Digital Democracy: Social Media and Political Participation Essay

I. introduction.

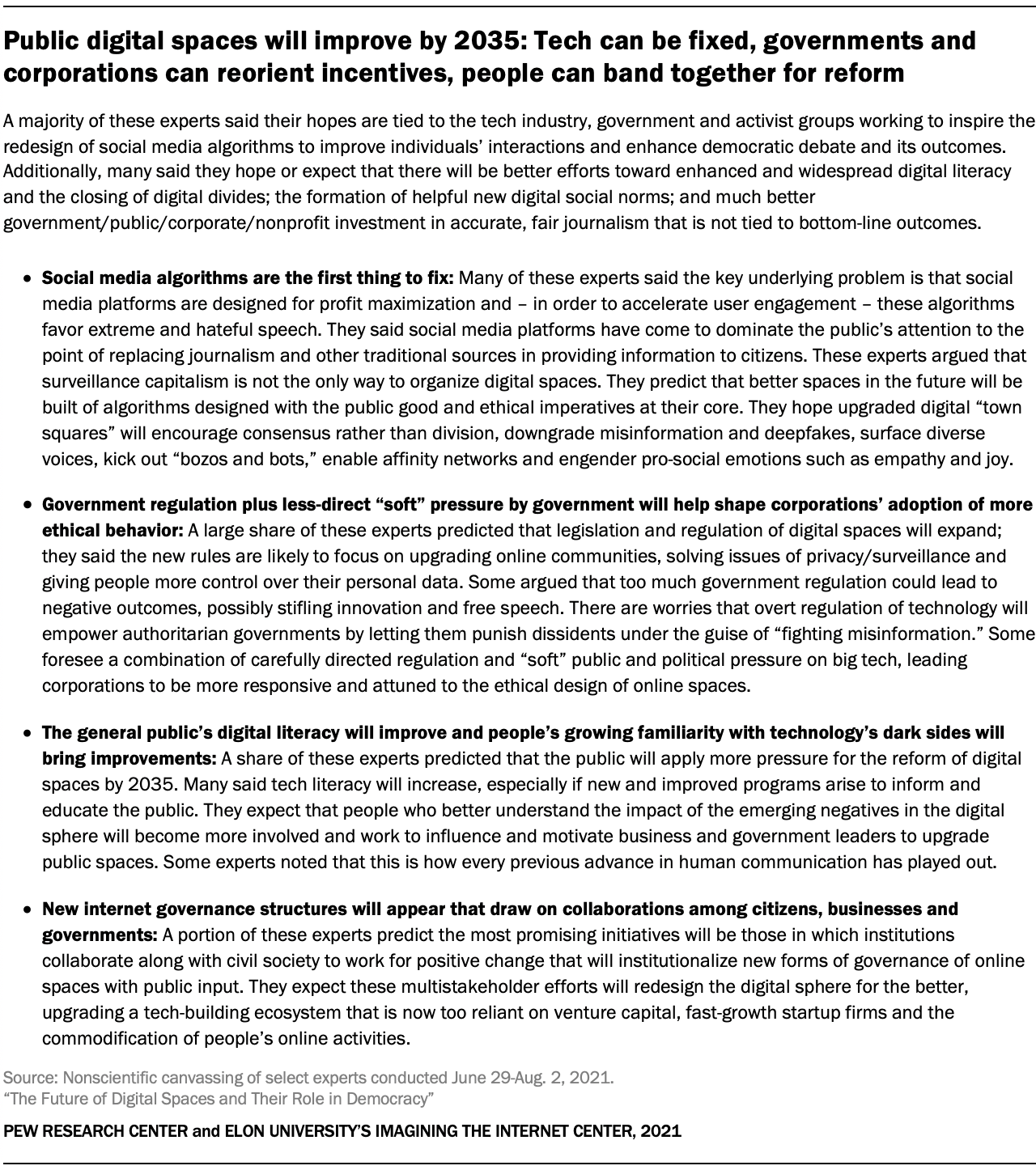

Digital democracy refers to the use of digital technologies and platforms to enhance democratic participation and representation. It contains various practices such as online voting , e-petitions , and political deliberation on social media. Social media has become an integral part of political participation in recent years. It has revolutionized the way citizens access information, engage in political discussion and mobilize for social and political causes. The purpose of this essay is to examine the impact of social media on political participation. It will highlight both the benefits and challenges of digital democracy. It will also explore the role of social media in shaping public opinion and the need for further research and regulation in this area.

II. The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation

A. increased access to information and political discussion:.

Social media has greatly increased access to information and political discussion for citizens. Platforms such as Twitter and Facebook provide a space for individuals to share news, express their views, and participate in political discussions. This allows citizens to stay informed about current events and access different perspectives on political issues.

For example , during the 2016 US Presidential elections , Twitter became a major platform for political discussion. Both candidates used it to communicate with their supporters and the general public.

Also Read: Political Instability Leads to Economic Downfall Essay

B. Increased Citizen Engagement and Mobilization:

Social media has also been used as a tool for mobilization during political campaigns and social movements. The Arab Spring , which began in 2010 , saw widespread protests organized and coordinated through social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

Similarly, the Black Lives Matter movement , which began in 2013 , saw widespread mobilization through social media. It saw individuals using platforms such as Instagram and Twitter to share information, organize protests, and raise awareness about racial inequality. This demonstrates the potential of social media to mobilize citizens and bring about political change.

C. Increased Political Polarization and Echo Chambers:

However, social media can also contribute to increased political polarization. The formation of “ echo chambers ” are also created by it. Echo chambers are where individuals are only exposed to information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs. This can lead to a lack of diversity in opinions and a lack of exposure to differing perspectives. Social media algorithms, which are designed to personalize content, can contribute to this phenomenon by only showing users information that aligns with their beliefs and interests.

For example , in India’s recent general elections in 2019 , social media platforms played a significant role in shaping public opinion and political participation. The ruling party, Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP ), effectively used social media platforms to mobilize support, spread their message, and influence public opinion. They used platforms like WhatsApp to spread false and misleading information. This helped them to secure a landslide victory.

D. Facilitation of Direct Democracy:

Social media platforms have also enabled direct democracy by allowing citizens to participate in online voting, e-petitions, and other forms of direct engagement with government and political representatives.

For example , some countries have implemented online voting systems for elections. This allowed citizens to cast their ballots from their computers or mobile devices. Estonia is one of those countries. Here, online voting has been implemented for all national and local elections since 2005 . E-petitions also have become a popular way for citizens to express their views and demand change on specific issues.

Similarly, in Canada , online voting has been introduced in some municipalities, including the City of Markham in Ontario. It used online voting in the 2018 municipal elections. Additionally, the government of Canada provides the MyVoice platform . Here, citizens can voice their opinions on issues, join online discussions and participate in online polls.

E. Influencing Public Opinion:

Social media also plays a significant role in shaping public opinion. Through social media, individuals and organizations can disseminate information. They also can express their views and shape public discourse. This has the potential to influence political decision-making and public policy. Additionally, social media platforms can be used to target specific audiences and demographics, which can impact public opinion and the outcome of elections.

Its examples were seen during the 2011 Arab Spring uprising, the 2016 US general elections, and the Black Lives Matter Movement.

F. Amplification of Marginalized Voices:

Social media platforms can also amplify the voices of marginalized communities and individuals, giving them a platform to share their perspectives and experiences. This can contribute to increased diversity in political discourse and representation. However, it also highlights the need for further research and regulation in this area to ensure that social media is inclusive, transparent, and fair for all voices.

The #MeToo movement is a specific example of how social media platforms can amplify the voices of marginalized communities and individuals. It gave them a platform to share their perspectives and experiences. The movement, which began in 2017 , aimed to raise awareness about sexual harassment and assault and to support survivors. The hashtag #MeToo was used extensively on social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook. Many women shared stories and experiences of sexual harassment and assault.

Also read: The Debate Over Renewable Energy: Is it the Solution to Climate Change?

III. The Challenges of Digital Democracy and Social Media

While social media and digital platforms have the potential to enable greater political participation and amplify marginalized voices, there are also several challenges that need to be addressed. Some of these challenges include:

- Misinformation and fake news : Social media platforms have been used to spread misinformation and fake news, which can undermine the democratic process and manipulate public opinion.

