- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Reference List: Common Reference List Examples

Article (with doi).

Alvarez, E., & Tippins, S. (2019). Socialization agents that Puerto Rican college students use to make financial decisions. Journal of Social Change , 11 (1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.5590/JOSC.2019.11.1.07

Laplante, J. P., & Nolin, C. (2014). Consultas and socially responsible investing in Guatemala: A case study examining Maya perspectives on the Indigenous right to free, prior, and informed consent. Society & Natural Resources , 27 , 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2013.861554

Use the DOI number for the source whenever one is available. DOI stands for "digital object identifier," a number specific to the article that can help others locate the source. In APA 7, format the DOI as a web address. Active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list. Also see our Quick Answer FAQ, "Can I use the DOI format provided by library databases?"

Jerrentrup, A., Mueller, T., Glowalla, U., Herder, M., Henrichs, N., Neubauer, A., & Schaefer, J. R. (2018). Teaching medicine with the help of “Dr. House.” PLoS ONE , 13 (3), Article e0193972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193972

For journal articles that are assigned article numbers rather than page ranges, include the article number in place of the page range.

For more on citing electronic resources, see Electronic Sources References .

Article (Without DOI)

Found in a common academic research database or in print.

Casler , T. (2020). Improving the graduate nursing experience through support on a social media platform. MEDSURG Nursing , 29 (2), 83–87.

If an article does not have a DOI and you retrieved it from a common academic research database through the university library, there is no need to include any additional electronic retrieval information. The reference list entry looks like the entry for a print copy of the article. (This format differs from APA 6 guidelines that recommended including the URL of a journal's homepage when the DOI was not available.) Note that APA 7 has additional guidance on reference list entries for articles found only in specific databases or archives such as Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, UpToDate, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and university archives. See APA 7, Section 9.30 for more information.

Found on an Open Access Website

Eaton, T. V., & Akers, M. D. (2007). Whistleblowing and good governance. CPA Journal , 77 (6), 66–71. http://archives.cpajournal.com/2007/607/essentials/p58.htm

Provide the direct web address/URL to a journal article found on the open web, often on an open access journal's website. In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Weinstein, J. A. (2010). Social change (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

If the book has an edition number, include it in parentheses after the title of the book. If the book does not list any edition information, do not include an edition number. The edition number is not italicized.

American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.).

If the author and publisher are the same, only include the author in its regular place and omit the publisher.

Lencioni, P. (2012). The advantage: Why organizational health trumps everything else in business . Jossey-Bass. https://amzn.to/343XPSJ

As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, it is no longer necessary to include the ebook format in the title. However, if you listened to an audiobook and the content differs from the text version (e.g., abridged content) or your discussion highlights elements of the audiobook (e.g., narrator's performance), then note that it is an audiobook in the title element in brackets. For ebooks and online audiobooks, also include the DOI number (if available) or nondatabase URL but leave out the electronic retrieval element if the ebook was found in a common academic research database, as with journal articles. APA 7 allows for the shortening of long DOIs and URLs, as shown in this example. See APA 7, Section 9.36 for more information.

Chapter in an Edited Book

Poe, M. (2017). Reframing race in teaching writing across the curriculum. In F. Condon & V. A. Young (Eds.), Performing antiracist pedagogy in rhetoric, writing, and communication (pp. 87–105). University Press of Colorado.

Include the page numbers of the chapter in parentheses after the book title.

Christensen, L. (2001). For my people: Celebrating community through poetry. In B. Bigelow, B. Harvey, S. Karp, & L. Miller (Eds.), Rethinking our classrooms: Teaching for equity and justice (Vol. 2, pp. 16–17). Rethinking Schools.

Also include the volume number or edition number in the parenthetical information after the book title when relevant.

Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, pp. 3-66). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923)

When a text has been republished as part of an anthology collection, after the author’s name include the date of the version that was read. At the end of the entry, place the date of the original publication inside parenthesis along with the note “original work published.” For in-text citations of republished work, use both dates in the parenthetical citation, original date first with a slash separating the years, as in this example: Freud (1923/1961). For more information on reprinted or republished works, see APA 7, Sections 9.40-9.41.

Classroom Resources

Citing classroom resources.

If you need to cite content found in your online classroom, use the author (if there is one listed), the year of publication (if available), the title of the document, and the main URL of Walden classrooms. For example, you are citing study notes titled "Health Effects of Exposure to Forest Fires," but you do not know the author's name, your reference entry will look like this:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

If you do know the author of the document, your reference will look like this:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

A few notes on citing course materials:

- [Lecture notes]

- [Course handout]

- [Study notes]

- It can be difficult to determine authorship of classroom documents. If an author is listed on the document, use that. If the resource is clearly a product of Walden (such as the course-based videos), use Walden University as the author. If you are unsure or if no author is indicated, place the title in the author spot, as above.

- If you cannot determine a date of publication, you can use n.d. (for "no date") in place of the year.

Note: The web location for Walden course materials is not directly retrievable without a password, and therefore, following APA guidelines, use the main URL for the class sites: https://class.waldenu.edu.

Citing Tempo Classroom Resources

Clear author:

Smith, A. (2005). Health effects of exposure to forest fires [PowerPoint slides]. Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Unclear author:

Health effects of exposure to forest fires [Lecture notes]. (2005). Walden University Brightspace. https://mytempo.waldenu.edu

Conference Sessions and Presentations

Feinman, Y. (2018, July 27). Alternative to proctoring in introductory statistics community college courses [Poster presentation]. Walden University Research Symposium, Minneapolis, MN, United States. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/symposium2018/23/

Torgerson, K., Parrill, J., & Haas, A. (2019, April 5-9). Tutoring strategies for online students [Conference session]. The Higher Learning Commission Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, United States. http://onlinewritingcenters.org/scholarship/torgerson-parrill-haas-2019/

Dictionary Entry

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Leadership. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary . Retrieved May 28, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/leadership

When constructing a reference for an entry in a dictionary or other reference work that has no byline (i.e., no named individual authors), use the name of the group—the institution, company, or organization—as author (e.g., Merriam Webster, American Psychological Association, etc.). The name of the entry goes in the title position, followed by "In" and the italicized name of the reference work (e.g., Merriam-Webster.com dictionary , APA dictionary of psychology ). In this instance, APA 7 recommends including a retrieval date as well for this online source since the contents of the page change over time. End the reference entry with the specific URL for the defined word.

Discussion Board Post

Osborne, C. S. (2010, June 29). Re: Environmental responsibility [Discussion post]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Dissertations or Theses

Retrieved From a Database

Nalumango, K. (2019). Perceptions about the asylum-seeking process in the United States after 9/11 (Publication No. 13879844) [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Retrieved From an Institutional or Personal Website

Evener. J. (2018). Organizational learning in libraries at for-profit colleges and universities [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6606&context=dissertations

Unpublished Dissertation or Thesis

Kirwan, J. G. (2005). An experimental study of the effects of small-group, face-to-face facilitated dialogues on the development of self-actualization levels: A movement towards fully functional persons [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center.

For further examples and information, see APA 7, Section 10.6.

Legal Material

For legal references, APA follows the recommendations of The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation , so if you have any questions beyond the examples provided in APA, seek out that resource as well.

Court Decisions

Reference format:

Name v. Name, Volume Reporter Page (Court Date). URL

Sample reference entry:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

Sample citation:

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in schools unconstitutional.

Note: Italicize the case name when it appears in the text of your paper.

