How to Encourage Critical Thinking Skills While Reading: Effective Strategies

Encouraging critical thinking skills while reading is essential to children’s cognitive development. Critical thinking enables them to engage deeply with a topic or a book, fostering a better understanding of the material. It is a skill that does not develop overnight but can be nurtured through various strategies and experiences.

One effective way to cultivate critical thinking in children is by sharing quality books with them and participating in discussions that facilitate an exchange of ideas and opinions. Through these conversations, children can draw on their existing knowledge, problem-solving abilities, and experiences to expand their understanding of a subject.

Parents and teachers help kids think more deeply about things. They can do this by answering questions that help kids compare different ideas, look at things from different angles, guess what might happen, and develop new solutions.

Importance of Critical Thinking Skills in Reading

Critical thinking helps us understand what we read better. It helps us ask questions and think more deeply about the text. Critical thinking skills can help us analyze, evaluate, and understand what we read.

By incorporating critical thinking, readers can differentiate between facts and opinions, forming their views based on logical reasoning and evidence. This ability is particularly crucial in today’s information abundance, where readers are often exposed to biased or unreliable content. According to Critical Thinking Secrets , using critical thinking in reading allows learners to exercise their judgment in assessing the credibility of the information.

Furthermore, critical thinking promotes creativity and problem-solving skills. Practicing critical thinking allows learners to devise new and innovative ideas to address various challenges. This skill improves academic performance and prepares young minds for future professional endeavors.

Engaging with quality books and participating in thought-provoking discussions can nurture critical thinking abilities in children. Reading Rockets emphasizes the importance of exposing children to texts that challenge their thinking and encourage them to ask questions, fostering the development of critical thinking skills over time.

Teachers also play a significant role in promoting critical thinking in the classroom. Employing various instructional strategies, such as problem-based learning, asking open-ended questions, and providing opportunities for group discussions, can help students cultivate critical thinking habits.

Developing a Reading Environment That Fosters Critical Thinking

Creating a reading environment that promotes critical thinking enables students to engage with texts more deeply and develop essential analytical skills. The following sub-sections outline strategies for choosing thought-provoking materials and encouraging open discussions.

Choosing Thought-Provoking Materials

Selecting suitable reading materials is critical to stimulating critical thinking among students. Teachers should look for texts that:

- Are relevant and relatable to students’ lives and interests

- Present various perspectives and diverse characters

- Pose challenging questions and open-ended problems

By incorporating such texts into the classroom, students can be exposed to new ideas and viewpoints, promoting critical thinking and engagement with the material. For instance, in Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking , teachers are advised to choose compelling topics and maintain relevance to foster critical thinking

Encouraging Open Discussions

Fostering an environment where open discussions occur is essential to promoting critical thinking skills while reading. Teachers should:

- Create a culture of inquiry by posing open-ended questions and encouraging students to form opinions and debates

- Facilitate discussions by asking students to explain their thinking processes and share their interpretations of the text

- Respect all opinions and viewpoints, emphasizing that the goal is to learn from each other rather than reach a “correct” answer

Students who feel comfortable participating in discussions are more likely to develop critical thinking skills. The Reading Rockets emphasizes the importance of reading together and engaging in conversations to nurture critical thinking in children.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading is an essential skill for encouraging critical thinking skills while reading. This involves consciously engaging with the material and connecting with what you know or have read before. This section discusses key strategies that can help you become an active reader.

Annotating and Note-Taking

Annotating the text and taking notes as you read allows you to engage with the material on a deeper level. This process of actively engaging with the text helps you to analyze and retain information more effectively. As you read, it is important to make marginal notes or comments to highlight key points and draw connections between different sections of the material.

Asking Questions While Reading

One important aspect of critical reading is questioning the material. This means not taking everything you read at face value and considering the author’s interpretation and opinion . As you read, develop the habit of asking questions throughout the process, such as:

- What is the author’s main argument?

- What evidence supports this argument?

- How is the information presented in a logical manner?

- What are the possible opposing viewpoints?

By asking questions, you can better understand the author’s viewpoint and the evidence presented, which helps to develop your critical thinking skills.

Summarizing and Paraphrasing

Summarizing and paraphrasing are essential skills for critical reading. Summarizing the material allows you to condense key points and process the information more easily. Paraphrasing, or rephrasing the ideas in your own words, not only helps you better understand the material, but also ensures that you’re accurately interpreting the author’s ideas.

Both summarizing and paraphrasing can enhance your critical thinking skills by compelling you to analyze the text and identify the main ideas and supporting evidence. This way, you can make informed judgments about the content, making your reading more purposeful and engaging.

Developing critical thinking skills while reading literature involves a comprehensive understanding of various literary devices. This section highlights three primary aspects of literary analysis: Recognizing Themes and Patterns, Analyzing Characters and Their Motivations, and Evaluating the Author’s Intent and Perspective.

Recognizing Themes and Patterns

One way to foster critical thinking is through recognizing themes and patterns in the text. Encourage students to identify recurring themes, symbols, and motifs as they read. Additionally, examining the relationships between different elements in the story can help create connections and analyze the overall meaning.

For example, in a story about the struggles of growing up, students might notice patterns in the protagonist’s journey, such as recurring conflicts or milestones. By contemplating these patterns, learners can engage in deeper analysis and interpretation of the text.

Analyzing Characters and Their Motivations

Character analysis is an essential aspect of literary analysis, as understanding characters’ motivations can lead to a thorough comprehension of the narrative. Encourage students to analyze the motives behind each character’s actions, focusing on the factors that drive their decisions.

For instance, in a novel where two characters have differing goals, have students consider why these goals differ and how the characters’ motivations impact the story’s outcome. This exploration can lead to thought-provoking discussions about human behavior, facilitating the development of critical thinking skills.

Evaluating the Author’s Intent and Perspective

Critical thinking is essential to evaluating the author’s intent and perspective. This process involves deciphering the underlying message or purpose of the text and analyzing how the author’s experiences or beliefs may have influenced their writing.

One strategy for accomplishing this is to examine the historical or cultural context in which the work was written. By considering the author’s background, students can better understand the ideas or arguments presented in the text.

For example, if reading a novel set during a significant historical period, like the Civil Rights Movement, understanding the author’s experience can help students analyze narrative elements, enhancing their critical thinking abilities.

Methods to Encourage Critical Thinking Beyond Reading

While reading is essential to developing critical thinking skills, it can be further enhanced by incorporating certain activities in daily routines that promote critical thinking.

Debates and Group Discussions

Debates and group discussions are excellent methods for encouraging critical thinking. By participating in debates or discussions, learners exchange diverse ideas, challenge each other’s reasoning, and evaluate the strength of their arguments. These activities require participants to think and respond quickly, synthesize information, and analyze multiple perspectives.

Teachers and parents can facilitate debates and group discussions by selecting topics that are relevant and related to the subject matter. Promoting respectful dialogue and modeling effective listening skills are also important aspects of setting up successful debates or discussions.

