How to Stop Procrastinating: A Guide for PhD Students and Academics

To keep up to date, or follow our social media, the author of this post:.

Jayron Habibe

A finishing PhD students in Medical Biochemistry. He has a love for writing about practical tools that make life as a PhD student just a little bit easier. Learn more about Jayron

Posts recommended by Jayron:

The Best Project Management Methods for Researchers and Academics

What Is Project Management And Why Do You Need It Project management methods are the

The Art of Efficient Note Taking: Strategies to Excel in Your Academic Journey

Why is Note Taking Important for Academics? Note taking is a skill that lies at

6 powerful lessons from running a marathon during your PhD

What is a Marathon? Doing a PhD is often compared to running a marathon. But

Join our Team!

Support us.

🧠Introduction

As a PhD student or academic, you are well aware of the unique challenges that come with managing research projects and meeting deadlines. However, one common hurdle that can hinder your progress is the tendency to start procrastinating.

You may find yourself putting off important tasks, succumbing to distractions, and struggling to make the most of your time. But fear not! This comprehensive guide is specifically designed to help PhD students and academics like you overcome procrastination and maximize productivity.

In the world of academia, productivity is not just a buzzword; it is essential for achieving research goals, making significant contributions to your field, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance . By adopting effective strategies and implementing practical techniques, you can break free from the cycle of procrastination and optimize your productivity, ultimately leading to greater success and personal fulfillment.

Throughout this guide, we will explore a range of proven strategies tailored to the unique needs of PhD students and academics. You will discover how to create a daily to-do list that encompasses research tasks, deadlines, and academic responsibilities. We’ll delve into the power of time blocking and how it can help you allocate dedicated time for research, writing, teaching, and personal development. You’ll also learn how to find your optimal working style, incorporating techniques such as deep work sessions, or collaborative sessions that resonate with your workflow.

Rewarding yourself for research and academic milestones is vital for maintaining motivation, so we’ll explore how to celebrate your achievements along the way. We’ll discuss the importance of minimizing context switching, avoiding distractions, and maintaining focus during crucial work sessions.

By implementing the strategies outlined in this guide, you will not only overcome procrastination but also unlock your full potential as a PhD student or academic. The path to success is paved with intentional, focused, and productive work. Are you ready to stop procrastinating and embark on a journey of enhanced productivity? Let’s dive in and transform your research and academic experience.

🗒️Daily To-Do List for Researchers and Academics

A well-structured and thoughtfully crafted daily to-do list is a powerful tool for PhD students and academics. It provides a roadmap for your day, helping you stay organized, focused, and on track with your research and academic commitments.

It is important to create a to-do list that reflects your priorities and aligns with your long-term goals. Start by capturing all the tasks and responsibilities you need to address, including research activities, writing assignments, teaching duties, meetings, and administrative tasks. Be thorough in this process to ensure nothing falls through the cracks.

Another valuable tip is to break down larger tasks into smaller, actionable steps . This approach helps prevent overwhelm and allows you to make progress incrementally. For instance, if you have a research paper to write, break it down into phases like conducting literature reviews, collecting data, outlining, drafting, and revising. By tackling one step at a time, you’ll feel a sense of accomplishment and stay motivated throughout the process.

Furthermore, assigning realistic time estimates to each task helps you allocate your time effectively and avoid over-committing. This practice ensures that you have a clear understanding of the time required for each task, preventing unnecessary stress and frustration.

Once you have your list of tasks, it’s crucial to prioritize them effectively. Here, you can use the concept of “ABC prioritization,” which involves categorizing tasks into three levels of importance: A, B, and C. A-tasks are high-priority and have a significant impact, B-tasks are important but less urgent, and C-tasks are those that can be deferred or delegated if possible.

To take your prioritization a step further, you can use the Eisenhower Matrix, a productivity framework that classifies tasks into four quadrants: important and urgent, important but not urgent, urgent but not important, and not important or urgent. This matrix helps you identify critical tasks that require immediate attention and separate them from tasks that can be scheduled or eliminated.

Lastly, review and update your to-do list regularly . Priorities may shift, deadlines may change, and new tasks may arise. By taking a few minutes at the beginning or end of each day to review and adjust your to-do list, you ensure that it remains relevant, up-to-date, and aligned with your overall goals.

If you’d like to use an app that makes creating to-do lists super easy I would recommend checking out Todoist . It has tons of awesome features while being extremely easy and simple to just get started with. It also happens to be my to-do list app of choice so if you’re interested just check it out.

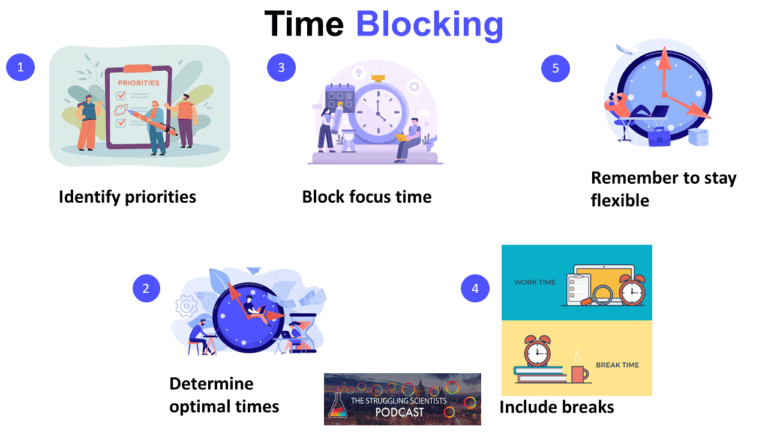

⏳Time Blocking for Researchers and Academics

Time blocking is a powerful technique that allows PhD students and academics to optimize their productivity by allocating dedicated blocks of time for specific tasks or activities. By implementing this strategy, you can effectively manage your workload, reduce distractions, and make significant progress in your research and academic endeavors.

Time blocking involves dividing your day into distinct time slots, each dedicated to a specific task or type of activity. This structured approach helps create a sense of focus and clarity, enabling you to prioritize and complete tasks more efficiently. To make the most of time blocking, consider the following techniques:

Identify Your Key Priorities:

Before you begin time blocking, identify your most important priorities. These may include research activities, writing, data analysis, teaching responsibilities, meetings, or personal development. By having a clear understanding of your priorities, you can allocate sufficient time to each area.

Determine Optimal Time Slots

Consider your energy levels, cognitive peaks, and natural rhythms when determining your time slots. Some individuals are more productive in the morning, while others thrive in the afternoon or evening. Find the time slots that work best for you and align them with tasks that require deep focus and concentration.

Block Focus Time

Designate uninterrupted periods for deep work and focused tasks. During these time blocks, eliminate distractions, such as turning off notifications, closing unnecessary tabs, and creating a conducive work environment.

Include Breaks

Recognize the importance of breaks and transition time between tasks. Schedule short breaks to recharge and refresh your mind. Additionally, allocate buffer time between tasks to allow for a smooth transition and avoid feeling rushed or overwhelmed.

Flexibility

While time blocking provides structure, it’s essential to remain flexible. Unexpected events or new tasks may arise, requiring adjustments to your schedule. Embrace the flexibility to rearrange your time blocks when necessary, ensuring that you stay responsive to changing priorities.

Remember, the goal of time blocking is not to fill every minute of your day with tasks. It’s about creating a balance between focused work, breaks, and other essential activities. By allocating specific time slots for each task or responsibility, you gain clarity on your commitments and avoid the pitfalls of multitasking.

Additionally, time blocking can help manage the tendency to overcommit. By allocating realistic time slots for tasks, you gain a better understanding of how much you can accomplish within a given timeframe. This practice prevents the stress and frustration that can arise from unrealistic expectations and allows you to set achievable goals.

