- College Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Expository Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Scholarship Essay

- Admission Essay

- Reflective Essay

- Nursing Essay

- Economics Essay

Assignments

- Term Papers

- Research Papers

- Case Studies

- Dissertation

- Presentation

- Editing Help

- Cheap Essay Writing

- How to Order

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

14 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

A Catalogue of 300 Best Persuasive Essay Topics for Students

Persuasive Essay Outline - A Complete Guide

30+ Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

How To Write A Persuasive Essay On Abortion

Learn to Write a Persuasive Essay About Business With 5 Best Examples

Check Out 14 Persuasive Essays About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences , evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19

When writing a persuasive essay about the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Here is another example explaining How COVID-19 has changed our lives essay:

Let’s look at another sample essay:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of COVID-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the COVID-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About COVID-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get an idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

- Choose a Specific Angle: Narrow your focus to a specific aspect of COVID-19, like vaccination or public health measures.

- Provide Credible Sources: Support your arguments with reliable sources like scientific studies and government reports.

- Use Persuasive Language: Employ ethos, pathos, and logos , and use vivid examples to make your points relatable.

- Organize Your Essay: Create a solid persuasive essay outline and ensure a logical flow, with each paragraph focusing on a single point.

- Emphasize Benefits: Highlight how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being.

- Use Visuals: Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics to reinforce your arguments.

- Call to Action: End your essay conclusion with a strong call to action, encouraging readers to take a specific step.

- Revise and Edit: Proofread for grammar, spelling, and clarity, ensuring smooth writing flow.

- Seek Feedback: Have someone else review your essay for valuable insights and improvements.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems

- Global Cooperation vs. Vaccine Nationalism in Fighting the Pandemic

- The Future of Telemedicine: Expanding Healthcare Access Post-COVID-19

In search of more inspiring topics for your next persuasive essay? Our persuasive essay topics blog has plenty of ideas!

To sum it up,

You’ve explored great sample essays and picked up some useful tips. You now have the tools you need to write a persuasive essay about Covid-19. So don’t let doubts hold you back—start writing!

If you’re feeling stuck or need a bit of extra help, don’t worry! MyPerfectWords.com offers a professional persuasive essay writing service that can assist you. Our experienced essay writers are ready to help you craft a well-structured, insightful paper on Covid-19.

Just place your “ do my essay for me ” request today, and let us take care of the rest!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good title for a covid-19 essay.

A good title for a COVID-19 essay should be clear, engaging, and reflective of the essay's content. Examples include:

- "The Impact of COVID-19 on Global Health"

- "How COVID-19 Has Transformed Our Daily Lives"

- "COVID-19: Lessons Learned and Future Implications"

How do I write an informative essay about COVID-19?

To write an informative essay about COVID-19, follow these steps:

- Choose a specific focus: Select a particular aspect of COVID-19, such as its transmission, symptoms, or vaccines.

- Research thoroughly: Gather information from credible sources like scientific journals and official health organizations.

- Organize your content: Structure your essay with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Present facts clearly: Use clear, concise language to convey information accurately.

- Include visuals: Use charts or graphs to illustrate data and make your essay more engaging.

How do I write an expository essay about COVID-19?

To write an expository essay about COVID-19, follow these steps:

- Select a clear topic: Focus on a specific question or issue related to COVID-19.

- Conduct thorough research: Use reliable sources to gather information.

- Create an outline: Organize your essay with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Explain the topic: Use facts and examples to explain the chosen aspect of COVID-19 in detail.

- Maintain objectivity: Present information in a neutral and unbiased manner.

- Edit and revise: Proofread your essay for clarity, coherence, and accuracy.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Struggling With Your Paper?

Get a custom paper written at

With a FREE Turnitin report, and a 100% money-back guarantee

LIMITED TIME ONLY!

Keep reading

OFFER EXPIRES SOON!

Persuasive Essay Writing

Persuasive Essay About Covid 19

Top Examples of Persuasive Essay about Covid-19

Published on: Jan 10, 2023

Last updated on: Oct 18, 2024

People also read

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: A Step-by-Step Guide

Easy and Unique Persuasive Essay Topics with Tips

The Basics of Crafting an Outstanding Persuasive Essay Outline

Ace Your Next Essay With These Persuasive Essay Examples!

Persuasive Essay About Gun Control - Best Examples for Students

Learn How To Write An Impressive Persuasive Essay About Business

Learn How to Craft a Compelling Persuasive Essay About Abortion With Examples!

Make Your Point: Tips and Examples for Writing a Persuasive Essay About Online Education

Learn How To Craft a Powerful Persuasive Essay About Bullying

Craft an Engaging Persuasive Essay About Smoking: Examples & Tips

Learn How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Social Media With Examples

Craft an Effective Argument: Examples of Persuasive Essay About Death Penalty

Share this article

In these recent years, covid-19 has emerged as a major global challenge. It has caused immense global economic, social, and health problems.

Writing a persuasive essay on COVID-19 can be tricky with all the information and misinformation.

But don't worry! We have compiled a list of persuasive essay examples during this pandemic to help you get started.

Here are some examples and tips to help you create an effective persuasive essay about this pandemic.

On This Page On This Page -->

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

The coronavirus pandemic has everyone on edge. You can expect your teachers to give you an essay about covid-19. You might be overwhelmed about what to write in an essay.

Worry no more!

Here are a few examples to help get you started.

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

Check out some more persuasive essay examples to get more inspiration and guidance.

Examples of Persuasive Essay About the Covid-19 Vaccine

With so much uncertainty surrounding the Covid-19 vaccine, it can be challenging for students to write a persuasive essay about getting vaccinated.

Here are a few examples of persuasive essays about vaccination against covid-19.

Check these out to learn more.

Persuasive essay on the covid-19 vaccine

Tough Essay Due? Hire a Writer!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

Writing a persuasive essay on Covid-19 integration doesn't have to be stressful or overwhelming.

With the right approach and preparation, you can write an essay that will get them top marks!

Here are a few samples of compelling persuasive essays. Give them a look and get inspiration for your next essay.

Integration of Covid-19 Persuasive essay

Integration of Covid-19 Persuasive essay sample

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid-19

Writing an argumentative essay can be a daunting task, especially when the topic is as broad as the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Read the following examples of how to make a compelling argument on covid-19.

Argumentative essay on Covid-19

Argumentative Essay On Covid-19

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive speech about anything can seem daunting. However, writing a persuasive speech about something as important as the Covid-19 pandemic doesnât have to be difficult.

So let's explore some examples of perfectly written persuasive essays.

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay

Here are seven tips that can help you create a strong argument on the topic of covid-19.

