- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Scott Atlas

- Thomas Sargent

- Stephen Kotkin

- Michael McConnell

- Morris P. Fiorina

- John F. Cogan

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- National Security, Technology & Law

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press, the religious sources of islamic terrorism.

What the fatwas say

W hile terrorism — even in the form of suicide attacks — is not an Islamic phenomenon by definition, it cannot be ignored that the lion’s share of terrorist acts and the most devastating of them in recent years have been perpetrated in the name of Islam. This fact has sparked a fundamental debate both in the West and within the Muslim world regarding the link between these acts and the teachings of Islam. Most Western analysts are hesitant to identify such acts with the bona fide teachings of one of the world’s great religions and prefer to view them as a perversion of a religion that is essentially peace-loving and tolerant. Western leaders such as George W. Bush and Tony Blair have reiterated time and again that the war against terrorism has nothing to do with Islam. It is a war against evil.

The non-Islamic etiologies of this phenomenon include political causes (the Israeli-Arab conflict); cultural causes (rebellion against Western cultural colonialism); and social causes (alienation, poverty). While no public figure in the West would deny the imperative of fighting the war against terrorism, it is equally politically correct to add the codicil that, for the war to be won, these (justified) grievances pertaining to the root causes of terrorism should be addressed. A skeptic may note that many societies can put claim to similar grievances but have not given birth to religious-based ideologies that justify no-holds-barred terrorism. Nevertheless an interpretation which places the blame for terrorism on religious and cultural traits runs the risk of being branded as bigoted and Islamophobic.

The political motivation of the leaders of Islamist jihadist-type movements is not in doubt. A glance at the theatres where such movements flourished shows that most fed off their political — and usually military — encounter with the West. This was the case in India and in the Sudan in the nineteenth century and in Egypt and Palestine in the twentieth. The moral justification and levers of power for these movements, however, were for the most part not couched in political terms, but based on Islamic religious sources of authority and religious principles. By using these levers and appealing to deeply ingrained religious beliefs, the radical leaders succeed in motivating the Islamist terrorist, creating for him a social environment that provides approbation and a religious environment that provides moral and legal sanction for his actions. The success of radical Islamic organizations in the recruitment, posting, and ideological maintenance of sleeper activists (the 9-11 terrorists are a prime example) without their defecting or succumbing to the lure of Western civilization proves the deep ideological nature of the phenomenon.

Therefore, to treat Islamic terrorism as the consequence of political and socioeconomic factors alone would not do justice to the significance of the religious culture in which this phenomenon is rooted and nurtured. In order to comprehend the motivation for these acts and to draw up an effective strategy for a war against terrorism, it is necessary to understand the religious-ideological factors — which are deeply embedded in Islam.

The Weltanschauung of radical Islam

M odern international Islamist terrorism is a natural offshoot of twentieth-century Islamic fundamentalism. The “Islamic Movement” emerged in the Arab world and British-ruled India as a response to the dismal state of Muslim society in those countries: social injustice, rejection of traditional mores, acceptance of foreign domination and culture. It perceives the malaise of modern Muslim societies as having strayed from the “straight path” ( as-sirat al-mustaqim ) and the solution to all ills in a return to the original mores of Islam. The problems addressed may be social or political: inequality, corruption, and oppression. But in traditional Islam — and certainly in the worldview of the Islamic fundamentalist — there is no separation between the political and the religious. Islam is, in essence, both religion and regime ( din wa-dawla ) and no area of human activity is outside its remit. Be the nature of the problem as it may, “Islam is the solution.”

The underlying element in the radical Islamist worldview is ahistoric and dichotomist: Perfection lies in the ways of the Prophet and the events of his time; therefore, religious innovations, philosophical relativism, and intellectual or political pluralism are anathema. In such a worldview, there can exist only two camps — Dar al-Islam (“The House of Islam” — i.e., the Muslim countries) and Dar al-Harb (“The House of War” — i.e., countries ruled by any regime but Islam) — which are pitted against each other until the final victory of Islam. These concepts are carried to their extreme conclusion by the radicals; however, they have deep roots in mainstream Islam.

While the trigger for “Islamic awakening” was frequently the meeting with the West, Islamic-motivated rebellions against colonial powers rarely involved individuals from other Muslim countries or broke out of the confines of the territories over which they were fighting. Until the 1980 s, most fundamentalist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan Muslimun ) were inward-looking; Western superiority was viewed as the result of Muslims having forsaken the teachings of the Prophet. Therefore, the remedy was, first, “re-Islamization” of Muslim society and restoration of an Islamic government, based on Islamic law ( shari’ah ). In this context, jihad was aimed mainly against “apostate” Muslim governments and societies, while the historic offensive jihad of the Muslim world against the infidels was put in abeyance (at least until the restoration of the caliphate).

Until the 1980 s, attempts to mobilize Muslims all over the world for a jihad in one area of the world (Palestine, Kashmir) were unsuccessful. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was a watershed event, as it revived the concept of participation in jihad to evict an “infidel” occupier from a Muslim country as a “personal duty” ( fard ’ein ) for every capable Muslim. The basis of this duty derives from the “irreversibility” of Islamic identity both for individual Muslims (thus, capital punishment for “apostates” — e.g., Salman Rushdie) and for Muslim territories. Therefore, any land (Afghanistan, Palestine, Kashmir, Chechnya, Spain) that had once been under the sway of Islamic law may not revert to control by any other law. In such a case, it becomes the “personal duty” of all Muslims in the land to fight a jihad to liberate it. 1 If they do not succeed, it becomes incumbent on any Muslim in a certain perimeter from that land to join the jihad and so forth. Accordingly, given the number of Muslim lands under “infidel occupation” and the length of time of those occupations, it is argued that it has become a personal duty for all Muslims to join the jihad. This duty — if taken seriously — is no less a religious imperative than the other five pillars of Islam (the statement of belief or shahadah , prayer, fasting, charity, and haj ). It becomes a de facto (and in the eyes of some a de jure) sixth pillar; a Muslim who does not perform it will inherit hell.

Such a philosophy attributing centrality to the duty of jihad is not an innovation of modern radical Islam. The seventh-century Kharijite sect, infamous in Islamic history as a cause of Muslim civil war, took this position and implemented it. But the Kharijite doctrine was rejected as a heresy by medieval Islam. The novelty is the tacit acceptance by mainstream Islam of the basic building blocks of this “neo-Kharijite” school.

The Soviet defeat in Afghanistan and the subsequent fall of the Soviet Union were perceived as an eschatological sign, adumbrating the renewal of the jihad against the infidel world at large and the apocalyptical war between Islam and heresy which will result in the rule of Islam in the world. Along with the renewal of the jihad, the Islamist Weltanschauung, which emerged from the Afghani crucible, developed a Thanatophile ideology 2 in which death is idealized as a desired goal and not a necessary evil in war.

An offshoot of this philosophy poses a dilemma for theories of deterrence. The Islamic traditions of war allow the Muslim forces to retreat if their numerical strength is less than half that of the enemy. Other traditions go further and allow retreat only in the face of a tenfold superiority of the enemy. The reasoning is that the act of jihad is, by definition, an act of faith in Allah. By fighting a weaker or equal enemy, the Muslim is relying on his own strength and not on Allah; by entering the fray against all odds, the mujahed is proving his utter faith in Allah and will be rewarded accordingly.

