Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3. The Self

3.1 The Cognitive Self: The Self-Concept

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe the self-concept, its influence on information processing, and its diversity across social groups.

- Describe the concepts of self-complexity and self-concept clarity, and explain how they influence social cognition and behavior.

- Differentiate the various types of self-awareness and self-consciousness.

- Describe self-awareness, self-discrepancy, and self-affirmation theories, and their interrelationships.

- Explore how we sometimes overestimate the accuracy with which other people view us.

Some nonhuman animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and perhaps dolphins, have at least a primitive sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). We know this because of some interesting experiments that have been done with animals. In one study (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the forehead of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed the animals in a cage with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, not the dot on the faces in the mirror. This action suggests that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals, and thus we can assume that they are able to realize that they exist as individuals. Most other animals, including dogs, cats, and monkeys, never realize that it is themselves they see in a mirror.

Infants who have similar red dots painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that chimps do, and they do this by about 18 months of age (Asendorpf, Warkentin, & Baudonnière, 1996; Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The child’s knowledge about the self continues to develop as the child grows. By two years of age, the infant becomes aware of his or her gender as a boy or a girl. At age four, the child’s self-descriptions are likely to be based on physical features, such as hair color, and by about age six, the child is able to understand basic emotions and the concepts of traits, being able to make statements such as “I am a nice person” (Harter, 1998).

By the time children are in grade school, they have learned that they are unique individuals, and they can think about and analyze their own behavior. They also begin to show awareness of the social situation—they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

Development and Characteristics of the Self-Concept

Part of what is developing in children as they grow is the fundamental cognitive part of the self, known as the self-concept. The self-concept is a knowledge representation that contains knowledge about us, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, as well as the knowledge that we exist as individuals . Throughout childhood and adolescence, the self-concept becomes more abstract and complex and is organized into a variety of different cognitive aspects of the self , known as self-schemas. Children have self-schemas about their progress in school, their appearance, their skills at sports and other activities, and many other aspects. In turn, these self-schemas direct and inform their processing of self-relevant information (Harter, 1999), much as we saw schemas in general affecting our social cognition.

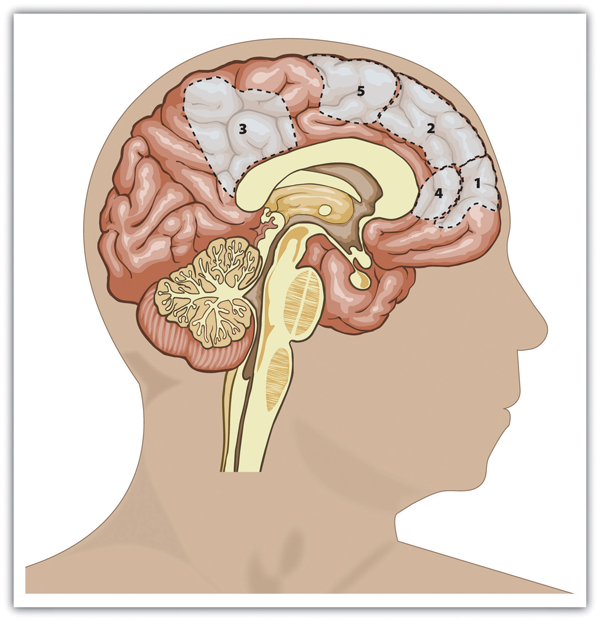

These self-schemas can be studied using the methods that we would use to study any other schema. One approach is to use neuroimaging to directly study the self in the brain. As you can see in Figure 3.3, neuroimaging studies have shown that information about the self is stored in the prefrontal cortex, the same place that other information about people is stored (Barrios et al., 2008).

Another approach to studying the self is to investigate how we attend to and remember things that relate to the self. Indeed, because the self-concept is the most important of all our schemas, it has an extraordinary degree of influence on our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Have you ever been at a party where there was a lot of noise and bustle, and yet you were surprised to discover that you could easily hear your own name being mentioned in the background? Because our own name is such an important part of our self-concept, and because we value it highly, it is highly accessible. We are very alert for, and react quickly to, the mention of our own name.

Other research has found that information related to the self-schema is better remembered than information that is unrelated to it, and that information related to the self can also be processed very quickly (Lieberman, Jarcho, & Satpute, 2004). In one classic study that demonstrated the importance of the self-schema, Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker (1977) conducted an experiment to assess how college students recalled information that they had learned under different processing conditions. All the participants were presented with the same list of 40 adjectives to process, but through the use of random assignment, the participants were given one of four different sets of instructions about how to process the adjectives.

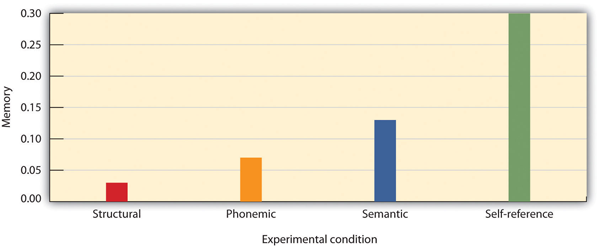

Participants assigned to the structural task condition were asked to judge whether the word was printed in uppercase or lowercase letters. Participants in the phonemic task condition were asked whether the word rhymed with another given word. In the semantic task condition , the participants were asked if the word was a synonym of another word. And in the self-reference task condition , participants indicated whether the given adjective was or was not true of themselves. After completing the specified task, each participant was asked to recall as many adjectives as he or she could remember. Rogers and his colleagues hypothesized that different types of processing would have different effects on memory. As you can see in Figure 3.4, “The Self-Reference Effect,” the students in the self-reference task condition recalled significantly more adjectives than did students in any other condition.

The chart shows the proportion of adjectives that students were able to recall under each of four learning conditions. The same words were recalled significantly better when they were processed in relation to the self than when they were processed in other ways. Data from Rogers et al. (1977).

The finding that information that is processed in relationship to the self is particularly well remembered , known as the self-reference effect , is powerful evidence that the self-concept helps us organize and remember information. The next time you are studying, you might try relating the material to your own experiences—the self-reference effect suggests that doing so will help you better remember the information.

The specific content of our self-concept powerfully affects the way that we process information relating to ourselves. But how can we measure that specific content? One way is by using self-report tests. One of these is a deceptively simple fill-in-the-blank measure that has been widely used by many scientists to get a picture of the self-concept (Rees & Nicholson, 1994). All of the 20 items in the measure are exactly the same, but the person is asked to fill in a different response for each statement. This self-report measure, known as the Twenty Statements Test (TST), can reveal a lot about a person because it is designed to measure the most accessible—and thus the most important—parts of a person’s self-concept. Try it for yourself, at least five times:

- I am (please fill in the blank)

- I am (please fill in the blank)

Although each person has a unique self-concept, we can identify some characteristics that are common across the responses given by different people on the measure. Physical characteristics are an important component of the self-concept, and they are mentioned by many people when they describe themselves. If you’ve been concerned lately that you’ve been gaining weight, you might write, “I am overweight. ” If you think you’re particularly good looking (“I am attractive ”), or if you think you’re too short (“I am too short ”), those things might have been reflected in your responses. Our physical characteristics are important to our self-concept because we realize that other people use them to judge us. People often list the physical characteristics that make them different from others in either positive or negative ways (“I am blond ,” “I am short ”), in part because they understand that these characteristics are salient and thus likely to be used by others when judging them (McGuire, McGuire, Child, & Fujioka, 1978).

A second aspect of the self-concept relating to personal characteristics is made up of personality traits — the specific and stable personality characteristics that describe an individual (“I am friendly, ” “I am shy, ” “I am persistent ”). These individual differences are important determinants of behavior, and this aspect of the self-concept varies among people.

The remainder of the self-concept reflects its more external, social components; for example, memberships in the social groups that we belong to and care about. Common responses for this component may include “I am an artist ,” “I am Jewish ,” and “I am a mother, sister, daughter. ” As we will see later in this chapter, group memberships form an important part of the self-concept because they provide us with our social identity — the sense of our self that involves our memberships in social groups .

Although we all define ourselves in relation to these three broad categories of characteristics—physical, personality, and social – some interesting cultural differences in the relative importance of these categories have been shown in people’s responses to the TST. For example, Ip and Bond (1995) found that the responses from Asian participants included significantly more references to themselves as occupants of social roles (e.g., “I am Joyce’s friend”) or social groups (e.g., “I am a member of the Cheng family”) than those of American participants. Similarly, Markus and Kitayama (1991) reported that Asian participants were more than twice as likely to include references to other people in their self-concept than did their Western counterparts. This greater emphasis on either external and social aspects of the self-concept reflects the relative importance that collectivistic and individualistic cultures place on an interdependence versus independence (Nisbett, 2003).

