MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

Preparing for AI-enabled cyberattacks

Artificial intelligence in the hands of cybercriminals poses an existential threat to organizations—IT security teams need “defensive AI” to fight back.

- MIT Technology Review Insights archive page

In association with Darktrace

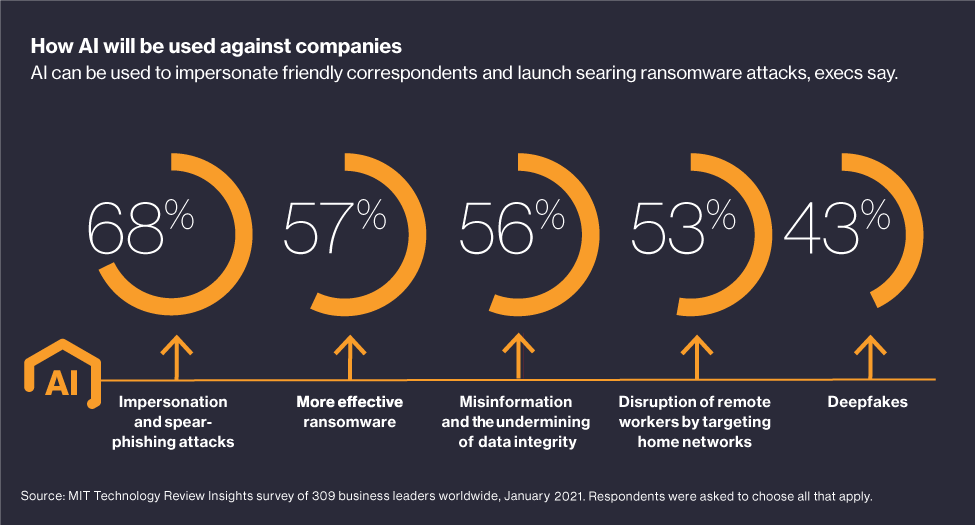

Cyberattacks continue to grow in prevalence and sophistication. With the ability to disrupt business operations, wipe out critical data, and cause reputational damage, they pose an existential threat to businesses, critical services, and infrastructure. Today’s new wave of attacks is outsmarting and outpacing humans, and even starting to incorporate artificial intelligence (AI). What’s known as “offensive AI” will enable cybercriminals to direct targeted attacks at unprecedented speed and scale while flying under the radar of traditional, rule-based detection tools.

Some of the world’s largest and most trusted organizations have already fallen victim to damaging cyberattacks, undermining their ability to safeguard critical data. With offensive AI on the horizon, organizations need to adopt new defenses to fight back: the battle of algorithms has begun.

Download the full report

MIT Technology Review Insights, in association with AI cybersecurity company Darktrace, surveyed more than 300 C-level executives, directors, and managers worldwide to understand how they’re addressing the cyberthreats they’re up against—and how to use AI to help fight against them.

As it is, 60% of respondents report that human-driven responses to cyberattacks are failing to keep up with automated attacks, and as organizations gear up for a greater challenge, more sophisticated technologies are critical. In fact, an overwhelming majority of respondents—96%—report they’ve already begun to guard against AI-powered attacks, with some enabling AI defenses.

Offensive AI cyberattacks are daunting, and the technology is fast and smart. Consider deepfakes, one type of weaponized AI tool, which are fabricated images or videos depicting scenes or people that were never present, or even existed.

In January 2020, the FBI warned that deepfake technology had already reached the point where artificial personas could be created that could pass biometric tests. At the rate that AI neural networks are evolving, an FBI official said at the time, national security could be undermined by high-definition, fake videos created to mimic public figures so that they appear to be saying whatever words the video creators put in their manipulated mouths.

This is just one example of the technology being used for nefarious purposes. AI could, at some point, conduct cyberattacks autonomously, disguising their operations and blending in with regular activity. The technology is out there for anyone to use, including threat actors.

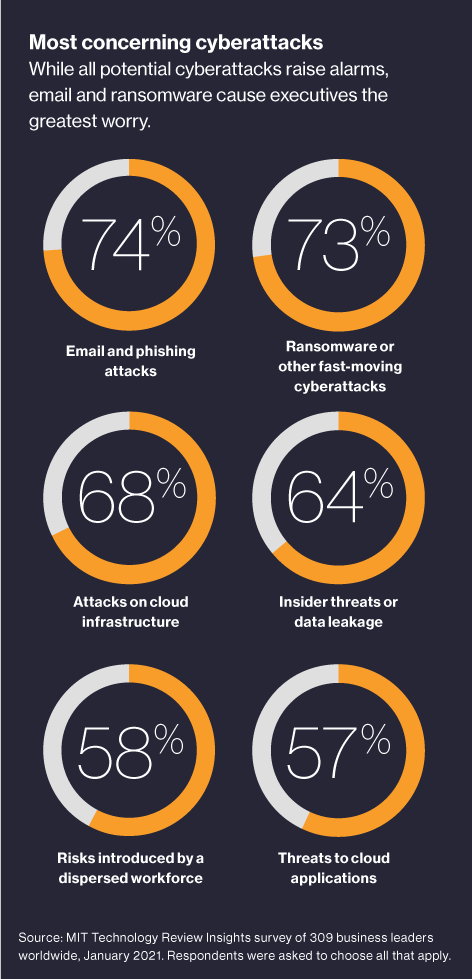

Offensive AI risks and developments in the cyberthreat landscape are redefining enterprise security, as humans already struggle to keep pace with advanced attacks. In particular, survey respondents reported that email and phishing attacks cause them the most angst, with nearly three quarters reporting that email threats are the most worrisome. That breaks down to 40% of respondents who report finding email and phishing attacks “very concerning,” while 34% call them “somewhat concerning.” It’s not surprising, as 94% of detected malware is still delivered by email. The traditional methods of stopping email-delivered threats rely on historical indicators—namely, previously seen attacks—as well as the ability of the recipient to spot the signs, both of which can be bypassed by sophisticated phishing incursions.

