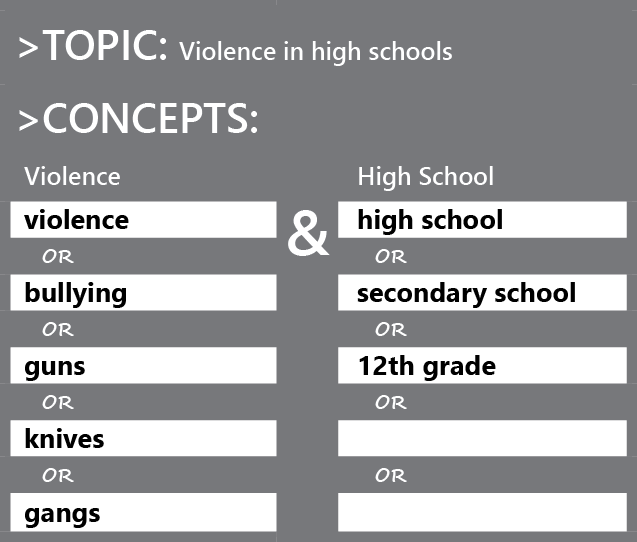

The worksheet in Figure 7.3.1 [2] is an example of a process you can use to come up with search terms. It illustrates how you might think about the topic of violence in high schools. Notice that this exact phrase is not what will be used for the search. Rather, it is a starting point for identifying the terms that will eventually be used.

Example Search Term Brainstorming Worksheet

Now, use a clean copy of the same worksheet (Figure 7.3.2) [3] to think about the topic Sarah’s team is working on. How might you divide their topic into concepts and then search terms? Keep in mind that the number of concepts will depend on what you are searching for and that the search terms may be synonyms or narrower terms. Occasionally, you may be searching for something very specific, and in those cases, you may need to use broader terms as well. Jot down your ideas, then compare what you have written to the information on the second, completed worksheet (Figure 7.3.3) [4] and identify three differences.

Boolean Operators

Once you have the concepts you want to search, you need to think about how you will enter them into the search box. Often, but not always, Boolean operators will help you. You may be familiar with Boolean operators as they provide a way to link terms. There are three Boolean operators: AND , OR , and NOT . (Note: Some databases require Boolean operators to be in all caps while others will accept the terms in either upper or lower case.

We will start by capturing the ideas of the women creating the art. We will use women painters and women artists as the first step in our sample search. You could do two separate searches by typing one or the other of the terms into the search box of whatever tool you are using:

women painters women artists

You would end up with two separate results lists and have the added headache of trying to identify unique items from the lists. You could also search on the phrase:

women painters AND women artists

But once you understand Boolean operators, that last strategy won’t make as much sense as it seems to. The first Boolean operator is AND. AND is used to get the intersection of all the terms you wish to include in your search. With this example,

you are asking that the items you retrieve have both of those terms. If an item only has one term, it won’t show up in the results. This is not what the searcher had in mind—she is interested in both artists and painters because she doesn’t know which term might be used. She doesn’t intend that both terms have to be used. Let’s go on to the next Boolean operator, which will help us out with this problem.

OR is used when you want at least one of the terms to show up in the search results. If both do, that’s fine, but it isn’t a condition of the search. So OR makes a lot more sense for this search:

women painters OR women artists

Now, if you want to get fancy with this search, you could use both AND as well as OR :

women AND (painters OR artists)

The parentheses mean that these two concepts, painters and artists, should be searched as a unit, and the search results should include all items that use one word or the other. The results will then be limited to those items that contain the word women . If you decide to use parentheses for appropriate searches, make sure that the items contained within them are related in some way. With OR , as in our example, it means either of the terms will work. With AND , it means that both terms will appear in the document.

Type both of the searches above in Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) and compare the results.

- Were they the same?

- If not, can you determine what happened?

- Which results list looked better?