Interestingly, bicultural individuals who report acculturation to both collectivist and individualist cultures show shifts in their self-concept depending on which culture they are primed to think about when completing the TST. For example, Ross, Xun, & Wilson (2002) found that students born in China but living in Canada reported more interdependent aspects of themselves on the TST when asked to write their responses in Chinese, as opposed to English. These culturally different responses to the TST are also related to a broader distinction in self-concept, with people from individualistic cultures often describing themselves using internal characteristics that emphasize their uniqueness, compared with those from collectivistic backgrounds who tend to stress shared social group memberships and roles. In turn, this distinction can lead to important differences in social behavior.

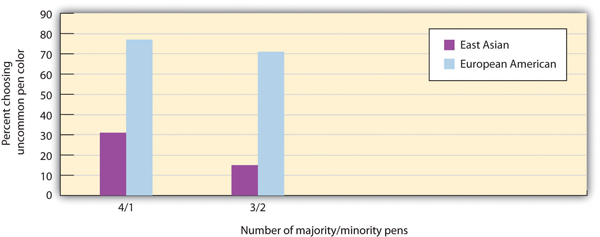

One simple yet powerful demonstration of cultural differences in self-concept affecting social behavior is shown in a study that was conducted by Kim and Markus (1999). In this study, participants were contacted in the waiting area of the San Francisco airport and asked to fill out a short questionnaire for the researcher. The participants were selected according to their cultural background: about one-half of them indicated they were European Americans whose parents were born in the United States, and the other half indicated they were Asian Americans whose parents were born in China and who spoke Chinese at home. After completing the questionnaires (which were not used in the data analysis except to determine the cultural backgrounds), participants were asked if they would like to take a pen with them as a token of appreciation. The experimenter extended his or her hand, which contained five pens. The pens offered to the participants were either three or four of one color and one or two of another color (the ink in the pens was always black). As shown in Figure 3.5, “Cultural Differences in Desire for Uniqueness,” and consistent with the hypothesized preference for uniqueness in Western, but not Eastern, cultures, the European Americans preferred to take a pen with the more unusual color, whereas the Asian American participants preferred one with the more common color.

In this study, participants from European American and East Asian cultures were asked to choose a pen as a token of appreciation for completing a questionnaire. There were either four pens of one color and one of another color, or three pens of one color and two of another. European Americans were significantly more likely to choose the more uncommon pen color in both cases. Data are from Kim and Markus (1999, Experiment 3).

Cultural differences in self-concept have even been found in people’s self-descriptions on social networking sites. DeAndrea, Shaw, and Levine (2010) examined individuals’ free-text self-descriptions in the About Me section in their Facebook profiles. Consistent with the researchers’ hypotheses, and with previous research using the TST, African American participants had the most the most independently (internally) described self-concepts, and Asian Americans had the most interdependent (external) self-descriptions, with European Americans in the middle.

As well as indications of cultural diversity in the content of the self-concept, there is also evidence of parallel gender diversity between males and females from various cultures, with females, on average, giving more external and social responses to the TST than males (Kashima et al., 1995). Interestingly, these gender differences have been found to be more apparent in individualistic nations than in collectivistic nations (Watkins et al., 1998).

Self-Complexity and Self-Concept Clarity

As we have seen, the self-concept is a rich and complex social representation of who we are, encompassing both our internal characteristics and our social roles. In addition to our thoughts about who we are right now, the self-concept also includes thoughts about our past self—our experiences, accomplishments, and failures—and about our future self—our hopes, plans, goals, and possibilities (Oyserman, Bybee, Terry, & Hart-Johnson, 2004). The multidimensional nature of our self-concept means that we need to consider not just each component in isolation, but also their interactions with each other and their overall structure. Two particularly important structural aspects of our self-concept are complexity and clarity.

Although every human being has a complex self-concept, there are nevertheless individual differences in self-complexity, the extent to which individuals have many different and relatively independent ways of thinking about themselves (Linville, 1987; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Some selves are more complex than others, and these individual differences can be important in determining psychological outcomes. Having a complex self means that we have a lot of different ways of thinking about ourselves. For example, imagine a woman whose self-concept contains the social identities of student, girlfriend, daughter, psychology student , and tennis player and who has encountered a wide variety of life experiences. Social psychologists would say that she has high self-complexity. On the other hand, a man who perceives himself primarily as either a student or as a member of the soccer team and who has had a relatively narrow range of life experiences would be said to have low self-complexity. For those with high self-complexity, the various aspects of the self are separate, as the positive and negative thoughts about a particular self-aspect do not spill over into thoughts about other aspects.

Research has found that compared with people low in self-complexity, those higher in self-complexity tend to experience more positive outcomes, including higher levels of self-esteem (Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002), lower levels of stress and illness (Kalthoff & Neimeyer, 1993), and a greater tolerance for frustration (Gramzow, Sedikides, Panter, & Insko, 2000).

The benefits of self-complexity occur because the various domains of the self help to buffer us against negative events and enjoy the positive events that we experience. For people low in self-complexity, negative outcomes in relation to one aspect of the self tend to have a big impact on their self-esteem. For example, if the only thing that Maria cares about is getting into medical school, she may be devastated if she fails to make it. On the other hand, Marty, who is also passionate about medical school but who has a more complex self-concept, may be better able to adjust to such a blow by turning to other interests.

Although having high self-complexity seems useful overall, it does not seem to help everyone equally in their response to all events (Rafaeli-Mor & Steinberg, 2002). People with high self-complexity seem to react more positively to the good things that happen to them but not necessarily less negatively to the bad things. And the positive effects of self-complexity are stronger for people who have other positive aspects of the self as well. This buffering effect is stronger for people with high self-esteem, whose self-complexity involves positive rather than negative characteristics (Koch & Shepperd, 2004), and for people who feel that they have control over their outcomes (McConnell et al., 2005).

Just as we may differ in the complexity of our self-concept, so we may also differ in its clarity. Self-concept clarity is the extent to which one’s self-concept is clearly and consistently defined (Campbell, 1990). Theoretically, the concepts of complexity and clarity are independent of each other—a person could have either a more or less complex self-concept that is either well defined and consistent, or ill defined and inconsistent. However, in reality, they each have similar relationships to many indices of well-being.

For example, as has been found with self-complexity, higher self-concept clarity is positively related to self-esteem (Campbell et al., 1996). Why might this be? Perhaps people with higher self-esteem tend to have a more well-defined and stable view of their positive qualities, whereas those with lower self-esteem show more inconsistency and instability in their self-concept, which is then more vulnerable to being negatively affected by challenging situations. Consistent with this assertion, self-concept clarity appears to mediate the relationship between stress and well-being (Ritchie et al., 2011).

Also, having a clear and stable view of ourselves can help us in our relationships. Lewandowski, Nardine, and Raines (2010) found a positive correlation between clarity and relationship satisfaction, as well as a significant increase in reported satisfaction following an experimental manipulation of participants’ self-concept clarity. Greater clarity may promote relationship satisfaction in a number of ways. As Lewandowski and colleagues (2010) argue, when we have a clear self-concept, we may be better able to consistently communicate who we are and what we want to our partner, which will promote greater understanding and satisfaction. Also, perhaps when we feel clearer about who we are, then we feel less of a threat to our self-concept and autonomy when we find ourselves having to make compromises in our close relationships.

Thinking back to the cultural differences we discussed earlier in this section in the context of people’s self-concepts, it could be that self-concept clarity is generally higher in individuals from individualistic cultures, as their self-concept is based more on internal characteristics that are held to be stable across situations, than on external social facets of the self that may be more changeable. This is indeed what the research suggests. Not only do members of more collectivistic cultures tend to have lower self-concept clarity, that clarity is also less strongly related to their self-esteem compared with those from more individualistic cultures (Campbell et al., 1996). As we shall see when our attention turns to perceiving others in Chapter 5, our cultural background not only affects the clarity and consistency of how we see ourselves, but also how consistently we view other people and their behavior.

Self-Awareness

Like any other schema, the self-concept can vary in its current cognitive accessibility. Self-awareness refers to the extent to which we are currently fixing our attention on our own self-concept . When our self-concept becomes highly accessible because of our concerns about being observed and potentially judged by others, we experience the publicly induced self-awareness known as self-consciousness (Duval & Wicklund, 1972; Rochat, 2009).

