Essays About Empathy: Top 5 Examples Plus Prompts

If you’re writing essays about empathy, check out our essay examples and prompts to get started.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share other people’s emotions. It is the very notion which To Kill a Mockingbird character Atticus Finch was driving at when he advised his daughter Scout to “climb inside [other people’s] skin and walk around in it.”

Being able to feel the joy and sorrow of others and see the world from their perspective are extraordinary human capabilities that shape our social landscape. But beyond its effect on personal and professional relationships, empathy motivates kind actions that can trickle positive change across society.

If you are writing an article about empathy, here are five insightful essay examples to inspire you:

1. Do Art and Literature Cultivate Empathy? by Nick Haslam

2. empathy: overrated by spencer kornhaber, 3. in our pandemic era, why we must teach our children compassion by rebecca roland, 4. why empathy is a must-have business strategy by belinda parmar, 5. the evolution of empathy by frans de waal, 1. teaching empathy in the classroom., 2. how can companies nurture empathy in the workplace, 3. how can we develop empathy, 4. how do you know if someone is empathetic, 5. does empathy spark helpful behavior , 6. empathy vs. sympathy., 7. empathy as a winning strategy in sports. , 8. is there a decline in human empathy, 9. is digital media affecting human empathy, 10. your personal story of empathy..

“Exposure to literature and the sorts of movies that do not involve car chases might nurture our capacity to get inside the skins of other people. Alternatively, people who already have well-developed empathic abilities might simply find the arts more engaging…”

Haslam, a psychology professor, laid down several studies to present his thoughts and analysis on the connection between empathy and art. While one study has shown that literary fiction can help develop empathy, there’s still lacking evidence to show that more exposure to art and literature can help one be more empathetic. You can also check out these essays about character .

“Empathy doesn’t even necessarily make day-to-day life more pleasant, they contend, citing research that shows a person’s empathy level has little or no correlation with kindness or giving to charity.”

This article takes off from a talk of psychology experts on a crusade against empathy. The experts argue that empathy could be “innumerate, parochial, bigoted” as it zooms one to focus on an individual’s emotions and fail to see the larger picture. This problem with empathy can motivate aggression and wars and, as such, must be replaced with a much more innate trait among humans: compassion.

“Showing empathy can be especially hard for kids… Especially in times of stress and upset, they may retreat to focusing more on themselves — as do we adults.”

Roland encourages fellow parents to teach their kids empathy, especially amid the pandemic, where kindness is needed the most. She advises parents to seize everyday opportunities by ensuring “quality conversations” and reinforcing their kids to view situations through other people’s lenses.

“Mental health, stress and burnout are now perceived as responsibilities of the organization. The failure to deploy empathy means less innovation, lower engagement and reduced loyalty, as well as diluting your diversity agenda.”

The spike in anxiety disorders and mental health illnesses brought by the COVID-19 pandemic has given organizations a more considerable responsibility: to listen to employees’ needs sincerely. Parmar underscores how crucial it is for a leader to take empathy as a fundamental business strategy and provides tips on how businesses can adjust to the new norm.

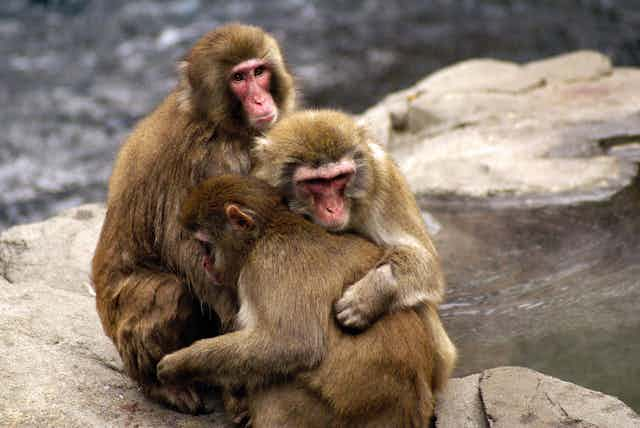

“The evolution of empathy runs from shared emotions and intentions between individuals to a greater self/other distinction—that is, an “unblurring” of the lines between individuals.”

The author traces the evolutionary roots of empathy back to our primate heritage — ultimately stemming from the parental instinct common to mammals. Ultimately, the author encourages readers to conquer “tribal differences” and continue turning to their emotions and empathy when making moral decisions.

10 Interesting Writing prompts on Essays About Empathy

Check out below our list of exciting prompts to help you buckle down to your writing:

This essay discuss teaching empathy in the classroom. Is this an essential skill that we should learn in school? Research how schools cultivate children’s innate empathy and compassion. Then, based on these schools’ experiences, provide tips on how other schools can follow suit.

An empathetic leader is said to help boost positive communication with employees, retain indispensable talent and create positive long-term outcomes. This is an interesting topic to research, and there are plenty of studies on this topic online with data that you can use in your essay. So, pick these best practices to promote workplace empathy and discuss their effectiveness.

Write down a list of deeds and activities people can take as their first steps to developing empathy. These activities can range from volunteering in their communities to reaching out to a friend in need simply. Then, explain how each of these acts can foster empathy and kindness.

Based on studies, list the most common traits, preferences, and behaviour of an empathetic person. For example, one study has shown that empathetic people prefer non-violent movies. Expound on this list with the support of existing studies. You can support or challenge these findings in this essay for a compelling argumentative essay. Make sure to conduct your research and cite all the sources used.

Empathy is a buzzword closely associated with being kind and helpful. However, many experts in recent years have been opining that it takes more than empathy to propel an act of kindness and that misplaced empathy can even lead to apathy. Gather what psychologists and emotional experts have been saying on this debate and input your analysis.

Empathy and sympathy have been used synonymously, even as these words differ in meaning. Enlighten your readers on the differences and provide situations that clearly show the contrast between empathy and sympathy. You may also add your take on which trait is better to cultivate.

Empathy has been deemed vital in building cooperation. A member who empathizes with the team can be better in tune with the team’s goals, cooperate effectively and help drive success. You may research how athletic teams foster a culture of empathy beyond the sports fields. Write about how coaches are integrating empathy into their coaching strategy.

Several studies have warned that empathy has been on a downward trend over the years. Dive deep into studies that investigate this decline. Summarize each and find common points. Then, cite the significant causes and recommendations in this study. You can also provide insights on whether this should cause alarm and how societies should address the problem.

There is a broad sentiment that social media has been driving people to live in a bubble and be less empathetic — more narcissistic. However, some point out that intensifying competition and increasing economic pressures are more to blame for reducing our empathetic feelings. Research and write about what experts have to say and provide a personal touch by adding your experience.

Acts of kindness abound every day. But sometimes, we fail to capture or take them for granted. Write about your unforgettable encounters with empathetic people. Then, create a storytelling essay to convey your personal view on empathy. This activity can help you appreciate better the little good things in life.

Check out our general resource of essay writing topics and stimulate your creative mind!

See our round-up of the best essay checkers to ensure your writing is error-free.

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Emotions & Feelings — Empathy

Empathy Essays

Hook examples for empathy essays, anecdotal hook.

"As I witnessed a stranger's act of kindness towards a struggling neighbor, I couldn't help but reflect on the profound impact of empathy—the ability to connect with others on a deeply human level."

Rhetorical Question Hook

"What does it mean to truly understand and share in the feelings of another person? The concept of empathy prompts us to explore the complexities of human connection."

Startling Statistic Hook

"Studies show that empathy plays a crucial role in building strong relationships, fostering teamwork, and reducing conflicts. How does empathy contribute to personal and societal well-being?"

"'Empathy is seeing with the eyes of another, listening with the ears of another, and feeling with the heart of another.' This profound quote encapsulates the essence of empathy and its significance in human interactions."

Historical Hook

"From ancient philosophies to modern psychology, empathy has been a recurring theme in human thought. Exploring the historical roots of empathy provides deeper insights into its importance."

Narrative Hook

"Join me on a journey through personal stories of empathy, where individuals bridge cultural, social, and emotional divides. This narrative captures the essence of empathy in action."

Psychological Impact Hook

"How does empathy impact mental health, emotional well-being, and interpersonal relationships? Analyzing the psychological aspects of empathy adds depth to our understanding."

Social Empathy Hook

"In a world marked by diversity and societal challenges, empathy plays a crucial role in promoting understanding and social cohesion. Delving into the role of empathy in society offers important insights."

Empathy in Literature and Arts Hook

"How has empathy been depicted in literature, art, and media throughout history? Exploring its representation in the creative arts reveals its enduring significance in culture."

Teaching Empathy Hook

"What are effective ways to teach empathy to individuals of all ages? Examining strategies for nurturing empathy offers valuable insights for education and personal growth."

Raymond Carver's "Cathedral": Summary

Examples of hardships in my life, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Choice of Compassion: Cultivating Empathy

How empathy and understanding others is important for our society, the key components of empathy, importance of the empathy in my family, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Importance of Promoting Empathy in Children

Steps for developing empathy in social situations, the impacts of digital media on empathy, the contributions of technology to the decline of human empathy, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Role of Empathy in Justice System

Importance of empathy for blind people, the most effective method to tune in with empathy in the classroom, thr way acts of kindness can change our lives, the power of compassion and its main aspects, compassion and empathy in teaching, acts of kindness: importance of being kind, the concept of empathy in "do androids dream of electric sheep", the vital values that comprise the definition of hero, critical analysis of kwame anthony appiah’s theory of conversation, development of protagonist in philip k. novel "do androids dream of electric sheep", talking about compassion in 100 words, barbara lazear aschers on compassion, my purpose in life is to help others: helping behavior, humility and values, adolescence stage experience: perspective taking and empathy, random act of kindness, helping others in need: importance of prioritizing yourself, toni cade bambara the lesson summary, making a positive impact on others: the power of influence.

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position.

Types of empathy include cognitive empathy, emotional (or affective) empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Empathy-based socialization differs from inhibition of egoistic impulses through shaping, modeling, and internalized guilt. Empathetic feelings might enable individuals to develop more satisfactory interpersonal relations, especially in the long-term. Empathy-induced altruism can improve attitudes toward stigmatized groups, and to improve racial attitudes, and actions toward people with AIDS, the homeless, and convicts. It also increases cooperation in competitive situations.

Empathetic people are quick to help others. Painkillers reduce one’s capacity for empathy. Anxiety levels influence empathy. Meditation and reading may heighten empathy.

Relevant topics

- Forgiveness

- Responsibility

- Winter Break

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Understanding others’ feelings: what is empathy and why do we need it?

Senior Lecturer in Social Neuroscience, Monash University

Disclosure statement

Pascal Molenberghs receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award: DE130100120) and Heart Foundation (Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship: 1000458).

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is the introductory essay in our series on understanding others’ feelings. In it we will examine empathy, including what it is, whether our doctors need more of it, and when too much may not be a good thing.

Empathy is the ability to share and understand the emotions of others. It is a construct of multiple components, each of which is associated with its own brain network . There are three ways of looking at empathy.

First there is affective empathy. This is the ability to share the emotions of others. People who score high on affective empathy are those who, for example, show a strong visceral reaction when watching a scary movie.

They feel scared or feel others’ pain strongly within themselves when seeing others scared or in pain.

Cognitive empathy, on the other hand, is the ability to understand the emotions of others. A good example is the psychologist who understands the emotions of the client in a rational way, but does not necessarily share the emotions of the client in a visceral sense.

Finally, there’s emotional regulation. This refers to the ability to regulate one’s emotions. For example, surgeons need to control their emotions when operating on a patient.

Another way to understand empathy is to distinguish it from other related constructs. For example, empathy involves self-awareness , as well as distinction between the self and the other. In that sense it is different from mimicry, or imitation.

Many animals might show signs of mimicry or emotional contagion to another animal in pain. But without some level of self-awareness, and distinction between the self and the other, it is not empathy in a strict sense. Empathy is also different from sympathy, which involves feeling concern for the suffering of another person and a desire to help.

That said, empathy is not a unique human experience. It has been observed in many non-human primates and even rats .

People often say psychopaths lack empathy but this is not always the case. In fact, psychopathy is enabled by good cognitive empathic abilities - you need to understand what your victim is feeling when you are torturing them. What psychopaths typically lack is sympathy. They know the other person is suffering but they just don’t care.

Research has also shown those with psychopathic traits are often very good at regulating their emotions .

Why do we need it?

Empathy is important because it helps us understand how others are feeling so we can respond appropriately to the situation. It is typically associated with social behaviour and there is lots of research showing that greater empathy leads to more helping behaviour.

However, this is not always the case. Empathy can also inhibit social actions, or even lead to amoral behaviour . For example, someone who sees a car accident and is overwhelmed by emotions witnessing the victim in severe pain might be less likely to help that person.

Similarly, strong empathetic feelings for members of our own family or our own social or racial group might lead to hate or aggression towards those we perceive as a threat. Think about a mother or father protecting their baby or a nationalist protecting their country.

People who are good at reading others’ emotions, such as manipulators, fortune-tellers or psychics, might also use their excellent empathetic skills for their own benefit by deceiving others.

Interestingly, people with higher psychopathic traits typically show more utilitarian responses in moral dilemmas such as the footbridge problem. In this thought experiment, people have to decide whether to push a person off a bridge to stop a train about to kill five others laying on the track.

