Essay on Political Corruption

Students are often asked to write an essay on Political Corruption in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Political Corruption

Understanding political corruption.

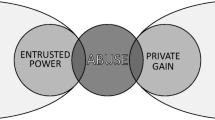

Political corruption is the misuse of public power for private gain. It includes activities like bribery, nepotism, and embezzlement. It’s a global issue affecting the development of countries.

Effects of Political Corruption

Political corruption hinders development and increases inequality. It affects public trust, leading to instability in society. It also discourages foreign investments.

Combating Political Corruption

Fighting corruption requires strong laws and transparent governance. Public awareness and participation are also crucial. With collective efforts, we can curb political corruption.

250 Words Essay on Political Corruption

Introduction.

Political corruption is a global phenomenon, deeply embedded in the socio-economic fabric of many societies. It undermines the democratic principles of nations and impedes economic development.

Manifestations of Political Corruption

Political corruption manifests in myriad ways, such as bribery, embezzlement, nepotism, cronyism, and patronage. It can also take the form of grand corruption, where high-ranking officials manipulate policies to their advantage.

Implications and Consequences

The implications of political corruption are far-reaching. It erodes public trust, hampers economic growth, and exacerbates income inequality. Moreover, it can lead to political instability and social unrest.

To combat political corruption, transparency and accountability in public administration must be promoted. Implementing stringent laws, fostering a culture of ethics, and encouraging citizen participation in governance are crucial steps.

While political corruption remains a daunting challenge, it is not insurmountable. Through collective efforts and robust institutional frameworks, societies can curb this menace and foster a climate of integrity and fairness.

500 Words Essay on Political Corruption

Political corruption is a global issue that transcends cultural, social, and economic boundaries. It refers to the misuse of public power by government officials for private gain, undermining the principles of democracy, justice, and social welfare. This essay explores the causes, implications, and potential solutions to political corruption.

Causes of Political Corruption

The roots of political corruption often lie in a complex interplay of societal, economic, and political factors. One of the primary causes is the lack of transparency and accountability in government operations. This opacity allows corrupt practices to go unnoticed and unpunished. Additionally, weak institutions and inadequate legal frameworks can provide fertile ground for corruption to thrive.

Economic factors, such as poverty and income inequality, can also contribute to political corruption. In societies with high levels of poverty and inequality, public officials may be more susceptible to bribery and embezzlement. Moreover, the concentration of power in the hands of a few can lead to the misuse of public resources for personal benefit.

Implications of Political Corruption

Political corruption has far-reaching consequences that extend beyond the immediate actors involved. It undermines democratic values by eroding public trust in government institutions. When public officials are perceived as corrupt, citizens may feel disillusioned and disengaged from the political process.

In economic terms, corruption can stifle growth and development. It diverts public resources away from essential services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure, exacerbating poverty and inequality. Furthermore, it creates an unstable business environment, discouraging domestic and foreign investments.

Solutions to Political Corruption

Addressing political corruption requires a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach. Strengthening institutional frameworks is a crucial first step. This involves implementing robust anti-corruption laws, improving governmental transparency, and fostering a culture of accountability.

Education also plays a pivotal role in combating corruption. By promoting civic education and ethical values, societies can cultivate a generation of citizens and leaders who reject corruption. Furthermore, the media and civil society organizations can act as watchdogs, exposing corrupt practices and holding officials accountable.

Lastly, international cooperation is vital in the fight against corruption. Given the global nature of corruption, countries must work together to prosecute corrupt officials, recover stolen assets, and promote good governance.

Political corruption is a pervasive issue that undermines democratic values, impedes economic development, and erodes public trust. However, through a combination of institutional reforms, education, and international cooperation, it is possible to curb corruption and promote a culture of integrity and accountability in public life. The fight against corruption is not just a legal or political challenge, but a moral one that requires the collective effort of all members of society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on How to Prevent Corruption

- Essay on Anti Corruption

- Essay on Effects of Corruption

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Political Corruption and Solutions

Introduction.

The issue of corruption has been in existence since the conception of politics as a notion. However, even if the phenomenon cannot be erased completely from modern society, it is necessary to minimize it and create a system of values that deems it as unacceptable. By introducing the modern society to a system of values based on transparency and honesty, as well as integrate innovative technology for detecting the causes of corruption at the early stages of implementing change, one will handle the problem of corruption in politics.

Problem Description

Arguably, the issue of political fraudulence exists due to imperfections in the value system that society upholds. The specified assumption has led to attributing the problem of corruption mostly to the question of morality (Gong and Ren 461). However, the specified issue should be linked to other areas in order to be resolved productively. The phenomenon of corruption in politics affects the well-being of citizens since it creates an environment in which their rights are systematically abused, and where justice principles are nonexistent. Therefore, creating tools for reducing the levels of corruption and, if possible, eradicating it completely, is necessary.

Solution to Corruption

What makes the problem of corruption so enduring is its multifaceted nature. Resolving the corruption issue implies handling the concern on several levels, including political, economic, financial, social, and technological ones (Tunley et al. 23). Several components have to be integrated into the management of the corruption-related concerns to establish a new system of fair and unbiased politics.

Abolishment of Impunity

The absence of consequences makes it excessively easy for a large number of politicians to consider the actions that they would have dismissed if facing serious legal repercussions for them. Although the legal system that places emphasis on punishing criminals instead of focusing on their rehabilitation is rather flawed, the fear of persecution is likely to restrain politicians.

Increase in Salaries

Addressing financial issues is another method of managing the problem of corruption in politics. While people taking major positions are unlikely to be concerned with the specified concept, politicians of a smaller caliber may fear possible financial complications. Therefore, ensuring that officials are provided with decent salaries is another step toward managing corruption.

Financial Transparency

Promoting clarity and openness in the political environment is currently a critical component of the general framework that will allow fighting corruption. While removing impunity is a crucial measure that will create the platform for honesty in politics, it will not provide positive results when used alone. Thus, it is critical to use it in tandem with the policy of transparency across the political arena. The integration of the concept of clarity will help to avoid the cases of fraud and the endeavors at cheating against the established system (Hansen and Flyverbom 876). Thus, the principles of transparency should be seen as the key components of the strategy for fighting against corruption in politics.

The introduction of the principles of transparency will also help to prevent instances of organized criminals entering the political field. Due to corruption and significant influence in the economic and financial areas, organized criminals have the power to become the member of the state politics (Vadlamannati and Cooray 117). Therefore, it is crucial to introduce the strategies that will create impediments for organized criminals to become important players in the political field.

With the enhancement of transparency levels in the target community, business activities will also become publically available data, which will make it virtually impossible for people involved in organized crime to gain any political power. As soon as a person or an organization with at least a slightly stained reputation endeavors at becoming a player in the political domain, their efforts will be curbed (Vadlamannati and Cooray 118). Therefore, the notion of transparency as the foundational principle for political decision-making will assist in eradicating corruption in politics.

Improved Report System

Along with the shift in the values that political figures have to uphold, a change in the reporting framework will have to occur. The proposed solution is a part of the transparency program mentioned above. With the enhancement of the reporting framework, citizens will be aware of the activities in which political figures engage. Furthermore, the information regarding finances and especially public funding will become readily available to general audiences, thus making it impossible for politicians to cheat and conceal the truth. Introducing a complaint system that will allow discovering the instances of unethical behavior among politicians, will make it possible for the cases of bribery, fraud, and other cases of financial deception in politics to be revealed.

