- Majors & Programs

- Admissions & Aid

- Sacred Heart Life

- Commencement

- News & Events

- Colleges & Schools

DIRECTORIES

- Dingle Campus

- Online Programs

RESOURCES FOR

- Undergraduate Admitted Students

- Current Students

- International Students

- Accessibility

ACCESSIBILITY

The Pioneer Pursuit

8 Important Differences Between Undergraduate and Graduate School

May 28, 2021.

Written by SHU Graduate Admissions Team

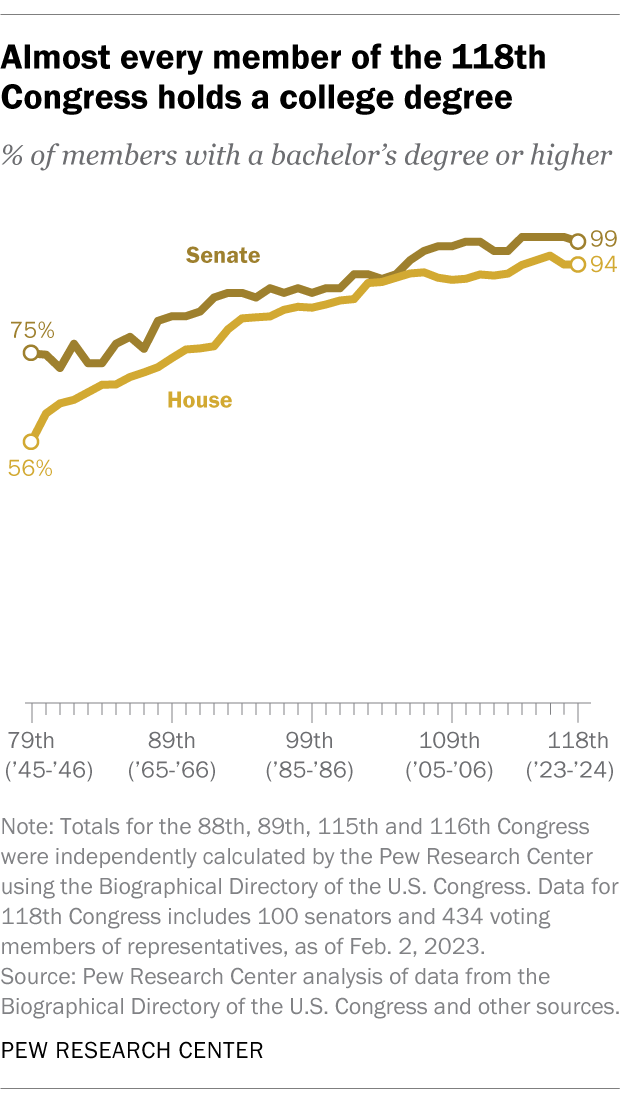

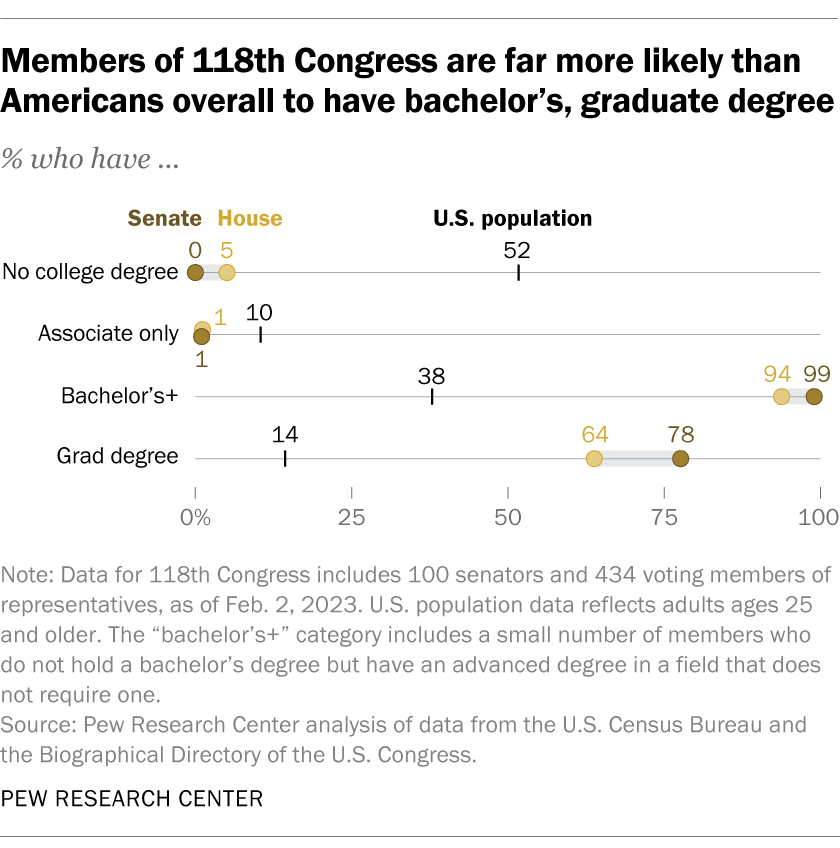

Over the last two decades, universities across the nation have seen impressive growth in their master’s programs. Since 2000, the rate of growth of earned master’s degrees (60 percent) has outpaced bachelor’s, doctoral, and professional programs. Certain fields of study, primarily business, education, and health professions , have experienced the most growth. What’s more, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment in occupations requiring a master’s degree will increase by almost 17 percent by 2026.

Naturally, important questions arise when considering whether to join the growing ranks of those obtaining graduate degrees. Often prospective grad students wonder — is a master’s worth it? What’s the real difference between an undergraduate vs. graduate degree? How do you choose which program and degree are best for you? To begin answering these questions, explore these eight important differences between a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree.

1. Highly specific coursework

During an undergraduate program, students take several foundational and general subject courses, some of which are unrelated to their major. Graduate school coursework, on the other hand, is highly specific.

The goal of graduate school is to help you become an expert in your chosen field of study. Graduate school empowers you to become the master of your own education. A master’s program supports a higher level of individualized learning and offers greater professor support to serve your unique goals. You’ll develop self-awareness and self-confidence as you mature as an expert in your field.

2. Flexibility within the program

Switching majors or even schools one to two years into an undergraduate program is very doable because of the universality of the degree, similarities between programs across institutions, and time you have to complete the degree. In graduate school, however, it is not as easy to make a change to a new program or school. While not impossible, most master’s programs take one to two years to complete — so if you think you want to make a change, initiating it during your first semester is your best bet for retaining all your credit hours.

3. Admissions Requirements

Undergraduate programs have a relatively simple admissions process, and commonly include submitting your high school grades, SAT or ACT scores, and providing a few writing samples and letters of recommendation. Graduate school applications often require these items and more. Other common admission requirements for graduate school include proof of a completed bachelor’s degree, GRE/GMAT scores, a minimum undergraduate GPA, a statement of purpose, a research proposal, and an interview with the school. Certain graduate programs will have prerequisite course requirements, so be sure to inquire about your specific program of interest. Also, if you are an international student, check with the college or university to see if you need to provide additional documentation.

4. Course load

Undergraduate students juggle 5-6 courses per semester, while graduate students usually take only 3 advanced level courses. These courses involve much more reading and research than undergraduate classes and typically have fewer assignments. Because there are fewer projects, papers, and exams for graduate-level courses, each item is worth more and is expected to be a demonstration of your expertise in the subject.

5. Community

Undergraduate classes are often large lectures with hundreds of students, whereas graduate classes are much smaller (usually under 20 students). In grad school, you will become well acquainted with the other students and the professor. After a rigorous application process, you can be sure of the caliber of students that surround you. With everyone’s diverse backgrounds, work, and life experiences, you will learn from and challenge each other. Additionally, you will learn to work with your professors as opposed to simply completing assignments for their classes.

6. Research experience

Research experience is valuable in almost every line of work. It teaches you to plan, think critically and logically, seek out answers to your questions, and incorporate those findings into your work. Research in an undergraduate program is typically comprised of a few research projects or papers, whereas in graduate school, research makes up the vast majority of learning in the classes. Depending on your program and area of interest, graduate students generally have access to advanced tools and systems that they can use for research purposes. You’ll have the opportunity to work closely with professors on their research projects, learning from them and discovering your own areas of interest.

7. Professional marketability

While an undergraduate degree allows you to apply for entry level jobs, a graduate degree expands your job market and increases your favorability in the eyes of potential employers. In a competitive market, you’ll need an edge over other job applicants. Graduate school gives you a larger network and better connections. When career advancement opportunities, promotions, and leadership positions open up, your graduate degree will help you stand out as the best candidate.

8. Leadership development

An undergraduate degree offers you a broad knowledge base, but a graduate degree sets you up to be a leader in your field. A 2016 Gallup poll found that a shocking 82 percent of managers aren’t very good at leading people , even while corporations spend billions to develop them. This means there is an eminent need for qualified leaders in today’s workforce. Through the rigors of graduate school, you will gain many of the necessary skills and character traits companies look for in their leaders. During your degree program, you’ll work as part of many teams and develop critical thinking, problem solving, time management, perseverance, commitment, and communication skills — all qualities that hiring managers look for in the leaders they need.

Choosing the right Graduate school and degree Program

In order to choose the school and degree that are right for you, you should begin by identifying your interests, your ideal career, and your needs (part/full time, geographic location, price range, etc.). After determining these, investigate various programs and look into their requirements, curriculum, research opportunities, and graduation outcomes. It is also a good idea to talk with admissions professionals, professors, and, if possible, the students in the program.

If offered, you should take advantage of virtual events or in-person offerings on campus such as information sessions and open houses. Even if you plan to earn your degree online, visiting the campus and having a face-to-face conversation with admissions professionals, faculty, students, and alumni of the program will give you the chance to have your questions answered and help you envision what it would be like to attend.

At Sacred Heart University, we host an open house event each semester . It’s our hope that you will come and visit us, ask your questions, and allow us to help you explore your grad school possibilities. If you would like more information about one of our upcoming events, please reach out to us and we’ll be in touch soon!

If you'd like a more in-depth look at the differences between graduate and undergraduate study, we invite you to explore our comprehensive digital resource which covers admissions requirements, salary increase expectations, and much more!

About the Author

We are the graduate admissions team at Sacred Heart University. We aspire to create a welcoming and supportive environment for students looking to continue their education while empowering them in mind, body and spirit. We hope you find our resources helpful and informative as you explore and pursue a graduate degree at Sacred Heart!

5 Most Recent Posts

Subscribe to the blog.

Topics: Admissions , Grad School Resources

The Differences Between Graduate and Undergraduate Study: Everything You Need to Know

Recommended for you

October 26, 2022

Is a grad school visit worth it.

With classes, work and home life vying for center stage in your schedule, you’re probably wondering if visiting the graduate schools you’re considerin...

August 22, 2022

Getting a master’s degree in a different field than your bachelor’s: 10 degrees to consider.

For many people, a master’s or other graduate degree is a natural extension of their undergraduate studies — it may even be required to get a job in t...

August 17, 2022

Tips for going to grad school now.

Many elements of life have begun to feel relatively “normal” again as more people get vaccinated, but the pandemic isn’t over yet. Americans may be ba...

OUR LOCATION

5151 Park Avenue Fairfield, CT 06825

203-371-7999

GLOBAL CAMPUSES

- Careers at SHU

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Virtual Tour

- Privacy Statement

© 2021 SACRED HEART UNIVERSITY

Research and Writing at Graduate Level

Any program leading to the Master of Arts fosters the student’s transition into a profession. Students learn how to discuss ideas in a particular discipline as professionals among professionals. To attain this goal, graduate students routinely engage in research and writing where correct documentation of sources signifies much more than the avoidance of plagiarism. Research and writing about scholarly discoveries signal the graduate student’s membership in a professional community.

Thus research papers written for graduate courses will differ from those written for undergraduate courses. The graduate student’s research paper will sustain deeper analysis of a topic at greater length and with narrower focus than the undergraduate paper. Graduate research papers will employ a significant scope of sources that are current, authoritative, and recognized within a particular area of study. Additionally, the graduate research paper demonstrates the student’s ability to identify appropriate topics related to course material and to exercise independence in both research and writing.

Graduate-level papers will also demonstrate the student’s ability to document all sources accurately and to edit carefully for standard American English. Students should refer to The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers , 8th Edition (ISBN 978-1-60329-262-7), if they have questions about documentation, though some courses may ask students to follow the Chicago Manual of Style or the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association .

To prepare students for the level of research and writing required in graduate courses, professors incorporate into their classes instruction in bibliography and methodology appropriate to course content. Professors will assist students to access and learn how to access and evaluate scholarly materials. Professors may further provide rubrics or specific requirements about the nature and originality of the research and writing expected in fulfillment of a particular assignment.

For information on academic misconduct and plagiarism, see the Honor Code section of the Graduate Student Handbook.

Search form

Research and innovation menu, research and innovation, defining undergraduate research.

As a faculty member, you know what research is. You also recognize and respect that what counts as research is unique to each discipline. This perspective – a working knowledge of research coupled with a scholarly regard for research and creative scholarship in other disciplines – is an essential starting point for understanding undergraduate research and creative scholarship.

Undergraduate students come into higher education at various levels of knowledge, skills, and abilities. It is likely that many of the students have not been exposed to rigorous academic research, possess vague ideas of what faculty research looks like, and may be intimidated by the concept. However, they do know that research is a vital part of a university and they do appreciate that faculty who are productive researchers translate to the university and their discipline having prestige. And more importantly, they are at a stage in their life when they are most eager to learn and explore their interests, and are therefore ripe to discover the joys of inquiry and discovery.

This setting illuminates the difficulty with defining undergraduate research. It is not simply undergraduate students conducting research in the same arenas as faculty, using the same research methods and techniques, and working towards contributing original knowledge. While that is an important part, a more accurate definition of research includes the learning, education, and developmental components that students go through as they learn about and experience academic research. To further conceptualize this understanding, think back to your own undergraduate education and your first encounter with research.

- How would you describe that experience?

- What were some of they key moments and characteristics?

- Who were the key players?

- Why were you successful?

- How did you overcome challenges?

Contemplating and answering these questions is crucial to understanding undergraduate research and creative scholarship. All of these attributes, factors, and forces are what defines undergraduate research and creative scholarship. It isn’t simply a project, a report, publication, or presentation. It is the experience — the learning, the intellectual growth and development, the acquisition of skills, the maturation of thought and self, and the fostering of an inquiring and critical mind.

It is from this perspective that the difference between research conducted at the undergraduate level and that which is conducted at the graduate level and beyond is revealed. It is the pursuit of not only the answers to the research question, but also the pursuit of the positive outcomes associated with student learning and growth. It involves maintaining the ideals of rigorous and ethical research while simultaneously developing students as scholars.

Therefore, how we think about undergraduate research and creative scholarship is more important than how we define it. Taking this approach allows us to use a broad definition of research that results in increased synergy between teaching and research (Colbeck, 1998; Healey & Jenkins, 2009; Jenkins & Healey, 2005; Zamorski, 2002), which can lead to beneficial educational activities for undergraduate students.

Next – The Teaching-Research Nexus

Suggested Readings

- Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship

- Colbeck, C. (1998). Merging in a seamless blend. The Journal of Higher Education. 69(6), 647-671.