The psychopath would more often than not choose to push the person off the bridge. This is following the utilitarian philosophy that holds saving the life of five people by killing one person is a good thing. So one could argue those with psychopathic tendencies are more moral than normal people – who probably wouldn’t push the person off the bridge – as they are less influenced by emotions when making moral decisions.

How is empathy measured?

Empathy is often measured with self-report questionnaires such as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) or Questionnaire for Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE).

These typically ask people to indicate how much they agree with statements that measure different types of empathy.

The QCAE, for instance, has statements such as, “It affects me very much when one of my friends is upset”, which is a measure of affective empathy.

Cognitive empathy is determined by the QCAE by putting value on a statement such as, “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision.”

Using the QCAE, we recently found people who score higher on affective empathy have more grey matter, which is a collection of different types of nerve cells, in an area of the brain called the anterior insula.

This area is often involved in regulating positive and negative emotions by integrating environmental stimulants – such as seeing a car accident - with visceral and automatic bodily sensations.

We also found people who score higher on cognitive empathy had more grey matter in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

This area is typically activated during more cognitive processes, such as Theory of Mind, which is the ability to attribute mental beliefs to yourself and another person. It also involves understanding that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives different from one’s own.

Can empathy be selective?

Research shows we typically feel more empathy for members of our own group , such as those from our ethnic group. For example, one study scanned the brains of Chinese and Caucasian participants while they watched videos of members of their own ethnic group in pain. They also observed people from a different ethnic group in pain.

The researchers found that a brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex, which is often active when we see others in pain, was less active when participants saw members of ethnic groups different from their own in pain.

Other studies have found brain areas involved in empathy are less active when watching people in pain who act unfairly . We even see activation in brain areas involved in subjective pleasure , such as the ventral striatum, when watching a rival sport team fail.

Yet, we do not always feel less empathy for those who aren’t members of our own group. In our recent study , students had to give monetary rewards or painful electrical shocks to students from the same or a different university. We scanned their brain responses when this happened.

Brain areas involved in rewarding others were more active when people rewarded members of their own group, but areas involved in harming others were equally active for both groups.

These results correspond to observations in daily life. We generally feel happier if our own group members win something, but we’re unlikely to harm others just because they belong to a different group, culture or race. In general, ingroup bias is more about ingroup love rather than outgroup hate.

Yet in some situations, it could be helpful to feel less empathy for a particular group of people. For example, in war it might be beneficial to feel less empathy for people you are trying to kill, especially if they are also trying to harm you.

To investigate, we conducted another brain imaging study . We asked people to watch videos from a violent video game in which a person was shooting innocent civilians (unjustified violence) or enemy soldiers (justified violence).

While watching the videos, people had to pretend they were killing real people. We found the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, typically active when people harm others, was active when people shot innocent civilians. The more guilt participants felt about shooting civilians, the greater the response in this region.

However, the same area was not activated when people shot the soldier that was trying to kill them.

The results provide insight into how people regulate their emotions. They also show the brain mechanisms typically implicated when harming others become less active when the violence against a particular group is seen as justified.

This might provide future insights into how people become desensitised to violence or why some people feel more or less guilty about harming others.

Our empathetic brain has evolved to be highly adaptive to different types of situations. Having empathy is very useful as it often helps to understand others so we can help or deceive them, but sometimes we need to be able to switch off our empathetic feelings to protect our own lives, and those of others.

Tomorrow’s article will look at whether art can cultivate empathy.

- Theory of mind

- Emotional contagion

- Understanding others' feelings

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Student Wellbeing Officer

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Reflective Essay on Empathy

The virtue I feel I need in my life is empathy. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. Empathy is caring for another person, and understanding what they are going through. I struggle with empathy. I have a hard time understanding what another is going through, especially if I have not experienced the situation before.

Empathy is a way to show you care for one another. Without empathy, you can come across as ignorant and rude. I know at times I have come across that way because I did not know how to show empathy for the person. Working on showing empathy can teach me how to express care for what another person is dealing with. Empathy is needed for a person to become their best self. This is because when we interact with others, we come off as friendly and caring. Coming off as rude or ignorant is not what creates a “good person”. I would be considered a “good person”, someone who cares for one another.

If I possessed more empathy in my life, I could help and show care for more people. I could help those who are going through hard times, by showing understanding of what they are going through. I could help care for another person. I feel empathy is needed in everyone's life, especially mine. When I possess more empathy, I show more compassion and make other people feel better. By showing more people you care about them, you are showing love. God shows his love to us, therefore we should show others we love and care for them. By showing I love and care for others this is helping me become a good moral person.

Empathy would help me to become a better person. By changing bad habits, and teaching myself to understand others situations, I improve my character. BY improving my character, I can also help others improve their character. By showing more people empathy, I not only help myself but also make a positive impact on others around me.

The second virtue I feel I need in my life is openness. Openness is being accepting of ideas and new changes. Openness allows you to experience new ideas and changes instead of something you already know or understand. Openness is benign, open to trying new activities, listening to new ideas, and even trying new foods. When you are open to the world, you can experience many new things, and experience can improve who you are as a person.

I struggle with not being open to new ideas or actions. I like experiencing the same, and not trying something new. If I became more open I could expand who I am. I do not like trying new foods. I have a mindset that I feel it's okay to always eat the same food over and over again without trying something else. I am not open to new ideas, and would like to work on that. I am also not always open to other people's ideas. It can be hard for me to feel open about trying someone else's idea because I feel as if I already have the solution to the problem. This can cause me to be closed off to other people's ideas, and I do not want that. This is why I would want to work on being more open with others, and new ideas.

If I became more open, a lot would change in my character. Being open would lead me to more learning experiences, and learning experiences would help me grow into a better person. Also, if I were more open, I could view solutions to a problem from someone else's point of view. That would help me to learn how others think differently than me. Seeing how others think differently than me would help me to realize the many different ways of dealing with problems. Being more open would also show me other people's thoughts/options. It would lead me to have a different view from my own thoughts/opinions.

If I were to be more open, I would learn more about the world and people around me. Knowing more about everything around me would help me to improve myself into a more open person. A person who would listen to others ideas. A person who would not mind trying something new. Being open would teach me lessons, and make myself more awhere.

Related Samples

- Reflection Essay about Being an Outsider

- Republic by Plato Analysis Essay

- Philosophy Essay on Imitation

- The Dashing Depression Rate Among High Schoolers

- Personal Experience Essay: Being Black Girl

- Essay On Effects Of Social Media On Teen Self Esteem

- Philosophy of Education Essay Example

- John Jefferson And Johan Von Herder Essay Example

- The Kindness Shown Around Philosophy Essay Example

- The Impact of Society Essay Example

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Empathy?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Bailey Mariner

Empathy is the ability to emotionally understand what other people feel, see things from their point of view, and imagine yourself in their place. Essentially, it is putting yourself in someone else's position and feeling what they are feeling.