Name of Act, Title Source § Section Number (Year). URL

Sample reference entry for a federal statute:

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004). https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ446/PLAW-108publ446.pdf

Sample reference entry for a state statute:

Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, Minn. Stat. §§ 148.171 et seq. (2019). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/148.171

Sample citation: Minnesota nurses must maintain current registration in order to practice (Minnesota Nurse Practice Act, 2010).

Note: The § symbol stands for "section." Use §§ for sections (plural). To find this symbol in Microsoft Word, go to "Insert" and click on Symbol." Look in the Latin 1-Supplement subset. Note: U.S.C. stands for "United States Code." Note: The Latin abbreviation " et seq. " means "and what follows" and is used when the act includes the cited section and ones that follow. Note: List the chapter first followed by the section or range of sections.

Unenacted Bills and Resolutions

(Those that did not pass and become law)

Title [if there is one], bill or resolution number, xxx Cong. (year). URL

Sample reference entry for Senate bill:

Anti-Phishing Act, S. 472, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/senate-bill/472

Sample reference entry for House of Representatives resolution:

Anti-Phishing Act, H.R. 1099, 109th Cong. (2005). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-congress/house-bill/1099

The Anti-Phishing Act (2005) proposed up to 5 years prison time for people running Internet scams.

These are the three legal areas you may be most apt to cite in your scholarly work. For more examples and explanation, see APA 7, Chapter 11.

Magazine Article

Clay, R. (2008, June). Science vs. ideology: Psychologists fight back about the misuse of research. Monitor on Psychology , 39 (6). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2008/06/ideology

Note that for citations, include only the year: Clay (2008). For magazine articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For magazine articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print magazine, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

Newspaper Article (Retrieved Online)

Baker, A. (2014, May 7). Connecticut students show gains in national tests. New York Times . http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/08/nyregion/national-assessment-of-educational-progress-results-in-Connecticut-and-New-Jersey.html

Include the full date in the format Year, Month Day. Do not include a retrieval date for periodical sources found on websites. Note that for citations, include only the year: Baker (2014). For newspaper articles retrieved from a common academic research database, leave out the URL. For newspaper articles from an online news website that is not an online version of a print newspaper, follow the format for a webpage reference list entry.

OASIS Resources

Oasis webpage.

OASIS. (n.d.). Common reference list examples . Walden University. https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/apa/references/examples

For all OASIS content, list OASIS as the author. Because OASIS webpages do not include publication dates, use “n.d.” for the year.

Interactive Guide

OASIS. (n.d.). Embrace iterative research and writing [Interactive guide]. Walden University. https://academics.waldenu.edu/oasis/iterative-research-writing-web

For OASIS multimedia resources, such as interactive guides, include a description of the resource in brackets after the title.

Online Video/Webcast

Walden University. (2013). An overview of learning [Video]. Walden University Canvas. https://waldenu.instructure.com

Use this format for online videos such as Walden videos in classrooms. Most of our classroom videos are produced by Walden University, which will be listed as the author in your reference and citation. Note: Some examples of audiovisual materials in the APA manual show the word “Producer” in parentheses after the producer/author area. In consultation with the editors of the APA manual, we have determined that parenthetical is not necessary for the videos in our courses. The manual itself is unclear on the matter, however, so either approach should be accepted. Note that the speaker in the video does not appear in the reference list entry, but you may want to mention that person in your text. For instance, if you are viewing a video where Tobias Ball is the speaker, you might write the following: Tobias Ball stated that APA guidelines ensure a consistent presentation of information in student papers (Walden University, 2013). For more information on citing the speaker in a video, see our page on Common Citation Errors .

Taylor, R. [taylorphd07]. (2014, February 27). Scales of measurement [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDsMUlexaMY

Walden University Academic Skills Center. (2020, April 15). One-way ANCOVA: Introduction [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_XnNDQ5CNW8

For videos from streaming sites, use the person or organization who uploaded the video in the author space to ensure retrievability, whether or not that person is the speaker in the video. A username can be provided in square brackets. As a change from APA 6 to APA 7, include the publisher after the title, and do not use "Retrieved from" before the URL. See APA 7, Section 10.12 for more information and examples.

See also reference list entry formats for TED Talks .

Technical and Research Reports

Edwards, C. (2015). Lighting levels for isolated intersections: Leading to safety improvements (Report No. MnDOT 2015-05). Center for Transportation Studies. http://www.cts.umn.edu/Publications/ResearchReports/reportdetail.html?id=2402

Technical and research reports by governmental agencies and other research institutions usually follow a different publication process than scholarly, peer-reviewed journals. However, they present original research and are often useful for research papers. Sometimes, researchers refer to these types of reports as gray literature , and white papers are a type of this literature. See APA 7, Section 10.4 for more information.

Reference list entires for TED Talks follow the usual guidelines for multimedia content found online. There are two common places to find TED talks online, with slightly different reference list entry formats for each.

TED Talk on the TED website

If you find the TED Talk on the TED website, follow the format for an online video on an organizational website:

Owusu-Kesse, K. (2020, June). 5 needs that any COVID-19 response should meet [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/kwame_owusu_kesse_5_needs_that_any_covid_19_response_should_meet

The speaker is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on the TED website. For citations, use the speaker's surname.

TED Talk on YouTube

If you find the TED Talk on YouTube or another streaming video website, follow the usual format for streaming video sites:

TED. (2021, February 5). The shadow pandemic of domestic violence during COVID-19 | Kemi DaSilvalbru [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGdID_ICFII

TED is the author in the reference list entry if the video is posted on YouTube since it is the channel on which the video is posted. For citations, use TED as the author.

Walden University Course Catalog

To include the Walden course catalog in your reference list, use this format:

Walden University. (2020). 2019-2020 Walden University catalog . https://catalog.waldenu.edu/index.php

If you cite from a specific portion of the catalog in your paper, indicate the appropriate section and paragraph number in your text:

...which reflects the commitment to social change expressed in Walden University's mission statement (Walden University, 2020, Vision, Mission, and Goals section, para. 2).

And in the reference list:

Walden University. (2020). Vision, mission, and goals. In 2019-2020 Walden University catalog. https://catalog.waldenu.edu/content.php?catoid=172&navoid=59420&hl=vision&returnto=search

Vartan, S. (2018, January 30). Why vacations matter for your health . CNN. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/why-vacations-matter/index.html

For webpages on the open web, include the author, date, webpage title, organization/site name, and URL. (There is a slight variation for online versions of print newspapers or magazines. For those sources, follow the models in the previous sections of this page.)

American Federation of Teachers. (n.d.). Community schools . http://www.aft.org/issues/schoolreform/commschools/index.cfm

If there is no specified author, then use the organization’s name as the author. In such a case, there is no need to repeat the organization's name after the title.

In APA 7, active hyperlinks for DOIs and URLs should be used for documents meant for screen reading. Present these hyperlinks in blue and underlined text (the default formatting in Microsoft Word), although plain black text is also acceptable. Be consistent in your formatting choice for DOIs and URLs throughout your reference list.

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Common Reference List Examples

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Reference List: Overview

- Next Page: Common Military Reference List Examples

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Referencing

A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 15 September 2023.

Referencing is an important part of academic writing. It tells your readers what sources you’ve used and how to find them.

Harvard is the most common referencing style used in UK universities. In Harvard style, the author and year are cited in-text, and full details of the source are given in a reference list .

