ORAL CASE PRESENTATION

Oct 15, 2017 | Clinical Teaching

- Oral case presentations are the fundamental way in which we communicate in medicine. To do this effectively, the content should be organized, clear, succinct, and with sufficient repetition to ensure understanding.

- Experts build OCPs by first considering the diagnoses they have in mind, then distilling the narrative in a way that implicitly highlights information relevant to the diagnoses under consideration.

- OCPs follow the same organization as a written H&P, and effective transition sentences ensure that listeners remain oriented to each relevant section.

- The OCP assessment is an opportunity to highlight important findings, using repetition to ensure understanding among listeners.

Additional Resources

- Oral Case Presentation (PDF)

Recent Posts

- Virtual Simulation in Medical Education

- CLIME Conversation Café Recording: The Jazz of Educational Design: Maximizing the Power of the Arts in Medical Education

- 2024 CALL FOR SMALL GRANT PROPOSALS

- CLIME Conversation Café Recording: The Power of Film in Medical Education

- CLIME Conversation Café Recording: Ethics in Medicine

How to make an oral case presentation to healthcare colleagues

The content and delivery of a patient case for education and evidence-based care discussions in clinical practice.

BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

A case presentation is a detailed narrative describing a specific problem experienced by one or more patients. Pharmacists usually focus on the medicines aspect , for example, where there is potential harm to a patient or proven benefit to the patient from medication, or where a medication error has occurred. Case presentations can be used as a pedagogical tool, as a method of appraising the presenter’s knowledge and as an opportunity for presenters to reflect on their clinical practice [1] .

The aim of an oral presentation is to disseminate information about a patient for the purpose of education, to update other members of the healthcare team on a patient’s progress, and to ensure the best, evidence-based care is being considered for their management.

Within a hospital, pharmacists are likely to present patients on a teaching or daily ward round or to a senior pharmacist or colleague for the purpose of asking advice on, for example, treatment options or complex drug-drug interactions, or for referral.

Content of a case presentation

As a general structure, an oral case presentation may be divided into three phases [2] :

- Reporting important patient information and clinical data;

- Analysing and synthesising identified issues (this is likely to include producing a list of these issues, generally termed a problem list);

- Managing the case by developing a therapeutic plan.

Specifically, the following information should be included [3] :

Patient and complaint details

Patient details: name, sex, age, ethnicity.

Presenting complaint: the reason the patient presented to the hospital (symptom/event).

History of presenting complaint: highlighting relevant events in chronological order, often presented as how many days ago they occurred. This should include prior admission to hospital for the same complaint.

Review of organ systems: listing positive or negative findings found from the doctor’s assessment that are relevant to the presenting complaint.

Past medical and surgical history

Social history: including occupation, exposures, smoking and alcohol history, and any recreational drug use.

Medication history, including any drug allergies: this should include any prescribed medicines, medicines purchased over-the-counter, any topical preparations used (including eye drops, nose drops, inhalers and nasal sprays) and any herbal or traditional remedies taken.

Sexual history: if this is relevant to the presenting complaint.

Details from a physical examination: this includes any relevant findings to the presenting complaint and should include relevant observations.

Laboratory investigation and imaging results: abnormal findings are presented.

Assessment: including differential diagnosis.

Plan: including any pharmaceutical care issues raised and how these should be resolved, ongoing management and discharge planning.

Any discrepancies between the current management of the patient’s conditions and evidence-based recommendations should be highlighted and reasons given for not adhering to evidence-based medicine ( see ‘Locating the evidence’ ).

Locating the evidence

The evidence base for the therapeutic options available should always be considered. There may be local guidance available within the hospital trust directing the management of the patient’s presenting condition. Pharmacists often contribute to the development of such guidelines, especially if medication is involved. If no local guidelines are available, the next step is to refer to national guidance. This is developed by a steering group of experts, for example, the British HIV Association or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . If the presenting condition is unusual or rare, for example, acute porphyria, and there are no local or national guidelines available, a literature search may help locate articles or case studies similar to the case.

Giving a case presentation

Currently, there are no available acknowledged guidelines or systematic descriptions of the structure, language and function of the oral case presentation [4] and therefore there is no standard on how the skills required to prepare or present a case are taught. Most individuals are introduced to this concept at undergraduate level and then build on their skills through practice-based learning.

A case presentation is a narrative of a patient’s care, so it is vital the presenter has familiarity with the patient, the case and its progression. The preparation for the presentation will depend on what information is to be included.

Generally, oral case presentations are brief and should be limited to 5–10 minutes. This may be extended if the case is being presented as part of an assessment compared with routine everyday working ( see ‘Case-based discussion’ ). The audience should be interested in what is being said so the presenter should maintain this engagement through eye contact, clear speech and enthusiasm for the case.

It is important to stick to the facts by presenting the case as a factual timeline and not describing how things should have happened instead. Importantly, the case should always be concluded and should include an outcome of the patient’s care [5] .

An example of an oral case presentation, given by a pharmacist to a doctor, is available here .

A successful oral case presentation allows the audience to garner the right amount of patient information in the most efficient way, enabling a clinically appropriate plan to be developed. The challenge lies with the fact that the content and delivery of this will vary depending on the service, and clinical and audience setting [3] . A practitioner with less experience may find understanding the balance between sufficient information and efficiency of communication difficult, but regular use of the oral case presentation tool will improve this skill.

Tailoring case presentations to your audience

Most case presentations are not tailored to a specific audience because the same type of information will usually need to be conveyed in each case.

However, case presentations can be adapted to meet the identified learning needs of the target audience, if required for training purposes. This method involves varying the content of the presentation or choosing specific cases to present that will help achieve a set of objectives [6] . For example, if a requirement to learn about the management of acute myocardial infarction has been identified by the target audience, then the presenter may identify a case from the cardiology ward to present to the group, as opposed to presenting a patient reviewed by that person during their normal working practice.

Alternatively, a presenter could focus on a particular condition within a case, which will dictate what information is included. For example, if a case on asthma is being presented, the focus may be on recent use of bronchodilator therapy, respiratory function tests (including peak expiratory flow rate), symptoms related to exacerbation of airways disease, anxiety levels, ability to talk in full sentences, triggers to worsening of symptoms, and recent exposure to allergens. These may not be considered relevant if presenting the case on an unrelated condition that the same patient has, for example, if this patient was admitted with a hip fracture and their asthma was well controlled.

Case-based discussion

The oral case presentation may also act as the basis of workplace-based assessment in the form of a case-based discussion. In the UK, this forms part of many healthcare professional bodies’ assessment of clinical practice, for example, medical professional colleges.

