- University Writing Center

- The Writing Mine

How To: Genre Analysis

Although most of us think of music styles when we hear the word “genre,” the word simply means category of items that share the same characteristics, usually in the arts. In this context, however, we are talking about types of texts. Texts can be written, visual, or oral.

For instance, a written genre would be blogs, such as this one, books, or news articles. A visual genre would be cartoons, videos, or posters. An oral genre would be podcasts, speeches, or songs. Each of these genres communicates differently because each genre has different rules.

A genre analysis is an essay where you dissect texts to understand how they are working to communicate their message. This will help you understand that each genre has different requirements and limitations that we, as writers, must be aware of when using that genre to communicate.

Sections of a genre analysis

Like all other essays, a genre analysis has an introduction, body, and conclusion.

In your introduction, you introduce the topic and the texts you’ll be analyzing.

In your body, you do your analysis. This should be your longest section.

In your conclusion, you do a short summary of everything you talked about and include any closing thoughts, such as whether you think the text accomplished its purpose and why.

Content

All professors ask for different things, so make sure to look at their instructions. These are some areas that will help you analyze your text and that you might want to touch base on in your essay (most professors ask for them):

1. Purpose of the text

What did the creator of the text want to achieve with it? Why was the text created? Did something prompt the creator to make the text?

Sometimes, the texts themselves answer these questions. Other times, we get that through clues like the language they use, the platforms the creator chose to spread their text, and so on. Make sure to include in your essay what features of the text led you to your answer.

If we take this blog post as an example, we can say that its purpose is to inform students like you about what a genre analysis is and the content it requires. You probably figured this out through the language I’m using and the information I’m choosing to include.

2. Intended audience

Who is the creator of the text trying to reach? How did you figure that out?

The audience can be as specific as a small group of people interested in a very niche topic or as broad as people curious about a common topic.

With this blog, for example, I’m trying to reach students, particularly UTEP students who have this assignment and are trying to understand it. My causal and informative tone, as well as the fact that the blog is posted on UTEP’s Writing Center blog, probably gave this away.

3. Structure

How is the text organized? How does that help the creator achieve the text’s purpose?

You need to know the information at the top of this blog post to understand what comes after, so this blog post is organized in order of complexity.

4. Genre conventions

Is the text following the usual characteristics of the genre? How is this helping or impeding the text to achieve its purpose?

Like most blogs, this one is using simple language, short paragraphs, and illustrations. My use of all these elements is helping me be clear and specific so you can understand your assignment.

5. Connection

Do the ideas in the text come from somewhere else? Can the reader or consumer interact with the text? Is the text inviting that interaction?

Most of the time, when the ideas come from another source, the text will make that clear by mentioning the text. In terms of interaction possible with the text, think about if it would be easy for you to say something back to the text.

For instance, if you wanted to ask a question about this blog post, you could type it in our comment section. I might not explicitly say that many ideas in this blog come from the guidelines your professor gives you for this assignment, but you probably gathered that because I mention that these areas are things most professors are looking for.

Hopefully, this information helps you tackle your assignment with a clearer idea of what your professor is looking for. Make sure to address any other areas the professor is asking you to.

If you still have questions or want to make sure you are on the right path, come visit us at the University Writing Center.

Connect With Us

The University of Texas at El Paso University Writing Center Library 227 500 W University El Paso, Texas 79902

E: [email protected] P: (915) 747-5112

14.3 Methods for Studying Genres

The previous section outlined some key terms and definitions for the study of writing. This section builds on that by providing an overview of research tools that can be used to better understand writing-in-context. Some of these tools–like an interview–may seem more familiar to you than others (such as genre analysis). At the same time, an activity you probably engage in every day–observation–achieves importance when done in the context of research and analysis.

There is no one right way to “do” writing research. Choosing the right tools depends on what it is you hope to learn. As you study a genre, whether it is a resume, a report, a procedural, or a complaint letter, think creatively about which of the following methods might help you learn more about it.

Genre/Textual Analysis

If genres are the key object of study for writing researchers, then genre analysis is the key tool for studying those objects–for unlocking their meaning. While it is true that we can learn a great deal about genres by observing people using them and even asking their users about them (which I detail in the next section), there is often important meaning that goes unnoticed by the producers and users of a genre. This meaning is what writing researchers try to access by studying the genres themselves. To put it another way, genres often have embedded in them a kind of code or shorthand that can reveal important information about the context in which they are used. As someone learning to write in that context, such information can help you to advance in your writing skills more quickly.