Empathy means that when you see another person suffering, such as after they've lost a loved one , you are able to instantly envision yourself going through that same experience and feel what they are going through.

While people can be well-attuned to their own feelings and emotions, getting into someone else's head can be a bit more difficult. The ability to feel empathy allows people to "walk a mile in another's shoes," so to speak. It permits people to understand the emotions that others are feeling.

Press Play for Advice on Empathy

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring empathy expert Dr. Kelsey Crowe, shares how you can show empathy to someone who is going through a hard time. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Signs of Empathy

For many, seeing another person in pain and responding with indifference or even outright hostility seems utterly incomprehensible. But the fact that some people do respond in such a way clearly demonstrates that empathy is not necessarily a universal response to the suffering of others.

If you are wondering whether you are an empathetic person, here are some signs that show that you have this tendency:

- You are good at really listening to what others have to say.

- People often tell you about their problems.

- You are good at picking up on how other people are feeling.

- You often think about how other people feel.

- Other people come to you for advice.

- You often feel overwhelmed by tragic events.

- You try to help others who are suffering.

- You are good at telling when people aren't being honest .

- You sometimes feel drained or overwhelmed in social situations.

- You care deeply about other people.

- You find it difficult to set boundaries in your relationships.

Are You an Empath? Take the Quiz!

Our fast and free empath quiz will let you know if your feelings and behaviors indicate high levels of traits commonly associated with empaths.

Types of Empathy

There are several types of empathy that a person may experience. The three types of empathy are:

- Affective empathy involves the ability to understand another person's emotions and respond appropriately. Such emotional understanding may lead to someone feeling concerned for another person's well-being, or it may lead to feelings of personal distress.

- Somatic empathy involves having a physical reaction in response to what someone else is experiencing. People sometimes physically experience what another person is feeling. When you see someone else feeling embarrassed, for example, you might start to blush or have an upset stomach.

- Cognitive empathy involves being able to understand another person's mental state and what they might be thinking in response to the situation. This is related to what psychologists refer to as the theory of mind or thinking about what other people are thinking.

Empathy vs. Sympathy vs. Compassion

While sympathy and compassion are related to empathy, there are important differences. Compassion and sympathy are often thought to be more of a passive connection, while empathy generally involves a much more active attempt to understand another person.

Uses for Empathy

Being able to experience empathy has many beneficial uses.

- Empathy allows you to build social connections with others . By understanding what people are thinking and feeling, you are able to respond appropriately in social situations. Research has shown that having social connections is important for both physical and psychological well-being.

- Empathizing with others helps you learn to regulate your own emotions . Emotional regulation is important in that it allows you to manage what you are feeling, even in times of great stress, without becoming overwhelmed.

- Empathy promotes helping behaviors . Not only are you more likely to engage in helpful behaviors when you feel empathy for other people, but other people are also more likely to help you when they experience empathy.

Potential Pitfalls of Empathy

Having a great deal of empathy makes you concerned for the well-being and happiness of others. It also means, however, that you can sometimes get overwhelmed, burned out , or even overstimulated from always thinking about other people's emotions. This can lead to empathy fatigue.

Empathy fatigue refers to the exhaustion you might feel both emotionally and physically after repeatedly being exposed to stressful or traumatic events . You might also feel numb or powerless, isolate yourself, and have a lack of energy.

Empathy fatigue is a concern in certain situations, such as when acting as a caregiver . Studies also show that if healthcare workers can't balance their feelings of empathy (affective empathy, in particular), it can result in compassion fatigue as well.

Other research has linked higher levels of empathy with a tendency toward emotional negativity , potentially increasing your risk of empathic distress. It can even affect your judgment, causing you to go against your morals based on the empathy you feel for someone else.

Impact of Empathy

Your ability to experience empathy can impact your relationships. Studies involving siblings have found that when empathy is high, siblings have less conflict and more warmth toward each other. In romantic relationships, having empathy increases your ability to extend forgiveness .

Not everyone experiences empathy in every situation. Some people may be more naturally empathetic in general, but people also tend to feel more empathetic toward some people and less so toward others. Some of the factors that play a role in this tendency include:

- How you perceive the other person

- How you attribute the other individual's behaviors

- What you blame for the other person's predicament

- Your past experiences and expectations

Research has found that there are gender differences in the experience and expression of empathy, although these findings are somewhat mixed. Women score higher on empathy tests, and studies suggest that women tend to feel more cognitive empathy than men.

At the most basic level, there appear to be two main factors that contribute to the ability to experience empathy: genetics and socialization. Essentially, it boils down to the age-old relative contributions of nature and nurture .

Parents pass down genes that contribute to overall personality, including the propensity toward sympathy, empathy, and compassion. On the other hand, people are also socialized by their parents, peers, communities, and society. How people treat others, as well as how they feel about others, is often a reflection of the beliefs and values that were instilled at a very young age.

Barriers to Empathy

Some people lack empathy and, therefore, aren't able to understand what another person may be experiencing or feeling. This can result in behaviors that seem uncaring or sometimes even hurtful. For instance, people with low affective empathy have higher rates of cyberbullying .

A lack of empathy is also one of the defining characteristics of narcissistic personality disorder . Though, it is unclear whether this is due to a person with this disorder having no empathy at all or having more of a dysfunctional response to others.

A few reasons why people sometimes lack empathy include cognitive biases, dehumanization, and victim-blaming.

Cognitive Biases

Sometimes the way people perceive the world around them is influenced by cognitive biases . For example, people often attribute other people's failures to internal characteristics, while blaming their own shortcomings on external factors.

These biases can make it difficult to see all the factors that contribute to a situation. They also make it less likely that people will be able to see a situation from the perspective of another.

Dehumanization

Many also fall victim to the trap of thinking that people who are different from them don't feel and behave the same as they do. This is particularly common in cases when other people are physically distant.

For example, when they watch reports of a disaster or conflict in a foreign land, people might be less likely to feel empathy if they think that those who are suffering are fundamentally different from themselves.

Victim Blaming

Sometimes, when another person has suffered a terrible experience, people make the mistake of blaming the victim for their circumstances. This is the reason that victims of crimes are often asked what they might have done differently to prevent the crime.

This tendency stems from the need to believe that the world is a fair and just place. It is the desire to believe that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get—and it can fool you into thinking that such terrible things could never happen to you.