When offensive AI is thrown into the mix, “fake email” will be almost indistinguishable from genuine communications from trusted contacts.

How attackers exploit the headlines

The coronavirus pandemic presented a lucrative opportunity for cybercriminals. Email attackers in particular followed a long-established pattern: take advantage of the headlines of the day—along with the fear, uncertainty, greed, and curiosity they incite—to lure victims in what has become known as “fearware” attacks. With employees working remotely, without the security protocols of the office in place, organizations saw successful phishing attempts skyrocket. Max Heinemeyer, director of threat hunting for Darktrace, notes that when the pandemic hit, his team saw an immediate evolution of phishing emails. “We saw a lot of emails saying things like, ‘Click here to see which people in your area are infected,’” he says. When offices and universities started reopening last year, new scams emerged in lockstep, with emails offering “cheap or free covid-19 cleaning programs and tests,” says Heinemeyer.

There has also been an increase in ransomware, which has coincided with the surge in remote and hybrid work environments. “The bad guys know that now that everybody relies on remote work. If you get hit now, and you can’t provide remote access to your employee anymore, it’s game over,” he says. “Whereas maybe a year ago, people could still come into work, could work offline more, but it hurts much more now. And we see that the criminals have started to exploit that.”

What’s the common theme? Change, rapid change, and—in the case of the global shift to working from home—complexity. And that illustrates the problem with traditional cybersecurity, which relies on traditional, signature-based approaches: static defenses aren’t very good at adapting to change. Those approaches extrapolate from yesterday’s attacks to determine what tomorrow’s will look like. “How could you anticipate tomorrow’s phishing wave? It just doesn’t work,” Heinemeyer says.

Download the full report .

It’s time to retire the term “user”

The proliferation of AI means we need a new word.

- Taylor Majewski archive page

Modernizing data with strategic purpose

Data strategies and modernization initiatives misaligned with the overall business strategy—or too narrowly focused on AI—leave substantial business value on the table.

How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

MIT Technology Review sat down with outgoing CTO Martin van den Brink to talk about the company’s rise to dominance and the life and death of Moore’s Law.

- Mat Honan archive page

- James O'Donnell archive page

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

- Zeyi Yang archive page

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

Doha Declaration

Education for justice.

- Agenda Day 1

- Agenda Day 2

- Agenda Day 3

- Agenda Day 4

- Registration

- Breakout Sessions for Primary and Secondary Level

- Breakout Sessions for Tertiary Level

- E4J Youth Competition

- India - Lockdown Learners

- Chuka, Break the Silence

- The Online Zoo

- I would like a community where ...

- Staying safe online

- Let's be respectful online

- We can all be heroes

- Respect for all

- We all have rights

- A mosaic of differences

- The right thing to do

- Solving ethical dilemmas

- UNODC-UNESCO Guide for Policymakers

- UNODC-UNESCO Handbooks for Teachers

- Justice Accelerators

Introduction

- Organized Crime

- Trafficking in Persons & Smuggling of Migrants

- Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice Reform

- Crime Prevention, Criminal Justice & SDGs

- UN Congress on Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice

- Commission on Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice

- Conference of the Parties to UNTOC

- Conference of the States Parties to UNCAC

- Rules for Simulating Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice Bodies

- Crime Prevention & Criminal Justice

- Engage with Us

- Contact Us about MUN

- Conferences Supporting E4J

- Cyberstrike

- Play for Integrity

- Running out of Time

- Zorbs Reloaded

- Developing a Rationale for Using the Video

- Previewing the Anti-Corruption Video

- Viewing the Video with a Purpose

- Post-viewing Activities

- Previewing the Firearms Video

- Rationale for Using the Video

- Previewing the Human Trafficking Video

- Previewing the Organized Crime Video

- Previewing the Video

- Criminal Justice & Crime Prevention

- Corruption & Integrity

- Human Trafficking & Migrant Smuggling

- Firearms Trafficking

- Terrorism & Violent Extremism

- Introduction & Learning Outcomes

- Corruption - Baseline Definition

- Effects of Corruption

- Deeper Meanings of Corruption

- Measuring Corruption

- Possible Class Structure

- Core Reading

- Advanced Reading

- Student Assessment

- Additional Teaching Tools

- Guidelines for Stand-Alone Course

- Appendix: How Corruption Affects the SDGs

- What is Governance?

- What is Good Governance?

- Corruption and Bad Governance

- Governance Reforms and Anti-Corruption

- Guidelines for Stand-alone Course

- Corruption and Democracy

- Corruption and Authoritarian Systems

- Hybrid Systems and Syndromes of Corruption

- The Deep Democratization Approach

- Political Parties and Political Finance

- Political Institution-building as a Means to Counter Corruption

- Manifestations and Consequences of Public Sector Corruption

- Causes of Public Sector Corruption

- Theories that Explain Corruption

- Corruption in Public Procurement

- Corruption in State-Owned Enterprises

- Responses to Public Sector Corruption

- Preventing Public Sector Corruption

- Forms & Manifestations of Private Sector Corruption

- Consequences of Private Sector Corruption

- Causes of Private Sector Corruption

- Responses to Private Sector Corruption

- Preventing Private Sector Corruption

- Collective Action & Public-Private Partnerships against Corruption

- Transparency as a Precondition

- Detection Mechanisms - Auditing and Reporting

- Whistle-blowing Systems and Protections

- Investigation of Corruption

- Introduction and Learning Outcomes

- Brief background on the human rights system

- Overview of the corruption-human rights nexus

- Impact of corruption on specific human rights

- Approaches to assessing the corruption-human rights nexus

- Human-rights based approach

- Defining sex, gender and gender mainstreaming

- Gender differences in corruption

- Theories explaining the gender–corruption nexus

- Gendered impacts of corruption

- Anti-corruption and gender mainstreaming

- Manifestations of corruption in education

- Costs of corruption in education

- Causes of corruption in education

- Fighting corruption in education

- Core terms and concepts

- The role of citizens in fighting corruption

- The role, risks and challenges of CSOs fighting corruption

- The role of the media in fighting corruption

- Access to information: a condition for citizen participation

- ICT as a tool for citizen participation in anti-corruption efforts

- Government obligations to ensure citizen participation in anti-corruption efforts

