- NEWSLETTER SIGN UP

The Research Committee is dedicated to encouraging, supporting, and promoting a broad base of research that is grounded in diverse methodologies. By providing information to the public and the membership, the committee promotes standards of art therapy research, produces a registry of outcomes based research, and honors professional and student research activity.

Art therapy priority research areas, focusing research efforts in the following areas:.

- Outcome/efficacy research

- Art therapy and neuroscience

- Research on the processes and mechanisms in art therapy

- Art therapy assessment validity and reliability

- Cross-cultural/multicultural approaches to art therapy assessment and practice

- Establishment of a database of normative artwork across the lifespan

SEEKING TO ADDRESS THE FOLLOWING RESEARCH QUESTIONS:

- What interventions produce specific outcomes with particular populations or specific disorders?

- How does art therapy compare to other therapeutic disciplines that do not include art practice in terms of various outcomes?

- How reliable and valid is any art therapy assessment?

- What neurobiological processes are involved in art making during art therapy?

- To what extent do a person’s verbal associations to artwork created in art therapy enhance, support, or contradict?

- What are ways of making art therapy more effective for clients of different ethnic and racial backgrounds?

SUGGESTED POPULATIONS TO RESEARCH:

- Psychiatric major mental illness

- Medical/Cancer

- At-risk youth in schools

BIBLIOGRAPHIC SEARCH TOOL

AATA’s Art Therapy Bibliographic Search Tool allows you to find listings of art therapy publications and theses from FOUR research sources: the Art Therapy Outcomes Bibliography, the Art Therapy Assessment Bibliography, the Multicultural Committee Selected Bibliography and Resource List, and the National Art Therapy Thesis and Dissertation Abstract Compilation.

The Art Therapy Bibliographic Search Tool enables you to search bibliographic entries based on one or all of the following characteristics: author name, category/treatment group, keywords, title, reference type, and year of publication.

AATA Member Exclusive: All AATA members have the benefit of viewing more details about each database entry, including abstracts, topics, and comments!

- 1 College of Creative Design, Shenzhen Technology University, Shenzhen, China

- 2 The Fourth Clinical Medical College of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China

- 3 Institute of Biomedical and Health Engineering, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, China

Art therapy, as a non-pharmacological medical complementary and alternative therapy, has been used as one of medical interventions with good clinical effects on mental disorders. However, systematically reviewed in detail in clinical situations is lacking. Here, we searched on PubMed for art therapy in an attempt to explore its theoretical basis, clinical applications, and future perspectives to summary its global pictures. Since drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as a useful part of therapeutic processes in art therapy, we focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. As a result, a total of 413 literature were identified. After carefully reading full articles, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These disorders mainly include depression disorders and anxiety, cognitive impairment and dementias, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and autism. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests. We humbly believe that art therapy has great potential in clinical applications on mental disorders to be further explored.

Introduction

Mental disorders constitute a huge social and economic burden for health care systems worldwide ( Zschucke et al., 2013 ; Kenbubpha et al., 2018 ). In China, the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders was 24.20%, and 1-month prevalence of mental disorders was 14.27% ( Xu et al., 2017 ). The situation is more severely in other countries, especially for developing ones. Given the large numbers of people in need and the humanitarian imperative to reduce suffering, there is an urgent need to implement scalable mental health interventions to address this burden. While pharmacological treatment is the first choice for mental disorders to alleviate the major symptoms, many antipsychotics contribute to poor quality of life and debilitating adverse effects. Therefore, clinicians have turned toward to complementary treatments, such as art therapy in addressing the health needs of patients more than half a century ago.

Art therapy, is defined by the British Association of Art Therapists as: “a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of expression and communication. Clients referred to art therapists are not required to have experience or skills in the arts. The art therapist’s primary concern is not to make an esthetic or diagnostic assessment of the client’s image. The overall goal of its practitioners is to enable clients to change and grow on a personal level through the use of artistic materials in a safe and convenient environment” ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ), whereas as: “an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psycho-therapeutic relationship” ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ) according to the American Art Association. It has gradually become a well-known form of spiritual support and complementary therapy ( Faller and Schmidt, 2004 ; Nainis et al., 2006 ). During the therapy, art therapists can utilize many different art materials as media (i.e., visual art, painting, drawing, music, dance, drama, and writing) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). Among them, drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as the most useful part of therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ). Moreover, many other art forms gradually fall under the prevue of their own professions (e.g., music therapy, dance/movement therapy, and drama therapy) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). Thus, we excluded these studies and only focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. Specifically, it focuses on capturing psychodynamic processes by means of “inner pictures,” which become visible by the creative process ( Steinbauer et al., 1999 ). These pictures reflect the psychopathology of different psychiatric disorders and even their corresponding therapeutic process based on specific rules and criterion ( Steinbauer and Taucher, 2001 ). It has been gradually recognized and used as an alternative treatment for therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties, as well as medical and neurology-based scientific audiences ( Burton, 2009 ).

The development of art therapy comes partly from the artistic expression of the belief in unspoken things, and partly from the clinical work of art therapists in the medical setting with various groups of patients ( Malchiodi, 2013 ). It is defined as the application of artistic expressions and images to individuals who are physically ill, undergoing invasive medical procedures, such as surgery or chemotherapy for clinical usage ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Forzoni et al., 2010 ; Liebmann and Weston, 2015 ). The American Art Therapy Association describes its main functions as improving cognitive and sensorimotor functions, fostering self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivating emotional resilience, promoting insight, enhancing social skills, reducing and resolving conflicts and distress, and promoting societal and ecological changes ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ).

However, despite the above advantages, published systematically review on this topic is lacking. Therefore, this review aims to explore its clinical applications and future perspectives to summary its global pictures, so as to provide more clinical treatment options and research directions for therapists and researchers.

Publications of Art Therapy

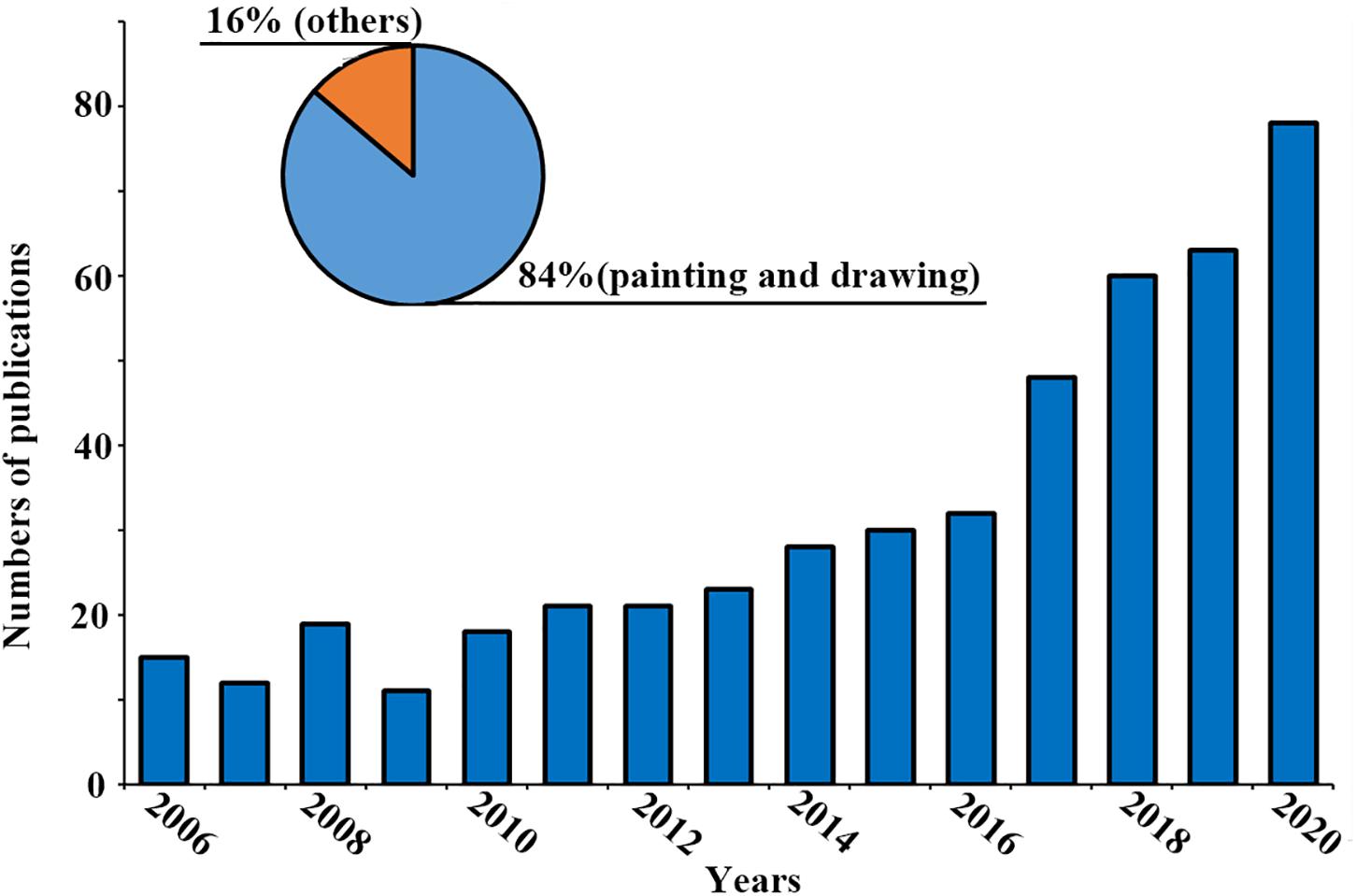

The literatures about “art therapy” published from January 2006 to December 2020 were searched in the PubMed database. The following topics were used: Title/Abstract = “art therapy,” Indexes Timespan = 2006–2020.

A total of 652 records were found. Then, we manually screened out the literatures that contained the word “art” but was not relevant with the subject of this study, such as state of the art therapy, antiretroviral therapy (ART), and assisted reproductive technology (ART). Finally, 479 records about art therapy were identified. Since we aimed to focus on art therapy included painting and drawing as major media, we screened out literatures deeper, and identified 413 (84%) literatures involved in painting and drawing ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Number of publications about art therapy.

As we can see, the number of literature about art therapy is increasing slowly in the last 15 years, reaching a peak in 2020. This indicates that more effort was made on this topic in recent years ( Figure 1 ).

Overview of Art Therapy

As defined by the British Association of Art Therapists, art therapy is a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of communication. Based on above literature, several highlights need to be summarized. (1) The main media of art therapy include painting, drawing, music, drama, dance, drama, and writing ( Chiang et al., 2019 ). (2) Main contents of painting and drawing include blind drawing, spiral drawing, drawing moods and self-portraits ( Legrand et al., 2017 ; Abbing et al., 2018 ; Papangelo et al., 2020 ). (3) Art therapy is mainly used for cancer, depression and anxiety, autism, dementia and cognitive impairment, as these patients are reluctant to express themselves in words ( Attard and Larkin, 2016 ; Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). It plays an important role in facilitating engagement when direct verbal interaction becomes difficult, and provides a safe and indirect way to connect oneself with others ( Papangelo et al., 2020 ). Moreover, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests.

Art Therapy for Mental Disorders

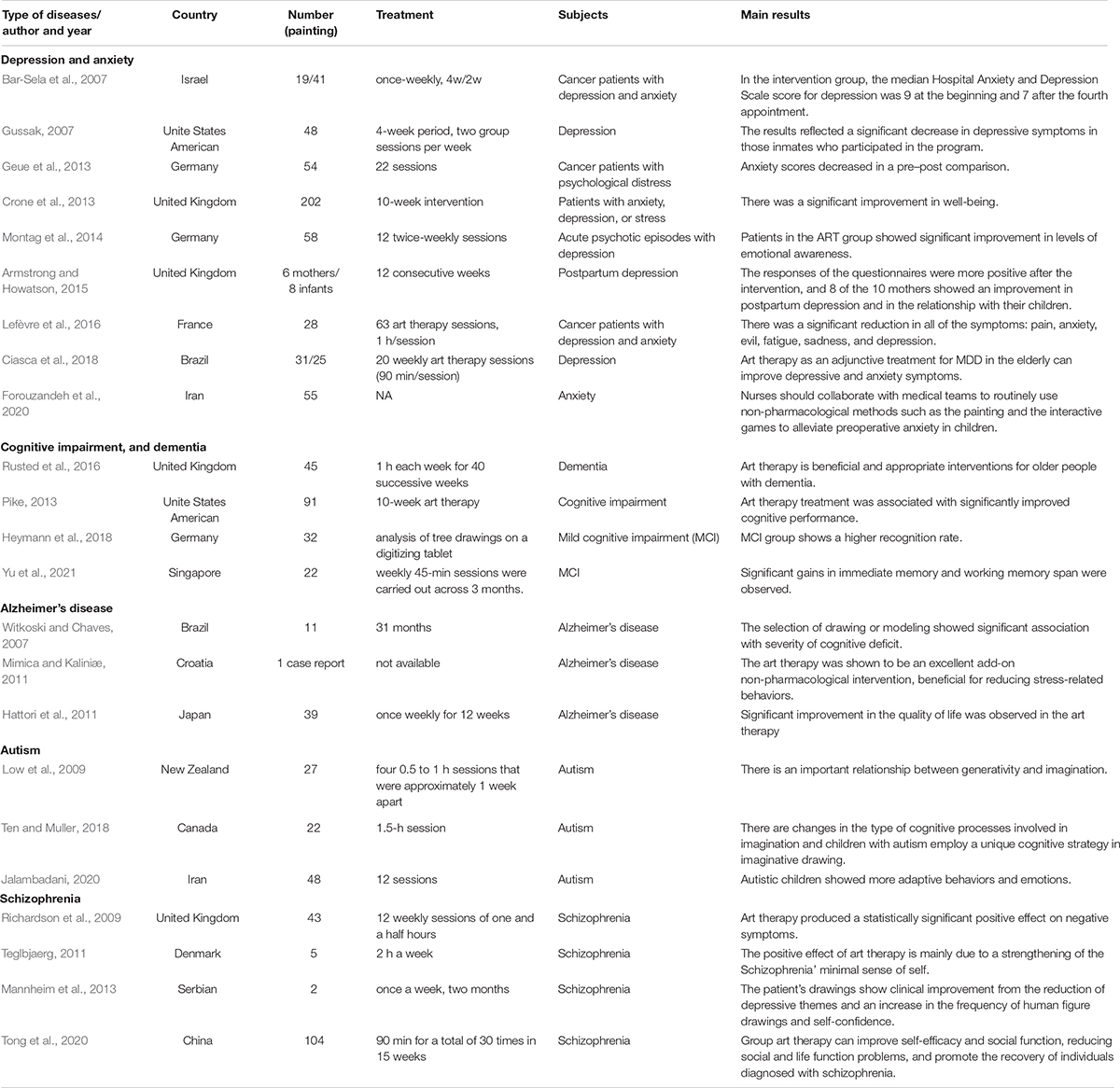

Based on the 413 searched literatures, we further limited them to mental disorders using the following key words, respectively: Depression OR anxiety OR Cognitive impairment OR dementia OR Alzheimer’s disease OR Autism OR Schizophrenia OR mental disorder. As a result, a total of 23 studies (5%) ( Table 1 ) were included and classified after reading the abstract and the full text carefully. These studies include 9 articles on depression and anxiety, 4 articles on cognitive impairment and dementia, 3 articles on Alzheimer’s disease, 3 articles on autism, and 4 articles on schizophrenia. In addition to the English literature, in fact, some Chinese literatures also described the application of art therapy in mental diseases, which were not listed but referred to in the following specific literatures.

Table 1. Studies of art therapy in mental diseases.

Depression Disorders and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent, affecting individuals, their families and the individual’s role in society ( Birgitta et al., 2018 ). Depression is a disabling and costly condition associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, medical comorbidities and mortality ( Demyttenaere et al., 2004 ; Whiteford et al., 2013 ; Cuijpers et al., 2014 ). Anxiety is associated with lower quality of life and negative effects on psychosocial functioning ( Cramer et al., 2005 ). Medication is the most commonly used effective way to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, nonadherence are crucial shortcomings in using antidepressant to treat depression and anxiety ( van Geffen et al., 2007 ; Nielsen et al., 2019 ).

In recent years, many studies have shown that art therapy plays a significant role in alleviating depression symptoms and anxiety. Gussak (2007) performed an observational survey about populations in prison of northern Florida and identified that art therapy significantly reduces depressive symptoms. Similarly, a randomized, controlled, and single-blind study about art therapy for depression with the elderly showed that painting as an adjuvant treatment for depression can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms ( Ciasca et al., 2018 ). In addition, art therapy is also widely used among students, and several studies ( Runde, 2008 ; Zhenhai and Yunhua, 2011 ) have shown that art therapy also significantly reduces depressive symptoms in students. For example, Wang et al. (2011) conducted group painting therapy on 30 patients with depression for 3 months, and found that painting therapy could promote their social function recovery, improve their social adaptability and quality of life. Another randomized clinical trial also showed that it could decrease mean anxiety scores in the 3–12 year painting group ( Forouzandeh et al., 2020 ).

Studies have shown that distress, including anxiety and depression, is related to poorer health-related quality of life and satisfaction to medical services ( Hamer et al., 2009 ). Painting can be employed to express patients’ anxiety and fear, vent negative emotions by applying projection, thereby significantly improve the mood and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety of cancer patients. A number of studies ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Thyme et al., 2009 ; Lin et al., 2012 ; Abdulah and Abdulla, 2018 ) showed that art therapy for cancer patients could enhance the vitality of patients and participation in social activities, significantly reduce depression, anxiety, and reduce stressful feelings. Importantly, even in the follow-up period, art therapy still has a lasting effect on cancer patients ( Thyme et al., 2009 ). Interestingly, art therapy based on famous painting appreciation could also significantly reduce anxiety and depression associated with cancer ( Lee et al., 2017 ). Among cancer patients treated in outpatient health care, art therapy also plays an important role in alleviating their physical symptoms and mental health ( Götze et al., 2009 ). Therefore, art therapy as an auxiliary treatment of cancer is of great value in improving quality of life.

Overall, art painting therapy permits patients to express themselves in a manner acceptable to the inside and outside culture, thereby diminishing depressed and anxiety symptoms.

Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia

Dementia, a progressive clinical syndrome, is characterized by widespread cognitive impairment in memory, thinking, behavior, emotion and performance, leading to worse daily living ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). According to the Alzheimer’s Disease International 2015, there is 46.8 million people suffered from dementia, and numbers almost doubling every 20 years, rising to 131.5 million by 2050. Although art therapy has been used as an alternative treatment for the dementia for long time, the positive effects of painting therapy on cognitive function remain largely unknown. One intervention assigned older adults patients with dementia to a group-based art therapy (including painting) observed significant improvements in the clock drawing test ( Pike, 2013 ), whereas two other randomized controlled trials ( Hattori et al., 2011 ; Rusted et al., 2016 ) on patients with dementia have failed to obtain significant cognitive improvement in the painting group. Moreover, a cochrane systematic review ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ) included two clinical studies of art therapy for dementia revealed that there is no sufficient evidence about the efficacy of art therapy for dementia. This may be because patients with severely cognitive impairment, who was unable to accurately remember or assess their own behavior or mental state, might lose the ability to enjoy the benefits of art therapy.

In summary, we should intervene earlier in patients with mild cognitive impairment, an intermediate stage between normal aging and dementia, in order to prevent further transformation into dementia. To date, mild cognitive impairment is drawing much attention to the importance of painting intervening at this stage in order to alter the course of subsequent cognitive decline as soon as possible ( Petersen et al., 2014 ). Recently, a randomized controlled trial ( Yu et al., 2021 ) showed significant relationship between improvement immediate memory/working memory span and increased cortical thickness in right middle frontal gyrus in the painting art group. With the long-term cognitive stimulation and engagement from multiple sessions of painting therapy, it is likely that painting therapy could lead to enhanced cognitive functioning for these patients.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a sub-type of dementia, which is usually associated with chronic pain. Previous studies suggested that art therapy could be used as a complementary treatment to relief pain for these patients since medication might induce severely side effects. In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, 28 mild AD patients showed significant pain reduction, reduced anxiety, improved quality of life, improved digit span, and inhibitory processes, as well as reduced depression symptoms after 12-week painting ( Pongan et al., 2017 ; Alvarenga et al., 2018 ). Further study also suggested that individual therapy rather than group therapy could be more optimal since neuroticism can decrease efficacy of painting intervention on pain in patients with mild AD. In addition to release chronic pain, art therapy has been reported to show positive effects on cognitive and psychological symptoms in patients with mild AD. For example, a controlled study revealed significant improvement in the apathy scale and quality of life after 12 weeks of painting treatment mainly including color abstract patterns with pastel crayons or water-based paint ( Hattori et al., 2011 ). Another study also revealed that AD patients showed improvement in facial expression, discourse content and mood after 3-weeks painting intervention ( Narme et al., 2012 ).

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a complex functional psychotic mental illness that affects about 1% of the population at some point in their life ( Kolliakou et al., 2011 ). Not only do sufferers experience “positive” symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, but also experience negative symptoms such as varying degrees of anhedonia and asociality, impaired working memory and attention, poverty of speech, and lack of motivation ( Andreasen and Olsen, 1982 ). Many patients with schizophrenia remain symptomatic despite pharmacotherapy, and even attempts to suicide with a rate of 10 to 50% ( De Sousa et al., 2020 ). For these patients, art therapy is highly recommended to process emotional, cognitive and psychotic experiences to release symptoms. Indeed, many forms of art therapy have been successfully used in schizophrenia, whether and how painting may interfere with psychopathology to release symptoms remains largely unknown.

A recent review including 20 studies overall was performed to summary findings, however, concluded that it is not clear whether art therapy leads to clinical improvement in schizophrenia with low ( Ruiz et al., 2017 ). Anyway, many randomized clinical trials reported positive outcomes. For example, Richardson et al. (2007) conducted painting therapy for six months in patients with chronic schizophrenia and found that art therapy had a positive effect on negative symptoms. Teglbjaerg (2011) examined experience of each patient using interviews and written evaluations before and after painting therapy and at a 1-year follow-up and found that group painting therapy in patients with schizophrenia could not only reduce psychotic symptoms, but also boost self-esteem and improve social function.

What’s more, the characteristics of the painting can also be used to judge the health condition in patients with schizophrenia. For example, Hongxia et al. (2013) explored the correlation between psychological health condition and characteristics of House-Tree-Person tests for patients with schizophrenia, and showed that the detail characteristic of the test results can be used to judge the patient’s anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Most importantly, several other studies showed that drug plus painting therapy significantly enhanced patient compliance and self-cognition than drug therapy alone in patients with schizophrenia ( Hongyan and JinJie, 2010 ; Min, 2010 ).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome with no unified pathological or neurobiological etiology, which is characterized by difficulties in social interaction, communication problems, and a tendency to engage in repetitive behaviors ( Geschwind and Levitt, 2007 ).

Art therapy is a form of expression that opens the door to communication without verbal interaction. It provides therapists with the opportunity to interact one-on-one with individuals with autism, and make broad connections in a more comfortable and effective way ( Babaei et al., 2020 ). Emery (2004) did a case study about a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with autism and found that art therapy is of great value to the development, growth and communication skills of the boy. Recently, one study ( Jalambadani, 2020 ) using 40 children with ASD participating in painting therapy showed that painting therapy had a significant improvement in the social interactions, adaptive behaviors and emotions. Therefore, encouraging children with ASD to express their experience by using nonverbal expressions is crucial to their development. Evans and Dubowski (2001) believed that creating images on paper could help children express their internal images, thereby enhance their imagination and abstract thinking. Painting can also help autistic children express and vent negative emotions and thereby bring positive emotional experience and promote their self-consciousness ( Martin, 2009 ). According to two studies ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) in China, Art therapy could also improve the language and communication skills, cognitive and behavioral performance of children with ASD.

Moreover, art therapy could be used to investigate the relationship between cognitive processes and imagination in children with ASD. One study ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) suggested that children with ASD apply a unique cognitive strategy in imaginative drawing. Another study ( Low et al., 2009 ) examined the cognitive underpinnings of spontaneous imagination in children with ASD and showed that ASD group lacks imagination, generative ability, planning ability and good consistency in their drawings. In addition, several studies ( Leevers and Harris, 1998 ; Craig and Baron-Cohen, 1999 ; Craig et al., 2001 ) have been performed to investigate imagination and creativity of autism via drawing tasks, and showed impairments of autism in imagination and creativity via drawing tasks.

In a word, art therapy plays a significant role in children with ASD, not only as a method of treatment, but also in understanding and investigating patients’ problems.

Other Applications

In addition to the above mentioned diseases, art therapy has also been adopted in other applications. Dysarthia is a common sequela of cerebral palsy (CP), which directly affects children’s language intelligibility and psycho-social adjustment. Speech therapy does not always help CP children to speak more intelligibly. Interestingly, the art therapy can significantly improve the language intelligibility and their social skills for children with CP ( Wilk et al., 2010 ).

In brief, these studies suggest that art therapy is meaningful and accepted by both patients and therapists. Most often, art therapy could strengthen patient’s emotional expression, self-esteem, and self-awareness. However, our findings are based on relatively small samples and few good-quality qualitative studies, and require cautious interpretation.

The Application Prospects of Art Therapy

With the development of modern medical technology, life expectancy is also increasing. At the same time, it also brings some side effects and psychological problems during the treatment process, especially for patients with mental illness. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for finding appropriate complementary therapies to improve life quality of patients and psychological health. Art therapy is primarily offered as individual art therapy, in this review, we found that art therapy was most commonly used for depression and anxiety.

Based on the above findings, art therapy, as a non-verbal psychotherapy method, not only serves as an auxiliary tool for diagnosing diseases, which helps medical specialists obtain much information that is difficult to gain from conventional tests, judge the severity and progression of diseases, and understand patients’ psychological state from painting characteristics, but also is an useful therapeutic method, which helps patients open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences. Additionally, the implementation of art therapy is not limited by age, language, diseases or environment, and is easy to be accepted by patients.

Art therapy in hospitals and clinical settings could be very helpful to aid treatment and therapy, and to enhance communications between patients and on-site medical staffs in a non-verbal way. Moreover, art therapy could be more effective when combined with other forms of therapy such as music, dance and other sensory stimuli.

The medical mechanism underlying art therapy using painting as the medium for intervention remains largely unclear in the literature ( Salmon, 1993 ; Broadbent et al., 2004 ; Guillemin, 2004 ), and the evidence for effectiveness is insufficient ( Mirabella, 2015 ). Although a number of studies have shown that art therapy could improve the quality of life and mental health of patients, standard and rigorous clinical trials with large samples are still lacking. Moreover, the long-term effect is yet to be assessed due to the lack of follow-up assessment of art therapy.

In some cases, art therapy using painting as the medium may be difficult to be implemented in hospitals, due to medical and health regulations (may be partly due to potential of messes, lack of sink and cleaning space for proper disposal of paints, storage of paints, and toxins of allergens in the paint), insufficient space for the artwork to dry without getting in the way or getting damaged, and negative medical settings and family environments. Nevertheless, these difficulties can be overcome due to great benefits of the art therapy. We thus humbly believe that art therapy has great potential for mental disorders.

In the future, art therapy may be more thoroughly investigated in the following directions. First, more high-quality clinical trials should be carried out to gain more reliable and rigorous evidence. Second, the evaluation methods for the effectiveness of art therapy need to be as diverse as possible. It is necessary for the investigation to include not only subjective scale evaluations, but also objective means such as brain imaging and hematological examinations to be more convincing. Third, it will be helpful to specify the details of the art therapy and patients for objective comparisons, including types of diseases, painting methods, required qualifications of the therapist to perform the art therapy, and the theoretical basis and mechanism of the therapy. This practice should be continuously promoted in both hospitals and communities. Fourth, guidelines about art therapy should be gradually formed on the basis of accumulated evidence. Finally, mechanism of art therapy should be further investigated in a variety of ways, such as at the neurological, cellular, and molecular levels.

Author Contributions

JH designed the whole study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JZ searched for selected the studies. LH participated in the interpretation of data. HY and JX offered good suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1712200), International standards research on clinical research and service of Acupuncture-Moxibustion (2019YFC1712205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62006220), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Program (No. JCYJ20200109114816594).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., van Hooren, S., de Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., and Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 13:e208716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abdulah, D. M., and Abdulla, B. (2018). Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 41, 180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.020

Alvarenga, W. A., Leite, A., Oliveira, M. S., Nascimento, L. C., Silva-Rodrigues, F. M., Nunes, M. D. R., et al. (2018). The effect of music on the spirituality of patients: a systematic review. J. Holist. Nurs. 36, 192–204. doi: 10.1177/0898010117710855

American Art Therapy Association (2018). Definition of Art. Available online at: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/

Google Scholar

Andreasen, N. C., and Olsen, S. (1982). Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 789–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070025006

Armstrong, V. G., and Howatson, R. (2015). Parent-infant art psychotherapy: a creative dyadic approach to early intervention. Infant Ment. Health J. 36, 213–222. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21504

Attard, A., and Larkin, M. (2016). Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30146-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Babaei, S., Fatahi, B. S., Fakhri, M., Shahsavari, S., Parviz, A., Karbasfrushan, A., et al. (2020). Painting therapy versus anxiolytic premedication to reduce preoperative anxiety levels in children undergoing tonsillectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 88, 190–191. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03430-9

Bar-Sela, G., Atid, L., Danos, S., Gabay, N., and Epelbaum, R. (2007). Art therapy improved depression and influenced fatigue levels in cancer patients on chemotherapy. Psychooncology 16, 980–984. doi: 10.1002/pon.1175

Birgitta, G. A., Wagman, P., Hedin, K., and Håkansson, C. (2018). Treatment of depression and/or anxiety–outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of the tree theme method ® versus regular occupational therapy. BMC Psychol. 6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0237-0

British Association of Art Therapists (2015). What is Art Therapy? Available online at: https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy

Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Ellis, C. J., Ying, J., and Gamble, G. (2004). A picture of health–myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability: a longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 57, 583–587.

Burton, A. (2009). Bringing arts-based therapies in from the scientific cold. Lancet Neurol. 8, 784–785. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70216-9

Chiang, M., Reid-Varley, W. B., and Fan, X. (2019). Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 275, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.025

Ciasca, E. C., Ferreira, R. C., Santana, C.L. A., Forlenza, O. V., Dos Santos, G. D., Brum, P. S., et al. (2018). Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 40, 256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2250

Craig, J., and Baron-Cohen, S. (1999). Creativity and imagination in autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 319–326.

Craig, J., Baron-Cohen, S., and Scott, F. (2001). Drawing ability in autism: a window into the imagination. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 38, 242–253.

Cramer, V., Torgersen, S., and Kringlen, E. (2005). Quality of life and anxiety disorders: a population study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 193, 196–202. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154836.22687.13

Crone, D. M., O’Connell, E. E., Tyson, P. J., Clark-Stone, F., Opher, S., and James, D. V. (2013). ‘Art Lift’ intervention to improve mental well-being: an observational study from U.K. general practice. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 22, 279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00862.x

Cuijpers, P., Vogelzangs, N., Twisk, J., Kleiboer, A., Li, J., and Penninx, B. W. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 453–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325

De Sousa, A., Shah, B., and Shrivastava, A. (2020). Suicide and Schizophrenia: an interplay of factors. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22:65.

Demyttenaere, K., Bruffaerts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J. P., et al. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291, 2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

Deshmukh, S. R., Holmes, J., and Cardno, A. (2018). Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9:D11073.

Emery, M. J. (2004). Art therapy as an intervention for Autism. Art Ther. Assoc. 21, 143–147. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2004.10129500

Evans, K., and Dubowski, J. (2001). Art Therapy with Children on the Autistic Spectrum: Beyond Words. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 113.

Faller, H., and Schmidt, M. (2004). Prognostic value of depressive coping and depression in survival of lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 13, 359–363. doi: 10.1002/pon.783

Forouzandeh, N., Drees, F., Forouzandeh, M., and Darakhshandeh, S. (2020). The effect of interactive games compared to painting on preoperative anxiety in Iranian children: a randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 40:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101211

Forzoni, S., Perez, M., Martignetti, A., and Crispino, S. (2010). Art therapy with cancer patients during chemotherapy sessions: an analysis of the patients’ perception of helpfulness. Palliat. Support. Care 8, 41–48. doi: 10.1017/s1478951509990691

Geschwind, D. H., and Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: developmental disconnection syndromes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.009

Geue, K., Richter, R., Buttstädt, M., Brähler, E., and Singer, S. (2013). An art therapy intervention for cancer patients in the ambulant aftercare–results from a non-randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 22, 345–352. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12037

Götze, H., Geue, K., Buttstädt, M., Singer, S., and Schwarz, R. (2009). [Art therapy for cancer patients in outpatient care. Psychological distress and coping of the participants]. Forsch. Komplementmed. 16, 28–33.

Guillemin, M. (2004). Understanding illness: using drawings as a research method. Qual. Health Res. 14, 272–289. doi: 10.1177/1049732303260445

Gussak, D. (2007). The effectiveness of art therapy in reducing depression in prison populations. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 51, 444–460. doi: 10.1177/0306624x06294137

Hamer, M., Chida, Y., and Molloy, G. J. (2009). Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 66, 255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002

Hattori, H., Hattori, C., Hokao, C., Mizushima, K., and Mase, T. (2011). Controlled study on the cognitive and psychological effect of coloring and drawing in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 11, 431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00698.x

Heymann, P., Gienger, R., Hett, A., Müller, S., Laske, C., Robens, S., et al. (2018). Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on the patient’s creative drawing process: first results with a novel neuropsychological testing method. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63, 675–687. doi: 10.3233/jad-170946

Hongxia, M., Shuying, C., Chuqiao, F., Haiying, Z., Xuejiao, W., et al. (2013). Relationsle-title>Relationship between psychological state and house-tree-person drawing characteristics of rehabilitation patients with schizophrenia. Chin. Gen. Pract. 16, 2293–2295.

Relationship+between+psychological+state+and+house-tree-person+drawing+characteristics+of+rehabilitation+patients+with+schizophrenia%2E&journal=Chin%2E+Gen%2E+Pract%2E&author=Hongxia+M.&author=Shuying+C.&author=Chuqiao+F.&author=Haiying+Z.&author=Xuejiao+W.&publication_year=2013&volume=16&pages=2293–2295" target="_blank">Google Scholar

Hongyan, W., and JinJie, L. (2010). Rehabilitation effect of painting therapy on chronic schizophrenia. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 18, 1419–1420.

Jalambadani, Z. (2020). Art therapy based on painting therapy on the improvement of autistic children’s social interactions in Iran. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 218–219. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_215_18

Jianhua, C., and Xiaolu, X. (2013). The experimental research on children with autism by intervening with painting therapy. J. Tangshan Teach. Coll. 35, 127–130.

Kenbubpha, K., Higgins, I., Chan, S. W., and Wilson, A. (2018). Promoting active ageing in older people with mental disorders living in the community: an integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 24:e12624. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12624

Kolliakou, A., Joseph, C., Ismail, K., Atakan, Z., and Murray, R. M. (2011). Why do patients with psychosis use cannabis and are they ready to change their use? Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 29, 335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.11.006

Lee, J., Choi, M. Y., Kim, Y. B., Sun, J., Park, E. J., Kim, J. H., et al. (2017). Art therapy based on appreciation of famous paintings and its effect on distress among cancer patients. Qual. Life Res. 26, 707–715. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1473-5

Leevers, H. J., and Harris, P. L. (1998). Drawing impossible entities: a measure of the imagination in children with autism, children with learning disabilities, and normal 4-year-olds. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 39, 399–410. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00335

Lefèvre, C., Ledoux, M., and Filbet, M. (2016). Art therapy among palliative cancer patients: aesthetic dimensions and impacts on symptoms. Palliat. Support. Care 14, 376–380. doi: 10.1017/s1478951515001017

Legrand, A. P., Rivals, I., Richard, A., Apartis, E., Roze, E., Vidailhet, M., et al. (2017). New insight in spiral drawing analysis methods–application to action tremor quantification. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 1823–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.07.002

Liebmann, M., and Weston, S. (2015). Art Therapy with Physical Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lin, M. H., Moh, S. L., Kuo, Y. C., Wu, P. Y., Lin, C. L., Tsai, M. H., et al. (2012). Art therapy for terminal cancer patients in a hospice palliative care unit in Taiwan. Palliat. Support. Care 10, 51–57. doi: 10.1017/s1478951511000587

Low, J., Goddard, E., and Melser, J. (2009). Generativity and imagination in adisorder: evidence from individual differences in children’s impossible entity drawings. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 27, 425–444. doi: 10.1348/026151008x334728

Malchiodi, C. (2013). Art Therapy and Health Care. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Mannheim, E. G., Helmes, A., and Weis, J. (2013). [Dance/movement therapy in oncological rehabilitation]. Forsch. Komplementmed. 20, 33–41.

Martin, N. (2009). Art as an Early Intervention Tool for Children with Autism. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Mimica, N., and Kaliniæ, D. (2011). Art therapy may be benefitial for reducing stress–related behaviours in people with dementia–case report. Psychiatr. Danub. 23:125.

Min, J. (2010). Application of painting therapy in the rehabilitation period of schizophrenia. Med. J. Chin. Peoples Health 22, 2012–2014.

Mirabella, G. (2015). Is art therapy a reliable tool for rehabilitating people suffering from brain/mental diseases? J. Altern. Complement. Med. 21, 196–199. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0374

Montag, C., Haase, L., Seidel, D., Bayerl, M., Gallinat, J., Herrmann, U., et al. (2014). A pilot RCT of psychodynamic group art therapy for patients in acute psychotic episodes: feasibility, impact on symptoms and mentalising capacity. PLoS One 9:e112348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112348

Nainis, N., Paice, J. A., Ratner, J., Wirth, J. H., Lai, J., and Shott, S. (2006). Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 31, 162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.006

Narme, P., Tonini, A., Khatir, F., Schiaratura, L., Clément, S., and Samson, S. (2012). [Non pharmacological treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: comparison between musical and non-musical interventions]. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 10, 215–224. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2012.0343

Nielsen, S., Hageman, I., Petersen, A., Daniel, S. I. F., Lau, M., Winding, C., et al. (2019). Do emotion regulation, attentional control, and attachment style predict response to cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders?–An investigation in clinical settings. Psychother. Res. 29, 999–1009. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1425933

Papangelo, P., Pinzino, M., Pelagatti, S., Fabbri-Destro, M., and Narzisi, A. (2020). Human figure drawings in children with autism spectrum disorders: a possible window on the inner or the outer world. Brain Sci. 10:398. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060398

Petersen, R. C., Caracciolo, B., Brayne, C., Gauthier, S., Jelic, V., and Fratiglioni, L. (2014). Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J. Intern. Med. 275, 214–228.

Pike, A. A. (2013). The effect of art therapy on cognitive performance among ethnically diverse older adults. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 30, 159–168. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2014.847049

Pongan, E., Tillmann, B., Leveque, Y., Trombert, B., Getenet, J. C., Auguste, N., et al. (2017). Can musical or painting interventions improve chronic pain, mood, quality of life, and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. 60, 663–677. doi: 10.3233/jad-170410

Richardson, P., Jones, K., Evans, C., Stevens, P., and Rowe, A. (2007). Exploratory RCT of art therapy as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia. J. Ment. Health 16, 483–491. doi: 10.1080/09638230701483111

Richardson, P., Jones, K., Evans, C., Stevens, P., and Rowe, A. (2009). Exploratory RCT of art therapy as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia. J Ment. Health 16, 483–491.

Ruiz, M. I., Aceituno, D., and Rada, G. (2017). Art therapy for schizophrenia? Medwave 17:e6845.

Runde, P. (2008). Clinical application of painting therapy in middle school students with mood disorders. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 27, 749–750.

Rusted, J., Sheppard, L., and Waller, D. A. (2016). Multi-centre randomized control group trial on the use of art therapy for older people with dementia. Group Anal. 39, 517–536. doi: 10.1177/0533316406071447

Salmon, P. L. (1993). Viewing the client’s world through drawings. J. Holist. Nurs. 11, 21–41. doi: 10.1177/089801019301100104

Steinbauer, M., and Taucher, J. (2001). [Paintings and their progress by psychiatric inpatients within the concept of integrative art therapy]. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 151, 375–379.

Steinbauer, M., Taucher, J., and Zapotoczky, H. G. (1999). [Integrative painting therapy. A therapeutic concept for psychiatric inpatients at the University clinic in Graz]. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 111, 525–532.

Teglbjaerg, H. S. (2011). Art therapy may reduce psychopathology in schizophrenia by strengthening the patients’ sense of self: a qualitative extended case report. Psychopathology 44, 314–318. doi: 10.1159/000325025

Ten, E. K., and Muller, U. (2018). Drawing links between the autism cognitive profile and imagination: executive function and processing bias in imaginative drawings by children with and without autism. Autism 22, 149–160. doi: 10.1177/1362361316668293

Thyme, K. E., Sundin, E. C., Wiberg, B., Oster, I., Aström, S., and Lindh, J. (2009). Individual brief art therapy can be helpful for women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled clinical study. Palliat. Support. Care 7, 87–95. doi: 10.1017/s147895150900011x

Tong, J., Yu, W., Fan, X., Sun, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Impact of group art therapy using traditional Chinese materials on self-efficacy and social function for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Front. Psychol. 11:571124. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.571124

van Geffen, E. C., van der Wal, S. W., van Hulten, R., de Groot, M. C., Egberts, A. C., and Heerdink, E. R. (2007). Evaluation of patients’ experiences with antidepressants reported by means of a medicine reporting system. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63, 1193–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0375-4

Wang, Y., Jiepeng, L., Aihua, Z., Runjuan, M., and Lei, Z. (2011). Study on the application value of painting therapy in the treatment of depression. Med. J. Chin. Peoples Health 23, 1974–1976.

Wen, Z., and Zhaoming, G. (2009). A preliminary attempt of painting art therapy for autistic children. Inner Mongol. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 28, 24–25.

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., et al. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 382, 1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61611-6

Wilk, M., Pachalska, M., Lipowska, M., Herman-Sucharska, I., Makarowski, R., Mirski, A., et al. (2010). Speech intelligibility in cerebral palsy children attending an art therapy program. Med. Sci. Monit. 16, R222–R231.

Witkoski, S. A., and Chaves, M. (2007). Evaluation of artwork produced by Alzheimer’s disease outpatients in a pilot art therapy program. Dement. Neuropsychol. 1, 217–221. doi: 10.1590/s1980-57642008dn10200016

Xu, G., Chen, G., Zhou, Q., Li, N., and Zheng, X. (2017). Prevalence of mental disorders among older Chinese people in Tianjin City. Can. J. Psychiatry 62, 778–786. doi: 10.1177/0706743717727241

Yu, J., Rawtaer, I., Goh, L. G., Kumar, A. P., Feng, L., Kua, E. H., et al. (2021). The art of remediating age-related cognitive decline: art therapy enhances cognition and increases cortical thickness in mild cognitive impairment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 27, 79–88. doi: 10.1017/s1355617720000697

Zhenhai, N., and Yunhua, C. (2011). An experimental study on the improvement of depression in Obese female college students by painting therapy. Chin. J. Sch. Health 32, 558–559.

Zschucke, E., Gaudlitz, K., and Strohle, A. (2013). Exercise and physical activity in mental disorders: clinical and experimental evidence. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 46(Suppl. 1) S12–S21.

Keywords : painting, art therapy, mental disorders, clinical applications, medical interventions

Citation: Hu J, Zhang J, Hu L, Yu H and Xu J (2021) Art Therapy: A Complementary Treatment for Mental Disorders. Front. Psychol. 12:686005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.686005

Received: 26 March 2021; Accepted: 28 July 2021; Published: 12 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Hu, Zhang, Hu, Yu and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinping Xu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Lost for words? Research shows art therapy brings benefits for mental health

Academic, Master of Art Therapy Program, Western Sydney University

Senior Lecturer, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, UNSW Sydney

Disclosure statement

Sarah Versitano is a PhD Candidate at Western Sydney University and works for the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, which is part of NSW Health. She has received funding from the Health Education and Training Institute (HETI) for the Mental Health Research Award. She is a Registered Art Therapist with the Australia, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association (ANZACATA) and Registered Clinical Counsellor with the Psychotherapists and Counsellors Federation of Australia (PACFA). She has delivered art therapy and psychotherapy in public and private hospital settings.

Iain Perkes works for the University of New South Wales and the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network which is part of NSW Health. He has previously worked for numerous health services throughout NSW Health. He has received funding or awards from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the International Association of Child and Adolescent and Allied Professions, (IACAPAP), the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), the Tourette's Association of America (TAA), Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA), the NSW Institute of Psychiatry, The University of Sydney, and the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE). He is affiliated with Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) and the Health Education and Training Institute (HETI, NSW Health).

Western Sydney University and UNSW Sydney provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Creating art for healing purposes dates back tens of thousands of years , to the practices of First Nations people around the world. Art therapy uses creative processes, primarily visual art such as painting, drawing or sculpture, with a view to improving physical health and emotional wellbeing .

When people face significant physical or mental ill-health, it can be challenging to put their experiences into words . Art therapists support people to explore and process overwhelming thoughts, feelings and experiences through a reflective art-making process. This is distinct from art classes , which often focus on technical aspects of the artwork, or the aesthetics of the final product.

Art therapy can be used to support treatment for a wide range of physical and mental health conditions. It has been linked to benefits including improved self-awareness, social connection and emotional regulation, while lowering levels of distress, anxiety and even pain scores.

In a study published this week in the Journal of Mental Health , we found art therapy was associated with positive outcomes for children and adolescents in a hospital-based mental health unit.

An option for those who can’t find the words

While a person’s engagement in talk therapies may sometimes be affected by the nature of their illness, verbal reflection is optional in art therapy.

Where possible, after finishing an artwork, a person can explore the meaning of their work with the art therapist, translating unspoken symbolic material into verbal reflection.

However, as the talking component is less central to the therapeutic process, art therapy is an accessible option for people who may not be able to find the words to describe their experiences.

Read more: Creative arts therapies can help people with dementia socialise and express their grief

Art therapy has supported improved mental health outcomes for people who have experienced trauma , people with eating disorders , schizophrenia and dementia , as well as children with autism .

Art therapy has also been linked to improved outcomes for people with a range of physical health conditions . These include lower levels of anxiety, depression and fatigue among people with cancer , enhanced psychological stability for patients with heart disease , and improved social connection among people who have experienced a traumatic brain injury .

Art therapy has been associated with improved mood and anxiety levels for patients in hospital , and lower pain, tiredness and depression among palliative care patients .

Our research

Mental ill-health, including among children and young people , presents a major challenge for our society. While most care takes place in the community , a small proportion of young people require care in hospital to ensure their safety.

In this environment, practices that place even greater restriction, such as seclusion or physical restraint, may be used briefly as a last resort to ensure immediate physical safety. However, these “restrictive practices” are associated with negative effects such as post-traumatic stress for patients and health professionals .

Worryingly, staff report a lack of alternatives to keep patients safe . However, the elimination of restrictive practices is a major aim of mental health services in Australia and internationally.

Read more: 'An arts engagement that's changed their life': the magic of arts and health

Our research looked at more than six years of data from a child and adolescent mental health hospital ward in Australia. We sought to determine whether there was a reduction in restrictive practices during the periods when art therapy was offered on the unit, compared to times when it was absent.

We found a clear association between the provision of art therapy and reduced frequency of seclusion, physical restraint and injection of sedatives on the unit.

We don’t know the precise reason for this. However, art therapy may have lessened levels of severe distress among patients, thereby reducing the risk they would harm themselves or others, and the likelihood of staff using restrictive practices to prevent this.

That said, hospital admission involves multiple therapeutic interventions including talk-based therapies and medications. Confirming the effect of a therapeutic intervention requires controlled clinical trials where people are randomly assigned one treatment or another.

Although ours was an observational study, randomised controlled trials support the benefits of art therapy in youth mental health services. For instance, a 2011 hospital-based study showed reduced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among adolescents randomised to trauma-focussed art therapy compared to a “control” arts and crafts group.

What do young people think?

In previous research we found art therapy was considered by adolescents in hospital-based mental health care to be the most helpful group therapy intervention compared to other talk-based therapy groups and creative activities.

In research not yet published, we’re speaking with young people to better understand their experiences of art therapy, and why it might reduce distress. One young person accessing art therapy in an acute mental health service shared:

[Art therapy] is a way of sort of letting out your emotions in a way that doesn’t involve being judged […] It let me release a lot of stuff that was bottling up and stuff that I couldn’t explain through words.

A promising area

The burgeoning research showing the benefits of art therapy for both physical and especially mental health highlights the value of creative and innovative approaches to treatment in health care .

There are opportunities to expand art therapy services in a range of health-care settings. Doing so would enable greater access to art therapy for people with a variety of physical and mental health conditions.

- Mental health

- Mental illness

- Art therapy

- Youth mental health

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Strategy Implementation Manager

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Art Therapy

2022, Longer-Term Psychiatric Inpatient Care for Adolescents

Related Papers

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy

Fran Nielsen

Frontiers in Psychology

Susan Van Hooren

Art Therapy Online

Frances Nielsen

Einat Metzl

This paper explores the current theoretical frames of working with children and adolescents, considers the socio-political and developmental considerations for art therapy practice within settings, and systems in which children are embedded. An illustration of the use of art materials, processes, and products for children and adolescents based on an art therapist’s clinical experience in school settings, mental health hospital, adolescents’ clinic, and private practice then follows.

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -)

Aisling Mulligan

Art therapy and art psychotherapy are often offered in Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS). We aimed to review the evidence regarding art therapy and art psychotherapy in children attending mental health services. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO (CINHAL®Complete) following PRISMA guidelines, using the search terms (“creative therapy” OR “art therapy”) AND (child* OR adolescent OR teen*). We excluded review articles, articles which included adults, articles which were not written in English and articles without outcome measures. We identified 17 articles which are included in our review synthesis. We described these in two groups—ten articles regarding the treatment of children with a psychiatric diagnosis and seven regarding the treatment of children with psychiatric symptoms, but no formal diagnosis. The studies varied in terms of the type of art therapy/psychotherapy delivered, underlying conditions and outcome measures. Many were case studies/case se...

The Valuable Role of Child Art Psychotherapy

Anne Coffey

CHILD ART PSYCHOTHERAPY (CAP) is a form of psychotherapy that uses the medium of art, which can be helpful to children and young people in communicating difficult issues verbally. It is an effective short-term, early intervention, treating young people experiencing mild to moderate mental health issues. Little has been published on the role and value of Child Art Psychotherapy in primary care in Ireland. Many GPs are unaware of the profession and its success as a treatment. GPs have identified a greater need for short-term, focused counselling services to meet the needs of young people in their communities. This Authors propose implementing the CAP method with young people presenting with mental health issues to CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) and in private practice, suggesting that some cases could be treated earlier within primary care, if access to child art psychotherapy supports is available.

Elaina E Yip

When children who have suffered trauma require a therapeutic approach in order to heal, are the conventional means of therapy such as talk therapy really the right approach? One of the more daunting aspects of treating patients - especially children - who have faced trauma is that the sensory information and experiences related to the traumatic memory does not dissipate as time goes on; in fact, the trauma continues to be re-experienced. This paper aims to investigate art therapies effectiveness in treating children who have faced such trauma and discusses the psychological effects of art therapy on processing trauma.

BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience

Ganna Ganna

The article considers art-therapeutic means for adults and children during the war. The relevance of the article is to help children and adults to use art therapy to develop vitality, psycho-emotional recovery, adaptation to new social conditions, the formation of emotional and volitional self-regulation of behavior. Objective of the article: to find out the essence of art therapy; to study the consequences of adults and children during wars; consider popular art-therapeutic techniques for the treatment of psychological disorders in victims. Methods: analysis of scientific literature, system analysis. Results: According to research on this issue, art therapies are extremely useful and necessary for the treatment of adults and children affected by war. The consequences of adults and children during wars have been studied. The advantages of using art therapy are highlighted. In addition, popular art-therapeutic techniques for the treatment of psychological disorders in victims are con...

Ana Gachero

In researching the effectiveness of the use of Art Therapy with victims of sexual abuse, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in war veterans and its efficacy when used to treat elderly isolation and loneliness, a great amount of research has not yet been conducted, which could primarily be due to the small number of trained Art Therapists as well as Art Therapists willing to conduct research and quantitative studies in the area of Art and Healing, specifically with adults. The extent of much of the research already conducted using art therapy, has been done mostly with children. Some studies were conducted to evaluate efficacy of using art as a way toward promoting mental well-being, however, many were done outside of the United States with few although significant; within the U.S.. Art when used as therapy in non-clinical as well as clinical settings serves to support mental health recovery of clients who have been victims of trauma stemming from varying levels of abuse or catastrophic events as well as people suffering the effects of loneliness and isolation.

RELATED PAPERS

Alpeshh Vaghasiya

Lupita Rodriguez

… European Conference on …

Gábor Prószéky

International Journal of Modern Physics D

Joan Solà Peracaula

Egészségfejlesztés folyóirat

Judit Schmidt

Journal of Thermal Spray Technology

Tomasz Kiełczawa

Journal of Clinical Microbiology

Neluka Fernando

International Journal of Culture and Mental Health

Sigrid James

Alicia Gil Torres

Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences - Section A

D. P. Burte

Acta Paediatrica

Daniel Rodrigues Pereira

Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics

Randy Little

Research, Society and Development

Layse Furtado

Kamar Shah Ariffin

2017 European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC)

Revista Información Científica

Tidsskriftet Antropologi

Lebanon Quarterly Update

Omar Razzaz

Dil Eğitimi ve Araştırmaları Dergisi

Meltem Ercanlar

International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences

Durgesh Kumar

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry

Seema Bhargava

Journal of Economics & Management Strategy

B. Douglas Bernheim

hjhjgfg freghrf

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

What Creative Arts Therapies Teach Us About DBT Skills Training

Bridging dbt with the arts for deeper understanding..

Posted April 15, 2024 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- What Is Therapy?

- Find a therapist near me

- Research supports the effectiveness of combining DBT with creative arts to improve outcomes.

- Facilitators can teach wise-mind skills through drama therapy techniques.

- Action-based DBT utilizes storytelling and role-play to make skill learning more accessible and impactful.

In the ever-evolving realm of mental health, therapists are always exploring new and innovative methods to enhance traditional treatments. Creative arts therapists have led the way in utilizing art-based interventions to teach DBT skills.

Creative arts therapy combines visual arts, movement, drama, music, writing, and other creative processes to support clients in their healing process. Many mental health clinicians have embraced creative arts therapy interventions to improve their clients' health and wellness.

There is a growing body of research that indicates that therapists can utilize creative interventions to help clients learn and generalize DBT skills. In this post, I will provide a brief literature review of therapists who have been doing this integrative work and provide an example of how drama therapy can be utilized to teach the DBT skill of wise mind.

DBT and Art Therapy

Research indicates that integrating art therapy into established psychotherapy forms, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, can have significant positive effects on client well-being. For example, a study by Monti et al. (2012) demonstrated the potential of mindfulness -based art therapy (MBAT) in alleviating emotional distress, highlighting the power of combining art therapy with the core feature of mindfulness in DBT. Though this study did not specifically discuss DBT, it demonstrated that implementing mindfulness, a core component of DBT, can assist individuals who are facing significant physical and emotional stressors.

Building on research that examined mindfulness and art therapy, several practitioners have contributed articles that specifically address the integration of DBT and art therapy within clinical populations. For example, researchers Huckvale and Learmonth (2009) led the charge by developing a new and innovative art therapy approach grounded in DBT for patients facing mental health challenges. Furthermore, Heckwolf, Bergland, and Mouratidis (2014) demonstrated how visual art and integrative treatments could help clients access DBT, resulting in stronger generalization and implementation of these skills outside of the session. The clinicians concluded that this integrative approach to treatment could reinforce skills, contribute to interdisciplinary team synergy, and enact bilateral integration.

Other notable examples from art therapists include Susan Clark’s (2017) DBT-informed art therapy, a strategic approach to treatment that incorporates creative visual exercises to explore, practice, and generalize DBT concepts and skills.

Expanding Beyond Visual Art Therapy

DBT has now been integrated with other expressive art therapies, including drama and music. Art therapists Karin von Daler and Lori Schwanbeck (2014) were instrumental in this expansion when they developed Creative Mindfulness, an approach to therapy integrating various expressive arts therapies with DBT. Creative Mindfulness “suggests a way of working therapeutically that is as containing and structured as DBT and as creative, embodied, and multi-sensory as expressive arts” (p. 235). These clinicians incorporated improvisation into their work, a tool that can be simultaneously playful, experiential, and grounding, ultimately producing substantial new insights for clients.

Moreover, music and drama therapists have recognized the benefits of multisensory skill teaching, expanding the creative techniques used to teach DBT skills ( Deborah Spiegel, 2020 ; Nicky Morris, 2018 , and Roohan and Trottier, 2021 ).

My Own Experience Integrating Drama Therapy and DBT

Personally, I am a big advocate of both dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and drama therapy. In fact, I love these modalities so much that I dedicated not only my master's thesis but also my dissertation to better understanding how to reinforce DBT skills through dramatic techniques. In the process, I developed a new approach called Action-Based DBT that uses dramatic interventions like storytelling, embodiment, and role-playing to create a supportive environment for participants to learn skills in a more personalized and embodied way. An expert panel review demonstrated that this format can effectively support skill learning, especially for clients who struggle with the standard format of DBT skills training. Additionally, mental health clinicians found the program easily adaptable across populations in both individual and group settings.

Embodying the Mind States

To illustrate this approach and its effectiveness, the following is an example of how drama therapy methods can teach the DBT skill of wise mind within the context of an action-based DBT group.

The facilitator begins the group session by reviewing general guidelines and introducing the targeted DBT skill for the day: wise mind. The group then participates in improvisational warm-up activities to promote creativity , positive social interaction, and group connectivity. Following the warm-up, the facilitator distributes the DBT mind states handout (Linehan, 2015) and provides brief psychoeducation on this skill. Three chairs are placed in the front of the group room, facing the semi-circle of clients. Each chair had a piece of colored construction paper taped to the front, reading as Reasonable, Wise and Emotion . The facilitator explains that each chair represents one of the three mind states: reasonable mind, emotion mind and wise mind. To encourage exploration of the mind states, the facilitator can assign a more specific role to each state of mind. For example, the reasonable mind is The Computer, the emotion mind is The Tornado, and the wise mind is The Sage. Group members are invited to think of a scenario in which they felt they had difficulty accessing their wise mind. Clients then take turns embodying each mind state by sitting in the chair and speaking from the respective role. When a client first sits in a chair, the facilitator aids in enrolling the individual by asking questions about the role (i.e. The Computer, The Tornado, The Sage). For example, the facilitator may ask about the posture, tone of voice, or a “catchphrase” for this role. The client then embodies the role and responds to questions from the group as the specific mind state. After the embodiment, clients engage in verbal processing. The wise mind directive supports clients in developing kinaesthetic awareness of the three mind states. Embodying these mind states within the context of a supportive group and engaging in verbal processing around the experience can increase awareness of the mind states, which is helpful for clients who are trying to understand their emotional response to lived events outside of the group setting.

The creative arts therapies offer a dynamic pathway to teaching and reinforcing DBT skills. Incorporating visual art, drama, or music in the process of learning DBT skills allows clients to engage with these concepts in a multisensory and embodied way.

In my personal experience, weaving drama therapy techniques into DBT skills training has proven to be profoundly impactful. The Action-Based DBT approach, with its emphasis on storytelling and embodiment, offers an immersive and experiential learning environment that can be especially beneficial for those who find traditional methods challenging.

Looking ahead, my next post will delve into how storytelling can be harnessed to teach DBT skills in a way that is both engaging and memorable.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory .

Clark, S. M. (2017). DBT-informed art therapy: Mindfulness, cognitive behavior therapy, and the creative process. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Heckwolf, J. I., Bergland, M. C., & Mouratidis, M. (2014). Coordinating principles of art therapy and DBT. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(4), 329-335.

Huckvale, K., & Learmonth, M. (2009). A case example of art therapy in relation to dialectical behaviour therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 14(2), 52-63.

Monti, D. A., Kash, K. M., Kunkel, E. J., Brainard, G., Wintering, N., Moss, A. S., Rao, H., Zhu, S., & Newberg, A. B. (2012). Changes in cerebral blood flow and anxiety associated with an 8-week mindfulness programme in women with breast cancer. Stress and Health, 28(5), 397-407.

Morris, N. (2018). Dramatherapy for borderline personality disorder: Empowering and nurturing people through creativity. Routledge.

Roohan Mary Kate, Trottier Dana George. (2021) Action-based DBT: Integrating drama therapy to access wise mind. Drama Therapy Review, 7 (2), 193 https://doi.org/10.1386/dtr_00073_1

Spiegel, D., Makary, S., & Bonavitacola, L. (2020). Creative DBT activities using music: Interventions for enhancing engagement and effectiveness in therapy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Von Daler, K., and Schwanbeck, L. (2014). Creative mindfulness: Dialectical behavior therapy and expressive arts therapy. In L. Rappaport (Ed.), Mindfulness and the arts therapies: Theory and practice (pp. 107-116). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Mary Kate Roohan, Psy.D., is a licensed psychologist and drama therapist and the founder of Thrive and Feel, a therapy practice that supports clients in managing emotional sensitivity.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Research Paper Example

Art Therapy Research Papers Samples For Students

4 samples of this type

If you're looking for a workable method to simplify writing a Research Paper about Art Therapy, WowEssays.com paper writing service just might be able to help you out.

For starters, you should skim our large directory of free samples that cover most diverse Art Therapy Research Paper topics and showcase the best academic writing practices. Once you feel that you've figured out the key principles of content presentation and drawn actionable ideas from these expertly written Research Paper samples, putting together your own academic work should go much easier.

However, you might still find yourself in a circumstance when even using top-notch Art Therapy Research Papers doesn't allow you get the job done on time. In that case, you can contact our experts and ask them to craft a unique Art Therapy paper according to your individual specifications. Buy college research paper or essay now!

Interventions In Group Therapy For Pstd Research Paper Examples

Group interventions in pstd treatment.

Group interventions in PSTD are preferred to individual treatments due to the benefits of group therapy. The group environment provides safety, cohesion and empathy. The individuals get an opportunity to form trusting relationships. There is no single treatment strategy of the condition due to the nature of its complexity. There are four main group interventions known as cognitive behavioural therapy, psychodynamic therapy, art therapy and psychological debriefing. Cognitive behaviour therapy which involves exposure and stress inoculation therapy has been proven to be quite effective. It is used to treat fear and cognitive distortions. It is a lengthy and intensive treatment.

Good Research Paper On Human Trafficking In The United States

Research paper on borderline personality disorder, borderline personality disorder.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your research paper done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Influences Of Artists On Human Mind Research Paper Examples

[Author][Date][Course][Instructor]

Introduction

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!