Definition of Pathos

Pathos is a literary device that is designed to inspire emotions from readers. Pathos, Greek for “suffering” or “experience,” originated as a conceptual mode of persuasion by the Greek philosopher, Aristotle. Aristotle believed that utilizing pathos as a means of stirring people’s emotions is effective in turning their opinion towards the speaker . This is due in part because emotions and passion can be engulfing and compelling, even going against a sense of logic or reason.

Pathos, as an appeal to an audience ’s emotions, is a valuable device in literature as well as rhetoric and other forms of writing. Like all art, literature is intended to evoke a feeling in a reader and, when done effectively, generate greater meaning and understanding of existence. For example, in his poem “No Man Is an Island,” John Donne appeals to the reader’s emotions of acceptance, belonging, and empathy:

No man is an island, Entire of itself, Every man is a piece of the continent, A part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less. As well as if a promontory were. As well as if a manor of thy friend’s Or of thine own were: Any man’s death diminishes me, Because I am involved in mankind, And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls ; It tolls for thee.

By describing how all men are connected rather than isolated, Donne utilizes pathos as an emotional appeal to readers of his poem. The feelings evoked by the poet are grief and sympathy for all who die, because all death is an individual loss and a loss for mankind as a whole.

Common Examples of Emotions Evoked by Pathos

Pathos has the power to evoke many emotions in a reader or audience of a literary work. Here are some common examples of emotions evoked by pathos in literature:

Examples of Pathos in Advertisement

Advertisers heavily rely on pathos to provoke an emotional reaction in an audience of consumers, thereby persuading them to take action in the form of patronage or other monetary support. Here are some examples of pathos in an advertisement:

- television commercial showing neglected or mistreated animals

- political ad utilizing fear tactics

- holiday commercial showing a family coming together for a meal

- cologne commercial displaying sexual tension

- diaper ad featuring a crying baby

- ad for cleaning product featuring a messy house and frustrated homeowner

- jewelry commercial showing a marriage proposal

- insurance ad showing a terrible car accident

- ad for a line of toys showing children playing together

- commercial for make-up displaying a woman receiving attention from men

Famous Examples of Pathos in Movie Lines

Many films feature dialogue that generates pathos and emotional reactions in viewers. Here are some famous examples of pathos in well-known movie lines:

- Love means never having to say you’re sorry. (Love Story )

- The jail you planned for me is the one you’re gonna rot in. ( The Color Purple )

- I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore. (Network)

- The marks humans leave are too often scars. (The Fault in Our Stars)

- I have to remind myself that some birds aren’t meant to be caged. (The Shawshank Redemption)

- And just like that, she was gone, out of my life again. (Forrest Gump)

- There are two types of people in the world: The people who naturally excel at life. And the people who hope all those people die in a big explosion. (The Edge of Being Seventeen)

- You have to get through your fear to see the beauty on the other side. (The Good Dinosaur)

- Hate never solved nothing, but calm did. And thought did. Try it. Try it just for a change . (Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri)

- Things change, friends leave. And life doesn’t stop for anybody. (The Perks of Being a Wallflower)

Difference Between Pathos, Logos, and Ethos

Aristotle outlined three forms of rhetoric, which is the art of effective speaking and writing. These forms are pathos, logos , and ethos . As a matter of rhetorical persuasion, it is important for these forms (or “appeals”) to be balanced. This is especially true for pathos in that overuse of emotional appeal can lead to a flawed argument without the balance of logic or credibility.

Logos is an appeal to logic. It is considered a methodical and rational approach to rhetoric. In a sense, logos is an appeal that is devoid of pathos. Ethos is an appeal to ethics. As an effective rhetorical form, a writer or speaker must have knowledge and credibility regarding the subject . Ethos, therefore, builds trust with an audience as an ethical and character -driven approach.

Pathos is a common form of rhetoric and persuasive tactic. Emotion and passion can be powerful forces in motivating an audience or readership. However, pathos has minimal effect without the balance of logos and ethos as appeals.

Effect of Pathos on Logos

Aa a logo appeals to logic, and pathos appeals to emotions. It is a well-known fact that not everybody gets convinced by logic and the same is the case of pathos which not everybody gets convinced with pathos only. Therefore, orators and speakers use both in a combination. When a pathos is added to logos, it becomes convincing, persuasive, strong, and touches beliefs and values.

Effect of Pathos on Ethos

Although ethos is itself a strong rhetorical device and works wonders when it comes to persuasion and convincing the audience, when a touch of pathos is added to it, it becomes a lethal weapon. It has happened in I Have a Dream , a powerful rhetorical piece of Martin Luther King and the speech is still a memorable rhetorical piece. The reason is that not only does it enhance the power of argument when added with an ethos, it also increases the trust and credibility of the speaker or orator.

How To Build Arguments Using Pathos

When using pathos, keep these points in mind.

- What is the touching event for the audience?

- Evaluate how the audiences or readers respond to the gravity of the situation?

- Use pathos with ethos first and then use l0gos to add pathos later.

- Pathos is always the last weapon after ethos and logos.

Fallacy Of Emotion (Pathos) / Fallacious Pathos

As pathos is also called a fallacy of emotion, the use of only pathos is highly damaging for argumentative writing and speaking. The reason is that audiences if they are not directly concerned with the pathetic event or tragedy , become bored with excessive targetting of their emotions and eventually lose interest. At this point, it becomes a fallacy. Therefore, always avoid fallacious pathos. Add a touch of veracity to your pathos and use it in conjunction with ethos first and add logos later.

Three Characteristics Of Pathos

There are three important characteristics of pathos.

- It is relevant to the target audience or readers and is couched in simple and strong language.

- It is intended to achieve a specific purpose.

- It is not excessive that it should become fallacious pathos.

Using Pathos in Sentences

- The Holocaust has done more harm to the entire Jewish nation than any other such event.

- If you love me, you’ll get me a cell phone for my safety.

- I have to pick up my children from school every day, can you give me a good deal on this car?

- Look at these innocent street children. By seeing this, you can give us good donations.

- If you let me eat chips everyday, it will prove that you love me and I will do the dishes.

Examples of Pathos in Literature

Though Aristotle defined pathos as a rhetorical technique for persuasion, literary writers rely on pathos as well to evoke emotion and understanding in readers. As a literary device, pathos allows readers to connect to and find meaning in characters and narratives. Here are some examples of pathos in literature and the impact this literary device has on the work and the reader:

Example 1: Funeral Blues by W.H. Auden

He was my North, my South, my East and West, My working week and my Sunday rest, My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song; I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong. The stars are not wanted now ; put out every one, Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun, Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood; For nothing now can ever come to any good.

In his poem, Auden relies on pathos as a literary device to evoke feelings of grief and inspire sympathy in the reader. The poet cannot cope with the loss of his loved one and companion, yet the world around him continues to function as if nothing is different and as if the funeral is not taking place. The poet’s passion for his loved one, that he was all cardinal directions and days and times, followed by the poet’s desperation to remove elements of nature, inspires sympathetic mourning in readers.

Though the poet cannot get the world to pause in grief for his loved one, by utilizing pathos as a literary device in this poem, Auden is able to momentarily capture the reader’s attention and understanding. This pause for grief and sympathy on the part of the reader fulfills, on some level, the emotional need of the poet to be recognized and validated in his mourning. This reciprocal exchange of feeling enhances the connection between the poet and reader through pathos.