Harvard Reference Generator

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Harvard in-text citation, creating a harvard reference list, harvard referencing examples, referencing sources with no author or date, frequently asked questions about harvard referencing.

A Harvard in-text citation appears in brackets beside any quotation or paraphrase of a source. It gives the last name of the author(s) and the year of publication, as well as a page number or range locating the passage referenced, if applicable:

Note that ‘p.’ is used for a single page, ‘pp.’ for multiple pages (e.g. ‘pp. 1–5’).

An in-text citation usually appears immediately after the quotation or paraphrase in question. It may also appear at the end of the relevant sentence, as long as it’s clear what it refers to.

When your sentence already mentions the name of the author, it should not be repeated in the citation:

Sources with multiple authors

When you cite a source with up to three authors, cite all authors’ names. For four or more authors, list only the first name, followed by ‘ et al. ’:

Sources with no page numbers

Some sources, such as websites , often don’t have page numbers. If the source is a short text, you can simply leave out the page number. With longer sources, you can use an alternate locator such as a subheading or paragraph number if you need to specify where to find the quote:

Multiple citations at the same point

When you need multiple citations to appear at the same point in your text – for example, when you refer to several sources with one phrase – you can present them in the same set of brackets, separated by semicolons. List them in order of publication date:

Multiple sources with the same author and date

If you cite multiple sources by the same author which were published in the same year, it’s important to distinguish between them in your citations. To do this, insert an ‘a’ after the year in the first one you reference, a ‘b’ in the second, and so on:

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

A bibliography or reference list appears at the end of your text. It lists all your sources in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, giving complete information so that the reader can look them up if necessary.

The reference entry starts with the author’s last name followed by initial(s). Only the first word of the title is capitalised (as well as any proper nouns).

Sources with multiple authors in the reference list

As with in-text citations, up to three authors should be listed; when there are four or more, list only the first author followed by ‘ et al. ’:

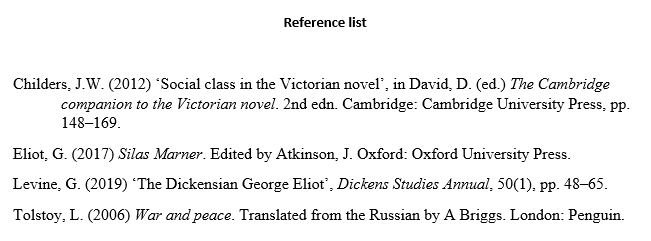

Reference list entries vary according to source type, since different information is relevant for different sources. Formats and examples for the most commonly used source types are given below.

- Entire book

- Book chapter

- Translated book

- Edition of a book

Journal articles

- Print journal

- Online-only journal with DOI

- Online-only journal with no DOI

- General web page

- Online article or blog

- Social media post

Sometimes you won’t have all the information you need for a reference. This section covers what to do when a source lacks a publication date or named author.

No publication date

When a source doesn’t have a clear publication date – for example, a constantly updated reference source like Wikipedia or an obscure historical document which can’t be accurately dated – you can replace it with the words ‘no date’:

Note that when you do this with an online source, you should still include an access date, as in the example.

When a source lacks a clearly identified author, there’s often an appropriate corporate source – the organisation responsible for the source – whom you can credit as author instead, as in the Google and Wikipedia examples above.

When that’s not the case, you can just replace it with the title of the source in both the in-text citation and the reference list:

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, September 15). A Quick Guide to Harvard Referencing | Citation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/referencing/harvard-style/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, harvard style bibliography | format & examples, referencing books in harvard style | templates & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

University of Pittsburgh Library System

- Collections

Course & Subject Guides

Citation styles: apa, mla, chicago, turabian, ieee.

- APA 7th Edition

- Turabian 9th

- Writing & Citing Help

- Understanding Plagiarism

Quick Links

Listed below are a few quick links to resources that will aid you in citing sources.

- Sign up for a Mendeley, EndNote, or Zotero training class.

- APA 7th Edition Published in October 2019. Visit this page for links to resources and examples.

- MLA Need help with citing MLA style? Find information here along with links to books in PittCat and free online resources.

- Chicago/Turabian Need help with citing Chicago/Turabian style? Find examples here along with links to the online style manual and free online resources.

Getting Started: How to use this guide

This LibGuide was designed to provide you with assistance in citing your sources when writing an academic paper.

There are different styles which format the information differently. In each tab, you will find descriptions of each citation style featured in this guide along with links to online resources for citing and a few examples.

What is a citation and citation style?

A citation is a way of giving credit to individuals for their creative and intellectual works that you utilized to support your research. It can also be used to locate particular sources and combat plagiarism. Typically, a citation can include the author's name, date, location of the publishing company, journal title, or DOI (Digital Object Identifier).

A citation style dictates the information necessary for a citation and how the information is ordered, as well as punctuation and other formatting.

How to do I choose a citation style?

There are many different ways of citing resources from your research. The citation style sometimes depends on the academic discipline involved. For example:

- APA (American Psychological Association) is used by Education, Psychology, and Sciences

- MLA (Modern Language Association) style is used by the Humanities

- Chicago/Turabian style is generally used by Business, History, and the Fine Arts

*You will need to consult with your professor to determine what is required in your specific course.

Click the links below to find descriptions of each style along with a sample of major in-text and bibliographic citations, links to books in PittCat, online citation manuals, and other free online resources.

- APA Citation Style

- MLA Citation Style

- Chicago/Turabian Citation Style

- Tools for creating bibliographies (CItation Managers)

Writing Centers

Need someone to review your paper? Visit the Writing Center or Academic Success Center on your campus.

- Oakland Campus

- Greensburg Campus

- Johnstown Campus

- Titusville Campus

- Bradford Campus

- Next: APA 7th Edition >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://pitt.libguides.com/citationhelp

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Science Fair Resources

Citing your sources.

- The Scientific Method

- Books in Our Collection

- Online Encyclopedias

- General Science Journals

- Other Helpful Resources

- Find Articles

- Poster Techniques

- Community Borrower Privileges This link opens in a new window

- Fayetteville Public Library

When you use ideas that are not your own, it is important to credit or cite the author(s) or source, even if you do not quote their idea or words exactly as written. Citing your sources allows your reader to identify the works you have consulted and to understand the scope of your research. There are many different citation styles available. You may be required to use a particular style or you may choose one.

One of the commonly used styles is the APA (American Psychological Association) Style.

APA style stipulates that authors use brief references in the text of a work with full bibliographic details supplied in a Reference List (typically at the end of your document). In text, the reference is very brief and usually consists simply of the author's last name and a date.For example:

...Sheep milk has been proved to contain more nutrients than cow milk (Johnson, 2005).

In a Reference list, the reference contains full bibliographic details written in a format that depends on the type of reference. Examples of formats for some common types of references are listed below. For additional information, visit the University of Arkansas libraries webpage on citing your sources . Another useful web-site on this topic is here.

Author last name, Author First Initial. Author Second Initial. (Publication Year). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume(issue) (if issue numbered), pages.

Bass, M. A., Enochs, W. K., & DiBrezzo, R. (2002). Comparison of two exercise programs on general well-being of college students. Psychological Reports, 91(3), 1195-1201.

Author Last Name, Author First Initial. Author Second Initial. (if there is no author move entry title to first position) (Publication year). Title of article or entry. In Work title. (Vol. number, pp. pages). Place: Publisher.