Causes of Empathy

Human beings are certainly capable of selfish, even cruel, behavior. A quick scan of the news quickly reveals numerous unkind, selfish, and heinous actions. The question, then, is why don't we all engage in such self-serving behavior all the time? What is it that causes us to feel another's pain and respond with kindness ?

The term empathy was first introduced in 1909 by psychologist Edward B. Titchener as a translation of the German term einfühlung (meaning "feeling into"). Several different theories have been proposed to explain empathy.

Neuroscientific Explanations

Studies have shown that specific areas of the brain play a role in how empathy is experienced. More recent approaches focus on the cognitive and neurological processes that lie behind empathy. Researchers have found that different regions of the brain play an important role in empathy, including the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula.

Research suggests that there are important neurobiological components to the experience of empathy. The activation of mirror neurons in the brain plays a part in the ability to mirror and mimic the emotional responses that people would feel if they were in similar situations.

Functional MRI research also indicates that an area of the brain known as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) plays a critical role in the experience of empathy. Studies have found that people who have damage to this area of the brain often have difficulty recognizing emotions conveyed through facial expressions .

Emotional Explanations

Some of the earliest explorations into the topic of empathy centered on how feeling what others feel allows people to have a variety of emotional experiences. The philosopher Adam Smith suggested that it allows us to experience things that we might never otherwise be able to fully feel.

This can involve feeling empathy for both real people and imaginary characters. Experiencing empathy for fictional characters, for example, allows people to have a range of emotional experiences that might otherwise be impossible.

Prosocial Explanations

Sociologist Herbert Spencer proposed that empathy served an adaptive function and aided in the survival of the species. Empathy leads to helping behavior, which benefits social relationships. Humans are naturally social creatures. Things that aid in our relationships with other people benefit us as well.

When people experience empathy, they are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors that benefit other people. Things such as altruism and heroism are also connected to feeling empathy for others.

Tips for Practicing Empathy

Fortunately, empathy is a skill that you can learn and strengthen. If you would like to build your empathy skills, there are a few things that you can do:

- Work on listening to people without interrupting

- Pay attention to body language and other types of nonverbal communication

- Try to understand people, even when you don't agree with them

- Ask people questions to learn more about them and their lives

- Imagine yourself in another person's shoes

- Strengthen your connection with others to learn more about how they feel

- Seek to identify biases you may have and how they affect your empathy for others

- Look for ways in which you are similar to others versus focusing on differences

- Be willing to be vulnerable, opening up about how you feel

- Engage in new experiences, giving you better insight into how others in that situation may feel

- Get involved in organizations that push for social change

A Word From Verywell

While empathy might be lacking in some, most people are able to empathize with others in a variety of situations. This ability to see things from another person's perspective and empathize with another's emotions plays an important role in our social lives. Empathy allows us to understand others and, quite often, compels us to take action to relieve another person's suffering.

Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health . Curr Opin Psychiatry . 2008;21(2):201‐205. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89

Cleveland Clinic. Empathy fatigue: How stress and trauma can take a toll on you .

Duarte J, Pinto-Bouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses' empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study . Int J Nursing Stud . 2016;60:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015

Chikovani G, Babuadze L, Iashvili N, Gvalia T, Surguladze S. Empathy costs: Negative emotional bias in high empathisers . Psychiatry Res . 2015;229(1-2):340-346. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.001

Lam CB, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. Sibling relationships and empathy across the transition to adolescence . J Youth Adolescen . 2012;41:1657-1670. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9781-8

Kimmes JG, Durtschi JA. Forgiveness in romantic relationships: The roles of attachment, empathy, and attributions . J Marital Family Ther . 2016;42(4):645-658. doi:10.1111/jmft.12171

Kret ME, De Gelder B. A review on sex difference in processing emotional signals . Neuropsychologia . 2012; 50(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022

Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H. Is cyberbullying related to lack of empathy and social-emotional problems? Int J Develop Sci . 2013;7(3-4):161-166. doi:10.3233/DEV-130124

Baskin-Sommers A, Krusemark E, Ronningstam E. Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: From clinical and empirical perspectives . Personal Dis Theory Res Treat . 2014;5(3):323-333. doi:10.1037/per0000061

Decety, J. Dissecting the neural mechanisms mediating empathy . Emotion Review . 2011; 3(1): 92-108. doi:10.1177/1754073910374662

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J, Perry D. Two systems for empathy: A double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions . Brain . 2009;132(PT3): 617-627. doi:10.1093/brain/awn279

Hillis AE. Inability to empathize: Brain lesions that disrupt sharing and understanding another's emotions . Brain . 2014;137(4):981-997. doi:10.1093/brain/awt317

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Self-Empathy Is Required to Empathize With Others

Creating a receptive space to help you empathize without projecting..

Posted March 5, 2021 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

In our previous post, " The Light and Dark Side of Empathy, " we wrote about how your motivations and intentions determine whether you use empathy to help or to harm. Self-empathy, as a practice, guides you to tune in to your inner world and to understand, or even modify, motivations and intentions.

By choosing to practice self-empathy, as a deeply personal exploration, you observe and integrate your own experiences. You bring awareness to your inner experiential, emotional and mental state. A part of yourself observes the aspect of yourself that experiences in an empathic manner. You create a space within yourself by bringing your mind into the inner world of your own experiences of thought and feeling and by suspending judgments you may have about yourself (Jordan, 1994). This inner space is open, expansive, and receptive.

Your inner life may be noisy with random fragments of thought and feeling. The practice of self-empathy orders these fragments.

After going through the process of noticing, centering, sensing, suspending judgment, intention setting, and attending to self, you will have the tools to reopen yourself to the situation at hand with conscious equanimity. You created a receptive space to the experiences of others which prepares you to empathize without the often unconscious habit of projecting yourself onto them.

This is what the practice is about. You need to deal with tensions at work, you need to get your job done, and you are hardly ever independent of the people around you. Although you might be willing and inclined to empathize with others, you will not successfully do so if you are not aware of your own influence on the situation as it evolves. Coming back to your own inner experiences and understanding that they are intrinsically yours to work with, will help you to create space for the experience and action of others.

Is empathizing with others different from empathizing with yourself?

Yes and no. Yes, because empathizing with others is empathizing with the inherently unknowable experience of other people. Their experiences, thoughts, and feelings are not yours. And more importantly, they are not meant to be either. Empathizing with others does not mean experiencing what others are going through. It is meant to attentively tune into their expressions of those experiences. To open up to their perspectives on a given situation, to broaden your own views on it, and to hold a space for others to be as they are.

But empathizing with others is also not different from empathizing with yourself.

Although the practices are different, they require a similar reflective presence: noticing, taking ethical responsibility, suspending judgment, setting intentions, and attending to others.

Self-empathy helps you to develop agency, the awareness of yourself as being the initiator of actions, desires, thoughts, and feelings (Decety & Jackson, 2004). With self-empathy you become aware of your own experiential state in the moment, enabling you to differentiate your own emotional experience from the experience of someone else. This differentiation prepares you to face professional and interpersonal challenges ahead.

We consider empathy to be useful as a means to an end. You may choose to practice empathy quietly in your own life, in interaction with the people close to you. But it becomes truly powerful when people acting together to fulfill a cause, engage in mutual empathic interaction. This has led us to develop an empathic method of structured interaction for people working together: Empathic Intervision.

Empathic Intervision: Practicing empathy with others

Empathic Intervision (Niezink & Train, 2020) is an organised peer-support method for people working together to identify opportunities and co-create solutions to challenges. It includes exercises in integrative empathy, to help you to engage beyond cultural differences, to listen and hear each other's experiences, thoughts, and feelings about a topic and to identify and take the perspective of others. The process can either be guided by an external facilitator or it can be self-organized. It requires you to maintain the reflective presence attained during the self-empathy exercise. However, the presence of noticing, taking ethical responsibility, suspending judgment, setting intentions, and attending is focussed on others.

In the Empathic Intervision too, each person engages a self-empathy exercise. Yet prior to self-empathy, participants set a collective intention. Since empathy is applied here as a means to an end, the intention guides the process towards an identified outcome. It ensures that participants are able to identify a shared goal for the group.

This introduction and setting of the scene are followed by three layers of empathy practice, all directed towards the collective intention set at the start of the meeting. They are kinesthetic, reflective, and imaginative empathy.

Kinesthetic empathy, the capacity to participate in somebody’s movement, or their sensory experience of movement (Niezink & Train, 2020) . This helps you to connect with others through coordination and synchronization. With kinesthetic empathy, you explore and become more aware of how you influence each other’s physical space. Kinesthetic empathy practices support the role of coordination and synchronization in empathy and enable people to hold physical space for others, hence experience the effects of being "seen" and "followed" in action.

Reflective empathy enables you to deepen your connection with others through literal reflection and advanced reflective empathy dialogue. Reflective empathy helps you to explore difficult or stressful situations without losing sight of your own self. Problems are clarified, and listening is intensified, through reflective empathic dialogue.

Imaginative empathy uses imagination and "as-if" acting to enable you to understand the perspectives of others you are working with and to experience the effects of having a problem explored from multiple perspectives. It is used as a means to explore difficult or stressful situations or to diversify perspectives and enable creativity .

The fifth and last aspect of Empathic Intervision is empathic creativity (Niezink & Train, 2020). During the full intervision process, the empathic practices described above guide and stimulate actions and reactions. The act of empathizing awakens creative insights. People become aroused in a particular way. These moments highlight significant change events and are ripe to be harvested and preserved. The consequences of empathic interactions can be quickly forgotten or get lost if not brought to attention . Empathic creativity is the practice of preserving that which is created and brings possible solutions to the issue at hand. As the final step in the intervision process, the gathered insights are transformed into actionable outcomes.

Self-empathy provides a foundation and is a prerequisite for each of the other four integrative empathy practices. As a deeply personal and transformative practice, it guides you to create a receptive space to empathize with others.

If you enjoyed the stunning artwork we have used throughout this series of posts, we encourage you to have a look at the fantastic work of our friend Candace Charlton . The human form, in particular the portrait, is the main focus of Charlton’s work. She strives to discover and reveal the mystery and depth of the human psyche in her intensively studied portraits and figurative compositions.

Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2004 Jun;3(2):71-100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187.

Jordan, Judith. (1997). Relational development through mutual empathy. doi:10.1037/10226-015

Niezink, L.W. & Train, K.J. (2020). Empathic Intervision: A Peer-to-Peer Practice. France & South Africa: Empathic Intervision. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339484113_Empathic_Intervision… [accessed Mar 2, 2021].

Lidewij Niezink, Ph.D., and Katherine Train, Ph.D., are the co-founders of Empathic Intervision.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Reflections on Empathy

- by Mayte Picco-Kline

- on September 1, 2020

The word “empathy” came to me through diverse situations and sparked my enthusiasm to share a few thoughts on the topic in the context of a “Life Lived Forward.”

Empathy is a broad concept that refers to the cognitive and emotional reactions of an individual to the observed, wide range of experiences of another. Emotion researchers generally define empathy as the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling. It is usually associated with being able to “put ourselves in another person’s shoes” – understanding the other person’s perspective and appreciation of reality so we can better respond to the situation and the potential to develop compassion and offer a helping hand.

Becoming empathetic requires thinking beyond ourselves and our personal concerns, in the understanding that others concerns and points of view are as valuable as our own. We enhance our ability to do so by opening to the varied ways in which others approach life. Empathy has abundant benefits. It is a key ingredient of successful relationships as it facilitates understanding the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others. It creates a sense of well-being. It reduces stress and fosters resilience. Empathy expands the potential for personal and social growth, and for creative thinking and action.

Communications are impacted by the degree of our empathy. When we understand the feelings of another person in a given situation and understand why their actions make sense to them, we are better equipped to communicate our own ideas in a way that may make sense to them. Enhancing communication requires intent listening without preconceived assumptions. Understanding the individual uniqueness of our personal experience facilitates this process.

Some ways to cultivate empathy involve challenging ourselves, exploring feelings in addition to thoughts, and finding ways to ask questions that are conducive to deeper communication and understanding.

Some affirmations I have found valuable in highlighting the potential for becoming more empathetic include:

- I constantly rejoice in the good that comes to others.

- My heart is receptive to new understanding from every source.

- Everyday I enter every experience with the whole of myself.

- My heart re-echoes peace from every heart.

- I acknowledge the infinity of resource.

By Mayte Picco-Kline

This Post Has 2 Comments

Hello! Do you use Twitter? Id like to follow you if that would be okay. Im undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Several of the points associated with this weblog publish are usually advantageous nonetheless had me personally wanting to understand, did they critically imply that? One stage I have got to say is your writing experience are excellent and Ill be returning back again for any brand-new weblog post you come up with, you may probably have a brand-new supporter. I bookmarked your weblog for reference.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe via email.

- Enter your email address: *

Font Resizer

A Decrease font size. A Reset font size. A Increase font size.

Author Spotlight

Recent Posts

- Organized Photos: What’s the fuss all about?

- The Best Way to Cook Greens

- Is It Time To Own Up To Your Hearing Loss?

- Testing Berries and Nuts, Two of the Best Brain Foods

- Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: One Audiologist’s Perspective

Recent Comments

- rama on Four Tips to Practice Good Mental Hygiene During the Coronavirus Outbreak

- rama on The Effect of Avocados on Small, Dense, LDL Cholesterol

- rama on Takeaways from My Webinar on COVID-19

The word “empathy” came to me through diverse situations and sparked my enthusiasm to share a few thoughts on the

Follow Willow Valley Communities

Sponsored by: Willow Valley Communities

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Reflective writing is a process of identifying, questioning, and critically evaluating course-based learning opportunities, integrated with your own observations, experiences, impressions, beliefs, assumptions, or biases, and which describes how this process stimulated new or creative understanding about the content of the course.

A reflective paper describes and explains in an introspective, first person narrative, your reactions and feelings about either a specific element of the class [e.g., a required reading; a film shown in class] or more generally how you experienced learning throughout the course. Reflective writing assignments can be in the form of a single paper, essays, portfolios, journals, diaries, or blogs. In some cases, your professor may include a reflective writing assignment as a way to obtain student feedback that helps improve the course, either in the moment or for when the class is taught again.

How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8.

Benefits of Reflective Writing Assignments

As the term implies, a reflective paper involves looking inward at oneself in contemplating and bringing meaning to the relationship between course content and the acquisition of new knowledge . Educational research [Bolton, 2010; Ryan, 2011; Tsingos-Lucas et al., 2017] demonstrates that assigning reflective writing tasks enhances learning because it challenges students to confront their own assumptions, biases, and belief systems around what is being taught in class and, in so doing, stimulate student’s decisions, actions, attitudes, and understanding about themselves as learners and in relation to having mastery over their learning. Reflection assignments are also an opportunity to write in a first person narrative about elements of the course, such as the required readings, separate from the exegetic and analytical prose of academic research papers.

Reflection writing often serves multiple purposes simultaneously. In no particular order, here are some of reasons why professors assign reflection papers:

- Enhances learning from previous knowledge and experience in order to improve future decision-making and reasoning in practice . Reflective writing in the applied social sciences enhances decision-making skills and academic performance in ways that can inform professional practice. The act of reflective writing creates self-awareness and understanding of others. This is particularly important in clinical and service-oriented professional settings.

- Allows students to make sense of classroom content and overall learning experiences in relation to oneself, others, and the conditions that shaped the content and classroom experiences . Reflective writing places you within the course content in ways that can deepen your understanding of the material. Because reflective thinking can help reveal hidden biases, it can help you critically interrogate moments when you do not like or agree with discussions, readings, or other aspects of the course.

- Increases awareness of one’s cognitive abilities and the evidence for these attributes . Reflective writing can break down personal doubts about yourself as a learner and highlight specific abilities that may have been hidden or suppressed due to prior assumptions about the strength of your academic abilities [e.g., reading comprehension; problem-solving skills]. Reflective writing, therefore, can have a positive affective [i.e., emotional] impact on your sense of self-worth.

- Applying theoretical knowledge and frameworks to real experiences . Reflective writing can help build a bridge of relevancy between theoretical knowledge and the real world. In so doing, this form of writing can lead to a better understanding of underlying theories and their analytical properties applied to professional practice.

- Reveals shortcomings that the reader will identify . Evidence suggests that reflective writing can uncover your own shortcomings as a learner, thereby, creating opportunities to anticipate the responses of your professor may have about the quality of your coursework. This can be particularly productive if the reflective paper is written before final submission of an assignment.

- Helps students identify their tacit [a.k.a., implicit] knowledge and possible gaps in that knowledge . Tacit knowledge refers to ways of knowing rooted in lived experience, insight, and intuition rather than formal, codified, categorical, or explicit knowledge. In so doing, reflective writing can stimulate students to question their beliefs about a research problem or an element of the course content beyond positivist modes of understanding and representation.

- Encourages students to actively monitor their learning processes over a period of time . On-going reflective writing in journals or blogs, for example, can help you maintain or adapt learning strategies in other contexts. The regular, purposeful act of reflection can facilitate continuous deep thinking about the course content as it evolves and changes throughout the term. This, in turn, can increase your overall confidence as a learner.

- Relates a student’s personal experience to a wider perspective . Reflection papers can help you see the big picture associated with the content of a course by forcing you to think about the connections between scholarly content and your lived experiences outside of school. It can provide a macro-level understanding of one’s own experiences in relation to the specifics of what is being taught.

- If reflective writing is shared, students can exchange stories about their learning experiences, thereby, creating an opportunity to reevaluate their original assumptions or perspectives . In most cases, reflective writing is only viewed by your professor in order to ensure candid feedback from students. However, occasionally, reflective writing is shared and openly discussed in class. During these discussions, new or different perspectives and alternative approaches to solving problems can be generated that would otherwise be hidden. Sharing student's reflections can also reveal collective patterns of thought and emotions about a particular element of the course.

Bolton, Gillie. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development . London: Sage, 2010; Chang, Bo. "Reflection in Learning." Online Learning 23 (2019), 95-110; Cavilla, Derek. "The Effects of Student Reflection on Academic Performance and Motivation." Sage Open 7 (July-September 2017): 1–13; Culbert, Patrick. “Better Teaching? You Can Write On It “ Liberal Education (February 2022); McCabe, Gavin and Tobias Thejll-Madsen. The Reflection Toolkit . University of Edinburgh; The Purpose of Reflection . Introductory Composition at Purdue University; Practice-based and Reflective Learning . Study Advice Study Guides, University of Reading; Ryan, Mary. "Improving Reflective Writing in Higher Education: A Social Semiotic Perspective." Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2011): 99-111; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8; What Benefits Might Reflective Writing Have for My Students? Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse; Rykkje, Linda. "The Tacit Care Knowledge in Reflective Writing: A Practical Wisdom." International Practice Development Journal 7 (September 2017): Article 5; Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning . Center for Writing, University of Minnesota.

How to Approach Writing a Reflection Paper

Thinking About Reflective Thinking

Educational theorists have developed numerous models of reflective thinking that your professor may use to frame a reflective writing assignment. These models can help you systematically interpret your learning experiences, thereby ensuring that you ask the right questions and have a clear understanding of what should be covered. A model can also represent the overall structure of a reflective paper. Each model establishes a different approach to reflection and will require you to think about your writing differently. If you are unclear how to fit your writing within a particular reflective model, seek clarification from your professor. There are generally two types of reflective writing assignments, each approached in slightly different ways.

