Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Self-Esteem and Body Image: A Correlational Study

2020, i-manager's Journal on Humanities & Social Sciences

Self esteem is an important aspect of everyone's life and synonymous to respect, regard and acceptance towards oneself. Body image is a crucial element contributing to the development of self concept and self esteem. This study tries to understand the relationship between the two. In this paper it is hypothesized that high self Esteem will lead to positive body Image, hence lead to peaceful journey in one's life. For exploring the same, sample of 80 undergraduate female students were selected via purposive sampling method. Rosenberg's self esteem scale (Morris Rosenberg) &The Body Image Questionnaire (Bruchon-Schweitzer (BIQ), based on five point ratings were used to collect the data. Descriptive and inferential analysis were used to analyze the data. Results discuss the relationship between self esteem and body image. Future implications of this research has also been highlighted.

Related papers

YMER || ISSN : 0044-0477, 2022

Body image refers to a person's impression of their physical self as well as their thoughts and feelings, which can be good or negative. Self-perceptions and self-attitudes towards the body, including thoughts, ideas, feelings, and behaviors. When you have high self-esteem, you generally feel good about yourself. They are proud of their abilities see the positive aspects of their own personality Even if they don't perform well at first, they must have faith in themselves. The relationship between body image and self-esteem was investigated among female using correlation design. Data was collected using (BIS) body image scale and (RSES) Rosenberg self-esteem scale from a sample size of 100 females. The data collected was analyzed using a statistical package for social science (SPSS) to find relationship between the two variables. The result showed that there is a negative significant relationship with body image score is high it shows low body image the have low self-esteem in females.

Guidance, 2020

This study aims to find out the relationship between self-esteem and body image in grade XI students at SMA Negeri 12 Bekasi. This type of research uses descriptive analysis with correlational techniques. The number of subjects used in this study was 122 students of grade XI science and social sciences. Sampling techniques using simple random sampling. Data collection used is the psychological scale of self-esteem and body image questionnaires. After performing a validity test on the self-esteem scale obtained 29 valid items with very strong reliability (0.817), as well as the body image scale obtained 31 valid items with very strong reliability (0.907) and can be used as a data collection tool. The data analysis method used is the product-moment correlation test. The results showed the correlation coefficient r = 0.562 with the signification of p = 0.000 (p < 0.01) so that the conclusion of the results of this study showed that there is a significant relationship between self-es...

International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2015

The present study of Body Image Perceptions and its Correlation with Self Esteem of adolescents studying in engineering colleges of Hyderabad was made to know the relationship between Body Image Perceptions (skin complexion, facial features, blemish free skin, height, weight, etc.) and Self Esteem of adolescents. About 200 adolescents (100 boys and 100 girls) ranging from age group of 18 to 20 years were selected from engineering colleges of Hyderabad and Secunderabad regions of Telangana state. Body Image Perception scale and Rosenberg’s Self Esteem scale were used to collect data and simple Pearson correlation was applied for selected population. The present study contributes to an emerging understanding of underlying relation between body image and self esteem. The findings reveal how the Self esteem is positively correlated with self assessment and perpetually inclined towards the overall assessment of Body Image Perceptions at 1% level of significance. The results presented wil...

JOURNAL OF INDIAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION (IPHA) CHANDIGARH STATE BRANCH, CHANDIGARH (U.T.) Volume 3, No.9 July 2018, 2018

Background: Adolescence age is phase of really rolling and vivid emotional and physical changes. Perception and satisfaction with one’s body image can be dominated by physical and psychological changes, Physical and psychological changes can influence perception and satisfaction with body image, both of which are key stone in the augmentation of self-esteem and social adjustment among adolescent. Objective: To assess the perceived impact of body image on self esteem among adolescent girls and To associate the perception of body image & self-esteem with selected demographic variables. Methods: A Descriptive study to assess the perceived impact of body image on self-esteem among adolescent girls in Baru Sahib, Himachal Pradesh was done in may 2016. A structured questionnaire for body image and Rosenberg scale for self-esteem were used. The Reliability of tool was worked out by using Cronbach’s alpha and was found to be 0.78. The study was conducted on 100 adolescent girls aged 14-19 years. Results: The mean and standard deviation were computed for perception of body image among adolescent girls. The most of the subjects fall in the category of 43-69 indicating that they are partially satisfied from their body image. The self-esteem was measured by using the Rosenberg Self-esteem scale in which most of the sample i.e. 94 (%) falls in normal limits (score of 15 to 25). Using the Karl Pearson’s method, relation coefficient (r) was calculated which was equal to 0.6 indicating that body image and self-esteem has strong positive relation. Further, The significant association was found between adolescents’ weight and perceived body image. On the other hand, the self-esteem among adolescent girls was found to be significantly associated with education, height and weight. Conclusion: Body image and self-esteem go hand in hand. With body dissatisfaction and in try of changing their body shape can lead to unhealthy practices with food and exercise. On the other hand, with low self-esteem, people have a lower worth about themselves and think about themselves as nobody, which can negatively influence their mental capabilities. Key Words: Adolescent, Body image, self- esteem.

International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health

Background: Body image refers to how individuals think, feel and behave in relation to their body and appearance. During adolescence self-perception about their appearance is important to the development of self-esteem and is also understood to be an important predictor of self-worth. Research has shown that inappropriate perception of the body image and dissatisfaction can lead to physical and psychic problems in the youth. In today's society, with the growing sense of ideal body image, adolescents and young adults try to lose or gain body weight to attain perfect body. The objective of the study is to find out the proportion of students dissatisfied with their body image, and the association of various determinants with body image dissatisfaction and self-esteem. Methods: A cross-sectional study was done among 125 first year medical students located in rural Haryana. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data on various determinants associated with body image di...

Body image perception can influence the person in a different way such as psychologically, emotionally, and so on, affecting their self-esteem and causing. Adolescents suffering from body image dissatisfaction have a high chance to increase negative thoughts among themselves such as getting addicted to alcohol, and drugs, unhealthy body transformation treatments and medicines, and suicide. There is an immediate need to counsel these adolescents and to implement primary intervention and psycho-educational interventions. The present study mainly focuses on gender differences and the relationship between body image and self-esteem among adolescents, aged 14 to 18 in Mysuru. This study incorporated 60 participants including 30 males and 30 females. Snowball sampling was used to receive the information from the samples and the tools used for the data collection were Body-Image Questionnaire (BI), and Rosenberg self-esteem questionnaire, and the following information was analyzed using SPSS software and involved the Chi-Square test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Spearman's correlation coefficient. The findings showed that among adolescents, there is a considerable positive association between body image and self-esteem. Also, there is a big disparity in self-esteem and body image between the sexes. The study's findings suggest that effective intervention strategies, such as counseling, are necessary, health, and physical education should be practiced in schools, colleges, and society. The implications of the results were discussed and further suggestions were made for future studies.

Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 2021

The present endeavour was undertaken to compare the Body-Esteem and Self-concept among young boys and girls. A sample of 200youth aged between (15-24) years of Jaipur city was taken for the study. The sample comprised of an equal number of boys (n = 100) and girls (n = 100) respondents. The sample was selected by the means of the Convenience Sampling method. The data for the present study were obtained with the help of Body Esteem scale (Frost et al., 2018) and Self-Concept Scale (Deo, 2011).To achieve the objective of the study, a Between-group design was created. Moreover, the analysis of the obtained data was done with the help of an independent-sample test. The results of the study showed significantly higher Mean scores on Weight concern and Physical condition among girls when compared with boys. Moreover, on the self-concept scale, Boys obtained significantly higher Mean scores on emotions, Character, and Aesthetic dimensions when compared with girls. The findings have future implications.