"Ivory-billed woodpecker." (2002). In The new encyclopædia britannica. (Vol. 5, p. ). 15th ed. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

Author Last Name, Author First Initial. Author Second Initial. (if there is no author move entry title to first position) (Publication year). Title of article or entry. In Work title. Retrieved from (database name or URL).

Ivory-billed woodpecker. (2006). In Encyclopædia britannica online. Retrieved from http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9043081

Author last name, Author First Initial. Author Second Initial. (Publication Year, Month Day). Title of article. Title of Magazine,volume, pages.

Holloway, M. (2005, August). When extinct isn't. Scientific American, 293, 22-23.

Author last name, Author First Initial. Author Second Initial. (Publication Year, Month Day). Title of article. Title of Magazine. volume, pages. Retrieved from (database name or URL).

Holloway, M. (2005, August). When extinct isn't. Scientific American, 293, 22-23. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier database.

Page Author Last Name, Page Author First Initial. Page Author Second Initial. Page title [nature of work - web site, blog, forum posting, etc.]. (Publication Year). Retrieved from (URL)

Sabo, G., et al. Rock art in Arkansas [Web site]. (2001). Retrieved from http://arkarcheology.uark.edu/rockart/index.html

- << Previous: Find Articles

- Next: Poster Techniques >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 12:12 PM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/sciencefair

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

- Privacy Policy

Home » How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Citation

Research paper citation refers to the act of acknowledging and referencing a previously published work in a scholarly or academic paper . When citing sources, researchers provide information that allows readers to locate the original source, validate the claims or arguments made in the paper, and give credit to the original author(s) for their work.

The citation may include the author’s name, title of the publication, year of publication, publisher, and other relevant details that allow readers to trace the source of the information. Proper citation is a crucial component of academic writing, as it helps to ensure accuracy, credibility, and transparency in research.

How to Cite Research Paper

There are several formats that are used to cite a research paper. Follow the guide for the Citation of a Research Paper:

Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The History of the World. Penguin Press, 2010.

Journal Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, vol. Volume Number, no. Issue Number, Year of Publication, pp. Page Numbers.

Example : Johnson, Emma. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Environmental Science Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019, pp. 45-59.

Research Paper

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Name, Location, Date of Conference.

Example : Garcia, Maria. “The Importance of Early Childhood Education.” International Conference on Education, Paris, 5-7 June 2018.

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Title, Publisher, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Smith, John. “The Benefits of Exercise.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 1 March 2022, https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise.

News Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Robinson, Sarah. “Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies.” The New York Times, 22 Jan. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2010). The History of the World. Penguin Press.

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Johnson, E., Smith, K., & Lee, M. (2019). The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture. Environmental Science Journal, 10(2), 45-59.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor First Initial. Last Name (Ed.), Title of Conference Proceedings (page numbers). Publisher.

Example: Garcia, M. (2018). The Importance of Early Childhood Education. In J. Smith (Ed.), Proceedings from the International Conference on Education (pp. 60-75). Springer.

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of webpage. Website name. URL

Example: Smith, J. (2022, March 1). The Benefits of Exercise. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Newspaper name. URL.

Example: Robinson, S. (2021, January 22). Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html

Chicago/Turabian style

Please note that there are two main variations of the Chicago style: the author-date system and the notes and bibliography system. I will provide examples for both systems below.

Author-Date system:

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year, Page Number)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2005, 28)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2005. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press.

Notes and Bibliography system:

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, Title of Book (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Number.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, The History of America (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), 28.

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

JOURNAL ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number (Issue Number): Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2010, 45)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2010. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60(2): 39-56.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Article Title,” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “The Impact of Social Media on Society,” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

RESEARCH PAPERS:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Publisher, Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Jones 2015, 12)

- Reference list: Jones, David. 2015. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. Springer, 10-20.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Paper,” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: David Jones, “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015 (New York: Springer, 10-20).

- Bibliography citation: Jones, David. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. New York: Springer, 10-20.

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2018)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2018. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Webpage,” Website Name, URL (accessed Date).

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL (accessed Date).

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, “The Importance of Recycling,” Environmental News Network, https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

NEWS ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Month Day.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2022)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2022. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times, January 15.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Article,” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity,” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

Harvard referencing style

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2008). The Art of War. Random House.

Journal article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Brown, M. (2012). The impact of social media on business communication. Harvard Business Review, 90(12), 85-92.

Research paper:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor’s First initial. Last name (Ed.), Title of book (page range). Publisher.

Example: Johnson, R. (2015). The effects of climate change on agriculture. In S. Lee (Ed.), Climate Change and Sustainable Development (pp. 45-62). Springer.

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example: Smith, J. (2017, May 23). The history of the internet. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-the-internet

News article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of newspaper, page number (if applicable).

Example: Thompson, E. (2022, January 5). New study finds coffee may lower risk of dementia. The New York Times, A1.

IEEE Format

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Book. Publisher.

Smith, J. K. (2015). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House.

Journal Article:

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Title of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), page numbers.

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2016). Interactivity and the Future of Journalism. Journalism Studies, 17(2), 228-246.

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Paper. Paper presented at Conference Name, Location.

Jones, L. K., & Brown, M. A. (2018). The Role of Social Media in Political Campaigns. Paper presented at the 2018 International Conference on Social Media and Society, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Website: Author(s) or Organization Name. (Year of Publication or Last Update). Title of Webpage. Website Name. URL.

Example: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (2019, August 29). NASA’s Mission to Mars. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/topics/journeytomars/index.html

- News Article: Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Name of News Source. URL.

Example: Johnson, M. (2022, February 16). Climate Change: Is it Too Late to Save the Planet? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/16/world/climate-change-planet-scn/index.html

Vancouver Style

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “The study conducted by Smith and Johnson^1 found that…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of book. Edition if any. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J, Johnson L. Introduction to Molecular Biology. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Several studies have reported that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Abbreviated name of journal. Year of publication; Volume number (Issue number): Page range.

Example: Jones S, Patel K, Smith J. The effects of exercise on cardiovascular health. J Cardiol. 2018; 25(2): 78-84.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Previous research has shown that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of paper. In: Editor(s). Title of the conference proceedings. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. Page range.

Example: Johnson L, Smith J. The role of stem cells in tissue regeneration. In: Patel S, ed. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Regenerative Medicine. London: Academic Press; 2016. p. 68-73.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the World Health Organization^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of webpage. Name of website. URL [Accessed Date].

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public [Accessed 3 March 2023].

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the New York Times^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Name of newspaper. Year Month Day; Section (if any): Page number.

Example: Jones S. Study shows that sleep is essential for good health. The New York Times. 2022 Jan 12; Health: A8.

Author(s). Title of Book. Edition Number (if it is not the first edition). Publisher: Place of publication, Year of publication.

Example: Smith, J. Chemistry of Natural Products. 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2015.

Journal articles:

Author(s). Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Garcia, A. M.; Jones, B. A.; Smith, J. R. Selective Synthesis of Alkenes from Alkynes via Catalytic Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10754-10759.

Research papers:

Author(s). Title of Paper. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Brown, H. D.; Jackson, C. D.; Patel, S. D. A New Approach to Photovoltaic Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2018, 26, 134-142.

Author(s) (if available). Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: National Institutes of Health. Heart Disease and Stroke. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/heart-disease-and-stroke (accessed April 7, 2023).

News articles:

Author(s). Title of Article. Name of News Publication. Date of Publication. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: Friedman, T. L. The World is Flat. New York Times. April 7, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/07/opinion/world-flat-globalization.html (accessed April 7, 2023).

