- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Diaspora

- Afrocentrism

- Archaeology

- Central Africa

- Colonial Conquest and Rule

- Cultural History

- Early States and State Formation in Africa

- East Africa and Indian Ocean

- Economic History

- Historical Linguistics

- Historical Preservation and Cultural Heritage

- Historiography and Methods

- Image of Africa

- Intellectual History

- Invention of Tradition

- Language and History

- Legal History

- Medical History

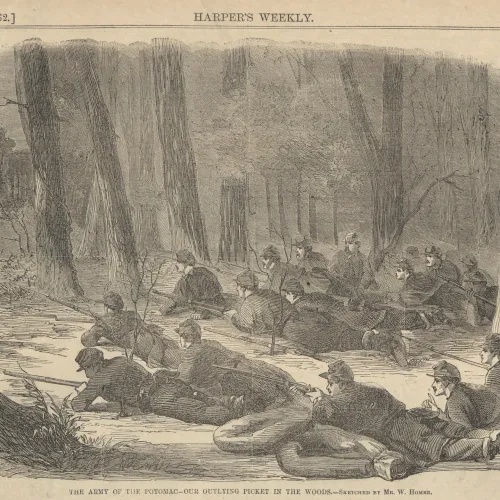

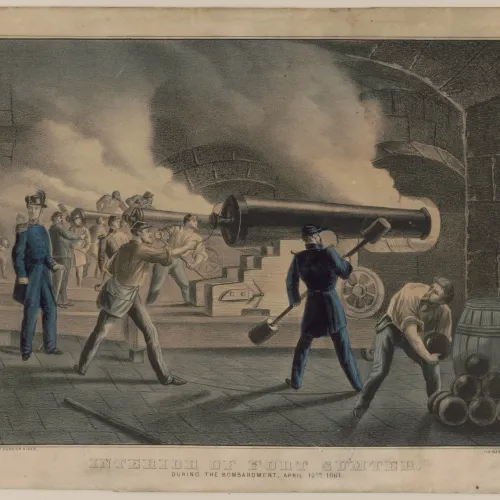

- Military History

- North Africa and the Gulf

- Northeastern Africa

- Oral Traditions

- Political History

- Religious History

- Slavery and Slave Trade

- Social History

- Southern Africa

- West Africa

- Women’s History

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

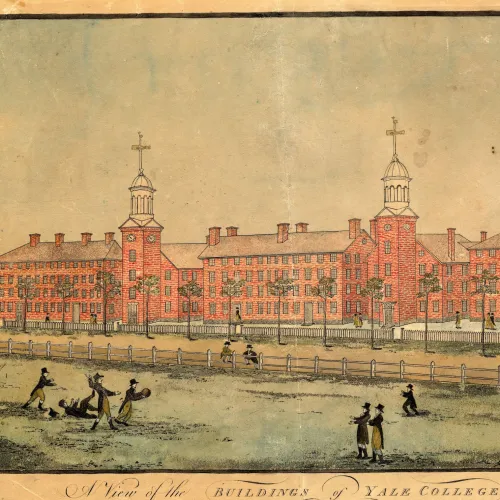

Atlantic slavery and the slave trade: history and historiography.

- Daniel B. Domingues da Silva Daniel B. Domingues da Silva History Department, Rice University

- , and Philip Misevich Philip Misevich Department of History, St. John’s University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.371

- Published online: 20 November 2018

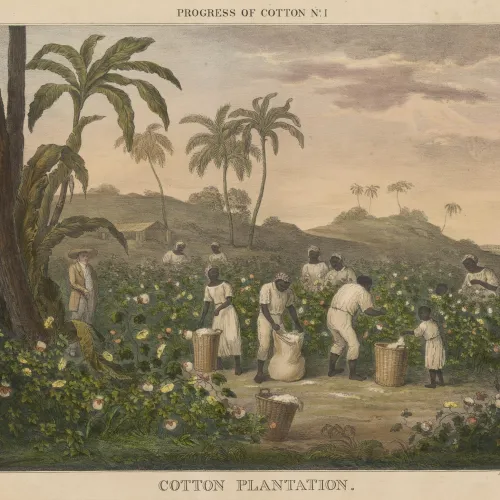

Over the past six decades, the historiography of Atlantic slavery and the slave trade has shown remarkable growth and sophistication. Historians have marshalled a vast array of sources and offered rich and compelling explanations for these two great tragedies in human history. The survey of this vibrant scholarly tradition throws light on major theoretical and interpretive shifts over time and indicates potential new pathways for future research. While early scholarly efforts have assessed plantation slavery in particular on the antebellum United States South, new voices—those of Western women inspired by the feminist movement and non-Western men and women who began entering academia in larger numbers over the second half of the 20th century—revolutionized views of slavery across time and space. The introduction of new methodological approaches to the field, particularly through dialogue between scholars who engage in quantitative analysis and those who privilege social history sources that are more revealing of lived experiences, has conditioned the types of questions and arguments about slavery and the slave trade that the field has generated. Finally, digital approaches had a significant impact on the field, opening new possibilities to assess and share data from around the world and helping foster an increasingly global conversation about the causes, consequences, and integration of slave systems. No synthesis will ever cover all the details of these thriving subjects of study and, judging from the passionate debates that continue to unfold, interest in the history of slavery and the slave trade is unlikely to fade.

- slave trade

- historiography

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, African History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 21 October 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- The Authors' Attic: Interviews with Authors

- High Impact Articles

- Award-Winning Articles

- Virtual Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why Submit?

- About Social Problems

- About the Society for the Study of Social Problems

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact SSSP

- Contact Social Problems

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Whitewashing Slavery: Legacy of Slavery and White Social Outcomes

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Robert L Reece, Whitewashing Slavery: Legacy of Slavery and White Social Outcomes, Social Problems , Volume 67, Issue 2, May 2020, Pages 304–323, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spz016

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Legacy of slavery research has branched out into an important new niche in social science research by making empirical connections between the trans-Atlantic slave trade and contemporary social outcomes. However, the vast majority of this research examines black-white inequality or black disadvantage without devoting corresponding attention to the other side of inequality: white advantage. This study expands the legacy of slavery conversation by exploring whether white populations accrue long-term benefits from slave labor. Specifically, I deploy historical understandings of racial boundary formation and theories of durable inequality to argue that white populations in places that relied more heavily on slave labor should experience better social and economic outcomes than white population in places that relied less on slave labor. I test this argument using OLS regression and county-level data from the 1860 United States Census, the 2010–2014 American Community Survey (ACS), and the 2014 United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). The results support my hypothesis. Historical reliance on slave labor predicts better white outcomes on five of six metrics. I discuss the implications of these findings for race, slavery, whiteness studies, and reparations.

Society for the Study of Social Problems members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| June 2019 | 6 |

| July 2019 | 19 |

| August 2019 | 10 |

| September 2019 | 35 |

| October 2019 | 25 |

| November 2019 | 24 |

| December 2019 | 6 |

| January 2020 | 9 |

| February 2020 | 25 |

| March 2020 | 9 |

| April 2020 | 48 |

| May 2020 | 44 |

| June 2020 | 40 |

| July 2020 | 44 |

| August 2020 | 21 |

| September 2020 | 50 |

| October 2020 | 38 |

| November 2020 | 39 |

| December 2020 | 26 |

| January 2021 | 33 |

| February 2021 | 30 |

| March 2021 | 60 |

| April 2021 | 44 |

| May 2021 | 35 |

| June 2021 | 11 |

| July 2021 | 25 |

| August 2021 | 13 |

| September 2021 | 34 |

| October 2021 | 40 |

| November 2021 | 47 |

| December 2021 | 34 |

| January 2022 | 25 |

| February 2022 | 37 |

| March 2022 | 67 |

| April 2022 | 65 |

| May 2022 | 27 |

| June 2022 | 11 |

| July 2022 | 23 |

| August 2022 | 29 |

| September 2022 | 19 |

| October 2022 | 44 |

| November 2022 | 19 |

| December 2022 | 30 |

| January 2023 | 50 |

| February 2023 | 55 |

| March 2023 | 37 |

| April 2023 | 41 |

| May 2023 | 37 |

| June 2023 | 25 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 13 |

| September 2023 | 31 |

| October 2023 | 24 |

| November 2023 | 39 |

| December 2023 | 66 |

| January 2024 | 26 |

| February 2024 | 43 |

| March 2024 | 61 |

| April 2024 | 53 |

| May 2024 | 40 |

| June 2024 | 20 |

| July 2024 | 11 |

| August 2024 | 11 |

| September 2024 | 18 |

| October 2024 | 21 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1533-8533

- Print ISSN 0037-7791

- Copyright © 2024 Society for the Study of Social Problems

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Comparative Studies in Society and History

- > Volume 63 Issue 3

- > Slavery and Its Transformations: Prolegomena for a...