For pharmacists, a case-based discussion forms part of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Foundation and Advanced Practice assessments . Mastery of the oral case presentation skill could provide useful preparation for this assessment process.

A case-based discussion would include a pharmaceutical needs assessment, which involves identifying and prioritising pharmaceutical problems for a particular patient. Evidence-based guidelines relevant to the specific medical condition should be used to make treatment recommendations, and a plan to monitor the patient once therapy has started should be developed. Professionalism is an important aspect of case-based discussion — issues must be prioritised appropriately and ethical and legal frameworks must be referred to [7] . A case-based discussion would include broadly similar content to the oral case presentation, but would involve further questioning of the presenter by the assessor to determine the extent of the presenter’s knowledge of the specific case, condition and therapeutic strategies. The criteria used for assessment would depend on the level of practice of the presenter but, for pharmacists, this may include assessment against the RPS Foundation or Pharmacy Frameworks .

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Aamer Safdar for providing the script for the audio case presentation.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Onishi H. The role of case presentation for teaching and learning activities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70132–3

[2] Edwards JC, Brannan JR, Burgess L et al . Case presentation format and clinical reasoning: a strategy for teaching medical students. Medical Teacher 1987;9:285–292. doi: 10.3109/01421598709034790

[3] Goldberg C. A practical guide to clinical medicine: overview and general information about oral presentation. 2009. University of California, San Diego. Available from: https://meded.ecsd.edu/clinicalmed.oral.htm (accessed 5 December 2015)

[4] Chan MY. The oral case presentation: toward a performance-based rhetorical model for teaching and learning. Medical Education Online 2015;20. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28565

[5] McGee S. Medicine student programs: oral presentation guidelines. Learning & Scholarly Technologies, University of Washington. Available from: https://catalyst.uw.edu/workspace/medsp/30311/202905 (accessed 7 December 2015)

[6] Hays R. Teaching and Learning in Clinical Settings. 2006;425. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Tips for assessors for completing case-based discussions. 2015. Available from: http://www.rpharms.com/help/case_based_discussion.htm (accessed 30 December 2015)

You might also be interested in…

How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting

Be more proactive to convince medics, pharmacists urged

How pharmacists can encourage patient adherence to medicines

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1

The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the patient’s condition and further management can be planned accordingly. 2 To give a high quality presentation you need to take a thorough history. Consultants make decisions about patient care based on information presented to them by junior members of the team, so the importance of accurately presenting your patient cannot be overemphasised.

As a medical student, you are likely to be asked to present in numerous settings. A formal case presentation may take place at a teaching session or even at a conference or scientific meeting. These presentations are usually thorough and have an accompanying PowerPoint presentation or poster. More often, case presentations take place on the wards or over the phone and tend to be brief, using only memory or short, handwritten notes as an aid.

Everyone has their own presenting style, and the context of the presentation will determine how much detail you need to put in. You should anticipate what information your senior colleagues will need to know about the patient’s history and the care he or she has received since admission, to enable them to make further management decisions. In this article, I use a fictitious case to show how you can structure case presentations, which can be adapted to different clinical and teaching settings (box 1).

Box 1: Structure for presenting patient cases

Presenting problem, history of presenting problem, medical and surgical history.

Drugs, including allergies to drugs

Family history

Social history, review of systems.

Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

Differential diagnosis/impression

Investigations

Case: tom murphy.

You should start with a sentence that includes the patient’s name, sex (Mr/Ms), age, and presenting symptoms. In your presentation, you may want to include the patient’s main diagnosis if known—for example, “admitted with shortness of breath on a background of COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].” You should include any additional information that might give the presentation of symptoms further context, such as the patient’s profession, ethnic origin, recent travel, or chronic conditions.

“ Mr Tom Murphy is a 56 year old ex-smoker admitted with sudden onset central crushing chest pain that radiated down his left arm.”

In this section you should expand on the presenting problem. Use the SOCRATES mnemonic to help describe the pain (see box 2). If the patient has multiple problems, describe each in turn, covering one system at a time.

Box 2: SOCRATES—mnemonic for pain

Associations

Time course

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“ The pain started suddenly at 1 pm, when Mr Murphy was at his desk. The pain was dull in nature, and radiated down his left arm. He experienced shortness of breath and felt sweaty and clammy. His colleague phoned an ambulance. He rated the pain 9/10 in severity. In the ambulance he was given GTN [glyceryl trinitrate] spray under the tongue, which relieved the pain to 5/10. The pain lasted 30 minutes in total. No exacerbating factors were noted. Of note: Mr Murphy is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack year history”

Some patients have multiple comorbidities, and the most life threatening conditions should be mentioned first. They can also be categorised by organ system—for example, “has a long history of cardiovascular disease, having had a stroke, two TIAs [transient ischaemic attacks], and previous ACS [acute coronary syndrome].” For some conditions it can be worth stating whether a general practitioner or a specialist manages it, as this gives an indication of its severity.

In a surgical case, colleagues will be interested in exercise tolerance and any comorbidity that could affect the patient’s fitness for surgery and anaesthesia. If the patient has had any previous surgical procedures, mention whether there were any complications or reactions to anaesthesia.

“Mr Murphy has a history of type 2 diabetes, well controlled on metformin. He also has hypertension, managed with ramipril, and gout. Of note: he has no history of ischaemic heart disease (relevant negative) (see box 3).”

Box 3: Relevant negatives

Mention any relevant negatives that will help narrow down the differential diagnosis or could be important in the management of the patient, 3 such as any risk factors you know for the condition and any associations that you are aware of. For example, if the differential diagnosis includes a condition that you know can be hereditary, a relevant negative could be the lack of a family history. If the differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular disease, mention the cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Highlight any recent changes to the patient’s drugs because these could be a factor in the presenting problem. Mention any allergies to drugs or the patient’s non-compliance to a previously prescribed drug regimen.

To link the medical history and the drugs you might comment on them together, either here or in the medical history. “Mrs Walsh’s drugs include regular azathioprine for her rheumatoid arthritis.”Or, “His regular drugs are ramipril 5 mg once a day, metformin 1g three times a day, and allopurinol 200 mg once a day. He has no known drug allergies.”

If the family history is unrelated to the presenting problem, it is sufficient to say “no relevant family history noted.” For hereditary conditions more detail is needed.

“ Mr Murphy’s father experienced a fatal myocardial infarction aged 50.”

Social history should include the patient’s occupation; their smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug status; who they live with; their relationship status; and their sexual history, baseline mobility, and travel history. In an older patient, more detail is usually required, including whether or not they have carers, how often the carers help, and if they need to use walking aids.

“He works as an accountant and is an ex-smoker since five years ago with a 20 pack year history. He drinks about 14 units of alcohol a week. He denies any illicit drug use. He lives with his wife in a two storey house and is independent in all activities of daily living.”

