50 Useful Academic Words & Phrases for Research

Like all good writing, writing an academic paper takes a certain level of skill to express your ideas and arguments in a way that is natural and that meets a level of academic sophistication. The terms, expressions, and phrases you use in your research paper must be of an appropriate level to be submitted to academic journals.

Therefore, authors need to know which verbs , nouns , and phrases to apply to create a paper that is not only easy to understand, but which conveys an understanding of academic conventions. Using the correct terminology and usage shows journal editors and fellow researchers that you are a competent writer and thinker, while using non-academic language might make them question your writing ability, as well as your critical reasoning skills.

What are academic words and phrases?

One way to understand what constitutes good academic writing is to read a lot of published research to find patterns of usage in different contexts. However, it may take an author countless hours of reading and might not be the most helpful advice when faced with an upcoming deadline on a manuscript draft.

Briefly, “academic” language includes terms, phrases, expressions, transitions, and sometimes symbols and abbreviations that help the pieces of an academic text fit together. When writing an academic text–whether it is a book report, annotated bibliography, research paper, research poster, lab report, research proposal, thesis, or manuscript for publication–authors must follow academic writing conventions. You can often find handy academic writing tips and guidelines by consulting the style manual of the text you are writing (i.e., APA Style , MLA Style , or Chicago Style ).

However, sometimes it can be helpful to have a list of academic words and expressions like the ones in this article to use as a “cheat sheet” for substituting the better term in a given context.

How to Choose the Best Academic Terms

You can think of writing “academically” as writing in a way that conveys one’s meaning effectively but concisely. For instance, while the term “take a look at” is a perfectly fine way to express an action in everyday English, a term like “analyze” would certainly be more suitable in most academic contexts. It takes up fewer words on the page and is used much more often in published academic papers.

You can use one handy guideline when choosing the most academic term: When faced with a choice between two different terms, use the Latinate version of the term. Here is a brief list of common verbs versus their academic counterparts:

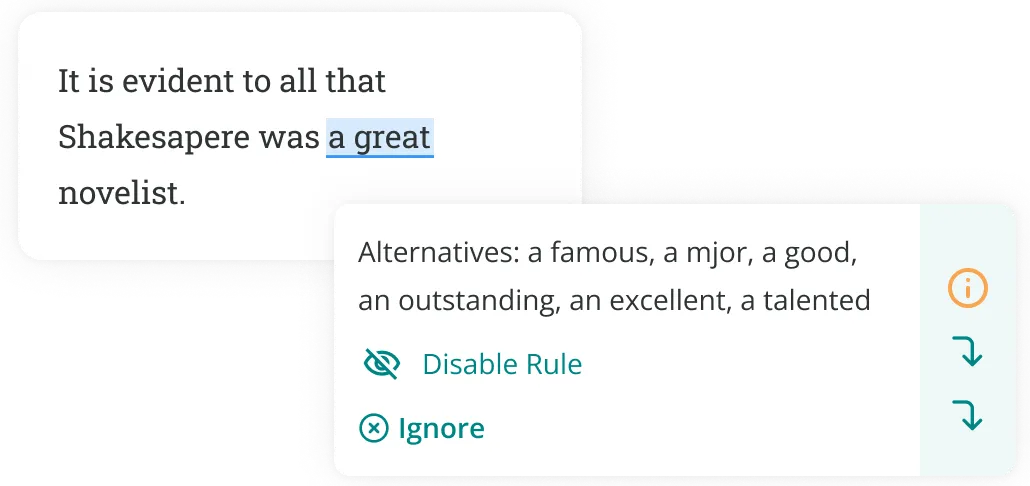

Although this can be a useful tip to help academic authors, it can be difficult to memorize dozens of Latinate verbs. Using an AI paraphrasing tool or proofreading tool can help you instantly find more appropriate academic terms, so consider using such revision tools while you draft to improve your writing.

Top 50 Words and Phrases for Different Sections in a Research Paper

The “Latinate verb rule” is just one tool in your arsenal of academic writing, and there are many more out there. But to make the process of finding academic language a bit easier for you, we have compiled a list of 50 vital academic words and phrases, divided into specific categories and use cases, each with an explanation and contextual example.

Best Words and Phrases to use in an Introduction section

1. historically.

An adverb used to indicate a time perspective, especially when describing the background of a given topic.

