Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice (2016)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

Bullying, long tolerated by many as a rite of passage into adulthood, is now recognized as a major and preventable public health problem, one that can have long-lasting consequences ( McDougall and Vaillancourt, 2015 ; Wolke and Lereya, 2015 ). Those consequences—for those who are bullied, for the perpetrators of bullying, and for witnesses who are present during a bullying event—include poor school performance, anxiety, depression, and future delinquent and aggressive behavior. Federal, state, and local governments have responded by adopting laws and implementing programs to prevent bullying and deal with its consequences. However, many of these responses have been undertaken with little attention to what is known about bullying and its effects. Even the definition of bullying varies among both researchers and lawmakers, though it generally includes physical and verbal behavior, behavior leading to social isolation, and behavior that uses digital communications technology (cyberbullying). This report adopts the term “bullying behavior,” which is frequently used in the research field, to cover all of these behaviors.

Bullying behavior is evident as early as preschool, although it peaks during the middle school years ( Currie et al., 2012 ; Vaillancourt et al., 2010 ). It can occur in diverse social settings, including classrooms, school gyms and cafeterias, on school buses, and online. Bullying behavior affects not only the children and youth who are bullied, who bully, and who are both bullied and bully others but also bystanders to bullying incidents. Given the myriad situations in which bullying can occur and the many people who may be involved, identifying effective prevention programs and policies is challenging, and it is unlikely that any one approach will be ap-

propriate in all situations. Commonly used bullying prevention approaches include policies regarding acceptable behavior in schools and behavioral interventions to promote positive cultural norms.

STUDY CHARGE

Recognizing that bullying behavior is a major public health problem that demands the concerted and coordinated time and attention of parents, educators and school administrators, health care providers, policy makers, families, and others concerned with the care of children, a group of federal agencies and private foundations asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to undertake a study of what is known and what needs to be known to further the field of preventing bullying behavior. The Committee on the Biological and Psychosocial Effects of Peer Victimization:

Lessons for Bullying Prevention was created to carry out this task under the Academies’ Board on Children, Youth, and Families and the Committee on Law and Justice. The study received financial support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Highmark Foundation, the National Institute of Justice, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Semi J. and Ruth W. Begun Foundation, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The full statement of task for the committee is presented in Box 1-1 .

Although the committee acknowledges the importance of this topic as it pertains to all children in the United States and in U.S. territories, this report focuses on the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Also, while the committee acknowledges that bullying behavior occurs in the school

environment for youth in foster care, in juvenile justice facilities, and in other residential treatment facilities, this report does not address bullying behavior in those environments because it is beyond the study charge.

CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY

This section of the report highlights relevant work in the field and, later in the chapter under “The Committee’s Approach,” presents the conceptual framework and corresponding definitions of terms that the committee has adopted.

Historical Context

Bullying behavior was first characterized in the scientific literature as part of the childhood experience more than 100 years ago in “Teasing and Bullying,” published in the Pedagogical Seminary ( Burk, 1897 ). The author described bullying behavior, attempted to delineate causes and cures for the tormenting of others, and called for additional research ( Koo, 2007 ). Nearly a century later, Dan Olweus, a Swedish research professor of psychology in Norway, conducted an intensive study on bullying ( Olweus, 1978 ). The efforts of Olweus brought awareness to the issue and motivated other professionals to conduct their own research, thereby expanding and contributing to knowledge of bullying behavior. Since Olweus’s early work, research on bullying has steadily increased (see Farrington and Ttofi, 2009 ; Hymel and Swearer, 2015 ).

Over the past few decades, venues where bullying behavior occurs have expanded with the advent of the Internet, chat rooms, instant messaging, social media, and other forms of digital electronic communication. These modes of communication have provided a new communal avenue for bullying. While the media reports linking bullying to suicide suggest a causal relationship, the available research suggests that there are often multiple factors that contribute to a youth’s suicide-related ideology and behavior. Several studies, however, have demonstrated an association between bullying involvement and suicide-related ideology and behavior (see, e.g., Holt et al., 2015 ; Kim and Leventhal, 2008 ; Sourander, 2010 ; van Geel et al., 2014 ).

In 2013, the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requested that the Institute of Medicine 1 and the National Research Council convene an ad hoc planning committee to plan and conduct a 2-day public workshop to highlight relevant information and knowledge that could inform a multidisciplinary

___________________

1 Prior to 2015, the National Academy of Medicine was known as the Institute of Medicine.

road map on next steps for the field of bullying prevention. Content areas that were explored during the April 2014 workshop included the identification of conceptual models and interventions that have proven effective in decreasing bullying and the antecedents to bullying while increasing protective factors that mitigate the negative health impact of bullying. The discussions highlighted the need for a better understanding of the effectiveness of program interventions in realistic settings; the importance of understanding what works for whom and under what circumstances, as well as the influence of different mediators (i.e., what accounts for associations between variables) and moderators (i.e., what affects the direction or strength of associations between variables) in bullying prevention efforts; and the need for coordination among agencies to prevent and respond to bullying. The workshop summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c ) informs this committee’s work.

Federal Efforts to Address Bullying and Related Topics

Currently, there is no comprehensive federal statute that explicitly prohibits bullying among children and adolescents, including cyberbullying. However, in the wake of the growing concerns surrounding the implications of bullying, several federal initiatives do address bullying among children and adolescents, and although some of them do not primarily focus on bullying, they permit some funds to be used for bullying prevention purposes.

The earliest federal initiative was in 1999, when three agencies collaborated to establish the Safe Schools/Healthy Students initiative in response to a series of deadly school shootings in the late 1990s. The program is administered by the U.S. Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, and Justice to prevent youth violence and promote the healthy development of youth. It is jointly funded by the Department of Education and by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The program has provided grantees with both the opportunity to benefit from collaboration and the tools to sustain it through deliberate planning, more cost-effective service delivery, and a broader funding base ( Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015 ).

The next major effort was in 2010, when the Department of Education awarded $38.8 million in grants under the Safe and Supportive Schools (S3) Program to 11 states to support statewide measurement of conditions for learning and targeted programmatic interventions to improve conditions for learning, in order to help schools improve safety and reduce substance use. The S3 Program was administered by the Safe and Supportive Schools Group, which also administered the Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act State and Local Grants Program, authorized by the

1994 Elementary and Secondary Education Act. 2 It was one of several programs related to developing and maintaining safe, disciplined, and drug-free schools. In addition to the S3 grants program, the group administered a number of interagency agreements with a focus on (but not limited to) bullying, school recovery research, data collection, and drug and violence prevention activities ( U.S. Department of Education, 2015 ).

