- 1865-1925: Hunger in the Industrial City

- 1929-1940: America in Crisis and Recovery

- 1945-1965: WWII and the Paradoxes of the Postwar Era

- 1955-1980: The Fight for the Right for Food

- 1975-1996: The Unmaking of the Great Society

- 1997-Present: How It Is — And How It Should Be

- Museum Lobby

- The Wishing Tree

- The SNAP Café

- Terrace Restaurant

- Get Involved

- Book a Tour

- Leave your Wish

- Patron Program

- Educational Curriculum

- The Hunger Museum

- About MAZON

- In the News

Carlos Bulosan, “Freedom From Want”

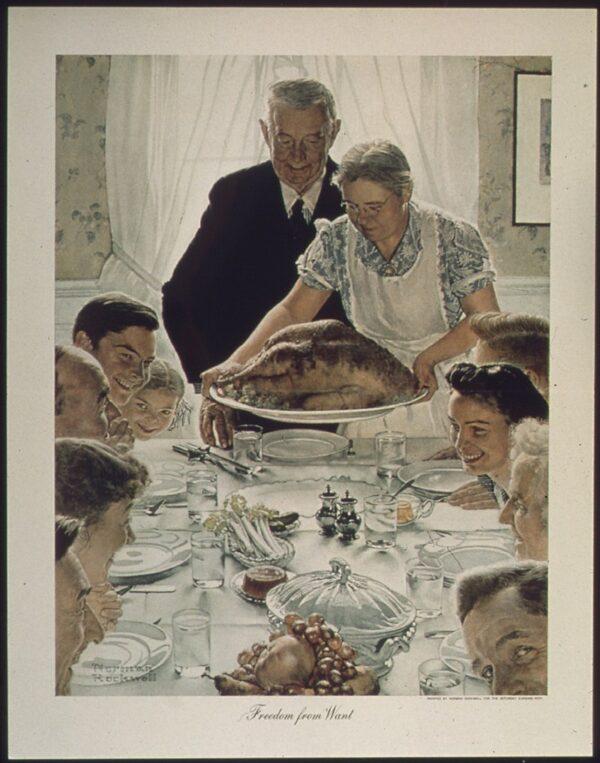

When Norman Rockwell’s famous painting ran in The Saturday Evening Post , it was accompanied by an essay written by Carlos Bulosan, a Filipino American migrant worker. His essay about labor, farm life, and hunger offers a stunning juxtaposition against Rockwell’s imagining of a white, middle-class family’s holiday feast.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

— Carlos Bulosan, Filipino American migrant worker, 1943

- The Standard American Diet

Galleries & Exhibits

A Decrease font size. A Reset font size. A Increase font size.

"The understanding of a culture comes from hearing the language, tasting the food, seeing personal interactions, experiencing the traditions, and so much more in context."

— Elizabeth Laval & Candice Pendergrass, Sikh Youth Public History Project

- Equity at the Heart of the Humanities

- Accessibility Statement

- Board of Directors

- Annual Report

- California Humanities: A State of Open Mind

- Historical Timeline

- Strategic Framework

- Job Opportunities

- California Documentary Project

- Civics + Humanities Middle Grades Grant Program

- Humanities for All

- Library Innovation Lab Overview

- Literature & Medicine®

- The Art of Storytelling

- California on the Ballot

- Tools of the Trade

- Youth Perspective and the Future of California

- United We Stand

- ARP: California Humanities Relief and Recovery Grants

- CA CARES: Humanities Relief and Recovery Grants Awards

- Community Stories

- In the Banlieues/Centering the Margin: Oakland/Saint-Denis

- On The Road

- Searching for Democracy

- War Comes Home

- We Are the Humanities

- California Documentary Project Grants

- Emerging Journalist Fellowship

- Humanities for All Project Grants

- Humanities for All Quick Grants

- Library Innovation Lab

- Grant Deadlines & Overview

- Events Near You

- How Can California Overcome Its Voter Disillusionment? (10.3.24)

- Our Funders

- Nancy Hatamiya Arts & Humanities Fund

- Library Innovation Lab Fund

"The understanding of a culture comes from hearing the language, tasting the food, seeing personal interactions, experiencing the traditions, and so much more when it is in context."

“An Unfinished Work:” A Filipino American Perspective on America

- Kerri Young

- September 30, 2024

Above: From the cover of America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan. Illustration courtesy of Penguin Classics.

October is Filipino American History Month, recognizing the history, culture, and contributions of Filipino Americans to the United States. 2024 is also a major election year, and with a little over a month before people head to the polls, we are spotlighting a Humanities for All Quick Grant -supported project that expertly uses musical composition and historical writing to blend the Filipino American experience in California with commentary on the ongoing project that is American democracy.

Composer Andres R. Luz’s Bulosan: On American Democracy features not only music, but also excerpts from novelist and poet Carlos Bulosan’s novel America is in the Heart and the essay “Freedom from Want.” These selected passages invite audiences to consider Bulosan’s advocacy of American democracy and human rights, relative to his experiences as part of a persecuted minority living on the US West Coast during the 1930s–1950s. To further build upon the project’s humanities elements, Luz featured the composition as part of two public programs with lectures and Q&A discussion to illuminate sociopolitical issues for students and general audiences in January 2024.

Below, Luz dives into the history behind this work, why it is important for contemporary audiences to learn and experience Bulosan’s story, and what we can learn moving into fall elections.

Carlos Bulosan’s writing focuses on the contradiction of America’s democratic vision. How did his experiences in California in the first part of the 20th century—his life among migrant farmers, tenant dwellers, colonial subjects, and struggling workers— inform his vision of freedom?

In Carlos Bulosan’s semiautobiographical novel America is in the Heart , the author recounts the teaching of the American-style public education system that he and countless Filipino schoolchildren of the poor and working-class received during the American Colonial Period lasting between 1898-1946. Touting nationalist concepts and values, generations of young Filipinos of that time became allured by idealized notions of democracy, liberty, capitalism, meritocracy, and socioeconomic equality that awaited them in faraway America, now presumably extended to them by virtue of being adopted by their host nation. These prospects stood in great contrast to the previous centuries of the Spanish imperial “hacienda” system which favored rich, powerful elites and marginalized landless citizens. The American dream of opportunity thereby fired the imagination of the Philippine working class to seek out the possibility of a prosperous life in a new land.