The politics of Islamist radicalism has also bred a mentality of bello ergo sum (I fight, therefore I exist) — Islamic leaders are in constant need of popular jihads to boost their leadership status. Nothing succeeds like success: The attacks in the United States gave birth to a second wave of mujahidin who want to emulate their heroes. The perception of resolve on the part of the West is a critical factor in shaping the mood of the Muslim population toward radical ideas. Therefore, the manner by which the United States deals with the present crisis in Iraq is not unconnected to the future of the radical Islamic movement. In these circles, the American occupation of Iraq is likened to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan; a sense of American failure would feed the apocalyptical ideology of jihad.

The legality of jihad

T hese beliefs are commonly viewed as typical of radical Islamic ideology, but few orthodox Islamic scholars would deny that they are deeply rooted in orthodox Islam or would dismiss the very ideology of jihad as a military struggle as foreign to the basic tenets of Islam.

Hence, much of the debate between radicals and nonradicals is not over the religious principles themselves, but over their implication for actual behavior as based on the detailed legal interpretation of those principles. This legal interpretation is the soul of the debate. Even among moderate Islamic scholars who condemn acts of terrorism (albeit with reservation so as not to include acts perpetrated against Israel in such a category), there is no agreement on why they should be condemned: Many modernists acknowledge the existence of a duty of jihad in Islam but call for an “Islamic Protestantism” that would divest Islam of vestiges of anachronistic beliefs; conservative moderates find in traditional Islamic jurisprudence ( shari’ah ) legal justification to put the imperative of jihad in abeyance; others use linguistic analysis to point out that the etymology of the word jihad ( jahada ) actually means “to strive,” does not mean “holy war,” and does not necessarily have a military connotation. 3

The legalistic approach is not a barren preoccupation of scholars. The ideal Islamic regime is a nomocracy: The law is given and immutable, and it remains for the leaders of the ummah (the Islamic nation) to apply it on a day-to-day basis. Islam is not indifferent to any facet of human behavior; all possible acts potentially have a religious standing, ranging between “duty” ( fard , pl. fara’id ); “recommended” ( mandub ); “optional” ( jaiz ); “permitted” ( mubah ); “reprehensible” ( makruh ); and “forbidden” ( haram ). This taxonomy of human behavior has far-reaching importance for the believer: By performing all his religious duties, he will inherit paradise; by failing to do so (“sins of omission”) or doing that which is forbidden (“sins of commission”), he will be condemned to hell. Therefore, such issues as the legitimacy of jihad — ostensibly deriving from the roots of Islam — cannot be decided by abstract morality 4 or by politics, but by meticulous legal analysis and ruling ( fatwa ) according to the shari’ah , performed by an authoritative Islamic scholar (’ alem , pl. ’ ulama ).

The use of fatwas to call for violent action first became known in the West as a result of Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie, and again after Osama bin Laden’s 1998 fatwa against the United States and Israel. But as a genuine instrument of religious deliberation, it has not received the attention it deserves. Analysts have frequently interpreted fatwas as no more than the cynical use of religious terminology in political propaganda. This interpretation does not do justice to the painstaking process of legal reasoning invested in these documents and the importance that their authors and their target audience genuinely accord to the religious truthfulness of their rulings.

The political strength of these fatwas has been time-tested in Muslim political society by rebels and insurgents from the Arabian peninsula to Sudan, India, and Indonesia. At the same time, they have been used by Muslim regimes to bolster their Islamic credentials against external and domestic enemies and to legitimize their policies. This was done by the Sudanese mahdi in his rebellion against the British ( 1881-85 ); by the Ottoman caliphate (December 1914 ) in World War i ; by the Syrian regime against the rebellion in northern Syria ( 1981 ); and, mutatis mutandis, by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to legitimize his peace policies toward Israel.

The fatwas promulgated by sheikhs and ’ulama who stipulate that jihad is a “personal duty” play, therefore, a pivotal role in encouraging radicalism and in building the support infrastructure for radicals within the traditional Islamic community. While one may find many fatwas which advocate various manifestations of terrorism, fatwas which rule that those who perform these acts do not go to paradise but inherit hell are few and far between.

The questions relating to jihad which are referred to the religious scholars 5 relate to a number of issues:

The very definition, current existence, and area of application of the state of jihad . Is jihad one of the “pillars” ( arkan ) or “roots” ( usul ) of Islam? Does it necessarily imply military war, or can it be perceived as a duty to spread Islam through preaching or even the moral struggle between one’s soul and Satan? 6 If the former, then what are the necessary conditions for jihad ? Does a state of jihad currently exist between Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Harb ? And how can one define Dar al-Islam today, in the absence of a caliphate? Is the rest of the world automatically defined as Dar al-Harb with which a state of jihad exists, or do the treaties and diplomatic relations which exist between Muslim countries and “infidel” countries (including the charter of the United Nations) change this? 7

Who must participate in jihad, and how ? Is jihad a personal duty ( fard ’ein ) for each and every Muslim under all circumstances or a collective duty ( fard kiffaya ) that can be performed only under the leadership of a leader of all Muslims ( imam , khalifa , amir al-mu’aminin )? Is it incumbent on women? On minors? (According to Islamic law, in the case of a defensive jihad for the liberation of Islamic territory from infidel occupation, “a woman need not ask permission of her husband nor a child of his parents nor a slave of his master.”) May a Muslim refrain from supporting his attacked brethren or obey a non-Muslim secular law which prohibits him from supporting other Muslims in their struggle?

How should the jihad be fought (jus in bellum) ? The questions in this area relate, inter alia, to: ( a ) Is jihad by definition an act of conflict against the actual “infidels” or can it be defined as a spiritual struggle against the “evil inclination”? If it is the former, must it take the form of war ( jihad fi-sabil Allah ) or can it be performed by way of preaching and proselytization ( da’awah )? ( b ) Who is a legitimate target? Is it permissible to kill noncombatant civilians — women, children, elderly, and clerics; “protected” non-Muslims in Muslim countries — local non-Muslims or tourists whose visas may be interpreted as Islamic guarantees of passage ( aman ); Muslim bystanders? ( c ) The legitimacy of suicide attacks ( istishhad ) as a form of jihad in the light of the severe prohibition on a Muslim taking his own life, on one hand, and the promise of rewards in the afterlife for the shahid who falls in a jihad on the other hand. 8 ( d ) The weapons which may be used. For example, may a hijacked plane be used as a weapon as in the attacks of September 11 in the light of Islamic prohibitions on killing prisoners? ( e ) The status of a Muslim who aids the “infidels” against other Muslims. ( f ) The authority to implement capital punishment in the absence of a caliph.

How should jihad be funded ? “Pocketbook jihad” is deeply entrenched in Islamic tradition. It is based on the injunction that one must fight jihad with his soul or with his tongue ( jihad al-lissan or da’awah ) or with his money ( jihad fi-mal ). Therefore, financial support of jihad is politically correct and even good for business for the wealthy supporter. The transfer of zakat (almsgiving) raised in a community for jihad fi-sabil Allah (i.e., jihad on Allah’s path or military jihad) has wide religious and social legitimacy. 9 The precepts of “war booty” ( ghaneema or fay’ ) call for a fifth ( khoms ) to be rendered to the mujahidin. Acts that would otherwise be considered religiously prohibited are thus legitimized by the payment of such a “tax” for the sake of jihad. While there have been attempts to bring Muslim clerics to denounce acts of terrorism, none, to date, have condemned the donation of money for jihad.

The dilemma of the moderate Muslim

I t can be safely assumed that the great majority of Muslims in the world have no desire to join a jihad or to politicize their religion. However, it is also true that insofar as religious establishments in most of the Arabian peninsula, in Iran, and in much of Egypt and North Africa are concerned, the radical ideology does not represent a marginal and extremist perversion of Islam but rather a genuine and increasingly mainstream interpretation. Even after 9-11 , the sermons broadcast from Mecca cannot be easily distinguished from those of al Qaeda.

Facing the radical Weltanschauung, the moderate but orthodox Muslim has to grapple with two main dilemmas: the difficulty of refuting the legal-religious arguments of the radical interpretation and the aversion to — or even prohibition of — inciting an Islamic Kulturkampf which would split the ranks of the ummah .

The first dilemma is not uniquely Islamic. It is characteristic of revelation-based religions that the less observant or less orthodox will hesitate to challenge fundamental dogmas out of fear of being branded slack or lapsed in their faith. They will prefer to pay their dues to the religious establishment, hoping that by doing so they are also buying their own freedom from coercion. On a deeper level, many believers who are not strict in observance may see their own lifestyle as a matter of convenience and not principle, while the extreme orthodox is the true believer to whom they defer.

This phenomenon is compounded in Islam by the fact that “Arab” Sunni Islam never went though a reform. 10 Since the tenth century, Islam has lacked an accepted mechanism for relegating a tenet or text to ideological obsolescence. Until that time, such a mechanism — ijtihad — existed; ijtihad is the authorization of scholars to reach conclusions not only from existing interpretations and legal precedents, but from their own perusal of the texts. In the tenth century, the “gates of ijtihad ” were closed for most of the Sunni world. It is still practiced in Shiite Islam and in Southeast Asia. Reformist traditions did appear in non-Arab Middle Eastern Muslim societies (Turkey, Iran) and in Southeast Asian Islam. Many Sufi (mystical) schools also have traditions of syncretism, reformism, and moderation. These traditions, however, have always suffered from a lack of wide legitimacy due to their non-Arab origins and have never been able to offer themselves as an acceptable alternative to ideologies born in the heartland of Islam and expressed in the tongue of the Prophet. In recent years, these societies have undergone a transformation and have adopted much of the Middle Eastern brand of Islamic orthodoxy and have become, therefore, more susceptible to radical ideologies under the influence of Wahhabi missionaries, Iranian export of Islam, and the cross-pollination resulting from the globalization of ideas in the information age.

The second dilemma — the disinclination of moderates to confront the radicals — has frequently been attributed to violent intimidation (which, no doubt, exists), but it has an additional religious dimension. While the radicals are not averse to branding their adversaries as apostates, orthodox and moderate Muslims rarely resort to this weapon. Such an act ( takfir — accusing another Muslim of heresy [ kufr ] by falsifying the roots of Islam, allowing that which is prohibited or forbidding that which is allowed) is not to be taken lightly; it contradicts the deep-rooted value that Islam places on unity among the believers and its aversion to fitna (communal discord). It is ironic that a religious mechanism which seems to have been created as a tool to preserve pluralism and prevent internal debates from deteriorating into civil war and mutual accusations of heresy (as occurred in Christian Europe) has become a tool in the hands of the radicals to drown out any criticism of them.

Consequently, even when pressure is put on Muslim communities, there exists a political asymmetry in favor of the radicals. Moderates are reluctant to come forward and to risk being accused of apostasy. For this very reason, many Muslim regimes in the Middle East and Asia are reluctant to crack down on the religious aspects of radical Islam and satisfy themselves with dealing with the political violence alone. By way of appeasement politics, they trade tolerance of jihad elsewhere for local calm. Thus, they lose ground to radicals in their societies.

The Western dilemma

I t is a tendency in politically oriented Western society to assume that there is a rational pragmatic cause for acts of terrorism and that if the political grievance is addressed properly, the phenomenon will fade. However, when the roots are not political, it is naïve to expect political gestures to change the hearts of radicals. Attempts to deal with the terrorist threat as if it were divorced from its intellectual, cultural, and religious fountainheads are doomed to failure. Counterterrorism begins on the religious-ideological level and must adopt appropriate methods. The cultural and religious sources of radical Islamic ideology must be addressed in order to develop a long-range strategy for coping with the terrorist threat to which they give birth.

However, in addressing this phenomenon, the West is at a severe disadvantage. Western concepts of civil rights along with legal, political, and cultural constraints preclude government intervention in the internal matters of organized religions; they make it difficult to prohibit or punish inflammatory sermons of imams in mosques (as Muslim regimes used to do on a regular basis) or to punish clerics for fatwas justifying terrorism. Furthermore, the legacy of colonialism deters Western governments from taking steps that may be construed as anti-Muslim or as signs of lingering colonialist ideology. This exposes the Western country combating the terrorist threat to criticism from within. Even most of the new and stringent terrorism prevention legislation that has been enacted in some counties leans mainly on investigatory powers (such as allowing for unlimited administrative arrests, etc.) and does not deal with prohibition of religion-based “ideological crimes” (as opposed to anti-Nazi and anti-racism laws, which are in force in many countries in Europe).

The regimes of the Middle East have proven their mettle in coercing religious establishments and even radical sheikhs to rule in a way commensurate with their interests. However, most of them show no inclination to join a global (i.e., “infidel”) war against radical Islamic ideology. Hence, the prospect of enlisting Middle Eastern allies in the struggle against Islamic radicalism is bleak. Under these conditions, it will be difficult to curb the conversion of young Muslims in the West to the ideas of radicalism emanating from the safe houses of the Middle East. Even those who are not in direct contact with Middle Eastern sources of inspiration may absorb the ideology secondhand through interaction of Muslims from various origins in schools and on the internet.

Fighting hellfire with hellfire

T aking into account the above, is it possible — within the bounds of Western democratic values — to implement a comprehensive strategy to combat Islamic terrorism at its ideological roots? First, such a strategy must be based on an acceptance of the fact that for the first time since the Crusades, Western civilization finds itself involved in a religious war; the conflict has been defined by the attacking side as such with the eschatological goal of the destruction of Western civilization. The goal of the West cannot be defense alone or military offense or democratization of the Middle East as a panacea. It must include a religious-ideological dimension: active pressure for religious reform in the Muslim world and pressure on the orthodox Islamic establishment in the West and the Middle East not only to disengage itself clearly from any justification of violence, but also to pit itself against the radical camp in a clear demarcation of boundaries.

Such disengagement cannot be accomplished by Western-style declarations of condemnation. It must include clear and binding legal rulings by religious authorities which contradict the axioms of the radical worldview and virtually “excommunicate” the radicals. In essence, the radical narrative, which promises paradise to those who perpetrate acts of terrorism, must be met by an equally legitimate religious force which guarantees hellfire for the same acts. Some elements of such rulings should be, inter alia:

• A call for renewal of ijtihad as the basis to reform Islamic dogmas and to relegate old dogmas to historic contexts.