Check out this informative video to learn more about effective tips and tricks for writing persuasive essays.

1. Start with an attention-grabbing hook:

Use a quote, statistic, or interesting fact related to your argument at the beginning of your essay to draw the reader in.

2. Make sure you have a clear thesis statement:

A thesis statement is one sentence that expresses the main idea of your essay. It should clearly state your stance on the topic and provide a strong foundation for the rest of your content.

3. Support each point with evidence:

To make an effective argument, you must back up each point with credible evidence from reputable sources. This will help build credibility and validate your claims throughout your paper.

4. Use emotional language and tone:

Emotional appeals are powerful tools to help make your argument more convincing. Use appropriate language for the audience and evokes emotion to draw them in and get them on board with your claims.

5. Anticipate counterarguments:

Use proper counterarguments to effectively address all point of views.

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and address them directly by providing evidence or reasoning why they are wrong.

6. Stay focused:

Keep your main idea in mind throughout the essay, making sure all of your arguments support it. Donât stray off-topic or introduce unnecessary information that will distract from the purpose of your paper.

7. Conclude strongly:

Make sure you end on a strong note. Reemphasize your main points, restate your thesis statement, and challenge the reader to respond or take action in some way. This will leave a lasting impression in their minds and make them more likely to agree with you.

Writing an effective persuasive essay is a piece of cake with our guide and examples. Check them out to learn more!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

We hope that you have found the inspiration to write your next persuasive essay about covid-19.

However, If you're overwhelmed by the task, don't worry - our professional essay writing service is here to help.

Our expert and experienced persuasive essay writer can help you write a persuasive essay on covid-19 that gets your readers' attention.

Our professional essay writer can provide you with all the resources and support you need to craft a well-written, well-researched essay. Our essay writing service offers top-notch quality and guaranteed results.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you begin a persuasive essay.

To begin a persuasive essay, you must choose a topic you feel strongly about and formulate an argument or position. Start by researching your topic thoroughly and then formulating your thesis statement.

What are good topics for persuasive essays?

Good topics for persuasive essays include healthcare reform, gender issues, racial inequalities, animal rights, environmental protection, and political change. Other popular topics are social media addiction, internet censorship, gun control legislation, and education reform.

What impact does COVID-19 have on society?

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on society worldwide. It has changed the way we interact with one another. The pandemic has also caused economic disruption, forcing many businesses to close or downsize their operations.

Cathy A. (Literature, Education)

For more than five years now, Cathy has been one of our most hardworking authors on the platform. With a Masters degree in mass communication, she knows the ins and outs of professional writing. Clients often leave her glowing reviews for being an amazing writer who takes her work very seriously.

Need Help With Your Essay?

Also get FREE title page, Turnitin report, unlimited revisions, and more!

Keep reading

OFF ON CUSTOM ESSAYS

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Morning Newsletter

Vaccine Persuasion

Many vaccine skeptics have changed their minds.

By David Leonhardt

When the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a poll at the start of the year and asked American adults whether they planned to get vaccinated, 23 percent said no.

But a significant portion of that group — about one quarter of it — has since decided to receive a shot. The Kaiser pollsters recently followed up and asked these converts what led them to change their minds . The answers are important, because they offer insight into how the millions of still unvaccinated Americans might be persuaded to get shots, too.

First, a little background: A few weeks ago, it seemed plausible that Covid-19 might be in permanent retreat, at least in communities with high vaccination rates. But the Delta variant has changed the situation. The number of cases is rising in all 50 states .

Although vaccinated people remain almost guaranteed to avoid serious symptoms, Delta has put the unvaccinated at greater risk of contracting the virus — and, by extension, of hospitalization and death. The Covid death rate in recent days has been significantly higher in states with low vaccination rates than in those with higher rates:

(For more detailed state-level charts, see this piece by my colleagues Lauren Leatherby and Amy Schoenfeld Walker. The same pattern is evident at the county level, as the health policy expert Charles Gaba has been explaining on Twitter.)

Nationwide, more than 99 percent of recent deaths have occurred among unvaccinated people, and more than 97 percent of recent hospitalizations have occurred among the unvaccinated, according to the C.D.C. “Look,” President Biden said on Friday, “the only pandemic we have is among the unvaccinated.”

The three themes

What helps move people from vaccine skeptical to vaccinated? The Kaiser polls point to three main themes.

(The themes apply to both the 23 percent of people who said they would not get a shot, as well as to the 28 percent who described their attitude in January as “wait and see.” About half of the “wait and see” group has since gotten a shot.)

1. Seeing that millions of other Americans have been safely vaccinated.

Consider these quotes from Kaiser’s interviews :

“It was clearly safe. No one was dying.” — a 32-year-old white Republican man in South Carolina “I went to visit my family members in another state and everyone there had been vaccinated with no problems.” — a 63-year-old Black independent man in Texas “Almost all of my friends were vaccinated with no side effects.” — a 64-year-old Black Democratic woman in Tennessee

This suggests that emphasizing the safety of the vaccines — rather than just the danger of Covid, as many experts (and this newsletter) typically do — may help persuade more people to get a shot.

A poll of vaccine skeptics by Echelon Insights, a Republican firm, points to a similar conclusion. One of the most persuasive messages, the skeptics said, was hearing that people have been getting the vaccine for months and it is “working very well without any major issues.”

2. Hearing pro-vaccine messages from doctors, friends and relatives.

For many people who got vaccinated, messages from politicians, national experts and the mass media were persuasive. But many other Americans — especially those without a college degree — don’t trust mainstream institutions. For them, hearing directly from people they know can have a bigger impact.

“Hearing from experts,” as Mollyann Brodie, who oversees the Kaiser polls, told me, “isn’t the same as watching those around you or in your house actually go through the vaccination process.”

Here are more Kaiser interviews:

“My daughter is a doctor and she got vaccinated, which was reassuring that it was OK to get vaccinated.” — a 64-year-old Asian Democratic woman in Texas “Friends and family talked me into it, as did my place of employment.” — a 28-year-old white independent man in Virginia “My husband bugged me to get it and I gave in.” — a 42-year-old white Republican woman in Indiana “I was told by my doctor that she strongly recommend I get the vaccine because I have diabetes.” — a 47-year-old white Republican woman in Florida

These comments suggest that continued grass-roots campaigns may have a bigger effect at this stage than public-service ad campaigns. The one exception to that may be prominent figures from groups that still have higher vaccine skepticism, like Republican politicians and Black community leaders.

3. Learning that not being vaccinated will prevent people from doing some things.

There is now a roiling debate over vaccine mandates , with some hospitals, colleges, cruise-ship companies and others implementing them — and some state legislators trying to ban mandates. The Kaiser poll suggests that these requirements can influence a meaningful number of skeptics to get shots, sometimes just for logistical reasons.