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a book should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of book (in italics)

- Edition (if applicable)

- Place of publication

- Year of publication

Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, et al. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman; 2000.

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a journal article should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of article

- Abbreviated title of journal (in italics)

- Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Chen H, Huang Y, Li Y, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207081. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7081

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a research paper should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of paper

- Name of journal or conference proceeding (in italics)

- Volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ. Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet. 2011;27(2):41-47. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a website should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of web page or article

- Name of website (in italics)

- Date of publication or last update (if available)

- URL (website address)

- Date of access (month day, year)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to protect yourself and others. CDC. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a news article should include the following information, in this order:

- Name of newspaper or news website (in italics)

- Date of publication

Gorman J. Scientists use stem cells from frogs to build first living robots. The New York Times. January 13, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/science/living-robots-xenobots.html

Bluebook Format

One author: Daniel J. Solove, The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet (Yale University Press 2007).

Two or more authors: Martha Nussbaum and Saul Levmore, eds., The Offensive Internet: Speech, Privacy, and Reputation (Harvard University Press 2010).

Journal article

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 154, no. 3 (January 2006): 477-560.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Journal of Dispute Resolution 2003, no. 1 (2003): 7-19.

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 113, 2005.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Cyberlaw Research Paper Series Paper No. 00-5, 2000.

WebsiteElectronic Frontier Foundation, “Surveillance Self-Defense,” accessed April 8, 2023, https://ssd.eff.org/.

News article

One author: Mark Sherman, “Court Deals Major Blow to Net Neutrality Rules,” ABC News, January 14, 2014, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/court-deals-major-blow-net-neutrality-rules-21586820.

Two or more authors: Siobhan Hughes and Brent Kendall, “AT&T Wins Approval to Buy Time Warner,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/at-t-wins-approval-to-buy-time-warner-1528847249.

In-Text Citation: (Author’s last name Year of Publication: Page Number)

Example: (Smith 2010: 35)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Book. Edition. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J. Biology: A Textbook. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Example: (Johnson 2014: 27)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Abbreviated Title of Journal. Year of publication;Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example: Johnson S. The role of dopamine in addiction. J Neurosci. 2014;34(8): 2262-2272.

Example: (Brown 2018: 10)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Paper. Paper presented at: Name of Conference; Date of Conference; Place of Conference.

Example: Brown R. The impact of social media on mental health. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2018; San Francisco, CA.

Example: (World Health Organization 2020: para. 2)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL. Published date. Accessed date.

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. WHO website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 17, 2020. Accessed September 5, 2021.

Example: (Smith 2019: para. 5)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper or Magazine. Year of publication; Month Day:Page Numbers.

Example: Smith K. New study finds link between exercise and mental health. The New York Times. 2019;May 20: A6.

Purpose of Research Paper Citation

The purpose of citing sources in a research paper is to give credit to the original authors and acknowledge their contribution to your work. By citing sources, you are also demonstrating the validity and reliability of your research by showing that you have consulted credible and authoritative sources. Citations help readers to locate the original sources that you have referenced and to verify the accuracy and credibility of your research. Additionally, citing sources is important for avoiding plagiarism, which is the act of presenting someone else’s work as your own. Proper citation also shows that you have conducted a thorough literature review and have used the existing research to inform your own work. Overall, citing sources is an essential aspect of academic writing and is necessary for building credibility, demonstrating research skills, and avoiding plagiarism.

Advantages of Research Paper Citation

There are several advantages of research paper citation, including:

- Giving credit: By citing the works of other researchers in your field, you are acknowledging their contribution and giving credit where it is due.

- Strengthening your argument: Citing relevant and reliable sources in your research paper can strengthen your argument and increase its credibility. It shows that you have done your due diligence and considered various perspectives before drawing your conclusions.

- Demonstrating familiarity with the literature : By citing various sources, you are demonstrating your familiarity with the existing literature in your field. This is important as it shows that you are well-informed about the topic and have done a thorough review of the available research.

- Providing a roadmap for further research: By citing relevant sources, you are providing a roadmap for further research on the topic. This can be helpful for future researchers who are interested in exploring the same or related issues.

- Building your own reputation: By citing the works of established researchers in your field, you can build your own reputation as a knowledgeable and informed scholar. This can be particularly helpful if you are early in your career and looking to establish yourself as an expert in your field.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Trends in mathematics education and insights from a meta-review and bibliometric analysis of review studies

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mustafa Cevikbas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7844-4707 1 ,