• That there exists no state of jihad between Islam and the rest of the world (hence, jihad is not a personal duty).

• That the violation of the physical safety of a non-Muslim in a Muslim country is prohibited ( haram ).

• That suicide bombings are clear acts of suicide, and therefore, their perpetrators are condemned to eternal hellfire.

• That moral or financial support of acts of terrorism is also haram .

• That a legal ruling claiming jihad is a duty derived from the roots of Islam is a falsification of the roots of Islam, and therefore, those who make such statements have performed acts of heresy.

Only by setting up a clear demarcation between orthodox and radical Islam can the radical elements be exorcized. The priority of solidarity within the Islamic world plays into the hands of the radicals. Only an Islamic Kulturkampf can redraw the boundaries between radical and moderate in favor of the latter. Such a struggle must be based on an in-depth understanding of the religious sources for justification of Islamist terrorism and a plan for the creation of a legitimate moderate counterbalance to the radical narrative in Islam. Such an alternative narrative should have a sound base in Islamic teachings, and its proponents should be Islamic scholars and leaders with wide legitimacy and accepted credentials. 11 The “Middle-Easternization” of Asian Muslim communities should also be checked.

A strategy to cope with radical Islamic ideology cannot take shape without a reinterpretation of Western concepts of the boundaries of the freedoms of religion and speech, definitions of religious incitement, and criminal culpability of religious leaders for the acts of their flock as a result of their spiritual influence. Such a reinterpretation impinges on basic principles of Western civilization and law. Under the circumstances, it is the lesser evil.

1 “If the disbelievers occupy a territory belonging to the Muslims, it is incumbent upon the Muslims to drive them out, and to restore the land back to themselves; Spain had been a Muslim territory for more than eight hundred years, before it was captured by the Christians. They [i.e., the Christians] literally, and practically wiped out the whole Muslim population. And now, it is our duty to restore Muslim rule to this land of ours. The whole of India, including Kashmir, Hyderabad, Assam, Nepal, Burma, Behar, and Junagadh was once a Muslim territory. But we lost this vast territory, and it fell into the hands of the disbelievers simply because we abandoned Jihad. And Palestine, as is well-known, is currently under the occupation of the Jews. Even our First Qibla, Bait-ul-Muqaddas is under their illegal possession.” — Jihaad ul-Kuffaari wal-Munaafiqeen .

2 This is characterized by the emphasis on verses in the Koran and stories extolling martyrdom (“Why do you cling to this world when the next world is better?”) and praising the virtues of paradise as a real and even sensual existence.

3 This is a rather specious argument. In all occurrences of the concept in traditional Islamic texts — and more significantly in the accepted meaning for the great majority of modern Muslims — the term means a divinely ordained war.

4 A frequently quoted verse “proving” the inadequacy of human conscience in regard to matters of jihad is Koran 2:216: “Fighting is ordered for you even though you dislike it and it may be that you dislike a thing that is good for you and like a thing that is bad for you. Allah knows but you do not know.”

5 The following list of questions has been gleaned from a large corpus of fatwas collected by the author over recent years. The fatwas represent the questions of lay Muslims and responses of scholars from different countries. Some of the fatwas were written and published in mosques, others in the open press, and others in dedicated sites on the internet.

6 This claim, a favorite of modernists and moderates, comes from a unique and unconfirmed hadith which states: “The Prophet returned from one of his battles, and thereupon told us, ‘You have arrived with an excellent arrival, you have come from the Lesser Jihad to the Greater Jihad — the striving of a servant [of Allah] against his desires.’’

7 Some Islamic judicial schools add to the Dar al-Islam/Dar al-Harb dichotomy a third category: Dar al-’Ahad , countries which have peace treaties with Muslims and therefore are not to be attacked. The basis for discerning whether or not a country belongs to Dar al-Islam is not agreed upon. Some scholars claim that as long as a Muslim can practice his faith openly, the country is not Dar al-Harb .

8 It should be noted that in the historic paradigms of “suicide” terror, which are used as authority for justification of such attacks, the martyr did not kill himself but rather placed himself in a situation in which he would most likely be killed. Technically, therefore, he did not violate the Koranic prohibition on a Muslim taking his own life. The targets of the suicide terrorist of ancient times were also quite different — officials of the ruling class and armed (Muslim) enemies. The modern paradigm of suicide bombing called for renewed consideration of this aspect.

9 The prominent fundamentalist Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, for example, gave a fatwa obliging Muslims to fund jihad out of money collected for charity ( zakat ). ( Fatwa from April 11, 2002 in Islamonline.)

10 True, religions are naturally conservative and slow to change. Religious reforms are born and legitimized through the authority of a supreme spiritual leader (a pope or imam), an accepted mechanism of scholarly consensus (Talmud, the ijma’ of the schools of jurisprudence in early Islam), internal revolution (Protestantism), or external force (the destruction of the Second Temple in Judaism). Islam canonized itself in the tenth century and therefore did not go through any of these “reforms.”

11 Here the pessimist may inject that, today, all the leading Islamic scholars in the Middle East who enjoy such prestige are in the radical camp. But there have been cases of “repentant” radicals (in Egypt) who have retracted (albeit in jail and after due “convincing”) their declarations of takfir against the regime. In Indonesia, the moderate Nahdlatul Ulama led by former President Abdurahman Wahid represents a genuine version of moderate Islam.

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

Reformulating the Battle of Ideas: Understanding the Role of Islam in Counterterrorism Policy

Subscribe to the center for middle east policy newsletter, rashad hussain and rashad hussain u.s. special envoy to the organization of islamic cooperation al-husein n. madhany anm al-husein n. madhany.

August 31, 2008

As the National Commission on the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks emphasized, significant progress against terrorism cannot be achieved exclusively through the use of military force. This paper argues that in order to win the “battle of ideas,” the United States government must carefully reformulate its strategy and work with the Muslim world to promote mainstream Islam over terrorist ideology. The global effort to end terrorism must be more effective in utilizing its strongest ally: Islam. There is nothing more persuasive to Muslims than Islam. If the global coalition to stop Al-Qaeda and other terrorists groups is to succeed, it must convince potential terrorists that Islam requires them to reject terrorism. As a part of this effort, this paper recommends the following:

First, rather than characterizing counterterrorism efforts as “freedom and democracy versus terrorist ideology,” policymakers should instead frame the battle of ideas as a conflict between terrorist elements in the Muslim world and Islam.

Second, policymakers should reject the use of language that provides a religious legitimization of terrorism such as “Islamic terrorism” and “Islamic extremist.” They should replace such terminology with more specific and descriptive terms such as “Al-Qaeda terrorism.”

Third, the United States should seek to build a broad and diverse coalition of partners, not limited to those who advocate Western-style democracy, and avoid creating a dichotomy between freedom and Islamic society. Such a coalition should incorporate those who may have political differences, so long as they reject terrorism.

Fourth, the United States should enlist the assistance of scholars of Islam and the Muslim world to determine how best to frame the mission of the global counterterrorism mission. Rather than framing the conflict as “pro-freedom” or “anti-Jihadist,” these scholars should analyze the most persuasive methods for applying Islamic law to reject terrorism.

Fifth, the United States should incorporate the Muslim community as well as scholars of Islam and of the Muslim world in the policymaking process to help craft policies that reflect a more nuanced understanding of those targeted.