“Hearing that the travel quarantine restrictions would be lifted for those people that are vaccinated was a major reason for my change of thought.” — a 43-year-old Black Democratic man in Virginia “To see events or visit some restaurants, it was easier to be vaccinated.” — a 39-year-old white independent man in New Jersey “Bahamas trip required a COVID shot.” — a 43-year-old Hispanic independent man in Pennsylvania

More on the virus:

Indonesia is the pandemic’s new epicenter , with the highest count of new infections.

After Los Angeles County reinstated indoor mask requirements, the sheriff said the rules were “not backed by science” and refused to enforce them.

The American tennis star Coco Gauff tested positive and will not participate in the Tokyo Olympics.

THE LATEST NEWS

Remote voting in Congress has become a personal and political convenience for House members of both parties.

The Times’s Mark Leibovich profiled Ron Klain , Biden’s chief of staff, whom some Republicans call “Prime Minister Klain.”

Flooding in Western Europe killed at least 183 people, with hundreds still missing . “The German language has no words, I think, for the devastation,” Chancellor Angela Merkel said.

Burned-out landscapes and dwindling water supplies are threatening Napa Valley, the heart of America’s wine industry .

Here’s the latest on the extreme heat and wildfires in the West.

Other Big Stories

A Japanese court sentenced two Americans to prison for helping the former Nissan leader Carlos Ghosn escape from Japan in a box.

Although the Me Too movement heightened awareness of the prevalence of sexual assault, the struggle to prosecute cases has endured.

Mat George, co-host of the podcast “She Rates Dogs,” died after a hit-and-run in Los Angeles. He was 26 .

The green economy is shaping up to be filled with grueling work schedules, few unions, middling wages and limited benefits, The Times’s Noam Scheiber reports .

Several governments use a cyberespionage tool to target rights activists, dissidents and journalists, leaked data suggests.

Tadej Pogacar, a 22-year-old cycling phenom from Slovenia, won his second straight Tour de France .

Bret Stephens and Gail Collins discuss big government .

MORNING READS

Into the woods: Smartphones are steering novice hikers onto trails they can’t handle .

Driven: Maureen Dowd meets Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s “weirdly normal” C.E.O.

The Games: Has the world had enough of the Olympics ?

A Times classic: Try this science-based 7-minute workout .

Quiz time: The average score on our most recent news quiz is 8.1 out of 11. See if you can do better .

Lives Lived: Gloria Richardson famously brushed aside a National Guardsman’s bayonet as she led a campaign for civil rights in Cambridge, Md. She died at 99 .

ARTS AND IDEAS

What matters in a name sign.

Shortly after the 2020 presidential election, five women teamed up to assign Vice President-elect Kamala Harris a name sign — the equivalent of a person’s name in American Sign Language.

The women — Ebony Gooden, Kavita Pipalia, Smita Kothari, Candace Jones and Arlene Ngalle-Paryani — are members of the “capital D Deaf community,” a term some deaf people use to indicate they embrace deafness as a cultural identity and communicate primarily through ASL.

Through social media, people submitted suggestions and put the entries to a vote. The result: A name sign that draws inspiration, among other things, from the sign for “lotus flower” — the translation of “Kamala” in Sanskrit — and the number three, highlighting Harris’s trifecta as the first Black, Indian and female vice president.

“Name signs given to political leaders are usually created by white men, but for this one we wanted to not only represent women, but diversity — Black women, Indian women,” Kothari said. Read more about it, and see videos of the signs . — Sanam Yar, a Morning writer

PLAY, WATCH, EAT

What to cook.

Debate ham and pineapple pizza all you want. There’s no denying the goodness of caramelized pineapple with sausages .

What to Watch

Based on books by R.L. Stine, the “Fear Street” trilogy on Netflix offers gore and nostalgia.

“ Skipped History ,” a comedy web series, explores overlooked people and events that shaped America.

Now Time to Play

The pangram from Friday’s Spelling Bee was lengthened . Here is today’s puzzle — or you can play online .

Here’s today’s Mini Crossword , and a clue: Hot tub nozzles (four letters).

If you’re in the mood to play more, find all our games here .

Thanks for spending part of your morning with The Times. See you tomorrow. — David

P.S. Ashley Wu , who has worked for Apple and New York magazine, has joined The Times as a graphics editor for newsletters. You’ll see her work in The Morning soon.

Here’s today’s print front page .

“ The Daily ” is about booster shots. On the Book Review podcast , S.A. Cosby talks about his new novel.

Lalena Fisher, Claire Moses, Ian Prasad Philbrick, Tom Wright-Piersanti and Sanam Yar contributed to The Morning. You can reach the team at [email protected] .

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox .

David Leonhardt writes The Morning, The Times's main daily newsletter. Previously at The Times, he was the Washington bureau chief, the founding editor of The Upshot, an Op-Ed columnist, and the head of The 2020 Project, on the future of the Times newsroom. He won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for commentary. More about David Leonhardt

Lessons learned: What makes vaccine messages persuasive

You’re reading Lessons Learned, which distills practical takeaways from standout campaigns and peer-reviewed research in health and science communication. Want more Lessons Learned? Subscribe to our Call to Action newsletter .

Vaccine hesitancy threatened public health’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientists at the University of Maryland recently reviewed 47 randomized controlled trials to determine how COVID-19 communications persuaded—or failed to persuade—people to take the vaccine. ( Health Communication , 2023 DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2023.2218145 ).

What they learned: Simply communicating about the vaccine’s safety or efficacy persuaded people to get vaccinated. Urging people to follow the lead of others, by highlighting how many millions were already vaccinated or even trying to induce embarrassment, was also persuasive.

Why it matters: Understanding which message strategies are likely to be persuasive is crucial.

➡️ Idea worth stealing: The authors found that a message’s source didn’t significantly influence its persuasiveness. But messages were more persuasive when source and receivers shared an identity, such as political affiliation.

What to watch: How other formats, such as interactive chatbots and videos, might influence persuasiveness. And whether message tailoring could persuade specific population subgroups.

News from the School

Nurturing student entrepreneurs

40 years after Bhopal disaster, suffering continues

Meet the Dean

Making health care more affordable

Coronavirus Disease 2019

The 7 best tactics to persuade the vaccine-hesitant, trying to convince someone to get vaccinated here are science’s best answers..

Posted June 23, 2021 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- Take our Your Mental Health Today Test

- Find a therapist near me

- Some of the most effective tactics for persuading the vaccine-hesitant were identified by researchers Stacy Wood and Kevin Schulman.

