Heuristics: Definition, Examples, And How They Work

Benjamin Frimodig

Science Expert

B.A., History and Science, Harvard University

Ben Frimodig is a 2021 graduate of Harvard College, where he studied the History of Science.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

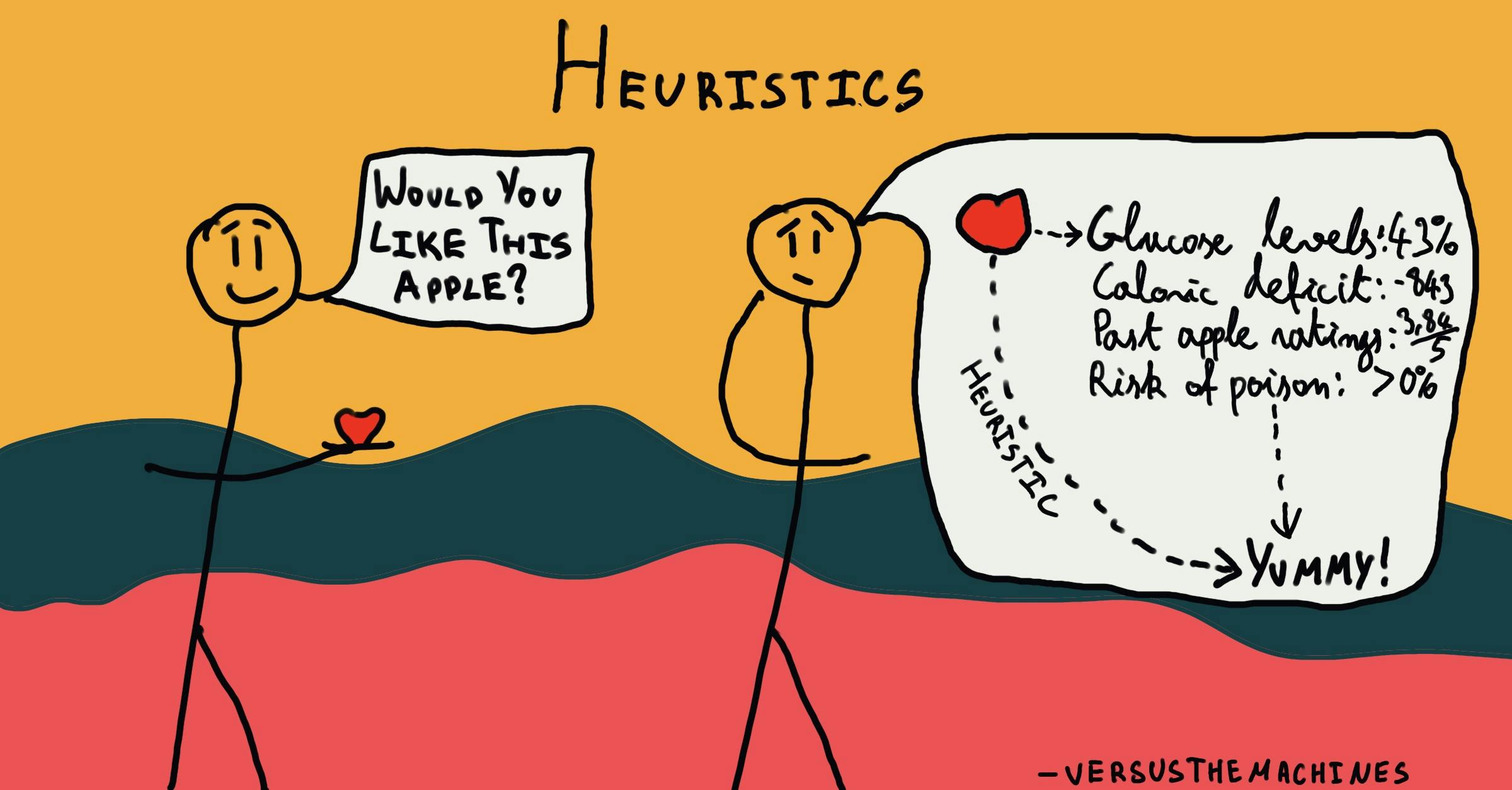

Every day our brains must process and respond to thousands of problems, both large and small, at a moment’s notice. It might even be overwhelming to consider the sheer volume of complex problems we regularly face in need of a quick solution.

While one might wish there was time to methodically and thoughtfully evaluate the fine details of our everyday tasks, the cognitive demands of daily life often make such processing logistically impossible.

Therefore, the brain must develop reliable shortcuts to keep up with the stimulus-rich environments we inhabit. Psychologists refer to these efficient problem-solving techniques as heuristics.

Heuristics can be thought of as general cognitive frameworks humans rely on regularly to reach a solution quickly.

For example, if a student needs to decide what subject she will study at university, her intuition will likely be drawn toward the path that she envisions as most satisfying, practical, and interesting.

She may also think back on her strengths and weaknesses in secondary school or perhaps even write out a pros and cons list to facilitate her choice.

It’s important to note that these heuristics broadly apply to everyday problems, produce sound solutions, and helps simplify otherwise complicated mental tasks. These are the three defining features of a heuristic.

While the concept of heuristics dates back to Ancient Greece (the term is derived from the Greek word for “to discover”), most of the information known today on the subject comes from prominent twentieth-century social scientists.

Herbert Simon’s study of a notion he called “bounded rationality” focused on decision-making under restrictive cognitive conditions, such as limited time and information.

This concept of optimizing an inherently imperfect analysis frames the contemporary study of heuristics and leads many to credit Simon as a foundational figure in the field.

Kahneman’s Theory of Decision Making

The immense contributions of psychologist Daniel Kahneman to our understanding of cognitive problem-solving deserve special attention.

As context for his theory, Kahneman put forward the estimate that an individual makes around 35,000 decisions each day! To reach these resolutions, the mind relies on either “fast” or “slow” thinking.

The fast thinking pathway (system 1) operates mostly unconsciously and aims to reach reliable decisions with as minimal cognitive strain as possible.

While system 1 relies on broad observations and quick evaluative techniques (heuristics!), system 2 (slow thinking) requires conscious, continuous attention to carefully assess the details of a given problem and logically reach a solution.

Given the sheer volume of daily decisions, it’s no surprise that around 98% of problem-solving uses system 1.

Thus, it is crucial that the human mind develops a toolbox of effective, efficient heuristics to support this fast-thinking pathway.

Heuristics vs. Algorithms

Those who’ve studied the psychology of decision-making might notice similarities between heuristics and algorithms. However, remember that these are two distinct modes of cognition.

Heuristics are methods or strategies which often lead to problem solutions but are not guaranteed to succeed.

They can be distinguished from algorithms, which are methods or procedures that will always produce a solution sooner or later.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that can be reliably used to solve a specific problem. While the concept of an algorithm is most commonly used in reference to technology and mathematics, our brains rely on algorithms every day to resolve issues (Kahneman, 2011).

The important thing to remember is that algorithms are a set of mental instructions unique to specific situations, while heuristics are general rules of thumb that can help the mind process and overcome various obstacles.

For example, if you are thoughtfully reading every line of this article, you are using an algorithm.

On the other hand, if you are quickly skimming each section for important information or perhaps focusing only on sections you don’t already understand, you are using a heuristic!

Why Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics usually occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind at the same moment

When studying heuristics, keep in mind both the benefits and unavoidable drawbacks of their application. The ubiquity of these techniques in human society makes such weaknesses especially worthy of evaluation.

More specifically, in expediting decision-making processes, heuristics also predispose us to a number of cognitive biases .

A cognitive bias is an incorrect but pervasive judgment derived from an illogical pattern of cognition. In simple terms, a cognitive bias occurs when one internalizes a subjective perception as a reliable and objective truth.

Heuristics are reliable but imperfect; In the application of broad decision-making “shortcuts” to guide one’s response to specific situations, occasional errors are both inevitable and have the potential to catalyze persistent mistakes.

For example, consider the risks of faulty applications of the representative heuristic discussed above. While the technique encourages one to assign situations into broad categories based on superficial characteristics and one’s past experiences for the sake of cognitive expediency, such thinking is also the basis of stereotypes and discrimination.

In practice, these errors result in the disproportionate favoring of one group and/or the oppression of other groups within a given society.

Indeed, the most impactful research relating to heuristics often centers on the connection between them and systematic discrimination.

The tradeoff between thoughtful rationality and cognitive efficiency encompasses both the benefits and pitfalls of heuristics and represents a foundational concept in psychological research.

When learning about heuristics, keep in mind their relevance to all areas of human interaction. After all, the study of social psychology is intrinsically interdisciplinary.

Many of the most important studies on heuristics relate to flawed decision-making processes in high-stakes fields like law, medicine, and politics.

Researchers often draw on a distinct set of already established heuristics in their analysis. While dozens of unique heuristics have been observed, brief descriptions of those most central to the field are included below:

Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic describes the tendency to make choices based on information that comes to mind readily.

For example, children of divorced parents are more likely to have pessimistic views towards marriage as adults.

Of important note, this heuristic can also involve assigning more importance to more recently learned information, largely due to the easier recall of such information.

Representativeness Heuristic

This technique allows one to quickly assign probabilities to and predict the outcome of new scenarios using psychological prototypes derived from past experiences.

For example, juries are less likely to convict individuals who are well-groomed and wearing formal attire (under the assumption that stylish, well-kempt individuals typically do not commit crimes).

This is one of the most studied heuristics by social psychologists for its relevance to the development of stereotypes.

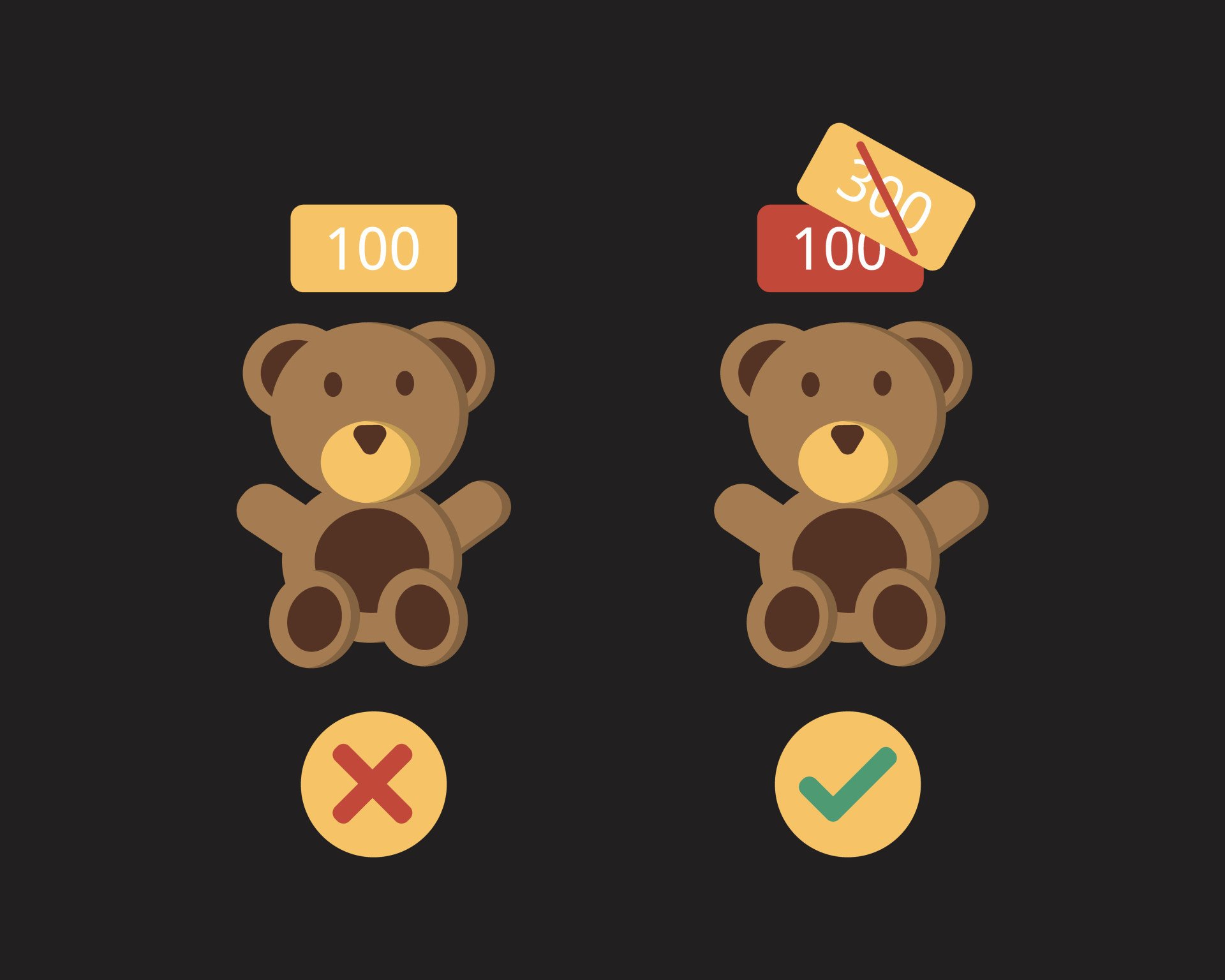

Scarcity Heuristic

This method of decision-making is predicated on the perception of less abundant, rarer items as inherently more valuable than more abundant items.

We rely on the scarcity heuristic when we must make a fast selection with incomplete information. For example, a student deciding between two universities may be drawn toward the option with the lower acceptance rate, assuming that this exclusivity indicates a more desirable experience.

The concept of scarcity is central to behavioral economists’ study of consumer behavior (a field that evaluates economics through the lens of human psychology).

Trial and Error

This is the most basic and perhaps frequently cited heuristic. Trial and error can be used to solve a problem that possesses a discrete number of possible solutions and involves simply attempting each possible option until the correct solution is identified.

For example, if an individual was putting together a jigsaw puzzle, he or she would try multiple pieces until locating a proper fit.

This technique is commonly taught in introductory psychology courses due to its simple representation of the central purpose of heuristics: the use of reliable problem-solving frameworks to reduce cognitive load.

Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic

Anchoring refers to the tendency to formulate expectations relating to new scenarios relative to an already ingrained piece of information.

Put simply, this anchoring one to form reasonable estimations around uncertainties. For example, if asked to estimate the number of days in a year on Mars, many people would first call to mind the fact the Earth’s year is 365 days (the “anchor”) and adjust accordingly.

This tendency can also help explain the observation that ingrained information often hinders the learning of new information, a concept known as retroactive inhibition.

Familiarity Heuristic

This technique can be used to guide actions in cognitively demanding situations by simply reverting to previous behaviors successfully utilized under similar circumstances.

The familiarity heuristic is most useful in unfamiliar, stressful environments.

For example, a job seeker might recall behavioral standards in other high-stakes situations from her past (perhaps an important presentation at university) to guide her behavior in a job interview.

Many psychologists interpret this technique as a slightly more specific variation of the availability heuristic.

How to Make Better Decisions

Heuristics are ingrained cognitive processes utilized by all humans and can lead to various biases.

Both of these statements are established facts. However, this does not mean that the biases that heuristics produce are unavoidable. As the wide-ranging impacts of such biases on societal institutions have become a popular research topic, psychologists have emphasized techniques for reaching more sound, thoughtful and fair decisions in our daily lives.

Ironically, many of these techniques are themselves heuristics!

To focus on the key details of a given problem, one might create a mental list of explicit goals and values. To clearly identify the impacts of choice, one should imagine its impacts one year in the future and from the perspective of all parties involved.

Most importantly, one must gain a mindful understanding of the problem-solving techniques used by our minds and the common mistakes that result. Mindfulness of these flawed yet persistent pathways allows one to quickly identify and remedy the biases (or otherwise flawed thinking) they tend to create!

Further Information

- Shah, A. K., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2008). Heuristics made easy: an effort-reduction framework. Psychological bulletin, 134(2), 207.

- Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 14(1), 77.

- Del Campo, C., Pauser, S., Steiner, E., & Vetschera, R. (2016). Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making. Journal of Business Economics, 86(4), 389-412.

What is a heuristic in psychology?

A heuristic in psychology is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decision-making and problem-solving. Heuristics often speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.

Bobadilla-Suarez, S., & Love, B. C. (2017, May 29). Fast or Frugal, but Not Both: Decision Heuristics Under Time Pressure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition .

Bowes, S. M., Ammirati, R. J., Costello, T. H., Basterfield, C., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Cognitive biases, heuristics, and logical fallacies in clinical practice: A brief field guide for practicing clinicians and supervisors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51 (5), 435–445.

Dietrich, C. (2010). “Decision Making: Factors that Influence Decision Making, Heuristics Used, and Decision Outcomes.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 2(02).

Groenewegen, A. (2021, September 1). Kahneman Fast and slow thinking: System 1 and 2 explained by Sue. SUE Behavioral Design. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://suebehaviouraldesign.com/kahneman-fast-slow-thinking/

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision .

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . Macmillan.

Pratkanis, A. (1989). The cognitive representation of attitudes. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 71–98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simon, H.A., 1956. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review .

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185 (4157), 1124–1131.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Are Heuristics?

These mental shortcuts lead to fast decisions—and biased thinking

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Cindy Chung

- History and Origins

- Heuristics vs. Algorithms

- Heuristics and Bias

How to Make Better Decisions

If you need to make a quick decision, there's a good chance you'll rely on a heuristic to come up with a speedy solution. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. Common types of heuristics rely on availability, representativeness, familiarity, anchoring effects, mood, scarcity, and trial-and-error.

Think of these as mental "rule-of-thumb" strategies that shorten decision-making time. Such shortcuts allow us to function without constantly stopping to think about our next course of action.

However, heuristics have both benefits and drawbacks. These strategies can be handy in many situations but can also lead to cognitive biases . Becoming aware of this might help you make better and more accurate decisions.

Press Play for Advice On Making Decisions

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares a simple way to make a tough decision. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

History of the Research on Heuristics

Nobel-prize winning economist and cognitive psychologist Herbert Simon originally introduced the concept of heuristics in psychology in the 1950s. He suggested that while people strive to make rational choices, human judgment is subject to cognitive limitations. Purely rational decisions would involve weighing every alternative's potential costs and possible benefits.

However, people are limited by the amount of time they have to make a choice and the amount of information they have at their disposal. Other factors, such as overall intelligence and accuracy of perceptions, also influence the decision-making process.

In the 1970s, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman presented their research on cognitive biases. They proposed that these biases influence how people think and make judgments.

Because of these limitations, we must rely on mental shortcuts to help us make sense of the world.

Simon's research demonstrated that humans were limited in their ability to make rational decisions, but it was Tversky and Kahneman's work that introduced the study of heuristics and the specific ways of thinking that people rely on to simplify the decision-making process.

How Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics play important roles in both problem-solving and decision-making , as we often turn to these mental shortcuts when we need a quick solution.

Here are a few different theories from psychologists about why we rely on heuristics.

- Attribute substitution : People substitute simpler but related questions in place of more complex and difficult questions.

- Effort reduction : People use heuristics as a type of cognitive laziness to reduce the mental effort required to make choices and decisions.

- Fast and frugal : People use heuristics because they can be fast and correct in certain contexts. Some theories argue that heuristics are actually more accurate than they are biased.

In order to cope with the tremendous amount of information we encounter and to speed up the decision-making process, our brains rely on these mental strategies to simplify things so we don't have to spend endless amounts of time analyzing every detail.

You probably make hundreds or even thousands of decisions every day. What should you have for breakfast? What should you wear today? Should you drive or take the bus? Fortunately, heuristics allow you to make such decisions with relative ease and without a great deal of agonizing.

There are many heuristics examples in everyday life. When trying to decide if you should drive or ride the bus to work, for instance, you might remember that there is road construction along the bus route. You realize that this might slow the bus and cause you to be late for work. So you leave earlier and drive to work on an alternate route.

Heuristics allow you to think through the possible outcomes quickly and arrive at a solution.

Are Heuristics Good or Bad?

Heuristics aren't inherently good or bad, but there are pros and cons to using them to make decisions. While they can help us figure out a solution to a problem faster, they can also lead to inaccurate judgments about others or situations. Understanding these pros and cons may help you better use heuristics to make better decisions.

Types of Heuristics

There are many different kinds of heuristics. While each type plays a role in decision-making, they occur during different contexts. Understanding the types can help you better understand which one you are using and when.

Availability

The availability heuristic involves making decisions based upon how easy it is to bring something to mind. When you are trying to make a decision, you might quickly remember a number of relevant examples.

Since these are more readily available in your memory, you will likely judge these outcomes as being more common or frequently occurring.

For example, imagine you are planning to fly somewhere on vacation. As you are preparing for your trip, you might start to think of a number of recent airline accidents. You might feel like air travel is too dangerous and decide to travel by car instead. Because those examples of air disasters came to mind so easily, the availability heuristic leads you to think that plane crashes are more common than they really are.

Familiarity

The familiarity heuristic refers to how people tend to have more favorable opinions of things, people, or places they've experienced before as opposed to new ones. In fact, given two options, people may choose something they're more familiar with even if the new option provides more benefits.

Representativeness

The representativeness heuristic involves making a decision by comparing the present situation to the most representative mental prototype. When you are trying to decide if someone is trustworthy, you might compare aspects of the individual to other mental examples you hold.

A soft-spoken older woman might remind you of your grandmother, so you might immediately assume she is kind, gentle, and trustworthy. However, this is an example of a heuristic bias, as you can't know someone trustworthy based on their age alone.

The affect heuristic involves making choices that are influenced by an individual's emotions at that moment. For example, research has shown that people are more likely to see decisions as having benefits and lower risks when in a positive mood.

Negative emotions, on the other hand, lead people to focus on the potential downsides of a decision rather than the possible benefits.

The anchoring bias involves the tendency to be overly influenced by the first bit of information we hear or learn. This can make it more difficult to consider other factors and lead to poor choices. For example, anchoring bias can influence how much you are willing to pay for something, causing you to jump at the first offer without shopping around for a better deal.

Scarcity is a heuristic principle in which we view things that are scarce or less available to us as inherently more valuable. Marketers often use the scarcity heuristic to influence people to buy certain products. This is why you'll often see signs that advertise "limited time only," or that tell you to "get yours while supplies last."

Trial and Error

Trial and error is another type of heuristic in which people use a number of different strategies to solve something until they find what works. Examples of this type of heuristic are evident in everyday life.

People use trial and error when playing video games, finding the fastest driving route to work, or learning to ride a bike (or any new skill).

Difference Between Heuristics and Algorithms

Though the terms are often confused, heuristics and algorithms are two distinct terms in psychology.

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions that lead to predictable, reliable outcomes, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts that are basically best guesses. Algorithms always lead to accurate outcomes, whereas, heuristics do not.

Examples of algorithms include instructions for how to put together a piece of furniture or a recipe for cooking a certain dish. Health professionals also create algorithms or processes to follow in order to determine what type of treatment to use on a patient.

How Heuristics Can Lead to Bias

Heuristics can certainly help us solve problems and speed up our decision-making process, but that doesn't mean they are always a good thing. They can also introduce errors, bias, and irrational decision-making. As in the examples above, heuristics can lead to inaccurate judgments about how commonly things occur and how representative certain things may be.

Just because something has worked in the past does not mean that it will work again, and relying on a heuristic can make it difficult to see alternative solutions or come up with new ideas.

Heuristics can also contribute to stereotypes and prejudice . Because people use mental shortcuts to classify and categorize people, they often overlook more relevant information and create stereotyped categorizations that are not in tune with reality.

While heuristics can be a useful tool, there are ways you can improve your decision-making and avoid cognitive bias at the same time.

We are more likely to make an error in judgment if we are trying to make a decision quickly or are under pressure to do so. Taking a little more time to make a decision can help you see things more clearly—and make better choices.

Whenever possible, take a few deep breaths and do something to distract yourself from the decision at hand. When you return to it, you may find a fresh perspective or notice something you didn't before.

Identify the Goal

We tend to focus automatically on what works for us and make decisions that serve our best interest. But take a moment to know what you're trying to achieve. Consider some of the following questions:

- Are there other people who will be affected by this decision?

- What's best for them?

- Is there a common goal that can be achieved that will serve all parties?

Thinking through these questions can help you figure out your goals and the impact that these decisions may have.

Process Your Emotions

Fast decision-making is often influenced by emotions from past experiences that bubble to the surface. Anger, sadness, love, and other powerful feelings can sometimes lead us to decisions we might not otherwise make.

Is your decision based on facts or emotions? While emotions can be helpful, they may affect decisions in a negative way if they prevent us from seeing the full picture.

Recognize All-or-Nothing Thinking

When making a decision, it's a common tendency to believe you have to pick a single, well-defined path, and there's no going back. In reality, this often isn't the case.

Sometimes there are compromises involving two choices, or a third or fourth option that we didn't even think of at first. Try to recognize the nuances and possibilities of all choices involved, instead of using all-or-nothing thinking .

Heuristics are common and often useful. We need this type of decision-making strategy to help reduce cognitive load and speed up many of the small, everyday choices we must make as we live, work, and interact with others.

But it pays to remember that heuristics can also be flawed and lead to irrational choices if we rely too heavily on them. If you are making a big decision, give yourself a little extra time to consider your options and try to consider the situation from someone else's perspective. Thinking things through a bit instead of relying on your mental shortcuts can help ensure you're making the right choice.

Vlaev I. Local choices: Rationality and the contextuality of decision-making . Brain Sci . 2018;8(1):8. doi:10.3390/brainsci8010008

Hjeij M, Vilks A. A brief history of heuristics: how did research on heuristics evolve? Humanit Soc Sci Commun . 2023;10(1):64. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01542-z

Brighton H, Gigerenzer G. Homo heuristicus: Less-is-more effects in adaptive cognition . Malays J Med Sci . 2012;19(4):6-16.

Schwartz PH. Comparative risk: Good or bad heuristic? Am J Bioeth . 2016;16(5):20-22. doi:10.1080/15265161.2016.1159765

Schwikert SR, Curran T. Familiarity and recollection in heuristic decision making . J Exp Psychol Gen . 2014;143(6):2341-2365. doi:10.1037/xge0000024

AlKhars M, Evangelopoulos N, Pavur R, Kulkarni S. Cognitive biases resulting from the representativeness heuristic in operations management: an experimental investigation . Psychol Res Behav Manag . 2019;12:263-276. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S193092

Finucane M, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson S. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits . J Behav Decis Mak . 2000; 13(1):1-17. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(200001/03)13:1<1::AID-BDM333>3.0.CO;2-S

Teovanović P. Individual differences in anchoring effect: Evidence for the role of insufficient adjustment . Eur J Psychol . 2019;15(1):8-24. doi:10.5964/ejop.v15i1.1691

Cheung TT, Kroese FM, Fennis BM, De Ridder DT. Put a limit on it: The protective effects of scarcity heuristics when self-control is low . Health Psychol Open . 2015;2(2):2055102915615046. doi:10.1177/2055102915615046

Mohr H, Zwosta K, Markovic D, Bitzer S, Wolfensteller U, Ruge H. Deterministic response strategies in a trial-and-error learning task . Inman C, ed. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(11):e1006621. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006621

Grote T, Berens P. On the ethics of algorithmic decision-making in healthcare . J Med Ethics . 2020;46(3):205-211. doi:10.1136/medethics-2019-105586

Bigler RS, Clark C. The inherence heuristic: A key theoretical addition to understanding social stereotyping and prejudice. Behav Brain Sci . 2014;37(5):483-4. doi:10.1017/S0140525X1300366X

del Campo C, Pauser S, Steiner E, et al. Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making . J Bus Econ. 2016;86:389–412. doi:10.1007/s11573-016-0811-y

Marewski JN, Gigerenzer G. Heuristic decision making in medicine . Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2012;14(1):77-89. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/jmarewski

Zheng Y, Yang Z, Jin C, Qi Y, Liu X. The influence of emotion on fairness-related decision making: A critical review of theories and evidence . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1592. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01592

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort. While heuristics can reduce the burden of decision-making and free up limited cognitive resources, they can also be costly when they lead individuals to miss critical information or act on unjust biases.