- Gabriele Kaiser 2 , 3 &

- Stanislaw Schukajlow 4

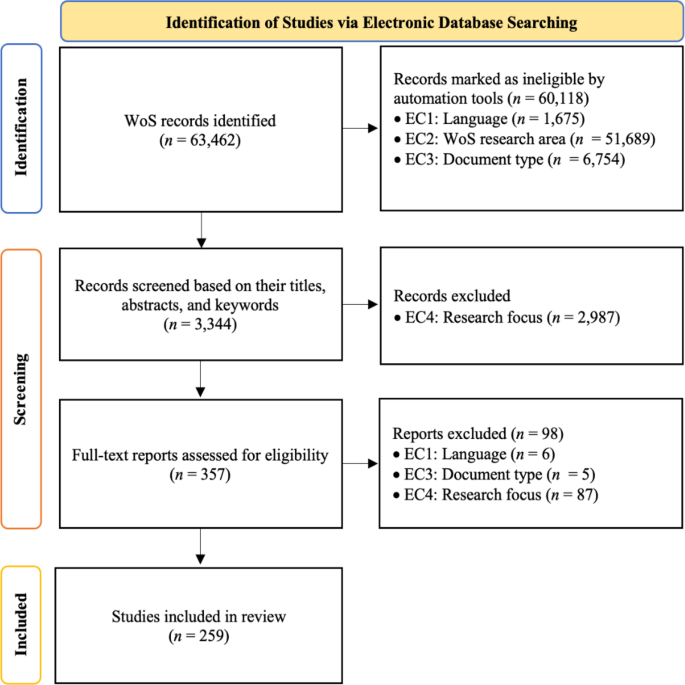

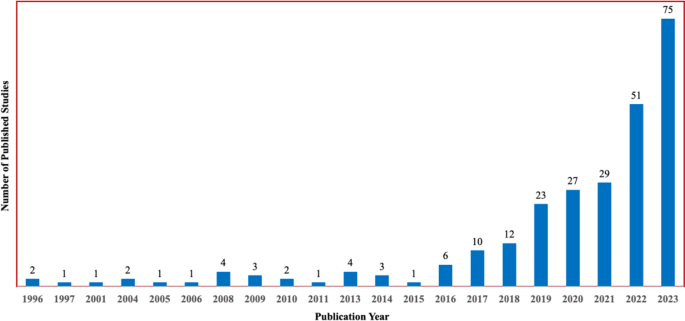

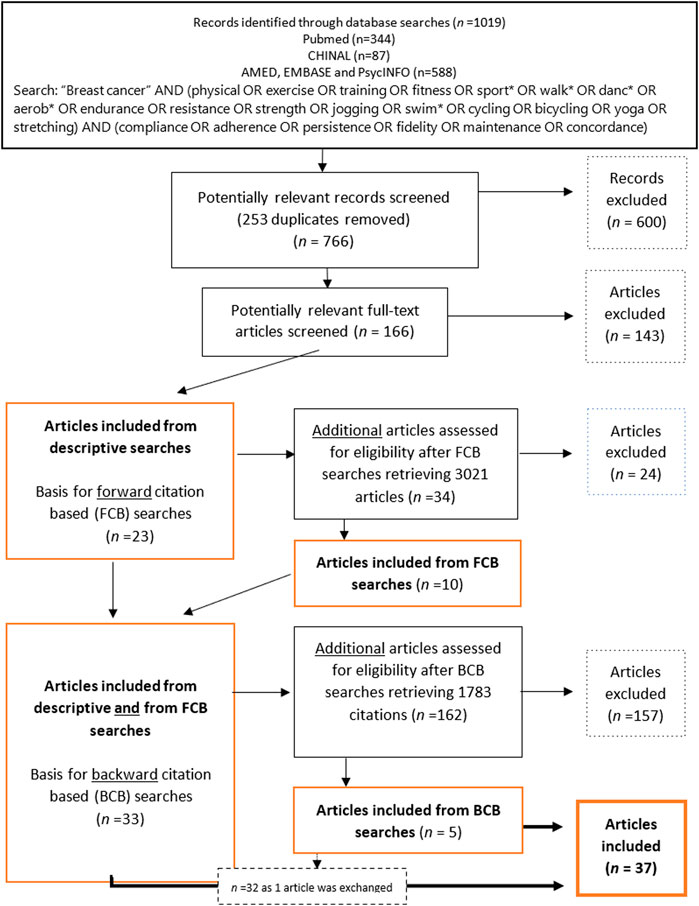

Review studies are vital for advancing knowledge in many scientific fields, including mathematics education, amid burgeoning publications. Based on an extensive consideration of existing review typologies, we conducted a meta-review and bibliometric analysis to provide a comprehensive overview of and deeper insights into review studies within mathematics education. After searching Web of Science, we identified 259 review studies, revealing a significant increase in such studies over the last five years. Systematic reviews were the most prevalent type, followed by meta-analyses, generic literature reviews, and scoping reviews. On average, the review studies had a sample size of 99, with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines commonly employed. Despite certain studies offering nuanced distinctions among review types, ambiguity persisted. Only about a quarter of the studies explicitly reported employing specific theoretical frameworks (particularly, technology, knowledge, and competence models). Co-authored publications were most common within American institutions and the leading countries are the United States, Germany, China, Australia, and England in publishing most review studies. Educational review journals, educational psychology journals, special education journals, educational technology journals, and mathematics education journals provided platforms for review studies, and prominent research topics included digital technologies, teacher education, mathematics achievement, and learning disabilities. In this study, we synthesised a range of reviews to facilitate readers’ comprehension of conceptual congruities and disparities across various review types, as well as to track current research trends. The results suggest that there is a need for discipline-specific standards and guidelines for different types of mathematics education reviews, which may lead to more high-quality review studies to enhance progress in mathematics education.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Comprehensive literature reviews serve as foundational pillars for advancing scholarly discourse, offering critical insights into existing research and shaping future inquiries across disciplines. In the realm of academic writing, spanning from journal articles to dissertations, literature reviews are highly regarded for their capacity to synthesize knowledge, identify gaps, and provide a cohesive framework for understanding complex topics (Boote & Beile, 2005 ). Moreover, reviews play a significant role in academia by setting new research agendas and informing decision-making processes in practice, policy, and society (Kunisch et al., 2023 ).

As empirical and theoretical research burgeons in diverse fields, the need for literature review studies has become even more pronounced, facilitating a deeper understanding of specific research areas or themes (Hart, 2018 ; Nane et al., 2023 ). Additional factors contributing to the popularity of review studies in recent years include the rise of specialized review journals (Kunisch et al., 2023 ), challenges associated with conducting various types of empirical studies during the prolonged COVID-19 crisis (Cevikbas & Kaiser, 2023 ), and a competitive research climate wherein factors such as impact factors and citations hold significant weight (Ketcham & Crawford, 2007 ). Review studies are particularly attractive as they often garner a substantial number of citations, thereby enhancing researchers’ visibility and scholarly impact (Grant & Booth, 2009 ; Taherdoost, 2023 ).

The importance of review studies has been duly acknowledged in mathematics education, as evidenced by the inclusion of review papers in thematically oriented special issues of journals such as ZDM– Mathematics Education (Kaiser & Schukajlow, 2024 ), which has been originally founded as review journal. Several upcoming or already published special issues of ZDM– Mathematics Education , which emphasise ‘reviews on important themes in mathematics education’, highlight the importance of review studies as valuable contributions to the field.

The proliferation of literature reviews has increased interest in developing typologies to categorise them and understand different literature review approaches (Grant & Booth, 2009 ; Paré et al., 2015 ; Schryen & Sperling, 2023 ). Despite its significance, there remains a notable lack of research aimed at comprehensively understanding review studies within the field of mathematics education from a meta-perspective. In response to this gap, we conducted a systematic meta-review with the aim of providing an overview of different types of review studies in mathematics education over the past few decades and consolidating insights from multiple high-level review studies (Becker & Oxman, 2008 ; Schryen & Sperling, 2023 ). Meta-reviews offer concise yet comprehensive synopses and curated lists of pertinent reviews, adeptly addressing the perennial challenge of balancing thorough coverage with focused specificity (Grant & Booth, 2009 ).

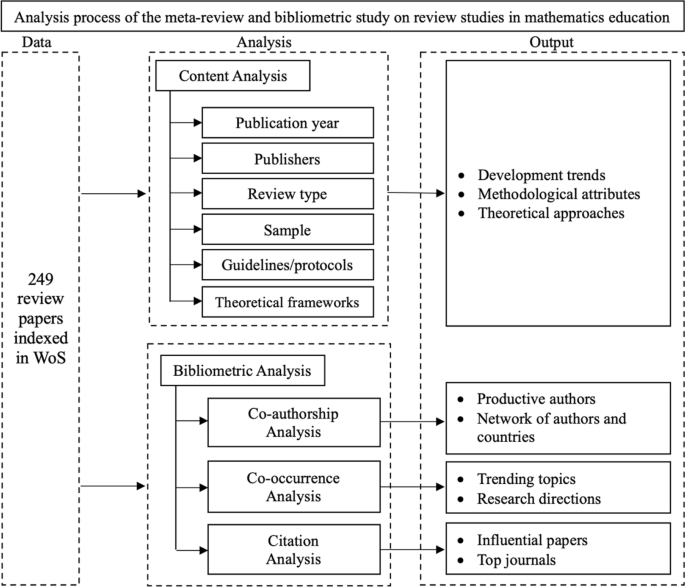

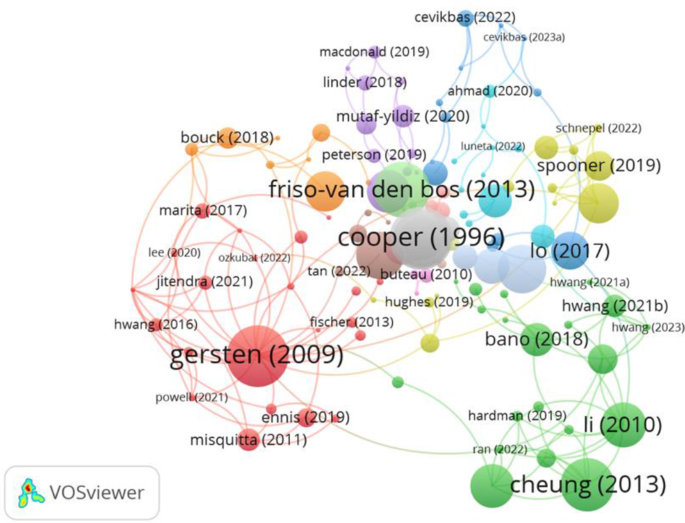

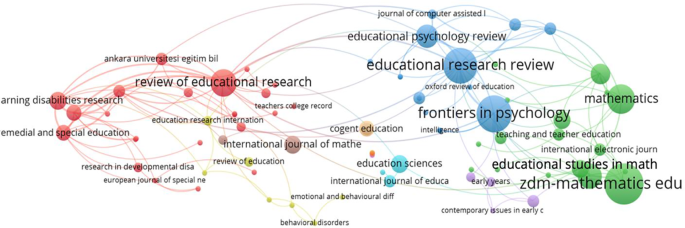

In addition, we applied bibliometric analysis as a valuable tool for identifying research trends, progress, reliable sources, and future directions within the field. The bibliometric analysis aids in identifying hot research topics and trends (Song et al., 2019 ), assessing progress, identifying reliable sources, recognising major contributors, and predicting future research success (Geng et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, it helps researchers to pinpoint potential topics, suitable institutions for cooperation, and potential scholars for scientific collaboration (Martínez et al., 2015 ). By combining a meta-review and bibliometric analysis, we aim to offer a comprehensive overview of and deeper insights into state-of-the-art review studies within mathematics education.

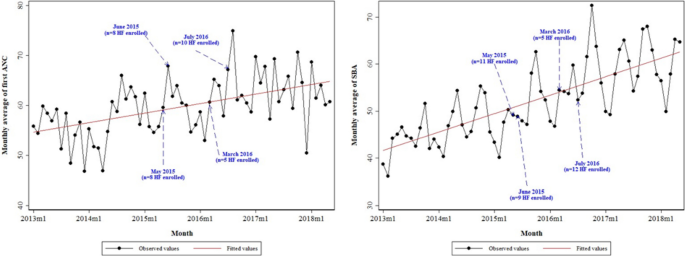

Specifically, we seek to understand how the distribution and development of literature review studies in mathematics education have evolved over the years, examining factors such as publication years, publishers, review types, sample sizes, and the use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks. Additionally, we aim to assess adherence to review study guidelines and protocols, providing insights into the rigor and quality of research methodologies employed, particularly in light of the lack of clear guidance on producing rigorous and impactful literature reviews (Kunisch et al., 2023 ).

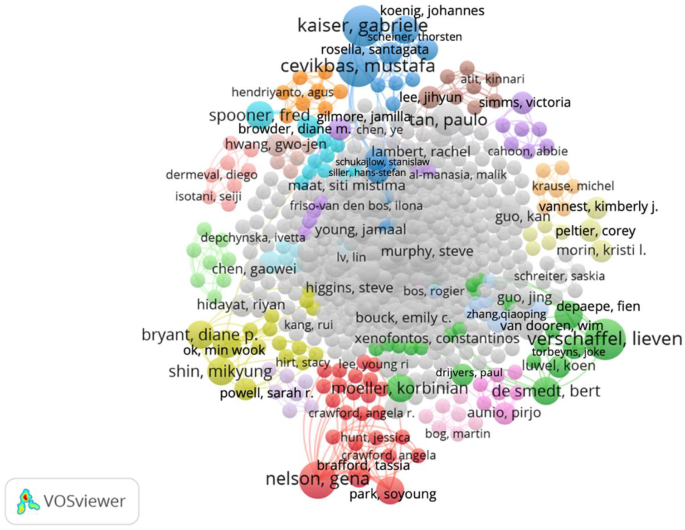

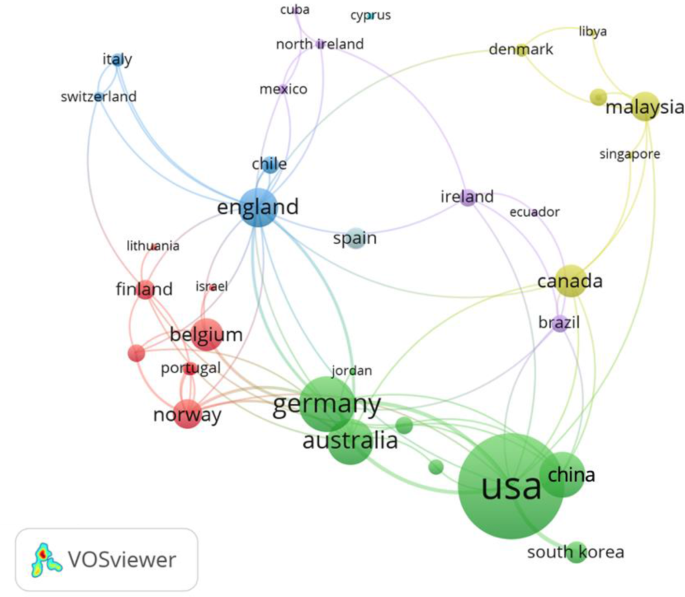

Furthermore, we endeavour to identify authors who have made contribution to the field of mathematics education through review studies, as well as those whose work is most frequently cited. We also identify co-authorship network analysis as understanding research networks allows researchers to identify potential collaborators and build partnerships with other scholars in various countries. Collaborative research endeavours can lead to enhanced research outcomes, broader dissemination of findings, and increased opportunities for funding and professional development. It can also highlight interdisciplinary connections and collaborations within and across fields, leading to innovative approaches and solutions to complex research questions (RQs) that transcend disciplinary boundaries.

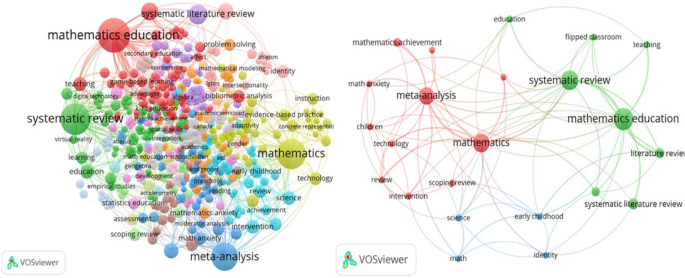

Moreover, we analysed the distribution of common keywords across review studies, identifying focal subjects and thematic areas prevalent in mathematics education research. This analysis can provide valuable insights into key topics and trends shaping the field, guiding future research directions and priorities.

Lastly, we identified the most cited review papers in mathematics education and the journals in which they have been published, recognizing seminal works and influential publications that have contributed to the advancement of the field.

Overall, in light of the preceding discourse, we addressed the following RQs to uncover the characteristics of review studies, identify research trends, and delineate future research directions in mathematics education:

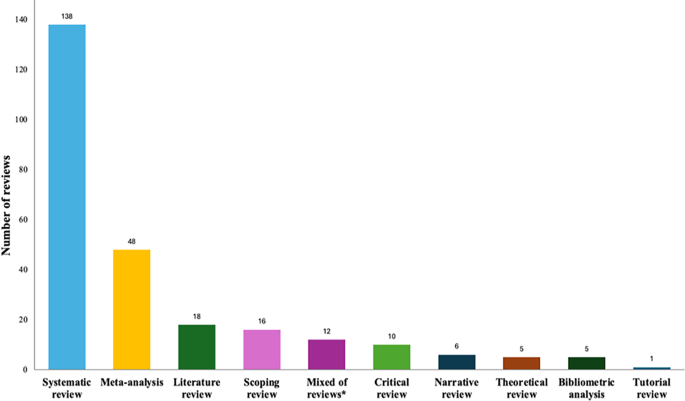

How can the distribution and development of review studies in mathematics education over time be characterised according to the number of manuscripts, publishers, review types, sample sizes, the use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks, and adherence to review study guidelines and protocols?

Which authors have contributed the largest number of review studies in mathematics education, and which authors’ review papers are most frequently cited in the literature?

From which countries are the authors of the review studies in mathematics education?

Which author keywords can be identified in the review studies in mathematics education, how are these keywords distributed across the analysed review studies, and which focal topics do these keywords indicate?

What are the most cited review papers in mathematics education, and in which journals have they been published?

2 Literature review studies and review typologies– background information

In this chapter, we provide a thorough analysis of different typologies for review studies, as we seek to elucidate the primary characteristics of various review studies conducted within mathematics education (Sect. 2.1 ). This effort led to the identification of 28 review types presented in Table 1 , which were used in the current study’s literature search processes to access existing review studies and the analysis of identified studies in the field of mathematics education. Furthermore, we discuss the advancement of guidelines and protocols, highlighting their role in shaping the conduct of review studies (Sect. 2.2). Finally, we conclude the chapter by underscoring the importance and potential impact of meta-reviews and bibliometric analyses in the context of mathematics education (Sect. 2.3).

2.1 Literature review typologies

Researchers have defined and emphasized different review types with distinct features, objectives, and methodologies. To address the challenge of ambiguous review categorisations, we conducted an extensive search and analysis of the literature on Web of Science (WoS) using the search strings ‘typology of reviews’ and ‘taxonomy of reviews’ to search the titles of studies. We focused particularly on influential theoretical, conceptual, and review papers discussing the taxonomy and typology of review studies and recent advances driven by scholars across diverse fields.

2.1.1 Seminal work by Grant and Booth ( 2009 ) on the discourse of literature review typologies

The categorisation of literature reviews has been profoundly influenced by the seminal work of Grant and Booth ( 2009 ), on which typologies of literature reviews are often based. Their paper garnered significant attention, with over 10,304 citations as of 20 April 2024 according to Google Scholar. Originally in the field of health information theory and practice, these authors founded their work on earlier approaches, notably Cochrane’s ( 1979 ) approach. Grant and Booth ( 2009 ) claimed that the developed typology could standardise the diverse terminology used. They distinguished 14 review types, which we summarise below, highlighting the main scope and search methodologies (Grant & Booth, 2009 , pp. 94–95):

A critical review ‘goes beyond mere description of identified articles and includes a degree of analysis and conceptual innovation’; no formalised or systematic approach is required because the aim of such a review is ‘to identify conceptual contributions to embody existing or derive new theory’.

A generic literature review incorporates ‘published materials that provide examination of recent of current literature’; comprehensive searching may or may not be necessary.

A mapping review/systematic mapping is used to ‘categorize existing literature’ and identify gaps in the research literature. The completeness of a search is important, but no formal quality assessment is needed.

A meta-analysis is a ‘technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results’; a comprehensive search is conducted based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

A mixed-studies review/mixed-methods review incorporates ‘a combination of review approaches, for example combining quantitative with qualitative research… and requires a very sensitive search’.

An overview is a generic term describing a ‘summary of the… literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics’; it may or may not include comprehensive searching and quality assessment.

A qualitative systematic review/qualitative evidence synthesis is a ‘method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies’, and it may involve selective sampling.

A rapid review comprises an ‘assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research’; a characteristic of such a review is that the ‘completeness of searching is determined by time constraints’.

A scoping review is a ‘preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research literature’, with the ‘completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints’.

A state-of-the-art review ‘tend[s] to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches’ and ‘aims for comprehensive searching of current literature’.

A systematic review ‘seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesise research evidence’ and should be comprehensive and based on inclusion/exclusion criteria.

A systematic search and review ‘combines [the] strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process’, typically addressing broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ based on ‘exhaustive, comprehensive searching’.

A systematised review ‘include[s] elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review’, ‘typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment’; it ‘may or may not include comprehensive searching’.

An umbrella review ‘specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document’ via ‘identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies’. ‘Primary studies’ refer to original research studies or individual studies conducted by researchers to gather data first-hand.

Booth with colleagues later expanded the typology by introducing the concept of a review family construct and amalgamating various types of reviews for further refinement, such as traditional reviews, systematic reviews, review of reviews, rapid reviews, mixed-methods reviews, and purpose-specific reviews (for details, see Sutton et al., 2019 ).

2.1.2 Further development of the review typologies

Many classifications for review studies have been developed, and in the following section, we present more recent approaches. Paré et al. ( 2015 ), in another highly cited study (2,059 Google Scholar citations as of 20 April 2024) considered seven recurrent dimensions: the goal of the review, the scope of the review questions, the search strategy, the nature of the primary sources, the explicitness of the study selection, quality appraisal, and the methods used to analyse/synthesise the findings. Based on these dimensions, they formulated nine different literature review types: narrative reviews, descriptive reviews, scoping/mapping reviews, meta-analyses, qualitative systematic reviews, umbrella reviews, critical reviews, theoretical reviews, and realist reviews.

In Paré et al.’s ( 2015 ) classification, the review categories that differ from Grant and Booth’s ( 2009 ) classification are theoretical reviews, realist reviews, narrative reviews, and descriptive reviews, which we therefore describe them briefly. A theoretical review draws on conceptual and empirical studies to develop a conceptual framework or model using structured approaches, such as taxonomies, to discover patterns or commonalities. The aim of a realist review (also called a meta-narrative review) is to formulate explanations; such reviews ‘are theory-driven interpretative reviews which were developed to inform, enhance, extend, or alternatively supplement conventional systematic reviews by making sense of heterogeneous evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that informs policy decision making’ (Paré et al., 2015 , p. 188). The purpose of a narrative review is to survey the existing literature on a particular subject or topic without necessarily seeking generalisations or cumulative insights from the material reviewed (Davies, 2000 ). Typically, such reviews do not detail the underpinning review processes or involve systematic and exhaustive searches of all pertinent literature. This category resembles Grant and Booth’s ( 2009 ) description of ‘literature reviews’ and overlaps with Samnani et al.’s ( 2017 ) narrative reviews, literature reviews, and overviews, resulting in a somewhat ambiguous typology. The aim of a descriptive review is to identify patterns and trends across a set of empirical studies within a specific research field, encompassing pre-existing propositions, theories, methodological approaches, or findings. To accomplish this objective, descriptive reviews collect, structure, and analyse numerical data that reflect the frequency distribution of research elements.

MacEntee ( 2019 ), Samnani et al. ( 2017 ), Schryen et al. ( 2020 ), and Taherdoost ( 2023 ) corroborated Grant and Booth’s ( 2009 ) and Paré et al.’s ( 2015 ) classifications, identifying various common review categories (see Table 1 ). In Samnani et al.’s ( 2017 ) classification, a distinct review type based on the previously mentioned categories is meta-synthesis , the aim of which is to provide explanations for phenomena, in contrast to meta-analysis, which focuses on quantitative outcomes.