2. In recent years

A temporal marker emphasizing recent developments, often used at the very beginning of your Introduction section.

3. It is widely acknowledged that

A “form phrase” indicating a broad consensus among researchers and/or the general public. Often used in the literature review section to build upon a foundation of established scientific knowledge.

4. There has been growing interest in

Highlights increasing attention to a topic and tells the reader why your study might be important to this field of research.

5. Preliminary observations indicate

Shares early insights or findings while hedging on making any definitive conclusions. Modal verbs like may , might , and could are often used with this expression.

6. This study aims to

Describes the goal of the research and is a form phrase very often used in the research objective or even the hypothesis of a research paper .

7. Despite its significance

Highlights the importance of a matter that might be overlooked. It is also frequently used in the rationale of the study section to show how your study’s aim and scope build on previous studies.

8. While numerous studies have focused on

Indicates the existing body of work on a topic while pointing to the shortcomings of certain aspects of that research. Helps focus the reader on the question, “What is missing from our knowledge of this topic?” This is often used alongside the statement of the problem in research papers.

9. The purpose of this research is

A form phrase that directly states the aim of the study.

10. The question arises (about/whether)

Poses a query or research problem statement for the reader to acknowledge.

Best Words and Phrases for Clarifying Information

11. in other words.

Introduces a synopsis or the rephrasing of a statement for clarity. This is often used in the Discussion section statement to explain the implications of the study .

12. That is to say

Provides clarification, similar to “in other words.”

13. To put it simply

Simplifies a complex idea, often for a more general readership.

14. To clarify

Specifically indicates to the reader a direct elaboration of a previous point.

15. More specifically

Narrows down a general statement from a broader one. Often used in the Discussion section to clarify the meaning of a specific result.

16. To elaborate

Expands on a point made previously.

17. In detail

Indicates a deeper dive into information.

Points out specifics. Similar meaning to “specifically” or “especially.”

19. This means that

Explains implications and/or interprets the meaning of the Results section .

20. Moreover

Expands a prior point to a broader one that shows the greater context or wider argument.

Best Words and Phrases for Giving Examples

21. for instance.

Provides a specific case that fits into the point being made.

22. As an illustration

Demonstrates a point in full or in part.

23. To illustrate

Shows a clear picture of the point being made.

24. For example

Presents a particular instance. Same meaning as “for instance.”

25. Such as

Lists specifics that comprise a broader category or assertion being made.

26. Including

Offers examples as part of a larger list.

27. Notably

Adverb highlighting an important example. Similar meaning to “especially.”

28. Especially

Adverb that emphasizes a significant instance.

29. In particular

Draws attention to a specific point.

30. To name a few

Indicates examples than previously mentioned are about to be named.

Best Words and Phrases for Comparing and Contrasting

31. however.

Introduces a contrasting idea.

32. On the other hand

Highlights an alternative view or fact.

33. Conversely

Indicates an opposing or reversed idea to the one just mentioned.

34. Similarly

Shows likeness or parallels between two ideas, objects, or situations.

35. Likewise

Indicates agreement with a previous point.

36. In contrast

Draws a distinction between two points.

37. Nevertheless

Introduces a contrasting point, despite what has been said.

38. Whereas

Compares two distinct entities or ideas.

Indicates a contrast between two points.

Signals an unexpected contrast.

Best Words and Phrases to use in a Conclusion section

41. in conclusion.

Signifies the beginning of the closing argument.

42. To sum up

Offers a brief summary.

43. In summary

Signals a concise recap.

44. Ultimately

Reflects the final or main point.

45. Overall

Gives a general concluding statement.

Indicates a resulting conclusion.

Demonstrates a logical conclusion.

48. Therefore

Connects a cause and its effect.

49. It can be concluded that

Clearly states a conclusion derived from the data.

50. Taking everything into consideration

Reflects on all the discussed points before concluding.

Edit Your Research Terms and Phrases Before Submission

Using these phrases in the proper places in your research papers can enhance the clarity, flow, and persuasiveness of your writing, especially in the Introduction section and Discussion section, which together make up the majority of your paper’s text in most academic domains.

However, it's vital to ensure each phrase is contextually appropriate to avoid redundancy or misinterpretation. As mentioned at the top of this article, the best way to do this is to 1) use an AI text editor , free AI paraphrase tool or AI proofreading tool while you draft to enhance your writing, and 2) consult a professional proofreading service like Wordvice, which has human editors well versed in the terminology and conventions of the specific subject area of your academic documents.

For more detailed information on using AI tools to write a research paper and the best AI tools for research , check out the Wordvice AI Blog .

Related Words and Phrases

Bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250].

New Courses Open for Enrolment! Find Out More

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Effective Transition Words for Research Papers

What are transition words in academic writing?

A transition is a change from one idea to another idea in writing or speaking and can be achieved using transition terms or phrases. These transitions are usually placed at the beginning of sentences, independent clauses, and paragraphs and thus establish a specific relationship between ideas or groups of ideas. Transitions are used to enhance cohesion in your paper and make its logical development clearer to readers.

Types of Transition Words

Transitions accomplish many different objectives. We can divide all transitions into four basic categories:

- Additive transitions signal to the reader that you are adding or referencing information

- Adversative transitions indicate conflict or disagreement between pieces of information

- Causal transitions point to consequences and show cause-and-effect relationships

- Sequential transitions clarify the order and sequence of information and the overall structure of the paper

Additive Transitions

These terms signal that new information is being added (between both sentences and paragraphs), introduce or highlight information, refer to something that was just mentioned, add a similar situation, or identify certain information as important.

Adversative Transitions

These terms and phrases distinguish facts, arguments, and other information, whether by contrasting and showing differences; by conceding points or making counterarguments; by dismissing the importance of a fact or argument; or replacing and suggesting alternatives.

Causal Transitions

These terms and phrases signal the reasons, conditions, purposes, circumstances, and cause-and-effect relationships. These transitions often come after an important point in the research paper has been established or to explore hypothetical relationships or circumstances.

Sequential Transitions

These transition terms and phrases organize your paper by numerical sequence; by showing continuation in thought or action; by referring to previously-mentioned information; by indicating digressions; and, finally, by concluding and summing up your paper. Sequential transitions are essential to creating structure and helping the reader understand the logical development through your paper’s methods, results, and analysis.

How to Choose Transitions in Academic Writing

Transitions are commonplace elements in writing, but they are also powerful tools that can be abused or misapplied if one isn’t careful. Here are some ways to ensure you are using transitions effectively.

- Check for overused, awkward, or absent transitions during the paper editing process. Don’t spend too much time trying to find the “perfect” transition while writing the paper.

- When you find a suitable place where a transition could connect ideas, establish relationships, and make it easier for the reader to understand your point, use the list to find a suitable transition term or phrase.

- Similarly, if you have repeated some terms again and again, find a substitute transition from the list and use that instead. This will help vary your writing and enhance the communication of ideas.

- Read the beginning of each paragraph. Did you include a transition? If not, look at the information in that paragraph and the preceding paragraph and ask yourself: “How does this information connect?” Then locate the best transition from the list.

- Check the structure of your paper—are your ideas clearly laid out in order? You should be able to locate sequence terms such as “first,” “second,” “following this,” “another,” “in addition,” “finally,” “in conclusion,” etc. These terms will help outline your paper for the reader.

For more helpful information on academic writing and the journal publication process, visit Wordvice’s Academic Resources Page. And be sure to check out Wordvice’s professional English editing services if you are looking for paper editing and proofreading after composing your academic document.

Wordvice Tools

- Wordvice APA Citation Generator

- Wordvice MLA Citation Generator

- Wordvice Chicago Citation Generator

- Wordvice Vancouver Citation Generator

- Wordvice Plagiarism Checker

- Editing & Proofreading Guide

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write the Best Journal Submissions Cover Letter

- 100+ Strong Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- How to Write an Abstract

- Which Tense to Use in Your Abstract

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- Common Phrases Used in Academic Writing

Other Resources Around the Web

- MSU Writing Center. Transition Words.

- UW-Madison Writing Center. Transition Words and Phrases.

Word Choice

What this handout is about.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

Introduction

Writing is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts.

As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity.

For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts .

“Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choice

So: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly.

Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information.

Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues:

- Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.

Sometimes the problem isn’t choosing exactly the right word to express an idea—it’s being “wordy,” or using words that your reader may regard as “extra” or inefficient. Take a look at the following list for some examples. On the left are some phrases that use three, four, or more words where fewer will do; on the right are some shorter substitutes:

Keep an eye out for wordy constructions in your writing and see if you can replace them with more concise words or phrases.