Exploring Other Media Formats

In addition to reading, exploring other media formats like documentaries, podcasts, and videos can help stimulate critical thinking in learners. Different mediums present information in unique ways, providing learners with various perspectives and fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Using diverse media formats, individuals can compare and contrast information, question what they know, and further develop their analytical skills. It is essential that educators and parents encourage learners to explore these formats critically, assessing the credibility of the sources and ensuring accuracy in the information consumed.

Assessing Progress and Providing Feedback

Developing critical thinking skills while reading requires continuous assessment and feedback. Monitoring students’ progress in this area and providing constructive feedback can help ensure development and success.

Setting Measurable Goals

Establishing clear, measurable goals for critical thinking is vital for both students and educators. These goals should be specific, achievable, and time-bound. To effectively assess progress, consider using a variety of assessments, such as:

- Classroom discussions

- Reflective writing assignments

- Group projects

- Individual presentations

These different assessment methods can help determine if students are reaching their critical thinking goals and guide educators in adjusting their instruction as needed.

Providing Constructive Feedback

Constructive feedback is essential for students to improve their critical thinking skills. When providing feedback, consider the following guidelines:

- Be specific and focused on the critical thinking aspects of students’ work

- Link feedback directly to the established goals and criteria

- Encourage self-assessment and reflection

- Highlight strengths and areas for improvement

- Offer realistic suggestions for improvement

By implementing these strategies, educators can ensure that students receive the necessary support and guidance to develop their critical thinking skills while reading.

- Why The Reading Ranch?

- About the Owner / Director

- General Information

- Schedule • 2024

Reading & Writing Purposes

Introduction: critical thinking, reading, & writing, critical thinking.

The phrase “critical thinking” is often misunderstood. “Critical” in this case does not mean finding fault with an action or idea. Instead, it refers to the ability to understand an action or idea through reasoning. According to the website SkillsYouNeed [1]:

Critical thinking might be described as the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking.

In essence, critical thinking requires you to use your ability to reason. It is about being an active learner rather than a passive recipient of information.

Critical thinkers rigorously question ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value. They will always seek to determine whether the ideas, arguments, and findings represent the entire picture and are open to finding that they do not.

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct.

Someone with critical thinking skills can:

- Understand the links between ideas.

- Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas.

- Recognize, build, and appraise arguments.

- Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

- Approach problems in a consistent and systematic way.

- Reflect on the justification of their own assumptions, beliefs and values.

Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/critical-thinking.html

Critical thinking—the ability to develop your own insights and meaning—is a basic college learning goal. Critical reading and writing strategies foster critical thinking, and critical thinking underlies critical reading and writing.

Critical Reading

Critical reading builds on the basic reading skills expected for college.

College Readers’ Characteristics

- College readers are willing to spend time reflecting on the ideas presented in their reading assignments. They know the time is well-spent to enhance their understanding.

- College readers are able to raise questions while reading. They evaluate and solve problems rather than merely compile a set of facts to be memorized.

- College readers can think logically. They are fact-oriented and can review the facts dispassionately. They base their judgments on ideas and evidence.

- College readers can recognize error in thought and persuasion as well as recognize good arguments.

- College readers are skeptical. They understand that not everything in print is correct. They are diligent in seeking out the truth.

Critical Readers’ Characteristics

- Critical readers are open-minded. They seek alternative views and are open to new ideas that may not necessarily agree with their previous thoughts on a topic. They are willing to reassess their views when new or discordant evidence is introduced and evaluated.

- Critical readers are in touch with their own personal thoughts and ideas about a topic. Excited about learning, they are eager to express their thoughts and opinions.

- Critical readers are able to identify arguments and issues. They are able to ask penetrating and thought-provoking questions to evaluate ideas.

- Critical readers are creative. They see connections between topics and use knowledge from other disciplines to enhance their reading and learning experiences.

- Critical readers develop their own ideas on issues, based on careful analysis and response to others’ ideas.

The video below, although geared toward students studying for the SAT exam (Scholastic Aptitude Test used for many colleges’ admissions), offers a good, quick overview of the concept and practice of critical reading.

Critical Reading & Writing

College reading and writing assignments often ask you to react to, apply, analyze, and synthesize information. In other words, your own informed and reasoned ideas about a subject take on more importance than someone else’s ideas, since the purpose of college reading and writing is to think critically about information.

Critical thinking involves questioning. You ask and answer questions to pursue the “careful and exact evaluation and judgment” that the word “critical” invokes (definition from The American Heritage Dictionary ). The questions simply change depending on your critical purpose. Different critical purposes are detailed in the next pages of this text.

However, here’s a brief preview of the different types of questions you’ll ask and answer in relation to different critical reading and writing purposes.

When you react to a text you ask:

- “What do I think?” and

- “Why do I think this way?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “reaction” questions about the topic assimilation of immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: I think that assimilation has both positive and negative effects because, while it makes life easier within the dominant culture, it also implies that the original culture is of lesser value.

When you apply text information you ask:

- “How does this information relate to the real world?”

e.g., If I asked and answered this “application” question about the topic assimilation , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: During the past ten years, a group of recent emigrants has assimilated into the local culture; the process of their assimilation followed certain specific stages.

When you analyze text information you ask:

- “What is the main idea?”

- “What do I want to ‘test’ in the text to see if the main idea is justified?” (supporting ideas, type of information, language), and

- “What pieces of the text relate to my ‘test?'”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “analysis” questions about the topic immigrants to the United States , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: Although Lee (2009) states that “segmented assimilation theory asserts that immigrant groups may assimilate into one of many social sectors available in American society, instead of restricting all immigrant groups to adapting into one uniform host society,” other theorists have shown this not to be the case with recent immigrants in certain geographic areas.

When you synthesize information from many texts you ask:

- “What information is similar and different in these texts?,” and

- “What pieces of information fit together to create or support a main idea?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “synthesis” questions about the topic immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop by using examples and information from many text articles as evidence to support my idea: Immigrants who came to the United States during the immigration waves in the early to mid 20th century traditionally learned English as the first step toward assimilation, a process that was supported by educators. Now, both immigrant groups and educators are more focused on cultural pluralism than assimilation, as can be seen in educators’ support of bilingual education. However, although bilingual education heightens the child’s reasoning and ability to learn, it may ultimately hinder the child’s sense of security within the dominant culture if that culture does not value cultural pluralism as a whole.

Critical reading involves asking and answering these types of questions in order to find out how the information “works” as opposed to just accepting and presenting the information that you read in a text. Critical writing involves recording your insights into these questions and offering your own interpretation of a concept or issue, based on the meaning you create from those insights.