- Healey, M. & Jenkins, A. (2009). D eveloping undergraduate research and inquiry. Research report to the Higher Education Academy.

- Jenkins, A. and Healey, M. (2005). Institutional strategies to link teaching and research. York: The Higher Education Academy.

- Zamorski, B. (2002). Research-led teaching and learning in higher education: a case, Teaching in Higher Education. 7(4), 411–427.

Mentoring Undergraduate Research Directory

- Online Degrees

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Transferring Credit

- The Franklin Experience

Request Information

We're sorry.

There was an unexpected error with the form (your web browser was unable to retrieve some required data from our servers). This kind of error may occur if you have temporarily lost your internet connection. If you're able to verify that your internet connection is stable and the error persists, the Franklin University Help Desk is available to assist you at [email protected] , 614.947.6682 (local), or 1.866.435.7006 (toll free).

Just a moment while we process your submission.

Popular Posts

Key Differences Between Undergraduate and Graduate School

Going to a graduate school is a different experience than getting your undergraduate degree. But, how different?

As you consider your options for earning a master’s degree , it will help you to know what is expected of you and how you can prepare for success. It’s important to know those expectations going in, because preparing yourself is a key step toward success in a master’s program.

Below is a list of the most palpable differences that make graduate school feel different than undergraduate.

You’ll Be Surrounded by Like-minded People

The average age for a graduate student is 33. Most students work at least part-time.

According to Kody Kuehnl, Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Technology at Franklin University , “You’ll be attending graduate-level courses alongside of professionals who are in your chosen field of study. Because you’re with many educated, experienced, like-minded people, just interacting with other students can be a way to build your network and gain important career connections.”

In traditional undergraduate courses, students are typically younger and don't have professional work experience or connections. At graduate school, you’ll have more experienced peers. Be ready to plug into that built-in network of professionals at the student level.

Rather than the common undergraduate tactic of grade competition—or grading on a curve, which pits student against student—graduate work is considered on its own merit. You’ll find that your fellow students are often ready with insights, ideas, and support to help you do even better.

Classes Are Much More Interactive

As mentioned above, your student peers in graduate school are actually an important part of the process. Faculty members at a graduate level will regularly encourage active participation and discussion. Undergraduate professors typically provide information and direction, whereas graduate faculty might focus more on facilitating debates and discussions.

At a graduate level, classroom time is shared. Professors will engage you, and you’ll be expected to contribute to a conversational, collaborative class experience. The student should always come to class fully prepared, having read materials and sources prior to the class. As an undergraduate, class discussion may be less focused and more spontaneous; however in graduate school, discussions are often laser focused and require preparation. The ideas you bring with you will enhance not only your learning and understanding, but also your peers’.

What matters most when choosing a master’s program? Compare features, benefits and cost to find the right school for you.

You’ll have to think on a different level.

In undergraduate work, the focus is on learning information; it’s about memorization and understanding concepts. Graduate school is different.

“You move from theory to real-world applications. Whereas undergraduate is about gaining a broad understanding of a topic, graduate school is a much deeper dive into the intricacies of the field. The thinking is different with more of a focus on how you construct your arguments, what your sources of information are, and how you apply it all as you tackle a real problem.” —Kody Kuehnl

When you reach a graduate level of courses, the focus switches from learning information to applying it. More of your time will be dedicated to seeing one topic from many different angles and then finding your own point of view about it.

More Time Spent Researching and Writing

A 4-year undergraduate degree may take longer than an 18-month-long master’s degree, but the master’s is more likely to feel like a marathon.

You’ll be reading and researching a great deal. Your study habits will need to be tighter and smarter. You’ll have to be ready to write a lot more. According to Kuehnl, “The time you spend studying is much more active in the graduate world. Rather than memorizing, you’re actually training your mind to use information in a new way.”

Be ready for the additional effort.

There’s No Fluff

At a graduate level, the content is laser-focused on specific career-building outcomes and skill sets. Unlike undergraduate studies, there is not a broad range of content to create a well-rounded person. Your master’s degree is designed to do just that: build mastery in one area of content.

Most of what you’ll do is based on what you want to do. When you’re done, you’ll have a depth of understanding that can immediately be put to use in the working world.

There’s Less Structure and More Freedom

In a bachelor’s program, professors and lecturers typically give you detailed reading lists, organized notes, timelines, project check-ins, and plenty of detailed directions so you’ll know what’s expected of you. In a master’s program, you’ll have far more freedom—and you’ll need to learn how to manage it!

Remember that freedom equals responsibility. Without someone constantly prompting and reminding, you will need to manage your own deadlines, both large and small. Be sure to stay on top of your reading and research because it can be hard to recover if you get behind.

Professors Treat You More Like Peers Than Students

As mentioned above, master’s degree students are expected to contribute during class time; this is a major component of how professors feel about you, talk with you, and treat you. Leave behind any idea that the professor teaches while you listen. Your professors hope for and plan for you to be a positive contributor who is both learning and sharing at the same time.

Some universities elevate the importance of this concept. For example, Franklin University calls it “360-degree learning,” where you are a part of a network of professionals at both the faculty and peer level.

It Will Be Hard(er)

Graduate work is no walk in the park.

According to Kuehnl, “Some people considering graduate school will actually wonder if they’re ‘smart enough.’ But getting a master’s degree is not about being smart. A major factor in graduate degree success is what I call ‘grit.’ It’s about being determined, knowing what you want, having focus, being organized, and making the time and effort to do the work.”

You’ll Likely Earn More Money in Your Lifetime

According to the Social Security Administration, a graduate degree can be a financially rewarding asset. Their records suggest that a person with a graduate degrees typically earns $650,000 to $845,000 more in median lifetime earnings than a person with bachelor’s degree. Generally speaking, a graduate degree will open doors to opportunities (such as promotions and raises) that might not be available without it.

Vive La Difference

Undergraduate classwork is generally broad and designed to create well-rounded individuals who are ready to enter the working world. In traditional four-year schools, the student body is mostly comprised of young adults in a highly social environment with most students living on or near campus. The graduate coursework, environment, and mindset—even though they occur on some of the very same campuses—typically stand in contrast in order to meet the different educational goals.

So, yeah, grad school is different! And maybe you’ve never attempted any coursework that’s this intense. But with the right preparation, you can navigate those differences and powerfully position yourself for that next big step in your career and life.

Related Articles

Franklin University 201 S Grant Ave. Columbus , OH 43215

Local: (614) 797-4700 Toll Free: (877) 341-6300 [email protected]

Copyright 2024 Franklin University

Graduate Research vs. Undergraduate Research: Exploring the Differences

- by Matthew Morales

- October 31, 2023

Have you ever wondered how graduate research differs from undergraduate research? As you navigate the world of higher education, it’s important to understand the distinctions between these two levels of academic pursuit. Whether you’re a current undergraduate student considering your future options or a curious individual seeking knowledge, this blog post will shed light on the unique aspects of graduate research.

But before we dive into the specifics, let’s first clarify what it means to be a graduate. A graduate student is someone who has already completed a bachelor’s degree and has decided to pursue further studies in a specific field. With a master’s or doctoral degree in mind, they embark on a more advanced academic journey that involves in-depth research and specialized coursework.

Now that we’ve established the foundations, let’s uncover the key differences between graduate and undergraduate research. From the level of study to the depth of inquiry, this exploration will provide valuable insights into the distinct realms of academia at the graduate level. So, fasten your seatbelts and join us in unraveling the nuances of graduate research versus undergraduate research in 2023!

How is Graduate Research Different from Undergraduate Research

In the world of academia, research plays a crucial role in shaping new knowledge and pushing the boundaries of understanding. While both undergraduate and graduate students engage in research, there are significant differences between the two. Let’s delve into how graduate research differs from undergraduate research and what sets them apart.

Graduate research takes a deep dive into a specific field of study, whereas undergraduate research tends to cover a broader range of topics. Picture undergraduate research as a sampler platter at a restaurant, while graduate research is more like a five-course meal with each dish meticulously prepared and savored. Graduate students explore a single topic in great detail, allowing them to become experts in their field.

The Complexity:

While undergraduates may conduct research under the guidance of professors, graduate students are expected to work more independently and demonstrate critical thinking skills. Graduate research often involves complex methodologies , intricate data analysis , and the creation of new ideas or theories. It’s like going from solving a jigsaw puzzle with fifty pieces as an undergraduate to tackling a 1000-piece puzzle on your own as a graduate student.

Undergraduate research provides an introductory understanding of a subject, giving students a taste of what research entails. On the other hand, graduate research requires a more in-depth exploration, often leading to the creation of new knowledge. It’s like going from dipping your toe in a shallow stream as an undergraduate to diving headfirst into the deep ocean as a graduate student.

The Independence:

Undergraduate research is usually conducted in a structured environment with close supervision, whereas graduate research allows for greater independence. Graduate students are responsible for designing and executing their research projects, organizing their time efficiently, and making critical decisions. It’s like transitioning from driving a car under the watchful eye of an instructor as an undergraduate to confidently maneuvering the open road by yourself as a graduate student.

Graduate research demands a higher level of rigor compared to undergraduate research. The expectations for analysis and writing are elevated, and the standards are more exacting. Graduate students are pushed to question existing knowledge and contribute original ideas to the academic community. It’s like going from playing a friendly game of football with friends as an undergraduate to competing in a professional league as a graduate student.

The Contribution:

Undergraduate research often focuses on replicating existing studies or contributing incremental findings to the existing body of knowledge. In contrast, graduate research aims to make a substantial contribution to the field, whether by proposing new theories, discovering novel insights, or solving long-standing problems. It’s like going from being a supporting actor in a high school play as an undergraduate to headlining a Broadway production as a graduate student.

In summary, while undergraduate research provides a valuable introduction to the world of research, graduate research elevates the game to a whole new level. With its narrower focus, complex methodologies, and higher expectations, graduate research offers students an opportunity to make a lasting impact on their field. So, whether you’re an undergraduate considering your next steps or a graduate student embarking on your research journey, remember that while the transition may feel daunting, it’s also an exhilarating adventure filled with growth, discovery, and a few sleepless nights. Embrace the challenges, dive into the depths of knowledge, and let your research journey begin!

Graduate Research vs. Undergraduate research: FAQs

As you embark on your academic journey, you may find yourself wondering about the differences between graduate and undergraduate research. We’ve compiled a list of frequently asked questions to help shed some light on this topic. So, let’s dive in and get those burning questions answered!

What’s the Deal with Graduate Research

Q: what level is level 6.

A: Ah, level 6, the elusive grade that may leave you scratching your head. Well, fret not, my friend. Level 6 refers to the final year of an undergraduate degree program. It’s like reaching the top floor of a skyscraper, but still not quite reaching the penthouse.

Q: What is a Level 7 Bachelor Degree

A: A Level 7 Bachelor Degree is the shiny trophy you obtain after successfully completing an undergraduate program. It’s like earning a black belt in academia—the culmination of your hard work, sweat, and a fair amount of caffeine.

Graduating to the Next Level

Q: what makes you a graduate.

A: Ah, the moment when you spread your academic wings and officially become a graduate. To achieve this prestigious title, you must complete a Bachelor’s degree or its equivalent. It’s like leveling up in the game of life, where that hard-earned diploma becomes your +10 armor.

Q: What level is a Master’s degree

A: Welcome to the realm of higher education, my knowledge-hungry friend! A Master’s degree resides at level 7 on the academic ladder. It’s like discovering a hidden treasure chest full of specialized knowledge and increased career opportunities.

Q: What is a Level 7 Master’s

A: A Level 7 Master’s degree is the ultimate treasure you acquire after fulfilling the requirements of a challenging graduate program. It’s like obtaining a PhD in wizardry—okay, maybe not quite as magical, but close enough!

Different Strokes for Different Folks

Q: what’s the difference between an undergraduate and a graduate.

A: Ah, the eternal question! The main difference lies in the level of study. Undergraduate programs are like dipping your toes into the vast academic ocean. Graduate programs, on the other hand, plunge you headfirst into the deep waters, where you become a master of your chosen subject. It’s like upgrading from a learner swimmer to a synchronized diving champion!

Q: Do you need an undergraduate degree to get a graduate degree

A: Absolutely! An undergraduate degree is your ticket to the graduate realm. It’s like the mandatory training montage you see in movies—gotta start from the bottom before you can conquer the world. So grab your diploma and prepare to level up!

Graduate Research Revealed

Q: how is graduate research different from undergraduate research.

A: Oh, the wonders of research! Graduate research takes you on a whole new adventure compared to its undergraduate counterpart. It delves into uncharted territories, where you devise and execute original research projects to contribute new knowledge to your field. It’s like being Indiana Jones, minus the fedora and the threat of giant boulders.

The College Graduation Badge

Q: what degree makes you a college graduate.

A: An undergraduate degree, my friend! It’s like unlocking the achievement “Adventurer Extraordinaire” in the game of academia. Whether it’s a Bachelor of Arts or Science, that degree signifies your completion of a rigorous academic journey. Wear it with pride, for you have conquered the college world!

Voila! We’ve journeyed through a whirlwind of FAQs, unlocking the secrets of graduate research and its distinction from undergraduate research. Now armed with this knowledge, you can confidently navigate the academic landscape. Remember, education is a continuous quest for knowledge and growth, and you’re well on your way to becoming a master of your craft.

Until next time, happy researching!

*Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. Always consult with academic advisors or program coordinators for specific details regarding academic requirements and degree levels.

- academic pursuit

- current undergraduate student

- friendly game

- graduate research

- key differences

- specific field

- undergraduate research

Matthew Morales

Who earned the most on desperate housewives, how hard is the florida bar exam, you may also like, was howard hughes hells angels a success the untold story of a legendary film.

- by James Short

- October 5, 2023

Where are my purchased movies on Amazon?

- by Veronica Lopez

Who Does the CEO Answer to? Understanding the Role and Responsibilities of a CEO in 2023

- by Adam Davis

- October 23, 2023

The Relationship Between Language and Identity

- October 8, 2023

What is the difference between symmetry and asymmetry?

- by Lindsey Smith

- October 29, 2023

The Renaissance Across Europe: A Flourishing Era of Art, Science, and Ideas

- by Sandra Vargas

- October 9, 2023

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

The Difference Between Graduate and Undergraduate Degrees: 10 Things That Matter

Updated: October 13, 2023

Published: September 4, 2019

While both achieve the same goal, to prepare you for something new, and to push your academics further, graduate and undergraduate studies have some very important differences. Most notably, they both have very different possible outcomes, have varying levels of difficulty and commitment, and students’ reasoning for entering programs will vary quite a bit. Some of these are minor, but some matter quite a bit. Read on to learn all about degree levels and the difference between graduate and undergraduate studies.

Photo by Liam Anderson from Pexels

10 differences between graduate and undergraduate school that matter, 1. time commitment.

One of the first things you will realize as a grad student, is where did your life go? In undergraduate school, there is time to split between sports, social activities, volunteering, the list goes on. You’re always busy, but it might not always be school-related.

In graduate school, it can seem like you are always working on school-related tasks, but at least they will be interesting tasks! You’ve thought long and hard about going to graduate school, therefore it’s likely that you are studying something that you love, so the extra time commitment won’t seem so bad. Finally, graduate courses are much more research intense, so the work you do will inevitably take more time. But at least you are working towards something for you as well.

2. Professor-Student Relationship

The relationships between you and your professors are likely to be different than when you were an undergrad. As an undergraduate, you might find yourself in a class of over 300 students! Graduate courses are much more intimate, including online degrees.

Professors can also be more invested in their graduate students, especially if you are doing research together. Make that relationship work for you — learn all you can from your professors, and don’t forget to network towards the end of your studies. You never know who might be a great connection for a job.

3. Entrance Requirements

Requirements to get into graduate school are very different from that of undergraduate school. All undergraduate programs require a high school diploma or equivalent, and graduate programs require undergraduate degrees.

When it comes to standardized testing, requirements also change. To get into most undergraduate programs, especially four-year institutions, standardized tests are usually needed. For graduate school, the same might be true, but you will also find variance on which tests are required depending on the program. Some schools, such as University of the People , do not require entrance exams at all! See here what requirements you’d need in order to study at UoPeople.

Letters of recommendation will vary by school and program but are much more common for graduate school. Most public, four-year universities will not require recommendations for undergrad applications.

4. Post Grad Opportunities

Now here’s a difference between graduate and undergraduate that really matters: What you will do after. Both can lead to further education — undergrad degrees lead to graduate programs, and from there, you can complete post-graduate education such as a PhD.

School programs aside, the doors are much more open if you have completed a graduate degree. You are likely to get paid more with a graduate degree, and more management and upper level positions will be open to you, compared to applicants with undergraduate education.

5. Research

Graduate school is all about research. And while it is still possible to find research opportunities in undergrad, they are seen more as side projects or extracurriculars, instead of a culmination of your graduate education.

In your graduate studies, you will also have opportunities to research something that really matters to you, whereas in undergrad, you might have less of a say in research content.

6. Course Content

Course content as well as course structure is different in graduate school. Content and material is likely to be more challenging in graduate courses. You will also be expected to produce more materials such as papers, presentations, projects, and discussions during your graduate courses when compared to undergraduate courses that may rely on textbooks and passive lectures.

7. Evaluation

How you are graded will depend on programs and schools regardless of graduate or undergraduate status, but there are still some important differences between the two. First of all, when it comes to curving grades, or adjusting grades based on the class’ performance, undergraduate courses are much more likely to implement it. Here’s a little known fact — you can’t graduate with honors in graduate school!

8. Change of Majors

In your undergraduate studies, a change of majors requires little more than a trip and a form signature from an academic counselor. It might mean taking a few extra classes than anticipated, but it is still relatively easy to. In graduate school, however, changing majors or study tracks is extremely difficult because you are admitted into your program as part of the application process.

9. Older & Wiser?

Graduate students already know the ropes. They have learned their best study habits, the subjects they do well on, and the ones they may need extra help in, compared to undergraduate students, who may need some adjustment period to get used to higher education.

Graduate students might, however, also have spent considerable time away from school and may need extra help getting back in the mindset of studying, while undergrad students often come straight from high school and are ready to learn.

10. Interactive Classes

Undergrad classes might be all about reviewing materials, turning in assignments and taking exams. This isn’t always the case, but it is much more likely when compared to graduate school, where classes might have more discussions, require more participation and project-based assignments.

The Undergraduate vs Graduate Student

Photo by Anastasiya Gepp from Pexels

Undergrads are usually younger and full of energy. They are likely using a degree to find out what they want to do, take the next step in life, and have a fun social atmosphere. Graduate students have a different outlook. Some will have more work experience, and all have more school experience. Grad students may already have established their lives, families, and social groups and are more looking to school for just academics.

How Hard is Graduate School Compared to Undergraduate?

It’s harder! We can’t lie to you — graduate school is another ball game when it comes to academics. There is much more of an expectation to use your mind to make inferences and intelligent contributions to your work, compared to recall and memory exercises in undergrad. Graduate school requires much more applied skills and knowledge, and be prepared for a larger time commitment for graduate courses.

Admissions requirements can be harder as well for graduate school. While you might not be required to take a standardized test, if you do, the GMAT and the GRE are much more challenging than undergrad entrance exams.

You may also be asked to submit a portfolio for graduate school admissions, which takes lots of time and effort. On the positive side, however, you will get to show your best work and explain in your own way what makes you a great candidate, instead of relying on test scores.

What is an Undergraduate Student?

Undergraduate studies include Associate’s degrees, such as University of the People’s Associate’s in Health Studies , Associate’s in Computer Science , and Associate’s in Business Administration . Associate’s degrees are shorter and can offer an introduction into a field.

Bachelor’s degrees are also undergraduate programs. There are several types of Bachelor’s degrees, including Bachelor of Science, Bachelor of Arts, and Bachelor of Fine Arts. University of the People offers three Bachelor of Science degrees in Health Studies , Computer Science , and Business Administration .

What is a Graduate Student?

Photo by Burst from Pexels

Graduate studies include Master’s degrees such as Master of Art, Master of Education , Master of Science, Master in Business Administration , Master in Social Work, Master in Fine Arts, and Master in Law (LLM).

University of the People offers flexible online graduate degree programs in Education ( M.Ed ) and Business ( MBA ).

Doctorate students are also graduate students. The most common types of degrees you can earn post graduate are PhD, Doctor of Law, Doctor of Physical Therapy, and Doctor of Medicine.

All in all, while there are many very important differences between undergraduate and graduate school, both have amazing pluses and incredible, yet different, opportunities from each one.

Related Articles

The Many Ways Grad School Differs From College

Be prepared for a tougher workload and more independence as a graduate student.

How Grad School Differs From College

Getty Images

Graduate students usually rely less heavily on textbooks than undergrads, and some of their courses don't include textbooks at all, since the norm is for them to analyze complicated original source materials themselves rather than depending on explanations from others.

Unlike undergraduates, who often take introductory courses in a range of subjects before committing to a major, graduate students typically focus on a particular area of study, such as chemistry or philosophy, from the get-go.

"A graduate degree is more specialized than an undergraduate degree, and it is typically more directly tied to one or several career paths," says Julia Kent, a vice president at the Council of Graduate Schools, an organization that represents universities that grant master's and doctoral degrees.

The most important distinction between college and graduate school, according to higher education experts, is that they are designed with different missions in mind.

The Purpose of College vs. Graduate Studies

A graduate degree is meant to bolster someone's expertise within a field in which they have already demonstrated significant potential. That differs from a college education, which usually includes general education classes in fields like biology and history. A primary goal of a college education is to provide students with "a broad understanding of human civilization," says Robert C. Bird, a professor of business law at the University of Connecticut's business school .

Jana Hunzicker, associate dean for academic affairs at Bradley University's college of education and health sciences in Illinois, notes that a college degree is often the baseline credential required for entry-level positions.

"Most students who pursue a master's degree have a fairly clear idea of what they want to do next in their career," she wrote in an email. And "by the time a student seeks a doctoral degree, he or she has likely reached a point of feeling that they have learned or done as much as they can do without seeking further expert instruction."

Here are several other key differences between college and grad school that experts say prospective grad students should keep in mind.

The Application Process

Personal statements for graduate applications are very different than the ones in college applications, Kent says. "You are expected to explain how completing the degree is tied to your career goals, whereas at the undergraduate level, the focus is often less academic and career-oriented."

Ph.D. programs typically like to see specific information about candidates' research interests and might even wish to hear about particular faculty members the candidates would like to work with. These programs also value research experience, Kent says. Professionally oriented programs, such as those in business and clinical health care fields, often prioritize work experience.

Experts on applied doctoral programs, which are designed to train people for leadership within a specific domain such as education, say that these programs favor students who understand conditions for frontline workers within their field.

The Amount of Personal Awareness and Initiative Required

In graduate school, experts agree, professors expect students to be self-directed and goal-oriented.

If you enroll in grad school, faculty will assume you possess "self-knowledge about what it is that you want to accomplish," says Kent.

Bernadine Mavhungu Jeranyama, an online MBA student at Clark University in Massachusetts, says "intentionality" was one key distinction between her experiences in college and grad school.

"Going to college and graduating with a bachelor’s degree was an expected next step after high school, and a ticket to entry into the working world," she wrote in an email. "The decision to enroll in graduate education came from myself with no outside influence, and I feel more committed to it."

After years in the workforce, Jeranyama realized that she wanted to become an executive who focuses on health equity issues, and she chose a grad degree that aligns with her ambitions.

The Speed, Depth and Difficulty of Courses

Though undergraduate classes can be challenging, in most cases, graduate classes are harder, according to experts.

"Graduate courses tend to cover more material in a shorter period of time," Bird says.

Bird notes that he teaches law classes very differently at the undergraduate vs. the graduate level. In his college classes, he is more likely to provide summaries of court cases, whereas in more advanced courses, he generally asks students to examine legal rulings.

Graduate students usually rely less heavily on textbooks than undergrads, and some of their courses don't include textbooks at all, since the norm is for them to analyze complicated original source materials themselves rather than depending on explanations from others, Bird says.

The Social Environment

Grad students usually have less free time than college students because of the demanding nature of their courses. That is especially true if they are working professionals or parents, experts say.

"In graduate school, there's less time for socializing, and there's less time for going out," Bird says, adding that during law school he lived right near a sports stadium but rarely could find time to see a game there. "You have to focus on your work."

Financial Considerations

Many grad programs require students to pay tuition and fees similar to those at the college level. But Ph.D. students frequently receive funding from whatever university they attend and may receive an annual stipend. "That is very different than a college education where you're paying four years of tuition and having to support yourself as well," Kent says.

Certain short grad programs – such as those that last only a single academic year – require minimal time out of the workforce. Though subsidies for grad school are less plentiful than college scholarships, such awards are available and can be used to reduce student loans.

The Emphasis on Applying Knowledge

According to Kent, hands-on training is common in graduate programs, since students often participate in labs or supervised practicums. And Ph.D. students frequently have some undergraduate teaching responsibilities. "You're getting practice doing the work that you will possibly do in your chosen career and having an opportunity to get feedback from a professor and mentor on that work," she says.

Grad students are expected to use the information they learn in a clever way, not just show they know the facts, says Bird. "It's higher-level thinking that you're expected to do."

Searching for a grad school? Get our complete rankings of Best Graduate Schools.

30 Fully Funded Ph.D. Programs

Tags: education , students , graduate schools , colleges

You May Also Like

What to ask law students and alumni.

Gabriel Kuris April 22, 2024

Find a Strong Human Rights Law Program

Anayat Durrani April 18, 2024

Environmental Health in Medical School

Zach Grimmett April 16, 2024

How to Choose a Law Career Path

Gabriel Kuris April 15, 2024

Questions Women MBA Hopefuls Should Ask

Haley Bartel April 12, 2024

Law Schools With the Highest LSATs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 11, 2024

MBA Programs That Lead to Good Jobs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 10, 2024

B-Schools With Racial Diversity

Sarah Wood April 10, 2024

Law Schools That Are Hardest to Get Into

Sarah Wood April 9, 2024

Ask Law School Admissions Officers This

Gabriel Kuris April 9, 2024

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, what's the difference between undergraduate and graduate-level degrees.

Hi everyone! I've seen people mentioning undergraduate and graduate level degrees, and I'm not sure about what separates the two. Can someone please explain the differences and what each entails? Also, what are some common graduate degree programs?

Hi there! Undergraduate and graduate-level degrees differ in terms of their academic focus, structure, and the stage of education at which they are pursued.

Undergraduate degrees, also referred to as bachelor's degrees, are typically the first level of higher education one pursues after completing high school. These degrees usually require four years of study and involve taking courses in general education as well as in a specific major. Majors can be in a variety of fields like economics, biology, psychology, history, or engineering, among others. Undergraduate education aims to provide you with broad knowledge in your chosen field and to serve as the foundation for your career or for further studies.

Graduate-level degrees, on the other hand, are pursued after completing an undergraduate degree. They are advanced academic programs that offer specialized knowledge in a specific field. Graduate degrees are usually divided into two categories: master's degrees and doctoral degrees.

Master's degrees can take between one and three years to complete, depending on the program and your enrollment status (full-time or part-time). They involve coursework, research, and occasionally internships or practicum experiences. Some common master's degree programs include Master of Business Administration (MBA), Master of Science (MS), Master of Arts (MA), and Master of Fine Arts (MFA).

Doctoral degrees, such as Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) or professional doctorates like Doctor of Medicine (MD) or Juris Doctor (JD), typically require several years of study beyond the master's level. Ph.D. programs usually involve a combination of coursework, research, teaching, and the completion of a dissertation, which is an extensive research project on a specialized topic within your field. MD and JD programs are professional degrees that specifically focus on medical and legal practice, respectively.

In summary, undergraduate degrees are the first level of higher education pursued after high school, whereas graduate-level degrees are advanced academic programs that offer specialized knowledge in a field. Graduate degrees can be further classified into master's programs, which are generally shorter and more focused on coursework, and doctoral programs, which require substantial research and the completion of a dissertation or involve professional practice.

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

- Stories Archive (pre 2021)

February 16, 2022

- Undergraduate vs. Graduate School

What’s the difference between graduate and undergraduate study?

The growth of master’s degree programs has been significant in the last two decades. And it’s not surprising given the Bureau of Labor Statistics projection that employment in occupations requiring a master’s degree will increase 17% by 2026.

Graduate school is a different experience than studying for your undergraduate degree. But how different is it?

Knowing what is expected of you and how to best prepare will help you as you consider your options for attending graduate school to earn your master’s degree . One of the keys to success is to know all expectations before you even begin.

Here are some ways that graduate school differs from undergraduate study.

1. Leadership development

An undergraduate degree gives you a broad knowledge base, but a graduate school degree provides specialized knowledge to prepare you for leadership roles in your chosen career.

In graduate school, you’ll gain the leadership skills companies are looking for in management positions. In addition, you’ll develop the critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication skills necessary to be a strong leader.

2. Professional marketability

SUNY Empire graduate school students tell us they’re earning their master’s degree to differentiate themselves in a competitive job market.

Often, undergraduate degrees help you obtain entry-level positions. A graduate school degree can expand your job market and career options and make you a more favorable candidate to employers. Additionally, graduate school can introduce you to a more extensive professional network. When applying for promotions and leadership positions, a graduate degree can help you stand out.

3. Research experience

Research experience is valuable in almost any line of work. It teaches you to think critically and logically, find answers to your questions, and apply those findings to your work.

Research in an undergraduate program typically consists of introductory research projects and papers. In graduate school, research is the primary focus in many of your assignments. Occasionally, in graduate school programs, you may find the opportunity to learn from or participate in your professors’ research and discover your area of interest.

4. Specific coursework

In undergraduate programs, students take general education courses and electives in addition to their program requirements. In graduate school, your courses will be more specific. Graduate school programs provide a higher level of individualized learning to serve your unique goals and start to become an expert in your field.

5. You’ll be immersed in a diverse community

The average graduate student is 33 years old, and most work part-time or full-time while completing their graduate school work.

In graduate programs, you’ll connect with experienced students with similar interests and goals while learning from and being challenged by peers from diverse backgrounds with different work and life experiences.

Why Choose SUNY Empire?

Choosing the right school and degree is a good place to start your graduate program journey.

SUNY Empire’s real-world-ready graduate programs can be completed fully online (although some are enhanced with onsite residencies), which means you can work and live your life while earning your graduate degree. We offer 22 graduate degrees and 26 advanced certificates in business, policy, education, and liberal studies through the School for Graduate Studies and the School of Nursing and Allied Health.

Take the next step with SUNY Empire and explore our graduate programs by registering for an information session.

- Alex Davidson '20

- Jason Russo

- Judith Rae '04, '06

- Matthew Kilgore '18

- Matthew Prescott

- What can I do with a bachelor’s degree in psychology?

- Business Analyst vs. Data Analyst: What’s the Difference?

- Christopher Burke '07

- Emma Kahn ’21

- How to get a BS?

- Is a Human Resources Degree Worth it?

- Lisa Bryk '16

- Martina Hušková '05

- Pete Marzahl '15, '18

- What is a Bachelor of Business Administration Degree (BBA) and Why Should I Earn One?

- 2020 Alumni Awardees

- 2021 Alumni Awardees

- Andrea Wolper ’95: Showcasing Her Creative Spirit

- Brenda Simmons ’05: Preserving Black History in a Resort Town

- Daniela Maniscalchi '21

- Elena O'Connor sings opera in Europe and the U.S.

- Emad Rahim, ’02, ’03

- Enhancing Access and Support at SUNY Empire: Do I Need Accessibility Services?

- Ennis Smith ’04: Telling a Big Story With a Tiny Essay

- George Irlbacher ’83: Playing Santa is Serious Business

- James Allan Matte ’76: A Lifetime Spent Eliciting the Truth

- Kenya Cagle ´81 ´83: Following His Passion for Film

- Larry Johnson ’21: Heading to the Finish Line

- Liza Rochelson '20

- Lois Barth ’12: Finding Her Courage to Sparkle

- Mark Spawn ’07: Doing Detective Work With a True Crime Podcast

- Michell Wright Jumpp '06

- Nan Eileen Mead ’15 ’20 ’22: Advocating for Educational Equity for All

- Rhoda Overstreet-Wilson ’06: Twice a First in Central New York

- Ryan Zieno '16

- American Dream Comes True for Seyon Srithar ’22

- Sonja Thomson

- Terri Maher

- Toneisha Colson, ’17, '19

- Why Choose a Bachelor of Science in Public Health?

- 3 Reasons You Should Get Your Degree in 2024

- Nan Eileen Mead '15, '20

- Samantha Marnon '19

- Step-by-Step Guide: Accessing SUNY Empire’s Office of Accessibility Resources and Services

Graduate Studies

- 3 Benefits of a Combined Degree Program

- Advance Your Nursing Career at SUNY’s Leading Online Institution

- Barry Eisenberg

- Christine Jensen '19

- Jennifer Pettis, MS, RN, CNE ’12, ’17

- Kenichea Nichols '20

- Mark Abendroth

- Oliver Riley '12, '20

- Rachel Sabella '20

- Roxana Toma

- Why Earn Your Applied Analytics Degree?

Labor and Policy

Military and veterans.

- Doug "Brian" Sherman '17

Nursing and Allied Health

- Dianne White

- Nakesha Vines '20

- What is a Bachelor of Science in Allied Health and Why Should I Earn One?

- Why Choose a Master’s in Nursing Education?

Science and Tech

- 3 Good Reasons to Earn an Advanced Certificate in Cybersecurity

- Blain Smith '20

- SUNY Empire’s Oldest Graduate in Class of 2022 Has No Plans to Stop Learning

Smart Cookies

They're not just in our classes – they help power our website. Cookies and similar tools allow us to better understand the experience of our visitors. By continuing to use this website, you consent to SUNY Empire State University's usage of cookies and similar technologies in accordance with the university's Privacy Notice and Cookies Policy .

2 million+ students helped annually

Subscribe Today

For exclusive college and grad school planning content.

For more exclusive college and grad school planning content.

100+ guides available for free

7+ years worth of content

2 million+ students helped until now

Difference Between Undergraduate And Graduate

The various levels of education and degrees offered within and across countries is immense. Because of different educational systems, the names of degrees are not the same. This can cause a lot of confusion amongst prospective students. So, what’s the difference between graduate and undergraduate degrees?

When you are choosing a university and a degree to attend and complete, you want to know all the details of what you are about to start. For most students, they want to know what kind of degree they are completing. Their educational journey requires them to know what the difference between graduate and undergraduate studies is.

Students who are going to the United States to study, especially, have problems distinguishing between the two degrees. This is because they might have different names in different countries. This article will cover the main difference between undergraduate and graduate studies and explain the details.

What are undergraduate studies?

Undergraduate studies are degrees which lead to the student graduating with a Bachelor’s or an Associate Degree . Bachelor’s Degrees take approximately four years to complete. They can be done at colleges or universities. Associate degrees require two years of study. These degrees can be done at a community college, college, or vocational school.

Students enrolled in a Bachelor’s or Associate program are called undergraduate students. Based on their degrees, students get a Bachelor or Arts (BA) or Bachelor of Science (BSc). They can also get more specialized degrees such as Bachelor of English Literature, Bachelor of Computer Science etc.

What are graduate studies?

Graduate studies are the next step after students complete their undergraduate degrees . Graduate degrees can be completed after a Bachelor’s or an Associate degree.

They can be of two types:

Master’s Degrees

- Doctoral Degrees (PhD)

Master’s Degrees are typically one to two years of full time study , but can take longer depending on your degree and method of study (part-time, distance, etc.). There are different types and in specialized fields and include coursework and research.

At the end, students can graduate with titles such as:

- Master of Arts

- Master of Science

- Master of Engineering

- Master of Education , etc.

The degrees include practical work and at the end, students complete a capstone project or a thesis work .

Doctoral Degrees

Doctoral Degrees are more advanced than Master’s Degrees in their content. They can take around three to six years to complete, depending on the field of study. Master’s Degrees require half coursework and half research work. Doctoral degrees are mostly focused on research and only have a few courses.

Students choose a specific part of their field, which they are interested in researching. They then conduct experiments and field studies to finally publish their dissertation. The dissertation is almost like a book, with hundreds of pages in length. It contains the original published research of the PhD student. In addition, PhDs also include teaching as graduate or research assistants.

Postgraduate vs Graduate Studies

Within the undergraduate vs graduate differences, students also experience some confusion regarding the meanings of postgraduate and graduate studies. In fact, there is no difference between the terms . Some countries use one or the other to mean the same thing.

In the U.S, undergraduate studies are for Bachelor’s Degrees, and graduate studies are for Master’s or Doctoral Degrees. In other countries of Europe , graduate studies are for Bachelor’s, and postgraduate studies are for Master’s and Doctoral Degrees.

So in essence, graduate and postgraduate studies have the same meaning. Both degrees are equivalents of each other no matter where you are getting them. What matters is that you are graduating from an accredited institution.

Undergraduate vs Graduate

Besides their names, there are more differences between undergraduate and graduate degrees. Students who have completed high school may choose to either get an undergraduate degree or go directly to graduate school. Either one would give them similar skills. However, it is best to know what undergraduate vs graduate studies entail. By knowing the differences, it is easier to make a decision.

The degree you get

The first difference between graduate and undergraduate studies is the degree you graduate with. As mentioned, when you complete undergraduate studies you get a Bachelor’s Degree. When you complete graduate studies, you get either a Master’s Degree or a Doctoral Degree.

Content of studies

The main difference between undergraduate and graduate studies is the content of courses. Bachelor’s Degrees are tailored to give students a general overview of many subjects. Students learn writing, analysis, and critical thinking skills.

Even if they are completing their undergraduate degrees in a specific field, students will have some general courses. These general courses might not relate to their field. This is because undergraduate studies do not require students to make a final decision about what they want to specialize in.