- Ways to convince someone who is hesitant to get vaccinated include sharing positive anecdotes and reminding them of the grim alternatives.

- Those who resist all vaccines need to be approached differently than others if they are to change their minds.

Like many, you might still be trying to convince a friend or family member to get vaccinated. In fact, I had this very issue myself. However, after using advice prescribed by this article from The New England Journal of Medicine , I was able to convince an older conservative male (one of the most vaccine-hesitant populations) to get his vaccine.

Researchers Stacy Wood and Kevin Schulman reviewed much of the behavioral research in the field to identify some of the most effective strategies for persuading the vaccine-hesitant. And although each person’s circumstance will dictate which approach will be most effective — and how it's implemented — these different strategies are some of the best science can offer.

1. Use Analogies to Explain the Vaccine

The vaccine can seem confusing or dangerous to people. So, comparing key aspects of the vaccine to examples they can understand (i.e., analogies) can be very effective.

For example, if someone doesn’t understand how the vaccine works, you can describe mRNA as “giving blueprints” to your immune cells so they know how to defeat the virus. Or, if the person is concerned about side effects, you can point out that vaccinated people have a better chance of being struck by lightning than dying from COVID-19.

2. Promote Control Through Compromise

Nobody likes to be forced into making a decision — which is how some people feel about getting this vaccine. However, research shows that if you can reduce the external pressure to do something, people actually become more likely to do it.

To help alleviate these feelings, try to emphasize how the person has control over which vaccine they’d like to get. Or even consider making a deal with the person: If they get vaccinated, you’ll do something they think is good for you that you’ve resisted. Helping to make the person’s decision feel less forced upon them can actually make them more willing to get it!

3. Find a Common Enemy With the Person

Sometimes, there is no truer saying than “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” And in the case of the COVID-19 vaccine, you can use this to your advantage. For example, considering how much damage this pandemic has done to the economy, you can point out how this person and the vaccine are on the same side — they’re both trying to get the economy back in action. Or, if there’s another country this person feels “in competition ” with, you can frame this person’s vaccination as national support in the vaccination race against this other country.

4. Combat Anecdotal Evidence With Your Own

For some individuals, their negativity toward vaccinations is based more on their feelings and emotions rather than any thoughts or reasons. For example, maybe they heard about someone who had a bad reaction to the vaccine. Rather than try to convince this person with statistics, it can actually be more effective to share positive anecdotes of your own. For example, you can share instances of people who had mild to no side effects from the vaccines, or stories about vaccinated people who didn’t catch COVID-19 in groups where it was otherwise spread.

5. Increase Awareness of Others Who Are Vaccinated

A classic finding from persuasion research is the power of the crowd. If most people are doing something, it is very compelling information that this person should do it, too. To that effect, try to point out respected friends or family members who have been vaccinated. Or similarly, if there is a public individual or aspirational role model the person likes, try to find one (or more) who have been vaccinated. Showing this individual that people they respect (e.g., top leaders from their preferred political party) are vaccinated can be very convincing.

6. Remind Them of Possible Regrets

Although a little grim, sometimes you need to remind people of the serious consequences of catching COVID-19. Activating these potential futures (e.g., where they have permanent organ damage because of COVID-19, or they feel guilt from spreading the disease to vulnerable family members) can be a powerful motivator. Of course, you don’t want to guilt-trip the person too much, but reminding them of their possible regret could help them understand the severity and value of getting vaccinated.

7. Point Out Events They Could Miss (Create FOMO)

On a lighter note, rather than focusing on all the negative events that could occur from catching COVID-19, focus on the positive events they would miss out on by not being vaccinated.

For example, you could remind them of the various bars and events that are only open to those who are vaccinated. Or, if it’s someone close to you, you could even create a great experience for them if they do get vaccinated. For example, you could tell them that you’ll take them for a night out, pamper them for a day, or offer any other kind of incentive if they’re willing to get vaccinated.

Now, of course, these aren’t all the strategies one could potentially employ, but they are some of the most proven. In implementing any of them, though, it’s important to remember that each person is different. So the advice above might require tweaking for who it’s being used on.

And of course, there will be some people who deny vaccines altogether (and they require different approaches than even these). However, for people who aren’t staunchly anti-vaccine — just maybe toward this COVID-19 one — hopefully something above will help you reach them.

Wood, S., & Schulman, K. (2021). Beyond Politics—Promoting Covid-19 Vaccination in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (23). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMms2033790

Jake Teeny , Ph.D. , is an assistant professor of marketing in the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, where he researches persuasion, metacognition, and consumer behavior.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

COVID vaccine hesitancy: spell out the personal rather than collective benefits to persuade people — new research

Professor of Clinical Psychology, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

Daniel Freeman receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research and the Medical Research Council. The current research was funded by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the NIHR Oxford Health BRC.

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Approximately 10% of UK adults say they will never get vaccinated against COVID-19 or will avoid doing so for as long as possible. Scientists call this group the “vaccine hesitant”, though hesitancy may not seem the right term to describe views often held with clear conviction. People who are vaccine hesitant have often thought long and hard about whether to take a COVID-19 vaccine.

How can such views be shifted? Ideally, one would sit down with people, listen and discuss. In reality, public health campaigners have only mass messaging at their disposal: information disseminated through billboards, TV slots and social media. These are crude tools for tackling sometimes deeply ingrained personal beliefs. What messages delivered through them might really make a difference?

Over the past year, the Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes and Narratives Surveys (OCEANS) team has tried to answer this question. We’ve worked to form a psychological explanation for vaccine hesitancy by canvassing the views of people for, against and undecided about vaccines.

We’ve found that hesitancy emerges from a nexus of beliefs , the most important being scepticism about the collective benefits of vaccination. The hesitant don’t accept that taking a vaccine means we’re all better off. They also tend to believe that COVID-19 isn’t a big danger to their health. And they worry that vaccines may be ineffective or downright harmful. The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines reinforces these concerns.

Behind these specific ideas often lies mistrust. People who are hesitant tend to be suspicious of authority . But while it’s wise to make judgements based on evidence rather than blithely accepting what we’re told, in many cases we’ve found that the vaccine hesitant are susceptible to misinformation.

Fuelling this may be a sense of marginalisation. Vaccine-hesitant people are a little more likely to believe that they’re of lower social status . Feeling that society doesn’t care about them, they are unwilling to trust what they’re told by politicians and scientists.

Getting personal

Equipped with these insights, we decided to see whether we could craft messages that might shift negative attitudes. If people don’t appreciate the collective benefits of vaccination, let’s persuasively set out the case. Let’s explain that vaccines make it less likely we’ll pass on the virus, helping to protect others, particularly those especially vulnerable to the virus. And let’s make it clear that by reducing the risk of getting severely ill, we can help the country bounce back as quickly as possible. That should help shift attitudes, right?

To find out, in early February we surveyed nearly 19,000 UK adults, carefully selected to be representative for age, gender, ethnicity, income and region. Participants were then randomly asked to read one of ten texts about COVID-19 vaccines.

Some texts focused the collective benefits of vaccination, some on the personal benefits, some on safety and some a combination of messages. One text contained only basic information about the vaccine and didn’t provide any detail on benefits, and was used as a control. After reading their allocated text, participants completed a questionnaire on their willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

The results were surprising. Previous surveys had suggested beliefs about the collective benefits of vaccination were pivotal to driving uptake. The extent to which people bought into this narrative seemed to determine their willingness to take a vaccine.

But the text that was most likely to change the minds of the vaccine hesitant (when compared to the control) emphasised not the collective but the personal benefits of vaccination. It pointed out that you can’t be sure that you won’t get seriously ill or struggle with long-term COVID-related problems, and that vaccination will minimise your chances of falling ill.

Months of media coverage in the UK has instead focused on collective responsibility – that we owe it to our fellow citizens to get vaccinated. But for the sceptical 10%, this hasn’t cut through, which is perhaps to be expected. If you think vaccines are unsafe, then you’ll be worried about what getting the jab will do to you. Your decision making then becomes dominated by personal risk.

The best way to counter these concerns, therefore, is to highlight the opposite: personal benefits – and our new research suggests this could well work. It’s also probable that for a group that’s more likely to feel socially excluded, messages that focus on the personal rather than collective ramifications of COVID-19 will be more compelling.

What about the view that the vaccines have been developed too quickly? It’s an understandable fear: these vaccines have been produced with unparalleled speed . In response to this, one text in our study explained that the speed of development reflects the exceptional commitment, investment and cooperation of scientists, governments, public health organisations and pharmaceutical companies – as well as of the tens of thousands of members of the public who volunteered to test the vaccines.

This text noted too that side-effects that affect a significant proportion of people don’t suddenly appear months and years after vaccination. Because of the way vaccines work – quickly training the body’s immune system to fight off a virus – any issues arise within a month and usually much sooner. Happily, this information did seem to reassure people and helped reduce hesitancy.

COVID-19 is unlikely to disappear in the foreseeable future, which means vaccination messaging will remain of critical importance. When it comes to persuading the vaccine hesitant, our research shows that we need to listen, understand concerns and address them seriously. No message will be truly effective if the messenger has not earned trust, nor if it doesn’t account for the desires and worries of those receiving it.

- Coronavirus

- Vaccine hesitancy

- Coronavirus insights

Editorial Internship

Research Fellow in Dark Matter Particle Phenomenology

Integrated Management of Invasive Pampas Grass for Enhanced Land Rehabilitation

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2021

Public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination: The role of vaccine attributes, incentives, and misinformation

- Sarah Kreps 1 ,

- Nabarun Dasgupta 2 ,

- John S. Brownstein 3 , 4 ,

- Yulin Hswen 5 &

- Douglas L. Kriner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9353-2334 1

npj Vaccines volume 6 , Article number: 73 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

82 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Translational research

While efficacious vaccines have been developed to inoculate against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; also known as COVID-19), public vaccine hesitancy could still undermine efforts to combat the pandemic. Employing a survey of 1096 adult Americans recruited via the Lucid platform, we examined the relationships between vaccine attributes, proposed policy interventions such as financial incentives, and misinformation on public vaccination preferences. Higher degrees of vaccine efficacy significantly increased individuals’ willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, while a high incidence of minor side effects, a co-pay, and Emergency Use Authorization to fast-track the vaccine decreased willingness. The vaccine manufacturer had no influence on public willingness to vaccinate. We also found no evidence that belief in misinformation about COVID-19 treatments was positively associated with vaccine hesitancy. The findings have implications for public health strategies intending to increase levels of community vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA

Vaccine hesitancy and monetary incentives

Providing normative information increases intentions to accept a COVID-19 vaccine

Introduction.

In less than a year, an array of vaccines was developed to bring an end to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. As impressive as the speed of development was the efficacy of vaccines such as Moderna and Pfizer, which are over 90%. Despite the growing availability and efficacy, however, vaccine hesitancy remains a potential impediment to widespread community uptake. While previous surveys indicate that overall levels of vaccine acceptance may be around 70% in the United States 1 , the case of Israel may offer a cautionary tale about self-reported preferences and vaccination in practice. Prospective studies 2 of vaccine acceptance in Israel showed that about 75% of the Israeli population would vaccinate, but Israel’s initial vaccination surge stalled around 42%. The government, which then augmented its vaccination efforts with incentive programs, attributed unexpected resistance to online misinformation 3 .

Research on vaccine hesitancy in the context of viruses such as influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella, suggests that misinformation surrounding vaccines is prevalent 4 , 5 . Emerging research on COVID-19 vaccine preferences, however, points to vaccine attributes as dominant determinants of attitudes toward vaccination. Higher efficacy is associated with greater likelihood of vaccinating 6 , 7 , whereas an FDA Emergency Use Authorization 6 or politicized approval timing 8 is associated with more hesitancy. Whether COVID-19 misinformation contributes to vaccine preferences or whether these attributes or policy interventions such as incentives play a larger role has not been studied. Further, while previous research has focused on a set of attributes that was relevant at one particular point in time, the evidence and context about the available vaccines has continued to shift in ways that could shape public willingness to accept the vaccine. For example, governments, employers, and economists have begun to think about or even devise ways to incentivize monetarily COVID-19 vaccine uptake, but researchers have not yet studied whether paying people to receive the COVID-19 vaccine would actually affect likely behavior. As supply problems wane and hesitancy becomes a limiting factor, understanding whether financial incentives can overcome hesitancy becomes a crucial question for public health. Further, as new vaccines such as Johnson and Johnson are authorized, knowing whether the vaccine manufacturer name elicits or deters interest in individuals is also important, as are the corresponding efficacy rates of different vaccines and the extent to which those affect vaccine preferences. The purpose of this study is to examine how information about vaccine attributes such as efficacy rates, the incidence of side effects, the nature of the governmental approval process, identity of the manufacturers, and policy interventions, including economic incentives, affect intention to vaccinate, and to examine the association between belief in an important category of misinformation—false claims concerning COVID-19 treatments—and willingness to vaccinate.

General characteristics of study population

Table 1 presents sample demographics, which largely reflect those of the US population as a whole. Of the 1335 US adults recruited for the study, a convenience sample of 1100 participants consented to begin the survey, and 1096 completed the full questionnaire. The sample was 51% female; 75% white; and had a median age of 43 with an interquartile range of 31–58. Comparisons of the sample demographics to those of other prominent social science surveys and U.S. Census figures are shown in Supplementary Table 1 .

Vaccination preferences

Each subject was asked to evaluate a series of seven hypothetical vaccines. For each hypothetical vaccine, our conjoint experiment randomly assigned values of five different vaccine attributes—efficacy, the incidence of minor side effects, government approval process, manufacturer, and cost/financial inducement. Descriptions of each attribute and the specific levels used in the experiment are summarized in Table 2 . After seeing the profile of each vaccine, the subject was asked whether she would choose to receive the vaccine described, or whether she would choose not to be vaccinated. Finally, subjects were asked to indicate how likely they would be to take the vaccine on a seven-point likert scale.

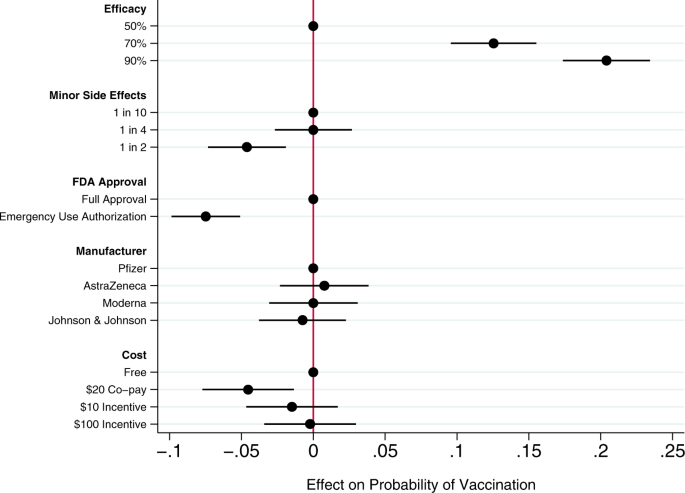

Across all choice sets, in 4419 cases (58%) subjects said they would choose the vaccine described in the profile rather than not being vaccinated. As shown in Fig. 1 , several characteristics of the vaccine significantly influenced willingness to vaccinate.

Circles present the estimated effect of each attribute level on the probability of a subject accepting vaccination from the attribute’s baseline level. Horizontal lines through points indicate 95% confidence intervals. Points without error bars denote the baseline value for each attribute. The average marginal component effects (AMCEs) are the regression coefficients reported in model 1 of Table 3 .

Efficacy had the largest effect on individual vaccine preferences. An efficacy rate of 90% increased uptake by about 20% relative to the baseline at 50% efficacy. Even a high incidence of minor side effects (1 in 2) had only a modest negative effect (about 5%) on willingness to vaccinate. Whether the vaccine went through full FDA approval or received an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), an authority that allows the Food and Drug Administration mechanisms to accelerate the availability and use of treatments or medicines during medical emergencies 9 , significantly influenced willingness to vaccinate. An EUA decreased the likelihood of vaccination by 7% compared to a full FDA authorization; such a decline would translate into about 23 million Americans. While a $20 co-pay reduced the likelihood of vaccination relative to a no-cost baseline, financial incentives did not increase willingness to vaccinate. Lastly, the manufacturer had no effect on vaccination attitudes, despite the public pause of the AstraZeneca trial and prominence of Johnson & Johnson as a household name (our experiment was fielded before the pause in the administration of the Johnson & Johnson shot in the United States).

Model 2 of Table 3 presents an expanded model specification to investigate the association between misinformation and willingness to vaccinate. The primary additional independent variable of interest is a misinformation index that captures the extent to which each subject believes or rejects eight claims (five false; three true) about COVID-19 treatments. Additional analyses using alternate operationalizations of the misinformation index yield substantively similar results (Supplementary Table 4 ). This model also includes a number of demographic control variables, including indicators for political partisanship, gender, educational attainment, age, and race/ethnicity, all of which are also associated with belief in misinformation about the vaccine (Supplementary Table 2 ). Finally, the model also controls for subjects’ health insurance status, past experience vaccinating against seasonal influenza, attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry, and beliefs about vaccine safety generally.

Greater levels of belief in misinformation about COVID-19 treatments were not associated with greater vaccine hesitancy. Instead, the relevant coefficient is positive and statistically significant, indicating that, all else being equal, individuals who scored higher on our index of misinformation about COVID-19 treatments were more willing to vaccinate than those who were less susceptible to believing false claims.

Strong beliefs that vaccines are safe generally was positively associated with willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, as were past histories of frequent influenza vaccination and favorable attitudes toward the pharmaceutical industry. Women and older subjects were significantly less likely to report willingness to vaccinate than men and younger subjects, all else equal. Education was positively associated with willingness to vaccinate.

This research offers a comprehensive examination of attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, particularly the role of vaccine attributes, potential policy interventions, and misinformation. Several previous studies have analyzed the effects of vaccine characteristics on willingness to vaccinate, but the modal approach is to gauge willingness to accept a generic COVID-19 vaccine 10 , 11 . Large volumes of research show, however, that vaccine preferences hinge on specific vaccine attributes. Recent research considering the influence of attributes such as efficacy, side effects, and country of origin take a step toward understanding how properties affect individuals’ intentions to vaccinate 6 , 7 , 8 , 12 , 13 , but evidence about the attributes of actual vaccines, debates about how to promote vaccination within the population, and questions about the influence of misinformation have moved quickly 14 .

Our conjoint experiment therefore examined the influence of five vaccine attributes on vaccination willingness. The first category of attributes involved aspects of the vaccine itself. Since efficacy is one of the most common determinants of vaccine acceptance, we considered different levels of efficacy, 50%, 70%, and 90%, levels that are common in the literature 7 , 15 . Evidence from Phase III trials suggests that even the 90% efficacy level in our design, which is well above the 50% threshold from the FDA Guidance for minimal effectiveness for Emergency Use Authorization 16 , has been exceeded by both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines 17 , 18 . The 70% efficacy threshold is closer to the initial reports of the efficacy of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, whose efficacy varied across regions 19 . Our analysis suggests that efficacy levels associated with recent mRNA vaccine trials increases public vaccine uptake by 20% over a baseline of a vaccine with 50% efficacy. A 70% efficacy rate increases public willingness to vaccinate by 13% over a baseline vaccine with 50% efficacy.

An additional set of epidemiological attributes consisted of the frequency of minor side effects. While severe side effects were plausible going into early clinical trials, evidence clearly suggests that minor side effects are more common, ranging from 10% to 100% of people vaccinated depending on the number of doses and the dose group (25–250 mcg) 20 . Since the 100 mcg dose was supported in Phase III trials 21 , we include the highest adverse event probability—approximating 60% as 1 in 2—and 1 in 10 as the lowest likelihood, approximating the number of people who experienced mild arthralgia 20 . Our findings suggest that a the prevalence of minor side effects associated with recent trials (i.e. a 1 in 2 chance), intention to vaccinate decreased by about 5% versus a 1 in 10 chance of minor side effects baseline. However, at a 25% rate of minor side effects, respondents did not indicate any lower likelihood of vaccination compared to the 10% baseline. Public communications about how to reduce well-known side effects, such as pain at the injection site, could contribute to improved acceptance of the vaccine, as it is unlikely that development of vaccine-related minor side effects will change.

We then considered the effect of EUA versus full FDA approval. The influenza H1N1 virus brought the process of EUA into public discourse 22 , and the COVID-19 virus has again raised the debate about whether and how to use EUA. Compared to recent studies also employing conjoint experimental designs that showed just a 3% decline in support conditional on EUA 6 , we found decreases in support of more than twice that with an EUA compared to full FDA approval. Statements made by the Trump administration promising an intensely rapid roll-out or isolated adverse events from vaccination in the UK may have exacerbated concerns about EUA versus full approval 8 , 23 , 24 , 25 . This negative effect is even greater among some subsets of the population. As shown in additional analyses reported in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 5 ), the negative effects are greatest among those who believe vaccines are generally safe. Among those who believe vaccines generally are extremely safe, the EUA decreased willingness to vaccinate by 11%, all else equal. This suggests that outreach campaigns seeking to assure those troubled by the authorization process used for currently available vaccines should target their efforts on those who are generally predisposed to believe vaccines are safe.

Next, we compared receptiveness as a function of the manufacturer: Moderna, Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson, and AstraZeneca, all firms at advanced stages of vaccine development. Vaccine manufacturers in the US have not yet attempted to use trade names to differentiate their vaccines, instead relying on the association with manufacturer reputation. In other countries, vaccine brand names have been more intentionally publicized, such as Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin in India and Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology Sputnik V in Russia. We found that manufacturer names had no impact on willingness to vaccinate. As with hepatitis and H. influenzae vaccines 26 , 27 , interchangeability has been an active topic of debate with coronavirus mRNA vaccines which require a second shot for full immunity. Our research suggests that at least as far as public receptiveness goes, interchangeability would not introduce concerns. We found no significant differences in vaccination uptake across any of the manufacturer treatments. Future research should investigate if a manufacturer preference develops as new evidence about efficacy and side effects becomes available, particularly depending on whether future booster shots, if needed, are deemed interchangeable with the initial vaccination.

Taking up the question of how cost and financial incentives shape behavior, we looked at paying and being paid to vaccinate. While existing research suggests that individuals are often willing to pay for vaccines 28 , 29 , some economists have proposed that the government pay individuals up to $1,000 to take the COVID-19 vaccine 30 . However, because a cost of $300 billion to vaccinate the population may be prohibitive, we posed a more modest $100 incentive. We also compared this with a $10 incentive, which previous studies suggest is sufficient for actions that do not require individuals to change behavior on a sustained basis 31 . While having to pay a $20 co-pay for the vaccine did deter individuals, the additional economic incentives had no positive effect although they did not discourage vaccination 32 . Consistent with past research 31 , 33 , further analysis shows that the negative effect of the $20 co-pay was concentrated among low-income earners (Supplementary Fig. 7 ). Financial incentives failed to increase vaccination willingness across income levels.

Our study also yields important insights into the relationship between one prominent category of COVID-19 misinformation and vaccination preferences. We find that susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 treatments—based on whether individuals can distinguish between factual and false information about efforts to combat COVID-19—is considerable. A quarter of subjects scored no higher on our misinformation index than random guessing or uniform abstention/unsure responses (for the full distribution, see Supplementary Fig. 2 ). However, subjects who scored higher on our misinformation index did not exhibit greater vaccination hesitancy. These subjects actually were more likely to believe in vaccine safety more generally and to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, all else being equal. These results run counter to recent findings of public opinion in France where greater conspiracy beliefs were negatively correlated with willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 34 and in Korea where greater misinformation exposure and belief were negatively correlated with taking preventative actions 35 . Nevertheless, the results are robust to alternate operationalizations of belief in misinformation (i.e., constructing the index only using false claims, or measuring misinformation beliefs as the number of false claims believed: see Supplementary Table 4 ).

We recommend further study to understand the observed positive relationship between beliefs in COVID-19 misinformation about fake treatments and willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. To be clear, we do not posit a causal relationship between the two. Rather, we suspect that belief in misinformation may be correlated with an omitted factor related to concerns about contracting COVID-19. For example, those who believe COVID-19 misinformation may have a higher perception of risk of COVID-19, and therefore be more willing to take a vaccine, all else equal 36 . Additional analyses reported in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 6 ) show that the negative effect of an EUA on willingness to vaccinate was concentrated among those who scored low on the misinformation index. An EUA had little effect on the vaccination preferences of subjects most susceptible to misinformation. This pattern is consistent with the possibility that these subjects were more concerned with the disease and therefore more likely to vaccinate, regardless of the process through which the vaccine was brought to market.

We also observe that skepticism toward vaccines in general does not correlate perfectly with skepticism toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, it is important not to conflate people who are wary of the COVID-19 vaccine and those who are anti-vaccination, as even medically informed individuals may be hesitant because of the speed at which the COVID-19 vaccine was developed. For example, older people are more likely to believe vaccines are safe but less willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in our survey, perhaps following the high rates of vaccine skepticism among medical staff expressing concerns regarding the safety of a rapidly-developed vaccine 2 . This inverse relationship between age and willingness to vaccinate is also surprising. Most opinion surveys find older adults are more likely to vaccinate than younger adults 37 . However, most of these survey questions ask about willingness to take a generic vaccine. Two prior studies, both recruiting subjects from the Lucid platform and employing conjoint experiments to examine the effects of vaccine attributes on public willingness to vaccinate, also find greater vaccine hesitancy among older Americans 6 , 7 . Future research could explore whether these divergent results are a product of the characteristics of the sample or of the methodological design in which subjects have much more information about the vaccines when indicating their vaccination preferences.

An important limitation of our study is that it necessarily offers a snapshot in time, specifically prior to both the election and vaccine roll-out. We recommend further study to understand more how vaccine perceptions evolve both in terms of the perceived political ownership of the vaccine—now that President Biden is in office—and as evidence has emerged from the millions of people who have been vaccinated. Similarly, researchers should consider analyzing vaccine preferences in the context of online vaccine controversies that have been framed in terms of patient autonomy and right to refuse 38 , 39 . Vaccination mandates may evoke feelings of powerlessness, which may be exacerbated by misinformation about the vaccines themselves. Further, researchers should more fully consider how individual attributes such as political ideology and race intersect with vaccine preferences. Our study registered increased vaccine hesitancy among Blacks, but did not find that skepticism was directly related to misinformation. Perceptions and realities of race-based maltreatment could also be moderating factors worth exploring in future analyses 40 , 41 .

Overall, we found that the most important factor influencing vaccine preferences is vaccine efficacy, consistent with a number of previous studies about attitudes toward a range of vaccines 6 , 42 , 43 . Other attributes offer potential cautionary flags and opportunities for public outreach. The prospect of a 50% likelihood of mild side effects, consistent with the evidence about current COVID-19 vaccines being employed, dampens likelihood of uptake. Public health officials should reinforce the relatively mild nature of the side effects—pain at the injection site and fatigue being the most common 44 —and especially the temporary nature of these effects to assuage public concerns. Additionally, in considering policy interventions, public health authorities should recognize that a $20 co-pay will likely discourage uptake while financial incentives are unlikely to have a significant positive effect. Lastly, belief in misinformation about COVID-19 does not appear to be a strong predictor of vaccine hesitancy; belief in misinformation and willingness to vaccinate were positively correlated in our data. Future research should explore the possibility that exposure to and belief in misinformation is correlated with other factors associated with vaccine preferences.

Survey sample and procedures

This study was approved by the Cornell Institutional Review Board for Human Participant Research (protocol ID 2004009569). We conducted the study on October 29–30, 2020, prior to vaccine approval, which means we captured sentiments prospectively rather than based on information emerging from an ongoing vaccination campaign. We recruited a sample of 1096 adult Americans via the Lucid platform, which uses quota sampling to produce samples matched to the demographics of the U.S. population on age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region. Research has shown that experimental effects observed in Lucid samples largely mirror those found using probability-based samples 45 . Supplementary Table 1 presents the demographics of our sample and comparisons to both the U.S. Census American Community Survey and the demographics of prominent social science surveys.

After providing informed consent on the first screen of the online survey, participants turned to a choice-based conjoint experiment that varied five attributes of the COVID-19 vaccine. Conjoint analyses are often used in marketing to research how different aspects of a product or service affect consumer choice. We build on public health studies that have analyzed the influence of vaccine characteristics on uptake within the population 42 , 46 .

Conjoint experiment

We first designed a choice-based conjoint experiment that allowed us to evaluate the relative influence of a range of vaccine attributes on respondents’ vaccine preferences. We examined five attributes summarized in Table 2 . Past research has shown that the first two attributes, efficacy and the incidence of side effects, are significant drivers of public preferences on a range of vaccines 47 , 48 , 49 , including COVID-19 6 , 7 , 13 , 50 . In this study, we increased the expected incidence of minor side effects from previous research 6 to reflect emerging evidence from Phase III trials. The third attribute, whether the vaccine received full FDA approval or an EUA, examines whether the speed of the approval process affects public vaccination preferences 6 . The fourth attribute, the manufacturer of the vaccine, allows us to examine whether the highly public pause in the AstraZeneca trial following an adverse event, and the significant differences in brand familiarity between smaller and less broadly known companies like Moderna and household name Johnson & Johnson affects public willingness to vaccinate. The fifth attribute examines the influence of a policy tool—offsetting the costs of vaccination or even incentivizing it financially—on public willingness to vaccinate.

Attribute levels and attribute order were randomly assigned across participants. A sample choice set is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 . After viewing each profile individually, subjects were asked: “If you had to choose, would you choose to get this vaccine, or would you choose not to be vaccinated?” Subjects then made a binary choice, responding either that they “would choose to get this vaccine” or that they “would choose not to be vaccinated.” This is the dependent variable for the regression analyses in Table 3 . After making a binary choice to take the vaccine or not be vaccinated, we also asked subjects “how likely or unlikely would you be to get the vaccine described above?” Subjects indicated their vaccination preference on a seven-point scale ranging from “extremely likely” to “extremely unlikely.” Additional analyses using this ordinal dependent variable reported in Supplementary Table 3 yield substantively similar results to those presented in Table 3 .

To determine the effect of each attribute-level on willingness to vaccinate, we followed Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto and employed an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with standard errors clustered on respondent to estimate the average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for each attribute 51 . The AMCE represents the average difference in a subject choosing a vaccine when comparing two different attribute values—for example, 50% efficacy vs. 90% efficacy—averaged across all possible combinations of the other vaccine attribute values. The AMCEs are nonparametrically identified under a modest set of assumptions, many of which (such as randomization of attribute levels) are guaranteed by design. Model 1 in Table 3 estimates the AMCEs for each attribute. These AMCEs are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Analyzing additional correlates of vaccine acceptance

To explore the association between respondents’ embrace of misinformation about COVID-19 treatments and vaccination willingness, the survey included an additional question battery. To measure the extent of belief in COVID-19 misinformation, we constructed a list of both accurate and inaccurate headlines about the coronavirus. We focused on treatments, relying on the World Health Organization’s list of myths, such as “Hand dryers are effective in killing the new coronavirus” and true headlines such as “Avoiding shaking hands can help limit the spread of the new coronavirus 52 .” Complete wording for each claim is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1 . Individuals read three true headlines and five myths, and then responded whether they believed each headline was true or false, or whether they were unsure. We coded responses to each headline so that an incorrect accuracy assessment yielded a 1; a correct accuracy assessment a -1; and a response of unsure was coded as 0. From this, we created an additive index of belief in misinformation that ranged from -8 to 8. The distribution of the misinformation index is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2 . A possible limitation of this measure is that because the survey was conducted online, some individuals could have searched for the answers to the questions before responding. However, the median misinformation index score for subjects in the top quartile in terms of time spent taking the survey was identical to the median for all other respondents. This may suggest that systematic searching for correct answers is unlikely.

To ensure that any association observed between belief in misinformation and willingness to vaccinate is not an artifact of how we operationalized susceptibility to misinformation, we also constructed two alternate measures of belief in misinformation. These measures are described in detail in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 ). Additional regression analyses using these alternate measures of misinformation beliefs yield substantively similar results (see Supplementary Table 4 ). Additional analyses examining whether belief in misinformation moderates the effect of efficacy and an FDA EUA on vaccine acceptance are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 .