Do not dwell on this section. If something comes up that is relevant to the presenting problem, it should be mentioned in the history of the presenting problem rather than here.

“Systems review showed long standing occasional lower back pain, responsive to paracetamol.”

Findings on examination

Initially, it can be useful to practise presenting the full examination to make sure you don’t leave anything out, but it is rare that you would need to present all the normal findings. Instead, focus on the most important main findings and any abnormalities.

“On examination the patient was comfortable at rest, heart sounds one and two were heard with no additional murmurs, heaves, or thrills. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. No peripheral oedema was noted and calves were soft and non-tender. Chest was clear on auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender and normal bowel sounds were heard. GCS [Glasgow coma scale] was 15, pupils were equal and reactive to light [PEARL], cranial nerves 1-12 were intact, and he was moving all four limbs. Observations showed an early warning score of 1 for a tachycardia of 105 beats/ min. Blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, saturations were 98% on room air, and he was apyrexial with a temperature of 36.8 ºC.”

Differential diagnoses

Mentioning one or two of the most likely diagnoses is sufficient. A useful phrase you can use is, “I would like to rule out,” especially when you suspect a more serious cause is in the differential diagnosis. “History and examination were in keeping with diverticular disease; however, I would like to rule out colorectal cancer in this patient.”

Remember common things are common, so try not to mention rare conditions first. Sometimes it is acceptable to report investigations you would do first, and then base your differential diagnosis on what the history and investigation findings tell you.

“My impression is acute coronary syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes other cardiovascular causes such as acute pericarditis, myocarditis, aortic stenosis, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Possible respiratory causes include pneumonia or pneumothorax. Gastrointestinal causes include oesophageal spasm, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. I would also consider a musculoskeletal cause for the pain.”

This section can include a summary of the investigations already performed and further investigations that you would like to request. “On the basis of these differentials, I would like to carry out the following investigations: 12 lead electrocardiography and blood tests, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, clotting screen, troponin levels, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin levels. I would also book a chest radiograph and check the patient’s point of care blood glucose level.”

You should consider recommending investigations in a structured way, prioritising them by how long they take to perform and how easy it is to get them done and how long it takes for the results to come back. Put the quickest and easiest first: so bedside tests, electrocardiography, followed by blood tests, plain radiology, then special tests. You should always be able to explain why you would like to request a test. Mention the patient’s baseline test values if they are available, especially if the patient has a chronic condition—for example, give the patient’s creatinine levels if he or she has chronic kidney disease This shows the change over time and indicates the severity of the patient’s current condition.

“To further investigate these differentials, 12 lead electrocardiography was carried out, which showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads. Results of laboratory tests showed an initial troponin level of 85 µg/L, which increased to 1250 µg/L when repeated at six hours. Blood test results showed raised total cholesterol at 7.6 mmol /L and nil else. A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields. Blood glucose level was 6.3 mmol/L; a glycated haemoglobin test result is pending.”

Dependent on the case, you may need to describe the management plan so far or what further management you would recommend.“My management plan for this patient includes ACS [acute coronary syndrome] protocol, echocardiography, cardiology review, and treatment with high dose statins. If you are unsure what the management should be, you should say that you would discuss further with senior colleagues and the patient. At this point, check to see if there is a treatment escalation plan or a “do not attempt to resuscitate” order in place.

“Mr Murphy was given ACS protocol in the emergency department. An echocardiogram has been requested and he has been discussed with cardiology, who are going to come and see him. He has also been started on atorvastatin 80 mg nightly. Mr Murphy and his family are happy with this plan.”

The summary can be a concise recap of what you have presented beforehand or it can sometimes form a standalone presentation. Pick out salient points, such as positive findings—but also draw conclusions from what you highlight. Finish with a brief synopsis of the current situation (“currently pain free”) and next step (“awaiting cardiology review”). Do not trail off at the end, and state the diagnosis if you are confident you know what it is. If you are not sure what the diagnosis is then communicate this uncertainty and do not pretend to be more confident than you are. When possible, you should include the patient’s thoughts about the diagnosis, how they are feeling generally, and if they are happy with the management plan.

“In summary, Mr Murphy is a 56 year old man admitted with central crushing chest pain, radiating down his left arm, of 30 minutes’ duration. His cardiac risk factors include 20 pack year smoking history, positive family history, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Examination was normal other than tachycardia. However, 12 lead electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads and troponin rise from 85 to 250 µg/L. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated and a diagnosis of NSTEMI [non-ST elevation myocardial infarction] was made. Mr Murphy is currently pain free and awaiting cardiology review.”

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i4406

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 - 3 . doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0900-x pmid:19139965 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Olaitan A, Okunade O, Corne J. How to present clinical cases. Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539.

- ↵ Gaillard F. The secret art of relevant negatives, Radiopedia 2016; http://radiopaedia.org/blog/the-secret-art-of-relevant-negatives .

- © 2019

Presenting Your Case

A Concise Guide for Medical Students

- Clifford D. Packer 0

Professor of Medicinem, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, Cleveland, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Provides a comprehensive guide to case presentation and related activities

- Covers various types of oral case presentations on the wards, including the traditional new patient presentation, transfers, night float admissions, and brief SOAP presentations on daily rounds

- Prepares medical students for their clerkship evaluations, which depend largely on the quality of their oral presentations

11k Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Authors and affiliations, about the author, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

Buying options

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check for access.

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, the importance of a good case presentation and why students struggle with it.

Clifford D. Packer

Organization of the Oral Case Presentation

Variations on the oral case presentation, the hpi: a timeline, not a time machine, pertinent positives and negatives, the diagnostic power of description, the assessment and plan, approaches to differential diagnosis, searching and citing the literature, adding value to the oral presentation, teaching rounds: speaking up, getting involved, and learning to accept uncertainty, the art of the 5-minute talk, future directions of the oral case presentation, back matter.

Medical students often struggle when presenting new patients to the attending physicians on the ward. Case presentation is either poorly taught or not taught at all in the first two years of medical school. As a result, students are thrust into the spotlight with only sketchy ideas about how to present, prioritize, edit, and focus their case presentations. They also struggle with producing a broad differential diagnosis and defending their leading diagnosis. This text provides a comprehensive guide to give well-prepared, focused and concise presentations. It also allows students to discuss differential diagnosis, incorporate high-value care, educate their colleagues, and participate actively in the care of their patients.

Linking in-depth discussion of the oral presentation with differential diagnosis and high value care, Presenting Your Case is a valuable resource for medical students, clerkship directors and others who educatestudents on the wards and in the clinic.

- Oral case presentation

- Differential Diagnosis

- Five-Minute-Talk

Clifford D. Packer, MD

Professor of Medicine

Department of Medicine

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center

Cleveland, OH, USA

Book Title : Presenting Your Case

Book Subtitle : A Concise Guide for Medical Students

Authors : Clifford D. Packer

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13792-2

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-13791-5 Published: 14 May 2019

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-13792-2 Published: 29 April 2019

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIV, 196

Number of Illustrations : 8 b/w illustrations, 9 illustrations in colour

Topics : General Practice / Family Medicine

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research & Collections

- Borrow & Request

- Computing & Technology

PBL Information Resources and Tools for the First Year: Oral Presentation Resources

- Clinical Resources

- Background Info Resources

- Drug Info Resources

- Current Case

- PBL Case Archive

- Search Tips & Tutorials

- APA Examples

- Numbered Style Example

- What About Citations in Slides?

- Reference : Normal Lab Values

- Oral Presentation Resources

- Write-Ups: Word & PowerPoint Tips

Books Worth Checking Out

Have a resource to share or need something more? Let Karen know .

Oral Presentations

Dr. Konop's Tips

The oral case presentation requires a bit of effort and benefits from repeated practice. You may have questions about what to include and the following resources will help you keep in mind the salient points to cover. Some presentations will be brief - when fewer points will be covered - and some will be longer - where you can cover all of the key points.

- Dr. Goldberg's Tips Don't forget the tips at the end.

- Michigan's State's PBL List (concise) A list with brief details on some points.

- Cornell's Tips for 3rd Year A bit specific to the wards, but some good guidelines to use.

- Drexel's Tip (lots of detail) Including examples, mnemonics & common mistakes. They advise, "an oral case presentation is NOT a simple recitation of your write-up. It is a concise, edited presentation of the most essential information."

Dr. Gates Tip

Dr. Gates found a great form to use as a reminder of what to cover. For those of you that like notes, this will work well, and those of you who just want some structure, it will provide that.

- Oral Presentation as PDF A fill in the blanks form.

- Oral Presentation as Word file A fill in the blanks form where you can enter the patient info.

Quick Reminder:

Don't bury the lead!

In other words, state up front the Chief Complaint . Knowing that will give your listeners the chance to put all the pieces of info that you have to say together in a way that helps them.

For an Alternative Perspective

- BMJ Article on How to Present a Case A bit more detailed (good for clerkship maybe?) but some good tips. Requires a free account to BMJ Student.

- << Previous: Reference : Normal Lab Values

- Next: Write-Ups: Word & PowerPoint Tips >>

- Last Updated: Mar 14, 2024 2:18 PM

- URL: https://ucsd.libguides.com/Foundations

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Oral Case Presentation : A Key Tool for Assessment and Teaching in Competency-Based Medical Education

- 1 Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- 2 Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- 3 HoPingKong Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Oral case presentations by trainees to supervisors are core activities in academic hospitals across all disciplines and form a key milestone in US and Canadian educational frameworks. Yet despite their widespread use, there has been limited attention devoted to developing case presentations as tools for structured teaching and assessment. In this Viewpoint, we discuss the challenges in using oral case presentations in medical education, including lack of standardization, high cognitive demands, and the role of trust between supervisor and trainee. We also articulate how, by addressing these tensions, case presentations can play an important role in competency-based education, both for assessment of clinical competence and for teaching clinical reasoning.

Read More About

Melvin L , Cavalcanti RB. The Oral Case Presentation : A Key Tool for Assessment and Teaching in Competency-Based Medical Education . JAMA. 2016;316(21):2187–2188. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16415

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.115(1); Jan-Feb 2018

Implementation of Oral Case Presentations in an Immunology Course

Implementation of oral case presentations (OCP) in the Immunology course at A.T. Still University–Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine has significantly improved written examination scores and student satisfaction with the course by enhancing its clinical relevance. With six faculty facilitators, an average class size of 172 students can complete the exercise in a single day. The exercise requires small group meeting rooms, each equipped with a computer and wall-mounted monitor, but no other physical resources.

Introduction

The oral case presentation (OCP) is an effective tool for teaching and evaluating medical students as they develop competence in communication skills, medical knowledge, and clinical reasoning. 1 – 3 Although approaches to the OCP may vary, most incorporate elements represented by the mnemonic “SNAPPS,” which refers to summarizing the patient’s history and physical findings, narrowing the differential, analyzing the differential by comparing and contrasting the possible diagnoses, probing for additional information about uncertainties, planning management of the patient’s medical issues, and selecting a case-related issue for self-directed learning. 4 The OCP can be adapted to all stages of medical training, from the pre-clinical years 5 through residency programs. 4 , 6 In this paper, I describe implementation of an OCP exercise in an Immunology course taken by first- or second-year osteopathic medical students at A.T. Still University–Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine (ATSU–KCOM).

The OCP exercise was introduced into the Immunology course in 2011. At that time, Immunology consisted of 21 contact hours, and was by far the shortest course in an academic term that totaled 283 contact hours. Perhaps due in part to its small footprint, Immunology compared unfavorably in student evaluations to larger courses taught during the same term, the largest of which comprised 90 contact hours. To emphasize the importance of Immunology in medical education despite the brevity of the course, the Immunology OCP was implemented with three major goals in mind: 1) to enhance the clinical relevance of material presented during traditional lectures, 2) to improve written examination scores, and 3) to increase student satisfaction with the course. The Immunology OCP exercise was modeled after similar exercises performed in our Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases courses, which have been highly successful in achieving the same goals. 5 Now in its seventh year, the Immunology OCP has a proven record of producing high-yield results while using few faculty and physical resources.

Study Participants

This study received exempt status from the ATSU–KCOM Institutional Review Board. ATSU–KCOM osteopathic medical students participating in the study fell into three experimental groups. Group I students (n=352) took Immunology as a single, comprehensive 21-hour course in Quarter 2 of the curriculum; they did not participate in the Immunology OCP exercise. Group II students (n=335) also took Immunology as a single 21-hour course, but these students participated in the OCP exercise. For Group III students (n=513), curricular changes led to the division of Immunology into an 11-hour foundational course in Semester 1, followed by a 10-hour clinical course in Semester 3. Group III students participated in the OCP exercise during the Semester 3 clinical course. Groups I and II each comprised two classes of students, whereas Group III included students from three classes.