Example 2: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

If growing up is painful for the Southern Black girl, being aware of her displacement is the rust on the razor that threatens the throat. It is an unnecessary insult.

In her memoir , Angelou focuses on the emotional events of her life from early childhood through adolescence. While recounting her story, Angelou utilizes pathos to appeal to the reader’s emotions and to evoke empathy for her experiences, especially in terms of trauma, abuse, and racism.

In this particular passage from her memoir, Angelou appeals to the reader’s feelings of shame, empathy, and fear by describing her experience and how she felt as a Black girl growing up in the South. This allows the reader to connect with and find meaning in Angelou’s writing and experiences, especially if those experiences are unfamiliar or personally unknown to the reader. In addition, the pathos in this passage is an effective literary device through confronting the reader with the pain, displacement, and insult experienced not just by Angelou as a Southern Black girl, but in a generalized manner for all Southern Black girls. Angelou’s readers are therefore encouraged through pathos to identify this experience and share in the resulting emotional anger and pain.

Example 3: Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Two households, both alike in dignity In fair Verona, where we lay our scene From ancient grudge break to new mutiny Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the fatal loins of these two foes A pair of star- cross ’d lovers take their life Whose misadventured piteous overthrows Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

In the prologue , Shakespeare foreshadows the events that take place in the play between Romeo and Juliet and their families. He also foreshadows the feelings and struggles of the characters, which is an appeal to the pathos of the audience/reader. For example, by stating that “civil blood makes civil hands unclean,” Shakespeare evokes feelings of dread and uncertainty in the audience, knowing that there is impending violence. By categorizing Romeo and Juliet as “star-crossed” lovers, Shakespeare appeals to the audience’s feelings of passion and unrequited love. Finally, in announcing the deaths of the lovers, Shakespeare inspires sadness, grief, and possibly anger or frustration in the audience at the foretold outcome.

With these emotional appeals in his prologue, Shakespeare not only prepares his audience for what is to come in the plot of the play but also sets the tone and prepares the appropriate emotional reactions for the audience to the events that will happen. This is a unique use of pathos as a literary device. Rather than allowing the audience to feel and react to the play’s narrative as it unfolds, Shakespeare “primes” emotional responses through pathos before the play even begins. This technique is effective because the audience is able to focus on the nuances of the play since they are already aware of the main events and outcomes, as well as how to feel about it.

Synonyms of Pathos

Pathos has a few synonyms that follow but they are only distant meanings. Some of them are tragedy, sadness, pitifulness, piteousness, sorrowfulness, lugubrious, poignant, and poignancy.

Related posts:

- Et Tu, Brute?

Post navigation

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

Pathos Definition

What is pathos? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Pathos , along with logos and ethos , is one of the three "modes of persuasion" in rhetoric (the art of effective speaking or writing). Pathos is an argument that appeals to an audience's emotions. When a speaker tells a personal story, presents an audience with a powerful visual image, or appeals to an audience's sense of duty or purpose in order to influence listeners' emotions in favor of adopting the speaker's point of view, he or she is using pathos .

Some additional key details about pathos:

- You may also hear the word "pathos" used to mean "a quality that invokes sadness or pity," as in the statement, "The actor's performance was full of pathos." However, this guide focuses specifically on the rhetorical technique of pathos used in literature and public speaking to persuade readers and listeners through an appeal to emotion.

- The three "modes of persuasion"— pathos , logos , and ethos —were originally defined by Aristotle.

- In contrast to pathos, which appeals to the listener's emotions, logos appeals to the audience's sense of reason, while ethos appeals to the audience based on the speaker's authority.

- Although Aristotle developed the concept of pathos in the context of oratory and speechmaking, authors, poets, and advertisers also use pathos frequently.

Pathos Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce pathos : pay -thos

Pathos in Depth

Aristotle (the ancient Greek philosopher and scientist) first defined pathos , along with logos and ethos , in his treatise on rhetoric, Ars Rhetorica. Together, he referred to pathos , logos , and ethos as the three modes of persuasion, or sometimes simply as "the appeals." Aristotle defined pathos as "putting the audience in a certain frame of mind," and argued that to achieve this task a speaker must truly know and understand his or her audience. For instance, in Ars Rhetorica, Aristotle describes the information a speaker needs to rile up a feeling of anger in his or her audience:

Take, for instance, the emotion of anger: here we must discover (1) what the state of mind of angry people is, (2) who the people are with whom they usually get angry, and (3) on what grounds they get angry with them. It is not enough to know one or even two of these points; unless we know all three, we shall be unable to arouse anger in any one.

Here, Aristotle articulates that it's not enough to know the dominant emotions that move one's listeners: you also need to have a deeper understanding of the listeners' values, and how these values motivate their emotional responses to specific individuals and behaviors.

Pathos vs Logos and Ethos

Pathos is often criticized as being the least substantial or legitimate of the three persuasive modest. Arguments using logos appeal to listeners' sense of reason through the presentation of facts and a well-structured argument. Meanwhile, arguments using ethos generally try to achieve credibility by relying on the speaker's credentials and reputation. Therefore, both logos and ethos may seem more concrete—in the sense of being more evidence-based—than pathos, which "merely" appeals to listeners' emotions. But people often forget that facts, statistics, credentials, and personal history can be easily manipulated or fabricated in order to win the confidence of an audience, while people at the same time underestimate the power and importance of being able to expertly direct the emotional current of an audience to win their allegiance or sympathy.

Pathos Examples

Pathos in literature.

Characters in literature often use pathos to convince one another, or themselves, of a certain viewpoint. It's important to remember that pathos , perhaps more than the other modes of persuasion, relies not only on the content of what is said, but also on the tone and expressiveness of the delivery . For that reason, depictions of characters using pathos can be dramatic and revealing of character.

Pathos in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice

In this example from Chapter 16 of Pride and Prejudice , George Wickham describes the history of his relationship with Mr. Darcy to Elizabeth Bennet—or at least, he describes his version of their shared history. Wickham's goal is to endear himself to Elizabeth, turn her against Mr. Darcy, and cover up the truth. (Wickham actually squanders his inheritance from Mr. Darcy's father and, out of laziness, turns down Darcy Senior's offer help him obtain a "living" as a clergyman.)

"The church ought to have been my profession...had it pleased [Mr. Darcy]... Yes—the late Mr. Darcy bequeathed me the next presentation of the best living in his gift. He was my godfather, and excessively attached to me. I cannot do justice to his kindness. He meant to provide for me amply, and thought he had done it; but when the living fell it was given elsewhere...There was just such an informality in the terms of the bequest as to give me no hope from law. A man of honor could not have doubted the intention, but Mr. Darcy chose to doubt it—or to treat it as a merely conditional recommendation, and to assert that I had forfeited all claim to it by extravagance, imprudence, in short any thing or nothing. Certain it is, that the living became vacant two years ago, exactly as I was of an age to hold it, and that it was given to another man; and no less certain is it, that I cannot accuse myself of having really done anything to deserve to lose it. I have a warm, unguarded temper, and I may perhaps have sometimes spoken my opinion of him, and to him, too freely. I can recall nothing worse. But the fact is, that we are very different sort of men, and that he hates me." "This is quite shocking!—he deserves to be publicly disgraced." "Some time or other he will be—but it shall not be by me. Till I can forget his father, I can never defy or expose him." Elizabeth honored him for such feelings, and thought him handsomer than ever as he expressed them.

