Sharing teaching and learning resources from the National Archives

Education Updates

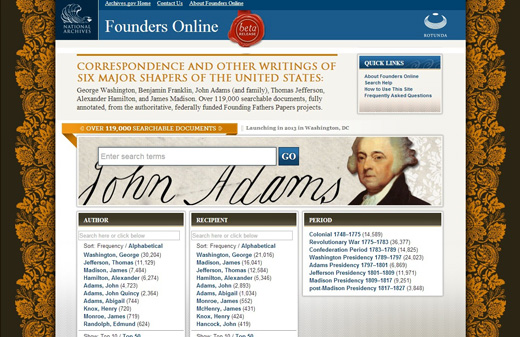

Access the Writings of the Founding Fathers on Founders Online

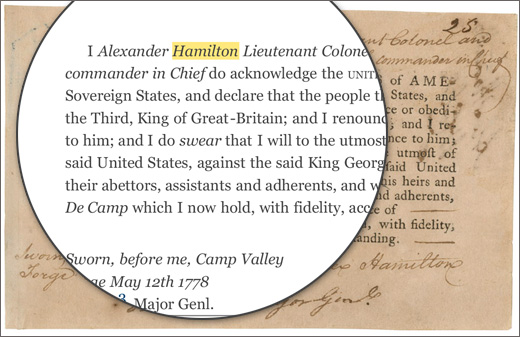

You can read and search through thousands of transcriptions of records from George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. You and your students can access the written record of the original thoughts, ideas, debates, and principles of our democracy.

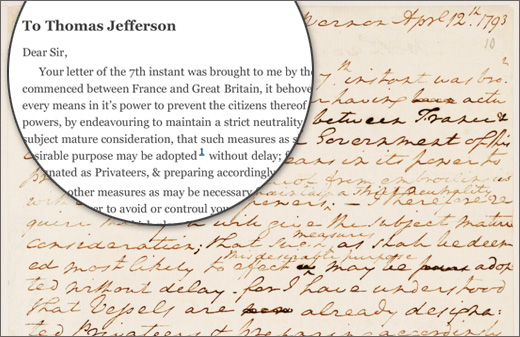

For example, if you find this letter from George Washington to Thomas Jefferson regarding the neutral role of the United States in the War Between Great Britain and France—in the holdings of the National Archives and available on DocsTeach—you can find its transcription on Founders Online :

Search across the records of all six Founders and read first drafts of the Declaration of Independence, the spirited debate over the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and the very beginnings of American law, government, and our national story. You can compare and contrast the thoughts and ideas of these six individuals and their correspondents as they discussed and debated through their letters and documents.

You—or your students—can use the site to:

- Research a person : Search by author and recipient, or for someone mentioned in the writing of another.

- Research a time period : Choose a predefined time period and then narrow the results with search terms. Or enter a start date, end date, or both.

- Research a concept : Experiment with search terms. For example, you can search for concepts like liberty , freedom , bill of rights, freedom of the press, or checks and balances . (The site includes instructions and strategies for searching.)

The website was created by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission , the grant-making arm of the National Archives, and The University of Virginia Press.

Share this:

3 thoughts on “ access the writings of the founding fathers on founders online ”.

This resource is breathtaking in its scope and value. I already have student accessing it for their class projects. It defies description. Powerful, powerful resource.

Thanks, John! We’d love to hear your feedback about using the site.

This site just made so many founding fathers geeks soooo happy! Thank you to our government!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

Correspondence and other writings of seven major shapers of the united states:.

George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams (and family), Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Over 184,000 searchable documents, fully annotated, from the authoritative Founding Fathers Papers projects.

Quick links

- About Founders Online

- Major Funders

- Search Help

- How to Use This Site

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Teaching Resources

Sort: Frequency / Alphabetical

- Washington, George (31,728)

- Jefferson, Thomas (20,531)

- Adams, John (10,097)

- Madison, James (8,663)

- Hamilton, Alexander (7,632)

- Franklin, Benjamin (4,918)

- Adams, John Quincy (3,524)

- Jay, John (1,771)

- Adams, Abigail (1,287)

- Monroe, James (993)

Show: Top 10 / Top 50

- Jefferson, Thomas (27,035)

- Washington, George (22,801)

- Madison, James (19,677)

- Franklin, Benjamin (9,482)

- Adams, John (8,742)

- Hamilton, Alexander (6,824)

- Jay, John (1,613)

- Adams, Abigail (1,602)

- Adams, John Quincy (1,110)

- Lee, Arthur (952)

- Colonial 1706–1775 (16,105)

- Revolutionary War 1775–1783 (48,379)

- Confederation Period 1783–1789 (17,804)

- Washington Presidency 1789–1797 (27,165)

- Adams Presidency 1797–1801 (13,566)

- Jefferson Presidency 1801–1809 (29,479)

- Madison Presidency 1809–1817 (15,472)

- post-Madison Presidency 1817–1836 (15,436)

History News Network puts current events into historical perspective. Subscribe to our newsletter for new perspectives on the ways history continues to resonate in the present. Explore our archive of thousands of original op-eds and curated stories from around the web. Join us to learn more about the past, now.

Sign up for the HNN Newsletter

The Founding Fathers: Their Achievement and Failures

The Achievement

More specifically, the Founding Fathers managed to defy conventional wisdom in four unprecedented achievements: first, they won a war for colonial independence against the most powerful military and economic power in the world; second, they established the first large-scale republic in the modern world; third, they invented political parties that institutionalized the concept of a legitimate opposition; fourth, they established the principle of the legal separation of church and state, though it took several decades for that principle to be implemented in all the states. Finally, all these achievements were won without recourse to the guillotine or the firing-squad wall, which is to say without the violent purges that accompanied subsequent revolutions in France, Russia, and China. This was the overarching accomplishment that the British philosopher Alfred Lord North Whitehead had in mind when he observed that there were only two instances in the history of Western civilization when the political elite of an emerging empire behaved as well as one could reasonably expect: the first was Rome under Caesar Augustus, and the second was the United States under the Founding Fathers.

The Failure

Slavery was incompatible with the values of the American Revolution, and all the prominent members of the revolutionary generation acknowledged that fact. In three important areas they acted on this conviction: first, by ending the slave trade in 1808; second, by passing legislation in all the states north of the Potomac that put slavery on the road to ultimate extinction; third, by prohibiting the expansion of slavery into the Northwest Territory. But in all the states south of the Potomac, where some nine-tenths of the slave population resided, they failed to act. Indeed, by insisting that slavery was a matter of state rather than federal jurisdiction, they implicitly removed the slavery question from the national agenda. This decision had catastrophic consequences, for it permitted the enslaved population to grow in size eightfold (from 500,000 in 1775 to 4,000,000 in 1860), mostly by natural reproduction, and to spread throughout all the southern states east of the Mississippi River. And at least in retrospect, their failure to act decisively before the slave population swelled so dramatically rendered the slavery question insoluble by any means short of civil war.