However, what these generations of Filipinos eventually came to experience first-hand was contradictory to the lessons they valued and were taught in the classrooms back home. Conditions of oppressive discrimination, systematized marginalization, and racial violence instigated by many native-born, white Americans against people of color newly arrived in the nation served as debilitating reminders that minorities were not wholly welcome to the US apart from their willingness to work in industries demanding manual labor under harsh environmental and working conditions for unsustainable wages. Despite that the Philippines was considered an American territory, Filipinos were classified as “nationals” or “wards” of the US—neither foreigners who could be deported, nor citizens permitted to work in professional, white-collar jobs despite any post-secondary education and training cultivated in their country of origin. These immigrant Filipino men eventually became known as the manongs (an Ilocano term of respect, translated into English as “elder brothers”) who arrived in the United States West Coast largely between the 1920s and 1940s to work as low-income, migrant, agricultural and/or factory laborers, and/or workers in the food service and hotel hospitality sectors chasing the fabled American Dream they learned about in their childhoods.

Carlos Bulosan’s writing recounts this dissonance between these ideal and real worlds, the paradox of the kindness and cruelty by Americans which he and his comrades encountered, and his own personal journey to reconcile the promises of America with its challenges. By reflecting deeply over a lifetime of experiences, as well as playing a key role as a labor activist working on behalf of his community, he eventually arrived at the conclusion that America was a work-in-progress, that American was yet “our unfinished dream” that remained worth fighting for, that America merited one’s patient sacrifice as it grew “into bright maturity through our labors.” 1 Bulosan therefore viewed the struggles that he and the Manongs endured as the “growing pains” that the country must experience before emerging into full maturity as the visionary “City on a Hill,” proclaimed by John Winthrop in 1630.

How did Bulosan’s writing inspire you to compose this piece (Bulosan: On American Democracy)? How does music provide a platform for a unique public humanities experience?

As America is in the Heart documents Bulosan’s reflective journey through literature in reconciling American ideals with his and his colleagues’ personal experiences, I wanted to similarly construct a musical journey for large ensemble that moved from darkness-to-light, or conflict-to-mediation-to-resolution, in kind. The music aims to sonically illustrate and enhance the moods and emotions behind the words, as well as to help amplify the drama in a concentrated duration of time for the listener.

As a Filipino-American who emigrated to the US, my wish was to pay homage to and raise awareness of Bulosan’s literary contributions and social activism. I find that despite the growing body of knowledge and scholarship dedicated to Bulosan’s legacy, his reputation largely remains unknown to many, and his story is worth communicating and appreciating. Additionally, given the political tenor of the times, I find that there is much relevance in Bulosan’s words for contemporary audiences in its defense of American democracy and the value placed upon natural rights and intellectual and artistic freedoms, and a thriving and well-educated populace.

Musical evocations of the January 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol and the August 2017 Unite the Right Rally at Charlottesville, are both challenges to American democracy that create contrasts that enhance listeners’ interest, providing contemporary context in counterpoint to Bulosan’s words. The combination of spoken word and music is therefore natural fit, in this case providing a means to raise awareness of unsung voices to an otherwise uninitiated audience, and in the case of Bulosan: On American Democracy , music and spoken narration is able to be skillfully connect ideas and meanings to allow listeners the opportunity to contemplate the presented issues to achieve greater insight and appreciation.

“America is based on the idea that it is a place for those seeking freedom, opportunity, and equality. If the United States aims to continue in this brave and bold experiment of democracy, it must not take democracy for granted.” Andres Luz

As we approach our fall elections, what can we learn from Bulosan about our own place and responsibility to the democratic process?

What we inherit from Bulosan’s example is the awareness that even in our country, which has a rich and storied history of doing great things, there are those that are left behind and have been underserved and oppressed as we have moved forward in our development. We must not forget nor overlook this truth. America is based on the idea that it is a place for those seeking freedom, opportunity, and equality. If the United States aims to continue in this brave and bold experiment of democracy, it must not take democracy for granted. It must aspire toward its ideals and pursue justice for all. It must know that democracy is tenuous, and that to properly realize its tenets, the nation must strive for the betterment of all its inhabitants. This is the American dream.

Ultimately, we as a people must recognize that we hold the power to steer the direction of this nation, a concept which has held true since the country’s founding. In his 1943 essay “Freedom from Want,” Bulosan asserts that “we are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.” Thus, America will be a nation that we as a people choose for it to be, so in November let us make the right decision. Long live representative democracy in the United States of America.

1 Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart, 312. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

This project was created with support from a Humanities for All Quick Grant .

About Andres Luz : Exemplified by Bulosan: On American Democracy , many of Dr. Luz’s compositions are informed by folkloric elements of his Filipino-American heritage, which have served as the source inspiration for a number of his works including the concertante piece for marimba solo and mixed ensemble.

In 2023, Luz’s dissertation composition, BULOSAN: ON AMERICAN DEMOCRACY for Narrator, Wind Symphony, and Fixed Media was the Winner of the American Prize in Composition in the University-Level Wind Ensemble Division, as well as the 2nd Place among Social Justice-Related Works among University-Level compositions submitted that year.

Related Articles

Engage in National Arts and Humanities Month 2024

California Celebrates National Arts and Humanities Month 2024

How Can California Overcome Its Voter Disillusionment? Join us October 3 to Discuss

A state affiliate of the National Endowment of the Humanities .

538 9th Street, Suite 210 Oakland, CA 94607 415.391.1474

1000 N Alameda Street, Suite 240 Los Angeles, CA 90012 415.391.1474

- Biographies and Features

- Morgenthau Holocaust Project

- Timeline: FDR Day by Day

- Research the Archives

- The Pare Lorentz Center

- Student Resources

- Summer Activities

- Social Media

- Museum Visit

- Research Visit

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Museum Store

- What is a Presidential Library

- Events & Registration

- Press and Media

- Program Archives

- Newsletter Archives

- Search FRANKLIN

- Plan a Research Visit

- Digital Collections

- Featured Topics

- Morgenthau Project

- Teaching Tools

- Civics for All of US

- Resources for Students

- Distance Learning

- Teacher Workshops

- Field Trips

- NAIN Teachers Conference

- Activities at Home

- 75th Anniversary

- History of the FDR Library

- Library Trustees

- Intern and Volunteer

- Donate TODAY!

- Ways To Give

- Get Involved

- Roosevelt Institute

- RI Annual Reports for Roosevelt Library

FDR and the Four Freedoms Speech

Web content display web content display.