That is where graduate studies come into play. After getting a general sense of many subjects in undergraduate school, students pick a specific field. This will be the field they will get their graduate degree in. For example, a student who has a Bachelor Degree in English Literature, can complete their graduate studies in Shakespeare’s work. Or a student with a Bachelor Degree in Economics can choose to do a Master’s or a PhD in Economics of Developing Countries.

So the content of studies in this case is more general for undergraduates and highly specific in graduate studies.

The coursework which makes up the two degrees is also different. Undergraduate students usually have around 5 to 7 courses every semester . Graduate students have around 4 courses per semester . This, of course, depends on the field of study, since graduate students might have more courses. Generally though, graduate programs have less coursework than undergraduate ones.

The reason for this is that graduate studies have more research focused classes. Traditional coursework is lower. This makes graduate students take less courses, but they are more intense in the content that they have.

In addition to the content and coursework, the evaluation of students is also different in undergraduate and graduate levels. During undergraduate studies, since students are still getting basic knowledge in a variety of subjects, evaluation is mostly done through exams. This is to test their proficiency in basic concepts of higher education studies.

In graduate school, though, it is assumed that students are already familiar with the basics. Evaluation then is mostly focused on projects that are research oriented. Graduate students have already chosen their specialty, so they mostly do research. The research is based on the practical application of the concepts that they have learned during their undergraduate studies.

Change of majors

Since undergraduate studies are more general, changing majors is a lot easier. Each undergraduate field of study has a few similar courses. Also, undergraduate universities have similar curricula. This makes changing subjects and transferring universities more feasible than for graduate school.

Graduate studies are more specific. Even within one field of study, there are multiple approaches that the coursework can take. So is it more difficult to switch from one subject to the other. It is also challenging to transfer to another university. That is because the curricula can be different, even within the same topics.

Admission requirements

The process of getting into undergraduate or graduate studies is also quite different. Admissions requirements for undergraduate studies include:

- High school transcript and diploma

- Scholastic Aptitude/Assessment Test (SAT) or American College Testing (ACT) scores

- For international students, TOEFL or IELTS English proficiency scores

- One or two essays

For graduate studies , on the other hand, admission requirements include:

- Bachelor’s Degree transcripts and diploma

- Graduate Records Examination (GRE) or Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) scores

- GPA of at least 3.0 (or equivalent grades)

- Letters of recommendation

- Statement of purpose or research proposal

Since graduate studies are more specific, they have stricter admissions requirements. The programs are also highly competitive.

Student-Professor Relationship

During undergraduate studies , professors have a more active role in teaching students. They communicate the basic skills which students need to succeed in the labor market. Students are actively seeking answers and explanations from them in relation to what is taught in class.

In graduate school, on the other hand, professors take a role that focuses on guidance rather than active explanations. Professors become mentors to students. They give advice in relation to their research progress and methods. They do not usually teach students how to complete the research, but what approach to take.

Class Discussions

Another difference between undergraduate and graduate studies is the level of class discussions .

In undergraduate classrooms, students express opinions and ask questions . These discussions, though are on a less advanced and less experienced level. Professors also have a more active role in stepping in to correct mistakes relating to the concepts that are being taught. In addition, they try to foster a way of thinking that is necessary for success in that particular field.

In graduate school class discussions are highly advanced . Students in graduate school have more work experience and are not coming directly from high school. That is why their opinions come from personal experiences and not only theory. They debate and learn from each other, while the role of the professor in this case, is to guide the discussion in the right direction. Students tend to stray away from topics, so professors guide it. They do not necessarily correct any mistakes or add much to the theoretical concepts.

Post-graduation Prospects

What makes undergraduate and graduate studies so different is also the career options . After graduation, students can take a variety of career paths. Students with only a Bachelor’s Degree have more limited options though. They more often than not start out in lower paid, entry level positions. In addition, they usually require additional training specific to their job, since their degrees are so general.

Students with completed graduate degrees have more career options. They can go on to work in different sectors of the economy. They take jobs in the public, private, or non-profit firms. They also have a higher salary and more advanced positions. Also, they can get involved in academia. This includes graduate teaching assistants or professors if they complete their PhDs. Undergraduate students cannot do that because professors are required to have specific knowledge.

Latest article

How to choose an mba program: 9 things to consider, best mba in cybersecurity programs (2024), best us states for international students (2024), featured guides you should read, best mba in finance programs (2024).

MastersDegree.net is your go-to platform for college and graduate school planning. From choosing your ideal program and funding your studies to graduating successfully and competing in the job market.

© MastersDegree.net - All rights reserved - 2017 - 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.16(1); Spring 2017

Why Work with Undergraduate Researchers? Differences in Research Advisors’ Motivations and Outcomes by Career Stage

Associated data.

In interviews, many undergraduate research advisors stated intrinsic motivations, but some early-career advisors expressed only instrumental motivations. This study explores what this means for how advisors work with undergraduate researchers and the implications for training and retaining advisors who can provide high-quality research experiences.

Undergraduate research is often hailed as a solution to increasing the number and quality of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics graduates needed to fill the high-tech jobs of the future. Student benefits of research are well documented but the emerging literature on advisors’ perspectives is incomplete: only a few studies have included the graduate students and postdocs who often serve as research advisors, and not much is known about why research advisors choose to work with undergraduate researchers. We report the motivations for advising undergraduate researchers, and the related costs and benefits of doing so, from 30 interviews with research advisors at various career stages. Many advisors stated intrinsic motivations, but a small group of early-career advisors expressed only instrumental motivations. We explore what this means for how advisors work with student researchers, the benefits students may or may not gain from the experience, and the implications for training and retaining research advisors who can provide high-quality research experiences for undergraduate students.

INTRODUCTION

The benefits of undergraduate research for students are well documented and include personal and professional gains, research skills, career clarification, enhanced preparation for careers and graduate school, and the ability to think and work like a scientist ( Osborn and Karukstis, 2009 ; Laursen et al. , 2010 ; Lopatto and Tobias, 2010 ; Linn et al. , 2015 ). Other researchers have linked participation in undergraduate research with intention to continue in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)-related graduate programs, particularly for students otherwise underrepresented in these fields (National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, 2011 ; Eagan et al. , 2013 ). One study even reported that undergraduate researchers reported increased productivity and satisfaction when they advanced and in turn became advisors for undergraduate research projects during their graduate studies ( Lunsford, 2012 ).

Because of these benefits, undergraduate research opportunities have been, and continue to be, an important aspect of federal plans to help improve STEM education and train qualified students for the STEM workforce of the future (Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University, 1998 ; National Science and Technology Council, 2013 ). While these plans advocate for increasing access to undergraduate research opportunities, this goal presents challenges. Either we must find ways to increase the number of students each research advisor can sponsor, or we must increase the number of advisors who work with undergraduates in apprentice-style research. Increasing the number of students each advisor works with presents challenges, as advisors may be pressured to take on less-prepared students who require more time to train or to take on too many students to provide meaningful personal interactions with all of them ( Laursen et al. , 2010 ). Course-based research experiences are another possible way to increase the number of students working with each research advisor ( Bangera and Brownell, 2014 ; Corwin-Auchincloss et al. , 2014 ; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015 ). This approach is currently being tested and studied.

The other tactic for increasing the number of potential research advisors who engage undergraduates in apprentice-style research experiences presents its own challenges. Proper training may be necessary to ensure that new advisors are prepared to provide high-quality research experiences for undergraduates ( Pfund et al. , 2006 ). In fact, in a large-scale survey of both advisors and students involved in research experiences, students’ most commonly suggested improvement was more frequent and better quality guidance from their advisors ( Russell et al. , 2007 ).