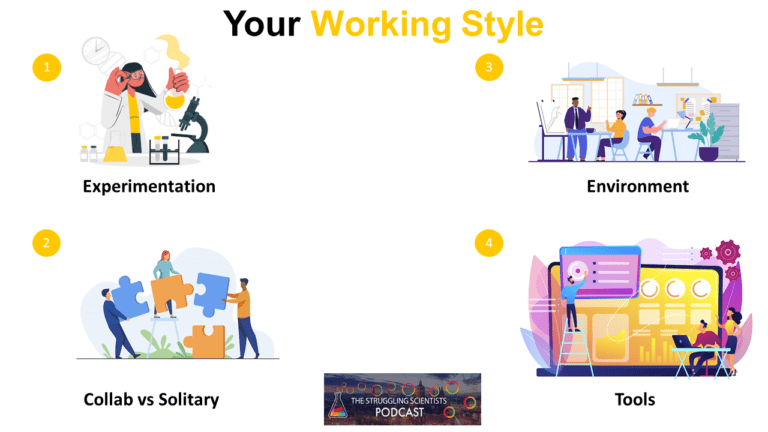

🛠️Discovering Your Optimal Working Style

Finding your optimal working style is crucial for enhancing productivity as a PhD student or academic. Each individual has unique preferences, strengths, and rhythms when it comes to work. By understanding and embracing your working style, you can tailor your approach to research and academic tasks, ultimately boosting your efficiency and output. Here are some key considerations to help you discover your optimal working style:

Experimentation

Don’t be afraid to experiment with different working styles and techniques. Try out various approaches such as the Pomodoro Technique, which involves working in focused sprints followed by short breaks, or deep work sessions where you dedicate uninterrupted time to intensive tasks. Evaluate the outcomes and determine what resonates with you the most.

Collaborative vs. Solitary Work

Consider whether you thrive in collaborative settings or if you perform better working independently. PhD students and academics often engage in team projects or research collaborations, but some tasks may require concentrated solitary work. Finding the right balance that suits your working style is essential for maintaining productivity.

Environmental Factors

Your physical work environment can have a significant impact on your productivity. Some individuals thrive in a quiet and organized space, while others prefer a bustling and interactive setting. Experiment with different environments, and create a workspace that promotes focus and minimizes distractions.

Workflow Tools

Explore productivity tools and technology that align with your working style. Digital tools like project management software, note-taking apps, or reference management systems can streamline your research process. Find tools that enhance your workflow and integrate seamlessly with your working preferences.

Remember, discovering your optimal working style is a continuous journey. As you progress through your academic career, your needs and preferences may evolve. Stay open to adapting and refining your approach to ensure it remains aligned with your goals and aspirations.

🍬 Rewarding Yourself While Working

Rewarding yourself while working can be a powerful motivator to overcome procrastination and maintain focus as a PhD student or academic. By incorporating intentional rewards into your work routine, you can create a positive reinforcement system that boosts your productivity and enhances your overall satisfaction. Here are some strategies to consider:

Milestone Celebrations

Break down your work into smaller milestones and celebrate each achievement along the way. For example, completing a section of a research paper, reaching a specific word count, or finishing a challenging experiment can all be acknowledged as milestones. Treat yourself to a small reward, such as a coffee break, a short walk, or a few minutes of enjoyable leisure activities.

Time-Based Rewards

Set specific time intervals during your work session, and reward yourself with short breaks or mini-rewards when you reach those intervals. This technique can be particularly effective when using the Pomodoro Technique, where you work for a set period, like 25 minutes, and then take a 5-minute break. Use these breaks to do something you enjoy, like reading a book, listening to music, or engaging in a brief mindfulness exercise.

Meaningful Incentives

Identify rewards that are personally meaningful and aligned with your interests or hobbies. This could be engaging in a favorite recreational activity, treating yourself to a delicious snack, or indulging in a leisurely activity you enjoy. The key is to choose rewards that bring you joy and provide a sense of rejuvenation and fulfillment.

Gamify Your Tasks

Turn your work into a game by setting up challenges or creating a points system. Assign point values to different tasks, and challenge yourself to accumulate a certain number of points within a specific timeframe. When you reach your goal, reward yourself with a prize or treat. This gamification approach adds an element of fun and excitement to your work, making it more engaging and enjoyable.

Social Accountability

Share your goals and progress with a trusted friend, colleague, or mentor. Establish a system of social accountability where you can celebrate your accomplishments together. This external validation and support can be a rewarding experience and provide an additional incentive to stay focused and productive.

Remember, the rewards you choose should be small, enjoyable, and in moderation. The purpose is to create positive associations with your work and maintain a healthy work-life balance. By incorporating rewards into your work routine, you can cultivate a positive mindset, boost your motivation, and reduce the likelihood of procrastination.

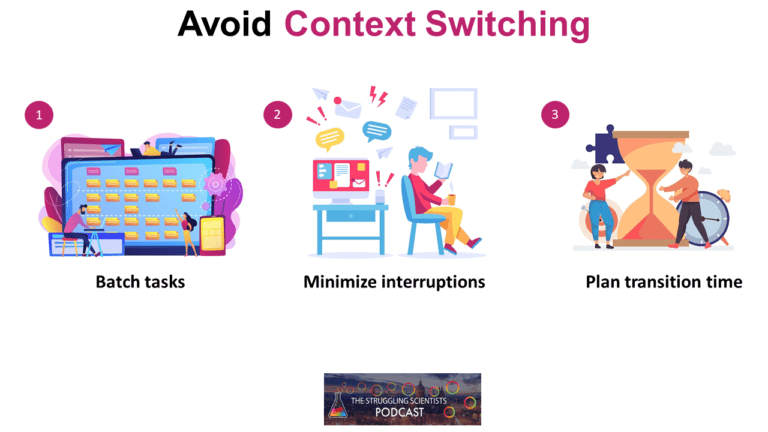

🕹️Avoiding Context Switching

Avoiding context-switching and cultivating mindfulness are essential practices for maximizing productivity and maintaining focus as a PhD student or academic. These strategies help minimize distractions, enhance concentration, and promote a sense of clarity and presence in your work. Here are some tips to minimize context switching:

Batch Similar Tasks

Group similar tasks together and allocate dedicated time blocks for them. For example, schedule a specific block of time for reading and responding to emails, another block for data analysis, and another for writing. By focusing on one type of task at a time, you reduce the need to constantly switch gears and maintain a higher level of efficiency.

Minimize Interruptions

Identify and eliminate sources of interruptions and distractions in your work environment. Silence or disable unnecessary notifications on your devices, inform colleagues or family members about your focused work time, and create boundaries to protect your uninterrupted work blocks.

Plan Transition Time

When switching between tasks or projects, allocate buffer time to mentally transition and prepare for the upcoming task. This allows you to wrap up one task effectively and transition smoothly to the next, minimizing the disruption to your focus and productivity.

🤯Conclusion

In the fast-paced world of academia, mastering productivity techniques is essential for PhD students and academics to thrive and achieve their goals. By implementing strategies such as creating a well-structured daily to-do list, practicing time blocking, finding what works for you, rewarding yourself while working, and avoiding context switching you can overcome procrastination, maintain focus, and maximize your productivity.

Remember, productivity is not a one-size-fits-all approach. It requires experimentation, self-reflection, and continuous refinement to find the strategies that work best for you as a PhD student or academic. Stay open to exploring new techniques and adapting your workflow as needed. The journey toward productivity is a personal one, and what works for others may not work the same for you.