Franklin Roosevelt was elected president for an unprecedented third term in 1940 because at the time the world faced unprecedented danger, instability, and uncertainty. Much of Europe had fallen to the advancing German Army and Great Britain was barely holding its own. A great number of Americans remained committed to isolationism and the belief that the United States should continue to stay out of the war, but President Roosevelt understood Britain's need for American support and attempted to convince the American people of the gravity of the situation.

In his Annual Message to Congress (State of the Union Address) on January 6, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt presented his reasons for American involvement, making the case for continued aid to Great Britain and greater production of war industries at home. In helping Britain, President Roosevelt stated, the United States was fighting for the universal freedoms that all people possessed.

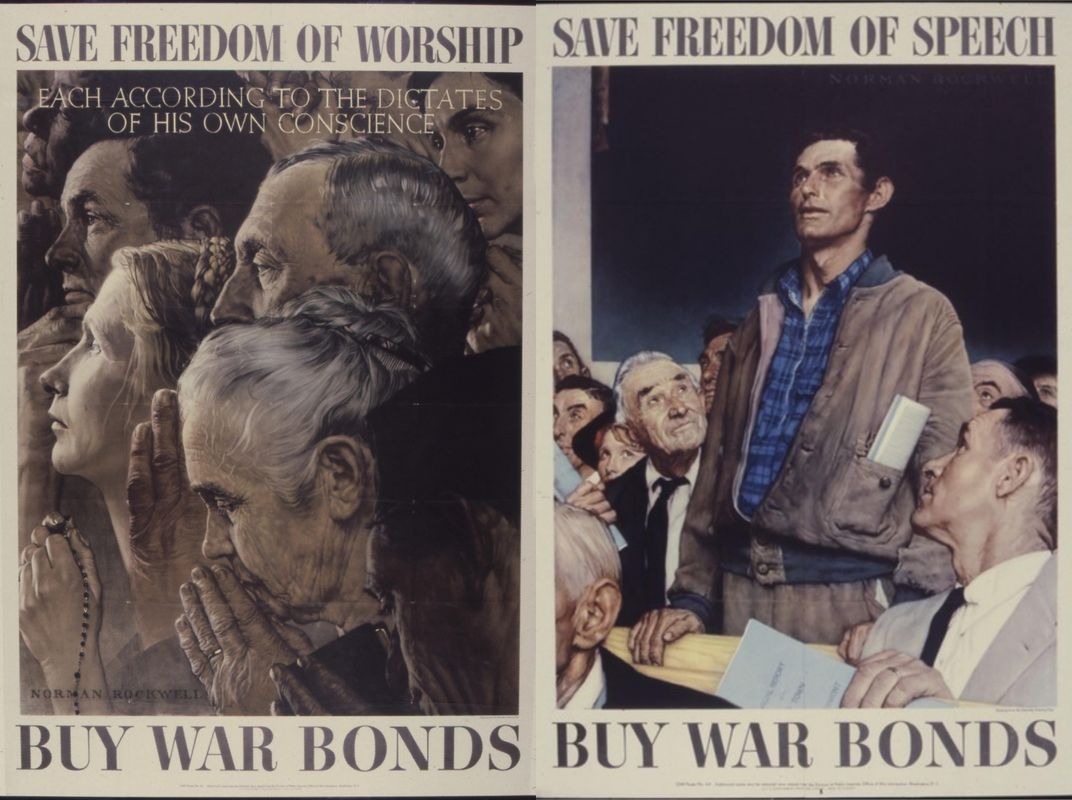

As America entered the war these "four freedoms" - the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear - symbolized America's war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom.

Roosevelt’s preparation of the Four Freedoms Speech was typical of the process that he went through on major policy addresses. To assist him, he charged his close advisers Harry L. Hopkins, Samuel I. Rosenman, and Robert Sherwood with preparing initial drafts. Adolf A. Berle, Jr., and Benjamin V. Cohen of the State Department also provided input. But as with all his speeches, FDR edited, rearranged, and added extensively until the speech was his creation. In the end, the speech went through seven drafts before final delivery.

The famous Four Freedoms paragraphs did not appear in the speech until the fourth draft. One night as Hopkins, Rosenman, and Sherwood met with the President in his White House study, FDR announced that he had an idea for a peroration (the closing section of a speech). As recounted by Rosenman: “We waited as he leaned far back in his swivel chair with his gaze on the ceiling. It was a long pause—so long that it began to become uncomfortable. Then he leaned forward again in his chair” and dictated the Four Freedoms. “He dictated the words so slowly that on the yellow pad I had in my lap I was able to take them down myself in longhand as he spoke.”

The ideas enunciated in the Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms were the foundational principles that evolved into the Atlantic Charter declared by Winston Churchill and FDR in August 1941; the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942; President Roosevelt’s vision for an international organization that became the United Nations after his death; and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 through the work of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Suggested Reading

Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights (Belknap Press, 2005).

Laura Crowell, “The Building of the ‘Four Freedoms’ Speech,” Speech Monographs 22, (November 1955): 266-283.

Samuel I. Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt (Harper & Brothers, 1952).

Halford R. Ryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Rhetorical Presidency (Greenwood Press, 1988).

Mission Statement

The Library's mission is to foster research and education on the life and times of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and their continuing impact on contemporary life. Our work is carried out by four major areas: Archives, Museum, Education and Public Programs.

- Research the Roosevelts

- News & Events

- Historic Collections

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

Carlos Bulosan’s Essay, ‘Freedom From Want’: A Freedom Born of Work

Author gives added meaning to rockwell’s painting.

Friends Read Free

When we all gather around the table with friends and family for Thanksgiving or Christmas, we feel joyful and thankful to be surrounded by such good people and blessings. During this time, we celebrate and share our blessings—the fruits of our labor, born of struggle and effort.

In 1943, Norman Rockwell captured this joy and thankfulness in his painting “Freedom From Want,” also known as “The Thanksgiving Picture” or “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” A family gathers around the table to partake in the wonderful fruits of their labor. This picture radiates with the warmth, joy, and gratitude that make such a meal so special.

All members of this family have a smile brightening their faces. A grandmotherly figure brings out the turkey while an older gentleman stands behind her at the head of the table. The elderly couple represents the living tradition of American ideals, which set the mold, security, and path for later generations. The others all lean in toward each other with excited faces, giving their full attention to those around them. A man in the bottom right corner looks directly at the viewer; he welcomes us into his world, free from want and full of gratitude and gladness.

Bulosan says that in order to obtain and enjoy the fruits of our labor, we must work to bring the good things of nature into our lives and to diminish the fear that surrounds us in our daily lives. When we work for the fruits and pleasures of our labor, we win security and peace for ourselves, our neighbors, and our country.