So how do writing researchers do this analysis? In short, genre analysis involves picking apart and noting the various features of a particular text in order to figure out what they mean (i.e., why they are significant) for the people who use that genre. In that sense, writing researchers act as detectives, revealing clues in order to then piece them all together and generate a cohesive story about what those clues mean.

It probably will not surprise you to know that, once again, curiosity plays an important role in conducting genre analysis. While it can be tempting when looking at a text to think there is not much to say about it (this is especially true when you take something as everyday as your grocery list or the menu at a coffee shop), when we begin to ask questions, the complexity of a text (and the genre it represents) is pretty quickly revealed.

A precursor to genre analysis is what researchers call “document collection.” While it is true that the more samples of a genre you find the more reliable and extensive your analysis can and will be, analyzing even one text can reveal a great deal. So, if genre analysis sounds kind of overwhelming or challenging, start by looking at a single sample text rather than many.

The following questions can get you thinking about (and taking notes on) how you would describe a sample text, by focusing on its content , its form , and its presentation :

- Who and what is referenced in the document?

- What information is included in the document? How much?

- What is the rhetorical purpose of the document?

- How is information organized, from beginning to end? In other words, what appears where?

- What kinds of sentences are used (questions, statements, commands, etc.)?

- What do you notice about the kind of language that is used?

- How would you describe the tone of the writing?

- How does the text use rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, logos)?

- Are section headings used in the document?

- Does the document include text only, or text and images? What is the layout like?

- What font size and style is used?

- How would you describe the “look” of the document?