There were at least three underlying reasons for this tragic failure. First, many of the Founders mistakenly believed that slavery would die a natural death, that decisive action was unnecessary because slavery would not be able to compete successfully with the wage labor of free individuals. They did not foresee the cotton gin and the subsequent expansion of the Cotton Kingdom. Second, all the early efforts to place slavery on the national agenda prompted a threat of secession by the states of the Deep South (South Carolina and Georgia were the two states who actually threatened to secede, though Virginia might very well have chosen to join them if the matter came to a head), a threat especially potent during the fragile phase of the early American republic. While most of the Founders regarded slavery as a malignant cancer on the body politic, they also believed that any effort to remove it surgically would in all likelihood kill the young nation in the cradle. Finally, all conversations about abolishing slavery were haunted by the specter of a free African American population, most especially in those states south of the Potomac where in some locations blacks actually outnumbered whites. None of the Founding Fathers found it possible to imagine a biracial American society, an idea that, in point of fact, did not achieve broad acceptance in the United States until the middle of the 20th century.

Given these prevalent convictions and attitudes, slavery was that most un-American item, an inherently intractable and insoluble problem. As Jefferson so famously put it, the founders held "the wolfe by the ears," and could neither subdue him nor afford to let him go. Virtually all the Founding Fathers went to their graves realizing that slavery, no matter how intractable, would become the largest and most permanent stain on their legacy. And when Abraham Lincoln eventually made the decision that, at terrible cost, ended slavery forever, he did so in the name of the Founders.

The other tragic failure of the Founders, almost as odious as the failure to end slavery, was the inability to implement a just policy toward the indigenous inhabitants of the North American continent. In 1783, the year the British surrendered control of the eastern third of North America in the Treaty of Paris, there were approximately 100,000 American Indians living between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi. The first census (1790) revealed that there were also 100,000 white settlers living west of the Alleghenies, swelling in size every year (by 1800 they would number 500,000) and moving relentlessly westward. The inevitable collision between these two peoples posed the strategic and ultimately the moral question: How could the legitimate rights of the Indian population be reconciled with the demographic tidal wave building to the east?

In the end, they could not. Although the official policy of Indian removal east of the Mississippi was not formally announced and implemented until 1830, the seeds of that policy--what one historian has called "the seeds of extinction" -- were planted during the founding era, most especially during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson (1801-09).

One genuine effort to avoid that outcome was made in 1790 during the presidency of George Washington. The Treaty of New York with the Creek tribes of the early southwest proposed a new model for American policy toward the Indians, declaring that they should not be regarded as a conquered people with no legal rights, but rather as a collection of sovereign nations. Indian policy was therefore a branch of foreign policy, and all treaties were solemn commitments by the federal government not subject to challenge by any state or private corporation. Washington envisioned a series of American Indian enclaves or homelands east of the Mississippi whose borders would be guaranteed under federal law, protected by federal troops, and bypassed by the flood of white settlers. But, as it soon became clear, the federal government lacked the resources in money and manpower to make Washington's vision a reality. And the very act of· claiming executive power to create an Indian protectorate prompted charges of monarchy, the most potent political epithet of the age. Washington, who was accustomed to getting his way, observed caustically that nothing short of "a Chinese Wall" could protect the Native American tribes from the relentless expansion of white settlements. Given the surging size of the white population, it is difficult to imagine how the story could have turned out differently.

Founding Fathers of America Research Paper

The United States of America draws its greatness from its founding fathers who fought for its independence and worked hard to unite the country. The founding fathers of the country include people who actively contributed to the constitution by drafting and signing its declaration. This may also include politicians, public officials, jurists, warriors, civil servants, or ordinary citizens who participated in winning the United States independence.

There are seven key founding fathers of the United States of America; John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington.

They were the political leaders and public officials who took part in the country’s revolutionary war and signed the Declaration of Independence. They also include people who drafted the Constitution and made other key contributions. They are thus the delegates who had a significant direct or indirect effect on the constitution (Henretta, Edwards & Self, 2011).

This paper will identify and discuss three key founding fathers from the 1700s who I believe played the most important role in establishing the United States of America. They include George Washington, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson.

George Washington was the first president of America and served as the commander of the US army during the revolutionary war, which took place between the years 1775-1783. He is referred to as the founding father of the nation for the role he played in fighting for independence.

The national congress appointed George Washington as a commander in chief of its armed forces in 1775 (Stanfield, 2001). In 1776, he drove the British out of Boston and by the end of that year; he had captured most of the country’s territory. George Washington led a strong army and a powerful nation against threats of disintegration and collapse. In 1787, Washington was the head of the Philadelphia tenet that drafted the U.S constitution and in 1787, he became the head of the United States of America (Rutland, 1997).

As a president, he established many customs and assigned more work to the executive arm of government in an attempt to unite the country in a time it was facing international threats. In 1793, he declared the country neutral to foreign relations and this helped the country avoid conflicts.

As a founding father of United States of America, Washington supported all the policies aimed at building a strong central regime. He settled the nations’ debt, executed an efficient tax system, and created a bank where the American citizens could save their money (Adler, 2008). He always evaded the temptation of international conflicts and battles by ensuring that peace was maintained in the nation. Although Washington was not a member of the Federalist Party, he was its motivating leader and supported its policies and activities.

He strongly supported the republican principles and warned against bias, sectionalism, and international conflicts. His refusal to engage in political conflicts buttressed his character as a man dedicated to the military nation and a founding father of the nation. Newspapers in the United States thus extolled Washington’s character and traits as a military commander and a founder of the nation (Rutland, 1997).

James Madison was another founding father of the United States of America. He was an American politician and between the years 1809-1817, he served as the fourth head of state. He was the main author of the nation’s constitution and in 1788, he wrote the most powerful commentary on the United States Constitution.

As a founding father of America, he drafted many rules and is responsible for the first ten alterations in the constitution. Due to this, he is referred to as the “Father of the Bill of Rights” (Allen, 1997). He believed that America’s constitution needed regular checks to protect the rights of the citizens from oppression (Allen, 1997).

James Madison worked with George Washington to create the current central government in America. He opposed the key principles of the federalists and established the Democratic Republican Party (DRP), which acted against Foreign and Sedition Acts. As a founding father, he led the nation into war against Britain in 1812.

In 1815, he supported the idea of creating the second national bank since this would protect the nation’s new industries, which had been established during the war. James Madison held cabinet meetings regularly to discuss the country’s problems before making any decision. When handling habitual tasks, he was systematic, orderly and allowed others to give their opinions (Allen, 1997).

Thomas Jefferson was a founding father of the United States of America and was instrumental during the Revolutionary war. Before the struggle for independence, he was active in defending America from being made a Royal Colony. Thomas actively organized oppositions to the colonial government and in 1774, he wrote a pamphlet titled ‘A Summary View of the Rights of British America’ where he articulated colonialism and encouraged the American citizens to continue fighting for independence (Biographiq, 2008).

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson opposed America’s constitution by saying that it ignored the people it was meant for. He said, “The Senate does not appear to me to be a Child of the people at Large, and therefore will not be supported by them longer than there subsists the most perfect Union between the different Legislative branches” (Biographiq, 2008). In 1778, he represented America in the Continental Congress and served as the head of the nation’s first senate in 1780.

Between 1782 and 1785, Thomas served as the manager of the nation’s finances. He is credited for helping the nation the financial depression caused by the war. As a founding father of the nation, he was increasingly interested in national affairs and always looked for ways of solving the financial and political problems that had resulted from the ineffectiveness of the Articles of Confederation (Biographiq, 2008).