Clinical Cases

All clinical immunology cases were adapted by the author from printed texts, e-books, or reputable on-line resources that describe case studies. 7 – 10 The cases were developed around the chief complaints of abdominal pain, bowel upset, breathing difficulty, cough, diarrhea, joint pain, numbness, and skin lesions. Differential diagnoses included immunodeficiencies, autoimmune diseases, and hypersensitivities. Case packets were created using the template developed by Chamberlain et al. 5 Each packet consisted of 1–3 printed pages containing one or more photographs of the patient; the patient’s chief complaint and associated symptoms; the patient’s history, vital signs and physical examination results; and laboratory and medical procedure data that required interpretation by the student.

Case Presentations

Groups of 5 students and one facilitator were assigned to small group meeting rooms equipped with a computer and wall-mounted monitor. Each student in the group randomly received a unique paper case and had 10 minutes to read and take notes over the data. Students were not allowed to consult reference materials or their peers during the reading period. After returning the case packets to the facilitator, each student gave a 3-minute oral presentation that summarized the main issues of the case, explained the lab and medical procedure data, and explained why each diagnosis in a list of five choices should be ruled in or ruled out. The student was aided during the oral presentation by a PowerPoint slide containing case exhibits, and by the hand-written notes taken during review of the case packet. After the presenting the case and defending the diagnosis, the student spent the next three minutes fielding questions from his or her peers and the facilitator. For each group of five students, the entire exercise required 50 min to complete. Typically, six groups were run simultaneously, allowing 30 students to complete the exercise each hour, and an average class size of 172 students to complete the exercise in a single day.

Student performance was evaluated using a rubric that assessed six microskills: 1) behaving and speaking in a professional manner; 2) adding value to the discussion by asking probing questions of the presenter; 3) covering important aspects of the patient’s signs, symptoms, history and physical; 4) thoroughly explaining laboratory and medical procedure data; 5) justifying why each answer choice in the differential diagnosis list should be ruled in or ruled out; and 6) correctly answering a basic science question associated with the case. The basic science question varied, but often involved asking the presenter to identify the molecular defect causing an immunodeficiency, the molecular target of an autoimmune disease, or the mode of action of an immunotherapeutic treatment. New cases were introduced at planned intervals to minimize the advantage gained by students in later sessions who might unfairly discuss the cases with classmates who completed the exercise earlier in the day.

The OCP exercise was scheduled to take place three to seven days before the last unit examination in the Immunology course. Because the course ends long before the academic term is over, students completed the OCP exercise an average of 4 weeks before they took the Immunology comprehensive final examination at the end of the academic term.

Statistical Analysis of Final Exam Scores and Likert Scale Data

To determine whether the Immunology OCP exercise impacted student learning, scores earned by students on the Immunology comprehensive final examination before (Group I) and after (Groups II and III) implementation of the OCP were compared by one-way ANOVA (P<0.05). Post hoc comparisons were done using the Bonferroni correction to the p-value (P<0.05). The questions on the comprehensive final examinations taken by students in Groups I and II were consistent except for minor changes made for clarity. The comprehensive final exams taken by Group III students largely omitted the basic science questions found on Group I and II final exams, but contained the same clinical questions as before, plus additional clinical questions.

Student satisfaction with the Immunology course before and after implementation of the OCP was evaluated using the 4-point Likert item, “Achievement in this course advances me toward being a physician,” where 1=strongly agree, 2=agree, 3=disagree, and 4=strongly disagree. Likert scores were compared between groups by one-way ANOVA (P<0.05), followed by post hoc comparisons done with the Bonferroni correction to the p-value (P<0.05).

Anonymous Student Comments Regarding the Immunology OCP

Students had the opportunity to express their opinions about the Immunology OCP through anonymous written comments submitted via the on-line Immunology course evaluation. Course evaluations were completed after students had taken the Immunology comprehensive final examination at the end of the academic term.

Students who participated in the Immunology OCP (Groups II and III) scored significantly higher on the Immunology comprehensive final examination than Group I students, who did not participate in the exercise (one-way ANOVA, P<0.001; Bonferroni post hoc test, P<0.001) ( Table 1 ). Among students who took Immunology as a single 21-hour course, the mean final exam score improved from 76.5% (Group I) to 81.8% (Group II) upon implementation of the Immunology OCP. Between the two groups of students who participated in the OCP, those who took the 10-hour clinical Immunology course in Semester 3 (Group III) scored significantly higher on the comprehensive final exam than those who took Immunology as a single, 21-hour course in Quarter 2 or 3 (Group II) (one-way ANOVA, P<0.001; Bonferroni post hoc test, P<0.001) ( Table 1 ). Final exam scores earned by Group II and Group III were 81.8% and 87.0%, respectively.

Comparison of mean comprehensive final examination scores in Immunology before (Group I) and after (Groups II and III) implementation of Immunology Case Presentations.

Student satisfaction with the Immunology course, as assessed using the Likert item, “Achievement in this course advances me toward being a physician,” also significantly improved upon implementation of the OCP ( Table 2 ). Students who participated in the OCP (Groups II and III) strongly agreed with the statement, reflected by Likert scores of 1.21 and 1.18, respectively. Both scores were significantly better than the 1.78 rating conferred by Group I students, who did not participate in the OCP (one-way ANOVA, P<0.001; Bonferroni post hoc test, P<0.001). There was no significant difference in Likert scores between Groups II and III (one-way ANOVA, P<0.001; Bonferroni post hoc test, P=0.94).

Comparison of mean Likert scores far the statement, “Achievement in this course advances me toward being a physician,” before (Group I) and after (Groups II and III) implementation of Immunology Case Presentations. a

In general, anonymous student comments submitted as part of the Immunology course evaluation were positive toward the OCP exercise ( Table 3 ). Negative comments focused on the perception that some facilitators tended to give lower scores than others, and that cases or case-associated basic science questions were not uniform in difficulty.

A sampling of anonymous student comments written about the Immunology OCP, reprinted from Immunology course evaluations.

Since introducing the oral case presentations exercise into the Immunology course at ATSU–KCOM, comprehensive final examination scores and student satisfaction with the course have improved significantly. Final exam scores have risen from the mid-70 percent range earned by students who did not participate in the Immunology OCP, to the low- or mid-80 percent range earned by students who did participate in the exercise. With implementation of the OCP, concurrence with the statement, “Achievement in this course advances me toward being a physician,” has improved from “agree” to “strongly agree” in student ratings. Students report that the OCP allows them to integrate basic science knowledge into a clinical setting and helps them think like physicians. Such statements are taken as evidence that the OCP enhances the clinical relevance of the lecture-based material that comprises the bulk of the Immunology course.

As expected, students reported that the OCP made them feel better prepared for the unit exam that came three to seven days after the OCP exercise. Somewhat surprising was the persistence of the exercise’s beneficial effect through the end of the academic term, resulting in higher scores on the Immunology comprehensive final exam taken one month after completion of the OCP exercise than in years prior to OCP implementation. The lasting impact of the OCP on student learning was also reflected in student perceptions of preparedness for the COMLEX Level 1 board examination, which is taken at the end of the second year of osteopathic medical education. Since implementing the Immunology OCP, 94% to 99% of students have reported feeling adequately to extremely well-prepared in Immunology for the COMLEX Level 1 exam, up from a low of 68% before the OCP exercise was introduced. Graffam 11 notes that intentional engagement and active learning change the nature of learning in such a way that knowledge gain and recall abilities are improved, an assertion supported by our experience with the Immunology OCP exercise.

It should be noted that the Immunology final exams given to students in Groups I and II varied little from year to year, enabling direct comparison of exam scores between these two groups. However, the curricular changes that divided Immunology into separate foundational and clinical courses necessitated changes to the final exam taken by students in Group III. For all three groups, the same core clinical questions were asked on the final exam, but the Group III exam contained additional clinical questions and omitted questions covering basic immunological concepts. Fewer lectures were covered on the Group III exam, resulting in less material to study. A more important advantage enjoyed by Group III students was the timing of the Immunology final exam, which came later in their medical education. Exposure to additional coursework allowed Group III students to make connections between knowledge gained in Immunology with knowledge gained from the Pathology and Medicine courses. Inshort, the improvement seen in Group III Immunology comprehensive final examination scores most likely derived from a combination of factors, including the Immunology OCP.

Onishi 12 distinguishes between OCP exercises that have short (1–2 minutes) and long (5–10 minutes) formats. To improve clinical reasoning, the short presentation offers the advantages of requiring abstraction of information, time efficiency, and fostering informal interactions with the audience. 12 Long presentations allow educators to be more involved in the diagnostic reasoning process as they listen to detailed descriptions of the patient’s signs and symptoms. 12 A frequently used short-format case presentation is the One-Minute Preceptor (OMP), which employs six microskills. 4 These include requiring the student to commit to a diagnosis, probing for supporting evidence, teaching general rules, reinforcing what is right, correcting mistakes, and identifying the next learning steps. 4 The Immunology OCP used a mixed approach, falling between the short and long case presentation formats while blending elements of SNAPPS and the OMP, with good results.

Although students expressed concern that some facilitators graded more harshly than others during the OCP, steps were taken to minimize inter-rater variability. In all three courses where we use OCP exercises, we have found that a useful method for reducing inconsistencies is to enter the data for each case into a spread sheet, so that the scores assigned to each item in the grading rubric can be compared across facilitators by a single evaluator. Adjustments are made if discrepancies are found in the number of points deducted by different facilitators for the same infraction. Using this method, the mean scores across all facilitators typically differ by less than 5%. Although the perfect evaluation instrument for the OCP has yet to be developed, 13 – 15 our simplified rubric, in conjunction with written comments made by the facilitators, provides valuable feedback to the students as they develop oral case presentation skills.

Conclusions

Introduction of the oral case presentations exercise into the Immunology course at ATSU–KCOM has enhanced the clinical relevance of material presented during traditional lectures, improved retention of basic science and medical knowledge, and increased student satisfaction with their educational experience. The Immunology OCP complements similar exercises we conduct in our Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases courses. Together, these three courses have fostered development of oral communication and clinical reasoning skills that will serve our students well during their third and fourth years of medical training.

Acknowledgments

The oral case presentations exercise would not be possible without the cooperation and dedication of the entire Department of Microbiology/Immunology faculty and staff at ATSU–KCOM. Additional thanks go to Shalini Bhatia, Biostatistician, for advice on statistics, and to Patricia Sexton, DHEd, Associate Dean for Curriculum, and Neal Chamberlain, PhD, Professor of Microbiology/Immunology, for critical reading of the manuscript.

Melissa K. Stuart, PhD, Department of Microbiology/Immunology, is at Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine, A.T. Still University, Kirksville, Missouri.

Contact: ude.usta@trautsm

None reported.

- Open access

- Published: 24 May 2023

Comparing oral case presentation formats on internal medicine inpatient rounds: a survey study

- Brendan Appold 1 ,

- Sanjay Saint 1 , 2 ,

- David Ratz 2 &

- Ashwin Gupta 1 , 2

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 377 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2672 Accesses

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Oral case presentations – structured verbal reports of clinical cases – are fundamental to patient care and learner education. Despite their continued importance in a modernized medical landscape, their structure has remained largely unchanged since the 1960s, based on the traditional Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) format developed for medical records. We developed a problem-based alternative known as Events, Assessment, Plan (EAP) to understand the perceived efficacy of EAP compared to SOAP among learners.

We surveyed (Qualtrics, via email) all third- and fourth-year medical students and internal medicine residents at a large, academic, tertiary care hospital and associated Veterans Affairs medical center. The primary outcome was trainee preference in oral case presentation format. The secondary outcome was comparing EAP and SOAP on 10 functionality domains assessed via a 5-point Likert scale. We used descriptive statistics (proportion and mean) to describe the results.

The response rate was 21% (118/563). Of the 59 respondents with exposure to both the EAP and SOAP formats, 69% ( n = 41) preferred the EAP format as compared to 19% ( n = 11) who preferred SOAP ( p < 0.001). EAP outperformed SOAP in 8 out of 10 of the domains assessed, including advancing patient care, learning from patients, and time efficiency.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that trainees prefer the EAP format over SOAP and that EAP may facilitate clearer and more efficient communication on rounds, which in turn may enhance patient care and learner education. A broader, multi-center study of the EAP oral case presentation will help to better understand preferences, outcomes, and barriers to implementation.

Peer Review reports

Excellent inter-physician communication is fundamental to both providing high-quality patient care and promoting learner education [ 1 ], and has been recognized as an important educational goal by the Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ 2 ]. Oral case presentations, structured verbal reports of clinical cases [ 3 ], have been referred to as the “currency with which clinicians communicate” [ 4 ]. Oral case presentations are a key element of experiential learning in clinical medicine, requiring learners to synthesize, assess, and convey pertinent patient information and to formulate care plans. Furthermore, oral case presentations allow supervising clinicians to identify gaps in knowledge or clinical reasoning and enable team members to learn from one another. Despite modernization in much of medicine, oral case presentation formats have remained largely unchanged, based on the traditional Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan (SOAP) format developed by Dr. Lawrence Weed in his Problem Oriented Medical Record in 1968 [ 5 ].

Given that the goals of a medical record are different than those of oral case presentations, it should not be assumed that they should share the same format. While Dr. Weed sought to make the medical record as “complete as possible,” [ 6 ] internal medicine education leaders have expressed desire for oral case presentations that are succinct, with an emphasis on select relevant details [ 2 ]. Using a common SOAP format between the medical record and oral case presentations risks conflating the distinct goals for each of these communication methods. Indeed, in studying how learners gain oral case presentation skills, Haber and Lingard [ 7 ] found differences in understanding of the fundamental purpose of oral case presentations between medical students and experienced physicians. While students believed the purpose of oral case presentations was to organize the large amount of data they collected about their patients, experienced physicians saw oral case presentations as a method of telling a story to make an argument for a particular conclusion [ 7 ].

In accordance with Dr. Weed’s “problem-oriented approach to data organization,” [ 6 ] but with an eye toward optimizing for oral case presentations, we developed an alternative to SOAP known as the Events, Assessment, Plan (EAP) format. The EAP format is used for patients who are already known to the inpatient team, and may also be utilized for newly admitted patients for whom the attending physician already has context (e.g., via handoff or review of an admission note). As the EAP approach is utilized by a subset of attending physicians at our academic hospital, we sought to understand the perceived effectiveness of the EAP format in comparison to the traditional SOAP format among learners (i.e., medical students and resident physicians).

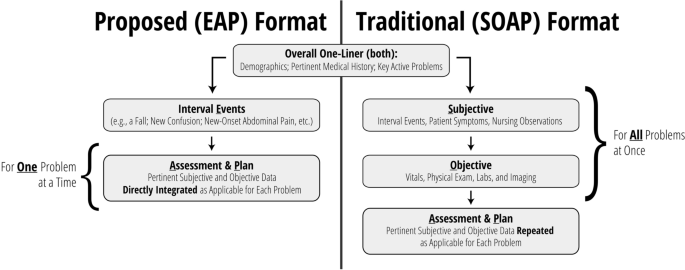

EAP is a problem-based format used at the discretion of the attending physician. In line with suggested best practices [ 8 ], the EAP structure aims to facilitate transmission of data integrated within the context of clinical problem solving. In this format, significant interval events are discussed first (e.g., a fall, new-onset abdominal pain), followed by a prioritized assessment and plan for each relevant active problem. Subjective and objective findings are integrated into the assessment and plan as relevant to a particular problem. This integration of subjective and objective findings by problem is distinct from SOAP, where subjective and objective findings are presented separately as their own sections, with each section often containing information that is relevant to several problems (Fig. 1 , Additional file 1 : Appendix A).

Overview: comparing EAP to SOAP

Settings and participants

We surveyed third- and fourth-year medical students, and first- through fourth-year internal medicine and internal medicine-pediatrics residents, caring for patients at a large, academic, tertiary care hospital and an affiliated Veterans Affairs medical center. Internal medicine is a 12-week core clerkship for all medical students in their second year, with 8 weeks spent on the inpatient wards. All student participants had completed their internal medicine clerkship rotation at the time of the survey. We did not conduct a sample size calculation at the outset of this study.

Data collection methods and processes

An anonymous, electronic survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) was created to assess student and resident experience with and preference between EAP and SOAP oral case presentation formats during inpatient internal medicine rounds (Additional file 2 : Appendix B). Ten domains were assessed via 5-point Likert scale (1 [strongly disagree] to 5 [strongly agree]), including the ability of the format to incorporate the patient’s subjective experience, the extent to which the format encouraged distillation and integration of information, the extent to which the format focused on the assessment and plan, the format’s ability to help trainees learn from their own patients and those of their peers, time efficiency, and ease of use. Duration of exposure to each format was also assessed, as were basic demographic data for the purposes of understanding outcome differences among respondents (e.g., students versus residents). For those who had experienced both formats, preference between formats was recorded as a binary choice. Participants additionally had the opportunity to provide explanation via free text. For participants with experience in both formats, the order of evaluation of EAP and SOAP formats were randomized by participant. For questions comparing EAP and SOAP formats directly, choice order was randomized.

The survey was distributed via official medical school email in October 2021 and was available to be completed for 20 days. Email reminders were distributed approximately one week after distribution and again 48 h prior to survey conclusion.

The primary outcome was trainee preference in oral case presentation format. Secondary outcomes included comparison between EAP and SOAP on content inclusion/focus, data integration, learning, time efficiency, and ease of use.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the results (proportion and mean). For comparative analysis between EAP and SOAP, responses from respondents who had experience with both formats were compared using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test to evaluate differences. All statistical analyses were done using SAS V9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We considered p < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

The overall response rate was 21% (118/563). The response rate was 14% ( n = 62/441) among medical students and 46% ( n = 56/122) among residents. Respondents were 61% ( n = 72) female. A total of 98% ( n = 116) and 52% ( n = 61) of respondents reported experience with SOAP and EAP formats, respectively. Among medical students, 60% ( n = 37) reported experience with SOAP only while 39% ( n = 24) had experience with both formats. Among residents, 36% ( n = 20) and 63% ( n = 35) had experience with SOAP only and both formats, respectively (Table 1 ). Most students (93%) and residents (96%) reported > 8 weeks of exposure to the SOAP format. Duration of exposure to the EAP format varied (0 to 2 weeks [32% of students, 17% of residents], 2 to 4 weeks [36% of students, 47% of residents], 4 to 8 weeks [16% of students, 25% of residents], and > 8 weeks [16% of students, 11% of residents]).

Of the 59 respondents with exposure to both the SOAP and EAP formats, 69% ( n = 41) preferred the EAP format as compared to 19% ( n = 11) preferring SOAP ( p < 0.001). The remainder ( n = 7, 12%) indicated either no preference between formats or indicated another preference. Among residents, 66% ( n = 23) favored EAP, whereas 20% ( n = 7) and 14% ( n = 5) preferred SOAP or had no preference, respectively ( p < 0.001). Among students, 75% ( n = 18) favored EAP, whereas 17% ( n = 4) and 8% ( n = 2) favored SOAP or had no preference, respectively ( p < 0.001).

Likert scale ratings for domains assessed by trainees who had experience in either format are shown in Table 2 . In general, scores for each domain were higher for EAP than SOAP, with the exception of perceived ease of use among students. Among those with experience using both formats, EAP outperformed SOAP most prominently in time efficiency (mean 4.39 vs 2.59, p < 0.001) and encouragement to: focus on assessment and plan (4.64 vs 3.05, p < 0.001), distill pertinent information (4.63 vs 3.17, p < 0.001), and integrate data (4.58 vs 3.31, p < 0.001) (Table 3 ). Respondents also ranked EAP higher in its effectiveness at advancing patient care (4.31 vs 3.71, p < 0.001), its capacity to convey one’s thinking (4.53 vs 3.95, p < 0.001), and its ability to facilitate learning from peers (4.10 vs 3.58, p < 0.001) and one’s own patients (4.24 vs 3.78, p = 0.003). There were no significant differences in the amount of time allotted for discussing the patient’s subjective experience or in ease of use.

Evaluation of trainee free text responses regarding oral case presentation preference revealed several general themes (Table 4 ). First, respondents generally felt that EAP was more time efficient and less repetitive, allowing for additional time to be spent discussing pertinent patient care decisions. Second, several respondents indicated that EAP aligns well with how trainees consider problems naturally (as a single problem in completion). Finally, respondents generally believed that EAP allowed learners to effectively communicate their thinking and demonstrate their knowledge. Those preferring SOAP most often cited format familiarity and the difficulty in switching between formats in describing their preference, though some also believed SOAP was more effective in describing a patient’s current status.

Our single site survey comparing 2 oral case presentation formats revealed a preference among respondents for EAP over SOAP for those medical students and internal medicine residents who had experience with both formats. Furthermore, EAP outperformed SOAP in 8 out of 10 of the functionality domains assessed, including areas such as advancing patient care, learning from patients, and, particularly, time efficiency. Such a constellation of findings implies that EAP may not only be a more effective means to accomplish the key goals of oral case presentations, but it may also provide an opportunity to save time in the process. In line with SOAP’s current de facto status as an oral case presentation format, almost all respondents reported exposure to the SOAP format. Still, indicative of EAP’s growing presence at our academic system, more than one third of medical students and more than one half of residents also reported having experience with the EAP format.

While limited data exist that compare alternative oral case presentations to SOAP on inpatient medicine rounds, such alternatives have been previously trialed in other clinical venues. One such format, the multiple mini-SOAP, developed for complex outpatient visits, encourages each problem to be addressed “in its entirety” before presenting subsequent problems, and emphasizes prioritization by problem pertinency [ 9 ]. The creators suggest that this approach encourages more active trainee participation in formulating the assessment and plan for each problem, by helping the trainee to avoid getting lost in an “undifferentiated jumble of problems and possibilities” [ 9 ] that accumulate when multiple problems are presented all at once. On the receiving end, the multiple mini-SOAP enables faculty to assess student understanding of specific clinical problems one at a time and facilitates focused teaching accordingly.

Another approach has been assessed in the emergency department. Specifically, Maddow and colleagues explored assessment-oriented oral case presentations to increase efficiency in communication between residents and faculty at the University of Chicago [ 10 ]. In the assessment-oriented format, instead of being presented in a stylized order, pertinent information was integrated into the analysis. The authors found that assessment-oriented oral case presentations were about 40% faster than traditional presentations without significant differences in case presentation effectiveness.

Prior to our study, the nature of the format for inpatient medicine oral case presentations had thus far escaped scrutiny. This is despite the fact that oral case presentations are time (and therefore resource) intensive, and that they play an integral role in patient care and learner education. Our study demonstrates that learners favor the EAP format, which has the potential to increase both the effectiveness and efficiency of rounding.

Still, it should be noted that a transition to EAP does present challenges. Implementing this problem-based presentation format requires a conscious effort to ensure a continued holistic approach to patient care: active problems should be defined and addressed in accordance with patient preferences, and the patient’s subjective experience should be meaningfully incorporated into the assessment and plan for each problem. During initial implementation, attending physicians and learners must internalize this new format, often through trial and error.

From there, on an ongoing basis, EAP may require more upfront preparation by attending physicians as compared to SOAP. While chart review by attendings in advance of rounding is useful regardless of the format utilized, this practice is especially important for the EAP format, where trainees are empowered to interpret and distill – rather than simply report a complete set of – information. Therefore, the attending physician must be aware of pertinent data prior to rounds to ensure that key information is not neglected. Specifically, attendings should pre-orient themselves with laboratory values, imaging, and other studies completed, and new suggestions from consultants. More extensive pre-work may be required if teams wish to employ the EAP format for newly admitted patients, as attending physicians must also familiarize themselves with a patient’s medical history and their current presentation prior to initial team rounds.

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of specific limitations. First, low response rates may have led to selection bias within our surveyed population. For instance, learners who desired change in the oral case presentation format may have been more motivated to engage with our survey. Second, there could be unmeasured confounding variables that could have skewed our results in favor of the EAP format. For example, attendings who utilized the EAP format may have been more likely to innovate in other ways to create a more positive experience for learners, which may have influenced the scoring of the oral case presentation format. Third, our findings were largely based on subjective experience. Objective measurement (e.g., duration of rounds, patient care outcomes) may lend additional credibility to our findings. Lastly, our study included only a single site, limiting our ability to generalize our findings.

Our study also had several strengths. Our learner participant pool was broad and included all third- and fourth-year medical students and all internal medicine residents at a major academic hospital. Participation was encouraged regardless of the nature of a participant’s prior exposure to different oral case presentation formats. Our survey was anonymous with randomization to mitigate order bias, and we focused our comparison analysis on those who had exposure to both the EAP and SOAP formats. We collected data to compare EAP with SOAP in 2 distinct ways: head-to-head preference and numeric ratings amongst key domains. Both of these methods demonstrated a significant preference for EAP among learners in aggregate, as well as for students and residents analyzed independently.

Our findings suggest a preference for the EAP format over SOAP, and that EAP may facilitate clearer and more efficient communication on rounds. These improvements may in turn enhance patient care and learner education. While our preliminary data are compelling, a broader, multi-center study of the EAP oral case presentation is necessary to better understand preferences, outcomes, and barriers to implementation. Further studies should seek to improve response rates, for the data to represent a larger proportion of trainees. One potential strategy to improve response rates among medical students and residents is to survey them directly at the end of each internal medicine clerkship period or rotation, respectively. Ultimately, EAP may prove to be a much-needed update to the “currency with which clinicians communicate.”

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AG, upon reasonable request.

Kihm JT, Brown JT, Divine GW, Linzer M. Quantitative analysis of the outpatient oral case presentation: piloting a method. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(3):233–6.

Article Google Scholar

Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):370–3.

Daniel M, Rencic J, Durning SJ, Holmboe E, Santen SA, Lang V, et al. Clinical Reasoning Assessment Methods: A Scoping Review and Practical Guidance. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):902–12.

Lewin LO, Beraho L, Dolan S, Millstein L, Bowman D. Interrater reliability of an oral case presentation rating tool in a pediatric clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(1):31–8.

Wright A, Sittig DF, McGowan J, Ash JS, Weed LL. Bringing science to medicine: an interview with Larry Weed, inventor of the problem-oriented medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(6):964–8.

Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. New Engl J Med. 1968;278(12):652–7.

Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills: a rhetorical analysis with pedagogical and professional implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(5):308–14.