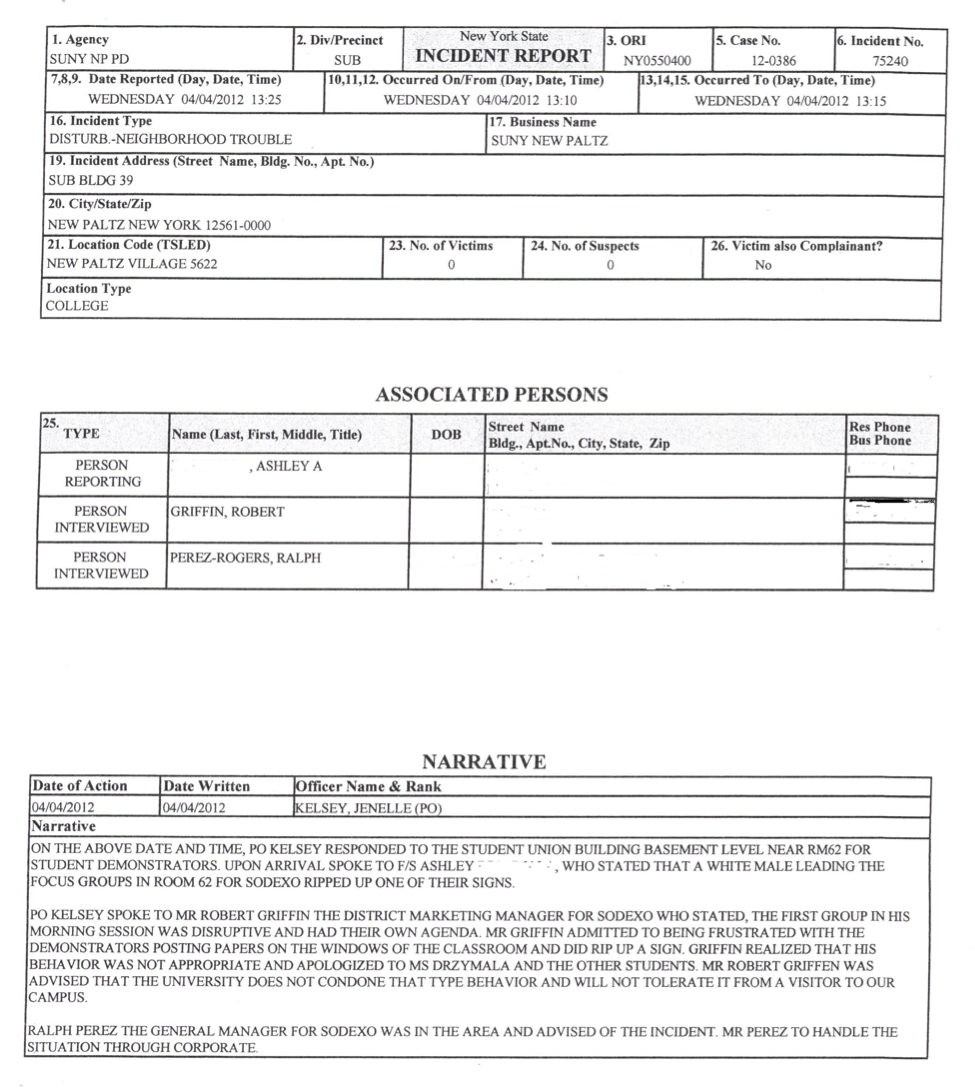

Figure 1 provides a sample police incident report and is followed by some notes you would be likely to make based on the suggested questions above. Alternate formats: Word version of incident report ; PDF version of incident report .

Case Study, Part One: Notes on the Incident Report

- When the incident occurred

- Where the incident occurred

- Who was involved

- How many were involved

- Who was interviewed

- What happened (narrative)

- Which precinct is responsible for investigating

- Type of incident, people involved (victims/suspects), and location

- Filing information (case and incident numbers)

- Three distinct sections

- Logistical info appears first, “associated persons” appears second, narrative of the event appears third

- Narrative uses simple declarative statements, typically with people occupying the place of subject

- Use of verbs is active but primarily neutral, with a focus on communication that transpired (“responded,” “spoke,” “admitted,” “realized,” “advised”), with two instances of the use of passive voice (“was advised”)

- Narrative is described with a neutral tone and feels formal

- Focus of narrative is on actions taken that

- Narrative is described in chronological order, beginning with officer responding to incident, moving through the incident, and providing information on follow-up

- Items used for referential or filing reasons are numbered

- Information is organized into boxes and tables

- Each section is clearly labeled

- Abbreviations are used throughout

- Report is typed

After you have answered these questions, it is time to start looking for patterns and connections that will help you draw conclusions about what these features mean. Doing so involves a kind of creative thinking that is best done by someone who has been involved in studying or practicing the profession under investigation. Generally speaking, it is best to give some consideration to how the features of a particular genre might be connected to goals, objectives, and values of a particular position, organization, and/or context, since it is that context that produced the need for that genre in the first place.

Case Study, Part Two: Analysis of the Incident Report

The content, form, and presentation of the police incident report form work together to present a verifiable , objective account. Used internally, the design of the form helps to create uniformity by directing the officer to include the information that is likely to prove most salient for police purposes and for easy retrieval should future incidents occur. This streamlined approach to documentation keeps the focus on material and factual evidence, which clearly relates to the fact that this is a document that may be used in a legal context.

Generally speaking, a document that pays little attention to design, but has a great deal of detailed content, might derive from a situation where people place heavy emphasis on the development of ideas but don’t necessarily need to act on those ideas; on the other hand, if a document makes heavy use of section headings in order to direct the reader more carefully, it might suggest a need for greater efficiency of time and/or a number of readers with different background knowledge. Of course, there are genres that will do both: include a great number of complex ideas, neatly organized into easily accessible sections. No matter what you find, there is an interpretation to be discovered and explained with evidence from the text itself. The connecting of evidence to interpretation/conclusion is genre analysis.

[ Genre Analysis Essay video without captions ; Genre Analysis Essay video with captions ]

Interviewing is something that happens informally all the time when we query colleagues or supervisors about how to write in a new genre. But a formal interview is a particular kind of research method that takes a bit of practice and can be quite difficult if you have never done it before. With a question we ask of a colleague, we usually have something very specific we want to know, but as a research method, interviews are usually used in order to answer a research question –and it is that distinction that you need to keep in mind.

A good research question, as you may have already learned in other college-level classes, does not have an easy answer. In fact, it usually does not have a single answer either; instead, it is a question that requires interpretation and that might be answered differently depending on who you ask. That said, it is answerable, meaning that given the right collection of evidence, you would be able to craft a response of some kind. In writing research, the interview is one way to collect just such evidence, since talking to someone about how, when, and why they use writing in their profession can provide all kinds of insight that you might miss if you were to analyze a text all by itself. Typically, these kinds of questions (of the “how,” “when,” and “why” variety) help writing researchers to understand the particular importance of writing to a specific profession, industry, organization, or even economy.