- Crtical Thinking, Reading, & Writing. Authored by : Susan Oaks, includes material adapted from TheSkillsYouNeed and Reading 100; attributions below. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : TheSkillsYouNeed. Located at : https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Quoted from website: The use of material found at skillsyouneed.com is free provided that copyright is acknowledged and a reference or link is included to the page/s where the information was found. Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/

- The Reading Process. Authored by : Scottsdale Community College Reading Faculty. Provided by : Maricopa Community College. Located at : https://learn.maricopa.edu/courses/904536/files/32966438?module_item_id=7198326 . Project : Reading 100. License : CC BY: Attribution

- image of person thinking with light bulbs saying -idea- around her head. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/light-bulb-idea-think-education-3704027/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video What is Critical Reading? SAT Critical Reading Bootcamp #4. Provided by : Reason Prep. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hc3hmwnymw . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- image of man smiling and holding a lightbulb. Authored by : africaniscool. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/man-african-laughing-idea-319282/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

In Between the Lines: A Guide to Reading Critically

I often find that Princeton professors assume that we all know how to “read critically.” It’s a phrase often included in essay prompts, and a skill necessary to academic writing. Maybe we’re familiar with its definition: close examination of a text’s logic, arguments, style, and other content in order to better understand the author’s intent. Reading non-critically would be identifying a metaphor in a passage, whereas the critical reader would question why the author used that specific metaphor in the first place. Now that the terminology is clarified, what does critical reading look like in practice? I’ve put together a short guide on how I approach my readings to help demystify the process.

- Put on your scholar hat. Critical reading starts before the first page. You should assume that the reading in front of you was the product of several choices made by the author, and that each of these choices is subject to analysis. This is a critical mindset, but importantly, not a negative one. Not taking a reading at face value doesn’t mean approaching the reading hoping to find everything that’s wrong, but rather what could be improved .

- Revisit Writing Sem : Motive and thesis are incredibly helpful guides to understanding tough academic texts. Examining why the author is writing this text (motive), provides a context for the work that follows. The thesis should be in the back of your mind at all times to understand how the evidence presented proves it, but simultaneously thinking about the motive allows you to think about what opponents to the author might say, and then question how the evidence would stand up to these potential rebuttals.

- Get physical . Take notes! Critical reading involves making observations and insights—track them! My process involves underlining, especially as I see recurring terms, images, or themes. As I read, I also like to turn back and forth constantly between pages to link up arguments. I was reading a longer legal text for a class and found that flipping back and forth helped me clarify the ideas presented in the beginning of the text so I could track their development in later pages.

- Play Professor. While I’m reading, I like to imagine potential discussion or essay topics I would come up with if I were a professor. These usually involves examining the themes of the text, placing this text in comparison or contrast with another one we have read in the class, and paying close attention to how the evidence attempts to prove the thesis.

- Form an (informed) opinion. After much work, underlining, and debating, it’s safe to make your own judgments about the author’s work. In forming this opinion, I like to mentally prepare to have this opinion debated, which helps me complicate my own conclusions—a great start to a potential essay!

Critical reading is an important prerequisite for the academic writing that Princeton professors expect. The best papers don’t start with the first word you type, but rather how you approach the texts composing your essay subject. Hopefully, this guide to reading critically will help you write critically as well!

–Elise Freeman, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 – Critical Reading

“Citizens of modern societies must be good readers to be successful. Reading skills do not guarantee success for anyone, but success is much harder to come by without being a skilled reader. The advent of the computer and the Internet does nothing to change this fact about reading. If anything, electronic communication only increases the need for effective reading skills and strategies as we try to cope with the large quantities of information made available to us.” –William Grabe

The importance of reading as a literacy skill is without a doubt. It is essential for daily life navigation and academic success. Reading for daily life navigation is relatively easier, compared to academic reading. Think about the kinds of reading you did in elementary and high school (e.g., story books, picture books, textbook chapters, literary works, online information, lecture notes, etc.).

Now think about what you were expected to do with your reading at school (e.g., memorize, summarize, discuss, pass a test, apply information, or write essays or papers).

Research shows that what you expect to do with a text affects how you read it.

–Bartholomae & Petrosky (1996)

So, reading is not always the same; you read school texts differently than the texts you choose outside of school tasks. Furthermore, there are many external and internal factors that influence how you interpret and use what you read. Much depends on your background (e.g., cultural participation in communities, identity, historical knowledge), and the context in which you are reading. Classrooms and teachers certainly have an influence. The teaching methods used by your instructor, the texts your instructor chooses, and expectations of student performance on assignments all affect how you read and what you do to accomplish an assignment.

Different levels of education also emphasize different types of reading. For example, in primary or secondary education, you learn what is known, so you focus on correctness, memorization of facts, and application of facts. In higher education, although you might still be required to understand and memorize information, you expand what is known by examining ideas and creating new knowledge. In those processes at different levels, reading has been used for different purposes.

Multilingual reading and writing expert William Grabe has identified six different purposes:

- Reading to search for information (scanning and skimming)

- Reading for quick understanding (skimming)

- Reading to learn

- Reading to integrate information

- Reading to evaluate, critique, and use information

- Reading for general comprehension (in many cases, reading for interest or reading to entertain)

In college, reading to evaluate, critique, and use information is the most practiced and tested skill. But what does it mean? Reading to evaluate, critique, and use information is related to critical reading.

Definition of Critical Reading

Critical reading is a more ACTIVE way of reading. It is a deeper and more complex engagement with a text. Critical reading is a process of analyzing, interpreting and, sometimes, evaluating. When we read critically, we use our critical thinking skills to QUESTION both the text and our own reading of it. Different disciplines may have distinctive modes of critical reading (scientific, philosophical, literary, etc).

[Source: Duncan , n.d., Critical Reading ]

Critical reading does not have to be all negative. The aim of critical reading is not to find fault but to assess the strength of the evidence and the argument. It is just as useful to conclude that a study, or an article, presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument, as it is to identify the studies or articles that are weak.

[Source: What is critical reading? ]

There’s No Reason to Eat Animals by Lindsay Rajt

If we care about the environment and believe that kindness is a virtue-as we all say that we do–a vegan diet is the only sensible option. The question becomes: Why eat animals at all?

Animals are made of flesh, bone, and blood, just as you and I are. They form friendships, feel pain and joy, grieve for lost loved ones and are afraid to die. One cannot profess to care about animals while tearing them away from their friends and families and cutting their throats–or paying someone else to do it–simply to satisfy a fleeting taste for flesh.

[adapted from Pattison, 2015, Critical Reading: English for Academic Purposes for instructional purposes ]

What is your position on the issue?

Do you think that the language used helps the audience? How?

How does the language use affect your evaluation of the issue?

Obesity: A Public Health Failure? By Tavis Glassman PhD, MPH, MCHES, Jennifer Glassman M.A., CCC-SLP, and Aaron J. Diehr, M.A.

Obesity rates continue to increase, bringing into question the efficacy of prevention and treatment efforts. While intuitively appealing, the law on weight gain focusing on calories is too simplistic because calories represent only one factor on issues of weight management. From a historical perspective, the recommendation to eat a low fat, high carbohydrate diet may have been the wrong message to promote, thereby making the obesity situation worse. Suggestions to solve the issues of obesity include taxing, restricting advertising, and reducing the use of sugar. Communities must employ these and other strategies to decrease sugar use and reduce obesity rates.

How would you describe the authors’ educational background?

How does the authors’ background affect your evaluation of the argument?

Students Want More Mobile Devices in Classroom by Ellis Booker

Released last week, the Student Mobile Device Survey reveals that students almost unanimously believe mobile technology will change education and make learning more fun. The survey, which collected the responses of 2,350 US students, was conducted for learning company Pearson by Harris Interactive.

According to the survey, 92% of elementary, middle and high school students believe mobile devices will change the way students learn in the future and make learning more fun (90%). A majority (69%) would like to use mobile devices more in the classroom.

The survey results also contained some surprises. For example, college students in math and science are much more likely to use technology for learning, and researchers expected to see this same pattern in the lower grades.

Are you convinced by the survey results? Why?

Color Scheme Associations in Context

The colors you surround yourself with at work are also important as they make a difference in how you are perceived by members of the public. Traditional workplaces still use dark colors such as navy blue, forest green, and chocolate brown to give clients a sense of seriousness and professionalism.

Think about it: which accountant would you choose to prepare your tax return: the one whose office has navy blue drapes and lamps and a maritime scene on the wall or the one whose office is painted in hot pink with a cartoon character on the wall? An online survey of lawyers carried out by Legal Scene magazine showed that of 287 respondents, 38 percent chose a navy blue color scheme for their office; 32 percent chose brown; 19 percent chose forest green; 7 percent chose burgundy; and only 4 percent chose red, pink or orange (Perkins, 2013).

What kind of bias might be implicated in this survey?

What is your personal experience?

These practices do not ask you to memorize or summarize the information you read, but instead, they ask you to provide your opinions and judgment. To answer those questions, you need to engage in critical reading, a form of active reading.

Active reading, which predominates college-level reading, means reading with the purpose of getting a deeper understanding of the texts you are reading and being engaged in the actions of analyzing, questioning, and evaluating the texts. In other words, instead of accepting the information given to you, you challenge its value by examining the source of the information and the formation of an argument.

The difference in how you read falls into two broad categories:

(Source: Reading Critically ]

Reading critically and actively is essential for college students. But what does critical reading look like in actual practice? Here are the steps that you can follow to do the critical reading.

Step 1: Understand the purpose of your reading and be selective

As college students, you are very busy with your daily coursework. A freshman usually takes four to five courses or even six courses per semester. This means you have tons of reading to do every week. Getting to know the purpose of the reading assignments can save you time as your reading is more targeted. Remember you do not have to read a whole chapter or book. What you can do is through scanning to determine the sections that are useful for you and then read the parts carefully.

Step 2: Evaluate the reading text

While reading a text, you need to question/analyze/evaluate the text by considering the following:

- Assess whether a source is reliable (Read around the text for the title, author, publisher, publication date, good/bad examples, tones, etc.)

- Distinguish between facts and opinions (Scan for any evidence)

- Recognize multiple opinions in a text

- Infer meaning when it is not directly stated

- Agree or disagree with what you read

- Consider the relevance of the text to your task

- Consider what is missing from a text

It may well be necessary to read passages several times to gain a full understanding of texts and be able to evaluate the source. In this process, you can underline, highlight, or circle important parts and points, take notes, or add comments in the margins.

Critical reading often involves re-reading a text multiple times, putting our focus on different aspects of the text. The first time we read a text, we may be focused on getting an overall sense of the information the author is presenting – in other words, simply understanding what they are trying to say. On subsequent readings, however, we can focus on how the author presents that information, the kinds of evidence they provide to support their arguments (and how convincing we find that evidence), the connection between their evidence and their conclusions, etc.

[Source: Lane, 2021, Critical Thinking for Critical Writing ]

Step 3: Document your reading and form your own argument

After you finish reading a text, sort out your notes and keep track of the sources you have read on the topic you are exploring. After you read several sources, you might be able to form your own argument(s) and use the sources as evidence for your argument(s).

In college, critical reading usually leads to critical writing.

Critical writing comes from critical reading. Whenever you have to write a paper, you have to reflect on various written texts, think and interpret research that has previously been carried out on your subject. With the aim of writing your independent analysis of the subject, you have to critically read sources and use them suitably to formulate your argument. The interpretations and conclusions you derive from the literature you read are the stepping stones towards devising your own approach.

[Source: Does Critical Reading Influence Academic Writing? ]

In a word, through critical reading, you form your own argument(s), and the evidence used to support your argument(s) is usually from the texts that you read critically. The Source Essay Writing Service explains how critical reading influences academic writing.

How does critical reading influence your writing skills?

Once you start reading texts critically, you develop an understanding of how to write research papers. Here are some practical tips that will help you in academic writing:

- Examine introductions and conclusions of the texts while critical reading so when you write an independent content, you would be able to decide how to focus your critical work.

- When you highlight or take notes from a text, make sure you focus on the argument. The way the author explains the analytical progress, the concepts used, and arriving at conclusions will help you to write your own facts and examples in an interesting way.

- By closely reading the texts, you will be able to look for the patterns that give meaning, purpose, and consistency to the text. The way the arguments are presented in paragraphs will aid you in structuring information in your writing.

- When you critically read a text, you are able to learn how an argument is placed in the text. Try to understand how you can use this placement strategy in academic writing. Paying attention to the context is an important aspect that you learn from critical reading.

- While reading a text, you will notice that the author has given the due credit to the sources used or the references that were consulted. This will help you in understanding how you can cite sources and quotes in your content.

- Critical reading skills enhance your way of thinking and writing skills. The more you read, the better is your knowledge and vocabulary. It is important to use the precise words to express your meaning. You can learn new words and improve your writing by reading as many texts as you can.

Activity 1: Discuss the following questions with your group

- A website from the United Nations Educational, Scientific ad Cultural Organization (UNESCO) gives some statistics about the level of education reached by young women in Indonesia. Is this a reliable source?

- You find an interesting article about addiction to online gambling. The article has some interesting statistics, but it was published ten years ago. Is it worth using?

- You find a book about World War II that presents a different opinion from your other sources. What would you like to know about the author before you decide whether or not to take him seriously?

- An article tells you that research into space exploration is a waste of money. Do you think this article is presenting facts or opinions? How can you tell? What might you look for in the article?

- You find some research that states that people who own dogs generally live longer lives than those who do not. The author has some convincing arguments, but you are not sure whether or not she has enough evidence. How mush is enough?

- A newspaper article tells you about human rights abuses in a certain country. The writer of this article has never visited the country in question; his claims are based on interviews with other people. How would you evaluate his information?

- You find two websites about the use of seaweed as a source of energy. One is full of long words and complicated sentences; the other uses simple, clear language. Is the first one a more reliable source?

- You have read nine different articles that tell you that there is no connection between wealth and happiness. The tenth article gives the opposite opinion: rich people are happier than those who are poor. What questions would you ask yourself about this article before you decide whether or not to consider it?

Activity 2: Reading for analyzing styles

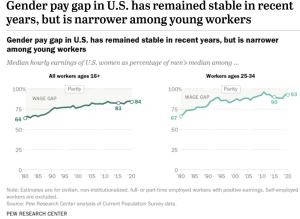

Please read the news and discuss the importance of the graphs in supporting the arguments of the text.

Gender Pay Gap in U.S. Held Steady in 2020

By amanda barroso and anna brown.

The gender gap in pay has remained relatively stable in the United States over the past 15 years or so. In 2020, women earned 84% of what men earned, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. Based on this estimate, it would take an extra 42 days of work for women to earn what men did in 2020.

As has been the case in recent decades, the 2020 wage gap was smaller for workers ages 25 to 34 than for all workers 16 and older. Women ages 25 to 34 earned 93 cents for every dollar a man in the same age group earned on average. In 1980, women ages 25 to 34 earned 33 cents less than their male counterparts, compared with 7 cents in 2020. The estimated 16-cent gender pay gap among all workers in 2020 was down from 36 cents in 1980.

The U.S. Census Bureau has also analyzed the gender pay gap, though its analysis looks only at full-time workers (as opposed to full- and part-time workers). In 2019, full-time, year-round working women earned 82% of what their male counterparts earned, according to the Census Bureau’s most recent analysis.

Why does a gender pay gap still persist?

Much of this gap has been explained by measurable factors such as educational attainment, occupational segregation and work experience. The narrowing of the gap is attributable in large part to gains women have made in each of these dimensions.

Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be over-represented in lower-paying occupations relative to their share of the workforce. This may contribute to gender differences in pay.

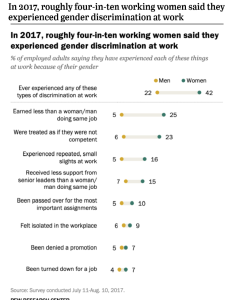

Other factors that are difficult to measure, including gender discrimination, may also contribute to the ongoing wage discrepancy. In a 2017 Pew Research Center survey , about four-in-ten working women (42%) said they had experienced gender discrimination at work, compared with about two-in-ten men (22%). One of the most commonly reported forms of discrimination focused on earnings inequality. One-in-four employed women said they had earned less than a man who was doing the same job; just 5% of men said they had earned less than a woman doing the same job.

Motherhood can also lead to interruptions in women’s career paths and have an impact on long-term earnings. Our 2016 survey of workers who had taken parental, family or medical leave in the two years prior to the survey found that mothers typically take more time off than fathers after birth or adoption. The median length of leave among mothers after the birth or adoption of their child was 11 weeks, compared with one week for fathers. About half (47%) of mothers who took time off from work in the two years after birth or adoption took off 12 weeks or more.

Mothers were also nearly twice as likely as fathers to say taking time off had a negative impact on their job or career. Among those who took leave from work in the two years following the birth or adoption of their child, 25% of women said this had a negative impact at work, compared with 13% of men.

[Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/25/gender-pay-gap-facts/ ]

Activity 3: Reading for arguments

What’s the main argument of the poem?

Fire and Ice

By robert frost, some say the world will end in fire, some say in ice. from what i’ve tasted of desire i hold with those who favor fire. but if it had to perish twice, i think i know enough of hate to say that for destruction ice is also great and would suffice..

References:

Barroso, A., & Brown, A. (2021, May 25). Gender pay gap in U.S. held steady in 2020. Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/25/gender-pay-gap-facts/

Bartholomae, D., Petrosky, T., & Waite, S. (2002). Ways of reading: An anthology for writers (p. 720). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Duncan, J. (n.d.). The Writing Centre, University of Toronto Scarborough. Modified by Michael O’Connor. https://www.stetson.edu/other/writing-program/media/CRITICAL%20READING.pdf

Grabe, W. (2008). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Lane, J. (2021, July 9). Critical thinking for critical writing. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/about/branches-depts/slc/writing/argumentation/critical-thinking-writing

Pattison, T. (2015). Critical Reading: English for academic purposes for instructional purposes. Pearson.

Sourceessay. (n.d.). What is critical reading. https://sourceessay.com/does-critical-reading-influence-academic-writing/

University of Leicester. (n.d.). What is critical reading? Bangor University. https://www.bangor.ac.uk/studyskills/study-guides/critical-reading.php.en

Critical Reading, Writing, and Thinking Copyright © 2022 by Zhenjie Weng, Josh Burlile, Karen Macbeth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Academic Skills: Critical Reading

- Academic Skills Home

- Accounting and Finance

- Beyond the Classroom

- Capstone Formatting

- Classroom Skills

- Communication

- Course-Level Statistics

- Course Resources

- Critical Reading

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Doctoral Capstone and Residency

- Grit and Resilience

- HUMN 8304 Resources

- Learning Strategies

- Microsoft Office

- Microsoft PowerPoint

- Mindset and Wellness

- Microsoft Word

- Peer Mentors

- School-Life Balance

- Self-Care and Wellness

- Self-Paced Modules

- SMART Goals

- SPSS and NVivo

- Statistics Resources

- Statistics Skills in Microsoft Excel

- Peer Tutoring

- Strengthen Your Statistics Skills

- Success Strategies

- Time Management

- Previous Page: Course Resources

- Next Page: Diversity and Inclusion

Reading Self-Paced Modules

Reading Textbooks

Reading Articles

Reading Skills Part 1: Set Yourself Up for Success

"While - like many of us - I enjoy reading what I want to read, I still struggle to get through a dense research article or textbook chapter. I have noticed, however, that if I take steps to prepare, I am much more likely to persist through a challenging reading. "

Reading Skills Part 2: Alternatives to Highlighting

"It starts with the best of intentions: trusty highlighter in hand or (for the tech-savvy crowd) highlighting tool hovering on-screen, you work your way through an assigned reading, marking only the most important information—or so you think."

Reading Skills Part 3: Read to Remember

"It’s happened to the best of us: on Monday evening, you congratulate yourself on making it though an especially challenging reading. What a productive start to the week!"

Reading a Research Article Assigned as Coursework

"Reading skills are vital to your success at Walden. The kind of reading you do during your degree program will vary, but most of it will involve reading journal articles based on primary research."

Critical Reading for Evaluation

"Whereas analysis involves noticing, evaluation requires the reader to make a judgment about the text’s strengths and weaknesses. Many students are not confident in their ability to assess what they are reading."

Critical Reading for Analysis and Comparison

"Critical reading generally refers to reading in a scholarly context, with an eye toward identifying a text or author’s viewpoints, arguments, evidence, potential biases, and conclusions."

