An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Domestic violence.

Martin R. Huecker ; Kevin C. King ; Gary A. Jordan ; William Smock .

Affiliations

Last Update: April 9, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Family and domestic violence is a common problem in the United States, affecting an estimated 10 million people every year; as many as one in four women and one in nine men are victims of domestic violence. Virtually all healthcare professionals will at some point evaluate or treat a patient who is a victim of domestic or family violence. Domestic and family violence includes economic, physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse of children, adults, or elders. Domestic violence causes worsened psychological and physical health, decreased quality of life, decreased productivity, and in some cases, mortality. Domestic and family violence can be difficult to identify. Many cases are not reported to health professionals or legal authorities. This activity describes the evaluation, reporting, and management strategies for victims of domestic abuse and stresses the role of team-based interprofessional care for these victims.

- Identify the epidemiology of domestic violence.

- Describe the types of domestic violence.

- Explain challenges associated with reporting domestic violence.

- Review some interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to identify domestic violence and improve outcomes for its victims.

- Introduction

Family and domestic violence including child abuse, intimate partner abuse, and elder abuse is a common problem in the United States. Family and domestic health violence are estimated to affect 10 million people in the United States every year. It is a national public health problem, and virtually all healthcare professionals will at some point evaluate or treat a patient who is a victim of some form of domestic or family violence. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

Unfortunately, each form of family violence begets interrelated forms of violence. The "cycle of abuse" is often continued from exposed children into their adult relationships and finally to the care of the elderly.

Domestic and family violence includes a range of abuse, including economic, physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological, toward children, adults, and elders.

Intimate partner violence includes stalking, sexual and physical violence, and psychological aggression by a current or former partner. In the United States, as many as one in four women and one in nine men are victims of domestic violence. Domestic violence is thought to be underreported. Domestic violence affects the victim, families, co-workers, and community. It causes diminished psychological and physical health, decreases the quality of life, and results in decreased productivity.

The national economic cost of domestic and family violence is estimated to be over 12 billion dollars per year. The number of individuals affected is expected to rise over the next 20 years, increasing the elderly population.

Domestic and family violence is difficult to identify, and many cases go unreported to health professionals or legal authorities. Due to the prevalence in our society, all healthcare professionals, including psychologists, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and physicians, will evaluate and possibly treat a victim or perpetrator of domestic or family violence. [6] [7]

Definitions

Family and domestic violence are abusive behaviors in which one individual gains power over another individual.

- Intimate partner violence typically includes sexual or physical violence, psychological aggression, and stalking. This may include former or current intimate partners.

- Child abuse involves the emotional, sexual, physical, or neglect of a child under 18 by a parent, custodian, or caregiver that results in potential harm, harm, or a threat of harm.

- Elder abuse is a failure to act or an intentional act by a caregiver that causes or creates a risk of harm to an elder.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Domestic violence, spousal abuse, battering, or intimate partner violence, is typically the victimization of an individual with whom the abuser has an intimate or romantic relationship. The CDC defines domestic violence as "physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive acts) by a current or former intimate partner."

Domestic and family violence has no boundaries. This violence occurs in intimate relationships regardless of culture, race, religion, or socioeconomic status. All healthcare professionals must understand that domestic violence, whether in the form of emotional, psychological, sexual, or physical violence, is common in our society and should develop the ability to recognize it and make the appropriate referral.

Violence Abuse Types

The types of violence include stalking, economic, emotional or psychological, sexual, neglect, Munchausen by proxy, and physical. Domestic and family violence occurs in all races, ages, and sexes. It knows no cultural, socioeconomic, education, religious, or geographic limitation. It may occur in individuals with different sexual orientations.

Reason Abusers Need to Control [8] [9] [10]

- Anger management issues

- Low self-esteem

- Feeling inferior

- Cultural beliefs they have the right to control their partner

- Personality disorder or psychological disorder

- Learned behavior from growing up in a family where domestic violence was accepted

- Alcohol and drugs, as an impaired individual may be less likely to control violent impulses

Risk Factors

Risk factors for domestic and family violence include individual, relationship, community, and societal issues. There is an inverse relationship between education and domestic violence. Lower education levels correlate with more likely domestic violence. Childhood abuse is commonly associated with becoming a perpetrator of domestic violence as an adult. Perpetrators of domestic violence commonly repeat acts of violence with new partners. Drug and alcohol abuse greatly increases the incidence of domestic violence.

Children who are victims or witness domestic and family violence may believe that violence is a reasonable way to resolve a conflict. Males who learn that females are not equally respected are more likely to abuse females in adulthood. Females who witness domestic violence as children are more likely to be victimized by their spouses. While females are often the victim of domestic violence, gender roles can be reversed.

Domination may include emotional, physical, or sexual abuse that may be caused by an interaction of situational and individual factors. This means the abuser learns violent behavior from their family, community, or culture. They see violence and are victims of violence.

- Epidemiology

Domestic violence is a serious and challenging public health problem. Approximately 1 in 3 women and 1 in 10 men 18 years of age or older experience domestic violence. Annually, domestic violence is responsible for over 1500 deaths in the United States. [11] [12] [13]

Domestic violence victims typically experience severe physical injuries requiring care at a hospital or clinic. The cost to individuals and society is significant. The national annual cost of medical and mental health care services related to acute domestic violence is estimated at over $8 billion. If the injury results in a long-term or chronic condition, the cost is considerably higher.

Financial hardship and unemployment are contributors to domestic violence. An economic downturn is associated with increased calls to the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

Fortunately, the national rate of nonfatal domestic violence is declining. This is thought to be due to a decline in the marriage rate, decreased domesticity, better access to domestic violence shelters, improvements in female economic status, and an increase in the average age of the population.

- Most perpetrators and victims do not seek help.

- Healthcare professionals are usually the first individuals with an opportunity to identify domestic violence.

- Nurses are usually the first healthcare providers victims encounter.

- Domestic violence may be perpetrated on women, men, parents, and children.

- Fifty percent of women seen in emergency departments report a history of abuse, and approximately 40% of those killed by their abuser sought help in the 2 years before death.

- Only one-third of police-identified victims of domestic violence are identified in the emergency department.

- Healthcare professionals who work in acute care need to maintain a high index of suspicion for domestic violence as supportive family members may, in fact, be abusers.

Child Abuse

Age, family income, and ethnicity are all risk factors for both sexual abuse and physical abuse. Gender is a risk factor for sexual abuse but not for physical abuse.

Each year there are over 3 million referrals to child protective authorities. Despite often being the first to examine the victims, only about 10% of the referrals were from medical personnel. The fatality rate is approximately two deaths per 100,000 children. Women account for a little over half of the perpetrators.

Intimate Partner Violence

According to the CDC, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men will experience physical violence by their intimate partner at some point during their lifetimes. About 1 in 3 women and nearly 1 in 6 men experience some form of sexual violence during their lifetimes. Intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking are high, with intimate partner violence occurring in over 10 million people each year.

One in 6 women and 1 in 19 men have experienced stalking during their lifetimes. The majority are stalked by someone they know. An intimate partner stalks about 6 in 10 female victims and 4 in 10 male victims.

At least 5 million acts of domestic violence occur annually to women aged 18 years and older, with over 3 million involving men. While most events are minor, for example grabbing, shoving, pushing, slapping, and hitting, serious and sometimes fatal injuries do occur. Approximately 1.5 million intimate partner female rapes and physical assaults are perpetrated annually, and approximately 800,000 male assaults occur. About 1 in 5 women have experienced completed or attempted rape at some point in their lives. About 1% to 2% of men have experienced completed or attempted rape.

The incidence of intimate partner violence has declined by over 60%, from about ten victimizations per 1000 persons age 12 or older to approximately 4 per 1000.

Due to underreporting and difficulty sampling, obtaining accurate incidence information on elder abuse and neglect is difficult. Elderly abuse is thought to occur in 3% to 10% of the population of elders.

Elderly patients may not report due to fear, guilt, ignorance, or shame. Clinicians underreport elder abuse due to poor recognition of the problem, lack of understanding of reporting methods and requirements, and concerns about physician-patient confidentiality.

- Pathophysiology

There may be some pathologic findings in both the victims and perpetrators of domestic violence. Certain medical conditions and lifestyles make family and domestic violence more likely. [13] [14] [15]

Perpetrators

While the research is not definitive, a number of characteristics are thought to be present in perpetrators of domestic violence. Abusers tend to:

- Have a higher consumption of alcohol and illicit drugs and assessment should include questions that explore drinking habits and violence

- Be possessive, jealous, suspicious, and paranoid.

- Be controlling of everyday family activity, including control of finances and social activities.

- Suffer low self-esteem

- Have emotional dependence, which tends to occur in both partners, but more so in the abuser

Domestic violence at home results in emotional damage, which exerts continued effects as the victim matures.

- Approximately 45 million children will be exposed to violence during childhood.

- Approximately 10% of children are exposed to domestic violence annually, and 25% are exposed to at least 1 event during their childhood.

- Ninety percent are direct eyewitnesses of violence.

- Males who batter their wives batter the children 30% to 60% of the time.

- Children who witness domestic violence are at increased risk of dating violence and have a more difficult time with partnerships and parenting.

- Children who witness domestic violence are at an increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder, aggressive behavior, anxiety, impaired development, difficulty interacting with peers, academic problems, and they have a higher incidence of substance abuse.

- Children exposed to domestic violence often become victims of violence.

- Children who witness and experience domestic violence are at a greater risk for adverse psychosocial outcomes.

- Eighty to 90% of domestic violence victims abuse or neglect their children.

- Abused teens may not report abuse. Individuals 12 to 19 years of age report only about one-third of crimes against them, compared with one-half in older age groups

Pregnant and Females

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends all women be assessed for signs and symptoms of domestic violence during regular and prenatal visits. Providers should offer support and referral information.

- Domestic violence affects approximately 325,000 pregnant women each year.

- The average reported prevalence during pregnancy is approximately 30% emotional abuse, 15% physical abuse, and 8% sexual abuse.

- Domestic violence is more common among pregnant women than preeclampsia and gestational diabetes.

- Reproductive abuse may occur and includes impregnating against a partner's wishes by stopping a partner from using birth control.

- Since most pregnant women receive prenatal care, this is an excellent time to assess for domestic violence.

The danger of domestic violence is particularly acute as both mother and fetus are at risk. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the psychological consequences of domestic abuse during pregnancy. There is more stress, depression, and addiction to alcohol in abused pregnant women. These conditions may harm the fetus.

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender

Domestic violence occurs in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender couples, and the rates are thought to be similar to a heterosexual woman, approximately 25%.

- There are more cases of domestic violence among males living with male partners than among males who live with female partners.

- Females living with female partners experience less domestic violence than females living with males.

- Transgender individuals have a higher risk of domestic violence. Transgender victims are approximately two times more likely to experience physical violence.

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender victims may be reticent to report domestic violence. Part of the challenge may be that support services such as shelters, support groups, and hotlines are not regularly available. This results in isolated and unsupported victims. Healthcare professionals should strive to be helpful when working with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender patients.

Usually, domestic violence is perpetrated by men against women; however, females may exhibit violent behavior against their male partners.

- Approximately 5% of males are killed by their intimate partners.

- Each year, approximately 500,000 women are physically assaulted or raped by an intimate partner compared to 100,000 men.

- Three out of 10 women at some point are stalked, physically assaulted, or raped by an intimate partner, compared to 1 out of every 10 men.

- Rape is primarily perpetrated by other men, while women engage in other forms of violence against men.

Although women are the most common victims of domestic violence, healthcare professionals should remember that men may also be victims and should be evaluated if there are indications present.

The elderly are often mistreated by their spouses, children, or relatives.

- Annually, approximately 2% of the elderly experience physical abuse, 1% sexual abuse, 5% neglect, 5% financial abuse, and 5% suffer emotional abuse.

- The annual incidence of elder abuse is estimated to be 2% to 10%, with only about 1 in 15 cases reported to the authorities.

- Approximately one-third of nursing homes disclosed at least 1 incident of physical abuse per year.

- Ten percent of nursing home staff self-report physical abuse against an elderly resident.

Elder domestic violence may be financial or physical. The elderly may be controlled financially. Elders are often hesitant to report this abuse if it is their only available caregiver. Victims are often dependent, infirm, isolated, or mentally impaired. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the high incidence of abuse in this population.

- History and Physical

The history and physical exam should be tailored to the age of the victim.

The most common injuries are fractures, contusions, bruises, and internal bleeding. Unexpected injuries to pre-walking infants should be investigated. The caregiver should explain unusual injuries to the ears, neck, or torso; otherwise, these injuries should be investigated.

Children who are abused may be unkempt and/or malnourished. They may display inappropriate behavior such as aggression, or maybe shy, withdrawn, and have poor communication skills. Others may be disruptive or hyperactive. School attendance is usually poor.

Intimate Partner Abuse

Approximately one-third of women and one-fifth of men will be victims of abuse. The most common sites of injuries are the head, neck, and face. Clothes may cover injuries to the body, breasts, genitals, rectum, and buttocks. One should be suspicious if the history is not consistent with the injury. Defensive injuries may be present on the forearms and hands. The patient may have psychological signs and symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and fatigue.

Medical complaints may be specific or vague such as headaches, palpitations, chest pain, painful intercourse, or chronic pain.

Intimate Partner Abuse: Pregnancy and Female

Abuse during pregnancy may cause as much as 10% of pregnant hospital admissions. There are a number of historical and physical findings that may help the provider identify individuals at risk.

If the examiner encounters signs or symptoms, she should make every effort to examine the patient in private, explaining confidentiality to the patient. Be sure to ask caring, empathetic questions and listen politely without interruption to answers.

Intimate Partner Abuse: Same-Sex

Same-sex partner abuse is common and may be difficult to identify. Over 35% of heterosexual women, 40% of lesbians, 60% of bisexual women experience domestic violence. For men, the incidence is slightly lower. In addition to common findings of abuse, perpetrators may try to control their partners by threatening to make their sexual preferences public.

The provider should be aware there are fewer resources available to help victims; further, the perpetrator and victim may have the same friends or support groups.

Intimate Partner Abuse: Men

Men represent as much as 15% of all cases of domestic partner violence. Male victims are also less likely to seek medical care, so that the incidence may be underreported. These victims may have a history of child abuse.

Elderly Abuse

Health professionals should ask geriatric patients about abuse, even if signs are absent.

- Pathologic characteristics of perpetrators including dementia, mental illness, and drug and alcohol abuse

- A shared living situation with the abuser

- Social isolation

Establishing that injuries are related to domestic abuse is a challenging task. Life and limb-threatening injuries are the priority. After stabilization and physical evaluation, laboratory tests, x-rays, CT, or MRI may be indicated. It is important that healthcare professionals first attend to the underlying issue that brought the victim to the emergency department. [1] [16] [17] [18]

- The evaluation should start with a detailed history and physical examination. Clinicians should screen all females for domestic violence and refer females who screen positive. This includes females who do not have signs or symptoms of abuse. All healthcare facilities should have a plan in place that provides for assessing, screening, and referring patients for intimate partner violence. Protocols should include referral, documentation, and follow-up.

- Health professionals and administrators should be aware of challenges such as barriers to screening for domestic violence: lack of training, time constraints, the sensitive nature of issues, and a lack of privacy to address the issues.

- Although professional and public awareness has increased, many patients and providers are still hesitant to discuss abuse.

- Patients with signs and symptoms of domestic violence should be evaluated. The obvious cues are physical: bruises, bites, cuts, broken bones, concussions, burns, knife or gunshot wounds.

- Typical domestic injury patterns include contusions to the head, face, neck, breast, chest, abdomen, and musculoskeletal injuries. Accidental injuries more commonly involve the extremities of the body. Abuse victims tend to have multiple injuries in various stages of healing, from acute to chronic.

- Domestic violence victims may have emotional and psychological issues such as anxiety and depression. Complaints may include backaches, stomachaches, headaches, fatigue, restlessness, decreased appetite, and insomnia. Women are more likely to experience asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, and diabetes.

Assuming the patient is stable and not in pain, a detailed assessment of victims should occur after disclosure of abuse. Assessing safety is the priority. A list of standard prepared questions can help alleviate the uncertainty in the patient's evaluation. If there are signs of immediate danger, refer to advocate support, shelter, a hotline for victims, or legal authorities.

- If there is no immediate danger, the assessment should focus on mental and physical health and establish the history of current or past abuse. These responses determine the appropriate intervention.

- During the initial assessment, a practitioner must be sensitive to the patient’s cultural beliefs. Incorporating a cultural sensitivity assessment with a history of being victims of domestic violence may allow more effective treatment.

- Patients that have suffered domestic violence may or may not want a referral. Many are fearful of their lives and financial well-being. They hence may be weighing the tradeoff in leaving the abuser leading to loss of support and perhaps the responsibility of caring for children alone. The healthcare provider needs to assure the patient that the decision is voluntary and that the provider will help regardless of the decision. The goal is to make resources accessible, safe, and enhance support.

- If the patient elects to leave their current situation, information for referral to a local domestic violence shelter to assist the victim should be given.

- If there is a risk to life or limb, or evidence of injury, the patient should be referred to local law enforcement officials.

- Counselors often include social workers, psychiatrists, and psychologists that specialize in the care of battered partners and children.

A detailed history and careful physical exam should be performed. If head trauma is suspected, consider an ophthalmology consultation to obtain indirect ophthalmoscopy.

Laboratory studies are often important for forensic evaluation and criminal prosecution. On occasion, certain diseases may mimic findings similar to child abuse. As a consequence, they must be ruled out.

- A urine test may be used as a screen for sexually transmitted disease, bladder or kidney trauma, and toxicology screening.

If bruises or contusions are present, there is no need to evaluate for a bleeding disorder if the injuries are consistent with an abuse history. Some tests can be falsely elevated, so a child abuse-specialist pediatrician or hematologist should review or follow-up these tests.

Gastrointestinal and Chest Trauma

- Consider liver and pancreas screening tests such as AST, ALT, and lipase. If the AST or ALT is greater than 80 IU/L, or lipase greater than 100 IU/L, consider an abdomen and pelvis CT with intravenous contrast.

- The highest-risk are those with abusive head trauma, fractures, nausea, vomiting, or an abnormal Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 15.

The evaluation of the pediatric skeleton can prove challenging for a non-specialist as there are subtle differences from adults, such as cranial sutures and incomplete bone growth. A fracture can be misinterpreted. If there is a concern for abuse, consider consulting a radiologist.

Imaging: Skeletal Survey

A skeletal survey is indicated in children younger than 2 years with suspected physical abuse. The incidence of occult fractures is as high as 1 in 4 in physically abused children younger than 2 years. The clinician should consider screening all siblings younger than 2 years.

The skeletal survey should include 2 views of each extremity; anteroposterior and lateral skull; and lateral chest, spine, abdomen, pelvis, hands, and feet. A radiologist should review the films for classic metaphyseal lesions and healing fractures, most often involving the posterior ribs. A “babygram” that includes only 1 film of the entire body is not an adequate skeletal survey.

Skeletal fractures will remodel at different rates, which are dependent on the age, location, and nutritional status of the patient.

Imaging: CT

If abuse or head trauma is suspected, a CT scan of the head should be performed on all children aged six months or younger or children younger than 24 months if intracranial trauma is suspected. Clinicians should have a low threshold to obtain a CT scan of the head when abuse is suspected, especially in an infant younger than 12 months.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast is indicated in unconscious children, have traumatic abdominal findings such as abrasions, bruises, tenderness, absent or decreased bowel sounds, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, or have elevation of the AST, an ALT greater than 80 IU/L, or lipase greater than 100 IU/L.

Special Documentation

Photographs should be taken before treatment of injuries.

Intimate Partner and Elder

Evaluate for evidence of dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, infection, substance abuse, improper medication administration, and malnutrition.

- X-rays of bruised of tender body parts to detect fractures

- Head CT scan to evaluate for intracranial bleeding as a result of abuse or the causes of altered mental status

- Pelvic examination with evidence collection if sexual assault

Evidence Collection

Domestic and family violence commonly results in the legal prosecution of the perpetrator. Preferably, a team specializing in domestic violence is called in to assist with evidence collection.

Each health facility should have a written procedure for how to package and label specimens and maintain a chain of custody. Law enforcement personnel will often assist with evidence collection and provide specific kits.

It is important to avoid destroying evidence. Evidence includes tissue specimens, blood, urine, saliva, and vaginal and rectal specimens. Saliva from bites can be collected; the bite mark is swabbed with a water-moistened cotton-tipped swab.

Clothing stained with blood, saliva, semen, and vomit should be retained for forensic analysis.

- Treatment / Management

The priority is the ABCs and appropriate treatment of the presenting complaints. However, once the patient is stabilized, emergency medical services personnel may identify problems associated with violence. [19] [20] [21]

Emergency Department and Office Care

Interventions to consider include:

- Make sure a safe environment is provided.

- Diagnose physical injuries and other medical or surgical problems.

- Treat acute physical or life-threatening injuries.

- Identify possible sources of domestic violence.

- Establish domestic violence as a diagnosis.

- Reassure the patient that he is not at fault.

- Evaluate the emotional status and treat.

- Document the history, physical, and interventions.

- Determine the risks to the victim and assess safety options.

- Counsel the patient that violence may escalate.

- Determine if legal intervention is needed and report abuse when appropriate or mandated.

- Develop a follow-up plan.

- Offer shelter options, legal services, counseling, and facilitate such referral.

Medical Record

The medical record is often evidence used to convict an abuser. A poorly document chart may result in an abuser going free and assaulting again.

Charting should include detailed documentation of evaluation, treatment, and referrals.

- Describe the abusive event and current complaints using the patient's own words.

- Include the behavior of the patient in the record.

- Include health problems related to the abuse.

- Include the alleged perpetrator's name, relationship, and address.

- The physical exam should include a description of the patient's injuries including location, color, size, amount, and degree of age bruises and contusions.

- Document injuries with anatomical diagrams and photographs.

- Include the name of the patient, medical record number, date, and time of the photograph, and witnesses on the back of each photograph.

- Torn and damaged clothing should also be photographed.

- Document injuries not shown clearly by photographs with line drawings.

- With sexual assault, follow protocols for physical examination and evidence collection.

Disposition

If the patient does not want to go to a shelter, provide telephone numbers for domestic violence or crisis hotlines and support services for potential later use. Provide the patient with instructions but be mindful that written materials may pose a danger once the patient returns home.

- A referral should be made to primary care or another appropriate resource.

- Advise the patient to have a safety plan and provide examples.

- Forty percent of domestic violence victims never contact the police.

- Of female victims of domestic homicide, 44% had visited a hospital emergency department within 2 years of their murder.

- Health professionals provide an opportunity for victims of domestic violence to obtain help.

- Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis varies with the injury type of injury and age.

Head Traum a

- Accidental injury

- Arteriovenous malformations

- Bacterial meningitis

- Birth trauma

- Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis

- Solid brain tumors

Bruises and Contusions

- Accidental bruises

- Bleeding disorder

- Congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots)

- Erythema multiforme

- Accidental burns

- Atopic dermatitis

- Contact dermatitis

- Inflammatory skin conditions

- Congenital syphilis

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Osteomyelitis

- Toddler’s fracture

Without proper social service and mental health intervention, all forms of abuse can be recurrent and escalating problems, and the prognosis for recovery is poor. Without treatment, domestic and family violence usually recurs and escalates in both frequency and severity. [3] [22] [23]

- Of those injured by domestic violence, over 75% continue to experience abuse.

- Over half of battered women who attempt suicide will try again; often they are successful with the second attempt.

In children, the potential for poor outcomes is particularly high as abuse inflicts lifelong effects. In addition to dealing with the sequelae of physical injury, the mental consequences may be catastrophic. Studies indicate a significant association between child sexual abuse and increased risk of psychiatric disorders in later life. The potential for the cycle of violence to continued from childhood is very high.

Children raised in families of sexual abuse may develop:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Conduct disorder

- Bipolar disorder

- Panic disorder

- Sleep disorders

- Suicide attempts

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Health Outcomes

There are multiple known and suspected negative health outcomes of family and domestic violence. There are long-term consequences to broken bones, traumatic brain injuries, and internal injuries.

Patients may also develop multiple comorbidities such as:

- Fibromyalgia

- High blood pressure

- Chronic pain

- Gastrointestinal disorders

- Gynecologic disorders

- Panic attacks

- Pearls and Other Issues

Screening: Tools

- The American Academy of Pediatricians has free guides for the history, physical, diagnostic testing, documentation, treatment, and legal issues in cases of suspected child abuse.

- The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides several scales assessing family relationships, including child abuse risks.

- The physical examination is still the most significant diagnostic tool to detect abuse. A child or adult with suspected abuse should be undressed, and a comprehensive physical exam should be performed. The skin should be examined for bruises, bites, burns, and injuries in different stages of healing. Examine for retinal hemorrhages, subdural hemorrhages, tympanic membrane rupture, soft tissue swelling, oral bruising, fractured teeth, and organ injury.

Screening: Recommendations

- Evaluate for organic conditions and medications that mimic abuse.

- Evaluate patients and caregivers separately

- Clinicians should regularly screen for family and domestic violence and elder abuse

- The Elder Abuse Suspicion Index can be used to assess for elder abuse

- Screen for cognitive impairment before screening for abuse in the elderly

- Pattern injury is more suspicious

- Failure to report child abuse is illegal in most states.

- Failure to report intimate partner and elder abuse is illegal in many states.

It is important to be aware of federal and state statutes governing domestic and family abuse. Remember that reporting domestic and family violence to law enforcement does not obviate detailed documentation in the medical record.

- Battering is a crime, and the patient should be made aware that help is available. If the patient wants legal help, the local police should be called.

- In some jurisdictions, domestic violence reporting is mandated. The legal obligation to report abuse should be explained to the patient.

- The patient should be informed how local authorities typically respond to such reports and provide follow-up procedures. Address the risk of reprisal, need for shelter, and possibly an emergency protective order (available in every state and the District of Columbia).

- If there is a possibility the patient’s safety will be jeopardized, the clinician should work with the patient and authorities to best protect the patient while meeting legal reporting obligations.

- The clinical role in managing an abused patient goes beyond obeying the laws that mandate reporting; there is a primary obligation to protect the life of the patient.

- The clinician must help mitigate the potential harm that results from reporting, provide appropriate ongoing care, and preserve the safety of the patient.

- If the patient desires, and it is acceptable to the police, a health professional should remain during the interview.

- The medical record should reflect the incident as described by the patient and any physical exam findings. Include the date and time the report was taken and the officer's name and badge number.

National Statutes

Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA)

Each state has specific child abuse statutes. Federal legislation provides guidelines for defining acts that constitute child abuse. The guidelines suggest that child abuse includes an act or failure recent act that presents an imminent risk of serious harm. This includes any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker that results in death, physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, or exploitation.

Elder Justice Act

The Elder Justice Act provides strategies to decrease the likelihood of elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The Act utilizes three significant approaches:

Patient Safety and Abuse Act

The Violence Against Woman Act makes it a federal crime to cross state lines to stalk, harass, or physically injure a partner; or enter or leave the country violating a protective order. It is a violation to possess a firearm or ammunition while subject to a protective order or if convicted of a qualifying crime of domestic violence.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Domestic violence may be difficult to uncover when the victim is frightened, especially when he or she presents to an emergency department or healthcare practitioner's office. The key is to establish an assessment protocol and maintain an awareness of the possibility that domestic and family violence may be the cause of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

Over 80% of victims of domestic and family violence seek care in a hospital; others may seek care in health professional offices, including dentists, therapists, and other medical offices. Routine screening should be conducted by all healthcare practitioners including nurses, physicians, physician assistants, dentists, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists. Interprofessional coordination of screening is a critical component of protecting victims and minimizing negative health outcomes. Health professional team interventions reduce the incidence of morbidity and mortality associated with domestic violence. Documentation is vital and a legal obligation.

- Healthcare professionals including the nurse should document all findings and recommendations in the medical record, including statements made denying abuse

- If domestic violence is admitted, documentation should include the history, physical examination findings, laboratory and radiographic finds, any interventions, and the referrals made.

- If there are significant findings that can be recorded, pictures should be included.

- The medical record may become a court document; be objective and accurate.

- Healthcare professionals should provide a follow-up appointment.

- Reassurance that additional assistance is available at any time is critical to protect the patient from harm and break the cycle of abuse.

- Involve the social worker early

- Do not discharge the patient until a safe haven has been established.

The following agencies provide national assistance for victims of domestic and family violence:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (800-CDC-INFO (232-4636)/TTY: 888-232-6348

- Childhelp: National Child Abuse Hotline: (800-4-A-CHILD (2-24453))

- The coalition of Labor Union Women (cluw.org): 202-466-4615

- Corporate Alliance to End Partner Violence: 309-664-0667

- Employers Against Domestic Violence: 508-894-6322

- Futures without Violence: 415-678-5500/TTY 800-595-4889

- Love Is Respect: National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline: 866-331-9474 /TTY: 866-331-8453

- National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence

- National Center on Elder Abuse

- National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (www.ncadv.org)

- National Network to End Domestic Violence: 202-543-5566

- National Organization for Victim Assistance

- National Resource Center on Domestic Violence: 800-537-2238

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center: 717-909-0710

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Click here for a simplified version.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Martin Huecker declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Kevin King declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Gary Jordan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: William Smock declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Huecker MR, King KC, Jordan GA, et al. Domestic Violence. [Updated 2023 Apr 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Kentucky Domestic Violence. [StatPearls. 2024] Kentucky Domestic Violence. Huecker MR, Malik A, King KC, Smock W. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Florida: Domestic Violence. [StatPearls. 2024] Florida: Domestic Violence. Houseman B, Kopitnik NL, Semien G. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization--national intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. [MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014] Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization--national intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, Merrick MT. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014 Sep 5; 63(8):1-18.

- Review Lethal domestic violence in eastern North Carolina. [N C Med J. 2000] Review Lethal domestic violence in eastern North Carolina. Gilliland MG, Spence PR, Spence RL. N C Med J. 2000 Sep-Oct; 61(5):287-90.

- Review Sequelae of abuse. Health effects of childhood sexual abuse, domestic battering, and rape. [J Nurse Midwifery. 1996] Review Sequelae of abuse. Health effects of childhood sexual abuse, domestic battering, and rape. Bohn DK, Holz KA. J Nurse Midwifery. 1996 Nov-Dec; 41(6):442-56.

Recent Activity

- Domestic Violence - StatPearls Domestic Violence - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics * Domestic Violence Video Presentations * Online CEU Courses

From the Editorial Board of the Peer-Reviewed Journal, Partner Abuse www.springerpub.com/pa and the Advisory Board of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Programs www.battererintervention.org * www.domesticviolenceintervention.net

Resources for researchers, policy-makers, intervention providers, victim advocates, law enforcement, judges, attorneys, family court mediators, educators, and anyone interested in family violence

PASK FINDINGS

61-Page Author Overview

Domestic Violence Facts and Statistics at-a-Glance

PASK Researchers

PASK Video Summary by John Hamel, LCSW

- Introduction

- Implications for Policy and Treatment

- Domestic Violence Politics

17 Full PASK Manuscripts and tables of Summarized Studies

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH

THE PARTNER ABUSE STATE OF KNOWLEDGE PROJECT

The world's largest domestic violence research data base, 2,657 pages, with summaries of 1700 peer-reviewed studies.

Courtesy of the scholarly journal, Partner Abuse www.springerpub.com/pa and the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Providers www.domesticviolenceintervention.net

MAJOR UPDATE COMING, JANUARY, 2025!

Over the years, research on partner abuse has become unnecessarily fragmented and politicized. The purpose of The Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project (PASK) is to bring together in a rigorously evidence-based, transparent and methodical manner existing knowledge about partner abuse with reliable, up-to-date research that can easily be accessed both by researchers and the general public.

Family violence scholars from the United States, Canada and the U.K. were invited to conduct an extensive and thorough review of the empirical literature, in 17 broad topic areas. They were asked to conduct a formal search for published, peer-reviewed studies through standard, widely used search programs, and then catalogue and summarize all known research studies relevant to each major topic and its sub-topics. In the interest of thoroughness and transparency, the researchers agreed to summarize all quantitative studies published in peer-reviewed journals after 1990, as well as any major studies published prior to that time, and to clearly specify exclusion criteria. Included studies are organized in extended tables, each table containing summaries of studies relevant to its particular sub-topic.

In this unprecedented undertaking, a total of 42 scholars and 70 research assistants at 20 universities and research institutions spent two years or more researching their topics and writing the results. Approximately 12,000 studies were considered and more than 1,700 were summarized and organized into tables. The 17 manuscripts, which provide a review of findings on each of the topics, for a total of 2,657 pages, appear in 5 consecutive special issues of the peer-reviewed journal Partner Abuse . All conclusions, including the extent to which the research evidence supports or undermines current theories, are based strictly on the data collected.

Contact: [email protected]

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE TRAININGS

Online CEU Courses - Click Here for More Information

Also see VIDEOS and ADDITIONAL RESEARCH sections below.

Other domestic violence trainings are available at: www.domesticviolenceintervention.net , courtesy of the Association of Domestic Violence Intervention Providers (ADVIP)

Click here for video presentations from the 6-hour ADVIP 2020 International Conference on evidence-based treatment.

NISVS: The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey

Click here for all reports

CLASSIC VIDEO PRESENTATIONS Murray Straus, Ph.D. * Erin Pizzey * Don Dutton, Ph.D. Click Here

Video: the uncomfortable facts on ipv, tonia nicholls, ph.d., video: batterer intervention groups: moving forward with evidence-based practice, john hamel, ph.d., additional research.

From Other Renowned Scholars and Clinicians. Click on any name below for research, trainings and expert witness/consultation services

PREVALENCE RATES

Arthur Cantos, Ph.D. University of Texas

Denise Hines, Ph.D. Clark University

Zeev Winstok, Ph.D. University of Haifa (Israel)

CONTEXT OF ABUSE

Don Dutton, Ph.D University of British Columbia (Canada)

K. Daniel O'Leary State University of New York at Stony Brook

Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Ph.D. University of South Alabama

ABUSE WORLDWIDE ETHNIC/LGBT GROUPS

Fred Buttell, Ph.D. Tulane University

Clare Cannon, Ph.D. University of California, Davis

Vallerie Coleman, Ph.D. Private Practice, Santa Monica, CA

Chiara Sabina, Ph.D. Penn State Harrisburg

Esteban Eugenio Santovena, Ph.D. Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez, Mexico

Christauria Welland, Ph.D. Private Practice, San Diego, CA

RISK FACTORS

Louise Dixon, Ph.D. University of Birmingham (U.K.)

Sandra Stith, Ph.D. Kansas State University

Gregory Stuart, Ph.D. University of Tennessee Knoxville

IMPACT ON VICTIMS AND FAMILIES

Deborah Capaldi, Ph.D. Oregon Social Learning Center

Patrick Davies, Ph.D. University of Rochester

Miriam Ehrensaft, Ph.D. Columbia University Medical Ctr.

Amy Slep, Ph.D. State University of New York at Stony Brook

VICTIM ISSUES

Carol Crabsen, MSW Valley Oasis, Lancaster, CA

Emily Douglas, Ph.D. Bridgewater State University

Leila Dutton, Ph.D. University of New Haven

Margaux Helm WEAVE, Sacramento, CA

Linda Mills, Ph.D. New York University

Brenda Russell, Ph.D. Penn State Berks

CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESPONSES

Ken Corvo, Ph.D. Syracuse University

Jeffrey Fagan, Ph.D. Columbia University

Brenda Russell, Ph.D, Penn State Berks

Stan Shernock, Ph.D. Norwich University

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Julia Babcock, Ph.D. University of Houston

Fred Buttell, Ph.D.Tulane University

Michelle Carney, Ph.D. University of Georgia

Christopher Eckhardt, Ph.D. Purdue Univerity

Kimberly Flemke, Ph.D. Drexel University

Nicola Graham-Kevan, Ph.D. Univ. Central Lancashire (U.K.)

Peter Lehmann, Ph.D. University of Texas at Arlingon

Penny Leisring, Ph.D. Quinnipiac University

Christopher Murphy, Ph.D. University of Maryland

Ronald Potter-Efron, Ph.D. Private Practice, Eleva, WI

Daniel Sonkin, Ph.D. Private Practice, Sausalito, CA.

Lynn Stewart, Ph.D. Correctional Service, Canada

Casey Taft, Ph.D Boston University School of Medicine

Jeff Temple, Ph.D. University of Texas Medical Branch

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Pathways From Family Violence to Adolescent Violence: Examining the Mediating Mechanisms

Spencer d li, ruoshan xiong, xiaohua zhang.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Tim Carter, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Reviewed by: Farnaz Kaighobadi, Bronx Community College, United States; Aino Suomi, Australian National University, Australia

*Correspondence: Min Liang, [email protected]

This article was submitted to Health Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2020 Sep 28; Accepted 2021 Jan 15; Collection date 2021.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Past research has documented a significant relationship between family violence and adolescent violence. However, much is unknown about the processes through which this association occurs, especially in the non-Western cultural context. To address this gap, we propose an integrated model encompassing multiple pathways that connect family violence to adolescent violence. Specifically, this study investigates how family violence is related to adolescent violence through violent peer association, normative beliefs about violence, and negative emotions.

We tested the model using the two-wave survey data collected from a probability sample of more than 1,100 adolescents residing in one of the largest metropolitan areas in China in 2015 to 2016.

Results and Conclusions

The results indicated that family violence predicted adolescent violence perpetration. Violent peer association, normative beliefs, and negative emotions, however, mediated much of the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence.

Keywords: family violence, youth violence, intergenerational transmission, China, mediation

Introduction

Family violence is a worldwide problem with a series of long-term adverse consequences for survivors, especially children, across their life span. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified children as the most common victims of family violence ( Timshel et al., 2017 ). According to child welfare data from Canada and the United States, corporal punishment and witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) are the major forms of family violence inflicted on children ( Canada, 2010 ; Smith et al., 2011 ; Renner and Whitney, 2012 ; Pecora et al., 2017 ). Prior research has shown that children who have been victims of child abuse or witnessed IPV are more likely to perpetrate violence later in their lives ( Widom and Wilson, 2015 ; Renner and Boel-Studt, 2017 ).

Despite the evidence that family violence promotes adolescent violence, much is unknown about how the process takes place. Several studies have shown that violence experienced at home is positively related to psychological and behavioral problems that increase adolescent risk for violence perpetration. In this regard, the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence may involve multiple pathways ( Liang et al., 2019 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Perry et al., 2020 ). For instance, children exposed to family violence may have a higher tendency to accept violent norms that legitimatize the use of violence as a means to resolve personal and interpersonal problems ( Xia et al., 2018 ). Additionally, adolescents raised in homes with higher levels of violence may develop more negative emotions and stronger association with violent peers, both of which are positively related to adolescent involvement in violent behavior ( Ohbuchi and Kondo, 2015 ; Edelstein, 2018 ). There are strong theoretical reasons to expect that all of these factors—normative beliefs about violence, negative emotions, and violent peer association—play critical roles in linking family violence to adolescent violence. Studies conducted thus far have either ignored these important mechanisms altogether or explored only some of these processes. Further, to our knowledge, there has been no study conducted in China examining all these mechanisms when trying to understand the process of intergenerational transmission of violence, which has been a longstanding problem in the country but has received virtually no attention in empirical research ( Chan, 2011 ; Widom and Wilson, 2015 ). By integrating these mechanisms into a theoretical model, the current study assesses the roles of normative beliefs about violence, negative emotions, and delinquent peer association in connecting family violence and adolescent violence using the two-wave survey data collected in China. In so doing, the study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the two forms of violence as they are manifested in Chinese society.

Literature Review

Family violence and adolescent violence.

Social learning theory maintains that delinquency including violent behavior is learned through interactions with intimate others, such as family members and peers ( Akers, 1998 ). As applied to violence, social learning theory predicts that adolescents exposed to a high level of family violence are prone to violent behavior because they learn to act violently from their family members, especially parents. Children learn to perpetrate violence mainly through two learning processes: observational learning through emulating the violent behavior of role models such as parents and intergenerational transmission of attitudes that are conducive to violence ( Sellers et al., 2005 ).

Prior research has provided strong support for social learning theory by demonstrating that experiencing physical abuse is positively associated with adolescents’ violent behavior ( Duman and Margolin, 2007 ; Xia et al., 2018 ; Karsberg et al., 2019 ). For example, by analyzing the data collected from a national sample, Cuartas et al. (2020) found that physical punishment strongly predicted adolescents’ delinquent involvement, especially violent offending. The same conclusion was drawn by Greene et al. (2020) and Fenimore et al. (2019) in their systematic reviews of parenting practices and adolescent behavior problems. They found that children were more likely to manifest violent and aggressive behaviors if they experienced physical abuse in childhood. Similar results also emerged from the studies of Henry et al. (2001) and Henneberger et al. (2013) , which showed that male and female adolescents were more likely to use violence in relationships if they had been subject to parental corporal punishment.

Apart from physical abuse, a growing body of empirical literature indicates that witnessing IPV is also associated with adolescent behavior problems, especially violence perpetration ( Whitefield et al., 2003 ; Narayan et al., 2015 ). For instance, using two-wave longitudinal data collected from a representative sample of Chinese adolescents, Xia et al. (2018) found that children with higher exposure to IPV were more accepting of the use of violence and more likely to perpetrate violent acts than their counterparts who observed fewer violent incidents at home. In light of these findings, we posit the following hypothesis:

H1: Family violence is positively associated with adolescent violence.

Family Violence, Normative Beliefs, and Adolescent Violence

The studies reviewed above point to the possibility that the psychological or behavioral characteristics of the adolescent act as mediators linking family violence to adolescent violence. One of the factors that has been cited in prior research is the adolescent’s normative beliefs about violence, which refer to a subjective appraisal of a specific violent act that is expected or desired under a given circumstance ( Fishbein and Ajzen, 1980 ). According to social learning theory, youth develop a propensity for delinquency through learning the “values, orientations, and attitudes” that are favorable to committing delinquent acts from people close to them, including their parents ( Akers and Jennings, 2009 , p. 106). Consistent with this line of reasoning, adolescents who have more exposure to family violence would be more likely to develop normative beliefs that justify the use of violence as acceptable means to control and dominate others, which would in turn precipitate violent behavior.

Some studies have shown that experiencing violence at home increased individuals’ acceptance of violent norms, which in turn predicted future violent behavior. These patterns of relationships have been found in different adolescent demographic groups ( Brendgen et al., 2002 ; Coohey et al., 2013 ) and across socioeconomic strata ( Beyers et al., 2001 ). Markowitz (2001) , for example, found that experiencing violence early in life increased favorable attitudes toward violence against others and violent attitudes positively predicted subsequent violence against both children and intimate partners. Viewing from the opposite direction, Mumford et al. (2016) found that youth grown up with positive parenting and high-quality parental relationship were less likely to become tolerant of violence and consequently were less prone to violent behavior in late adolescence and early adulthood. Based on these studies, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2: Normative beliefs about violence mediate the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence. Specifically, family violence will promote adolescents’ approve of the use of violence, thereby increasing their involvement in violent behavior.

Family Violence, Negative Emotions, and Adolescent Violence

Exposure to family violence is also an established risk factor for negative emotions in adolescence ( Baek et al., 2019 ; Caspi et al., 1994 ). Prior research has indicated that children who have experienced family violence are more likely to develop depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and a range of other emotional problems that are related to antisocial behavior ( Johnson et al., 2002 ; Herrenkohl et al., 2005 ; Sternberg et al., 2006 ). The general strain theory proposed by Agnew (1992 , 2013) provides a theoretical framework to understand the relationships among family violence, negative emotions, and adolescent violence. According to this theory, negative emotions operate as a leading cause of delinquent and violent behavior. External stressors such as family violence act as strains to increase adolescents’ negative emotions, which then lead to a higher likelihood of violence perpetration. Seen from this perspective, negative emotions should significantly mediate the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence.

Indeed, it has been well documented that negative emotions serve as a critical link between family violence and adolescent violence. A number of studies have shown that exposure to family violence increases negative emotions such as depression and anxiety in adolescence, and adolescents who harbor these negative emotions have higher levels of involvement in aggressive and violent behavior ( Baek et al., 2019 ; Mrug and Windle, 2010 ; Kassis et al., 2013 ; Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015 ). For example, McCloskey and Lichter (2003) found that children grown up in families with high prevalence of marital violence became more depressed as adolescents and elevated depression mediated the impact of interparental violence on adolescents’ aggression.

Informed by the previous literature, we propose the following hypothesis.

H3: Negative emotions mediate the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence.

Family Violence, Violent Peer Association, Violent Norms, Negative Emotions, and Adolescent Violence

Social learning theory ( Akers, 1998 ) postulates that family violence increases juvenile delinquency and violence by strengthening adolescents’ association with violent peers. For adolescents exposed to family violence, deviant and violent peers might emerge as a vicarious family. When an adolescent is associated more with individuals who are involved in criminal and deviant behaviors or demonstrate pro-criminal attitudes, he or she is more likely to engage in the criminal/deviant behavior ( Akers and Jennings, 2016 ; Hong et al., 2017 ).

Prior literature has shown that poor parenting, characterized by marital conflict and physical abuse, may foster children’s delinquent association ( Xia et al., 2018 ; Manzoni and Schwarzenegger, 2019 ; Liu et al., 2020 ). As most juvenile delinquency happens in groups, adolescents’ affiliation with violent peers operates as a strong predictor of adolescents’ delinquent and criminal behavior, including violent behavior ( Arriaga and Foshee, 2004 ; Dishion et al., 2010 ; Haggerty et al., 2013 ). Research has also shown that association with violent peers strengthens adolescents’ negative emotions such as depression and anxiety ( La Greca and Harrison, 2005 ; Bacchini et al., 2011 ). Additionally, affiliation with violence-prone friends is related to a more positive attitude toward violence ( Brendgen et al., 2002 ; Seddig, 2014 ). Based on this literature, we posit the following hypotheses.

H4: Violent peer association mediates the relationship between family violence and adolescent violence.

H5: Violent peer association increases negative emotions.

H6: Violent peer association promotes normative beliefs approving violence.

The Current Study

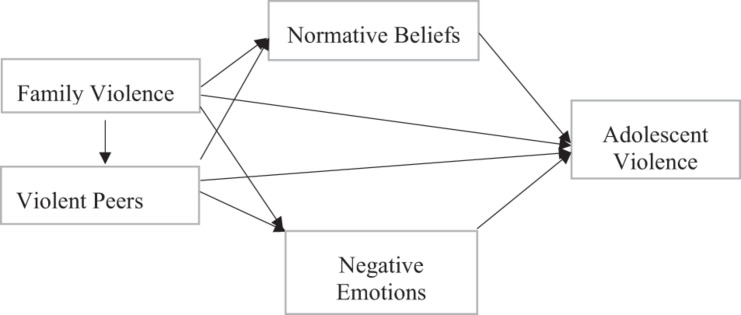

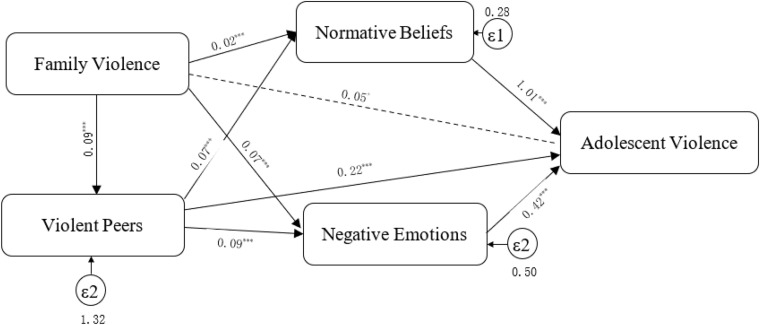

Although there are strong reasons to expect that normative beliefs about violence, negative emotions, and violent peer association all operate as important mechanisms linking family violence and adolescent violence, to our knowledge, no study has closely examined how all of these factors significantly contribute to the influence of family violence on adolescent violence using representative and longitudinal data. There are three reasons why it is important to examine all relevant pathways in an integrated model. First, it represents a fuller test of the social learning and general strain theories, which suggest that the influences of family violence on adolescent violence are effectuated through multiple mediating mechanisms involving normative beliefs, affective attributes, and peer relationships. Second, the omission of any important mediator in conceptualization and statistical analysis may run the risk of model misspecification, which can produce misleading research results. Third, from a policy perspective, the inability to understand all of the critical pathways to adolescent violence may undermine the effort to develop comprehensive strategies to prevent youth violence. Drawing on the social learning theory and general strain theory, this study integrates family violence, normative beliefs, negative emotions, violent peer association, and adolescent violence into a comprehensive model to assess the structural relationships among them using longitudinal data. The theoretical relationships among these concepts are illustrated in Figure 1 . As depicted in Figure 1 , family violence has a positive effect on adolescents’ violent peer association, normative beliefs approving violence, and negative emotions. Violent peer association is positively related to normative beliefs and negative emotions. Finally, all three mediators—violent peer association, normative beliefs approving violence, and negative emotions—are positively related to adolescent violence.

The theoretical model of the current study.

Data and Measurement

The data used in the current study were from a two-wave longitudinal research project on family processes and delinquency. The institutional review board of the university that funded the project reviewed and approved the study design and procedures. We collected the data in one of the largest metropolitan areas. The research site had been a major city in China before the country opened up its economy to the world in the late 1970s, but it has developed into a highly populated and diverse regional urban center in recent years with mixed urban and suburban districts. It is now home to 30 million people, including millions of migrant workers and ethnic minorities.

To ensure the representativeness of the sample, we randomly selected eligible participants for the study using a three-stage stratified probability proportionate to size sampling procedure. In the first stage, we randomly selected three districts, including two urban districts and 1 suburban district. In the second stage, we randomly selected 1 suburban middle school, one urban middle school, one suburban high school, and one urban high school from each sampled district, resulting in a total of 12 schools. In the third stage, in each sampled school, we proportionately selected a random number of classes in the 7th, 8th, 10th, and 11th grades. Secondary schools in China, including middle schools and high schools, are 3 years in duration. Considering that 9th and 12th graders (the final years of middle and high school) would graduate before the start of the second wave of the survey, we did not include them in the survey.

We contacted the sampled schools to seek their support and cooperation for the study. If the sampled school or class refused to participate in this survey, we randomly selected a replacement school or class until the sample size was reached. Once we obtained the cooperation of a school, we visited the school to introduce our study and sample the students. We provided the schools with the written informed consent forms for both the students and their parents. The forms contained information about the background and objectives of the study, the survey procedures, and a summary of the questions about on the questionnaire. In addition, the consent forms clearly stated that the participation in this study was entirely voluntary, and the privacy and confidentiality of the respondents would be strictly protected. We also asked the students to provide contact information if they agreed to be followed up in the second wave. Only students who agreed to participate in both waves of the study and whose parents signed a consent form were included in the current study, which yielded 1,300 eligible participants. A paper-and-pencil survey was administered to the sampled students. Around the same month in the following year (2016), we conducted the second wave of survey in the same schools with the same class of students. As with many other school-based surveys of adolescents, such as NLSY ( Benevides et al., 2020 ), we choose a 12-months interval between two waves since children may experience a significant change during their adolescence. It could be hard to capture these changes if the time gap was too long. The response rates for the Wave 1 and Wave 2 surveys were 97.20 and 96.73%, respectively. Additionally, 193 participants who had missing values on study variables, including the non-respondents, were excluded in the analyses, resulting in a final sample of 1,107.

Variables and Measurement

In this study, the key variables were family violence, violent peer association, normative beliefs about violence, negative emotions, and adolescent violence. To the extent possible, standard instruments with demonstrated reliability and validity were used to measure these concepts. Most of the measurements comprise multiple indicators, which help improve reliability and reduce measurement errors. With the exception of family violence, all of the other key variables were measured using data collected in the second wave in 2016. During early and middle adolescences, adolescents’ beliefs, mental health, and peer network can undergo substantial changes over a relatively short period of time ( Eccles et al., 1993 ; Chambers et al., 2003 ). For this reason, it is more appropriate to examine the contemporaneous effects using measures collected from the same year when assessing the interrelationships among normative beliefs, negative emotions, delinquent peer association, and violent behavior. Family violence, on the other hand, is more likely to have a lagged effect on adolescent violence through fostering a tendency for violent behavior by subjecting the adolescent to recurring exposure to violence at home. Therefore, it is more suitable to use wave-1 measures of family violence to predict wave-2 adolescent violence.

Adolescent Violence

Adolescent violence was measured by using a modified questionnaire from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN; Earls et al., 2006 ), which was administered in the survey in the second wave in 2016. The respondents reported the frequency of the following eight forms of violence they perpetrated during the last year: taking something from others with a threat, threatening someone with a knife or gun, hurting someone with a knife or gun, participating in a gang fight, hitting someone or threatening to hit someone, assaulting someone badly, robbing someone in a violent way, and having sex with someone against their will. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale, from 0 for “never” to 6 for “at least 1 time per day” ( Anderson, 1997 ). It is a common practice in criminological research to use the sum of different delinquent acts to measure the level and type of delinquent involvement ( Elliott and Huizinga, 1983 ; Li and Xia, 2018 ), especially when the original responses are assessed on an ordinal scale. We followed this approach by computing a total score as the measure of adolescent violence after dummy coding each of eight violent acts into 0 for “never” and 1 for all other answers.

Family Violence

Most studies conducted in this area have used measures of child-directed violence such as child physical abuse or child-witnessed violence such as interparental violence ( Maxwell and Maxwell, 2003 ). To tap both dimensions of family violence, we included IPV and child physical abuse in our measure of the overall level of violence that the adolescent experienced in the home environment. The two forms of family violence have shown to be highly correlated in Chinese society ( Chan, 2011 ). IPV was measured by the adolescents’ responses to four questions about how often their father (mother) hit their mother (father) and how often their father (mother) yelled at their mother (father). Physical abuse was also measured by four questions about how often the father (mother) beat the child for no reason and how often the father (mother) slapped/beat the child for doing something wrong. All of the questions had the following possible responses: “never,” “seldom,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “always.” A total score was computed by summing all of the items after they were converted to dichotomous measures with 0 representing “never” and 1 representing “seldom,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “always” ( Kwong et al., 2003 ).

Violent Peer Association

Violent peer association was measured by two questions asking the respondents how many of their friends engaged in fighting, and in threatening and intimidating others. The answers ranged from 0 for “none” to 4 for “all of them.” We used the sum of the scores on the two items to measure violent peer association. The Cronbach’s alpha for the two items was 0.65.

Normative Beliefs Approving Violence

Normative beliefs were assessed using the general belief questions about aggression and violence developed by Huesmann et al. (1992) , which consisted of five items. The questions included “in general, it is wrong to hit other people”; “in general, it is OK to yell at others and say bad things”; “In general, it is OK to take your anger out on others by using physical force”; “it is generally wrong to get into physical fights with others”; and “it is usually OK to push or shove other people around when you’re mad.” The answers ranged from 1 for “it’s really wrong” to 4 for “it’s perfectly OK.” We calculated the mean of the items after reverse coding some of the items so that the higher scores represented stronger approval of the use of aggression and violence. The Cronbach’s alpha for the eight items was 0.70.

Negative Emotions

The measure of negative emotions was selected from the Middle-School Student Mental Health Inventory (MMHI) developed by Wang et al. (1998) for Chinese students. The instrument consists of five subscales, including depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and interpersonal sensitivity and strain, and 30 questions in total (a full list of the questions is provided in Appendix 1 ). A factor analysis showed that the 30 items loaded onto the same factor representing negative emotionality. The answers for each question ranged from 1 for “never” to 5 for “always,” and the mean score was calculated, with a higher score indicating that respondents have more negative emotions. The Cronbach’s alpha for the 30 items was 0.96, and 0.82, 0.87, 0.84, 0.81, and 0.75 for the five subscales, respectively.

Age and Gender

Age and gender were included as the control variables in the current study. Age was measured by years ranging from 9 to 16 at wave 1 but its mean was nearly 14 years. Gender is a dichotomous variable with 0 for male and 1 for female. Each gender group accounted for about 50% of the sample.

Data Analysis

We conducted two types of analysis: descriptive analysis and mediation effect analysis. The descriptive analysis described the attributes of the variables included in the regression models, while the mediation effect analysis tested the structural relationships among the key concepts by using a series of multiple regression models ( Li, 2011 ). Depending on the distribution of dependent variables, we employed either negative binominal models or linear regression models to test the direct and indirect effects with Stata 14.2. Although the dataset contains a two-level structure with students nested within schools, we were unable to conduct a multilevel analysis because we did not collect data on the school level. School administrators were very reluctant to provide institutional data because of the concern that the information might be used to measure their job performance. A large number of them might have chosen not to participate in the survey had we insisted on collecting school-level data. As it stands now, the unit of analysis of our study remains at the individual level.

Descriptive Analysis