It is not uncommon for people in workplace settings not to realize just how much writing is a part of their everyday work practices. In the course of being asked questions, though, they often reveal the way that writing helps them accomplish their jobs successfully and make sure the company or organization runs effectively and achieves its goals. This is true whether you are interviewing a doctor, a firefighter, a restaurant manager, an electrician, a politician, a general contractor, or a computer specialist.

Here are some general advice and reminders for getting organized to conduct an interview:

- Practice good manners when scheduling the interview. This is an opportunity to practice being professional in your communication: everything you know about audience analysis should come into play as you request someone’s time and input.

- Be sure to practice your interview questions ahead of time. Questions that seem straightforward to you might not be clear to someone else; alternatively, they might clearly call for a different kind of answer than what you anticipated. The best way to know is to practice them on someone who is not your intended interviewee. Then, revise accordingly.

- Request permission to record the interview. You will be glad to have a record to return to if your interviewee says yes. Whether or not you record the interview, though, be sure to take notes in the interview (this is something you can and should practice in your practice interview as well). Recording devices can fail; writing during the interview can also help you to focus on what your interviewee is saying and to think of new, sometimes clarifying questions, as the interview proceeds.

Observation

Another powerful research tool is simply observing where the writing of a particular profession takes place. The values of a company or organization, the expectations they hold for their employees and various working conditions are often on display if you only look for them. For example:

- Is the workplace open to the public, or does it require secure entry?

- Do people work in offices or cubicles? Or maybe there is no individual work space at all?

- How many meeting rooms are there? How big are they?

- Are people milling around, or are they mostly on computers?

- How is the workplace decorated?

- What is the dress code?

The answers to these questions can lead to new insight regarding how genres are used and produced and help develop new questions for you to consider. Furthermore, observation also helps with imagining texts in use, which is so crucial to an effective analysis of your audience.