He attended a Conference in Mount Vernon, which led to the new constitution. Thomas favored a strong and enduring union of the nation in which a senate representing the citizens had the authority to impose taxes on the people.

Concerned with the permanence of the new government, he argued that frequent elections could result to indifferences hence make famous men reluctant in office seeking. As a founding father of America, Jefferson’s good humor and enjoyable company endeared him to many people. He used this to help settle the opposing opinions of the delegates and created the compromises that have made America a success (Biographiq, 2008).

Looking at the achievements and the contributions these great men had in shaping the history of America, they are truly the founding fathers of the country. The three individuals were remarkable in the building of a strong society that we proudly call the United States of America today. They fought and sacrificed to see the country attain independence and put in place the governing structures that have helped America to be the greatest nation in the world.

Adler, B. (2008). America’s founding fathers: their uncommon wisdom and wit. Lanham: Taylor Trade Pub.

Allen, R. (1997). James Madison: the founding father. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Biographiq. (2008). Thomas Jefferson – Founding Father (Biography). Minneapolis: Filiquarian Pub.

Henretta, A., Edwards, R., & Self, O. (2011). America’s History . New York: Bedford Martins.

Rutland, R. A. (1997). The Founding Father. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Stanfield, J. (2001). America’s Founding Fathers: Who Are They? Thumbnail Sketches of 164 Patriots. Parkland: Universal Publishers.

- Sojourner Truth

- Colin Powell Leadership Characteristics

- The Founding Fathers and Their Rebellion Against the Crown

- Founding Fathers as Democratic Reformers

- James Madison and the United States Constitution

- Julius Caesar and Rome

- Karl Marx Ideologies and His Influence in the 21st Century

- Diogenes and Alexander

- The Life of Benjamin Franklin

- "My Grandfather's Son" by Clarence Thomas: A Memoir

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 17). Founding Fathers of America. https://ivypanda.com/essays/founding-fathers-of-america/

"Founding Fathers of America." IvyPanda , 17 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/founding-fathers-of-america/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Founding Fathers of America'. 17 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Founding Fathers of America." October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/founding-fathers-of-america/.

1. IvyPanda . "Founding Fathers of America." October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/founding-fathers-of-america/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Founding Fathers of America." October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/founding-fathers-of-america/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

The Vision Of The Founding Fathers

What kind of nation did the Founders aim to create?

Men, not vast, impersonal forces — economic, technological, class struggle, what have you — make history, and they make it out of the ideals that they cherish in their hearts and the ideas they have in their minds. So what were the ideas and ideals that drove the Founding Fathers to take up arms and fashion a new kind of government, one formed by reflection and choice, as Alexander Hamilton said, rather than by accident and force?

The worldview out of which America was born centered on three revolutionary ideas, of which the most powerful was a thirst for liberty. For the Founders, liberty was not some vague abstraction. They understood it concretely, as people do who have a keen knowledge of its opposite. They understood it in the same way as Eastern Europeans who have lived under Communist tyranny, for instance, or Jews who escaped the Holocaust.

The Plymouth Pilgrims were only the first of many who came to the New World to escape religious persecution. Hard as it may be to believe it at this distance of time, British law once forbade non-Anglican Protestants to worship freely — jailing and even burning them for dissenting in the 16th and 17th centuries, and then, more liberally, fining them — and it barred them (along with Catholics and Jews) from the great universities and from political office. In response, thousands of Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers, and others fled. Not incidentally, they brought with them their dissenting tradition of governing their own congregations and hiring and firing their own ministers — in other words, they brought to these shores a political culture of self-government. Moreover, because they were accustomed to reading the Bible and feeling free to judge its meaning for themselves — to believing, that is, that they had a direct relation to God and his word independent of any worldly institution or authority — they also brought a deeply rooted culture of individualism and personal responsibility. For them, the individual and his conscience were of preeminent importance.

William Livingston, a signer of the Constitution and longtime governor of New Jersey, had earlier, in the 1750s, run a journal that was key in turning the American mind toward revolution. In one issue he reminded his readers how “the countless Sufferings of your pious Predecessors for Liberty of Conscience, and the Right of private Judgment,” drove them “to this country, then a dreary Waste and barren Desert.” His own Presbyterian grandfather was among those pious predecessors. John Jay, our first chief justice, wrote a gripping account of how his paternal grandfather, a French Protestant, returned home to La Rochelle from a trading voyage abroad to find his parents, siblings, and neighbors gone. Their houses were occupied by soldiers, their church destroyed, their savings confiscated. While he had been away, he learned, France had revoked its toleration of the Huguenots. He was lucky to be able to sneak aboard a ship and sail away to freedom in the New World. Jay's maternal grandparents similarly had to flee anti-Protestant persecution, one from Paris and one from Bohemia. Jay's son and biographer tells us this proudly; it was a living family legend.

As Edmund Burke warned his fellow members of Parliament four weeks before Lexington and Concord, when it was already too late, “All protestantism . . . is a sort of dissent,” but American Protestantism “is a refinement on the principle of resistance; it is the dissidence of dissent, and the protestantism of the protestant religion.” Whatever might be the differences among the American Protestant sects, he said, they all agree “in the communion of the spirit of liberty.”

Long before Emma Lazarus wrote about the huddled masses yearning to breathe free, George Washington noted that for “the poor, the needy, & the oppressed of the Earth,” America was already what he called “the second Land of promise.” This Promised Land offered, said James Madison, “an Asylum to the persecuted and oppressed of every Nation and Religion.”

In fact, for Madison — who studied at Princeton under the radical Scottish-born Presbyterian John Witherspoon — it was red-hot outrage over a remnant of religious oppression in the New World that drove him, until then a sickly and directionless youth, into a political career. Virginia, where Anglicanism was still the official, established religion until the Revolution, had jailed a group of Baptist preachers for their unorthodox religious writings. If you aren't free to think your own thoughts and believe your own beliefs, fumed Madison, you aren't free, period, since freedom is seamless. And as a practical matter, there can be no progress without intellectual freedom. So when the 25-year-old revolutionary took part in drafting Virginia's Declaration of Rights, he rejected its original provision for religious toleration. It's not government's business to “tolerate” somebody's beliefs, he maintained. You are free to think whatever your reason convinces you is true, government or no government; and that's what the Declaration of Rights ended up saying. Madison would never use Thomas Jefferson's high-flown language, but he certainly agreed with his close friend's sentiment that “I have sworn upon the altar of god, eternal hostility to every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” These men knew what it meant to individuals and to a whole culture to have to parrot an official orthodoxy, or else remain silent — and they knew what physical tyrannies such unfreedom of belief could unleash.

It is a deeply tragic paradox that the Founders also valued liberty so highly because they lived amidst slavery. Even the slave-owners among them knew how obscenely unjust the institution was. “The whole commerce between master and slave,” wrote Jefferson, “is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.” I needn't detail the crushing toil, the sadistic punishments, the sexual exploitation, the break-up of families, the enforced ignorance, and the regulation of every aspect of life comprehended in Jefferson's decorous statement of the inhumanity of which human nature is capable.

In 1759, more than a century before the Civil War, Richard Henry Lee of Stratford Hall, later president of the Continental Congress (and incidentally a cousin of the Stratford-born Robert E. Lee), made his maiden speech in the Virginia House of Burgesses. His message to his fellow slave-owners: End slavery. How can anyone who calls himself a Christian, he demanded, think that “our fellow-creatures . . . are no longer to be considered as created in the image of God as well as ourselves, and equally entitled to liberty and freedom by the great law of nature?” On a more down-to-earth level, he pointed out that slaves who see their masters living in luxury and freedom, “whilst they and their posterity are subjected for ever to the most abject and mortifying slavery,” must become “natural enemies to society, and their increase consequently dangerous.”

Jefferson, who had written in the Declaration that all men are created equal, wrote in 1786, in words that prefigure Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural, “When the measure of their tears shall be full, when their groans shall have involved heaven itself in darkness, doubtless a god of justice will awaken to their distress, and by diffusing light and liberality among their oppressors, or at length by his exterminating thunder, manifest his attention to the things of this world, and that they are not to be left to the guidance of a blind fatality.”

So when the young and pigheaded King George III began meddling in American affairs after decades of an official British policy of “salutary neglect” toward the New World colonies, the Founders had a ready explanation for his intentions. The king, Washington concluded in 1774, aimed “to make us as tame, & abject Slaves, as the Blacks we Rule over with such arbitrary Sway” — a sentiment whose full implications it took General Washington a lifetime to grasp: He finally freed his slaves on his deathbed. Even earlier, Richard Henry Lee's brother Arthur, who became one of the Revolution's foreign agents, declared, “I cannot Conceive of the Necessity of becoming a Slave, while there remains a Ditch in which one may die free.” For such men, liberty wasn't just a word. They could feel it and taste it. Choosing your beliefs, your thoughts, your job, your officials, your laws, your taxes — being equal citizens before a law that was the same for all — they never took these freedoms for granted.

The Founders believed that the purpose of government was to protect life, liberty, and property from what they called the depravity of human nature — from man's innate capacity to do the kinds of violence that slave-owners, to take just one example, did every day. But government, they recognized, is a double-edged sword. You arm officials with the power to protect you; but those officials have the same fallen human nature as everyone else, so who is to say that they won't use that power to oppress you, as European governments had oppressed the colonists' forebears? From Pharaoh to Nero to the Stuart kings, history teems with examples of such despotic governments. Even the democratic republic the Founders created had to be run by imperfect men, and thus even it could turn into what Richard Henry Lee called an elective despotism. So the second great Founding idea is this: The mere fact that you elect representatives to govern you is no sure-fire guarantee of liberty. Or, as Madison saw it in Federalist No. 10: Taxation with representation can be tyranny.

This danger worried the Founders constantly, and they struggled to protect their new government from it. Their first experiment was to make that government too weak to oppress them. But it was also, they found, too weak to do its chief job of protecting them against violence. The Revolutionary War proved longer and harder than it need have been, since the central government lacked authority to tax in order to pay soldiers or buy arms. But when the Founders set out to write a new Constitution to give the federal government powers sufficient to its purpose, they did so with their hearts in their mouths. They strictly limited those powers to what they deemed absolutely essential, and they carefully spelled out what those powers were. They divided and subdivided power, and made each branch of government a check on the others, to guard against overreaching. They required frequent elections, gave the president a veto, and in turn made him and other officials subject to impeachment.

Madison, the Constitution's chief designer, constructed his exquisitely balanced mechanism to work by the power of ambition countering ambition, and interest countering interest. A realist about human nature, like most of the Founders, he devised a government for ordinary men as they really were, not for prodigies of virtue. Even so, he conceded, there had to be at least a smidgen of virtue somewhere. If “there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government,” he wrote, then only “the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring each other.”

Washington was even more explicit about this, the third of the great Founding ideas: A democratic republic requires a special kind of culture, one that nurtures self-reliance and a love of liberty. Constitutions are all very well, the Founders often observed, but they are only “parchment barriers,” easily breached if demagogues subvert the “spirit and letter” of the document. They can do this dramatically, in one revolutionary putsch, or they can inflict a death by a thousand cuts, gradually persuading citizens that the Constitution doesn't mean what it says but should be interpreted to mean something different, or even something opposite.

The ultimate safeguard against such usurpation is the vitality of America's culture of liberty. In his first State of the Union speech, Washington stressed this point, emphasizing a view universal among the Founders. The “security of a free Constitution,” he said, depends on “teaching the people themselves to know and to value their own rights; to discern and provide against invasions of them; to distinguish between oppression and the necessary exercise of lawful authority; . . . to discriminate the spirit of liberty from that of licentiousness,” and to unite “a speedy, but temperate vigilance against encroachments, with an inviolable respect for the laws.” If citizens start to take liberty for granted, if their culture — molded by journalists and writers, preachers and teachers — starts to hold other values in higher esteem, then the spirit that gives life to the Constitution will flicker out. Americans, Washington wrote on another occasion, should guard against “listlessness for the preservation of natural and unalienable rights,” for “no mound of parchm[en]t can be so formed as to stand against the sweeping torrent of boundless ambition on the one side, aided by the sapping current of corrupted morals on the other.”

The Founders well understood, as John Adams reminisced in 1818, that it was a change in the “principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections” of Americans that had sparked the Revolution. They considered that new culture of freedom that had arisen among them in the decades before Lexington and Concord, along with the new Constitution they created, to be the most precious inheritance they bequeathed to future generations of their fellow citizens. That vision offers us an instructive standard by which to gauge the present.

This piece originally appeared in National Review Online

Further Reading

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Public Safety

- Publications

- Research Integrity

- Press & Media

EIN #13-2912529

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Patrick Henry

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 20, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Patrick Henry was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and the first governor of Virginia. A gifted orator and major figure in the American Revolution, his rousing speeches—which included a 1775 speech to the Virginia legislature in which he famously declared, “Give me liberty, or give me death!”—fired up America’s fight for independence. An outspoken Anti-Federalist, Henry opposed the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, which he felt put too much power in the hands of a national government. His influence helped create the Bill of Rights, which guaranteed personal freedoms and set limits on the government’s constitutional power.

Early Years

Patrick Henry was born in 1736 to John and Sarah Winston Henry on his family’s farm in Hanover County , Virginia . He was educated mostly at home by his father, a Scottish-born planter who had attended college in Scotland.

Henry struggled to find a profession as a young adult. He failed in several attempts as a storeowner and a planter. He taught himself law while working as a tavern keeper at his father-in-law’s inn and opened a law practice in Hanover County in 1760.

As a lawyer and politician, Patrick Henry was known for his persuasive and passionate speeches, which appealed as much to emotion as to reason. Many of Henry’s contemporaries likened his rhetorical style to the evangelical preachers of the Great Awakening , a religious revival that swept the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s.

Parson’s Cause

Henry’s first major legal case was known as the Parson’s Cause in 1763, a dispute involving Anglican clergy in colonial Virginia. The case – one of the first legal attempts to challenge the limits of England’s power over the American colonies – is often viewed as an important event leading up to the American Revolution .

Ministers of the Church of England in Virginia were paid their annual salaries in tobacco. A tobacco shortage caused by drought led to price increases in the late 1750s.

In response, the Virginia legislature passed the Two-Penny Act , which set the value of the Anglican ministers’ annual salaries at two pennies per pound of tobacco, rather than the inflated price, which was closer to six pennies per pound. The Anglican clergy appealed to Britain’s King George III , who overturned the law and encouraged ministers to sue for back pay.

The Parson’s Cause established Patrick Henry as a leader in the emerging movement for American independence. During the case, Henry, then a relatively unknown attorney, delivered an impassioned speech against British overreach into colonial affairs, arguing “that a King by annulling or disallowing acts of so salutary a nature, from being Father of his people degenerated into a Tyrant, and forfeits all rights to his subjects’ obedience.”

The Stamp Act of 1765 required American colonists to pay a small tax on every piece of paper they used. Colonists viewed the Stamp Act—an attempt by England to raise money in the colonies without approval from colonial legislatures—as a troublesome precedent.

Patrick Henry responded to the Stamp Act with a series of resolutions introduced to the Virginia legislature in a speech. The resolves, adopted by the Virginia legislature, were soon published in other colonies, and helped to articulate America’s stance against taxation without representation under the British Crown.

Henry’s resolves declared that Americans should be taxed only by their own representatives and that Virginians should pay no taxes except those voted on by the Virginia legislature.

Later in the speech, Henry flirted with treason when he hinted that the King risked suffering the same fate as Julius Caesar —assassination—if he maintained his oppressive policies.

Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death

In March of 1775, the Second Virginia Convention met at St. John’s Church in Richmond to discuss the state’s strategy against the British. It was here that Patrick Henry delivered his most famous speech.

“Gentlemen may cry, ‘Peace, Peace,’ but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? ... Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!"

George Washington , Thomas Jefferson and five of the six other Virginians who would later sign the Declaration of Independence were in attendance that day. Historians say that Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech helped convince those in attendance to begin preparing Virginia troops for war against Great Britain.

Royal Governor Lord Dunmore responded to the speech by removing gunpowder from the magazine. That November, he would issue Dunmore’s Proclamation declaring martial law in Virginia and promising freedom to enslaved people who joined the King’s cause.

Henry spoke without notes, and no transcripts exist from his famous address. The only known version of the speech was reconstructed in an 1817 biography of Henry by author William Wirt, leading some historians to speculate that the famous Patrick Henry quote may have been fabricated by Wirt to sell copies of his book.

Henry and Slavery

Patrick Henry married his first wife, Sarah Shelton, in 1754, and the couple went on to have six children together. Her dowry included a 600-acre farm, a house, and six enslaved people.

After Sarah died in 1775, he married Dorothea Dandridge of Tidewater, Virginia, and their union produced eleven children.

Despite the size of his family, Henry and his family lived in a small farmhouse on a Piedmont-area plantation known as Red Hill. Henry once referred to slavery as a “lamentable evil,” but throughout his adult life Henry owned dozens of enslaved persons, some of whom worked the fields at Red Hill.

Anti-Federalism and the Bill of Rights

Patrick Henry served as Virginia’s first governor (1776-1779) and sixth governor (1784-1786).

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War , Henry became an outspoken Anti-Federalist. Henry and other Anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the 1787 United States Constitution , which created a strong federal government.

Patrick Henry worried that a federal government that was too powerful and too centralized could evolve into a monarchy. He was the author of several Anti- Federalist Papers —written arguments by Founding Father’s who opposed the U.S. Constitution.

While the Anti-Federalists were unable to stop the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the Anti-Federalist Papers were influential in helping to shape the Bill of Rights . The first 10 Amendments to the United States Constitution, known collectively as the Bill of Rights, protected individual liberties and placed limits on the powers of the federal government.

Besides a brief stint as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress —the United States government during the American Revolution—Patrick Henry never held national public office.

He died on June 6, 1799 at the age of 63 from stomach cancer. His Southern Virginia plantation is now the Red Hill Patrick Henry National Memorial .

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Henry’s Full Biography; Red Hill Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation .

Patrick Henry Arguing the Parson’s Cause; Virginia Museum of History and Culture .

A Summary of the 1765 Stamp Act; Colonial Williamsburg .

Patrick Henry, Orator of Liberty; U.S. Library of Congress .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Jump to main content

Jump to navigation

- Latest News Read the latest blog posts from 1600 Pennsylvania Ave

- Share-Worthy Check out the most popular infographics and videos

- Photos View the photo of the day and other galleries

- Video Gallery Watch behind-the-scenes videos and more

- Live Events Tune in to White House events and statements as they happen

- Music & Arts Performances See the lineup of artists and performers at the White House

- Your Weekly Address

- Speeches & Remarks

- Press Briefings

- Statements & Releases

- White House Schedule

- Presidential Actions

- Legislation

- Nominations & Appointments

- Disclosures

- Cabinet Exit Memos

- Criminal Justice Reform

- Civil Rights

- Climate Change

- Foreign Policy

- Health Care

- Immigration Action

- Disabilities

- Homeland Security

- Reducing Gun Violence

- Seniors & Social Security

- Urban and Economic Mobility

- President Barack Obama

- Vice President Joe Biden

- First Lady Michelle Obama

- Dr. Jill Biden

- The Cabinet

- Executive Office of the President

- Senior White House Leadership

- Other Advisory Boards

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- National Security Council

- Joining Forces

- Reach Higher

- My Brother's Keeper

- Precision Medicine

- State of the Union

- Inauguration

- Medal of Freedom

- Follow Us on Social Media

- We the Geeks Hangouts

- Mobile Apps

- Developer Tools

- Tools You Can Use

- Tours & Events

- Jobs with the Administration

- Internships

- White House Fellows

- Presidential Innovation Fellows

- United States Digital Service

- Leadership Development Program

- We the People Petitions

- Contact the White House

- Citizens Medal

- Champions of Change

- West Wing Tour

- Eisenhower Executive Office Building Tour

- Video Series

- Décor and Art

- First Ladies

- The Vice President's Residence & Office

- Eisenhower Executive Office Building

- Air Force One

- The Executive Branch

- The Legislative Branch

- The Judicial Branch

- The Constitution

- Federal Agencies & Commissions

- Elections & Voting

- State & Local Government

Search form

The papers of the founding fathers are now online.

What was the original intent behind the Constitution and other documents that helped shape the nation? What did the Founders of our country have to say? Those questions persist in the political debates and discussions to this day, and fortunately, we have a tremendous archive left behind by those statesmen who built the government over 200 years ago.

For the past 50 years, teams of editors have been copying documents from historical collections scattered around the world that serve as a record of the Founding Era. They have transcribed hundreds of thousands of documents—letters, diaries, ledgers, and the first drafts of history—and have researched and provided annotation and context to deepen our understanding of these documents.

These papers have been assembled in 242 documentary editions covering the works of Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison, as well as hundreds of people who corresponded with them. Now for the first time ever, these documents—along with thousands of others that will appear in additional print volumes—will be available to the public.

The Founders Online is a new website at the National Archives that will allow people to search this archive of the Founding Era, and read just what the Founders wrote and discussed during the first draft of the American democracy. Students and researchers, citizens and scholars can turn to Founders Online to track and debate the meaning of documents such as the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. They can examine transcriptions of the originals and read the wit and wisdom of the Founders’ own debates.

The great minds who fiercely debated the founding of our country rarely agreed on public policy for the new nation, though they were unanimous in support of the principles and underlying idea of the United States. Here are a few possibilities for using Founders Online :

- Assemble the Founders' views on slavery into a single set of search results in which many of the original documents do not use the word at all.

- Collect all the correspondence between Adams and Jefferson along with their contemporaries' views on each man to create a richer portrait on their fraught relationship and lasting friendship.

- Trace the Founders' letters and diaries and debates leading up to the Constitutional Convention, their thoughts during the meetings in Philadelphia, the ratification of the Constitution by the states, and how the Washington administration, first Congress, and first Supreme Court implemented the grand experiment.

- Find insights into their private lives: the devotion expressed in the letters between John and Abigail Adams; Madison’s views on slavery; Hamilton’s feud that led to the fatal duel with Burr; the stuffed moose sent to Jefferson in Paris; Ben Franklin’s turkey; and yes, Washington’s decades-long problems with his teeth.

The Founders Online continues that experiment in democracy by making freely available in one place the original words of the original statesmen. Although it holds only a small portion of the primary source material, the National Archives is an ideal home for this collection.

Now today's best minds will have the chance to contrast and compare the Founders' words and ideas through the Internet—a communications medium that none of the Founders could foresee—though all would acknowledge it as a democratizing force. The words of the Founders belong online, where people across the country and around the world can freely read and wonder at their wisdom.

Keith Donohue is communications director for the National Historical Publications and Records Commission at the National Archives.

This revolutionary new site was created through a partnership between the University of Virginia Press and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the grantmaking arm of the National Archives.

For more information:

- Watch: The Making of The Founders Online

- Learn more about the project's origins

Watch President Obama's final State of the Union address.

Read what the President is looking for in his next Supreme Court nominee.

Take a look at America's three newest national monuments.

U.S. Constitution.net

Founders’ vision of religious freedom, religious beliefs of the founding fathers.

The American founding era encompassed a vast spectrum of religious beliefs, reflecting the diversity of the population itself. Approximately 98% of Americans of European descent identified with Protestantism , predominantly adhering to the reformed theological tradition. This demographic shaped the religious landscape the Founding Fathers traversed.

Thomas Jefferson's beliefs straddled Enlightenment rationalism and deism. He advocated for a strict separation of church and state, yet he was deeply spiritual, rejecting organized religion. An Enlightenment rationalist, he saw reason as a guiding light planted by God, responsible for guiding human actions. Jefferson's commitment to religious freedom shone through his crafting of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom , ensuring that no man should suffer on account of his religious opinions.

James Madison championed religious freedom, opposing the imposition of any religious taxes in Virginia. His efforts culminated in the adoption of Jefferson's statute, reinforcing the vision that religious liberty covered all religious denominations.

Benjamin Franklin's approach to religion was more pragmatic. While he believed in a higher power and moral righteousness, Franklin was known for his skepticism about organized religion's dogma. His contributions to religious liberty focused on the broader philosophical underpinnings that allowed a multitude of beliefs to coexist peacefully.

John Witherspoon, a Presbyterian minister, emphasized virtue and morality grounded in Christianity as essential for the newly formed republic, acknowledging that religion played a crucial role in maintaining civic order and virtue.

Roger Sherman, another devout Christian, advocated for a government that allowed religious exercises but did not mandate them, demonstrating an understanding that personal faith should not infringe upon the liberties of others.

John Adams leaned towards Unitarianism. His letters often reflect a belief in a moral divine order, yet he resisted the idea of a state-endorsed church, seeing the danger in intertwining religious authority with governmental power.

Thomas Paine represented the far end of the spectrum. His pamphlet "Common Sense" galvanized support for independence while critiquing institutionalized religion heavily. Unlike many founders, Paine was openly skeptical of Christianity, advocating for a deistic approach that celebrated reason over religious dogma.

The Founding Fathers' vision ranged from Jefferson's enlightened deism to Witherspoon's orthodox Christianity. This variety ensured a balanced approach to religious freedom, enshrined in the First Amendment, aiming for a secular state allowing for varied religious practice, free from religious tyranny.

Influence of the Bible on the Founding Fathers

The Bible's influence on the Founding Fathers is evident in their understanding of human nature. They were aware of mankind's fallibility and moral imperfections, a worldview endorsed by biblical teachings, particularly those in Genesis. The notion that man is inherently flawed led the Founders to design a system of government with checks and balances to prevent the concentration and abuse of power, reflecting the biblical wisdom gleaned from texts such as Jeremiah 17:9 and Romans 3:23 . 1,2

Regarding social order and the legitimacy of authority, the Bible served as a cornerstone. Exodus 18:21 , where Jethro advises Moses to select capable men who fear God, are trustworthy, and hate dishonest gain to help govern Israel, influenced the Founders in their conceptualization of a righteous and accountable government led by virtuous individuals. 3 They perceived that the moral character of leaders was paramount, echoing the sentiment in Proverbs 29:2 . 4

In seeking to justify resistance against tyranny, the Founders turned to biblical precedents, most notably in the Old Testament accounts. These stories reinforced their belief that it was both a right and a duty to resist tyrannical authority, thus informing the revolutionary spirit that characterized the American struggle for independence.

The principle of liberty was another area richly informed by the Bible. The Founders frequently cited Galatians 5:1 , using it to underscore the value of personal and communal freedom. 5 Though this text fundamentally speaks to spiritual liberty, the revolutionary approach adopted it to highlight the broader human yearning for freedom from oppression.

As these biblical principles were interwoven into the Constitution, they also found expression in practical governance:

- The Bible's call for justice and equity under the law is mirrored in the equal protection and due process clauses.

- The Judeo-Christian ethic, promoting societal moral standards and personal responsibility, provided a foundation for the rule of law as envisioned by the Founders.

The Bible was a vital text that informed the Founding Fathers' public and political lives. Its teachings on human nature, social order, and righteous leadership influenced their construction of the American constitutional republic. They envisaged a system where a virtuous citizenry, guided by reason and moral integrity, could sustain a free and just society. The result is a legacy where religious freedom flourishes within a secular government framework—a testament to the foresight of the Founding Fathers and the timeless wisdom they drew from biblical scripture.

The First Amendment and Religious Freedom

The inclusion of religious freedom in the First Amendment was a profound philosophical and political statement, reflecting the lived experiences and aspirations of the American colonists. Many colonists had fled their homelands to escape the tyrannical reach of state-endorsed churches, seeking a place where they could worship freely without fear of oppression.

These personal experiences deeply influenced the Founding Fathers' views on religious liberty:

- Thomas Jefferson witnessed the harsh persecution of dissenters in Virginia, particularly Baptists who were imprisoned for preaching without a license. This sparked his commitment to safeguarding religious freedom and his creation of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom .

- James Madison understood the dangers of a state intertwined with religious authority, believing that true religious faith could only flourish without government interference.

The philosophical and political theories of the Enlightenment also played a crucial role in shaping the Founders' views on religious liberty. Thinkers like John Locke argued that belief could not be coerced and that individuals had an inherent right to religious liberty—a view that resonated with the Founding Fathers. 6

The Founders recognized that for a society to truly respect personal liberty and foster civic virtue, it must allow individuals the freedom to believe and worship as they choose. The separation of church and state was seen as a means of ensuring that faith could thrive without the corrupting influences of political power.

Politically, the Founders were wary of the religious conflicts that had plagued Europe for centuries. Their aim was to prevent such turmoil in the nascent United States by ensuring that government neither mandated nor restricted religious practices.

The varied religious composition of the American colonies necessitated an approach that could accommodate a broad spectrum of beliefs. The First Amendment, with its establishment clause and free exercise clause , sought to provide this accommodation:

- By prohibiting the establishment of a national religion, the Founders ensured that no single denomination could claim governmental endorsement.

- Simultaneously, by protecting the free exercise of religion, they guaranteed that all individuals could practice their faith without fear of government reprisal.

The First Amendment embodied a blend of philosophical ideals and practical considerations. It was the product of Enlightenment rationalism, historical experiences of persecution, and a pragmatic recognition of the pluralistic nature of American society. The result was a constitutional framework that allowed for a vibrant diversity of religious expression while maintaining a government that was neutral in matters of faith.

Thus, the inclusion of religious freedom in the First Amendment was a cornerstone of the Founders' vision for a nation where liberty and justice could prevail for all, uninhibited by the specter of religious domination or discrimination. It ensured that Americans could build a society rooted in moral integrity and personal liberty, reflecting the profound insights and foresight of the enlightened minds that crafted this unparalleled document.

The Wall of Separation Between Church and State

The phrase "wall of separation between church and state," coined by Thomas Jefferson, has become a cornerstone in understanding the American constitutional approach to church-state relations. Jefferson's intent was crystallized in his 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, where he sought to assure the Baptists that their religious freedoms would be protected from governmental interference. He asserted that the First Amendment built "a wall of separation between Church & State," reinforcing his commitment to religious liberty as outlined in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

Jefferson's metaphor stemmed from his Enlightenment ideals and rationalist principles, believing that reason should guide human governance—including religious matters. His advocacy for a clear delineation between the roles of religion and government was shaped by his observations of the oppressive religious practices in Europe and the colonial experiences in America. He contended that religious belief should be a matter of personal conviction, free from state coercion.

Initially, Jefferson's notion was closely aligned with the efforts to ensure that no single religious denomination could wield governmental power, thus maintaining a pluralistic and equitable civil society. However, his phrase has been subject to various interpretations since its inception. Scholars and jurists have debated whether Jefferson intended an absolute separation where no acknowledgment or accommodation of religion in public life would be permissible, or merely a prohibition against the establishment of a state-sponsored religion.

Supreme Court interpretations have varied over the decades. In the landmark case of Reynolds v. United States (1879), the Court referenced Jefferson's phrase in defining the scope of the First Amendment. The opinion affirmed that laws could not interfere with religious belief but could regulate practices that were subversive to good order. This case set a precedent, framing the wall as a barrier to legislative imposition on religious belief while allowing for legal constraints on religious practices that conflicted with civil obligations. 1

Significant shifts occurred with the mid-20th-century jurisprudence. In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court emphasized a strict interpretation, asserting that no aid or preferment should be granted to religious institutions by the state, although it upheld the state's provision of transportation subsidies to parochial schools. This case underscored the interpretation that the government must remain neutral in religious matters, avoiding any entanglement which might suggest state endorsement of religion.

Conversely, some critics argue that an overly rigid interpretation of the "wall" inhibits reasonable and historical intersections of faith and governance. Historical practices such as legislative prayers, the employment of chaplains, and public religious expressions by government officials have been seen by some as congruent with the Founders' intent to allow public religious practices within a framework that avoids preferential treatment. 2

The debate over the phrase "wall of separation" persists, influencing contemporary discussions on religious displays on public property, religious exemptions from generally applicable laws, and the extent of permissible religious expression within public institutions. Jefferson's vision was fundamentally about preventing an official state religion and ensuring that government could not coerce individuals in matters of faith, thus fostering a society where religious liberty could thrive.

Therefore, while Jefferson's "wall of separation" is a defining concept, its practical application has evolved, demonstrating the dynamic interplay between maintaining religious freedom and accommodating religious diversity within a constitutional republic.

Modern Interpretations and Controversies

In recent times, the discourse surrounding religious freedom and the separation of church and state has persisted as a dynamic and often contentious area of American constitutional law. Modern interpretations of Jefferson's "wall of separation" continue to inform contemporary legal challenges and societal debates, illustrating the evolving nuances of the Founding Fathers' vision in today's diverse religious landscape.

One of the significant modern studies contributing to this ongoing discussion is the Center for Religion, Culture and Democracy's annual Religious Liberty in the States Index. This comprehensive index analyzes state laws and regulations across fourteen categories, examining the impact on both individuals and religious organizations. The findings from the latest report reveal an intriguing spectrum of religious freedom protections across the United States, highlighting the intricate balance states attempt to achieve between safeguarding religious liberties and adhering to secular principles.

For example, Illinois , a state with a predominantly liberal political climate, ranks highest in religious freedom protections. This stands in contrast to West Virginia , a state with a more conservative orientation, ranking lowest. Such results suggest that safeguarding religious freedom transcends political boundaries and reflects a broader approach.

Discussions within the judicial and legislative frameworks continue to shape the understanding and application of religious freedom. Landmark cases such as Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. and Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission underscore the ongoing legal balancing act between religious liberties and other fundamental rights, such as non-discrimination. These cases reflect the judiciary's approach to ensuring that religious freedom does not impinge upon the rights and freedoms of others, maintaining the delicate equilibrium envisioned by the Founding Fathers. 3

As these legal challenges unfold, it becomes evident that religious freedom in the United States embraces a bipartisan appeal. Jonathan Den Hertog, a professor at Samford University, underscores that this fundamental liberty necessitates bipartisan support to remain a vital force in American public life. His insights remind us that the protection and preservation of religious freedoms must transcend political affiliations.

Yet, despite the non-partisan ideal, certain aspects of religious freedom continue to spark debate. Issues such as exemptions related to marriage and healthcare often reveal ideological divides. While some argue for broader religious accommodations, others raise concerns about potential infringements upon civil rights and equality. The intricacy of these debates mirrors the diverse religious and societal fabric of the nation, necessitating a legal and political approach that respects both religious convictions and fundamental rights.

Modern studies also reflect the significant role of religious liberty in protecting minority faiths. Asma T. Uddin, a legal scholar, highlights how these protections are vital for communities like American Muslims. Provisions for religious school absences, religious ceremonial life, and opt-out provisions for public school curricula on sexual orientation and gender identity are crucial in ensuring that religious minorities can practice their faith freely within a secular framework. 4

The Religious Liberty in the States Index employs quantitative measures to assess the impact of laws on religious freedoms. This empirical approach provides policymakers and legislators with valuable insights to reform and enhance religious freedom protections in their respective states. As the Center for Religion, Culture and Democracy plans to expand its index and possibly undertake a similar project in Europe, it underscores the transatlantic relevance of religious freedom debates.

In conclusion, the modern interpretation of religious freedom in the United States remains a dynamic and multifaceted endeavor. The Founding Fathers' vision, encapsulated in the First Amendment, continues to guide contemporary legal and societal debates, ensuring that religious liberty thrives within a constitutional republic.

The Founding Fathers' commitment to religious freedom, enshrined in the First Amendment, remains a cornerstone of American values. Their vision of a society where liberty and justice prevail, free from religious tyranny, continues to guide contemporary discussions on church-state relations. This legacy underscores the importance of maintaining a constitutional framework that respects individual conscience while fostering a diverse and harmonious society.

Historians Reflect on Founding Fathers and America Today

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/historians-reflect-on-founding-fathers-and-america-today

Ray Suarez speaks with three historians, Richard Brookhiser, Ron Chernow and Jan Lewis, about what the founding fathers might have thought of America today.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

RAY SUAREZ:

What would our founding fathers think about our country today? On America's 228th birthday we get some insight from three people who've studied the founders. Richard Brookhiser's latest book is "Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution." He's a senior editor at the National Review. He's also written biographies of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and the Adamses. Ron Chernow is a prize-winning biographer; his newest book is on Alexander Hamilton. And Jan Lewis is chairman of the Department of History at Rutgers University. She's a specialist in colonial and early national history. She's written extensively about Thomas Jefferson.

Well, guests, recently we've been arguing about habeas corpus, had some great debates about the limits of executive power, and this constantly toing and froing about powers of the states versus the federal government. It's still in 2004 a world the founders would recognize, Ron Chernow?

RON CHERNOW:

Well, I think the founders would be very pleased by the power and the prosperity of the country. I think that they would be somewhat dismayed by the nature of political discourse. These were men who had rich political visions that they passionately and extensively argued. I think that they would be dismayed by a world of politicians who are governed by pollsters and focus groups who express themselves through 60-second ads, rather than through speeches and papers and pamphlets, and these were men who didn't have dispositions, but they had philosophies.

Well, Professor Lewis, Ron Chernow saying that they wouldn't be too impressed with the discourse, it got pretty rough in the 1790s, didn't it?

Oh, it sure did, and I think actually they might find politics today milder than it was in their time. We have to remember that during Jefferson's administration Vice President Aaron Burr got into a duel and actually killed the former secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton. As bad as things have gotten with Dick Cheney he's only used the "F" curse; he hasn't actually gone out and shot Richard Rubin.

Richard Brookhiser, weigh in on the politics of today and how you think it would look to — to the founders.

RICHARD BROOKHISER:

Well, I agree with Professor Lewis. In a lot of ways politics is more polite and more moderate than it was. The man who wrote the Constitution, Gouverneur Morris, 25 years after he wrote it he wanted the country broken up. You know, he said in order to form a more perfect union, then he decided the union wasn't so perfect, so his attitude was, the hell with it, let's split the whole thing up and start all over, which is a pretty radical position.

I think the founders would find our politicians and our voters pretty dumb. I mean, we have two Yale men running for president now, but I don't think they can translate Greek into Latin, and back, which, you know, anyone who went to a college in those days was required to be able to do. And, you know, I'm not just laughing at George W. Bush and John Kerry. I think they would have this disdainful attitude towards we, the voters, as well.

Well, Alexander Hamilton went, I guess to the precursor of Columbia University, rather than to Yale. Did he get the country inevitably of all the founders that he was looking for?

Oh, I think so. I mean, it was Hamilton I think who had a vision of an America that would be dominated not only by agriculture but by manufacturing stock exchanges, banks, corporations, large cities, a lot of things that were anathema to the Jeffersonian version. I think that he was very prophetic in terms of the shape of power, not only that the federal government would become so powerful but that even within the federal government that the executive branch would, as it were, be the engine of government.

But I think it was Hamilton who first saw the president, for instance, would be the principal actor in the American political drama at a time when Jefferson and Madison, who saw the House as much closer to the people, as the perfect populist institution, were hoping that the Congress, particularly the House of Representatives, would have a larger role. So I think that if Hamilton came back today, he would have more of a sense of vindication in many ways than Thomas Jefferson.

Well, Professor Lewis, is this a zero sum gain? If Hamilton got his America, does that mean Jefferson didn't get his?

Oh, I don't know. If Jefferson is still the favorite founding father and half a million people flock to Monticello every year and Jefferson's ideals — life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness — are still the ideals that govern this nation and to some extent have sway throughout much of the world.

Well, I think one thing that would please them all would be the fact that there were no more slaves, and this was an institution that they lived among; many of them owned slaves. I think it's fair to say that all of the founding fathers thought that slavery was bad and hoped that it would eventually pass away. Now some of them were more practical in pursuit of this goal than others. Alexander Hamilton and John Jay helped found a manumission society in New York to get rid of slavery in New York state, because it wasn't just a Southern thing. New York had a lot of slaves, but I think in fairness to all of them, including the great slave owners, like the Virginians, they would be pleased to see that this institution had disappeared.

Pleased to see but at the same time weren't some of them also marked by their unwillingness to step forward on the issue and sometimes their willingness to let others step forward on it?

Well, they had mixed records. You know, George Washington grew up in Virginia, a slave-holding culture. He owned hundreds of slaves, but in his will he freed all his own slaves, and he knew that his will was going to be a public document and therefore he was making a statement by doing this. For some of the other founders who lived in New England or Pennsylvania it was perhaps an easier call because those states got rid of their slavery, you know, ahead of even New York.

Jefferson is a complicated one here. He's frustrating to us, maddening. He knew that slavery was wrong, yet, he never worked up the courage to free all of his slaves, nor to compel his country to face the issue. He was afraid, he said in his notes on the state of Virginia, that were slaves freed, they would rise — justly rise up against their former masters and kill them. Therefore, he said, well, we'll just have to colonize slaves somewhere else, Africa, the Caribbean, in the far West somewhere, anywhere far away from the white folks. It turned out that he was actually wrong.

After the Civil War — and it did take a Civil War to terminate slavery — after the Civil War, black people didn't rise up and exact vengeance on their former masters. To the contrary, it was white people who oppressed blacks and who lynched them. Jefferson happily was wrong. Unhappily, he didn't do much — didn't do much of anything to bring an end to the institution of slavery.

Ron Chernow, you want to —

People would be surprised at the extent to which the slavery issue permeates the early years of the republic. You know, we're all taught in school, right, that the Constitutional Convention the major split was between the large states and the small states and the compromise was worked out that the large states would get proportional representation; small states would get the equal vote in the Senate.

In fact, Madison himself said the major split at the Constitutional Convention was not between the large states and the small states but between the North and South because slavery was really a most divisive issue, and the early year of the republic were haunted by fears of disunion, haunted by fears that there would be breakaway confederacies, civil war, foreign intrigue, foreign invasion, and so the thing that was given a premium above all else was unity, so that the most divisive issue, the one thing that could wreck the whole experiment, was slavery, and so Rick's right. I mean, the reactions of different founders is radically different. You have Hamilton, J. Adams, outspoken abolitionists; Washington kind a little bit more in-between; Jefferson opposed to slavery in theory by preferring to defer any action to a future generation, but there is a kind of collective decision that this is one issue that is too hot to handle.