1. Reflective Thinking about Course Readings

This type of reflective writing focuses on thoughtfully thinking about the course readings that underpin how most students acquire new knowledge and understanding about the subject of a course. Reflecting on course readings is often assigned in freshmen-level, interdisciplinary courses where the required readings examine topics viewed from multiple perspectives and, as such, provide different ways of analyzing a topic, issue, event, or phenomenon. The purpose of reflective thinking about course readings in the social and behavioral sciences is to elicit your opinions, beliefs, and feelings about the research and its significance. This type of writing can provide an opportunity to break down key assumptions you may have and, in so doing, reveal potential biases in how you interpret the scholarship.

If you are assigned to reflect on course readings, consider the following methods of analysis as prompts that can help you get started :

- Examine carefully the main introductory elements of the reading, including the purpose of the study, the theoretical framework being used to test assumptions, and the research questions being addressed. Think about what ideas stood out to you. Why did they? Were these ideas new to you or familiar in some way based on your own lived experiences or prior knowledge?

- Develop your ideas around the readings by asking yourself, what do I know about this topic? Where does my existing knowledge about this topic come from? What are the observations or experiences in my life that influence my understanding of the topic? Do I agree or disagree with the main arguments, recommended course of actions, or conclusions made by the author(s)? Why do I feel this way and what is the basis of these feelings?

- Make connections between the text and your own beliefs, opinions, or feelings by considering questions like, how do the readings reinforce my existing ideas or assumptions? How the readings challenge these ideas or assumptions? How does this text help me to better understand this topic or research in ways that motivate me to learn more about this area of study?

2. Reflective Thinking about Course Experiences

This type of reflective writing asks you to critically reflect on locating yourself at the conceptual intersection of theory and practice. The purpose of experiential reflection is to evaluate theories or disciplinary-based analytical models based on your introspective assessment of the relationship between hypothetical thinking and practical reality; it offers a way to consider how your own knowledge and skills fit within professional practice. This type of writing also provides an opportunity to evaluate your decisions and actions, as well as how you managed your subsequent successes and failures, within a specific theoretical framework. As a result, abstract concepts can crystallize and become more relevant to you when considered within your own experiences. This can help you formulate plans for self-improvement as you learn.

If you are assigned to reflect on your experiences, consider the following questions as prompts to help you get started :

- Contextualize your reflection in relation to the overarching purpose of the course by asking yourself, what did you hope to learn from this course? What were the learning objectives for the course and how did I fit within each of them? How did these goals relate to the main themes or concepts of the course?

- Analyze how you experienced the course by asking yourself, what did I learn from this experience? What did I learn about myself? About working in this area of research and study? About how the course relates to my place in society? What assumptions about the course were supported or refuted?

- Think introspectively about the ways you experienced learning during the course by asking yourself, did your learning experiences align with the goals or concepts of the course? Why or why do you not feel this way? What was successful and why do you believe this? What would you do differently and why is this important? How will you prepare for a future experience in this area of study?

NOTE: If you are assigned to write a journal or other type of on-going reflection exercise, a helpful approach is to reflect on your reflections by re-reading what you have already written. In other words, review your previous entries as a way to contextualize your feelings, opinions, or beliefs regarding your overall learning experiences. Over time, this can also help reveal hidden patterns or themes related to how you processed your learning experiences. Consider concluding your reflective journal with a summary of how you felt about your learning experiences at critical junctures throughout the course, then use these to write about how you grew as a student learner and how the act of reflecting helped you gain new understanding about the subject of the course and its content.

ANOTHER NOTE: Regardless of whether you write a reflection paper or a journal, do not focus your writing on the past. The act of reflection is intended to think introspectively about previous learning experiences. However, reflective thinking should document the ways in which you progressed in obtaining new insights and understandings about your growth as a learner that can be carried forward in subsequent coursework or in future professional practice. Your writing should reflect a furtherance of increasing personal autonomy and confidence gained from understanding more about yourself as a learner.

Structure and Writing Style

There are no strict academic rules for writing a reflective paper. Reflective writing may be assigned in any class taught in the social and behavioral sciences and, therefore, requirements for the assignment can vary depending on disciplinary-based models of inquiry and learning. The organization of content can also depend on what your professor wants you to write about or based on the type of reflective model used to frame the writing assignment. Despite these possible variations, below is a basic approach to organizing and writing a good reflective paper, followed by a list of problems to avoid.

Pre-flection

In most cases, it's helpful to begin by thinking about your learning experiences and outline what you want to focus on before you begin to write the paper. This can help you organize your thoughts around what was most important to you and what experiences [good or bad] had the most impact on your learning. As described by the University of Waterloo Writing and Communication Centre, preparing to write a reflective paper involves a process of self-analysis that can help organize your thoughts around significant moments of in-class knowledge discovery.

- Using a thesis statement as a guide, note what experiences or course content stood out to you , then place these within the context of your observations, reactions, feelings, and opinions. This will help you develop a rough outline of key moments during the course that reflect your growth as a learner. To identify these moments, pose these questions to yourself: What happened? What was my reaction? What were my expectations and how were they different from what transpired? What did I learn?

- Critically think about your learning experiences and the course content . This will help you develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding about why these moments were significant or relevant to you. Use the ideas you formulated during the first stage of reflecting to help you think through these moments from both an academic and personal perspective. From an academic perspective, contemplate how the experience enhanced your understanding of a concept, theory, or skill. Ask yourself, did the experience confirm my previous understanding or challenge it in some way. As a result, did this highlight strengths or gaps in your current knowledge? From a personal perspective, think introspectively about why these experiences mattered, if previous expectations or assumptions were confirmed or refuted, and if this surprised, confused, or unnerved you in some way.

- Analyze how these experiences and your reactions to them will shape your future thinking and behavior . Reflection implies looking back, but the most important act of reflective writing is considering how beliefs, assumptions, opinions, and feelings were transformed in ways that better prepare you as a learner in the future. Note how this reflective analysis can lead to actions you will take as a result of your experiences, what you will do differently, and how you will apply what you learned in other courses or in professional practice.

Basic Structure and Writing Style

Reflective Background and Context

The first part of your reflection paper should briefly provide background and context in relation to the content or experiences that stood out to you. Highlight the settings, summarize the key readings, or narrate the experiences in relation to the course objectives. Provide background that sets the stage for your reflection. You do not need to go into great detail, but you should provide enough information for the reader to understand what sources of learning you are writing about [e.g., course readings, field experience, guest lecture, class discussions] and why they were important. This section should end with an explanatory thesis statement that expresses the central ideas of your paper and what you want the readers to know, believe, or understand after they finish reading your paper.

Reflective Interpretation

Drawing from your reflective analysis, this is where you can be personal, critical, and creative in expressing how you felt about the course content and learning experiences and how they influenced or altered your feelings, beliefs, assumptions, or biases about the subject of the course. This section is also where you explore the meaning of these experiences in the context of the course and how you gained an awareness of the connections between these moments and your own prior knowledge.