Tyrannical Thieves

When our history and freedoms are taken away or distorted, the end result is want. This means that we must work constantly, not for ourselves but for those who have enslaved us. We become slaves to fear, hunger, and want. We lack the ability and energy to enjoy the freedom that respects the dignity of the individual.

Bulosan says that, as part of the plan to enslave a free people, there are also those who seek to “falsify American history—the forces which drive many Americans to a corner of compromise with those who would distort the ideals of men that died for freedom.”

Marching On

In peace, we are free from want. In peace, abundance allows us to seek higher thoughts and virtues, and to obtain a better future for ourselves, our children, and our country.

In a land that created abundance for itself and much of the world, we work for that freedom from want, obtaining peace and security from fear and hunger. We have the chance to create a world that was the dream of our Founding Fathers, one in which we can truly pursue health of mind, body, and soul. We perpetuate a tradition that lives in each of us and supports the “living spirit of free men.”

When we sit down to our Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner, we can celebrate our freedom from want and enjoy the abundance that frees us from fear and hunger. On that occasion and during the whole year, we can faithfully preserve and pass down this freedom and the traditions of our ancestors to our children.

James Baldwin’s Short Story, ‘The Charcoal Man and the King’

L.M. Montgomery’s Short Story ‘The Letters’

Leo Tolstoy’s Short Story: ‘Three Questions’

O. Henry’s Short Story, ‘To Him Who Waits’

December 21, 2017

Norman Rockwell

The Four Freedoms Essays

Inspired by Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech, Norman Rockwell painted four images depicting those freedoms. These paintings went on to inspire all of America during World War II and beyond.

Post Editors

- Share on Facebook (opens new window)

- Share on Twitter (opens new window)

- Share on Pinterest (opens new window)

Weekly Newsletter

The best of The Saturday Evening Post in your inbox!

A mericans of 1943 knew the Second World War was being fought to preserve individual freedom, but many had trouble imagining just what that freedom looked like. In February and March of that year, Norman Rockwell — inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech — gave Americans a vision of the freedoms that justified all the sacrifice and suffering the war had brought them.

His paintings of President Roosevelt’s four postwar goals resonated so deeply with Americans in the 1940s that they became iconic symbols of American life, and they are still powerful images of what we prize in our country.

That same year, the Post commissioned four authors to write essays to accompany each Freedom painting.

Subscribe and get unlimited access to our online magazine archive.

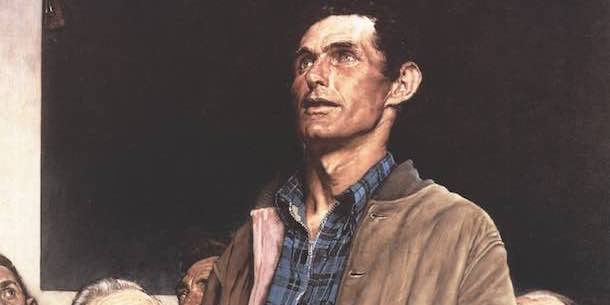

“Freedom of Speech” by Booth Tarkington

Longtime Post contributor and a two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Booth Tarkington depicted his ideas of free speech by way of a parable about the chance meeting of two young men at a small chalet in the Alps.

“Freedom of Worship” by Will Durant

A historian and philosopher, Will Durant spent 40 years writing the masterful, 11-volume series The Story of Civilization . In his essay, he identifies a little white church and its tall steeple as a symbol of the promise of freedom of worship.

“Freedom from Want” by Carlos Bulosan

A Filipino novelist and labor organizer in the U.S., Carlos Bulosan reminds us in his essay that freedom from want is not something that we can be given, but something we must earn — all of us together — through hard work, shared goals, and an honest sense of unity and equality.

“Freedom from Fear” by Stephen Vincent Benét

The essay by poet and novelist Stephen Vincent Benét appeared in the Post on the day of his death. In it, he reminds readers that the fight against fear is ultimately a fight against ignorance, and that it is not enough to fight our own ignorance, to hoard knowledge for our own peace of mind; to free ourselves from fear, all of mankind must grow its understanding together.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Recommended

Aug 08, 2024

Archives , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: At the Optometrist

Jeff Nilsson

Apr 25, 2024

Art , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: A Sporting Chance

Apr 15, 2024

Archives , Art , Cover Art , Norman Rockwell

Rockwell Files: In Search of the Lost Deduction

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Freedom, Want and Economic and Social Rights: Frame and Law

2009, Maryland Journal of International Law

In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized the aspiration for everyone to enjoy freedom from want and particular economic and social rights. Sixty years after the proclamation of the Universal Declaration, it is important to review its meaning and its effects in the context of significantly different legal, political, economic and cultural landscapes. To approach this task, this article employs the unusual device of considering a Norman Rockwell painting of Freedom from Want. This painting, well-known in the United States, responded to the local wartime political culture, and depicted the private enjoyment of material security in patriarchal, consumerist and culturally uniform terms. This article employs the themes made evident in the painting to underscore the assumptions made in the text of the Universal Declaration. Having outlined this reading, it suggests an alternative framework for understanding economic and social rights. Firstly, economic and social rights provide an important frame around redistributive contestations that strive for universalism in expression and the location of institutional responsibility in response. Secondly, economic and social rights ground legal norms, which are in some cases enforceable and in others available to exert a different kind of pressure on legal decision-makers. As frame and as law, economic and social rights provide an important pragmatic justification for the Universal Declaration's continuing relevance.

Related papers

Human Rights Quarterly, 1999

One of the dominant normative features of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)2 is the relatively integrated translation of the aspiration to protect human dignity into the enumeration of fundamental human rights. The bifurcation of what is now thought of ...

Colum Hum Rts L Rev, 1998

International Human Rights, Social Policy and Global Development: Critical Perspectives., 2020

This chapter discusses the historical development of ‘rights’ and how these transformed into ideas about ‘universal human rights’. It shows how the concept of rights developed historically from notions of legal through to political, social/economic and cultural rights and from individual to group rights. It describes how thinking about rights has developed from identifying rights solely with clans, tribes, communities, ethnic groups and then nation states, to linking them to all humanity - including minorities - through concepts of universal human rights. It recognises the contribution of philosophical ideas about humanity, equality, democracy and social justice, as well as the impact of human agency on the development of a range of rights, and argues that such developments do not take place in a vacuum (Donnelly, 2013: 75-92). Social, economic, ideological, cultural and geo-political influences engender our power to change society and ensure that human rights are a contested site. Rights are contested in their conceptualisation and in the development of oversight mechanisms. They are also contested in their implementation, enforceability and realisability on the ground (Freeman, 2017). In essence, it is argued that humans make human rights. As Karl Marx (1851-52) wrote in The Eighteenth Brumaire: ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past’ (Marx, 1851: 103).

This review paper investigates the philosophical cum political genesis of the concept of universal rights in the modern era through the examination of the conceptualization of the universal rights in de Vitoria, Grotius, Hobbes, Locke. The main goal is to explain to what extent their conceptions of universal rights are biased by their society of origin and particular interests at stake (in this case, those of the Euro-peans). That is the reason why, the supposed contribution of this paper is to understand how the current conceptualization of rights carries the legacy of these asymmetric features and, accordingly, to reshape the current conceptualization of (human) rights in order to make them truly universal and, thus, detachable from any particular philosophical traditions and local ethical views.

SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021

Journal of Human Rights, 2004

Ratio Juris, 1996

International Journal, 2005

Academia Biology, 2023

Archaeological Discovery, 2024

Journal of Pacific Archaeology, 2024

Alternautas, 2023

Higher Education Forum Vol.21 , 2024

Proceedings of 3rd Faculty of Management Sciences 2018 International Conference, 2018

Diálogo, 2020

Annals of Tourism Research, 2011

Antenor Quaderni 50.1, 2023

Cogent Psychology, 2019

Routledge , 2023

Jurnal Imiah Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran

Do Sul para o Mundo: pensando a tradução no contexto pós-pandemia, 2024

Solid State Ionics, 2004

La Voz de Panocho: Miguel Rubio Arróniz (1830 - c.1912). Tomo V, 2024

Tree Physiology, 2006

Biogeosciences, 2009

Ecological Entomology, 2018

Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology Volume 157, 2024

Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2019

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Views From The Edge

Raves, Rants, Reviews & Ramblings from an Asian American, Native Hawaiian & Pacific Islander Perspective

Monday, May 25, 2020

Bulosan's 'freedom from want' essay written in 1943 rings just as true today during the age of coronavirus.

"If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city," he writes. Today, you see the men outside of Home Depot waiting for work, or the men and women bent over in the fields harvesting crops.

"You usually see us working or waiting for work, and you think you know us, but our outward guise is more deceptive than our history," he continues.

When our crops are burned or plowed under, we are angry and confused. Sometimes we ask if this is the real America. Sometimes we watch our long shadows and doubt the future.

"When our crops are burned or plowed under, we are angry and confused. Sometimes we ask if this is the real America. Sometimes we watch our long shadows and doubt the future."

"But we are not really free unless we use what we produce. So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. It is only when we have plenty to eat — plenty of everything — that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.

"We do not take democracy for granted. We feel it grow in our working together — many millions of us working toward a common purpose. If it took us several decades of sacrifices to arrive at this faith, it is because it took us that long to know what part of America is ours.

"The totalitarian nations hate democracy. They hate us because we ask for a definite guaranty of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom from fear and want. Our challenge to tyranny is the depth of our faith in a democracy worth defending. Although they spread lies about us, the way of life we cherish is not dead. The American Dream is only hidden away, and it will push its way up and grow again."

"But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is.

"If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

"What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

"If you want to know what we are — we are marching!

No comments:

Post a comment.

AT THE SMITHSONIAN

Norman rockwell’s ‘four freedoms’ brought the ideals of america to life.

This wartime painting series reminded Americans what they were fighting for

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

Alice George

Museums Correspondent

![essay freedom from want A4000110C[1].jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/zucqM_kKi8RwPzX4nU4t1R7s9D4=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale():focal(731x475:732x476)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/63/f963c1ff-f960-4449-865f-6406aff22c4f/a4000110c1.jpg)

Norman Rockwell, the master of Americana, captured the essence of daily life in hundreds of 20th-century magazine covers, and 75 years ago this month, he accomplished a greater feat, translating the nation’s ideals into indelible images known as the Four Freedoms .

By illuminating rights that every American—and every person—should enjoy, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms validated the U.S. decision to enter World War II and overcome powerful enemies whose actions devalued human life. His enduring messages have lingered in the national consciousness, remaining as significant today as they were when the Saturday Evening Post published them in four consecutive weeks during the winter of 1943.

Rockwell’s images had a clear meaning, says the Smithsonian’s Larry Bird : “Why we fight, what we’re about, what we’re fighting for, what we’re fighting to save.” Bird is co-curator of the National Museum of American History’s exhibition “ American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith,” which features a large set of the original Four Freedoms war bond posters from 1943.

Immediately after publishing Rockwell’s four paintings— Freedom of Speech , Freedom of Religion , Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear —the magazine received 25,000 requests to purchase copies. Color reproductions of all four sold for 25 cents apiece. The paintings became the basis for 4 million war posters sold as part of the War Bonds effort, raising $132,992,539. “They were received by the public with more enthusiasm, perhaps, than any other paintings in the history of American art,” The New Yorker reported in 1945.

Within weeks of publication, Rockwell’s paintings began a national journey. Across 16 separate cities, a total of 1.2 million people lined up to see the paintings, which were put on display in department stores, not museums. Those who bought war bonds received color reproductions in return. After completing that tour, the paintings rode the rails to a wider assortment of towns and cities, where Americans could admire Rockwell’s works in a custom-made train car.

Although the paintings became famous as an endorsement of the struggle to defend American ideals in World War II, the Four Freedoms first entered the American lexicon in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s January 1941 State of the Union address, almost a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor swept the United States onto the field of battle. At the beginning of 1941, when isolationist sentiments still held sway over many Americans, Roosevelt’s goal was a simple one: to convince voters that standing alone ultimately could sacrifice freedoms at home and abroad.

“By an impressive expression of the public will and without regard to partisanship, we are committed to the proposition that principles of morality and considerations for our own security will never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors and sponsored by appeasers,” he told Americans. “We know that enduring peace cannot be bought at the cost of other people's freedom.”

FDR then described the four freedoms every human being should enjoy—an addition to the speech that the president himself made in its fourth draft. He wanted to make Americans understand why the United States should provide material support for the western Allies as they battled Germany’s Nazi regime and the Japanese empire, both of which were stripping away individual rights. At the time, Roosevelt was convinced the United States was not ready to enter the war, but he believed armaments production for the Allies represented one way to protect cherished freedoms without risking American lives. While his speech planted a seed of inspiration in Rockwell’s brain, staunch isolationists rejected FDR’s message, claiming that it promoted war.

