- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

The bright side of sports: a systematic review on well-being, positive emotions and performance

- David Peris-Delcampo 1 ,

- Antonio Núñez 2 ,

- Paula Ortiz-Marholz 3 ,

- Aurelio Olmedilla 4 ,

- Enrique Cantón 1 ,

- Javier Ponseti 2 &

- Alejandro Garcia-Mas 2

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 284 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The objective of this study is to conduct a systematic review regarding the relationship between positive psychological factors, such as psychological well-being and pleasant emotions, and sports performance.

This study, carried out through a systematic review using PRISMA guidelines considering the Web of Science, PsycINFO, PubMed and SPORT Discus databases, seeks to highlight the relationship between other more ‘positive’ factors, such as well-being, positive emotions and sports performance.

The keywords will be decided by a Delphi Method in two rounds with sport psychology experts.

Participants

There are no participants in the present research.

The main exclusion criteria were: Non-sport thema, sample younger or older than 20–65 years old, qualitative or other methodology studies, COVID-related, journals not exclusively about Psychology.

Main outcomes measures

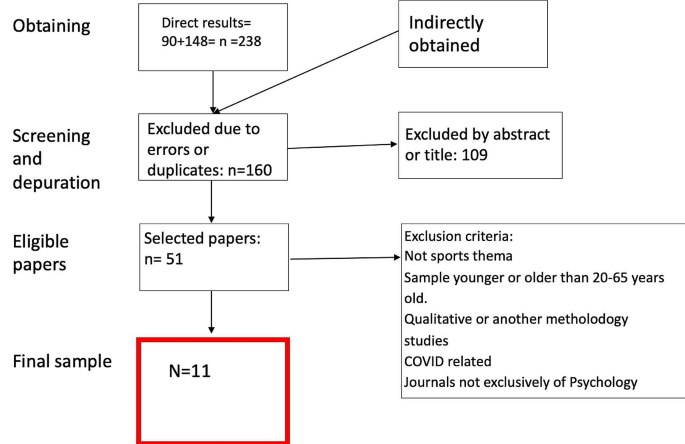

We obtained a first sample of 238 papers, and finally, this sample was reduced to the final sample of 11 papers.

The results obtained are intended to be a representation of the ‘bright side’ of sports practice, and as a complement or mediator of the negative variables that have an impact on athletes’ and coaches’ performance.

Conclusions

Clear recognition that acting on intrinsic motivation continues to be the best and most effective way to motivate oneself to obtain the highest levels of performance, a good perception of competence and a source of personal satisfaction.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent decades, research in the psychology of sport and physical exercise has focused on the analysis of psychological variables that could have a disturbing, unfavourable or detrimental role, including emotions that are considered ‘negative’, such as anxiety/stress, sadness or anger, concentrating on their unfavourable relationship with sports performance [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ], sports injuries [ 5 , 6 , 7 ] or, more generally, damage to the athlete’s health [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. The study of ‘positive’ emotions such as happiness or, more broadly, psychological well-being, has been postponed at this time, although in recent years this has seen an increase that reveals a field of study of great interest to researchers and professionals [ 11 , 12 , 13 ] including physiological, psychological, moral and social beneficial effects of the physical activity in comic book heroes such as Tintin, a team leader, which can serve as a model for promoting healthy lifestyles, or seeking ‘eternal youth’ [ 14 ].

Emotions in relation to their effects on sports practice and performance rarely go in one direction, being either negative or positive—generally positive and negative emotions do not act alone [ 15 ]. Athletes experience different emotions simultaneously, even if they are in opposition and especially if they are of mild or moderate intensity [ 16 ]. The athlete can feel satisfied and happy and at the same time perceive a high level of stress or anxiety before a specific test or competition. Some studies [ 17 ] have shown how sports participation and the perceived value of elite sports positively affect the subjective well-being of the athlete. This also seems to be the case in non-elite sports practice. The review by Mansfield et al. [ 18 ] showed that the published literature suggests that practising sports and dance, in a group or supported by peers, can improve the subjective well-being of the participants, and also identifies negative feelings towards competence and ability, although the quantity and quality of the evidence published is low, requiring better designed studies. All these investigations are also supported by the development of the concept of eudaimonic well-being [ 19 ], which is linked to the development of intrinsic motivation, not only in its aspect of enjoyment but also in its relationship with the perception of competition and overcoming and achieving goals, even if this is accompanied by other unpleasant hedonic emotions or even physical discomfort. Shortly after a person has practised sports, he will remember those feelings of exhaustion and possibly stiffness, linked to feelings of satisfaction and even enjoyment.

Furthermore, the mediating role of parents, coaches and other psychosocial agents can be significant. In this sense, Lemelin et al. [ 20 ], with the aim of investigating the role of autonomy support from parents and coaches in the prediction of well-being and performance of athletes, found that autonomy support from parents and coaches has positive relationships with the well-being of the athlete, but that only coach autonomy support is associated with sports performance. This research suggests that parents and coaches play important but distinct roles in athlete well-being and that coach autonomy support could help athletes achieve high levels of performance.

On the other hand, an analysis of emotions in the sociocultural environment in which they arise and gain meaning is always interesting, both from an individual perspective and from a sports team perspective. Adler et al. [ 21 ] in a study with military teams showed that teams with a strong emotional culture of optimism were better positioned to recover from poor performance, suggesting that organisations that promote an optimistic culture develop more resilient teams. Pekrun et al. [ 22 ] observed with mathematics students that individual success boosts emotional well-being, while placing people in high-performance groups can undermine it, which is of great interest in investigating the effectiveness and adjustment of the individual in sports teams.

There is still little scientific literature in the field of positive emotions and their relationship with sports practice and athlete performance, although their approach has long had its clear supporters [ 23 , 24 ]. It is comforting to observe the significant increase in studies in this field, since some authors (e.g [ 25 , 26 ]). . , point out the need to overcome certain methodological and conceptual problems, paying special attention to the development of specific instruments for the evaluation of well-being in the sports field and evaluation methodologies.

As McCarthy [ 15 ] indicates, positive emotions (hedonically pleasant) can be the catalysts for excellence in sport and deserve a space in our research and in professional intervention to raise the level of athletes’ performance. From a holistic perspective, positive emotions are permanently linked to psychological well-being and research in this field is necessary: firstly because of the leading role they play in human behaviour, cognition and affection, and secondly, because after a few years of international uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic and wars, it seems ‘healthy and intelligent’ to encourage positive emotions for our athletes. An additional reason is that they are known to improve motivational processes, reducing abandonment and negative emotional costs [ 11 ]. In this vein, concepts such as emotional intelligence make sense and can help to identify and properly manage emotions in the sports field and determine their relationship with performance [ 27 ] that facilitates the inclusion of emotional training programmes based on the ‘bright side’ of sports practice [ 28 ].

Based on all of the above, one might wonder how these positive emotions are related to a given event and what role each one of them plays in the athlete’s performance. Do they directly affect performance, or do they affect other psychological variables such as concentration, motivation and self-efficacy? Do they favour the availability and competent performance of the athlete in a competition? How can they be regulated, controlled for their own benefit? How can other psychosocial agents, such as parents or coaches, help to increase the well-being of their athletes?

This work aims to enhance the leading role, not the secondary, of the ‘good and pleasant side’ of sports practice, either with its own entity, or as a complement or mediator of the negative variables that have an impact on the performance of athletes and coaches. Therefore, the objective of this study is to conduct a systematic review regarding the relationship between positive psychological factors, such as psychological well-being and pleasant emotions, and sports performance. For this, the methodological criteria that constitute the systematic review procedure will be followed.

Materials and methods

This study was carried out through a systematic review using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) guidelines considering the Web of Science (WoS) and Psycinfo databases. These two databases were selected using the Delphi method [ 29 ]. It does not include a meta-analysis because there is great data dispersion due to the different methodologies used [ 30 ].

The keywords will be decided by the Delphi Method in two rounds with sport psychology experts. The results obtained are intended to be a representation of the ‘bright side’ of sports practice, and as a complement or mediator of the negative variables that have an impact on athletes’ and coaches’ performance.

It was determined that the main construct was to be psychological well-being, and that it was to be paired with optimism, healthy practice, realisation, positive mood, and performance and sport. The search period was limited to papers published between 2000 and 2023, and the final list of papers was obtained on February 13 , 2023. This research was conducted in two languages—English and Spanish—and was limited to psychological journals and specifically those articles where the sample was formed by athletes.

Each word was searched for in each database, followed by searches involving combinations of the same in pairs and then in trios. In relation to the results obtained, it was decided that the best approach was to group the words connected to positive psychology on the one hand, and on the other, those related to self-realisation/performance/health. In this way, it used parentheses to group words (psychological well-being; or optimism; or positive mood) with the Boolean ‘or’ between them (all three refer to positive psychology); and on the other hand, it grouped those related to performance/health/realisation (realisation; or healthy practice or performance), separating both sets of parentheses by the Boolean ‘and’’. To further filter the search, a keyword included in the title and in the inclusion criteria was added, which was ‘sport’ with the Boolean ‘and’’. In this way, the search achieved results that combined at least one of the three positive psychology terms and one of the other three.

Results (first phase)

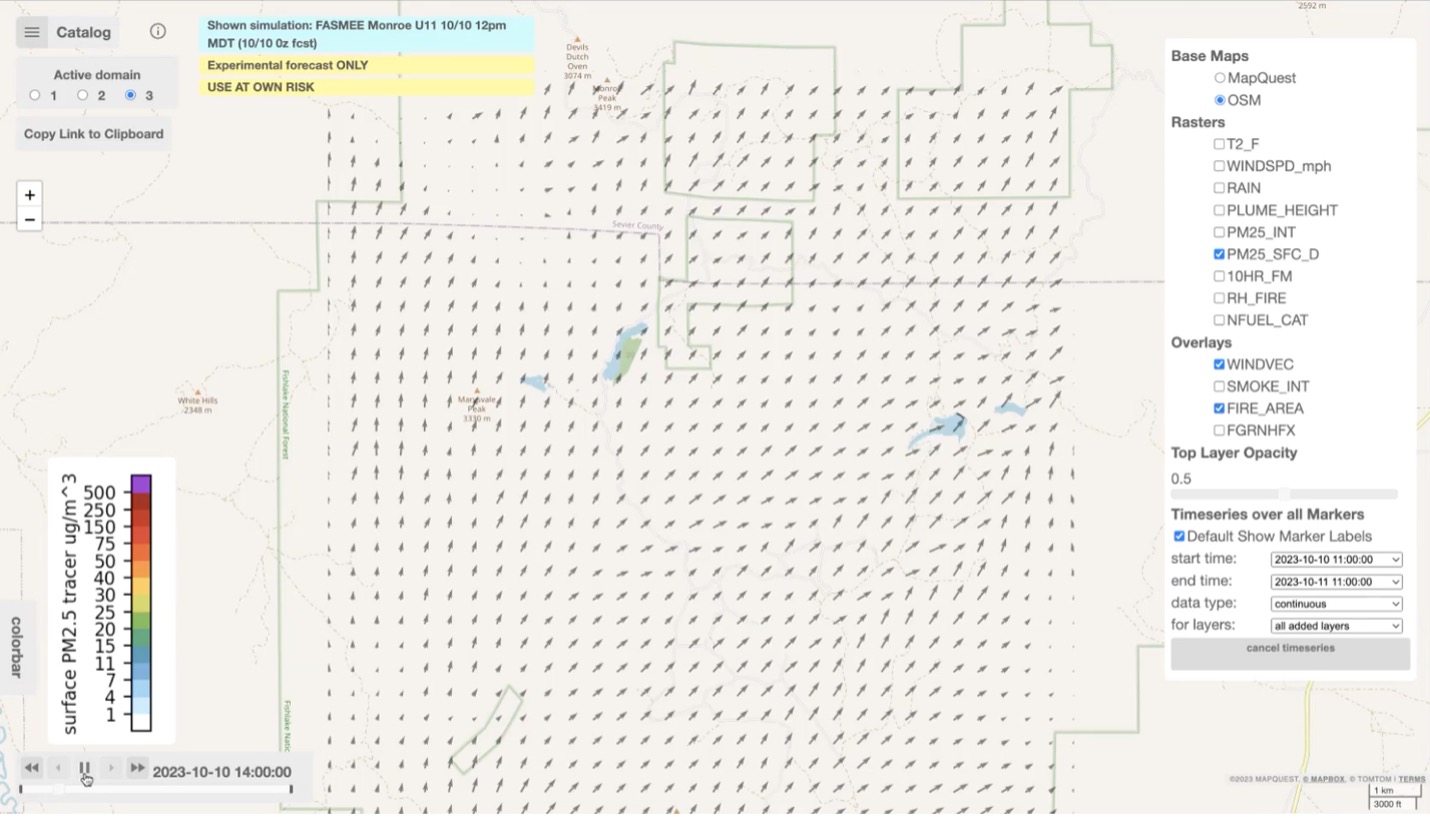

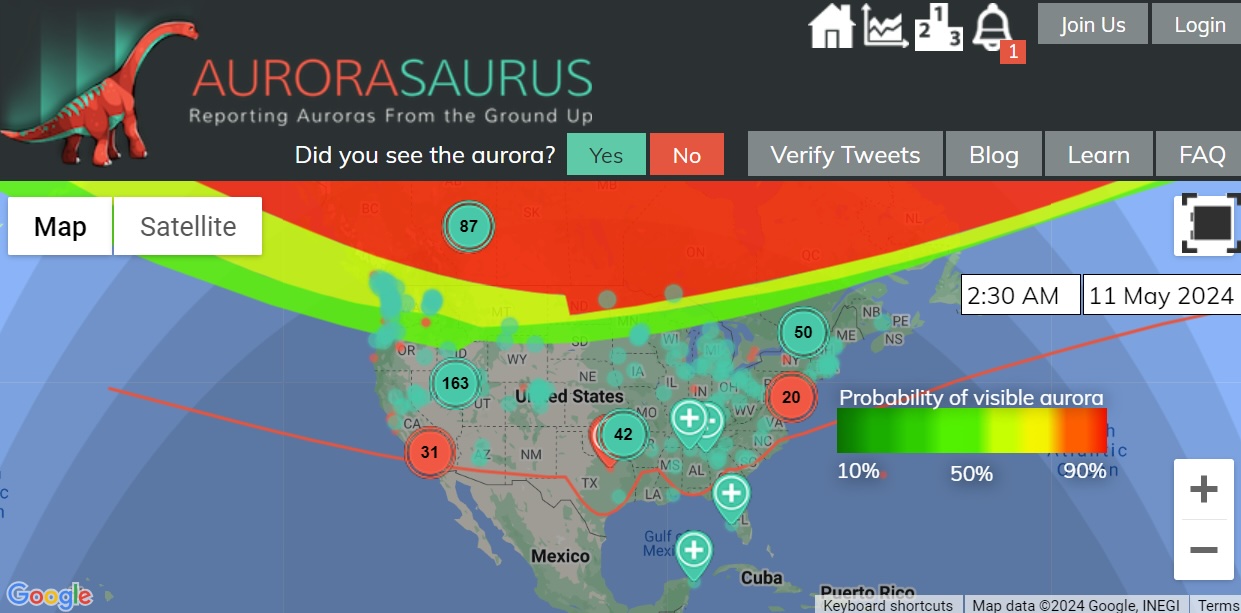

The mentioned keywords were cross-matched, obtaining the combination with a sufficient number of papers. From the first research phase, the total number of papers obtained was 238. Then screening was carried out by 4 well-differentiated phases that are summarised in Fig. 1 . These phases helped to reduce the original sample to a more accurate one.

Phases of the selection process for the final sample. Four phases were carried out to select the final sample of articles. The first phase allowed the elimination of duplicates. In the second stage, those that, by title or abstract, did not fit the objectives of the article were eliminated. Previously selected exclusion criteria were applied to the remaining sample. Thus, in phase 4, the final sample of 11 selected articles was obtained

Results (second phase)

The first screening examined the title, and the abstract if needed, excluding the papers that were duplicated, contained errors or someone with formal problems, low N or case studies. This screening allowed the initial sample to be reduced to a more accurate one with 109 papers selected.