Perhaps you can remember times when your self-awareness was increased and you became self-conscious—for instance, when you were giving a presentation and you were perhaps painfully aware that everyone was looking at you, or when you did something in public that embarrassed you. Emotions such as anxiety and embarrassment occur in large part because the self-concept becomes highly accessible, and they serve as a signal to monitor and perhaps change our behavior.

Not all aspects of our self-concept are equally accessible at all times, and these long-term differences in the accessibility of the different self-schemas help create individual differences in terms of, for instance, our current concerns and interests. You may know some people for whom the physical appearance component of the self-concept is highly accessible. They check their hair every time they see a mirror, worry whether their clothes are making them look good, and do a lot of shopping—for themselves, of course. Other people are more focused on their social group memberships—they tend to think about things in terms of their role as Muslims or Christians, for example, or as members of the local tennis or soccer team.

In addition to variation in long-term accessibility, the self and its various components may also be made temporarily more accessible through priming. We become more self-aware when we are in front of a mirror, when a TV camera is focused on us, when we are speaking in front of an audience, or when we are listening to our own tape-recorded voice (Kernis & Grannemann, 1988). When the knowledge contained in the self-schema becomes more accessible, it also becomes more likely to be used in information processing and to influence our behavior.

Beaman, Klentz, Diener, and Svanum (1979) conducted a field experiment to see if self-awareness would influence children’s honesty. The researchers expected that most children viewed stealing as wrong but that they would be more likely to act on this belief when they were more self-aware. They conducted this experiment on Halloween in homes within the city of Seattle, Washington. At particular houses, children who were trick-or-treating were greeted by one of the experimenters, shown a large bowl of candy, and were told to take only one piece each. The researchers unobtrusively watched each child to see how many pieces he or she actually took. In some of the houses there was a large mirror behind the candy bowl; in other houses, there was no mirror. Out of the 363 children who were observed in the study, 19% disobeyed instructions and took more than one piece of candy. However, the children who were in front of a mirror were significantly less likely to steal (14.4%) than were those who did not see a mirror (28.5%).

These results suggest that the mirror activated the children’s self-awareness, which reminded them of their belief about the importance of being honest. Other research has shown that being self-aware has a powerful influence on other behaviors as well. For instance, people are more likely to stay on a diet, eat better food, and act more morally overall when they are self-aware (Baumeister, Zell, & Tice, 2007; Heatherton, Polivy, Herman, & Baumeister, 1993). What this means is that when you are trying to stick to a diet, study harder, or engage in other difficult behaviors, you should try to focus on yourself and the importance of the goals you have set.

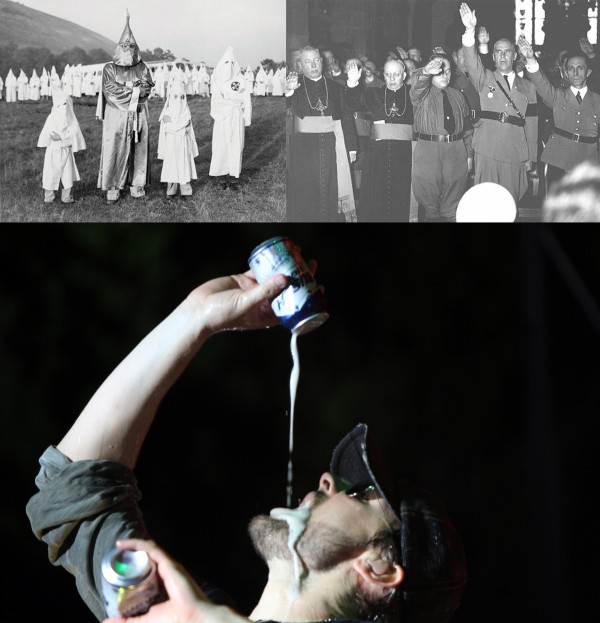

Social psychologists are interested in studying self-awareness because it has such an important influence on behavior. People become more likely to violate acceptable, mainstream social norms when, for example, they put on a Halloween mask or engage in other behaviors that hide their identities. For example, the members of the militant White supremacist organization the Ku Klux Klan wear white robes and hats when they meet and when they engage in their racist behavior. And when people are in large crowds, such as in a mass demonstration or a riot, they may become so much a part of the group that they experience deindividuation — the loss of individual self-awareness and individual accountability in groups (Festinger, Pepitone, & Newcomb, 1952; Zimbardo, 1969) and become more attuned to themselves as group members and to the specific social norms of the particular situation (Reicher & Stott, 2011).

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

Deindividuation and rioting.

Rioting occurs when civilians engage in violent public disturbances. The targets of these disturbances can be people in authority, other civilians, or property. The triggers for riots are varied, including everything from the aftermath of sporting events, to the killing of a civilian by law enforcement officers, to commodity shortages, to political oppression. Both civilians and law enforcement personnel are frequently seriously injured or killed during riots, and the damage to public property can be considerable.

Social psychologists, like many other academics, have long been interested in the forces that shape rioting behavior. One of the earliest and most influential perspectives on rioting was offered by French sociologist, Gustav Le Bon (1841–1931). In his book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, Le Bon (1895) described the transformation of the individual in the crowd. According to Le Bon, the forces of anonymity, suggestibility, and contagion combine to change a collection of individuals into a “psychological crowd.” Under this view, the individuals then become submerged in the crowd, lose self-control, and engage in antisocial behaviors.

Some of the early social psychological accounts of rioting focused in particular on the concept of deindividuation as a way of trying to account for the forces that Le Bon described. Festinger et al. (1952), for instance, argued that members of large groups do not pay attention to other people as individuals and do not feel that their own behavior is being scrutinized. Under this view, being unidentified and thereby unaccountable has the psychological consequence of reducing inner restraints and increasing behavior that is usually repressed, such as that often seen in riots.

Extending these ideas, Zimbardo (1969) argued that deindividuation involved feelings of reduced self-observation, which then bring about antinormative and disinhibited behavior. In support of this position, he found that participants engaged in more antisocial behavior when their identity was made anonymous by wearing Ku Klux Klan uniforms. However, in the context of rioting, these perspectives, which focus on behaviors that are antinormative (e.g., aggressive behavior is typically antinormative), neglect the possibility that they might actually be normative in the particular situation. For example, during some riots, antisocial behavior can be viewed as a normative response to injustice or oppression. Consistent with this assertion, Johnson and Downing (1979) found that when participants were able to mask their identities by wearing nurses uniforms, their deindividuated state actually led them to show more prosocial behavior than when their identities were visible to others. In other words, if the group situation is associated with more prosocial norms, deindividuation can actually increase these behaviors, and therefore does not inevitably lead to antisocial conduct.

Building on these findings, researchers have developed more contemporary accounts of deindividuation and rioting. One particularly important approach has been the social identity model of deindividuation effects (or SIDE model), developed by Reicher, Spears, and Postmes (1995). This perspective argues that being in a deindividuated state can actually reinforce group salience and conformity to specific group norms in the current situation. According to this model, deindividuation does not, then, lead to a loss of identity per se . Instead, people take on a more collective identity. Seen in this way, rioting behavior is more about the conscious adoption of behaviors reflecting collective identity than the abdication of personal identity and responsibility outlined in the earlier perspectives on deindividuation.

In support of the SIDE model, although crowd behavior during riots might seem mindless, antinormative, and disinhibited to the outside observer, to those taking part it is often perceived as rational, normative, and subject to well-defined limits (Reicher, 1987). For instance, when law enforcement officers are the target of rioters, then any targeting of other civilians by rioters is often condemned and policed by the group members themselves (Reicher & Stott, 2011). Indeed, as Fogelson (1971) concluded in his analysis of rioting in the United States in the 1960s, restraint and selectivity, as opposed to mindless and indiscriminate violence, were among the most crucial features of the riots.

Seeing rioting in this way, as a rational, normative response, Reicher and Stott (2011) describe it as being caused by a number of interlocking factors, including a sense of illegitimacy or grievance, a lack of alternatives to confrontation, the formation of a shared identity, and a sense of confidence in collective power. Viewing deindividuation as a force that causes people to increase their sense of collective identity and then to express that identity in meaningful ways leads to some important recommendations for controlling rioting more effectively, including that:

- Labeling rioters as “mindless,” “thugs,” and so on will not address the underlying causes of riots.