The United States and Great Britain wrapped Roosevelt’s ideas into the Atlantic Charter issued in August 1941. Both the State of the Union and the Atlantic Charter represented these freedoms as international ideals—rights that should belong to anyone anywhere. And through international initiatives such as disarmament and economic stability agreements, any nation should be able to exist without fear and with the opportunity to offer broad rights to its citizens.

For Americans, the First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of religion. “Freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” are nowhere in the nation’s founding documents, but they reflect the hopes of a nation emerging from the Great Depression and preparing to enter the biggest global conflict ever. “They are aspirational goals that we, or at least those who believed in the sort of New Deal politics, saw as the role of government,” says Harry R. Rubenstein , who also curated the museum's exhibition American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith and, like Bird, is a contributor to a book bearing the same title.

Seventeen months after FDR’s address, Rockwell traveled to Washington to promote his idea of illustrating the Four Freedoms to bolster the war effort. His autobiography states that not one official initially welcomed his proposal. The hard truth was that there were people inside and outside of government who questioned the artistic value of Rockwell’s storytelling works, which were often equated with advertising illustrations. Ultimately, though—and the historical record is unclear on the details here—Rockwell was able to persuade the powers that were, reaching an agreement to produce the paintings for the government and the Saturday Evening Post magazine.

After promising to create the images, Rockwell faced the difficult task of transforming governmental phraseology into evocative tableaux on canvas. He had expected to finish all four scenes in two months, but the work dragged on through seven months of false starts and revisions.

Nonetheless, Rockwell was fully committed to the Four Freedoms . “I just cannot express to you how much this series means to me. Aside from their wonderful patriotic motive,” he told his impatient editors, “there are no subjects which could rival them in opportunity for human interest.”

With the February 20, 1943 issue of The Saturday Evening Post , the paintings began appearing weekly, each accompanied by an essay. Freedom of Speech features a blue-collar worker speaking to a room filled with more finely dressed Americans, all listening intently to the Lincolnesque figure’s words. Freedom of Religion depicts several individuals of different religious backgrounds in a moment of prayer. A man wearing a fez holds a Bible or Koran; a woman fingers a rosary. Rockwell worked for two months on this painting, which carries an inscription: “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.” The artist said later that he could not recall the source of the words; however, almost identical language can be found in the “Thirteen Articles of Faith” written by prophet Joseph Smith in 1842 to explain the bedrock beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons).

Freedom from Want pictures a large, healthy family eagerly awaiting a Thanksgiving feast. In Freedom from Fear, a mother and a father check on their sleeping children. In the father’s hand is a newspaper reporting the bombing of London—the only international reference in all four paintings. Rockwell finished these two paintings most quickly, and later said he thought they were the weakest. However, Bird says Freedom from Fear “continues to speak to me, just in daily life. And in that sense, it’s timeless.” Whether the headline refers to German attacks on London or to frightening developments in today’s world, the painting’s message applies.

While the Four Freedoms experienced huge success within the United States, they met a less receptive audience abroad. FDR described freedoms that should belong to everyone in all nations. Rockwell’s paintings, on the other hand, showed recognizably American scenes and seemed to celebrate life in the United States. Like most of his works, they portrayed Americans as a humble, God-fearing people who enjoy a strong and prosperous family life.

Freedom from Want features a dinner table laden with food—an image that rankled non-Americans suffering from the effects of wartime shortages. The sumptuous scene is colored by a playful Rockwell smiling up at the viewer from the lower right-hand corner. (This occasional representation of himself, much like film director Alfred Hitchcock’s cameo appearances in his suspenseful films, offers an unexpected dash of humor. A single eye on Freedom of Speech ’s right edge also belongs to Rockwell. He thought that inserting part or all of his face into scenes appropriately cast doubt on connections between art and truth.) Freedom from Fear , too, irritated some people in Allied war zones who were unable to protect their children from an immediate threat. Oceans away from World War II’s battlefronts, Rockwell’s protective parents enjoyed an extra layer of safety unavailable to parents in most nations at war.

Rockwell’s simple images transmit complex messages. What Bird calls “his toolkit” included Rockwell’s interpretation of “human nature, human condition, irony, juxtaposition of things”—all part of a technique now well-known to most Americans. Rubenstein believes “the genius of his work is taking a very lofty ideal and bringing it down to the most personal experience.” He also sees Rockwell’s choice of domestic scenes as one of the paintings’ strengths: “These aren’t the politicians; these aren’t heroic soldiers. These are the people who support the nation, or what the nation had been and hoped to be again.”

Roosevelt admired Rockwell’s skillful delivery of a potent message. “I think you have done a superb job in bringing home to the plain, everyday citizens the plain, everyday truths behind the Four Freedoms,” he told Rockwell. Says Bird, the artist “dramatized their meaning in a way that was not available to Roosevelt, as great as he was as a radio orator and as a communicator.” Capturing idealized visions of Americans, what Bird calls “our better angels,” empowers Rockwell’s art.

After the war, the already well-traveled paintings made another national expedition aboard the Freedom Train. More than 3.5 million Americans in 326 cities saw them on that 1947-48 trek. The offices of the Saturday Evening Post served as the paintings’ home throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s, with Rockwell finally reclaiming them before the magazine closed its doors in 1969.

Today, the paintings reside in the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, but this year, they begin another tour, entitled "Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & The Four Freedoms." It starts in May at the New York Historical Society, and visits Detroit, Washington, D.C., Houston and Caen in Normandy, France.

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

Alice George | | READ MORE

Alice George, Ph.D. is an independent historian with a special interest in America during the 1960s. A veteran newspaper editor, she is recently the author of The Last American Hero: The Remarkable Life of John Glenn and has authored or co-authored seven other books, focusing on 20th-century American history or Philadelphia history.

- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

Freedom From Want Summary & Study Guide

Freedom From Want Summary & Study Guide Description

The following version of this short story was used to create the guide: Silber, Joan. "Freedom from Want." The Best Short Stories 2021: The O. Henry Prize Winners. Vintage Anchor Publishing, 2021.

Joan Silber's short story "Freedom from Want," is written from the main character Rachel’s first person point of view. The narrative employs a largely linear structure and the past tense. The short story is set in New York City during the Trump era.

Rachel struggled to process her brother Saul's diagnosis with liver cancer. Then, not long after Saul's diagnosis, he told Rachel that Kirk, his boyfriend of 20 years, was leaving him. Rachel could not believe she had ever liked or trusted Kirk. She saw his abandonment as a betrayal of Saul and herself.

Rachel was 59 and lived in a small apartment in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of New York City. She lived with her ex Nick's daughter Nadia. Though the arrangement was unconventional, it worked. She and Nadia had a close connection. In the wake of Saul's diagnosis and breakup, she worried he would want to live with her.

Shortly before Saul got sick, Rachel started talking to her other ex, Bud, again. Bud had moved out of the city years prior and was now working for an NGO in Cambodia. Initially they corresponded only via email. Then Bud suggested that they talk to each other over Skype. During one conversation, Bud invited Rachel to come visit him in Phnom Penh. Rachel responded affirmatively because she did not think he was serious.

Though Saul and Kirk were not together anymore, they continued living together. Kirk owned their apartment. Saul had worked at the library for many years and therefore did not have a lot of money. Rachel thought it would be impossible for him to find a comfortable place to live.

One night Rachel discovered Nadia praying for Saul. She wondered about her brother's former Buddhist faith. When she asked him about it, she realized that Saul wanted nothing. His lack of desire worried rather than comforted her. If he did not have the desire to live, she might lose him sooner than expected.

Saul told Rachel that he would be moving into a studio apartment in his building. Kirk was helping with the deposit. Rachel, Kirk, Nadia, and Kirk's new boyfriend, Ethan, helped Saul move. The new apartment unnerved Rachel. It was small and bright, and seemed too isolating for Saul.

A few weeks later, Saul talked to Rachel about his will and told her that he would no longer be seeing his doctors. These things worried Rachel and made her upset. Not long later, Kirk told her that he had asked Saul to move back in with him, but that Saul had refused.

Meanwhile, Rachel continued talking to Bud. He had stopped inviting her to Cambodia. She assumed he was seeing someone else. Nevertheless, Rachel felt excited every time they talked. She soon realized that Bud had become her one and only desire.

Five weeks later, Saul moved back in with Kirk. Rachel and Nadia spent a pleasant evening with Saul, Kirk, and Ethan. In the elevator afterwards, Rachel realized that they had all shown Nadia a new and different version of love. Rachel was glad they had been able to give this to Nadia.

Read more from the Study Guide

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

Essays About Freedom: 5 Helpful Examples and 7 Prompts

Freedom seems simple at first; however, it is quite a nuanced topic at a closer glance. If you are writing essays about freedom, read our guide of essay examples and writing prompts.

In a world where we constantly hear about violence, oppression, and war, few things are more important than freedom. It is the ability to act, speak, or think what we want without being controlled or subjected. It can be considered the gateway to achieving our goals, as we can take the necessary steps.

However, freedom is not always “doing whatever we want.” True freedom means to do what is righteous and reasonable, even if there is the option to do otherwise. Moreover, freedom must come with responsibility; this is why laws are in place to keep society orderly but not too micro-managed, to an extent.

5 Examples of Essays About Freedom

1. essay on “freedom” by pragati ghosh, 2. acceptance is freedom by edmund perry, 3. reflecting on the meaning of freedom by marquita herald.

- 4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

5. What are freedom and liberty? by Yasmin Youssef

1. what is freedom, 2. freedom in the contemporary world, 3. is freedom “not free”, 4. moral and ethical issues concerning freedom, 5. freedom vs. security, 6. free speech and hate speech, 7. an experience of freedom.

“Freedom is non denial of our basic rights as humans. Some freedom is specific to the age group that we fall into. A child is free to be loved and cared by parents and other members of family and play around. So this nurturing may be the idea of freedom to a child. Living in a crime free society in safe surroundings may mean freedom to a bit grown up child.”

In her essay, Ghosh briefly describes what freedom means to her. It is the ability to live your life doing what you want. However, she writes that we must keep in mind the dignity and freedom of others. One cannot simply kill and steal from people in the name of freedom; it is not absolute. She also notes that different cultures and age groups have different notions of freedom. Freedom is a beautiful thing, but it must be exercised in moderation.

“They demonstrate that true freedom is about being accepted, through the scenarios that Ambrose Flack has written for them to endure. In The Strangers That Came to Town, the Duvitches become truly free at the finale of the story. In our own lives, we must ask: what can we do to help others become truly free?”

Perry’s essay discusses freedom in the context of Ambrose Flack’s short story The Strangers That Came to Town : acceptance is the key to being free. When the immigrant Duvitch family moved into a new town, they were not accepted by the community and were deprived of the freedom to live without shame and ridicule. However, when some townspeople reach out, the Duvitches feel empowered and relieved and are no longer afraid to go out and be themselves.

“Freedom is many things, but those issues that are often in the forefront of conversations these days include the freedom to choose, to be who you truly are, to express yourself and to live your life as you desire so long as you do not hurt or restrict the personal freedom of others. I’ve compiled a collection of powerful quotations on the meaning of freedom to share with you, and if there is a single unifying theme it is that we must remember at all times that, regardless of where you live, freedom is not carved in stone, nor does it come without a price.”

In her short essay, Herald contemplates on freedom and what it truly means. She embraces her freedom and uses it to live her life to the fullest and to teach those around her. She values freedom and closes her essay with a list of quotations on the meaning of freedom, all with something in common: freedom has a price. With our freedom, we must be responsible. You might also be interested in these essays about consumerism .

4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

“Freedom demands of one, or rather obligates one to concern ourselves with the affairs of the world around us. If you look at the world around a human being, countries where freedom is lacking, the overall population is less concerned with their fellow man, then in a freer society. The same can be said of individuals, the more freedom a human being has, and the more responsible one acts to other, on the whole.”

Carlson writes about freedom from a more religious perspective, saying that it is a right given to us by God. However, authentic freedom is doing what is right and what will help others rather than simply doing what one wants. If freedom were exercised with “doing what we want” in mind, the world would be disorderly. True freedom requires us to care for others and work together to better society.

“In my opinion, the concepts of freedom and liberty are what makes us moral human beings. They include individual capacities to think, reason, choose and value different situations. It also means taking individual responsibility for ourselves, our decisions and actions. It includes self-governance and self-determination in combination with critical thinking, respect, transparency and tolerance. We should let no stone unturned in the attempt to reach a state of full freedom and liberty, even if it seems unrealistic and utopic.”

Youssef’s essay describes the concepts of freedom and liberty and how they allow us to do what we want without harming others. She notes that respect for others does not always mean agreeing with them. We can disagree, but we should not use our freedom to infringe on that of the people around us. To her, freedom allows us to choose what is good, think critically, and innovate.

7 Prompts for Essays About Freedom

Freedom is quite a broad topic and can mean different things to different people. For your essay, define freedom and explain what it means to you. For example, freedom could mean having the right to vote, the right to work, or the right to choose your path in life. Then, discuss how you exercise your freedom based on these definitions and views.

The world as we know it is constantly changing, and so is the entire concept of freedom. Research the state of freedom in the world today and center your essay on the topic of modern freedom. For example, discuss freedom while still needing to work to pay bills and ask, “Can we truly be free when we cannot choose with the constraints of social norms?” You may compare your situation to the state of freedom in other countries and in the past if you wish.

A common saying goes like this: “Freedom is not free.” Reflect on this quote and write your essay about what it means to you: how do you understand it? In addition, explain whether you believe it to be true or not, depending on your interpretation.

Many contemporary issues exemplify both the pros and cons of freedom; for example, slavery shows the worst when freedom is taken away, while gun violence exposes the disadvantages of too much freedom. First, discuss one issue regarding freedom and briefly touch on its causes and effects. Then, be sure to explain how it relates to freedom.

Some believe that more laws curtail the right to freedom and liberty. In contrast, others believe that freedom and regulation can coexist, saying that freedom must come with the responsibility to ensure a safe and orderly society. Take a stand on this issue and argue for your position, supporting your response with adequate details and credible sources.

Many people, especially online, have used their freedom of speech to attack others based on race and gender, among other things. Many argue that hate speech is still free and should be protected, while others want it regulated. Is it infringing on freedom? You decide and be sure to support your answer adequately. Include a rebuttal of the opposing viewpoint for a more credible argumentative essay.

For your essay, you can also reflect on a time you felt free. It could be your first time going out alone, moving into a new house, or even going to another country. How did it make you feel? Reflect on your feelings, particularly your sense of freedom, and explain them in detail.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

IMAGES

COMMENTS

You can read the other three essays here. Freedom from Want. Originally published March 6, 1943. Subscribe and get unlimited access to our online magazine archive. Subscribe Today If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city. You usually see us working or waiting for work, and you think you know us ...

His essay about labor, farm life, and hunger offers a stunning juxtaposition against Rockwell's imagining of a white, middle-class family's holiday feast. We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. ... But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is ...

In his 1943 essay "Freedom from Want," Bulosan asserts that "we are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails." Thus, America will be a nation that we as a people choose for it to be, so in November let us make the right decision.

Carlos Bulosan's essay, "Freedom From Want," was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 as a companion piece to this famous Norman Rockwell painting. The work was one of four depicting ...

Freedom from Want is the third in a series of four oil paintings entitled Four Freedoms by Norman Rockwell.They were inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt's State of the Union Address, known as Four Freedoms, delivered to the 77th United States Congress on January 6, 1941. [2] In the early 1940s, Roosevelt's Four Freedoms themes were still vague and abstract to many, but the government used them ...

The Saturday Evening Post commissioned Carlos Bulosan to compose the essay "Freedom from Want" to accompany Norman Rockwell's corresponding painting "Freedom...

As America entered the war these "four freedoms" - the freedom of speech, the freedom of worship, the freedom from want, and the freedom from fear - symbolized America's war aims and gave hope in the following years to a war-wearied people because they knew they were fighting for freedom.

In his short essay, "Freedom From Want," Bulosan tells us that the joy and gratitude for the fruits of one's labor cannot exist without the freedom from want. When we want for things ...

"Freedom of Worship" by Will Durant. A historian and philosopher, Will Durant spent 40 years writing the masterful, 11-volume series The Story of Civilization. In his essay, he identifies a little white church and its tall steeple as a symbol of the promise of freedom of worship. "Freedom from Want" by Carlos Bulosan

ONE PORTRAIT OF FREEDOM FROM WANT, CIRCA 1943 Norman Rockwell's ―Freedom from Want‖ appeared as part of his series on the ―four freedoms,‖ which were proclaimed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and later adopted in the Preamble of the Universal Declaration.7 Drawing from his earlier response, in 1941, to the to the claim of ―a common ...

COMMENTARY Its a good bet that Norman Rockwell's Saturday Evening Post cover for "Freedom From Want" is more famous than Carlos Bulosan's essay that is meant to accompany the picture. As we near the end of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, the convergence of Memorial Day under the cloud of the coronavirus, it would behoove Americans to read the Filipino American author's thoughts ...

Freedom from want is beautifully depicted in Norman Rockwell's famous painting by the same name. It shows a family gathered around a dinner table, ready to eat. Toward the center of the painting is a turkey, the staple of a traditional Thanksgiving feast. But it's not the food that's striking; it's the faces.

Freedom from Want pictures a large, healthy family eagerly awaiting a Thanksgiving feast. In Freedom from Fear, a mother and a father check on their sleeping children. In the father's hand is a ...

A Commentary on Carlos Bulosan's Essay, "Freedom From Want" Reply reply Top 1% Rank by size . More posts you may like r/Philippines. r/Philippines. A subreddit for the Philippines and all things Filipino! Members Online. Lalaking suspek sa panggagahasa, natagpuang patay, putol ang ari | Frontline Pilipinas ...

The phrase, "the American dream" can mean many different things, but among the most basic interpretation is that America is a land of opportunity and freedom for all who come to it. The idea of the American dream has influenced people to come to America in search of economic opportunities, political choice, and religious freedom.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world. ... Each painting was published with a matching essay on that particular "Freedom": [32] Freedom of Speech, by Booth Tarkington (February 20 ...

The message in his "Freedom from Want" essay is as important to recall this Thanksgiving as is the radiant image in Rockwell's painting. Rockwell conveyed the joy of human gathering, ...

The following version of this short story was used to create the guide: Silber, Joan. "Freedom from Want." The Best Short Stories 2021: The O. Henry Prize Winners. Vintage Anchor Publishing, 2021. Joan Silber's short story "Freedom from Want," is written from the main character Rachel's first person point of view.

The Freedom from Want is Rockwell's implication to celebrate American freedom, delivering the emotional___ and clear message with the representation of harmonies Thanksgiving Day meal …show more content… The stylistic characteristic of this painting is realistic and exquisite in details.

5 Examples of Essays About Freedom 1. Essay on "Freedom" by Pragati Ghosh "Freedom is non denial of our basic rights as humans. Some freedom is specific to the age group that we fall into. A child is free to be loved and cared by parents and other members of family and play around. So this nurturing may be the idea of freedom to a child.