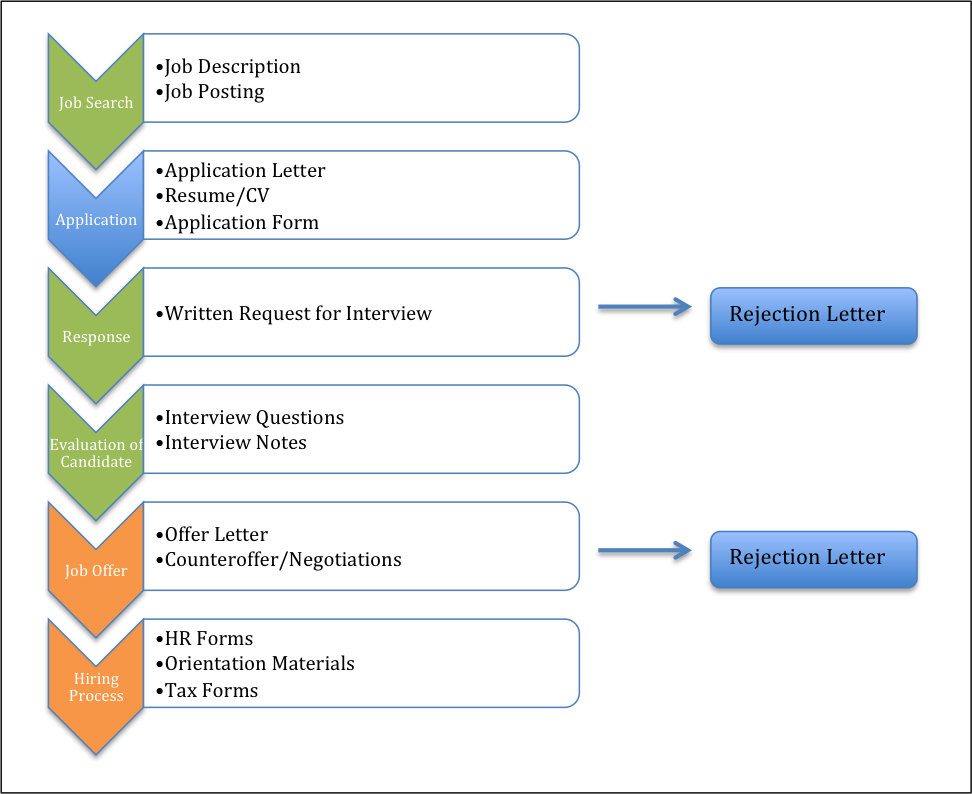

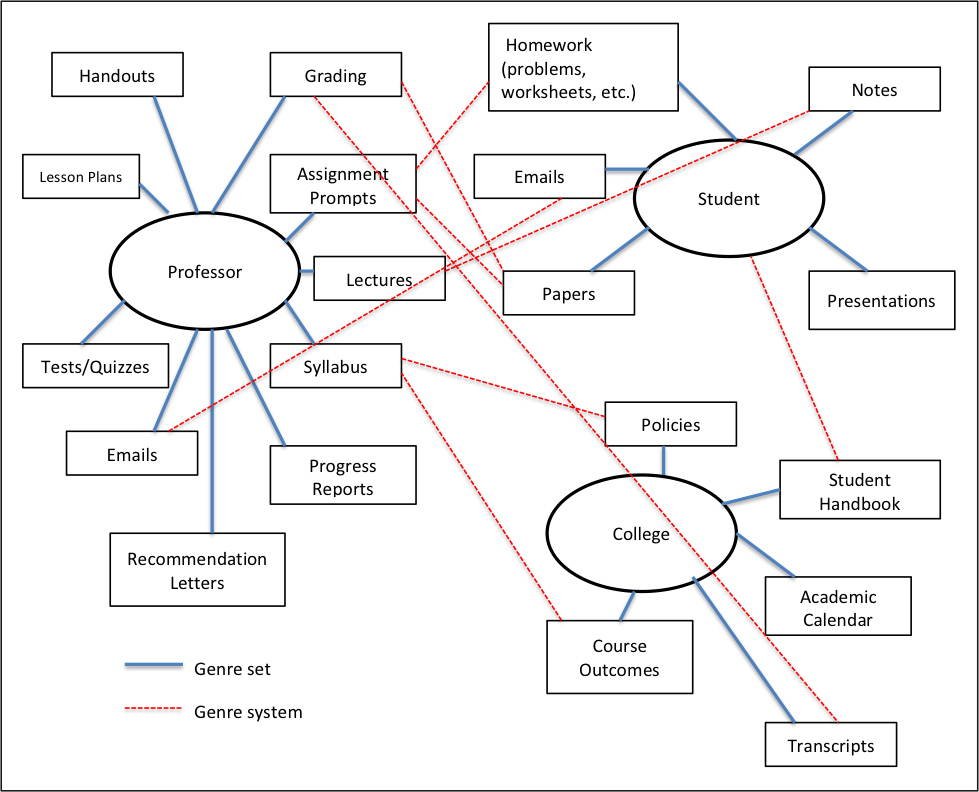

Genre Ecology Maps

A Genre Ecology Map, or GEM, is a visual representation of genres in action, interacting with one another. Let’s consider an earlier example: the job description. We could explain, using words, that the job description leads to job applications, which (often) lead to interviews and background checks, the hiring of an individual and all the associated paperwork, as well as training materials. But if we wanted to represent that visually, it would look something like Figure 2. Alternate formats: Word version of Job Application GEM ; PDF version of Job Application GEM .

All of a sudden, with a visual illustration, we have a slightly different understanding of the complexity involved in the production and circulation of different kinds of writing. Figure 3 provides another example, one that captures the intersection of different writers, positions, and stakeholders (put another way: the intersection of different genre sets in the college classroom). Alternate formats: Word version of Classroom GEM ; PDF version of Classroom GEM .

Particularly if you are a visual learner, maps like those above can help you to “see” genres in a way you might not otherwise and to reinforce what I have noted in sections above about how writing is not static but actually performs “actions” in various workplace settings.

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION

This chapter was written by Allison Gross, Portland Community College, and is licensed CC-BY 4.0 .

Technical Writing Copyright © 2017 by Allison Gross, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Corpus-based Genre Analysis

- First Online: 13 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Xiaofei Lu 3 ,

- J. Elliott Casal 3 , 4 &

- Yingying Liu 3

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

640 Accesses

Corpus-based genre analysis is an emerging approach to the analysis of academic writing practices that considers the recurring linguistic patterns of academic genres in terms of the rhetorical goals that writers employ them to realize. Ideally, it entails manual rhetorical move-step annotation of each text in a corpus and identification of recurring linguistic features (e.g., lexical, phraseological, syntactic), which are then mapped to each other.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Genre identification based on sfl principles: the representation of text types and genres in english language teaching material.

Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Academic Discourse

Automatic genre identification: a survey

Charles, M. (2007). Reconciling top-down and bottom-up approaches to graduate writing: Using a corpus to teach rhetorical functions. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 6 , 289–302.

Article Google Scholar

Cortes, V. (2013). The purpose of this study is to: Connecting lexical bundles and moves in research article introductions. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12 , 33–43.

Durrant, P., & Mathews-Aydınlı, J. (2011). A function-first approach to identifying formulaic language in academic writing. English for Specific Purposes, 30 , 58–72.

Ellis, N. C., & Cadierno, T. (2009). Constructing a second language. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7 , 111–139.

Flowerdew, L. (2005). An integration of corpus-based and genre-based approaches to text analysis in EAP/ESP: Countering criticisms against corpus-based methodologies. English for Specific Purposes, 24 , 321–332.

Le, T. N. P., & Harrington, M. (2015). Phraseology used to comment on results in the Discussion section of applied linguistics quantitative research articles. English for Specific Purposes, 39 , 45–61.

Lu, X., Casal, J. E., & Liu, Y. (2020). The rhetorical functions of syntactically complex sentences in social science research article introductions. Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 44 , 1–16 .

Moreno, A. I., & Swales, J. M. (2018). Strengthening move analysis methodology towards bridging the function-form gap. English for Specific Purposes, 50 , 40–63.

Omidian, T., Shahriari, H., & Siyanova-Chanturia, A. (2018). A cross-disciplinary investigation of multi-word expressions in the moves of research article abstracts. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 36 , 1–14.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings . Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Tardy, C. M. (2009). Building genre knowledge . Parlor Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Applied Linguistics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA

Xiaofei Lu, J. Elliott Casal & Yingying Liu

Department of Cognitive Science, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

J. Elliott Casal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xiaofei Lu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European Knowledge Development Institute, Ankara, Türkiye

Hassan Mohebbi

Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT), Dubai Men’s College, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Christine Coombe

The Research Questions

What level of intercoder reliability can be achieved in rhetorical move-step annotation of a corpus of academic writing and what methodological practices can help maximize such intercoder reliability?

What language features distinguish or correlate strongly with different rhetorical moves and steps?

How do expert writers vary their use of items and structures at different linguistic levels (e.g., lexical, phraseological, and syntactic) to achieve their rhetorical goals?

Are academic writing learners adequately aware of the importance of the mappings between rhetorical functions and language forms?

Do academic writing teachers pay adequate attention to the mappings between rhetorical functions and language forms in pedagogy?

How might corpora of academic writing annotated for rhetorical moves and steps and their associated language features be used in genre-based writing pedagogy to improve L2 learners’ genre competence?

How will learning outcomes be affected by presenting rhetorical and linguistic structures in isolation or in tandem in academic writing pedagogy?

Do raters pay adequate attention to the mappings between rhetorical functions and language forms?

How can we reliably assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of the mappings between rhetorical functions and language forms in learner writing?

What is the quantitative relationship of form-function mappings to human ratings of writing quality?

Suggested Resources

Biber, D., Connor, U., & Upton, T. A. (2007). Discourse on the move: Using corpus analysis to describe discourse structure . Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins .

Based on the introductory chapter, the term “discourse analysis” in this book is used in the broad sense of analyzing discourse, as the authors divide “discourse analysis” into three branches: study of structural organization of texts, study of language use, and study of social practices and ideological assumptions. This work focuses on the first two major lines of research with the aim of merging the top-down perspective adopted in the study of structural organization (e.g., genre analysis) and the bottom-up perspective in the study of language use (e.g., corpus analysis). After the introductory chapter, the main body of this book is divided into two main parts. The first part is dedicated to the top-down approach (Chaps. 2–5) and centers on Swalesian move analysis, while the second part is dedicated to the bottom-up approach (Chaps. 6–8) and emphasizes Multi-Dimensional Analysis of lexico-grammatical features, which is based on the TextTiling procedure. Chapter 9 illustrates the differences between the two approaches by comparing their respective descriptions of biology research articles.

Tardy, C. M. (2009) . Building genre knowledge . West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press .