A collaborative effort among the U.S. Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Education, Health and Human Services, Interior, and Justice; the Federal Trade Commission; and the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders created the Federal Partners in Bullying Prevention (FPBP) Steering Committee. Led by the U.S. Department of Education, the FPBP works to coordinate policy, research, and communications on bullying topics. The FPBP Website provides extensive resources on bullying behavior, including information on what bullying is, its risk factors, its warning signs, and its effects. 3 The FPBP Steering Committee also plans to provide details on how to get help for those who have been bullied. It also was involved in creating the “Be More than a Bystander” Public Service Announcement campaign with the Ad Council to engage students in bullying prevention. To improve school climate and reduce rates of bullying nationwide, FPBP has sponsored four bullying prevention summits attended by education practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and federal officials.

In 2014, the National Institute of Justice—the scientific research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice—launched the Comprehensive School Safety Initiative with a congressional appropriation of $75 million. The funds are to be used for rigorous research to produce practical knowledge that can improve the safety of schools and students, including bullying prevention. The initiative is carried out through partnerships among researchers, educators, and other stakeholders, including law enforcement, behavioral and mental health professionals, courts, and other justice system professionals ( National Institute of Justice, 2015 ).

In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act was signed by President Obama, reauthorizing the 50-year-old Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which is committed to providing equal opportunities for all students. Although bullying is neither defined nor prohibited in this act, it is explicitly mentioned in regard to applicability of safe school funding, which it had not been in previous iterations of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

The above are examples of federal initiatives aimed at promoting the

2 The Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act was included as Title IV, Part A, of the 1994 Elementary and Secondary Education Act. See http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/gun_violence/sect08-i.html [October 2015].

3 For details, see http://www.stopbullying.gov/ [October 2015].

healthy development of youth, improving the safety of schools and students, and reducing rates of bullying behavior. There are several other federal initiatives that address student bullying directly or allow funds to be used for bullying prevention activities.

Definitional Context

The terms “bullying,” “harassment,” and “peer victimization” have been used in the scientific literature to refer to behavior that is aggressive, is carried out repeatedly and over time, and occurs in an interpersonal relationship where a power imbalance exists ( Eisenberg and Aalsma, 2005 ). Although some of these terms have been used interchangeably in the literature, peer victimization is targeted aggressive behavior of one child against another that causes physical, emotional, social, or psychological harm. While conflict and bullying among siblings are important in their own right ( Tanrikulu and Campbell, 2015 ), this area falls outside of the scope of the committee’s charge. Sibling conflict and aggression falls under the broader concept of interpersonal aggression, which includes dating violence, sexual assault, and sibling violence, in addition to bullying as defined for this report. Olweus (1993) noted that bullying, unlike other forms of peer victimization where the children involved are equally matched, involves a power imbalance between the perpetrator and the target, where the target has difficulty defending him or herself and feels helpless against the aggressor. This power imbalance is typically considered a defining feature of bullying, which distinguishes this particular form of aggression from other forms, and is typically repeated in multiple bullying incidents involving the same individuals over time ( Olweus, 1993 ).

Bullying and violence are subcategories of aggressive behavior that overlap ( Olweus, 1996 ). There are situations in which violence is used in the context of bullying. However, not all forms of bullying (e.g., rumor spreading) involve violent behavior. The committee also acknowledges that perspective about intentions can matter and that in many situations, there may be at least two plausible perceptions involved in the bullying behavior.

A number of factors may influence one’s perception of the term “bullying” ( Smith and Monks, 2008 ). Children and adolescents’ understanding of the term “bullying” may be subject to cultural interpretations or translations of the term ( Hopkins et al., 2013 ). Studies have also shown that influences on children’s understanding of bullying include the child’s experiences as he or she matures and whether the child witnesses the bullying behavior of others ( Hellström et al., 2015 ; Monks and Smith, 2006 ; Smith and Monks, 2008 ).

In 2010, the FPBP Steering Committee convened its first summit, which brought together more than 150 nonprofit and corporate leaders,

researchers, practitioners, parents, and youths to identify challenges in bullying prevention. Discussions at the summit revealed inconsistencies in the definition of bullying behavior and the need to create a uniform definition of bullying. Subsequently, a review of the 2011 CDC publication of assessment tools used to measure bullying among youth ( Hamburger et al., 2011 ) revealed inconsistent definitions of bullying and diverse measurement strategies. Those inconsistencies and diverse measurements make it difficult to compare the prevalence of bullying across studies ( Vivolo et al., 2011 ) and complicate the task of distinguishing bullying from other types of aggression between youths. A uniform definition can support the consistent tracking of bullying behavior over time, facilitate the comparison of bullying prevalence rates and associated risk and protective factors across different data collection systems, and enable the collection of comparable information on the performance of bullying intervention and prevention programs across contexts ( Gladden et al., 2014 ). The CDC and U.S. Department of Education collaborated on the creation of the following uniform definition of bullying (quoted in Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ):

Bullying is any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm.

This report noted that the definition includes school-age individuals ages 5-18 and explicitly excludes sibling violence and violence that occurs in the context of a dating or intimate relationship ( Gladden et al., 2014 ). This definition also highlighted that there are direct and indirect modes of bullying, as well as different types of bullying. Direct bullying involves “aggressive behavior(s) that occur in the presence of the targeted youth”; indirect bullying includes “aggressive behavior(s) that are not directly communicated to the targeted youth” ( Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ). The direct forms of violence (e.g., sibling violence, teen dating violence, intimate partner violence) can include aggression that is physical, sexual, or psychological, but the context and uniquely dynamic nature of the relationship between the target and the perpetrator in which these acts occur is different from that of peer bullying. Examples of direct bullying include pushing, hitting, verbal taunting, or direct written communication. A common form of indirect bullying is spreading rumors. Four different types of bullying are commonly identified—physical, verbal, relational, and damage to property. Some observational studies have shown that the different forms of bullying that youths commonly experience may overlap ( Bradshaw et al., 2015 ;

Godleski et al., 2015 ). The four types of bullying are defined as follows ( Gladden et al., 2014 ):

- Physical bullying involves the use of physical force (e.g., shoving, hitting, spitting, pushing, and tripping).

- Verbal bullying involves oral or written communication that causes harm (e.g., taunting, name calling, offensive notes or hand gestures, verbal threats).

- Relational bullying is behavior “designed to harm the reputation and relationships of the targeted youth (e.g., social isolation, rumor spreading, posting derogatory comments or pictures online).”

- Damage to property is “theft, alteration, or damaging of the target youth’s property by the perpetrator to cause harm.”

In recent years, a new form of aggression or bullying has emerged, labeled “cyberbullying,” in which the aggression occurs through modern technological devices, specifically mobile phones or the Internet ( Slonje and Smith, 2008 ). Cyberbullying may take the form of mean or nasty messages or comments, rumor spreading through posts or creation of groups, and exclusion by groups of peers online.