Kwartalnik Naukowy Fides et Ratio

Introduction: Motherhood is an amazing experience for a woman. It turns out, however, that the joy of having a baby is often accompanied by a negative body image and, at the same time, a reduction in self-esteem. Method: The study sample consisted of 60 puerperal women. A personal questionnaire was used to collect information related to pregnancy, family situation. The body image was verified with the Body Esteem Scale (BES), and the MSEI Multidimensional Self-Assessment Questionnaire was used to test the self-esteem. The research was conducted in the first three quarters of 2019 in Poland. Results: 66.7% of the mothers surveyed gave birth without complications, 53.3% breastfed their babies. Among women for whom appearance is very important, the lowest weight gain was observed during pregnancy. The relationship between the body image in all its dimensions and the support obtained from relatives has been proven (p=0.001 to 0.036). It has been proved that the type of feeding the child...

International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 2020

Physical attractiveness is how an individual’s physical appearance is assessed in terms of beauty or aesthetic qualities. In socio-psychological literature, it is known that people with low self-esteem tend to evaluate themselves poorly in comparison with others. The goal of the current study is to examine how a person’s self-esteem and body-esteem influences one’s perception of the physical attractiveness of himself/herself and of other people, especially when one’s physical appearance is made salient. A questionnaire was administered to 123 high school students. This was comprised of socio-demographic profile, Rosenberg’s (1965) self-esteem scale, Franzoi and Shield’s (1984) Body-esteem scale, and Measures of Physical Attractiveness. The subjects were then divided into a control and treatment group following a matched-pairs design. They were further divided into The second part is comprised of nine photographs of other people of similar age which the subjects were asked to rate ba...

Introduction: Although body image is a crucial part of the human development structure, there are few psychological publications regarding this subject. For a better perception of the body image, there must be a very clear notion about the way the individual feels about himself. Body image dissatisfaction is present in boys and girls, leading to self-esteem decrease. Self-perception and body image become critical for a proper development in youth, making the period very important. Objectives: This study is investigating the way in which dissatisfaction is linked to body weight and shape differentiates preadolescents’ self-esteem. The aim is to investigate the way in which social self-esteem in preadolescents has certain differences between genders in preadolescents and certain characteristics such as body mass perception, real body mass image and desired body mass image. Methods: 60 girls and 60 boys with ages between 11 and 14 years old, all of them with the same educational level,...

Historia mea vita, 2020

Safety Science, 2019

Introducción a la Economía Financiera, 2023

Glasnik DKS 19, 1995

Lebende Sprachen, 2009

Allergology International, 2000

Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 2007

Dijital Mahremiyetin Boyutları: Dijital Alanda Araştırmalar ve Tartışmalar, 2024

Emilia Iffa Suciani , 2024

Teoría y Práctica de la Arqueología Histórica Latinoamericana, 2020

International Journal of Frontiers in Life Science Research

Artificial Organs, 2018

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Self-esteem, body esteem and body image: Exploring effective solutions for ‘at risk’ young women

Low self-esteem and dissatisfaction with weight and looks is common amongst young people. Particularly for girls, low self-esteem and poor body image have been identified to be risk factors for development of eating disorders. This thesis sought to answer two broad aims. The first aim was to explore if a specific group based intervention (“Girls on the Go!” program), led by health professionals and delivered from a community setting increased self-esteem and related self-perceptions and behaviours in ‘at risk’ school age girls compared to no intervention. The second aim was to identify if interventions designed to improve self-esteem of girls improve their self-esteem compared to no interventions. Five key studies comprised this project.

Study 1 was a retrospective investigation of an existing pre- program/ post-program evaluation dataset of the “Girls on the Go!” program collected over the first 8 years of program provision at Greater Dandenong Community Health Services. Participants were 176 girls (age range 10-17) from 15 programs (each comprising 7-11 girls).The program was successful in improving self-esteem ( p p p Study 2 and Study 3 .

For Study 2 and Study 3 participants were girls between 10 and 17 years of age from 12 schools, either high school participants for Study 2 or primary school participants for Study 3 . Eligibility criteria for girls to be referred to the “Girls on the Go!” program and also to be included in the study were: poor or negative body image, low self-esteem, inactivity in sports and exercise, poor diet, or being overweight or underweight. Both Study 2 and Study 3 were stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial of the “Girls on the Go!” program intervention that used the waiting list for the program to generate the control condition. Measurements were made using Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale , Clinical Interview Assessment , Self-Efficacy Scale (included: Mental Health and Physical Health Self-Efficacy Scales), Body Esteem Scale , and the Dutch Eating Behavio u r Questionnaire for Children . Outcomes were compared between groups using linear mixed models, suitable for analyzing longitudinal data where there is likelihood of missing data or loss to follow-up. Data was clustered by school to account for dependency between observations from students from the same school. The intervention led to a significant increase ( p < .05) in self-esteem and self-efficacy (mental and physical health self-efficacy subscales), for both primary and secondary school-aged participants and reduced dieting behaviours (secondary school participants). These gains were retained after 6 months of follow-up.

The aim of Study 4 was to explore whether the effect of “Girls on the Go!” intervention was consistent across high school and primary school participant girls from Study 2 and Study 3. A participant-level meta-analysis was conducted. Participant level meta-analysis allowed for a more powerful and reliable examination of treatment effects across high school and primary school participants from the two studies. Pooled data analysis findings indicate that exposure to the intervention had a positive and equal impact on participants’ self-esteem and self-efficacy including mental health self-efficacy and physical health self-efficacy. Interaction effects revealed self-esteem, physical health self-efficacy and mental health self-efficacy scores did not change from the time they completed the program to the subsequent follow up assessments, which indicated medium to long term stability of these measures as a result of the intervention.

The objectives of Study 5 were to systematically identify and synthesise evidence of effectiveness from randomised trials of interventions aimed at improving self-esteem and related outcomes (body satisfaction, dieting, physical activity self-efficacy) amongst girls, and to identify characteristics of programs that are more effective. A literature search was conducted up to November 2015. Six papers were eligible for inclusion. Most interventions (except Tirlea et al., 2016) were implemented in the school environment and adopted either a direct or indirect self-esteem component to enhance self-esteem and prevent disordered eating. Most studies’ interventions were mainly facilitated by trained teachers, (except Tirlea et al., 2016) targeted at universal audiences of mixed genders and ranging in age between 13.06 to 15.84 years old. The pooled effect size, using the lower and upper ICC, for self-esteem were 0.27 (95% Confidence Intervals [CI], 0.16, 0.38), and at short term follow up for self-esteem were 0.21 (95% CI, 0.06, 0.37) for body satisfaction were 0.22 (95% CI, 0.11, 0.34) and physical health self-efficacy was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.14, 0.44) respectively. These results support the implementation of interventions aimed at increasing levels of self-esteem.

The clinical implications of studies 1-4 are that providing preventive health services to young women at risk of disordered eating and other health concerns can potentially be achieved using a holistic program such as “Girls on the Go!” that focuses on promoting self-esteem, health and well-being. The results of study 5 (systematic review and meta-analyses) demonstrated there is support for the implementation of interventions aimed at increasing levels of self-esteem in girls. There was a trend for interventions that have a self-esteem component to also improve body satisfaction.

Little research has investigated the role of self-esteem and self-esteem interventions effectiveness to prevent negative consequences associated with poor self-esteem. This thesis provided a summary of existing literature of self-esteem risk factors and self-esteem interventions effectiveness. The present evaluation results provide evidence base for the “Girls on the Go!” program effectiveness and suggests that a health education program that promotes positive change in how one thinks about the self and their body may achieve the healthy lifestyle changes needed to maintain a long and happy life free of eating disorders.

The Butterfly Foundation

Principal supervisor, additional supervisor 1, year of award, department, school or centre, campus location, degree type, usage metrics.

- Applied and developmental psychology not elsewhere classified

- Health promotion

- Mental health services

- Epidemiology not elsewhere classified

- Health and community services

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Impact of Self-Esteem and Self-Perceived Body Image on the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery

Hussain a al ghadeer, maisa a alalwan, mariyyah a alamer, fatimah j alali, ghadeer a alkhars, shahad a alabdrabulrida, hasan r al shabaan, adeeb m buhlaigah, mohmmed a alhewishel, hussain a alabdrabalnabi.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Hussain A. Al Ghadeer [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2021 Sep 30; Collection date 2021 Oct.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Cosmetic surgery is the preservation, rebuilding, or improvement of the physical appearance of an individual through surgical and non-surgical methods. In the last few years, an increase in the number of cosmetic procedures was noticed worldwide. This increase suggests due to multifactorial changes in people’s attitudes towards cosmetic surgery and concern about their physical appearance. This study aims to assess the impact of self-esteem and self-perceived body image on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery and other related factors in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia.

Material and methods

This was a cross-sectional study carried out in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia. The study was conducted between May and August 2021. A self-administrated questionnaire was distributed to all the participants who are attending plastic surgery clinics and online through social media. Three valid and reliable scales were used [Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS), Body Appreciation Scale (BAS), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE)] to assess the relationship between these variables and other factors. The data were analyzed by using two-tailed tests. P-value less than 0.05 was statistically significant. Correlation analysis was done by using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r).

A total of 1008 participants were included in the study with a response rate of 67%. Participant's ages ranged from 18 to 54 years with a mean age of 34.7 ± 11.2 years old. The study participants showed an average level of acceptance with a mean score % of 55.4% comparing to body appreciation; it was 74.2% higher with a more than average level of self-esteem, 24.7 out of 40 points for self-esteem with a mean score of 61.8%. Participants with a history of cosmetic surgery had significantly higher acceptance score than who did not (mean score of 72.6 compared to 57.1; P=0.001). Male participants had better body appreciation than females (mean score of 50.2 vs. 47.6, respectively; P=0.013). A weak positive correlation with no significance was found between participants’ self-esteem and their acceptance of cosmetic surgery.

A better understanding of the acceptance of cosmetic surgery from a different cultural perspective and other related factors including social, psychological, and self-esteem are crucial for the plastic surgeon to ensure patient satisfaction.

Keywords: cosmetic surgery, body appreciation, plastic surgery, self-esteem, saudi arabia

Introduction

Cosmetic surgery is the preservation, restoration, or improvement of a person's physical appearance which includes changes in any part of the body. It is done by surgical and medical techniques in the presence or the absence of any diseases, injuries, or congenital defects [ 1 , 2 ]. Cosmetic surgeries were done previously for people who need reconstruction of some congenital lesions. Later on, the purpose of applying cosmetic surgery was increased and changed to be more focused on beauty purposes and reversing the effects of aging. This can be due to the high impact on beauty by people nowadays [ 3 ]. Worldwide, there has been a huge increase in the prevalence of cosmetic surgeries over the past 10 years [ 2 ]. This increase in the prevalence of cosmetic surgery indicates that there is a significant change in people's perception and acceptance of cosmetic surgery [ 4 ]. According to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS), the total surgical and nonsurgical procedures increased by 7.4% in 2019 compared to 2018 statistics. Patients who seek cosmetic surgeries vary in gender and age. However, the prevalent groups seeking cosmetic surgery are females aged 35-50 years old. Globally, the most common surgical procedures in women were breast augmentation, liposuction, and eyelid surgery, in contrast to men, gynecomastia, eyelid surgery, and liposuction was the most common. The most popular nonsurgical procedures for both genders are botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid, and hair removal. However, among the top 30 countries with the highest rates of plastic surgery in the world, Saudi Arabia ranks 29 [ 5 ]. The prevalence of Saudi females who seek cosmetic surgery is increased dramatically over the last few years [ 6 ]. There are lots of factors that make a person decide between seeking cosmetic surgery and consequently increase the rate of cosmetic procedures. These factors can be summarized into three main categories: the characteristics of the patient, the general surrounding of the patient, and the huge development and accessibility of the medical field [ 7 ]. The first category: the characteristics of the patient which represents the demographical data of the patient such as age, gender, economic status, and educational level. There was a study conducted in Iran which showed that these demographical data affect the decision to make a cosmetic surgery [ 8 ]. The physical status, BMI of the patient, psychological status, and the personality of the patient which represents stress, body image, self-esteem, body dysmorphic disorder, and confirmatory can affect the decision of seeking cosmetic surgery. Another Iranian study showed that self-esteem, body image dissatisfaction, and conformity are effective in the acceptance of cosmetic surgery [ 9 ]. The second category: the general surrounding of the patient which is characterized by the culture of the country and the social media. A systemic review was done to emphasize the huge effect of cultural differences and social media on seeking a cosmetic procedure [ 10 ]. Also, there was a study conducted in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia suggests that social media has a high impact on body appreciation and deciding to perform cosmetic surgery [ 11 ]. The third category: the huge development and accessibility of the medical field which is characterized by the huge increase of cosmetic centers and plastic surgeons all over the world. Many types of research have been done to find the relationship between these factors and seeking cosmetic surgery. In this research, it is focused on the impact of self-esteem and self-perceived body image on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery and other associated factors among the citizen of the Eastern province, Saudi Arabia.

Materials and methods

This study aims to evaluate the impact of self-esteem and self-perceived image on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery and body satisfaction among Saudi citizens in the Eastern region.

Study design and participates

A cross-sectional-based study was conducted in the period between May and August 2021. The study population was Saudi citizens who live in the eastern province aged 18 years old and older.

Data collection instrument and procedures

A questionnaire was fulfilled by whom attending plastic surgery clinic and distributed online through social media. Verbal and written consent was obtained from the participant after explaining the purpose of this study. Study objectives guided a self-administered questionnaire. The survey covered four sections through several validated scales used for different specific purposes. The first section included demographic data, such as sex, age, marital status, educational, and family income. The scales used included the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS), Body Appreciation Scale (BAS), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale. The data were collected by using validated questionnaires modified for Arabic speakers.

Demographics

All participants provided their gender, age, education, job, and marital status, income, and whether they underwent cosmetic surgery or not.

To measure the acceptance of cosmetic surgery in this study, ACSS was used as a validation scale that was modified for Arabic speakers for the measurement of attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. It is a 15 based on a 7-points scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). ACSS runs in three subscales with five items each. The Intrapersonal scale has five items, which assesses the degree to which an individual believes that cosmetic surgery will add to their self-image. The Social subscale has five items, which measures whether an individual would undergo cosmetic surgery for social reasons. Finally, the Consider subscale has five items, which measure the likelihood that an individual will consider having cosmetic surgery. ACSS score ranges from 15 to 105. The higher scores on the sub-scales and the total scale indicate more of a positive attitude toward cosmetic surgery [ 12 , 13 ].

The BAS is a 13 on 5-points scale (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). It is used to assess body appreciation. Participants are asked to select the five options on statements such as "I feel that my body has at least some good qualities" and "My self-worth is independent of my body shape or weight." The average is calculated to obtain an overall body appreciation score. The higher the score, the more body appreciation is scored. The BAS has been shown to have good discriminant, construct, and incremental validities. Among Arabs countries, the BAS has been shown to have good discriminant, constructive, and incremental validities [ 14 , 15 ].

The RSE scale has 10 items on a four-point scale used widely to assess self-worth. The questionnaire was answered on Likert's four points (0 = strongly disagree, 3 = strongly agree). This scale has five negative items required to be reversed before the calculation of the total score. A higher score indicated higher SE. This scale is reliable and valid and used in different studies including the Arabic version [ 16 - 18 ].

Data analysis

After data were extracted, it was revised, coded, and fed to statistical software IBM SPSS version 22 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL). All statistical analysis was done using two-tailed tests. P-value less than 0.05 was statistically significant. For different scales, the overall score was obtained after summing up all discrete items scores after reversing scores for negative statements (in self-esteem scale); then, score percent of maximum was calculated through dividing the overall score by the maximum score for each scale. Descriptive analysis based on frequency and percent distribution was done for all variables including demographic data, and cosmetic surgery history. Mean score and score % with standard deviation were calculated for self-esteem, cosmetic surgery acceptance, and body appreciation scales. The distribution of measured scales by participant's socio-demographic data was assessed using ANOVA test and independent t-test for significance. Correlation analysis was done to assess the relationship between participant's acceptance of cosmetic surgery, body appreciation, and their self-esteem using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r).

The survey was administered to 1500 eligible participants; 1008 responded (67% response rate). Participant's ages ranged from 18 to 54 years with a mean age of 34.7 ± 11.2 years old. The majority of respondents were females (73.5%; 741) and 768 (76.2%) were married. As for educational level, 860 (85.3%) participants were university graduated. As for work, 339 (33.6%) were not employed while 383 (38%) were non-healthcare workers and 286 (28.4%) were health care workers. A monthly income of 5000-10,000 SR was reported among 319 (31.6%) while 405 (40.2%) had a monthly income of 10,000-20,000 SR. Exactly, 160 (15.9%) participants had chronic health problems (Table 1 ).

Table 1. Sociodemographic data of study participants.

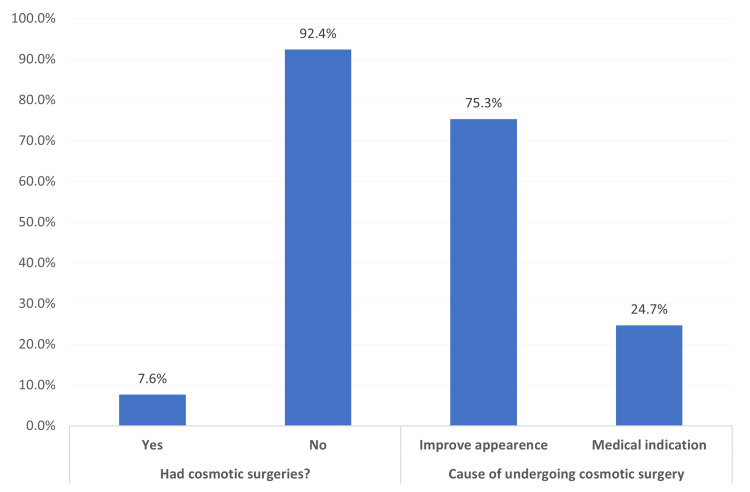

Figure 1 shows the history of cosmetic surgery and related causes among the population in the eastern region, Saudi Arabia. The exact 77 (7.6%) respondents reported undergoing cosmetic surgery. Among those who had undergone the surgery, improving appearance was reported by 58 (75.3%) while 19 (24.7%) reported undergoing the surgery for a medical indication.

Figure 1. History of cosmetic surgery and related causes among the participants.

Table 2 illustrates descriptive of acceptance of cosmetic surgery, body acceptance, and self-esteem among study participants. As for acceptance of cosmetic surgery, the study participants showed an average level of acceptance with a mean score % of 55.4% (58.2 out of 105 points). As for body appreciation, it was high among the study respondents where the average score % was 74.2% (48.2 out of 65 points). The study participants showed more than the average level of self-esteem where they reported 24.7 out of 40 points for self-esteem with a mean score % of 61.8%.

Table 2. Descriptive of acceptance of cosmetic surgery, body acceptance, and self-esteem among study participants.

Table 3 shows the distribution of participant's acceptance of cosmetic surgery by their socio-demographic data. The acceptance average score was significantly higher among old-aged participants (>45 years) than the young age group (mean score of 66.1 versus 51.9, respectively; P=0.001). Also, a mean score of 63.3 was reported for the divorced/widow group in comparison to 52.5 for single participants (P=0.001). Participants with chronic health problems had significantly higher acceptance scores than others (mean score of 62.2 vs. 57.5, respectively; P=0.008). Participants who had undergone cosmetic surgery had significantly higher acceptance scores than others (mean score of 72.6 compared to 57.1; P=0.001). Also, acceptance for cosmetic surgery was higher among those who had undergone the surgery to improve appearance than others who had undergone the surgery due to medical indications.

Table 3. Distribution of participants acceptance of cosmetic surgery by their sociodemographic data.

# Independent samples t-test

^One way ANOVA

*P < 0.05 (significant)

Table 4 reveals the distribution of participant's body appreciation by their socio-demographic data. Body appreciation was significantly higher among male participants than females (mean score of 50.2 vs. 47.6, respectively; P=0.013). Also, married participants had a significantly higher level of body appreciation than single (mean score of 49.2 and 44.7, respectively; P=0.001). The highest level of body appreciation was reported among non-employed respondents than the employed group (50.1 vs. 47.3 and 47.1; P=0.001). Other factors were insignificantly associated with the participant's level of body appreciation.

Table 4. Distribution of participants body appreciation by their sociodemographic data.

Table 5 shows the distribution of participant's self-esteem by their socio-demographic data. The only significant factor that affected participant's self-esteem was their educational level where participants with lower education had a significantly higher level of self-esteem (means score of 25.6 vs. 24.0 and 24.7; P=0.009).

Table 5. Distribution of participants self-esteem by their sociodemographic data.

Table 6 illustrates a correlation between participant's acceptance of cosmetic surgery, their body appreciation, and self-esteem levels. There was an insignificant weak positive correlation between participants’ self-esteem and their acceptance of cosmetic surgery (r=0.052). On the other hand, participants showed a significant inverse correlation between appreciation of their bodies and acceptance of cosmetic surgery (r=−0.027; P=0.035). Also, there was a significant positive weak correlation between participant's body appreciation and their self-esteem (r=0.179; P=0.001).

Table 6. Correlation between participants acceptance of cosmetic surgery, their body appreciation, and self-esteem levels.