- Indiscriminate or disproportionate use of force by police will often lead to an escalation of rioting behavior.

- Law enforcement personnel should allow legitimate and legal protest behaviors to occur during riots, and only illegal and inappropriate behaviors should be targeted.

- Police officers should communicate their intentions to crowds before using force.

Two aspects of individual differences in self-awareness have been found to be important, and they relate to self-concern and other-concern, respectively (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975; Lalwani, Shrum, & Chiu, 2009). Private self-consciousness refers to the tendency to introspect about our inner thoughts and feelings . People who are high in private self-consciousness tend to think about themselves a lot and agree with statements such as “I’m always trying to figure myself out” and “I am generally attentive to my inner feelings.” People who are high on private self-consciousness are likely to base their behavior on their own inner beliefs and values—they let their inner thoughts and feelings guide their actions—and they may be particularly likely to strive to succeed on dimensions that allow them to demonstrate their own personal accomplishments (Lalwani et al., 2009).

Public self-consciousness, in contrast, refers to the tendency to focus on our outer public image and to be particularly aware of the extent to which we are meeting the standards set by others . Those high in public self-consciousness agree with statements such as “I’m concerned about what other people think of me,” “Before I leave my house, I check how I look,” and “I care a lot about how I present myself to others.” These are the people who check their hair in a mirror they pass and spend a lot of time getting ready in the morning; they are more likely to let the opinions of others (rather than their own opinions) guide their behaviors and are particularly concerned with making good impressions on others.

Research has found cultural differences in public self-consciousness, with people from East Asian, collectivistic cultures having higher public self-consciousness than people from Western, individualistic cultures. Steve Heine and colleagues (2008) found that when college students from Canada (a Western culture) completed questionnaires in front of a large mirror, they subsequently became more self-critical and were less likely to cheat (much like the trick-or-treaters discussed earlier) than were Canadian students who were not in front of a mirror. However, the presence of the mirror had no effect on college students from Japan. This person-situation interaction is consistent with the idea that people from East Asian cultures are normally already high in public self-consciousness compared with people from Western cultures, and thus manipulations designed to increase public self-consciousness influence them less.

So we see that there are clearly individual and cultural differences in the degree to and manner in which we tend to be aware of ourselves. In general, though, we all experience heightened moments of self-awareness from time to time. According to self-awareness theory (Duval & Wicklund, 1972), when we focus our attention on ourselves, we tend to compare our current behavior against our internal standards . Sometimes when we make these comparisons, we realize that we are not currently measuring up. In these cases, self-discrepancy theory states that when we perceive a discrepancy between our actual and ideal selves, this is distressing to us (Higgins, Klein, & Strauman, 1987). In contrast, on the occasions when self-awareness leads us to comparisons where we feel that we are being congruent with our standards, then self-awareness can produce positive affect (Greenberg & Musham, 1981). Tying these ideas from the two theories together, Philips and Silvia (2005) found that people felt significantly more distressed when exposed to self-discrepancies while sitting in front of a mirror. In contrast, those not sitting in front of a mirror, and presumably experiencing lower self-awareness, were not significantly emotionally affected by perceived self-discrepancies. Simply put, the more self-aware we are in a given situation, the more pain we feel when we are not living up to our ideals.

In part, the stress arising from perceived self-discrepancy relates to a sense of cognitive dissonance, which is the discomfort that occurs when we respond in ways that we see as inconsistent . In these cases, we may realign our current state to be closer to our ideals, or shift our ideals to be closer to our current state, both of which will help reduce our sense of dissonance. Another potential response to feelings of self-discrepancy is to try to reduce the state of self-awareness that gave rise to these feelings by focusing on other things. For example, Moskalenko and Heine (2002) found that people who are given false negative feedback about their performance on an intelligence test, which presumably lead them to feel discrepant from their internal performance standards about such tasks, subsequently focused significantly more on a video playing in a room than those given positive feedback.

There are certain situations, however, where these common dissonance-reduction strategies may not be realistic options to pursue. For example, if someone who has generally negative attitudes toward drug use nevertheless becomes addicted to a particular substance, it will often not be easy to quit the habit, to reframe the evidence regarding the drug’s negative effects, or to reduce self-awareness. In such cases, self-affirmation theory suggests that people will try to reduce the threat to their self-concept posed by feelings of self-discrepancy by focusing on and affirming their worth in another domain, unrelated to the issue at hand . For instance, the person who has become addicted to an illegal substance may choose to focus on healthy eating and exercise regimes instead as a way of reducing the dissonance created by the drug use.

Although self-affirmation can often help people feel more comfortable by reducing their sense of dissonance, it can also have have some negative effects. For example, Munro and Stansbury (2009) tested people’s social cognitive responses to hypotheses that were either threatening or non-threatening to their self-concepts, following exposure to either a self-affirming or non-affirming activity. The key findings were that those who had engaged in the self-affirmation condition and were then exposed to a threatening hypothesis showed greater tendencies than those in the non-affirming group to seek out evidence confirming their own views, and to detect illusory correlations in support of these positions. One possible interpretation of these results is that self-affirmation elevates people’s mood and they then become more likely to engage in heuristic processing, as discussed in Chapter 2.

Still another option to pursue when we feel that our current self is not matching up to our ideal self is to seek out opportunities to get closer to our ideal selves. One method of doing this can be in online environments. Massively multiplayer online (MMO) gaming, for instance, offers people the chance to interact with others in a virtual world, using graphical alter egos, or avatars, to represent themselves. The role of the self-concept in influencing people’s choice of avatars is only just beginning to be researched, but some evidence suggests that gamers design avatars that are closer to their ideal than their actual selves. For example, a study of avatars used in one popular MMO role-play game indicated that players rated their avatars as having more favorable attributes than their own self-ratings, particularly if they had lower self-esteem (Bessiere, Seay, & Keisler, 2007). They also rated their avatars as more similar to their ideal selves than they themselves were. The authors of this study concluded that these online environments allow players to explore their ideal selves, freed from the constraints of the physical world.

There are also emerging findings exploring the role of self-awareness and self-affirmation in relation to behaviors on social networking sites. Gonzales and Hancock (2011) conducted an experiment showing that individuals became more self-aware after viewing and updating their Facebook profiles, and in turn reported higher self-esteem than participants assigned to an offline, control condition. The increased self-awareness that can come from Facebook activity may not always have beneficial effects, however. Chiou and Lee (2013) conducted two experiments indicating that when individuals put personal photos and wall postings onto their Facebook accounts, they show increased self-awareness, but subsequently decreased ability to take other people’s perspectives. Perhaps sometimes we can have too much self-awareness and focus to the detriment of our abilities to understand others. Toma and Hancock (2013) investigated the role of self-affirmation in Facebook usage and found that users viewed their profiles in self-affirming ways, which enhanced their self-worth. They were also more likely to look at their Facebook profiles after receiving threats to their self-concept, doing so in an attempt to use self-affirmation to restore their self-esteem. It seems, then, that the dynamics of self-awareness and affirmation are quite similar in our online and offline behaviors.

Having reviewed some important theories and findings in relation to self-discrepancy and affirmation, we should now turn our attention to diversity. Once again, as with many other aspects of the self-concept, we find that there are important cultural differences. For instance, Heine and Lehman (1997) tested participants from a more individualistic nation (Canada) and a more collectivistic one (Japan) in a situation where they took a personality test and then received bogus positive or negative feedback. They were then asked to rate the desirability of 10 music CDs. Subsequently, they were offered the choice of taking home either their fifth- or sixth-ranked CD, and then required to re-rate the 10 CDs. The critical finding was that the Canadians overall rated their chosen CD higher and their unchosen one lower the second time around, mirroring classic findings on dissonance reduction, whereas the Japanese participants did not. Crucially, though, the Canadian participants who had been given positive feedback about their personalities (in other words, had been given self-affirming evidence in an unrelated domain) did not feel the need to pursue this dissonance reduction strategy. In contrast, the Japanese did not significantly adjust their ratings in response to either positive or negative feedback from the personality test.

Once more, these findings make sense if we consider that the pressure to avoid self-discrepant feelings will tend to be higher in individualistic cultures, where people are expected to be more cross-situationally consistent in their behaviors. Those from collectivistic cultures, however, are more accustomed to shifting their behaviors to fit the needs of the ingroup and the situation, and so are less troubled by such seeming inconsistencies.

