Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 24 September 2018

Making gender diversity work for scientific discovery and innovation

- Mathias Wullum Nielsen 1 ,

- Carter Walter Bloch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4718-003X 1 &

- Londa Schiebinger 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 2 , pages 726–734 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

5869 Accesses

132 Citations

175 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Decision making

- Interdisciplinary studies

Gender diversity has the potential to drive scientific discovery and innovation. Here, we distinguish three approaches to gender diversity: diversity in research teams, diversity in research methods and diversity in research questions. While gender diversity is commonly understood to refer only to the gender composition of research teams, fully realizing the potential of diversity for science and innovation also requires attention to the methods employed and questions raised in scientific knowledge-making. We provide a framework for understanding the best ways to support the three approaches to gender diversity across four interdependent domains — from research teams to the broader disciplines in which they are embedded to research organizations and ultimately to the different societies that shape them through specific gender norms and policies. Our analysis demonstrates that realizing the benefits of diversity for science requires careful management of these four interdependent domains.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of gender diversity on scientific research teams: a need to broaden and accelerate future research

Hannah B. Love, Alyssa Stephens, … Ellen R. Fisher

Gender and Arctic climate change science in Canada

David Natcher, Ana Maria Bogdan, … Kent Spiers

Collaboration between women helps close the gender gap in ice core science

Bess G. Koffman, Matthew B. Osman, … Sofia Guest

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Reinforced European Research Area Partnership for Excellence and Growth (European Commission, 2012).

S tatement of Principles and Actions Promoting the Equality and Status of Women in Research (Global Research Council, 2016); https://www.globalresearchcouncil.org/fileadmin//documents/GRC_Publications/Statement_of_Principles_and_Actions_Promoting_the_Equality_and_Status_of_Women_in_Research.pdf

Huyer, S. in UNESCO Science Report: Towards 203 0 (ed. Schneegans, S.) 84–103 (UNESCO Publishing, Paris, 2015); http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf

Maes, K., Gvozdanovic, J., Buitendijk, S., Hallberg, I. R. & Mantilleri, B. Women, Research and Universities: Excellence Without Gender Bias (League of European Research Universities, Leuven, 2012).

Diversity in science. The Royal Society https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/diversity-in-science/topic/ (2017).

Valantine, H. A. & Collins, F. S. National Institutes of Health addresses the science of diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 12240–12242 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hong, L. & Page, S. E. Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101 , 16385–16389 (2004).

Page, S. E. The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 2008).

Phillips, K. W. How diversity works. Sci. Am. 311 , 42–47 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Nishii, L. H. The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Acad. Manage. J. 56 , 1754–1774 (2013).

Bear, J. B. & Woolley, A. W. The role of gender in team collaboration and performance. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 36 , 146–153 (2011).

Joshi, A., Liao, H. & Roh, H. Bridging domains in workplace demography research: a review and reconceptualization. J. Manage. 37 , 521–552 (2011).

Google Scholar

Van Dijk, H., van Engen, M. L. & van Knippenberg, D. Defying conventional wisdom: a meta-analytical examination of the differences between demographic and job related diversity relationships with performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 119 , 38–53 (2012).

Díaz-García, C., González-Moreno, A. & Jose Sáez-Martínez, F. Gender diversity within R&D teams: its impact on radicalness of innovation. Innovation 15 , 149–160 (2013).

Faems, D. & Subramanian, A. M. R&D manpower and technological performance: the impact of demographic and task-related diversity. Res. Policy 42 , 1624–1633 (2013).

Fernández, J. The impact of gender diversity in foreign subsidiaries’ innovation outputs. Int. J. Gend Entrep. 7 , 148–167 (2015).

Østergaard, C. R., Timmermans, B. & Kristinsson, K. Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation. Res. Policy 40 , 500–509 (2011).

Sastre, J. F. The impact of R&D teams’ gender diversity on innovation outputs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 24 , 142–162 (2015).

Turner, L. Gender diversity and innovative performance. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 4 , 123–134 (2009).

Campbell, L. G., Mehtani, S., Dozier, M. E. & Rinehart, J. Gender-heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. PLoS ONE 8 , e79147 (2013).

Joshi, A. By whom and when is women’s expertise recognized? The interactive effects of gender and education in science and engineering teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 25 , 202–239 (2014).

Lungeanu, A. & Contractor, N. S. The effects of diversity and network ties on innovations: the emergence of a new scientific field. Am. Behav. Sci. 59 , 548–564 (2015).

Saá-Pérez, D., Díaz-Díaz, N. L., Aguiar-Díaz, I. & Ballesteros-Rodríguez, J. L. How diversity contributes to academic research teams performance. R&D Manage. 47 , 165–179 (2015).

Stvilia, B. et al. Composition of scientific teams and publication productivity at a national science lab. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 62 , 270–283 (2011).

For a Better Integration of the Gender Dimension in Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2016–2017 (European Commission, 2015); http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetailDoc&id=18892&no=1

Buitendijk, S. & Maes, K. Gendered Research and Innovation: Integrating Sex and Gender Analysis into the Research Process (League of European Research Universities, Leuven, 2015).

Schiebinger, L. & Klinge, I. Gendered Innovations: How Gender Analysis Contributes to Research (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013).

Sánchez de Madariaga, I., de Gregorio Hurtado, S. (eds). Advancing Gender in Research, Innovation and Sustainable Development (Fundación General de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 2016).

Bührer, S. & Schraudner, M. Gender-Aspekte in der Forschung: Wie können Gender-Aspekte in Forschungsvorhaben erkannt und bewertet werden? (Frauenhofer IRB Verlag, Stuttgart, 2006).

Adler, R. A. Osteoporosis in men: a review. Bone Res. 2 , 14001 (2014).

Schiebinger, L. et al. Sex and gender analysis policies of major granting agencies. Gendered Innovations http://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/sex-and-gender-analysis-policies-major-granting-agencies.html (2018).

Johnson, J., Sharman, Z., Vissandjee, B. & Stewart, D. E. Does a change in health research funding policy related to the integration of sex and gender have an impact? PLoS ONE 9 , e99900 (2014).

De Cheveigné, S. & Knoll, B. Interim Evaluation: Gender Equality as a Crosscutting Issue in Horizon 2020 (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2017).

European Commission She Figures 2015 (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2016).

US General Accounting Office. Drug Safety: Most Drugs Withdrawn in Recent Years had Greater Health Risks for Women (Government Publishing Office, Washington DC, 2001).

Roth, J. et al. Economic return from the women’s health initiative estrogen plus progestin clinical trial: a modeling study. Ann. Intern. Med. 160 , 594–602 (2014).

Ovseiko, P. V. et al. A global call for action to include gender in research impact assessment. Health Res. Policy Syst. 14 , 50 (2016).

Nielsen, M. W. et al. Opinion: gender diversity leads to better science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 1740–1742 (2017).

Dolado, J. J., Felgueroso, F. & Almunia, M. Are men and women-economists evenly distributed across research fields? Some new empirical evidence. SERIEs 3 , 367–393 (2012).

Light, R. in Networks, Work, and Inequality (ed. Mcdonald, S.) 239–268 (Research in the Sociology of Work Vol. 24, Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, 2013).

Mapping Gender in the German Research Area (Elsevier, 2015); https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/126715/ELS_Germany_Gender_Research-SinglePages.pdf

Maliniak, D., Powers, R. & Walter, B. F. The gender citation gap in international relations. Int. Organ. 67 , 889–922 (2013).

West, J. D., Jacquet, J., King, M. M., Correll, S. J. & Bergstrom, C. T. The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS ONE 8 , e66212 (2013).

Nonnemaker, L. Women physicians in academic medicine — new insights from cohort studies. N. Engl. J. Med. 342 , 399–405 (2000).

Rosser, S. V. An overview of women’s health in the US since the mid-1960s. Hist. Technol . 18 , 355–369 (2002).

Schiebinger, L. Has Feminism Changed Science? (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1999).

Fedigan, L. M. Primate Paradigms: Sex Roles and Social Bonds (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992).

Schiebinger, L. (ed.) Gendered Innovations in Science and Engineering (Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, 2008).

Nielsen, M. W., Andersen, J. P., Schiebinger, L. & Schneider, J. W. One and a half million medical papers reveal a link between author gender and attention to gender and sex analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 , 791–796 (2017).

Herring, C. Does diversity pay? Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 74 , 208–224 (2009).

Mannix, E. & Neale, M. A. What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 6 , 31–55 (2005).

Shore, L. M. et al. Diversity in organizations: Where are we now and where are we going? Hum. Resour . Manage. Rev. 19 , 117–133 (2009).

Williams, K. Y. & O’Reilly, C. A. in Research in Organizational Behavior (eds Staw, B. M. & Cummings, L. L.) 77–140 (JAI Press, Greenwich, 1998).

Homan, A. C., Van Knippenberg, D., Van Kleef, G. A. & De Dreu, C. K. Bridging faultlines by valuing diversity: diversity beliefs, information elaboration, and performance in diverse work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 92 , 1189–1199 (2007).

Lauring, J. & Villesèche, F. The performance of gender diverse teams: What is the relation between diversity attitudes and degree of diversity? Eur. Manage. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12164 (2017).

Van Knippenberg, D., Haslam, S. A. & Platow, M. J. Unity through diversity: value-in-diversity beliefs, work group diversity, and group identification. Group Dyn. 11 , 207–222 (2007).

Hobman, E. V., Bordia, P. & Gallois, C. Perceived dissimilarity and work group involvement: the moderating effects of group openness to diversity. Group Organ. Manage. 29 , 560–587 (2004).

Joshi, A. & Knight, A. P. Who defers to whom and why? Dual pathways linking demographic differences and dyadic deference to team effectiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 58 , 59–84 (2015).

Hobman, E. V. & Bordia, P. The role of team identification in the dissimilarity-conflict relationship. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 9 , 483–507 (2006).

Mohammed, S. & Angell, L. C. Surface- and deep-level diversity in workgroups: examining the moderating effects of team orientation and team process on relationship conflict. J. Organ. Behav. 25 , 1015–1039 (2004).

Homan, A. C. et al. Facing differences with an open mind: openness to experience, salience of intragroup differences, and performance of diverse work groups. Acad. Manage. J. 51 , 1204–1222 (2008).

Roos, P. A. & Reskin, B. F. Occupational desegregation in the 1970s: Integration and economic equity? Sociol. Perspect. 35 , 69–91 (1992).

Lautenberger, D. M., Dandar, V. M. & Raezer, C. L. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership 2013–2014 (Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington DC, 2014).

Becher, T. The significance of disciplinary differences. Stud. Higher Educ. 19 , 151–161 (1994).

Zou, J. & Schiebinger, L. AI can be sexist and racist — it’s time to make it fair. Nature 559 , 324–326 (2018).

Felt, U. & Stöckelová, T. in Knowing and Living in Academic Research (ed. Felt, U.) 41–124 (Institute of Sociology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague, 2009).

Lamont, M. How Professors Think (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2009).

Whitley, R. The Intellectual and Social Organization of the Sciences (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2000).

Stewart, A. J., Malley, J. E. & LaVaque-Manty, D. Transforming Science and Engineering: Advancing Academic Women (Univ. Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2007).

Courses. Course 1: the science of sex and gender in human health. National Institutes of Health https://sexandgendercourse.od.nih.gov/content/courses (2018).

Sex and Gender in Biomedical Research (Canadian Institutes of Health, 2018); http://www.cihr-irsc-igh-isfh.ca/

Schiebinger, L. et al. Sex and gender analysis policies of peer-reviewed journals. Gendered Innovations https://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/sex-and-gender-analysis-policies-peer-reviewed-journals.html (2018).

Author instructions: manuscript preparation Circulation Research https://www.ahajournals.org/res/manuscript-preparation (2018).

Miller, V. M. In pursuit of scientific excellence: sex matters. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 302 , C1269–C1270 (2012).

Schiebinger, L., Leopold, S. S. & Miller, V. M. Editorial policies for sex and gender analysis. Lancet 388 , 2841–2842 (2016).

Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, 2017); http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/archives/

Ludwig, S. et al. A successful strategy to integrate sex and gender medicine into a newly developed medical curriculum. J. Womens Health 24 , 996–1005 (2015).

Brooks, C., Fenton, E. M. & Walker, T. J. Gender and the evaluation of research. Res. Policy 43 , 990–1001 (2014).

Hunter, L. A. & Leahey, E. Parenting and research productivity: new evidence and methods. Soc. Stud. Sci. 40 , 433–451 (2010).

Nielsen, M. W. Gender consequences of a national performance-based funding model: new pieces in an old puzzle. Stud. Higher Educ. 42 , 1033–1055 (2017).

Schneid, M., Isidor, R., Li, C. & Kabst, R. The influence of cultural context on the relationship between gender diversity and team performance: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 26 , 733–756 (2015).

European Commission Seventh FP7 Monitoring Report 2013 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2015).

C ommission Staff Working Document: Horizon 2020 Annual Monitoring Report 2015 (European Commission, 2016).

Fact Sheet: Gender Equality in Horizon 2020 (European Commission, 2013); https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/sites/horizon2020/files/FactSheet_Gender_2.pdf

Topics with a gender dimension. European Commission http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/portal/desktop/en/opportunities/h2020/ftags/gender.html#c,topics=flags/s/Gender/1/1&+callDeadline/desc (2015).

Clayton, J. & Collins, F. NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature 509 , 282–283 (2014).

Aksnes, D. et al. Centres of Excellence in the Nordic Countries (NIFU, Oslo, 2012).

Sandström, U., Wold, A., Jordansson, B., Ohlsson, B. & Smedberg, Å. Hans Excellens: om miljardsatsningarna på starka forskningsmiljöer (Delegationen för Jämställdhet i Högskolan, Stockholm, 2010).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Steiner, Co-Director, Spatial History Project, Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, Stanford University, for executing our graphics.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy, Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

Mathias Wullum Nielsen & Carter Walter Bloch

History of Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Londa Schiebinger

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

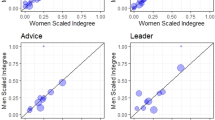

M.W.N., L.S. and C.W.B. conceptualized and wrote the paper. M.W.N. and L.S. carried out literature searches, and M.W.N. and C.W.B. prepared tables. L.S. and M.W.N. conceptualized Figs. 1 and 2.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mathias Wullum Nielsen .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

: Supplementary Methods; Supplementary Table 1 -4

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nielsen, M.W., Bloch, C.W. & Schiebinger, L. Making gender diversity work for scientific discovery and innovation. Nat Hum Behav 2 , 726–734 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0433-1

Download citation

Received : 09 February 2018

Accepted : 18 July 2018

Published : 24 September 2018

Issue Date : October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0433-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Feminization of the health workforce in china: exploring gendered composition from 2002 to 2020.

- Joanna Raven

- Xiaoyun Liu

Human Resources for Health (2024)

How to diversify the dwindling physician–scientist workforce after the US affirmative action ban

- Jessica L. Ding

- Briana Christophers

- Alex D. Waldman

Nature Medicine (2024)

Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research

- Lisa Messeri

- M. J. Crockett

Nature (2024)

The cyclical ethical effects of using artificial intelligence in education

- Edward Dieterle

- Michael Walker

AI & SOCIETY (2024)

Gender inequality in genitourinary malignancies clinical trials leadership

- Abdulrahman Alhajahjeh

- Ahmed A. Abdulelah

- Mohammed Shahait

World Journal of Urology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Help & FAQ

Gender and the Research Excellence Framework

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter (peer-reviewed) › peer-review

Access to Document

- 10.1163/9789463511438

T1 - Gender and the Research Excellence Framework

AU - Yarrow, Emily

PY - 2018/1/1

Y1 - 2018/1/1

U2 - 10.1163/9789463511438

DO - 10.1163/9789463511438

M3 - Chapter (peer-reviewed)

SN - 9463511423

SN - 978-94-6351-142-1

SN - 978-94-6351-141-4

BT - EqualBITE

A2 - Robertson, Judy

A2 - Williams, Alison

A2 - Jones, Derek

A2 - Loads, Daphne

PB - Brill Sense

CY - Rotterdam, Netherlands

Gender Plays a Role in Research Impact and Assessment

You may not have heard about the impact a-gender, but the chances are you have encountered it in water-cooler conversations, university corridors, or the formal settings of meetings and review panels… By this, simply put, we mean the implicit and explicit gendered associations often drawn when academics refer to types of impact activities and how this can creep into the evaluation of impact. Previous work by Yarrow and Davies has shown that women were significantly less likely to be the authors of impact case studies in the 2014 round of the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF). Our own research reinforces this observation, revealing how gendered assumptions toward impact and its assessment play a significant role in all aspects of research impact; from deciding what kinds of research impact receive attention, to the way in which REF panels codify and assess the quality of research impacts.

To explore how gender might underscore thinking about research impact, we re-evaluated two independent datasets to examine the ways in which impact was described in both the generation and evaluation of research impact: the first containing semi-structured interviews with mid-senior academics at two research-intensive universities in Australia and the UK, collected between 2011 and 2013 (n=51); and the second including pre- (n=62), and post-evaluation (n=57) interviews with REF2014 Main Panel A (medicine, health and life sciences) evaluators.

We found that gendered perceptions of research impact to run deep and that regardless of a participant’s gender, unconsciously assigned gendered orientations to impact activities were attributed to research impact that were then repeated during evaluation. We call this process, by which gendered notions of non-academic, societal impact and how it is generated feed into its evaluation, the ‘impact a-gender.’ Left unchecked, this risks compounding gender inequality in academia; creating an additional ‘ Matilda effect ’ for research impact, whereby the achievements of female researchers are further marginalized.

Gendered definitions of impact

The gendered nature of impact begins with defining impact itself. For example, during our interviews, researchers in the UK and Australia used terms such as ‘hard’ (masculine) or ‘soft’ (feminine) when talking about the types of impact created and these were prevalent alongside gendered notions of excellence related to competitiveness. These binary associations are integral to the way gender bias infiltrates academia generally, but here we see this association towards non-academic impact. When referring to impact more generally, it was not necessarily the masculinity or femininity of the researcher that was emphasized, but rather the activity used to generate it. ‘Soft’ impact activities were described as:

“Stuff that’s on a flaky edge – it’s very much about social engagement” (Languages, Australia, Professor, Male).

Researchers placed value on hard over soft impacts, referring to how soft impacts were of less value to institutions and amongst their colleagues. Even the word impact itself, is to some extent burdened with gendered connotations of ‘force’ and ‘weight.’

Gendered sorting of impact activities

When asked about engaging in Impact, both men and women were dissuaded (by inner narratives, institutions, or by colleagues) from engaging in impacts that were not conducive to ‘hard’ impacts. Researchers reported being pressured away from non-gender-acceptable forms of impact, either in preference to other more masculine notions of academic productivity (for men), or towards soft notions of academic productivity, i.e. public outreach (for women).

In practice, some men, in particular, implicitly referred to women as better with the ‘soft and woolly’ impacts and justified this based on a sense of ‘duty’ or ‘public service’ associated with the nurturing role commonly assigned to women. This immediately and implicitly assigned certain types of impact activities to women, such as public engagement, while the more dominant, activities that lead to economic impacts, such as technology transfer, relating less to people and more to things i.e. licensing or spin-outs, were more likely to be assigned to men. When the reason behind this association was explored, gendered notions of competitiveness emerged: (talking about public engagement) “women are better at this! They are less competitive!” (Environment, UK, Professor, Male). W omen were perceived as not sufficiently competitive for ‘harder’ impacts, despite having already been steered away from engaging in these activities.

Gendered evaluations of impact

In a further extension of the impact a-gender, these gendered associations of Impact were echoed by Impact evaluators. Here, despite a shift away from impact and measurement, the types of impact that are not as easily measurable and are, by nature, more amenable to qualitative narratives around societal and cultural value, were again characterized as ‘soft.’ In contrast, quantifiable impact was often masculinized and more regularly depicted as ‘hard.’ For instance, when articulating impact, male evaluators were more likely to express impact as causal and linear, involving a single “star” or “champion,” who delivered it from start (underpinning research) to finish (impact). So too, when these binary interpretations were present, they were more likely to value impact in a way in which encoded perceptions of hard/ quantifiable/ masculine research (as opposed to soft/ qualitative/ feminine) were considered as being higher quality and of more esteem, regardless of the actual quality of the research or its impact.

Male and female evaluators also conceptualized impact differently for the sake of its evaluation. Female evaluators were more open to and expressed sensitivity towards the complexity of impact and this included taking into account issues of time-lags, reasons for the lack of causality (especially for policy impacts) and reasonable attribution claims. Male evaluators, on the other hand, strived to conceptualize impact as excellent if it was a “straight -forward” and “measurable change.”

Gendered evaluators of impact

Finally, evaluators also suggested that the workings of the panel during the evaluation were also drawn down gendered lines. If accurate, this risks silencing conflicting opinions that may call for a more complex approach to Impact evaluation. In this way, women were valued as panel members if they played a supportive, supplementary role and were a good “team player”:

“A good panel member was — someone who is happy to listen to discussions; to not be too dogmatic about their opinion, but can listen and learn, because impact is something we are all learning from scratch. Somebody who wasn’t too outspoken, was a team player.” (Panel 3, Outputs and Impact, Female)

Calling out the impact a-gender

Our research suggests that notions of soft and hard impact are not simply benign, but can serve to marginalize individuals, groups and particular kinds of research. What we have uncovered, we fear, only scratches the surface of some of the ways in which an impact a-gender emerges within the academic community, and evaluation panels. However, its implications will be familiar to many researchers preparing REF case studies, and to policymakers that are working to ensure that the REF evaluation process is free from these implicit biases.

What we must do, as a community, is reflect on our scholarly norms of intellectual practice; to be skeptical about our own preconceptions and attitudes which come as second nature and to question our assumptions and prejudices. Individually, we must continually and explicitly check our own behavior to minimize any further follow on effects. This is regardless of whether we work as researchers generating impact, or as evaluators assessing it.

The impact a-gender is known and it is not acceptable. Let’s not leave it unchecked.

Jennifer Chubb and Gemma Derrick

Jennifer Chubb (pictured) is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of York. Chubb's research career to date has focused on the philosophy and politics of research, identities and research cultures, research impact and science policy and advice. She has a particular interest in the impact and ethical implications of emerging technologies. Her current research focuses on the impact of artificial intelligence and related digital technologies. Gemma Derrick is a senior lecturer and director of research at the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University. Derrick's research focuses on the dynamics of knowledge production and how researchers create, conform and participate in evaluative cultures within academia. She has a particular specialty in the evaluation Impact using peer review and its role in the academic governance system.

Related Articles

Three Decades of Rural Health Research and a Bumper Crop of Insights from South Africa

Using Translational Research as a Model for Long-Term Impact

Norman B. Anderson, 1955-2024: Pioneering Psychologist and First Director of OBSSR

New Feminist Newsletter The Evidence Makes Research on Gender Inequality Widely Accessible

New Podcast Series Applies Social Science to Social Justice Issues

Sage (the parent of Social Science Space) and the Surviving Society podcast have launched a collaborative podcast series, Social Science for Social […]

The Importance of Using Proper Research Citations to Encourage Trustworthy News Reporting

Based on a study of how research is cited in national and local media sources, Andy Tattersall shows how research is often poorly represented in the media and suggests better community standards around linking to original research could improve trust in mainstream media.

Connecting Legislators and Researchers, Leads to Policies Based on Scientific Evidence

The author’s team is developing ways to connect policymakers with university-based researchers – and studying what happens when these academics become the trusted sources, rather than those with special interests who stand to gain financially from various initiatives.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Quality in Postgraduate Research Conference 2024

Scecsal 2024: transforming libraries, empowering communities, webinar: how to do research in a digital world, webinar: how to write and structure an article’s front matter, webinar: how to get more involved with a journal and develop your career, science of team science 2024 virtual conference, webinar: how to collaborate across paradigms – embedding culture in mixed methods designs.

Customize your experience

Select your preferred categories.

- Announcements

- Business and Management INK

Communication

Higher education reform, open access, recent appointments, research ethics, interdisciplinarity, international debate.

- Academic Funding

Public Engagement

- Recognition

Presentations

Science & social science, social science bites, the data bulletin.

Social, Behavioral Scientists Eligible to Apply for NSF S-STEM Grants

Solicitations are now being sought for the National Science Foundation’s Scholarships in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics program, and in an unheralded […]

With COVID and Climate Change Showing Social Science’s Value, Why Cut it Now?

What are the three biggest challenges Australia faces in the next five to ten years? What role will the social sciences play in resolving these challenges? The Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia asked these questions in a discussion paper earlier this year. The backdrop to this review is cuts to social science disciplines around the country, with teaching taking priority over research.

Testing-the-Waters Policy With Hypothetical Investment: Evidence From Equity Crowdfunding

While fundraising is time-consuming and entails costs, entrepreneurs might be tempted to “test the water” by simply soliciting investors’ interest before going through the lengthy process. Digitalization of finance has made it possible for small business to run equity crowdfunding campaigns, but also to initiate a TTW process online and quite easily.

AAPSS Names Eight as 2024 Fellows

The American Academy of Political and Social Science today named seven scholars and one journalist as its 2024 fellows class.

Apply for Sage’s 2024 Concept Grants

Three awards are available through Sage’s Concept Grant program, which is designed to support innovative products and tools aimed at enhancing social science education and research.

Economist Kaye Husbands Fealing to Lead NSF’s Social Science Directorate

Kaye Husbands Fealing, an economist who has done pioneering work in the “science of broadening participation,” has been named the new leader of the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences.

Big Think Podcast Series Launched by Canadian Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences

The Canadian Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences has launched the Big Thinking Podcast, a show series that features leading researchers in the humanities and social sciences in conversation about the most important and interesting issues of our time.

The We Society Explores Intersectionality and Single Motherhood

In a recently released episode of The We Society podcast, Ann Phoenix, a psychologist at University College London’s Institute of Education, spoke […]

Second Edition of ‘The Evidence’ Examines Women and Climate Change

The second issue of The Evidence explores the intersection of gender inequality and the global climate crisis. Author Josephine Lethbridge recounts the […]

New Report Finds Social Science Key Ingredient in Innovation Recipe

A new report from Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences argues that the key to success for physical science and technology research is a healthy helping of relevant social science.

Too Many ‘Gray Areas’ In Workplace Culture Fosters Racism And Discrimination

The new president of the American Sociological Association spent more than 10 years interviewing over 200 Black workers in a variety of roles – from the gig economy to the C-suite. I found that many of the problems they face come down to organizational culture. Too often, companies elevate diversity as a concept but overlook the internal processes that disadvantage Black workers.

A Social Scientist Looks at the Irish Border and Its Future

‘What Do We Know and What Should We Do About the Irish Border?’ is a new book from Katy Hayward that applies social science to the existing issues and what they portend.

Brexit and the Decline of Academic Internationalism in the UK

Brexit seems likely to extend the hostility of the UK immigration system to scholars from European Union countries — unless a significant change of migration politics and prevalent public attitudes towards immigration politics took place in the UK. There are no indications that the latter will happen anytime soon.

Brexit and the Crisis of Academic Cosmopolitanism

A new report from the Royal Society about the effects on Brexit on science in the United Kingdom has our peripatetic Daniel Nehring mulling the changes that will occur in higher education and academic productivity.

Challenging, But Worth It: Overcoming Paradoxical Tensions of Identity to Embrace Transformative Technologies in Teaching and Learning

In this article, Isabel Fischer and Kerry Dobbins reflect on their work, “Is it worth it? How paradoxical tensions of identity shape the readiness of management educators to embrace transformative technologies in their teaching,” which was recently published in the Journal of Management Education.

Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence in the Complex Environment of Megaprojects: Implications for Practitioners and Project Organizing Theory

The authors review the ways in which data analytics and artificial intelligence can engender more stability and efficiency in megaprojects. They evaluate the present and likely future use of digital technology—particularly with regard to construction projects — discuss the likely benefits, and also consider some of the challenges around digitization.

Putting People at the Heart of the Research Process

In this article, Jessica Weaver, Philippa Hunter-Jones, and Rory Donnelly reflect on “Unlocking the Full Potential of Transformative Service Research by Embedding Collaboration Throughout the Research Process,” which can be found in the Journal of Service Research.

2024 Holberg Prize Goes to Political Theorist Achille Mbembe

Political theorist and public intellectual Achille Mbembe, among the most read and cited scholars from the African continent, has been awarded the 2024 Holberg Prize.

Edward Webster, 1942-2024: South Africa’s Pioneering Industrial Sociologist

Eddie Webster, sociologist and emeritus professor at the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, died on March 5, 2024, at age 82.

Charles V. Hamilton, 1929-2023: The Philosopher Behind ‘Black Power’

Political scientist Charles V. Hamilton, the tokenizer of the term ‘institutional racism,’ an apostle of the Black Power movement, and at times deemed both too radical and too deferential in how to fight for racial equity, died on November 18, 2023. He was 94.

National Academies Seeks Experts to Assess 2020 U.S. Census

The National Academies’ Committee on National Statistics seeks nominations for members of an ad hoc consensus study panel — sponsored by the U.S. Census Bureau — to review and evaluate the quality of the 2020 Census.

Will the 2020 Census Be the Last of Its Kind?

Could the 2020 iteration of the United States Census, the constitutionally mandated count of everyone present in the nation, be the last of its kind?

Will We See A More Private, But Less Useful, Census?

Census data can be pretty sensitive – it’s not just how many people live in a neighborhood, a town, a state or […]

Did the Mainstream Make the Far-Right Mainstream?

The processes of mainstreaming and normalization of far-right politics have much to do with the mainstream itself, if not more than with the far right.

The Use of Bad Data Reveals a Need for Retraction in Governmental Data Bases

Retractions are generally framed as a negative: as science not working properly, as an embarrassment for the institutions involved, or as a flaw in the peer review process. They can be all those things. But they can also be part of a story of science working the right way: finding and correcting errors, and publicly acknowledging when information turns out to be incorrect.

Free Online Course Reveals The Art of ChatGPT Interactions

You’ve likely heard the hype around artificial intelligence, or AI, but do you find ChatGPT genuinely useful in your professional life? A free course offered by Sage Campus could change all th

Research Integrity Should Not Mean Its Weaponization

Commenting on the trend for the politically motivated forensic scrutiny of the research records of academics, Till Bruckner argues that singling out individuals in this way has a chilling effect on academic freedom and distracts from efforts to address more important systemic issues in research integrity.

What Do We Know about Plagiarism These Days?

In the following Q&A, Roger J. Kreuz, a psychology professor who is working on a manuscript about the history and psychology of plagiarism, explains the nature and prevalence of plagiarism and the challenges associated with detecting it in the age of AI.

Webinar: iGen: Decoding the Learning Code of Generation Z

As Generation Z students continue to enter the classroom, they bring with them a host of new challenges. This generation of students […]

Year of Open Science Conference

The Center for Open Science (COS), in collaboration with NASA, is hosting a no-cost, online culminating conference on March 21 and 22 […]

“How to Collaborate Across Paradigms: Embedding Culture in Mixed Methods Designs” is another piece of Sage’s webinar series, How to Do Research […]

Returning Absentee Ballots during the 2020 Election – A Surprise Ending?

One of the most heavily contested voting-policy issues in the 2020 election, in both the courts and the political arena, was the deadline […]

Overconsumption or a Move Towards Minimalism?

(Over)consumption, climate change and working from home. These are a few of the concerns at the forefront of consumers’ minds and three […]

To Better Serve Students and Future Workforces, We Must Diversify the Syllabi

Ellen Hutti and Jenine Harris have quantified the extent to which female authors are represented in assigned course readings. In this blog post, they emphasize that more equal exposure to experts with whom they can identify will better serve our students and foster the growth, diversity and potential of this future workforce. They also present one repository currently being built for readings by underrepresented authors that are Black, Indigenous or people of color.

Drawing on the findings of a workshop on making translational research design principles the norm for European research, Gabi Lombardo, Jonathan Deer, Anne-Charlotte Fauvel, Vicky Gardner and Lan Murdock discuss the characteristics of translational research, ways of supporting cross disciplinary collaboration, and the challenges and opportunities of adopting translational principles in the social sciences and humanities.

Addressing the United Kingdom’s Lack of Black Scholars

In the UK, out of 164 university vice-chancellors, only two are Black. Professor David Mba was recently appointed as the first Black vice-chancellor […]

A longitudinal research project project covering 31 villages in rural South Africa has led to groundbreaking research in many fields, including genomics, HIV/Aids, cardiovascular conditions and stroke, cognition and aging.

Norman B. Anderson, a clinical psychologist whose work as both a researcher and an administrator saw him serve as the inaugural director of the U.S. National Institute of Health’s Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research and as chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association, died on March 1.

Why Social Science? Because It Makes an Outsized Impact on Policy

Euan Adie, founder of Altmetric and Overton and currently Overton’s managing director, answers questions about the outsized impact that SBS makes on policy and his work creating tools to connect the scholarly and policy worlds.

A Behavioral Scientist’s Take on the Dangers of Self-Censorship in Science

The word censorship might bring to mind authoritarian regimes, book-banning, and restrictions on a free press, but Cory Clark, a behavioral scientist at […]

Infrastructure

New Funding Opportunity for Criminal and Juvenile Justice Doctoral Researchers

A new collaboration between the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the U.S. National Science Foundation has founded the Graduate Research Fellowship […]

To Better Forecast AI, We Need to Learn Where Its Money Is Pointing

By carefully interrogating the system of economic incentives underlying innovations and how technologies are monetized in practice, we can generate a better understanding of the risks, both economic and technological, nurtured by a market’s structure.

There’s Something in the Air, Part 2 – But It’s Not a Miasma

Robert Dingwall looks at the once dominant role that miasmatic theory had in public health interventions and public policy.

The Fog of War

David Canter considers the psychological and organizational challenges to making military decisions in a war.

A Community Call: Spotlight on Women’s Safety in the Music Industry

Women’s History Month is, when we “honor women’s contributions to American history…” as a nation. Author Andrae Alexander aims to spark a conversation about honor that expands the actions of this month from performative to critical

Philip Rubin: FABBS’ Accidental Essential Man Linking Research and Policy

As he stands down from a two-year stint as the president of the Federation of Associations in Behavioral & Brain Sciences, or FABBS, Social Science Space took the opportunity to download a fraction of the experiences of cognitive psychologist Philip Rubin, especially his experiences connecting science and policy.

How Intelligent is Artificial Intelligence?

Cryptocurrencies are so last year. Today’s moral panic is about AI and machine learning. Governments around the world are hastening to adopt […]

National Academies’s Committee On Law And Justice Seeks Experts

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine is seeking suggestions for experts interested in its Committee on Law and Justice (CLAJ) […]

Why Don’t Algorithms Agree With Each Other?

David Canter reviews his experience of filling in automated forms online for the same thing but getting very different answers, revealing the value systems built into these supposedly neutral processes.

A Black History Addendum to the American Music Industry

The new editor of the case study series on the music industry discusses the history of Black Americans in the recording industry.

When University Decolonization in Canada Mends Relationships with Indigenous Nations and Lands

Community-based work and building and maintaining relationships with nations whose land we live upon is at the heart of what Indigenizing is. It is not simply hiring more faculty, or putting the titles “decolonizing” and “Indigenizing” on anything that might connect to Indigenous peoples.

Jonathan Breckon On Knowledge Brokerage and Influencing Policy

Overton spoke with Jonathan Breckon to learn about knowledge brokerage, influencing policy and the potential for technology and data to streamline the research-policy interface.

Research for Social Good Means Addressing Scientific Misconduct

Social Science Space’s sister site, Methods Space, explored the broad topic of Social Good this past October, with guest Interviewee Dr. Benson Hong. Here Janet Salmons and him talk about the Academy of Management Perspectives journal article.

NSF Looks Headed for a Half-Billion Dollar Haircut

Funding for the U.S. National Science Foundation would fall by a half billion dollars in this fiscal year if a proposed budget the House of Representatives’ Appropriations Committee takes effect – the first cut to the agency’s budget in several years.

NSF Responsible Tech Initiative Looking at AI, Biotech and Climate

The U.S. National Science Foundation’s new Responsible Design, Development, and Deployment of Technologies (ReDDDoT) program supports research, implementation, and educational projects for multidisciplinary, multi-sector teams

Digital Transformation Needs Organizational Talent and Leadership Skills to Be Successful

Who drives digital change – the people of the technology? Katharina Gilli explains how her co-authors worked to address that question.

Six Principles for Scientists Seeking Hiring, Promotion, and Tenure

The negative consequences of relying too heavily on metrics to assess research quality are well known, potentially fostering practices harmful to scientific research such as p-hacking, salami science, or selective reporting. To address this systemic problem, Florian Naudet, and collegues present six principles for assessing scientists for hiring, promotion, and tenure.

Book Review: The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries

Candace Jones, Mark Lorenzen, Jonathan Sapsed , eds.: The Oxford Handbook of Creative Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 576 pp. $170.00, […]

Daniel Kahneman, 1934-2024: The Grandfather of Behavioral Economics

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, whose psychological insights in both the academic and the public spheres revolutionized how we approach economics, has died […]

Gloria Media, with support from Sage, has launched The Evidence, a feminist newsletter that covers what you need to know about gender […]

Canadian Librarians Suggest Secondary Publishing Rights to Improve Public Access to Research

The Canadian Federation of Library Associations recently proposed providing secondary publishing rights to academic authors in Canada.

Webinar: How Can Public Access Advance Equity and Learning?

The U.S. National Science Foundation and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have teamed up present a 90-minute online session examining how to balance public access to federally funded research results with an equitable publishing environment.

- Open Access in the Humanities and Social Sciences in Canada: A Conversation

Five organizations representing knowledge networks, research libraries, and publishing platforms joined the Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences to review the present and the future of open access — in policy and in practice – in Canada

A Former Student Reflects on How Daniel Kahneman Changed Our Understanding of Human Nature

Daniel Read argues that one way the late Daniel Kahneman stood apart from other researchers is that his work was driven by a desire not merely to contribute to a research field, but to create new fields.

Four Reasons to Stop Using the Word ‘Populism’

Beyond poor academic practice, the careless use of the word ‘populism’ has also had a deleterious impact on wider public discourse, the authors argue.

The Added Value of Latinx and Black Teachers

As the U.S. Congress debates the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, a new paper in Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences urges lawmakers to focus on provisions aimed at increasing the numbers of black and Latinx teachers.

A Collection: Behavioral Science Insights on Addressing COVID’s Collateral Effects

To help in decisions surrounding the effects and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the the journal ‘Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences’ offers this collection of articles as a free resource.

Susan Fiske Connects Policy and Research in Print

Psychologist Susan Fiske was the founding editor of the journal Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences. In trying to reach a lay audience with research findings that matter, she counsels stepping a bit outside your academic comfort zone.

Mixed Methods As A Tool To Research Self-Reported Outcomes From Diverse Treatments Among People With Multiple Sclerosis

What does heritage mean to you?

Personal Information Management Strategies in Higher Education

Working Alongside Artificial Intelligence Key Focus at Critical Thinking Bootcamp 2022

SAGE Publishing — the parent of Social Science Space – will hold its Third Annual Critical Thinking Bootcamp on August 9. Leaning more and register here

Watch the Forum: A Turning Point for International Climate Policy

On May 13, the American Academy of Political and Social Science hosted an online seminar, co-sponsored by SAGE Publishing, that featured presentations […]

Event: Living, Working, Dying: Demographic Insights into COVID-19

On Friday, April 23rd, join the Population Association of America and the Association of Population Centers for a virtual congressional briefing. The […]

Involving patients – or abandoning them?

The Covid-19 pandemic seems to be subsiding into a low-level endemic respiratory infection – although the associated pandemics of fear and action […]

Public Policy

Jane M. Simoni Named New Head of OBSSR

Clinical psychologist Jane M. Simoni has been named to head the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

Canada’s Federation For Humanities and Social Sciences Welcomes New Board Members

Annie Pilote, dean of the faculty of graduate and postdoctoral studies at the Université Laval, was named chair of the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences at its 2023 virtual annual meeting last month. Members also elected Debra Thompson as a new director on the board.

Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences Names Spring 2024 Fellows

Forty-one leading social scientists have been named to the Spring 2024 cohort of fellows for Britain’s Academy of Social Sciences.

National Academies Looks at How to Reduce Racial Inequality In Criminal Justice System

To address racial and ethnic inequalities in the U.S. criminal justice system, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine just released “Reducing Racial Inequality in Crime and Justice: Science, Practice and Policy.”

Survey Examines Global Status Of Political Science Profession

The ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science Survey 2023 assesses political science scholar’s viewpoints on the global status of the discipline and the challenges it faces, specifically targeting the phenomena of cancel culture, self-censorship and threats to academic freedom of expression.

Report: Latest Academic Freedom Index Sees Global Declines

The latest update of the global Academic Freedom Index finds improvements in only five countries

The Risks Of Using Research-Based Evidence In Policymaking

With research-based evidence increasingly being seen in policy, we should acknowledge that there are risks that the research or ‘evidence’ used isn’t suitable or can be accidentally misused for a variety of reasons.

Surveys Provide Insight Into Three Factors That Encourage Open Data and Science

Over a 10-year period Carol Tenopir of DataONE and her team conducted a global survey of scientists, managers and government workers involved in broad environmental science activities about their willingness to share data and their opinion of the resources available to do so (Tenopir et al., 2011, 2015, 2018, 2020). Comparing the responses over that time shows a general increase in the willingness to share data (and thus engage in Open Science).

Unskilled But Aware: Rethinking The Dunning-Kruger Effect

As a math professor who teaches students to use data to make informed decisions, I am familiar with common mistakes people make when dealing with numbers. The Dunning-Kruger effect is the idea that the least skilled people overestimate their abilities more than anyone else. This sounds convincing on the surface and makes for excellent comedy. But in a recent paper, my colleagues and I suggest that the mathematical approach used to show this effect may be incorrect.

Coping with Institutional Complexity and Voids: An Organization Design Perspective for Transnational Interorganizational Projects

Institutional complexity occurs when the structures, interests, and activities of separate but collaborating organizations—often across national and cultural boundaries—are not well aligned. Institutional voids in this context are gaps in function or capability, including skills gaps, lack of an effective regulatory regime, and weak contract-enforcing mechanisms.

Maintaining Anonymity In Double-Blind Peer Review During The Age of Artificial Intelligence

The double-blind review process, adopted by many publishers and funding agencies, plays a vital role in maintaining fairness and unbiasedness by concealing the identities of authors and reviewers. However, in the era of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data, a pressing question arises: can an author’s identity be deduced even from an anonymized paper (in cases where the authors do not advertise their submitted article on social media)?

Hype Terms In Research: Words Exaggerating Results Undermine Findings

The claim that academics hype their research is not news. The use of subjective or emotive words that glamorize, publicize, embellish or exaggerate results and promote the merits of studies has been noted for some time and has drawn criticism from researchers themselves. Some argue hyping practices have reached a level where objectivity has been replaced by sensationalism and manufactured excitement. By exaggerating the importance of findings, writers are seen to undermine the impartiality of science, fuel skepticism and alienate readers.

Five Steps to Protect – and to Hear – Research Participants

Jasper Knight identifies five key issues that underlie working with human subjects in research and which transcend institutional or disciplinary differences.

New Tool Promotes Responsible Hiring, Promotion, and Tenure in Research Institutions

Modern-day approaches to understanding the quality of research and the careers of researchers are often outdated and filled with inequalities. These approaches […]

There’s Something In the Air…But Is It a Virus? Part 1

The historic Hippocrates has become an iconic figure in the creation myths of medicine. What can the body of thought attributed to him tell us about modern responses to COVID?

Alex Edmans on Confirmation Bias

n this Social Science Bites podcast, Edmans, a professor of finance at London Business School and author of the just-released “May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – And What We Can Do About It,” reviews the persistence of confirmation bias even among professors of finance.

Alison Gopnik on Care

Caring makes us human. This is one of the strongest ideas one could infer from the work that developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik is discovering in her work on child development, cognitive economics and caregiving.

Tejendra Pherali on Education and Conflict

Tejendra Pherali, a professor of education, conflict and peace at University College London, researches the intersection of education and conflict around the world.

Gamification as an Effective Instructional Strategy

Gamification—the use of video game elements such as achievements, badges, ranking boards, avatars, adventures, and customized goals in non-game contexts—is certainly not a new thing.

Harnessing the Tide, Not Stemming It: AI, HE and Academic Publishing

Who will use AI-assisted writing tools — and what will they use them for? The short answer, says Katie Metzler, is everyone and for almost every task that involves typing.

Immigration Court’s Active Backlog Surpasses One Million

In the first post from a series of bulletins on public data that social and behavioral scientists might be interested in, Gary Price links to an analysis from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Webinar Discusses Promoting Your Article

The next in SAGE Publishing’s How to Get Published webinar series focuses on promoting your writing after publication. The free webinar is set for November 16 at 4 p.m. BT/11 a.m. ET/8 a.m. PT.

Webinar Examines Open Access and Author Rights

The next in SAGE Publishing’s How to Get Published webinar series honors International Open Access Week (October 24-30). The free webinar is […]

Ping, Read, Reply, Repeat: Research-Based Tips About Breaking Bad Email Habits

At a time when there are so many concerns being raised about always-on work cultures and our right to disconnect, email is the bane of many of our working lives.

New Dataset Collects Instances of ‘Contentious Politics’ Around the World

The European Research Center is funding the Global Contentious Politics Dataset, or GLOCON, a state-of-the-art automated database curating information on political events — including confrontations, political turbulence, strikes, rallies, and protests

Matchmaking Research to Policy: Introducing Britain’s Areas of Research Interest Database

Kathryn Oliver discusses the recent launch of the United Kingdom’s Areas of Research Interest Database. A new tool that promises to provide a mechanism to link researchers, funders and policymakers more effectively collaboratively and transparently.

Watch The Lecture: The ‘E’ In Science Stands For Equity

According to the National Science Foundation, the percentage of American adults with a great deal of trust in the scientific community dropped […]

Watch a Social Scientist Reflect on the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

“It’s very hard,” explains Sir Lawrence Freedman, “to motivate people when they’re going backwards.”

Dispatches from Social and Behavioral Scientists on COVID

Has the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic impacted how social and behavioral scientists view and conduct research? If so, how exactly? And what are […]

Contemporary Politics Focus of March Webinar Series

This March, the Sage Politics team launches its first Politics Webinar Week. These webinars are free to access and will be delivered by contemporary politics experts —drawn from Sage’s team of authors and editors— who range from practitioners to instructors.

New Thought Leadership Webinar Series Opens with Regional Looks at Research Impact

Research impact will be the focus of a new webinar series from Epigeum, which provides online courses for universities and colleges. The […]

- Impact metrics

- Early Career

- In Memorium

- Curated-Collection Page Links

- Science communication

- Can We Trust the World Health Organization with So Much Power?

- Melissa Kearney on Marriage and Children

- True Crime: Insight Into The Human Fascination With The Who-Done-It

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Gender gaps in research productivity and recognition among elite scientists in the U.S., Canada, and South Africa

Creso sá.

Department of Leadership, Higher, and Adult Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Summer Cowley

Magdalena martinez, nadiia kachynska, emma sabzalieva, associated data.

Data sharing is restricted by the University of Toronto Institutional Review Board for privacy and confidentiality reasons. Data can be shared upon request directed to [email protected] .

This study builds upon the literature documenting gender disparities in science by investigating research productivity and recognition among elite scientists in three countries. This analysis departs from both the general comparison of researchers across organizational settings and academic appointments on one hand, and the definition of “elite” by the research outcome variables on the other, which are common in previous studies. Instead, this paper’s approach considers the stratification of scientific careers by carefully constructing matched samples of men and women holding research chairs in Canada, the United States and South Africa, along with a control group of departmental peers. The analysis is based on a unique, hand-curated dataset including 943 researchers, which allows for a systematic comparison of successful scientists vetted through similar selection mechanisms. Our results show that even among elite scientists a pattern of stratified productivity and recognition by gender remains, with more prominent gaps in recognition. Our results point to the need for gender equity initiatives in science policy to critically examine assessment criteria and evaluation mechanisms to emphasize multiple expressions of research excellence.

Introduction

There is growing recognition in science policy debates of the interplay between gender, research productivity, and recognition in academic science [ 1 , 2 ]. Gender gaps are well documented in the participation of women in the scientific workforce, in their progression through senior and leadership positions, in earning grants and awards, in publication and citation rates, and in the length of their research careers [ 3 – 7 ]. A recent meta-analysis shows persistent gaps in research productivity and impact between man and women, and some evidence of gender bias in the assessment of research records [ 8 ]. Studies show that women in science are under-cited [ 4 , 9 , 10 ], under-paid [ 9 ], under-promoted [ 3 ] and professionally under-recognized [ 6 , 11 ] relative to their male counterparts. Moreover, relatively few women reach senior positions despite the growing number of women moving into doctoral studies and academic careers [ 3 , 7 , 12 ]. Gender inequalities continue to persist despite a number of policy initiatives and instruments at national levels aimed at redressing them [ 12 – 14 ].

In light of these disparities, scholars have questioned the meritocratic assumptions undergirding policy initiatives aimed at promoting research excellence [ 15 – 19 ]. Some highlight the role of explicit and implicit biases in the assessment of otherwise similar careers, indicating that women tend to get less recognition than men for similar research records [ 20 , 21 ]. Others contend that the metrics used to gauge research performance are unfair towards women [ 22 – 24 ]. Awareness of these issues has prompted science policy initiatives in multiple countries. In Canada, the low representation of women among government-funded research chair holders has motivated reviews and policy measures to address gender equity [ 2 , 25 ]. The promotion of gender initiatives in science has been a vital part of the European Union’s research policy for the last two decades, with a number of special projects funded by the EU to address the gender gap in science at different levels [ 1 ]. Despite many policy intentions and initiatives, the unequal recognition of scientific performance among male and female scientists is still prevalent in science [ 26 ].

Speaking to this problem, a few studies find gender gaps among the most productive scientists in their fields [ 27 ]—gaps which in some cases can be higher than for the general population of researchers [ 28 , 29 ]. Some studies showing that men are disproportionally represented among the most prolific researchers in STEM disciplines suggest that women may have to accumulate more knowledge, resources, and social capital to overcome biases and achieve similar publication rates as their male counterparts [ 29 ]. These studies tend to define “star scientists” by high publication and citation rates, invariably finding men to be overrepresented in this rarified segment of the population of researchers. Hence, by definition, elite scientists in these studies are those identified by the outcome variables used to measure productivity and recognition.

This study extends these efforts by considering the meaningful role of career stratification in academia. Prevalent approaches in the literature on gender and research productivity have in some ways ignored important markers of stratification in scientific careers. Generally, studies investigate large samples of researchers by drawing on bibliometric datasets and comparing all authors with publication records (see [ 8 ] for a comprehensive meta-analysis). These studies largely ignore the material and symbolic resources researchers draw from in their research careers, which accrue from being affiliated to high-status institutional settings and holding prestigious academic appointments [ 30 – 32 ]. As these appointments are less accessible to women on average, these need to be accounted for in explanations of gender gaps among scientists who are considered “elite”.

To consider the stratification of academic careers, this study departs from the usual approach of using bibliometric databases to define the sample of researchers to be investigated and identifying elites by high publication and citation rates. Instead, we chose a type of academic distinction that could be used to identify elite scientists as judged by peers across national settings: research chairs. Previous studies identified productivity gains among scientists selected and funded as chairs in comparison to non-chairs [ 33 , 34 ]. Sampling research chair holders allows us to isolate men and women who have been recognized as productive and meritorious scientists. As part of the general gender gap in science concerns the lower rate at which women achieve senior research positions, studying chairs minimizes that source of difference between men and women and allow us to investigate potential disparities in productivity and recognition among elite scientists.

In this paper we explore how the advantages of holding research chairs intersect with gender–do differences in productivity and recognition between men and women that have been described in previous studies hold among elite scientists who enjoy the resources and status of chairholders? To form our sample, we selected government-funded research chair programs in operation for at least five years that aim to recruit and retain senior scientists. We identified suitable programs in Canada, South Africa and in the US states of Georgia, Florida, and Kentucky. Subsequently, we created a unique, hand-curated dataset including 237 chairs and a control group of 706 non-chair peers identified from the same academic departments.

As the length of research careers is an important confounding variable in research productivity and recognition [ 7 ], our study focuses on research output over the five-year period following the appointment of research chairs. With this approach we sought to determine whether gender remains a factor in productivity and recognition during periods in the academic careers of elite scientists when they are expected, as a function of their appointments as research chairs, to be at their peak. Furthermore, we use the control group of peers to verify whether any similarities or differences between genders are unique to elite scientists. Our results show a persistent pattern of stratified productivity and recognition, which is consistent with the literature and yet intriguing considering the expected effects of prestigious academic appointments and resources on scientific careers.

Conceptual framework

Our study is grounded in the sociology of science that has examined the relationships between social structures and research activity. One of the central contributions of sociologists of science is the investigation of how the reward system in science determines research productivity. In the idealized ‘Mertonian’ world of scientific research [ 35 , 36 ], scientists are motivated by being the first to communicate an advance in knowledge and by getting the recognition awarded by the scientific community in the form of publications, citations and prizes. Peer recognition is the basic form of social reward in science from which other extrinsic rewards may be consequential, such as salary increases, career promotion and research funds, all of which usually progress in accordance with the degree of recognition achieved [ 37 ]. Thus, sociologists argue that the recognition and validation of researchers’ contributions to their field are crucial determinants of research productivity [ 36 , 38 , 39 ]. We frame our focus on research chairs as elite scientist through the concept of cumulative advantage.

Cumulative advantage and stratification in science

The phenomenon when more productive scientists get more recognition that supports their further productivity has been introduced by Merton as the principle of cumulative advantage [ 40 ]. His discussion of the ‘Matthew effect’ explains how the stratification in science unfolds when, for a variety of reasons, researchers tend to choose their readings on the basis of an author’s reputation and, as a result, two publications of equal merit will be unequally recognised. Overtime, the growing prevalence of ‘Big Science’ has had an impact on the dynamics of recognition in many disciplines. Scientists connected to large scale research consortia tend to reap the benefits of higher citation rates, although authorship contributions become increasingly difficult to assess [ 41 , 42 ]. Nonetheless, the principle of cumulative advantage has been a dominant theme in the studies of stratification in science. The widespread acceptance of the cumulative advantage hypothesis has been explained by its applicability in examining inequality of productivity and recognition in science [ 43 – 45 ].

The ‘Matthew effect’ has been confirmed through numerous empirical studies on scientific careers [ 46 – 49 ]. A recent study analyzed why scientists with similar backgrounds and abilities often end up achieving very different degrees of success, using data from a large academic funding program [ 50 ]. The results show that “winners just above the funding threshold accumulate more than twice as much funding during the subsequent eight years as nonwinners with near-identical review scores that fall just below the threshold” [ 50 ].

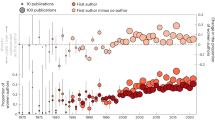

The gender gap in scientific productivity and recognition

As noted in the introduction, the literature has long documented the ‘productivity puzzle’ [ 51 ] whereby women publish less and are less cited than men [ 44 , 52 – 54 ]. The lower recognition and misattribution of work by female scientists, called the “Matilda Effect”, a phenomenon documented throughout history [ 55 ]. A recent meta-analysis suggests that the research productivity gap has remained consistent over generations since the mid-twentieth century [ 8 ]. Others have recently found that the growing participation of women in science over the past 60 years was accompanied by an increase of gender differences in research performance [ 7 ]. By reconstructing the publication history of over 1.5 million authors from 83 countries and 13 disciplines whose publishing career ended between 1955 and 2010, the study found that 35% of all active authors in 2005 were women comparing to only 12% of those in 1955. At the same time, the gender gap in total productivity rose from nearly 10% in the 1950s to around 35% gap in the 2000s [ 7 ]. Research also shows that the scientific awards won by women tend to be lower status [ 6 ].

The persistent evidence that men publish more than women throughout their careers has stimulated research looking for possible explanations. Thus, sociological research on academia suggests various factors which may explain gendered productivity and recognition: differences in family responsibilities [ 56 , 57 ]; different time use patterns as women dedicate more time to serve on committees, teaching and mentoring students [ 58 – 60 ]; unequal resource allocation [ 61 ]; different patterns in academic collaboration and networking [ 11 , 48 , 62 ]; and gender bias in peer-review [ 63 ]. The literature documents various forms of gender stratification in academic careers [ 6 ]. Previous descriptions of changes in the representation of women in science over time point to their increased presence at lower-ranking positions, holding less-prestigious awards, and working in marginalized subdisciplines that receive less funding and lower recognition [ 3 , 4 , 6 ]. So, despite an increase of women in the “pipeline” of scientific disciplines, stratification manifests in the niches and career levels they reach [ 5 ]. These social differences reflect the unequal accumulation of advantage among men and women in academia, which help explain gender differences in scientific careers [ 51 ].

This study frames research chairs as a source of advantage, as it provides material and symbolic resources to their holders who are already recognized and productive researchers. As such, they reinforce their reputation and support further scientific achievement. A focus on research chairs allows us to identify scientists of both genders who have undergone peer selection processes that designate them as part of an academic elite. These processes are arguably qualitatively and expert-based, as research chairs are usually vetted by search committees and their appointment is regulated by norms emphasizing research excellence.

Thus, we sought to identify research chair programs in different contexts to establish a sampling frame of chairholders. We focused on programs aimed at recruiting mid- to senior-level researchers in the sciences for long-term or permanent positions at the host university, employing “excellence”-related criteria. We selected two national policy initiatives—the Canada Research Chairs programs and the South Africa Research Chairs Initiative, and three state-level programs-the Georgia Research Alliance, the Kentucky Endowment Match program, and the endowment match program in the state of Florida.