**P < 0.01 (highly significant)

The main aim of conducting the current research was to assess the prevalence of cosmetic surgery among populations and also to explore the factors of cosmetic procedures affecting the eastern province in Saudi Arabia. Estimating the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and the decision to seek cosmetic surgery was also explored. Cosmetic surgery has been undergone mainly for maintenance, repair, or improvement of a person's physical appearance through surgical and medical techniques [ 3 ]. Reference to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery that total revenue of over $9 billion was spent on aesthetic procedures in 2020 [ 19 ]. Recently, the decision to undergo plastic surgery attracted a noteworthy expanse of attention. Researches have intensive on psychosocial, evolutionary, and health behavioral factors among those who have undergone cosmetic surgery [ 20 ]. Besides, more perceptual and belief issues include quality of life, self-esteem, and body image [ 21 ]. A full assessment by Ching et al. [ 22 ] reported that a patient’s body image and perceived quality of life were the most important and reliable factors of aesthetic surgery outcomes.

The current study showed that very few percent of the study participants (about 1 out of each 12) had undergone cosmetic surgery. The main reason (three quarters) was to improve appearance while only one quarter had undergone the surgery due to medical indication. This was much lower than what was estimated by Alharethy [ 23 ] who reported that 26.2% of Saudis participants underwent a laser hair removal, 19% underwent a Botox procedure, and 14.3% underwent liposuction. Also, the authors found that most participants (31%) had a cosmetic procedure to look more beautiful which is lower than the current study reported rate.

Regarding cosmetic surgery acceptance, the current study showed that participants had an average acceptance rate for cosmetic surgery (about half with high acceptance). The acceptance rate for undergoing cosmetic surgery was significantly higher among old-aged participants, unmarried groups, and those with chronic health problems. Also, participants who had undergone the surgery reported a higher acceptance rate which means they were ready for the procedure especially those who had undergone to improve their appearance. Lunde [ 24 ] revealed that younger respondents showed higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery. This was especially the case for boys’ acceptance of social motives for obtaining cosmetic surgery in contrast to the current study findings. Although the majority of the participants of this study are female, no significance was seen between the gender for the acceptance of cosmetic surgery. South Korea [ 25 ], Iran [ 26 ], and Brazil [ 27 ] reported that females had the intention of undergoing cosmetic surgery.

Other factors behind the interest in cosmetic surgery were reported by Javo et al. [ 28 ] in Norway. These factors included dysmorphic disorder such as symptoms, body image orientation, having children, been teased for appearance, knowing someone who has had cosmetic surgery, and being advised for cosmetic surgery. Agreeableness, body image perception, education were negatively related to an interest in cosmetic surgery. Alotaibi conducted a systematic review to assess demographic and cultural differences in the acceptance of cosmetic surgery [ 10 ]. The review showed that the search for beauty through cosmetic surgery is a worldwide phenomenon, while different countries, races, and cultures differ in how readily cosmetic surgery is comprised, and in the aesthetic goals of those choosing to have it. Also, women covering crudely 90% of all cosmetic surgery patients in virtually all populations studied and consistently exhibiting greater CS knowledge and acceptance.

The current study also showed that body appreciation was very high among participants which explains the low rate of seeking cosmetic surgeries and average acceptance rate for the surgery. Irrespective of that, self-esteem was not high in acceptable rate where about one-third of the respondents had high self-esteem. There was a significant association between high self-esteem and high weight appreciation among participants. This means that one’s confidence in their body image improves their self-esteem and lowers their acceptance of cosmetic surgery. These findings were concordant with other studies that covered cosmetic surgery acceptance issues and their related factors including self-esteem and body image perception [ 29 , 30 ].

Conclusions

Being aware of the reasons and motivations that make the individual considering cosmetic procedures is important for plastic surgeons for relevant outcomes in terms of psychosocial, satisfaction, and self-esteem. This is the first study in Saudi Arabia that assesses the impact of self-esteem and self-perceived on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. We hope that our findings encourage other researchers to do more studies within different cities.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. King Fahad Hospital-Hofuf, Al-Ahsa Saudi Arabia issued approval 25-EP-2021. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants after describing the aim of the study, and the participants had autonomy for rejection. Privacy and confidentiality of results maintained. Official permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Fahad Hospital-Hofuf, AlAhsa, Eastern province of Saudi Arabia.

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

- 1. Cosmetic surgery in the NHS: applying local and national guidelines. Breuning EE, Oikonomou D, Singh P, Rai JK, Mendonca DA. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1437–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.08.012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: personality and individual difference predictors. Swami V, Chamorro-Premuzic T, Bridges S, Furnham A. Body Image. 2009;6:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.09.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Swami V, Furnham A. London: Routledge; 2007. The Psychology of Physical Attraction. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. The acceptance of cosmetic surgery scale: confirmatory factor analyses and validation among Serbian adults. Jovic M, Sforza M, Jovanovic M, Jovic M. Curr Psychol. 2017;36:707–718. doi: 10.1007/s12144-016-9458-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. ISAPS international survey on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures in 2019. [ Sep; 2021 ]; https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Global-Survey-2019.pdf 2019

- 6. Predictive factors for cosmetic surgery: a hospital-based investigation. Li J, Li Q, Zhou B, Gao Y, Ma J, Li J. Springerplus. 2016;5:1543. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3188-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Crerand CE, Franklin ME, Sarwer DB. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:167–180. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000242500.28431.24. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Relationship between socioeconomic factors and incidence of cosmetic surgery in Tehran, Iran. Bidkhori M, Yaseri M, Akbari Sari A, Majdzadeh R. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50:360–368. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i2.5351. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: body image, self esteem and conformity. Farshidfar Z, Dastjerdi R, Shahabizadeh F. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013;84:238–242. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Demographic and cultural differences in the acceptance and pursuit of cosmetic surgery: a systematic literature review. Alotaibi AS. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:0. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003501. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. The impact of social media engagement on body image and increased popularity toward seeking cosmetic surgery. Al-Yahya T, AlOnayzan AH, AlAbdullah ZA, Alali KM. IJMDC. 2020;4:1887–1892. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: scale development and validation. Henderson-King D, Henderson-King E. Body Image. 2005;2:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery among females in Princess Nora Bint Abdulrahman University. Alsumali K, Al Shammari RA, Al Shammari SM, et al. Int J Adv Res. 2018;6:1543–1544. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. The Body Appreciation Scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. Body Image. 2005;2:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. The factor structure and psychometric properties of an Arabic-translated version of the Body Appreciation Scale-2. Vally Z, D'Souza CG, Habeeb H, Bensumaidea BM. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55:373–377. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12312. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Rosenberg Rosenberg, Morris Morris. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2015. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Validity and reliability of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale-Thai version as compared to the Self-Esteem Visual Analog Scale. Piyavhatkul N, Aroonpongpaisal S, Patjanasoontorn N, Rongbutsri S, Maneeganondh S, Pimpanit W. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21774294/ J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:857–862. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Self-esteem and quality of life in adolescents with extreme obesity in Saudi Arabia: the effect of weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Aldaqal SM, Sehlo MG. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Aesthetic plastic surgery national databank statistics for 2020. [ Sep; 2021 ]; https://cdn.theaestheticsociety.org/media/statistics/aestheticplasticsurgerynationaldatabank-2020stats.pdf . 2020 doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab178. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 20. Psychosocial and health behavioural covariates of cosmetic surgery: women's health Australia study. Schofield M, Hussain R, Loxton D, Miller Z. J Health Psychol. 2002;7:445–457. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007004332. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and body image: a psychosocial evaluation of aesthetic and reconstructive surgery candidates. Ozgür F, Tuncali D, Güler Gürsu K. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998;22:412–419. doi: 10.1007/s002669900226. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Measuring outcomes in aesthetic surgery: a comprehensive review of the literature. Ching S, Thoma A, McCabe RE, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:469–482. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000036041.67101.48. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Trends and demographic characteristics of Saudi cosmetic surgery patients. Alharethy SE. Saudi Med J. 2017;38:738–741. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.7.18528. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery, body appreciation, body ideal internalization, and fashion blog reading among late adolescents in Sweden. Lunde C. Body Image. 2013;10:632–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Factor structure and correlates of the acceptance of cosmetic surgery scale among South Korean university students. Swami V, Hwang CS, Jung J. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32:220–229. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11431577. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Role of attitude, body image, satisfaction and socio-demographic variables in cosmetic surgeries of Iranian students. Kasmaei P, Farhadi Hassankiade R, Karimy M, Kazemi S, Morsali F, Nasollahzadeh S. World J Plast Surg. 2020;9:186–193. doi: 10.29252/wjps.9.2.186. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. The Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale: initial examination of its factor structure and correlates among Brazilian adults. Swami V, Campana AN, Ferreira L, Barrett S, Harris AS, Tavares Mda C. Body Image. 2011;8:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.01.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Psychosocial predictors of an interest in cosmetic surgery among young Norwegian women: a population-based study. Javo IM, Sørlie T. Plast Surg Nurs. 2010;30:180–186. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bcf290. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. Chen J, Ishii M, Bater KL, et al. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21:361–367. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Interest in cosmetic surgery among Iranian women: the role of self-esteem, narcissism, and self-perceived attractiveness. Kalantar-Hormozi A, Jamali R, Atari M. Eur J Plast Surg. 2016;39:359–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (185.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 October 2024