Here, Wickham claims that Darcy robbed him of his intended profession out of greed, and that he, Wickham, is too virtuous to reveal Mr. Darcy's "true" nature with respect to this issue. By doing so, Wickham successfully uses pathos in the form of a personal story, inspiring Elizabeth to feel sympathy, admiration, and romantic interest towards him. In this example, Wickham's use of pathos indicates a shifty, manipulative character and lack of substance.

Pathos in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter

In The Scarlet Letter , Hawthorne tells the story of Hester Prynne, a young woman living in seventeenth-century Boston. As punishment for committing the sin of adultery, she is sentenced to public humiliation on the scaffold, and forced to wear the scarlet letter "A" on her clothing for the rest of her life. Even though Hester's punishment exposes her before the community, she refuses to reveal the identity of the man she slept with. In the following passage from Chapter 3, two reverends—first, Arthur Dimmesdale and then John Wilson—urge her to reveal the name of her partner:

"What can thy silence do for him, except it tempt him—yea, compel him, as it were—to add hypocrisy to sin? Heaven hath granted thee an open ignominy, that thereby thou mayest work out an open triumph over the evil within thee and the sorrow without. Take heed how thou deniest to him—who, perchance, hath not the courage to grasp it for himself—the bitter, but wholesome, cup that is now presented to thy lips!’ The young pastor’s voice was tremulously sweet, rich, deep, and broken. The feeling that it so evidently manifested, rather than the direct purport of the words, caused it to vibrate within all hearts, and brought the listeners into one accord of sympathy. Even the poor baby at Hester’s bosom was affected by the same influence, for it directed its hitherto vacant gaze towards Mr. Dimmesdale, and held up its little arms with a half-pleased, half-plaintive murmur... "Woman, transgress not beyond the limits of Heaven’s mercy!’ cried the Reverend Mr. Wilson, more harshly than before. ‘That little babe hath been gifted with a voice, to second and confirm the counsel which thou hast heard. Speak out the name! That, and thy repentance, may avail to take the scarlet letter off thy breast."

The reverends call upon Hester's love for the father of her child—the same love they are condemning—to convince her to reveal his identity. Their attempts to move her by appealing to her sense of duty, compassion and morality are examples of pathos. Once again, this example of pathos reveals a lack of moral fiber in the reverends who are attempting to manipulate Hester by appealing to her emotions, particularly since (spoiler alert!) Reverend Dimmesdale is in fact the father.

Pathos in Dylan Thomas' "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"

In " Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night," Thomas urges his dying father to cling to life and his love of it. The poem is a villanelle , a specific form of verse that originated as a ballad or "country song" and is known for its repetition. Thomas' selection of the repetitive villanelle form contributes to the pathos of his insistent message to his father—his appeal to his father's inner strength:

Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

It's worth noting that, in this poem, pathos is not in any way connected to a lack of morals or inner strength. Quite the opposite, the appeal to emotion is connected to a profound love—the poet's own love for his father.

Pathos in Political Speeches

Politicians understand the power of emotion, and successful politicians are adept at harnessing people's emotions to curry favor for themselves, as well as their policies and ideologies.

Pathos in Barack Obama's 2013 Address to the Nation on Syria

In August 2013, the Syrian government, led by Bashar al-Assad, used chemical weapons against Syrians who opposed his regime, causing several countries—including the United States—to consider military intervention in the conflict. Obama's tragic descriptions of civilians who died as a result of the attack are an example of pathos : they provoke an emotional response and help him mobilize American sentiment in favor of U.S. intervention.

Over the past two years, what began as a series of peaceful protests against the oppressive regime of Bashar al-Assad has turned into a brutal civil war. Over 100,000 people have been killed. Millions have fled the country...The situation profoundly changed, though, on August 21st, when Assad’s government gassed to death over 1,000 people, including hundreds of children. The images from this massacre are sickening: men, women, children lying in rows, killed by poison gas, others foaming at the mouth, gasping for breath, a father clutching his dead children, imploring them to get up and walk.

Pathos in Ronald Reagan's 1987 " Tear Down This Wall!" Speech

In 1987, the Berlin Wall divided Communist East Berlin from Democratic West Berlin. The Wall was a symbol of the divide between the communist Soviet Union, or Eastern Bloc, and the Western Bloc which included the United States, NATO and its allies. The wall also split Berlin in two, obstructing one of Berlin's most famous landmarks: the Brandenburg Gate.

Reagan's speech, delivered to a crowd in front of the Brandenburg Gate, contains many examples of pathos:

Behind me stands a wall that encircles the free sectors of this city, part of a vast system of barriers that divides the entire continent of Europe...Yet it is here in Berlin where the wall emerges most clearly...Every man is a Berliner, forced to look upon a scar... General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Reagan moves his listeners to feel outrage at the Wall's existence by calling it a "scar." He assures Germans that the world is invested in the city's problems by telling the crowd that "Every man is a Berliner." Finally, he excites and invigorates the listener by boldly daring Gorbachev, president of the Soviet Union, to "tear down this wall!"

Pathos in Advertising

Few appreciate the complexity of pathos better than advertisers. Consider all the ads you've seen in the past week. Whether you're thinking of billboards, magazine ads, or TV commercials, its almost a guarantee that the ones you remember contained very little specific information about the product, and were instead designed to create an emotional association with the brand. Advertisers spend incredible amounts of money trying to understand exactly what Aristotle describes as the building blocks of pathos: the emotional "who, what, and why" of their target audience. Take a look at this advertisement for the watch company, Rolex, featuring David Beckham:

Notice that the ad doesn't convey anything specific about the watch itself to make someone think it's a high quality or useful product. Instead, the ad caters to Rolex's target audience of successful male professionals by causing them to associate the Rolex brand with soccer player David Beckham, a celebrity who embodies the values of the advertisement's target audience: physical fitness and attractiveness, style, charisma, and good hair.

Why Do Writers Use Pathos?

The philosopher and psychologist William James once said, “The emotions aren’t always immediately subject to reason, but they are always immediately subject to action.” Pathos is a powerful tool, enabling speakers to galvanize their listeners into action, or persuade them to support a desired cause. Speechwriters, politicians, and advertisers use pathos for precisely this reason: to influence their audience to a desired belief or action.

The use of pathos in literature is often different than in public speeches, since it's less common for authors to try to directly influence their readers in the way politicians might try to influence their audiences. Rather, authors often employ pathos by having a character make use of it in their own speech. In doing so, the author may be giving the reader some insight into a character's values, motives, or their perception of another character.

Consider the above example from The Scarlet Letter. The clergymen in Hester's town punish her by publicly humiliating her in front of the community and holding her up as an example of sin for conceiving a child outside of marriage. The reverends make an effort to get Hester to tell them the name of her child's father by making a dramatic appeal to a sense of shame that Hester plainly does not feel over her sin. As a result, this use of pathos only serves to expose the the manipulative intent of the reverends, offering readers some insight into their moral character as well as that of Puritan society at large. Ultimately, it's a good example of an ineffective use of pathos , since what the reverends lack is the key to eliciting the response they want: a strong grasp of what their listener values.

Other Helpful Pathos Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Pathos: A detailed explanation which covers Aristotle's original ideas on pathos and discusses how the term's meaning has changed over time.

- The Dictionary Definition of Pathos: A definition and etymology of the term, which comes from the Greek pàthos, meaning "suffering or sensation."

- An excellent video from TED-Ed about the three modes of persuasion.

- A pathos -laden recording of Dylan Thomas reading his poem "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"

- Formal Verse

- Common Meter

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Slant Rhyme

- Anachronism

- Polysyndeton

- Static Character

- Anadiplosis

- Antanaclasis

- Blank Verse

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

What Are Logos, Pathos & Ethos?

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

I f you spend any amount of time exploring the wonderful world of philosophy, you’re bound to run into the dynamic trio of rhetorical appeals: logos , ethos and pathos . But, what exactly do they mean and how can you use them in your writing or speaking? In this post, we’ll unpack the rhetorical love triangle in simple terms, using loads of practical examples along the way.

Overview: The Rhetorical Triangle

- What are logos , pathos and ethos ?

- Logos unpacked (+ examples)

- Pathos unpacked (+ examples)

- Ethos unpacked (+ examples)

- The rhetorical triangle

What are logos, ethos and pathos?

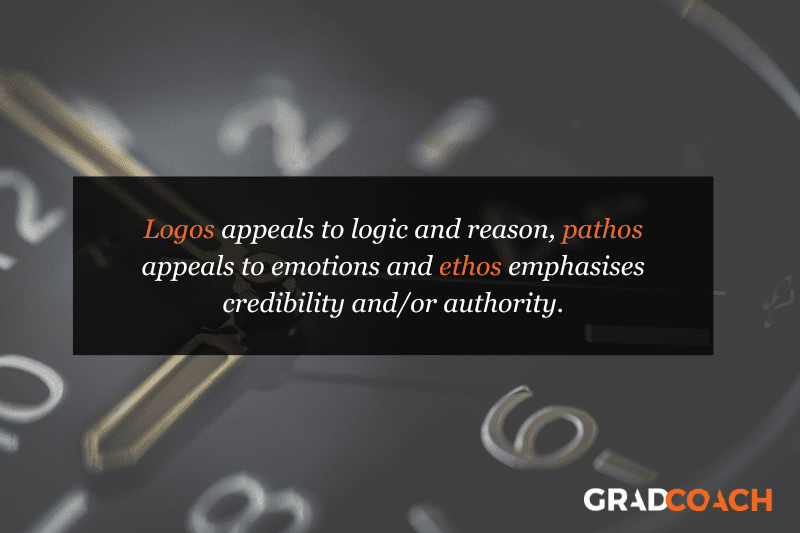

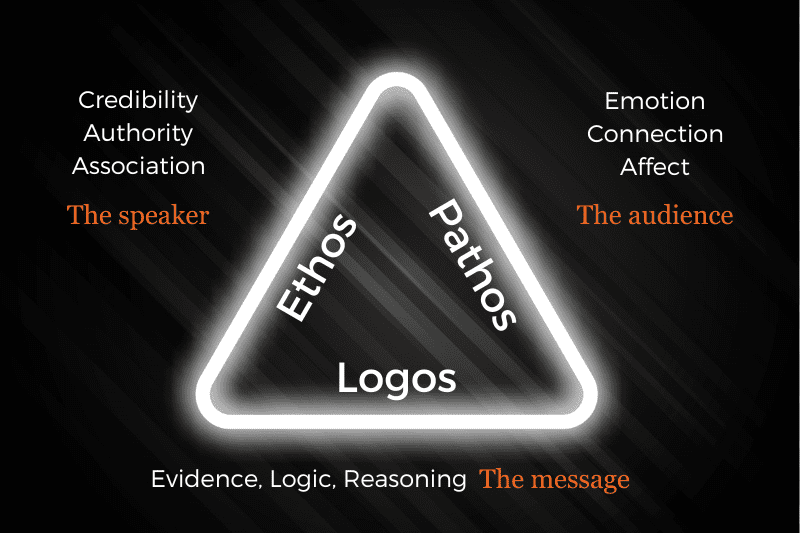

Simply put, logos, ethos and pathos are three powerful tools that you can use to persuade an audience of your argument . At the most basic level, logos appeals to logic and reason, while pathos appeals to emotions and ethos emphasises credibility or authority.

Naturally, a combination of all three rhetorical appeals packs the biggest punch, but it’s important to consider a few different factors to determine the best mix for any given context. Let’s look at each rhetorical appeal in a little more detail to understand how best to use them to your advantage.

Logos appeals to the logical, reason-driven side of our minds. Using logos in an argument typically means presenting a strong body of evidence and facts to support your position. This evidence should then be accompanied by sound logic and well-articulated reasoning .

Let’s look at some examples of logos in action:

- A friend trying to persuade you to eat healthier might present scientific studies that show the benefits of a balanced diet and explain how certain nutrients contribute to overall health and longevity.

- A scientist giving a presentation on climate change might use data from reputable studies, along with well-presented graphs and statistical analyses to demonstrate the rising global temperatures and their impact on the environment.

- An advertisement for a new smartphone might highlight its technological features, such as a faster processor, longer battery life, and a high-resolution camera. This could also be accompanied by technical specifications and comparisons with competitors’ models.

In short, logos is all about using evidence , logic and reason to build a strong argument that will win over an audience on the basis of its objective merit . This contrasts quite sharply against pathos, which we’ll look at next.

Contrasted to logos, pathos appeals to the softer side of us mushy humans. Specifically, it focuses on evoking feelings and emotions in the audience. When utilising pathos in an argument, the aim is to cultivate some feeling of connection in the audience toward either yourself or the point that you’re trying to make.

In practical terms, pathos often uses storytelling , vivid language and personal anecdotes to tap into the audience’s emotions. Unlike logos, the focus here is not on facts and figures, but rather on psychological affect . Simply put, pathos utilises our shared humanness to foster agreement.

Let’s look at some examples of pathos in action:

- An advertisement for a charity might incorporate images of starving children and highlight their desperate living conditions to evoke sympathy, compassion and, ultimately, donations.

- A politician on the campaign trail might appeal to feelings of hope, unity, and patriotism to rally supporters and motivate them to vote for his or her party.

- A fundraising event may include a heartfelt personal story shared by a cancer survivor, with the aim of evoking empathy and encouraging donations to support cancer research.

As you can see, pathos is all about appealing to the human side of us – playing on our emotions to create buy-in and agreement.

Last but not least, we’ve got ethos. Ethos is all about emphasising the credibility and authority of the person making the argument, or leveraging off of someone else’s credibility to support your own argument.

The ethos card can be played by highlighting expertise, achievements, qualifications and accreditations , or even personal and professional associations and connections. Ultimately, the aim here is to foster some level of trust within the audience by demonstrating your competence, as this will make them more likely to take your word as fact.

Let’s look at some examples of ethos in action:

- A fitness equipment brand might hire a well-known athlete to endorse their product.

- A toothpaste brand might make claims highlighting that a large percentage of dentists recommend their product.

- A financial advisor might present their qualifications, certifications and professional memberships when meeting with a prospective client.

As you can see, using ethos in an argument is largely about emphasising the credibility of the person rather than the logical soundness of the argument itself (which would reflect a logos-based approach). This is particularly helpful when there isn’t a large body of evidence to support the argument.

Ethos can also overlap somewhat with pathos in that positive emotions and feelings toward a specific person can oftentimes be extended to someone else’s argument. For example, a brand that has nothing to do with sports could still benefit from the endorsement of a well-loved athlete, just because people feel positive feelings about the athlete – not because of that athlete’s expertise in the product they’re endorsing.

How to use logos, pathos and ethos

Logos, pathos and ethos combine to form the rhetorical triangle , also known as the Aristotelian triangle. As you’d expect, the three sides (or corners) of the triangle reflect the three appeals, but there’s also another layer of meaning. Specifically, the three sides symbolise the relationship between the speaker , the audience and the message .

Without getting too philosophical, the key takeaway here is that logos, pathos and ethos are all tools that you can use to present a persuasive argument . However, how much you use each tool needs to be informed by careful consideration of who your audience is and what message you’re trying to convey to them.

For example, if you’re writing a research paper for a largely scientific audience, you’ll likely lean more heavily on the logos . Conversely, if you’re presenting a speech in which you argue for greater social justice, you may lean more heavily on the pathos to win over the hearts and minds of your audience.

Simply put, by understanding the relationship between yourself (as the person making the argument), your audience , and your message , you can strategically employ the three rhetorical appeals to persuade, engage, and connect with your audience more effectively in any context. Use these tools wisely and you’ll quickly notice what a difference they can make to your ability to communicate and more importantly, to persuade .

You Might Also Like:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Dissertation While Working: A How-To Guide

Struggling to balance your dissertation with a full-time job and family? Learn practical strategies to achieve success.

How To Review & Understand Academic Literature Quickly

Learn how to fast-track your literature review by reading with intention and clarity. Dr E and Amy Murdock explain how.

Dissertation Writing Services: Far Worse Than You Think

Thinking about using a dissertation or thesis writing service? You might want to reconsider that move. Here’s what you need to know.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology Rhetorical Strategies

How to Use Pathos in an Essay: Connecting Emotion and Persuasion

Table of contents, the power of pathos, techniques for utilizing pathos, balance and ethical considerations.

- Aristotle. (n.d.). Rhetoric. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/16357

- Edlund, J. R. (2019). The Ethos-Pathos-Logos of Aristotle's Rhetoric. Humanities Commons. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:24300/

- Perloff, M. (2009). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century. Routledge.

- Johnson, R. H. (2005). Imagining the audience in audience appeals: Audience invoked in American public address textbooks, 1830-1930. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 8(3), 429-453.

- Walton, D. N. (2013). The new dialectic: Conversational contexts of argument. University of Toronto Press.

- Kellner, D. (2009). Critical theory, Marxism, and modernity. In The Routledge companion to social and political philosophy (pp. 381-395). Routledge.

- Gardner, R. C. (2019). Environmental psychology: An introduction. Routledge.

- Pinker, S. (2014). The sense of style: The thinking person's guide to writing in the 21st century. Penguin Books.

- Cialdini, R. B. (2008). Influence: Science and practice (Vol. 4). Pearson Education.

- Sobieraj, S., & Berry, J. M. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19-41.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Violent Media Is Good For Kids

- Discourse Community

- Media Ethics

- Parent-Child Relationship

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

10 Pathos Examples

Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch)

Tio Gabunia is an academic writer and architect based in Tbilisi. He has studied architecture, design, and urban planning at the Georgian Technical University and the University of Lisbon. He has worked in these fields in Georgia, Portugal, and France. Most of Tio’s writings concern philosophy. Other writings include architecture, sociology, urban planning, and economics.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Pathos is a rhetorical device that stirs emotions such as pity, sadness, or sympathy in the audience.

Pathos refers to one corner of the rhetorical triangle, which means that it is one of the three main technical means of persuasion .

Aristotle claims that there are three technical means of persuasion:

“Now the proofs furnished by the speech are of three kinds. The first depends upon the moral character of the speaker, the second upon putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind, the third upon the speech itself, in so far as it proves or seems to prove” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, ca. 367-322 B.C.E./1926, Book 1, Chapter 2, Section 3).

Each of these corresponds to the three means of persuasion:

- Ethos (Appeal to credibility) : Persuasion through establishing the character of the speaker.

- Pathos ( Appeal to emotion ): Persuasion through putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind.

- Logos (Appeal to logic) : Persuasion through proof or seeming proof.

For Aristotle, speech consists of three things: the speaker, the hearer, and the speech. These correspond to ethos, pathos, and logos , respectively. Pathos is the means of persuasion that is concerned with the audience and it is the subject of this article.

Pathos Definition

Pathos refers to appeals to the emotions of the audience. Whenever the audience is led to feel a certain way, and that feeling influences their judgment of a speech, the speaker is using pathos.

Aristotle’s underlying assumption is that people’s emotional states influence their evaluations, which is quite reasonable to suppose.

The rhetorical method, therefore, requires one to sway the emotional states of the hearers:

“… for the judgements we deliver are not the same when we are influenced by joy or sorrow, love or hate” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, ca. 367-322 B.C.E./1926, Book 1, Chapter 2, Section 5).

You can appeal to people’s emotions in many ways: through storytelling hooks, passionate speech, personal anecdotes , and so on.

In some sense, most pieces of writing and most speeches that have an agenda to persuade necessarily have some forms of pathos built into them. For example, even a math textbook may give rise to feelings of awe.

Pathos probably has the worst reputation out of the three technical means of persuasion because people believe that all appeals to emotion are somehow dishonest or manipulative, but this is not so.

There is simply no getting away from elements of pathos, no matter how hard the persuader tries.

Furthermore, the use of pathos to persuade can be just as honest and harmless as the most seemingly objective uses of logos or ethos.

Pathos Examples

Example 1: advertising.

Pathos is an especially common persuasion tool in advertising. Since emotions influence people’s decision-making, pathos is well-suited to the task of persuading customers to buy products (Ho & Siu, 2012).

For example, advertising is to appeal to empathy, which would be part of pathos. Animal welfare organizations like the SPCA, for instance, may appeal to people’s empathy by using pictures of stray dogs accompanied by sad music.

In this context, the power of pathos can be leveraged to not only promote immediate action, such as a donation, but also to build long-term brand associations and loyalty, embedding a sense of empathy and compassion in the perception of the organization’s mission.

Example 2: Art

Most forms of art use pathos in some form. This is more apparent in art that has a clear agenda, for example, political cartoons.

In political cartoons, the application of pathos is often used to generate empathy or outrage, thus persuading viewers to consider the artist’s perspective on social or political issues.

Similarly, in paintings, sculptures, or installation art, artists often use symbolic imagery, dramatic contrasts, and evocative themes to arouse feelings of sorrow, compassion, or introspection .

Example 3: In the ad hominem Argument

Arguments that commit the ad hominem fallacy tend to be persuasive because of pathos.

The ad hominem fallacy involves attacking the arguer’s personal situation or traits (Hansen, 2020). There are three commonly recognized kinds of ad hominem: (1) the abusive ad hominem, (2) the circumstantial ad hominem, and (3) the tu quoque.

The first kind involves arguing that someone’s view should not be accepted because they have some negative property. For example: “Alice’s view that breaking promises is immoral should be rejected because Alice is rude.”

The second kind involves arguing that someone’s view should not be accepted because their view is supported by self-interest. For example: “Bob’s recommendation to exercise regularly should be rejected because Bob owns a gym.”

The tu quoque involves arguing that someone’s view should not be accepted because their actions are inconsistent with that view. For example: “Clarence’s view that people should not drive cars should not be accepted because Clarence drives a car.”

Example 4: In the Slippery Slope Argument

Another form of persuasive but fallacious argument is the slippery slope. It is a fallacy that occurs when one unjustifiably assumes that a small step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant effect.

Such arguments may sometimes be reasonable, but they are not deductively correct.

Moreover, they usually rely on generating fear on the part of the audience. Alfred Sidgwick described slippery slope arguments in the following way:

“We must not do this or that, it is often said, because if we did we should be logically bound to do something else which is plainly absurd or wrong. If we once begin to take a certain course there is no knowing where we shall be able to stop within any show of consistency; there would be no reason for stopping anywhere in particular, and we should be led on, step by step into action or opinions that we all agree to call undesirable or untrue.” (Sidgwick, 1910, p. 40)

Example 5: In Music

The use of emotional music in a piece of media the purpose of which is to persuade is an example of pathos.

Such music can intensify the emotional impact of, for example, an advertisement and thereby make it more persuasive.

Since logic is rarely used to advertise products, pathos is often the most important means of persuasion in such cases.

Example 6: In Political Rhetoric

Word choice in political speech is particularly important for the effective use of pathos.

For example, the conflicting uses of terms like “unborn life” and ”fetus” in women’s reproductive rights debates appeal to people’s emotions in different ways.

Whereas one side would appeal to the emotion of saving life, the other would appeal to the emotion of freedom and bodily autonomy.

It is virtually impossible for an effective political speech not to contain pathos, especially in democratic contexts. How skillfully a politician appeals to the emotions of the voters will, to a large extent, determine the success of their campaign.

Example 7: In Social Media Campaigns

Pathos is frequently utilized in social media campaigns, often leveraging user-generated content to create a sense of empathy or community around a product or cause.

User stories that feature personal triumphs, challenges overcome, or emotional experiences related to the product or cause in question are designed to invoke emotional responses that foster brand loyalty or advocacy.

The use of pathos in social media campaigns often involves images, videos, and narratives that are likely to resonate emotionally with the target audience, effectively fostering a deeper connection to the brand or cause, and enhancing audience engagement and interaction.

Example 8: In Public Health Campaigns

Pathos is also evident in public health campaigns. For instance, anti-drinking ads often show the severe health effects of drinking, such as patients unable to play with their children due to health issues.

These campaigns are intended to evoke fear or concern, stimulating the public to change their behavior and adopt healthier habits.

By emphasizing the grave consequences and personal costs of unhealthy choices, public health campaigns that use pathos aim to foster a more emotional and personal connection to health issues, making the audience more likely to take preventive actions or change unhealthy habits.

Example 9: In Philanthropy and Fundraising

Pathos is used extensively in philanthropy and fundraising, with organizations sharing stories of individuals or communities in need to evoke empathy and provoke action.

Charitable campaigns that depict the harsh realities of poverty, disease, or disaster aim to stir feelings of compassion, guilt, or responsibility, encouraging donations and aid.

Through the strategic use of pathos, philanthropy and fundraising campaigns can make the plight of those in need feel more immediate and tangible, thereby increasing the likelihood of donations and encouraging more active involvement in the cause or issue at hand.

Example 10: In Literature

In literature, authors often use pathos to create an emotional connection between readers and characters or situations.

This might involve crafting narratives around heart-wrenching tragedies, touching moments, or stirring triumphs to make the readers feel a range of emotions, thereby enhancing their engagement and investment in the storyline.

By evoking deep emotional responses through the use of pathos, authors can make the characters and situations in their works more relatable and real, intensifying readers’ engagement and creating a lasting impact that goes beyond mere enjoyment of the story.

Strengths of Pathos

- Memorability: Appeals to emotion tend to stick. While you’re unlikely to remember the speaker’s logical reasoning or their credentials perfectly, you probably will remember how the speech made you feel.

- Decision-making : appeals to pathos typically affect the actions of the audience more than appeals to ethos or logos.

- Subjective topics: similar to ethos, pathos is an especially powerful persuasion technique in matters that don’t rely on objective criteria. In such a case, logical arguments alone won’t be enough. For example, the orator will make greater use of pathos when speaking about a work of art than when debating the merits of a mathematical proof.

Weaknesses of Pathos

- Manipulation: The use of pathos can be morally questionable since it can exploit people’s emotional vulnerabilities.

- Insincerity: It is easy for the audience to perceive the speaker’s appeals to pathos as insincere. Some people view all appeals to emotion as attempts to mask or modify the truth, so the orator must know their audience before resorting to pathos.

The term pathos comes from the Greek word for “experience” or “suffering.” In the context of rhetoric, it refers to appeals to the emotions of the audience.

See Also: The 5 Types of Rhetorical Situations

Aristotle. (1926). Rhetoric. In Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 22, translated by J. H. Freese. Harvard University Press. (Original work published ca. 367-322 B.C.E.)

Hansen, H. (2020). Fallacies. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/fallacies/

Ho, A. G., & Siu, K. W. M. G. (2012). Emotion Design, Emotional Design, Emotionalize Design: A Review on Their Relationships from a New Perspective. The Design Journal, 15(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630612X13192035508462

Rapp, C. (2022). Aristotle’s Rhetoric. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/

Sidgwick, A. (1910). The application of logic. London : Macmillan and Co., limited. http://archive.org/details/applicationoflog00sidgiala

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 6 Types of Societies (With 21 Examples)

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Public Health Policy Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Cultural Differences Examples

- Tio Gabunia (B.Arch, M.Arch) #molongui-disabled-link Social Interaction Types & Examples (Sociology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Using Rhetorical Strategies for Persuasion

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

There are three types of rhetorical appeals, or persuasive strategies, used in arguments to support claims and respond to opposing arguments. A good argument will generally use a combination of all three appeals to make its case.

Logos or the appeal to reason relies on logic or reason. Logos often depends on the use of inductive or deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning takes a specific representative case or facts and then draws generalizations or conclusions from them. Inductive reasoning must be based on a sufficient amount of reliable evidence. In other words, the facts you draw on must fairly represent the larger situation or population. Example:

In this example the specific case of fair trade agreements with coffee producers is being used as the starting point for the claim. Because these agreements have worked the author concludes that it could work for other farmers as well.

Deductive reasoning begins with a generalization and then applies it to a specific case. The generalization you start with must have been based on a sufficient amount of reliable evidence.Example:

In this example the author starts with a large claim, that genetically modified seeds have been problematic everywhere, and from this draws the more localized or specific conclusion that Mexico will be affected in the same way.

Avoid Logical Fallacies

These are some common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Also, watch out for these slips in other people's arguments.

Slippery slope: This is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur A must not be allowed to occur either. Example:

In this example the author is equating banning Hummers with banning all cars, which is not the same thing.

Hasty Generalization: This is a conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. In other words, you are rushing to a conclusion before you have all the relevant facts. Example:

In this example the author is basing their evaluation of the entire course on only one class, and on the first day which is notoriously boring and full of housekeeping tasks for most courses. To make a fair and reasonable evaluation the author must attend several classes, and possibly even examine the textbook, talk to the professor, or talk to others who have previously finished the course in order to have sufficient evidence to base a conclusion on.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc: This is a conclusion that assumes that if 'A' occurred after 'B' then 'B' must have caused 'A.' Example:

In this example the author assumes that if one event chronologically follows another the first event must have caused the second. But the illness could have been caused by the burrito the night before, a flu bug that had been working on the body for days, or a chemical spill across campus. There is no reason, without more evidence, to assume the water caused the person to be sick.

Genetic Fallacy: A conclusion is based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth. Example:

In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the character of the people who built the car.

Begging the Claim: The conclusion that the writer should prove is validated within the claim. Example:

Arguing that coal pollutes the earth and thus should be banned would be logical. But the very conclusion that should be proved, that coal causes enough pollution to warrant banning its use, is already assumed in the claim by referring to it as "filthy and polluting."

Circular Argument: This restates the argument rather than actually proving it. Example:

In this example the conclusion that Bush is a "good communicator" and the evidence used to prove it "he speaks effectively" are basically the same idea. Specific evidence such as using everyday language, breaking down complex problems, or illustrating his points with humorous stories would be needed to prove either half of the sentence.

Either/or: This is a conclusion that oversimplifies the argument by reducing it to only two sides or choices. Example:

In this example where two choices are presented as the only options, yet the author ignores a range of choices in between such as developing cleaner technology, car sharing systems for necessities and emergencies, or better community planning to discourage daily driving.

Ad hominem: This is an attack on the character of a person rather than their opinions or arguments. Example:

In this example the author doesn't even name particular strategies Green Peace has suggested, much less evaluate those strategies on their merits. Instead, the author attacks the characters of the individuals in the group.

Ad populum: This is an emotional appeal that speaks to positive (such as patriotism, religion, democracy) or negative (such as terrorism or fascism) concepts rather than the real issue at hand. Example:

In this example the author equates being a "true American," a concept that people want to be associated with, particularly in a time of war, with allowing people to buy any vehicle they want even though there is no inherent connection between the two.

Red Herring: This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Example:

In this example the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other, it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals.

Ethos or the ethical appeal is based on the character, credibility, or reliability of the writer. There are many ways to establish good character and credibility as an author:

- Use only credible, reliable sources to build your argument and cite those sources properly.

- Respect the reader by stating the opposing position accurately.

- Establish common ground with your audience. Most of the time, this can be done by acknowledging values and beliefs shared by those on both sides of the argument.

- If appropriate for the assignment, disclose why you are interested in this topic or what personal experiences you have had with the topic.

- Organize your argument in a logical, easy to follow manner. You can use the Toulmin method of logic or a simple pattern such as chronological order, most general to most detailed example, earliest to most recent example, etc.

- Proofread the argument. Too many careless grammar mistakes cast doubt on your character as a writer.

Pathos , or emotional appeal, appeals to an audience's needs, values, and emotional sensibilities. Pathos can also be understood as an appeal to audience's disposition to a topic, evidence, or argument (especially appropriate to academic discourse).

Argument emphasizes reason, but used properly there is often a place for emotion as well. Emotional appeals can use sources such as interviews and individual stories to paint a more legitimate and moving picture of reality or illuminate the truth. For example, telling the story of a single child who has been abused may make for a more persuasive argument than simply the number of children abused each year because it would give a human face to the numbers. Academic arguments in particular benefit from understanding pathos as appealing to an audience's academic disposition.

Only use an emotional appeal if it truly supports the claim you are making, not as a way to distract from the real issues of debate. An argument should never use emotion to misrepresent the topic or frighten people.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos Defined

By melanie gagich and emilie zickel.

Rhetoric is the way that authors use and manipulate language in order to persuade an audience. Once we understand the rhetorical situation out of which a text is created (why it was written, for whom it was written, by whom it was written, how the medium in which it was written creates certain constraints or perhaps freedoms of expression), we can look at how all of those contextual elements shape the author’s creation of the text .

We can look first at the classical rhetorical appeals, which are the three ways to classify authors’ intellectual, moral, and emotional approaches to getting the audience to have the reaction that the author hopes for.

Rhetorical Appeals

Rhetorical appeals refer to ethos, pathos, and logos. These are classical Greek terms, dating back to Aristotle, who is traditionally seen as the father of rhetoric. To be rhetorically effective (and thus persuasive), an author must engage the audience in a variety of compelling ways, which involves carefully choosing how to craft their argument so that the outcome, audience agreement with the argument or point, is achieved. Aristotle defined these modes of engagement and gave them the terms that we still use today: logos, pathos, and ethos.

Logos: Appeal to Logic

Logic. Reason. Rationality. Logos is brainy and intellectual, cool, calm, collected, objective .

When an author relies on logos, it means that they are using logic, careful structure, and objective evidence to appeal to the audience. An author can appeal to an audience’s intellect by using information that can be fact checked (using multiple sources ) and thorough explanations to support key points. Additionally, providing a solid and non-biased explanation of one’s argument is a great way for an author to invoke logos.

For example, if I were trying to convince my students to complete their homework, I might explain that I understand everyone is busy and they have other classes (non-biased), but the homework will help them get a better grade on their test (explanation). I could add to this explanation by providing statistics showing the number of students who failed and didn’t complete their homework versus the number of students who passed and did complete their homework (factual evidence).

Logical appeals rest on rational modes of thinking , such as

- Comparison – including a comparison between one thing (with regard to your topic ) and another similar thing to help support your claim . It is important that the comparison is fair and valid–the things being compared must share significant traits of similarity.

- Cause/effect thinking – arguing that X has caused Y, or that X is likely to cause Y to help support your claim . Be careful with the latter–it can be difficult to predict that something will happen in the future.

- Deductive reasoning – starting with a broad, general claim /example and using it to support a more specific point or claim

- Inductive reasoning – using several specific examples or cases to make a broad generalization

- Exemplification – using many examples or a variety of evidence to support a single point

- Elaboration – moving beyond just including a fact but explaining the significance or relevance of that fact

- Coherent thought – maintaining a well-organized line of reasoning; not repeating ideas or jumping around

Pathos: Appeal to Emotions

When an author relies on pathos, it means that they are trying to tap into the audience’s emotions to get them to agree with the author’s claim . An author using pathetic appeals wants the audience to feel something: anger, pride, joy, rage, or happiness. For example, many of us have seen the ASPCA commercials that use photographs of injured puppies or sad-looking kittens and slow, depressing music to emotionally persuade their audience to donate money.

Pathos-based rhetorical strategies are any strategies that get the audience to “open up” to the topic , the argument, or the author. Emotions can make us vulnerable, and an author can use this vulnerability to get the audience to believe that their argument is a compelling one.

Pathetic appeals might include

- Expressive descriptions of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel or experience those events

- Vivid imagery of people, places, or events that help the reader to feel like they are seeing those events

- Personal stories that make the reader feel a connection to, or empathy for, the person being described

- Emotion-laden vocabulary as a way to put the reader into that specific emotional mindset (What is the author trying to make the audience feel? And how are they doing that?)

- Information that will evoke an emotional response from the audience . This could involve making the audience feel empathy or disgust for the person/group/event being discussed or perhaps connection to or rejection of the person/group/event being discussed.

When reading a text , try to locate when the author is trying to convince the reader using emotions because, if used to excess, pathetic appeals can indicate a lack of substance or emotional manipulation of the audience. See the links below about fallacious pathos for more information.

Ethos: Appeal to Values/Trust

Ethical appeals have two facets: audience values and authorial credibility/character.

On the one hand, when an author makes an ethical appeal, they are attempting to tap into the values or ideologies that the audience holds , for example, patriotism, tradition, justice, equality, dignity for all humankind, self-preservation, or other specific social, religious or philosophical values (Christian values, socialism, capitalism, feminism, etc.). These values can sometimes feel very close to emotions, but they are felt on a social level rather than only on a personal level. When an author evokes the values that the audience cares about to justify or support their argument, we classify that as ethos. The audience will feel that the author is making an argument that is “right” (in the sense of moral “right”-ness, i.e., “My argument rests upon the values that matter to you. Therefore, you should accept my argument”). This first part of the definition of ethos, then, is focused on the audience’s values.

On the other hand, this sense of referencing what is “right” in an ethical appeal connects to the other sense of ethos: the author. Ethos that is centered on the author revolves around two concepts: the credibility of the author and their character.

- Credibility of the speaker/author is determined by their knowledge and expertise in the subject at hand. For example, if you are learning about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, would you rather learn from a professor of physics or a cousin who took two science classes in high school 30 years ago? It is fair to say that, in general, the professor of physics would have more credibility to discuss the topic of physics. To establish their credibility, an author may draw attention to who they are or what kinds of experience they have with the topic being discussed as an ethical appeal (i.e., “Because I have experience with this topic –and I know my stuff– you should trust what I am saying about this topic ”). Some authors do not have to establish their credibility because the audience already knows who they are and that they are credible.

- Character is another aspect of ethos. Character is different from credibility because it involves personal history and even personality traits. A person can be credible but lack character or vice versa. For example, in politics, sometimes the most experienced candidates–those who might be the most credible candidates–fail to win elections because voters do not accept their character. Politicians take pains to shape their character as leaders who have the interests of the voters at heart. The candidate who successfully proves to the voters (the audience) that they have the type of character that the audience can trust is more likely to win.

Thus, ethos comes down to trust. How can the author gain the audience’s trust so that the audience will accept their argument? How can the author make him or herself appear as a credible speaker who embodies the character traits that the audience values? In building ethical appeals, we see authors referring either directly or indirectly to the values that matter to the intended audience (so that the audience will trust the speaker). Authors use language, phrasing, imagery, or other writing styles common to people who hold those values, thereby “talking the talk” of people with those values (again, so that the audience is inclined to trust the speaker). Authors refer to their experience and/or authority with the topic as well (and therefore demonstrate their credibility).

When reading, you should think about the author’s credibility regarding the subject as well as their character. Here is an example of a rhetorical move that connects with ethos: when reading an article about abortion, the author mentions that she has had an abortion. That is an example of an ethical move because the author is creating credibility via anecdotal evidence and first-person narrative. In a rhetorical analysis project, it would be up to you, the analyzer, to point out this move and associate it with a rhetorical strategy.

Rhetorical Appeals Misuse

When writers misuse logos, pathos, or ethos, arguments can be weakened. Above, we defined and described what logos, pathos, and ethos are and why authors may use those strategies. Sometimes, using a combination of logical, pathetic, and ethical appeals leads to a sound, balanced, and persuasive argument. It is important to understand, though, that using rhetorical appeals does not always lead to a sound, balanced argument. In fact, any of the appeals could be misused or overused. And when that happens, arguments can be weakened.

To see what a misuse of logical appeals might consist of, see Logical Fallacies.

To see how authors can overuse emotional appeals and turn-off their target audience, visit the following link from WritingCommons.org : Fallacious Pathos .

To see how ethos can be misused or used in a manner that may be misleading, visit the following link to WritingCommons.org : Fallacious Ethos

Attributions

“Rhetorical Appeals: Logos, Pathos, and Ethos Defined” by Melanie Gagich, Emilie Zickel is licensed under CC BY-NC SA 4.0

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Encyclopedia for Writers

Writing with ai, using pathos in persuasive writing.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College

Incorporating appeals to pathos into persuasive writing increases a writer’s chances of achieving his or her purpose. Read “ Pathos ” to define and understand pathos and methods for appealing to it. The following brief article discusses examples of these appeals in persuasive writing.

An important key to incorporating pathos into your persuasive writing effectively is appealing to your audience’s commonly held emotions. To do this, one must be able to identify common emotions, as well as understand what situations typically evoke such emotions. The blog post “ The 10 Most Common Feelings Worldwide, We Feel Fine ,” offers an interview with Seth Kamvar, co-author of We Feel Fine. According to the post, the 10 most commonly held emotions in 2006-2009 were: better, bad, good, guilty, sorry, sick, well, comfortable, great, and happy (qtd. in Whelan).

Let’s take a look at some potential essay topics, what emotions they might evoke, and what methods can be used to appeal to those emotions.

Table of Contents

Example: Animal Cruelty

Related Emotions:

Method Narrative

In “To Kill a Chicken,” Nicholas Kristof describes footage taken by an undercover investigator for Mercy with Animals at a North Carolina poultry slaughterhouse: “some chickens aren’t completely knocked out by the electric current and can be seen struggling frantically. Others avoid the circular saw somehow. A backup worker is supposed to cut the throat of those missed by the saw, but any that get by him are scalded alive, the investigator said” (Kristof).

This narrative account, which creates a cruel picture in readers’ minds, will evoke anger, horror, sadness, and sympathy.

Example: Human Trafficking

- Sadness (sorry)

- Sympathy

Method: Direct Quote

“From Victim to Impassioned Voice” provides the perspective of Asia Graves, a victim of a vicious child prostitution ring who attributes her survival to a group of women: “If I didn’t have those strong women, I’d be nowhere” (McKin).

A quote from a victim of human trafficking humanizes the topic, eliciting sadness and sympathy for the victim(s).

Example: Cyberbullying

Method: empathy for an opposing view.

The concerns of some people who oppose the criminalization of cyberbullying are understandable. For example, Justin W. Patchin, coauthor of Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying , opposes making cyberbullying a crime because he views the federal and state governments’ role as one to educate local school districts and provide resources for them (“Cyberbullying”). Patchin does not oppose cyberbullying itself; rather, he takes issue with the government responding to it through criminalization.

Identifying and articulating the opposing view as well as the concerns that underpin it helps the audience experience a full range of sympathy, a commonly held emotion, as a consequence of sincerely investigating and acknowledging another view.

The method a writer uses to persuade emotionally his or her audience will depend on the situation. However, any writer who uses at least one approach will be more persuasive than a writer who ignores opportunities to entreat one of the most powerful aspects of the human experience—emotions.

Works Cited

“Cyberbullying.” Opposing Viewpoints Online Collection . Detroit: Gale, 2015. Opposing Viewpoints in Context . Web. 21 July 2016.

Kristof, Nicholas. “To Kill a Chicken.” The New York Times . The New York Times, 3 May 2015. Web. 20 July 2016.

McKin, Jenifer. “From victim to impassioned voice: Women exploited as a teen fights sexual trafficking of children.” The Boston Globe . Boston Globe Media Partners, 27 Nov. 2012. Web. 20 July 2016.

Whelan, Christine. “The 10 Most Common Feelings Worldwide: We Feel Fine.” The Huffington Post . The Huffington Post, 18 March 2012. Web. 21 July 2016.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing