- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Reading Research Effectively

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Reading a Scholarly Article or Research Paper

Identifying a research problem to investigate usually requires a preliminary search for and critical review of the literature in order to gain an understanding about how scholars have examined a topic. Scholars rarely structure research studies in a way that can be followed like a story; they are complex and detail-intensive and often written in a descriptive and conclusive narrative form. However, in the social and behavioral sciences, journal articles and stand-alone research reports are generally organized in a consistent format that makes it easier to compare and contrast studies and to interpret their contents.

General Reading Strategies

W hen you first read an article or research paper, focus on asking specific questions about each section. This strategy can help with overall comprehension and with understanding how the content relates [or does not relate] to the problem you want to investigate. As you review more and more studies, the process of understanding and critically evaluating the research will become easier because the content of what you review will begin to coalescence around common themes and patterns of analysis. Below are recommendations on how to read each section of a research paper effectively. Note that the sections to read are out of order from how you will find them organized in a journal article or research paper.

1. Abstract

The abstract summarizes the background, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions of a scholarly article or research paper. Use the abstract to filter out sources that may have appeared useful when you began searching for information but, in reality, are not relevant. Questions to consider when reading the abstract are:

- Is this study related to my question or area of research?

- What is this study about and why is it being done ?

- What is the working hypothesis or underlying thesis?

- What is the primary finding of the study?

- Are there words or terminology that I can use to either narrow or broaden the parameters of my search for more information?

2. Introduction

If, after reading the abstract, you believe the paper may be useful, focus on examining the research problem and identifying the questions the author is trying to address. This information is usually located within the first few paragraphs of the introduction or in the concluding paragraph. Look for information about how and in what way this relates to what you are investigating. In addition to the research problem, the introduction should provide the main argument and theoretical framework of the study and, in the last paragraphs of the introduction, describe what the author(s) intend to accomplish. Questions to consider when reading the introduction include:

- What is this study trying to prove or disprove?

- What is the author(s) trying to test or demonstrate?

- What do we already know about this topic and what gaps does this study try to fill or contribute a new understanding to the research problem?

- Why should I care about what is being investigated?

- Will this study tell me anything new related to the research problem I am investigating?

3. Literature Review

The literature review describes and critically evaluates what is already known about a topic. Read the literature review to obtain a big picture perspective about how the topic has been studied and to begin the process of seeing where your potential study fits within the domain of prior research. Questions to consider when reading the literature review include:

- W hat other research has been conducted about this topic and what are the main themes that have emerged?

- What does prior research reveal about what is already known about the topic and what remains to be discovered?

- What have been the most important past findings about the research problem?

- How has prior research led the author(s) to conduct this particular study?

- Is there any prior research that is unique or groundbreaking?

- Are there any studies I could use as a model for designing and organizing my own study?

4. Discussion/Conclusion

The discussion and conclusion are usually the last two sections of text in a scholarly article or research report. They reveal how the author(s) interpreted the findings of their research and presented recommendations or courses of action based on those findings. Often in the conclusion, the author(s) highlight recommendations for further research that can be used to develop your own study. Questions to consider when reading the discussion and conclusion sections include:

- What is the overall meaning of the study and why is this important? [i.e., how have the author(s) addressed the " So What? " question].

- What do you find to be the most important ways that the findings have been interpreted?

- What are the weaknesses in their argument?

- Do you believe conclusions about the significance of the study and its findings are valid?

- What limitations of the study do the author(s) describe and how might this help formulate my own research?

- Does the conclusion contain any recommendations for future research?

5. Methods/Methodology

The methods section describes the materials, techniques, and procedures for gathering information used to examine the research problem. If what you have read so far closely supports your understanding of the topic, then move on to examining how the author(s) gathered information during the research process. Questions to consider when reading the methods section include:

- Did the study use qualitative [based on interviews, observations, content analysis], quantitative [based on statistical analysis], or a mixed-methods approach to examining the research problem?

- What was the type of information or data used?

- Could this method of analysis be repeated and can I adopt the same approach?

- Is enough information available to repeat the study or should new data be found to expand or improve understanding of the research problem?

6. Results

After reading the above sections, you should have a clear understanding of the general findings of the study. Therefore, read the results section to identify how key findings were discussed in relation to the research problem. If any non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts, tables, etc.] are confusing, focus on the explanations about them in the text. Questions to consider when reading the results section include:

- W hat did the author(s) find and how did they find it?

- Does the author(s) highlight any findings as most significant?

- Are the results presented in a factual and unbiased way?

- Does the analysis of results in the discussion section agree with how the results are presented?

- Is all the data present and did the author(s) adequately address gaps?

- What conclusions do you formulate from this data and does it match with the author's conclusions?

7. References

The references list the sources used by the author(s) to document what prior research and information was used when conducting the study. After reviewing the article or research paper, use the references to identify additional sources of information on the topic and to examine critically how these sources supported the overall research agenda. Questions to consider when reading the references include:

- Do the sources cited by the author(s) reflect a diversity of disciplinary viewpoints, i.e., are the sources all from a particular field of study or do the sources reflect multiple areas of study?

- Are there any unique or interesting sources that could be incorporated into my study?

- What other authors are respected in this field, i.e., who has multiple works cited or is cited most often by others?

- What other research should I review to clarify any remaining issues or that I need more information about?

NOTE : A final strategy in reviewing research is to copy and paste the title of the source [journal article, book, research report] into Google Scholar . If it appears, look for a "cited by" followed by a hyperlinked number [e.g., Cited by 45]. This number indicates how many times the study has been subsequently cited in other, more recently published works. This strategy, known as citation tracking, can be an effective means of expanding your review of pertinent literature based on a study you have found useful and how scholars have cited it. The same strategies described above can be applied to reading articles you find in the list of cited by references.

Reading Tip

Specific Reading Strategies

Effectively reading scholarly research is an acquired skill that involves attention to detail and an ability to comprehend complex ideas, data, and theoretical concepts in a way that applies logically to the research problem you are investigating. Here are some specific reading strategies to consider.

As You are Reading

- Focus on information that is most relevant to the research problem; skim over the other parts.

- As noted above, read content out of order! This isn't a novel; you want to start with the spoiler to quickly assess the relevance of the study.

- Think critically about what you read and seek to build your own arguments; not everything may be entirely valid, examined effectively, or thoroughly investigated.

- Look up the definitions of unfamiliar words, concepts, or terminology. A good scholarly source is Credo Reference .

Taking notes as you read will save time when you go back to examine your sources. Here are some suggestions:

- Mark or highlight important text as you read [e.g., you can use the highlight text feature in a PDF document]

- Take notes in the margins [e.g., Adobe Reader offers pop-up sticky notes].

- Highlight important quotations; consider using different colors to differentiate between quotes and other types of important text.

- Summarize key points about the study at the end of the paper. To save time, these can be in the form of a concise bulleted list of statements [e.g., intro has provides historical background; lit review has important sources; good conclusions].

Write down thoughts that come to mind that may help clarify your understanding of the research problem. Here are some examples of questions to ask yourself:

- Do I understand all of the terminology and key concepts?

- Do I understand the parts of this study most relevant to my topic?

- What specific problem does the research address and why is it important?

- Are there any issues or perspectives the author(s) did not consider?

- Do I have any reason to question the validity or reliability of this research?

- How do the findings relate to my research interests and to other works which I have read?

Adapted from text originally created by Holly Burt, Behavioral Sciences Librarian, USC Libraries, April 2018.

Another Reading Tip

When is it Important to Read the Entire Article or Research Paper

Laubepin argues, "Very few articles in a field are so important that every word needs to be read carefully." However, this implies that some studies are worth reading carefully. As painful and time-consuming as it may seem, there are valid reasons for reading a study in its entirety from beginning to end. Here are some examples:

- Studies Published Very Recently . The author(s) of a recent, well written study will provide a survey of the most important or impactful prior research in the literature review section. This can establish an understanding of how scholars in the past addressed the research problem. In addition, the most recently published sources will highlight what is currently known and what gaps in understanding currently exist about a topic, usually in the form of the need for further research in the conclusion .

- Surveys of the Research Problem . Some papers provide a comprehensive analytical overview of the research problem. Reading this type of study can help you understand underlying issues and discover why scholars have chosen to investigate the topic. This is particularly important if the study was published very recently because the author(s) should cite all or most of the key prior research on the topic. Note that, if it is a long-standing problem, there may be studies that specifically review the literature to identify gaps that remain. These studies often include the word review in their title [e.g., Hügel, Stephan, and Anna R. Davies. "Public Participation, Engagement, and Climate Change Adaptation: A Review of the Research Literature." Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 11 (July-August 2020): https://doi.org/10.1002/ wcc.645].

- Highly Cited . If you keep coming across the same citation to a study while you are reviewing the literature, this implies it was foundational in establishing an understanding of the research problem or the study had a significant impact within the literature [positive or negative]. Carefully reading a highly cited source can help you understand how the topic emerged and motivated scholars to further investigate the problem. It also could be a study you need to cite as foundational in your own paper to demonstrate to the reader that you understand the roots of the problem.

- Historical Overview . Knowing the historical background of a research problem may not be the focus of your analysis. Nevertheless, carefully reading a study that provides a thorough description and analysis of the history behind an event, issue, or phenomenon can add important context to understanding the topic and what aspect of the problem you may want to examine further.

- Innovative Methodological Design . Some studies are significant and worth reading in their entirety because the author(s) designed a unique or innovative approach to researching the problem. This may justify reading the entire study because it can motivate you to think creatively about pursuing an alternative or non-traditional approach to examining your topic of interest. These types of studies are generally easy to identify because they are often cited in others works because of their unique approach to studying the research problem.

- Cross-disciplinary Approach . R eviewing studies produced outside of your discipline is an essential component of investigating research problems in the social and behavioral sciences. Consider reading a study that was conducted by author(s) based in a different discipline [e.g., an anthropologist studying political cultures; a study of hiring practices in companies published in a sociology journal]. This approach can generate a new understanding or a unique perspective about the topic . If you are not sure how to search for studies published in a discipline outside of your major or of the course you are taking, contact a librarian for assistance.

Laubepin, Frederique. How to Read (and Understand) a Social Science Journal Article . Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ISPSR), 2013; Shon, Phillip Chong Ho. How to Read Journal Articles in the Social Sciences: A Very Practical Guide for Students . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015; Lockhart, Tara, and Mary Soliday. "The Critical Place of Reading in Writing Transfer (and Beyond): A Report of Student Experiences." Pedagogy 16 (2016): 23-37; Maguire, Moira, Ann Everitt Reynolds, and Brid Delahunt. "Reading to Be: The Role of Academic Reading in Emergent Academic and Professional Student Identities." Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 17 (2020): 5-12.

- << Previous: 1. Choosing a Research Problem

- Next: Narrowing a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: What is Research and Research Writing?

Write here, write now.

Developing your skills as a writer will make you more successful in ALL of your classes. Knowing how to think critically, organize your ideas, be concise, ask questions, perform research and back up your claims with evidence is key to almost everything you will do at university.

Writing is life

Solid writing skills will help you wow your family and friends with your well-articulated ideas, ace job interviews, build confidence in yourself, and feel part of a community of writers.

Beyond University

Whether you go on to graduate school, teach, work for the government or a non-profit, start your own business or your own heavy metal band, becoming a stronger writer will give you a solid foundation you can keep building on.

This chapter:

- Defines research and gives examples

- Describes the writing process

- Introduces writing using research

- Introduces simple research writing

- Prompts you to think about research and writing meaningful to you

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass : Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants . Milkweed Editions, 2013.

From “ Why Writing Matters “ . Writing Place: A Scholarly Writing Textbook by Lindsay Cuff. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. 2023.

Reading and Writing Research for Undergraduates Copyright © 2023 by Stephanie Ojeda Ponce is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

PALNI Information Literacy Modules

- PALNI Modules

Learning Outcomes

- LMS Versions

- Module 1: Forming Your Research Question

- Module 2: Searching for Information Online

- Module 3: Advanced Searching

- Module 4: Evaluating Sources

- Module 5: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

- Module 6: Scholarly Articles

- Module 7: Information Cycles and Communication Sources

- Module 8: Misinformation and Media Bias

- Module 9: Organizing Sources

- Module 10: Academic Integrity

- Module 11: Understanding Plagiarism & Citing Sources

- Module 12: Copyright, Fair Use, & Public Domain

Module 13: Literature Reviews

- Module 14: Scholarly Conversation

- Other PALNI Information Literacy Resources This link opens in a new window

Introduction

(JESHOOTS.COM, Unsplash )

Have you been assigned a literature review and have no idea what it is or where to start? Don't fret! In this module, what literature reviews are and some tips on how to write them will be reviewed. You’ll then complete an activity and quiz to improve comprehension.

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- List different ways to organize a literature review.

- Discuss what should be included in each section of a literature review.

- Successfully write a literature review.

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review? It’s exactly what it says—it’s a review of the published literature on a specific topic. When writing a literature review, you want to read and write about everything you can possibly find regarding your topic, which typically consists of books and scholarly articles written by experts in the field you are researching.

By conducting your literature review, you’ll find patterns and trends in the professional literature, influential people and studies, and also identify any gaps in the research that can help you recognize areas that can be studied in the future.

Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

According to Scribbir (2020) there are four main ways you can structure your literature review, so choose the way that is most appropriate for your topic. Each of the four ways will allow you to identify trends and patterns in the literature, which is one of the main purposes of writing a literature review.

- Chronologically: Writing about the sources in order from oldest to newest. This structure answers the questions: what were some of the first studies that were conducted regarding your topic and how has the research or topic evolved over time?

- Thematically: Structuring your sources by theme, such as methodology, populations studied, concept addressed, etc.

- Methodologically: Organizing your sources by which methods were utilized in the studies you are reading about. Did scholars investigate your topic in similar or different ways? Was one methodology utilized more than others? Are there other methodologies that have yet to be studied?

- Theoretically: Identifying and discussing opposing theories regarding your topic.

Writing the Literature Review

In the introduction, you need to establish your research question, give a brief background on the topic if you’re not writing chronologically, state the importance of your topic and why the reader should care about it, and lastly discuss the scope of your literature review.

In the body of your literature review (which should be the longest part of your paper), you are going to summarize, synthesize, and analyze each source. Analyze means to break something down into parts (like you’ll do for each source) and synthesize means to bring things together (how you’ll explain how different sources relate to one another). You’ll evaluate each source’s strengths and weaknesses. Have any patterns in the research emerged? Do studies support earlier studies, or contradict them? Are there influential studies that always get mentioned? If so, be sure to read those!

It’s important when writing the body of your literature review that you use topic sentences and transitions so that your lit review has a logical flow.

Last is the conclusion section. Here is where you’ll summarize major findings, discuss the implications of the published research, and identify research gaps, or areas of future research. You want to make sure that your literature review is exhaustive, meaning you’ve attempted to find all the published research on your topic—you don’t want to leave anything important out!

Tips and Tricks

- Start early! Don't procrastinate! In order to find everything that has been written on your topic, you’ll probably have to utilize interlibrary loan services and request articles and books from other libraries in the United States. Did I mention this service is free? It can take a few days to a few weeks to receive those sources, so make sure you are allowing yourself enough time to do a thorough job.

- Y ou only need to start off with one substantial article —once you’ve found that, be sure to look at the sources that are cited in the article’s bibliography, and then you can find those. If you don’t know how to find sources in a bibliography, that’s a great time to schedule an appointment with a reference librarian!

- Think of all the possible synonyms that could be used to describe your search terms. Are you writing about teenagers? If so, you should also search for young adults, adolescents, and teens. You want to make sure you’re including words in your search that various authors writing about your topic are using. Has your topic been studied globally? Don’t forget to include different spelling variations of your search terms. Failing to use synonyms and spelling variations could mean you miss some important literature!

- Look in more than one place . Are you unfamiliar with the variety of databases your library subscribes to? Again, this is a great time to make an appointment with a librarian! They can suggest numerous places you can look so that your research is in-depth enough to be exhaustive.

- Don’t forget to use Google Scholar . It has a great feature which tells you how many times a source has been cited, so this can be very helpful in identifying pivotal studies that you want to make sure you include in your review.

- Utilize your friendly librarian! They help students with research every day, so they are sure to teach you some tips and tricks to make your research process more enjoyable!

Acknowledgements

The content for this module was drawn from the following sources:

Klohe, K., Koudou, B. G., Fenwick, A., Fleming, F., Garba, A., Gouvras, A., Harding-Esch, E. M., Knopp, S., Molyneux, D., D’Souza, S., Utzinger, J., Vounatsou, P., Waltz, J., Zhang, Y., & Rollinson, D. (2021). A systematic literature review of schistosomiasis in urban and peri-urban settings. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease s, 15(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008995

Plachouri, K.-M., Florou, V., & Gorgeous, S. (2019). Therapeutic strategies for pigmented purpuric dermatoses: A systematic literature review. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 30 (2), 105-109. http://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2018.1473553

Scribbir. (2020). How to write a good literature review . [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIYC6zG265E&list=PLjBMY3HggCpCEpa2VIXXM1udk9kcknahX&index=2

Traylor, A. M., Stahr, E., & Salas, E. (2020). Team coaching: Three questions and a look ahead: A systematic literature review. International Coaching Psychology Review, 15 (2), 54–68.

Activity and Quiz

See the Google doc here for activity and quiz questions and answers. Please note, this document is stored on the PALNI team drive and is only accessible to those who work in a PALNI school.

All of the PALNI Information Literacy Modules are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- << Previous: Module 12: Copyright, Fair Use, & Public Domain

- Next: Module 14: Scholarly Conversation >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 12:16 PM

- URL: https://libguides.palni.edu/instruction_resources

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, research competencies to develop academic reading and writing: a systematic literature review.

- Tecnologico de Monterrey, Escuela de Humanidades y Educación, Monterrey, Mexico

Rationale: The development of research skills in the higher education environment is a necessity because universities must be concerned about training professionals who use the methods of science to transform reality. Furthermore, within research competencies, consideration must be given to those that allow for the development of academic reading and writing in university students since this is a field that requires considerable attention from the educational field at the higher level.

Objective: This study aims to conduct a systematic review of the literature that allows the analysis of studies related to the topics of research competencies and the development of academic reading and writing.

Method: The search was performed by considering the following quality criteria: (1) Is the context in which the research is conducted at higher education institutions? (2) Is the development of academic reading and writing considered? (3) Are innovation processes related to the development of academic reading and writing considered? The articles analyzed were published between 2015 and 2019.

Results: Forty-two papers were considered for analysis after following the quality criterion questions. Finally, the topics addressed in the analysis were as follows: theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies, dominant trends and methodological tools, findings in research competencies for innovation in academic literacy development, types of innovations related to the development of academic reading and writing, recommendations for future studies on research competencies and for the processes of academic reading and writing and research challenges for the research competencies and academic reading and writing processes.

Conclusion: It was possible to identify the absence of studies about research skills to develop academic literacy through innovative models that effectively integrate the analysis of these three elements.

Introduction

Research skills today must be developed in such a way that students in higher education will be enabled to make them their own for good. This type of competencies is given fundamentally in the aspects of methodological domain, information gathering and the management of document-writing norms and technological tools. Furthermore, the usefulness of the existence of mediating didactics is recognized ( Aguirre, 2016 ). The competencies considered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in its skills strategy are the following: the development of relevant competencies, the activation of those competencies in the labor market and the use of those competencies effectively for the economy and society ( OECD, 2017 ). The research competences established by Mogonea and Remus Mogonea (2019) from the implementation of a pedagogical research project are as follows: the acquisition of new knowledge, the identification of educational problems, synthesis and argumentation, metacognition, knowledge of new research methods, the possibility of developing research tools and the interpretation and dissemination of results. Research skills work for various disciplines and can even link them. Some studies have affirmed the value of facilitating interactions between researchers from different research fields within a discipline ( Hills and Richards, 2013 ). Therefore, research competencies are approached from distinct perspectives. In this study, the focus is on those that allow for the development of academic reading and writing, because it is an area that requires a boost because it is basic for undergraduate students to be able to understand texts of different kinds and to be able to write with academic rigor.

Academic writing is one aspect that has been focussed on in the educational context. It is a multiple construction that unites such essential elements as the understanding of the scientific field and the understanding of scientific research methodology, statistical knowledge and the understanding of the culture of native and foreign languages ( Lamanauskas, 2019 ). Currently, a change in expectations has emerged around academic writing, and it has become increasingly evident that a much longer and gradual orientation in the process of research and information gathering is desirable to better meet the needs of contemporary students ( Hamilton, 2018 ). On the basis of historical emphasis on writing instruction, five approaches are illustrated, namely, skills, creative writing, process, social practice, and socio-cultural perspective ( Kwak, 2017 ). Academic writing is thus conceived as a way in which young people can construct their own according to elements that provide academic rigor through an efficient interaction with texts.

Academic reading and writing are a fundamental part of the context of higher education. Academic reading and writing also includes the learning of foreign languages as the gender-based approach to the teaching of writing has been found to be useful in promoting the development of literacy through the explicit teaching of characteristics, functions, and options of grammar and vocabulary that are available to interpret and produce various specific genres ( Trojan, 2016 ). Young university students come from a system of basic and upper secondary education in which the fundamental thing was to learn through the repetition of texts, but now their ideas, knowledge, capacity for analysis and critical thinking are a central aspect ( Bazerman, 2014 ). Understanding reading practices and needs in the context of information seeking can refine our understanding of the choices and preferences of users for information sources (such as textbooks, articles, and multimedia content) and media (such as printed and digital tools used for reading) ( Carlino, 2013 ; Lopatovska and Sessions, 2016 ). In this sense, it is useful to consider academic literacy, a name that Carlino (2013) has given to teaching process that may (or may not) be put in place to facilitate students' access to the different written cultures of the disciplines (p. 370). Currently, the many ways in which students perform the process of academic reading and writing must be addressed so that an improvement in the process can be attained.

Within the study of research competencies for the development of academic reading and writing, theoretical–conceptual trends and methodological designs play an important role. Ramírez-Montoya and Valenzuela (2019) considered psychopedagogical, socio-cultural, use and development of technology, disciplinary and educational management studies as theoretical–conceptual trends. According to Harwell (2014) , for methodological analysis, the categories of experimental design, quasi-experimental design, pre-experimental design, and within quantitative methods are used, and for qualitative methods, phenomenological, narrative and case studies, grounded theory and ethnography are contemplated. Documentary research is also added because there are studies on this type related to the subject, which are considered to be excluded.

In the research field, the findings and innovation that are increasingly present are a fundamental part. For the area of findings, the classification contemplated by Ramírez-Montoya and Lugo-Ocando (2020) must be considered. The author commented that innovation can create a new process (organization, method, strategy, development, procedure, training, and technique), a new product (technology, article, instrument, material, device, application, manufacture, result, object, and prototype), a new service (attention, provision, assistance, action, function, dependence, and benefit) or new knowledge (transformation, impact, evolution, cognition, discernment, knowledge, talent, patent, model, and system). Various types of innovation are available, such as those addressed by Valenzuela and Valencia (2017) which consider the following: (a) continuous innovation: when small deviations in educational practices accumulate, they translate into profound changes; (b) systematic: it is methodical and ordered like the innovation of continuous improvement, but the scope and novelty of its changes may vary and even lead to substantial changes; and (c) disruptive: they are new contributions to the world and generate fundamental changes in the activities, structure and functioning of organizations. Another type of innovation is open innovation, which is defined by Chesbrough (2006) as the deliberate use of knowledge inputs and outputs to accelerate internal innovation and expand it for the external use of innovation in markets. Educational purposes and divergent contexts can determine the type of innovation applied.

Many factors converge in the development of academic reading and writing. Digital skills are essential elements in enriching academic reading and writing. In the framework for the development and understanding of digital competences in Europe, five areas of digital competences exist, namely, (a) information: judging its relevance and purpose through identifying, locating, retrieving, storing, organizing, and analyzing digital information; (b) communication: taking place in digital environments or using digital tools to link to others and interacting in networked communities; (c) content creation: some elements include creating and editing new content and enforcing intellectual property rights and licenses; (d) security: personal protection, protection of digital identity, and safe and sustainable use and (e) problem solving: some aspects include making informed decisions about which digital tools are best suited for which purpose or need, creatively using technologies and updating the skills of individuals ( Ferrari, 2013 ). The changing environment of higher education offers an uncertain information ecosystem that requires greater responsibility on the part of students to create new knowledge and to select and use information appropriately ( Association of College Research Libraries, 2000 ). The Association of College and Research Libraries 2016 includes some key information literacy (IL) concepts: information creation as a process, information as value, research as inquiry and search as strategic exploration. Academic literacy can be better developed if IL and digital competencies are considered.

Research studies have presented challenges that must be considered for future research. Within the research gaps addressed in the classification of Kroll et al. (2018) for the study of research competencies, some of the categories are appropriate: Research Topic (RT) 1: Collaboration, RT2: Feasibility, RT3: Knowledge Sharing, RT4: Research Opportunities and RT6: Skill Differences. Critical thinking and academic literacy are considered amongst the challenges for developing academic writing from research skills. The first is considered as the process that involves conceptualization, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of the information collected from observation and experience as a guide for belief and action ( Sellars et al., 2018 ). Academic literacy according to Solimine and Garcia-Quismondo (2020) grows within a competency-based educational model, in which competencies are recognized as the developments in the learners of informational behaviors and attitudes that make them expert evaluators of digital and virtual web contents to obtain knowledge and know-how. Reflection and critical thinking are basic elements for an adequate interaction in digital media.

Several items were identified from mapping and systematic literature reviews related to the topics of research skills and academic literacy development. Abu and Alheet (2019) conducted a study to identify those competencies that an individual must possess to be a good researcher. A competency-based assessment throughout the research training process to more objectively evaluate the development of doctoral students and early career scientists is proposed by Verderame et al. (2018) . Moreover, Zetina et al. (2017) concluded that designing strategies for the adequate development of research competencies with the purpose of training sufficiently qualified young researchers is crucial. Walton and Cleland (2017) also presented qualitative research with the purpose of establishing whether students as part of a degree module can demonstrate through their online textual publications their IL skills as a discursive competence and social practice. Lopatovska and Sessions (2016) conducted a study examining reading strategies in relation to information-seeking stages, tasks and reading media in an academic setting.

This study aims to determine how the three elements present in the quality criteria (research skills, academic reading and writing and innovation processes) of this systematic review of the literature can be linked so that they can serve as a basis for identifying which research skills can be used to develop academic reading and writing in higher education contexts through innovative models. IL is presented as a fundamental competence because for the adequate development of academic reading and writing, university students must be able to perform efficiently in the search, selection and treatment of information.

The method followed for the present research was the systematic review of literature [based on Kitchenham and Charters (2007) ], which considers within the phases to follow the review of a protocol to specify the research question. The search started with the articles that emerged from a systematic mapping of literature that was previously carried out; subsequently, quality criteria were defined that allowed refining the selection of articles for the systematic literature review, inclusion and exclusion criteria were also determined, and six research questions were also established for the analysis of the articles.

Research Questions

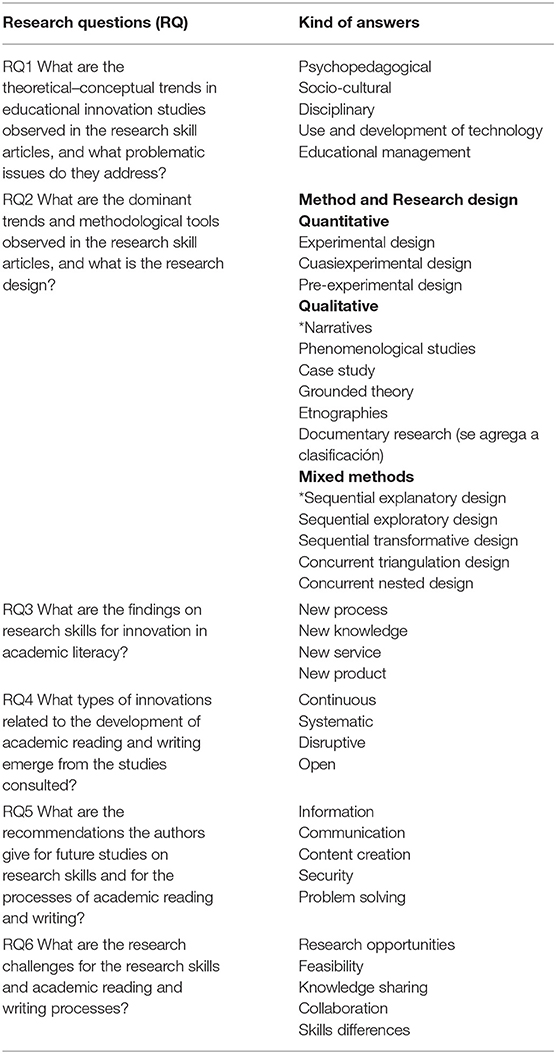

The starting point was to locate themes that were of interest for investigating writing processes within the framework of research skills and educational innovation to establish research questions. Six questions were located, and possible systems for classifying answers were studied on the basis of the literature. Table 1 lists the questions that guided the study.

Table 1 . Research questions and kind of answers in the systematic literature review.

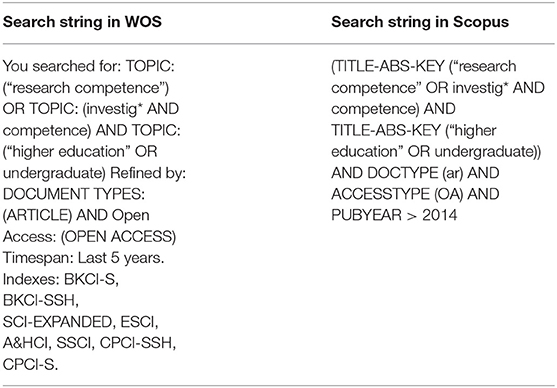

Search Strategy

In a systematic mapping of literature (SML) that was previously conducted, the search strings shown in Table 2 were used. The search criteria are explained below.

Table 2 . Search strings in Scopus and WOS.

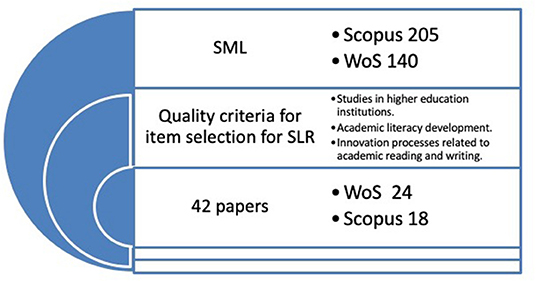

On the basis of the 345 articles that emerged from the search process that was conducted for the previous SML, the following quality criteria were considered for the selection of the articles to be included in this SLR: (a) Is the context in which the study is conducted in higher education institutions, (b) Is the development of academic reading and writing considered?, and (c) Are innovation processes related to the development of academic reading and writing considered? It was contemplated that they would cover at least two of three points to define the articles that would remain for the analysis. In the first instance, 52 articles were left, but those whose language was different from English and Spanish were later excluded, given the poor representativeness of articles written in other languages. Therefore, only 42 papers were finally analyzed.

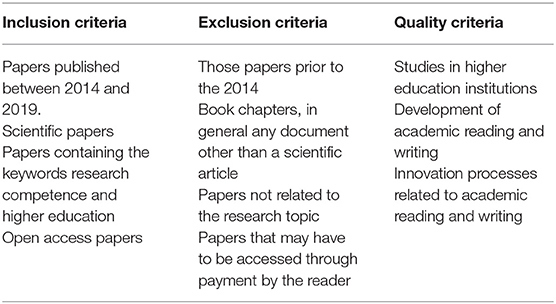

Inclusion, Exclusion, and Quality Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria must capture and incorporate the questions that the SLR seeks to answer, and the criteria must also be practical to apply. If they are too detailed, then the selection may be excessively complicated and lengthy. For the systematic mapping, the disciplinary areas that had the highest number of articles were Education (40%) and Medicine (36%). For the systematic review of the literature, it was considered that the context for the selection of articles should be limited to higher education institutions. Table 3 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the SML and the quality criteria for article selection.

Table 3 . Inclusion, exclusion, and quality criteria.

Finally, after applying the quality criteria, there were 42 articles left to be analyzed in the SLR, which are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4 . Articles that were analyzed.

RQ1 What are the theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies observed in the research skill articles?

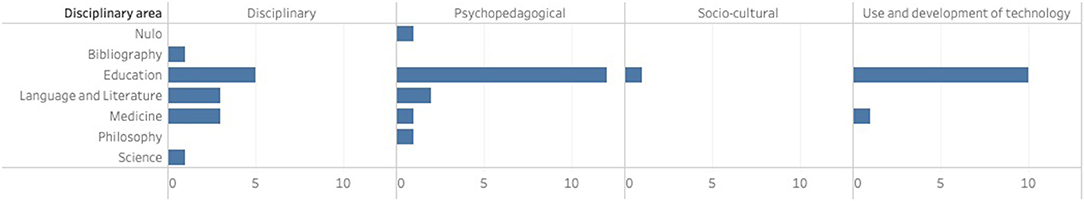

The 42 articles analyzed the disciplinary approaches according to the Library of Congress Classification, which made it possible to place them in the six disciplines referred to in this study and allowed their correspondence with the theoretical–conceptual trends of educational innovation (psychopedagogical, socio-cultural, disciplinary, use and development of technology and educational management), where a greater preponderance was found in articles under the heading of Psychopedagogical Studies (1, 2, 7, 8, 16–18, 20, 22, 24, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38), as shown in Figure 2 .

The disciplinary approach allows for the consideration of which areas the research topic has the greatest influence on and is generating the most interest for study. In carrying out systematic literature mappings, identifying the disciplinary areas that have a greater presence is highly useful because it serves as a basis for determining which area or areas can be focussed on for future systematic literature reviews.

RQ2 What are the dominant trends and methodological tools observed in the research skill articles?

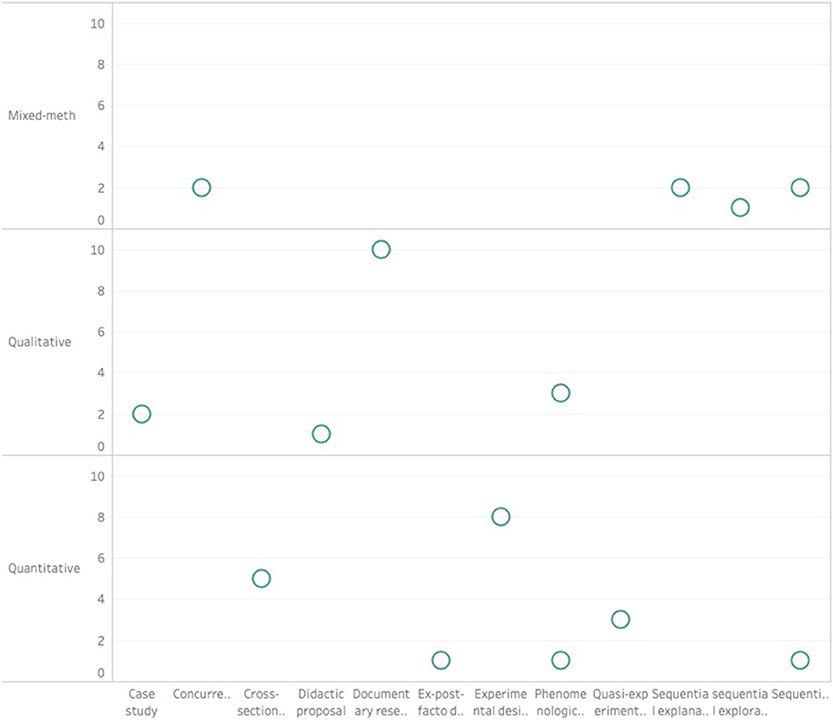

The study addressed the different research methods: quantitative, qualitative and mixed method. The classification used is shown in Figure 3 and allows identifying that in the experimental design the quantitative method predominated (4, 5, 10, 14, 21, 27, 30, 31), on the other hand in the documentary research there was a predominance of the qualitative method (6–8, 18, 26, 36–38, 41, 42).

To have a more detailed idea of the trend of the methods used in the articles that deal with the analysis of research skills for academic literacy development, starting only from the three main methods is insufficient. Having a sub-classification that allows us to know the types of research designs that are performed in each method is a must. Presenting the specific research design allows for more detailed information, especially if the entire process followed in the research method is clearly explained.

RQ3 What are the findings in research skills for innovation in academic literacy development?

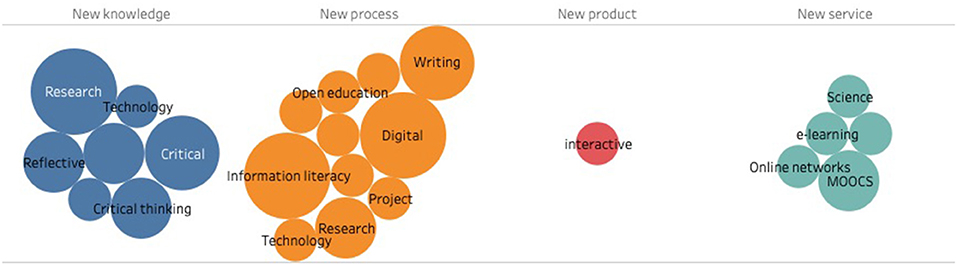

The findings focussed on four categories: (1) new knowledge (1, 3, 7, 9, 15, 20, 21, 24, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36) which were stated in this category when referring to transformation, impact, evolution, cognition, dissent, knowledge, talent, patent, model or system. For instance, Article 1 was considered because it talks about how students acquired knowledge about the choice of an appropriate research instrument and learned to articulate their identity as researchers, and Article 20 was considered in this category because the study investigated whether the teaching of communicative languages helps develop the critical thinking of students; (2) new process (2, 4–6, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 28, 37–42), the findings in this category considered an organization, a method, a strategy, a development, a procedure, a training or a technique, e.g., Article 2, were considered as the students who participated in the process of becoming good scholars by using appropriate online publications to create valid arguments by evaluating the work of others and Article 22, as this study analyses the strategies activated by a group of 36 Portuguese university students when faced with an academic writing practice in Spanish as a foreign language; (3) new product (10), findings were considered in this category when considering a technology, an article, a tool, a material, a device, an application, a manufacture, a result, an object or a prototype, e.g., Article 10 was integrated because the document illustrates the development of an online portal and a mobile application aimed at promoting student motivation and engagement; (4) new service (11, 13, 17, 26, 31, 33), the findings were stated in this category when considering elements, such as attention, provision, assistance, action, function, dependence or benefit, e.g., Article 17 that presents the Summer Science Program in México, which aims to provide university students with research competence and Article 33, as it states that online academic networks have been established as spaces for academics from all countries and as outlets for their insight and literacy. Below are the key words that appeared most often in each category in Figure 4 .

Innovation is present in the findings found in the articles through the idea that it starts from something existing to generate something new, gives a new meaning and a new idea through elements, such as those considered in the classification used in this systematic review of literature. Innovative elements do not necessarily have to contemplate technology, innovating can consist of providing new solutions that respond to specific needs, which can be useful not only in economic and social scenarios but also in the educational context.

RQ4 What types of innovations related to the development of academic reading and writing emerge from the studies consulted?

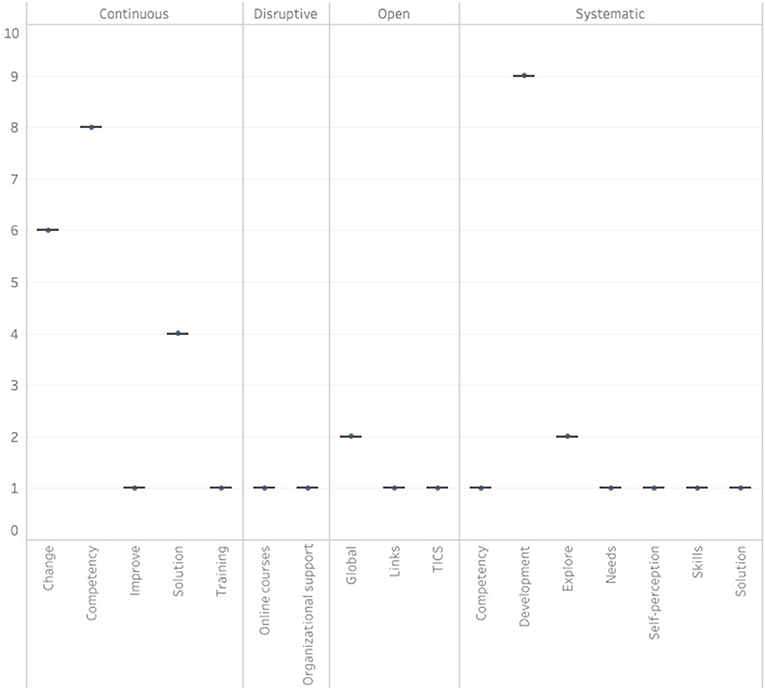

The categories on which the classification of the types of innovation focussed were the following: continuous, systematic, disruptive and open. In continuous innovation, the keywords change, competency, improve, solution and training were placed. In systematic innovation, the keywords were competency, development, explore, needs, self-perception, skills, and solution. In disruptive innovation, the keywords were online courses and organizational support. In open innovation, the keywords global, links and ICTS were located. In the systematic category, more articles were about development (2, 5–7, 11, 13, 14, 16, 21–23, 27, 28, 32, 35, 42), as shown in Figure 5 .

The distinct types of innovation allow us to know at what level an innovation is being conducted to know how much emphasis is given to the part of generating innovation within research if it is considered something that occurs gradually or if, on the contrary, it is considered that it requires drastic changes that can be generated even immediately. Moreover, nowadays, open innovation has become increasingly important, especially in the field of higher education where knowledge repositories are now considered open spaces.

RQ5 What are the recommendations that the authors give for future studies on research skills and for the processes of academic reading and writing?

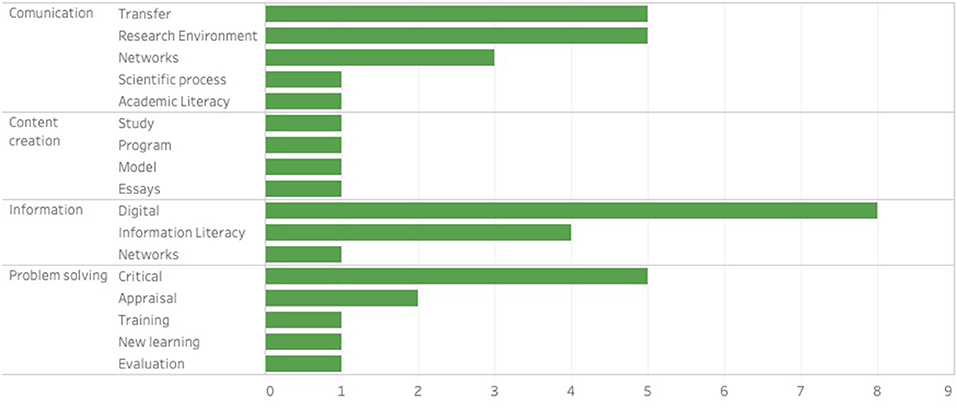

The study first identified the recommendations that the authors made for future studies in the framework of research skills and academic literacy processes. Subsequently, the categories presented in Figure 6 were established. The item that had the most presence around the category of Information was the digital element because it was considered in some studies that learning had a positive effect through the use of digital resources (6, 11, 13, 15, 29, 31, 41, 42).

Today, in the digital economy, the role of knowledge production in information systems is increasing dramatically. The same is true in the field of education; therefore, making appropriate use of these digital resources in accordance with the stated research purposes is necessary. The digital era is complex and requires flexible education that enhances new skills, and higher education students must be trained to efficiently use the wide diversity of digital resources now available to them and to perform well in virtual environments.

RQ6 What are the research challenges for the research skills and academic reading and writing processes?

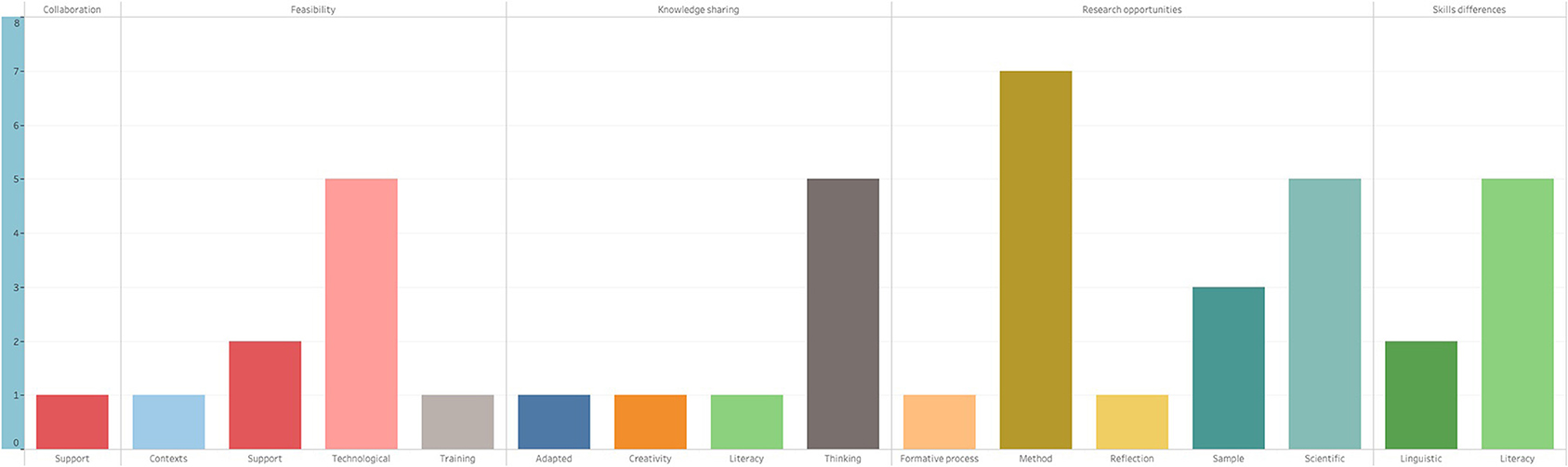

The challenges were analyzed, and the following were located: collaboration (support), feasibility (contexts, technological, training, and support), knowledge sharing (literacy, thinking, creativity and adapted), research opportunities (reflection, scientific, method, sample, formative process, and skills) and differences (literacy and linguistic). Amongst the challenges shown in the studies that were addressed in this study, those related to research opportunities (1, 4–6, 9, 11–14, 16, 17, 19, 30, 33, 34, 36, 39) stand out, followed by learning sharing (2, 8, 18, 20, 26, 27, 31, 42) and viability (7, 10, 15, 25, 29, 32, 38, 40, 41), as can be seen in Figure 7 .

The challenges in research allow us to identify on which topics the researcher should concentrate to be able to give solutions to problems posed around a research topic because knowing which obstacles have been presented in a specific research process is interesting so that they can serve as a basis for further studies. The challenges presented in research can be of various kinds, from questions such as the financial support required according to the type and time of research to the viability related to aspects such as the necessary skills or the mastery of the use of technology to make research feasible.

Amongst the theoretical–conceptual trends, the one corresponding to Psychopedagogical Studies has turned out to be the one that has focussed more on the analysis of research skills for the development of academic writing. Figure 1 depicts that there was a greater trend of articles in psychopedagogical matters and that they were distributed in various disciplinary areas. Psychopedagogical studies focus on cognitive elements and on social–emotional elements and improvements in academic achievement ( Ramírez-Montoya and Valenzuela, 2019 ). In this review, the psychopedagogical approach is framed mainly in the application of didactic techniques, educational programmes, forms of evaluation and training and capacity building.

Figure 1 . Quality criteria for papers selection for SLR.

Experimental studies are a frequently used method in the topic of research skills. Figure 2 shows that the most commonly used research design in the articles consulted is the experimental design. However, methodological designs are available in the studies analyzed. The older categorisations of experimental designs tend to use the language of the analysis of variance to describe these arrangements ( Harwell, 2014 ). In this study, the approach of that type of design was considered because randomization was sought for the selection of the sample to be investigated. Nonetheless, various methodological designs were used in the review, and it was even decided to consider research of a documentary nature to guide the present study.

Figure 2 . Theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies.

New processes are identified with greater emphasis on the analysis of research toward the development of academic reading and writing within the framework of research competencies. Figure 3 illustrates that according to the classification addressed, the category of new processes is the one that received the most mention in the analysis. Ramírez-Montoya and Lugo-Ocando (2020) validated that a new process is characterized amongst its elements by an organization, a method, a technique, and a procedure. In this analysis, it was possible to observe that to a great extent, the findings are based on processes that imply a follow-up to determine how the evolution to reach the proposed objectives occurs.

Figure 3 . Trends and methodological tools.

Systematic and continuous innovations have a strong presence in the area of innovation in research skill studies. Figure 4 shows the trend in these types of innovation. In terms of systematic innovation, there was a greater presence of the development aspect, whilst continuous innovation had a greater presence of the competence aspect. Continuous innovation is something that has to do with small changes that can make a difference, and systematic innovation is methodical and orderly like continuous improvement innovation. However, the scope and novelty of its changes can vary and even lead to substantial changes ( Valenzuela and Valencia, 2017 ). The innovations must be based on the objectives to be achieved and always with a view to achieving substantial improvement.

Figure 4 . Findings in research skills for academic literacy development.