- Understanding Heuristics

- Different Heuristics

- Problems with Heuristics

As humans move throughout the world, they must process large amounts of information and make many choices with limited amounts of time. When information is missing, or an immediate decision is necessary, heuristics act as “rules of thumb” that guide behavior down the most efficient pathway.

Heuristics are not unique to humans; animals use heuristics that, though less complex, also serve to simplify decision-making and reduce cognitive load.

Generally, yes. Navigating day-to-day life requires everyone to make countless small decisions within a limited timeframe. Heuristics can help individuals save time and mental energy, freeing up cognitive resources for more complex planning and problem-solving endeavors.

The human brain and all its processes—including heuristics— developed over millions of years of evolution . Since mental shortcuts save both cognitive energy and time, they likely provided an advantage to those who relied on them.

Heuristics that were helpful to early humans may not be universally beneficial today . The familiarity heuristic, for example—in which the familiar is preferred over the unknown—could steer early humans toward foods or people that were safe, but may trigger anxiety or unfair biases in modern times.

The study of heuristics was developed by renowned psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Starting in the 1970s, Kahneman and Tversky identified several different kinds of heuristics, most notably the availability heuristic and the anchoring heuristic.

Since then, researchers have continued their work and identified many different kinds of heuristics, including:

Familiarity heuristic

Fundamental attribution error

Representativeness heuristic

Satisficing

The anchoring heuristic, or anchoring bias , occurs when someone relies more heavily on the first piece of information learned when making a choice, even if it's not the most relevant. In such cases, anchoring is likely to steer individuals wrong .

The availability heuristic describes the mental shortcut in which someone estimates whether something is likely to occur based on how readily examples come to mind . People tend to overestimate the probability of plane crashes, homicides, and shark attacks, for instance, because examples of such events are easily remembered.

People who make use of the representativeness heuristic categorize objects (or other people) based on how similar they are to known entities —assuming someone described as "quiet" is more likely to be a librarian than a politician, for instance.

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy in which the first option that satisfies certain criteria is selected , even if other, better options may exist.

Heuristics, while useful, are imperfect; if relied on too heavily, they can result in incorrect judgments or cognitive biases. Some are more likely to steer people wrong than others.

Assuming, for example, that child abductions are common because they’re frequently reported on the news—an example of the availability heuristic—may trigger unnecessary fear or overprotective parenting practices. Understanding commonly unhelpful heuristics, and identifying situations where they could affect behavior, may help individuals avoid such mental pitfalls.

Sometimes called the attribution effect or correspondence bias, the term describes a tendency to attribute others’ behavior primarily to internal factors—like personality or character— while attributing one’s own behavior more to external or situational factors .

If one person steps on the foot of another in a crowded elevator, the victim may attribute it to carelessness. If, on the other hand, they themselves step on another’s foot, they may be more likely to attribute the mistake to being jostled by someone else .

Listen to your gut, but don’t rely on it . Think through major problems methodically—by making a list of pros and cons, for instance, or consulting with people you trust. Make extra time to think through tasks where snap decisions could cause significant problems, such as catching an important flight.

Many apps claim to use nudges but instead use simple reminders that are just re-labeled as nudges. The terminology matters—true nudges use more potent behavioral science.

When you make a mistake for the third time, it's probably about you, not the situation.

The myth of the perfect question, the "fit" fallacy, and more.

Your plans should not be set based on the wisdom shared by successful people. They should be based on your context, your strengths, and your creative inspiration from that wisdom.

Discover how the anchoring effect, a subtle cognitive bias, shapes our decisions across life's domains.

Discrimination is how we treat groups of people. Bias is how we think about them. Can better understanding cognitive biases make a difference in the fight against discrimination?

Artificial intelligence already plays a role in deciding who’s getting hired. The way to improve AI is very similar to how we fight human biases.

Think you are avoiding the motherhood penalty by not having children? Think again. Simply being a woman of childbearing age can trigger discrimination.

Psychological experiments on human judgment under uncertainty showed that people often stray from presumptions about rational economic agents.

Are experts more confident in what they know than what they don't? Yes, but it's not so clear-cut.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Media Center

Why do we take mental shortcuts?

What are heuristics.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, that reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions.

Where this bias occurs

We use heuristics in all sorts of situations. One type of heuristic, the availability heuristic , often happens when we’re attempting to judge the frequency with which a certain event occurs. Say, for example, someone asked you whether more tornadoes occur in Kansas or Nebraska. Most of us can easily call to mind an example of a tornado in Kansas: the tornado that whisked Dorothy Gale off to Oz in Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz . Although it’s fictional, this example comes to us easily. On the other hand, most people have a lot of trouble calling to mind an example of a tornado in Nebraska. This leads us to believe that tornadoes are more common in Kansas than in Nebraska. However, the states actually report similar levels. 1

Case studies

From insight to impact: our success stories, is there a problem we can help with.

- Gilovich, T., Keltner, D., Chen. S, and Nisbett, R. (2015). Social Psychology (4th edition). W.W. Norton and Co. Inc.

- Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science . 185(4157), 1124-1131.

- Mervis, C. B., & Rosch, E. (1981). Categorization of natural objects. Annual Review of Psychology , 32 (1), 89–115. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.32.020181.000513

- Epley, N., & Gilovich, T. (2006). The anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic. Psychological Science -Cambridge- , 17 (4), 311–318.

- System 1 and System 2 Thinking. The Marketing Society. https://www.marketingsociety.com/think-piece/system-1-and-system-2-thinking

- Aggarwal, P., Jun, S. Y., & Huh, J. H. (2011). Scarcity messages. Journal of Advertising , 40 (3), 19–30.

- Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 56 (1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

- Kuo, L., Chang, T., & Lai, C.-C. (2022). Research on product design modeling image and color psychological test. Displays, 71, 102108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2021.102108

About the Authors

Dan is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. Dan has a background in organizational decision making, with a BComm in Decision & Information Systems from McGill University. He has worked on enterprise-level behavioral architecture at TD Securities and BMO Capital Markets, where he advised management on the implementation of systems processing billions of dollars per week. Driven by an appetite for the latest in technology, Dan created a course on business intelligence and lectured at McGill University, and has applied behavioral science to topics such as augmented and virtual reality.

Dr. Sekoul Krastev

Sekoul is a Co-Founder and Managing Director at The Decision Lab. He is a bestselling author of Intention - a book he wrote with Wiley on the mindful application of behavioral science in organizations. A decision scientist with a PhD in Decision Neuroscience from McGill University, Sekoul's work has been featured in peer-reviewed journals and has been presented at conferences around the world. Sekoul previously advised management on innovation and engagement strategy at The Boston Consulting Group as well as on online media strategy at Google. He has a deep interest in the applications of behavioral science to new technology and has published on these topics in places such as the Huffington Post and Strategy & Business.

We are the leading applied research & innovation consultancy

Our insights are leveraged by the most ambitious organizations.

I was blown away with their application and translation of behavioral science into practice. They took a very complex ecosystem and created a series of interventions using an innovative mix of the latest research and creative client co-creation. I was so impressed at the final product they created, which was hugely comprehensive despite the large scope of the client being of the world's most far-reaching and best known consumer brands. I'm excited to see what we can create together in the future.

Heather McKee

BEHAVIORAL SCIENTIST

GLOBAL COFFEEHOUSE CHAIN PROJECT

OUR CLIENT SUCCESS

Annual revenue increase.

By launching a behavioral science practice at the core of the organization, we helped one of the largest insurers in North America realize $30M increase in annual revenue .

Increase in Monthly Users

By redesigning North America's first national digital platform for mental health, we achieved a 52% lift in monthly users and an 83% improvement on clinical assessment.

Reduction In Design Time

By designing a new process and getting buy-in from the C-Suite team, we helped one of the largest smartphone manufacturers in the world reduce software design time by 75% .

Reduction in Client Drop-Off

By implementing targeted nudges based on proactive interventions, we reduced drop-off rates for 450,000 clients belonging to USA's oldest debt consolidation organizations by 46%

Hindsight Bias

Why do unpredictable events only seem predictable after they occur, hot hand fallacy, why do we expect previous success to lead to future success, hyperbolic discounting, why do we value immediate rewards more than long-term rewards.

Eager to learn about how behavioral science can help your organization?

Get new behavioral science insights in your inbox every month..

- Science, Tech, Math ›

- Social Sciences ›

- Psychology ›

Heuristics: The Psychology of Mental Shortcuts

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University

- B.A., Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University

- B.A., Cognitive Science, Johns Hopkins University

Heuristics (also called “mental shortcuts” or “rules of thumb") are efficient mental processes that help humans solve problems and learn new concepts. These processes make problems less complex by ignoring some of the information that’s coming into the brain, either consciously or unconsciously. Today, heuristics have become an influential concept in the areas of judgment and decision-making.

Key Takeaways: Heuristics

- Heuristics are efficient mental processes (or "mental shortcuts") that help humans solve problems or learn a new concept.

- In the 1970s, researchers Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman identified three key heuristics: representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability.

- The work of Tversky and Kahneman led to the development of the heuristics and biases research program.

History and Origins

Gestalt psychologists postulated that humans solve problems and perceive objects based on heuristics. In the early 20th century, the psychologist Max Wertheimer identified laws by which humans group objects together into patterns (e.g. a cluster of dots in the shape of a rectangle).

The heuristics most commonly studied today are those that deal with decision-making. In the 1950s, economist and political scientist Herbert Simon published his A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice , which focused on the concept of on bounded rationality : the idea that people must make decisions with limited time, mental resources, and information.

In 1974, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman pinpointed specific mental processes used to simplify decision-making. They showed that humans rely on a limited set of heuristics when making decisions with information about which they are uncertain—for example, when deciding whether to exchange money for a trip overseas now or a week from today. Tversky and Kahneman also showed that, although heuristics are useful, they can lead to errors in thinking that are both predictable and unpredictable.

In the 1990s, research on heuristics, as exemplified by the work of Gerd Gigerenzer’s research group, focused on how factors in the environment impact thinking–particularly, that the strategies the mind uses are influenced by the environment–rather than the idea that the mind uses mental shortcuts to save time and effort.

Significant Psychological Heuristics

Tversky and Kahneman’s 1974 work, Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases , introduced three key characteristics: representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability.

The representativeness heuristic allows people to judge the likelihood that an object belongs in a general category or class based on how similar the object is to members of that category.

To explain the representativeness heuristic, Tversky and Kahneman provided the example of an individual named Steve, who is “very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful, but with little interest in people or reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.” What is the probability that Steve works in a specific occupation (e.g. librarian or doctor)? The researchers concluded that, when asked to judge this probability, individuals would make their judgment based on how similar Steve seemed to the stereotype of the given occupation.

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic allows people to estimate a number by starting at an initial value (the “anchor”) and adjusting that value up or down. However, different initial values lead to different estimates, which are in turn influenced by the initial value.

To demonstrate the anchoring and adjustment heuristic, Tversky and Kahneman asked participants to estimate the percentage of African countries in the UN. They found that, if participants were given an initial estimate as part of the question (for example, is the real percentage higher or lower than 65%?), their answers were rather close to the initial value, thus seeming to be "anchored" to the first value they heard.

The availability heuristic allows people to assess how often an event occurs or how likely it will occur, based on how easily that event can be brought to mind. For example, someone might estimate the percentage of middle-aged people at risk of a heart attack by thinking of the people they know who have had heart attacks.

Tversky and Kahneman's findings led to the development of the heuristics and biases research program. Subsequent works by researchers have introduced a number of other heuristics.

The Usefulness of Heuristics

There are several theories for the usefulness of heuristics. The accuracy-effort trade-off theory states that humans and animals use heuristics because processing every piece of information that comes into the brain takes time and effort. With heuristics, the brain can make faster and more efficient decisions, albeit at the cost of accuracy.

Some suggest that this theory works because not every decision is worth spending the time necessary to reach the best possible conclusion, and thus people use mental shortcuts to save time and energy. Another interpretation of this theory is that the brain simply does not have the capacity to process everything, and so we must use mental shortcuts.

Another explanation for the usefulness of heuristics is the ecological rationality theory. This theory states that some heuristics are best used in specific environments, such as uncertainty and redundancy. Thus, heuristics are particularly relevant and useful in specific situations, rather than at all times.

- Gigerenzer, G., and Gaissmeier, W. “Heuristic decision making.” Annual Review of Psychology , vol. 62, 2011, pp. 451-482.

- Hertwig, R., and Pachur, T. “Heuristics, history of.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2 Edition nd , Elsevier, 2007.

- “Heuristics representativeness.” Cognitive Consonance.

- Simon. H. A. “A behavioral model of rational choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 69, no. 1, 1955, pp. 99-118.

- Tversky, A., and Kahneman, D. “Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.” Science , vol. 185, no. 4157, pp. 1124-1131.

- What Is Cognitive Bias? Definition and Examples

- What Is a Schema in Psychology? Definition and Examples

- What Is Theory of Mind in Psychology?

- What Is Positive Psychology?

- Why Being a Perfectionist Can Be Harmful

- What Is Mindfulness in Psychology?

- Psychodynamic Theory: Approaches and Proponents

- What Is Behaviorism in Psychology?

- Understanding the Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

- An Introduction to Rogerian Therapy

- How Psychology Defines and Explains Deviant Behavior

- Information Processing Theory: Definition and Examples

- The Life of Carl Jung, Founder of Analytical Psychology

- Understanding Sexual Orientation From a Psychological Perspective

- What Is the Elaboration Likelihood Model in Psychology?

- Introduction to Evolutionary Psychology

Heuristics and Problem Solving

- Reference work entry

- pp 1421–1424

- Cite this reference work entry

- Erik De Corte 2 ,

- Lieven Verschaffel 2 &

- Wim Van Dooren 2

550 Accesses

3 Citations

Definitions

In a general sense heuristics are guidelines or methods for problem solving. Therefore, we will first define problem solving before presenting a specific definition of heuristics.

Problem Solving

In contrast to a routine task, a problem is a situation in which a person is trying to attain a goal but does not dispose of a ready-made solution or solution method. Problem solving involves then “cognitive processing directed at transforming the given situation into a goal situation when no obvious method of solution is available” (Mayer and Wittrock 2006 , p. 287). An implication is that a task can be a problem for one person, but not for someone else. For instance, the task “divide 120 marbles equally among 8 children” may be a problem for beginning elementary school children, but not for people who master the algorithm for long division, or know how to use a calculator.

The term “heuristic” originates from the Greek word heuriskein which means “to find.” Heuristics ...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., & Op’t Eynde, P. (2000). Self-regulation: a characteristic and a goal of mathematics education. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 687–726). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Google Scholar

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., & Masui, C. (2004). The CLIA-model: a framework for designing powerful learning environments for thinking and problem solving. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 19 , 365–384.

Article Google Scholar

Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. a meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning, 3 , 231–264.

Groner, R., Groner, M., & Bischof, W. F. (Eds.). (1983). Methods of heuristics . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mayer, R. E., & Wittrock, M. C. (2006). Problem solving. In P. A. Alexander & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 287–303). New York: Macmillan.

Polya, G. (1945). How to solve it . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical problem solving . New York: Academic.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, Center for Instructional Psychology and Technology (CIP&T), Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Dekenstraat 2, P.O. box 3773, B-3000, Leuven, Belgium

Dr. Erik De Corte, Prof. Dr. Lieven Verschaffel & Wim Van Dooren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Erik De Corte .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., Van Dooren, W. (2012). Heuristics and Problem Solving. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_420

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_420

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A heuristic in psychology is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decision-making and problem-solving. Heuristics often speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. Common types of heuristics rely on availability, representativeness, familiarity, anchoring effects, mood, scarcity, and trial-and-error.

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort.

A heuristic can be used in artificial intelligence systems while searching a solution space. The heuristic is derived by using some function that is put into the system by the designer, or by adjusting the weight of branches based on how likely each branch is to lead to a goal node.

Heuristics reduce the complexity of a decision, problem, or question by neglecting to take into account all relevant and available information. Often called “mental shortcuts” or “rules of thumb,” heuristics are catchall strategies used in a variety of scenarios.

Heuristics appear to be an evolutionary adaptation that simplifies problem-solving and makes it easier for us to navigate the world. After all, our cognition is limited, so it makes sense to use them to reduce the mental effort required to make a decision.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, that reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions. Where this bias occurs.

Heuristics are efficient mental processes (or "mental shortcuts") that help humans solve problems or learn a new concept. In the 1970s, researchers Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman identified three key heuristics: representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability.

An important domain of application of heuristics is artificial intelligence (AI). a well-known example is the general heuristic “means-end analysis,” the key idea of which is to analyze differences between the goal state and the current state of a problem and to strategically apply operators to reduce the difference.

People use heuristics in everyday life as a way to solve a problem or to learn something. By reviewing these heuristic examples you can get an overview of the various techniques of problem-solving and gain an understanding of how to use them when you need to solve a problem in the future.