Pre-Reading Strategies

Triple entry notebook, critical thinking.

Use this checklist to practice critical thinking while reading an article, watching an advertisement, or making an important purchase or voting decision.

Critical Reading Checklist (Word) Critical Reading Checklist (PDF) Critical Thinking Bookmark (PDF)

Walden's Online Bookstore

Go to Walden's Online Bookstore

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Subject Guides

Being critical: a practical guide

Critical reading.

- Being critical

- Critical thinking

- Evaluating information

- Reading academic articles

- Critical writing

The purposes and practices of reading

The way we read depends on what we’re reading and why we’re reading it. The way we read a novel is different to the way we read a menu . Perhaps we are reading to understand a subject, to increase our knowledge, to analyse data, to retrieve information, or maybe even to have fun! The purpose of our reading will determine the approach we take.

Reading for information

Suppose we were trying to find some directions or opening hours... We would need to scan the text for key words or phrases that answer our question, and then we would move on.

It's a bit like doing a Google search and then just reading the results page rather than accessing the website.

Reading for understanding

When we're reading for pleasure or doing background reading on a topic, we'll generally read the text once, from start to finish . We might apply skimming techniques to look through the text quickly and get the general gist. Our engagement with the text might therefore be quite passive: we're looking for a general understanding of what's being written, perhaps only taking in the bits that seem important.

Reading for analysis

When we're doing reading for an essay, dissertation, or thesis, we're going to need to actively read the text multiple times . All the while we'll engage our prior knowledge and actively apply it to our reading, asking questions of what's been written.

This is critical reading !

Reading strategies

When you’re reading you don’t have to read everything with the same amount of care and attention. Sometimes you need to be able to read a text very quickly.

There are three different techniques for reading:

- Scanning — looking over material quite quickly in order to pick out specific information;

- Skimming — reading something fairly quickly to get the general idea;

- Close reading — reading something in detail.

You'll need to use a combination of these methods when you are reading an academic text: generally, you would scan to determine the scope and relevance of the piece, skim to pick out the key facts and the parts to explore further, then read more closely to understand in more detail and think critically about what is being written.

These strategies are part of your filtering strategy before deciding what to read in more depth. They will save you time in the long run as they will help you focus your time on the most relevant texts!

You might scan when you are...

- ...browsing a database for texts on a specific topic;

- ...looking for a specific word or phrase in a text;

- ...determining the relevance of an article;

- ...looking back over material to check something;

- ...first looking at an article to get an idea of its shape.

Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for. You identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest. You're scanning for pieces of information that will give you a general impression of it rather than trying to understand its detailed arguments.

You're mostly on the look-out for any relevant words or phrases that will help you answer whatever task you're working on. For instance, can you spot the word "orange" in the following paragraph?

Being able to spot a word by sight is a useful skill, but it's not always straightforward. Fortunately there are things to help you. A book might have an index, which might at least get you to the right page. An electronic text will let you search for a specific word or phrase. But context will also help. It might be that the word you're looking for is surrounded by similar words, or a range of words associated with that one. I might be looking for something about colour, and see reference to pigment, light, or spectra, or specific colours being called out, like red or green. I might be looking for something about fruit and come across a sentence talking about apples, grapes and plums. Try to keep this broader context in mind as you scan the page. That way, you're never really just going to be looking for a single word or orange on its own. There will normally be other clues to follow to help guide your eye.

Approaches to scanning articles:

- Make a note of any questions you might want to answer – this will help you focus;

- Pick out any relevant information from the title and abstract – Does it look like it relates to what you're wanting? If so, carry on...

- Flick or scroll through the article to get an understanding of its structure (the headings in the article will help you with this) – Where are certain topics covered?

- Scan the text for any facts , illustrations , figures , or discussion points that may be relevant – Which parts do you need to read more carefully? Which can be read quickly?

- Look out for specific key words . You can search an electronic text for key words and phrases using Ctrl+F / Cmd+F. If your text is a book, there might even be an index to consult. In either case, clumps of results could indicate an area where that topic is being discussed at length.

Once you've scanned a text you might feel able to reject it as irrelevant, or you may need to skim-read it to get more information.

You might skim when you are...

- ...jumping to specific parts such as the introduction or conclusion;

- ...going over the whole text fairly quickly without reading every word;

Skim-reading, or speed-reading, is about reading superficially to get a gist rather than a deep understanding. You're looking to get a feel for the content and the way the topic is being discussed.

Skim-reading is easier to do if the text is in a language that's very familiar to you, because you will have more of an awareness of the conventions being employed and the parts of speech and writing that you can gloss over. Not only will there be whole sections of a text that you can pretty-much ignore, but also whole sections of paragraphs. For instance, the important sentence in this paragraph is the one right here where I announce that the important part of the paragraph might just be one sentence somewhere in the middle. The rest of the paragraph could just be a framework to hang around this point in order to stop the article from just being a list.

However, it may more often be that the important point for your purposes comes at the start of the paragraph. Very often a paragraph will declare what it's going to be about early on, and will then start to go into more detail. Maybe you'll want to do some closer reading of that detail, or maybe you won't. If the first paragraph makes it clear that this paragraph isn't going to be of much use to you, then you can probably just stop reading it. Or maybe the paragraph meanders and heads down a different route at some point in the middle. But if that's the case then it will probably end up summarising that second point towards the end of the paragraph. You might therefore want to skim-read the last sentence of a paragraph too, just in case it offers up any pithy conclusions, or indicates anything else that might've been covered in the paragraph!

For example, this paragraph is just about the 1980s TV gameshow "Treasure Hunt", which is something completely irrelevant to the topic of how to read an article. "Treasure Hunt" saw two members of the public (aided by TV newsreader Kenneth Kendall) using a library of books and tourist brochures to solve a series of five clues (provided, for the most part, by TV weather presenter Wincey Willis). These clues would generally be hidden at various tourist attractions within a specific county of the British Isles. The contestants would be in radio contact with a 'skyrunner' (Anneka Rice) who had a map and the use of a helicopter (piloted by Keith Thompson). Solving a clue would give the contestants the information they needed to direct the skyrunner (and her crew of camera operator Graham Berry and video engineer Frank Meyburgh) to the location of the next clue, and, ultimately, to the 'treasure' (a token object such as a little silver brooch). All of this was done against the clock, the contestants having only 45' to solve the clues and find the treasure. This, necessarily, required the contestants to be able to find relevant information quickly: they would have to select the right book from the shelves, and then navigate that text to find the information they needed. This, inevitably, involved a considerable amount of skim-reading. So maybe this paragraph was slightly relevant after all? No, probably not...

Skim-reading, then, is all about picking out the bits of a text that look like they need to be read, and ignoring other bits. It's about understanding the structure of a sentence or paragraph, and knowing where the important words like the verbs and nouns might be. You'll need to take in and consider the meaning of the text without reading every single word...

Approaches to skim-reading articles:

- Pick out the most relevant information from the title and abstract – What type of article is it? What are the concepts? What are the findings?;

- Scan through the article and note the headings to get an understanding of structure;

- Look more closely at the illustrations or figures ;

- Read the conclusion ;

- Read the first and last sentences in a paragraph to see whether the rest is worth reading.

After skimming, you may still decide to reject the text, or you may identify sections to read in more detail.

Close reading

You might read closely when you are...

- ...doing background reading;

- ...trying to get into a new or difficult topic;

- ...examining the discussions or data presented;

- ...following the details or the argument.

Again, close reading isn't necessarily about reading every single word of the text, but it is about reading deeply within specific sections of it to find the meaning of what the author is trying to convey. There will be parts that you will need to read more than once, as you'll need to consider the text in great detail in order to properly take in and assess what has been written.

Approaches to the close reading of articles:

- Focus on particular passages or a section of the text as a whole and read all of its content – your aim is to identify all the features of the text;

- Make notes and annotate the text as you read – note significant information and questions raised by the text;

- Re-read sections to improve understanding;

- Look up any concepts or terms that you don’t understand.

Questioning

Questioning goes hand-in-hand with reading for analysis. Before you begin to read, you should have a question or set of questions that will guide you. This will give purpose to your reading, and focus you; it will change your reading from a passive pursuit to an active one, and make it easier for you to retain the information you find. Think about what you want to achieve and keep the purpose in mind as you're reading.

Ask yourself...

- Why am I reading this? — What is my task or assignment question, and how is this source helping to answer it?

- What do I already know about the subject? — How can I relate what I'm reading to my own experiences?

You'll need to ask questions of the text too:

- Examine the evidence or arguments presented;

- Check out any influences on the evidence or arguments;

- Check the limitations of study design or focus;

- Examine the interpretations made.

Are you prepared to accept the authors’ arguments, opinions, or conclusions?

Critical reading: why, what, and how

Blocks to critical reading.

Certain habits or approaches we have to life can hold us back from really thinking objectively about issues. We may not realise it, but often we're our own worst enemies when it comes to being critical...

Select a student to reveal the statement they've made.

I have been asked to work on an area that is completely new. Where do I start in terms of finding relevant texts?

Ask for guidance:

ask your tutor or module leader

use your module reading lists

make use of the Skills Guides (oh... you are! Excellent!)

ask your Faculty Librarians

Take a look at our contextagon and begin to consider sources of information .

I don’t understand what I'm reading – It's too difficult!

If the text is difficult, don’t panic!

If it is a journal article, scan the text first – look at the contents, abstract, introduction, conclusion and subheadings to try to make sense of the argument.

Then read through the whole text to try to understand the key messages, rather than every single word or section. On a second reading, you will find it easier to understand more.

If you are struggling to get to grips with theories or concepts, you might find it useful to look at a summary as a way in -- for example, in an online subject encyclopaedia .

If you are struggling with difficult vocabulary, it may be useful to keep a glossary of key vocabulary, particularly if it is specialist or technical.

Remember, the more you read, the more you will understand it and be able to use it yourself.

Take a look at our Academic sources Skills Guide .

Help! There is too much to read and too little time!

University study involves a large amount of reading. However, some texts on your reading lists are core texts and some are more optional.

You will generally need to read the core text, but on the optional list there may be a range of texts which deal with the same topic from different perspectives. You will need to decide which are the most relevant to your interests and assignments.

Keep in mind the questions you want the text to answer and look for what is relevant to those questions. Prioritise and read only as much as you need to get the information you need (if it's a book, use the index; if it's an article, concentrate on the relevant parts).

Improve your note-taking skills by keeping them brief and selective.

If in doubt, ask your tutor or Faculty Librarians for guidance.

Take a look at the Organise and Analyse section of the Skills Guides.

I am struggling to remember what I have read.

To remember what you have read, you need to interact with the material. If you have questioned and evaluated the material you are reading, you will find it easier to remember.

Improve your active note-taking skills using a method like Cornell or Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review (SQR3).

Annotate your pdfs and use a note-taking app .

Make time to consolidate your reading periodically. You could do this by summarising key points from memory or connecting ideas using mindmapping.

Consider using a reference management program to keep on top of reading, and mind-mapping software like Mindgenius to connect ideas.

Where did I read that thing?

Make sure you have a good system for taking notes and try to keep your notes organised/in one place, whether that is using an app or taking notes by hand. There is no right way to do this - find a system that works for you.

Logically label and file your notes, linking new information with what you already know and cross-reference with any handouts.

Make sure you make a note of information for referencing sources.

Where possible, save resources you have used to Google Drive or your University filestore , and organise these (e.g. by module, assessment, topic etc.).

Many of the above tips can be achieved with reference management software .

I have strong opinions about the argument being presented in the reading – why can’t I just put this side forward?

Truth is a complicated business. Core texts or texts by highly respected authors are an author’s interpretation, and that interpretation is not above question. Any single text only provides a perspective. Even a scientific observation may be modified by further evidence. Critical writing means making sure your argument is balanced, considering and critiquing a range of perspectives.

Read texts objectively and assess their value in terms of what they can bring to your work, rather than whether you agree with them or not.

If you agree or disagree strongly with an author, you still need to analyse their argument and justify why it is sound or unsound, reliable or unreliable, and valid or lacking validity.

Ignoring opposing views can be a mistake. Your reader may think you are unaware of the different views or are not willing to think the ideas through and challenge them.

Be careful not to be blinded by your own views about a topic or an author. Engaging actively with a text which you initially don’t agree with can mean you have to rethink or adjust your own position, making your final argument stronger.

Take a look at the other parts of the Being critical Skills Guides .

That's not right. Try again.

Being actively critical

Active reading is about making a conscious effort to understand and evaluate a text for its relevance to your studies. You would actively try to think about what the text is trying to say, for example by making notes or summaries.

Critical reading is about engaging with the text by asking questions rather than passively accepting what it says. Is the methodology sound? What was the purpose? Do ideas flow logically? Are arguments properly formulated? Is the evidence there to support what is being claimed?

When you're reading critically, you're looking to...

- ...link evidence to your own research;

- ...compare and contrast different sources effectively;

- ...focus research and sources;

- ...synthesise the information you've found;

- ...justify your own arguments with reference to other sources.

You're going beyond just an understanding of a text. You're asking questions of it; making judgements about it... What you're reading is no longer undisputed 'fact': it's an argument put forward by an author. And you need to determine whether that argument is a valid one.

"Reading without reflecting is like eating without digesting"

– Edmund Burke

"Feel free to reflect on the merits (or not) of that quote..."

– anon.

Critical reading involves understanding the content of the text as well as how the subject matter is developed...

- How true is what's being written?

- How significant are the statements that are being made?

Regardless of how objective, technical, or scientific the text may be, the authors will have made certain decisions during the writing process, and it is these decisions that we will need to examine.

Two models of critical reading

There are several approaches to critical reading. Here's a couple of models you might want to try:

Choose a chapter or article relevant to your assessment (or pick something from your reading list).

Then do the following:

Determine broadly what the text is about.

Look at the front and back covers

Scan the table of contents

Look at the title, headings, and subheadings

Read the abstract, introduction and conclusion

Are there any images, charts, data or graphs?

What are the questions the text will answer? Write some down.

Use the title, headings and subheadings to write questions

What questions do the abstract, introduction and conclusion prompt?

What do you already know about the topic? What do you need to know?

Do a first reading. Read selectively.

Read a section at a time

Answer your questions

Summarise or make brief notes

Underline or highlight any key points

Recite (in your own words)

Recall the key points.

Summarise key points from memory

Try to answer the questions you asked orally, without looking at the text or your notes

Use diagrams or mindmaps to recall the information

After you have completed the reading…

Go back over your notes and check they are clear

Check that you have answered all your questions

At a later date, review your notes to check that they make sense

At a later date, review the questions and see how much you can recall from memory

Choose a relevant article from your reading list and make brief notes on it using the prompts below.

Choose an article you have read earlier in your course and re-read it, applying the prompts below.

Compare your comments and the notes you have made. What are the differences?

Who is the text by? Who is the text aimed at? Who is described in the text?

What is the text about? What is the main point, problem or topic? What is the text's purpose?

Where is the problem/topic/issue situated?, and in what context?

When does the problem/topic/issue occur, and what is its context? When was the text written?

How did the topic/problem/issue occur? How does something work? How does one factor affect another? How does this fit into the bigger picture?

Why did the topic/problem/issue occur? Why was this argument/theory/solution used? Why not something else?

What if this or that factor were added/removed/altered? What if there are alternatives?

So what makes it significant? So what are the implications? So what makes it successful?

What next in terms of how and where else it's applied? What next in terms of what can be learnt? What next in terms of what needs doing now?

Here's a template for use with the model.

Go to File > Make a copy... to create your own version of the template that you can edit.

CC BY-NC-SA Learnhigher

Arguments & evidence

Academic reading can be a trial. In more ways than one...

It might help to think of every text you read as a witness in a court case. And you're the judge ! You're going to need to examine the testimony...

- What’s being claimed ?

- What are the reasons for making that claim?

- Are there gaps in the evidence?

- Do other witnesses support and corroborate their testimony?

- Does the testimony support the overall case ?

- How does the testimony relate to the other witnesses?

You're going to need to consider all sides of the case...

Considering the argument

An argument explains a position on something. A lot of academic writing is about gathering those claims and explaining your own position through their explanations.

You'll need to question...

- ...the author's claims ;

- ...the arguments they use — are their claims well documented ?;

- ...the counter-arguments presented;

- ...any bias in the source;

- ...the research method being used;

- ...how the author qualifies their arguments.

You'll also need to develop your own reasoned arguments, based on a logical interpretation of reliable sources of information.

What's the evidence?

Evidence isn't just the results of research or a reference to an academic study. You might use other authors' opinions to back up your argument. Keep in mind that some evidence is stronger than others:

weak | — personal opinions of the author; — an attempt to be persuasive; — personal experiences or case studies; — primary or secondary findings or data. |

strong |

You can get an idea of an author's certainty through the language they use, too:

weak | "It that..." "It that..." "There's that..." |

strong |

Linking evidence to argument

- Why did the author select the evidence they did? — Why did they decide to use a particular methodology, choose a specific method, or conduct the work in the way they did?

- How does the author interpret the evidence?

- How does the evidence prove or help the argument?

Even in the most technical and scientific disciplines, the presentation of argument will always involve elements that can be examined and questioned. For example, you could ask:

- Why did the author select that particular topic of enquiry in the first place?

- Why did the author select that particular process of analysis?

Synthesis :

"the combination of components or elements to form a connected whole."

You'll need to make logical connections between the different sources you encounter, pulling together their findings. Are there any patterns that emerge?

Analyse the texts you've found, and how meaningful they are in context of your studies...

- How do they compare to each other and to any other knowledge you are gathering about the subject? Do some ideas complement or conflict with each other?

- How will you synthesise the different sources to serve an idea you are constructing? Are there any inferences you can draw from the material?

Embracing other perspectives

Good critical research seeks to be impartial, and will embrace (or, at the very least, address) conflicting opinions. Try to bring these into your research to show comprehensive searching and knowledge of the subject.

You can strengthen your argument by explaining, critically, why one source is more persuasive than another.

Recall & review

Synthesising research is much easier if you take notes. When you know an article is relevant to your area of research, read it and make notes which are relevant to you. Consider keeping a spreadsheet or something similar , to make a note of what you have read and how it relates to the task.

You don't need elaborate notes; just a summary of the relevant details. But you can use your notes to help with the process of analysing and synthesising the texts. One method you could try is the recall & review approach:

Try to summarise key words and elements of the text:

- Sketch a rough diagram of the text from memory — test what you can recall from your reading of the text;

- Make headings of the main ideas and note the supporting evidence;

- Include your evaluation — what were the strengths and weaknesses?

- Identify any gaps in your memory.

Go over your notes, focusing on the parts you found difficult. Organise your notes, re-read parts, and start to bring everything together...

- Summarise the text in preparation for writing;

- Be creative: use colour and arrows; make it easy to visualise;

- Highlight the ideas you may want to make use of;

- Identify areas for further research.

Critical analysis vs criticism

The aim of critical reading and critical writing is not to find fault; it's not about focusing on the negative or being derogatory. Rather it's about assessing the strength of the evidence and the argument. It's just as useful to conclude that a study or an article presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument as it is to identify weak evidence and poorly formed arguments.

Criticising

The author's argument is poor because it is badly written.

Critical analysis

The author's argument is unconvincing without further supporting evidence.

Academic reading: What it is and how to do it

Struggling with academic reading? This bitesize workshop breaks it down for you! Discover how to read faster, smarter, and make those academic texts work for you:

Think critically about what you read...

- examine the evidence or arguments presented

- check out any influences on the evidence or arguments

- check out the limitations of study design or focus

- examine the interpretations made

Active critical reading

It's important to take an analytical approach to reading the texts you encounter. In the concluding part of our " Being critical " theme, we look at how to evaluate sources effectively, and how to develop practical strategies for reading in an efficient and critical manner.

Forthcoming training sessions

Forthcoming sessions on :

CITY College

Please ensure you sign up at least one working day before the start of the session to be sure of receiving joining instructions.

If you're based at CITY College you can book onto the following sessions by sending an email with the session details to your Faculty Librarian:

There's more training events at:

- << Previous: Reading academic articles

- Next: Critical writing >>

- Last Updated: Sep 16, 2024 3:31 PM