While the CDC definition identifies bullying that occurs using technology as electronic bullying and views that as a context or location where bullying occurs, one of the major challenges in the field is how to conceptualize and define cyberbullying ( Tokunaga, 2010 ). The extent to which the CDC definition can be applied to cyberbullying is unclear, particularly with respect to several key concepts within the CDC definition. First, whether determination of an interaction as “wanted” or “unwanted” or whether communication was intended to be harmful can be challenging to assess in the absence of important in-person socioemotional cues (e.g., vocal tone, facial expressions). Second, assessing “repetition” is challenging in that a single harmful act on the Internet has the potential to be shared or viewed multiple times ( Sticca and Perren, 2013 ). Third, cyberbullying can involve a less powerful peer using technological tools to bully a peer who is perceived to have more power. In this manner, technology may provide the tools that create a power imbalance, in contrast to traditional bullying, which typically involves an existing power imbalance.

A study that used focus groups with college students to discuss whether the CDC definition applied to cyberbullying found that students were wary of applying the definition due to their perception that cyberbullying often involves less emphasis on aggression, intention, and repetition than other forms of bullying ( Kota et al., 2014 ). Many researchers have responded to this lack of conceptual and definitional clarity by creating their own measures to assess cyberbullying. It is noteworthy that very few of these

definitions and measures include the components of traditional bullying—i.e., repetition, power imbalance, and intent ( Berne et al., 2013 ). A more recent study argues that the term “cyberbullying” should be reserved for incidents that involve key aspects of bullying such as repetition and differential power ( Ybarra et al., 2014 ).

Although the formulation of a uniform definition of bullying appears to be a step in the right direction for the field of bullying prevention, there are some limitations of the CDC definition. For example, some researchers find the focus on school-age youth as well as the repeated nature of bullying to be rather limiting; similarly the exclusion of bullying in the context of sibling relationships or dating relationships may preclude full appreciation of the range of aggressive behaviors that may co-occur with or constitute bullying behavior. As noted above, other researchers have raised concerns about whether cyberbullying should be considered a particular form or mode under the broader heading of bullying as suggested in the CDC definition, or whether a separate defintion is needed. Furthermore, the measurement of bullying prevalence using such a definiton of bullying is rather complex and does not lend itself well to large-scale survey research. The CDC definition was intended to inform public health surveillance efforts, rather than to serve as a definition for policy. However, increased alignment between bullying definitions used by policy makers and researchers would greatly advance the field. Much of the extant research on bullying has not applied a consistent definition or one that aligns with the CDC definition. As a result of these and other challenges to the CDC definition, thus far there has been inconsistent adoption of this particular definition by researchers, practitioners, or policy makers; however, as the definition was created in 2014, less than 2 years is not a sufficient amount of time to assess whether it has been successfully adopted or will be in the future.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

This report builds on the April 2014 workshop, summarized in Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c ). The committee’s work was accomplished over an 18-month period that began in October 2014, after the workshop was held and the formal summary of it had been released. The study committee members represented expertise in communication technology, criminology, developmental and clinical psychology, education, mental health, neurobiological development, pediatrics, public health, school administration, school district policy, and state law and policy. (See Appendix E for biographical sketches of the committee members and staff.) The committee met three times in person and conducted other meetings by teleconferences and electronic communication.

Information Gathering

The committee conducted an extensive review of the literature pertaining to peer victimization and bullying. In some instances, the committee drew upon the broader literature on aggression and violence. The review began with an English-language literature search of online databases, including ERIC, Google Scholar, Lexis Law Reviews Database, Medline, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and Web of Science, and was expanded as literature and resources from other countries were identified by committee members and project staff as relevant. The committee drew upon the early childhood literature since there is substantial evidence indicating that bullying involvement happens as early as preschool (see Vlachou et al., 2011 ). The committee also drew on the literature on late adolescence and looked at related areas of research such as maltreatment for insights into this emerging field.

The committee used a variety of sources to supplement its review of the literature. The committee held two public information-gathering sessions, one with the study sponsors and the second with experts on the neurobiology of bullying; bullying as a group phenomenon and the role of bystanders; the role of media in bullying prevention; and the intersection of social science, the law, and bullying and peer victimization. See Appendix A for the agendas for these two sessions. To explore different facets of bullying and give perspectives from the field, a subgroup of the committee and study staff also conducted a site visit to a northeastern city, where they convened four stakeholder groups comprised, respectively, of local practitioners, school personnel, private foundation representatives, and young adults. The site visit provided the committee with an opportunity for place-based learning about bullying prevention programs and best practices. Each focus group was transcribed and summarized thematically in accordance with this report’s chapter considerations. Themes related to the chapters are displayed throughout the report in boxes titled “Perspectives from the Field”; these boxes reflect responses synthesized from all four focus groups. See Appendix B for the site visit’s agenda and for summaries of the focus groups.

The committee also benefited from earlier reports by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine through its Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education and the Institute of Medicine, most notably:

- Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research ( Institute of Medicine, 1994 )

- Community Programs to Promote Youth Development ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2002 )

- Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2003 )

- Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009 )

- The Science of Adolescent Risk-Taking: Workshop Report ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2011 )

- Communications and Technology for Violence Prevention: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2012 )

- Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014c )

- The Evidence for Violence Prevention across the Lifespan and Around the World: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014a )

- Strategies for Scaling Effective Family-Focused Preventive Interventions to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health: Workshop Summary ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014b )

- Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults ( Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015 )

Although these past reports and workshop summaries address various forms of violence and victimization, this report is the first consensus study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on the state of the science on the biological and psychosocial consequences of bullying and the risk and protective factors that either increase or decrease bullying behavior and its consequences.

Terminology

Given the variable use of the terms “bullying” and “peer victimization” in both the research-based and practice-based literature, the committee chose to use the current CDC definition quoted above ( Gladden et al., 2014, p. 7 ). While the committee determined that this was the best definition to use, it acknowledges that this definition is not necessarily the most user-friendly definition for students and has the potential to cause problems for students reporting bullying. Not only does this definition provide detail on the common elements of bullying behavior but it also was developed with input from a panel of researchers and practitioners. The committee also followed the CDC in focusing primarily on individuals between the ages of 5 and 18. The committee recognizes that children’s development occurs on a continuum, and so while it relied primarily on the CDC defini-

tion, its work and this report acknowledge the importance of addressing bullying in both early childhood and emerging adulthood. For purposes of this report, the committee used the terms “early childhood” to refer to ages 1-4, “middle childhood” for ages 5 to 10, “early adolescence” for ages 11-14, “middle adolescence” for ages 15-17, and “late adolescence” for ages 18-21. This terminology and the associated age ranges are consistent with the Bright Futures and American Academy of Pediatrics definition of the stages of development. 4

A given instance of bullying behavior involves at least two unequal roles: one or more individuals who perpetrate the behavior (the perpetrator in this instance) and at least one individual who is bullied (the target in this instance). To avoid labeling and potentially further stigmatizing individuals with the terms “bully” and “victim,” which are sometimes viewed as traits of persons rather than role descriptions in a particular instance of behavior, the committee decided to use “individual who is bullied” to refer to the target of a bullying instance or pattern and “individual who bullies” to refer to the perpetrator of a bullying instance or pattern. Thus, “individual who is bullied and bullies others” can refer to one who is either perpetrating a bullying behavior or a target of bullying behavior, depending on the incident. This terminology is consistent with the approach used by the FPBP (see above). Also, bullying is a dynamic social interaction ( Espelage and Swearer, 2003 ) where individuals can play different roles in bullying interactions based on both individual and contextual factors.