Here is another example of a search string using both parentheses and two Boolean operators:

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens)

In this search, you are looking for entrepreneurial initiatives connected with people in their teens. Because there are so many ways to categorize this age group, it makes sense to indicate that either of these terms should appear in the results along with entrepreneurship.

The search string above isn’t perfect. Can you pick out two problems with the search terms?

The third Boolean operator, NOT , can be problematic. NOT is used to exclude items from your search. If you have decided, based on the scope of the results you are getting, to focus only on a specific aspect of a topic, use NOT , but be aware that items are being lost in this search.

For example, if you entered

entrepreneurship AND (adolescents OR teens) NOT adults

you might lose some good results.

Why might you lose some good results using the search above?

Other Helpful Search Techniques

Using Boolean operators isn’t the only way you can create more useful searches. In this section, we will review several others.

In this search:

entrepreneurs AND (adolescents OR teens)

you might think that the items that are retrieved from the search can refer to entrepreneurs and to terms from the same root, like entrepreneurship. But because computers are very literal, they usually look for the exact terms you enter. While some search engines like Google are moving beyond this model, library databases tend to require more precision. Truncation, or searching on the root of a word and whatever follows, is how you can tell the database to do this type of search.

So, if you search on:

entrepreneur * AND (adolescents OR teens)

You will get items that refer to entrepreneur , but also entrepreneurship .

Look at these examples:

adolescen * educat *

Think of two or three words you might retrieve when searching on these roots. It is important to consider the results you might get and alter the root if need be. An example of this is polic * . Would it be a good idea to use this root if you wanted to search on policy or policies ? Why or why not?

In some cases, a symbol other than an asterisk is used. To determine what symbol to use, check the help section in whatever resource you are using. The topic should show up under the truncation or stemming headings.

Phrase Searches

Phrase searches are particularly useful when searching the web. If you put the exact phrase you want to search in quotation marks, you will only get items with those words as a phrase and not items where the words appear separately in a document, website, or other resource. Your results will usually be fewer, although surprisingly, this is not always the case.

Try these two searches in the search engine of your choice:

- “ essay exam”

Was there a difference in the quality and quantity of results?

If you would like to find out if the database or search engine you are using allows phrase searching and the conventions for doing so, search the help section. These help tools can be very, well, helpful!

Advanced Searches

Advanced searching allows you to refine your search query and prompts you for ways to do this. Consider the basic Google search box. It is very minimalistic, but that minimalism is deceptive. It gives the impression that searching is easy and encourages you to just enter your topic without much thought to get results. You certainly do get many results, but are they really good results? Simple search boxes do many searchers a disfavor. There is a better way to enter searches.

Advanced search screens show you many of the options available to you to refine your search and, therefore, get more manageable numbers of better items. Many web search engines include advanced search screens, as do databases for searching research materials. Advanced search screens will vary from resource to resource and from web search engine to research database, but they often let you search using:

- Implied Boolean operators (for example, the “all the words” option is the same as using the Boolean AND );

- Limiters for date, domain (.edu, for example), type of resource (articles, book reviews, patents);

- Field (a field is a standard element, such as title of publication or author’s name);

- Phrase (rather than entering quote marks) Let’s see how this works in practice.

Practical Application: Google Searches

Go to the advanced search option in Google. You can find it at http://www.google.com/advanced_search

Take a look at the options Google provides to refine your search. Compare this to the basic Google search box. One of the best ways you can become a better searcher for information is to use the power of advanced searches, either by using these more complex search screens or by remembering to use Boolean operators, phrase searches, truncation, and other options available to you in most search engines and databases.

While many of the text boxes at the top of the Google Advanced Search page mirror concepts already covered in this section (for example, “this exact word or phrase” allows you to omit the quotes in a phrase search), the options for narrowing your results can be powerful. You can limit your search to a particular domain (such as .edu for items from educational institutions) or you can search for items you can reuse legally (with attribution, of course!) by making use of the “usage rights” option. However, be careful with some of the options as they may excessively limit your results. If you aren’t certain about a particular option, try your search with and without using it and compare the results. If you use a search engine other than Google, check to see if it offers an advanced search option: many do.