Results (third phase)

This was followed by the second screening to examine the abstract and full texts, excluding if necessary papers related to non-sports themes, samples that were too old or too young for our interests, papers using qualitative methodologies, articles related to the COVID period, or others published in non-psychological journals. Furthermore, papers related to ‘negative psychological variables’’ were also excluded.

Results (fourth phase)

At the end of this second screening the remaining number of papers was 11. In this final phase we tried to organise the main characteristics and their main conclusions/results in a comprehensible list (Table 1 ). Moreover, in order to enrich our sample of papers, we decided to include some articles from other sources, mainly those presented in the introduction to sustain the conceptual framework of the concept ‘bright side’ of sports.

The usual position of the researcher of psychological variables that affect sports performance is to look for relationships between ‘negative’ variables, first in the form of basic psychological processes, or distorting cognitive behavioural, unpleasant or evaluable as deficiencies or problems, in a psychology for the ‘risk’ society, which emphasises the rehabilitation that stems from overcoming personal and social pathologies [ 31 ], and, lately, regarding the affectation of the athlete’s mental health [ 32 ]. This fact seems to be true in many cases and situations and to openly contradict the proclaimed psychological benefits of practising sports (among others: Cantón [ 33 ], ; Froment and González [ 34 ]; Jürgens [ 35 ]).

However, it is possible to adopt another approach focused on the ‘positive’ variables, also in relation to the athlete’s performance. This has been the main objective of this systematic review of the existing literature and far from being a novel approach, although a minority one, it fits perfectly with the definition of our area of knowledge in the broad field of health, as has been pointed out for some time [ 36 , 37 ].

After carrying out the aforementioned systematic review, a relatively low number of articles were identified by experts that met the established conditions—according to the PRISMA method [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]—regarding databases, keywords, and exclusion and inclusion criteria. These precautions were taken to obtain the most accurate results possible, and thus guarantee the quality of the conclusions.

The first clear result that stands out is the great difficulty in finding articles in which sports ‘performance’ is treated as a well-defined study variable adapted to the situation and the athletes studied. In fact, among the results (11 papers), only 3 associate one or several positive psychological variables with performance (which is evaluated in very different ways, combining objective measures with other subjective ones). This result is not surprising, since in several previous studies (e.g. Nuñez et al. [ 41 ]) using a systematic review, this relationship is found to be very weak and nuanced by the role of different mediating factors, such as previous sports experience or the competitive level (e.g. Rascado, et al. [ 42 ]; Reche, Cepero & Rojas [ 43 ]), despite the belief—even among professional and academic circles—that there is a strong relationship between negative variables and poor performance, and vice versa, with respect to the positive variables.

Regarding what has been evidenced in relation to the latter, even with these restrictions in the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the filters applied to the first findings, a true ‘galaxy’ of variables is obtained, which also belong to different categories and levels of psychological complexity.

A preliminary consideration regarding the current paradigm of sport psychology: although it is true that some recent works have already announced the swing of the pendulum on the objects of study of PD, by returning to the study of traits and dispositions, and even to the personality of athletes [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ], our results fully corroborate this trend. Faced with five variables present in the studies selected at the end of the systematic review, a total of three traits/dispositions were found, which were also the most repeated—optimism being present in four articles, mental toughness present in three, and finally, perfectionism—as the representative concepts of this field of psychology, which lately, as has already been indicated, is significantly represented in the field of research in this area [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. In short, the psychological variables that finally appear in the selected articles are: psychological well-being (PWB) [ 53 ]; self-compassion, which has recently been gaining much relevance with respect to the positive attributional resolution of personal behaviours [ 54 ], satisfaction with life (balance between sports practice, its results, and life and personal fulfilment [ 55 ], the existence of approach-achievement goals [ 56 ], and perceived social support [ 57 ]). This last concept is maintained transversally in several theoretical frameworks, such as Sports Commitment [ 58 ].

The most relevant concept, both quantitatively and qualitatively, supported by the fact that it is found in combination with different variables and situations, is not a basic psychological process, but a high-level cognitive construct: psychological well-being, in its eudaimonic aspect, first defined in the general population by Carol Ryff [ 59 , 60 ] and introduced at the beginning of this century in sport (e.g., Romero, Brustad & García-Mas [ 13 ], ; Romero, García-Mas & Brustad [ 61 ]). It is important to note that this concept understands psychological well-being as multifactorial, including autonomy, control of the environment in which the activity takes place, social relationships, etc.), meaning personal fulfilment through a determined activity and the achievement or progress towards goals and one’s own objectives, without having any direct relationship with simpler concepts, such as vitality or fun. In the selected studies, PWB appears in five of them, and is related to several of the other variables/traits.

The most relevant result regarding this variable is its link with motivational aspects, as a central axis that relates to different concepts, hence its connection to sports performance, as a goal of constant improvement that requires resistance, perseverance, management of errors and great confidence in the possibility that achievements can be attained, that is, associated with ideas of optimism, which is reflected in expectations of effectiveness.

If we detail the relationships more specifically, we can first review this relationship with the ‘way of being’, understood as personality traits or behavioural tendencies, depending on whether more or less emphasis is placed on their possibilities for change and learning. In these cases, well-being derives from satisfaction with progress towards the desired goal, for which resistance (mental toughness) and confidence (optimism) are needed. When, in addition, the search for improvement is constant and aiming for excellence, its relationship with perfectionism is clear, although it is a factor that should be explored further due to its potential negative effect, at least in the long term.

The relationship between well-being and satisfaction with life is almost tautological, in the precise sense that what produces well-being is the perception of a relationship or positive balance between effort (or the perception of control, if we use stricter terminology) and the results thereof (or the effectiveness of such control). This direct link is especially important when assessing achievement in personally relevant activities, which, in the case of the subjects evaluated in the papers, specifically concern athletes of a certain level of performance, which makes it a more valuable objective than would surely be found in the general population. And precisely because of this effect of the value of performance for athletes of a certain level, it also allows us to understand how well-being is linked to self-compassion, since as a psychological concept it is very close to that of self-esteem, but with a lower ‘demand’ or a greater ‘generosity’, when we encounter failures, mistakes or even defeats along the way, which offers us greater protection from the risk of abandonment and therefore reinforces persistence, a key element for any successful sports career [ 62 ].

It also has a very direct relationship with approach-achievement goals, since precisely one of the central aspects characterising this eudaimonic well-being and differentiating it from hedonic well-being is specifically its relationship with self-determined and persistent progress towards goals or achievements with incentive value for the person, as is sports performance evidently [ 63 ].

Finally, it is interesting to see how we can also find a facet or link relating to the aspects that are more closely-related to the need for human affiliation, with feeling part of a group or human collective, where we can recognise others and recognise ourselves in the achievements obtained and the social reinforcement of those themselves, as indicated by their relationship with perceived social support. This construct is very labile, in fact it is common to find results in which the pressure of social support is hardly differentiated, for example, from the parents of athletes and/or their coaches [ 64 ]. However, its relevance within this set of psychological variables and traits is proof of its possible conceptual validity.

Analysing the results obtained, the first conclusion is that in no case is an integrated model based solely on ‘positive’ variables or traits obtained, since some ‘negative’ ones appear (anxiety, stress, irrational thoughts), affecting the former.

The second conclusion is that among the positive elements the variable coping strategies (their use, or the perception of their effectiveness) and the traits of optimism, perfectionism and self-compassion prevail, since mental strength or psychological well-being (which also appear as important, but with a more complex nature) are seen to be participated in by the aforementioned traits.

Finally, it must be taken into account that the generation of positive elements, such as resilience, or the learning of coping strategies, are directly affected by the educational style received, or by the culture in which the athlete is immersed. Thus, the applied potential of these findings is great, but it must be calibrated according to the educational and/or cultural features of the specific setting.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are those evident and common in SR methodology using the PRISMA system, since the selection of keywords (and their logical connections used in the search), the databases, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria bias the work in its entirety and, therefore, constrain the generalisation of the results obtained.

Likewise, the conclusions must—based on the above and the results obtained—be made with the greatest concreteness and simplicity possible. Although we have tried to reduce these limitations as much as possible through the use of experts in the first steps of the method, they remain and must be considered in terms of the use of the results.

Future developments

Undoubtedly, progress is needed in research to more precisely elucidate the role of well-being, as it has been proposed here, from a bidirectional perspective: as a motivational element to push towards improvement and the achievement of goals, and as a product or effect of the self-determined and competent behaviour of the person, in relation to different factors, such as that indicated here of ‘perfectionism’ or the potential interference of material and social rewards, which are linked to sports performance—in our case—and that could act as a risk factor so that our achievements, far from being a source of well-being and satisfaction, become an insatiable demand in the search to obtain more and more frequent rewards.

From a practical point of view, an empirical investigation should be conducted to see if these relationships hold from a statistical point of view, either in the classical (correlational) or in the probabilistic (Bayesian Networks) plane.

The results obtained in this study, exclusively researched from the desk, force the authors to develop subsequent empirical and/or experimental studies in two senses: (1) what interrelationships exist between the so called ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ psychological variables and traits in sport, and in what sense are each of them produced; and, (2) from a global, motivational point of view, can currently accepted theoretical frameworks, such as SDT, easily accommodate this duality, which is becoming increasingly evident in applied work?

Finally, these studies should lead to proposals applied to the two fields that have appeared to be relevant: educational and cultural.

Application/transfer of results

A clear application of these results is aimed at guiding the training of sports and physical exercise practitioners, directing it towards strategies for assessing achievements, improvements and failure management, which keep them in line with well-being enhancement, eudaimonic, intrinsic and self-determined, which enhances the quality of their learning and their results and also favours personal health and social relationships.

Data availability

There are no further external data.

Cantón E, Checa I. Los estados emocionales y su relación con las atribuciones y las expectativas de autoeficacia en El deporte. Revista De Psicología Del Deporte. 2012;21(1):171–6.

Google Scholar

Cantón E, Checa I, Espejo B. (2015). Evidencias de validez convergente y test-criterio en la aplicación del Instrumento de Evaluación de Emociones en la Competición Deportiva. 24(2), 311–313.

Olmedilla A, Martins B, Ponseti-Verdaguer FJ, Ruiz-Barquín R, García-Mas A. It is not just stress: a bayesian Approach to the shape of the Negative Psychological Features Associated with Sport injuries. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020236 .

Article Google Scholar

Ong NCH, Chua JHE. Effects of psychological interventions on competitive anxiety in sport: a meta-analysis. Psycholy Sport Exerc. 2015;52:101836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101836 .

Candel MJ, Mompeán R, Olmedilla A, Giménez-Egido JM. Pensamiento catastrofista y evolución del estado de ánimo en futbolistas lesionados (Catastrophic thinking and temporary evolf mood state in injured football players). Retos. 2023;47:710–9.

Li C, Ivarsson A, Lam LT, Sun J. Basic Psychological needs satisfaction and frustration, stress, and sports Injury among University athletes: a Four-Wave prospective survey. Front Psychol. 2019;26:10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00665 .

Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Psychological predictors and consequences of injuries in sport settings. In: Anshel MH, Petrie TA, Steinfelt JA, editors. APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology, volume 1: Sport psychology. Volume 1. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2019. pp. 699–725. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000123035 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Godoy PS, Redondo AB, Olmedilla A. (2022). Indicadores De Salud mental en jugadoras de fútbol en función de la edad. J Univers Mov Perform 21(5).

Golding L, Gillingham RG, Perera NKP. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in high-performance athletes: a systematic review. Physician Sportsmed. 2020;48(3):247–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2020.1713708 .

Xanthopoulos MS, Benton T, Lewis J, Case JA, Master CL. Mental Health in the Young Athlete. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(11):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-01185-w .

Cantón E, Checa I, Vellisca-González MY. Bienestar psicológico Y ansiedad competitiva: El Papel De las estrategias de afrontamiento / competitive anxiety and Psychological Well-being: the role of coping strategies. Revista Costarricense De Psicología. 2015;34(2):71–8.

Hahn E. Emotions in sports. In: Hackfort D, Spielberg CD, editors. Anxiety in Sports. Taylor & Francis; 2021. pp. 153–62. ISBN: 9781315781594.

Carrasco A, Brustad R, García-Mas A. Bienestar psicológico Y Su uso en la psicología del ejercicio, la actividad física y El Deporte. Revista Iberoamericana De psicología del ejercicio y El Deporte. 2007;2(2):31–52.

García-Mas A, Olmedilla A, Laffage-Cosnier S, Cruz J, Descamps Y, Vivier C. Forever Young! Tintin’s adventures as an Example of Physical Activity and Sport. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):2349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042349 .

McCarthy P. Positive emotion in sport performance: current status and future directions. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psycholy. 2011;4(1):50–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2011.560955 .

Cerin E. Predictors of competitive anxiety direction in male Tae Kwon do practitioners: a multilevel mixed idiographic/nomothetic interactional approach. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2004;5(4):497–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00041-4 .

Silva A, Monteiro D, Sobreiro P. Effects of sports participation and the perceived value of elite sport on subjective well-being. Sport Soc. 2020;23(7):1202–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1613376 .

Mansfield L, Kay T, Meads C, Grigsby-Duffy L, Lane J, John A, et al. Sport and dance interventions for healthy young people (15–24 years) to promote subjective well-being: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020959 . e020959.

Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 .

Lemelin E, Verner-Filion J, Carpentier J, Carbonneau N, Mageau G. Autonomy support in sport contexts: the role of parents and coaches in the promotion of athlete well-being and performance. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2022;11(3):305–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000287 .

Adler AB, Bliese PD, Barsade SG, Sowden WJ. Hitting the mark: the influence of emotional culture on resilient performance. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(2):319–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000897 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pekrun R, Murayama K, Marsh HW, Goetz T, Frenzel AC. Happy fish in little ponds: testing a reference group model of achievement and emotion. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2019;117(1):166–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000230 .

Seligman M. Authentic happiness. New York: Free Press/Simon and Schuster; 2002.

Seligman M, Florecer. La Nueva psicología positiva y la búsqueda del bienestar. Editorial Océano; 2016.

Giles S, Fletcher D, Arnold R, Ashfield A, Harrison J. Measuring well-being in Sport performers: where are we now and how do we Progress? Sports Med. 2020;50(7):1255–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01274-z .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Piñeiro-Cossio J, Fernández-Martínez A, Nuviala A, Pérez-Ordás R. Psychological wellbeing in Physical Education and School sports: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030864 .

Gómez-García L, Olmedilla-Zafra A, Peris-Delcampo D. Inteligencia emocional y características psicológicas relevantes en mujeres futbolistas profesionales. Revista De Psicología Aplicada Al Deporte Y El Ejercicio Físico. 2023;15(72). https://doi.org/10.5093/rpadef2022a9 .

Balk YA, Englert C. Recovery self-regulation in sport: Theory, research, and practice. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching. SAGE Publications Inc.; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119897528 .

King PR Jr, Beehler GP, Donnelly K, Funderburk JS, Wray LO. A practical guide to applying the Delphi Technique in Mental Health Treatment Adaptation: the example of enhanced problem-solving training (E-PST). Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2021;52(4):376–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000371 .

Glass G. Primary, secondary, and Meta-Analysis of Research. Educational Researcher. 1976;5(10):3. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X005010003 .

Gillham J, Seligman M. Footsteps on the road to a positive psychology. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:163–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967( . 99)00055 – 8.

Castillo J. Salud mental en El Deporte individual: importancia de estrategias de afrontamiento eficaces. Fundación Universitaria Católica Lumen Gentium; 2021.

Cantón E. Deporte, salud, bienestar y calidad de vida. Cuad De Psicología Del Deporte. 2001;1(1):27–38.

Froment F, García-González A. Retos. 2017;33:3–9. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i33.50969 . Beneficios de la actividad física sobre la autoestima y la calidad de vida de personas mayores (Benefits of physical activity on self-esteem and quality of life of older people).

Jürgens I. Práctica deportiva y percepción de calidad de vida. Revista Int De Med Y Ciencias De La Actividad Física Y Del Deporte. 2006;6(22):62–74.

Carpintero H. (2004). Psicología, Comportamiento Y Salud. El Lugar De La Psicología en Los campos de conocimiento. Infocop Num Extr, 93–101.

Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Hoffmann T, Mulrow C, et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2001;74(9):790–9.

Royo M, Biblio-Guías. Revisiones sistemáticas: PRISMA 2020: guías oficiales para informar (redactar) una revisión sistemática. Universidad De Navarra. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016 .

Urrútia G, Bonfill X. PRISMA declaration: a proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicina Clínica. 2010;135(11):507–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2010.01.015 .

Núñez A, Ponseti FX, Sesé A, Garcia-Mas A. Anxiety and perceived performance in athletes and musicians: revisiting Martens. Revista De Psicología. Del Deporte/Journal Sport Psychol. 2020;29(1):21–8.

Rascado S, Rial-Boubeta A, Folgar M, Fernández D. Niveles De rendimiento y factores psicológicos en deportistas en formación. Reflexiones para entender la exigencia psicológica del alto rendimiento. Revista Iberoamericana De Psicología Del Ejercicio Y El Deporte. 2014;9(2):373–92.

Reche-García C, Cepero M, Rojas F. Efecto De La Experiencia deportiva en las habilidades psicológicas de esgrimistas del ranking nacional español. Cuad De Psicología Del Deporte. 2010;10(2):33–42.

Kang C, Bennett G, Welty-Peachey J. Five dimensions of brand personality traits in sport. Sport Manage Rev. 2016;19(4):441–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.01.004 .

De Vries R. The main dimensions of Sport personality traits: a Lexical Approach. Front Psychol. 2020;23:11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02211 .

Laborde S, Allen M, Katschak K, Mattonet K, Lachner N. Trait personality in sport and exercise psychology: a mapping review and research agenda. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2020;18(6):701–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570536 .

Stamp E, Crust L, Swann C, Perry J, Clough P, Marchant D. Relationships between mental toughness and psychological wellbeing in undergraduate students. Pers Indiv Differ. 2015;75:170–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.038 .

Nicholls A, Polman R, Levy A, Backhouse S. Mental toughness, optimism, pessimism, and coping among athletes. Personality Individ Differences. 2008;44(5):1182–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.11.011 .

Weissensteiner JR, Abernethy B, Farrow D, Gross J. Distinguishing psychological characteristics of expert cricket batsmen. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(1):74–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.07.003 .

García-Naveira A, Díaz-Morales J. Relationship between optimism/dispositional pessimism, performance and age in competitive soccer players. Revista Iberoamericana De Psicología Del Ejercicio Y El Deporte. 2010;5(1):45–59.

Reche C, Gómez-Díaz M, Martínez-Rodríguez A, Tutte V. Optimism as contribution to sports resilience. Revista Iberoamericana De Psicología Del Ejercicio Y El Deporte. 2018;13(1):131–6.

Lizmore MR, Dunn JGH, Causgrove Dunn J. Perfectionistic strivings, perfectionistic concerns, and reactions to poor personal performances among intercollegiate athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2017;33:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.07.010 .

Mansell P. Stress mindset in athletes: investigating the relationships between beliefs, challenge and threat with psychological wellbeing. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2021;57:102020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102020 .

Reis N, Kowalski K, Mosewich A, Ferguson L. Exploring Self-Compassion and versions of masculinity in men athletes. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2019;41(6):368–79. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2019-0061 .

Cantón E, Checa I, Budzynska N, Canton E, Esquiva Iy, Budzynska N. (2013). Coping, optimism and satisfaction with life among Spanish and Polish football players: a preliminary study. Revista de Psicología del Deporte. 22(2), 337–43.

Mulvenna M, Adie J, Sage L, Wilson N, Howat D. Approach-achievement goals and motivational context on psycho-physiological functioning and performance among novice basketball players. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2020;51:101714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101714 .

Malinauskas R, Malinauskiene V. The mediation effect of Perceived Social support and perceived stress on the relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Wellbeing in male athletes. Jorunal Hum Kinetics. 2018;65(1):291–303. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2018-0017 .

Scanlan T, Carpenter PJ, Simons J, Schmidt G, Keeler B. An introduction to the Sport Commitment Model. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1993;1(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.1.1 .

Ryff CD. Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: recent findings and future directions. Int Rev Econ. 2017;64(2):159–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0277-4 .

Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1 .

Romero-Carrasco A, García-Mas A, Brustad RJ. Estado del arte, y perspectiva actual del concepto de bienestar psicológico en psicología del deporte. Revista Latinoam De Psicología. 2009;41(2):335–47.

James IA, Medea B, Harding M, Glover D, Carraça B. The use of self-compassion techniques in elite footballers: mistakes as opportunities to learn. Cogn Behav Therapist. 2022;15:e43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X22000411 .

Fernández-Río J, Cecchini JA, Méndez-Giménez A, Terrados N, García M. Understanding olympic champions and their achievement goal orientation, dominance and pursuit and motivational regulations: a case study. Psicothema. 2018;30(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.302 .

Ortiz-Marholz P, Chirosa LJ, Martín I, Reigal R, García-Mas A. Compromiso Deportivo a través del clima motivacional creado por madre, padre y entrenador en jóvenes futbolistas. J Sport Psychol. 2016;25(2):245–52.

Ortiz-Marholz P, Gómez-López M, Martín I, Reigal R, García-Mas A, Chirosa LJ. Role played by the coach in the adolescent players’ commitment. Studia Physiol. 2016;58(3):184–98. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2016.03.716 .

Download references

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

General Psychology Department, Valencia University, Valencia, 46010, Spain

David Peris-Delcampo & Enrique Cantón

Basic Psychology and Pedagogy Departments, Balearic Islands University, Palma de Mallorca, 07122, Spain

Antonio Núñez, Javier Ponseti & Alejandro Garcia-Mas

Education and Social Sciences Faculty, Andres Bello University, Santiago, 7550000, Chile

Paula Ortiz-Marholz

Personality, Evaluation and Psychological Treatment Deparment, Murcia University, Campus MareNostrum, Murcia, 30100, Spain

Aurelio Olmedilla

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization, AGM, EC and ANP.; planification, AO; methodology, ANP, AGM and PO.; software, ANP, DP and PO.; validation, ANP and PO.; formal analysis, DP, PO and ANP; investigation, DP, PO and ANP.; resources, DVP and JP; data curation, AO and DP.; writing—original draft preparation, ANP, DP and AGM; writing—review and editing, EC and JP.; visualization, ANP and PO.; supervision, AGM.; project administration, DP.; funding acquisition, DP and JP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Antonio Núñez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peris-Delcampo, D., Núñez, A., Ortiz-Marholz, P. et al. The bright side of sports: a systematic review on well-being, positive emotions and performance. BMC Psychol 12 , 284 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01769-8

Download citation

Received : 04 October 2023

Accepted : 07 May 2024

Published : 21 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01769-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Positive emotions

- Sports performance

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America, Education Academy, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Psychological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Methodology

Roles Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Kinesiology and Sport Management, Honors College, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Education, Health and Well-Being, University of Wolverhampton, Walsall, West Midlands, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Research & Innovation, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia

- Marc Lochbaum,

- Elisabeth Stoner,

- Tristen Hefner,

- Sydney Cooper,

- Andrew M. Lane,

- Peter C. Terry

- Published: February 16, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Sport psychology as an academic pursuit is nearly two centuries old. An enduring goal since inception has been to understand how psychological techniques can improve athletic performance. Although much evidence exists in the form of meta-analytic reviews related to sport psychology and performance, a systematic review of these meta-analyses is absent from the literature. We aimed to synthesize the extant literature to gain insights into the overall impact of sport psychology on athletic performance. Guided by the PRISMA statement for systematic reviews, we reviewed relevant articles identified via the EBSCOhost interface. Thirty meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 met the inclusion criteria, covering 16 distinct sport psychology constructs. Overall, sport psychology interventions/variables hypothesized to enhance performance (e.g., cohesion, confidence, mindfulness) were shown to have a moderate beneficial effect ( d = 0.51), whereas variables hypothesized to be detrimental to performance (e.g., cognitive anxiety, depression, ego climate) had a small negative effect ( d = -0.21). The quality rating of meta-analyses did not significantly moderate the magnitude of observed effects, nor did the research design (i.e., intervention vs. correlation) of the primary studies included in the meta-analyses. Our review strengthens the evidence base for sport psychology techniques and may be of great practical value to practitioners. We provide recommendations for future research in the area.

Citation: Lochbaum M, Stoner E, Hefner T, Cooper S, Lane AM, Terry PC (2022) Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0263408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

Editor: Claudio Imperatori, European University of Rome, ITALY

Received: September 28, 2021; Accepted: January 18, 2022; Published: February 16, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Lochbaum et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Sport performance matters. Verifying its global importance requires no more than opening a newspaper to the sports section, browsing the internet, looking at social media outlets, or scanning abundant sources of sport information. Sport psychology is an important avenue through which to better understand and improve sport performance. To date, a systematic review of published sport psychology and performance meta-analyses is absent from the literature. Given the undeniable importance of sport, the history of sport psychology in academics since 1830, and the global rise of sport psychology journals and organizations, a comprehensive systematic review of the meta-analytic literature seems overdue. Thus, we aimed to consolidate the existing literature and provide recommendations for future research.

The development of sport psychology

The history of sport psychology dates back nearly 200 years. Terry [ 1 ] cites Carl Friedrich Koch’s (1830) publication titled [in translation] Calisthenics from the Viewpoint of Dietetics and Psychology [ 2 ] as perhaps the earliest publication in the field, and multiple commentators have noted that sport psychology experiments occurred in the world’s first psychology laboratory, established by Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig in 1879 [ 1 , 3 ]. Konrad Rieger’s research on hypnosis and muscular endurance, published in 1884 [ 4 ] and Angelo Mosso’s investigations of the effects of mental fatigue on physical performance, published in 1891 [ 5 ] were other early landmarks in the development of applied sport psychology research. Following the efforts of Koch, Wundt, Rieger, and Mosso, sport psychology works appeared with increasing regularity, including Philippe Tissié’s publications in 1894 [ 6 , 7 ] on psychology and physical training, and Pierre de Coubertin’s first use of the term sport psychology in his La Psychologie du Sport paper in 1900 [ 8 ]. In short, the history of sport psychology and performance research began as early as 1830 and picked up pace in the latter part of the 19 th century. Early pioneers, who helped shape sport psychology include Wundt, recognized as the “father of experimental psychology”, Tissié, the founder of French physical education and Legion of Honor awardee in 1932, and de Coubertin who became the father of the modern Olympic movement and founder of the International Olympic Committee.

Sport psychology flourished in the early 20 th century [see 1, 3 for extensive historic details]. For instance, independent laboratories emerged in Berlin, Germany, established by Carl Diem in 1920; in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia, established respectively by Avksenty Puni and Piotr Roudik in 1925; and in Champaign, Illinois USA, established by Coleman Griffith, also in 1925. The period from 1950–1980 saw rapid strides in sport psychology, with Franklin Henry establishing this field of study as independent of physical education in the landscape of American and eventually global sport science and kinesiology graduate programs [ 1 ]. In addition, of great importance in the 1960s, three international sport psychology organizations were established: namely, the International Society for Sport Psychology (1965), the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity (1966), and the European Federation of Sport Psychology (1969). Since that time, the Association of Applied Sport Psychology (1986), the South American Society for Sport Psychology (1986), and the Asian-South Pacific Association of Sport Psychology (1989) have also been established.

The global growth in academic sport psychology has seen a large number of specialist publications launched, including the following journals: International Journal of Sport Psychology (1970), Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (1979), The Sport Psychologist (1987), Journal of Applied Sport Psychology (1989), Psychology of Sport and Exercise (2000), International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2003), Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology (2007), International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology (2008), Journal of Sport Psychology in Action (2010), Sport , Exercise , and Performance Psychology (2014), and the Asian Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology (2021).

In turn, the growth in journal outlets has seen sport psychology publications burgeon. Indicative of the scale of the contemporary literature on sport psychology, searches completed in May 2021 within the Web of Science Core Collection, identified 1,415 publications on goal setting and sport since 1985; 5,303 publications on confidence and sport since 1961; and 3,421 publications on anxiety and sport since 1980. In addition to academic journals, several comprehensive edited textbooks have been produced detailing sport psychology developments across the world, such as Hanrahan and Andersen’s (2010) Handbook of Applied Sport Psychology [ 9 ], Schinke, McGannon, and Smith’s (2016) International Handbook of Sport Psychology [ 10 ], and Bertollo, Filho, and Terry’s (2021) Advancements in Mental Skills Training [ 11 ] to name just a few. In short, sport psychology is global in both academic study and professional practice.

Meta-analysis in sport psychology

Several meta-analysis guides, computer programs, and sport psychology domain-specific primers have been popularized in the social sciences [ 12 , 13 ]. Sport psychology academics have conducted quantitative reviews on much studied constructs since the 1980s, with the first two appearing in 1983 in the form of Feltz and Landers’ meta-analysis on mental practice [ 14 ], which included 98 articles dating from 1934, and Bond and Titus’ cross-disciplinary meta-analysis on social facilitation [ 15 ], which summarized 241 studies including Triplett’s (1898) often-cited study of social facilitation in cycling [ 16 ]. Although much meta-analytic evidence exists for various constructs in sport and exercise psychology [ 12 ] including several related to performance [ 17 ], the evidence is inconsistent. For example, two meta-analyses, both ostensibly summarizing evidence of the benefits to performance of task cohesion [ 18 , 19 ], produced very different mean effects ( d = .24 vs d = 1.00) indicating that the true benefit lies somewhere in a wide range from small to large. Thus, the lack of a reliable evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques represents a significant gap in the knowledge base for practitioners and researchers alike. A comprehensive systematic review of all published meta-analyses in the field of sport psychology has yet to be published.

Purpose and aim

We consider this review to be both necessary and long overdue for the following reasons: (a) the extensive history of sport psychology and performance research; (b) the prior publication of many meta-analyses summarizing various aspects of sport psychology research in a piecemeal fashion [ 12 , 17 ] but not its totality; and (c) the importance of better understanding and hopefully improving sport performance via the use of interventions based on solid evidence of their efficacy. Hence, we aimed to collate and evaluate this literature in a systematic way to gain improved understanding of the impact of sport psychology variables on sport performance by construct, research design, and meta-analysis quality, to enhance practical knowledge of sport psychology techniques and identify future lines of research inquiry. By systematically reviewing all identifiable meta-analytic reviews linking sport psychology techniques with sport performance, we aimed to evaluate the strength of the evidence base underpinning sport psychology interventions.

Materials and methods

This systematic review of meta-analyses followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 20 ]. We did not register our systematic review protocol in a database. However, we specified our search strategy, inclusion criteria, data extraction, and data analyses in advance of writing our manuscript. All details of our work are available from the lead author. Concerning ethics, this systematic review received a waiver from Texas Tech University Human Subject Review Board as it concerned archival data (i.e., published meta-analyses).

Eligibility criteria

Published meta-analyses were retained for extensive examination if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) included meta-analytic data such as mean group, between or within-group differences or correlates; (b) published prior to January 31, 2021; (c) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (d) investigated a recognized sport psychology construct; and (e) meta-analyzed data concerned with sport performance. There was no language of publication restriction. To align with our systematic review objectives, we gave much consideration to study participants and performance outcomes. Across multiple checks, all authors confirmed study eligibility. Three authors (ML, AL, and PT) completed the final inclusion assessments.

Information sources

Authors searched electronic databases, personal meta-analysis history, and checked with personal research contacts. Electronic database searches occurred in EBSCOhost with the following individual databases selected: APA PsycINFO, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SPORTDiscus. An initial search concluded October 1, 2020. ML, AL, and PT rechecked the identified studies during the February–March, 2021 period, which resulted in the identification of two additional meta-analyses [ 21 , 22 ].

Search protocol

ML and ES initially conducted independent database searches. For the first search, ML used the following search terms: sport psychology with meta-analysis or quantitative review and sport and performance or sport* performance. For the second search, ES utilized a sport psychology textbook and used the chapter title terms (e.g., goal setting). In EBSCOhost, both searches used the advanced search option that provided three separate boxes for search terms such as box 1 (sport psychology), box 2 (meta-analysis), and box 3 (performance). Specific details of our search strategy were:

Search by ML:

- sport psychology, meta-analysis, sport and performance

- sport psychology, meta-analysis or quantitative review, sport* performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport and performance

- sport psychology, quantitative review, sport* performance

Search by ES:

- mental practice or mental imagery or mental rehearsal and sports performance and meta-analysis

- goal setting and sports performance and meta-analysis

- anxiety and stress and sports performance and meta-analysis

- competition and sports performance and meta-analysis

- diversity and sports performance and meta-analysis

- cohesion and sports performance and meta-analysis

- imagery and sports performance and meta-analysis

- self-confidence and sports performance and meta-analysis

- concentration and sports performance and meta-analysis

- athletic injuries and sports performance and meta-analysis

- overtraining and sports performance and meta-analysis

- children and sports performance and meta-analysis

The following specific search of the EBSCOhost with SPORTDiscus, APA PsycINFO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and ERIC databases, returned six results from 2002–2020, of which three were included [ 18 , 19 , 23 ] and three were excluded because they were not meta-analyses.

- Box 1 cohesion

- Box 2 sports performance

- Box 3 meta-analysis

Study selection

As detailed in the PRISMA flow chart ( Fig 1 ) and the specified inclusion criteria, a thorough study selection process was used. As mentioned in the search protocol, two authors (ML and ES) engaged independently with two separate searches and then worked together to verify the selected studies. Next, AL and PT examined the selected study list for accuracy. ML, AL, and PT, whilst rating the quality of included meta-analyses, also re-examined all selected studies to verify that each met the predetermined study inclusion criteria. Throughout the study selection process, disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.g001

Data extraction process

Initially, ML, TH, and ES extracted data items 1, 2, 3 and 8 (see Data items). Subsequently, ML, AL, and PT extracted the remaining data (items 4–7, 9, 10). Checks occurred during the extraction process for potential discrepancies (e.g., checking the number of primary studies in a meta-analysis). It was unnecessary to contact any meta-analysis authors for missing information or clarification during the data extraction process because all studies reported the required information. Across the search for meta-analyses, all identified studies were reported in English. Thus, no translation software or searching out a native speaker occurred. All data extraction forms (e.g., data items and individual meta-analysis quality) are available from the first author.

To help address our main aim, we extracted the following information from each meta-analysis: (1) author(s); (2) publication year; (3) construct(s); (4) intervention based meta-analysis (yes, no, mix); (5) performance outcome(s) description; (6) number of studies for the performance outcomes; (7) participant description; (8) main findings; (9) bias correction method/results; and (10) author(s) stated conclusions. For all information sought, we coded missing information as not reported.

Individual meta-analysis quality

ML, AL, and PT independently rated the quality of individual meta-analysis on the following 25 points found in the PRISMA checklist [ 20 ]: title; abstract structured summary; introduction rationale, objectives, and protocol and registration; methods eligibility criteria, information sources, search, study selection, data collection process, data items, risk of bias of individual studies, summary measures, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; results study selection, study characteristics, risk of bias within studies, results of individual studies, synthesis of results, and risk of bias across studies; discussion summary of evidence, limitations, and conclusions; and funding. All meta-analyses were rated for quality by two coders to facilitate inter-coder reliability checks, and the mean quality ratings were used in subsequent analyses. One author (PT), having completed his own ratings, received the incoming ratings from ML and AL and ran the inter-coder analysis. Two rounds of ratings occurred due to discrepancies for seven meta-analyses, mainly between ML and AL. As no objective quality categorizations (i.e., a point system for grouping meta-analyses as poor, medium, good) currently exist, each meta-analysis was allocated a quality score of up to a maximum of 25 points. All coding records are available upon request.

Planned methods of analysis

Several preplanned methods of analysis occurred. We first assessed the mean quality rating of each meta-analysis based on our 25-point PRISMA-based rating system. Next, we used a median split of quality ratings to determine whether standardized mean effects (SMDs) differed by the two formed categories, higher and lower quality meta-analyses. Meta-analysis authors reported either of two different effect size metrics (i.e., r and SMD); hence we converted all correlational effects to SMD (i.e., Cohen’s d ) values using an online effect size calculator ( www.polyu.edu.hk/mm/effectsizefaqs/calculator/calculator.html ). We interpreted the meaningfulness of effects based on Cohen’s interpretation [ 24 ] with 0.20 as small, 0.50 as medium, 0.80 as large, and 1.30 as very large. As some psychological variables associate negatively with performance (e.g., confusion [ 25 ], cognitive anxiety [ 26 ]) whereas others associate positively (e.g., cohesion [ 23 ], mental practice [ 14 ]), we grouped meta-analyses according to whether the hypothesized effect with performance was positive or negative, and summarized the overall effects separately. By doing so, we avoided a scenario whereby the demonstrated positive and negative effects canceled one another out when combined. The effect of somatic anxiety on performance, which is hypothesized to follow an inverted-U relationship, was categorized as neutral [ 35 ]. Last, we grouped the included meta-analyses according to whether the primary studies were correlational in nature or involved an intervention and summarized these two groups of meta-analyses separately.

Study characteristics

Table 1 contains extracted data from 30 meta-analyses meeting the inclusion criteria, dating from 1983 [ 14 ] to 2021 [ 21 ]. The number of primary studies within the meta-analyses ranged from three [ 27 ] to 109 [ 28 ]. In terms of the description of participants included in the meta-analyses, 13 included participants described simply as athletes, whereas other meta-analyses identified a mix of elite athletes (e.g., professional, Olympic), recreational athletes, college-aged volunteers (many from sport science departments), younger children to adolescents, and adult exercisers. Of the 30 included meta-analyses, the majority ( n = 18) were published since 2010. The decadal breakdown of meta-analyses was 1980–1989 ( n = 1 [ 14 ]), 1990–1999 ( n = 6 [ 29 – 34 ]), 2000–2009 ( n = 5 [ 23 , 25 , 26 , 35 , 36 ]), 2010–2019 ( n = 12 [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 27 , 37 – 43 , 48 ]), and 2020–2021 ( n = 6 [ 21 , 28 , 44 – 47 ]).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t001

As for the constructs covered, we categorized the 30 meta-analyses into the following areas: mental practice/imagery [ 14 , 29 , 30 , 42 , 46 , 47 ], anxiety [ 26 , 31 , 32 , 35 ], confidence [ 26 , 35 , 36 ], cohesion [ 18 , 19 , 23 ], goal orientation [ 22 , 44 , 48 ], mood [ 21 , 25 , 34 ], emotional intelligence [ 40 ], goal setting [ 33 ], interventions [ 37 ], mindfulness [ 27 ], music [ 28 ], neurofeedback training [ 43 ], perfectionism [ 39 ], pressure training [ 45 ], quiet eye training [ 41 ], and self-talk [ 38 ]. Multiple effects were generated from meta-analyses that included more than one construct (e.g., tension, depression, etc. [ 21 ]; anxiety and confidence [ 26 ]). In relation to whether the meta-analyses included in our review assessed the effects of a sport psychology intervention on performance or relationships between psychological constructs and performance, 13 were intervention-based, 14 were correlational, two included a mix of study types, and one included a large majority of cross-sectional studies ( Table 1 ).

A wide variety of performance outcomes across many sports was evident, such as golf putting, dart throwing, maximal strength, and juggling; or categorical outcomes such as win/loss and Olympic team selection. Given the extensive list of performance outcomes and the incomplete descriptions provided in some meta-analyses, a clear categorization or count of performance types was not possible. Sufficient to conclude, researchers utilized many performance outcomes across a wide range of team and individual sports, motor skills, and strength and aerobic tasks.

Effect size data and bias correction

To best summarize the effects, we transformed all correlations to SMD values (i.e., Cohen’s d ). Across all included meta-analyses shown in Table 2 and depicted in Fig 2 , we identified 61 effects. Having corrected for bias, effect size values were assessed for meaningfulness [ 24 ], which resulted in 15 categorized as negligible (< ±0.20), 29 as small (±0.20 to < 0.50), 13 as moderate (±0.50 to < 0.80), 2 as large (±0.80 to < 1.30), and 1 as very large (≥ 1.30).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t002

Study quality rating results and summary analyses

Following our PRISMA quality ratings, intercoder reliability coefficients were initially .83 (ML, AL), .95 (ML, PT), and .90 (AL, PT), with a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .89. To achieve improved reliability (i.e., r mean > .90), ML and AL re-examined their ratings. As a result, intercoder reliability increased to .98 (ML, AL), .96 (ML, PT), and .92 (AL, PT); a mean intercoder reliability coefficient of .95. Final quality ratings (i.e., the mean of two coders) ranged from 13 to 25 ( M = 19.03 ± 4.15). Our median split into higher ( M = 22.83 ± 1.08, range 21.5–25, n = 15) and lower ( M = 15.47 ± 2.42, range 13–20.5, n = 15) quality groups produced significant between-group differences in quality ( F 1,28 = 115.62, p < .001); hence, the median split met our intended purpose. The higher quality group of meta-analyses were published from 2015–2021 (median 2018) and the lower quality group from 1983–2014 (median 2000). It appears that meta-analysis standards have risen over the years since the PRISMA criteria were first introduced in 2009. All data for our analyses are shown in Table 2 .

Table 3 contains summary statistics with bias-corrected values used in the analyses. The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a positive impact on performance was of moderate magnitude ( d = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.42, 0.58, n = 36). The overall mean effect for sport psychology constructs hypothesized to have a negative impact on performance was small in magnitude ( d = -0.21, 95% CI -0.31, -0.11, n = 24). In both instances, effects were larger, although not significantly so, among meta-analyses of higher quality compared to those of lower quality. Similarly, mean effects were larger but not significantly so, where reported effects in the original studies were based on interventional rather than correlational designs. This trend only applied to hypothesized positive effects because none of the original studies in the meta-analyses related to hypothesized negative effects used interventional designs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408.t003

In this systematic review of meta-analyses, we synthesized the available evidence regarding effects of sport psychology interventions/constructs on sport performance. We aimed to consolidate the literature, evaluate the potential for meta-analysis quality to influence the results, and suggest recommendations for future research at both the single study and quantitative review stages. During the systematic review process, several meta-analysis characteristics came to light, such as the number of meta-analyses of sport psychology interventions (experimental designs) compared to those summarizing the effects of psychological constructs (correlation designs) on performance, the number of meta-analyses with exclusively athletes as participants, and constructs featuring in multiple meta-analyses, some of which (e.g., cohesion) produced very different effect size values. Thus, although our overall aim was to evaluate the strength of the evidence base for use of psychological interventions in sport, we also discuss the impact of these meta-analysis characteristics on the reliability of the evidence.

When seen collectively, results of our review are supportive of using sport psychology techniques to help improve performance and confirm that variations in psychological constructs relate to variations in performance. For constructs hypothesized to have a positive effect on performance, the mean effect strength was moderate ( d = 0.51) although there was substantial variation between constructs. For example, the beneficial effects on performance of task cohesion ( d = 1.00) and self-efficacy ( d = 0.82) are large, and the available evidence base for use of mindfulness interventions suggests a very large beneficial effect on performance ( d = 1.35). Conversely, some hypothetically beneficial effects (2 of 36; 5.6%) were in the negligible-to-small range (0.15–0.20) and most beneficial effects (19 of 36; 52.8%) were in the small-to-moderate range (0.22–0.49). It should be noted that in the world of sport, especially at the elite level, even a small beneficial effect on performance derived from a psychological intervention may prove the difference between success and failure and hence small effects may be of great practical value. To put the scale of the benefits into perspective, an authoritative and extensively cited review of healthy eating and physical activity interventions [ 49 ] produced an overall pooled effect size of 0.31 (compared to 0.51 for our study), suggesting sport psychology interventions designed to improve performance are generally more effective than interventions designed to promote healthy living.

Among hypothetically negative effects (e.g., ego climate, cognitive anxiety, depression), the mean detrimental effect was small ( d = -0.21) although again substantial variation among constructs was evident. Some hypothetically negative constructs (5 of 24; 20.8%) were found to actually provide benefits to performance, albeit in the negligible range (0.02–0.12) and only two constructs (8.3%), both from Lochbaum and colleagues’ POMS meta-analysis [ 21 ], were shown to negatively affect performance above a moderate level (depression: d = -0.64; total mood disturbance, which incorporates the depression subscale: d = -0.84). Readers should note that the POMS and its derivatives assess six specific mood dimensions rather than the mood construct more broadly, and therefore results should not be extrapolated to other dimensions of mood [ 50 ].

Mean effects were larger among higher quality than lower quality meta-analyses for both hypothetically positive ( d = 0.54 vs d = 0.45) and negative effects ( d = -0.25 vs d = 0.17), but in neither case were the differences significant. It is reasonable to assume that the true effects were derived from the higher quality meta-analyses, although our conclusions remain the same regardless of study quality. Overall, our findings provide a more rigorous evidence base for the use of sport psychology techniques by practitioners than was previously available, representing a significant contribution to knowledge. Moreover, our systematic scrutiny of 30 meta-analyses published between 1983 and 2021 has facilitated a series of recommendations to improve the quality of future investigations in the sport psychology area.

Recommendations

The development of sport psychology as an academic discipline and area of professional practice relies on using evidence and theory to guide practice. Hence, a strong evidence base for the applied work of sport psychologists is of paramount importance. Although the beneficial effects of some sport psychology techniques are small, it is important to note the larger performance benefits for other techniques, which may be extremely meaningful for applied practice. Overall, however, especially given the heterogeneity of the observed effects, it would be wise for applied practitioners to avoid overpromising the benefits of sport psychology services to clients and perhaps underdelivering as a result [ 1 ].

The results of our systematic review can be used to generate recommendations for how the profession might conduct improved research to better inform applied practice. Much of the early research in sport psychology was exploratory and potential moderating variables were not always sufficiently controlled. Terry [ 51 ] outlined this in relation to the study of mood-performance relationships, identifying that physical and skills factors will very likely exert a greater influence on performance than psychological factors. Further, type of sport (e.g., individual vs. team), duration of activity (e.g., short vs. long duration), level of competition (e.g., elite vs. recreational), and performance measure (e.g., norm-referenced vs. self-referenced) have all been implicated as potential moderators of the relationship between psychological variables and sport performance [ 51 ]. To detect the relatively subtle effects of psychological effects on performance, research designs need to be sufficiently sensitive to such potential confounds. Several specific methodological issues are worth discussing.

The first issue relates to measurement. Investigating the strength of a relationship requires the measured variables to be valid, accurate and reliable. Psychological variables in the meta-analyses we reviewed relied primarily on self-report outcome measures. The accuracy of self-report data requires detailed inner knowledge of thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Research shows that the accuracy of self-report information is subject to substantial individual differences [ 52 , 53 ]. Therefore, self-report data, at best, are an estimate of the measure. Measurement issues are especially relevant to the assessment of performance, and considerable measurement variation was evident between meta-analyses. Some performance measures were more sensitive, especially those assessing physical performance relative to what is normal for the individual performer (i.e., self-referenced performance). Hence, having multiple baseline indicators of performance increases the probability of identifying genuine performance enhancement derived from a psychological intervention [ 54 ].

A second issue relates to clarifying the rationale for how and why specific psychological variables might influence performance. A comprehensive review of prerequisites and precursors of athletic talent [ 55 ] concluded that the superiority of Olympic champions over other elite athletes is determined in part by a range of psychological variables, including high intrinsic motivation, determination, dedication, persistence, and creativity, thereby identifying performance-related variables that might benefit from a psychological intervention. Identifying variables that influence the effectiveness of interventions is a challenging but essential issue for researchers seeking to control and assess factors that might influence results [ 49 ]. A key part of this process is to use theory to propose the mechanism(s) by which an intervention might affect performance and to hypothesize how large the effect might be.