The committee used “cyberbullying” to refer to bullying that takes place using technology or digital electronic means. “Digital electronic forms of contact” comprise a broad category that may include e-mail, blogs, social networking Websites, online games, chat rooms, forums, instant messaging, Skype, text messaging, and mobile phone pictures. The committee uses the term “traditional bullying” to refer to bullying behavior that is not cyberbullying (to aid in comparisons), recognizing that the term has been used at times in slightly different senses in the literature.

Where accurate reporting of study findings requires use of the above terms but with senses different from those specified here, the committee has noted the sense in which the source used the term. Similarly, accurate reporting has at times required use of terms such as “victimization” or “victim” that the committee has chosen to avoid in its own statements.

4 For details on these stages of adolescence, see https://brightfutures.aap.org/Bright%20Futures%20Documents/3-Promoting_Child_Development.pdf [October 2015].

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into seven chapters. After this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 provides a broad overview of the scope of the problem.

Chapter 3 focuses on the conceptual frameworks for the study and the developmental trajectory of the child who is bullied, the child who bullies, and the child who is bullied and also bullies. It explores processes that can explain heterogeneity in bullying outcomes by focusing on contextual processes that moderate the effect of individual characteristics on bullying behavior.

Chapter 4 discusses the cyclical nature of bullying and the consequences of bullying behavior. It summarizes what is known about the psychosocial, physical health, neurobiological, academic-performance, and population-level consequences of bullying.

Chapter 5 provides an overview of the landscape in bullying prevention programming. This chapter describes in detail the context for preventive interventions and the specific actions that various stakeholders can take to achieve a coordinated response to bullying behavior. The chapter uses the Institute of Medicine’s multi-tiered framework ( National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009 ) to present the different levels of approaches to preventing bullying behavior.

Chapter 6 reviews what is known about federal, state, and local laws and policies and their impact on bullying.

After a critical review of the relevant research and practice-based literatures, Chapter 7 discusses the committee conclusions and recommendations and provides a path forward for bullying prevention.

The report includes a number of appendixes. Appendix A includes meeting agendas of the committee’s public information-gathering meetings. Appendix B includes the agenda and summaries of the site visit. Appendix C includes summaries of bullying prevalence data from the national surveys discussed in Chapter 2 . Appendix D provides a list of selected federal resources on bullying for parents and teachers. Appendix E provides biographical sketches of the committee members and project staff.

Berne, S., Frisén, A., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Naruskov, K., Luik, P., Katzer, C., Erentaite, R., and Zukauskiene, R. (2013). Cyberbullying assessment instruments: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18 (2), 320-334.

Bradshaw, C.P., Waasdorp, T.E., and Johnson, S.L. (2015). Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: Influence of school context. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44 (3), 494-508.

Burk, F.L. (1897). Teasing and bullying. The Pedagogical Seminary, 4 (3), 336-371.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O.R., and Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe.

Eisenberg, M.E., and Aalsma, M.C. (2005). Bullying and peer victimization: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36 (1), 88-91.

Espelage, D.L., and Swearer, S.M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32 (3), 365-383.

Farrington, D., and Ttofi, M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 5 (6).

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R.K., and Turner, H.A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect , 31 (1), 7-26.

Gladden, R.M., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Hamburger, M.E., and Lumpkin, C.D. (2014). Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0 . Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education.

Godleski, S.A., Kamper, K.E., Ostrov, J.M., Hart, E.J., and Blakely-McClure, S.J. (2015). Peer victimization and peer rejection during early childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44 (3), 380-392.

Hamburger, M.E., Basile, K.C., and Vivolo, A.M. (2011). Measuring Bullying Victimization, Perpetration, and Bystander Experiences: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Hellström, L., Persson, L., and Hagquist, C. (2015). Understanding and defining bullying—Adolescents’ own views. Archives of Public Health, 73 (4), 1-9.

Holt, M.K., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Polanin, J.R., Holland, K.M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J.L., Wolfe, M., and Reid, G. (2015). Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135 (2), e496-e509.

Hopkins, L., Taylor, L., Bowen, E., and Wood, C. (2013). A qualitative study investigating adolescents’ understanding of aggression, bullying and violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (4), 685-693.

Hymel, S., and Swearer, S.M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 293.

Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders. P.J. Mrazek and R.J. Haggerty, Editors. Division of Biobehavioral Sciences and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2011). The Science of Adolescent Risk-taking: Workshop Report . Committee on the Science of Adolescence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2012). Communications and Technology for Violence Prevention: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014a). The Evidence for Violence Prevention across the Lifespan and around the World: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014b). Strategies for Scaling Effective Family-Focused Preventive Interventions to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2014c). Building Capacity to Reduce Bullying: Workshop Summary . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2015). Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kim, Y.S., and Leventhal, B. (2008). Bullying and suicide. A review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20 (2), 133-154.

Koo, H. (2007). A time line of the evolution of school bullying in differing social contexts. Asia Pacific Education Review, 8 (1), 107-116.

Kota, R., Schoohs, S., Benson, M., and Moreno, M.A. (2014). Characterizing cyberbullying among college students: Hacking, dirty laundry, and mocking. Societies, 4 (4), 549-560.

McDougall, P., and Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70 (4), 300.

Monks, C.P., and Smith, P.K. (2006). Definitions of bullying: Age differences in understanding of the term and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24 (4), 801-821.

National Institute of Justice. (2015). Comprehensive School Safety Initiative. 2015. Available: http://nij.gov/topics/crime/school-crime/Pages/school-safety-initiative.aspx#about [October 2015].

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community Programs to Promote Youth Development . Committee on Community-Level Programs for Youth. J. Eccles and J.A. Gootman, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2003). Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence . Case Studies of School Violence Committee. M.H. Moore, C.V. Petrie, A.A. Barga, and B.L. McLaughlin, Editors. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. M.E. O’Connell, T. Boat, and K.E. Warner, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School. What We Know and Whal We Can Do. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1996). Bully/victim problems in school. Prospects, 26 (2), 331-359.

Slonje, R., and Smith, P.K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49 (2), 147-154.

Smith, P. ., and Monks, C. . (2008). Concepts of bullying: Developmental and cultural aspects. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20 (2), 101-112.

Sourander, A. (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55 (5), 282.

Sticca, F., and Perren, S. (2013). Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42 (5), 739-750.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Safe Schools/Healthy Students. 2015. Available: http://www.samhsa.gov/safe-schools-healthy-students/about [November 2015].

Tanrikulu, I., and Campbell, M. (2015). Correlates of traditional bullying and cyberbullying perpetration among Australian students. Children and Youth Services Review , 55 , 138-146.

Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (3), 277-287.

U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Safe and Supportive Schools . Available: http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-awards-388-million-safe-and-supportive-school-grants [October 2015].

Vaillancourt, T., Trinh, V., McDougall, P., Duku, E., Cunningham, L., Cunningham, C., Hymel, S., and Short, K. (2010). Optimizing population screening of bullying in school-aged children. Journal of School Violence, 9 (3), 233-250.

van Geel, M., Vedder, P., and Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. Pediatrics, 168 (5), 435-442.

Vivolo, A.M., Holt, M.K., and Massetti, G.M. (2011). Individual and contextual factors for bullying and peer victimization: Implications for prevention. Journal of School Violence, 10 (2), 201-212.

Vlachou, M., Andreou, E., Botsoglou, K., and Didaskalou, E. (2011). Bully/victim problems among preschool children: A review of current research evidence. Educational Psychology Review, 23 (3), 329-358.

Wolke, D., and Lereya, S.T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100 (9), 879-885.

Ybarra, M.L., Espelage, D.L., and Mitchell, K.J. (2014). Differentiating youth who are bullied from other victims of peer-aggression: The importance of differential power and repetition. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55 (2), 293-300.

This page intentionally left blank.

Bullying has long been tolerated as a rite of passage among children and adolescents. There is an implication that individuals who are bullied must have "asked for" this type of treatment, or deserved it. Sometimes, even the child who is bullied begins to internalize this idea. For many years, there has been a general acceptance and collective shrug when it comes to a child or adolescent with greater social capital or power pushing around a child perceived as subordinate. But bullying is not developmentally appropriate; it should not be considered a normal part of the typical social grouping that occurs throughout a child's life.

Although bullying behavior endures through generations, the milieu is changing. Historically, bulling has occurred at school, the physical setting in which most of childhood is centered and the primary source for peer group formation. In recent years, however, the physical setting is not the only place bullying is occurring. Technology allows for an entirely new type of digital electronic aggression, cyberbullying, which takes place through chat rooms, instant messaging, social media, and other forms of digital electronic communication.

Composition of peer groups, shifting demographics, changing societal norms, and modern technology are contextual factors that must be considered to understand and effectively react to bullying in the United States. Youth are embedded in multiple contexts and each of these contexts interacts with individual characteristics of youth in ways that either exacerbate or attenuate the association between these individual characteristics and bullying perpetration or victimization. Recognizing that bullying behavior is a major public health problem that demands the concerted and coordinated time and attention of parents, educators and school administrators, health care providers, policy makers, families, and others concerned with the care of children, this report evaluates the state of the science on biological and psychosocial consequences of peer victimization and the risk and protective factors that either increase or decrease peer victimization behavior and consequences.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Advertisement

Open Science: Recommendations for Research on School Bullying

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 30 June 2022

- Volume 5 , pages 319–330, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Nathalie Noret ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4393-1887 1 ,

- Simon C. Hunter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3922-1252 2 , 3 ,

- Sofia Pimenta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9680-514X 4 ,

- Rachel Taylor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1803-1449 4 &

- Rebecca Johnson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7359-6595 2

3298 Accesses

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The open science movement has developed out of growing concerns over the scientific standard of published academic research and a perception that science is in crisis (the “replication crisis”). Bullying research sits within this scientific family and without taking a full part in discussions risks falling behind. Open science practices can inform and support a range of research goals while increasing the transparency and trustworthiness of the research process. In this paper, we aim to explain the relevance of open science for bullying research and discuss some of the questionable research practices which challenge the replicability and integrity of research. We also consider how open science practices can be of benefit to research on school bullying. In doing so, we discuss how open science practices, such as pre-registration, can benefit a range of methodologies including quantitative and qualitative research and studies employing a participatory research methods approach. To support researchers in adopting more open practices, we also highlight a range of relevant resources and set out a series of recommendations to the bullying research community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Q Methodology as an Innovative Addition to Bullying Researchers’ Methodological Repertoire

The Importance of Being Attentive to Social Processes in School Bullying Research: Adopting a Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach

Pseudoscience, an Emerging Field, or Just a Framework Without Outcomes? A Bibliometric Analysis and Case Study Presentation of Social Justice Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

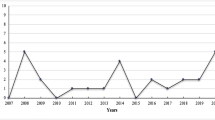

Bullying in school is a common experience for many children and adolescents. Such experiences relate to a range of adverse outcomes, including poor mental health, poorer academic achievement, and anti-social behaviour (Gini et al., 2018 ; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010 ; Valdebenito et al., 2017 ). Bullying research has increased substantially over the past 60 years, with over 5000 articles published between 2010 and 2016 alone (Volk et al., 2017 ). Much of this research focuses on the prevalence and antecedents of bullying, correlates of bullying, and the development and evaluation of anti-bullying interventions (Volk et al., 2017 ). The outcomes of this work for children and young people can therefore be life changing, and researchers should strive to ensure that their work is trustworthy, reliable, and accessible to a wide range of stakeholders both inside and outside of academia.

In recent years, the replication crisis has led to growing concern regarding the standard of research practices in the social sciences (Munafò et al., 2017 ). To address this, open science practices, such as openly sharing publications and data, conducting replication studies, and the pre-registration of research protocols, have provided the opportunity to increase the transparency and trustworthiness of the research process. In this paper, we aim to discuss the replication crisis and highlight the risks that questionable research practices pose for bullying research. We also aim to summarise open science practices and outline how these can benefit the broad spectrum of bullying research as well as to researchers themselves. Specifically, we aim to highlight how such practices can benefit both quantitative and qualitative research and studies employing a participatory research methods approach.

The Replication Crisis

In 2015, the Open Science Collaboration (Open Science Collaboration, 2015 ) conducted a large-scale replication of 100 published studies from three journals. The results questioned the replicability of research findings in psychology. In the original 100 studies, 97 reported a significant effect compared to only 35 of the replications. Furthermore, the effect sizes reported in the original studies were typically much larger than those found in the replications. The findings of the Open Science Collaboration received significant academic and mainstream media attention, which concluded that psychological research is in crisis (Wiggins & Chrisopherson, 2019 ). While these findings are based on the analysis of psychological research, challenges in replicating research findings have been reported in a range of disciplines including sociology (Freese & Peterson, 2017 ) and education studies (Makel & Pluker, 2014 ). Shrout and Rodgers ( 2018 ) suggest that the notion that science is in crisis is further supported by (1) the number of serious cases of academic misconduct such as that of Diederick Stapel (Nelson et al., 2018 ) and (2) the prevalence of questionable research practices and misuse of inferential statistics and hypothesis testing (see Ioannidis, 2005 ). The replication crisis has called into question the degree to which research across the social sciences accurately describes the world that we live in or whether this literature is overwhelmingly populated by misleading claims based on weak and error-strewn findings.

The trustworthiness of research reflects the quality of the method, rigour of the design, and the extent to which results are reliable and valid (Cook et al., 2018 ). Research on school bullying has grown exponentially in recent years (Smith & Berkkun, 2020 ) and typically focuses on understanding the nature, prevalence, and consequences of bullying to inform prevention and intervention efforts. If our research is not trustworthy, this can impede theory development and call into question the reliability of our research and meta-analytic findings (Friese & Frankenbach, 2020 ). Ultimately, if our research findings are untrustworthy, this undermines our efforts to prevent bullying and help and support young people. Bullying research exists within a broader academic research culture, which facilitates and incentivises the ways that research is undertaken and shared. As such, the issues that have been identified have direct relevance to those working in bullying.

The Incentive Culture in Academia

“The relentless drive for research excellence has created a culture in modern science that cares exclusively about what is achieved and not about how it is achieved.”

Jeremy Farrar, Director of the Wellcome Trust (Farrar, 2019 ).

In academia, career progression is closely tied to publication record. As such, academics feel under considerable pressure to publish frequently in high-quality journals to advance their careers (Grimes et al., 2018 ; Munafò et al., 2017 ). Yet, the publication process itself is biased toward accepting novel or statistically significant findings for publication (Renkewitz & Heene, 2019 ). This bias fuels a perception that non-significant results will not be published (the “file drawer problem”: Rosenthal, 1979 ). This can result in researchers employing a range of questionable research practices to achieve a statistically significant finding in order to increase the likelihood that a study will be accepted for publication. Taken together, this can lead to a perverse “scientific process” where achieving statistical significance is more important than the quality of the research itself (Frankenhuis & Nettle, 2018 ).

Questionable Research Practices

Questionable research practices (QRPs) can occur at all stages of the research process (Munafò et al., 2017 ). These practices differ from research misconduct in that they do not typically involve the deliberate intent to deceive or engage in fraudulent research practices (Stricker & Günther, 2019 ). Instead, QRPs are characterised by misrepresentation, inaccuracy, and bias (Steneck, 2006 ). All are of direct relevance to the work of scholars in the bullying field since each weakens our ability to achieve meaningful change for children and young people. QRPs emerge directly from “researcher degrees of freedom” that occur at all stages of the research process and which simply reflect the many decisions that researchers make with regard to their hypotheses, methodological design, data analyses, and reporting of results (see Wicherts et al., 2016 for an extensive list of researcher degrees of freedom). These decisions pose fundamental threats to how robust a study is as each compromises the likelihood that findings accurately model a psychological or social process (Munafò et al., 2017 ). QRPs include p -hacking; hypothesising after the result is known (HARKing); conducting studies with low statistical power; and the misuse of p values (Chambers et al., 2014 ). Such QRPs may reflect a misunderstanding of inferential statistics (Sijtsma, 2016 ). A misunderstanding of statistical theory can also lead to a lack of awareness regarding the nature and impact of QRPs (Sijtsma, 2016 ). This includes the prevailing approach to quantitative data analysis, Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST) (Lyu et al., 2018 ; Travers et al., 2017 ), which is overwhelmingly the approach used in the bullying field. QRPs can fundamentally threaten the degree to which research in bullying can be trusted, replicated, and effective in efforts to implement successful and impactful intervention or prevention programs.

P -hacking (or data-dredging) reflects methods of re-analysing data in different ways to find a significant result (Raj et al., 2018 ). Such methods can include the selective deletion of outliers, selectively controlling for variables, recoding variables in different ways, or selectively reporting the results of structural equation models (Simonsohn et al., 2014 ). While there are various methods of p -hacking, the end goal is the same: to find a significant result in a data set, often when initial analyses fail to do so (Friese & Frankenbach, 2020 ).

There are no available data on the degree to which p -hacking is a problem in bullying research per se, but the nature of the methods commonly used mean it is a clear and present danger. For example, the inclusion of multiple outcome measures (allowing those with the “best” results to be cherry-picked for publication), measures of involvement in bullying that can be scored or analysed in multiple ways (e.g. as a continuous measure or as a method to categorise participants as involved or not), and the presence of a diverse selection of demographic variables (which can be selectively included or excluded from analyses) all provide researchers with an array of possible analytic approaches. Such options pose a risk for p -hacking as decisions can be made on the results of statistical fishing (i.e. hunting to find significant effects) rather than on any underpinning theoretical rationale.

P -hacking need not be driven by a desire to deceive; rather, it can be used by well-meaning researchers and their wish to honestly identify useful or interesting findings (Wicherts et al., 2016 ). Sadly, even in this case, the impact of p- hacking remains profoundly problematic for the field. The p- hacking process biases the literature towards erroneous significant results and inflated effect sizes, impacting on our understanding of any issue that we seek to understand better, and biasing effect size estimates reported in meta-analyses (Friese & Frankenbach, 2020 ). While such effects may seem remote or of only academic interest, they compromise all that we in the bullying field seek to accomplish because they make it much less likely that effective, impactful, and meaningful intervention and prevention strategies can be identified and implemented.

Typically, quantitative research follows the hypothetico-deductive model (Popper, 1959 ). From this perspective, hypotheses are formulated based on appropriate theory and previous research (Rubin, 2017 ). Once written, the study is designed, and data are collected and analysed (Rubin, 2017 ). Hypothesising after the result is known, or HARKing (Kerr, 1998 ), occurs when researchers amend their hypotheses to reflect their completed data analysis (Kerr, 1998 ). HARKing results in confusion between confirmatory and exploratory data analysis (Shrout & Rodgers, 2018 ), creating a literature where hypotheses are always confirmed and never falsified. This inhibits theory development (Rubin, 2017 ) in part because “progress” is, in fact, the accumulation of type 1 errors.

Low Statistical Power

Statistical power reflects the power in a statistical test to find an effect if there is one to find (Cohen, 2013 ). There are concerns regarding the sample sizes used in bullying research, as experiences of bullying are typically of a low frequency and positively skewed (Vessey et al., 2014 ; Volk et al., 2017 ). Low statistical power is problematic in two ways. First, it increases the type II error rate (the probability of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis), meaning that researchers may fail to report important and meaningful effects. Statistically significant effects can still be found under the conditions of low statistical power; however, the size of these effects is likely to be exaggerated due to a lower positive predictive value (the probability of a statistically significant result being genuine) (Button et al., 2013 ). In this case, researchers may find significant effects even in small samples, but those effects are at risk of being inflated.

QRPs in Qualitative Research

Apart from the previously discussed issues, there are also QRPs in qualitative work. Mainly, these involve issues pertaining to trustworthiness such as credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (See Shenton, 2004 ). One factor that can influence perceptions about qualitative work is the possibility of subjectivity or different interpretations of the same data (Haven & Van Grootel, 2019 ). Additionally, the idea that the researcher will be biased and that their experiences, beliefs, and personal history will all influence how they both collect and interpret data has also been discussed (Berger, 2015 ). Clearly stating the positionality of the researcher and how their experiences informed their current research (the process of reflexivity) can help others better understand their interpretation of the data (Berger, 2015 ). Finally, one decision that qualitative researchers should consider when thinking about their designs is their stopping criteria. This might imply code or meaning saturation (see Hennink et al., 2017 , for more detail on how these two types are different from one another). Thus, making it clear in the conceptualisation process when and how the data collection will stop is important to assure transparency and high-quality research. This is not a complete list of QRPs in qualitative research, but these seem to be the most urgent when it comes to bullying research when thinking about open science.

The Prevalence and Impact of QRPs

Identifying the prevalence of QRPs and academic misconduct is challenging as this is reliant on self-reports. In their survey of 2155 psychologists, John et al. ( 2012 ) identified that 78% of participants had not reported all dependent measures, 72% had collected more data after finding their statistical effects were not statistically significant, 67% reported selective reporting of studies that “worked” (yielded a significant effect), and 9% reported falsifying data. Such problematic practices have serious implications for the reliability of effects reported in the research literature (John et al., 2012 ), which can impact interventions and treatments such evidence may inform. Furthermore, De Vries et al. ( 2018 ) have highlighted how biases in the publication process threaten the validity of treatment results reported in the literature. Although focused on the treatment of depression, their work has clear lessons for the bullying research community. They demonstrate how the bias towards reporting more positive, significant effects, distorts a literature in favour of treatments that appear efficacious but are much less so in practice (Box 1 ).

Box 1 The Replication Crisis

Munafò et al. ( 2017 ) outline a manifesto for reproducible research, highlighting problems with current research practices.

Shrout and Rodgers ( 2018 ) provide an overview of the replication crisis and questionable research practices.

Steneck ( 2006 ) provides a detailed overview of definitions of academic misconduct, questionable research practices, and academic integrity.

Open Science

Confronting these challenges can be daunting, but open science offers several strategies that researchers in the bullying field can use to increase the transparency, reproducibility, and openness of their research. The most common practices include openly sharing publications and data, encouraging replication, pre-registration, and open peer-review. Below, we provide an overview of open science practices, with a particular focus on pre-registration and replication studies. We recommend that researchers begin by using those practices that they can most easily integrate into their work, building their repertoire of open science actions over time. We provide a series of recommendations for the school bullying research community alongside summaries of useful supporting resources (Box 2 ).

Box 2 Key Reading on Open Science

Banks et al. ( 2019 ) discuss frequently asked questions about open science providing a good overview of open science practices and contemporary debates.

Crüwell et al. ( 2019 ) provide an annotated reading list on important papers in open science.

Gehlbach and Robinson ( 2021 ) in their introduction to a special edition of the journal Educational Psychologist they discuss the adoption of open science practices in the context of what they term “old school” research practices.

Lindsay ( 2020 ) outlines a series of steps researchers can take to integrate open science practices into their research.

Open Publication, Open Data, and Reporting Standards

Open publication.

Ensuring research publications are openly available by providing access to pre-print versions of papers or paying for publishers to make articles openly available is now a widely adopted practice (Concannon et al., 2019 ; McKiernan et al., 2016 ). Articles can be hosted on websites such as ResearchGate and/or on institutional repositories, allowing a wider pool of potential stakeholders to access relevant bullying research and increasing the impact of research (Concannon et al., 2019 ). This process also supports access for the research and practice communities in low- and middle-income countries where even Universities may be unable to pay journal subscriptions. The authors can also share pre-print versions of their papers for comment and review before submitting them to a journal for review using an online digital repository, such as PsyArXiv. Sharing publications in this way can encourage both early feedback on articles and the faster dissemination of research findings (Chiarelli et al., 2019 ).

Making data and data analysis scripts openly available is also encouraged, can enable further data analysis (e.g. meta-analysis), and facilitates replication (Munafò et al., 2017 ; Nosek & Bar-Anan, 2012 ). It also enables the collation of larger data sets, and secondary data analyses to test different hypotheses. Several publications on bullying in school are based on the secondary analysis of openly shared data (e.g. Dantchev & Wolke, 2019 ; Przybylski & Bowes, 2017 ) and highlight the benefits of such analyses. Furthermore, although limited in number, examples of papers on school bullying where data, research materials, and data analysis scripts are openly shared are emerging (e.g. Przybylski, 2019 ).

Bullying data often includes detailed personal accounts of experiences and the impact of bullying. Such data are highly sensitive, and there may be a risk that individuals can be identified. To address such sensitivities, Meyer ( 2018 ) (see box 3 ) proposes a tiered approach to the consent process, where participants are actively involved in decisions around what parts of their data and where their data are shared. Meyer ( 2018 ) also highlights the importance of selecting the right repository for your data. Some repositories are entirely open, whereas others only provide access to suitably qualified researchers. While bullying data pose particular ethical challenges, the sharing of all data is encouraged (Bishop, 2009 ; McLeod & O’Connor, 2020 ).

Reporting Standards

Reporting standards are standards for reporting a research study and provide useful guidance on what methodological and analytical information should be included in a research paper (Munafò et al., 2017 ). Such guidelines aim to ensure sufficient information is provided to enable replication and promote transparency (Munafò et al., 2017 ). Journal publishers are now beginning to outline what open science practices should be reported in articles. For example, from July 2021, when submitting a paper for review in one of the American Psychological Association journals, the authors are now required to state whether their data will be openly shared and whether or not their study was pre-registered. In a bullying context, Smith and Berkkun ( 2020 ) have highlighted that important contextual data is often missing from publications and recommend, for example, that the gender and age of participants alongside the country and date of data collection should be included as standard in papers on bullying in school.

Recommendations:

Researchers to start to share all research materials openly using an online repository. Box 3 provides some useful guidance on how to support the open sharing of research materials.

Journal editors and publishers to further promote the open sharing of research material.

Researchers to follow the recommendations set out by Smith and Berkkun ( 2020 ) and follow a set of reporting standards when reporting bullying studies.

Reviewers be mindful of Smith and Berkkun ( 2020 ) recommendations when reviewing bullying papers.

Box 3 Useful Resources on Openly Sharing Research Materials & Reporting Standards

Banks et al. ( 2019 ) provide a helpful overview of open science practices, alongside a set of recommendations for ensuring research is more open.

Meyer ( 2018 ) provides some useful guidance on managing the ethical issues of openly sharing data.

The Equator Network ( https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/ ) is a useful resource for the sharing of different reporting standards, for example, the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and STROBE standards for observational studies.

The Foster website is an online e-learning portal with a wealth of resources to help researchers develop open science practices https://www.fosteropenscience.eu/ , including sharing resources and pre-prints.

The Open Science Framework has resources to support open science practices and to use their platform https://www.cos.io/products/osf .

Smith and Berkkun ( 2020 ) provide a review of contextual information reported in bullying research papers and offer recommendations on what information to include.

The PsyArXiv https://psyarxiv.com and SocArXiv https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv repositories accept pre-print publications in psychology and sociology.

Replication Studies

Replicated findings increase confidence in the reliability of that finding, ensuring research findings are robust and enabling science to self-correct (Cook et al., 2018 ; Drotar, 2010 ). Replication reflects the ability of a researcher to duplicate the results of a prior study with new data (Goodman et al., 2018 ). There are different forms of replication that can be broadly categorised into two: those that aim to recreate the exact conditions of an earlier study (exact/direct replication) and those that aim to test the same hypotheses again using a different method (conceptual replication) (Schmidt, 2009 ). Replication studies are considered fundamental in establishing whether study findings are consistent and trustworthy (Cook et al., 2018 ).

To date, few replication studies have been conducted on bullying in schools. A Web of Science search using the Boolean search term bully* alongside the search term “replication” identified two replication studies (Berdondini & Smith, 1996 ; Huitsing et al., 2020 ). Such a small number of replications may reflect concerns regarding the value of these and concerns about how to conduct such work when data collection is so time and resource-intensive. In addition, school gatekeepers are themselves interested in novelty and addressing their own problems and may be reluctant to participate in a study which has “already been done”. One possible solution to this challenge is to increase the number of large-scale collaborations among bullying researchers (e.g. multiple researchers across many sites collecting the same data). Munafò et al. ( 2017 ) highlight the benefits of collaboration and “team science” to build capacity in a research project. They argue that greater collaboration through team science would enable researchers to undertake higher-powered studies and relieve the pressure on single researchers. Such projects also have the benefit of increasing generalisability across settings and populations.

Undertake direct replications or, as a more manageable first step, include aspects of replication within larger studies.

Journal editors to actively promote the submission of replication studies on school bullying.

Journal editors, editorial panels, and reviewers to recognise the value of replication studies rather than favouring new or novel findings (Box 4 ).

Box 4 Useful Resources on Replication Studies

Brandt et al. ( 2014 ) provide a useful step by step guide on conducting replication studies, including a registration template form for pre-registering a replication study (available here: https://osf.io/4jd46/ ).

Coyne et al. ( 2016 ) discuss the benefits of replication to research in educational research (with a particular focus on special education).

Duncan et al. ( 2014 ) discuss the benefits of replication to research in developmental psychology.

Pre-Registration

Pre-registration requires researchers to set out, in advance of any data collection, their hypotheses, research design, and planned data analysis (van’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016 ). Pre-registering a study reduces the number of researcher degrees of freedom as all decisions are outlined at the start of a project. However, to date, there have been few pre-registered studies in bullying. There are two forms of pre-registration: the pre-registration of analysis plans and registered reports. In a pre-registered analysis plan, the hypotheses, research design, and analysis plan are registered in advance. These plans are then stored in an online repository (e.g. the Open Science Framework (OSF) or AsPredicted website), which is then time-stamped as a record of the planned research project (van’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016 ). Registered reports, however, integrate the pre-registration of methods and analyses into the publication process (Chambers et al., 2014 ). With a registered report, researchers can submit their introduction and proposed methods and analyses to a journal for peer review. This creates a two-tier peer-review process, where the registered reports can be accepted in principle or rejected in the first stage of review, based on the rigour of the proposed methods and analysis plans rather than on the findings of the study (Hardwicke & Ioannidis, 2018 ). In the second stage of the review process, the authors then submit the complete paper (at a later date after data have been collected and analyses completed), and this is also reviewed. The decision to accept a study is therefore explicitly based on the quality of the research process rather than the outcome (Frankenhuis & Nettle, 2018 ) and in practice, almost no work is ever rejected following an in-principal acceptance at stage 1 (C. Chambers, personal communication, December 11, 2020). At the time of writing, over 270 journals accept registered reports, many of which are directly relevant to bullying researchers (e.g. Developmental Science, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Journal of Educational Psychology).

Pre-registration offers one approach for improving the validity of bullying research. Employing greater use of pre-registration would complement other recommendations on how to improve research practices in bullying research. For example, Volk et al. ( 2017 ) propose a “bullying research checklist” (see Box 5 ).

Box 5 Volk et al. ( 2017 ) Bullying Research Checklist ( reproduced with permission )

State and justify your chosen definition of bullying.

Outline the theoretical logic underlying your hypotheses and how it pertains to your chosen definition and program of research/intervention.

Use one's logic model and theoretical predictions to determine which kind of measurements are most appropriate for testing one's hypotheses. There is no gold standard measure of bullying, but be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of the different types of measures. Where possible, use complementary forms of measurement and reporters to offset any weaknesses.

Implement an appropriate research or intervention design (longitudinal if possible) and recruit an appropriate sample.

Reflect upon the final product, its associations with the chosen logic model and theory, and explicitly discuss important pertinent limitations with a particular emphasis on issues concerning the theoretical validity of one's findings.

Volk et al.’s ( 2017 ) checklist highlights the importance of setting out in advance the definition of bullying, alongside the theoretical underpinnings for the hypotheses.

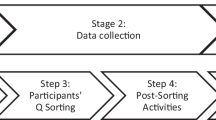

Pre-Registering Quantitative Studies

The pre-registration of quantitative studies requires researchers to state the hypotheses, method, and planned data analysis in advance of any data collection (van’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016 ). When outlining the hypotheses being tested, researchers are required to outline the background and theoretical underpinning of the study. This reflects the importance of theoretically led hypotheses (van’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016 ), which are more appropriately tested using NHST and inferential statistics in a confirmatory rather than exploratory design (Wagenmakers et al., 2012 ). Requiring researchers to state their hypotheses in advance of any data collection adheres to the confirmatory nature of inferential statistics and reduces the risk of HARKing (van’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016 ). Following a description of the hypotheses, researchers outline the details of the planned method, including the design of the study, the sample, the materials and measures, and the procedure. Information on the nature of the study and how materials and measures will be used and scored are outlined in full. Researchers are required to provide a justification for and an indication of the desired sample size.