This work traces the development of genre knowledge of four multilingual graduate students through their learning and practices in an ESL writing class, disciplinary subject courses and disciplinary research. The author presents a four-dimensional model of genre knowledge (formal, rhetorical, process, and subject-matter), which develops toward the integration of initially isolated components. The first chapter lays the groundwork by discussing foundational concepts used in the follow-up analysis. Chapter 2 introduces the research context and participants. Chapters 3 and 4 examine the students’ genre knowledge development through their engagement in an ESL writing class, focusing on the class assignments of writing job application cover letters and conducting genre analysis. Chapter 5 analyzes the four participants’ exposure, production and development of their knowledge of the multimodal presentation slides genre across different learning contexts. Chapter 6 shifts to disciplinary content courses with a focus on the genres of lab reports and reviews. Chapter 7 traces one participant’s master’s thesis writing process during which his advisor’s feedback on the drafts plays a central role in the development of his knowledge of the master’s thesis genre. Chapter 8 analyzes the sole doctoral student among the four focal participants and considers his learning process in writing conference-related research papers. Chapter 9 examines the development of genre knowledge building and offers pedagogical suggestions. By reading this book, academic writing instructors and researchers can gain insights into how individual students in different disciplines and in various learning contexts develop academic literacy and genre knowledge through engaging in general English language classes, disciplinary content courses, as well as other tasks and interactions.

Charles, M., Pecorari, D., & Hunston, S. (Eds.) (2010). Academic writing: At the interface of corpus and discourse . London: Continuum .

This edited collection represents an effort to explore the interface between corpus linguistics and discourse analysis. The two approaches are not regarded as opposing, as some scholars have argued, but rather serve as two ends of a continuum. This idea is outlined in the editors’ preface. The main body of this book includes 14 studies of academic writing organized in three foci: genre and disciplinary discourse, interpersonal discourse, and learner discourse. Each study represents an author’s perspective of academic writing research, situated on either end of the corpus-discourse analysis continuum. Collectively, these studies cover a wide diversity of genres, disciplines, methods and linguistic features. In addition to the preface and main chapters, the afterword written by John Swales is also worth reading. He begins with a brief discussion of the preface and afterword genres themselves, and then presents his own reflections on some of the studies included in this volume. Swales concludes with a noteworthy reflection on the extent to which researchers can incorporate aspects of the other side of the continuum, stating that “we will often see that it is typically somewhat easier for discourse analysts to incorporate corpus linguistics than for corpus linguists to expand their textual horizons to encompass the discoursal plane”.

Swales, J. M., & Feak, C. B. (2012). Academic writing for graduate students (3rd ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press .

Now in its third edition, this popular EAP textbook targets both first and second language English graduate student writers. Considering the diversity of academic genres that target readers face in academia, the authors construct their course book with the aim of raising genre awareness of graduate student writers by guiding them through a series of analytical and writing tasks. The tasks draw on corpus and genre-based approaches to writing analysis, integrating them for pedagogical purposes. The first of the book’s eight chapters presents basic concepts of genre theory that are essential for the following material and for considering writing as a series of choices in relation to community expectations. The second and third chapters outline two broad structural patterns of academic writing: the general-to-specific pattern and the problem–solution pattern. Chapters 4–6 deal with three largely pedagogical genre families, including data interpretation and discussion, summaries, and critiques. The last two chapters tie these skills and writing purposes together in an overview of research article writing for publication. The design and arrangement of the tasks in each chapter align well with the authors’ strong belief in the “rhetorical consciousness raising” cycle (i.e., analysis - awareness - acquisition - achievement ), with each chapter entailing comprehension and production tasks, conceptual genre discussion as well as language preparation for particular genres. This book can be used as a textbook in a general EAP program or as a reference book for apprentice academic writers in any discipline.

Whitt, R. J. (Ed.) (2018). Diachronic corpora, genre, and language change . Amsterdam/Philadelphia : John Benjamins .

With the collective position that genre both affects language change and constitutes a locus of language change, the studies in this volume examine the interplay between language change and genre using diachronic corpora, showcasing the effectiveness of corpus-based methodologies as well as highlighting the issues and challenges in this line of research. The volume consists of three parts. Part I includes three chapters that focus on methods, resources and tools in diachronic corpus linguistics. Niehaus and Elspass describe the composition of the Nineteenth-Century German Corpus and illustrate the benefits of integrating texts of diverse registers and genres for studying language variation and change. Jurish discusses how the open-source program DiaCollo can be used for diachronic, genre-sensitive collocation profiling. Atwell introduces a range of classical and modern Arabic corpus resources developed by researchers at the University of Leeds. Part II include two chapters that examine language change in specific language usage domains. Taavitsainen traces changes in generic features of English medical writing from 1375 to 1800 using diachronic medical corpora, while Gray and Biber document the patterns of linguistic change in academic writing and discuss the quantitative and functional nature of such changes. The eight chapters in Part III employ multi-genre diachronic corpora to explore how genre affects the analyses and findings of language change and variation at varied linguistic levels and in diverse languages. Overall, this volume provides an excellent state-of-the-art overview of corpus and genre-based studies of language variation and change.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Lu, X., Casal, J.E., Liu, Y. (2021). Corpus-based Genre Analysis. In: Mohebbi, H., Coombe, C. (eds) Research Questions in Language Education and Applied Linguistics. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79143-8_140

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79143-8_140

Published : 13 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-79142-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-79143-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Campus Library Info.

- ARC Homepage

- Library Resources

- Articles & Databases

- Books & Ebooks

Baker College Research Guides

- Research Guides

- General Education

COM 1010: Composition and Critical Thinking I

- Understanding Genre and the Rhetorical Situation

- The Writing Process

- What is Literacy?

- What is an Autobiography?

- Essay Organization Help

- Tutoring Help

- Understanding Summary

- Shifting Your Language/Diction

- What is a Response?

- What is Research?

- Locating Sources

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- What is a Peer Review?

- Understanding Images

- Understanding PowerPoint and Presentations

- What is Analysis?

- Genre Analysis

- Shifting Genres

- What is Reflection?

Understanding What is Meant by the Word "Genre"

What do we mean by genre? This means a type of writing, i.e., an essay, a poem, a recipe, an email, a tweet. These are all different types (or categories) of writing, and each one has its own format, type of words, tone, and so on. Analyzing a type of writing (or genre) is considered a genre analysis project. A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it.

Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique. These conventions include the following components:

- Tone: tone of voice, i.e. serious, humorous, scholarly, informal.

- Diction : word usage - formal or informal, i.e. “disoriented” (formal) versus “spaced out” (informal or colloquial).

- Content : what is being discussed/demonstrated in the piece? What information is included or needs to be included?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Short-hand? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Can pictures / should pictures be included? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : where does the genre appear? Where is it created? i.e. can be it be online (digital) or does it need to be in print (computer paper, magazine, etc)? Where does this genre occur? i.e. flyers (mostly) occur in the hallways of our school, and letters of recommendation (mostly) occur in professors’ offices.

- Genre creates an expectation in the minds of its audience and may fail or succeed depending on if that expectation is met or not.

- Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

- The goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

- Basically, each genre has a specific task or a specific goal that it is created to attain.

- Understanding Genre

- Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

To understand genre, one has to first understand the rhetorical situation of the communication.

Below are some additional resources to assist you in this process:

- Reading and Writing for College

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: What is Literacy? >>

- Last Updated: Oct 22, 2024 8:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.baker.edu/com1010

- Search this Guide Search

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This vidcast explains two tools that writers can use as they revise their documents: genre analysis and reverse outlining. Genre analysis involves looking at model texts to gain an understanding of how a particular document might be composed.

A genre analysis is an essay where you dissect texts to understand how they are working to communicate their message. This will help you understand that each genre has different requirements and limitations that we, as writers, must be aware of when using that genre to communicate.

This review explores the application of genre analysis to thesis abstracts and presents case studies showcasing its implementation across various disciplines.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis, nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Genre analysis is a way to examine a model text to determine how that type of text is written—what features are necessary in order for the text to be considered part of that genre? You might think of it as a form of reverse engineering.

If genres are the key object of study for writing researchers, then genre analysis is the key tool for studying those objects–for unlocking their meaning.

SOME STEPS FOR. GENRE ANALYIS. GLOBAL VS. LOCAL APPROACH. Global Key Concerns: How do big-picture decisions create a holistic argument? Local Key Concerns: How do these sentence-level decisions affect how the argument is expressed? At the Paragraph Level: Saying -- What is the author’s overall message?

Genre analysis has emerged as a crucial tool in deciphering and delineating the linguistic features of scholarly research articles. This article presents a comprehensive review of genre analysis in relation to academic writings, with a specific focus on research articles.

Corpus-based genre analysis is an emerging approach to the analysis of academic writing practices that considers the recurring linguistic patterns of academic genres in terms of the rhetorical goals that writers employ them to realize.

A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it. Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique.