How to tell the difference between persuasion and manipulation

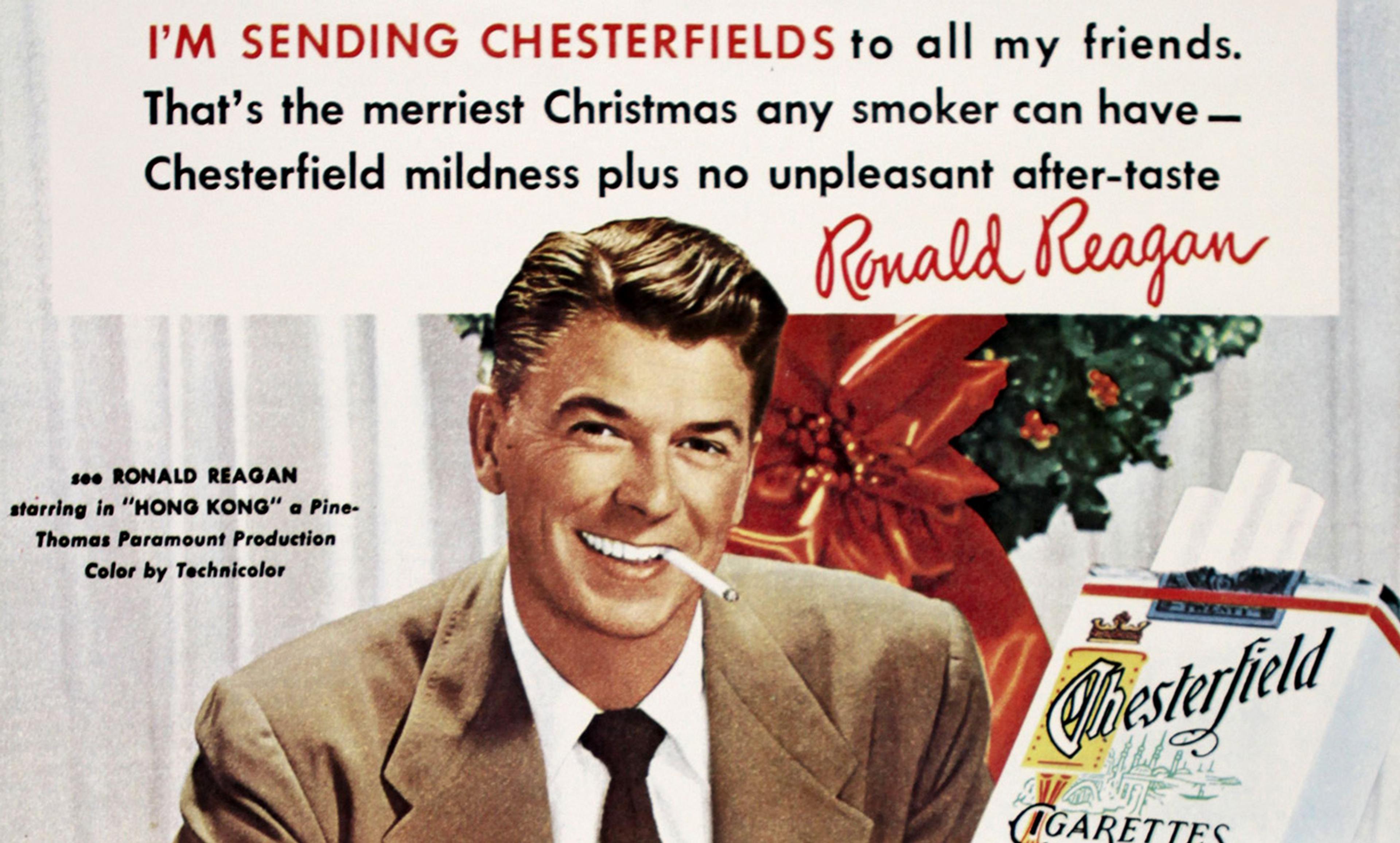

Detail from a 1973 Chesterfield cigarettes advertisement. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

by Robert Noggle + BIO

Calling someone manipulative is a criticism of that person’s character. Saying that you have been manipulated is a complaint about having been treated badly. Manipulation is dodgy at best, and downright immoral at worst. But why is this? What’s wrong with manipulation? Human beings influence each other all the time, and in all sorts of ways. But what sets manipulation apart from other influences, and what makes it immoral?

We are constantly subject to attempts at manipulation. Here are just a few examples. There is ‘gaslighting’, which involves encouraging someone to doubt her own judgment and to rely on the manipulator’s advice instead. Guilt trips make someone feel excessively guilty about failing to do what the manipulator wants her to do. Charm offensives and peer pressure induce someone to care so much about the manipulator’s approval that she will do as the manipulator wishes.

Advertising manipulates when it encourages the audience to form untrue beliefs, as when we are told to believe that fried chicken is a health food, or faulty associations, as when Marlboro cigarettes are tied to the rugged vigour of the Marlboro Man. Phishing and other scams manipulate their victims through a combination of deception (from outright lies to spoofed phone numbers or URLs) and playing on emotions such as greed, fear or sympathy. Then there is more straightforward manipulation, perhaps the most famous example of which is when Iago manipulates Othello to create suspicion about Desdemona’s fidelity, playing on his insecurities to make him jealous, and working him up into a rage that leads Othello to murder his beloved. All these examples of manipulation share a sense of immorality. What is it that they have in common?

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it harms the person being manipulated. Certainly, manipulation often harms. If successful, manipulative cigarette ads contribute to disease and death; manipulative phishing and other scams facilitate identity theft and other forms of fraud; manipulative social tactics can support abusive or unhealthy relationships; political manipulation can foment division and weaken democracy. But manipulation is not always harmful.

Suppose that Amy just left an abusive-yet-faithful partner, but in a moment of weakness she is tempted to go back to him. Now imagine that Amy’s friends employ the same techniques that Iago used on Othello. They manipulate Amy into (falsely) believing – and being outraged – that her ex-partner was not only abusive, but unfaithful as well. If this manipulation prevents Amy from reconciling, she might be better off than she would have been had her friends not manipulated her. Yet, to many, it could still seem morally dodgy. Intuitively, it would have been morally better for her friends to employ non-manipulative means to help Amy avoid backsliding. Something remains morally dubious about manipulation, even when it helps rather than harms the person being manipulated. So harm cannot be the reason that manipulation is wrong.

Perhaps manipulation is wrong because it involves techniques that are inherently immoral ways to treat other human beings. This thought might be especially appealing to those inspired by Immanuel Kant’s idea that morality requires us to treat each other as rational beings rather than mere objects. Perhaps the only proper way to influence the behaviour of other rational beings is by rational persuasion, and thus any form of influence other than rational persuasion is morally improper. But for all its appeal, this answer also falls short, for it would condemn many forms of influence that are morally benign.

For example, much of Iago’s manipulation involves appealing to Othello’s emotions. But emotional appeals are not always manipulative. Moral persuasion often appeals to empathy, or attempts to convey how it would feel to have others doing to you what you are doing to them. Similarly, getting someone to fear something that really is dangerous, to feel guilty about something that really is immoral, or to feel a reasonable level of confidence in one’s actual abilities, do not seem like manipulation. Even invitations to doubt one’s own judgment might not be manipulative in situations where – perhaps due to intoxication or strong emotions – there really is good reason to do so. Not every form of non-rational influence seems to be manipulative.

I t appears, then, that whether an influence is manipulative depends on how it is being used. Iago’s actions are manipulative and wrong because they are intended to get Othello to think and feel the wrong things. Iago knows that Othello has no reason to be jealous, but he gets Othello to feel jealous anyway. This is the emotional analogue to the deception that Iago also practises when he arranges matters (eg, the dropped handkerchief) to trick Othello into forming beliefs that Iago knows are false. Manipulative gaslighting occurs when the manipulator tricks another into distrusting what the manipulator recognises to be sound judgment. By contrast, advising an angry friend to avoid making snap judgments before cooling off is not acting manipulatively, if you know that your friend’s judgment really is temporarily unsound. When a conman tries to get you to feel empathy for a non-existent Nigerian prince, he acts manipulatively because he knows that it would be a mistake to feel empathy for someone who does not exist. Yet a sincere appeal to empathy for real people suffering undeserved misery is moral persuasion rather than manipulation. When an abusive partner tries to make you feel guilty for suspecting him of the infidelity that he just committed, he is acting manipulatively because he is trying to induce misplaced guilt. But when a friend makes you feel an appropriate amount of guilt over having deserted him in his hour of need, this does not seem manipulative.

What makes an influence manipulative and what makes it wrong are the same thing: the manipulator attempts to get someone to adopt what the manipulator herself regards as an inappropriate belief, emotion or other mental state. In this way, manipulation resembles lying. What makes a statement a lie and what makes it morally wrong are the same thing – that the speaker tries to get someone to adopt what the speaker herself regards as a false belief. In both cases, the intent is to get another person to make some sort of mistake. The liar tries to get you to adopt a false belief. The manipulator might do that, but she might also try to get you to feel an inappropriate (or inappropriately strong or weak) emotion, attribute too much importance to the wrong things (eg, someone else’s approval), or to doubt something (eg, your own judgment or your beloved’s fidelity) that there is no good reason to doubt. The distinction between manipulation and non-manipulative influence depends on whether the influencer is trying to get someone to make some sort of mistake in what he thinks, feels, doubts or pays attention to.

It is endemic to the human condition that we influence each other in all sorts of ways besides pure rational persuasion. Sometimes, these influences improve the other person’s decision-making situation by leading her to believe, doubt, feel or pay attention to the right things; sometimes, they degrade decision-making by leading her to believe, doubt, feel or pay attention to the wrong things. But manipulation involves deliberately using such influences to hamper a person’s ability to make the right decision – that is the essential immorality of manipulation.

This way of thinking about manipulation tells us something about how to recognise it. It is tempting to think that manipulation is a kind of influence. But as we have seen, kinds of influences that can be used to manipulate can also be used non-manipulatively. What matters in identifying manipulation is not what kind of influence is being used, but whether the influence is being used to put the other person into a better or a worse position to make a decision. So, if we are to recognise manipulation, we must look not at the form of influence, but at the intention of the person using it. For it is the intention to degrade another person’s decision-making situation that is both the essence and the essential immorality of manipulation.

Computing and artificial intelligence

Algorithms associating appearance and criminality have a dark past

Catherine Stinson

Childhood and adolescence

For a child, being carefree is intrinsic to a well-lived life

Luara Ferracioli

Meaning and the good life

Sooner or later we all face death. Will a sense of meaning help us?

Warren Ward

Philosophy of mind

Think of mental disorders as the mind’s ‘sticky tendencies’

Kristopher Nielsen

Philosophy cannot resolve the question ‘How should we live?’

David Ellis

Rituals and celebrations

We need highly formal rituals in order to make life more democratic

Antone Martinho-Truswell

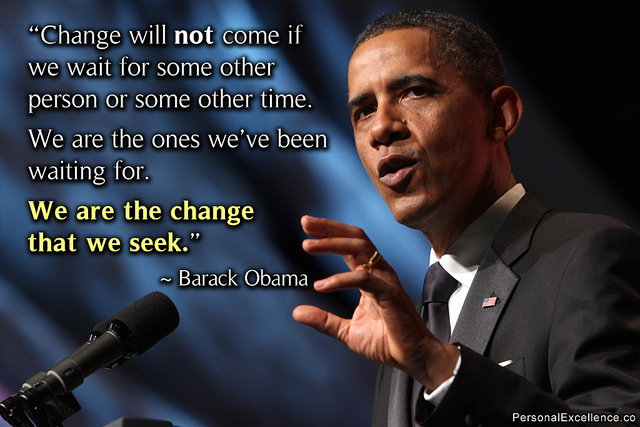

The Ethical Edge of Persuasion

Where is the line between persuasion, manipulation and coercion.

Posted February 25, 2021

In our earlier post, we discussed ethical manipulation in leadership . Here, we delve into ethics and persuasion .

Persuasion is an ethical form of influence that leaders use to compel their followers to act. Sometimes referred to as an art, leaders can even read books and take classes that give them the skills needed to package and present ideas in a way that engages people to follow. Persuasion in this case is seen as good, and even ethical, but as with anything… too much of a good thing can turn into a bad thing.

Persuasion is just one form of influence. Manipulation, persuasion gone rogue, and coercion, a persuasive offer you literally can’t refuse, are two other forms of influence that an ethical leader would potentially want to stay away from.

But where is the edge? How does an ethical leader continue to persuade without passing the point of no return into unethical behavior? This is an important question, because once you fall off, there is no climbing back up.

Dr. Robert B. Cialdini, who studies persuasion, gives us six principles that we can use to see where that edge might be. Consider these principles and examples:

1. Reciprocity – people are obliged to give back to others the form of a behavior, gift, or service that they have received first.

Recognizing those you lead for their individual actions, such as an award for hard work, is good. Giving praises in the form of tangible items to a group or team as a whole is as well. The reciprocity principle says that the receiver and those who bear witness will be more likely to continue the behavior you are rewarding. The edge comes when bestowing something elaborate or maybe potentially undeserved on an individual follower. The follower, as well as onlookers, may be confused about what the gift is for, or worse, think you want something more in return.

To stay away from the ethical edge with this principle, try presenting anything given as tying directly back to their action, have the reward fit the size of the activity being rewarded, and make it come from the company or maybe the entire group. When in doubt, stay away from the cliff by leaving your personal emotions out of the transaction altogether.

2. Scarcity – people want more of those things they can have less of.

Job specialization is a great thing. Individuals working at full capacity in a unique role keep the entire team efficient. Explaining to a follower their unique contribution to an effort and discussing how this task they are performing is one-of-a-kind evokes the scarcity principle in people, making it more likely that the follower is interested in pursuing or completing the task.

Knowing this as a leader, there may be a tendency to describe uniqueness across the board, or worse, misrepresent the effort to a follower to try to make the task seem more attractive.

To stay away from the edge, realize that facts are facts. Present them as they are. And, it should go without saying, never withhold things like praise, communication or correspondence with you, or entry to meetings and other events to play on this principle. Doing so will only work against you.

3. Authority – people follow the lead of credible, knowledgeable experts.

We can’t know everything as leaders, but sometimes we like to think that we do. What’s worse, other people look at us as if we do. While hanging diplomas or adding letters of certificates after our name triggers this authority principle, it’s easy to pass the point of no return on this one. How? Speaking authoritatively about a subject which you have no knowledge of.

Be willing to stay quiet when you don’t know, or better… say “I don’t know” to stay away from the edge on this one. Rely on followers with expertise in certain areas to rise up or be an advisor to you in public or private and cite their help when speaking up about a subject. The bottom line here, resist the tendency to talk big in front of your followers.

4. Consistency – people like to be consistent with the things they have previously said or done.

When leading and wanting to persuade followers to take a large action, this principle would say to first get them to agree to smaller, voluntary, active, and public commitment along the same lines (and ideally get those commitments in writing). For example, if you want a follower to speak in front of a large group, have them commit to a talk with their team first; or if you want a follower to take on a new role, try having them agree to an assistant role. If you need their undying commitment to a vision that you have, try getting them to commit to different parts of your vision first… in this way, making the leap to the entire vision won’t be so much of a stretch.

Where can you fall off the edge on this one? Two ways: a) making or forcing followers to take the smaller commitment, thinking that when they do, surely it will be fine and they will commit to the larger role, and b) assuming followers who are OK in the smaller commitment will always adhere to this principle and make the larger leap. To stay ethical, let followers choose for themselves how far they are willing to commit.

5. Liking – people prefer to say yes to those that they like.

We all want our followers to like us, and this principle says that if they do, they are more likely to follow and do things we ask of them. Why? We like people who are similar to us and people who pay us compliments. As a leader, finding areas of similarity between you and a follower is a good thing and being able to compliment followers genuinely helps trigger this principle in followers.

The edge here should be easy to spot. Misrepresenting yourself as a leader to fit in with your followers, or paying your followers comments just to make them like you more, is clearly past the point of no return. Be careful with this one. Don’t even approach the edge because it is so easy to fall off. Get to know your followers, but be who you are, and only give compliments when extremely warranted.

6. Consensus – people will look to the actions and behaviors of others to determine their own, especially when uncertain.

Followers, by definition, follow. If you have a follower you are trying to persuade to take action, but they won’t, getting others involved to take the action around that follower may help.

The edge here comes when you as a leader falsely claim that everyone else is OK with it, or this is how everyone will be doing it soon or trying to make the follower feel bad that they haven’t gotten with the program. Triggering this principle in a positive and healthy way can be a powerful tool, but abusing it comes with a price. The ethical edge gives way quickly to manipulation and coercion.

While too much of a good thing can be bad, there are ways to climb the mountain of leadership persuasion, pushing the boundaries of ethical leadership without falling off the manipulation or coercion cliff. To do so, however, takes thoughtful consideration on the part of the leader to stay away from the ethical edge of persuasion.

Erickson, J. (2005). The Art of Persuasion. Hachette UK.

Cialdini, R. B., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion (pp. 173-174). New York: Collins.

Varun Nagaraj, Ph.D., is a visiting scholar at Case Western, and Jeff Frey, Ph.D., teaches at Rice University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

16.2: What is Persuasive Speaking?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9058

- Sarah Stone Watt@Pepperdine University & Joshua Trey Barnett@Indiana University

- Millersville University via Public Speaking Project

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

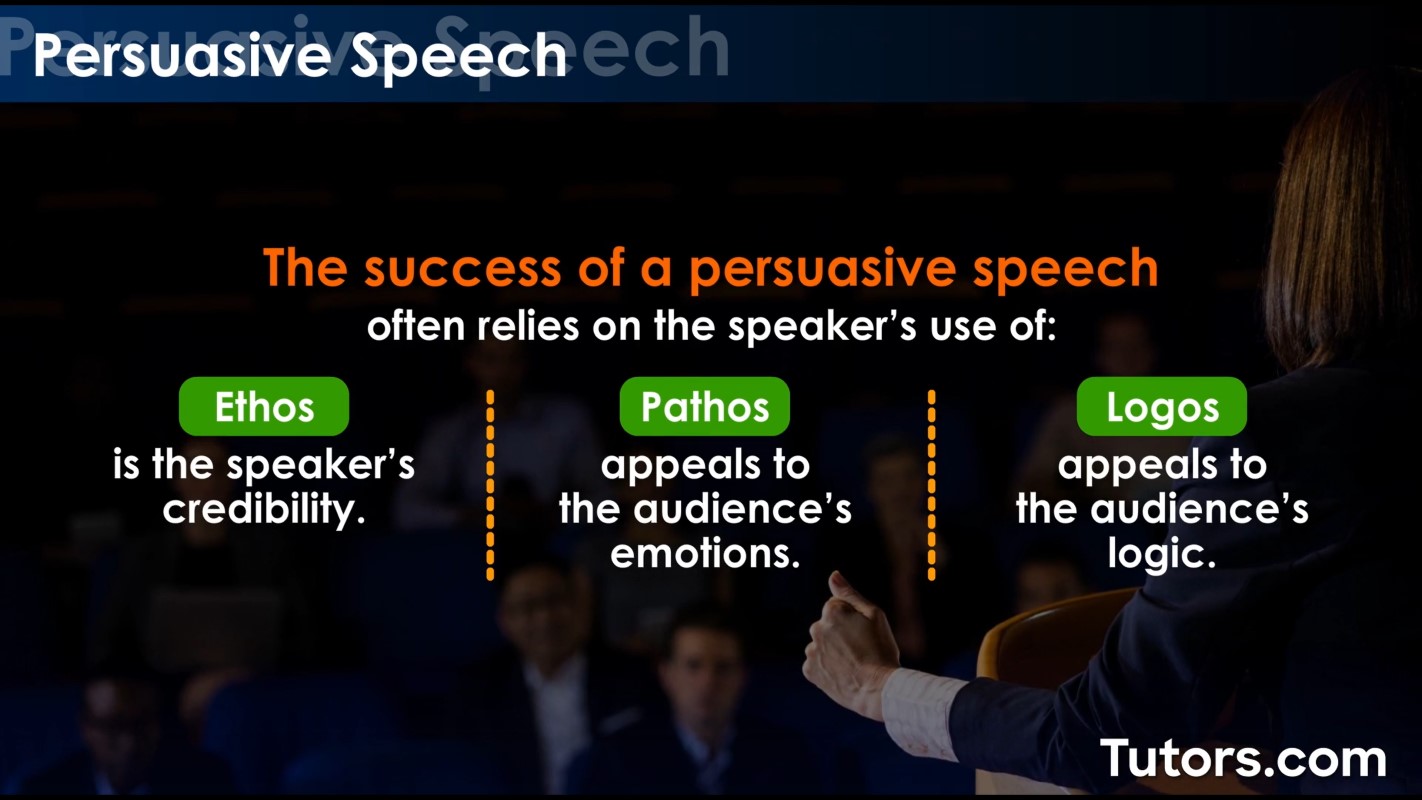

You are used to experiencing persuasion in many forms, and may have an easy time identifying examples of persuasion , but can you explain how persuasion works? Osborn and Osborn (1997) define persuasion this way: “the art of convincing others to give favorable attention to our point of view” (p. 415). There are two components that make this definition a useful one. First, it acknowledges the artfulness, or skill, required to persuade others. Whether you are challenged with convincing an auditorium of 500 that they should sell their cars and opt for a pedestrian lifestyle or with convincing your friends to eat pizza instead of hamburgers, persuasion does not normally just happen. Rather it is planned and executed in a thoughtful manner. Second, this definition delineates the ends of persuasion—to convince others to think favorably of our point of view. Persuasion “encompasses a wide range of communication activities, including advertising, marketing, sales, political campaigns, and interpersonal relations” (German, Gronbeck, Ehninger, & Monroe, 2004, p. 242). Because of its widespread utility, persuasion is a pervasive part of our everyday lives.

Although persuasion occurs in nearly every facet of our day-to-day lives, there are occasions when more formal acts of persuasion—persuasive speeches—are appropriate. Persuasive speeches “intend to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, and acts of others” (O’Hair & Stewart, 1999, p. 337). Unlike an informative speech, where the speaker is charged with making some information known to an audience, in a persuasive speech the speaker attempts to influence people to think or behave in a particular way. This art of convincing others is propelled by reasoned argument, the cornerstone of persuasive speeches. Reasoned arguments, which might consist of facts, statistics, personal testimonies, or narratives, are employed to motivate audiences to think or behave differently than before they heard the speech.

There are particular circumstances that warrant a persuasive approach. As O’Hair and Stewart point out, it makes sense to engage strategies of persuasion when your end goal is to influence any of these things—“beliefs, attitudes, values, and acts”—or to reinforce something that already exists. For instance, safe sex advocates often present messages of reinforcement to already safe sexual actors, reminding them that wearing condoms and asking for consent are solid practices with desirable outcomes. By the same token, safer sex advocates also routinely spread the message to populations who might be likely to engage in unsafe or nonconsensual sexual behavior.

In a nutshell, persuasive speeches must confront the complex challenge of influencing or reinforcing peoples’ beliefs, attitudes, values, or actions, all characteristics that may seem natural, ingrained, or unchangeable to an audience. Because of this, rhetors (or speakers) must motivate their audiences to think or behave differently by presenting reasoned arguments.

The triumph of persuasion over force is the sign of a civilized society. ~ Mark Skousen

Machiavellian Mastery

Strategies and Tactics for a World of Power Plays

- 22 min read

The Fine Line Between Persuasion and Manipulation: Ethics in Influence

Table of Contents

Understanding persuasion and manipulation.

1.1 Defining the Art of Persuasion

1.2 Manipulation: A Dark Reflection

1.3 Ethical Boundaries in Influence

Principles of Ethical Persuasion

2.1 Respect for Autonomy

2.2 Transparency in Communication

2.3 The Role of Empathy

Strategies for Ethical Influence

3.1 Building Trust and Credibility

3.2 Effective Listening and Feedback

3.3 Tailoring Messages for Positive Impact

Defining the Art of Persuasion

The Art of Persuasion has long been a subject of fascination and study throughout history. Its roots can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where it was essential in everything from politics to personal relationships. Understanding persuasion requires us to delve into its historical context and philosophical underpinnings, particularly through the lenses of Stoicism and Machiavellianism.

The Historical Context

The concept of persuasion is as old as human communication itself. In ancient Greece, it was the cornerstone of public life, epitomized by the rhetoricians of Athens. These early masters of persuasion understood the power of language and its ability to sway public opinion, change minds, and influence decisions. The sophists, often criticized for their perceived manipulation, were among the first to turn persuasion into an art, teaching public speaking as a tool for influence.

Fast forward to the Renaissance, and we encounter the emergence of Machiavellian principles. Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work, "The Prince," outlined strategies for gaining and maintaining power, many of which revolved around persuasive tactics. Machiavelli's work has often been synonymous with cunning and ruthless strategies, but at its core, it’s a study in the art of influence.

Stoicism and Persuasion

Stoicism, a philosophy founded in the Hellenistic period, offers a contrasting perspective to Machiavellianism. While Machiavelli focuses on the pragmatic aspects of influence, Stoicism, as taught by philosophers like Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, emphasizes ethics, self-control, and virtue. In Stoicism, persuasion is not just about influencing others; it's about doing so with integrity and for the right reasons.

The Stoic approach to persuasion is grounded in the concept of 'pithanon' – the believable or persuasive. Unlike the Machiavellian approach, which may utilize deceit or manipulation, Stoicism advocates for persuasion through logical argumentation, moral integrity, and the demonstration of virtuous character. The Stoic persuader is someone who leads by example, embodying the virtues they espouse and influencing others through the power of their character and reasoning.

Machiavellian Influence

In contrast, Machiavellianism views persuasion as a tool for achieving one’s ends, often disregarding moral considerations. The Machiavellian persuader is pragmatic, focusing on the effectiveness of their techniques rather than their ethical implications. This approach involves understanding and sometimes manipulating the psychological and emotional states of others to achieve a desired outcome.

Machiavellian tactics in persuasion might include flattery, deceit, or strategic ambiguity. While these methods can be effective, they also pose significant ethical concerns. The challenge lies in balancing the effectiveness of these tactics with the potential moral costs.

Integrating Stoicism and Machiavellianism

The art of persuasion, then, becomes a dance between these two philosophies. On one hand, the Stoic commitment to virtue and integrity provides a moral compass, ensuring that persuasive efforts are grounded in ethical principles. On the other hand, the Machiavellian emphasis on strategy and pragmatism acknowledges the complex realities of human interactions and the necessity of sometimes employing less straightforward tactics.

In practice, effective persuasion involves understanding and navigating this balance. It requires the persuader to be aware of the ethical implications of their tactics while also being adept at the strategic aspects of influence. This blend of Stoic virtue and Machiavellian strategy creates a more holistic approach to persuasion – one that is effective yet mindful of its moral dimensions.

The art of persuasion is a complex interplay of historical context and philosophical thought. By drawing on the strengths of both Stoicism and Machiavellianism, one can develop a persuasive approach that is both effective and ethically sound. It is about understanding the power of influence and using it responsibly, respecting the autonomy and dignity of those we seek to persuade. In mastering this art, we find a powerful tool for leadership, negotiation, and personal growth – one that has stood the test of time and remains as relevant today as it was in the courts of ancient Greece or the halls of Renaissance power.

Manipulation: A Dark Reflection

Manipulation , often seen as the darker cousin of persuasion, is a contentious and ethically fraught aspect of human interaction. While persuasion is generally viewed through a lens of mutual respect and ethical communication, manipulation involves influencing others to one's advantage, often at the expense of their autonomy and wellbeing. This section explores manipulation from both psychological and ethical viewpoints, contrasting it with the art of persuasion.

Psychological Underpinnings of Manipulation

From a psychological standpoint, manipulation involves exploiting cognitive, emotional, or relational vulnerabilities. Manipulators are adept at reading people and understanding their desires and fears. They use this knowledge to create scenarios where the manipulated individual feels compelled to act in a way that serves the manipulator's agenda.

Key psychological tactics of manipulation include:

Emotional Exploitation : Playing on emotions such as fear, guilt, or love to control others' behavior.

Gaslighting : Making someone doubt their reality or sanity to gain the upper hand.

Deception and Lies : Deliberately misrepresenting facts to mislead or confuse.

In contrast to persuasion, which seeks to respect and empower the decision-making process of the other party, manipulation often leaves the manipulated feeling disempowered, confused, or even violated. While persuasive tactics can be transparent and consensual, manipulative tactics are typically covert and non-consensual.

Ethical Implications of Manipulation

Ethically, manipulation is generally considered reprehensible because it violates the principle of respect for persons. This principle, deeply rooted in various ethical systems, including Stoicism and Kantian ethics, posits that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents capable of making their own decisions, not merely as means to an end.

Manipulation, by its very nature, undermines this principle. It treats people as tools for achieving the manipulator’s objectives, disregarding their autonomy, dignity, and rights. This ethical violation is starkly contrasted with the art of persuasion, which seeks to engage with individuals' rationality and freedom, allowing them to make informed choices.

The Thin Line Between Persuasion and Manipulation

The distinction between persuasion and manipulation can sometimes be subtle. Both involve influencing others, but the key difference lies in the intent and methods used. Persuasive tactics are anchored in respect, consent, and often, mutual benefit. Manipulative tactics, however, are self-serving, exploit vulnerabilities, and often result in harm or loss of autonomy for the manipulated.

For instance, a persuasive argument in a negotiation respects the other party's capacity to reason and decide, presenting facts and logical reasoning. In contrast, a manipulative tactic in the same situation might involve misleading information or playing on the other party's insecurities to force a decision.

Navigating the Ethical Landscape

Understanding and avoiding manipulation requires a strong ethical compass and self-awareness. It involves:

Recognizing Vulnerabilities : Being aware of the vulnerabilities in others and consciously choosing not to exploit them.

Self-Reflection : Regularly reflecting on one's motives and methods of influence.

Seeking Consent and Understanding : Ensuring that the other party is fully informed and consensually involved in any decision-making process.

Manipulation, when contrasted with the ethical and respectful approach of persuasion, emerges as a fundamentally exploitative and harmful practice. It not only damages relationships but also undermines the moral fabric of interpersonal interactions. The challenge for anyone interested in the art of influence is to navigate this landscape with a clear ethical compass, ensuring that their methods of persuasion remain respectful, transparent, and grounded in the dignity of those they interact with. In doing so, they uphold not just the effectiveness of their influence but also its moral integrity.

Ethical Boundaries in Influence

In the realm of influence, the line between ethical persuasion and unethical manipulation can be surprisingly thin and often blurred. Understanding and respecting this boundary is crucial for anyone who seeks to influence others while maintaining moral integrity. This section explores the ethical boundaries that distinguish persuasive communication from manipulative tactics.

The Spectrum of Influence

Influence, in its broadest sense, spans a spectrum. On one end, there is ethical persuasion, characterized by respect, transparency, and the aim of mutual benefit. On the other end lies manipulation, marked by deceit, coercion, and self-interest. Between these two extremes, there are numerous shades of influence, each with varying degrees of ethical acceptability.

Principles Guiding Ethical Influence

Respect for Autonomy : Ethical persuasion respects the decision-making freedom of the other party. It involves providing information and arguments that allow individuals to make informed choices based on their values and interests.

Transparency and Honesty : Ethical influencers are transparent about their intentions and honest in their communication. They do not resort to deceit or misleading information to sway others.

Non-Coercion : Persuasion is non-coercive. It does not involve force or threats, either explicit or implicit. Instead, it appeals to reason and emotion in a way that respects the other’s ability to accept or reject the message.

Beneficence : Ethical persuasion considers the interests and wellbeing of the other party. It seeks not only the fulfillment of one's own objectives but also the benefit, or at least the non-harm, of the others involved.

The Slippery Slope to Manipulation

The transition from persuasion to manipulation can be gradual and not always apparent. Certain tactics, while not overtly manipulative, can start to encroach upon ethical boundaries. For instance, persuasive techniques that overly play on emotions, while not necessarily unethical, can become manipulative when they exploit emotional vulnerabilities or create undue fear or stress.

Similarly, the use of persuasive "nudges" based on behavioral science is ethical when it guides people towards beneficial choices but can become manipulative if used to exploit cognitive biases for selfish ends.

Recognizing and Avoiding Unethical Influence

To maintain ethical integrity in influence, it is important to:

Self-reflect : Regularly examine one's motives and methods of influence. Ask whether the tactics being used respect the autonomy and wellbeing of others.

Seek Feedback : Engage in open dialogue and seek feedback about one's approach to influence. This can help identify any unintentional drift towards manipulative tactics.

Educate Oneself : Stay informed about ethical standards and best practices in influence. This includes understanding the psychological aspects of influence and the potential for unethical manipulation.

The art of influence requires not only skill but also a strong ethical foundation. The fine line between persuasion and manipulation is navigated successfully by those who are self-aware, transparent, and committed to respecting the autonomy and wellbeing of others. By adhering to these ethical boundaries, influencers can ensure that their impact is not only effective but also morally sound, fostering trust and integrity in all their interactions.

Affiliate Ad: "Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" by Robert B. Cialdini

Are you ready to unlock the secrets of persuasion and influence? Look no further than "Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" by Robert B. Cialdini.

In this groundbreaking book, Cialdini delves into the fascinating world of human psychology and reveals the six universal principles of influence that can help you ethically master the art of persuasion. Whether you're a marketer, salesperson, or simply someone looking to enhance your communication skills, this book is a must-read.

Discover how to harness the power of reciprocity, scarcity, authority, consistency, liking, and social proof to make a lasting impact on others. Cialdini's research-backed insights and real-life examples will equip you with the knowledge and strategies you need to navigate the fine line between persuasion and manipulation.

"Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" has become a classic in the field, trusted by professionals and individuals alike. Join the thousands who have already benefited from Cialdini's expertise and take your influence to the next level.

Don't miss out on this opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the psychology behind persuasive communication. Grab your copy of "Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" today and unlock your true influence potential!

Click here to get your copy of "Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion" by Robert B. Cialdini

(Note: This is an affiliate ad. We may receive a commission for purchases made through this link.)

Respect for Autonomy

In the sphere of influence and persuasion, respecting autonomy is paramount. It forms the bedrock of ethical interaction and is essential for maintaining the integrity of both the influencer and the influenced. This section delves into why respecting individual freedom and choice is not just an ethical imperative but a cornerstone of effective and sustainable influence.

Autonomy as a Fundamental Ethical Principle

Autonomy, derived from the Greek words 'auto' (self) and 'nomos' (law), refers to the right of individuals to make their own choices and govern themselves. This principle is deeply embedded in ethical theories ranging from Kantian ethics, which views autonomy as the basis of human dignity, to contemporary moral and political philosophies that advocate for personal freedom and self-determination.

In the context of persuasion, respecting autonomy means recognizing and upholding the right of others to make their own decisions, even if those decisions do not align with the influencer's objectives.

The Role of Autonomy in Persuasion

Empowering Decision-Making : Ethical persuasion empowers the audience to make informed decisions. This involves providing complete and accurate information, clarifying potential misconceptions, and avoiding tactics that might cloud judgment.

Building Trust : Respect for autonomy is fundamental to building and maintaining trust. When individuals feel that their autonomy is respected, they are more likely to engage openly and honestly, fostering a relationship of mutual respect and credibility.

Avoiding Backlash : Tactics that violate autonomy, such as coercion or deception, may yield short-term compliance but often lead to long-term resistance and distrust. In contrast, respectful persuasion encourages positive and sustainable relationships.

Implementing Respect for Autonomy

To genuinely respect autonomy in persuasive efforts, one must:

Encourage Critical Thinking : Rather than just presenting a preferred viewpoint, encourage the audience to think critically about the information, weigh different perspectives, and arrive at their own conclusions.

Avoid Manipulative Tactics : Steer clear of tactics that exploit cognitive biases, emotional vulnerabilities, or misinformation. Instead, focus on honest, logical, and empathetic communication.

Acknowledge the Right to Disagree : Accept that the audience may not always be persuaded and that this is a fundamental aspect of their autonomy. Respectful disagreement is a hallmark of ethical persuasion.

Ethical Boundaries and Personal Responsibility

Respecting autonomy also involves understanding and acknowledging one's own ethical boundaries. It requires a high degree of self-awareness and a commitment to personal responsibility. Influencers should continuously evaluate their tactics and motivations, ensuring that they align with the principle of respect for autonomy.

Respecting autonomy in persuasion is not merely a moral obligation but a vital component of effective and ethical influence. It fosters trust, encourages healthy decision-making, and upholds the dignity and rights of individuals. By prioritizing autonomy, influencers can create a more open, honest, and sustainable environment for communication and change. This respect not only enhances the quality of the influence exerted but also contributes to a more ethically sound and respectful society.

Transparency in Communication

In the realm of influence and persuasion, transparency in communication is pivotal. It is the practice of being open, honest, and clear in messaging, ensuring that the audience has all the necessary information to make informed decisions. This section emphasizes the significance of transparency in building trust, maintaining ethical standards, and enhancing the effectiveness of persuasive efforts.

The Essence of Transparency

Transparency is more than just not lying; it's about proactively ensuring that your audience understands your intentions, the information provided, and the implications of their choices. It involves a commitment to clarity, openness, and honesty in all aspects of communication.

Why Transparency Matters

Building Trust : Transparent communication is foundational to building and maintaining trust. When audiences know that they are receiving the full picture, their trust in the communicator grows, leading to stronger, more sustainable relationships.

Ethical Integrity : Transparency is a key component of ethical persuasion. It respects the audience's right to make informed decisions and avoids the ethical pitfalls associated with deceptive or manipulative tactics.

Long-term Effectiveness : While less transparent tactics might yield short-term gains, transparency ensures long-term effectiveness. Audiences are more likely to engage, respond positively, and remain loyal when they feel they are being communicated with honestly.

Implementing Transparency in Communication

To practice transparency in persuasive efforts, one must:

Disclose Intentions : Be upfront about your objectives in the communication. If you have something to gain, make it known.

Provide Complete Information : Ensure that the information provided is comprehensive and accurate. Avoid withholding critical details that could affect the audience's decision-making.

Clarify and Simplify : Avoid using overly complex or technical language that might obscure the message. Aim for clarity and simplicity to ensure the audience fully understands the communication.

Acknowledge Limitations and Biases : Be open about any limitations in your knowledge or potential biases in your perspective. This honesty contributes to the credibility of your message.

Challenges in Practicing Transparency

While the concept of transparency is straightforward, its application can be challenging. In complex or sensitive situations, it can be tempting to withhold information or present it in a way that's more favorable to a particular outcome. However, even in these cases, maintaining transparency is crucial for ethical persuasion.

Transparency and Authenticity

Transparency goes hand in hand with authenticity. Being authentic in your communication means that your words align with your true beliefs and intentions. It's about being genuine and real, which audiences can sense and appreciate. This authenticity builds a deeper connection with your audience, enhancing the impact of your persuasion.

Transparency in communication is not just an ethical imperative but a strategic one. By advocating for honesty and clarity, influencers can build trust, maintain ethical integrity, and enhance the long-term effectiveness of their persuasive efforts. Transparent communication fosters a more informed, engaged, and respectful audience, creating a foundation for positive and lasting influence. In an age where misinformation can be rampant, committing to transparency is both a moral duty and a path to more meaningful and impactful communication.

The Role of Empathy

Empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, is a fundamental element of ethical persuasion. It goes beyond mere sympathy or compassion, involving a deeper connection and comprehension of another person's perspective and emotional state. In the context of persuasion, empathy plays a crucial role in ensuring that communication is not only effective but also respectful and morally sound.

Understanding Empathy in Persuasion

Empathy in persuasion is about genuinely understanding the audience's feelings, needs, and viewpoints. It involves actively listening and putting oneself in their shoes to appreciate their experiences and concerns fully. This empathetic understanding is vital for tailoring communication in a way that resonates with the audience and addresses their specific needs and values.

Why Empathy Matters

Building Genuine Connections : Empathy allows persuaders to build deeper, more genuine connections with their audience. These connections foster trust and openness, making communication more effective.

Enhancing Ethical Engagement : When a persuader empathizes with their audience, they are more likely to consider the ethical implications of their influence. This consideration ensures that the persuasive tactics employed are respectful and considerate of the audience's wellbeing.

Improving Communication Effectiveness : Understanding the audience's perspective enables the development of messages that are more relevant, appealing, and persuasive to them. It ensures that the communication is not just a one-way transmission but a meaningful interaction.

Practicing Empathy in Persuasion

To effectively incorporate empathy into persuasive efforts, one must:

Active Listening : This involves not just hearing but attentively listening to understand. It means paying attention to both the spoken words and the unspoken emotions or thoughts.

Asking and Reflecting : Asking questions to gain deeper insight into the audience's perspective and reflecting back what is understood to ensure clarity and show that their views are being genuinely considered.

Adjusting Communication : Using the insights gained from empathetic engagement to tailor messages in a way that acknowledges and addresses the audience’s concerns and values.

Empathy and Ethical Boundaries

Empathy plays a critical role in maintaining ethical boundaries in persuasion. It acts as a check against manipulative tactics, reminding the persuader to consider the impact of their influence on the audience's emotional and psychological wellbeing. By practicing empathy, persuaders are more likely to avoid approaches that could be perceived as coercive or deceptive.

The Challenge of Empathetic Persuasion

While empathy is undoubtedly beneficial, it also presents challenges. It requires patience, effort, and a genuine willingness to understand others, which can be demanding, especially in contentious or emotionally charged situations. However, the effort to practice empathy in persuasion is a worthwhile investment, leading to more ethical, effective, and meaningful interactions.

The role of empathy in ethical persuasion cannot be overstated. It is a key ingredient in building trust, maintaining ethical standards, and enhancing the effectiveness of communication. By striving to understand and connect with their audience's perspectives and emotions, ethical persuaders can ensure that their influence is not only powerful but also respectful and beneficial. Empathy, therefore, is not just a tool for better persuasion; it is a cornerstone of responsible and ethical interpersonal engagement.

Affiliate Ad: "Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ" by Daniel Goleman

Are you ready to unlock the power of emotional intelligence and enhance your ability to connect with others? Look no further than "Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ" by Daniel Goleman.

In this groundbreaking book, Goleman explores the concept of emotional intelligence and its profound impact on our personal and professional lives. Drawing on cutting-edge research and real-life examples, he reveals how emotional intelligence can be a more accurate predictor of success than traditional measures like IQ.

Discover how to develop self-awareness, manage emotions effectively, empathize with others, and build strong relationships. Goleman's insights and practical strategies will empower you to navigate social dynamics, make better decisions, and thrive in today's complex world.

Whether you're a leader, a team member, or simply someone seeking personal growth, "Emotional Intelligence" provides a roadmap for cultivating this essential skill. Gain a deeper understanding of yourself and others, improve your communication and influence, and create a positive and harmonious environment.

"Influencer: The Power of Emotional Intelligence" is a must-read for anyone who wants to unlock their full potential and cultivate meaningful connections. Don't miss out on this opportunity to enhance your emotional intelligence and transform your life.

Click here to get your copy of "Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ" by Daniel Goleman

Building Trust and Credibility

In the art of persuasion, trust and credibility are invaluable assets. They are the foundation upon which effective and ethical influence is built. Establishing oneself as a trustworthy influencer involves a consistent commitment to integrity, competence, and reliability. This section offers practical tips for cultivating trust and credibility in your role as an influencer.

Demonstrating Integrity

Consistency in Words and Actions : Ensure that your actions align with your words. Consistency breeds predictability, which in turn fosters trust. Inconsistencies between what you say and do can rapidly erode trust.

Honesty and Transparency : Be open and honest in your communications. Admit when you don’t have all the answers and avoid misleading or deceptive tactics. Transparency about your intentions and limitations builds trust.

Ethical Standards : Adhere to high ethical standards in all your interactions. This includes respecting the autonomy and dignity of others, ensuring fairness, and avoiding exploitation.

Showcasing Competence

Knowledge and Expertise : Continuously build and demonstrate your knowledge and expertise in your field. This not only enhances your persuasiveness but also establishes you as a credible source of information.

Evidence-Based Arguments : Use facts, data, and logical reasoning in your persuasive efforts. Providing evidence for your claims reinforces your credibility.

Continuous Learning : Stay updated with the latest developments in your field. Being well-informed reflects your commitment to your area of influence and contributes to your credibility.

Building Reliability

Follow Through on Commitments : When you make promises or commitments, ensure you follow through. Reliability in fulfilling your promises is a key component of trust.

Consistent Availability : Be accessible and responsive to your audience. Consistency in your availability helps build a reliable image.

Constructive Engagement : Regularly engage with your audience in a constructive manner. Listen to their concerns, address their questions, and provide valuable insights.

Fostering Emotional Connections

Empathy and Understanding : Show genuine interest and understanding of your audience’s needs and concerns. Empathy helps in building a deeper, more meaningful connection.

Authenticity : Be yourself. Authenticity in your interactions makes you more relatable and trustworthy.

Positive Reinforcement : Acknowledge and appreciate the positive aspects of your interactions. Positive reinforcement can foster goodwill and trust.

Handling Mistakes and Criticism

Admit and Learn from Mistakes : If you make a mistake, own up to it and take steps to rectify it. Showing accountability can actually increase trust.

Respond to Criticism Constructively : Address criticism in a thoughtful and constructive manner. Defensive or aggressive responses can damage trust and credibility.

Building trust and credibility is a gradual process that requires consistency, integrity, competence, and a genuine connection with your audience. By following these tips and committing to ethical principles of persuasion, you can establish yourself as a trustworthy influencer. Trust and credibility not only enhance the effectiveness of your influence but also ensure that your impact is positive, ethical, and enduring.

Affiliate Ad: "The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything" by Stephen M.R. Covey

Are you ready to unlock the power of trust and transform your personal and professional relationships? Look no further than "The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything" by Stephen M.R. Covey.

In this groundbreaking book, Covey delves into the profound impact that trust has on every aspect of our lives. Drawing on real-life examples and extensive research, he reveals the key principles and practices that can help you build and maintain trust in all your interactions.

Discover how trust affects productivity, profitability, and overall success. Covey's insights and practical strategies will empower you to navigate the complexities of trust, foster stronger relationships, and achieve remarkable results.

Whether you're a leader, an entrepreneur, or simply someone looking to enhance your personal relationships, this book is a must-read. Learn how to create a culture of trust, develop credibility, and inspire others to trust you.

"The Speed of Trust" has become a global phenomenon, trusted by individuals and organizations alike. Join the millions who have already benefited from Covey's expertise and take your relationships to the next level.

Don't miss out on this opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the power of trust.

Grab your copy of "The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything" today and unlock the true potential of trust!

Click here to get your copy of "The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything" by Stephen M.R. Covey

Effective Listening and Feedback

Effective listening and constructive feedback are pivotal skills for any influencer or leader. They are not just about hearing words or providing input but involve a deeper level of engagement and understanding. Active listening and constructive feedback create a two-way street in communication, fostering mutual respect and trust. This section explores techniques for honing these essential skills.

Techniques for Active Listening

Full Attention : Give your undivided attention to the speaker. This means putting aside distractions, whether physical (like a phone) or mental (like your own thoughts or responses).

Non-Verbal Cues : Use body language to show attentiveness. Nodding, maintaining eye contact, and leaning forward slightly can all convey that you are fully engaged.

Reflective Listening : Reflect what has been said by paraphrasing. This shows that you are not just hearing, but also understanding. For example, "So, what you're saying is…"

Clarifying Questions : Ask open-ended questions to clarify points and dig deeper. This demonstrates your interest in fully understanding their perspective.

Avoiding Interruption : Resist the urge to interrupt or finish sentences. Allow the speaker to express their thoughts completely before responding.

Empathizing : Try to understand the speaker’s emotions and viewpoints. Empathy in listening helps in building a stronger connection and understanding.

Techniques for Constructive Feedback

Specificity : Be specific in your feedback. Avoid vague comments and focus on particular aspects that can be addressed or improved.

Balance : Strive for a balance between positive reinforcement and constructive criticism. This approach is often more motivating and less threatening.

I-Statements : Use “I” statements to express your thoughts and feelings about the situation, rather than “you” statements which can come across as accusatory. For example, "I feel that…"

Focus on Behavior, Not Personality : Direct your feedback towards behavior and actions rather than personal traits. This makes it easier for the person to accept and act on the feedback.

Timeliness : Provide feedback as close to the event as possible. Delayed feedback can lose its relevance and impact.

Actionable Suggestions : Offer clear, actionable suggestions for improvement. Feedback is more useful when it provides a direction for change.

Encourage Self-Reflection : Prompt the person to reflect on their actions and behavior. Questions like “How do you feel about…” or “What do you think could be done differently?” encourage self-assessment.

The Role of Active Listening and Feedback in Persuasion

In the context of persuasion, active listening and constructive feedback are not just about improving communication; they are about building a relationship based on respect and mutual understanding. Active listening shows that you value the other person’s perspective, while constructive feedback helps in fostering growth and development. Both these skills are critical in creating an environment where ethical persuasion can thrive.

Mastering the art of active listening and constructive feedback is essential for anyone in a position of influence. These skills not only enhance communication but also contribute to building a foundation of trust and respect. By practicing effective listening and offering thoughtful feedback, influencers can foster more meaningful, productive, and positive interactions. These interactions, in turn, pave the way for more effective and ethical persuasion.

Tailoring Messages for Positive Impact :

Effective communication is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. To truly resonate and create a positive impact, messages need to be tailored to the specific audience they are intended for. This customization involves understanding the unique characteristics, needs, and preferences of different audience segments and adapting your communication accordingly. This section offers guidance on how to effectively tailor messages for various audiences.

Understanding Your Audience

Demographic Factors : Consider age, gender, occupation, education level, and cultural background. These factors can influence how people perceive and process information.

Psychographic Characteristics : Understand the audience's values, beliefs, attitudes, and interests. Aligning your message with these elements can make it more relatable and persuasive.

Communication Preferences : Identify the preferred communication channels and styles of your audience. Some may respond better to visual aids, while others might prefer detailed text or interactive formats.

Level of Knowledge : Assess the audience's existing knowledge about the topic. This helps in determining the complexity of the message and the need for background information.

Customizing the Message

Language and Tone : Adjust the language and tone to suit the audience. For a professional audience, a formal tone might be appropriate, whereas a casual tone could work better for a younger audience.

Relevant Examples and Analogies : Use examples, stories, or analogies that the audience can relate to. This makes abstract concepts more concrete and understandable.

Highlighting Benefits : Emphasize the aspects of your message that are most relevant and beneficial to the audience. For example, focus on cost-saving for a business audience, or convenience for busy parents.

Visual and Interactive Elements : Incorporate visual aids or interactive elements if they are effective with your audience. Infographics, videos, and interactive presentations can enhance engagement.

Feedback and Adaptation

Gather Feedback : Collect feedback on your communication efforts to understand what works and what doesn’t. This can be done through surveys, comments, or direct conversations.

Be Flexible and Adaptive : Be prepared to adjust your approach based on feedback and changing circumstances. Flexibility is key in effective communication.

Continuous Learning : Continuously learn about your audience. As their needs and preferences evolve, so should your communication strategies.

Ethical Considerations

While tailoring messages, it's crucial to maintain ethical standards. Ensure that the customization does not compromise the truthfulness or integrity of the message. Avoid stereotyping or making assumptions about the audience that could lead to miscommunication or offense.

Tailoring messages for different audiences is an art that requires careful consideration of various factors that influence how messages are received and interpreted. By understanding and adapting to the unique characteristics of your audience, you can ensure that your communication is not only effective but also has a positive and lasting impact. This tailored approach is essential for anyone looking to engage, persuade, or influence diverse groups effectively and ethically.

Affiliate Ad: "Just Listen: Discover the Secret to Getting Through to Absolutely Anyone" by Mark Goulston

Are you ready to unlock the power of effective communication and build deeper connections with others? Look no further than "Just Listen: Discover the Secret to Getting Through to Absolutely Anyone" by Mark Goulston.

In this compelling book, Goulston reveals the secrets to becoming a master listener and communicator. Drawing on his extensive experience as a psychiatrist and business coach, he shares practical techniques for breaking down barriers, defusing conflicts, and truly understanding others.

Discover how to listen with empathy, ask the right questions, and create genuine connections. Goulston's insights and real-life examples will empower you to navigate challenging conversations, build trust, and influence others positively.

Whether you're a leader, a salesperson, or simply someone seeking to enhance your personal relationships, "Just Listen" provides a roadmap for improving your communication skills. Gain a deeper understanding of others, resolve conflicts effectively, and create meaningful and lasting connections.

"Influencer: The Power of Effective Listening" is a must-read for anyone who wants to unlock their full communication potential and become a more influential and empathetic communicator. Don't miss out on this opportunity to transform your relationships and make a positive impact.

Click here to get your copy of "Just Listen: Discover the Secret to Getting Through to Absolutely Anyone" by Mark Goulston

In the intricate dance of influence and persuasion, the journey we've undertaken in exploring its various aspects reveals a landscape rich with opportunities and fraught with ethical considerations. From understanding the delicate interplay between persuasion and manipulation to respecting individual autonomy and the crucial role of transparency and empathy, each facet contributes to a comprehensive framework for ethical influence.

The art of persuasion, when practiced with integrity and respect for the autonomy of others, transcends mere communication. It becomes a tool for positive change, fostering connections based on trust, understanding, and mutual respect. By prioritizing honesty in our messaging and tailoring our communication to the unique needs and perspectives of our audience, we not only enhance our effectiveness as influencers but also uphold our ethical obligations.

In conclusion, the essence of ethical persuasion lies in its dual commitment to effectiveness and morality. It challenges us to be self-aware, continuously reflective, and committed to the higher principles of respect, transparency, and empathy. As we navigate the complexities of influence in our various roles – whether as leaders, marketers, educators, or advocates – let us carry forward the lessons of ethical persuasion. Let us strive to influence not just with the goal of achieving our objectives, but with the vision of creating a more understanding, respectful, and ethically conscious world.

In this endeavor, the journey does not end with the mastery of techniques; it evolves into a lifelong pursuit of balancing our aspirations with our ethical compass. May we all continue to grow, learn, and influence with a heart guided by integrity and a mind keen on making a positive impact.

Affiliate Ad: "How to Win Friends and Influence People" by Dale Carnegie

Looking to enhance your influence and build strong, lasting relationships? Look no further than "How to Win Friends and Influence People" by Dale Carnegie.

In this timeless classic, Carnegie shares practical advice and strategies for effectively connecting with others and influencing them ethically. Whether you're a business professional, a leader, or simply someone seeking to improve your interpersonal skills, this book is a must-read.

Discover the power of genuine listening, sincere appreciation, and the art of making others feel important. Carnegie's insights and real-life examples will equip you with the tools you need to navigate social interactions, win people over, and inspire positive change.

"How to Win Friends and Influence People" has stood the test of time, empowering millions of readers worldwide with its timeless wisdom. Join the ranks of successful influencers and take your interpersonal relationships to new heights.

Don't miss out on this opportunity to learn from one of the most influential books ever written. Grab your copy of "How to Win Friends and Influence People" by Dale Carnegie today and unlock your true influence potential!

Click here to get your copy of "How to Win Friends and Influence People" by Dale Carnegie

Recent Posts

The Ethics of Machiavellianism: Striking the Right Balance

Unethical Tactics: The Fine Line Between Success and Corruption

Machiavellian Ethics: How Far is Too Far?

Machiavellianism and Entrepreneurship: How to Outsmart Your Competitors

The Art of Persuasion in Customer Service: How to Turn Complaints into Opportunities

How to Use Machiavellian Principles for Personal Branding

The Power of Empathy in Persuasion and Influence

How to Master the Art of Persuasion in a Digital World

The Machiavellian Guide to Networking and Relationship Building

The Power of Persuasion in Marketing and Advertising

Lessons in Influence from History's Greatest Leaders

The Science and Art of Persuasion: How to Change Minds and Hearts

The Machiavellian Way: How to Thrive in a Competitive World

Join our mailing list

Thanks for subscribing!

.

, , , , .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Persuasive Speaking

Learning objectives.

- Explain how claims, evidence, and warrants function to create an argument.

- Identify strategies for choosing a persuasive speech topic.

- Identify strategies for adapting a persuasive speech based on an audience’s orientation to the proposition.

- Distinguish among propositions of fact, value, and policy.

- Choose an organizational pattern that is fitting for a persuasive speech topic.

We produce and receive persuasive messages daily, but we don’t often stop to think about how we make the arguments we do or the quality of the arguments that we receive. In this section, we’ll learn the components of an argument, how to choose a good persuasive speech topic, and how to adapt and organize a persuasive message.

Foundation of Persuasion

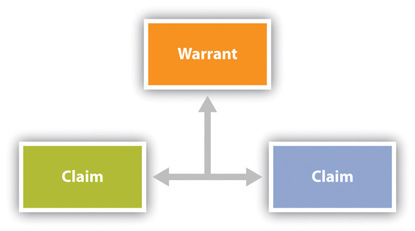

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis. Evidence , also called grounds, supports the claim. The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence. One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the US Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people shouldn’t do things they know are unsafe.

Figure 11.2 Components of an Argument

The quality of your evidence often impacts the strength of your warrant, and some warrants are stronger than others. A speaker could also provide evidence to support their claim advocating for a national ban on texting and driving by saying, “I have personally seen people almost wreck while trying to text.” While this type of evidence can also be persuasive, it provides a different type and strength of warrant since it is based on personal experience. In general, the anecdotal evidence from personal experience would be given a weaker warrant than the evidence from the national research report. The same process works in our legal system when a judge evaluates the connection between a claim and evidence. If someone steals my car, I could say to the police, “I’m pretty sure Mario did it because when I said hi to him on campus the other day, he didn’t say hi back, which proves he’s mad at me.” A judge faced with that evidence is unlikely to issue a warrant for Mario’s arrest. Fingerprint evidence from the steering wheel that has been matched with a suspect is much more likely to warrant arrest.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence. If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

As with any speech, topic selection is important and is influenced by many factors. Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial, and have important implications for society. If your topic is currently being discussed on television, in newspapers, in the lounges in your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s a current topic. A persuasive speech aimed at getting audience members to wear seat belts in cars wouldn’t have much current relevance, given that statistics consistently show that most people wear seat belts. Giving the same speech would have been much more timely in the 1970s when there was a huge movement to increase seat-belt use.

Many topics that are current are also controversial, which is what gets them attention by the media and citizens. Current and controversial topics will be more engaging for your audience. A persuasive speech to encourage audience members to donate blood or recycle wouldn’t be very controversial, since the benefits of both practices are widely agreed on. However, arguing that the restrictions on blood donation by men who have had sexual relations with men be lifted would be controversial. I must caution here that controversial is not the same as inflammatory. An inflammatory topic is one that evokes strong reactions from an audience for the sake of provoking a reaction. Being provocative for no good reason or choosing a topic that is extremist will damage your credibility and prevent you from achieving your speech goals.

You should also choose a topic that is important to you and to society as a whole. As we have already discussed in this book, our voices are powerful, as it is through communication that we participate and make change in society. Therefore we should take seriously opportunities to use our voices to speak publicly. Choosing a speech topic that has implications for society is probably a better application of your public speaking skills than choosing to persuade the audience that Lebron James is the best basketball player in the world or that Superman is a better hero than Spiderman. Although those topics may be very important to you, they don’t carry the same social weight as many other topics you could choose to discuss. Remember that speakers have ethical obligations to the audience and should take the opportunity to speak seriously.

You will also want to choose a topic that connects to your own interests and passions. If you are an education major, it might make more sense to do a persuasive speech about funding for public education than the death penalty. If there are hot-button issues for you that make you get fired up and veins bulge out in your neck, then it may be a good idea to avoid those when speaking in an academic or professional context.

Choose a persuasive speech topic that you’re passionate about but still able to approach and deliver in an ethical manner.

Michael Vadon – Nigel Farage – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Choosing such topics may interfere with your ability to deliver a speech in a competent and ethical manner. You want to care about your topic, but you also want to be able to approach it in a way that’s going to make people want to listen to you. Most people tune out speakers they perceive to be too ideologically entrenched and write them off as extremists or zealots.

You also want to ensure that your topic is actually persuasive. Draft your thesis statement as an “I believe” statement so your stance on an issue is clear. Also, think of your main points as reasons to support your thesis. Students end up with speeches that aren’t very persuasive in nature if they don’t think of their main points as reasons. Identifying arguments that counter your thesis is also a good exercise to help ensure your topic is persuasive. If you can clearly and easily identify a competing thesis statement and supporting reasons, then your topic and approach are arguable.

Review of Tips for Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

- Not current. People should use seat belts.

- Current. People should not text while driving.

- Not controversial. People should recycle.

- Controversial. Recycling should be mandatory by law.

- Not as impactful. Superman is the best superhero.

- Impactful. Colleges and universities should adopt zero-tolerance bullying policies.

- Unclear thesis. Homeschooling is common in the United States.

- Clear, argumentative thesis with stance. Homeschooling does not provide the same benefits of traditional education and should be strictly monitored and limited.

Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to directly influence the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important. If possible, poll your audience to find out their orientation toward your thesis. I read my students’ thesis statements aloud and have the class indicate whether they agree with, disagree with, or are neutral in regards to the proposition. It is unlikely that you will have a homogenous audience, meaning that there will probably be some who agree, some who disagree, and some who are neutral. So you may employ all of the following strategies, in varying degrees, in your persuasive speech.

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to further reinforce their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment so they are more likely to follow through on the action.

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral in regards to your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they don’t see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement.