The New York Times

The Learning Network | Drawing for Change: Analyzing and Making Political Cartoons

Drawing for Change: Analyzing and Making Political Cartoons

Updated, Nov. 19, 2015 | We have now announced the winners of our 2015 Editorial Cartoon Contest here .

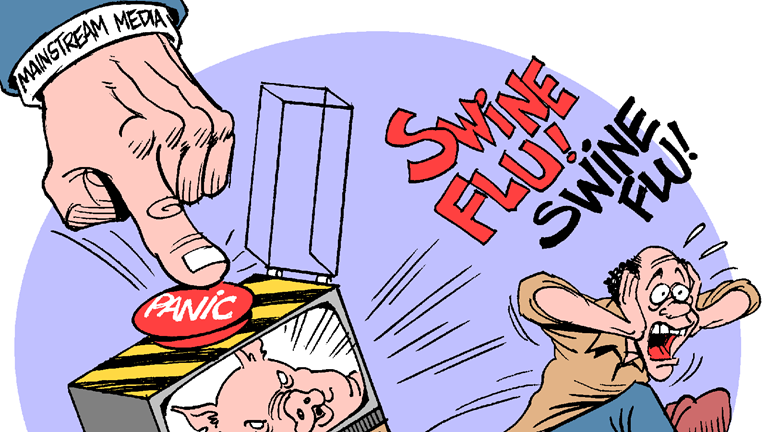

Political cartoons deliver a punch. They take jabs at powerful politicians, reveal official hypocrisies and incompetence and can even help to change the course of history . But political cartoons are not just the stuff of the past. Cartoonists are commenting on the world’s current events all the time, and in the process, making people laugh and think. At their best, they challenge our perceptions and attitudes.

Analyzing political cartoons is a core skill in many social studies courses. After all, political cartoons often serve as important primary sources, showing different perspectives on an issue. And many art, history and journalism teachers take political cartoons one step further, encouraging students to make their own cartoons.

In this lesson, we provide three resources to assist teachers working with political cartoons:

- an extended process for analyzing cartoons and developing more sophisticated interpretations;

- a guide for making cartoons, along with advice on how to make one from Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times ;

- a resource library full of links to both current and historic political cartoons.

Use this lesson in conjunction with our Editorial Cartoon Contest or with any political cartoon project you do with students.

Materials | Computers with Internet access. Optional copies of one or more of these two handouts: Analyzing Editorial Cartoons ; Rubric for our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest .

Analyzing Cartoons

While political cartoons are often an engaging and fun source for students to analyze, they also end up frustrating many students who just don’t possess the strategies or background to make sense of what the cartoonist is saying. In other words, understanding a cartoon may look easier than it really is.

Learning how to analyze editorial cartoons is a skill that requires practice. Below, we suggest an extended process that can be used over several days, weeks or even a school year. The strength of this process is that it does not force students to come up with right answers, but instead emphasizes visual thinking and close reading skills. It provides a way for all students to participate, while at the same time building up students’ academic vocabulary so they can develop more sophisticated analyses over time.

Throughout this process, you might choose to alternate student groupings and class formats. For example, sometimes students will work independently, while other times they will work in pairs or small groups. Similarly, students may focus on one single cartoon, or they may have a folder or even a classroom gallery of multiple cartoons.

Open-Ended Questioning

We suggest beginning cartoon analysis using the same three-question protocol we utilize every Monday for our “ What’s Going On in This Picture? ” feature to help students bring to the surface what the cartoon is saying:

- What is going on in this editorial cartoon?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can you find?

These simple, open-ended questions push students to look closely at the image without pressuring them to come up with a “correct” interpretation. Students can notice details and make observations without rushing, while the cyclical nature of the questions keeps sending them back to look for more details.

As you repeat the process with various cartoons over time, you may want to ask students to do this work independently or in pairs before sharing with the whole class. Here is our editorial cartoon analysis handout (PDF) to guide students analyzing any cartoon, along with one with the above Patrick Chappatte cartoon (PDF) already embedded.