- Teaching Guide

- Brief History of Terrorism

- 19th Century Terrorism

- League of Nations & Terrorism

- United Nations & Terrorism

- Terrorist Victimization

- Exercises & Case Studies

- Radicalization & Violent Extremism

- Preventing & Countering Violent Extremism

- Drivers of Violent Extremism

- International Approaches to PVE &CVE

- Regional & Multilateral Approaches

- Defining Rule of Law

- UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy

- International Cooperation & UN CT Strategy

- Legal Sources & UN CT Strategy

- Regional & National Approaches

- International Legal Frameworks

- International Human Rights Law

- International Humanitarian Law

- International Refugee Law

- Current Challenges to International Legal Framework

- Defining Terrorism

- Criminal Justice Responses

- Treaty-based Crimes of Terrorism

- Core International Crimes

- International Courts and Tribunals

- African Region

- Inter-American Region

- Asian Region

- European Region

- Middle East & Gulf Regions

- Core Principles of IHL

- Categorization of Armed Conflict

- Classification of Persons

- IHL, Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism

- Relationship between IHL & intern. human rights law

- Limitations Permitted by Human Rights Law

- Derogation during Public Emergency

- Examples of States of Emergency & Derogations

- International Human Rights Instruments

- Regional Human Rights Instruments

- Extra-territorial Application of Right to Life

- Arbitrary Deprivation of Life

- Death Penalty

- Enforced Disappearances

- Armed Conflict Context

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- Convention against Torture et al.

- International Legal Framework

- Key Contemporary Issues

- Investigative Phase

- Trial & Sentencing Phase

- Armed Conflict

- Case Studies

- Special Investigative Techniques

- Surveillance & Interception of Communications

- Privacy & Intelligence Gathering in Armed Conflict

- Accountability & Oversight of Intelligence Gathering

- Principle of Non-Discrimination

- Freedom of Religion

- Freedom of Expression

- Freedom of Assembly

- Freedom of Association

- Fundamental Freedoms

- Definition of 'Victim'

- Effects of Terrorism

- Access to Justice

- Recognition of the Victim

- Human Rights Instruments

- Criminal Justice Mechanisms

- Instruments for Victims of Terrorism

- National Approaches

- Key Challenges in Securing Reparation

- Topic 1. Contemporary issues relating to conditions conducive both to the spread of terrorism and the rule of law

- Topic 2. Contemporary issues relating to the right to life

- Topic 3. Contemporary issues relating to foreign terrorist fighters

- Topic 4. Contemporary issues relating to non-discrimination and fundamental freedoms

- Module 16: Linkages between Organized Crime and Terrorism

- Thematic Areas

- Content Breakdown

- Module Adaptation & Design Guidelines

- Teaching Methods

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introducing United Nations Standards & Norms on CPCJ vis-à-vis International Law

- 2. Scope of United Nations Standards & Norms on CPCJ

- 3. United Nations Standards & Norms on CPCJ in Operation

- 1. Definition of Crime Prevention

- 2. Key Crime Prevention Typologies

- 2. (cont.) Tonry & Farrington’s Typology

- 3. Crime Problem-Solving Approaches

- 4. What Works

- United Nations Entities

- Regional Crime Prevention Councils/Institutions

- Key Clearinghouses

- Systematic Reviews

- 1. Introduction to International Standards & Norms

- 2. Identifying the Need for Legal Aid

- 3. Key Components of the Right of Access to Legal Aid

- 4. Access to Legal Aid for Those with Specific Needs

- 5. Models for Governing, Administering and Funding Legal Aid

- 6. Models for Delivering Legal Aid Services

- 7. Roles and Responsibilities of Legal Aid Providers

- 8. Quality Assurance and Legal Aid Services

- 1. Context for Use of Force by Law Enforcement Officials

- 2. Legal Framework

- 3. General Principles of Use of Force in Law Enforcement

- 4. Use of Firearms

- 5. Use of “Less-Lethal” Weapons

- 6. Protection of Especially Vulnerable Groups

- 7. Use of Force during Assemblies

- 1. Policing in democracies & need for accountability, integrity, oversight

- 2. Key mechanisms & actors in police accountability, oversight

- 3. Crosscutting & contemporary issues in police accountability

- 1. Introducing Aims of Punishment, Imprisonment & Prison Reform

- 2. Current Trends, Challenges & Human Rights

- 3. Towards Humane Prisons & Alternative Sanctions

- 1. Aims and Significance of Alternatives to Imprisonment

- 2. Justifying Punishment in the Community

- 3. Pretrial Alternatives

- 4. Post Trial Alternatives

- 5. Evaluating Alternatives

- 1. Concept, Values and Origin of Restorative Justice

- 2. Overview of Restorative Justice Processes

- 3. How Cost Effective is Restorative Justice?

- 4. Issues in Implementing Restorative Justice

- 1. Gender-Based Discrimination & Women in Conflict with the Law

- 2. Vulnerabilities of Girls in Conflict with the Law

- 3. Discrimination and Violence against LGBTI Individuals

- 4. Gender Diversity in Criminal Justice Workforce

- 1. Ending Violence against Women

- 2. Human Rights Approaches to Violence against Women

- 3. Who Has Rights in this Situation?

- 4. What about the Men?

- 5. Local, Regional & Global Solutions to Violence against Women & Girls

- 1. Understanding the Concept of Victims of Crime

- 2. Impact of Crime, including Trauma

- 3. Right of Victims to Adequate Response to their Needs

- 4. Collecting Victim Data

- 5. Victims and their Participation in Criminal Justice Process

- 6. Victim Services: Institutional and Non-Governmental Organizations

- 7. Outlook on Current Developments Regarding Victims

- 8. Victims of Crime and International Law

- 1. The Many Forms of Violence against Children

- 2. The Impact of Violence on Children

- 3. States' Obligations to Prevent VAC and Protect Child Victims

- 4. Improving the Prevention of Violence against Children

- 5. Improving the Criminal Justice Response to VAC

- 6. Addressing Violence against Children within the Justice System

- 1. The Role of the Justice System

- 2. Convention on the Rights of the Child & International Legal Framework on Children's Rights

- 3. Justice for Children

- 4. Justice for Children in Conflict with the Law

- 5. Realizing Justice for Children

- 1a. Judicial Independence as Fundamental Value of Rule of Law & of Constitutionalism

- 1b. Main Factors Aimed at Securing Judicial Independence

- 2a. Public Prosecutors as ‘Gate Keepers’ of Criminal Justice

- 2b. Institutional and Functional Role of Prosecutors

- 2c. Other Factors Affecting the Role of Prosecutors

- Basics of Computing

- Global Connectivity and Technology Usage Trends

- Cybercrime in Brief

- Cybercrime Trends

- Cybercrime Prevention

- Offences against computer data and systems

- Computer-related offences

- Content-related offences

- The Role of Cybercrime Law

- Harmonization of Laws

- International and Regional Instruments

- International Human Rights and Cybercrime Law

- Digital Evidence

- Digital Forensics

- Standards and Best Practices for Digital Forensics

- Reporting Cybercrime

- Who Conducts Cybercrime Investigations?

- Obstacles to Cybercrime Investigations

- Knowledge Management

- Legal and Ethical Obligations

- Handling of Digital Evidence

- Digital Evidence Admissibility

- Sovereignty and Jurisdiction

- Formal International Cooperation Mechanisms

- Informal International Cooperation Mechanisms

- Data Retention, Preservation and Access

- Challenges Relating to Extraterritorial Evidence

- National Capacity and International Cooperation

- Internet Governance

- Cybersecurity Strategies: Basic Features

- National Cybersecurity Strategies

- International Cooperation on Cybersecurity Matters

- Cybersecurity Posture

- Assets, Vulnerabilities and Threats

- Vulnerability Disclosure

- Cybersecurity Measures and Usability

- Situational Crime Prevention

- Incident Detection, Response, Recovery & Preparedness

- Privacy: What it is and Why it is Important

- Privacy and Security

- Cybercrime that Compromises Privacy

- Data Protection Legislation

- Data Breach Notification Laws

- Enforcement of Privacy and Data Protection Laws

- Intellectual Property: What it is

- Types of Intellectual Property

- Causes for Cyber-Enabled Copyright & Trademark Offences

- Protection & Prevention Efforts

- Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

- Cyberstalking and Cyberharassment

- Cyberbullying

- Gender-Based Interpersonal Cybercrime

- Interpersonal Cybercrime Prevention

- Cyber Organized Crime: What is it?

- Conceptualizing Organized Crime & Defining Actors Involved

- Criminal Groups Engaging in Cyber Organized Crime

- Cyber Organized Crime Activities

- Preventing & Countering Cyber Organized Crime

- Cyberespionage

- Cyberterrorism

- Cyberwarfare

- Information Warfare, Disinformation & Electoral Fraud

- Responses to Cyberinterventions

- Framing the Issue of Firearms

- Direct Impact of Firearms

- Indirect Impacts of Firearms on States or Communities

- International and National Responses

- Typology and Classification of Firearms

- Common Firearms Types

- 'Other' Types of Firearms

- Parts and Components

- History of the Legitimate Arms Market

- Need for a Legitimate Market

- Key Actors in the Legitimate Market

- Authorized & Unauthorized Arms Transfers

- Illegal Firearms in Social, Cultural & Political Context

- Supply, Demand & Criminal Motivations

- Larger Scale Firearms Trafficking Activities

- Smaller Scale Trafficking Activities

- Sources of Illicit Firearms

- Consequences of Illicit Markets

- International Public Law & Transnational Law

- International Instruments with Global Outreach

- Commonalities, Differences & Complementarity between Global Instruments

- Tools to Support Implementation of Global Instruments

- Other United Nations Processes

- The Sustainable Development Goals

- Multilateral & Regional Instruments

- Scope of National Firearms Regulations

- National Firearms Strategies & Action Plans

- Harmonization of National Legislation with International Firearms Instruments

- Assistance for Development of National Firearms Legislation

- Firearms Trafficking as a Cross-Cutting Element

- Organized Crime and Organized Criminal Groups

- Criminal Gangs

- Terrorist Groups

- Interconnections between Organized Criminal Groups & Terrorist Groups

- Gangs - Organized Crime & Terrorism: An Evolving Continuum

- International Response

- International and National Legal Framework

- Firearms Related Offences

- Role of Law Enforcement

- Firearms as Evidence

- Use of Special Investigative Techniques

- International Cooperation and Information Exchange

- Prosecution and Adjudication of Firearms Trafficking

- Teaching Methods & Principles

- Ethical Learning Environments

- Overview of Modules

- Module Adaption & Design Guidelines

- Table of Exercises

- Basic Terms

- Forms of Gender Discrimination

- Ethics of Care

- Case Studies for Professional Ethics

- Case Studies for Role Morality

- Additional Exercises

- Defining Organized Crime

- Definition in Convention

- Similarities & Differences

- Activities, Organization, Composition

- Thinking Critically Through Fiction

- Excerpts of Legislation

- Research & Independent Study Questions

- Legal Definitions of Organized Crimes

- Criminal Association

- Definitions in the Organized Crime Convention

- Criminal Organizations and Enterprise Laws

- Enabling Offence: Obstruction of Justice

- Drug Trafficking

- Wildlife & Forest Crime

- Counterfeit Products Trafficking

- Falsified Medical Products

- Trafficking in Cultural Property

- Trafficking in Persons

- Case Studies & Exercises

- Extortion Racketeering

- Loansharking

- Links to Corruption

- Bribery versus Extortion

- Money-Laundering

- Liability of Legal Persons

- How much Organized Crime is there?

- Alternative Ways for Measuring

- Measuring Product Markets

- Risk Assessment

- Key Concepts of Risk Assessment

- Risk Assessment of Organized Crime Groups

- Risk Assessment of Product Markets

- Risk Assessment in Practice

- Positivism: Environmental Influences

- Classical: Pain-Pleasure Decisions

- Structural Factors

- Ethical Perspective

- Crime Causes & Facilitating Factors

- Models and Structure

- Hierarchical Model

- Local, Cultural Model

- Enterprise or Business Model

- Groups vs Activities

- Networked Structure

- Jurisdiction

- Investigators of Organized Crime

- Controlled Deliveries

- Physical & Electronic Surveillance

- Undercover Operations

- Financial Analysis

- Use of Informants

- Rights of Victims & Witnesses

- Role of Prosecutors

- Adversarial vs Inquisitorial Legal Systems

- Mitigating Punishment

- Granting Immunity from Prosecution

- Witness Protection

- Aggravating & Mitigating Factors

- Sentencing Options

- Alternatives to Imprisonment

- Death Penalty & Organized Crime

- Backgrounds of Convicted Offenders

- Confiscation

- Confiscation in Practice

- Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA)

- Extradition

- Transfer of Criminal Proceedings

- Transfer of Sentenced Persons

- Module 12: Prevention of Organized Crime

- Adoption of Organized Crime Convention

- Historical Context

- Features of the Convention

- Related international instruments

- Conference of the Parties

- Roles of Participants

- Structure and Flow

- Recommended Topics

- Background Materials

- What is Sex / Gender / Intersectionality?

- Knowledge about Gender in Organized Crime

- Gender and Organized Crime

- Gender and Different Types of Organized Crime

- Definitions and Terminology

- Organized crime and Terrorism - International Legal Framework

- International Terrorism-related Conventions

- UNSC Resolutions on Terrorism

- Organized Crime Convention and its Protocols

- Theoretical Frameworks on Linkages between Organized Crime and Terrorism

- Typologies of Criminal Behaviour Associated with Terrorism

- Terrorism and Drug Trafficking

- Terrorism and Trafficking in Weapons

- Terrorism, Crime and Trafficking in Cultural Property

- Trafficking in Persons and Terrorism

- Intellectual Property Crime and Terrorism

- Kidnapping for Ransom and Terrorism

- Exploitation of Natural Resources and Terrorism

- Review and Assessment Questions

- Research and Independent Study Questions

- Criminalization of Smuggling of Migrants

- UNTOC & the Protocol against Smuggling of Migrants

- Offences under the Protocol

- Financial & Other Material Benefits

- Aggravating Circumstances

- Criminal Liability

- Non-Criminalization of Smuggled Migrants

- Scope of the Protocol

- Humanitarian Exemption

- Migrant Smuggling v. Irregular Migration

- Migrant Smuggling vis-a-vis Other Crime Types

- Other Resources

- Assistance and Protection in the Protocol

- International Human Rights and Refugee Law

- Vulnerable groups

- Positive and Negative Obligations of the State

- Identification of Smuggled Migrants

- Participation in Legal Proceedings

- Role of Non-Governmental Organizations

- Smuggled Migrants & Other Categories of Migrants

- Short-, Mid- and Long-Term Measures

- Criminal Justice Reponse: Scope

- Investigative & Prosecutorial Approaches

- Different Relevant Actors & Their Roles

- Testimonial Evidence

- Financial Investigations

- Non-Governmental Organizations

- ‘Outside the Box’ Methodologies

- Intra- and Inter-Agency Coordination

- Admissibility of Evidence

- International Cooperation

- Exchange of Information

- Non-Criminal Law Relevant to Smuggling of Migrants

- Administrative Approach

- Complementary Activities & Role of Non-criminal Justice Actors

- Macro-Perspective in Addressing Smuggling of Migrants

- Human Security

- International Aid and Cooperation

- Migration & Migrant Smuggling

- Mixed Migration Flows

- Social Politics of Migrant Smuggling

- Vulnerability

- Profile of Smugglers

- Role of Organized Criminal Groups

- Humanitarianism, Security and Migrant Smuggling

- Crime of Trafficking in Persons

- The Issue of Consent

- The Purpose of Exploitation

- The abuse of a position of vulnerability

- Indicators of Trafficking in Persons

- Distinction between Trafficking in Persons and Other Crimes

- Misconceptions Regarding Trafficking in Persons

- Root Causes

- Supply Side Prevention Strategies

- Demand Side Prevention Strategies

- Role of the Media

- Safe Migration Channels

- Crime Prevention Strategies

- Monitoring, Evaluating & Reporting on Effectiveness of Prevention

- Trafficked Persons as Victims

- Protection under the Protocol against Trafficking in Persons

- Broader International Framework

- State Responsibility for Trafficking in Persons

- Identification of Victims

- Principle of Non-Criminalization of Victims

- Criminal Justice Duties Imposed on States

- Role of the Criminal Justice System

- Current Low Levels of Prosecutions and Convictions

- Challenges to an Effective Criminal Justice Response

- Rights of Victims to Justice and Protection

- Potential Strategies to “Turn the Tide”

- State Cooperation with Civil Society

- Civil Society Actors

- The Private Sector

- Comparing SOM and TIP

- Differences and Commonalities

- Vulnerability and Continuum between SOM & TIP

- Labour Exploitation

- Forced Marriage

- Other Examples

- Children on the Move

- Protecting Smuggled and Trafficked Children

- Protection in Practice

- Children Alleged as Having Committed Smuggling or Trafficking Offences

- Basic Terms - Gender and Gender Stereotypes

- International Legal Frameworks and Definitions of TIP and SOM

- Global Overview on TIP and SOM

- Gender and Migration

- Key Debates in the Scholarship on TIP and SOM

- Gender and TIP and SOM Offenders

- Responses to TIP and SOM

- Use of Technology to Facilitate TIP and SOM

- Technology Facilitating Trafficking in Persons

- Technology in Smuggling of Migrants

- Using Technology to Prevent and Combat TIP and SOM

- Privacy and Data Concerns

- Emerging Trends

- Demand and Consumption

- Supply and Demand

- Implications of Wildlife Trafficking

- Legal and Illegal Markets

- Perpetrators and their Networks

- Locations and Activities relating to Wildlife Trafficking

- Environmental Protection & Conservation

- CITES & the International Trade in Endangered Species

- Organized Crime & Corruption

- Animal Welfare

- Criminal Justice Actors and Agencies

- Criminalization of Wildlife Trafficking

- Challenges for Law Enforcement

- Investigation Measures and Detection Methods

- Prosecution and Judiciary

- Wild Flora as the Target of Illegal Trafficking

- Purposes for which Wild Flora is Illegally Targeted

- How is it Done and Who is Involved?

- Consequences of Harms to Wild Flora

- Terminology

- Background: Communities and conservation: A history of disenfranchisement

- Incentives for communities to get involved in illegal wildlife trafficking: the cost of conservation

- Incentives to participate in illegal wildlife, logging and fishing economies

- International and regional responses that fight wildlife trafficking while supporting IPLCs

- Mechanisms for incentivizing community conservation and reducing wildlife trafficking

- Critiques of community engagement

- Other challenges posed by wildlife trafficking that affect local populations

- Global Podcast Series

- Apr. 2021: Call for Expressions of Interest: Online training for academics from francophone Africa

- Feb. 2021: Series of Seminars for Universities of Central Asia

- Dec. 2020: UNODC and TISS Conference on Access to Justice to End Violence

- Nov. 2020: Expert Workshop for University Lecturers and Trainers from the Commonwealth of Independent States

- Oct. 2020: E4J Webinar Series: Youth Empowerment through Education for Justice

- Interview: How to use E4J's tool in teaching on TIP and SOM

- E4J-Open University Online Training-of-Trainers Course

- Teaching Integrity and Ethics Modules: Survey Results

- Grants Programmes

- E4J MUN Resource Guide

- Library of Resources

Module 1: Introduction to Cybercrime

- {{item.name}} ({{item.items.length}}) items

- Add new list

E4J University Module Series: Cybercrime

Introduction and learning outcomes.

- Basics of computing

- Global connectivity and technology usage trends

- Cybercrime in brief

- Cybercrime trends

- Cybercrime prevention

Possible class structure

Core reading, advanced reading, student assessment, additional teaching tools.

- First published in May 2019, updated in February 2020

This module is a resource for lecturers

Information and communication technology (ICT) has transformed the way in which individuals conduct business, purchase goods and services, send and receive money, communicate, share information, interact with people, and form and cultivate relationships with others. This transformation, as well as the world's ever-increasing use of and dependency on ICT, creates vulnerabilities to criminals and other malicious actors targeting ICT and/or using ICT to commit crime.

This Module provides an introduction to key concepts relating to cybercrime, what cybercrime is, Internet, technology and cybercrime trends, and the technical, legal, ethical, and operational challenges related to cybercrime and cybercrime prevention. The reading material selected for this Module provides an overview of key concepts, basic terms, and definitions, and a general introduction to cybercrime, its challenges, and prevention.

Learning outcomes

- Define and describe basic concepts relating to computing

- Describe and assess global connectivity and technology usage trends

- Define cybercrime and discuss why cybercrime is scientifically studied

- Discuss and analyse cybercrime trends

- Identify, examine, and analyse the technical, legal, ethical, and operational challenges relating to the investigation and prevention of cybercrime

Next: Key issues

Back to top, supported by the state of qatar, 60 years crime congress.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

33 Cybercrime and You: How Criminals Attack and the Human Factors That They Seek to Exploit

Jason R. C. Nurse, School of Computing, University of Kent, UK

- Published: 09 October 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Cybercrime is a significant challenge to society, but it can be particularly harmful to the individuals who become victims. This chapter engages in a comprehensive and topical analysis of the cybercrimes that target individuals. It also examines the motivation of criminals that perpetrate such attacks and the key human factors and psychological aspects that help to make cybercriminals successful. Key areas assessed include social engineering (e.g., phishing, romance scams, catfishing), online harassment (e.g., cyberbullying, trolling, revenge porn, hate crimes), identity-related crimes (e.g., identity theft, doxing), hacking (e.g., malware, cryptojacking, account hacking), and denial-of-service crimes. As a part of its contribution, the chapter introduces a summary taxonomy of cybercrimes against individuals and a case for why they will continue to occur if concerted interdisciplinary efforts are not pursued.

Introduction

The internet and its significance to us as individuals.

Technology drives modern day society. It has influenced everything from governments and market economies, to global trade, travel, and communications. Digital technologies have further revolutionized our world, and since the advent of the Internet and the World Wide Web, society has become more efficient and advanced (Graham & Dutton, 2014 ). There are many benefits of the online world and to such large scales of connectivity. For individual Internet users, instantaneous communication translates into a platform for online purchases (on sites such as Amazon and eBay), online banking and financial management, interaction with friends and family members using messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp and LINE), and the sharing of information (personal, opinion, or fact) on websites, blogs, and wikis. As the world has progressed technologically, these and many other services (such as Netflix, Uber, and Google services) have been made available to individuals with the aim of streamlining every aspect of our lives.

In a 2017 study of 30 economies including the United Kingdom (UK), United States of America (US), and Australia, it was the citizens of the Philippines that spent the most time online—at eight hours fifty-nine minutes, on average, per day—across PC and mobile devices (We Are Social, 2017 ). Brazil was second with eight hours fifty-five minutes, followed by Thailand at eight hours forty-nine minutes online. Developed countries such as the US, UK, and Australia posted usage values of between six hours twenty-one minutes and five hours eighteen minutes. This highlights a substantial usage gap compared to some developing states. A key driver of this increased Internet usage is social media, and particularly individuals’ use of platforms such as Facebook, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, YouTube, and instant messaging service QQ (We Are Social, 2017 ). Evidence supporting this reality has also been found in other studies, where social networks are more frequently used by Internet users in the emerging world (Poushter, 2016 ); this type of use is key to understanding the impact of social media in online crime, as will be outlined further later in this chapter.

The Prevalence of Cybercrime

To critically reflect on today’s world, while the Internet has various positive uses, it is increasingly being used as a tool to facilitate possibly the most significant challenge facing individuals’ use of the Internet: cybercrime. Cybercrime has been defined in several ways but can essentially be regarded as any crime (traditional or new) that can be conducted or enabled through, or using, digital technologies. Such technologies include personal computers (PCs), laptops, mobile phones, and smart devices (e.g., Internet-connected cameras, voice assistants), but the scope is quickly expanding to encompass smart systems and infrastructures (e.g., homes, offices, and buildings driven by the Internet of Things or IoT).

The importance of cybercrime can be seen in its ever-rising prevalence. In the UK, for example, a key finding of an early Crime Survey of England and Wales by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) was that there were 3.8 million reported instances of cybercrime in the twelve months to June 2016 (Scott, 2016 ). This is generally noteworthy, but even more so, given that the total number of crimes recorded in the other components of the survey (e.g., burglary, theft, violent crimes, but excluding fraud) tallied 6.5 million. The number of cybercrimes, therefore, amounts to more than half of the total crimes. Similar trends can also be found in the 2018 ONS report, with cybercrime and fraud accounting for almost half of crimes (techUK, 2018 ). This reality becomes more concerning given that these statistics are only based on the reported crimes, and moreover, that such cybercrimes are almost certainly set to increase in the future. Studies from the US also further evidence the extent of cybercrime and identity theft. Research from the 2018 Identity Fraud Study found that $16.8 billion was stolen from 16.7 million US consumers in 2017, which represents an 8% increase in the number of victims from a year earlier (Weber, 2018 ).

Types of Cybercrime

At its core, there are arguably three types of cybercrime: crimes in the device, crimes using the device, and crimes against the device (Wall, 2007 ). Crimes in the device relates to situations in which the content on the device may be illegal or otherwise prohibited. Examples include trading and distribution of content that promotes hate crimes or incites violence. The next category, crimes using the device, encompasses crimes where digital systems are used to engage and often, to deceive, victims. An example of this is a criminal pretending to be a legitimate person (or entity) and tricking an individual into releasing their personal details (e.g., account credentials) or transferring funds to other accounts. Wall’s final category, crimes against the device, pertains to incidents that compromise the device or system in some way. These crimes directly target the fundamental principles of cybersecurity, i.e., the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (regularly referred to as the CIA triad) of systems and data. This typology provides some general insight into the many crimes prevalent online today.

This chapter aims to build on the introduction to cybercrime and security issues online and focus in detail on cybercrimes conducted against individuals. It focuses on many of the crimes being conducted today and offers a topical discourse on how criminals craft these attacks, their motivations, and the key human factors and psychological aspects that make cybercriminals successful. Areas covered include social engineering (e.g., phishing, romance scams, catfishing), online harassment (e.g., cyberbullying, trolling, revenge porn, 1 and hate crimes), identity-related crimes (e.g., identity theft and doxxing), hacking (e.g., malware and account hacking), and denial-of-service (DoS) crimes.

Cybercrimes against Individuals: A Focus on the Core Crimes

The cybercrime landscape is enormous, and so are the varieties of ways in which cybercriminals can seek to attack individuals. This section introduces a taxonomy summarizing the most significant types of online crimes against individuals. These types of cybercrime are defined based on a comprehensive and systematic review of online crimes, case studies, and articles in academic, industry, and government circles. This includes instances and cases of cybercrime across the world (e.g., BBC News, 2016b ; Sidek & Rubbi-Clarke, 2017 ), taxonomies of cybercrime and cyberattacks that have been developed in research (e.g., Gordon & Ford, 2006 ; Wall, 2007 ; Wall, 2005/2015 ), industry reports on prevalent crimes (e.g., CheckPoint, 2017 ; PwC, 2016 ), and governmental publications in the space (e.g., NCA, 2017 ).

The intention is to connect the identified types of cybercrime to real-world situations, but also to maintain a flexible structure as new types of cybercrimes may well emerge. Moreover, the chapter is inclusive in its approach and defines types that are relatable and easily communicated—which has benefits for engagement, especially for those not involved in cybersecurity nor with a technical background or expertise. It is important to note here that many of the types identified here can be seen across prior works. For example, Wall’s work ( 2005/2015 ) examines crimes against the individual, crimes against the machine, and crimes in the machine, and Gordon and Ford ( 2006 ) use some of these types as exemplars of their Type 1 and Type 2 cybercrimes. This taxonomy’s value is therefore not in identifying new types of cybercrime, but instead in providing a new perspective on the topic which centers in on the types of cybercrime most prevalent today. The taxonomy is presented in Figure 1 .

Main types of cybercrimes against individuals.

The first type of cybercrime is Social Engineering and Trickery , which involves applying deceitful methods to coerce individuals into behaving certain ways or performing some task. Next, Online Harassment is similar to its offline counterpart and describes instances where persons online are annoyed/abused and tormented by others. Identity-related crimes are those in which an individual’s identity is stolen or misused by others for a nefarious or illegitimate purpose (e.g., fraud). Hacking , one of the most well publicized cybercrimes both in the news and the entertainment industry (e.g., Mr. Robot , Live Free or Die Hard , The Matrix , Swordfish ), is the action of compromising computing systems. While traditionally not regarded as a significant personal crime, Denial of Service is one of the most used by online criminals, and its popularity is attributed to its simplicity—i.e., it primarily involves blocking legitimate access to information, files, websites, or services—and effectiveness. Finally, (Denial of) Information accommodates the new trend of ransomware which is similar in that it denies individuals access to their own information. The next sections analyze the taxonomy and each of its types of crimes in detail.

Social Engineering and Online Trickery

Trickery, deceit, and scams are examples of some of the oldest means used by adversaries to achieve their goals. In Greek mythology, their army used deceit in the form of a Trojan horse; presented to the Trojans as a gift (or more specifically, an offering to Athena, goddess of war), it was instead a means for the Greek army to enter and destroy the city of Troy. Additionally, in The Art of War , fifth-century bce Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu declares, “Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near” (Tzu/Giles, 2009 ). According to this well-known text on war, the intention is to deceive and, ideally, to misdirect, while discretely progressing towards and obtaining the goal—in Tzu’s case, winning against the enemy in battle.

Cybercriminals, potentially informed by history itself, have been applying such techniques for decades in Social Engineering , i.e., a specific class of cybercrime that uses deception or trickery to manipulate individuals into performing some unauthorized or illegitimate task. It seeks to exploit human psychology and is possibly the most effective means of conducting a crime against an individual.

In one example, a social engineer breaks into an individual’s cell-phone provider account in under two minutes. 2 This was achieved by phoning the cell-phone provider’s help desk, pretending to be the customer’s wife (impersonation is typically a core component of this crime), and using an audio recording of a crying baby (under the guise of it being her baby) to elicit sympathy from the help desk employee. Here, the social engineer used some basic information (i.e., knowing the customer’s name), sympathy, and the fact that a help desk is primarily supposed to provide assistance, to manipulate the help desk to grant her unauthorized access to a client account. There are numerous other similar types of attacks, and entire books (e.g., Hadnagy, 2010 ; Mann, 2008 , 2013 ) and training courses on the topic (e.g., at the well-known hacking conference, BlackHat).

Phishing and Its Variants

Phishing is a specific type of social engineering crime that occurs using electronic communications, such as an email or a website. In it, criminals send an email, or create a website, that appears to be from a legitimate entity with the intention of conning individuals into divulging some sensitive information or performing a particular action. Today there are many different variants of phishing, including spear-phishing, vishing, smishing (or SMSishing), and whaling.

Spear-phishing is a targeted phishing attack on an individual that has been customized based on other key and pertinent information, such as their date of birth, current bank, Internet service provider, or email address. This additional information is used to enhance the appearance of legitimacy and thereby increase the effectiveness of the con. Spear-phishing is held to be the reason for several well-known crimes including “Celebgate,” where private photographs of actresses Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Upton, and Scarlett Johansson were stolen and later exposed online. The terms vishing and smishing represent phishing attacks that occur over the phone (i.e., voice), and via text messages (especially SMS, but including WhatsApp, etc.) respectively. These often overlap with traditional phone scams but may also be used in combination with email phishing attempts. Whaling is very similar to spear-phishing but targets high-profile individuals (the notion being that a whale is a “big phish”) such as company executives, with the goal of a higher payoff for criminals if the attack is successful.

The success of phishing attacks over the last decade has been phenomenal. To take the UK as an example, the City of London Police’s National Fraud Intelligence Bureau (NFIB) and the Get Safe Online security awareness campaign estimated that in 2015 alone, phishing scams cost victims £174 million. Moreover, Symantec ( 2017 ) estimates that spear-phishing emails as a category in themselves have drained $3 billion from businesses over the last three years. These estimates are likely to increase, as are the various ways in which criminals have targeted individuals.

In one phishing scam, criminals monitored a lady in the process of purchasing a home, and after disguising themselves as her solicitor they requested that she transfer £50,000 into their account (iTV News, 2015 ). This can be considered as a spear-phishing attack given the amount of information the criminals had on her and her activities, and how they used that information to achieve their goal (similar to the process of reconnaissance). There have also been emails sent to university students where criminals have posed as employees of the university’s finance department. They pretend to offer educational grants that can only be redeemed after students provide personal and banking details (BBC News, 2016a ). While emails are prominent tools, fake websites also are a popular avenue for phishing crimes. A 2017 study discovered hundreds of fake websites posing as banks, including HSBC, Standard Chartered, Barclays, and Natwest, that targeted the public (McGoogan, 2017 ). These websites looked identical to official sites and used similar domain names, such as hsbc-direct.com , barclaya.net , and lloydstsbs.com (note the additional letter or slight re-organization of bank name in these addresses).

A key observation about these attacks and those above is that criminals have sought to exploit many human psychological traits. These include a willingness to trust others and to be kind, the impact of anxiety and stress on decision making, personal needs and wants, and in some regards, the naivety in decision making. In the home purchase case, criminals firstly targeted the stressful process of purchasing a home, and then secondly, waited for a specific moment in time where they could impersonate the solicitor to request transfer of funds. While not privy to the email sent, the tone of the email must have emphasized the importance of transferring the funds immediately to secure the purchase. Fear of losing the prospective property, the overall anxiety of house buying, and trust in the (supposed) solicitor are undoubtedly factors that would have led to the transfer of funds. Mann ( 2008 ) mentions similar tricks as core to social engineering, and Iuga, Nurse, and Erola ( 2016 ) mention these tricks as increasing the susceptibility of individuals to phishing attacks.

In the case of the university students, criminals targeted a prime need of students during their time at university, i.e., financial support to fund their degrees and themselves. By using university logos and other information, they were able to pose as a legitimate entity and thereby not arouse the suspicion of students. This impersonation also occurs within the fake website example. Criminals prey on naïve decision-making abilities, or more specifically, the heuristics (or quick “rules of thumb”) that individuals apply to make decisions. Here, they are presenting emails and sites as we expect they should appear, thus deceiving us into accepting them and acting without detailed consideration. This process has previously been described via the psychological heuristic of representativeness by psychologists Tversky and Kahneman during the 1970s. The heuristic posits that humans often make decisions based on how representative an event is grounded on the evidence, rather than what may be probabilistically true (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973 ). Therefore, because the website or email appears to possess all of the key evidence (a logo, familiar names, etc.), its legitimacy is more likely to be accepted. This is only one example of the ways in which psychology overlaps with cybersecurity; many others can be found in Nurse, Creese, Goldsmith, and Lamberts. ( 2011a ).

Online Scams—Tech Support, Romance, and Catfishing