Mediating effect of depression between self-esteem, physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating in adults

- Emmanuelle Awad 1 ,

- Diana Malaeb 2 ,

- Nancy Chammas 3 ,

- Mirna Fawaz 4 ,

- Michel Soufia 3 ,

- Souheil Hallit 3 , 5 , 6 na1 ,

- Anna Brytek-Matera 7 na1 &

- Sahar Obeid 8 na1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 25109 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Health care

The first aim of the study is to clarify the associations between intuitive eating, self-esteem, physical appearance and psychological distress; and second, to assess the mediating effect of psychological distress on the relationship between self-esteem/physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating. A total of 359 Lebanese participants from several Lebanese governorates were enrolled in this cross-sectional study between September and November 2022. The data was collected through an online questionnaire that included the following scales: Intuitive Eating Scale‑2, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and Physical Appearance Comparison Scale. The results of the mediation analysis showed that depression partially mediated the association between self-esteem / physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating. Higher self-esteem was significantly associated with lower depression; higher depression was significantly associated with more intuitive eating. Also, higher self-esteem was directly and significantly associated with more intuitive eating. On another hand, higher physical appearance comparison was significantly associated with higher depression; higher depression was significantly associated with more intuitive eating. Finally, higher physical appearance comparison was directly and significantly associated with less intuitive eating. The current study shows how significantly intuitive eating, an adaptive eating pattern, and psychological variables are interrelated and possibly affect each other. It helps shed light on intuitive eating, a somewhat unfamiliar eating pattern within the Lebanese population. These findings allow practitioners to promote healthy eating behaviors and psychological health by educating and guiding patients and clients about intuitive eating.

Similar content being viewed by others

The relationship between orthorexia nervosa symptomatology and body image attitudes and distortion

Abnormal sense of agency in eating disorders

Psychometric analysis of the body responsiveness questionnaire in the Portuguese population

Introduction.

Intuitive eating is an adaptive eating pattern that has been receiving increasing recognition in the fields of nutrition and psychology recently 1 . Associated with a healthy lifestyle, it can be defined as consuming food with no restrictions until a feeling of satiety is reached 2 . Additionally, it involves an element of awareness and consciousness: the person is driven to eat by the physical need of hunger, instead of other emotional motives 2 . Therefore, the act of eating is motivated by the body’s physiological demands.

Also related to a healthy lifestyle is self-esteem, which has been associated with a lower risk of engaging in maladaptive eating patterns 3 . Self-esteem can be defined as one’s self-worth and personal view of one’s competence 4 . Moreover, higher self-esteem was found among those who exhibited healthier eating behaviors in comparison with others 5 . Similarly, a positive relationship was found between self-esteem and healthy eating behaviors in a sample of college students 6 . Identified as a healthy eating behavior, intuitive eating also showed a positive association with self-esteem 1 .

Another factor guiding eating patterns is physical appearance-based social comparison 7 . Physical appearance comparison is considered a form of social comparison, where an individual contrasts their own physical attributes to that of others 8 . Research has shown that a high level of physical appearance comparison is significantly related to eating pathology 9 . Furthermore, physical comparison was associated with variance in maladaptive eating behaviors consistently across genders 10 . In one study on adolescent girls specifically, comparing one’s appearance to others had a negative relationship with intuitive eating 11 .

Intuitive eating also had a connection with psychological distress: engaging in intuitive eating was linked to lower psychological distress 12 . Overall, intuitive eating is positively correlated with positive psychological constructs and negatively correlated with psychological distress 1 . A study that investigated dieting, unhealthy eating and intuitive eating found that intuitive eating was the least associated with psychological distress 2 . In addition, concern about one’s appearance and depression were both connected to maladaptive eating patterns 2 .

According to the literature, psychological distress factors, specifically depression, have played a mediating role between maladaptive eating patterns and other factors, including the relationship between excessive social media use and bulimia nervosa 13 . Additionally, depression mediated the relationship between externalizing disorders and eating disorders 14 , as well as emotion regulation and maladaptive eating patterns 15 . These results further clarify the potential indirect effect of psychological distress on eating patterns. At the same time, some findings have suggested that depressive symptoms do not show a direct relationship with dietary patterns 16 .

Intuitive eating is relatively novel domain in research, in comparison with that conducted on maladaptive eating patterns or eating pathology. The factors promoting eating pathologies, which are unhealthy eating practices, have been studied extensively over the course of the past few years 17 , and the investigation is still ongoing 18 , 19 . While many studies have established the links between self-esteem 19 , physical appearance-related variables 20 and psychological distress 21 with eating pathology, these links remain scarce and require further probing when discussing intuitive eating, an adaptive eating pattern.

A scale assessing intuitive eating behaviors was validated in Lebanon recently 22 , and adaptive eating patterns have been investigated in the Lebanese population as of late 23 . Many factors are involved in the dietary patterns of Lebanese people including food insecurity that are affected by level of income 24 , given that Lebanon suffers from many economic crises, which might cause low food intake despite cues of hunger.

Previous evidence suggests that depression and self-esteem mediated the relationship between body dissatisfaction and maladaptive eating behaviors 25 . These results might drive more research to assess the possible mediating role of psychological distress between positive psychological variables such as self-esteem and intuitive eating. Considering the multiple factors mentioned above, including the associations between intuitive eating and self-esteem and physical appearance comparison, the indirect effect of psychological distress on eating patterns and the lack of research on intuitive eating in Lebanon, the current aims of the study are (1) to clarify the associations between intuitive eating, self-esteem, physical appearance and psychological distress, and (2) to assess the mediating effect of psychological distress on the relationship between self-esteem/physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating. This investigation could help bridge the existing gap in the literature about the potential integration of the variables mentioned, as well as further guide researchers and practitioners towards a holistic approach regarding psychological factors, given that the literature does not present explicit findings about the indirect effect of psychological distress on the relationship between intuitive eating, self-esteem and physical appearance.

Study design

A total of 359 Lebanese participants were enrolled in this cross-sectional study (mean age: 22.75 ± 7.04 years, 40.1% males), conducted between September and November 2022, through convenience sampling in several Lebanese governorates (Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North Lebanon, South Lebanon, and Bekaa). The survey was a Google form questionnaire that was administered through the internet, using the snowball technique. To reach the largest possible group of subjects, the research team initiated the contact with friends and family members they know; those people were asked to forward the link to their friends and family members, and were asked to forward the link to their contact list via social media applications such as WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Instagram. Before proceeding with the questionnaire, participants were informed of the purpose of the study, assured of the anonymity of their participation and provided with a virtual informed consent form via ‘Google Forms’. The latter had to be ‘signed’, after reading, by clicking the box ‘Yes, I acknowledge having read the above-mentioned information and I agree to participate in this study voluntarily and without any pressure’ to which the answer is required in order to continue with the self-administration. Participants had the right to accept or refuse to respond and no financial compensation was provided in exchange for their submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics and Research Committee at the Lebanese International University approved this study protocol (2022RC-051-LIUSOP). A written informed consent was considered obtained from each participant when submitting the online form. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Minimal sample size calculation

A minimal sample of 128 was deemed necessary using the formula suggested by Fritz and MacKinnon 26 to estimate the sample size: \(\:n=\frac{L}{f2}+k+1\) , where f=0.26 for small-medium effect size, L=7.85 for an α error of 5% and power β = 80%, and k=11 variables to be entered in the model.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used was anonymous and in Arabic, the native language in Lebanon; it required approximately 20 min to complete. The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part of the questionnaire included an explanation of the study topic and objective, a statement ensuring the anonymity of respondents. The participant had to select the option stating I consent to participate in this study to be directed to the questionnaire. The second part of the questionnaire contained sociodemographic information about the participants (age, sex, marital status, and Household Crowding Index). The Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the self-reported weight and height 27 . The strength, frequency, and duration of physical activity were multiplied to create the physical activity index 28 . The third part included the scales used in this study:

Intuitive Eating Scale‑2 (IES‑2). Validated in Arabic 22 , the IES-2 consists of 23 items 29 such as “If I am craving a certain food, I allow myself to have it” and “I find myself eating when I am stressed out, even when I’m not physically hungry”, rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score was computed by summing up the answers of all questions. Higher mean values refer to higher levels of adaptive, intuitive eating patterns and behaviors (Cronbach’s α in this study = 0.84).

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-8). Validated in Arabic, the DASS-8, a shortened version of the DASS-21, consists of eight items divided into three subscales: depression (3 items), anxiety (3 items), and stress (2 items) 30 . The items include statements like “I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything” and “I felt down-hearted and blue”. Responses to the items are scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). The scale yields three scores for depression, anxiety and stress respectively, with higher scores equate to a higher level of symptoms in each dimension (Cronbach’s α in this study = 0.91).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSS). The RSS 31 was used to evaluate trait self-esteem. It is composed of 10 items, in which 5 items are reversed. This scale is scored as a Likert scale, with a 4-point response from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. Some items from the scale are “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself” and “I certainly feel useless at times”. The Arabic translated version has been used in previous studies 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 (Cronbach’s α in this study = 0.83).

Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (PACS-R). The scale, validated in Arabic 36 , consists of 11 items for unidimensional evaluation of the frequency of comparing one’s own physical appearance with other persons in various social situations 8 . The response format varies from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The scale presents statements like “When I’m out in public‚ I compare my body fat to the body fat of others” and “When I meet a new person (same sex)‚ I compare my body size to his/her body size”. The scale was recently validated in Arabic among the Lebanese population, showing good psychometric quality (Cronbach’s α = 0.97) 37 . Higher scores indicate higher physical comparison (Cronbach’s α in this study = 0.97).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software v.25 was used for the statistical analysis. There were no missing values in our dataset. The intuitive eating score was considered normally distributed since the skewness and kurtosis values varied between − 1 and + 1 38 . The Student t was used to compare two means and the Pearson test was used to correlate two continuous variables. The mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS MACRO (an SPSS add-on) v3.4 model 4 39 ; four pathways derived from this analysis: pathway A from the independent variable (self-esteem/physical appearance comparison) to the mediator (depression/anxiety/stress), pathway B from the mediator (depression/anxiety/stress) to the dependent variable (intuitive eating), Pathways C and C’ indicating the total and direct effects from the independent (self-esteem/physical appearance comparison) to the dependent variable (intuitive eating). Results of the mediation analyses were adjusted over all variables that showed a p < .25 in the bivariate analysis. We considered the mediation analysis to be significant if the Bootstrapped Confidence Interval did not pass by zero. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the sample

Three hundred fifty-nine adults were enrolled (mean age = 22.75 years (SD = 7.04) and 59.9% females). Other descriptive statistics of the sample can be found in Table 1 .

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with intuitive eating

The results of the bivariate analysis of factors associated with intuitive eating are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 . The results showed that higher BMI ( r = − .15) and higher physical appearance comparison ( r = − .19) were significantly associated with less intuitive eating, whereas higher self-esteem ( r = .23) was significantly associated with more intuitive eating.

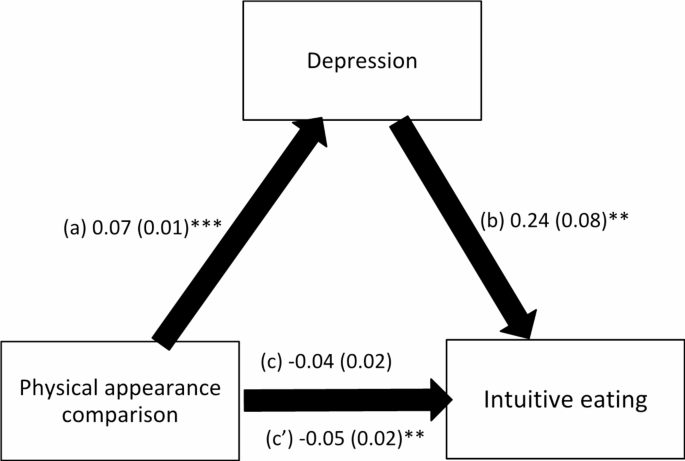

Mediation analysis

The results of the mediation analysis are summarized in Table 4 ; the analyses were adjusted over the following variables: BMI and marital status. The results of the mediation analysis showed that depression partially mediated the association between self-esteem / physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating (Figs. 1 and 2 ). Higher self-esteem was significantly associated with lower depression; higher depression was significantly associated with more intuitive eating. Finally, higher self-esteem was directly and significantly associated with more intuitive eating.

On another hand, higher physical appearance comparison was significantly associated with higher depression; higher depression was significantly associated with more intuitive eating. Finally, higher physical appearance comparison was directly and significantly associated with less intuitive eating.

It is noteworthy that anxiety and stress did not mediate the association between self-esteem / physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating (Table 4 ).

(a) Relation between self-esteem and depression (R 2 = .213); (b) Relation between depression and intuitive eating (R 2 = .100); (c) Total effect of self-esteem on intuitive eating (R 2 = .079); (c’) Direct effect of self-esteem on intuitive eating. Numbers are displayed as regression coefficients (standard error). ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

(a) Relation between physical appearance comparison and depression (R 2 = .213); (b) Relation between depression and intuitive eating (R 2 = .100); (c) Total effect of physical appearance comparison on intuitive eating (R 2 = .079); (c’) Direct effect of physical appearance comparison on intuitive eating. Numbers are displayed as regression coefficients (standard error). ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

The results of the current study show that depression partially mediated the association between self-esteem and intuitive eating. Previous results suggest that other body positive variables impact intuitive eating significantly more than self-esteem 40 , suggesting that the relationship between self-esteem and intuitive eating might be indirect, or that the relationship is insignificant. On the other hand, there is evidence suggesting that the direction of the relationship is related to depression influencing self-esteem in a negative manner 41 . Meanwhile, intuitive eating was related to lower depressive symptoms in other studies 42 , 43 . Depression is a risk factor for maladaptive eating behaviors 44 , therefore, it is logical to assume that the absence of depression or lower depressive symptoms could be associated with a higher probability of healthy eating behaviors. The hypothesis that the presence of depressive symptoms affects self-esteem and intuitive eating independently, and subsequently can act as a mediator could explain the present results.

Also, depression partially mediated the association between physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating. Depression was previously associated with higher appearance sensitivities, which is related to social comparison 45 , within the same domain of physical appearance comparison. There was a direct positive correlation between depression and social appearance anxiety, also related to social comparison 46 . Moreover, appearance-related anxiety was a contributing factor in developing maladaptive eating patterns as well as depression 47 . Based on these findings 47 , we can assume that depression has a significant effect on eating patterns. It can be inferred through the studies mentioned that depression can influence social comparison factors, such as physical appearance comparison, and eating patterns independently. Accordingly, it can be assumed the current finding that depression mediates the relationship between physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating are founded.

It is important to take note that depression was a partial mediator in both mediation models involving intuitive eating. This indicates that the relationship between self-esteem and intuitive eating as well as the relationship between physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating depends partially on depression. To begin with, higher intuitive eating is directly associated with lower depressive symptoms 42 . We can hypothesize that the effect of depression on intuitive eating extends onto other psychological and physiological factors.

Additionally, higher self-esteem was significantly associated with lower depression and higher depression was significantly associated with more intuitive eating. It has been previously established that lower levels of self-esteem have a strong relationship with the onset of depression 48 . Having said that, previous investigation has suggested that the association between depression and eating patterns is not general, but specific aspects of depression are related to maladaptive eating patterns 49 , with lower self-esteem potentially connecting depression and eating patterns. These past findings might explain why the current results connect higher depression with intuitive eating, an adaptive eating pattern. As a possible hypothesis, specific dimensions of depression, such as feeling like a failure, are associated with maladaptive eating patterns 49 , while other dimensions such as diminished or heightened appetite 50 , a symptom of depression, can potentially be associated with eating intuitively. As a result, someone with more depression symptomatology might act in accordance with their heightened or reduced appetite, which we can hypothesize could be confounded with elements of intuitive eating such as only eating when one experiences hunger and stopping when feeling satiety cues.

On the other hand, higher self-esteem was directly and significantly associated with more intuitive eating. The current result is supported by another recent study that found that higher self-esteem and higher intuitive eating were significantly correlated 51 . Moreover, higher intuitive eating decreased the probability of having lower self-esteem in a study conducted over the span of 8 years 42 . The present findings are validated by the fact that intuitive eating is related to adaptive psychosocial factors and healthy lifestyle 52 .

Higher physical appearance comparison was directly and significantly associated with less intuitive eating. Previously, body appreciation and intuitive eating were both indicator of healthy eating behavior 53 . It is important to note that body appreciation can be considered the opposite of body appearance pressure, which could be generated through social physical appearance comparison 54 . Overall, self-acceptance, good body image, irrespective of contrasting one’s appearance with others’, and intuitive eating are promoters of positive psychological health 55 .

Practical implications

Given the lack of studies on intuitive eating in Lebanon, the current results are valuable in investigating an adaptive eating pattern. These findings allow practitioners to promote healthy eating behaviors and psychological health by educating patients and clients about intuitive eating. The current results not only could guide dieticians and nutritionists in their practice, but also psychologists and mental health professionals in developing management models for psychological distress and eating behaviors. Furthermore, it prompts action on the public health level to promote awareness regarding intuitive eating and its association with mental health. Finally, the mediating role of depression in the current associations prompts researchers to further assess the relationship in order to identify specific dimensions of depression involved.

Limitations

First, it is most important to mention the limitations of using a mediation model on cross-sectional data, as finding an accurate conclusion from data collected in one instance of time could be misrepresentative. Also, inferences about cause and effect cannot be concluded. Second, the questionnaire was distributed to participants through a snowball sampling technique, which might reduce the probability of the sample being representative. Third, the research about intuitive eating in the Middle East, the region where Lebanon is situated, is relatively limited and therefore no previous results exist to compare and contrast the findings. However, it makes the current results act as important motivators for future investigation about intuitive eating and psychological variables locally and internationally. Moreover, the process of the data collection, which is a self-report questionnaire, could be susceptible for response bias limiting the objectivity of the answers. Finally, it is important to note that the findings should be interpreted with caution, given the small effect sizes despite the significant results.

The present study clarifies the associations between intuitive eating, self-esteem, physical appearance and psychological distress and defines the mediating effect of psychological distress on the relationship between self-esteem/physical appearance comparison and intuitive eating. These results show how significantly intuitive eating, an adaptive eating pattern, and psychological variables are interrelated and possibly affect each other. It helps shed light on the factors involved with intuitive eating in the Lebanese population. In future studies, other mediators could be taken into consideration such as cognitive or personality ones.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the ethics committee but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Linardon, J., Tylka, T. L. & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Intuitive eating and its psychological correlates: a meta‐analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54 (7), 1073–1098 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Belon, K. E., Serier, K. N., VanderJagt, H. & Smith, J. E. What is healthy eating? Exploring profiles of intuitive eating and Nutritionally Healthy Eating in College Women. Am. J. Health Promotion . 36 (5), 823–833 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I. & Vohs, K. D. Does High Self-Esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. 4 (1), 1–44 (2003).

Google Scholar

Zeigler-Hill, V. Self-esteem: Psychology; (2013).

Sanlier, N., Biyikli, A. E. & Biyikli, E. T. Evaluating the relationship of eating behaviors of University students with body Mass Index and Self-Esteem. Ecol. Food Nutr. 54 (2), 175–185 (2015).

Fielder, C. R. Knowledge, motivations, and behaviors regarding eating a healthy diet and physical activity in relation to self-esteem in college students (Unpublished thesis). (Texas State University-San Marcos, San Marcos, Texas, 2008).

Veldhuis, J. J. T. I. E. M. P. Media Use, Body Image, and Disordered Eating Patterns. :1–14. (2020).

Schaefer, L. M. & Thompson, J. K. The development and validation of the physical appearance comparison scale-revised (PACS-R). Eat. Behaviors: Int. J. 15 (2), 209–217 (2014).

Vall-Roqué, H., Andrés, A. & Saldaña, C. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical appearance comparison scale-revised (PACS-R): psychometric properties in a mixed-gender community sample. Psicología Conductual . 30 (1), 269–289 (2022).

O’Brien, K. S. et al. Upward and downward physical appearance comparisons: development of scales and examination of predictive qualities. Body Image . 6 (3), 201–206 (2009).