Developing an Academic Vocabulary and a Keener Eye

Once students gain confidence noticing details and suggesting different interpretations, always backed up by evidence, it is useful to introduce them to specific elements and techniques cartoonists use. Examples include: visual symbols, metaphors, exaggeration, distortion, stereotypes, labeling, analogy and irony. Helping students recognize and identify these cartoonists’ tools will enable them to make more sophisticated interpretations.

The Library of Congress (PDF) and TeachingHistory.org (PDF) both provide detailed explanations of what these elements and techniques mean, and how cartoonists use them.

In addition to those resources, three other resources that can help students develop a richer understanding of a cartoon are:

- The SOAPSTone strategy, which many teachers use for analyzing primary sources, can also be used for looking at political cartoons.

- This student handout (PDF) breaks up the analysis into two parts: identifying the main idea and analyzing the method used by the artist.

- The National Archives provides a cartoon analysis work sheet to help students reach higher levels of understanding.

Once students get comfortable using the relevant academic vocabulary to describe what’s going on in a cartoon, we suggest returning to the open-ended analysis questions we started with, so students can become more independent and confident cartoon analysts.

Making an Editorial Cartoon

The Making of an Editorial Cartoon

Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times, offers advice on how to make an editorial cartoon while working on deadline.

Whether you are encouraging your students to enter our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest , or are assigning students to make their own cartoons as part of a history, economics, journalism, art or English class, the following guide can help you and your students navigate the process.

Learn from an Editorial Cartoonist

We asked Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times, to share with us how he makes an editorial cartoon on deadline, and to offer students advice on how to make a cartoon. Before watching the film above, ask students to take notes on: a) what they notice about the process of making a cartoon, and b) what advice Mr. Chappatte gives students making their own cartoons.

After watching, ask students to share what information they find useful as they prepare to make their own editorial cartoons.

Then, use these steps — a variation on the writing process — to help guide students to make their own cartoons.

Step 1 | Brainstorm: What Is a Topic or Issue You Want to Comment On?

As a professional cartoonist, Mr. Chappatte finds themes that connect to the big news of the day. As a student, you may have access to a wider or narrower range of topics from which to choose. If you are entering a cartoon into our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest, you can pick any topic or issue covered in The New York Times, which not only opens up the whole world to you, but also historical events as well — from pop music to climate change to the Great Depression. If this a class assignment, you may have different instructions.

Step 2 | Make a Point: What Do You Want to Say About Your Topic?

Once you pick an issue, you need to learn enough about your topic to have something meaningful to say. Remember, a political cartoon delivers commentary or criticism on a current issue, political topic or historical event.

For example, if you were doing a cartoon about the deflated football scandal would you want to play up the thought that Tom Brady must have been complicit, or would you present him as a victim of an overzealous N.F.L. commissioner? Considering the Republican primaries , would you draw Donald Trump as a blowhard sucking air out of the room and away from more serious candidates, or instead make him the standard- bearer for a genuine make-America-great-again movement?

You can see examples of how two cartoonists offer differing viewpoints on the same issue in Newspaper in Education’s Cartoons for the Classroom and NPR’s Double Take .

Mr. Chappatte explains that coming up with your idea is the most important step. “How do ideas come? I have no recipe,” he says. “While you start reading about the story, you want to let the other half of your brain loose.”

Strategies he suggests for exploring different paths include combining two themes, playing with words, making a joke, or finding an image that sums up a situation.

Step 3 | Draw: What Are Different Ways to Communicate Your Ideas?

Then, start drawing. Try different angles, test various approaches. Don’t worry too much about the illustration itself; instead, focus on getting ideas on paper.

Mr. Chappatte says, “The drawing is not the most important part. Seventy-five percent of a cartoon is the idea, not the artistic skills. You need to come up with an original point of view. And I would say that 100 percent of a cartoon is your personality.”

Consider using one or more of the elements and techniques that cartoonists often employ, such as visual symbols, metaphors, exaggeration, distortion, labeling, analogy and irony.

Step 4 | Get Feedback: Which Idea Lands Best?

Student cartoonists won’t be able to get feedback from professional editors like Mr. Chappatte does at The International New York Times, but they should seek feedback from other sources, such as teachers, fellow students or even family members. You certainly can ask your audience which sketch they like best, but you can also let them tell you what they observe going on in the cartoon, to see what details they notice, and whether they figure out the ideas you want to express.

Step 5 | Revise and Finalize: How Can I Make an Editorial Cartoon?

Once you pick which draft you’re going to run with, it’s time to finalize the cartoon. Try to find the best tools to match your style, whether they are special ink pens, markers or a computer graphics program.

As you work, remember what Mr. Chappatte said: “It’s easier to be outrageous than to be right on target. You don’t have to shoot hard; you have to aim right. To me the best cartoons give you in one visual shortcut everything of a complex situation; funny and deep, both light and heavy; I don’t do these cartoons every day, not even every week, but those are the best.” That’s the challenge.

Step 6 | Publish: How Can My Editorial Cartoon Reach an Audience?

Students will have the chance to publish their editorial cartoons on the Learning Network on or before Oct. 20, 2015 as part of our Student Contest. We will use this rubric (PDF) to help select winners to feature in a separate post. Students can also enter their cartoons in the Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards new editorial cartoon category for a chance to win a national award and cash prize.

Even if your students aren’t making a cartoon for our contest, the genre itself is meant to have an audience. That audience can start with the teacher, but ideally it shouldn’t end there.

Students can display their cartoons to the class or in groups. Classmates can have a chance to respond to the artist, leading to a discussion or debate. Students can try to publish their cartoons in the school newspaper or other local newspapers or online forums. It is only when political cartoons reach a wider audience that they have the power to change minds.

Where to Find Cartoons

Finding the right cartoons for your students to analyze, and to serve as models for budding cartoonists, is important. For starters, Newspaper in Education provides a new “ Cartoons for the Classroom ” lesson each week that pairs different cartoons on the same current issue. Below, we offer a list of other resources:

- Patrick Chappatte

- Brian McFadden

A Selection of the Day’s Cartoons

- Association of American Editorial Cartoonists

- U.S. News and World Report

Recent Winners of the Herblock Prize, the Thomas Nast Award and the Pulitzer Prize

- Kevin Kallaugher in the Baltimore Sun

- Jen Sorensen in The Austin Chronicle

- Tom Tomorrow in The Nation

- Signe Wilkinson in the Philadelphia Daily News

- Adam Zyglis in The Buffalo News

- Kevin Siers in The Charlotte Observer

- Steve Sack in the Star Tribune

Historical Cartoonists

- Thomas Nast

- Paul Conrad

Other Historical Cartoon Resources

- Library of Congress | It’s No Laughing Matter

- BuzzFeed | 15 Historic Cartoons That Changed The World

Please share your own experiences with teaching using political cartoons in the comments section.

What's Next

<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

Flickr user aleriy osipov, Creative Commons

- English & Literature

- Grades 9-12

- Comics & Animation

Drawing Political Cartoons How do political cartoons convey messages about current events?

In this 9-12 lesson, students will analyze cartoon drawings to create an original political cartoon based on current events. Students will apply both factual knowledge and interpretive skills to determine the values, conflicts, and important issues reflected in political cartoons.

Get Printable Version Copy to Google Drive

Lesson Content

- Preparation

- Instruction

Learning Objectives

Students will:

- Analyze visual and language clues to determine the meaning of contemporary and historical political cartoons.

- Research and gather information to plan a visual story.

- Create a political cartoon based on a current event.

Standards Alignment

National Core Arts Standards National Core Arts Standards

VA:Cr1.2.Ia Shape an artistic investigation of an aspect of present-day life using a contemporary practice of art or design.

VA:Cr3.1.Ia Apply relevant criteria from traditional and contemporary cultural contexts to examine, reflect on, and plan revisions for works of art and design in progress.

VA:Re.7.1.Ia Hypothesize ways in which art influences perception and understanding of human experiences.

VA:Re.7.2.Ia Analyze how one’s understanding of the world is affected by experiencing visual imagery.

VA:Cn11.1.Ia Describe how knowledge of culture, traditions, and history may influence personal responses to art.

MA:Re7.1.Ia Analyze the qualities of and relationships between the components, style, and preferences communicated by media artworks and artists.

MA:Re7.1.Ib Analyze how a variety of media artworks manage audience experience and create intention through multimodal perception.

MA:Cn11.1.Ia Demonstrate and explain how media artworks and ideas relate to various contexts, purposes, and values, such as social trends, power, equality, and personal/cultural identity.

Common Core State Standards Common Core State Standards

ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, using advanced searches effectively; assess the usefulness of each source in answering the research question; integrate information into the text selectively to maintain the flow of ideas, avoiding plagiarism and following a standard format for citation.

ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.8 Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, using advanced searches effectively; assess the strengths and limitations of each source in terms of the task, purpose, and audience; integrate information into the text selectively to maintain the flow of ideas, avoiding plagiarism and overreliance on any one source and following a standard format for citation.

Recommended Student Materials

Editable Documents: Before sharing these resources with students, you must first save them to your Google account by opening them, and selecting “Make a copy” from the File menu. Check out Sharing Tips or Instructional Benefits when implementing Google Docs and Google Slides with students.

- Rubric: Drawing Political Cartoons

- Vocabulary: Drawing Political Cartoons

- Political Cartoon Analysis

- PBS News Hour

- The Cartoon

- Daryl Cagle's Political Cartoon Trends

- The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists

- The Week Cartoons

- Politico Cartoons

Teacher Background

Teachers share articles or a list of media resources that are appropriate for their class in order to read current events. Teachers will need to find a variety of political cartoons, preferably displaying opposing sides of an issue. Carefully review each cartoon prior to sharing them with students. Optional articles to discuss include: How Women Broke Into the Male-Dominated World of Cartoons and Illustrations , What is a Cartoonist? , and Cartoonists - left, right, and center - have their say on Texas freeze and power outage .

Student Prerequisites

Students should have familiarity with current events and strategies for analyzing and interpreting events.

Accessibility Notes

Modify handouts, text, and utilize assistive technologies as needed. Allow extra time for task completion.

- Display a variety of cartoons about a current event that the students are familiar with as an introduction. Be sure that the cartoons represent opposing positions about the same topic. Explain to the students that political cartoons are biased because they represent the artist’s point of view, as does an editorial. They are intended to be controversial and characterized in nature. Their meaning is conveyed by both visual and verbal clues.

- Read the following quote to the class: “A cartoonist is a writer and artist, philosopher, and punster, cynic and community conscience. He seldom tells a joke and often tells the truth, which is funnier. In addition, the cartoonist is more than an asocial critic who tries to amuse, infuriate, or educate. He is also, unconsciously, a reporter and historian. Cartoons of the past leave records of their times that reveal how people lived, what they thought, how they dressed and acted, what their amusements and prejudices were, and what the issues of the day were.” (Ruff and Nelson, p. 75.)

- Tell students that they are going to analyze political cartoons and create one of their own based on a current event. Have students create a variety of political cartoons displaying contrasting viewpoints. Share the following websites with students: Daryl Cagel's Political Cartoon Trends , The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists , The Week Cartoons , GoComics , and Politico Cartoons .

- Distribute and review the resource, Vocabulary: Drawing Political Cartoons . Discuss with students some of the elements present in the cartoons: caption, caricature, symbolism, the proportional size of objects and people, and personification . Help students identify the personalities in the cartoons you have displayed and ask them what issue or event they think the cartoon is about. Ask the students what details they used to make an inference.

- Divide students into small groups. Distribute a political cartoon to each group and ask them to identify the elements and context of the cartoon. Students can utilize the following, Read, Write, Think resource to assist with the research and planning of their drawing: Political Cartoon Analysis . Teachers should encourage the class to brainstorm ideas to evoke different responses. Divergent answers should be accepted. Interpretation must be open-ended.

- Have each group summarize their political cartoon analysis. The rest of the class should have an opportunity to weigh in about whether or not they agree with the group’s analysis of the cartoon.

- Introduce print and web new resources with students to identify political topics. PBS News Hour , Newsela , NPR are examples of media organizations that share current events.

- Have students create their own political cartoon depicting their opinion about a current issue. Review the Criteria for Success: Political Cartoons resource with students and discuss examples of each criterion. Allow time for students to create their political cartoon.

- Have students share their political cartoon with the class, briefly describing the issue involved and key elements used during the cartoon-making process.

- Assess the students’ knowledge of drawing political cartoons with the Rubric: Drawing Political Cartoons .

- Have students read The Cartoon by Herb Block , one cartoonist’s take on the role played by political cartoons. Ask students: Why would Lucy, the character from Peanuts, have made a good cartoonist according to Block? What does Block mean when he says that the political cartoon is a means for “puncturing pomposity?” How do political cartoonists help “the good guys?” How do political cartoonists’ relationships with their newspapers differ? What does Block say about the “fairness” of political cartoons? What different opinions about this are held?

- Analyze the differences between cartoons and comics. Have students explore contemporary webcomics: Huda Fahmy , Alec With Pen , Aditi Mali , Brown Paperbag Comics , and Christine Rai .

Original Writer

Daniella Garran

Diane Dotson

JoDee Scissors

July 22, 2021

Related Resources

Lesson creating comic strips.

In this 3-5 lesson, students will examine comic strips as a form of fiction and nonfiction communication. Students will create original comic strips to convey mathematical concepts.

- Visual Arts

- Drawing & Painting

Lesson Cartooning Political and Social Issues

In this 6-8 lesson, students will examine political cartoons and discuss freedom of speech. They will gather and organize information about a current or past issue that makes a political or social statement and analyze the different sides. Students will plan, design, and illustrate a political cartoon that presents a position on a political or social issue.

- Social Studies & Civics

Lesson Multimedia Hero Analysis

In this 9-12 lesson, students will analyze the positive character traits of heroes as depicted in music, art, and literature. They will gain an understanding of how cultures and societies have produced folk, military, religious, political, and artistic heroes. Students will create original multimedia representations of heroes.

- Literary Arts

- Myths, Legends, & Folktales

Media Picturing the Presidency

Shadowing the president is difficult, but White House photographers must capture every moment for history

- Jobs in the Arts

Lesson Media Awareness I: The Basics of Advertising

In this 6-8 lesson, students will examine the influence of advertising from past and present-day products. Students apply design principles to illustrate a product with background and foreground. This is the first lesson designed to accompany the media awareness unit.

Lesson Media Awareness II: Key Concepts in Advertising

In this 6-8 lesson, students will continue the exploration of advertising and media awareness. Students will examine the purpose, target audience, and value of advertisements. Students will then create original, hand-drawn advertisements. This is the second lesson designed to accompany the media awareness unit.

Lesson Media Awareness III: Crossing the Finish Line

In this 6-8 lesson, students will develop and market a new children’s product. They will apply advertising design strategies to market their product. This is the third lesson designed to accompany the media awareness unit.

Article Dealing with Sensitive Themes Onstage

Staging controversial shows in school theaters presents rewards and risks. Veteran arts educators share insights about the pros and cons of such shows, and how to produce them successfully.

- Sensitive Themes

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Eric Friedman Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Connect with us!

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Capital One; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .

By using this site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions which describe our use of cookies.

Reserve Tickets

Review cart.

You have 0 items in your cart.

Your cart is empty.

Keep Exploring Proceed to Cart & Checkout

Donate Today

Support the performing arts with your donation.

To join or renew as a Member, please visit our Membership page .

To make a donation in memory of someone, please visit our Memorial Donation page .

- Custom Other

IMAGES

VIDEO