A newly established reporting system will also require protection for the people that provide the relevant information. At the same time, it will be necessary to ensure that the specified framework is protected against slander since the data supplied anonymously may contain information fabricated intentionally to affect certain political figures negatively. Thus, the proposed reporting system will have to combine an elaborate data verification framework and the enhanced security safeguarding the rights of the people that will provide information. Although there are reasons to integrate the suggested approach into the system for preventing corruption, relying on it as the essential tool for detecting instances of financial fraud would be wrong due to the high levels of subjectivity that it contains.

Fraudulence in politics and increased levels of corruption is a reason for a major concern since the described phenomenon affects the well-being of citizens, the quality of their lives, and the overall level of their security. In order to manage the problem of increased corruption in the political environment, one has to introduce a program combining increased transparency and an enhanced system of reporting the incidents of political corruption. The shift in the political values and principles along with a stringent system of supervision and control will help to minimize the instances of financial fraud and other types of corruption in politics.

However, it is also recommended to ensure that the reporting system that will comprise an important part of a new framework for managing political fraud should be based on a critical assessment of the submitted claims. Thus, one will avoid the cases in which slander may be used against political figures to benefit their opponents. The proposed solution to corruption should incorporate an improved system of values that will imply a people-oriented approach and reinforce the significance of ethical decision-making in the political context.

Thus, the process of supervision will be balanced with careful scrutiny of the facts submitted as evidence. With a detailed analysis of the available information, ethical standards geared toward meeting the needs of citizens, and a well-thought-out platform for decision-making, the current levels of corruption in politics will finally be curbed.

Works Cited

Gong, Ting, Shiru Wang, and Jianming Ren. “Corruption in the Eye of the Beholder: Survey Evidence from Mainland China and Hong Kong.” International Public Management Journal , vol. 18, no. 3, 2015, pp. 458-482.

Hansen, Hans Krause, and Mikkel Flyverbom. “The Politics of Transparency and the Calibration of Knowledge in the Digital Age.” Organization, vol. 22, no. 6, 2015, pp. 872-889.

Tunley, Martin, et al. “Preventing Occupational Corruption: Utilising Situational Crime Prevention Techniques and Theory to Enhance Organisational Resilience.” Security Journal , vol. 31, no. 1, 2018, pp. 21-52.

Vadlamannati, Krishna Chaitanya, and Arusha Cooray. “Transparency Pays? Evaluating the Effects of the Freedom of Information Laws on Perceived Government Corruption.” The Journal of Development Studies , vol. 53, no. 1, 2017, pp. 116-137.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, June 8). Political Corruption and Solutions. https://studycorgi.com/political-corruption-and-solutions/

"Political Corruption and Solutions." StudyCorgi , 8 June 2021, studycorgi.com/political-corruption-and-solutions/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Political Corruption and Solutions'. 8 June.

1. StudyCorgi . "Political Corruption and Solutions." June 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/political-corruption-and-solutions/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Political Corruption and Solutions." June 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/political-corruption-and-solutions/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Political Corruption and Solutions." June 8, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/political-corruption-and-solutions/.

This paper, “Political Corruption and Solutions”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 11, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The causes and effects of corruption, and how to combat corruption, are issues that have been very much on the national and international agendas of politicians and other policymakers in recent decades (Heidenheimer and Johnston 2002; Heywood 2018). Moreover, various historically influential philosophers, notably Plato ( The Republic ), Aristotle ( The Politics ), Machiavelli ( The Prince and The Discourses ), Hobbes ( The Leviathan ) and Montesquieu ( The Spirit of the Laws ), have concerned themselves with political corruption in particular, albeit in somewhat general terms (Sparling 2019; Blau 2009). For these philosophers corruption consisted in large part in rulers governing in the service of their own individual or collective—or other factional—self-interest, rather than for the common good and in accordance with the law or, at least, in accordance with legally enshrined moral principles. They also emphasized the importance of virtues, where it was understood that the appropriate virtues for rulers might differ somewhat from the appropriate virtues for citizens. Indeed, Machiavelli, in particular, famously or, perhaps, infamously argued in The Prince that the rulers might need to cultivate dispositions, such as ruthlessness, that are inconsistent with common morality. [ 1 ] And Plato doubted that the majority of people were even capable of possessing the requisite moral and intellectual virtues required to play an important role in political institutions; hence his rejection in The Republic of democracy in favor of rule by philosopher-kings. Moreover, these historically important political philosophers were concerned about the corruption of the citizenry: the corrosion of the civic virtues. This theme of a corrupt citizenry, as opposed to a corrupt leadership or institution, has been notably absent in contemporary philosophical discussion of the corruption of political institutions until quite recently. However, recently the corruption of political institutions and of the citizenry as a consequence of the proliferation of disinformation, propaganda, conspiracy theories and hate speech on social media, in particular (Woolley and Howard 2019), has become an important phenomenon which philosophers have begun to address (Lynch 2017; Cocking and van den Hoven 2018; Miller and Bossomaier 2023: Ch. 4). Social media bots are used inter alia to automatically generate disinformation (as well as information), propagate ideologies (as well as non-ideologically based opinions), and function as fake accounts to inflate the followings of other accounts and to gain followers. The upshot is that the moral right of freedom to communicate has frequently not been exercised responsibly; moral obligations to seek and communicate truths rather than falsehoods have not been discharged, resulting in large-scale social, political and, in some cases, physical harm. One key set of ethical issues here pertains to an important form of institutional corruption: corruption of the democratic process. For instance, revelations concerning the data firm Cambridge Analytica’s illegitimate use of the data of millions of Facebook users to influence elections in the U.S. and elsewhere highlighted the ethical issues arising from the use of machine learning techniques for political purposes by malevolent foreign actors. The problem here is compounded by home-grown corruption of democratic institutions by people who wilfully undermine electoral and other institutional processes in the service of their own political and personal goals. For instance, Donald Trump consistently claimed, and continues to claim, that the 2020 U.S. presidential election which he demonstrably lost involved massive voter fraud. The problem has also been graphically illustrated in the U.S. by the rise of home-grown extremist political groups fed via social media on a diet of disinformation, conspiracy theories, hate speech, and propaganda; a process which led to the violent attack in January 2021 on the Capitol building which houses the U.S. Congress.

In the modern period, in addition to the corruption of political institutions, the corruption of other kinds of institutions, notably market-based institutions, has been recognised. For example, the World Bank (1997) some time back came around to the view that the health of economic institutions and progress in economic development is closely linked to corruption reduction. In this connection there have been numerous anti-corruption initiatives in multiple jurisdictions, albeit this is sometimes presented as politically motivated. Moreover, the Global Financial Crisis and its aftermath have revealed financial corruption, including financial benchmark manipulation, and spurred regulators to consider various anti-corruption measures by way of response (Dobos, Pogge and Barry 2011). And in recent decades there have been ongoing efforts to analyze and devise means to combat corruption in in police organizations, in the professions, in the media, and even in universities and other research-focused institutions.

While contemporary philosophers, with some exceptions, have been slow to focus on corruption, the philosophical literature is increasing, especially in relation to political corruption (Thompson 1995; Dobel 2002; Warren 2006; Lessig 2011; Newhouse 2014; Philp and David-Barrett 2015; Miller 2017; Schmidtz 2018; Blau 2018; Philp 2018; Thompson 2018; Sparling 2019; Ceva & Ferretti 2021). For instance, until relatively recently the concept of corruption had not received much attention, and much of the conceptual work on corruption had consisted in little more than the presentation of brief definitions of corruption as a preliminary to extended accounts of the causes and effects of corruption and the ways to combat it. Moreover, most, but not all, of these definitions of corruption were unsatisfactory in fairly obvious ways. However, recently a number of more theoretically sophisticated definitions of corruption and related notions, such as bribery, have been provided by philosophers. Indeed, philosophers have also started to turn their minds to issues of anti-corruption, e.g., anti-corruption systems (often referred to as “integrity systems”), and in doing so theorizing the sources of corruption and the means to combat it.

1. Varieties of Corruption

2.1.1 personal corruption and institutional corruption, 2.1.2 institutional corrosion and structural corruption, 2.1.3 institutional actors and corruption, 2.2 causal theory of institutional corruption, 2.3.1 proceduralist theories of political corruption, 2.3.2 thompson: individual versus institutional corruption, 2.3.3 lessig’s dependence corruption, 2.3.4 ceva & ferretti: office accountability, 3. noble cause corruption, 4. integrity systems, 5. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

Consider one of the most popular of the standard longstanding definitions, namely, “Corruption is the abuse of power by a public official for private gain”. [ 2 ] No doubt the abuse of public offices for private gain is paradigmatic of corruption. But when a bettor bribes a boxer to “throw” a fight this is corruption for private gain, but it need not involve any public office holder; the roles of boxer and bettor are usually not public offices.

One response to this is to distinguish public corruption from private corruption, and to argue that the above definition is a definition only of public corruption. But if ordinary citizens lie when they give testimony in court, this is corruption; it is corruption of the criminal justice system. However, it does not involve abuse of a public office by a public official. And when police fabricate evidence out of a misplaced sense of justice, this is corruption of a public office, but not for private gain.

In the light of the failure of such analytical-style definitions it is tempting to try to sidestep the problem of providing a theoretical account of the concept of corruption by simply identifying corruption with specific legal and/or moral offences. However, attempts to identify corruption with specific legal/moral offences are unlikely to succeed. Perhaps the most plausible candidate is bribery; bribery is regarded by some as the quintessential form of corruption (Noonan 1984; Pritchard 1998; Green 2006). But what of nepotism (Bellow 2003)? Surely it is also a paradigmatic form of corruption, and one that is conceptually distinct from bribery. The person who accepts a bribe is understood as being required to provide a benefit to the briber, otherwise it is not a bribe; but the person who is the beneficiary of an act of nepotism is not necessarily understood as being required to return the favor.

In fact, corruption is exemplified by a very wide and diverse array of phenomena of which bribery is only one kind, and nepotism another. Paradigm cases of corruption include the following. The commissioner of taxation channels public monies into his personal bank account, thereby corrupting the public financial system. A political party secures a majority vote by arranging for ballot boxes to be stuffed with false voting papers, thereby corrupting the electoral process. A police officer fabricates evidence in order to secure convictions, thereby corrupting the judicial process. A number of doctors close ranks and refuse to testify against a colleague who they know has been negligent in relation to an unsuccessful surgical operation leading to loss of life; institutional accountability procedures are thereby undermined. A sports trainer provides the athletes he trains with banned substances in order to enhance their performance, thereby subverting the institutional rules laid down to ensure fair competition (Walsh and Giulianotti 2006). It is self-evident that none of these corrupt actions are instances of bribery.

Further, it is far from obvious that the way forward at this point is simply to add a few additional offences to the initial “list” consisting of the single offence of bribery. Candidates for being added to the list of offences would include nepotism, police fabricating evidence, cheating in sport by using drugs, fraudulent use of travel funds by politicians, and so on. However, any such list needs to be justified by recourse to some principle or principles. Ultimately, naming a set of offences that might be regarded as instances of corruption does not obviate the need for a theoretical, or quasi-theoretical, account of the concept of corruption.

As it happens, there is at least one further salient strategy for demarcating the boundaries of corrupt acts. Implicit in much of the literature on corruption is the view that corruption is essentially a legal offence, and essentially a legal offence in the economic sphere. Accordingly, one could seek to identify corruption with economic crimes, such as bribery, fraud, and insider trading.

But many acts of corruption are not unlawful. Bribery, a paradigm of corruption, is a case in point. Prior to 1977 it was not unlawful for U.S. companies to offer bribes to secure foreign contracts; indeed, elsewhere such bribery was not unlawful until much later. [ 3 ] So corruption is not necessarily unlawful. This is because corruption is not at bottom simply a matter of law; rather it is fundamentally a matter of morality.

Secondly, corruption is not necessarily economic in character. An academic who plagiarizes the work of others is not committing an economic crime or misdemeanor; and she might be committing plagiarism simply in order to increase her academic status. There might not be any financial benefit sought or gained.

We can conclude that many of the historically influential definitions of corruption, as well as attempts to circumscribe corruption by listing paradigmatic offences, fail. They fail in large part because the class of corrupt actions comprises an extremely diverse array of types of moral and legal offences undertaken in a wide variety of institutional contexts including, but by no means restricted to, political and economic institutions.

However, in recent times progress has been made. Philosophers, at least, have identified corruption as fundamentally a moral, as opposed to legal, phenomenon. Acts can be corrupt even though they are, and even ought to be, legal. Moreover, it is evident that not all acts of immorality are acts of corruption; corruption is only one species of immorality.

An important distinction in this regard is the distinction between human rights violations and corruption (see the entry on human rights ). Genocide is a profound moral wrong; but it is not corruption. This is not to say that there is not an important relationship between human rights violations and corruption; on the contrary, there is often a close and mutually reinforcing nexus between them (Pearson 2001; Pogge 2002 [2008]; Wenar 2016; Sharman 2017). Consider the endemic corruption and large-scale human rights abuse that have taken place in authoritarian regimes, such as that of Mobutu in Zaire, Suharto in Indonesia and Marcos in the Philippines (Sharman 2017). And there is increasing empirical evidence of an admittedly sometimes complex, but sometimes not so complex, causal connection between corruption and the infringement of both negative rights (such as the right not to be tortured, suffer arbitrary loss of one’s freedom, or have one’s property stolen) and positive rights, e.g., subsistence rights (such as the right to a sufficient supply of clean water to enable life and health); there is evidence, that is, of a causal relation between corruption and poverty. Consider corrupt authoritarian leaders in developing countries who sell the country’s natural resources cheaply and retain the profits for themselves and their families and supporters (Pogge 2002 [2008]: Chapter 6; Wenar 2016). As Wenar has forcefully argued (Wenar 2016), in the first place this is theft of the property (natural resources) of the people of the countries in question (e.g., Equatorial Guinea) by their own rulers (e.g., Obiang) and, therefore, western countries and others who import these resources are buying stolen goods; and, in the second place, this theft maintains these human rights-violating rulers in power and ensures that their populations continue to suffer in conditions of abject poverty, disease etc.

Thus far, examples of different types of corrupt action have been presented, and corrupt actions have been distinguished from some other types of immoral action. However, the class of corrupt actions has not been adequately demarcated within the more general class of immoral actions. To do so, a definition of corrupt actions is needed.

An initial distinction here is between single one-off actions of corruption and a pattern of corrupt actions. The despoiling of the moral character of a role occupant, or the undermining of institutional processes and purposes, would typically require a pattern of actions—and not merely a single one-off action. So a single free hamburger provided to a police officer on one occasion usually does not corrupt, and is not therefore an act of corruption. Nevertheless, a series of such gifts to a number of police officers might corrupt. They might corrupt, for example, if the hamburger joint in question ended up with (in effect) exclusive, round the clock police protection, and if the owner intended that this be the case.

Note here the pivotal role of habits (Langford & Tupper 1994). We have just seen that the corruption of persons and institutions typically requires a pattern of corrupt actions. More specifically, corrupt actions are typically habitual. Yet, as noted by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics , one’s habits are in large part constitutive of one’s moral character; habits make the man (and the woman). The coward is someone who habitually takes flight in the face of danger; by contrast, the courageous person has a habit of standing his or her ground. Accordingly, morally bad habits —including corrupt actions—are extremely corrosive of moral character, and therefore of institutional roles and ultimately institutions. Naturally, so-called systemic corruption would typically involve not simply the habitual performance of a corrupt action by a single individual but the habitual performance of a corrupt action by many individuals in an institution or, conceivably, an entire society or polity. Moreover, this pattern of individuals engaged in the performance of habitual corrupt actions might have a self-sustaining structure that gives rise to a collective action problem, if the pattern is to be broken. Consider widespread bribery in relation to competitive tenders for government contracts. Bribes are paid by competing companies in order to try influence the outcome of the tender process. Any firm that chooses not to pay a bribe is not given serious consideration. Thus, not to engage in corruption is to seriously disadvantage one’s company. Even those who do not want to engage in bribery do so. This is a collective action problem (Olson 1965).

Notwithstanding the habitual nature of most corrupt actions there are some cases in which a single, one-off action would be sufficient to corrupt an instance of an institutional process. Consider a specific tender. Suppose that one bribe is offered and accepted, and the tendering process is thereby undermined. Suppose that this is the first and only time that the person offering the bribe and the person receiving the bribe are involved in bribery. Is this one-off bribe an instance of corruption? Surely it is, since it corrupted that particular instance of a tendering process.

Ontologically speaking, there are different kinds of entities that can be corrupted. These include human beings, words of a language, artefacts, such as computer discs, and so on. However, our concern in this entry is with the corruption of institutions since this is the main focus of the philosophical and, for that matter, the non-philosophical, literature. Of course, institutions are comprised in large part of institutional roles occupied by human beings. So our focus on institutional corruption brings with it a focus on the corruption of individual human beings. (I refer to the corruption of individual human beings as personal corruption.) However in the case of institutional corruption, the focus on the corruption of human beings (personal corruption) is on human beings qua institutional actors (and on those who interact with institutional role occupants qua institutional role occupants)(Miller 2017: 65).

The upshot of this is that there are three sets of distinctions in play here. Firstly, there is the distinction between institutional corruption and non-institutional corruption—the latter being the corruption of entities other than institutions, e.g., corruption of artefacts. Secondly, there is the distinction between personal and non-personal corruption—the former being the corruption of human beings as opposed to, for instance, institutional processes. Thirdly, with respect to personal corruption, there is the distinction between the corruption of persons qua institutional actors and non-institutional personal corruption. Non-institutional personal corruption is corruption of persons outside institutional settings. Personal corruption pertains to the moral character of persons, and consists in the despoiling of their moral character. If an action has a corrupting effect on a person’s character, it will typically be corrosive of one or more of a person’s virtues. These virtues might be virtues that attach to the person qua human being, e.g., the virtues of compassion and fairness in one’s dealings with other human beings. Corrosion of these virtues amounts to non-institutional personal corruption. Alternatively—or in some cases, additionally—these virtues might attach to persons qua occupants of specific institutional roles, e.g., impartiality in a judge or objectivity in a journalist. Corrosion of these virtues amounts to institutional personal corruption, i.e., corruption of a person qua institutional role occupant.

In order to provide an adequate account of institutional corruption we need a serviceable notion of an institution: the thing corrupted. For our purposes here it is assumed that an institution is an organization or structure of organizations that reproduces itself (e.g., by training and recruitment processes) and is comprised of a structure of institutional roles defined in terms of tasks (Harré 1979; Giddens 1984; Miller 2010). Accordingly, the class of institutions is quite diverse and includes political institutions, (e.g., legislatures), market-based institutions, (e.g., corporations), institutions of learning, (e.g., universities), security agencies, (e.g., police and military organizations), and so on. Importantly, as we noted above, the various different types of, and even motives for, institutional corruption vary greatly from one kind of institution to another.

Note that in theorizing institutional corruption the distinction between an entire society or polity, on the one hand, and its constituent institutions, on the other, needs to be kept in mind. A theory of democracy, for instance, might be a theory not only of democratic government in the narrow sense of the legislature and senior members of the executive, but also of the public administration as a whole, the judiciary, the security agencies (police and military), civil society and so on. Obviously, a theory of the corruption of democratic political institutions (in the narrow sense of the legislature and the senior members of the executive) might not be generalizable to other sorts of institution within a democracy, e.g., to security agencies or market-based institutions. Moreover, fundamental differences regarding the specific form that a democracy ought to take, e.g., between those of a republican persuasion (Pettit 1997; Sandel 2012) and libertarians (Nozick 1974; Friedman 1970), might morph into disputes about what counts as institutional corruption. For instance, on one view market-based institutions exist to serve the common good, while on another they exist only to serve the individual self-interest of the participants in them. Thus on the latter, but not the former, view market intervention by the government in the service of the common good might be regarded as a species of corruption. Further, a theory of the corruption of democracy, and certainly of the corruption of one species of democracy such as liberal democracy, is not necessarily adequate for the understanding of the corruption of many of institutions within a democracy and, in particular, those institutions, such as military and police institutions, hierarchical bureaucracies and market-based institutions, which are not inherently democratic either in structure or purpose, notwithstanding that they exist within the framework of a democratic political system, are shaped in various ways by that framework and, conversely, might be necessary for the maintenance of that framework.

2. Institutional Corruption

2.1 general features of institutional corruption.

Our concern here is only with institutional corruption. Nevertheless, it is plausible that corruption in general, including institutional corruption frequently, if not typically, involves the despoiling of the moral character of persons and in particular, in the case of institutional corruption, the despoiling of the moral character of institutional role occupants qua institutional role occupants. To this extent institutional corruption involves personal corruption and, thereby, connects institutional corruption to moral character. If the moral character of particular institutional role occupants, (e.g., police detectives), consists in large part of their possession of certain virtues definitive of the role in question (e.g., honesty, independence of mind, impartiality) then institutional corruption will frequently involve the displacement of those virtues in these role occupants by corresponding vices, (e.g., dishonesty, weak mindedness, bias); that is, institutional corruption will frequently involve institutional personal corruption.

As noted above, the relationship between institutional corruption and personal corruption is something that has been emphasized historically, e.g., by Plato, Aristotle and Machiavelli. However, some recent theorists of structural corruption have tended to downplay this relationship. Lessig’s notion of dependence corruption (Lessig 2011), in particular, evidently decouples structural corruption from (institutional) personal corruption (see section 2.3.3 below).

Personal corruption, i.e., the state of having been corrupt ed , is not the same thing as performing a corrupt action, i.e., being a corrupt or . Typically, corruptors are themselves corrupted, but this is not necessarily the case. Consider, for example, a parent who pays a one-off bribe to an immigration official in order to be reunited with her child. The parent is a corruptor by virtue of performing a corrupt action, but she is not necessarily corrupted by her, let us assume, morally justifiable action.

Does personal corruption imply moral responsibility for one’s corrupt character? This issue is important in its own right but it also has implications for our understanding of structural corruption. Certainly, many, if not most, of those who are corrupted are morally responsible for being so. After all, they do or should know what it is to be corrupt and they could have avoided becoming corrupt. Consider, for instance, kleptocrats, such as Mobuto and Marcos, who have looted billions of dollars from the public purse (Sharman 2017), or senior members of multi-national corporations who have been engaged in ongoing massive bribery in China and elsewhere (Pei 2016). These kleptocrats and corporate leaders are not only corruptors, they are themselves corrupt; moreover, they are morally responsible for being in their state of corruption.

However, there appear to be exceptions to the claim that personal corruption necessarily or always brings with it moral responsibility for one’s corrupt character, e.g., adolescents who have been raised in criminal families and, as a result, participate in the corrupt enterprises of these families. These individuals perform actions which are an expression of their corrupt characters and which also have a corrupting effect.

What of the moral responsibility of corruptors for their corrupt actions? It is plausible that many, if not most, corruptors are morally responsible for their corrupt actions (e.g., the legions of those rightly convicted of corruption in criminal courts—and therefore, presumably, morally responsible for their actions—in jurisdictions around the world), but there appear to be exceptions, e.g., those who are coerced into offering bribes.

One school of thought in the theory of social institutions that might well reject the view that corruptors are necessarily or even typically morally responsible (or, therefore, blameworthy) for their corrupt actions is structuralism (Lévi-Strauss 1962 [1966]) and especially structural Marxism (Althusser 1971). According to the latter view institutional structure and, in particular, economic class-based relations largely determine institutional structures and cultures, and regularities in the actions of institutional actors. On this anti-individualist conception neither institutional corrosion nor institutional corruption—supposing the two notions can be distinguished (see below)—are ultimately to be understood by recourse to the actions of morally responsible individual human agents. Strong forms of structuralism are inconsistent with most contemporary philosophical accounts of institutional corruption, not the least because these accounts typically assume that institutions have an inherently normative—rather than merely ideological—dimension. However there are echoes of weaker forms of structuralism in some of these accounts when it comes to the issue of the moral responsibility of human persons for institutional corruption. One influential contemporary theorist of corruption who apparently does not accept the view that corruptors are necessarily or always morally responsible (or, therefore, blameworthy) for their corrupt actions is Lessig (Lessig 2011) (see section 2.3.3 below).

The upshot of our discussion of (institutional) personal corruption and moral responsibility is as follows. We now have, at least notionally, a fourfold distinction in relation to corruptors: (1) corruptors who are morally responsible for their corrupt action and blameworthy; (2) corruptors who are morally responsible for their corrupt action but not blameworthy; (3) corruptors who are not morally responsible for having a corrupt character, but whose actions: (a) are expressive of their corrupt character, and; (b) have a corrupting effect; (4) corruptors who do not have a corrupt character and are neither morally responsible nor blameworthy for their corrupt actions, yet whose actions have a corrupting effect, e.g., by virtue of some form of structural dependency for which individual human persons are not morally responsible.

Naturally, in the case of institutional corruption typically greater institutional damage is being done than simply the despoiling of the moral character of the institutional role occupants. Specifically, institutional processes are being undermined, and/or institutional purposes subverted. A further point is that the undermining of institutional purposes or processes typically requires the actions of multiple agents; the single action of a single agent is typically not sufficient. The multiple actions of the multiple agents in question could be a joint action(s) or they could be individual actions taken in aggregate. A joint action is one in which two or more agents perform a contributory individual action in the service of a common or collective end (Miller 2010: Chapter 1) or, according to some theorists, joint intention (Bratman 2016: Chapter 1). For instance, motivated by financial gain, a group of traders within the banking sector might cooperate with one another in order to manipulate a financial benchmark rate, such as LIBOR (London Interbank Borrowing Rate) (Wheatley 2012).

However, arguably, the undermining of institutional processes and/or purposes is not a sufficient condition for institutional corruption. Acts of institutional damage that are not performed by a corruptor and also do not corrupt persons might be thought to be better characterized as acts of institutional corrosion . Consider, for example, funding decisions that gradually reduce public monies allocated to the court system in some large jurisdiction. As a consequence, magistrates might be progressively less well trained and there might be fewer and fewer of them to deal with the gradually increasing workload of cases. This may well lead to a diminution over decades in the quality of the adjudications of these magistrates, and so the judicial processes are to an extent undermined. However, given the size of the jurisdiction and the incremental nature of these changes, neither the magistrates, nor anyone else, might be aware of this process of judicial corrosion, or even able to become aware of it (given heavy workloads, absence of statistical information, etc.). At any rate, if we assume that neither the judges nor anyone else can do anything to address the problem then, while there has clearly been judicial corrosion, arguably there has not been judicial corruption. Why is such corrosion not also corruption?

For institutional corrosion to constitute corruption, it might be claimed (Miller 2017: Chapter 3), the institutional damage done needs to be avoidable; indeed, it might also be claimed that the relevant agents must be capable of being held morally responsible for the damage, at least in the generality of cases. So if the magistrates in our example were to become aware of the diminution in the quality of their adjudications, could cause additional resources to be provided and yet chose to do nothing, then arguably the process of corrosion might have become a process of corruption.

An important question that arises here is whether or not institutional corruption is relative to a teleological or purpose-driven conception of institutions and, relatedly, whether the purposes in question are to be understood normatively. Arguably, the institutional purposes of universities include the acquisition of new knowledge and its transmission to students; moreover, arguably, knowledge acquisition is a human good since it enables (indirectly), for instance, health needs to be met. However, it has been suggested that the purposes of political institutions, in particular, are too vague or contested to be definitive of them (Ceva & Ferretti 2017; Warren 2004). One response to this is to claim that governments are in large part meta-institutions with the responsibility to ensure that society’s other institutions realize their distinctive institutional purposes. On this view, an important purpose of governments is provided, in effect, by the purposes of other fundamental institutions. For instance, an important purpose of governments might be to ensure market-based institutions operate in a free, fair, efficient and effective manner (Miller 2017: 14.1).

Naturally, there are many different kinds of entities which might causally undermine institutions, including other collective entities. However, collectivist accounts of institutions go beyond the ascription of causal responsibility and, in some cases, ascribe moral responsibility. Firstly, such collectivist accounts of institutions ascribe intentions, beliefs and so on to organizations and other collective entities per se. Secondly, this ascription of mindedness to collective entities leaves the way open to ascribe moral agency to these entities (French 1979; List & Pettit 2011). On such collectivist accounts corruptors include collective entities; indeed, corruptors who are morally responsible for their corrupt actions. Thus Lockheed Corporation, on this view, was a moral agent (or, at least, an immoral agent) which corrupted the Japanese government (a second moral agent) by way of bribery. Other theorists, typically referred to as individualists, reject minded collective entities (Ludwig 2017; Miller 2010). Accordingly to individualists, only human agents are possessed of minds and moral agency. [ 4 ] Thus collective entities, such as organizations, do not have minds and are not per se moral agents. Accordingly, it is only human agents who culpably perform actions that undermine legitimate institutional processes or purposes.

An important related issue that arises at this point pertains to the human agents who perform acts of corruption. Are they necessarily institutional actors? It might be thought that this was not the case. Supposing a criminal bribes a public official in order to get a permit to own a gun. The criminal is not an institutional actor and yet he has performed an act of institutional corruption. However, in this example the public official has accepted the bribe and she is an institutional actor. So the example does not show that institutional corruption does not necessarily involve the participation of an institutional actor. What if the criminal offered the bribe but it was not accepted? While this may well be a crime and is certainly an attempt at institutional corruption, arguably, it is not an actual instance of an act of institutional corruption but rather a failed attempt. Moreover, it is presumably not an instance of institutional corruption because the institutional actor approached refused to participate in the attempted corrupt action. Let us pursue this issue further.

As we saw in section 1 , corruption, even if it involves the abuse of public office, is not necessarily pursued for private gain. However, according to many definitions of corruption institutional corruption necessarily involves abuse of public office. Moreover, our example of an attempted bribe to secure a gun permit involves a public official. However, we have canvassed arguments in section 1 that contra this view acts of corruption might be actions performed by persons who do not hold public office, e.g., price-fixing by market actors, a witness who gives false testimony in a law court. At this point in the argument we need to invoke a distinction between persons who hold a public office and persons who have an institutional role. CEOs of corporations do not hold public office but they do have an institutional role. Hence a CEO who embezzles his company’s money is engaged in corruption. Again, citizens are not necessarily holders of public offices, but they do have an institutional role qua citizens, e.g., as voters. Hence a voter who breaks into the electoral office and stuffs the ballot boxes with falsified voting papers in order to ensure the election of her favored candidate is engaged in corruption, notwithstanding the fact that she does not hold public office.

The causal theory of institutional corruption (Miller 2017) presupposes a normative teleological conception of institutions according to which institutions are defined not only as organizations or systems of organizations with a purpose(s), but organizations or systems of organizations the purpose(s) of which is a human good. The goods in question are either intrinsic or instrumental goods. For instance, universities are held to have as their purpose the discovery and transmission of knowledge, where knowledge is at the very least an instrumental good. (For criticisms see Thompson 2018 and Ceva & Ferretti 2021.)

If a serviceable definition of the concept of a corrupt action is to be found—and specifically, one that does not collapse into the more general notion of an immoral action—then attention needs to be focused on the moral effects that some actions have on persons and institutions. An action is corrupt only if it corrupts something or someone—so corruption is not only a moral concept, but also a causal or quasi-causal concept. That is, an action is corrupt by virtue of having a corrupting effect on a person’s moral character or on an institutional process or purpose. If an action has a corrupting effect on an institution, undermining institutional processes or purposes, then typically—but not necessarily—it has a corrupting effect also on persons qua role occupants in the affected institutions.

Accordingly, an action is corrupt only if it has the effect of undermining an institutional process or of subverting an institutional purpose or of despoiling the character of some role occupant qua role occupant. In light of the possibility that some acts of corruption have negligible effects, such as a small one-off bribe paid for a minor service, this defining feature needs to be qualified so as to include acts that are of a type or kind that tends to undermine institutional processes, purposes or persons ( qua institutional role occupants)—as well as individual or token acts that actually have the untoward effects in question. Thus qualified, the causal character of corruption provides the second main feature of the causal theory of institutional corruption, the first feature being the normative teleological conception of institutions. I note accounts predicated on these two assumptions have ancient origins, notably in Aristotle (Hindess 2001).

In keeping with the causal account, an infringement of a specific law or institutional rule does not in and of itself constitute an act of institutional corruption. In order to do so, any such infringement needs to have an institutionally undermining effect , or be of a kind that has a tendency to cause such an effect, e.g., to defeat the institutional purpose of the rule, to subvert the institutional process governed by the rule, or to contribute to the despoiling of the moral character of a role occupant qua role occupant. In short, we need to distinguish between the offence considered in itself and the institutional effect of committing that offence. Considered in itself the offence of, say, lying is an infringement of a law, rule, and/or a moral principle. However, the offence is only an act of institutional corruption if it has some institutionally undermining effect, or is of a kind that has such a tendency, e.g., it is performed in a courtroom setting and thereby subverts the judicial process.

A third feature of the causal theory of institutional corruption pertains to the agents who cause the corruption. As noted in section 2.1.3 , there are many different kinds of entities which might causally undermine institutions, including other collective entities. However, it is an assumption of the causal theory of corruption that only human agents are possessed of minds and moral agency. Accordingly, on the causal theory it is only human agents who culpably perform actions that undermine legitimate institutional processes or purposes.

A fourth and final feature of the causal theory also pertains to the agents who cause corruption. It is a further assumption of the causal theory that the human agents who perform acts of corruption (the corruptors) and/or the human agents who are corrupted (the corrupted) are necessarily institutional actors (see discussion above in section 2.1.3 ). More precisely, acts of institutional corruption necessarily involve a corruptor who performs the corrupt action qua occupant of an institutional role and/or someone who is corrupted qua occupant of an institutional role .

In light of the above discussion the following normative theory of corruption suggests itself: the causal theory of institutional corruption (Miller 2017: Chapter 3).

An act x (whether a single or joint action) performed by an agent (or set of agents) A is an act of institutional corruption if and only if:

- x has an effect, or is an instance of a kind of act that has a tendency to have an effect, of undermining, or contributing to the undermining of, some institutional process and/or purpose (understood as a collective good) of some institution, I , and/or an effect of contributing to the despoiling of the moral character of some role occupant of I , agent (or set of agents) B , qua role occupant of I ;

- A is a role occupant of I who used the opportunities afforded by their role to perform x , and in so doing A intended or foresaw the untoward effects in question, or should have foreseen them;

- B could have avoided the untoward effects, if B had chosen to do so. [ 5 ]

Note that (2) (a) tells us that A is a corruptor and is, therefore, either (straightforwardly) morally responsible for the corrupt action, or A is not morally responsible for A ’s corrupt character and the corrupt action is an expression of A ’s corrupt character.

Notice also that the causal theory being cast in general terms, i.e., the undermining of institutional purposes, processes and/or persons ( qua institutional role occupants), can accommodate a diversity of corruption in a wide range of institutions in different social, political and economic settings, past and present, and accommodate also a wide range of mechanisms or structures of corruption, including structural relations of dependency, collective action problems and so on.

A controversial feature of the causal account is that organizations that are entirely morally and legally illegitimate, such as criminal organizations, (e.g., the mafia), are not able to be corrupted (Lessig 2013b). For on the causal account the condition of corruption exists only relative to an uncorrupted condition, which is the condition of being a morally legitimate institution or sub-element thereof. Consider the uncorrupted judicial process. It consists of the presentation of objective evidence that has been gathered lawfully, of testimony in court being presented truthfully, of the rights of the accused being respected, and so on. This otherwise morally legitimate judicial process may be corrupted, if one or more of its constitutive actions are not performed in accordance with the process as it ought to be. Thus to present fabricated evidence, to lie under oath, and so on, are all corrupt actions. In relation to moral character, consider an honest accountant who begins to “doctor the books” under the twin pressures of a corrupt senior management and a desire to maintain a lifestyle that is only possible if he is funded by the very high salary he receives for doctoring the books. By engaging in such a practice he risks the erosion of his moral character; he is undermining his disposition to act honestly.

2.3 Theories of Political Corruption

Let us term theories of corruption which focus on the undermining of institutional procedures or processes, as opposed to institutional purposes, proceduralist theories of institutional corruption. Mark Warren has elaborated a proceduralist theory of the corruption of democracies, in particular; a theory which he terms “duplicitous exclusion” (Warren 2006). (Relatedly and more recently, Ceva & Ferretti speak of bending public rules in the service of “surreptitious agendas” as definitive of corruption (Ceva & Ferretti 2017: 6), although in a recent work they have shifted to a notion of corruption in terms of lack of accountability (Ceva & Ferretti 2018; Ceva & Ferretti 2021). See discussion below in 2.3.4.)

Democratic political institutions are characterized by equality (in some sense) with respect to these processes. Warren offers a particular account of democratic equality and derives his notion of corruption of democratic political institutions from this. According to Warren, democracies involve a norm of equal inclusion such that

every individual potentially affected by a collective decision should have an opportunity to affect the decision proportional to his or her stake in the outcome. (Warren 2004: 333)

Corruption of democracies occurs under two conditions: (1) this norm is violated and; (2) violators claim to be complying with the norm (Warren 2004: 337). Warren contrasts his theory of duplicitous exclusion with what he terms “office-based” accounts (Warren 2004:329–32).The latter might be serviceable for administrative agencies and roles but is, according to Warren, inadequate for democratic representatives attempting to “define the public interest” (Warren 2006: 10) and relying essentially on the political process, rather than pre-existing agreement on specific ends or purposes, to do so. This latter point is made in one way of another by other theorists of modern representative democracies, such as Thompson (2013) and Ceva & Ferretti (2017: 5), and is an objection to teleological accounts (such as the causal account— section 2.2 above).

Warren’s other necessary condition for the corruption of institutions, namely duplicity, resonates with the emphasis in the contemporary anti-corruption literature and, for that matter, in much public policy on transparency; transparency can reveal duplicity and thereby thwart corruptors. Moreover, the duplicity condition—and the related surreptitious agenda condition of Ceva & Ferretti—is reminiscent of Plato’s ring of Gyges (Plato Gorgias ); corruption is something done under a cloak of secrecy and typically involves deception to try to ensure the cloak is not removed. Unquestionably, corruption often flourishes under conditions of secrecy. Moreover, corruptors frequently seek to deceive by presenting themselves a committed to the standards that they are (secretly) violating. But contra Warren—and, for that matter, Ceva & Ferretti—corruption does not necessarily or always need to be hidden in order to flourish. Indeed, in polities and institutions suffering from the most serious and widespread forms of corruption at the hands of the very powerful, there is often little or no need for secrecy or deception in relation to the pursuit of corrupt practices; corruption is out in the open. Consider Colombia during the period of the drug lord, Pablo Escobar’s, “reign”; the period of the so-called “narcocracy”. His avowed and well-advertised policy was “silver or lead”, meaning that politicians, judges, journalists and so on either accepted a bribe or risked being killed (Bowden 2012). Against this it might be suggested that at least corruption in democracies always involves hiding one’s corrupt practices. Unfortunately, this seems not to be the case either. As Plato pointed out long ago in The Republic , democracies can suffer a serious problem of corruption among the citizenry and when this happens all manner of corrupt practices on the part of leaders and others will not only be visible, they will be tolerated, and even celebrated.

Warren’s theory is evidently not generalizable to many other institutions, namely, those that are not centrally governed by democratic norms and, in particular, by his norm of equal inclusion. Consider, for instance, military institutions. Most important decisions made by military personal in wartime—as opposed to those made by their political masters, such as whether to go to war in the first place—are made in the context of a hierarchical structure; they are not collective decisions, if the notion of a collective decision is to be understood on a democratic model of decision-making, e.g., representative democracy. Moreover, with respect to, for instance, the decision to retreat or stand and fight a combatant does not and cannot reasonably expect to have “an opportunity to affect the decision proportional to her stake in the outcome”. The combatant’s personal stake might be very high; his life is at risk if he stands and fights and, therefore, he might prefer to retreat. However, military necessity in a just war might dictate that he and his comrades stand and fight and, therefore, they are ordered to do so by their superiors back at headquarters and, as virtuous combatants, they obey. I note that Machiavelli contrasts combatants possessed of the martial virtues with corruptible mercenaries who only fight for money and who desert when their lives are threatened (Machiavelli The Prince : Chapter 12).

Thompson’s groundbreaking and influential theory of institutional corruption takes as its starting point a distinction between what Thompson refers to as individual corruption and institutional corruption. When an official accepts a bribe in return for providing a service to the briber, this is individual corruption since the official is accepting a personal benefit or gain in exchange for promoting private interests (Thompson 2013: 6). Moreover, the following two conditions evidently obtain: (i) the official intends to provide the service (or, at least, intends to give the impression that he will provide the service) to the bribee; (ii) the official and the bribee intentionally create the link between the bribe and the service, i.e., it is a quid quo pro . By contrast, institutional corruption involves political benefits or gains, e.g., campaign contributions (that do not go into the political candidates’ own pockets but are actually spent on the campaigns) by public officials under conditions that tend to promote private interests (Thompson 2013: 6). The reference to a tendency entails that there is some kind of causal regularity in the link between acceptance of the political benefits and promotion of the private interests (including greater access to politicians than is available to others (Thompson 2018)). However, the officials in question do not intend that there be such a link between the political benefits they accept and their promotion of the private interests of the provider of the political benefits. Rather

the fact that an official acts under conditions that tend to create improper influence is sufficient to establish corruption, whatever the official’s motive. (Thompson 2013: 13)

I note that in the case of institutional corruption and, presumably, individual corruption (in so far as it involves the bribery of public or private officials) the actions in question must undermine some institutional process or purpose (and/or perhaps institutional role occupant qua role occupant). Thus Thompson says of institutional corruption:

It is not corrupt if the practice promotes (or at least does not damage) political competition, citizenship representation, or other core processes of the institution. But it is corrupt if it is of a type that tends to undermine such processes and thereby frustrate the primary purposes of the institution. (Thompson 2013: 7)

While Thompson has provided an important analysis of an important species of institutional corruption, his additional claim that officials who accept personal benefits in exchange for promoting private interests, i.e., a common form of bribery, is not a species of institutional corruption is open to question (and a point of difference with the causal theory). As mentioned in section 1 , this species of bribery of institutional actors utilizing their position—whether that position be one in the public sector or in the private sector—can be systemic and, therefore, extremely damaging to institutions. Consider the endemic bribery of police in India with its attendant undermining of the provision of impartial (Kurer 2005; Rothstein & Varraich 2017), obligatory (Kolstad 2012) and effective police services, not to mention of public trust in the police. Some police stations in part of India are little more than unlawful “tax” collection or, better, extortion agencies; local business people have to pay the local police if they are to guarantee effective police protection, truck drivers have to pay bribes to the police at transport checkpoints, if they are to transit expeditiously through congested areas, speeding tickets are avoided by those who pay bribes, and so on. Moreover, endemic bribery of this kind is endemic in many police forces and other public sector agencies throughout so-called developing countries, even if it is no longer present in most developed countries.

Thompson invokes the distinction between systemic and episodic services provided by a public official in support of his distinction between individual and institutional corruption. By “systemic” Thompson means that the service provided by the official

is provided through a persistent pattern of relationships, rather than in episodic or one-time interactions. (The particular relationships do not themselves have to be ongoing: a recurrent set of one-time interactions by the same politician with different recipients could create a similar pattern.) (Thompson 2013: 11)

However, as our above example of bribery of police in India makes clear, Thompson’s individual corruption can be, and often is, systemic in precisely this sense. In more recent work Thompson has drawn attention to mixed cases involving, for instance, both a personal and a political gain—the political gain not necessarily being a motive—and suggested that if the dominant gain is political rather than personal then it is institutional corruption or perhaps a mix of individual and institutional corruption (Thompson 2018). Fair enough. However, this does not remove the objection that systemic bribery (for instance) involving only personal gain (both as a motive and an outcome) are, nevertheless, cases of institutional corruption.

Thompson uses the case of Charles Keating to outline his theory (Thompson 1995 and 2013). Keating was a property developer who made generous contributions to the election campaigns of various U.S. politicians, notably five senators, and then at a couple of meetings called on a number of these to do him a favor in return. Specifically, Keating wanted the senators to get a regulatory authority to refrain from seizing the assets of a subsidiary of a company owned by Keating. The chair of the regulatory authority was replaced. However, two years later the assets of the company in question were seized and authorities filed a civil racketeering and fraud suit against Keating accusing him of diverting funds from the company to his family and to political campaigns. Thompson argues that the Keating case involved: (1) the provision or, at least, the appearance of the provision of an improper service on the part of legislators (the senators) to a constituent (Keating), i.e., interfering with the role of a regulator on his behalf; (2) a political gain in the form of campaign contributions (from Keating to the senators), and; (3) a link or, at least, the appearance of a link between (1) and (2), i.e., the tendency under these conditions for the service to be performed because of the political gain.

Accordingly, the case study involves at least the appearance of corrupt activity on the part of the senators. Moreover, Thompson claims that such an appearance might be sufficient for institutional corruption in that damage has been done to a political institution by virtue of a diminution in public trust in that institution. Thus the appearance of a conflict of interest undermines public trust which in turn damages the institution. The appearance of a conflict of interest arises when legislators use their office to provide a questionable “service” to a person upon whom they are, or have been, heavily reliant for campaign contributions. Evidently, on Thompson’s account of institutional (as opposed to individual) corruption it is not necessary that the legislators in these kinds of circumstance ought to know that their actions might well have the appearance of a conflict of interest, ought to know that they might have a resulting damaging effect, and ought to know, therefore, that they ought not to have performed those actions. Certainly, the senators in the Keating case ought to have known that they ought not to perform these actions. However, the more general point is that it is not clear that it would be a case of corruption, if it were not the case that the legislators in question ought to have known that they ought not to perform the institutionally damaging actions in question. On the causal account ( section 2.2 above), if legislators or other officials perform institutionally damaging actions that they could not reasonably be expected to know would be institutionally damaging then they have not engaged in corruption but rather incidental institutional damage (and perhaps corrosion if the actions are ongoing).

As outlined above, Thompson has made a detailed application of his theory to political institutions and, especially to campaign financing in the U.S.. However, he views the theory as generalizable to institutions other than political ones. It is generalizable, he argues, in so far as “public purposes” can be replaced by “institutional purposes” and “democratic process” with “legitimate institutional procedures” (Thompson 2013: 5). Certainly, if the theory is to be generalizable then it is necessary that these replacements be made. The question is whether making these replacements is sufficient. Moreover, the particular species of institutional corruption that he has identified and analyzed might exist in other institutions but do so alongside a wide range of other species to which his analysis does not apply—including, but not restricted to, what he refers to as individual corruption. Thompson has recently identified some other forms of institutional corruption to which he claims his theory applies (Thompson 2018). For instance, the close relationship that might obtain between corporations and their auditing firms. The salient such relationships are those consisting of auditing firms undertaking profitable financial consultancy work for the very corporations which they are auditing; hence the potential for the independent auditing process to be compromised. These relationships certainly have the potential for corruption. However, they do not appear to be paradigms of institutional corruption in Thompson’s sense since, arguably, undertaking such consultancy work is not prima facie an integral function of auditing firms qua auditors in the manner in which, for instance, securing campaign finance is integral to political parties competing in an election (to mention Thompson’s paradigmatic example of institutional corruption).

Newhouse has attempted to generalize Thompson’ theory, but in doing so also narrows it. Newhouse argues that Thompson’s theory is best understood in terms of breach of organizational fiduciary duties (Newhouse 2014). An important underlying reason for this, says Newhouse, is that Thompson’s (and, for that matter, Lessig’s) account of institutional corruption presuppose that institutions have an “obligatory purpose” (Newhouse 2014: 555) Fiduciary duties are, of course, obligatory. Moreover, they are widespread in both the public and private sector; hence the theory would be generalized. On the other hand, there are many institutional actors who do not have fiduciary duties. Thus if Newhouse is correct in thinking that Thompson’s theory of institutional corruption provides a model for breach of organizational fiduciary duty and only for breach of organizational fiduciary duty, the ambition to generalize Thompson’s theory will remain substantially unrealized.

Lawrence Lessig has argued that the U.S. democratic political process and, indeed, Congress itself, is institutionally corrupt and that the corruption in question is a species of what he calls “dependency corruption” (Lessig 2011 and 2013a). Lessig argues that although U.S. citizens as a whole vote in the election of, say, the U.S. President, nevertheless, the outcome is not wholly dependent on these citizens as it should be in a democracy or, at least, as is required by the U.S. Constitution. For the outcome is importantly dependent on a small group of “Funders” who bankroll particular candidates and without whose funding no candidate could hope to win office. Accordingly, there are really two elections. In the first election only the Funders get to “vote” since only they have sufficient funds to support a political candidate. Once these candidate have been “elected” then there is a second election, a general election, in which all the citizens get to vote. However, they can only vote on the list of candidates “pre-selected” by the Funders. Lessig’s account of the U.S. election is complicated, but not vitiated, by the existence of a minority of candidates, such as Bernie Sanders, who rely on funding consisting of small amounts of money from a very large number of Funders. It is further complicated but not necessarily vitiated by the rise of demagogues such as Donald Trump who, as mentioned above, can utilise social media and computational propaganda to have an electoral influence much greater than otherwise might have been the case (Woolley and Howard 2019).