- Privacy and security : Social media platforms collect and store vast amounts of personal data, which can be vulnerable to breaches and misuse. This can compromise the privacy and security of individuals and threaten the integrity of the democratic process.

- Digital divide : Not all citizens have access to digital technologies and platforms, which can lead to a digital divide and exclude certain groups from participating in the democratic process.

- Lack of regulation : Social media platforms are currently not subject to the same regulations as traditional media, leading to a lack of accountability and oversight.

- Lack of diversity : Social media platforms can be dominated by certain groups or individuals, which can limit the diversity of voices and perspectives in political discourse.

- Cyberbullying and hate speech : Social media platforms have been used to spread hate speech and cyberbullying, which can undermine the democratic process and harm marginalized communities.

IV. Conclusion

In conclusion, social media and digital platforms have the potential to enable greater political participation and amplify marginalized voices. However, there are also several challenges that need to be addressed, including misinformation and fake news, privacy and security, digital divide, polarization and echo chambers, lack of regulation, lack of diversity, and cyberbullying and hate speech.

Addressing these challenges will require further research and regulation of social media and digital platforms, as well as efforts to increase access to digital technologies and platforms for all citizens. It’s also important to note that addressing these challenges will require the collaboration of government, the private sector, civil society, and citizens. Ultimately, a healthy digital democracy requires a balance between the benefits and challenges of social media and digital platforms, and the need to ensure that they are inclusive, transparent, and fair for all voices.

Similar Posts

Sharing is Caring!

Definition of “Sharing is Caring”: Sharing is a common phrase that refers to the act of distributing resources, time, or possessions among a group of people. It is often associated with the idea of being generous.

Islamophobia: Challenges and Ways to Combat for Ummah Essay

Islamophobia is defined as an irrational fear, hatred, or discrimination towards Islam and Muslims. This can manifest in various forms such as verbal or physical abuse, and hate crimes.

CSS Books Download in Pdf

The first book of all CSS books you can download for essay preparation is JWT Top 30 essay by Zahid Ashraf. The revised and updated edition is available here.

Great Nations Win Without Fighting Essay

Win without fighting” is a concept that refers to achieving victory or success without resorting to physical violence or military action. It emphasizes the use of alternative means such as diplomacy.

Globalization: A Weapon for Colonisation or a Tool for Development

Globalization has brought many benefits to the world, such as increased economic growth and cultural exchange. On the other hand, it has also been criticized.

The Controversial Issues of Feminism in Contemporary Women’s Rights Movements

The history of the feminist movement has been marked by significant progress toward gender equality. However, there are some challenges and issues of feminism.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

How does social media use influence political participation and civic engagement? A meta-analysis

2015 paper in Information, Communication & Society reviewing existing research on how social media use influences measures such as voting, protesting and civic engagement.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource October 18, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/politics-and-government/social-media-influence-politics-participation-engagement-meta-analysis/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Academic research has consistently found that people who consume more news media have a greater probability of being civically and politically engaged across a variety of measures. In an era when the public’s time and attention is increasingly directed toward platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, scholars are seeking to evaluate the still-emerging relationship between social media use and public engagement. The Obama presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012 and the Arab Spring in 2011 catalyzed interest in networked digital connectivity and political action, but the data remain far from conclusive.

The largest and perhaps best-known inquiry into this issue so far is a 2012 study published in the journal Nature , “A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Political Mobilization,” which suggested that messages on users’ Facebook feeds could significantly influence voting patterns. The study data — analyzed in collaboration with Facebook data scientists — suggested that certain messages promoted by friends “increased turnout directly by about 60,000 voters and indirectly through social contagion by another 280,000 voters, for a total of 340,000 additional votes.” Close friends with real-world ties were found to be much more influential than casual online acquaintances. (Following the study, concerns were raised about the potential manipulation of users and “digital gerrymandering.” )

There are now thousands of studies on the effects of social networking sites (SNS) on offline behavior, but isolating common themes is not easy. Researchers often use unique datasets, ask different questions and measure a range of outcomes. However, a 2015 metastudy in the journal Information, Communication & Society , “Social Media Use and Participation: A Meta-analysis of Current Research,” analyzes 36 studies on the relationship between SNS use and everything from civic engagement broadly speaking to tangible actions such as voting and protesting. Some focus on youth populations, others on SNS use in countries outside the United States. Within these 36 studies, there were 170 separate “coefficients” — different factors potentially correlated with SNS use. The author, Shelley Boulianne of Grant MacEwan University (Canada), notes that the studies are all based on self-reported surveys, with the number of respondents ranging from 250 to more than 1,500. Twenty studies were conducted between 2008 and 2011, while eight were from 2012-2013.

The study’s key findings include:

- Among all of the factors examined, 82% showed a positive relationship between SNS use and some form of civic or political engagement or participation. Still, only half of the relationships found were statistically significant. The strongest effects could be seen in studies that randomly sampled youth populations.

- The correlation between social-media use and election-campaign participation “seems weak based on the set of studies analyzed,” while the relationship with civic engagement is generally stronger.

- Further, “Measuring participation as protest activities is more likely to produce a positive effect, but the coefficients are not more likely to be statistically significant compared to other measures of participation.” Also, within the area of protest activities, many different kinds of activities — marches, demonstrations, petitions and boycotts — are combined in research, making conclusions less valid. When studies do isolate and separate out these activities, these studies generally show that “social media plays a positive role in citizens’ participation.”

- Overall, the data cast doubt on whether SNS use “causes” strong effects and is truly “transformative.” Because few studies employ an experimental design, where researchers could compare a treatment group with a control group, it is difficult to claim causality.

“Popular discourse has focused on the use of social media by the Obama campaigns,” Boulianne concludes. “While these campaigns may have revolutionized aspects of election campaigning online, such as gathering donations, the metadata provide little evidence that the social media aspects of the campaigns were successful in changing people’s levels of participation. In other words, the greater use of social media did not affect people’s likelihood of voting or participating in the campaign.”

It is worth noting that many studies in this area take social media use as the starting point or “independent variable,” and therefore cannot rule out that some “deeper” cause — political interest, for example — is the reason people might engage in SNS use in the first place. Further, some researchers see SNS use as a form of participation and engagement in and of itself, helping to shape public narratives and understanding of public affairs.

Related research: Journalist’s Resource has been curating a wide variety of studies in this field. See research reviews on: Effects of the Internet on politics ; global protest and social media ; digital activism and organizing ; and the Internet and the Arab Spring . For cutting-edge insights on how online organizing and mobilization is evolving, see the 2015 study “Populism and Downing Street E-petitions: Connective Action, Hybridity, and the Changing Nature of Organizing,” published in Political Communication .

Keywords: social media, Facebook, Twitter

About The Author

John Wihbey

- Infrastructure & Standards

- Information & Data

- Intellectual Property Rights

- Privacy & Security

Digital democracy

Introduction.

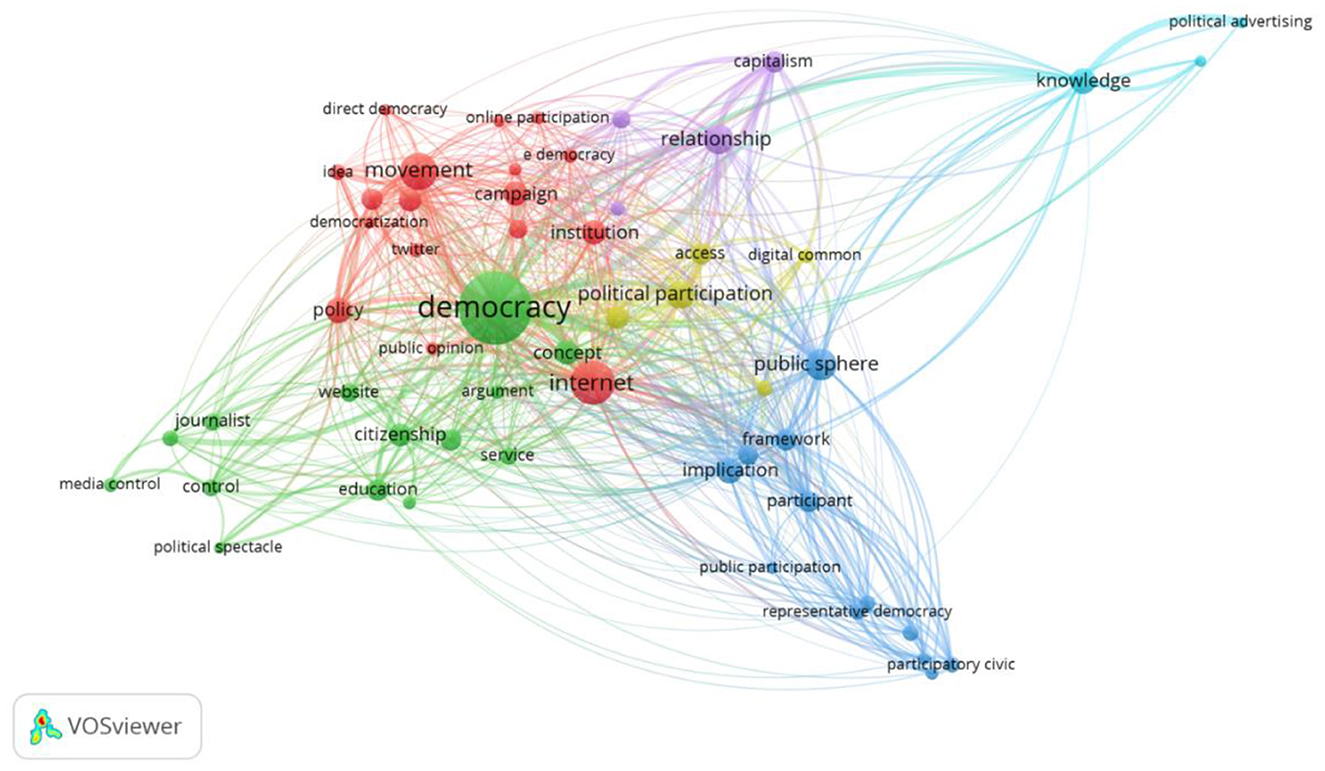

Digital democracy is a much discussed but rather fuzzy concept that still lacks a clear definition. We propose understanding digital democracy as a concept that links practices and institutions of collective political self-determination with its mediating digital infrastructures. Digital democracy has both an analytical and a normative dimension. As an analytical lens, digital democracy investigates how the use of digital technologies may influence the conditions, institutions and practices of political engagement and democratic governance. As a normative concept, it enables us to think about democracy as an open, alterable form of political organisation that is always in the making. Its dynamics are on the one hand due to conflicting principles, interpretations, and aspirations endemic to the democratic idea, like freedom, equality, or popular sovereignty. On the other hand, these dynamics also reflect a changing media landscape, which brings about new possibilities of imagining, realising, and practicing political self-determination. Therefore, digital democracy should neither be seen as a utopian model of an imminent future nor as a mere disintermediation of the existing democratic institutions. Instead of relying on monocausal, linear explanations, we suggest studying digital democracy as a contingent, open-ended phenomenon that interconnects two evolving areas, that of democratic self-government and that of digital infrastructures.

This text consists of three parts. The first section traces the harbingers and histories of digital democracy including their specific media constellation. It describes continuities and discontinuities in the interplay of technical change and hopes for democratisation. Interestingly, dreams of a direct democracy are among the recurring motifs. The second section critically reviews the premise of democratisation through technology. We find two schools of thought, one identifying digitalisation as a (disintermediating) driver of political change and another assessing the potential of digital technologies to bring democratic principles to bear in new and experimental settings. The final section covers four domains of digital democracy to illustrate the current transformation of democratic institutions and practices: democratic governance and the role of citizens, the public sphere as a condition of democratic action and political opinion formation, the organisation and repertoires of political action, and finally new forms of power and domination.

1. A brief historical outline

Digital democracy is a term filled with political aspirations. From an historical perspective, it is the latest model succeeding electronic democracy or teledemocracy, each of which emphasise the idea of democratisation through technology. Importantly, this idea has manifested itself not only in texts and discussions, but also in experimental projects. From the WELL (Rheingold, 1993) to the political participation platform “Rousseau”, these projects have sought to link specific visions of communication technology with the objective of improving democracy (Dahlberg, 2011) by reducing political alienation and increasing self-determination. Over the last 40 years, we can roughly distinguish three historical constellations in the evolution of digital democracy, each consisting of specific configurations of technologies and democratic imaginaries: i) electronic democracy, ii) virtual democracy, and iii) web 2.0 / network democracy. Depending on one’s point of view, these three periods are linked either by continuities or discontinuities in thought (for a different periodisation, see Vedel, 2006). A central common idea of these configurations refers to the use of communication technologies for implanting direct-democratic elements into representative democracy, which is often regarded as a “sorry substitute for the real thing” (Dahl, 1982).

Electronic democracy

One of the early forerunners of today’s social network sites (boyd & Ellison, 2007) and participation platforms is the back-channel-capable cable television of the 1980s, which inspires the idea of teledemocracy (Dutton, 1992; se Etzioni, 1992; Toffler, 1980). Using technology for improving democracy in the 1980s centres on strengthening information flows among citizens and facilitating participation. Cable TV channels would allow citizens to communicate among themselves without mediators (van Dijk, 2012, p. 50) and thereby create direct-democratic opportunities (Hindmann, 2009, p. 5; see Grossmann, 1996). An iconic image of this idea is the electronic town hall meeting. Evoking the dream of an Athenean agora, they are addressing political alienation by assembling like-minded people, making democracy more tangible and bridging the gap towards the political class (Dahlberg, 2011; Bimber, 2003; Barber, 1984; Held, 1987; Dahl, 1989).

The notion of information technology underlying the model of teledemocracy is predominantly limited to that of a tool, and therefore often shallow. An exception is Barber’s concept of a strong democracy, which argues that technology can be used in various, more or less democracy-enhancing ways. Hence, its “penchant for immediacy, directness, lateral communication” needs to be teased out (Barber, 1998, p. 585). Examples are Fishkin’s technique of deliberative polling (developed in 1988) or the use of Bulletin Board Systems for the networking of political activists (Myers, 1994; Rafaeli, 1984).

Virtual democracy

With the spread of the internet and its communication services in the early 1990s, new visions of virtual communities (Rheingold, 1993) emerged, which highlighted their unique features. The iconic image is no longer that of a local town hall but of “the global village”. Roughly thirty years after McLuhan coined the term, the global village seizes the Californian “small is beautiful” formula and links it to the utopian idea of a denationalised democracy, which will unfold in the virtual realm out of the government’s reach. Condemning existing political institutions as alienating, the internet pioneers intend to transfer their techno-libertarian imaginary of democracy into the emerging cyberspace (Schaal, 2016, p. 285). John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of Independence (1996) boldly portrays established democracies as tyrannies while cyberspace will facilitate new forms of political and economic self-determination, consisting of free and equal individuals (for the economic equivalent of liberation, see Dyson, 1997).

Merging neoliberal ideas of freedom from government (Johnson & Post, 1996) with a strong sense of individual liberation and privatisation counterculture (Turner, 2006), the distributed, seemingly power-diverting architecture of the internet comes to epitomise the 1990s style of political self-determination (for a different take, see Lessig, 1999; Goldsmith & Wu, 2006). Yet, in the shadow of neoliberalism, the rise of usenet groups, IRC channels and email lists also supports a communitarian version of democracy. It aims to revive the lost community as a new form of civic commons that John Gastil would later refer to as a “democracy machine” (Gastil, 2016). New types of “network cultures” (Lovink, 2009) are emerging, which may shed off “meat-spaced” ways of discrimination and marginalisation: “on the Internet nobody knows you are a dog”. However, with the demise of “internet exceptionalism” (Wu, 2011) in the early 2000s and the rising calls for regulating the digital infrastructure, democratic notions of a distinct cyberspace are losing traction.

Between web 2.0 and network democracy

T he participatory web of the new century’s first decade marks the transition from the “read-only” to the “read/write” web, with now constantly changing services supposed to “get(s) better the more people use it” (O’Reilly, 2005; see also Beer & Burrow, 2007). In light of the web 2.0, the netizens (Hauben & Hauben, 1997) of the 1990s are now turning into content producers who are able for the first time to individually contribute to the public discourse (Bruns & Schmidt, 2011; Shirky, 2008). Emerging communication services such as blogs, ‘daily me’ diaries, podcasts, virtual radios and video channels create novel possibilities of practising but also of imagining democracy (Dahlgren, 2000, p. 339).

While the web 2.0 democracy is broadly welcomed as a “tool for political change” (McPhillips, 2006), it lacks the utopian, revolutionary touch of virtual democracy. Instead, it focuses on realising a new stage of “mass participation in a representative democracy” (Froomkin, 2004, p. 3). Freedom is no longer the privilege of an elite of internet pioneers but becomes reconciled with notions of “cultural diversity, political discourse, and justice” (Benkler, 2006) within a “network democracy” (Hacker, 2002) or a “wikidemocracy” (Noveck, 2009). The price for mainstreaming the internet, however, is the amalgamation of commercial and emancipatory logics. New business models drive the global socialisation of novel communication services while simultaneously commodifying the private sphere and the human mind.

The perceived immediacy of digital technology and its possibilities of “organizing without organization” (Shirky, 2008) are expected to flatten established hierarchies and eliminate powerful bureaucracies. Indeed, there is a specific strength found in the “weak cooperation” among digitally connected people, which links individualism and solidarity in unpredictable, crowd-enabled ways (Aguiton & Cardon, 2007). The web 2.0 democracy also strongly resonates with Habermas’ concept of deliberative democracy, which emphasises the role of the public sphere for collective self-determination (Chadwick, 2008; see Habermas, 1996).

Unlike virtual democracy, which revisited the revolutionary roots of American independence, the periods of teledemocracy and web 2.0 democracy primarily pursued reformatory intentions. Premised on the optimistic belief that communication technology is democratic per se (Hindmann, 2009, p. 5), the overall goal is to release its potential for a more direct-democratic self-determination. A few years later, “platform populism” (Morozov, 2021) will take up the hope of an unmediated and direct ability to collectively act through digital technology (De Blasio & Sorice, 2018).

2. Mediated democracy in the digital constellation

Most contributions to the concept of digital democracy are concerning themselves with the ongoing transformation of democratic government. While some approaches centre on the de-institutionalising aspects of this change, others are interested in the experimental practices that may result in new or modified democratic institutions.

The first set of works tells stories of decay and destabilisation. This includes observations on the growing fragility of once powerful political parties, the dethroning of elections and electoral bodies as core democratic institutions and the profound structural change of the public sphere. The latter also concerns the eroding agenda-setting power of the mass media in favour of a more direct form of political communication (Dahlgren, 2005; Coleman, 2017). According to this perspective, digital communication services have become a threat to post-world war democracy and, therefore, raise the question if and how democracy needs to be defended against the fragmentation and hybridisation of the public sphere, the growing unpredictability of political will formation, but also the normalisation of hate speech, violence and disinformation campaigns (De Blasio & Viviani, 2020; Howard, 2020; Bennett & Livingston, 2020).

Approaches of de-institutionalisation or “disintermediation” (Urbinati, 2019) tend to put the blame on digital technologies. They take platforms and algorithmic systems as drivers of democratic change and thus ascribe a strong agency to digitalisation and its underlying business models. According to this popular view, social media distort democratic discourse through echo chambers and social bots (Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2017). Due to their global scope, social media concentrate “instrumentarian” (Zuboff, 2019) or “communication” power (Castells, 2009) in the hands of a few tech giants, effectively undermining a society’s capacity for self-determination (Rahman & Thelen, 2019). Terms such as “network democracy” imply that digital infrastructures also have formative effects on democratic institutions and thus tacitly accept them as blueprints of social change (Hacker, 2002).

By contrast, narratives on democratic transformation portray digital democracy as an experimental setting for the active reform of existing representative institutions. Digital resources for political action allow challenging democratic processes, some of which may translate into novel institutional settings. Traditionally, the law and the legislator form a central political medium: laws are the means by which citizens, through their parliamentary representatives, shape social order and social relationships. A growing number of civic tech organisations are emerging around legislative functions with the goal of reforming, enhancing or even replacing those legislative functions (Lukensmeyer, 2017). Platform parties aim to make organised political will formation more transparent and direct (Deseriis, 2020a; Gerbaudo, 2019). NGOs such as European Digital Rights (EDRi) strive for more effective ways of holding the political elite to account. Social movements also experiment with direct forms of democratic decision-making that includes the development of customised infrastructures for local bottom-up engagement, such as the digital platforms of “democracy-driven governance” in Barcelona and Madrid (Bua & Bussu, 2020; Lopez, 2018).

From the present vantage point of a democracy in flux, both narratives on digital change (the version on de-institutionalising and the one on re-institutionalising democratic institutions) shed light on practices, bodies and mechanisms once taken for granted, which used to constitute a now disintegrating political constellation (Berg et al., 2020a). Both perspectives thereby strengthen our awareness of the alterability of democracy, but particularly the latter points out new options for putting political self-determination into practice and thus politicising and shaping democracy itself.

Following the latter line of thought, digital technologies should neither be regarded as independent drivers nor a mere tool of political change. In philosophy of technology lingo, they constitute a “space of possibilities” (Hubig, 2006, pp. 155-160) structured by specific “affordances” (Evans et al., 2017), which may suggest but do not determine how democracies appropriate digital media (see Bossetta, 2018 for a contrasting approach). The notion of space of possibilities means that technologies enable countless, contingent ways of making use of them, with unpredictable effects on our future lives. “Digital democratic affordances” in the sense of Deseriis (2020b, p. 1), for example, refer to “the democratic capacities of digital media”, roughly defined as reducing the costs of political coordination. Crucially, such collective capacities can accommodate very different scenarios, ranging from instrumental action committed to a modernised representative democracy to ambitions of “democratising democracy” ( De Sousa Santos , 2005) aiming to challenge the given power distribution of governance structures.

Understood as media, the appropriation and use of technologies change our world views, our experiences, interpretations and expectations. However, how digital technologies are perceived and integrated into a democracy’s texture of political institutions, how we shape them and how they shape us, cannot be understood without taking into account the broader constellation of social, cultural and economic change (Hofmann, 2019). Digital democracy, then, is to be perceived as a re-intermediation rather than a disintermediation, ultimately resulting in new or changing institutions and infrastructural logics (Epstein, Katzenbach, Musiani, 2016; see Bolter & Grusin, 1999).

Understood as re-intermediation, digital democracy also encourages us to trace the evolution of democracy in a dynamic, open-ended fashion instead of creating linear narratives of rise and decline. The multiple, often conflicting trends in the relationship between political self-determination and its mediating infrastructures are becoming more visible from this perspective. Such a temporalising view on democracy entails sense-making narratives of the past: at least implicitly, we make sense of digital democracy by distinguishing it from former models of self-determination whose characteristics are taking on new meanings in the course of their decline.

3. Four domains of democratic transformation

Digitalisation provides new possibilities for realising democratic self-determination. This concerns constitutional dimensions that can be clustered in four domains of democratic transformation. These domains are i) the role of government and citizenship, ii) the public sphere, iii) the relationship between participation and representation, and iv) the issues of domination and rights. The following section takes a look at the concepts, terms and discourses that indicate how these possibilities are perceived and put into practice.

Democratic government and the role of citizens

In line with its predecessors, digital democracy implies various new notions of democratic governance. These notions include initiatives for Open Government (Noveck, 2015) or Open Democracy (Landemore, 2020) at one end of the spectrum and managerial data-based modes of governing the population at the other end.

Open government and open democracy projects aim to make policy processes more responsive and transparent. By empowering citizens to directly engage with public administrations, policies can be tailored more closely to their needs. The concept of open democracy extends to all levels, from local collaborations to nationwide digital Town halls or international agreements such as the Open Government Partnership (see Schnell, 2020). Some open government projects explicitly pursue strategies to sideline political parties and traditional hierarchies. The reimagining of government as a digital platform (O'Reilly, 2011, p. 13) or "wiki” (Noveck, 2009) intends to achieve horizontal forms of civic collaboration towards the undistorted realisation of the common good.

Despite all hopes for effective steps towards a digitally enabled direct democracy, concepts of mass participation have been facing organisational limits (Landemore, 2021, p. 78). For this reason, open government initiatives used to primarily focus on improving "accountability through transparency" (Hansson et al., 2015, p. 545) and exchange between citizens and government institutions (see Coleman, 2017). In the meantime, new decision-making systems and models for active mass participation have emerged, accommodating a broader understanding of citizenship. Notwithstanding the avant-gardist status, in most of these projects citizens are no longer perceived in their role of voters or (critical) spectators of democratic governance. Instead, citizens are meant to become actively involved in consultation as well as decision-making processes (Simon et al., 2017, p. 5; Deseriis 2020a, p. 2; De Blasio & Selva, 2016). Again, the city of Barcelona exemplifies the development of a well-thought-out participation strategy that has translated into a highly praised experiment of digitally empowered municipal self-government (Morozov & Bria, 2018; López, 2018, 2020).

In contrast to these participatory initiatives, digital technologies also facilitate more technocratically-oriented notions of responsive governance. The concept of "data democracy" (Susskind, 2018, p. 246), for example, imagines digital democracy as a science and management project geared towards perfecting the information base as a condition for effective policies. Epistemic practices such as "demos scraping", which seek to create data-based representations of the citizenry, reflect the idea that data analytics can "yield unprecedented insights into populations for policy makers" (Ulbricht, 2020, p. 429, see Khanna, 2017, p. 30). Approaches such as data democracy are criticised for epitomising the spirit of paternalistic liberalism (König, 2019). They tend to substitute data collection for political participation and achieve social well-being through “nudges” from above rather than through capacity-building for everyone.

Public sphere

As a space of opinion and will formation, the public sphere is an essential condition for liberal democracies. Communication media, the public sphere and democratic life are interconnected in many ways. This becomes obvious when we consider the profound political changes that new communication infrastructure have made possible since the introduction of broadcasting (Chadwick, 2013). With regard to digitalisation, this chiefly concerns the facilitating of public voices or user-generated content. While broadcasting and the printing press afforded privileged access to public speech to professionally trained journalists and the social elite, digital media has introduced many-to-many communication services, which, at least in principle, give a voice to everyone and create the foundation for “networked publics” (Varnelis, 2008). Social networks, the blogosphere and messenger services have formed a communication infrastructure, which both enables and shapes the present type of “mass self-communication” (Castells, 2009).

The transformation of the public sphere cannot only be attributed to digital media, however. As the growing appreciation of deliberative democracy (Habermas, 1996) shows, political opinion formation through public discourse has become increasingly important in itself but also relative to elections and parliamentary decision-making (Urbinati, 2006). Responding to a decline in trust in democratic institutions and public elites, the public sphere has also assumed the function of a watchdog, which holds the exercise of political power to account. In the digital constellation, the expanding role of the public sphere and the rise of digital media intersect, resulting in a changing representation of the public and a diversifying watchdog function. Tweets and hashtag assemblages have become accepted as expressions of public opinion and vox populi (McGregor 2019); the watchdog function is now exercised by a broader range of actors, among them civic tech activists, grassroot media and “influencers”.

Notions of monitory democracy (Keane, 2013) or “counter democracy” (Rosanvallon, 2008) represent one way of making sense of the digital constellation. “Networked publics” emphasises the horizontal links within a more active audience (Ito, 2008), with repercussions for our understanding of democratic agency and the democratic subject (Hofmann, 2019). In sum, there is a strong interdependence between shifting interpretations of the public sphere, changing democratic practices and the appropriation of digital technologies by citizens. This interdependence cannot be easily understood in terms of causal relationships.

As a side-effect of interacting through digital media such as platforms, the public is contributing to the production, circulation and ranking of information flows (Castells, 1996). With the public becoming generative, established social and legal boundaries between the production, circulation and consumption of news are blurring. Traditional mass media are losing control over their channels of communication to social networks (Kleis Nielson & Ganter, 2018). Journalistic standards of relevance are competing against algorithmic methods of content curation, including a probabilistic calculation of popularity and personalised interests (Ananny, 2020). The personalisation and horizontal distribution of information flows contributes to a significant pluralisation of the public sphere (Kleis Nielsen & Fletcher, 2020; Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018). As a result, shared political reference points, previously seen as a prerequisite for democratic discourse and will formation, may lose their self-evidence.

The ongoing “platformisation” (Poell et al., 2019; Helmond, 2015) of the public sphere offers insights into the now decaying stabilising mechanisms of representative democracies. The redistribution of public voice illuminates the rules and norms that used to delimit public discourse. This concerns familiar binaries between public and private, truth and lie, rational and irrational, politically influential and marginal positions. The agenda-setting power of traditional mass media shaped national world-views and helped delimit the invisible yet powerful “universe of the thinkable and unthinkable” (Bourdieu, 1996, p. 236). Democracy research has acknowledged the ambivalence of this development. Digital democracy may shift the locus of self-determination towards post-electoral, extra-parliamentary practices and institutionalise some form of “negative sovereignty” (Rosanvallon, 2008), which focus on the limitation of power rather than on its constructive use.

Political action beyond participation and representation

Digital democracy is taking shape at a time when once privileged forms of political action are in decline: political parties are suffering from membership loss, the emancipatory aura of the electoral franchise is fading, and the audience of the passive citizen has evolved to the active audience of “prosumers” (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010). A rebalancing has been taking place among the “two powers of the democratic sovereign” (Urbinati, 2014, p. 22), the public sphere as a space for discussion and the sphere of institutional decision-making, whereby the former has gained relevance compared to the latter. At the “democratic interface” (Bennett et al., 2018) between the institutionalised and non-institutionalised sphere of political action we observe a spirit of change, of exploring new types of engagement and influencing representative institutions. Not all of these experiments qualify as emancipatory, however. Some of them are testing constitutional boundaries, are manipulative or anti-democratic (Bennett & Livingston, 2018), evoking an “industry of democratic defences” (Müller, 2021) that are no less problematic (Farkas & Schou, 2019).

Digital campaign platforms enable mobilising for political issues, which, as in the case of Moveon.org or Avaaz, stand for the idea of voicing the people’s will more directly via crowdfunded lobbying (Karpf, 2012). Hashtag activism on social networks diversifies traditional forms of journalistic agenda-setting, transcends the passive notion of audience, and complements activist practices via the bottom-up creation of issue-publics, such as in the case of #BlackLivesMatter (Garza, 2020; see Berg et al., 2020b). The evolving civic tech activism creates digital infrastructures such as DECIDIM to “make engagement easier for citizens, improve communication and feedback between governments and citizens, and strengthen political accountability” (Baack, 2018, p. 45; Webb, 2020; Shrock, 2018). However, digital activism is not automatically more inclusive and receives more political recognition than analogue forms of engagement (Hindmann, 2009). On the contrary, the rise of the communicative paradigm that highlights public discourse and manifests in social movements runs the risk of neglecting the necessity of organisational ties to decision-making institutions such as parliaments and parties.

Political participation undergoes a shift from long-term engagement in political parties or associations towards issue-oriented, short-term and ephemeral forms of action, described by Bennett and Segerberg as a transition from collective to “connective action” (2012; see also Bimber, 2016). Yet, the fragile, volatile nature of most digital movements indicates that political organisations are not becoming obsolete. “Platform parties”, for example, aim to establish horizontal membership structures and engagement platforms designed to make internal communication and decision-making more direct and transparent (Deseriis & Vittori, 2019; McKelvey & Piebiak, 2018). Other political parties make their boundaries more permeable to recruit the temporary support of non-members (Scarrow, 2015, p. 128; Chadwick & Stromer-Galley, 2016).

Again, not all of these organisational experiments imply a democratisation of political structures. "Computational management" strategies (Kreiss, 2012, p. 144) aim to control political mobilisation along the manipulative incentive structures of the “voter surveillance” (Bennett & Lyon, 2019) and advertisement industry (Boler & Davis, 2021). In particular, this concerns the adoption of psychometric heuristics for the purpose of microtargeting specific groups of voters, which may fuel identity politics rather than create an enlightening public discourse (Kreiss, 2018; Papacharissi, 2015). The democratic idea of undermining the control of party elites through primaries and networked mobilisation not only allows for progressive politics. These structures also foster populist mobilisation, the rise of celebrities and political demagogues (De Blasio & Viviani, 2020).

The infrastructure of digital democracy allows for horizontal democratic self-organisation on a broader and interactive scale. Simultaneously, representative institutions are changing their repertoire of political coordination. Thus, digital democracy tackles the hierarchical bureaucratic organisation of representative democracy. New models are emerging along the tension of "interactivity and control" (Chadwick & Stromer-Galley, 2016, p. 3), partly absorbing the influences of a commodified and market-based approach to politics, through which political citizenship emerges to form public opinion and impact political decision-making.

Domination and rights

In the broadest sense, political power can be understood as a potential for individual and collective action to shape social order (Arendt, 1958; Rosanvallon, 2006). In its institutionalised form, power turns into rules, norms and domination. Digital democracy generates both new sources of power and changing constellations of rule and domination. Data and datafication exemplify new forms of power while their systematic collection and commodification as part of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019) constitute novel modes of domination. Both, new forms of power and changing constellations of domination are related since the latter structures the opportunities for democratising digital governance.

Today, digital platforms are described as the “organizational form of the early twenty-first century”, which monopolises the collection and analysis of data and establishes a specific form of “network dominance” (Stark & Pais, 2021; Magalhães & Couldry, 2021). As economic actors, they merge the datafication of everything with a commodification of everything, even democratic communication (Dean, 2009, see Zuboff, 2019). As versatile intermediaries, platforms have become private governors in their own right (Helberger, 2020; Gillespie, 2018), with profound effects on the infrastructure of democracy, including the conditions of “opinion power” (Helberger, 2020, p. 4), will formation, and self-government (Müller, 2021; Urbinati, 2019). Hence, platform power creates specific problems of domination for digital democracy and challenges constitutional ideas and arrangements of power-balancing (Suzor, 2018; Celeste, 2019).

The relationship between governments and digital platforms is complex and charged with paradoxical effects, subverting traditional notions of democratic sovereignty. As a customer of data, governments are mandating cooperation and obliging platforms to grant access to their data trove, for example in the area of law enforcement, police work and state security. For the field of intelligence services, Edward Snowden’s revelations have demonstrated the extent of public-private collaboration, including its problematic effects for human rights (Lyon, 2015; Jørgensen, 2019). As a regulator of data-based services, governments are enrolling platforms “as proxies of the state to enforce laws” (Fourcade & Gordon, 2020, p. 94), for example through “notice and take-down” provisions in the field of media law and communication (Keller & Leerssen, 2020). The boundaries between public and private sector seem to be blurring towards a symbiotic power constellation of aligned interests, which become legally and technically inscribed into the provision of digital infrastructures. The outsourcing of law enforcement to the private sector appoints platforms as “the primary governors of online communication (Helberger, 2020, p. 7; Klonick, 2017), with unclear consequences for the quality of public oversight and democratic accountability. And while fundamental rights could principally be strengthened in digital democracy, they are practically coming under pressure from both data-based business models and expanding surveillance competences of the state (de Gregorio, 2021; Redeker et al., 2018).

However, there are also initiatives towards a democratic re-embedding of these constellations of power and domination. With regard to human rights, the growing discrepancy between the potential and practical conditions of exercising human rights is increasingly yet unsystematically politicised across national borders. Internationally, the political struggle evolving around democratic principles for the digital constellation centres on a “language of users’ rights” (Suzor, 2018, p. 4) aiming to combat the current power constellation and the corresponding vulnerabilities of citizenship (Padovani & Santaniello, 2018). Such a language could sediment in a reinterpretation of fundamental rights as the normative framework for regulating platform power (Suzor et al., 2019). Since platforms govern the public sphere and thus determine the conditions for exercising the rights to freedom of speech and privacy, platforms should also be required to respect and protect human rights (Haggart & Keller, 2021; Kaye, 2019).

Mushrooming initiatives towards an “Internet Bill of Rights” are seen as evidence for a digital constitutionalism from below (Redecker et al., 2015). Digital constitutionalism gives birth to a new category of “constitutional subjects” (Teubner, 2004), among them not only international NGOs but, according to some, also the global platform corporations themselves. In this view, all actors affected contribute with informal norms to the juridification of the digital sphere (for recent examples, see Douek, 2019; Kloneck, 2020). However, such an approach has to navigate the fine line of including the private sector as constitutional subjects while at the same time preventing it from becoming the dominant one.

In addition to rights-based approaches, which pose the risk of individualising and depoliticising digital forms of domination, other forms of engagement can be found on the micro and the macro level. An example of the former refers to the growing political engagement of IT sector employees against management decisions in the form of “leaks” or walk-outs. On the macro level, national governments are addressing platform power under the claim of digital sovereignty. However, notions of sovereignty primarily justify a strengthening of the nation state instead of promoting democratisation (Pohle & Thiel, 2020). In contrast, civic tech approaches may be paving the way towards democratising digital constellations of power from below. As part of a “constitutional moment” (Celeste, 2019), digital democracy challenges the traditional state- and nation-centred focus and argues for a more pluralist approach to re-embed platform power and tame digital constellations of domination.

4. Conclusion

Digital democracy links political self-determination to technical innovation in contingent, unpredictable ways. Hence, its evolution reflects the open-ended, often experimental interplay of political imaginaries, concerns, and goals with new technical possibilities. However, investigating digital democracy entails lessons that go beyond the present techno-political constellation: political self-determination is a profoundly mediated project whose institutions and practices are constantly and contingently in flux. The changes we observe are often ambivalent and do not reflect a linear progression towards more direct, unmediated, or transparent forms of sovereignty. Likewise, digital democracy cannot be reduced to a strengthening, or weakening, of single elements such as freedom, equality, participation, or directness. Instead, political engagement and its objective are driven by different ways of interpreting and implementing democratic principles, which more often than not are in tension with each other. Given these endogenous dynamics, current changes of democracy defy a monocausal explanation and ask for interpretations that pay attention to the contingent interplay of political aspirations, digital possibilities and their social context.

Digital democracy evolves under mediated conditions that political actors can only partly control. While emerging democratic practices show traces of digital business models as well as commercial and political surveillance ambitions, they are simultaneously pushing back against these forms of alienation. New technologies are not only means, they also have become subject of political engagement. Hence, digital democracy involves struggles over its foundational principles, its directions and meaning, its infrastructure. It should therefore be understood as a contingent political arrangement in flux.

5. References

Aguiton, C., & Cardon, D. (2007). The Strength of Weak Cooperation: An Attempt to Understand the Meaning of Web 2.0. Communications & Strategies , 65 , 51–65.

Ananny, M. (2020). Presence of Absence: Exploring the democratic significance of silence [Preprint]. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/5ajyw

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition . The University of Chicago Press.

Baack, S. (2018). Civic tech at mySociety: How the imagined affordances of data shape data activism. Krisis , 1 , 44–56.

Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age . University of California Press.

Barber, B. R. (1998). Three Scenarios for the Future of Technology and Strong Democracy. Political Science Quarterly , 113 (4), 573–589. https://doi.org/10.2307/2658245

Barlow, J. P. (1996). A declaration of the independence of cyberspace . https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence

Beer, D., & Burrows, R. (2007). Sociology and, of and in Web 2.0: Some Initial Considerations. Sociological Research Online , 12 (5), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1560

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom (p. 515). Yale University Press.

Bennett, C. J., & Lyon, D. (2019). Data-driven elections: Implications and challenges for democratic societies. Internet Policy Review , 8 (4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1433

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication , 33 (2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (Eds.). (2020). The disinformation age: Politics, technology, and disruptive communication in the United States . Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking Political Communication in a Time of Disrupted Public Spheres. Journal of Communication , 68 (2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx017

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). THE LOGIC OF CONNECTIVE ACTION: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society , 15 (5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

Bennett, W. L., Segerberg, A., & Knüpfer, C. B. (2018). The democratic interface: Technology, political organization, and diverging patterns of electoral representation. Information, Communication & Society , 21 (11), 1655–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348533

Berg, S., König, T., & Koster, A.-K. (2020). Political Opinion Formation as Epistemic Practice: The Hashtag Assemblage of #metwo. Media and Communication , 8 (4), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i4.3164

Bimber, B. A. (2003). Information and American democracy: Technology in the evolution of political power . Cambridge University Press.

Boler, M., & Davis, E. (Eds.). (2021). Affective politics of digital media: Propaganda by other means . Routledge.

Bossetta, M. (2018). The Digital Architectures of Social Media: Comparing Political Campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 U.S. Election. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , 95 (2), 471–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018763307

Bourdieu, P. (1996a). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field . Stanford Univ. Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996b). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field (Nachdr). Stanford Univ. Press.

boyd, danah m., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 13 (1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Bruns, A., & Schmidt, J.-H. (2011). Produsage: A closer look at continuing developments. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia , 17 (1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2011.563626

Bua, A., & Bussu, S. (2021). Between governance‐driven democratisation and democracy‐driven governance: Explaining changes in participatory governance in the case of Barcelona. European Journal of Political Research , 60 (3), 716–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12421

Castells, M. (2009). Communication power . Oxford University Press.

Castells, M. (2010). The rise of the network society (2nd ed., with a new pref). Wiley-Blackwell.

Celeste, E. (2019). Digital constitutionalism: A new systematic theorisation. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology , 33 (1), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2019.1562604

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199759477.001.0001

Chadwick, A., & Stromer-Galley, J. (2016). Digital Media, Power, and Democracy in Parties and Election Campaigns: Party Decline or Party Renewal? The International Journal of Press/Politics , 21 (3), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216646731

Coleman, S. (2017). Can the internet strengthen democracy? Polity Press.

Coleman, S., & Shane, P. M. (Eds.). (2011). Web 2.0: New Challenges for the Study of E-Democracy in an Era of Informational Exuberance. In Connecting Democracy . The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9006.003.0005

Dahl, R. A. (1982). Dilemmas of pluralist democracy: Autonomy vs. control . Yale university press.

Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics (Nachdr.). Yale University Press.

Dahlberg, L. (2011). Re-constructing digital democracy: An outline of four ‘positions.’ New Media & Society , 13 (6), 855–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810389569

Dahlgren, P. (2000). The Internet and the Democratization of Civic Culture. Political Communication , 17 (4), 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600050178933

Dahlgren, P. (2005). The Internet, Public Spheres, and Political Communication: Dispersion and Deliberation. Political Communication , 22 (2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600590933160

De Blasio, E., & Selva, D. (2016). Why Choose Open Government? Motivations for the Adoption of Open Government Policies in Four European Countries: Motivations for the Adoption of Open Government Policies. Policy & Internet , 8 (3), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.118

De Blasio, E., & Sorice, M. (2018). Populism between direct democracy and the technological myth. Palgrave Communications , 4 (1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0067-y

De Blasio, E., & Viviani, L. (2020). Platform Party between Digital Activism and Hyper-Leadership: The Reshaping of the Public Sphere. Media and Communication , 8 (4), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i4.3230

De Gregorio, G. (2021). The rise of digital constitutionalism in the European Union. International Journal of Constitutional Law , 19 (1), 41–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moab001

de Sousa Santos, B. (Ed.). (2005). Democratizing democracy: Beyond the liberal democratic canon . Verso.

Dean, J. (2009). Democracy and other neoliberal fantasies: Communicative capitalism and left politics . Duke University Press.

Deseriis, M. (2020). Two Variants of the Digital Party: The Platform Party and the Networked Party (1.0) [Data set]. University of Salento. https://doi.org/10.1285/I20356609V13I1P896

Deseriis, M. (2021). Rethinking the digital democratic affordance and its impact on political representation: Toward a new framework. New Media & Society , 23 (8), 2452–2473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820929678

Deseriis, M., & Vittori, D. (2019). Platform Politics in Europe: Bridging Gaps between Digital Activism and Digital Democracy at the Close of the Long 2010s. International Journal of Communication , 13 (11). https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10803

Dijk, J. (2012). Digital Democracy: Vision and Reality. In I. Snellen, M. Thaens, & W. Donk (Eds.), Public Administration in the Information Age: Revisited (pp. 49–62). IOS Press.

Douek, E. (2019). Facebook’s “Oversight Board:” Move Fast with Stable Infrastructure and Humility. North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology , 21 (1), 1–78.

Dutton, W. H. (1992). Political Science Research on Teledemocracy. Social Science Computer Review , 10 (4), 505–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443939201000405

Dyson, E. (1997). Release 2.0 - die Internet-Gesellschaft: Spielregeln für unsere digitale Zukunft . Droemer Knaur.

Epstein, D., Katzenbach, C., & Musiani, F. (2016). Doing internet governance: Practices, controversies, infrastructures, and institutions. Internet Policy Review , 5 (3). https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.3.435

Etzioni, A. (1992). Teledemocracy: The Electronic Town Meeting. The Atlantic , 270 (4), 36–39.

Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., & Treem, J. W. (2017). Explicating Affordances: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Affordances in Communication Research: EXPLICATING AFFORDANCES. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 22 (1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12180

Farkas, J., & Schou, J. (2019). Post-truth, fake news and democracy: Mapping the politics of falsehood . Routledge.

Forschungsgruppe Demokratie und Digitalisierung, Weizenbaum-Institut für die vernetzte Gesellschaft, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berg, S., Rakowski, N., & Thiel, T. (2020). Die digitale Konstellation. Eine Positionsbestimmung. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft , 30 (2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-020-00207-6

Fourcade, M., & Gordon, J. (2020). Learning Like a State: Statecraft in the Digital Age. Journal of Law and Political Economy , 78 , 78–108. https://doi.org/10.5070/LP61150258

Froomkin, M. (2004). Technologies for Democracy. In P. Shane (Ed.), Democracy Online: The Prospects for Political Renewal Through the Internet (pp. 3–20). https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=182916

Garza, A. (2020). The purpose of power: How to build movements for the 21st century . Doubleday.

Gastil, J. (2016). Building a Democracy Machine: Toward an Integrated and Empowered Form of Civic Engagement . Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/democracy_machine.pdf

Gerbaudo, P. (2019). The Platform Party: The Transformation of Political Organisation in the Era of Big Data. In D. Chandler & C. Fuchs (Eds.), Digital Objects, Digital Subjects: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Capitalism, Labour and Politics in the Age of Big Data (pp. 187–198). University of Westminster Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvckq9qb.18

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media . Yale University Press.

Goldsmith, J., & Wu, T. (2006). Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195152661.001.0001

Grossman, L. K. (1996). The electronic republic: Reshaping democracy in the information age . Penguin Books.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy . MIT Press.

Hacker, K. L. (2002). Network Democracy and the Fourth World. Communications , 27 (2). https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.27.2.235

Haggart, B., & Keller, C. I. (2021). Democratic legitimacy in global platform governance. Telecommunications Policy , 45 (6), 102152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102152

Hansson, K., Belkacem, K., & Ekenberg, L. (2015). Open Government and Democracy: A Research Review. Social Science Computer Review , 33 (5), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314560847

Hauben, M., & Hauben, R. (1997). Netizens: On the history and impact of Usenet and the Internet . IEEE Computer Society Press.

Helberger, N. (2020). The Political Power of Platforms: How Current Attempts to Regulate Misinformation Amplify Opinion Power. Digital Journalism , 8 (6), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888

Held, D. (1987). Models of democracy . Stanford University Press.

Helmond, A. (2015). The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society , 1 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080

Hindman, M. S. (2009). The myth of digital democracy . Princeton University Press.

Hofmann, J. (2019). Mediated democracy – Linking digital technology to political agency. Internet Policy Review , 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.2.1416

Howard, P. N. (2020). Lie machines: How to save Democracy from troll armies, deceitful robots, junk news operations, and political operatives . Yale University Press.

Hubig, C. (2006). Die Kunst des Möglichen: Grundlinien einer dialektischen Philosophie der Technik . Transcript.

Ito, M. (2008). Introduction. In K. Varnelis (Ed.), Networked Publics (pp. 1–13). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262220859.003.0001

Johnson, D. R., & Post, D. G. (1997). Law And Borders—The Rise of Law in Cyberspace. SSRN Electronic Journal . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.535

Jørgensen, R. F. (Ed.). (2019). Human Rights in the Age of Platforms . The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11304.001.0001

Julián López, J. (2018). Human Rights as Political Imaginary . Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74274-8

Karpf, D. (2012). The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199898367.001.0001

Kaye, D. (2019). Speech Police: The global struggle to govern the internet . Columbia Global Reports.

Keane, J. (2013). Democracy and Media Decadence . Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107300767

Khanna, P. (2017). Technocracy in America rise of the info-state . CreateSpace.

Kleis Nielsen, R., & Fletcher, R. (2020). Democratic Creative Destruction? The Effect of a Changing Media Landscape on Democracy. In N. Persily & J. A. Tucker (Eds.), Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108890960

Klonick, K. (2018). The New governors: The People, rules, and processes governing online speech. Harvard Law Review , 131 , 1598–1670.

Klonick, K. (2020). The Facebook Oversight Board: Creating an Independent Institution to Adjudicate Online Free Expression. Yale Law Journal , 129 (2418), 2418–2499.

König, P. D. (2019). Die digitale Versuchung: Wie digitale Technologien die politischen Fundamente freiheitlicher Gesellschaften herausfordern. Politische Vierteljahresschrift , 60 (3), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-019-00171-z

Kreiss, D. (2012). Taking Our Country Back: The Crafting of Networked Politics from Howard Dean to Barack Obama . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199782536.001.0001

Kreiss, D. (2018). The Media are About Identity, not Information. In P. J. Boczkowski & Z. Papacharissi (Eds.), Trump and the media (pp. 93–101). The MIT Press.

Landemore, H. (2020). Open Democracy . Princeton University Press.

Landemore, H. (2021). Open Democracy and Digital Technologies. In L. Bernholz, H. Landemore, & R. Reich (Eds.), Digital Technology and Democratic Theory (pp. 62–89). The University of Chicago Press. https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Chapte-2_9780226748436_1stPages_Mktg-2-1.pdf

Lessig, L. (1999). Code and other laws of cyberspace . Basic Books.

Lovink, G. (2011). Dynamics of critical internet culture (1994-2001) .

Lukensmeyer, C. J. (2017). Civic Tech and Public Policy Decision Making. PS: Political Science & Politics , 50 (03), 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000567

Lyon, D. (2015). Surveillance after Snowden . Polity Press.

Magalhães, V., & Nick, C. (2021). Giving by Taking Away: Big Tech, Data Colonialism, and the Reconfiguration of Social Good. International Journal of Communication , 15 , 343–362.

Manin, B. (1997). The Principles of Representative Government (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511659935

Mayer-Schönberger, V., & Cukier, K. (2014). Big data: A revolution that will transform how we live, work, and think (First Mariner Books edition). Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

McKelvey, F., & Piebiak, J. (2018). Porting the political campaign: The NationBuilder platform and the global flows of political technology. New Media & Society , 20 (3), 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675439

McPhilips, F. (2006). Internet Activism. Towards a Framework for Emergent Democracy. In P. Isaías, M. B. Nunes, & I. J. Martínez (Eds.), Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference WWW/Internet 2006 (Vols. 5–8, pp. 329–338).

Morozov, E. (2021, February 3). Why the GameStop affair is a perfect example of „platform populism“. The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/feb/03/gamestop-platform-populism-uber-airbnb-wework-robinhood-democracy

Morozov, E., & Bria, F. (2018). Rethinking the Smart City: Democratizing Urban Technology . Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. https://sachsen.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/sonst_publikationen/rethinking_the_smart_city.pdf

Muller, J.-W. (2021). Democracy rules . Farrar, Straus and Giroux. https://rbdigital.rbdigital.com

Myers, D. J. (1994). Communication Technology and Social Movements: Contributions of Computer Networks to Activism. Social Science Computer Review , 12 (2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443939401200209

Noveck, B. S. (2009). Wiki government: How technology can make government better, democracy stronger, and citizens more powerful . Brookings Institution Press.

Noveck, B. S. (2015). Smart citizens, smarter state: The technologies of expertise and the future of governing . Harvard University Press.

O’Reilly, T. (2005). Web 2.0: Compact Definition? Radar . http://radar.oreilly.com/2005/10/web-20-compact-definition.html

O’Reilly, T. (2011). Government as a Platform. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization , 6 (1), 13–40. https://doi.org/10.1162/INOV_a_00056

Padovani, C., & Santaniello, M. (2018). Digital constitutionalism: Fundamental rights and power limitation in the Internet eco-system. International Communication Gazette , 80 (4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518757114

Papacharissi, Z. (2014). Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199999736.001.0001

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you . Viking. https://archive.org/details/filterbubblewhat0000pari_z3l4

Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review , 8 (4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425

Pohle, J., & Thiel, T. (2020). Digital sovereignty. Internet Policy Review , 9 (4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1532

Rafaeli, S. (1984). The Electronic Bulletin Board: A Computer-Driven Mass Medium. Social Science Micro Review , 2 (3), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443938600200302

Rahman, K. S., & Thelen, K. (2019). The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism. Politics & Society , 47 (2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329219838932

Redeker, D., Gill, L., & Gasser, U. (2018a). Towards digital constitutionalism? Mapping attempts to craft an Internet Bill of Rights. International Communication Gazette , 80 (4), 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518757121

Redeker, D., Gill, L., & Gasser, U. (2018b). Towards digital constitutionalism? Mapping attempts to craft an Internet Bill of Rights. International Communication Gazette , 80 (4), 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518757121

Rheingold, H. (2000). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier (Rev. ed). MIT Press.

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, Consumption, Prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer.’ Journal of Consumer Culture , 10 (1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-democracy: Politics in an age of distrust . Cambridge University Press.

Rosanvallon, P., & Moyn, S. (2006). Democracy past and future . Columbia university press.

Scarrow, S. (2014). Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199661862.001.0001

Schaal, G. S. (2016). E-Democracy. In O. W. Lembcke, C. Ritzi, & G. S. Schaal (Eds.), Zeitgenössische Demokratietheorie (pp. 279–305). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06363-4_12

Schnell, S. (2020). Vision, Voice, and Technology: Is There a Global “Open Government” Trend? Administration & Society , 52 (10), 1593–1620. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720918316

Schrock, A. (2018). Civic tech: Making technology work for people .

Shirky, C. (2009). Here comes everybody: The power of organizing without organizations . Penguin Books.

Simon, J., Bass, T., Boelman, V., & Mulgan, G. (2017). Digital Democracy. The tools transforming political engagement. Nesta [Report]. Nesta. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/digital_democracy.pdf

Stark, D., & Pais, I. (2021). Algorithmic Management in the Platform Economy. Sociologica , 47-72 Pages. https://doi.org/10.6092/ISSN.1971-8853/12221

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media . Princeton University Press.

Susskind, J. (2018). Future politics: Living together in a world transformed by tech (First edition). Oxford University Press.

Suzor, N. (2018). Digital Constitutionalism: Using the Rule of Law to Evaluate the Legitimacy of Governance by Platforms. Social Media + Society , 4 (3), 205630511878781. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118787812

Suzor, N., Dragiewicz, M., Harris, B., Gillett, R., Burgess, J., & Van Geelen, T. (2019). Human Rights by Design: The Responsibilities of Social Media Platforms to Address Gender-Based Violence Online: Gender-Based Violence Online. Policy & Internet , 11 (1), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.185

Teubner, G. (2004). Societal Constitutionalism: Alternatives to State-centred Constitutional Theory . Storrs Lectures. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=876941

Toffler, A. (1990). The third wave: The classic study of tomorrow . Bantam Books.

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism . University of Chicago Press.

Ulbricht, L. (2020). Scraping the Demos. Digitalization, Web Scraping and the Democratic Project. Democratization , 27 (3), 426–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1714595

Urbinati, N. (2006). Representative democracy: Principles and genealogy . University of Chicago Press.

Urbinati, N. (2014). Democracy disfigured: Opinion, truth, and the people . Harvard University Press.

Urbinati, N. (2019). Me the people: How populism transforms democracy . Harvard University Press.

Varnelis, K. (Ed.). (2008). Networked publics . MIT Press.

Vedel, T. (2006). The Idea of Electronic Democracy: Origins, Visions and Questions. Parliamentary Affairs , 59 (2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsl005

Webb, M. (2020). Coding democracy: How hackers are disrupting power, surveillance, and authoritarianism . MIT Press.

Wu, T. (2011). Is Internet Exceptionalism Dead? In B. Szoka, A. Marcus, J. L. Zittrain, Y. Benkler, & J. G. Palfrey (Eds.), The next digital decade: Essays on the future of the internet (pp. 179–188). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1752415

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power . Profile books.

Add new comment

Adjusts contrasts, text, and spacing in order to improve legibility for people with dyslexia.

Contrasts, text, and spacing are adjusted in order to improve legibility for people with dyslexia. Also, links look like this and italics like this . Font is changed to Atkinson Hyperlegible

Is this feature helpful for you, or could the design be improved? If you have feedback please send us a message .