As you apply these productivity principles, keep in mind the unique challenges and demands of being a PhD student or academic. Embrace your strengths, leverage your resources, and seek support from your peers, mentors, or productivity communities. Together, you can navigate the complexities of academic life and achieve remarkable results.

Ultimately, productivity is not just about getting more things done—it’s about creating a fulfilling and balanced academic experience. By optimizing your workflow, you can allocate time for your research, teaching, personal growth, and self-care. Remember to celebrate your accomplishments, maintain a healthy work-life balance, and prioritize your well-being along the way.

Now, armed with these productivity strategies and a commitment to action, it’s time to embark on your journey towards enhanced productivity as a PhD student or academic. Embrace the opportunities that lie ahead, stay focused on your goals, and make the most of your academic pursuits

Start by implementing one or two strategies from this blog, and gradually incorporate additional techniques into your routine. Remember, small steps can lead to significant improvements over time. Embrace the power of productivity and unleash your full potential as a successful PhD student or academic.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Other Posts you might like:

How to prepare PhD students for their career

Traditionally, PhDs are trained within academia with the perspective of landing an academic job. But

A Hitchhikers Guide to a PhD: Don’t panic!

For effective learning make sure you get enough sleep

We spend approximately one-third of our lives asleep. Despite the vast amount of time we

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Procrastinator's Guide to a PhD: How to overcome procrastination and complete your dissertation

Procrastinating is an occupational hazard of doing a PhD. But what if you already have procrastination issues? It’s one thing to start as a well-organised, diligent student and then lapse when faced with the lack of deadlines and accountability. It’s another to have been flying by the seat of your pants for the last several years, pulling all-nighters to finish assignments and cramming for exams. What to do? As a recovering procrastinator myself, with several decades of bad habits to overcome, I want to reassure you that change is possible! You can use your well-honed skill in mind games for good instead of evil. The happy news is that if you’ve made it this far, you’ve got all the brains you need to succeed—you just have to know what to do with them. At the end of the day, it’s perseverance, not brilliance, that will get you to your goal. Whether you have long dabbled in the dark art of procrastination or you’re a relative newcomer, you’ll find something here to help you achieve your PhD. Note: The focus of this book is on the thesis or dissertation, not on the coursework and qualifying exams which are part of doctoral studies in the USA.

Related Papers

Nhà thơ Quách Thoại viết bài Thược Dược: là hoa hay là người? Mới đọc, biết là hoa. Ngẫm nghĩ, hiểu là người. Nếu có thiếu nữ nào tên Dược thì sao? Hoặc trí tưởng tượng của nhà thơ cảm nhận, thân em mong manh như một cành hoa. Ai biết, thế nào? Ðứng im ngoài hàng dậu Em mỉm nụ nhiệm mầu Lặng nhìn em kinh ngạc Vừa thoáng nghe em hát Lời ca em thiên thâu Ta sụp lạy cúi đầu. (Thược Dược. Quách Thoại.)

Luise von Flotow

Stéphane Lamouille

Omar Gonzalez

Vipul Kiyada

Multiplier is one of the key hardware component in high performance system such as Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters and Digital Signal Processor (DSP). Multiplier consumes large chip area, long latency and consume considerable amount of power. Hence better multiplier architectures can increase the efficiency of the system. Multiplier based on Vedic mathematics is one such promising solution. For the multiplication, Urdhva Tiryagbhyam sutra and Nikhilam sutra is used from Vedic mathematics. The paper shows the design implementation and comparison of these multiplier using Verilog Hardware Description Language (HDL). The multiplier based on Urdhva Tiryagbhyam sutra reduces the execution time by maximum 58% and minimum 9% but Multiplier based on Nikhilam sutra reduces the execution time by minimum 13% compared to array multiplier and increases 87% compared to Wallace tree multiplier.

royshel vidal zavala

Javier de Carlos Izquierdo , Romina Fucà , Veronica Fincati , Altay A Manço , Francesco Rosiello

Nei prossimi decenni le migrazioni saranno più frequenti in conseguenza dei cambiamenti climatici, della povertà e dei conflitti. L'Unione Europea, la destinazione più ambita per i migranti, ha istituito un sistema per la gestione delle migrazioni definito "Approccio Integrato". Questo sistema si sforza di gestire la migrazione da una prospettiva globale che include i paesi di origine, transito e destinazione. Il volume pubblicato dalla casa Aracne Editrice promuove gli interessi della cooperazione internazionale, in particolare con gli Stati membri, gli attori e le parti interessate dell’Unione Europea, al fine di conoscere meglio e, per quanto possibile, rafforzare i sistemi territoriali e di sicurezza nell’area Schengen. Per leggere di più visita il seguente link: http://www.aracneeditrice.it/index.php/pubblicazione.html?item=9788825529500

Ryan Paetzold

International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences

zacharia Gnankambary

CADERNOS DE RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS

Mariana Caldas

RELATED PAPERS

28th AIAA International Communications Satellite Systems Conference (ICSSC-2010)

Minhyuk Kim

2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing

Christophe De Vleeschouwer

Ensino em Re-Vista

Ana Castaman

Adele Baruch

Journal of Iranian medical council

Esmaeil Mehraeen

Southeastern Philippines Journal of Research and Development

Rey Castillo

الأدب العربي من النهضة حتى اليوم di Isabella Camera D'Afflitto

Hussein Mahmoud

P. P R A V E E N KUMAR

Contemporary Behavioral Health Care

FR. DR. Elias K I N O T I Kithuri

Eugenia Isidro

brian nyatanga

Holly Wilson

Fitoterapia

BMC Nursing

Monica Eriksson

Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research

Rubén González-Rodríguez

Acta Zoologica Bulgarica

Atanas Irikov

2006 9th International Conference on Information Fusion

Trang Nguyen

British Educational Research Journal

Jocey Quinn

Michael Asare

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Cover Story

Why wait the science behind procrastination.

- Cognitive Psychology

- Emotional Control

- Personality/Social

Believe it or not, the Internet did not give rise to procrastination. People have struggled with habitual hesitation going back to ancient civilizations. The Greek poet Hesiod, writing around 800 B.C., cautioned not to “put your work off till tomorrow and the day after.” The Roman consul Cicero called procrastination “hateful” in the conduct of affairs. (He was looking at you, Marcus Antonius.) And those are just examples from recorded history. For all we know, the dinosaurs saw the meteorite coming and went back to their game of Angry Pterodactyls.

What’s become quite clear since the days of Cicero is that procrastination isn’t just hateful, it’s downright harmful. In research settings, people who procrastinate have higher levels of stress and lower well-being. In the real world, undesired delay is often associated with inadequate retirement savings and missed medical visits. Considering the season, it would be remiss not to mention past surveys by H&R Block, which found that people cost themselves hundreds of dollars by rushing to prepare income taxes near the April 15 deadline.

In the past 20 years, the peculiar behavior of procrastination has received a burst of empirical interest. With apologies to Hesiod, psychological researchers now recognize that there’s far more to it than simply putting something off until tomorrow. True procrastination is a complicated failure of self-regulation: experts define it as the voluntary delay of some important task that we intend to do, despite knowing that we’ll suffer as a result. A poor concept of time may exacerbate the problem, but an inability to manage emotions seems to be its very foundation.

“What I’ve found is that while everybody may procrastinate, not everyone is a procrastinator,” says APS Fellow Joseph Ferrari, a professor of psychology at DePaul University. He is a pioneer of modern research on the subject, and his work has found that as many as 20 percent of people may be chronic procrastinators.

“It really has nothing to do with time-management,” he says. “As I tell people, to tell the chronic procrastinator to just do it would be like saying to a clinically depressed person, cheer up .”

Suffering More, Performing Worse

A major misperception about procrastination is that it’s an innocuous habit at worst, and maybe even a helpful one at best. Sympathizers of procrastination often say it doesn’t matter when a task gets done, so long as it’s eventually finished. Some even believe they work best under pressure. Stanford philosopher John Perry, author of the book The Art of Procrastination , has argued that people can dawdle to their advantage by restructuring their to-do lists so that they’re always accomplishing something of value. Psychological scientists have a serious problem with this view. They argue that it conflates beneficial, proactive behaviors like pondering (which attempts to solve a problem) or prioritizing (which organizes a series of problems) with the detrimental, self-defeating habit of genuine procrastination. If progress on a task can take many forms, procrastination is the absence of progress.

“If I have a dozen things to do, obviously #10, #11, and #12 have to wait,” says Ferrari. “The real procrastinator has those 12 things, maybe does one or two of them, then rewrites the list, then shuffles it around, then makes an extra copy of it. That’s procrastinating. That’s different.”

One of the first studies to document the pernicious nature of procrastination was published in Psychological Science back in 1997. APS Fellow Dianne Tice and APS William James Fellow Roy Baumeister, then at Case Western Reserve University, rated college students on an established scale of procrastination, then tracked their academic performance, stress, and general health throughout the semester. Initially there seemed to be a benefit to procrastination, as these students had lower levels of stress compared to others, presumably as a result of putting off their work to pursue more pleasurable activities. In the end, however, the costs of procrastination far outweighed the temporary benefits. Procrastinators earned lower grades than other students and reported higher cumulative amounts of stress and illness. True procrastinators didn’t just finish their work later — the quality of it suffered, as did their own well-being.

“Thus, despite its apologists and its short-term benefits, procrastination cannot be regarded as either adaptive or innocuous,” concluded Tice and Baumeister (now both at Florida State University). “Procrastinators end up suffering more and performing worse than other people.”

A little later, Tice and Ferrari teamed up to do a study that put the ill effects of procrastination into context. They brought students into a lab and told them at the end of the session they’d be engaging in a math puzzle. Some were told the task was a meaningful test of their cognitive abilities, while others were told that it was designed to be meaningless and fun. Before doing the puzzle, the students had an interim period during which they could prepare for the task or mess around with games like Tetris. As it happened, chronic procrastinators only delayed practice on the puzzle when it was described as a cognitive evaluation. When it was described as fun, they behaved no differently from non-procrastinators. In an issue of the Journal of Research in Personality from 2000, Tice and Ferrari concluded that procrastination is really a self-defeating behavior — with procrastinators trying to undermine their own best efforts.

“The chronic procrastinator, the person who does this as a lifestyle, would rather have other people think that they lack effort than lacking ability,” says Ferrari. “It’s a maladaptive lifestyle.”

A Gap Between Intention and Action

There’s no single type of procrastinator, but several general impressions have emerged over years of research. Chronic procrastinators have perpetual problems finishing tasks, while situational ones delay based on the task itself. A perfect storm of procrastination occurs when an unpleasant task meets a person who’s high in impulsivity and low in self-discipline. (The behavior is strongly linked with the Big Five personality trait of conscientiousness.) Most delayers betray a tendency for self-defeat, but they can arrive at this point from either a negative state (fear of failure, for instance, or perfectionism) or a positive one (the joy of temptation). All told, these qualities have led researchers to call procrastination the “quintessential” breakdown of self-control.

“I think the basic notion of procrastination as self-regulation failure is pretty clear,” says Timothy Pychyl of Carleton University, in Canada. “You know what you ought to do and you’re not able to bring yourself to do it. It’s that gap between intention and action.”

Social scientists debate whether the existence of this gap can be better explained by the inability to manage time or the inability to regulate moods and emotions. Generally speaking, economists tend to favor the former theory. Many espouse a formula for procrastination put forth in a paper published by the business scholar Piers Steel, a professor at the University of Calgary, in a 2007 issue of Psychological Bulletin . The idea is that procrastinators calculate the fluctuating utility of certain activities: pleasurable ones have more value early on, and tough tasks become more important as a deadline approaches.

Psychologists like Ferrari and Pychyl, on the other hand, see flaws in such a strictly temporal view of procrastination. For one thing, if delay were really as rational as this utility equation suggests, there would be no need to call the behavior procrastination — on the contrary, time-management would fit better. Beyond that, studies have found that procrastinators carry accompanying feelings of guilt, shame, or anxiety with their decision to delay. This emotional element suggests there’s much more to the story than time-management alone. Pychyl noticed the role of mood and emotions on procrastination with his very first work on the subject, back in the mid-1990s, and solidified that concept with a study published in the Journal of Social Behavior and Personality in 2000. His research team gave 45 students a pager and tracked them for five days leading up to a school deadline. Eight times a day, when beeped, the test participants reported their level of procrastination as well as their emotional state. As the preparatory tasks became more difficult and stressful, the students put them off for more pleasant activities. When they did so, however, they reported high levels of guilt — a sign that beneath the veneer of relief there was a lingering dread about the work set aside. The result made Pychyl realize that procrastinators recognize the temporal harm in what they’re doing, but can’t overcome the emotional urge toward a diversion.

A subsequent study, led by Tice, reinforced the dominant role played by mood in procrastination. In a 2001 issue of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , Tice and colleagues reported that students didn’t procrastinate before an intelligence test when primed to believe their mood was fixed. In contrast, when they thought their mood could change (and particularly when they were in a bad mood), they delayed practice until about the final minute. The findings suggested that self-control only succumbs to temptation when present emotions can be improved as a result.

“Emotional regulation, to me, is the real story around procrastination, because to the extent that I can deal with my emotions, I can stay on task,” says Pychyl. “When you say task-aversiveness , that’s another word for lack of enjoyment. Those are feeling states — those aren’t states of which [task] has more utility.”

Frustrating the Future Self

In general, people learn from their mistakes and reassess their approach to certain problems. For chronic procrastinators, that feedback loop seems continually out of service. The damage suffered as a result of delay doesn’t teach them to start earlier the next time around. An explanation for this behavioral paradox seems to lie in the emotional component of procrastination. Ironically, the very quest to relieve stress in the moment might prevent procrastinators from figuring out how to relieve it in the long run.

“I think the mood regulation piece is a huge part of procrastination,” says Fuschia Sirois of Bishop’s University, in Canada. “If you’re focused just on trying to get yourself to feel good now, there’s a lot you can miss out on in terms of learning how to correct behavior and avoiding similar problems in the future.”

A few years ago, Sirois recruited about 80 students and assessed them for procrastination. The participants then read descriptions of stressful events, with some of the anxiety caused by unnecessary delay. In one scenario, a person returned from a sunny vacation to notice a suspicious mole, but put off going to the doctor for a long time, creating a worrisome situation.

Afterward, Sirois asked the test participants what they thought about the scenario. She found that procrastinators tended to say things like, “At least I went to the doctor before it really got worse.” This response, known as a downward counterfactual , reflects a desire to improve mood in the short term. At the same time, the procrastinators rarely made statements like, “If only I had gone to the doctor sooner.” That type of response, known as an upward counterfactual , embraces the tension of the moment in an attempt to learn something for the future. Simply put, procrastinators focused on how to make themselves feel better at the expense of drawing insight from what made them feel bad.

Recently, Sirois and Pychyl tried to unify the emotional side of procrastination with the temporal side that isn’t so satisfying on its own. In the February issue of Social and Personality Psychology Compass , they propose a two-part theory on procrastination that braids short-term, mood-related improvements with long-term, time-related damage. The idea is that procrastinators comfort themselves in the present with the false belief that they’ll be more emotionally equipped to handle a task in the future.

“The future self becomes the beast of burden for procrastination,” says Sirois. “We’re trying to regulate our current mood and thinking our future self will be in a better state. They’ll be better able to handle feelings of insecurity or frustration with the task. That somehow we’ll develop these miraculous coping skills to deal with these emotions that we just can’t deal with right now.”

The Neuropsychology of Procrastination

Recently the behavioral research into procrastination has ventured beyond cognition, emotion, and personality, into the realm of neuropsychology. The frontal systems of the brain are known to be involved in a number of processes that overlap with self-regulation. These behaviors — problem-solving, planning, self-control, and the like — fall under the domain of executive functioning . Oddly enough, no one had ever examined a connection between this part of the brain and procrastination, says Laura Rabin of Brooklyn College.

“Given the role of executive functioning in the initiation and completion of complex behaviors, it was surprising to me that previous research had not systematically examined the relationship between aspects of executive functioning and academic procrastination — a behavior I see regularly in students but have yet to fully understand, and by extension help remediate,” says Rabin.

To address this gap in the literature, Rabin and colleagues gathered a sample of 212 students and assessed them first for procrastination, then on the nine clinical subscales of executive functioning: impulsivity, self-monitoring, planning and organization, activity shifting, task initiation, task monitoring, emotional control, working memory, and general orderliness. The researchers expected to find a link between procrastination and a few of the subscales (namely, the first four in the list above). As it happened, procrastinators showed significant associations with all nine , Rabin’s team reported in a 2011 issue of the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology .

Rabin stresses the limitations of the work. For one thing, the findings were correlative, meaning it’s not quite clear those elements of executive functioning caused procrastination directly. The assessments also relied on self-reports; in the future, functional imaging might be used to confirm or expand the brain’s delay centers in real time. Still, says Rabin, the study suggests that procrastination might be an “expression of subtle executive dysfunction” in people who are otherwise neuropsychologically healthy.

“This has direct implications for how we understand the behavior and possibly intervene,” she says.

Possible Interventions

As the basic understanding of procrastination advances, many researchers hope to see a payoff in better interventions. Rabin’s work on executive functioning suggests a number of remedies for unwanted delay. Procrastinators might chop up tasks into smaller pieces so they can work through a more manageable series of assignments. Counseling might help them recognize that they’re compromising long-term aims for quick bursts of pleasure. The idea of setting personal deadlines harmonizes with previous work done by behavioral researchers Dan Ariely and Klaus Wertenbroch on “precommitment.” In a 2002 issue of Psychological Science , Ariely and Wertenbroch reported that procrastinators were willing to set meaningful deadlines for themselves, and that the deadlines did in fact improve their ability to complete a task. These self-imposed deadlines aren’t as effective as external ones, but they’re better than nothing.

The emotional aspects of procrastination pose a tougher problem. Direct strategies to counter temptation include blocking access to desirable distraction, but to a large extent that effort requires the type of self-regulation procrastinators lack in the first place. Sirois believes the best way to eliminate the need for short-term mood fixes is to find something positive or worthwhile about the task itself. “You’ve got to dig a little deeper and find some personal meaning in that task,” she says. “That’s what our data is suggesting.”

Ferrari, who offers a number of interventions in his 2010 book Still Procrastinating? The No Regrets Guide to Getting It Done , would like to see a general cultural shift from punishing lateness to rewarding the early bird. He’s proposed, among other things, that the federal government incentivize early tax filing by giving people a small break if they file by, say, February or March 15. He also suggests we stop enabling procrastination in our personal relationships.

“Let the dishes pile up, let the fridge go empty, let the car stall out,” says Ferrari. “Don’t bail them out.” (Recent work suggests he’s onto something. In a 2011 paper in Psychological Science , Gráinne Fitzsimons and Eli Finkel report that people who think their relationship partner will help them with a task are more likely to procrastinate on it.)

But while the tough love approach might work for couples, the best personal remedy for procrastination might actually be self-forgiveness. A couple years ago, Pychyl joined two Carleton University colleagues and surveyed 119 students on procrastination before their midterm exams. The research team, led by Michael Wohl, reported in a 2010 issue of Personality and Individual Differences that students who forgave themselves after procrastinating on the first exam were less likely to delay studying for the second one.

Pychyl says he likes to close talks and chapters with that hopeful prospect of forgiveness. He sees the study as a reminder that procrastination is really a self-inflicted wound that gradually chips away at the most valuable resource in the world: time.

“It’s an existentially relevant problem, because it’s not getting on with life itself,” he says. “You only get a certain number of years. What are you doing?”

I am writing my seventh speech for my Toastsmasters meeting and I am speaking about procrastination. This article provided me with great research and information about this subject. Thanks.

I too am writing my 7th speech for Toastmasters on the same subject. Hope yours went well. Mine is due tomorrow!

Me too! 7th ToastMaster Speech. I’ve procrastinated over every speech topic so far, so decided to research into the meaning of my procrastination to overcome the problem. Hence, it has become the topic for my speech!This article has been very informative.

mis hijos lo padecen. Como ayudar a mis hijos esta de pormedio su vida.

this could be a great article to use for one of my classes.

As a counselor, this article is powerful. I don’t think I will ever be stuck with a client who presents procastination as a distress issue.

Thanks Eric for publishing this

I’m currently researching an apt second show topic behind the science of procrastination and this has been quite helpful.

I’ll be sure to send my listeners this way.

People say that procrastination reduces the productivity. But scientifically it actually increases the productivity. People tend to work more and try to be more productive in the last few hours before the deadline. On the other hand, it also increases the internal stress. So it is better to avoid procrastination for a perfect work-life balance. To avoid procrastination, I chose Habiliss virtual assistant services, which really helped me in increasing my productivity.

it helped me so much to write my essay and it has so many information, thanks.

My daughter belongs to the type of people who will procrastinate or avoid anything that implies making an effort. Or she will start something and leave it unfinished to do something else. I don’t know what to do, rowing just makes things worse.

tell her this steps: 1. Chop the whole task in small pieces. 2. Observe the small task very deeply. 4. make a mind map of how you are going to do it. 3. make an expected and meaningful deadline’ 4. and most importantly try to visualize the small tasks you are completing before the deadline.

Interesting that no procrastinators have posted. Does that demonstrate the guilt and shame they feel for wasting their lives?

Hello Christina, I’ve been waiting a year to reply to you comment in order to maximize my creativity in doing so. Uhm wait, Catfish just came on and it’s a really good episode! I’ll get back to you about the gilt and shame another day, hope you understand.

Comments from a procrastinator; I don’t know what to say. It is so stressful to always feel like you are behind the eight ball. I have always taken on a little more than most sensible people would. So, I set myself up from the get go. I have a long history of depression, so when I get depressed, my chores, projects, whatever seem to be too heavy to deal with. I have a totally unrealistic sense of time. I am chronically late. As I have gotten older, this has gotten worse.My career was mostly in nursing management, which worked out for me because I didn’t have an exact time to be at work unless I had meetings. I often stayed late to finish projects when everyone was gone for the day and I could focus in total peace and quiet. Of course, when I worked late, I felt the inner guilt of neglecting my family. I am almost 70, raising 2 grandchildren and unable to find the peace and quiet or the time to work on the projects I saved for retirement. This was voluntary and I really felt I could give them the best environment for their special needs. So, maybe I have given myself an acceptable, selfless reason to procrastinate. But, it only makes me feel more stressed. I really want to be relaxed, happy and unstressed.

I’m right there with you, Elyse. I wonder if anyone has ever studied procrastination from the perspective of someone who just perpetually takes on more than they can handle. I’m so sick of it. I’m a PhD student and I see peers turning things in early and I’m always last. It’s a horrible feeling. My work is usually very good, but almost always late. I empathize with you and hope that we can both beat this problem soon.

Well…Sometimes thing come into my life to make my nightmares a bit more manageable. This article showed me the STRONG effect that emotions have on procrastination. I identified with every single thing in it and I am grateful I came across it.

Finally, I begin to understand the psychology behind my chronic procrastination. My levels of distraction are such that I rarely get through an article without feeling like I must be doing something else. Not this one. Words and phrases that leaped off the page (screen) to me were “self-defeating behavior”, “intention” vs. “action”, “self-regulating”. True. True. True. Now I must delve into my belief system to pull out the reasons why these negative behaviors take precedence over those that are far more positive. Clearly, I feel I am getting some benefit out of my self-defeating behavior or else why repeat it? I’ll have to be careful when attempting to reason this out though. I AM a ponder-er by nature which means I tend to over-think to the degree that by the time I believe I understand my ‘whys’, the opportunity for action has already passed. The irony in this is that my pondering IS procrastinating.

Countless times I have wanted desperately to attach my inability to move forward in my tasks, projects, etc. to the fact that I’m just lousy at managing my time. And then I read this:

“It really has nothing to do with time-management,” he says. “As I tell people, to tell the chronic procrastinator to just do it would be like saying to a clinically depressed person, cheer up.”

THANK YOU! This explains why every single Day Planner I’ve ever attempted to use failed so miserably. Bullet Journals? Ha! Nope. Productivity Apps? Not for me. I confess to being inadequate at anything that requires planning. Planning, then, requires taking the time to sit quietly and write out some kind of an action plan. Action plans require lists. Lists become my number one enemy. It’s at times like this that I feel It’s an almost physical reaction that comes over me when I force myself to think through to the natural end of an action. This snowballs into an overwhelming sense of confusion. My thoughts begin to scramble which triggers my impulse to get up and distract myself with something that will return an immediate sense of accomplishment. “I need to water my plants”.

Has anyone else experienced this? Does all this mean I am now officially becoming OCD? ADD?

I work full-time in a position that requires intense focus (which I love) but also requires that I am organized enough to prioritize my daily workload. It’s as though I recognize the importance of this but I feel I constantly fall short due to that sense of confusion that distracts me (remember that list thing?) and I end up just ‘winging’ it in order to complete the task. I’ve been known to work overtime (w/o pay) just to feel I’ve accomplished what I should have done all day. I have been known to work 10-12 hour workdays which, I realize, is simply ridiculous. And then begins that cycle of negative feelings: unproductive, inadequate, guilt, shame…etc. To say it is exhausting on all levels would be a gross understatement.

Perhaps you can point me (us) to articles that will help me begin to better understand — and help to end — such cycles of negative patterns.

Thank you for addressing the psychology of procrastination. It’s as though my name was written all over it.

I’m similar, I think, since I’ve wanted to only get things done perfectly or I’d see myself as a total failure. Avoiding trying to take care of this test, etc., means my not wanting to face seeing myself as a failure. I never expected to do anything as good as it should be. I’ve always suffered from a strong fear of rejection… I have been linked with AvPD, DPD, OCD, GAD, depression, bulimia, perf ectionism, agoraphobia… According to a psychiatrist, I saw things only in extremes, i.e. all or nothing, good or bad, black or white… I now have to believe, that according to tests run by this current psychiatrist that I suffer from Asperger’s Syndrome… I have been put under the 1% of the population with memory but I do not remember any of my growing up years… Only faced accepting someone as a friend at the age of 28. I saw her as a guardian angel…

Ditto. I wrote a post I aim to publish on the subject. I was the worst procrastinator. When I ceased depriving myself of all the things I love to do. It made it easier to tackle any task I dreaded. Try to strike a balance between work and play. Familiarise yourself with prioritizing important and urgent tasks. And getting them done. Focus a little more on the future, of where you’d like to see yourself. It’ll help you get past the immediate feeling of anxiety. The emotion that underlies the prolonged periods of procrastination the chronic procrastinator is prone to feeling.

Wow this was great how they took this one concept that sometimes cripples most of us, and turned it into a science! Wonderful and highly informative reading! I even posted this to Facebook!

Amazing article, lot of research and efforts, thanks for sharing this abundance of information

WOW!! This was an extremely helpful AND educational article! And I think I can speak for many! And I thank all the contributors to this piece who offered there insight along with case studies that actually break down this human nemesis that has plagued the human race since man learned to walk upright! But there is one thing that I do that most other people do and maybe you could do an article on this subject also. And that is impulsivity. Before I finish one task I jump to do something else! I am just now learning to recognize mine, and am making a strong effort to an alias and correct it.

WOW! This was quite an article! Never before have I read anything so descriptive about a long time human nemesis such as this, what it actually is and how it can be dealt with. I certainly did not know that this is an issue that dates back hundred of years before Jesus Christ was born! But not until now has this problem been looked at and broken down. I will definitely apply these principles! Thank you!

This article is more helpful than others I have read, but my own reasons for procrastination are still elusive to me. Sometimes I will work on a project for a little while, which relieves anxiety. Then I set it aside, saying that I want to see it with fresh eyes a day or two later. Other times I have had the experience of doing something too early, like prepping a presentation, and when I go to make it, I have lost the train of thought. Some tasks are just boring, like many household chores, or present a knotty problem which I just don’t feel like dealing with. Oddly enough, I have no trouble downloading bank and credit card statements and balancing the checkbook. I think it’s the short term pleasure of knowing my finances are in order, even if I still owe money on something, at least the numbers are going down.

Very interesting and educating article with so much research. Thanks for putting this together

I really liked this article. I’ve been going thru a mid life crisis because of a battle I have with chronic procrastination. Like many of the others I read above it’s not one thing it’s many different emotions one has to deal with while h in turn leads one to live one very stressful life. I have a deadline at midnight tonight for something I’ve been wanting/needing to do for a couple months now. Just by reading this article and seeing that I am not alone in this fight has given me the desire to get it done! I pray that everyone that struggles with this nemesis gets closer to defeating our life long enemy. Never give up!

Whoa. I’m writing a speech for school on procrastination, since I have been a chronic procrastinator for pretty much as long as I can remember. I hit an all time low at one point, where I basically never did my homework. For many years, I tried and failed to come up with a reason for that. I very much enjoyed school and my work, I was more than capable of completing the work, and I did have enough time on my hands. I have concluded that the only plausible reason is that, like now, there is something in my brain that simply cannot get work done. When I read the comparison between telling a chronic procrastinator to “get it done” and a clinically depressed person to “cheer up” I was shocked. People never seemed to understand how much I desperately want to be able to just get it done. Even the act of procrastinating is not enjoyable in the slightest – I feel too guilty and self-loathing. I have looked at a number of resources for my speech regarding why we procrastinate, and have disagreed with every one, knowing that I did not fall under those reasons. I agreed with Every. Single. Thing. mentioned in this article. Whoa. Where has this been all my life.

P.S. – if you, like me, are a chronic procrastinator I would very much recommend a brief TedTalk entitled “Inside the Mind of a Master Procrastinator”. Blew me away.

Thank you so so much for your work. Reading this article helps me feel that I’m not alone. Procrastination is a thief, a liar, a destroyer. I’m in midlife now and I’m seeing how much procrastination has stolen from me, I’ve let it and now I live with the consequences of dreams unfulfilled and shattered. My quilt literally leaves me in a state of numbness and it’s like I’m frozen and not moving forward. Slowly, through prayer and acceptance through my faith, I’m realizing that, and this is key: that forgiving myself and knowing that God loves me unconditionally that I can move forward. I thank God for people like you that are able to gather info and better help all of us.

Everything is coming together now, I now know why I am the way that I am. Thank you so much for this article

I just turned 60. Since my 30s I’ve not been able to keep table surfaces clean of piled up mail, papers, etc. I clean it off and slowly over time it magically piles up again. I want my home to be clutter free but can’t keep up with it, or am I putting off cleaning? I’m always too busy and find activities to do that keep me from taking care of my home. Setting aside time, marking days on the calendar don’t always work either. Am I just lazy? I work better at keeping my home cleaned up when someone is there helping me. Anyone else feel this way?

its a wakeup call for me,such an eye opener

It’s really frustrating, this procrastination thing. My procrastination started to get worse from the day I began doing my practical research. I am unsure but it felt overwhelming (because researches are usually long, I think that is why) and because of that, I.. procrastinated. I watched youtube most of the time when I get home even though I’m aware that I should be doing my research. I tried to fight it off for several months. I’ve won over my procrastination stuff but it keeps coming back. It’s been a little over a year now and getting worse. I try to find my way out of this because it severely affects my academic performance and my social life. I am still finding my way out of this by doing research on procrastination.. (kind of ironic considering that my procrastination habits kicked off due to practical research).. Anyway, I wish the very best for anyone who is struggling with procrastination.. I wish the best for myself too…

Mind-blowing! I am finally able to understand a big part of why I procrastinate and I now feel there is hope. For example, I felt immensely relieved when I read the comparison between a chronic procrastinator and a depressed person; a heavy weight was lifted off my chest -which is pretty much always in agony because of all the tasks and projects postponed. So there is hope.

Dianne, I feel you. Your pain is my pain. Let’s hope this insightful article will help us get better. In my case, the positive emotions clearly help me stay on task, so, when I catch myself procrastinating out of control, I engage in a lifting and energizing short activity to change my mood. At the end of it, and without stopping for anything, I’ll get started on the task/project. I find myself immersed in the task (I am doing it, yeay!), and I feel happy for what I accomplished. That positive loop can keep me going for a little while….until I see a fly on the wall and my mind gets lost on something else. Thanks to this ‘technique’ I have accomplished diminishing the paralysing effects of the guilt. I have accomplished accepting the reality of the time lost and the work not done. I am accepting that whatever feeling I am feeling about procrastinating, THAT WILL ALSO PASS. I am accepting that I can change my emotional apporach to the task and that allows me to start on the positive loop all over. Slowly, yes, I am learning that I am not exactly repeating the same behaviour over and over. It’s taken me 30 years of adult life to get here but I’m improving and now I’m understanding more. Id say this is good.

Thank you for this article. I’ll read it later.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Author

Eric Jaffe is a regular Observer contributor and author of The King’s Best Highway: The Lost History of the Boston Post Road, the Route That Made America (Scribner, 2010).

Does Psychology Need More Effective Suspicion Probes?

Suspicion probes are meant to inform researchers about how participants’ beliefs may have influenced the outcome of a study, but it remains unclear what these unverified probes are really measuring or how they are currently being used.

Science in Service: Shaping Federal Support of Scientific Research

Social psychologist Elizabeth Necka shares her experiences as a program officer at the National Institute on Aging.

A Very Human Answer to One of AI’s Deepest Dilemmas

Imagine that we designed a fully intelligent, autonomous robot that acted on the world to accomplish its goals. How could we make sure that it would want the same things we do? Alison Gopnik explores. Read or listen!

Privacy Overview

How to Stop Procrastinating and Complete Your PhD Thesis: 10 Strategies to Consider

Jun 25, 2020

Remember the old saying, “Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today?” It’s easier said than done when it comes to writing your PhD thesis. Considering 80 to 95 per cent of college students procrastinate, you’re far from alone.

While there’s comfort in this statistic, it won’t help you finish your PhD thesis. There are many reasons for PhD thesis procrastination. They include a lack of support, difficulty setting priorities, the challenges of working from home, and more.

Despite these pitfalls, you can get from a blank page to a committee-ready document faster than you might think. Keep reading for ten tips that outline how to avoid procrastinating when writing your PhD.

Interested in group workshops, cohort-courses and a free PhD learning & support community?

The team behind The PhD Proofreaders have launched The PhD People, a free learning and community platform for PhD students. Connect, share and learn with other students, and boost your skills with cohort-based workshops and courses.

Why we procrastinate.

Understanding why we procrastinate will help you overcome this negative tendency. What’s the number one reason many PhD students delay dissertation writing? Self-doubt.

Graduate students have many fears. They include concerns about performing inadequately and failing to meet expectations.

Students also procrastinate because they underestimate how long different steps in their dissertation will take to complete. Some assume they must feel “inspired” before they can write. They fail to realise that writing is a skill that requires daily practice.

Others overestimate how motivated they will be later on. They also mistakenly believe they must be in the right frame of mind to work. Waiting to “feel ready” to write a dissertation will never happen, though. Nevertheless, this false assumption can trigger a vicious cycle.

Finally, procrastination proves a common problem for individuals who have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Why? An unhealthy level of perfectionism often accompanies OCD.

This perfectionism can prove paralysing when students become afraid to make mistakes, take chances, or do anything that might not turn out perfectly.

No matter why you’re procrastinating, the following tips will help you get back on track for success.

1) Set Priorities and Stick to Them

Procrastination can take many shapes and forms. One of the most insidious remains putting off urgent matters to complete menial tasks of lower priority.

Why do we do this? Because humans are hardwired to seek out instant gratification.

That’s what completing little tasks gives you. Besides delaying urgent tasks for the sake of non-urgent ones, procrastination can also take the shape of setting aside unpleasant, challenging jobs in favour of fun ones.

Again, these fun jobs often do little to help us complete anything of urgency. Perhaps the reason it’s so easy to get caught up in this form of procrastination is because it will keep you busy. It may even give you a fleeting sense of accomplishment until you start ruminating over your dissertation again.

2) Manage Distractions

How do you avoid mixed up priorities? By scheduling a time or day to take care of these minor tasks. Call it an “admin day” or a “detail day.” No matter what moniker you give it, dedicate a limited amount of time to efficiently and quickly completing these minor tasks.

Now that you’ve designated a day on your calendar for tidying up loose ends, create a dedicated “to-do” list. Then, every time something that you need to do pops into your head, add it to the list.

You’ll prevent distraction by knowing you’ve scheduled a time to address these minor concerns. This approach will allow you to concentrate on your dissertation.

3) Establish a Support Network

When it comes to avoiding PhD procrastination, you need a strong support network in place. After all, it’s easy to get distracted by well-meaning colleagues and friends. Don’t be afraid to set boundaries, too.

By sharing a civilised conversation about what you do and don’t need to focus on right now, you also avoid a build-up of potential awkwardness and tension. Explain your difficulties with concentrating and how they can help you.

4) Get Over the Romance of Working From Home

Working from home is idealised by many, yet the reality proves far from perfect. It can feel quite challenging to concentrate while in a space usually reserved for fun times and leisure activities.

What’s more, your home represents the ultimate obstacle course when it comes to trivial matters you should put off until later (but don’t). Whether it’s dishes left in the sink or dusting that needs to be done, staying at home can exacerbate procrastination through distractions.

Your PhD Thesis. On one page.

5) make peer pressure your ally.

Fortunately, when you surround yourself with others who may be working or writing, you gain a boost in productivity. After all, productivity is contagious. Find a great coffee shop with remote worker energy and let the “peer pressure” around you reignite your creative spark and energy.

6) Know Your Limits

Did you know that the average attention span is just 20 minutes? Sure, individuals can force themselves to focus on one subject for much longer. Nonetheless, peak productivity time still comes in 20-minute chunks.

Stop trying to force yourself into binge cycles of research and writing. Instead, understand your limitations and schedule accordingly. Plan your day with small breaks in mind when you need them most, and you’ll avoid distraction and frustration.

7) Take Advantage of Productivity Software

What’s productivity software? The ultimate answer to procrastination. This software lets you block sites that typically distract from work at hand. Whether it’s Netflix or Facebook, BBC News or Instagram, taking away temptation will help you get more done.

There are many different types of productivity software out there, but one of my favourites remains Cold Turkey. It completely cuts you off from the civilised world for a length of time that you determine. Yes, the experience can feel daunting, but you’ll be amazed by how much you get done.

8) Treat Your Body Well

PhD thesis writing can take a toll on your body if you let it. This reality can lead to a vicious cycle of getting sick, trying to catch up, burning out, and getting sick again. How about we agree to avoid this cycle from the get-go?

Eating right, sleeping well, drinking enough water, and exercising might seem like luxuries you don’t have time for right now. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Your brain works better when you treat your body right, and you need a working brain to write a dissertation.

9) Gain Confidence

When you’re not sure about your writing prowess or what makes for a fantastic dissertation, this uncertainty can impact your productivity. Fortunately, there are a wide variety of free resources available to help you create a finished product of which you’ll feel proud.

Check out these free guides to improve the quality of your writing, boost your motivation, and help you stay sane throughout the PhD dissertation writing process.

10) Get Structured

Many PhD students have questions related to properly structuring their dissertations. Again, a lack of clarity in any area of the process can lead to stilted creativity. So, you need to iron out these issues right away.

If you’re looking for guidance when it comes to planning and structuring your work, check out this resource for templates, chapter cheat sheets, and other thesis writing tips.

While you’re there, don’t forget to sign up for the daily PhD newsletter featuring helpful tips for how to write a doctoral thesis.

Dealing With PhD Thesis Procrastination

Are you struggling with PhD thesis procrastination? If so, you’re not alone. That said, now’s the time to get proactive about finding solutions to put you back in control of your educational path.

Fortunately, we can help. We offer expert support to help you with your PhD journey. Contact us to discuss where you are in your PhD thesis writing process and how we can help.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Share this:

Submit a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JAMA Network

Associations Between Procrastination and Subsequent Health Outcomes Among University Students in Sweden

Fred johansson.

1 Department of Health Promotion Science, Sophiahemmet University, Stockholm, Sweden

Alexander Rozental

2 Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

3 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Klara Edlund

4 Unit of Intervention and Implementation Research for Worker Health, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Pierre Côté

5 Institute for Disability and Rehabilitation Research and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ontario Tech University, Oshawa, Ontario, Canada

Tobias Sundberg

Clara onell.

6 Department of Caring Sciences, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden

Eva Skillgate

Accepted for Publication: November 13, 2022.

Published: January 4, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49346

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Johansson F et al. JAMA Network Open .

Author Contributions: Mr Johansson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Johansson, Edlund, Côté, Rudman, Skillgate.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Johansson, Rozental, Côté, Sundberg, Onell, Skillgate.

Drafting of the manuscript: Johansson, Edlund, Côté, Sundberg, Skillgate.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Johansson, Côté.

Obtained funding: Rudman, Skillgate.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Edlund, Sundberg, Onell.

Supervision: Rozental, Edlund, Côté, Sundberg, Rudman, Skillgate.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Mr Johansson and Drs Edlund, Sundberg, and Skillgate reported receiving grants from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This research project was funded by grant number FORTE2018-00402 from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE). The Sustainable University Life study also received financial support from the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

Additional Contributions: We would also like to express our appreciation to ACTIC (health club chain), the Tim Bergling Foundation, and all the participating students for their contribution to the Sustainable University Life study.

Associated Data

eTable 1. Comparisons of Estimates Under Different Adjustments

eTable 2. Characteristics of Participants at Pre-baseline Stratified by Missingness at the Nine-Month Follow-up

eMethods 2. Sensitivity Analysis Controlling for Prior Levels of Procrastination

eTable 3. Procrastination (T3) and Subsequent Health Outcomes Six Months Later (T5), Adjusted for Prior Levels of Procrastination (T2)

eMethods 3. Sensitivity Analysis for the Imputation of the Three Missing Items on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory

eReferences

Is procrastination associated with subsequent health outcomes among university students?

In this cohort study of 3525 Swedish university students, procrastination was associated with worse subsequent mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress symptom levels), having disabling pain in the upper extremities, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality and physical inactivity), and worse levels of psychosocial health factors (higher loneliness and more economic difficulties).

This study suggests that procrastination may be associated with a range of health outcomes.

Procrastination is prevalent among university students and is hypothesized to lead to adverse health outcomes. Previous cross-sectional research suggests that procrastination is associated with mental and physical health outcomes, but longitudinal evidence is currently scarce.

To evaluate the association between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes among university students in Sweden.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was based on the Sustainable University Life study, conducted between August 19, 2019, and December 15, 2021, in which university students recruited from 8 universities in the greater Stockholm area and Örebro were followed up at 5 time points over 1 year. The present study used data on 3525 students from 3 time points to assess whether procrastination was associated with worse health outcomes 9 months later.

Self-reported procrastination, measured using 5 items from the Swedish version of the Pure Procrastination Scale rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“very rarely or does not represent me”) to 5 (“very often or always represents me”) and summed to give a total procrastination score ranging from 5 to 25.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Sixteen self-reported health outcomes were assessed at the 9-month follow-up. These included mental health problems (symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress), disabling pain (neck and/or upper back, lower back, upper extremities, and lower extremities), unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality, physical inactivity, tobacco use, cannabis use, alcohol use, and breakfast skipping), psychosocial health factors (loneliness and economic difficulties), and general health.

The study included 3525 participants (2229 women [63%]; mean [SD] age, 24.8 [6.2] years), with a follow-up rate of 73% (n = 2587) 9 months later. The mean (SD) procrastination score at baseline was 12.9 (5.4). An increase of 1 SD in procrastination was associated with higher mean symptom levels of depression (β, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09-0.17), anxiety (β, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.04-0.12), and stress (β, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.08-0.15), and having disabling pain in the upper extremities (risk ratio [RR], 1.27; 95% CI, 1.14-1.42), poor sleep quality (RR, 1.09, 95% CI, 1.05-1.14), physical inactivity (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.11), loneliness (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12), and economic difficulties (RR, 1.15, 95% CI, 1.02-1.30) at the 9-month follow-up, after controlling for a large set of potential confounders.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study of Swedish university students suggests that procrastination is associated with subsequent mental health problems, disabling pain, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and worse psychosocial health factors. Considering that procrastination is prevalent among university students, these findings may be of importance to enhance the understanding of students’ health.

This cohort study evaluates the association between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes among university students in Sweden.

Introduction

Procrastination is defined as voluntarily delaying an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off because of the delay 1 and is common, especially among younger people. 2 , 3 It is estimated that at least half of university students engage in consistent and problematic procrastination, such as postponing studying for examinations or writing papers. 1 , 4 Procrastination is described as a form of self-regulatory failure linked to personality traits such as impulsiveness, 5 , 6 distractibility, and low conscientiousness. 1 , 7 An individual’s tendency to procrastinate is relatively stable over time, but specific procrastination behaviors are influenced by contextual factors such as task aversiveness. 1 For some students, procrastination is occasional and related to specific academic tasks, while for others it is more of a general disposition, potentially affecting academic achievements 8 and health.

Cross-sectional studies suggest that procrastination is associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress as well as loneliness and reduced life satisfaction. 2 , 9 , 10 , 11 Procrastination is also associated with prevalent general physical health problems, 12 cardiovascular disease, 13 and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. 12 , 14 , 15