Overestimating How Closely and Accurately Others View Us

Although the self-concept is the most important of all our schemas, and although people (particularly those high in self-consciousness) are aware of their self and how they are seen by others, this does not mean that people are always thinking about themselves. In fact, people do not generally focus on their self-concept any more than they focus on the other things and other people in their environments (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982).

On the other hand, self-awareness is more powerful for the person experiencing it than it is for others who are looking on, and the fact that self-concept is so highly accessible frequently leads people to overestimate the extent to which other people are focusing on them (Gilovich & Savitsky, 1999). Although you may be highly self-conscious about something you’ve done in a particular situation, that does not mean that others are necessarily paying all that much attention to you. Research by Thomas Gilovich and colleagues (Gilovich, Medvec, & Savitsky, 2000) found that people who were interacting with others thought that other people were paying much more attention to them than those other people reported actually doing. This may be welcome news, for example, when we find ourselves wincing over an embarrassing comment we made during a group conversation. It may well be that no one else paid nearly as much attention to it as we did!

There is also some diversity in relation to age. Teenagers are particularly likely to be highly self-conscious, often believing that others are watching them (Goossens, Beyers, Emmen, & van Aken, 2002). Because teens think so much about themselves, they are particularly likely to believe that others must be thinking about them, too (Rycek, Stuhr, McDermott, Benker, & Swartz, 1998). Viewed in this light, it is perhaps not surprising that teens can become embarrassed so easily by their parents’ behaviour in public, or by their own physical appearance, for example.

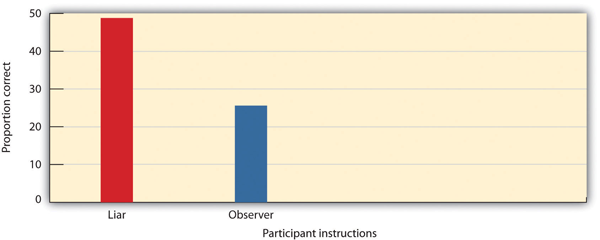

People also often mistakenly believe that their internal states show to others more than they really do. Gilovich, Savitsky, and Medvec (1998) asked groups of five students to work together on a “lie detection” task. One at a time, each student stood up in front of the others and answered a question that the researcher had written on a card (e.g., “I have met David Letterman”). On each round, one person’s card indicated that they were to give a false answer, whereas the other four were told to tell the truth.

After each round, the students who had not been asked to lie indicated which of the students they thought had actually lied in that round, and the liar was asked to estimate the number of other students who would correctly guess who had been the liar. As you can see in Figure 3.7, “The Illusion of Transparency,” the liars overestimated the detectability of their lies: on average, they predicted that over 44% of their fellow players had known that they were the liar, but in fact only about 25% were able to accurately identify them. Gilovich and colleagues called this effect the “illusion of transparency.” This illusion brings home an important final learning point about our self-concepts: although we may feel that our view of ourselves is obvious to others, it may not always be!

Key Takeaways

- The self-concept is a schema that contains knowledge about us. It is primarily made up of physical characteristics, group memberships, and traits.

- Because the self-concept is so complex, it has extraordinary influence on our thoughts, feelings, and behavior, and we can remember information that is related to it well.

- Self-complexity, the extent to which individuals have many different and relatively independent ways of thinking about themselves, helps people respond more positively to events that they experience.

- Self-concept clarity, the extent to which individuals have self-concepts that are clearly defined and stable over time, can also help people to respond more positively to challenging situations.

- Self-awareness refers to the extent to which we are currently fixing our attention on our own self-concept. Differences in the accessibility of different self-schemas help create individual differences: for instance, in terms of our current concerns and interests.

- People who are experiencing high self-awareness may notice self-discrepancies between their actual and ideal selves. This can, in turn, lead them to engage in self-affirmation as a way of resolving these discrepancies.

- When people lose their self-awareness, they experience deindividuation.

- Private self-consciousness refers to the tendency to introspect about our inner thoughts and feelings; public self-consciousness refers to the tendency to focus on our outer public image and the standards set by others.

- There are cultural differences in self-consciousness: public self-consciousness may be higher in Eastern than in Western cultures.

- People frequently overestimate the extent to which others are paying attention to them and accurately understand their true intentions in public situations.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- What are the most important aspects of your self-concept, and how do they influence your self-esteem and social behavior?

- Consider people you know who vary in terms of their self-complexity and self-concept clarity. What effects do these differences seem to have on their self-esteem and behavior?

- Describe a situation where you experienced a feeling of self-discrepancy between your actual and ideal selves. How well does self-affirmation theory help to explain how you responded to these feelings of discrepancy?

- Try to identify some situations where you have been influenced by your private and public self-consciousness. What did this lead you to do? What have you learned about yourself from these experiences?

- Describe some situations where you overestimated the extent to which people were paying attention to you in public. Why do you think that you did this and what were the consequences?

Asendorpf, J. B., Warkentin, V., & Baudonnière, P-M. (1996). Self-awareness and other-awareness. II: Mirror self-recognition, social contingency awareness, and synchronic imitation. Developmental Psychology, 32 (2), 313–321.

Barrios, V., Kwan, V. S. Y., Ganis, G., Gorman, J., Romanowski, J., & Keenan, J. P. (2008). Elucidating the neural correlates of egoistic and moralistic self-enhancement. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 17 (2), 451–456.

Baumeister, R. F., Zell, A. L., & Tice, D. M. (2007). How emotions facilitate and impair self-regulation. In J. J. Gross & J. J. E. Gross (Eds.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 408–426). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beaman, A. L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., & Svanum, S. (1979). Self-awareness and transgression in children: Two field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (10), 1835–1846.

Bessiere, K., Seay, A. F., & Kiesler, S. (2007). The ideal elf: Identity exploration in World of Warcraft. Cyberpsychology and Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(4), 530-535.

Boysen, S. T., & Himes, G. T. (1999). Current issues and emerging theories in animal cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 683–705.

Campbell, J. D. (1990). Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 538-549.

Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavalle, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 141-156.

Chiou, W., & Lee, C. (2013). Enactment of one-to-many communication may induce self-focused attention that leads to diminished perspective taking: The case of Facebook. Judgment And Decision Making , 8 (3), 372-380.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Figurski, T. J. (1982). Self-awareness and aversive experience in everyday life. Journal of Personality, 50 (1), 15–28.

DeAndrea, D. C., Shaw, A. S., & Levine, T. R. (2010). Online language: The role of culture in self-expression and self-construal on Facebook. Journal Of Language And Social Psychology , 29 (4), 425-442. doi:10.1177/0261927X10377989

Doherty, M. J. (2009). Theory of mind: How children understand others’ thoughts and feelings. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. A. (1972). A theory of objective self-awareness . New York, NY: Academic Press.

Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43 , 522–527.

Festinger, L., Pepitone, A., & Newcomb, B. (1952). Some consequences of deindividuation in a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 47, 382–389.

Fogelson, R. M. (1971). Violence as protest: A study of riots and ghettos. New York: Anchor.

Gallup, G. G., Jr. (1970). Chimpanzees: self-recognition. Science, 167, 86–87.

Gilovich, T., & Savitsky, K. (1999). The spotlight effect and the illusion of transparency: Egocentric assessments of how we are seen by others. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8 (6), 165–168.

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Savitsky, K. (2000). The spotlight effect in social judgment: An egocentric bias in estimates of the salience of one’s own actions and appearance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (2), 211–222.

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others’ ability to read one’s emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 (2), 332–346.

Gonzales, A. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2011). Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: Effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking , 14 (1-2), 79-83. doi:10.1089/cyber.2009.0411

Goossens, L., Beyers, W., Emmen, M., & van Aken, M. (2002). The imaginary audience and personal fable: Factor analyses and concurrent validity of the “new look” measures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12 (2), 193–215.

Gramzow, R. H., Sedikides, C., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2000). Aspects of self-regulation and self-structure as predictors of perceived emotional distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26 , 188–205.

Greenberg, J., & Musham, C. (1981). Avoiding and seeking self-focused attention. Journal of Research in Personality, 15 , 191-200.

Harter, S. (1998). The development of self-representations. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, & personality development (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 553–618). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Heatherton, T. F., Polivy, J., Herman, C. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1993). Self-awareness, task failure, and disinhibition: How attentional focus affects eating. Journal of Personality, 61, 138–143.

Heine, S. J., and Lehman, D. R. (1997). Culture, dissonance, and self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 389-400.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34 (7), 879–887.

Higgins, E. T., Klein, R., & Strauman, T. (1987). Self-discrepancies: Distinguishing among self-states, self-state conflicts, and emotional vulnerabilities. In K. M. Yardley & T. M. Honess (Eds.), Self and identity: Psychosocial perspectives. (pp. 173-186). New York: Wiley.

Ip, G. W. M., & Bond, M. H. (1995). Culture, values, and the spontaneous self-concept. Asian Journal of Psychology, 1, 29-35.

Johnson, R. D. & Downing, L. L. (1979). Deindividuation and valence of cues: Effects of prosocial and antisocial behavior. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 37, 1532-1538 10.1037//0022-3514 .37.9.1532.

Kalthoff, R. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1993). Self-complexity and psychological distress: A test of the buffering model. International Journal of Personal Construct Psychology, 6 (4), 327–349.

Kashima, Y., Yamaguchi, S., Kim, U., Choi, S., Gelfank, M., & Yuki, M. (1995). Culture, gender, and self: A perspective from individualism-collectivism research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 925-937.

Kernis, M. H., & Grannemann, B. D. (1988). Private self-consciousness and perceptions of self-consistency. Personality and Individual Differences, 9 (5), 897–902.

Kim, H., & Markus, H. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A cultural analysis. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology , 77 (4), 785-800. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.785

Koch, E. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2004). Is self-complexity linked to better coping? A review of the literature. Journal of Personality, 72 (4), 727–760.

Lalwani, A. K., Shrum, L. J., & Chiu, C-Y. (2009). Motivated response styles: The role of cultural values, regulatory focus, and self-consciousness in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 870–882.

Le Bon, G. (1895). The crowd: A study of the popular mind. Project Gutenberg.

Lewandowski, G. R., Nardon, N., Raines, A. J. (2010). The role of self-concept clarity in relationship quality. Self and Identity, 9(4), 416-433.

Lieberman, M. D. (2010). Social cognitive neuroscience. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 143–193). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lieberman, M. D., Jarcho, J. M., & Satpute, A. B. (2004). Evidence-based and intuition-based self-knowledge: An fMRI study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87 (4), 421–435.

Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (4), 663–676.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review , 98 (2), 224-253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

McConnell, A. R., Renaud, J. M., Dean, K. K., Green, S. P., Lamoreaux, M. J., Hall, C. E.,…Rydel, R. J. (2005). Whose self is it anyway? Self-aspect control moderates the relation between self-complexity and well-being. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41 (1), 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.02.004

McGuire, W. J., McGuire, C. V., Child, P., & Fujioka, T. (1978). Salience of ethnicity in the spontaneous self-concept as a function of one’s ethnic distinctiveness in the social enviornment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36 , 511–520.

Moskalenko, S., & Heine, S. J. (2002). Watching your troubles away: Television viewing as a stimulus for subjective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 76-85.

Munro, G. D., & Stansbury, J. A. (2009). The dark side of self-affirmation: Confirmation bias and illusory correlation in response to threatening information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(9), 1143-1153.

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought. New York, NY: Free Press.

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., Terry, K., & Hart-Johnson, T. (2004). Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality, 38 (2), 130–149.

Phillips, A. G., & Silvia, P. J. (2005). Self-Awareness and the Emotional Consequences of Self-Discrepancies. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin , 31 (5), 703-713. doi:10.1177/0146167204271559

Povinelli, D. J., Landau, K. R., & Perilloux, H. K. (1996). Self-recognition in young children using delayed versus live feedback: Evidence of a developmental asynchrony. Child Development, 67 (4), 1540–1554.

Rafaeli-Mor, E., & Steinberg, J. (2002). Self-complexity and well-being: A review and research synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6 , 31–58.

Reicher, S. D. (1987). Crowd behaviour as social action. In J. C. Turner, M. A. Hogg, P. J. Oakes, S. D. Reicher, & M. S. Wetherell (Eds.), Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory (pp. 171–202). Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell

Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. In W. Strobe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (pp.161-198). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Reicher, S., & Stott, C. (2011). Mad mobs and Englishmen? Myths and realities of the 2011 riots. London: Constable and Robinson.

Rees, A., & Nicholson, N. (1994). The Twenty Statements Test. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Qualitative methods in organizational research: A practical guide (pp. 37–54).

Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Gidron, Y. (2011). Self-concept clarity mediates the relation between stress and subjective well-being. Self and Identity, 10(4), 493-508.

Roccas, S., & Brewer, M. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6 (2), 88–106.

Rochat, P. (2009). Others in mind: Social origins of self-consciousness. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35 (9), 677–688.

Ross, M., Xun, W. Q., & Wilson, A. E. (2002). Language and the bicultural self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1040-1050.

Rycek, R. F., Stuhr, S. L., McDermott, J., Benker, J., & Swartz, M. D. (1998). Adolescent egocentrism and cognitive functioning during late adolescence. Adolescence, 33 , 746–750.

Toma, C. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2013). Self-affirmation underlies Facebook use. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin , 39 (3), 321-331. doi:10.1177/0146167212474694

Watkins, D., Akande, A. , Fleming, J., Ismail, M., Lefner, K., Regmi, M., Watson, S., Yu, J., Adair, J., Cheng, C., Gerong, A., McInerney, D., Mpofu, E., Sinch-Sengupta, S., & Wondimu, H. (1998). Cultural dimensions, gender, and the nature of self-concept: A fourteen-country study. International Journal of Psychology, 33, 17-31.

Zimbardo, P. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason and order versus deindividuation impulse and chaos. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.), Nebraska Symposium of Motivation (Vol. 17). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Media Attributions

- “ Getting Ready ” by Flavia is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence .

- “ mirror mirror who is the most beautiful dog? ” by rromer is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- “ Quite reflection ” by ucumari photography is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- “ Toddler in mirror ” by Samantha Steele is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence .

- “ 08KKKfamilyPortrait ” by Image Editor is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 licence .

- “ CatholicClergyAndNaziOfficials ” by Unknown author is licensed under a CC0 1.0 licence .

- “ Eric Church – Having a Beer On Stage 2 – Capitol Records Street Party 2011 – Nashville, Tn ” by Larry Darling is licensed under a CC BY-NC 2.0 licence .

A knowledge representation that contains knowledge about us, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, as well as the knowledge that we exist as individuals.

A variety of different cognitive aspects of the self.

Information that is processed in relationship to the self is particularly well remembered.

The specific and stable personality characteristics that describe an individual (“I am friendly,” “I am shy,” “I am persistent”).

The sense of our self that involves our memberships in social groups.

The extent to which individuals have many different and relatively independent ways of thinking about themselves.

The extent to which one's self-concept is clearly and consistently defined.

The extent to which we are currently fixing our attention on our own self-concept.

When our self-concept becomes highly accessible because of our concerns about being observed and potentially judged by others.

The loss of individual self-awareness and individual accountability in groups.

The tendency to introspect about our inner thoughts and feelings.

The tendency to focus on our outer public image and to be particularly aware of the extent to which we are meeting the standards set by others.

When we focus our attention on ourselves, we tend to compare our current behavior against our internal standards.

When we perceive a discrepancy between our actual and ideal selves, this is distressing to us.

The discomfort that occurs when we respond in ways that we see as inconsistent.

People will try to reduce the threat to their self-concept posed by feelings of self-discrepancy by focusing on and affirming their worth in another domain, unrelated to the issue at hand.

Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International H5P Edition Copyright © 2022 by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Bristol CBT

Cognitive behaviour therapy (cbt), supervision and training.

On reflection: part 1 – reflective practice in CBT

Reflective practice in the training and continuing professional development of cbt practitioners.

The High Intensity Training Handbook (Clinical Education Development and Research [CEDAR], 2020a) states that:

“Reflective practice has long been recognised as a key component in skills development in professional training. Trainees will complete and submit a number of assessed pieces of reflective writing based on the application of CBT techniques to both clients in the workplace and to their own lives” (para. 1).

These submissions include reflective summaries and self-ratings to accompany formative and summative submissions of video recordings of clinical practice, case reports and an assessment and formulation case presentation, and self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) exercises that culminate in an assessed summary of learning from SP/SR.

The author has found it helpful to frame teaching for CBT trainees using the following general definitions of reflective practice:

“A dialogue of thinking and doing through which I become more skilful” (Schön, 1987, p.31)

The “mindful consideration one’s actions, specifically one’s professional actions” and a “challenging, focused and critical assessment of one’s own behaviour as a means towards developing one’s own craftsmanship” (Osterman, 1990, p. 134)

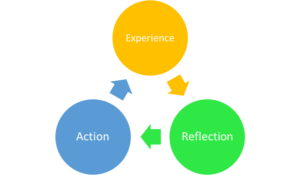

Reflective practice, which is based on the various educational, developmental and experiential learning theories of Dewey, Lewin, Piaget, Borton and Kolb, seeks to integrate experience with reflection and theory with practice in order to lead to:

“greater self-awareness, to the development of new knowledge about professional practice, and to a broader understanding of the problems which confront practitioners” (Osterman, 1990, p. 134)

For many practitioners, becoming a CBT psychotherapist has the feel of a personal vocation as much as a job, but that doesn’t stop aspects of it being routine. As Peters (1991) puts it:

“Work is not always challenging. It can be downright boring at times, even for professionals…Since humans have a need for meaning in their lives, routine work can actually be harmful to one’s health and well-being. Short of changing one’s job, an antidote is to become a reflective practitioner” (p. 89)

Reflective practice is now articulated in a wide variety of theories and models from outside CBT, including those by Gibbs (1988), Rolfe et al. (2001), Driscoll (2007) and Johns (2009). It is both a commonly employed pedagogical method in diverse training across healthcare professions and beyond, and a method of maintaining and developing professional expertise across the professional lifespan of practitioners. At its most straightforward, reflective practice is the application of a three-phase cycle of experiential learning to professional development. The three phases are: experience, reflection and action, in which reflection on experience guides the choice of subsequent actions that in turn form the basis of new experience (Jasper, 2013: Figure 2).

Figure 2: The ERA model (Jasper, 2013).

These phases can be conceptualised in terms of 1) experiential and academic inputs, such as academic teaching, clinical work, and self-experiential or personal practice activities, 2) cognitive-affective reflective processes, such as general reflection and self-reflection in addition to critical and creative thinking, and 3) professional competence outputs as assessed in terms of demonstrable proficiency in the approach being studied. Proficiency might be measured in a number of ways, such as meeting course criteria in order to complete training and gain accreditation, increased self-reflective awareness, or the metacompetence of using reflection to deal with diverse, sometimes poorly defined, problems in professional practice.

It is the author’s experience that initially many trainees either are not convinced of the usefulness of reflection or lack confidence in their ability to reflect and thus to develop a reflective practice. The author has found it helpful when presenting a rationale for reflective practice, to invite trainees to consider the alternative of a non-reflective practitioner, in other words, to consider what it would mean not to reflect and simply to approach psychotherapy as a technical-rational process of applying general and specific practice rules to clearly identified problems. Haarhoff & Thwaites (2015a) provide an illustrative example in the form of an anecdote in which a CBT colleague asked one of the two authors “ Why should therapists reflect? Plumbers don’t need to reflect ” (p. 1, italics in original). As Haarhoff and Thwaites point out, in fact plumbers do need to reflect in order to learn from experience and solve problems they encounter in practice. They might also benefit from sober self-reflection if a lack of awareness about the impact of their interpersonal behaviours leads to repeated problems with their customers.

We might ask whether the use of a plumber is an appropriate metaphor for a psychotherapeutic approach such as CBT given that it supposes that psychotherapy is essentially a mechanistic, rational process of “re-plumbing” the dysfunctional cognitive “pipes” of the mind to make sure that rational thoughts flow down the correct conduits. Along with the relevant technical and conceptual knowledge that a plumber has, their tools are found in a literal toolbox. A psychotherapist, even in CBT, might have a metaphorical toolbox of techniques, or clinical interventions, but in practice relies on interpersonal understanding and influence through the intentional use of self in relationship to help facilitate cognitive, affective, behavioural and situational change. In fact, on reflection, the unreflective nature of a statement such as “ Why should therapists reflect? Plumbers don’t need to reflect ” almost makes the case for reflective practice by itself.

Mezirow (1997) frames the choice between a reflective and a non-reflective approach to what is being learned in terms of moral responsibility, that is as one of choosing between, on the one hand, acting uncritically on the received ideas and judgments of authority figures or, on the other hand, learning to “become a socially responsible autonomous thinker” (p. 8) i.e., someone who is capable of using their own insight and judgement in situations of uncertainty. This is perhaps stating the choice more dichotomously than is necessary. As Schön (1983) points out, much of the time we can apply standard practice rules without too much difficulty. On the other hand, it is also undeniably the case that people frequently fail to monitor, and thus pick up, characteristic errors in judgement. In fact, as Stanovich and West (2000) summarise it:

“people assess probabilities incorrectly, they display confirmation bias, they test hypotheses inefficiently, they violate the axioms of utility theory, they do not properly calibrate degrees of belief, they overproject their own opinions on others, they allow prior knowledge to become implicated in deductive reasoning, and they display numerous other information processing biases” (p. 645).

Perhaps it would be more useful to frame the distinction between reflective and non-reflective approaches in terms of cognitive processing styles. Errors in judgement based on, for example, the application of standard practice rules in a non-reflective manner, reflect the use of intuition or heuristics that have been labelled System 1 cognitive processes. System 1 processes are fast, automatic, perceived as effortless, work by association, and are often emotionally charged. They tend to be governed by habit and can therefore be difficult to control or modify. What we think of as reasoning, or System 2 cognitive processes, on the other hand, is a slower, more effortful, deliberately controlled, serial process (i.e. processing one idea at a time) that is relatively flexible and potentially rule-governed. An important corollary to this distinction is that System 2 monitors System 1 (Kahneman, 2003), helping us to understand why the perceptions, behaviour, cognitions and affects that constitute experience form the raw material that the slower, more effortful process of deliberate reflection operates on in order to make meaning from experience and correct initial impressions or unhelpful responses.

There is also a reflexive element (in the sense of turning back on itself) to reflective practice that acknowledges that our development as professionals might in some senses mirror the psychotherapeutic process as it is understood in CBT. The idea of teaching the client to become their own therapist is foundational in CBT theory and practice (Beck, 2011). If reflective practice can be seen as a form of experiential learning with the goal of becoming more skilful, then CBT itself has been formulated as experiential learning (Milne et al., 2001) Drawing explicitly on Kolb’s (1984) development of the Lewin experiential learning model, Milne et al. state that:

“in effective therapy patients will tend to reflect on their situation, engage in new experiences (including behaving in alternative ways), engage in problem solving and coping strategies, and finally develop alternative theories and concepts of their world…true accommodation will occur when the information processed leads to a new construction of the world” (p. 23).

If, as Milne et al. (2001) propose, CBT is a form of psychotherapy that is in key aspects analogous to experiential learning, then a reflexive personal appreciation of the process of experiential learning becomes a potentially important therapeutic capacity. By reflexive appreciation, the author means that practitioners are able to make links between their own experiences of learning and those that their clients may be experiencing. Training in psychotherapy can be both professionally and personally transformative, and an ongoing reflective practice might help to integrate learning that is taking place at a number of different personal and professional levels of lived experience. Self-reflection on these transformative personal experiences might alert practitioners to salient aspects of the client’s experience, in order to deliver therapeutic interventions sensitively and effectively.

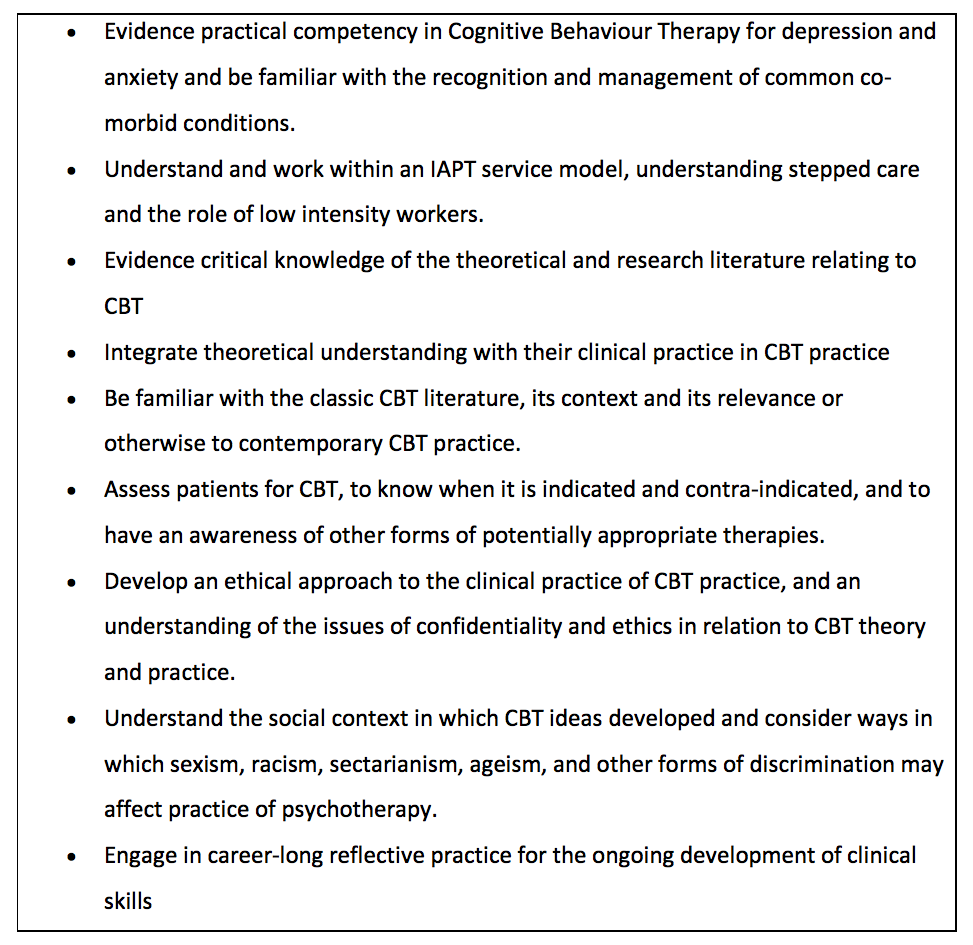

Reflective practice is highly valued in the High Intensity CBT training at the University of Exeter, in line with other similar training courses. CBT trainees are exposed to a wide range of teaching inputs, including lectures, clinical skills tutorials, supervised clinical practice, clinical supervision and SP/SR activities. They are required to demonstrate their developing competence academically, in terms of practice skills, and in terms of reflective practice through writing essays and case reports, participation in supervision, submission of recordings of clinical practice, and writing reflective summaries of both clinical recordings and of SP/SR activities. At the conclusion of their training, it is hoped and intended that they will display competences aligned to the core curriculum of the British Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapy (BABCP) (Hool, 2010), the Roth and Pilling (2007) CBT competence framework, and the IAPT High Intensity Curriculum (Liness & Muston, 2019). The BABCP core curriculum summarises the required learning outcomes of training as:

- “A critical understanding of the scientific and theoretical underpinnings of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies for common mental health disorders across the specialisms

- The core clinical competences required to practise CBT with common mental health disorders across the specialisms” (Hool, 2010, p. 5).

Roth & Pilling (2007) distinguish five areas of clinical competence in the practice of CBT:

- Generic competences – as used in all psychological therapies

- Basic cognitive and behavioural therapy competences – as used in both low- and high-intensity interventions

- Specific cognitive and behavioural therapy techniques – the core technical interventions employed in most forms of CBT

- Problem-specific competences – the packages of CBT interventions for specific low and high-intensity interventions

- Metacompetences – overarching, higher-order competences which practitioners need to use to guide the implementation of any intervention

The specific programme aims of the University of Exeter PG Dip in High Intensity Psychological Therapy (CEDAR, 2020b: Box 1) seeks to provide trainees with “all the necessary academic and training requirements to meet BABCP accreditation as a cognitive behavioural therapist” (para. 1) including the ability to “engage in career-long reflective practice for the ongoing development of clinical skills” (para. 2).

Box 1: Specific programme aims for the University of Exeter’s PG Dip in High Intensity Psychological Therapy (CEDAR, 2020b).

The need for reflective practice does not end at completion of formal training, which is more a rite of passage and validation of one’s baseline competence than the completion of a longer professional journey towards proficiency. As we have seen, the goal of the training is, in part, to inculcate a career-long engagement with reflective practice because professional skill development is a lifelong process (Osterman, 1990). The need to update one’s knowledge and skills in order to develop professionally are part of the rationale for undertaking continuing professional development (CPD) activities, whatever one’s level of experience or qualifications in CBT. The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP, 2020) requires accredited practitioners to engage in “a minimum of five CBT CPD activities per year…This must include at least six hours of CBT skills workshop(s) each year” (para. 1).

As well as keeping a record of CPD, practitioners are required to complete a reflective statement for each activity, where practitioners demonstrate that they have reflected on how the activity was relevant to their clinical practice, what they learned, and how it will impact on their practice. There is evidence that when participants were asked to complete a reflection worksheet at the end of each day of a 2-day skills workshop, and again following an email reminder at 1, 4, and 8 weeks after the training, that this led to a greater awareness and use of skills than those in a control group who did not complete these reflective writing tasks (Bennett-Levy & Padesky, 2014).

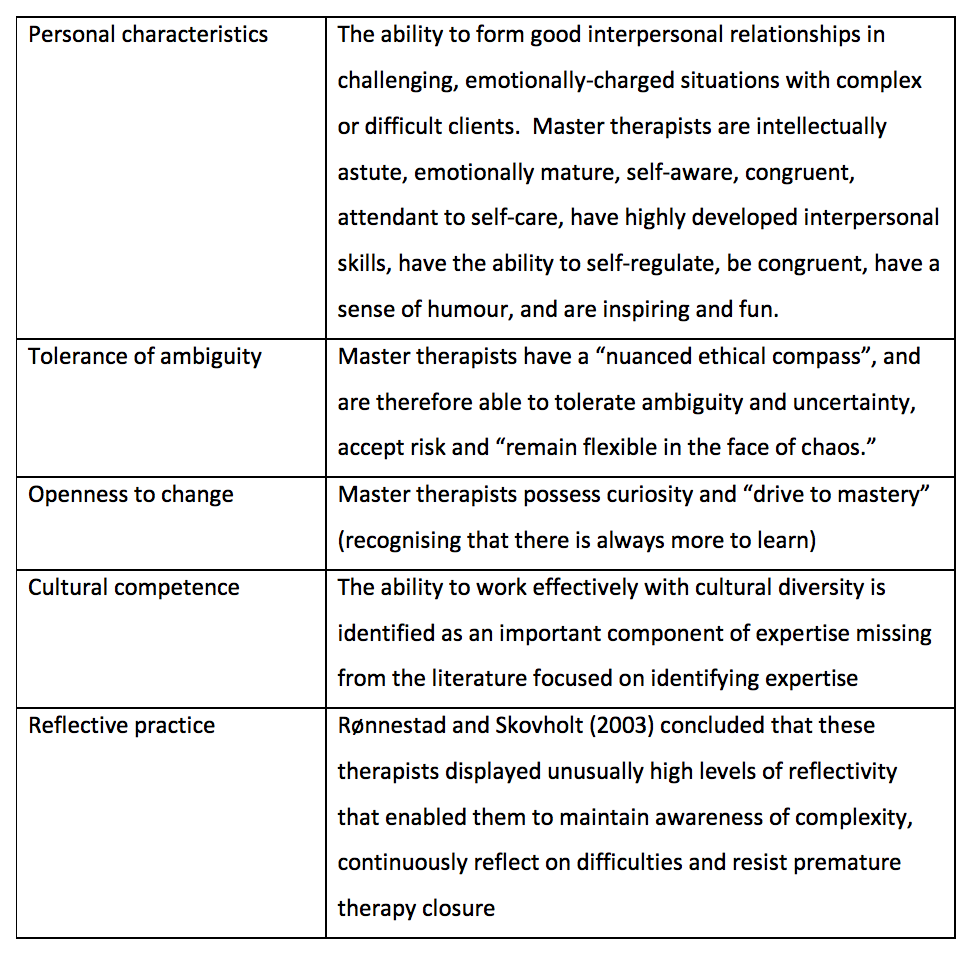

Reflective practice also appears to be a key component in developing and maintaining professional expertise among therapists drawn from a diverse range of therapeutic modalities. For example, Jennings and Skovholt (1999) reported that a selection of peer-nominated “master therapists” displayed the following characteristics that are either by their nature reflective or plausible consequences of reflective practice. Master therapists:

“(a) are voracious learners; (b) draw heavily on accumulated experiences; (c) value cognitive complexity and ambiguity; (d) are emotionally receptive; (e) are mentally healthy and mature and attend to their own emotional well-being; (f) are aware of how their emotional health impacts their work; (g) possess strong relationship skills; (h) believe in the working alliance; and (i) are experts at using their exceptional relational skills in therapy” (p. 3)