- Hankering for History

Hanker: To have a strong, often restless desire, in this case for–you guessed it–history!

Is The King’s Speech Historically Accurate?

I will start by saying that The King’s Speech is an exceptional movie. I took the opportunity to see this movie in theaters when it first came out, in 2010. There is a reason that this movie, starring Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush, received four Oscar awards (and was nominated for another eight) [1]; unfortunately, that reason was not because of the historical accuracy of the film.

It is no secret that many of the details in this movie have been skewed and exaggerated. Hugo Vickers, a royal adviser to film, stated that he understands that the adjustments were necessary to make an entertaining movie. He also believed that correct details are important, however, for this particular movie the “essence of the story” is what was most important.

“My view is that a film is a film, and you have to move the drama on…It’s the essence of the story that counts, and the essence of the story here is very sound indeed.” [2] -Hugo Vickers (1/9/2011)

So while the movie wasn’t completely honest, it got out its message. As I look into the historical accuracy–or lack of historical accuracy–in this film, I run across article after article crying foul. Slate’s review of the film is entitled Churchill Didn’t Say That – The King’s Speech is riddled with gross falsifications of history . The Washington Post reviews the movie as “ Brilliant filmmaking, less-than-brilliant history .” My favorite article title is from New Republic; the headline of their article was simple– Royal Mess . However, the article with the hardest-hitting, historical-correcting blows comes from The Daily Beast. Their article, The King Who Couldn’t Speak , is a well-written piece by British historian Dr. Andrew Roberts. Dr. Roberts claims that the film “gets the story all wrong and is simply bad history.”

Dr.Andrew Roberts noted that,

“…viewers should know of the very many glaring and egregious inaccuracies and tired old myths that this otherwise charming film unquestioningly regurgitates.” [3] -Dr. Andrew Roberts (11/20/2010)

Some of the more egregious historical inaccuracies from his lists are:

- The time period of the movie. The speech therapist, Lionel Logue, started working with King George VI in 1926, not in 1930’s.

- The severity of his stutter. King George’s stutter was relatively mild compared to the movie’s portrayal.

- The politics. An example of this would be Winston Churchill. Winston Churchill is shown as supporting the Abdication of George VI’s elder brother King Edward VIII, whereas he violently opposed it.

While the list of smaller inaccuracies are too many to list, The King’s Speech, overall is excellent! As far as my moviegoing experience, The King’s Speech was so impressive that I can overlook the “egregious inaccuracies and tired old myths.” I highly recommend that you take the opportunity to watch this film. If you want a more detailed account of historical discrepancies, I suggest checking out the full article that I mentioned above from The Daily Beast.

[1] IMDb: Awards for The King’s Speech

[2] The Guardian: How historically accurate is The King’s Speech?

[3] The Daily Beast: The King Who Couldn’t Speak

More Stories

How sparta and rome influenced hitler and the nazis.

- People & Places

Why did FDR Serve 4 Terms as President?

- The History of...

The History of Harvard University

5 thoughts on “ is the king’s speech historically accurate ”.

This is why historians are historians and dramatists dramatists. Can’t we all get along? I am disappointed in the attitude of ”oh well, its for a good story”. No. We can tell great stories that are accurate. History is full of interesting stories. The Churchill mistake is inexcusable. Great Post, Grant!

this finna be a bruh moment Front?

you suck big weenis

Thats a funny one, i hate this film

Sucks big Weenis

Comments are closed.

You may have missed

Exploring What Is the Oldest Civilization: A Journey Through Ancient History

Who Was Pocahontas?

What Was the Battle of the Bulge?

Truth and Fiction in ‘The King’s Speech’

Historians and critics charge that George VI was a nitwit and a Nazi appeaser

On the heels of its 12 Academy Award nominations , “The King’s Speech,” an inspiring story of King George VI and his triumph over stuttering, is being criticized for historical inaccuracies.

It’s as predictable as the Oscars themselves. A new front-runner often means some fresh round of attacks, and the charge of historical distortion is a perennial one.

In this case, intellectual gadfly Christopher Hitchens and the New York Review of Books’ Martin Filler are charging that the monarch in question was no better than a Nazi appeaser and, in Filler’s words, “a nitwit.” They paint a portrait of the wartime king that is far different from the shy family man essayed by Oscar nominee (and favorite) Colin Firth.

“‘The King's Speech’ …perpetrates a gross falsification of history,” Hitchens wrote on Slate on Monday, saying the king was not worthy of hagiography. Fillers says the king had an uncontrollable temper and even struck his wife.

But Hugo Vickers, a historian who consulted on the film and author of a biography on the Queen Mother, disagreed: “He was a humble man and a courageous man and he was called upon to do a job for which he had not been trained,” he told TheWrap.

He said the depiction of a man struggling to overcome a crippling speech impediment is accurate.

The filmmakers themselves declined to comment, but have said publicly that the movie was carefully researched.

The appeasement charge stems from the king’s decision to pose with Neville Chamberlain on the balcony of Buckingham Palace after the prime minister negotiated the Munich Agreement with Hitler in 1938 (a fact that the movie skirts over).

Whether George VI’s evolving views of the threat of Nazism should be defined solely by that photo-op with Chamberlain are at the heart of the current debate. Historians and journalists sympathetic to the film say the criticism is overly simplistic.

When war came, King George VI and his wife bravely remained in London even as the blitzkrieg raged. It was his brother, Edward, they say, who was known to have Nazi sympathies, while the king eventually rallied the country – as the film depicts – to meet the threat of war.

And anyway, they add, the film is about stuttering, and not wartime politics.

Filler goes further than the acerbic Hitchens, emphasizing George VI’s personal deficits as much as the king’s leadership deficiencies.

“‘The King’s Speech’ doesn’t dwell on George’s limited intellectual capacities, but many who dealt first-hand with him did,” Filler wrote in the New York Review of Books .

For journalists such as Harold Evans, who reminisces about a wartime George VI in his book “My Paper Chase: True Stories of Vanished Times,” Hitchens and Filler misinterpret the king’s legacy. He also maintains that Hitchens’ anti-monarchist beliefs have colored the social critic’s view of history.

“It is hard for Americans to understand the atmosphere in England in the thirties. Everyone had lost a cousin or had a relative killed in World War I. They were horrified that we’d go back to war again,” Evans told TheWrap.

“It’s not a film about appeasement. It’s a film about the struggle of a man to overcome a great handicap,” he added.

Or is it just about Oscar politics?

Among Oscar campaigners, the articles by Hitchens and Filler are suspiciously timed – coming directly after the Weinstein Company film dominated the Oscar nominations, which followed an upset win at the Producers Guild Awards on Saturday.

For months critics have harped that “The Social Network” gets the story of Facebook’s founding gravely wrong.

Complaints about Hollywood biopics playing fast and loose with the facts are a staple of Oscar races (and are often gleefully passed along by rival films’ camps), and this season is shaping up to be no different.

In the case of “Network,” critics have chirped that the David Fincher overstates the importance of Harvard eating clubs to Mark Zuckerberg and the seminal role a painful breakup played in the creation of Facebook.

Last week at a Digital Life Design conference in Munich, Sean Parker, the Napster co-founder and Facebook executive played by Justin Timberlake in the movie, “a complete work of fiction.”

In his Golden Globes acceptance speech, “Network” screenwriter Aaron Sorkin seemed to answer those critiques by saying he was using Zuckerberg as a metaphor.

In past years, Oscar candidates such as “A Beautiful Mind,” “Saving Private Ryan” and “The Queen” have been similarly bedevilled by charges of inaccuracy.

Nor are these the first times that the portrait of King George VI painted in “The King’s Speech” has been called into question.

Just days after the film began its limited release, Andrew Roberts in The Daily Beast , griped about the “…very many glaring and egregious inaccuracies and tired old myths that this otherwise charming film unquestioningly regurgitates.”

However, this latest set of slams are particularly trenchant.

In addition to griping about George VI’s wartime leadership, Filler and Hitchens contend that the movie misrepresents the relationship between Winston Churchill and the monarch. In the film, Churchill is depicted as pushing for the abdication of Edward VIII, so that the king can marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson.

In reality, Churchill fiercely opposed the decision, and his support for Edward VIII initially led to a frosty relationship with his successor.

Splitting hairs, say those who endorse the film’s version of history.

“If this were a documentary, rather than a theatrical release, I’d be the first to complain,” Evans said, adding, “I feel irritated by this attempt to make a political point with something that is an inspirational film.”

Perspective: How true is ‘The King’s Speech’?

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

If any best-picture contender was going to face questions about taking liberties with the facts this Oscar season, it seemed likely it would be “The Social Network.” But now that screenwriter Aaron Sorkin and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg have tactfully retreated a bit from their initially contentious stands, the accuracy debate has shifted to “The King’s Speech.”

“The King’s Speech” is being sold as a feel-good tale of how a friendship between a royal and a commoner affected the course of history. But some commentators are complaining, among other things, that the film covers up Winston Churchill’s support for Edward VIII, the playboy king who abdicated to marry an American divorcee, and that the movie fails to acknowledge that the once tongue-tied George VI supported Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of the Nazis. (Writing last month at slate.com, Christopher Hitchens blasted the film as “a gross falsification of history.”)

As a specialist in British history, I agree that screenwriter David Seidler certainly has tweaked the record a bit and telescoped events in “The King’s Speech” — but for the same artistic reasons that have guided writers from Shakespeare to Alan Bennett, who wrote the screenplay for “The Madness of King George” (and the play on which the movie was based). While historians must stick to the facts, dramatists need to tell a good story in good time. It also helps if they can explore the human condition in the process.

Seidler’s script opens with Colin Firth as Prince Albert (the future King George VI, but then the Duke of York and known to his family as “Bertie”) facing the ordeal of making his first radio broadcast. To add to the strain, the duke must deliver the address in a stadium before a large crowd. However, his words come only haltingly, causing embarrassment for all present. Not shown but later referenced in the film is the fact that in the crowd was Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), a speech therapist recently transplanted from Australia.

All this took place in 1925, but Seidler brings the speech disaster forward 10 years to the eve of the abdication crisis, which resulted in the duke unexpectedly being transformed into a king when his brother Edward VIII stepped aside. The compression of events, although understandable, requires a slew of historical alterations to explain the back story.

The duke’s stammer derived in part from the verbal abuse he received as a child from his father, King George V (Michael Gambon). To indicate this, Seidler concocts a scene showing the adult Bertie still being hectored by his father, and it is only after this that he agrees to see Logue.

Much of the early part of the film is taken up with Logue’s struggle to win the duke’s trust. The therapist succeeds partly by trickery and partly because of continued prompting by Bertie’s wife, the Duchess of York (Helena Bonham Carter). After achieving a “breakthrough” with his patient and following Edward’s abdication in 1936, Logue helps prepare the new king for the ordeal of the coronation ceremony. That hurdle cleared, the film culminates with the therapist coaching Bertie through another historic moment: his broadcast to the British Empire at the start of World War II with an approving Churchill (Timothy Spall) looking on.

In reality, the duke first sought treatment from Logue in 1926, and, contrary to the film, the two hit it off immediately. Logue wrote in a note later published in the king’s official biography that Bertie left their first meeting brimming with confidence. After just two months of treatment, the duke’s improvement was significant enough for him to begin making successful royal tours with all the public speaking that entailed. George V was so delighted that Bertie rapidly became his favored son and preferred heir.

In interviews, Seidler has been ambiguous about what sources he consulted in writing the script. The various biographies of George VI all tell of the king’s relationship with Logue. This includes the official biography published in 1958. John Wheeler-Bennett, the royal biographer personally selected by the king’s widow, was himself a former patient of Logue’s and so wrote about the episode with great emotion.

It remains unclear, though, to what extent sources not available to scholars or the public played a role in the final shape of the film. Seidler has said that Logue’s son offered 30 years ago to show him his father’s notebooks, provided the king’s widow agreed. But when Seidler wrote Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, he was told that she found it too painful to remember the old anguish and begged that he wait until she had passed away.

Although the Queen Mother died in 2002, filmmakers said they were provided with Logue’s diaries, notes and letters only shortly before filming began. Seidler has not specified how material from Logue’s records was used, but he has said that research guided him to the conclusion that Logue utilized Freud’s “talking cure” approach. Thus, by reading up on the king’s life, Seidler used what he terms “informed imagination” to create the film’s therapy scenes.

Seidler also drew on personal experience: He himself stammered as a child, and it was this that led him to an interest in George VI. From what he has said about his own successful treatment, Seidler indicates that he projected that experience into his fabrication about Logue having to work patiently to gain Bertie’s trust. This liberty with the truth certainly gives the film more dramatic interest.

There are many other instances of artistic license in “The King’s Speech.” For example, Bertie chose his regal cognomen, George, out of respect for his father and not as the film has it because Churchill suggested that Albert sounded “too German.” Another dramatic fantasy occurs when the Archbishop of Canterbury (Derek Jacobi) breathlessly revealed that Logue was not in fact a doctor. In reality, Logue’s credentials were never misrepresented. Bertie always referred to him as “Mr. Logue” or simply “Logue.” Logue’s grandchildren recently came forward to say that their grandfather never used Christian names with the king at all — despite the movie making a strong point that the future king bristled at being called “Bertie” by Logue.

As for Hitchens’ allegations, they are much ado about nothing. Churchill’s support of Edward VIII owed more to his near-medieval reverence for the monarchy than it did to the individual occupying the throne. In supporting the appeasement policies of Chamberlain, George VI acted in harmony with the overwhelming majority of the British population across the political spectrum. As a combat veteran of World War I, the king was as anxious as his subjects to avoid a second conflict by any promising means. George VI was also at one with most Britons in remaining skeptical about Churchill as prime minister until the great man had proved himself.

Hitchens will get a second chance to scrutinize moviedom’s portrayal of Edward VIII and George VI this year, when Madonna’s film “W.E.” — about Wallis Simpson and Edward — hits theaters. He’s probably already stocking up on pencils.

Freeman teaches history at California State Fullerton.

More to Read

‘Scoop’ depicts Prince Andrew’s infamous interview. These were the women behind it

April 5, 2024

Kate’s remarkable video was a Royal revolution, scepter-spinning in its frankness

March 24, 2024

David Seidler, ‘The King’s Speech’ screenwriter, dies at 86

March 17, 2024

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Maya Rudolph slays on ‘Saturday Night Live’ in a Mother’s Day-themed episode

Carlos Amezcua: Sam Rubin was a giant personality, and my friend

May 11, 2024

Company Town

Shari Redstone was poised to make Paramount a Hollywood comeback story. What happened?

Netflix is in the running for NFL Christmas games

May 10, 2024

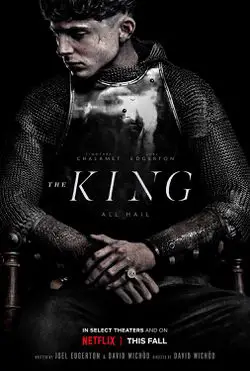

The True Story Behind "The King's Speech"

"The King's Speech" is a 2010 dramatic biographical film, recounting the friendship between King George VI of England and his Australian speech therapist, Lionel Logue. The film also covers Edward VIII's 1936 abdication, and George VI's subsequent coronation and shouldering of responsibility during World War II. George VI ultimately must conquer his stammer to assist and guide Britain during the war.

As a film, "The King's Speech" takes a few liberties with the historical timeline and in regards to simplifying certain characters. One element historians took particular umbrage with was the depiction of Winston Churchill . However, overall it is fairly faithful to the historical record. For one thing, George VI really did have a speech impediment since the age of eight, and Lionel Logue did work with him for several years. They did stay friends until they both died. Certain scenes, such as George VI's coronation, were praised for their accurate recapturing of the feel of the 1930s.

The main concept the film changed was simply adding drama to certain scenes, such as the speech announcing war with Germany towards the end. It also condensed the historical timeline significantly, shortening events. This was mostly done for the sake of keeping the narrative moving. Overall, however, " The King's Speech " is a fairly accurate, heartwarming rendering of George VI and Lionel Logue's friendship.

Prince Albert had a stutter as a child

Prince Albert, later George VI, developed a stutter when he was eight that he carried through to his early adult life. His parents were not terribly affectionate with him, and he was susceptible to tears and tantrums – traits he also carried through his adult years, writes Biography . Given that many of his public duties required speeches, Albert needed to – and worked tirelessly – to fix his stammer with multiple doctors and therapists, writes Stuttering Help . He wasn't successful with any speech therapies until he worked with elocutionist and informal speech therapist Lionel Logue, beginning in the 1920s.

When Logue saw the then-Duke of York give a speech, he said to his son, "He's too old for me to manage a complete cure. But I could very nearly do it. I'm sure of that." (via Stuttering Help ). He was right, and his positive attitude helped the duke recover from previous failures that had made him believe the problem caused him to be mentally deficient instead of simply physically injured. Despite how long they worked together, the duke's speech issues had more to do with how held his jaw and pronounced words; the result was that his stammer was mainly cleared up in a matter of months as opposed to years.

Lionel Logue was a self-taught speech therapist

Lionel Logue was an Australian speech therapist who, not being formally trained, used methods he had discovered and created on his own. He worked as an elocutionist first, but fell into helping Australian World War I veterans with speech defects, writes The ASHA Leader . No one else was doing what he was with the veterans, and speech therapy and audiology programs didn't even get off the ground until the 1940s (via UNC Health Sciences Library ). Logue was even a founder of the College of Speech Therapists.

Just before World War I, Logue worked a variety of jobs as a teacher of elocution and drama, theater manager, and reciter of Shakespeare and Dickens (via Speech Language Therapy's Caroline Bowen, a speech language pathologist ). Logue worked with patients on their speech, but also on confidence and the self-belief that they could accomplish what they set out to do. He was empathetic with his patients, and learned from each case he worked on. Logue originally tried out as an actor, and as a result, his manner was somewhere between a teacher and an artist. He was serious about his life's work and resolved to avoid cheapening it by writing a book about his efforts with the king.

Logue began working with Prince Albert in 1926

Elizabeth, the Duchess of York, first encouraged her husband to work with Lionel Logue, though the meeting as depicted in the film between Elizabeth and Logue likely didn't happen (via Logue and Conradi's "The King's Speech" ). Logue thus began working with the Duke of York in October 1926, soon after he opened his London practice on Harley Street. Logue first diagnosed the Duke with, according to CNN , acute nervous tension and the habit of closing the throat, which caused him to clip words out.

Logue met with him daily for the next two or three months (in advance of a visit to Australia), and his stammer was gone (for the most part) within that time frame; it didn't take years of treatment (via Speech Language Therapy ). Unlike in the film, in reality, the Duke and Logue weren't necessarily aiming for complete fluency. However, they did continue to work together for the next two decades, mainly on the royal's speeches.

Logue worked with Albert for over 15 years

Though the film condenses the timeline to make it seem as though everything takes place over just a few years, Logue and Albert worked together for decades (via CNN ). "The King's Speech" begins in 1925 with the close of the British Empire Exhibition, which would be historically accurate, but time simply speeds by until the film depicts the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936 and later the outbreak of war in 1939 in just a few hours; it doesn't really feel as though a decade and a half have passed.

Regardless, Logue and the duke worked together on speeches even after the duke had mostly mastered his stammer. Lionel Logue's methods were unorthodox and primarily self-taught. He never specifically said what course of treatment he worked on with the duke, saying, according to The ASHA Leader : "...on the matter of Speech Defects, when so much depends on the temperament and individuality, a case can always be produced that can prove you are wrong. That is why I won't write a book." Much of the ideas for the therapy sessions depicted in the film come from Logue's diaries (though plenty of the dialogue was invented), which were inherited by his grandson Mark. They were used in the film, though the director only saw them late in the film's production.

Any sort of therapy is inherently individual, not to mention personal (via Psychiatric Times ). It's no wonder that Logue decided to avoid writing about his work.

Wallis Simpson was a more complex person than the film indicates

King Edward VIII was crowned in January 1936 and abdicated in December of the same year in order to marry Wallis Simpson , who had been twice divorced (via History ). His younger brother was proclaimed king the next day. The film is sympathetic to George VI and Elizabeth, and Wallis Simpson is cast as a vaguely Nazi-supporting villain; there is little depth to her character. However, her life and motivations were shrouded in rumors from the British upper classes and the media.

The upper classes, who learned about the Edward-Wallis romance before the British media, in particular saw her as an uncouth American divorcee, and had a hard time figuring out why Edward wanted to be with her. When the media did find out, in December 1936, she was both ruined and revered by them, according to History Extra . However, after moving overseas more-or-less permanently she faded from the spotlight. Her unfortunate reputation from the nobles stuck with her.

Ultimately, George VI didn't allow his brother and sister-in-law, who had moved to France, to be productive for the royal family; they asked multiple times for jobs and were denied (via History Extra ). Awful rumors followed Wallis Simpson even past her death in the 1980s, including one that stated she would do anything to become queen of England. Though it's clear both on and off screen that she and Elizabeth disliked each other, Wallis was more than a king-stealing villain.

Churchill was actually opposed to Edward VIII's abdication

One major element of the film that historians had trouble with is Churchill's abrupt support of George VI, writes Daily History . In real life, he encouraged Edward VIII not to abdicate in 1936, and remained a supporter of the royal, believing something could be worked out without having to resort to abdication. George VI and Elizabeth didn't fully support Churchill later in life due to his actions during the abdication. However, Churchill was later knighted by Elizabeth II (via Biography ).

This element is likely written as such for the film due to the writers having a hard time writing someone as beloved as Churchill with actual flaws. The writers of "Saving Mr. Banks" had a similar issue with Walt Disney and his flaws. As a result, it is one of the only concrete historical aspects that left historians scratching their heads in confusion. Everything else that is changed in the film is mainly done for the sake of adaptation, drama, and the good of the narrative. This change seems to be for the sake of preserving Churchill's reputation. Considering the film's lead-up of events to World War II, and Churchill's role in Britain's survival, it isn't that surprising.

King George VI's coronation was less fraught than the film depicts

Logue worked with George VI on his coronation speech in 1937. Five days afterward, the king wrote a heartfelt thank you letter for the assistance (via Tatler ), attributing the success to Logue's "expert supervision and unfailing patience." Just as in the film, Logue and his wife are seated in the royal box, so high up that Myrtle Logue needed to use opera glasses in order to see, writes CNN .

However, by this time, the king had mostly mastered his speech impediment, and the dramatic scene in the film with Logue and St. Edward's chair is likely fictional. It was written for the sake of the narrative of George VI realizing he does have a voice. Reality isn't necessarily so cinematic, and after weeks of working on the speech with Logue, George VI delivered it flawlessly. Regardless, according to Daily History , the film accurately conveys the atmosphere of the 1930s and the coronation of a new king. In reality, the king and Logue likely didn't have the same miscommunication as they do in the film, and it is doubly heartwarming that Logue and his wife were seated with the royal family, just because of the services Logue had rendered the new king.

Logue was more deferential to his royal patient

Geoffrey Rush's portrayal is much more animated than Logue likely was in reality. Logue certainly addressed Prince Albert respectfully, and the scenes of swearing in Logue's office are likely invented. Logue also never referred to the prince by a nickname, much less one used exclusively by the family. They were friends in real life, but their relationship was more realistically distant.

According to CNN , the letters Logue wrote to the king are addressed to "Your Royal Highness". On the other hand, the king signed his letters with his first name, indicating a measure of friendship between the two men. Logue also apparently allowed George VI to set treatment goals due to his position. Though they did end up being friends, Logue never forgot who exactly his patient was, and treated him accordingly (via Daily History ). Historical films always add heart-to-heart speeches between people which probably never actually happened but work for the sake of drama and the narrative. "The King's Speech" is no exception.

The speech announcing war with Germany was less dramatic

Lionel Logue further assisted George VI during the 1939 speech when he announced Britain was at war with Germany. However, Logue wasn't actually in the room with him, as the film depicts, and only wrote notes on places for the king to pause to collect himself when speaking or on which words to stress, according to CNN . Keep in mind that by this point in time, 13 years after meeting Logue, the king had essentially mastered his stammer. George VI also stood to give the speech, though photographs show him in full military uniform and sitting down.

Lionel Logue's diaries also answered a previously unknown question about the speech that was added to the film. George VI stammered on some of the W's in the speech, and according to a comment he made to Logue, it was so the people would recognize him, writes CNN .

The film turns the event into a climactic event, as a culmination of the years of work the king and Logue have put into his affliction – and which the audience has just watched on screen for the past two hours. Also, though it is unlikely the information was revealed at this exact time in real life, the character of Winston Churchill tells the king just before this speech that he, too, was a stammerer as a child, writes The Lancet . This element is true, though it is positioned for the sake of cinematic drama.

George and Logue's friendship didn't fracture over credentials

In the film, coronation preparations pause when the archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Lang, mentions that Logue doesn't have any formal training. Not having known this beforehand, George VI becomes outraged and only calms after Logue provokes him into speaking without stammering, causing him to realize that he actually can speak accurately. This entire element is invented for the film, presumably for the sake of drama (and humor).

By this point, the two men had known each other for over a decade and were friends. Though their relationship was primarily professional, in scouting out Logue's help, the king must have understood his credentials and it didn't bother him; after all, he worked with Logue, voluntarily, for decades (via Daily History ). Logue's formality likely kept their friendship professional enough that they probably had few personal disagreements.

Logue and the king wrote letters back and forth for years; the earlier letters were signed "Albert" and the later letters "George" by the king, according to CNN , indicating a measure of friendship that was likely meted out to few people. When Logue asked the king in 1948 if he would serve as patron of the College of Speech Therapists, George VI immediately agreed and it became known as the Royal College of Speech Therapy, writes The ASHA Leader .

The film has an obvious pro-George VI bias

Due to being written from a historical perspective, "The King's Speech" supports George VI, Logue, Elizabeth, and even Winston Churchill as characters and historical figures much more than it does George V, Edward VIII, or Wallis Simpson. The film has an agenda and a narrative it set out to tell: the story of how George VI overcame his stammer and led a nation successfully through a war.

According to The Gazette , the film's textual inclusion of Logue's appointment as a Member of the Royal Victorian Order is accurate. The king appreciated his services enough to reward him with a title for them, and this element certainly adds to the theme of friendship the film is so fond of.

In another interesting example of bias, however, the film omits Edward VIII's Nazi sympathies entirely, though Simpson is written to seem like an outsider to the royals. This was likely done for the sake of Edward's surviving family, though it was a slightly odd omission considering the context of the film. Edward isn't cast as a villain, however, he doesn't quite seem to realize what he's forcing his brother to step into. Though he immediately supports George, Edward doesn't seem to comprehend the royal family's – and the film's – endless demand of duty.

clock This article was published more than 13 years ago

‘The King’s Speech’: Brilliant filmmaking, less-than-brilliant history

Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me twice, and I must have just watched another British movie based on historical events.

I emerged from the theater enthralled with “The King’s Speech,” nominated for 12 Oscars. Although I was uncertain about the accuracy of Colin Firth’s portrayal of King George VI and his debilitating stammer (as the Brits call it), Firth’s performance was so impressive that it left me with a stutter of my own.

The Golden Globes agreed, giving Firth a best-acting nod. Can Oscar be far behind? Jolly well ought to, I thought as I exited the theater.

Then I ruined it. I mentioned to my wife that I might check some facts. “Don’t spoil it,” she groaned. (Speaking of spoilers, a warning to readers who haven’t seen the film: Continue at your own risk. )

Let’s start with the stammer, which surfaced when “Bertie” (a family nickname) was a child. It’s the most powerful character in the movie. Some films have sexual tension. “The King’s Speech” has stammer tension.

Long before Bertie took the throne upon his brother’s abdication in 1936, he dreaded public speaking. As Duke of York, he could not avoid it. Into Bertie’s terror comes speech therapist Lionel Logue. As they work to conquer the stammer that threatens the king’s reign and his psyche, you want to stand and cheer.

Brilliant filmmaking. Less-than-brilliant history.

Recordings survive of Bertie’s speeches from his earlier years as Duke of York. As British historian Andrews Roberts wrote in the Daily Beast, “They make clear that his problem was nothing so acute as this film makes out.” The tension builds on the back of an altered timeline that turns the stammer into something “so chronic that Colin Firth can hardly say a sentence without prolonged stuttering,” according to Roberts.

Peter Conradi, a Times of London journalist who wrote a companion book to the movie with Logue’s grandson, had access to letters and diaries Logue kept. Conradi’s reply to Roberts is telling: “The King’s Speech may get some historical details wrong, but it’s spot on when it comes to its central point: the closeness of the friendship between King George VI and his unconventional Australian speech therapist.”

Conradi generously offers an example of inaccuracy. “Roberts is right to point out that Tom Hooper, the director, has tinkered with some of the basic facts, such as having Winston Churchill back the abdication of Edward VIII, which put a reluctant Bertie onto the throne in December 1936, whereas Churchill instead spoke out in favor of Edward and his romance with Wallis Simpson.”

Tinker? Recasting Churchill into the opposite role?

Cinematic storytellers often defend the liberties they take with history by saying they are aiming for “emotional truth,” as if the facts won’t yield it. If challenged, they often retreat to Conradi’s final contention: “This never claimed to be a documentary.”

There’s no grand deception here. We all know that movies alter timelines and omit facts for efficiency or dramatic effect. But why bother to do a film about historical events if those events merely become props to be reordered in search of a manipulated “truth?” For many, “The King’s Speech” will probably be the only version of those events they will ever know. The all-too-real stammer provided more than enough material to do a compelling movie.

I should have learned my lesson 30 years ago, when I saw “Chariots of Fire,” the story of two British runners at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

One was Harold Abrahams, a sprinter weighed down by his ethnicity (he was Jewish). Crushed by his decisive loss in the 200 meters, he sets out with an almost blinding determination to redeem himself in the 100 meters. He achieves that goal — for his country, for himself and, the film suggests, for the Jewish people.

Captivated by this unfamilar history, I wanted more. Big mistake.

The film had reversed the order of the two races so Abrahams could lose, then triumph. The “emotional truth” of his determined dash to redemption? A fiction.

Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me twice . . .

Good luck, Colin. You created a great character. I’m rooting for you.

Steve Luxenberg is an associate editor at The Washington Post.

‘The King’s Speech’: Good Drama—but Accurate Science?

Newswise — “The King’s Speech” is a compelling enough story to merit 12 Oscar nominations. (We’ll find out how compelling when the Academy Awards are announced Feb. 27). However, as contentions surface about the film’s historical accuracy (Lionel Logue’s grandson said his grandfather would never call the King of England “Bertie,” and the real-life Churchill, contrary to the film’s portrayal, staunchly opposed Edward VIII’s abdication), what about the film’s depiction of stuttering and Logue’s therapy techniques? Did the film portray them accurately?

“While stuttering and its treatment have been documented for hundreds of years, systematic development of effective treatment methods didn’t really emerge until the late 1940s,” said Doug Cross, associate professor of speech-language pathology and audiology at Ithaca College. “As depicted in the film, stuttering has been treated by using every technique you can imagine, from putting stones in the mouth to signing speech to physical relaxation. In that sense, the movie accurately portrayed the myriad of techniques available at the time, especially for an untrained speech pathologist such as Logue. An impressive part of the film was the way it accurately depicted the important relationship between the mechanical and psychological aspects of speech and stuttering. As much as the field has evolved and specialized since Lionel Logue’s day, most speech-language pathologists agree that focus on integrating the perceptions and emotions that clients experience about themselves and their speech problems with effectively modified mechanics of coordinated speech is an important aspect of treatment.”

Chief among those emotions is fear.

“Fear does not cause stuttering,” Cross said. “The roots of stuttering are complex and multidimensional, but anxiety and fear about becoming stuck on sounds and words and the stigma society often places on stuttering behavior play significant roles in the development and perpetuation of the problem. The more the person tries to hide, prevent or rapidly escape stuttering, the worse the problem becomes, creating a negative cycle of anticipation and struggle. This type of negative anxiety about performance and recovery from mistakes affects stuttering much in the same way it affects many other behaviors we experience in life.”

As it did with George VI, stuttering usually starts between two and six years of age. However, in many cases up to age 12, sufferers experience spontaneous recovery. After 12, though, the chances of spontaneous recovery dramatically decrease.

“Since Lionel Logue’s day, we’ve developed more effective protocols for treating stuttering and its impact on effective communication,” Cross said. “Advances in science and technology, such as brain studies and DNA analysis, tell us about the effects of neuromotor systems on speech patterns; still, there’s no silver bullet to treating stuttering, and there is no cure. I think it would be inappropriate for a speech pathologist to say, ‘We’ve cured stuttering.’ Its causes are much too complex. This concept eventually comes out in the film.”

However, contemporary speech pathologists can help stutterers find their voices, either by designing different methods of speaking that would prevent stuttering or by reducing the stutter to the point where it is no longer a distraction.

“Stuttering is a communication problem that often makes both speakers and listeners extremely uncomfortable and anxious, but at the same time it fascinates them,” Cross said. “I think that might explain why ‘The King’s Speech’ is making such an impact.”

MEDIA CONTACT

Type of article.

- Experts keyboard_arrow_right Expert Pitch Expert Query Expert Directory

- Journalists

- About keyboard_arrow_right Member Services Accessibility Statement Newswise Live Invoice Lookup Services for Journalists Archived Wires Participating Institutions Media Subscribers Sample Effectiveness Reports Terms of Service Privacy Policy Our Staff Contact Newswise

- Blog FAQ Help

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Churchill Didn’t Say That

The king’s speech is riddled with gross falsifications of history..

The King’s Speech is an extremely well-made film with a seductive human interest plot, very prettily calculated to appeal to the smarter filmgoer and the latent Anglophile. But it perpetrates a gross falsification of history. One of the very few miscast actors—Timothy Spall as a woefully thin pastiche of Winston Churchill—is the exemplar of this bizarre rewriting. He is shown as a consistent friend of the stuttering prince and his loyal princess and as a man generally in favor of a statesmanlike solution to the crisis of the abdication.

In point of fact, Churchill was—for as long as he dared—a consistent friend of conceited, spoiled, Hitler-sympathizing Edward VIII. And he allowed his romantic attachment to this gargoyle to do great damage to the very dearly bought coalition of forces that was evolving to oppose Nazism and appeasement. Churchill probably has no more hagiographic chronicler than William Manchester, but if you look up the relevant pages of The Last Lion , you will find that the historian virtually gives up on his hero for an entire chapter.

By dint of swallowing his differences with some senior left and liberal politicians, Churchill had helped build a lobby, with strong grass-roots support, against Neville Chamberlain’s collusion with European fascism. The group had the resonant name of Arms and the Covenant. Yet, as the crisis deepened in 1936, Churchill diverted himself from this essential work—to the horror of his colleagues—in order to involve himself in keeping a pro-Nazi playboy on the throne. He threw away his political capital in handfuls by turning up at the House of Commons—almost certainly heavily intoxicated, according to Manchester—and making an incoherent speech in defense of “loyalty” to a man who did not understand the concept. In one speech—not cited by Manchester—he spluttered that Edward VIII would “shine in history as the bravest and best-loved of all sovereigns who have worn the island crown.” (You can see there how empty and bombastic Churchill’s style can sound when he’s barking up the wrong tree; never forget that he once described himself as the lone voice warning the British people against the twin menaces of Hitler and Gandhi!)

In the end, Edward VIII proved so stupid and so selfish and so vain that he was beyond salvage, so the moment passed. Or the worst of it did. He remained what is only lightly hinted in the film: a firm admirer of the Third Reich who took his honeymoon there with Mrs. Simpson and was photographed both receiving and giving the Hitler salute. Of his few friends and cronies, the majority were Blackshirt activists like the odious “Fruity” Metcalfe . (Royal biographer Philip Ziegler tried his best to clean up this squalid story a few years ago but eventually gave up.) During his sojourns on the European mainland after his abdication, the Duke of Windsor never ceased to maintain highly irresponsible contacts with Hitler and his puppets and seemed to be advertising his readiness to become a puppet or “regent” if the tide went the other way. This is why Churchill eventually had him removed from Europe and given the sinecure of a colonial governorship in the Bahamas, where he could be well-supervised.

All other considerations to one side, would the true story not have been fractionally more interesting for the audience? But it seems that we shall never reach a time when the Churchill cult is open for honest inspection. And so the film drifts on, with ever more Vaseline being applied to the lens. It is suggested that, once some political road bumps have been surmounted and some impediments in the new young monarch’s psyche have been likewise overcome, Britain is herself again, with Churchill and the king at Buckingham Palace and a speech of unity and resistance being readied for delivery.

Here again, the airbrush and the Vaseline are partners. When Neville Chamberlain managed to outpoint the coalition of the Labour Party, the Liberal Party, and the Churchillian Tories and to hand to his friend Hitler the majority of the Czechoslovak people, along with all that country’s vast munitions factories, he received an unheard-of political favor. Landing at Heston Airport on his return from Munich, he was greeted by a royal escort in full uniform and invited to drive straight to Buckingham Palace. A written message from King George VI urged his attendance, “so that I can express to you personally my most heartfelt congratulations. … [T]his letter brings the warmest of welcomes to one who, by his patience and determination, has earned the lasting gratitude of his fellow countrymen throughout the Empire.” Chamberlain was then paraded on the palace balcony, saluted by royalty in front of cheering crowds. Thus the Munich sell-out had received the royal assent before the prime minister was obliged to go to Parliament and justify what he had done. The opposition forces were checkmated before the game had begun. Britain does not have a written Constitution, but by ancient custom the royal assent is given to measures after they have passed through both houses of Parliament. So Tory historian Andrew Roberts, in his definitively damning essay “The House of Windsor and the Politics of Appeasement,” is quite correct to cite fellow scholar John Grigg in support of his view that by acting as they did to grant pre-emptive favor to Chamberlain, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (Colin Firth and Helena Bonham Carter to you) “committed the most unconstitutional act by a British Sovereign in the present century.”

The private letters and diaries of the royal family demonstrate a continued, consistent allegiance to the policy of appeasement and to the personality of Chamberlain. King George’s forbidding mother wrote to him, exasperated that more people in the House of Commons had not cheered the sellout. The king himself, even after the Nazi armies had struck deep north into Scandinavia and clear across the low countries to France, did not wish to accept Chamberlain’s resignation. He “told him how grossly unfairly he had been treated, and that I was genuinely sorry.” Discussing a successor, the king wrote that “I, of course, suggested [Lord] Halifax.” It was explained to him that this arch-appeaser would not do and that anyway a wartime coalition could hardly be led by an unelected member of the House of Lords. Unimpressed, the king told his diary that he couldn’t get used to the idea of Churchill as prime minister and had greeted the defeated Halifax to tell him that he wished he had been chosen instead. All this can easily be known by anybody willing to do some elementary research.

In a few months, the British royal family will be yet again rebranded and relaunched in the panoply of a wedding. Terms like “national unity” and “people’s monarchy” will be freely flung around. Almost the entire moral capital of this rather odd little German dynasty is invested in the post-fabricated myth of its participation in “Britain’s finest hour.” In fact, had it been up to them, the finest hour would never have taken place. So this is not a detail but a major desecration of the historical record—now apparently gliding unopposed toward a baptism by Oscar.

Like Slate on Facebook . Follow Slate and the Slate Foreign Desk on Twitter.

The King’s Speech: Good Movie, Bad History

With Colin Firth playing a royal with a stutter, The King's Speech is certain for Oscar magic, but Andrew Roberts says it gets the story all wrong and is simply bad history.

Andrew Roberts

Laurie Sparham / The Weinstein Company

The buzzy new movie, The King's Speech , is an affectionate portrait of Queen Elizabeth II's parents, Bertie, the Duke of York (later King George VI) and Elizabeth the Duchess of York (later the Queen Mother), told through the prism of the King's overcoming of his stammer. Starring Colin Firth as the king, Helena Bonham Carter as the queen, and Geoffrey Rush as the king's Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue, it also boasts a cast that includes Derek Jacobi, Michael Gambon, Timothy Spall, and Anthony Andrews. Yet before it is accepted as an accurate historical record of what happened to the Royal Family between 1925 and 1939, viewers should know of the very many glaring and egregious inaccuracies and tired old myths that this otherwise charming film unquestioningly regurgitates.

King's Speech Trailer

Of course Hollywood has long played fast and loose with history. As the clerihew goes:

Cecil B. de Mille Rather against his will Was persuaded to leave Moses Out of The Wars of the Roses.

But at a moment when, as a result of Prince William's engagement to Kate Middleton, many eyes will be turned onto the House of Windsor, it is as well to explode a few legends about the Prince's great-grandfather, George VI, the monarch who saw Britain through the Second World War. The first is the simple one that his stutter wasn't anything like as bad as the film depicts. In fact, it was relatively mild, and when he was concentrating hard on what he was saying it disappeared altogether. His speech to the Australian parliament in Canberra in 1927 was delivered without stuttering, for example. Yet in the movie it is so chronic that Colin Firth can hardly say a sentence without prolonged stuttering, right the way up to the outbreak of war in 1939. Of course, the whole premise of the movie is based on Logue's cure, but recordings of the Duke of York before he even met Logue make it clear that his problem was nothing like so acute as this film makes out.

Nor were the Duke and Duchess so pampered by courtiers that they could hardly work out how an elevator door worked, as is depicted in this movie. The Duke was mentioned in dispatches when as a midshipman he fought in a gun turret in the First World War battle of Jutland, mastering far more complex machinery than an elevator door; nor was the Duchess born royal. Similarly, Winston Churchill is shown as supporting the Abdication of George VI's elder brother King Edward VIII, whereas he violently opposed it. He is also depicted, along with the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang and the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, as turning up to Buckingham Palace to witness the King's broadcast on the day war broke out in September 1939, as though they didn't have better things to do. A glance at Churchill's own memoirs would have put that screenwriters' myth to rest. Then a huge crowd gathers outside Buckingham Palace to congratulate the king on his speech, which is also completely fictitious.

As history it is worthless because of its addiction to long-exploded myths… Kate Middleton had better get ready for a lifetime of this.

The Duke would never, ever have sneered at the Australians to an Australian who was almost also a stranger, on one occasion calling Logue "a jumped-up jackaroo from the outback." The Royal family of those days understandably eulogized the British Empire that had so recently bled itself so white for King and Country in the Great War, and Bertie had happy memories of his very successful 1927 visit there. Nor did Edward VIII taunt his brother for his stutter, accusing him of wanting to usurp his throne and calling him "B-b-b-b-Bertie." They were close friends, and Edward well knew that Bertie wanted to be king-emperor as little as he. It was also quite wrong to suggest that their grandfather, Edward VII, wanted their father, George V, to "be frightened" of him. The two men were very close, indeed Edward VII brought George V's desk next door to his at Buckingham Palace so they could work together. Similarly, Queen Mary is depicted as a cold and heartless mother, yet it was on her lap that George VI went to cry during the Abdication.

• Andrew Roberts: The King Who Couldn’t Speak Several minor social bêtises—Wallis Windsor not curtseying to the Yorks, the Queen saying "Very nice to meet you" rather than "How do you do?," a private secretary speaking of "The Duke" rather than "His Royal Highness," and others—imply that the film could have done with an historical consultant. Even the ludicrous old lies about Joachim von Ribbentrop sending Wallis Windsor 17 red roses every day, and her working as a geisha in Shanghai, are trotted out to blacken her character and make the Yorks look better.

Tom Hooper, the director, has spoken of his disappointment that the film is rated 'R' because of the 15 or so F-words (as well as "bugger", "arse","balls", "willy", and so on) that the King is supposed to have said. 'What I take away from that decision," says Hooper, "is that violence and torture is OK, but bad language isn't.' Yet the swearing is so egregiously prolonged and unnecessarily repeated—and I suspect not fully justified historically either—that Hooper only has himself to blame.

The King's Speech is gorgeously produced—the depiction of a London "pea-souper" fog is excellent—and is bound to win many awards for the excellent acting of an all-star cast. But as history it is worthless because of its addiction to long-exploded myths, and for insights into the personalities of the key figures in the House of Windsor of the Twenties and Thirties it is less than worthless. Kate Middleton had better get ready for a lifetime of this.

Plus: Check out more of the latest entertainment, fashion, and culture coverage on Sexy Beast—photos, videos, features, and Tweets .

Historian Andrew Roberts ' latest book, Masters and Commanders , was published in the UK in September. His previous books include Napoleon and Wellington , Hitler and Churchill , and A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900 . Roberts is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Royal Society of Arts.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here .

READ THIS LIST

Watch CBS News

The story behind "The King's Speech"

February 20, 2011 / 11:46 PM EST / CBS News

With 12 Oscar nominations, "The King's Speech" is among the most nominated films of all time. It's based on the true story of George VI, the father of the present queen of England. George VI was a man who, in the 1930s, desperately did not want to be king. He was afflicted nearly all his life by a crippling stammer which stood to rob Britain of a commanding voice at the very moment that Hitler rose to threaten Europe.

"The King's Speech" came, seemingly out of nowhere to become the film to beat on Oscar night. And Colin Firth is now the odds-on favorite to win best actor for his critically acclaimed portrayal of George VI.

The hidden letters behind "The King's Speech" What's it like to hold history in your hands? Scott Pelley had that chance, reporting on the Oscar-nominated film "The King's Speech." Hear from Colin Firth and Mark Logue, whose grandfather's friendship with a king made history.

Segment: "The King's Speech Extra: The real King George Extra: Colin Firth, King and Queen Extra: Firth's Oscar-nominated roles Extra: Firth's "bland" looks Pictures: Colin Firth on "60 Minutes"

When correspondent Scott Pelley asked Firth if he liked being king, Firth said, "I think it's hard to think of anything worse, really. I mean, I wouldn't change places with this man. And I would be very surprised if anybody watching the film would change places with this man."

"It's a perfect storm of catastrophic misfortunes for a man who does not want the limelight, who does not want to be heard publicly, who does not want to expose this humiliating impediment that he's spent his life battling," Firth explained. "He's actually fighting his own private war. He'd rather have been facing machine gun fire than have to face the microphone."

The microphone hung like a noose for the king, who was a stutterer from the age of 8. He was never meant to be king. But in 1936 his older brother gave up the throne to marry Wallace Simpson, a divorced American. Suddenly George VI and his wife Elizabeth reigned over an empire that was home to 25 percent of the world's population.

And like the George of over 1,000 years before, he had a dragon to slay: radio.

"When I looked at images of him or I listened to him, you do see that physical struggle," Firth said of the king's public speeches. "His eyes close, and you see him try to gather himself. And it's heartbreaking."

Among those listening was a 7-yr.-old British boy who, like the king, had a wealth of words but could not get them out.

"I was a profound stutterer. I started stuttering just before my third birthday. I didn't rid myself of it until I was 16. But my parents would encourage me to listen to the king's speeches during the war. And I thought, 'Wow if he can do that, there is hope for me.' So he became my childhood hero," David Seidler, who wrote the movie, told Pelley.

Seidler had grown up with the story, but he didn't want to tell the tale until he had permission from the late king's widow, known as The Queen Mother.

Seidler had sent a letter to her. "And finally, an answer came and it said, 'Dear Mr. Seidler, please, not during my lifetime the memory of these events is still too painful.' If the Queen Mum says wait to an Englishman, an Englishman waits. But, I didn't think I'd have to wait that long," he explained.

Asked why, Seidler said, "Well, she was a very elderly lady. Twenty five years later, just shy of her 102nd birthday, she finally left this realm."

After the Queen Mother's death in 2002, Seidler went to work. He found the theme of the story in the clash between his royal highness and an Australian commoner who became the king's salvation, an unknown speech therapist named Lionel Logue.

"The words that keep coming up when you hear about Lionel Logue are 'charisma' and 'confidence.' He would never say, 'I can fix your stuttering.' He would say, 'You can get a handle on your stuttering. I know you can succeed,'" Seidler said.

Geoffrey Rush plays Logue, an unorthodox therapist and a royal pain.

They say you can't make this stuff up, and in much of the film that's true. Seidler could not have imagined his work would lead to a discovery that would rewrite history. Researchers for the film tracked down Lionel Logue's grandson Mark, because the movie needed family photos to get the clothing right.

Mark Logue not only had pictures, he also had some diaries.

Produced by Ruth Streeter His grandfather's diaries were up in the attic in boxes that the family had nearly forgotten. When Logue hauled them down for the movie, he discovered more than 100 letters between the therapist and his king.

"'My dear Logue, thank you so much for sending me the books for my birthday, which are most acceptable.' That's so British isn't it. 'Yours very sincerely, Albert,'" Logue read from one of the letters.

"As you read through all these letters between your grandfather and the king, what did it tell you about the relationship between these two men?" Pelley asked.

"It's not the relationship between a doctor and his patient, it's a relationship between friends," Logue said.

We met Logue at the same address where his grandfather treated the king. And among the hundreds of pages of documents were Logue's first observations of George VI.

"Probably the most startling thing was the king's appointment card," Logue told Pelley. "It described in detail the king's stammer, which we hadn't seen anywhere else. And it also described in detail the intensity with the appointments."

The king saw Lionel Logue every day for an hour, including weekends.

"You know, he was so committed. I think he decided 'This is it. I have to overcome this stammer, and this is my chance,'" Mark Logue told Pelley.

In the film, the king throws himself into crazy therapies. But in truth, Logue didn't record his methods. The scenes are based on Seidler's experience and ideas of the actors.

"We threw in stuff that we knew. I mean, somebody had told me that the only way to release that muscle," actor Geoffrey Rush said of one of the speech exercises he did in the movie. "And of course, little did I realize that the particular lens they were using on that shot made me look like a Galapagos tortoise."

While the treatments spring from imagination, the actors read Logue's diaries and letters to bring realism to everything else.

"The line at the end, I found reading the diaries in bed one night, 'cause this is what I used to do every night, when Logue says 'You still stammered on the 'W'," Firth said.

The line was used in the movie.

"It shows that these men had a sense of humor. It showed that there was wit. It showed there was self mockery and it just showed a kind of buoyancy of spirit between them. The fact that he spoke on a desk standing upright in this little hidden room is something we found in the diaries as well," Firth told Pelley.

"In reality he had to stand up to speak, he had to have the window open," Firth said. "And he had to have his jacket off."

"And that wonderful, specific little eccentric observation that came from reality," Firth added.

One of the most remarkable things to come out of the Logue attic was a copy of what maybe the most important speech the king ever made - the speech that gave the movie its name. This was the moment when King George VI had to tell his people that for the second time in a generation they were at war with Germany. The stakes were enormous. The leader of the empire could not stumble over these words.

Mark Logue has the original copy of "the speech," typed out on Buckingham Palace stationary.

"What are all of these marks? All these vertical lines? What do they mean?" Pelley asked, looking over the documents.

"They're deliberate pauses so that the king would be able to sort of attack the next word without hesitation," Logue said. "He's replacing some words, he's crossing them out and suggesting another word that the King would find easier to pronounce."

"Here's a line that he's changed, 'We've tried to find a peaceful way out of the differences between my government.' He's changed that from, 'my government,' to, 'the differences between ourselves and those who would be our enemies,'" Pelley said.

"You know, I'm curious. Have either of you snuck into a theater and watched the film with a regular audience?" Pelley asked Firth and Rush.

"No, the only time I've ever snuck in to watch my own film I got quite nervous about it, because I just thought it be embarrassing to be seen doing that, so I pulled my collar up, and the hat down, over my eyes, and you know, snuck in as if I was going into a porn cinema, or something and went up the stairs, crept in, sidled in, to sit at the back, and I was the only person in the cinema. That's how well the film was doing," Firth remembered.

Now, it's a lot harder for Firth to go unnoticed. Recently he was immortalized with a star on Hollywood's Walk of Fame and brought along his Italian wife Livia.

They've been married 14 years and have two sons. With "The King's Speech," we realized Firth is one of the most familiar actors that we know almost nothing about. So we took him back to his home town Alresford in Hampshire, outside London. He's the son of college professors, but Firth dropped out of high school to go to acting school.

"But you don't have a Hampshire accent," Pelley pointed out.

"No. My accent has changed over the years, as a matter of survival. So until I was about 10, 'I used to talk like that,'" Firth replied, mimicking the local accent. "I remember it might have been on this street, actually, where I think the conversation went something like, 'Oy, you want to fight?' And I said, 'No, I don't.' 'Why not?' 'Well, 'cause you'll win.' 'No, I won't.' 'Well, will I win then?' 'Well, you might not.' And so, you know, we went trying to process the logic. And I thought, 'Have we dealt with it now?"

"Do we still have to fight?" Pelley asked.

"Do we actually have to do the practical now? We've done the theory," Firth replied.

He wanted us to see his first stage. It turned out to be the yard of his elementary school where he told stories from his own imagination.

"And at lunch times on the field up here, the crowd would gather and demand the story. They'd all sit 'round and say, 'No, we want the next bit,'" Firth remembered.

Firth told Pelley he found his calling for acting at the age of 14.

Asked what happened then, he told Pelley, "I used to go to drama classes up the road here on Saturday mornings. And one day I just had this epiphany. It was I can do this. I want to do this."

He has done 42 films in 26 years, most of them the polar opposite of "The King's Speech," like "Mamma Mia!"

"How hard was it to get you to do the scene for the closing credits?" Pelley asked, referring to Firth doing a musical number in an outrageous, Abba-inspired outfit.

"I think that's the reason I did the film," Firth joked.

"You have no shame?" Pelley asked.

"I'm sorry. That's if one thing has come out of '60 Minutes' here, it's we have discovered, we've unveiled the fact that Colin Firth has no shame. I am such a drag queen. It's one of my primary driving forces in life. If you cannot dangle a spandex suit and a little bit of mascara in front of me and not just have me go weak at the knees," Firth joked.

From queen to king, Firth is an actor of amazing range who now has his best shot at this first Oscar.

Like George VI himself, this movie wasn't meant to be king. "The King's Speech" was made for under $15 million. But now the movie, the director, the screenwriter David Seidler, who made it happen, and all the principal actors are in the running for Academy Awards. It would be Geoffrey Rush's second Oscar.

"What advice to you have for this man who may very likely win the Oscar this year?" Pelley asked Rush.

"Well enjoy it. It isn't the end of anything because you will go on and do a couple more flops probably, you might even sneak into another film in which no one is in the house," Rush joked.

But on Oscar night, stammering King George may have the last word. A lot of movies are based on true stories. But "The King's Speech" has reclaimed history.

More from CBS News

The King’s Speech Review

07 Jan 2011

118 minutes

King’s Speech , The

Some films turn out to be unexpectedly good. Not that you’ve written them off, only they ply their craft on the hush-hush. Before we even took our seats, Inception had trailed a blaze of its cleverness the size of a Parisian arrondissement. We were ready to be dazzled. If you had even heard of it, Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech looked no more than well-spoken Merchant Ivoriness optimistically promoted from Sunday teatime: decent cast, nice costumes, posh carpets. That was until the film finished a sneak-peak at a festival in deepest America, and the standing ovations began. Tweeters, bloggers and internet spokespeople of various levels of elocution announced it the Oscar favourite, and this also-ran arrives in our cinemas in a fanfare of trumpets.

But for all its pageantry, it isn’t a film of grandiose pretensions. Much better than that, it is an honest-to-goodness crowdpleaser. Rocky with dysfunctional royalty. Good Will Hunting set amongst the staid pageantry and fussy social mores of the late ’30s. The Odd Couple roaming Buckingham Palace. A film that will play and play. A prequel to The Queen.

Where lies its success? Let’s start with the script, by playwright David Seidler, a model for transforming history into an approachable blend of drama and wit. For a film about being horrendously tongue-tied, Seidler’s words are exquisitely measured, his insight as deep as it is softly spoken. Both an Aussie and a long-suffering stammerer, he first adapted the story as a play, written with the permission of both the late Queen Mother (George’s wife) and Logue’s widow. Stretching into the legroom of film, he loses none of the theatrical richness of allowing decent actors to joust and jostle and feed off each other.

As their two worlds clash, this outspoken “colonial” and this unspoken aristocrat, Seidler mines great humour from the situation. Logue’s outlandish treatments are designed to rock George, whom he insists on calling Bertie (the impertinence!), out of his discomfort zone. He has to lie on the floor, his dainty wife perched upon his chest, strengthening his diaphragm. He has to swing his arms like a chimpanzee, warble like a turkey. And in a sure-to-be classic scene, Logue cracks the dam of his patient’s cornered voice by getting him swearing. “Say the ‘F’ word,” commands Rush, his eyes twinkling at Logue’s front. “Fornication!” howls Firth, like a man bursting. Such naughtiness — escalating to a magnificent chorus of “shits” and “fucks” — landed the film an R rating in America. The silly-billies: the moment couldn’t be more tender or uplifting.

What Hooper sensed of Seidler’s play is that this is not about fixing a voice, but fixing a mind bullied by his father (a waxen-voiced Michael Gambon as George V) and brother since boyhood, a soul imprisoned by the burden of forthcoming kingliness. Between his handsome London backdrops, elevating any potential staginess with sleek forward motion and microscopic historical accuracy (from mist-occluded parks, to the Tardis-sprawl of the BBC’s broadcasting paraphernalia with the death-noose of their microphones), Hooper plays on the idea of childhood. We meet Logue’s scruffy brood and the twee Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret; while in another scene loaded with codified meaning, George begins to open up as he gently completes a model plane. The tragedy is that he never had a childhood. Friendship is a voyage into the unknown for Bertie. Logue is gluing him together.

Hooper, whose own mother recommended the play, knew straightaway here was his cornerstone — the unlikeliest of friendships. To get all zeitgeist on its royal behind, it’s a bromance. One that required two performers to go to opposite places. Colin Firth has found a rich vein of form: A Single Man provided emotional entrapment in repressed grief, but here were greater perils still, treading the perilous high-wire of physical affliction. In terror of mockery or Rainman, he looked to Derek Jacobi’s definitive stammering in I Claudius (Jacobi winkingly cast here as a conniving Archbishop Of Canterbury) and got to grips with an actor’s greatest fear — being unable to find his words. It’s a bristling irony: acting is a craft exemplified in the crystal-clear diction of Shakespeare, but here is a gripping performance where the actor is virtually incapable of speaking at all. Not in a straight line. It is an anti-acting role, yet Firth doesn’t ever stop communicating: pain, sadness, yearning; intelligence and humour demanding escape; and the fierce self-possession of a man born to privilege. When Logue, pushing and pushing, oversteps the mark, Bertie rounds on him, furious, his voice suddenly eloquent in the spate of his fury. The idea of class is never far away; what marks out one’s place in the social network of yesteryear more than how one speaks?

Logue, a psychotherapist before his time (a royal in therapy — the very thought!), finds Rush in equally fine fettle. He locates Logue’s own shortcomings, a failed actor who turns his office into a stage, striding and pontificating, a show-off with a big heart. A modernist trying to break through social prejudice. A colonial nobody desperate to be an English somebody. Stripped walls line Logue’s drafty chambers: the deprivations of pre-War Britain are here, yet warmed by family. The cushioned train of anterooms of Buckingham Palace appear antiseptic in comparison. Life crushed by velvet. Grimacing Whitehall serving as a cold reminder of war to come.

Any behind-the-drapes depictions of British royalty carry the base pleasures of a good snoop. But these were changing times. Helena Bonham Carter makes for a vibrant Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mum-to-be), both devoted wife and teasing wit whirling around the word “contraverseeal” like a figure skater, another modernist in a dusty enclave who takes the risk of contacting Logue. If anything, older brother Edward VIII was the true trailblazer, breaking through the bars of royal absolutes to marry American divorcee Mrs. Simpson, and unthinkably vacate the throne for his timorous brother. In that decision, precedents were shattered and the modern world spilled into the royal household. Guy Pearce (an Aussie in English robes) has enormous fun as the arrogant older sibling, plumbing his voice to the borders of camp, but a flash harry flinty enough to shed a nation for a wife. As George will angrily point out, what use does a king serve anymore?

If we start small, a lonely prince trying to express himself, we end big. History knocks the door down. Edward abdicates just as that unquenchable ranter Hitler gets warmed up, and Timothy Spall drops by as a slippery Churchill (a jar to the film’s subtleties) to sneer about oncoming “Nazzzeees”. A sense of terrible urgency engulfs the therapy, but what an ending it offers. George VI must use his faltering voice to soothe a frightened nation in a radio broadcast, all but conducted by Logue, transformed into match-winning glory. You’ll be lost for words.

Related Articles

Movies | 28 09 2023

Movies | 09 11 2020

Movies | 15 05 2017

Movies | 24 04 2016

Movies | 02 02 2016

Movies | 03 12 2014

Movies | 17 01 2012

Movies | 05 10 2011

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The King's Speech: True blood or right royal dud?

Director: Tom Hooper Entertainment grade: A– History grade: B+

Prince Albert, known as Bertie, was the second son of King George V. He acceded the British throne as King George VI on the abdication of his brother, King Edward VIII, known as David.

Bertie (Colin Firth) was from his childhood affected by a stammer, which made his public life exceptionally difficult. The film is right in suggesting he endured various therapies to address it, though the scene in which he is made to fill his mouth with marbles is straight out of My Fair Lady.

Or perhaps the film-makers were thinking of Charles I, another stammering king: he tried to correct his speech by filling his mouth with pebbles and talking to himself. The film has Bertie going to therapist Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush) in the late 1930s, a decade after the two really began working together. The importance of their relationship as depicted in the film is something of an overstatement.

David and Bertie's martinet father, George V (Michael Gambon), is shuffling off his mortal coil. Guy Pearce perfectly captures David's self-pitying brattishness and his coldness towards his family: when the real David was informed of his father's imminent death, he refused to return from a safari holiday in Africa and instead spent that evening seducing the wife of the local commissioner. Pearce does not perfectly capture David's accent. Owing to a childhood spent almost entirely with nannies, the Prince of Wales spoke in private with a Cockney inflection – and later, in exile, developed an American twang.

It must be difficult to play Winston Churchill without slipping into caricature. Timothy Spall certainly can't manage it, pouting, scowling and waddling around like the Penguin. Just as bad is the film's implication that Churchill counselled Bertie to take over during the abdication crisis. In fact, Churchill was one of David's fiercest supporters, advising him: "Retire to Windsor Castle! Summon the Beefeaters! Raise the drawbridge! Close the gates! And dare Baldwin to drag you out!" Churchill also rewrote David's abdication speech, splendidly delivered by Pearce in the movie. Before Churchill got his hands on it, David allegedly wanted to open with: "I now wish to tell you how I was jockeyed off the throne." Churchill replaced this with the more dignified: "At long last I am able to say a few words of my own."