In academic writing, it’s a good idea to limit your use of clichés. Clichés are catchy little phrases so frequently used that they have become trite, corny, or annoying. They are problematic because their overuse has diminished their impact and because they require several words where just one would do.

The main way to avoid clichés is first to recognize them and then to create shorter, fresher equivalents. Ask yourself if there is one word that means the same thing as the cliché. If there isn’t, can you use two or three words to state the idea your own way? Below you will see five common clichés, with some alternatives to their right. As a challenge, see how many alternatives you can create for the final two examples.

Try these yourself:

Writing for an academic audience

When you choose words to express your ideas, you have to think not only about what makes sense and sounds best to you, but what will make sense and sound best to your readers. Thinking about your audience and their expectations will help you make decisions about word choice.

Some writers think that academic audiences expect them to “sound smart” by using big or technical words. But the most important goal of academic writing is not to sound smart—it is to communicate an argument or information clearly and convincingly. It is true that academic writing has a certain style of its own and that you, as a student, are beginning to learn to read and write in that style. You may find yourself using words and grammatical constructions that you didn’t use in your high school writing. The danger is that if you consciously set out to “sound smart” and use words or structures that are very unfamiliar to you, you may produce sentences that your readers can’t understand.

When writing for your professors, think simplicity. Using simple words does not indicate simple thoughts. In an academic argument paper, what makes the thesis and argument sophisticated are the connections presented in simple, clear language.

Keep in mind, though, that simple and clear doesn’t necessarily mean casual. Most instructors will not be pleased if your paper looks like an instant message or an email to a friend. It’s usually best to avoid slang and colloquialisms. Take a look at this example and ask yourself how a professor would probably respond to it if it were the thesis statement of a paper: “Moulin Rouge really bit because the singing sucked and the costume colors were nasty, KWIM?”

Selecting and using key terms

When writing academic papers, it is often helpful to find key terms and use them within your paper as well as in your thesis. This section comments on the crucial difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and works through an example of using key terms in a thesis statement.

Repetition vs. redundancy

These two phenomena are not necessarily the same. Repetition can be a good thing. Sometimes we have to use our key terms several times within a paper, especially in topic sentences. Sometimes there is simply no substitute for the key terms, and selecting a weaker term as a synonym can do more harm than good. Repeating key terms emphasizes important points and signals to the reader that the argument is still being supported. This kind of repetition can give your paper cohesion and is done by conscious choice.

In contrast, if you find yourself frustrated, tiredly repeating the same nouns, verbs, or adjectives, or making the same point over and over, you are probably being redundant. In this case, you are swimming aimlessly around the same points because you have not decided what your argument really is or because you are truly fatigued and clarity escapes you. Refer to the “Strategies” section below for ideas on revising for redundancy.

Building clear thesis statements

Writing clear sentences is important throughout your writing. For the purposes of this handout, let’s focus on the thesis statement—one of the most important sentences in academic argument papers. You can apply these ideas to other sentences in your papers.

A common problem with writing good thesis statements is finding the words that best capture both the important elements and the significance of the essay’s argument. It is not always easy to condense several paragraphs or several pages into concise key terms that, when combined in one sentence, can effectively describe the argument.

However, taking the time to find the right words offers writers a significant edge. Concise and appropriate terms will help both the writer and the reader keep track of what the essay will show and how it will show it. Graders, in particular, like to see clearly stated thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements in general, please refer to our handout .)

Example : You’ve been assigned to write an essay that contrasts the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. You work on it for several days, producing three versions of your thesis:

Version 1 : There are many important river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn.

Version 2 : The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn suggest a return to nature.

Version 3 : Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

Let’s consider the word choice issues in these statements. In Version 1, the word “important”—like “interesting”—is both overused and vague; it suggests that the author has an opinion but gives very little indication about the framework of that opinion. As a result, your reader knows only that you’re going to talk about river and shore scenes, but not what you’re going to say. Version 2 is an improvement: the words “return to nature” give your reader a better idea where the paper is headed. On the other hand, they still do not know how this return to nature is crucial to your understanding of the novel.

Finally, you come up with Version 3, which is a stronger thesis because it offers a sophisticated argument and the key terms used to make this argument are clear. At least three key terms or concepts are evident: the contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

By itself, a key term is merely a topic—an element of the argument but not the argument itself. The argument, then, becomes clear to the reader through the way in which you combine key terms.

Strategies for successful word choice

- Be careful when using words you are unfamiliar with. Look at how they are used in context and check their dictionary definitions.

- Be careful when using the thesaurus. Each word listed as a synonym for the word you’re looking up may have its own unique connotations or shades of meaning. Use a dictionary to be sure the synonym you are considering really fits what you are trying to say.

- Under the present conditions of our society, marriage practices generally demonstrate a high degree of homogeneity.

- In our culture, people tend to marry others who are like themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- Before you revise for accurate and strong adjectives, make sure you are first using accurate and strong nouns and verbs. For example, if you were revising the sentence “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War,” think about whether “book” and “tells” are as strong as they could be before you worry about “good.” (A stronger sentence might read “The novel describes the experiences of a soldier during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” tells us what kind of book it is, and “describes” tells us more about how the book communicates information.)

- Try the slash/option technique, which is like brainstorming as you write. When you get stuck, write out two or more choices for a questionable word or a confusing sentence, e.g., “questionable/inaccurate/vague/inappropriate.” Pick the word that best indicates your meaning or combine different terms to say what you mean.

- Look for repetition. When you find it, decide if it is “good” repetition (using key terms that are crucial and helpful to meaning) or “bad” repetition (redundancy or laziness in reusing words).

- Write your thesis in five different ways. Make five different versions of your thesis sentence. Compose five sentences that express your argument. Try to come up with four alternatives to the thesis sentence you’ve already written. Find five possible ways to communicate your argument in one sentence to your reader. (We’ve just used this technique—which of the last five sentences do you prefer?)Whenever we write a sentence we make choices. Some are less obvious than others, so that it can often feel like we’ve written the sentence the only way we know how. By writing out five different versions of your thesis, you can begin to see your range of choices. The final version may be a combination of phrasings and words from all five versions, or the one version that says it best. By literally spelling out some possibilities for yourself, you will be able to make better decisions.

- Read your paper out loud and at… a… slow… pace. You can do this alone or with a friend, roommate, TA, etc. When read out loud, your written words should make sense to both you and other listeners. If a sentence seems confusing, rewrite it to make the meaning clear.

- Instead of reading the paper itself, put it down and just talk through your argument as concisely as you can. If your listener quickly and easily comprehends your essay’s main point and significance, you should then make sure that your written words are as clear as your oral presentation was. If, on the other hand, your listener keeps asking for clarification, you will need to work on finding the right terms for your essay. If you do this in exchange with a friend or classmate, rest assured that whether you are the talker or the listener, your articulation skills will develop.

- Have someone not familiar with the issue read the paper and point out words or sentences they find confusing. Do not brush off this reader’s confusion by assuming they simply doesn’t know enough about the topic. Instead, rewrite the sentences so that your “outsider” reader can follow along at all times.

- Check out the Writing Center’s handouts on style , passive voice , and proofreading for more tips.

Questions to ask yourself

- Am I sure what each word I use really means? Am I positive, or should I look it up?

- Have I found the best word or just settled for the most obvious, or the easiest, one?

- Am I trying too hard to impress my reader?

- What’s the easiest way to write this sentence? (Sometimes it helps to answer this question by trying it out loud. How would you say it to someone?)

- What are the key terms of my argument?

- Can I outline out my argument using only these key terms? What others do I need? Which do I not need?

- Have I created my own terms, or have I simply borrowed what looked like key ones from the assignment? If I’ve borrowed the terms, can I find better ones in my own vocabulary, the texts, my notes, the dictionary, or the thesaurus to make myself clearer?

- Are my key terms too specific? (Do they cover the entire range of my argument?) Can I think of specific examples from my sources that fall under the key term?

- Are my key terms too vague? (Do they cover more than the range of my argument?)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. 1985. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Grossman, Ellie. 1997. The Grammatically Correct Handbook: A Lively and Unorthodox Review of Common English for the Linguistically Challenged . New York: Hyperion.

Houghton Mifflin. 1996. The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Conner, Patricia. 2010. Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English , 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

By Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

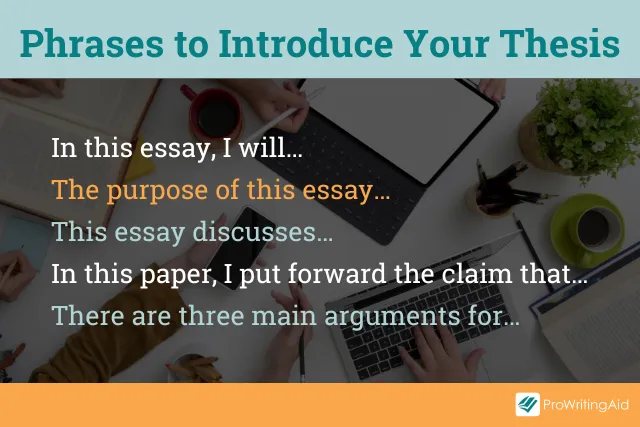

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

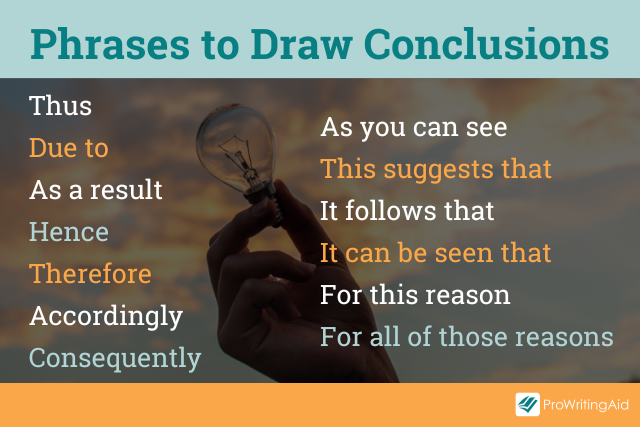

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

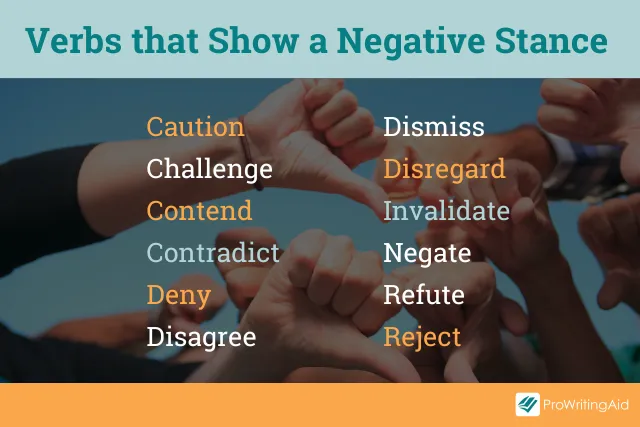

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

COMMENTS

But to make the process of finding academic language a bit easier for you, we have compiled a list of 50 vital academic words and phrases, divided into specific categories and use cases, each with an explanation and contextual example.

Original Word/Phrase: Recommended Substitute: To express the purpose of a paper or research. This paper/ study/ investigation… aims to; This paper + [use the verb that originally followed “aims to”] or This paper + (any other verb listed above as a substitute for “explain”) + who/what/when/where/how X. For example:

Need synonyms for thesis? Here's a list of similar words from our thesaurus that you can use instead. Contexts . A statement or theory that is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. A long essay or dissertation involving personal research. A topic or theme that is being argued or under consideration.

40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays. To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered. Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write ...

This guide looks at how to use transition words in essays. We’ll explain what they are and how to use them, plus we even share an essay transition word list with the most common and useful transition words examples.

These transition terms and phrases organize your paper by numerical sequence; by showing continuation in thought or action; by referring to previously-mentioned information; by indicating digressions; and, finally, by concluding and summing up your paper.

As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices.

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay. Contents: Words to Use in the Essay Introduction. Words to Use in the Body of the Essay. Words to Use in Your Essay Conclusion. How to Improve Your Essay Writing Vocabulary.

When you are writing a dissertation, thesis, or research paper, many words and phrases that are acceptable in conversations or informal writing are considered inappropriate in academic writing.

In academic writing, it is often preferable to use medium modality words (e.g. “often” instead of “always”; “may” instead of “must”). Tip: Only use words which you are comfortable with, otherwise your writing will sound ‘forced’ or ‘unnatural’. Suggestion: highlight the words above you feel confident with now.