Article contents

Slavery revisited, towards a new global history of slavery, defining slavery—the formal and the informal, exploring alternatives: the indian ocean and indonesian archipelago worlds, mapping trajectories of slavery regimes, a global comparative approach to trajectories of slavery regimes, towards a global comparative and connecting model, practical ways forward—on methods and sources, to conclude, slavery and its transformations: prolegomena for a global and comparative research agenda.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 June 2021

This article argues that we need to move beyond the “Atlantic” and “formal” bias in our understanding of the history of slavery. It explores ways forward toward developing a better understanding of the long-term global transformations of slavery. Firstly, it claims we should revisit the historical and contemporary development of slavery by adopting a wider scope that accounts for the adaptable and persistent character of different forms of slavery. Secondly, it stresses the importance of substantially expanding the body of empirical observations on trajectories of slavery regimes, especially outside the Atlantic, and most notable in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds, where different slavery regimes existed and developed in interaction. Thirdly, it proposes an integrated analytical framework that will overcome the current fragmentation of research perspectives and allow for a more comparative analysis of the trajectories of slavery regimes in their highly diverse formal and especially informal manifestations. Fourth, the article shows how an integrated framework will enable a collaborative research agenda that focuses not only on comparisons, but also on connections and interactions. It calls for a closer integration of the histories of informal slavery regimes into the wider body of existing scholarship on slavery and its transformations in the Atlantic and other more intensely studied formal slavery regimes. In this way, we can renew and extend our understandings of slavery's long-term, global transformations.

In public and academic domains, the history of slavery is still commonly understood through the lens of “classic” slavery in the early modern Atlantic, the nineteenth-century United States, and the Greco-Roman world. The majority of people throughout history who faced conditions of slavery, however, did not live in these classic slavery societies, but in societies with a much wider range of slavery regimes. This was the case before the abolition of the slave trade and legal slavery, especially in the early modern Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds where commercial or chattel slavery systems coexisted with a variety of other regimes. It remained the case after the abolitions, with the continuation of informal “modern” forms of slavery that today characterize the lives and working conditions of an estimated 40.3 million people, again particularly in South and Southeast Asia. Footnote 1

The focus on “classic” formal slavery has in some ways limited our understanding of the adaptable and persistent nature of slavery regimes and their trajectories of development. The definitions developed for these classical histories have reinforced the often implicit and sometimes explicit assumption that the Atlantic history of chattel slavery was largely different and isolated from the wider histories of informal and also “modern” slaveries. This has de-historicized these other, informal forms of slavery as static and unchangeable; in the words of Michael Zeuske, it has led to “smaller slaveries” being “overlaid by hegemonic slaveries” and “conceptualized as ‘special forms.’” Footnote 2 This has obscured our understanding of the wider historical trajectories of different forms of slavery as they developed across the globe. It long allowed perceptions of the history of slavery to dominate that conceptualized its development in linear fashion, from an Atlantic expansion of slave trade and slavery to “enlightened” abolitions—in short, from “unfreedom” to “freedom.”

Such linear conceptions are increasingly being critiqued by scholars who argue that we need to develop perspectives that account for the coexistence, interaction, decline, and emergence of different forms of slavery. Footnote 3 There is a growing academic awareness of the need to break away from these classical confinements in order to develop more global and encompassing approaches that can better make sense of slavery's long and complex history. Footnote 4 There have been important advances in the rich historiography of Atlantic slavery, and in the expanding scholarship on slavery and slave trades in other parts of the world, but the shift remains incomplete. Though new key concepts of slaving and availability are gaining ground, the wider field of slavery studies has been pointing toward new horizons and proclaiming new dawns more than we have actually, systematically explored them. In 2012, Michael Zeuske called for the “analysis of slavery” to “be replaced by the history of slaveries, or of actors in these slaveries, in the tradition of ‘small’ and kin slaveries, which extend up to the present.” So far, this call has not yet been taken up energetically, although we can take hope from the fact that it is apparent in the agendas of some recently developed research centers. Footnote 5 Thus, although global slavery studies stand on the shoulders of giants, from Nieboer to Patterson, in some respects we have only begun to develop a truly global and encompassing approach, one that addresses not only the enormous variety of slavery forms, but also slavery's adaptability and persistence, from earliest times to the present.

This article aims to contribute to the development of approaches that will improve our understandings of slavery as a persistent social and societal phenomenon from global and long-term perspectives. It explores what can be gained by reversing the dominant perspective, to develop an analytical framework and method that will allow us to integrate and compare the experiences of slavery “outside” of the Atlantic into a global history of slavery. That is, I argue that we need to reverse our perspective from that of the formal to that of the informal, from the Atlantic to the rest of the world, and away from binary understandings toward ones that are more connected and historical-contextual.

I will begin by examining the possibilities for, and existing perspectives on, such a global approach and engaging the crucial but often glossed-over distinction between formal and informal regimes of slavery. I then take stock of the growing body of work dealing with slavery, especially in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds, to consider what can be gained by incorporating a wider spectrum of historical “slaveries” into our analyses and (re)conceptualizations, as Zeuske has rightfully argued for. This underscores the point that in order to make sense of the highly diverse, adaptable, and persistent nature of slavery we must develop a more systematic comparative agenda that lays the basis for a consistent rethinking of slaveries’ forms and developments. A third section of the article reflects upon what we can gain from renewed comparisons to explore the many-faceted, persistent history of slavery before, after, and beyond the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The fourth and fifth sections propose contours for a global and connecting approach for this comparative endeavor. They lay out the first steps toward an analytical model for rethinking the history and presence of slavery by analyzing slavery regimes and their trajectories through both contrasting comparisons and global connections. The development of such a model requires, first, that we understand both the commonalities and the distinguishing features of different forms of coerced labor regimes, or coercive asymmetrical dependencies. Different forms or regimes did not exist in isolation, but were connected and impacted by their interactions, one of the most important of which was via slave trade—the coerced transportation of people. Secondly, we need to account for these connections by looking at interactions and external impacts. These connections, in turn, remind us that neither the classic nor the smaller slaveries were stagnant, self-contained, or unchangeable. Over time, they developed and adapted along different paths, continuously influenced, again, by their interactions. Thirdly, the focus proposed here, on trajectories of slavery regimes, can help us integrate comparative and connecting aspects with their spatial and temporal dimensions.

To enhance our understanding of slavery, we need to undertake a more inclusive, open investigation into the broader spectrum of slavery regimes. We must take an inductive approach that incorporates observations from in-depth, source-based analyses and that systematically compares slavery regimes to understand their characteristics, differences, and commonalities. We should avoid static units of analysis and top-down approaches and instead consider slavery regimes at the most localized level and in their historical contexts. We should reassemble our knowledge from the ground up by mobilizing sources and observations that provide insight into the everyday realities of how different regimes functioned and how they were enforced and challenged. The histories of these different regimes need to be scrutinized over the longue durée and through multiple time frames, while also accounting for external influences and especially how different regimes were connected and interacted.

The approach advocated here can provide a basis on which to investigate how and why local formal and informal regimes of slavery developed along specific trajectories and how these multiple trajectories influenced long-term global historical transformations of formal and especially informal forms of slavery. This will allow us to move beyond dominant models of “classic” and Atlantic histories of slavery, not by dismissing them but by inverting our academic focus in such a way that we can reassemble our knowledge of the diverse range of local cases and bridge the current divides between historiographies of slavery across the globe, especially, as emphasized in this article, in early modern South and Southeast Asia. The broader goal is to contribute to a larger breakthrough in our understanding of slavery by developing an approach to guide future research, collaboration, and comparative analysis. For the field of (global) slavery studies, the approach will shed new light on key debates about the perceived unique natures or the comparability of slaveries in the Indian Ocean and Atlantic worlds, how the slave trade transformed slavery regimes, and the heterogeneous yet global nature of slavery. Beyond these more disciplinary concerns, this is important for considering how we might push forward “global history” scholarship that navigates between deeply rooted differences in regionalized explanations and scholarly traditions and the dangers of overly top-down, flattening, or universalistic global historical approaches.

Understanding the many faces of slavery, while accounting for both the commonalities and distinguishing features of different forms of coerced labor, has been an ongoing, much-debated challenge. Such are the difficulties in creating analytical models that both differentiate and unify, that some scholars have concluded that “no single definition has succeeded in comprehending the historical varieties of slavery or in clearly distinguishing the institution from other types of involuntary servitude.” Footnote 6 It is difficult to do justice to the rich tradition of slavery scholarship over the past century and a half, but three influential models stand out.

First, in line with the work of Moses I. Finley, the five “slave societies” of ancient Greece and Rome, modern Brazil, the Caribbean, and the U.S. South have been set apart from other “societies with slaves,” based most importantly on the fundamental importance of slave labor for those economies. Footnote 7 Despite its influence, scholars have increasingly recognized that this model is too simplistic and needs reevaluation. Footnote 8 A well-developed comparative scholarship on American and classic slavery has greatly advanced insights into “the European background to Atlantic slavery” and “the novel features of Atlantic slavery's exploitative capitalist system.” Footnote 9 But it seems time to ask what happens when we take these questions beyond the horizons of the Atlantic world and formal slavery regimes. Footnote 10 For example, it has been recently argued that we should also understand “the slave-based economies in Island Southeast Asia” in terms of their “engagement with the global market [as] marked by a diversity of trajectories” in relation to colonialism and capitalism. Footnote 11

In a second influential model, the many variants of coerced labor are analyzed through the lens of the single broad category of “bondage.” Footnote 12 Its advantage is that it brings to the fore commonalities and ambiguities across the wide spectrum of slavery, bondage, and labor coercion. This approach stands alongside a third model in which different coerced-labor regimes are analyzed through contrasting comparisons, which has the advantage of drawing out differences but has often reinforced perceived dichotomies of slavery versus serfdom, or European versus Asian slaveries. Footnote 13 The difficulty here is that despite clear commonalities between varieties, differences between them clearly do matter from analytical as well as contemporary standpoints, and yet the differences are not clear-cut. Forms of slavery could extend to variations of caste and land-based slavery that, in turn, bore similarities to corvée and serfdom regimes, while all of these regimes at times allowed for hiring and selling subjects in ways comparable with commodified slavery. Footnote 14 The takeaway is that we need to move beyond perspectives that either compartmentalize or blur different forms of slavery and instead strive to understand its versatility and persistence. And this effort must consider not only the histories of regimes of formal slavery, or the “hegemonic” or “great” slavery traditions of Roman and Islamic law, but also those of the “smaller” kinship and informal slaveries across the world. Footnote 15

The renewed attention paid to the history of slavery in recent decades urges us to reconsider several divisions and gaps that have developed. Within the Atlantic, attentions have expanded beyond North America and the Caribbean to the history of slavery in Africa Footnote 16 and the multiple slavery connections and experiences in the southern Atlantic. Footnote 17 Important historiographic turns have shifted the focus to “urban” and “borderland” spaces and have encompassed broader variations in slavery, control, and resistance in the Atlantic world. Footnote 18 Scholarship on West Africa, in particular, has made two important contributions: First, it has stimulated a perspectival shift from seeing slavery as an institution to understanding slaving as a historical practice. Footnote 19 This has inspired research that tries to understand the dynamics of slavery within different contexts Footnote 20 and looks more closely at the impact, regulation, and contestation of enslavement and enslavebility. Footnote 21 Second, this scholarship has called for understandings of the impact of slave trade on local slavery regimes, and of the “trajectories” of change that slavery underwent under colonial rule and especially after abolition. Footnote 22

These advances have underscored that slavery is not a static phenomenon, and they indicate the importance of understanding not only why slavery occurred, but also, through more comparative and contextualized approaches, why specific regimes of slavery and labor coercion occurred and how these developed along different trajectories in interaction with external influences. The urgency of shifting our attention in this direction is increased by the advances made in scholarship on early modern slavery outside of the Atlantic realm. This rapidly expanding historiography indicates the existence and diverse natures of slavery and slave trade in the Mediterranean, the Islamic world, the Western Indian Ocean world, South Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Central Asia. Footnote 23 These studies also indicate that in many regions of the world formal slavery and commercial slave trading coexisted with a large variety of non-commodified and often informal forms of slavery, most importantly caste, debt, and kinship slavery. There have been important advances in expanding the scope of the global history of slavery, in increasing our understanding of the impact the slave trade had on the development of slavery, and in deconstructing the complexities of the spectrum of coerced labor. However, these advances have yet to generate a fully encompassing global-historical analytical framework that allows us to interrogate the full range of slavery regimes and their transformations and persistence.

Exploring the transformation of slavery through the trajectories of different regimes requires a clear delimitation of what we mean by slavery and slavery regimes. This article takes as starting point that slavery is defined only in part through legal systems and must be primarily understood as a practice. Footnote 24 The definition of slavery proposed here includes all coercive relations that involve formal or informal possession or usage right claims over people (or groups of people) that bind them to what contemporaries see as distinct, inferior social conditions with fewer or even no rights. Footnote 25 This contextualized definition engages with all historic forms of slavery, bringing together “the ‘great’ hegemonic slaveries” with the “most varied local ‘small’ slaveries.” Footnote 26 It also allows us to make useful distinctions between slavery and other regimes of coercion and bondage. One of these is regimes of coercion that extend to entire populations based on their subjecthood, especially corvée and labor tax regimes (though slaves could be used to perform or pay such obligations on behalf of their masters). A second type is convict labor regimes, although this distinction applies especially to societies where convicts generally retain many of their rights. The latter contrasts with societies where people lose most of their social rights, more or less permanently, and can become enslaved or slave-like through punishment.

It is important to note that this implies that different practices of slavery can coexist, interact, or conflict within the same society, Footnote 27 and that such slavery practices are regulated by sets of organizing mechanisms that together make up slavery regimes . It is useful to think about regimes as “a particular way of operating or organizing a system”—or more specifically here, about slavery and bondage as sets of social asymmetrical dependent and coercive relations—because that brings into play not only the who (actors) and what (forms) of these relations, but also how these are upheld—by what or by whom. This makes visible a distinction that is as simple as it is crucial, but nevertheless is too often overlooked in work on slavery. Slavery regimes can be either formal, meaning that they are regulated by polities such as local chiefdoms, states, and empires, or they can be informal, not meaning that they are unregulated but rather that they are regulated by “other” social entities, such as the community or households rather than by polities or formalized laws.

In contrast to what we may be inclined to think, historically these “classic” or “hegemonic” formal regimes of slavery, with their malleable but nevertheless laid down and enforced rules, provided a large degree of continuity in shaping slavery, especially because they were marked by a familial resemblance to “‘great’ slavery in a tradition of ‘Roman Law.’” Footnote 28 In contrast, the informal regimes of slavery seem more susceptible to change, more fluid and adaptable. Actors upholding such regimes, such as communities, villages, and households, are bound much less by legal norms of law and property and more by practices, customs, and expectations that can shift in the face of internal and external pressures.

It is important to mark this distinction because doing so allows us to develop a new logic for investigating the history of slavery. First, it warns against discarding informal, smaller forms of slaveries as irrelevant, non-standard, “local,” or “special.” Second, and more important, we must consider whether what shaped the nature of slavery and bondage over time was not so much the trajectories of formal slavery regimes and their abolitions, but that it was the trajectories of the more adaptable and widespread informal slavery regimes, especially, that were key factors in its transformation. Third, this implies that we cannot attribute slavery's persistence only to transformations of slavery regimes that occurred after slave trade and legalized slavery were formally abolished. In fact, the expansion and development of the pervasive and many-sided informal forms of slavery encountered today seem, to a large extent, to have taken place during the early modern expansion of commodified legal regimes of slavery and slave trading across the globe, especially in those environments where formal slavery occurred alongside and in interaction with existing local and informal slavery regimes.

What is proposed here is that we need to explore the idea that it is slavery's versatility, its capacity to transform and adapt, that explains its persistence over time. Put another way, slavery manifested itself through different formal and informal regimes, with their own trajectories, which existed and developed alongside each other. This implies that the long-term and global transformations of slavery were shaped by these multiple trajectories of slavery regimes, which did not develop in isolation but responded to external influences and each other. This was perhaps more explicit in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds than in the Atlantic, and it is no coincidence that those two regions figure most prominently in the persistence of modern forms of slavery.

The early modern Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds therefore provide a crucial arena in which to test and improve conceptualizations and understandings of the historical transformations of different forms of slavery, because these regions were marked by great diversity in the regimes of slavery, which interacted with the rapid expansion of the slave trade. Footnote 29 The history of slavery we encounter here is not entirely different from that of the Atlantic world, but it is more intertwined and integrated with aspects that were, geographically, much more distanced in the Atlantic. Throughout the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds, enslavement regions, slave-based production areas, consumer markets, and strong, developed states were mixed together in complex configurations. First, the connections forged by the long-distance slave trade were multidirectional, coercively circulating enslaved people on a large scale between Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, East Africa and South Africa, and Madagascar. Second, regions of enslavement and the export slave trade were not separated from slave importing regions by a single trans-oceanic crossing but could be located along the same coast; importing and exporting regions could be one and the same. South and Southeast Asian slavery regimes therefore offer a range of complex and nuanced manifestations of slavery forms that were connected, but also developed along different trajectories.

The myriad of slavery regimes and related forms of coerced labor has been a central theme for historiographies of societies in South and Southeast Asia. Footnote 30 Debt slavery was common throughout the Indonesian Archipelago, but also played an important role in enslavement in South India. Footnote 31 Slaves could be tied to the land in Timor Footnote 32 and on the southwest Indian Malabar coast. Footnote 33 This resembled the corvée systems in, for example, Sri Lanka, Java, and the Moluccas. Footnote 34 Caste could play a role in slavery and corvée relationships in Sri Lanka and the Malabar coast, while on Bali debt and legal punishment were reported to be prominent in enslavement. Footnote 35 Enslavement through war played a role in Bengal, Sulawesi, Bali, Java, and elsewhere. Footnote 36 Several large-scale slave raiding polities existed at different times, most notably in Arakan and Makassar in the seventeenth century Footnote 37 and, in the late eighteenth century, the Sulu Sultanate. Footnote 38

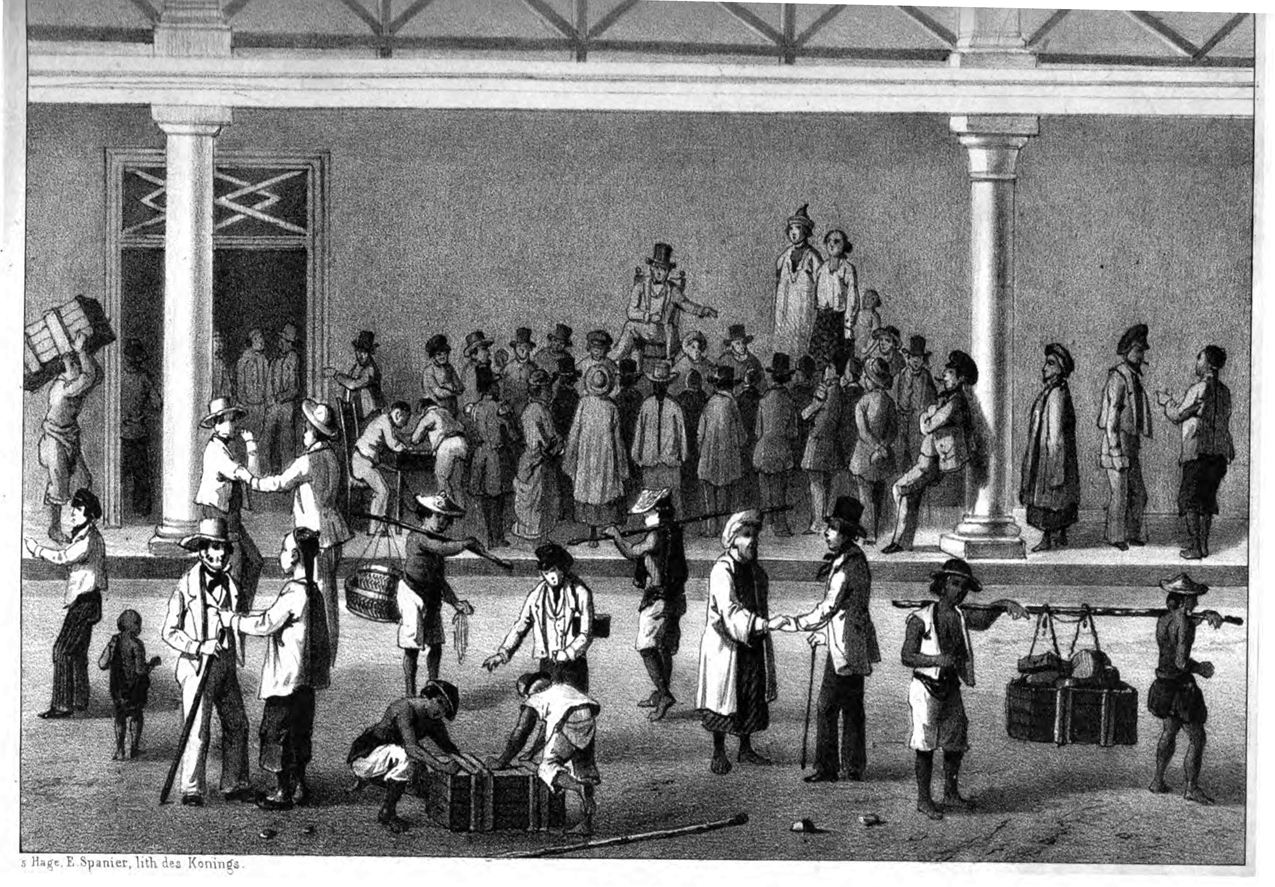

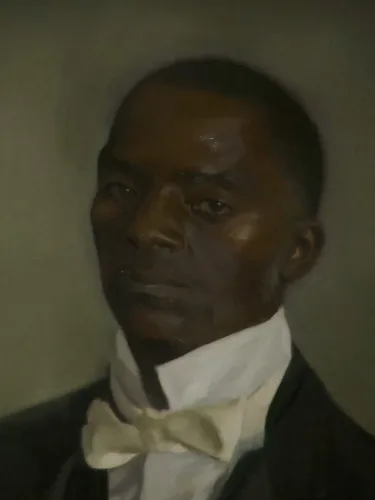

Image 1. Arakanese and Dutch slave traders in Pipli (India) in the Bay of Bengal. In Wouter Schouten, Oost-Indische Voyagie III (Amsterdam, 1676), p. 10.

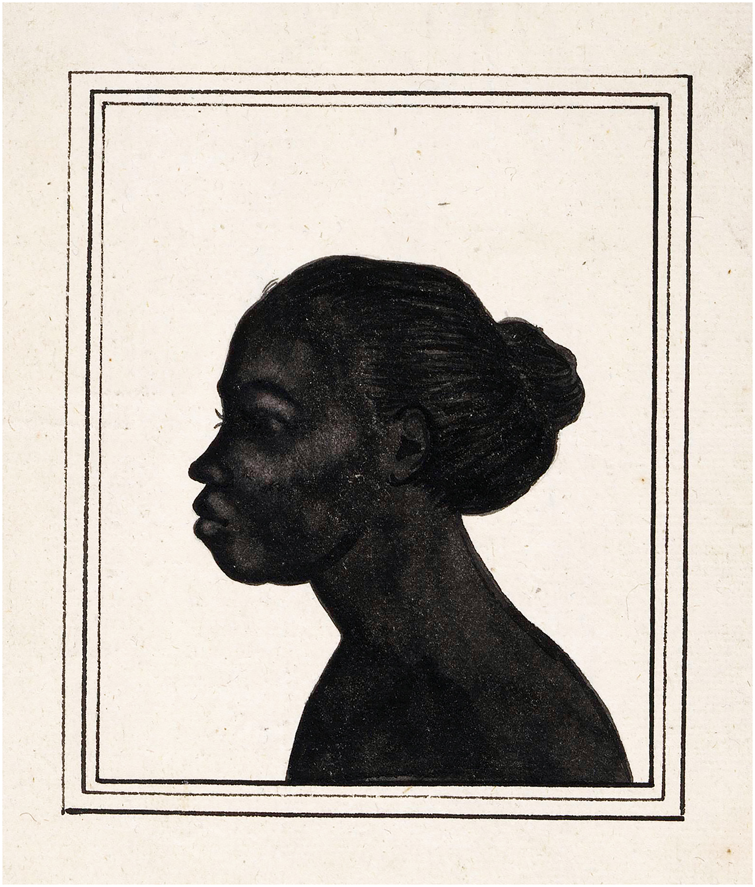

Image 2. Merchant of the Dutch East India Company with his wife, soldiers, and enslaved or captive individuals. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, SK-A-4988-00.

Recent research has begun to uncover the concurrence of widespread commercial slavery and the expansion of slave trading in the wider Indian Ocean world in the early modern period. Footnote 39 Although commercial slave trading was known to exist throughout Asia, earlier scholarship mostly disregarded it as a less important exception to the wider landscape of forms of bondage that were mainly status-based and local phenomena. Footnote 40 Explanatory models for slavery in Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian studies thus often focused on patterns of state formation that, especially in Southeast Asia, relied on collecting large followings by attracting and binding subjects, Footnote 41 or on low population density and high labor scarcity patterns, following from the “high land to labor ratio” of the Nieboer-Domar thesis. Footnote 42

Earlier research showed the importance of slavery and slave trading to the European plantation economies on the Western Indian Ocean islands, especially the French sugar plantations on the Mascarenes. Footnote 43 Later studies extended that perspective to the slave trade and slave-based production in the region more widely, and included the role of Arab and Indian merchants. Footnote 44 Moving away from the exclusive focus on the Western Indian Ocean, scholars have indicated the importance and spread of commercial slavery and slave trading in the wider Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago regions. Portuguese merchants in the Bay of Bengal “transformed from traders to slavers” in the early seventeenth century, organizing the Bengal slave trade and “supplying slaves to faraway markets in Europe, Africa, and other parts of Asia.” Footnote 45 Research into the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) archives has revealed the importance of commodified slavery in and around the VOC empire, Footnote 46 supported by large flows of slaves traded from a variety of societies throughout the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. Footnote 47 The increase of commercial slavery and slave trading in early modern South and Southeast Asia has been linked to the role of slaves in peopling cities, Footnote 48 the rise of European empires, Footnote 49 and the expansion of colonial-capitalist production for global trade. Footnote 50

With regard to colonial societies, this work has undermined dominant assumptions about so-called “Asian” forms of slavery, characterized as “mild” or even “cozy” urban household slavery, Footnote 51 and the idea that slaves in Asia were a luxury and not a production factor, mainly serving as “objects of conspicuous consumption by elites.” Footnote 52 These studies have undermined Boomgaard's argument that “if it is accepted that debt was the chief cause of enslavement, most slaves were not aliens—unless it can be proven that they were subsequently sold outside the community.” Footnote 53 Slave trading did exist on a larger scale than has been previously assumed, not only in the Western Indian Ocean but also in the wider Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago regions. Footnote 54

This should encourage the revision of perspectives on slavery and its transformations, not only in the colonial contexts, but especially outside European colonial contexts. New research shows that throughout the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago different slavery regimes coexisted and that regions sending and receiving enslaved subjects were deeply connected. Most importantly, we have important indications that slave trade and wider forms of coerced mobility created interconnections that deeply affected the trajectories of slavery regimes in both receiving and sending societies. Footnote 55

Although much more research is needed to scrutinize the dynamics of the wide variety of slavery regimes, we can already distinguish four types of regimes that are relevant to understanding the varieties of slavery regime trajectories in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago and that help us to see links with the Atlantic and the wider global history of slavery.

The Use of Conflict in Enslavement—War and Raiding Regimes

The “gun-slave cycle” is one of the most explicit links between war, enslavement, and slave trading that can be derived from the Atlantic history of the slave trade. Footnote 56 In his study of the Sulu Archipelago, Warren argues along these lines that it was the incorporation into global trading patterns in the eighteenth century's second half that stimulated slave raiding polities, and turned Jolo Island into “the most important slave center by 1800.” Footnote 57 He challenges the thesis that it was the weakening of European monopolistic trade policies that forced local polities into slave raiding and points out that “commercial and tributary activity became linked with long-distance slave raiding and incorporation of captured peoples in a system to service the procurement of trading produce.” Footnote 58 However, the late eighteenth-century transformation of the Sulu Archipelago did not stand alone. Similar links between the export slave trade and the rise of war and enslavement have been established for the Western Indian Ocean Footnote 59 and other parts of South and Southeast Asia in earlier centuries. Footnote 60 One can draw direct parallels to developments in parts of West Africa, for example in the Bight of Benin, where states such as the Kingdom of Dahomey used proceeds from slave raiding and the sale of captives to acquire goods which, in turn, were used to strengthen the polities’ power. Footnote 61

Different types of polities became involved with large-scale enslavement, varying from maritime states focused on raiding for slave exports to states involved “in the transplantation of huge population groups onto state-controlled rice plantations.” Footnote 62 The development of the Arakan Kingdom of Mrauk U in Southeast Bengal in the seventeenth century, for instance, was based strongly on its expansion of maritime slave-raiding activities and export slave trade. Footnote 63 Around the same time, the merchant polity of Makassar in politically fragmented South Sulawesi was an essential link in Southeast Asia's trading system and regional slave trade. After the conquest of the city of Makassar by the VOC, small-scale warfare and enslavement continued to provide large-scale slave exports. Footnote 64 The mainland Southeast Asian Kingdom of Ayutthaya was marked by warfare, slave capture, and large-scale resettlement, but also by the development of a corvée system imposed on populations within the polity. Footnote 65 How the impact of enslavement by war and slave raiding impacted the regimes of coercion and slavery within these respective polities, as well as in their surrounding targeted societies, should be studied and compared much more closely to understand the effects of slave raiding and war in relation to the slave trade.

European colonial expansion undeniably had an important impact in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world, not unlike the Atlantic world. The Dutch East India Company, for example, used not only glass beads but also guns and gunpowder for its slave trade in Madagascar and parts of the Indonesian archipelago. In many instances, European early modern colonial powers even acted as overlords, influencing and regulating local dynamics of war, enslavement, and slave trade. The new ruler of Buton, for example, felt it important to send an envoy to the VOC Governor General Willem van Outhoorn in January 1701 to ask his permission to export slaves to Batavia. His petition does not make explicit where these enslaved would come from, but it does hold a clue: it asks for the VOC's consent to wage war against the local rival polity of Tambako in retaliation for their having recently “attacked and conquered” several villages “and robbed all the people from there.” Footnote 66

The Shaping of Enslavebility—Local Bondage Regimes

War and slave raiding may have been the most visible forms of enslavement, but they were far from the only routes to slavery. In several regions we see distinct patterns of slavery and enslavement in relation to local socioeconomic relations of dependency grounded in oppressive differentiations. These patterns of enslavement linked to local dependencies seem to have been particularly common in the more developed market societies existing throughout South and Southeast Asia. In “idealized” form these dependencies were intended to keep bonded subjects within a society—we might call these immobilizing forms of bondage based on, for example, debt, caste, and land-bound slavery. In practice, however, this norm to keep bonded subjects within a society was continually transgressed. Footnote 67 Here again, it is worthwhile to explore interesting parallels with regional developments in West Africa, for example in the shifting use of coerced labor in the Asante Kingdom in response to external demands of slave trade. Footnote 68

The areas of southeast India (Coromandel) and southwest India (Malabar) were important slave-exporting regions, but their patterns of enslavement and slave trading seem to have been subjected to somewhat different dynamics. Poverty has traditionally been indicated as the main mode of enslavement in the Coromandel Coast, leading to practices of self- and child-selling during times of crisis. Footnote 69 At the Malabar coast, there are indications that, alongside local systems of land-based slavery, enslavement and widened transferability for the export slave trade may have been related to the adaption of local customs of caste, social expulsion, and local conflicts. Footnote 70 In Java, too, debt slavery and kidnapping were also reported to be widespread, even after the expanding VOC prohibited both the enslavement and pawning ( pandelingenschap ) of Javanese populations. Forms of bondage existed here next to systems of corvée and commercial slavery. Footnote 71 For this cluster of slavery regimes, it would be interesting to employ detailed comparison to uncover how the dynamics of internal enslavement patterns related to the impact of slave trading and trafficking networks and the export of locally enslaved or bonded people.

The issue of enslavebility—or as literally formulated in original references in Dutch sources, slaafbaarheijd —was most urgent for these societies with regimes based on largely internal processes of enslavement, perhaps even more than it was for those largely raiding or importing “aliens.” The story of the fourteen-year-old slave girl Cali from Chettuva (Kerala, southwest India) is telling in this respect. Before the Dutch Court of Justice in nearby Cochin (Kochi) she testified on 22 June 1743 that she had served “since childhood” in the house of Toepas Joan Dias within the Company's boundaries ( liemiet ), but that she was “subject and belonging to the landlord of Chettua Paijencherij Naijro.” Footnote 72 She was categorized as being of the Bettua caste, which was considered a low status group of “praedial” or land-bound slaves belonging to the owner of the land. Footnote 73 Notwithstanding the restrictions implied by her land-bound slave status, Cali worked outside the territories of the polity of the Chettuva landlord, and foresaw the danger of being sold and exported. She testified before the court that she fled the house of Dias, because she had learned “that the commander of the fort, the lieutenant Jan Doorn, had sent for her, to apprehend her, and then buy her from her lijfheer (master) the Paijencherij Naijro.” Footnote 74 Despite her land-bound status, the threat of being sold must have been serious to Cali. Various court cases from the Court of Justice of Cochin indicate that masters would threaten their male and female slaves of both local and non-local origins that they would “sell her on board” or “sell him to the scheepsvrienden (shipmates).” Slaves were frightened by the specter of losing all known social connections and entering an unknown world. In their testimonies before court, enslaved often referred to these threats as the reason for intense “sadness” and “bitter crying,” and also escape attempts. Footnote 75

Navigating in a complex, multi-sovereignty landscape, the VOC interfered with the regulation not only of who could be alienated and exported from the Malabar coast as a slave, for example through the private trade of the officers on VOC ships or via slave trade conducted by European, Indian, and Arab merchants along the coast, but also of who could actually be enslaved. Court cases on illegal abduction, deception, kidnapping, and other forms of enslavement testify to the expanding influence of colonial powers. Footnote 76 Vernacular sources are available that might provide key evidence to validate, test, and expand on the insights we can gain from deep readings of the colonial archive.

The colonial archival references to a blunt term like enslavebility ( slaafbaarheijd ) in regions such as Dutch Cochin or the wider Malabar coast highlight hard questions behind the local and imperial reshaping of slavery in societies that faced the impact of slave trade: who could be enslaved, through which means, by whom, under what conditions, and in order to make them do what? Similarly, who could be turned away from a society—sold or otherwise exported—and under what conditions? Thus, enhancing our understanding of local forms of enslavement, alienability, and the impact of the slave trade can help us better grasp the impacts these “internal inequality”-based slavery regimes had on social relations. The nineteenth-century abolitions of slave trade and slavery seem to have pushed these relations between slavery and oppressive differentiations (caste, ethnic, or racial) into the informal sphere, rather than unraveling or diminishing them.

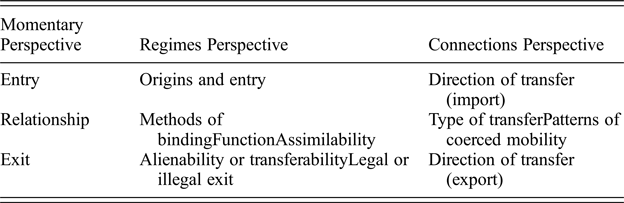

Image 3. A slave sale in nineteenth-century Batavia (Jakarta). In Wolfer Robert van Hoëvell, Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië (Batavia, 1853).

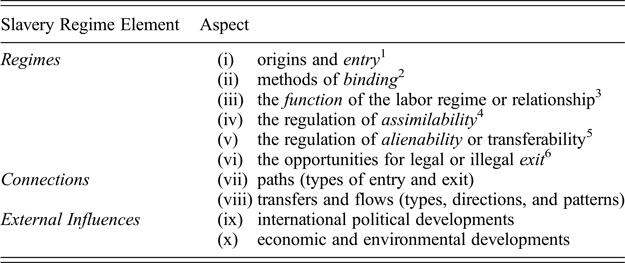

Image 4. Portrait of Flora, enslaved woman in the household of VOC-servant Jan Brandes in Batavia, ca. 1780. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, NG-1985-7-3-13.

The Shaping of Alienability—Slave-Export Regimes

Various regions developed systems in which slaves were exported on a massive scale from local slavery regimes. Whereas traders from Jolo and Macassar mainly sold “others” as slaves, most exports from these regions involved bonded or enslaved people taken directly and openly from those societies themselves. Nai or Wange Hendrik Richard van Bali described this in his unique memoires. He was the son of a free man and an enslaved mother in a village on Flores and born in the late 1790s. After his mother died he was sold to slave traders in Sumbawa (and later Java) by “the Lord and the Master.” Footnote 77 The existence of bondage, slavery, and slave trading in the Indonesian archipelago in the early modern period has been widely acknowledged, yet their interrelations have not been examined extensively, most studies having focused on local aspects of such bondage systems. Footnote 78 Some have touched on slavery, trade, and raiding in important centers of slave trading such as Jolo, Macassarm, and Bali, Footnote 79 but little attention has been paid to how local slavery regimes were transformed into large-scale export systems. The difference with the patterns of war and slave-raiding is important: in contrast to slave-export polities that sold mostly “outsiders,” people exported from Bali, Nias, and the Lesser Sunda Islands were mainly their inhabitants. The slave trade from these regions developed into large-scale export trades. For example, some 100,000 to 150,000 enslaved people are estimated to have been exported from Bali in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It has been noted that this slave trade significantly impacted the trajectories of such regimes. Bali was one of the Hindu societies of Southeast Asia, and it has been argued that slave trading strengthened existing societal hierarchies there since it “led the common people to seek the protection of a strong ruler, in spite of the fact that these were the major slave traders.” Footnote 80 Before the seventeenth century, Nias was characterized “by a closed system wherein slaves were not alienable within the society,” Footnote 81 but under the pressure of the slave trade spreading throughout the Indonesian Archipelago slaves became an important export commodity. Especially Acehnese and European slave traders and raiders increasingly drew people from Nias, which was characterized by tribal cultures.

Sources on the slave trade written by European merchants can throw light on these dynamics. An April 1688 Dutch report from the VOC ship Goudvis , for instance, narrates how the human expulsion from Nias was a trickling trade, as local kings and villagers came to the beach to sell just one, two, or three people at a time. Often these were young men or women, or people that were ill, or perhaps convicted of a crime. Within a few days, the Dutch merchants refused one male slave because he had “a large swelling above the chin (being infected)” and was “too expensive.” Footnote 82 Others were considered too “young and small for the Company” and the sellers were told that the Company “did not desire such young slaves, but some strong boys of twenty to twenty-five years old.” The sellers replied that “now they know that the Company desires large slaves, they would go forth to get slaves of such age and strength as were said.” Footnote 83 The role of local orankaijs (rulers) and villagers seems to indicate the enslaved were locals, exported based on forms of social expulsion that may have been expanded under the pressure of the demands of external slave trade. In some areas, local rulers claimed a role in regulating and profiting from this. The ship's interpreter, for example, “warned that it was a custom here, that one had to present gifts to the regents before they would grant their inhabitants permission to come with slaves, and without their consent no one was allowed to come to the beach with us.” Footnote 84 Much more research is needed on these often underdocumented societies; in many cases few local sources have been preserved, but colonial archives can play an important role. Key questions surround the dynamic interplay between local slavery, networks of commercial slave trading, and regimes that allowed a large-scale slave export trade to develop. Answering these questions will help explain local bondage and slavery export regimes and how they were transformed.

The Use of Enslaved Labor—Slave Import Regimes

It is clear that throughout the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slavery regimes existed and developed that depended primarily on import slave trade, with the enslaved being imported mostly from or via societies marked by the abovementioned categories of slavery regimes. This does not mean that those regimes were exclusively exporting slaves, because those societies also had slavery and import slave trades. In contrast, the marked characteristic of these import regime societies was their strong dependence on slave trade to sustain enslaved populations. Slavery in these import societies was primarily commodified slavery—slaves were bought and sold for the purposes of economic production, household labor, or to acquire social status. In Southeast Asia and South Asia, this could result in slave-based societies in which one-third or more of the population consisted of enslaved persons. For the colonial societies there, these are often seen as urban regimes: from Cape Town to Hugli and Calcutta, and from Malacca to Batavia. Footnote 85 Yet, in most cases, these extended into or were directly connected to rural environments that were geared toward slave-based agricultural production, such as the ommelanden of Batavia and the hinterland of the Cape. Outside the Atlantic, too, the wide variety of slave import regimes included places created around mining (e.g., in Sumatra and Java) or plantation production (e.g., Mascarenes and the Banda Islands). Footnote 86 This invites an exploration of the parallels here with slavery regimes in the Atlantic, such as in Brazil, the Guyanas, the Caribbean, and North America.

All this needs to be developed further by more source and comparative work. What, then, are the challenges for a global approach to slavery? First, our understandings and categorizations must be refined and rearranged by systematically scrutinizing historical case studies. Second, we must develop a deeper understanding of the everyday functioning of these regimes. The goal here is not to develop comparisons based on ahistorical abstractions, but to organize historical comparisons in a systematic new and open manner in order to reconceptualize things from the ground up. This inductive approach will allow us to advance the field of global slavery studies through historically localized and contextual knowledge, based on and tested by micro-historical explorations of everyday perspectives. Third, none of these local slavery regimes were isolated or self-contained; despite their differences, all related in distinct ways to external connections, perhaps most notably the slave trade. The differential impacts the trade had on local societies and their slavery regimes help explain their different trajectories.

So, we need to understand the history of the development slavery to be the interplay of all of the historical trajectories of these different, but coexisting and entangled local regimes. We therefore face the daunting task of tracing that history through a wide, comparative base of thick-description historical case studies of slavery regimes across the globe, from the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago to the Atlantic, from East Asia to Europe. Only then will we begin to understand (1) the differential impacts the slave trade had on local regimes; (2) the relations different slavery regimes had with other, non-slavery forms of coercive relations such as contract labor and corvée labor; and (3) the complex ways in which these interacted and influenced each other through competition, replacement, or transformation into new forms.

These questions are especially important to understanding slavery's afterlife and persistence. With the formal abolitions of the slave trade, and later slavery itself, labor coercion became increasingly channeled through various “other” forms of coercion, from corvée regimes organized by colonial states to coercive coolie contract labor regimes. Slavery itself did not completely disappear, but rather became increasingly less formalized, manifesting as “bondage” or what we now recognize as “modern slavery.” Throughout South and Southeast Asia, as well as in former European colonies, these transformations seem to have been masked by local variations of nineteenth-century, often colonial notions that local slaveries were “traditional,” “indigenous,” and more “benign,” conceptualizations that still haunt our understandings of slavery outside the Atlantic. They survive via not only older academic discourses but also public debate in once-colonizing countries in Europe as well as in places like Thailand, India, and Indonesia. Footnote 87 For this reason, revisiting the nature and trajectories of slavery in different parts of the world is not just important to global academic debates; it carries contemporary local and social urgency as well.

How then to proceed, if we want to better grasp how specific formal and informal slavery regimes developed across the globe, both within and outside the Atlantic, and how their multiple trajectories influenced long-term global transformations of slavery? This article contends that a breakthrough in the understanding of slavery and its persistence will require a collaborative effort, based on an approach that is both comparative and connecting, informed by new source-based studies of a broad range of cases. Developing such an inductive, connecting, and comparative global-historical approach will rely on the wealth of information that can be generated through in-depth studies of different coercive labor regimes and their dynamics, developments, and interactions. This requires that we formulate and apply a more explicit framework of interrogation to guide thick descriptions of the multitude of historical cases by providing thematic intersections through which to compare them.

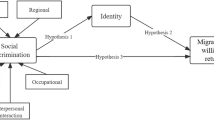

The remainder of this article provides an initial contribution toward building such a framework. My intent is not to create a top-down, universalizing mold, but rather to enable a systematic and comparative analysis of how local slavery regimes developed. Building upon existing frameworks that address different aspects of slavery and its adaptable nature ( table 1 ), our analytical model must allow for the integration of different elements of slavery regimes while it considers the role of internal and external mobility, the interactions between different regimes ( connections ), and their political-economic contexts ( external influences ). Taking together the dynamics of these regimes, their connections, and external influences ( table 2 ), we can begin to better understand the trajectories of slavery regimes and their impacts in world history.

Table 1. Existing Perspectives on Slavery and Their Aspects

Table 2. Integrated Framework for Analyzing Slavery Regime Trajectories

1 Key questions here are: What are the origins into specific regimes of bondage and enslavement? (a) What are the criteria for bondage or enslavebility? Under what conditions are people (allowed to) be bonded or enslaved? (b) What are the real, existing practices? (c) Local or non-local origin? Were people bonded before? (d) Type of entry into host society: How did people find their way into dependency—hereditary, tribute, impoverishment, sale, punishment, abduction, war, or slave raid (hereditary, commodified, political, criminal, war)?

2 Key questions: What is the method of binding. Through what mechanism or feature are the subjected tied to a master or ruler, or enslaved persons bound to a master, and on what basis (legal property, land, debt, caste, status)?

3 Key questions: What is the function or object of coercion, and the coerced labor relation? Is it social reproduction, subsistence, public (non-market production), or market-oriented (private or state)?

4 Key questions: How is the relation organized in terms of social mobility and integration into the host society? Are there specific regulations regarding assimilability and social mobility? What is the discourse or ideology, and what are the practices?

5 Key questions: How is the relation organized in terms of transferability? Is there formalization and regulation of (i.e., restriction of) transferability of subjected or bonded people? (a) What are the criteria for transferability? Under what conditions can people be transferred, and on what basis? (b) What are the real, existing practices? (c) Does this involve commodified transfers (i.e., are people sold?), or other kinds of transfer, such as tribute?

6 Key questions: What are the exits from specific regimes of bondage and enslavement? (a) Within the regime: are there exits from bondage or enslavement, such as emancipation, buying freedom, upward social mobility, or escape, and what are the routes? Are they legal or illegal? (b) Outside the regime: are there exits from society, into other regimes of bondage or enslavement (this relates to aspect v), or otherwise? Are they legal or illegal?

Despite the vast and expanding body of research into slavery and other forms of labor coercion, its historiography is still marked by “wide disagreement about the concepts needed to analyze coerced labour.” Footnote 88 The reason for this is slavery's adaptable nature. One traditional solution to this has been to confine the definition and study of slavery to a “property” relationship, where slaves are a commodity or a means of production. Although slavery has been defined in legal terms of ownership in different cultures, from Roman to Islamic, legal practices of property claims and rights are historically manifested in diverse ways and are not always clear-cut. They consist of a range of elements concerning the rights and duties of ownership, including the right to partially, fully, or exclusively possess, use, manage, exploit, punish, and transfer. Footnote 89

Even when slavery is restricted to property relations, it is clearly insufficient to reduce slavery to mere taxonomies of different relationships. Understanding it requires research into the manifestations of slavery regimes with their often-multiple claims and positions, assigned roles, norms, and regulations. Conventionally, a distinction has been made between “open” and “closed” systems, Footnote 90 where the former are based on social ties, providing opportunities for slaves to become part of the kinship structures of slave owners. In such systems, the enslaved are “outsiders who are in the process of being incorporated as kinsmen” ( assimilability ). By contrast, closed systems of hereditary slavery are rooted in institutionalized possession relationships that ensure the enslaved “remain outside the dominant kinship system,” turning them into permanent outsiders. Footnote 91 This distinction is important, but has recently been criticized because the concepts of “closed” and “open” are used in two potentially conflicting ways, referring not only to social exclusion or inclusion in slave-owning social (or kin) structures, but also to the (in)alienability of slaves. Footnote 92

Scholars of African and Asian slavery have recently advanced the slavery debate with the insight that it is crucial to consider that systems of bondage and slavery are not only about the possession of people, but more generally about the availability of people—or in essence, their bodies—for different possible purposes (obligated labor, social status, kinship, etc.). Footnote 93 Zeuske thus speaks of “slaveries” in the plural, emphasizing the different and changing manifestations of slavery that he defines, not by alienability, but by the core element of the partial or complete availability ( Verfügbarkeit ) of people's bodies. Footnote 94 The notion of availability, in turn, has inspired the development of a framework built around the function (or object) of the different coercive labor regimes of bondage, corvée, and slavery. Elsewhere I have argued that there is a distinction between the ways in which coercive regimes organized this availability of coerced labor, by either mobilizing or localizing people. Footnote 95 In this distinction, the key commonality of the many and pluriform localizing or immobilizing regimes was that they were oriented toward maintaining local orders of obligations and “unfreedom.” They were intended to keep bonded subjects inside these social or political orders, tying down people socially and spatially to their community, polity, ruler, or land (as in caste, land and debt slavery, corvée, or serfdom). This contrasts with mobilizing regimes—such as commodified or market slavery, but often also war slavery and captive slavery—in which the coercion and control of people was based on their movement across community boundaries, on their mobilizing effect. Footnote 96

A framework guiding thick descriptions of coercive labor regimes should not focus on one or the other of these viewpoints ( table 1 ) but should employ and combine the different elements underlying these different perspectives ( table 2 ). The elements of existing comparative frameworks are not mutually exclusive—they overlap and interrelate. We can identify and integrate the key elements that correspond across these approaches. The “moments” of coercion—entry, work/relationship, and exit—directly relate to pivotal elements of the open-closed dichotomy, namely the alienability of the enslaved (entry and exit) and the assimilability of the enslaved (during the relationship). The perspective of the (im)mobilizing function of regimes, in turn, focuses on the work/relationship moment, as well as the methods of binding and of organizing entry and exit. This is important to note, because it lets us overcome the scattered usage of the different existing perspectives, which illuminate different aspects of the same phenomena. In short, an inductive comparative agenda needs to bring together the key elements within a single, renewed, and open framework of inquiry that allows for thick descriptions of slavery regime case studies. The research framework provided does so by inviting the description of practices and regulations of regimes of slavery, as they are shaped by: (i) the origins and entry of the enslaved; (ii) the methods of binding the enslaved; (iii) the function of the labor relation or regime; (iv) the regulation of assimilability ; (v) the regulation of alienability or transferability ; and (vi) the opportunities for legal or illegal exit .

This framework of interrogation should be used, not for merely static or contrasting comparisons of supposedly different local variations, but rather as a tool for analyzing regime trajectories over time through integrative comparative analyses. Footnote 97 The slavery regimes of interest were not self-contained phenomena but were transformed in interactions with each other and other external influences. This means the exchange of slaves between societies was crucial in shaping local regimes, in both receiving and sending societies. Slaves moved between societies, though not always in the same way. The analytical framework therefore should not only compare, but also address connections through the paths that channeled the internal and external mobility of enslaved people, as well as the direction of the coerced mobility (sending, receiving, or both) and the type of transfer , either commodified (slave trade) or non-commodified (e.g., tribute, war, or deportation).

The connections between regimes of slavery and, most visibly, the external slave trade, influenced not only the spread of commodified and other slavery regimes, but also the wider set of internal and external political, economic, and social factors that shaped the trajectories and characters of those regimes. Footnote 98 The slave trade could, for example, lead to shifting restrictions on the transferability of enslaved subjects, as it did in Nias, Footnote 99 and the methods of controlling and binding enslaved subjects, as in Malabar, Footnote 100 but also to increasing enslavement through poverty, as in Coromandel, Footnote 101 or enslavement as legal punishment, as in Bali. Footnote 102 The impact such slave exports had on the commodification of local regimes has been extensively explored for West Africa and for the Western Indian Ocean. Footnote 103 With regard to South and Southeast Asia and elsewhere, we know fairly little about the extent of slave trading or other forms of coerced transfer or mobility, or their impact on local slavery regimes. Footnote 104

This article has called for an inductive comparative approach that incorporates and analyzes source-based observations of a multitude of case studies of slavery regimes, in relation to reconstructions and analyses of the connections or interactions forged through regional patterns of coerced mobility. The goal is to analyze different trajectories and their place within the long-term, diverse, and global development of slavery. What are the practical implications of this endeavor, and what is needed to push it forward?

First, an inductive comparative research agenda requires a multiplicity of thick descriptions of slavery regimes. Research is necessary into practices and regulations for each case, integrating multiple source-types through a method of “triangulation” that contrasts “intensive observations” with “external analyses” and “local narratives.” Second, we must account for the connections through patterns of coerced mobility for each case study region, especially via the slave trade, but including also other forms such as tribute, deportation, and war. This has already been developed for the Atlantic, but will require large efforts elsewhere, with new initiatives only recently started for the Indian Ocean, the Indonesian Archipelago, and China. Footnote 105 Third, for each case study, the wider local and regional socio-political and economic context must be accounted for. Only then can we, fourthly, begin to analyze and compare the specific trajectories of slavery regimes and their roles in the long-term global transformation of slavery.

The development of the first steps, especially—thick-descriptions of regimes of slavery, their development over time, and their relation to external impacts and connections—requires a heightened attention to methodologies, the possibilities and limitations of sources, and how best to develop thick-description case studies in largely non-European historical contexts. Let me expand on this a bit. As stated, the study of slavery and coerced-labor regimes entails exploring how social relations are shaped. The norms, institutions, and practices that shaped slavery and coercive regimes were enacted, enforced, and contested at the level of everyday life. The different key elements for thick descriptions of slavery regimes (in the integrated framework) are therefore best examined through sources that provide researchers with observations on historical everyday realities. Footnote 106 An example is court records and their rich investigations and testimonies, which can be used to explore dynamics within, for example, the realm of the Dutch Asian and Atlantic empire, Footnote 107 and even those beyond the borders of colonial societies, for example the control of enslaved people's mobility as indicative of the characteristics of different forms of slavery. Footnote 108

Unfortunately, for many societies outside of or on the fringe of European empires, like in the Indian Ocean and the Indonesian Archipelago, few quotidian written records have been preserved. Footnote 109 Many valuable local written sources from non-European societies are of course available, ranging from legal texts and contracts to chronicles and histories, but most do not record practices at this crucial level of everyday life. This lack of readily available local sources detailing the everyday dynamics of slavery and coerced labor regimes might help explain the relatively late development of academic interest in the topic, and why older assumptions with regard to the characteristics of “Asian” slavery as “mild” and “local” have remained unchallenged for so long. This demonstrates one danger of over-reliance on just one type of source: it is difficult to counterweigh its inherent biases. Like colonial records, Footnote 110 South and Southeast Asian court chronicles and legal texts cannot be considered neutral, unproblematic sources. Footnote 111

I therefore suggest a strategy of “triangulation” as a way forward that can help us to overcome these obstacles by optimizing the use of the many source types available for this region and period. This triangulation strategy should bring together and balance different types of material offering “local narratives,” “intensive observations,” and “external analyses.” In this way, we can offset the limitations of relying solely on either colonial or local sources. It has the added advantage of providing different perspectives that together can enrich and improve the thick descriptions of slavery regimes as well as the analysis of coerced mobility and the socio-political context.