Subject Headings

In the section on advanced searches, you read about field searching. To explain further, if you know that the last name of the author whose work you are seeking is Wood, and that he worked on forestry-related topics, you can do a far better search using the author field. Just think what you would get in the way of results if you entered a basic search such as forestry AND wood . It is great to use the appropriate Boolean operator, but oh, the results you will get! But what if you specified that wood had to show up as part of the author’s name? This would limit your results quite a bit.

So what about forestry ? Is there a way to handle that using a field search? The answer is yes. Subject headings are terms that are assigned to items to group them. An example is cars—you could also call them autos, automobiles, or even more specific labels like SUVs or vans. You might use the Boolean operator OR and string these all together. But if you found out that the sources you are searching use automobiles as the subject heading, you wouldn’t have to worry about all these related terms, and could confidently use their subject heading and get all the results, even if the author of the piece uses cars and not automobiles .

How does this work? In many databases, a person called an indexer or cataloger scrutinizes and enters each item. This person performs helpful, behind-the-scenes tasks such as assigning subject headings, age levels, or other indicators that make it easier to search very precisely. An analogy is tagging, although indexing is more structured than tagging. If you have tagged items online, you know that you can use any terms you like and that they may be very different from someone else’s tags. With indexing, the indexer chooses from a set group of terms. Obviously, this precise indexing isn’t available for web search engines—it would be impossible to index everything on the web. But if you are searching in a database, make sure you use these features to make your searches more precise and your results lists more relevant. You also will definitely save time.

You may be thinking that this sounds good. Saving time when doing research is a great idea. But how will you know what subject headings exist so you can use them? Here is a trick that librarians use. Even librarians don’t know what terms are used in all the databases or online catalogs that they use, so a librarian’s starting point isn’t very far from yours. But they do know to use whatever features a database provides to do an effective search. They find out about them by acting like a detective.

You’ve already thought about the possible search terms for your information needs. Enter the best search strategy you developed which might use Boolean operators or truncation. Scan the results to see if they seem to be on topic. If they aren’t, figure out what results you are getting that just aren’t right and revise your search. Terms you have searched on often show up in bold face type so they are easy to pick out. Besides checking the titles of the results, read the abstracts (or summaries), if there are any. You may get some ideas for other terms to use. But if your results are fairly good, scan them with the intent to find one or two items that seem to be precisely what you need. Get to the full record (or entry), where you can see all the details entered by the indexers. Figure 7.3.4 [5] is an example from the Texas A&M University Libraries’ Quick Search, but keep in mind that the catalog or database you are using may have entries that look very different.

Once you have the “full” record (which does not refer to the full text of the item, but rather the full descriptive details about the book, including author, subjects, date, and place of publication, and so on), look at the subject headings and see what words are used. They may be called descriptors or some other term, but they should be recognizable as subjects. They may be identical to the terms you entered but if not, revise your search using the subject heading words. The result list should now contain items that are relevant for your needs.

It is tempting to think that once you have gone through all the processes around the circle, as seen in the diagram in Figure 7.3.5 [6] , your information search is done and you can start writing. However, research is a recursive process. You don’t start at the beginning and continue straight through until you end at the end. Once you have followed this planning model, you will often find that you need to alter or refine your topic and start the process again, as seen here:

![a research strategy is determined by Circle divided into four with a box at each corner. Circle part 1: Refine topic [Box: Narrow or broaden scope, Select new aspect of topic] Circle part 2: Concepts [Box: Revise existing concepts, Add or eliminate concepts] Circle part 3: Determine relationships [Box: Boolean operators, Phrase searching] Circle part 4: Variations and refinements [Box: Truncations, field searching, subject headings]](https://oer.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/61/2021/10/image4.png)

This revision process may happen at any time before or during the preparation of your paper or other final product. The researchers who are most successful do this, so don’t ignore opportunities to revise.

So let’s return to Sarah and her search for information to help her team’s project. Sarah realized she needed to make a number of changes in the search strategy she was using. She had several insights that definitely led her to some good sources of information for this particular research topic. Can you identify the good ideas she implemented?

This section contains material from:

Bernnard, Deborah, Greg Bobish, Jenna Hecker, Irina Holden, Allison Hosier, Trudi Jacobson, Tor Loney, and Daryl Bullis. The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook , edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014. http://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License .

- https://library.tamu.edu ↵

- “Concept Brainstorming,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook , eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License . ↵

- “Blank Concept Brainstorming Worksheet,” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook , eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License . ↵

- “Completed Concept Brainstorming Worksheet” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook , eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License . ↵

- “Full Record Entry for a Book” is a reproduction from July 2019 of a Texas A&M University Libraries catalog entry from the Texas A&M University Libraries Quick Search. https://libcat.tamu.edu/vwebv/searchBasic. ↵

- “Planning Model” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook , eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License . ↵

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses .

When something is described as scholarly, that means that has been written by and for the academic community. The term scholarly is commonly used as shorthand to indicate that information that has been peer reviewed or examined by other experts of the same academic field or discipline. Sometimes, the terms academic, scholarly, and peer reviewed are confused as synonyms; peer reviewed is a narrower term referring to an item that has been reviewed by experts in the field prior to publication, while academic is a broader term that also includes works that are written by and for academics, but that have not been peer reviewed.

A library catalog is a database of records for the items a library holds and/or to which it has access. Searching a library catalog is not the same as searching the web, even though you may see a similar search box for both tools. Library catalog searches can return information that you would not find on the open web, and the searching process will likely take longer to refine.

A librarian who specializes in helping the public find information. In academic librarians, reference librarians often have subject specialties.

A database is an organized collection of data in a digital format. Library research databases are often composed of academic publications like journal articles and book chapters, although there are also specialty databases that have data like engineering specifications or world news articles.

An online software tool used to find information on the web. Many popular online search engines return query results by using algorithms to return probable desired information.

A short account or telling of an incident or story, either personal or historical; anecdotal evidence is frequently found in the form of a personal experience rather than objective data or widespread occurrence.

Query: to ask a question or make an inquiry, often with some amount of skepticism involved.

With relation to a database, a query is a call for results. Most times a query is a search term entered into a search box.

A full record for a library item is all of the bibliographic information entered into the catalog for that particular work. Common entries in a full record will include the name of the work, the author, the publisher, the place of publication, the number of pages, the format, subject terms, and sometimes chapter titles.

A form of returning back to or reoccurrence, usually as a procedure or practice that can be repeated.

7.3 Developing a Research Strategy Copyright © 2022 by Deborah Bernnard; Greg Bobish; Jenna Hecker; Irina Holden; Allison Hosier; Trudi Jacobson; Tor Loney; Daryl Bullis; and Sarah LeMire is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Cookies & Privacy

- GETTING STARTED

- Introduction

- FUNDAMENTALS

Getting to the main article

Choosing your route

Setting research questions/ hypotheses

Assessment point

Building the theoretical case

Setting your research strategy

Data collection

Data analysis

Once you have a good understanding of the theoretical components involved in your main journal article , your choice of route , and the approach within that route, it is time to set the research strategy you will use in your dissertation.

Your dissertation guidelines may refer to this stage of your dissertation as setting the research design , research methodology , or even research methods , but these are just three of the components that can make up a research strategy . We prefer to refer to your setting a research strategy because all the choices you make concerning how you implement (i.e., operationalize ) your dissertation should be strategic . This is because the research strategy you implement in your dissertation consists of a number of components , and these components are all interrelated; that is, the choice of one component (e.g., your research design ) influences the next (e.g., your research methods ).

Whilst it is best to consult your dissertation guidelines to see which components you are required to include, your research strategy generally requires that you are able to describe , explain and justify :

the research paradigm that you are following;

the quantitative research design that guides how you have set up your research;

the quantitative research method(s) that determine how you went about collecting your data;

the sampling strategy you used to guide what data you collected;

the data analysis techniques that you used to answer your research questions/hypotheses;

how you ensured the research quality of your findings; and

your approach towards research ethics .

The extent to which the nature of these components (e.g., the different types of research method available) will vary between the main journal article and your dissertation will depend on the route you are following, and the approach within that route.

Broadly speaking, you will be able to rely more heavily on the research strategy used in the main journal article when setting your research strategy if you have taken on Route A: Duplication compared with Route B: Generalisation , and certainly, Route C: Extension , which typically requires more independent thought and planning. However, there are certain expectations, usually set out in dissertation guidelines, which require certain components of research strategy to be discussed, even when these were not addressed in your main journal article. Therefore, you need to understand (a) what these components mean, and (b) not only the explicitly mentioned components in your main journal article, but also those that are implicit, but not mentioned, and those that may have been intentionally left out.

In order to set your research strategy, you will need to (a) consider the route you are following, and the approach within that route, (b) research relevant theory about the various components of research strategy, (c) devise your research strategy, and (d) address practical requirements associated with this research strategy. When you work through this STAGE SIX , bear in mind that it can be one of the easiest places within the dissertation process to gain or lose marks. It can also be challenging, and you may need to spend time reading through relevant theory. However, we have many articles within the Research Strategy section of the Fundamentals part of Lærd Dissertation to help you. To start the process, work through the following seven steps , each of which address a different component involved in setting your research strategy:

- STEP ONE: Research paradigm

- STEP TWO: Research design

- STEP THREE: Research methods

- STEP FOUR: Sampling strategy

- STEP FIVE: Research quality

- STEP SIX: Research ethics

- STEP SEVEN: Data analysis techniques

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Research strategy guide for finding quality, credible sources

Strategies for finding academic studies and other information you need to give your stories authority and depth

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Keely Wilczek, The Journalist's Resource May 20, 2011

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/home/research-strategy-guide/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Knowing how to conduct deeper research efficiently and effectively is a critical skill for journalists — especially in the information age. It is, like other facets of the profession such as interviewing, a matter of practice and establishing good habits. And once you find a successful routine for information-gathering, it will pay dividends time and again.

Journalists need to be able to do many kinds of research. This article focuses on creating a research strategy that will help you find academic studies and related scholarly information. These sources can, among other things, give your stories extra authority and depth — and thereby distinguish your work. You can see examples of such studies — and find many relevant ones for your stories — by searching the Journalist’s Resource database . But that is just a representative sample of what exists in the research world.

The first step is to create a plan for seeking the information you need. This requires you to take time initially and to proceed with care, but it will ultimately pay off in better results. The research strategy covered in this article involves the following steps:

Get organized

Articulate your topic, locate background information.

- Identify your information needs

List keywords and concepts for search engines and databases

Consider the scope of your topic, conduct your searches, evaluate the information sources you found, analyze and adjust your research strategy.

Being organized is an essential part of effective research strategy. You should create a record of your strategy and your searches. This will prevent you from repeating searches in the same resources and from continuing to use ineffective terms. It will also help you assess the success or failure of your research strategy as you go through the process. You also may want to consider tracking and organizing citations and links in bibliographic software such as Zotero . (See this helpful resource guide about using Zotero.)

Next, write out your topic in a clear and concise manner. Good research starts with a specific focus.

For example, let’s say you are writing a story about the long-range health effects of the explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant based on a study published in Environmental Health Perspectives titled, “The Chernobyl Accident 20 Years On: An Assessment of the Health Consequences and the International Response.” (The study is summarized in Journalist’s Resource here .)

A statement of your topic might be, “Twenty years after the Chernobyl disaster, scientists are still learning the affects of the accident on the health of those who lived in the surrounding area and their descendants.”

If you have a good understanding of the Chernobyl disaster, proceed to the next step, “Identify the information you need.” If not, it’s time to gather background information. This will supply you with the whos and the whens of the topic. It will also provide you with a broader context as well as the important terminology.

Excellent sources of background information are subject-specific encyclopedias and dictionaries, books, and scholarly articles, and organizations’ websites. You should always consult more than one source so you can compare for accuracy and bias.

For your story about Chernobyl, you might want to consult some of the following sources:

- Frequently Asked Chernobyl Questions , International Atomic Agency

- Chernobyl Accident 1986 , World Nuclear Association

- Chernobyl: Consequences of the Catastrophe for People and the Environment , New York Academy of Sciences, 2009.

- “Chernobyl Disaster,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last updated 2013.

Identify the information you need

What information do you need to write your story? One way to determine this is to turn your overall topic into a list of questions to be answered. This will help you identify the type and level of information you need. Some possible questions on consequences of the Chernobyl accident are:

- What are the proven health effects?

- What are some theorized health effects?

- Is there controversy about any of these studies?

- What geographic area is being studied?

- What are the demographic characteristics of the population being studied?

- Was there anything that could have been done at the time to mitigate these effects?

Looking at these questions, it appears that scientific studies and scholarly articles about those studies, demographic data, disaster response analysis, and government documents and publications from the Soviet Union and Ukraine would be needed.

Now you need to determine what words you will use to enter in the search boxes within resources. One way to begin is to extract the most important words and phrases from the questions produced in the previous step. Next, think about alternative words and phrases that you might use. Always keep in mind that different people may write or talk about the same topic in different ways. Important concepts can referred to differently or be spelled differently depending on country of origin or field of study.

For the Chernobyl health story, some search keyword options are: “Chernobyl,” “Chornobyl”; “disaster,” “catastrophe,” “explosion”; “health,” “disease,” “illness,” “medical conditions”; “genetic mutation,” “gene mutation,” “germ-line mutation,” “hereditary disease.” Used in different combinations, these can unearth a wide variety of resources.

Next you should identify the scope of your topic and any limitations it puts on your searches. Some examples of limitations are language, publication date, and publication type. Every database and search engine will have its own rules so you may need to click on an advanced search option in order to input these limitations.

It is finally time to start looking for information but identifying which resources to use is not always easy to do. First, if you are part of an organization, find out what, if any, resources you have access to through a subscription. Examples of subscription resources are LexisNexis and JSTOR. If your organization does not provide subscription resources, find out if you can get access to these sources through your local library. Should you not have access to any subscription resources appropriate for your topic, look at some of the many useful free resources on the internet.

Here are some examples of sources for free information:

- PLoS , Public Library of Science

- Google Scholar

- SSRN , Social Science Research Network

- FDsys , U.S. Government documents and publications

- World Development Indicators , World Bank

- Pubmed , service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine

More quality sites, and search tips, are here among the other research articles at Journalist’s Resource.

As you only want information from the most reliable and suitable sources, you should always evaluate your results. In doing this, you can apply journalism’s Five W’s (and One H):

- Who : Who is the author and what are his/her credentials in this topic?

- What: Is the material primary or secondary in nature?

- Where: Is the publisher or organization behind the source considered reputable? Does the website appear legitimate?

- When: Is the source current or does it cover the right time period for your topic?

- Why: Is the opinion or bias of the author apparent and can it be taken into account?

- How: Is the source written at the right level for your needs? Is the research well-documented?

Were you able to locate the information you needed? If not, now it is time to analyze why that happened. Perhaps there are better resources or different keywords and concepts you could have tried. Additional background information might supply you with other terminology to use. It is also possible that the information you need is just not available in the way you need it and it may be necessary to consult others for assistance like an expert in the topic or a professional librarian.

Keely Wilczek is a research librarian at the Harvard Kennedy School. Tags: training

About The Author

Keely Wilczek

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

A systematic review to determine the effect of strategies to sustain chronic disease prevention interventions in clinical and community settings: study protocol

- Edward Riley-Gibson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0829-7913 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Alix Hall 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Adam Shoesmith 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Luke Wolfenden 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Rachel C. Shelton 5 ,