Sixth, the United States should promote and distribute scholarship such as the North American Muslims Scholars’ Fatwa against Terrorism and the Aal al-Bayt Institute’s anti-terrorism rulings, which carefully analyze issues such as the use of force in Islam and conclude that terrorism must be rejected unequivocally.

Seventh, recognizing the benefit of strengthening the authoritative voices of mainstream Islam, the United States should welcome and encourage the further development of mainstream Muslim organizations and moderate institutions.

Finally, the United States should continue to promote effective economic and social reforms and to work with allies in crafting fair and peaceful resolutions to conflicts in the Middle East and in other parts of the Muslim world, as these conflicts are often the preeminent grievances fueling extremist violence.

Terrorism & Extremism

Foreign Policy

Middle East & North Africa

Center for Middle East Policy

Bruce Riedel

January 16, 2024

Itamar Rabinovich

October 24, 2023

Jeffrey Feltman, Sharan Grewal, Patricia M. Kim, Tanvi Madan, Suzanne Maloney, Amy J. Nelson, Michael E. O’Hanlon, Bruce Riedel, Natan Sachs, Natalie Sambhi, Jaganath Sankaran, Caitlin Talmadge, Andrew Yeo

October 13, 2023

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Where Terrorism Finds Support in the Muslim World

That may depend on how you define it – and who are the targets.

by Richard Wike, Pew Global Attitudes Project and Nilanthi Samaranayake, Pew Research Center for the People & the Press

What produces terrorists and what conditions allow them to multiply in number and power in the Muslim world? While many studies point to the important role public opinion plays in creating an environment in which terrorist groups can flourish, relatively few works have explored survey data to measure support for terrorism among general publics. Findings from the 2005 Pew Global Attitudes survey on attitudes toward suicide bombing and civilian attacks and other measures of support for terrorism offer some revealing perspectives on this question. 1

Most notably, the survey finds that terrorism is not a monolithic concept–support for terrorist activity depends importantly on its type and on the location in which it occurs. For example, Moroccans overwhelmingly disapprove of suicide bombings against civilians, but, among respondents in the six predominantly Muslim countries surveyed, they are the most likely to see it as a justifiable tactic against Americans and other westerners in Iraq. Opinions about the United States, its attitudes in dealing with the larger world and the Iraq war are also powerful factors in shaping support for terrorism, as are perceptions that Islam is under threat. With the exception of gender, demographic differences, including income, explain little if anything about attitudes toward terrorism in the Muslim world, but country-specific differences are significant, suggesting the importance of local social, political and religious conditions.

These findings are generally though not entirely consistent with other studies of the origins and growth of Islamic terrorism. Much of the relevant literature, however, differs in its focus, concentrating instead on the motivations of terrorist organizations and their members. For example, groups may turn to suicide bombing when other strategies fail (Martha Crenshaw, 1998) or when they find themselves in competition for public support with other militant groups (Mia Bloom, 2005). Robert Pape (2003) finds that terrorism can be a “rational” strategy, pursued by groups, including secular groups, seeking territorial concessions from liberal democracies (2003). Several authors examine the link between political authoritarianism and terror. Alberto Abadie (2004) finds countries in transition from authoritarianism to democracy at a heightened risk for terrorist activities, while Gregory Gause (2005) argues that authoritarian regimes may be best equipped to stifle terrorism – he offers China as an example. Still others see support for terrorism driven in part by opposition to U.S. foreign policy. For instance, Scott Atran (2004) finds “no evidence that most people who support suicide actions hate Americans’ internal cultural freedoms, but rather every indication that they oppose U.S. foreign policies, particularly regarding the Middle East.”

Relatively few studies have addressed the public attitudes that allow terrorism to take root and grow in certain societies; those that have rely on earlier data than is provided by the 2005 Pew study. In their analysis of Lebanese Muslim attitudes, Simon Haddad and Hilal Khashan (2002) find that younger respondents and those who endorse political Islam are more likely than others to approve of the September 11 attacks. However, they find that income and education are unrelated to such opinions. Examining polling data from the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, Alan Krueger and Jitka Maleckova (2002) also conclude that, contrary to much conventional wisdom, poverty and low education are not key drivers of support for terrorism.

Similarly, in a recent study, Christine Fair and Bryan Shepherd (2006) analyze 2002 Pew Global Attitudes data and find that women, young people, computer users, those who believe Islam is under threat, and those who want religious leaders to play a larger role in politics are more likely to support suicide bombing and other attacks against civilians. Fair and Shepherd find that financial status is also a significant determinant — that the very poor are less, not more, likely to support such attacks.

What then do more recent data show?

Declining Support for Terrorism

Overall, the 2005 Pew Global Attitudes survey finds that support for terrorism has generally declined since 2002 in the six predominantly Muslim countries included in the study – Indonesia, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, and Turkey – although there are some variations across countries and survey items.

We will focus on results for three terrorism-related measures: attitudes about suicide bombing and other violence against civilians, views on suicide bombing carried out against Americans and other Westerners in Iraq, and opinions about Osama bin Laden. The first two measures were only asked of Muslim respondents. All respondents were asked their opinion of bin Laden; however, we will restrict our analysis to Muslim respondents.

The most basic measure of support for terrorism asked respondents the following question: “Some people think that suicide bombing and other forms of violence against civilian targets are justified in order to defend Islam from its enemies. Other people believe that, no matter what the reason, this kind of violence is never justified. Do you personally feel that this kind of violence is often justified to defend Islam, sometimes justified, rarely justified, or never justified?”

As Table 1 illustrates, the share of the public that believes suicide bombing and other violence is justifiable varies considerably across countries, with Jordanian Muslims significantly more likely than others to support terrorist acts. Lebanon and Pakistan form a middle tier on this question, followed by Indonesia, Turkey, and Morocco, where solid majorities say these forms of violence are never justified. In five of the six countries, support for such attacks has dropped since the last time the question was asked, although the decline in Turkey is insignificant. The lone exception is Jordan, where support has actually increased 14 points since 2002.

The most dramatic drop in support for terrorism is seen in Morocco, a country that experienced a devastating terrorist attack in May 2003. Fully 79% of Moroccans surveyed in 2005 said that support for suicide bombing and violence against civilians was never justified–more than double the percentage (38%) who had expressed this view a year earlier.

A second question asked respondents specifically about suicide bombing in Iraq: “What about suicide bombing carried out against Americans and other Westerners in Iraq? Do you personally believe that this is justifiable or not justifiable?”

Interestingly, despite the overall decline in support for terrorist acts among its citizens, Morocco is the only country in which a majority says attacks on Americans and other westerners in Iraq are justified. Roughly half of Jordanian and Lebanese Muslims support such acts, while fewer than 30% of Muslims in Pakistan, Indonesia and Turkey agree. In all four countries where trends exist, support for suicide attacks in Iraq has declined, including a large, 21-point drop in Jordan.

Finally, respondents were asked how much confidence they have in Osama bin Laden to do the right thing in world affairs. The results show support for bin Laden has declined in four of the six countries. Jordan and Pakistan are the exceptions, with the percentage of Muslims who have a lot or some confidence in bin Laden rising five points among Jordanians and six points among Pakistanis.

Independence of Terrorism Measures

It is clear that across all three measures, support for terrorism has declined generally. However, it is also clear that levels of support vary across questions, suggesting that each measures a different facet of how people view terrorism.

This can be illustrated by examining the relationship between views about suicide bombing generally and suicide bombing specifically in Iraq. As Table 4 demonstrates, in some predominately Muslim countries a significant number of people who believe that suicide bombing and other attacks against civilians are at least sometimes justifiable still do not support suicide bombing against Westerners in Iraq. For example, in Turkey among respondents who say suicide bombing is rarely, sometimes, or often justified, a 49% plurality says that suicide bombing in Iraq is not justifiable. By contrast, in Morocco 81% and in Jordan 68% of those who say targeting civilians is at least sometimes justified also find it justifiable in Iraq.

Similarly, those who believe that suicide bombing and other attacks against civilians are at least sometimes justifiable do not necessarily have confidence in Osama bin Laden. Again, results vary significantly by country, with 71% of Jordanian Muslims who believe violence against civilians can be justified also having confidence in bin Laden, compared with only 5% of Turks.

Finally, the relationship between views about suicide bombing in Iraq and views of bin Laden also differ significantly among the six countries. For instance, 82% of Jordanian Muslims who think suicide bombing in Iraq against Westerners is justifiable also have a lot or some confidence in bin Laden. However, only 6% of Lebanese in the same category also have confidence in bin Laden.

Correlates of Support for Terrorism

As noted above, differences in opinions about terrorism have been linked not only to demographic variables, notably age and gender, but also to views about Islam, democracy, and the United States. Four sets of variables are used to explore whether these patterns are significant in the 2005 survey data.

- Demographic variables – these include gender, age, education, and income, as well as whether a respondent has a child under age 18 living in the household and whether the respondent regularly uses a computer. Since measures for education and income differ across countries, for the purposes of analysis respondents are characterized as low or high education, and as low, middle, or high income.

- Views about Islam – Both the academic literature and the popular press have emphasized links between terrorism and an extremist brand of Islam. Responses to three questions are used to explore any potential relationships between opinions on religion and terrorism. The first asks respondents whether their primary identity is as a Muslim or as a citizen of their country (Jordanian, Moroccan, etc.). The second asks how important it is that Islam plays a more influential role in the world than it does now. The third asks whether the respondent thinks there are any serious threats to Islam today.

- Opinions about democracy – Two questions test these attitudes among respondents. The first asks whether democracy is a Western way of doing things that will not work in the respondent’s country or if democracy is not just for the West and would work in their country. The second asks respondents if they are more optimistic or more pessimistic these days that the Middle East will become more democratic.

- Attitudes toward the United States – In addition to a straightforward favorability question about the U.S., these measures include questions about: the extent to which the U.S. takes into account the interests of countries such as the respondent’s country when making international policy decisions; how worried, if at all, respondents are that the American military will become a threat to their country; whether the war in Iraq has made the world safer or more dangerous; and whether the U.S. government favors or opposes democracy in the respondent’s country. 2

Comparison of levels of support for the three measures of terrorism against these four sets of variables reveals a number of associations. As seen in Table 6, across all three measures, men are generally more supportive of terrorism than are women. Meanwhile, individuals with children are less supportive of suicide bombing generally, but more supportive of bin Laden. Support for terrorism is also more common among persons who identify primarily as Muslim, those who believe it is important for Islam to play an influential role on the world stage, and those who believe Islam faces serious threats.

Whether or not an individual thinks democracy is solely a Western way appears to have only modest effects on support for terrorism (it should be noted that relatively few Muslims, ranging from 12% in Morocco to 38% in Turkey, believe democracy is solely a Western form of government). On the other hand, across all three measures, those who are pessimistic about the prospects for Middle East democracy have more favorable attitudes toward terrorism.

Views about the U.S. appear strongly associated with attitudes toward terrorism, with support for terrorism higher among people who have an unfavorable opinion of the U.S., those who believe American foreign policy does not consider the interests of countries like theirs, those who are concerned that the U.S. may pose a military threat to their country, and those who believe the U.S. opposes democracy in their country.

Multivariate Analysis

Still, the question remains whether many of these variables have independent strength in explaining attitudes toward terrorism or whether they are primarily proxies for other significant variables with which they themselves are correlated. To determine whether these associations remain significant once other factors are controlled for, we conducted two types of regressions 3 including the variables described above as along with dummy variables to assess country specific effects.

As illustrated in Table 7, when other factors are controlled for, most demographic variables no longer show significant effects on opinions regarding suicide bombing and civilian attacks. However, gender remains significant in views about suicide bombing against Westerners in Iraq or confidence in bin Laden, with women less likely than men to support such bombing or the Al Qaeda leader. Income is also a significant determinant of support for bin Laden, with wealthier individuals holding a more negative view of the al Qaeda leader.

Two of the measured attitudes toward Islam also remain significant. The belief that it is important for Islam to play an influential role in the world is positively related to support for suicide bombing in Iraq and confidence in bin Laden. The perception that there are serious threats to Islam is positively associated with support for suicide bombing and other attacks against civilians, as well as suicide bombing against Westerners in Iraq. However, primarily identifying as a Muslim is not significantly related to any of the three dependent variables.

Variables measuring attitudes toward democracy show limited effects. The only instance in which either of the two democracy measures is significant is that people who believe democracy is not just a western way and can work in their country are less likely to support terrorist attacks against civilians.

By contrast, some attitudes toward the U.S. are strongly associated with views on terrorism. Support for terrorism is positively correlated with negative views of the U.S., a perception that the U.S. does not favor democracy in a respondent’s country, and a belief that the Iraq war has made the world more dangerous.

Finally, nearly all of the country indicators are significant, indicating that country specific factors have a great deal of influence on attitudes toward terrorism. 4

The results show that the variables for Jordan and Lebanon are positively related to support for attacks against civilians, while the other three countries are negatively related to this measure. In the second model, with support for suicide bombing in Iraq as the dependent variable, variables for three countries — Morocco, Lebanon, and Jordan — are positively associated with approval of suicide attacks in Iraq. Meanwhile, the Turkey variable is negatively associated with support for suicide terrorism in Iraq. Finally, in the third model Morocco is the excluded category, and Pakistanis, Jordanians, and Indonesians are found to be more supportive of bin Laden, while Lebanese and Turkish Muslims are less likely to have confidence in bin Laden.

Conclusions

The findings suggest several general conclusions about public opinion regarding terrorism in these six predominantly Muslim countries. First, the 2005 poll finds support for terrorism on the decline, although there are a few exceptions to this pattern, and support remains rather high in some countries, notably Jordan. Previous research has shown that support tends to decline among publics after they have experienced attacks on their own soil, and future research will determine whether such a drop has occurred in Jordan following the November 2005 bombings in Amman.

Second, terrorism is not a monolithic concept, and different facets of terrorism have different patterns of public support. Many individuals who say suicide bombing in defense of Islam may be justifiable do not support it in Iraq, and vice versa. 5 For example, while Moroccans are the least supportive of suicide bombing when it is described in general terms, they are the most likely to approve of suicide bombing specifically in Iraq.

Third, demographic characteristics appear to have relatively small effects on attitudes towards terrorism, with the exception of gender. Contrary to Fair and Shepherd, we find that women are generally less likely to approve of terrorist acts and are less likely to hold favorable views of Osama bin Laden.

Fourth, views about Islam are linked, to some extent, to views about terrorism. In particular, and consistent with Fair and Shepherd, we find the perception that Islam is under threat is positively correlated with support for terrorism.

Next, we find that opinions of the United States and of American foreign policy are important determinants of attitudes towards terrorism. The perception that the U.S. acts unilaterally in international affairs, concerns about the American military becoming a threat, negative views of the Iraq war, the belief that the U.S. opposes democracy in the region, and a generally unfavorable view of America all drive pro-terrorism sentiments.

Finally, the multivariate analysis finds significant country-specific effects, suggesting that conditions giving rise to terror are greatly influenced by local political, social, and religious factors. Future studies should seek to shed more light on these country specific influences, as well as the factors that shape public opinion on terrorism across nations.

A longer version of the paper was presented at the annual conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Montreal, Canada, May 18-21, 2006

Field dates for the survey, as well as the number of Muslims in each country sample are shown below.

Full wording of questions

Works Cited

Abadie, Alberto. 2004. “Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism.” Kennedy School of Government Faculty Research Working Paper Series.

Atran, Scott. 2004. “Mishandling Suicide Terrorism.” The Washington Quarterly 27: 67-90.

Bloom, Mia. 2005. Dying to Kill: the Allure of Suicide Terror . New York: Columbia University Press.

Crenshaw, Martha. 1998. “The Logic of Terrorism: Terrorist Behavior as a Product of Strategic Choice.” In Walter Reich (ed.), Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies, Theologies, States of Mind . Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Fair, C. Christine and Bryan Shepherd. 2006. “Who Supports Terrorism? Evidence from Fourteen Muslim Countries.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29: 51-74.

Gause, F. Gregory III. 2005. “Can Democracy Stop Terrorism?” Foreign Affairs 84: 62-76.

Haddad, Simon and Hilal Khashan. 2002. “Islam and Terrorism: Lebanese Muslim Views on September 11.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46: 812-828.

Krueger, Alan B. and Jitka Maleckova. 2002. “The Economics and the Education of Suicide Bombers: Does Poverty Cause Terrorism?” The New Republic June 24.

Pape, Robert A. 2003. “The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism.” American Political Science Review 97: 343-361.

- See the 2005 Pew Global Attitudes Survey for more information, including sample sizes and exact field dates. The analyses in this report are based on Muslim respondents only, except for Morocco, where a religious preference question was not asked. However, given that Morocco’s population is 99% Muslim, it is likely that nearly all of the Moroccan sample is Muslim. ↩

- The question was not asked in Turkey. ↩

- Standard OLS regression was employed for the questions regarding suicide bombing and other attacks against civilians and confidence in bin Laden and logistic regression for the question concerning whether suicide bombing against Americans and other Westerners in Iraq is justified. ↩

- To test the independent importance of the country variables, in each model the country closest to the median position on the attitude in question was excluded. As shown in Table 7, in the first and second models, Pakistan is the excluded country, and the other country dummy variables should be interpreted as in comparison to Pakistan. ↩

- This was a split form question asked of approximately half the sample. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- International Terrorism

Two Decades Later, the Enduring Legacy of 9/11

Americans see spread of disease as top international threat, along with terrorism, nuclear weapons, cyberattacks, facts on foreign students in the u.s., partisans have starkly different opinions about how the world views the u.s., globally, people point to isis and climate change as leading security threats, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Skip to content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Harvard Human Rights Journal

Perpetuating Islamophobic Discrimination in the United States: Examining the Relationship Between News, Social Media, and Hate Crimes

May 11, 2021 By

The following piece is published as an honorable mention in the Harvard Human Rights Journal’ s Winter 2021 Essay Contest. The contest, Beyond the Headlines: Underrepresented Topics in Human Rights, sought to share the work of Harvard University students with a broader audience and shed light on important issues that popular media may overlook.

Perpetuating islamophobic discrimination in the united states: examining the relationship between news, social media, and hate crimes , janna ramadan [*].

Abstract: Discrimination against minority communities and on the basis of religious identity violate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Following 9/11, the American public and greater Western world came to associate Islam and Muslim populations with terrorism. The introduction of bans on the burqa in France, oppression of Uyghur Muslim populations in China legitimized by a supposed threat of extremism, the Christchurch mosque shooting in New Zealand, and the U.S. Muslim ban display the degree to which the stereotype between Muslim populations and terrorism has permeated society, even to the level of domestic policy. Also important in perpetuating the association is the media, particularly social media.

To understand the degree to which social media influences or corroborates in the United States’ failure to secure basic human rights to its Muslim citizens and residents, this paper analyses the connection between media coverage and hate crimes in search for a predictive model and analyzes tweets to predict the average sentiment rating of tweets referring to Muslim populations or affiliated ethnic communities. The findings show no predictive relationship between media coverage and Anti-Islamic or Anti-Arab hate crimes but do predict a negative sentiment measure of tweets referring to the Muslim and affiliated communities.

Replication Materials: Data and code required to replicate analysis or further investigate claims made in this paper are accessible at https://jannaramadan.shinyapps.io/USIslamophobia/.

I. Introduction

In post-9/11 America, Muslims have been inextricably linked to terrorism in the public imagination. Americans have consumed media headlines about the Patriot Act, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, violent extremist organizations, and the Muslim ban, all perpetuating an association between Muslims and terrorism. Explicit Islamophobic comments uttered by elected representatives have implied legitimacy to these stereotypes with former President Trump stating, “I think Islam hates us.” [1] Former Congressman Steve King also famously questioned the loyalty of elected Muslim-American Congressman Keith Ellison. [2]

Religion in the United States also carries a racial designation. Despite no one racial group constituting more than 30% of the Muslim population, Muslims are racialized as a community of color. [3] At the center of Islamophobia in the United States is a convergence of racial and religious discrimination. Hate crimes against Muslims in the United States are a violation of human rights rooted in discrimination and ostracization within American institutions.

Discrimination against minority communities and on the basis of religious identity is a violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. [4] This paper seeks to investigate how media coverage of Muslims interacts with Anti-Islamic or Anti-Arab, as an affiliated ethnic community, hate crime rates and the social media rhetoric towards Muslims. It fills the gaps in existing studies on anti-Islamic hate crimes and media rhetoric complicity by centering its analysis on the United States. [5] Building on Twitter sentiment analysis on the topic of Islamophobia conducted in the United Kingdom, this project collects original data and seeks to predict the sentiment of tweets referring to Muslims and affiliated ethnic communities. [6]

Sentiment analyzing over 51,000 tweets and regressing 23 years of hate crime data on 12 years of media coverage records, this project finds that tweets containing references to Muslims, Islam, and related ethnic groups are predicted to carry a slight negative sentiment and that the frequency of media coverage of Muslims and terrorism does not predict anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes. Conclusions on the predictability of anti-South Asian hate crimes based on frequency of media coverage are not identified as the FBI does not separate anti-South Asian hate crimes from the broader anti-Asian hate crimes.

The discussion that follows has four parts: (1) current trends of hate crimes and media and social media coverage of Muslims and terrorism, (2) the design of the research project and data collection, (3) the main findings of hate crime and tweet sentiment predictability, and (4) a discussion of the broader implications of the findings and evident human rights failures of the United States regarding protection of its Muslim minority.

II. Current Trends in Hate Crimes, Search Interests, and Public Definitions of Terrorism

Findings from a 2019 report by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding found that fear of, and discrimination against, Muslims is on the rise in the United States. The trend is reflected in policy such as the Patriot Act and the 2017 Muslim Ban, which disproportionately targeted and impacted Muslim, Arab, and South Asian Americans, as well as the rise in hate crimes against Muslims and Arabs. [7]

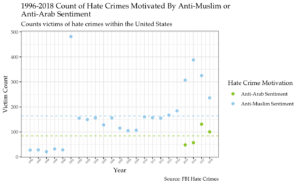

FBI hate crime data from 1995 shows a steady increase in anti-Islamic and anti-Arab motivated hate crimes (see Figure 1). [8] The dashed lines reflect the annual average number of hate crimes by motivation type. With the annual average anti-Islamic hate crime count at 163.78 hate crimes compared to the 84 annual anti-Arab hate crimes, there are more Islamophobic offenses recorded. However, note the similar trends in hate crimes. As anti-Islamic hate crimes increased between 2015 and 2016, so did anti-Arab motivated hate crimes. The parallel trend continued in the 2017-2018 hate crime decrease. Having only four years of collected anti-Arab hate crime data, the trend is not further corroborated in this project, but presents an interesting preliminary trend, reflecting conflation of Muslim and Arab identities.

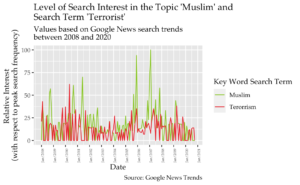

General media coverage trends on the topics of “Muslim” and “Terrorism” are garnered from Google News Trends of the United States from January 2008 to September 2020. [9] The similar “Muslim” and “Terrorism” search interest trends over a 12-year period display a clear association that reflects the American held association of Muslims and terrorism. When searches of news coverage on terrorism increase, so too do searches of news coverage on Muslims. This result reflects that internet users searching for news on Google in the United States actively search for both in tandem. This conclusion may come as a result of the searcher’s own perceptions of Islam and terrorism as related. It may also be a result of news coverage mentioning both topics, which further directs searchers to news coverage that presents terrorism as linked to Islam.

Literature on how the American public defines terrorism further corroborates the trends displayed in hate crimes and media search interests. In an experimental study, researchers synthesized scholarly definitions and public debates to create predictions for how various attributes of incidents and perpetrators affect perceptions of whether the events were acts of terrorism. [10] They found that when perpetrators were described as Muslim, subjects were significantly more likely to classify a given event as terrorism. [11] In addition, perpetrators described as carrying foreign ties and the goal of changing policy have an 82% likelihood of being deemed perpetrators of terrorism. [12] Framing of events is an impactful exercise in both initiating and entrenching stereotypes linking Muslims to terrorism.

III. Method

This paper seeks to assess hate crime trends, search interest trends, and U.S.-based tweets on a series of keywords to investigate the predictability of anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes and the predictability of tweet sentiments. [13] Each of the two predictability questions is assessed utilizing different coding methods.

Predictability of Hate Crimes

As a research project focused on Islamophobia in the United States, FBI anti-Islamic and anti-Arab hate crime records between 1995 and 2018 present quantitative counts for discriminatory action while also cataloging events by motivation. Separating anti-Islamic and anti-Arab motivated hate crimes allowed the model to distinguish between religious and ethnic identities and compare predictability rates.

Due to a lack of quantitative values for news articles featuring the keywords “Muslim” and “Terrorism” at major news institutions, news coverage on Muslims and terrorism was represented by Google News search trends, displaying aggregate interest in the topics. The search results were also filtered geographically to only reflect searches within the United States. Using Google News search trends is advantageous in that it measures search interest on the basis of topics, aggregating clicks to all available news sources and reflecting public interest and engagement with the topics. However, Google News search trends do not reflect the content nor the descriptions of Muslims and terrorism in the news articles. Thus, this measure does not reflect the type of content searchers encounter.

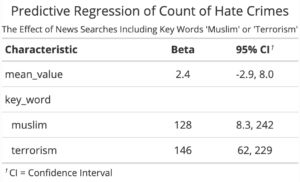

Predictability of the count of hate crimes on the basis of news searches was then determined from the base beta values and range of the confidence intervals from the following Bayesian linear regression model: Count i = β 1 x mean_value + β 2 x key_word – 1

Twitter Sentiment Analysis

Scraping Twitter for English language tweets posted from accounts based in the United States that include key word groupings of “Muslim”, “Islam”, “Arab” or “South Asian”, and “Anti-Democratic” separately from November 3, 2020 to November 17, 2020, garnered 51,873 tweets.

After de-identifying the tweets and removing “stop words” such as “I”, “being”, “have”, etc., a bing text sentiment analysis was run to determine most frequent word associations, frequent word association sentiments, and general tweet sentiment of a 10-point numerical range.

Bing text analysis measures sentiments of words in each key word dataset in descending order of frequency on a 10-point scale, with word sentiment ratings ranging from -5, extremely negative, to 5, extremely positive. Sentiment ranges were weighed by term frequency to reflect the reality of the distribution. From there the data was bootstrapped 100 times to estimate the predictability of tweet sentiments based on keywords. The methods were repeated at the aggregate level for all ethno-religious keyword terms and aggregate of all key words.

Twitter data collection occurred before, during, and immediately after the United States 2020 election which impacted coding. Words such as “vice” for Vice President are coded negatively due to vice’s alternate definition associated with intoxicants. Likewise, the coding of “trump” as a word with a positive sentiment measure is not a reflection of political beliefs, but a reflection of the definition of the word trump.

IV. Findings

The regression model of count of anti-Islamic and anti-Arab hate crimes against variables of news searches count and searched topics found no causation relationship between the two (see Figure 3). The measure of mean value of hate crimes ranges from -2.8 to 7.9. The impacts of online searches including the word “Muslim” predict hate crime counts ranging from 6.1 to 266.6, looking at the range of the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval. This trend follows on the searches including the term “Terrorism”. From the data, it cannot be concluded that frequency of searches including the words “Muslim” and “Terrorism” correlate with rises or decreases in anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes— a positive finding in light of the human rights issue of discriminatory action in the United States.

Twitter sentiment analysis led to several findings beyond the central question of sentiment predictability.

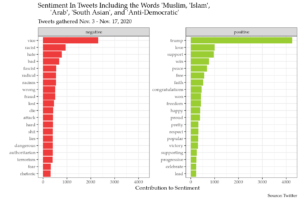

Excluding the words “vice” and “trump” due to their political meanings, comparisons of word associations to frequency, particularly for ethno-religious key words, highlight the greater frequency of negative sentiment words at the aggregate level (see Appendix A). Examining the top 20 most frequent positive and negative sentiment words, the volume of negative sentiment words is greater, particularly for the “Muslim” and “Anti-Democratic” key word and aggregate of the ethno-religious terms. Also notable was the degree of violent language referencing extremism, explicit language, authoritarianism, and death. Terrorism itself was the 18 th most frequent negative sentiment word across the ethno-religious key words aggregate dataset.