- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Universal Design

Universal Design: The Latest Architecture and News

Handrails and accessibility 101: ensuring safe usage in architectural projects.

Architectural design is a discipline that spans a wide range of scales, from macro scales involving the design of master plans or large urban complexes to micro scales, where it focuses on specific elements such as fixtures and fittings. Regardless of scale, careful attention to the design of each component of the built environment plays a critical role in how people experience architecture.

At the architectural micro-scale, railings and handrails play specific roles but are often confusing. While railings are designed to enclose spaces and prevent falls, handrails function as support elements, offering orientation and stability to avoid accidents and injuries. It is in the latter aspect that a stronger connection to accessibility becomes evident. For this reason, it is essential to have handrails, wall railings, and assist railings that meet ADA standards , such as those developed by Hollaender Manufacturing Co. These elements adapt to various design conditions, facilitating the movement of individuals who may encounter barriers in the physical environment.

- Read more »

Healing Architecture for Care and Recovery: Iconic Design with Colorful Concepts

The influence of design on our physical and mental health has been largely explored in various contexts, ranging from spatial configuration to furniture. The topic has gained notoriety due to the growing awareness of human well-being, especially in recent times. An example of this bond between design and health is the emergence of concepts such as Neuroarchitecture , which seeks to understand the built environment’s potential in our brain. Another case that illustrates this approach, this time in furniture design, is the Paimio Sanatorium , where Alvar Aalto designed the tuberculosis sanatorium and all its furnishings. The chair created for the patient’s lounge — the Paimio Chair — facilitated their breathing due to its shape and the inclination of the backrest.

These approaches are examples of how design can be applied in a specific way to enhance people's well-being through gestures like spatial organization, color and shapes , thereby promoting architecture that contributes to health, care, and recovery, In this context, and as a result of explorations in this field, HEWI has developed ICONIC , infusing emotionally appealing color concepts for its design icon, the 477/801 barrier-free sanitary range. An essential element of this range's design was the concept of "healing architecture" within healthcare and daycare buildings and its influence on not just the physical and mental well-being of patients but also the welfare of other users, such as relatives and staff.

How Can Buildings Work for Everyone? The Future of Inclusivity and Accessibility in Architecture

One of the most important challenges in architecture, when it comes to creating spaces that work for everyone, is the diversity that exists in people, their needs, and how to integrate them into a design. Disabilities are more than a condition; they are a way of living according to human diversity that requires architectural solutions of equivalent multiplicity.

According to data from the World Bank, it is estimated that 1 billion people –equivalent to 15% of the world's population– live with some type of disability. In the future, this percentage could increase considerably, given the global trend of aging populations. To face this growing challenge, architecture will have to adapt quickly, due to the role that built environments have in constituting a barrier or a path for the inclusion of people with different types of disabilities, seniors, as well as diverse groups who make up the human plurality.

Inclusive Design that Meets the Needs of an Aging Society

The world's population is undergoing a significant demographic transformation , with an increasingly larger portion of people reaching older ages. This has prompted governments to implement public policies aimed at promoting the well-being of the growing number of elderly individuals worldwide. Alongside this trend, there is a need to address special needs that extend beyond just the elderly population and encompass various age groups. Advancements in medical science have enabled many people with disabilities or special needs to lead fuller and more independent lives, contributing to a more inclusive society. This progress also places a crucial responsibility on architects and designers, who must create built environments that are genuinely inclusive, and capable of accommodating a wide diversity of individuals with specific medical needs and varying levels of mobility. This underscores the fundamental importance of universal design and accessibility principles.

The Curb Cut Effect: How Accessible Architecture is Benefiting Everybody

The fabric of our cities is shaped by millions of small decisions and adaptations, many of which have become integral to our experience. Nowadays taken for granted, some of these elements were revolutionary at the time of their implementation. One such element is the curb cut, the small ramp grading down the sidewalk to connect it to the adjoining street, allowing wheelchair users and people with motor disabilities to easily move onto and off the sidewalk. This seemingly small adaptation has proven to be unexpectedly useful for a wider range of people, including parents with strollers, cyclists, delivery workers, etc. Consequently, it lends its name to a wider phenomenon, the “curb cut effect”, where accommodations and improvements made for a minority end up benefiting a much larger population in expected and unexpected ways.

Re-Purposing Materials: From Post-Industrial Recyclate to Accessible Furniture

The role and relationship of furniture in architecture and space design are of great relevance. Designers such as Eileen Gray, Alvar Aalto, Mies Van der Rohe, and Verner Panton conceived furniture —primarily stools and chairs— that endure over time as powerful and timeless elements, with a determining impact on the interior atmosphere. Thus, the relationship between furniture and space becomes a constant dialogue in which design, aesthetics, and materials contribute their dimension.

Today, furniture should not be limited solely to fulfilling an aesthetic and functional role, but should also have a purpose in the context of contemporary design and sustainable development. It is essential to reflect on and question the processes and choice of materials in the manufacturing of these elements, in addition to the value they bring to interior spaces. In this context, HEWI has taken a step forward by creating the Re-seat family , consisting of stools and chairs made from post-industrial recycled materials (PIR), sourced in part from the processes of the company itself and a regional supplier, both based in Bad Arolsen, Germany. It also features integrated solutions with universal design in mind , making a statement in favor of innovation and eco-design.

How to Guide People in Architectural Spaces with Tactile Paving Surfaces?

Theoretically, architecture is a multisensory discipline involving textures, colors, shadows, sounds, and aromas. However, in practice, using visual language is often prioritized to explore it, limiting mainly to sight for identifying architectural elements and navigating autonomously in built environments and urban contexts. Therefore, it is crucial to integrate tactile paving surfaces into architecture.

Blindness and vision impairment transcend being a condition or disability; they represent an alternative way of perceiving the environment around us. In this sense, touch becomes a language and a fundamental guide for interacting with architecture. According to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Article 9) , all individuals have an inherent right to access the physical environment on an equal basis with others.

Accessibility: 10 Ramps in Public and Domestic Spaces

The ramp is one of the architectural elements that, besides facilitating movement between different heights and floors, provide greater accessibility to spaces. In Brazil , a series of decrees and regulations seek to ensure citizenship rights and promote equality and social inclusion of people with disabilities, which permeates issues related to their mobility and freedom to come and go. Architecture plays a key role in this inclusion, by devising strategies to ensure that these people can transit, participate and interact in any environment, whether public or private.

Architecture for People with Hearing Loss: 6 Design Tips

Contrary to what we might believe, hearing loss is not always congenital, but could sooner or later happen to any of us. According to the WHO, almost a third of people over 65 suffer from debilitating hearing loss. Yet from a certain perspective, hearing loss could be considered more of a 'difference' than a 'disability'. Although the spatial demands of people with hearing disabilities are not as noticeable as spaces for the blind or for those who experience reduced mobility , the reduction of hearing capacity does entail a particular way of experiencing the environment. Is it possible to enhance this experience through interior design?

What is Universal Design?

Created by the American architect Ron Mace in the 1980s, the concept of Universal Design deals with the perception of the projects and environments that we design and inhabit, considering the possibility of its use by different user profiles: from children to the elderly, including language limitations and people with disability or temporary limitations.

Manhattan’s Center for Architecture Imagines the Future of Universal Design

How can Universal Design bridge the divides that have left many Americans stranded in their own communities? In its latest exhibition, Manhattan ’s Center for Architecture calls for a “reset.” On view until September 3, Reset: Towards a New Commons , displays projects that “encourage new modes of living collaboratively” and “more holistic approaches to inclusion.”

Local Can Be Universal

In the 14th century, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote “Familiarity breeds contempt”. By definition “local” is “familiar”. Why are humans so thrilled to go beyond the familiar, the local, and reach for what is new, universal, and salvational? The word “local” has the weight of true value, like “density” or “sustainable” But the lure of connection between all humans is powerfully seductive, and that desire to connect almost always falls short of our hopes.

Karen Braitmayer, Founder of Studio Pacifica, Weighs in on Accessible Design

Karen Braitmayer, a disabled architect, consultant, and volunteer, brings her unique life experiences to Studio Pacifica , the Seattle‐based practice she founded in 1993. With deep expertise in code compliance and regulations, Braitmayer and her team work with architectural firms like Olson Kundig and Perkins and Will to help create barrier‐free civic, residential, and commercial buildings. Studio Pacifica has served as consultants on notable projects ranging from the Space Needle renovation to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center and student housing at Smith College. Braitmayer was appointed by President Barack Obama to the United States Access Board, a position she still holds today.

As we mark the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) this month, we spoke to her about how far we’ve come, and how we can continue to advance accessible design in the built environment.

What Types of Residential Floors Favor Wheelchair Circulation?

One of the most important design considerations that residential architects have the responsibility to address is accessibility, ensuring that people with disabilities can comfortably live at home without impediments blocking basic home functionality. Accessibility for wheelchair users is a particularly important architectural concern due to unalterable spatial, material, and other requirements necessitated by wheelchair design and use. Because guaranteeing the comfort of all users, including disabled users, is one of the most essential obligations of all architects, designing for wheelchair users must be done with utmost the attention and care, especially in residential environments. Below, we delineate several strategies for designing floors for wheelchair circulation, helping architects achieve this goal of maximum comfort and accessibility.

How to Design Safe Bathrooms for the Elderly

There exist frequent reports of toilet accidents, as they are often located in tight and slippery places. Although no one is immune to a slip after bathing, it is the elderly who suffer most from falls, and can often suffer serious injuries, sequelae, and functional limitations. Due to the natural reduction of reflexes and muscle mass, the higher the age group, the more prone to falls we become.

To provide more comfortable living conditions as users grow older, the environment must adapt to the new physical capabilities of its occupants. Making toilets safer is critical to reducing the risk of accidents and decreasing response time in the event of a fall. Here are some things to keep in mind when designing toilets for older people:

Basic (And Necessary) Recommendations for Designing Accessible Homes

A good architecture project must be accessible to all, regardless of their physical or cognitive abilities. To raise awareness about these issues, and help you in the design process, we have compiled some basic actions that must be carried out for people to inhabit residential spaces comfortably and without obstacles.

It's important to remember that each country has its own regulations in relation to accessibility, so the specific dimensions presented below – based on the ' Universal Accessibility Guide ' by Ciudad Accesible – are conceptual and may vary for each project. Before designing an accessible home, review local guidelines and adhere to, if not exceed, listed needs and requirements, thus ensuring a good quality of life for users in the long term.

We Need More Wheelchair Users to Become Architects

When famed architect Michael Graves contracted a mysterious virus in 2003, a new chapter in his life began. Paralyzed from the chest down, the pioneer of Postmodernism would be permanently required to use a wheelchair. Graves could have been forgiven for believing that having fought for his life, having been treated in eight hospitals and four rehab clinics, and needing permanent use of a wheelchair, that his most influential days as an architect were behind him. This was not the case. To the contrary, he would use this new circumstance to design trend-setting hospitals, rehab centers, and other typologies right up to his death in 2015, all with a new-found awareness of the everyday realities of those in wheelchairs, and what architects were, and were not doing, to aid their quality of life.

Avanti-Avanti Studio: "Design for All, the Start of the Creative Process is Through Individual Diversity"

Avanti-Avanti Studio is a design studio dedicated to the development of creative communication strategies, particularly specialized in “Design for All.” Founded by Alex Dobaño (graphic designer and member of the Design For All Foundation) and Elvira Muñoz (architect), the duo leads a multidisciplinary team of professional people in communication, design, and technology, and work with companies and institutions specialized in leisure, tourism, culture, museums, and cities. They describe their practice as a meeting point, where professionals from different fields come together for every new venture, to ensure that the built environments are suitable and inclusive for anyone experiencing them.

We talked to Alex, founder and creative director of the studio, to learn more about their work and the importance of introducing the Design for All concept in the integrated space design projects.

Universal Design Architecture

When it comes to the design and planning of space, user accessibility and user experience play a significant role in the ideology of the design. Conventional design is perceived as “normal” that welcomes a certain type of user group that is offhandedly deemed as a typical layout. A casual observer may interpret the space as one that requires no modification for any type of user experience. This is where Universal Design architecture comes into focus to make the space easily accessible for all user groups. To adapt to the environment and to feel comfortable is an essential part of the consciousness of architecture.

The Disability Act of 2005 defines Universal Design as “the design and composition of any space that is accessible; comprehended and used to the greatest possible extent, most independently and naturally, within the widest possible range of situations, without the necessity to adapt, modify or use any assistive devices or specialized solutions , by a person of any age, size or having any particular physical, sensory, mental health, intellectual ability or disability.” Universal design takes into consideration during the pre-design, design, and construction stages that there is no one-size that fits all humans.

The Principles

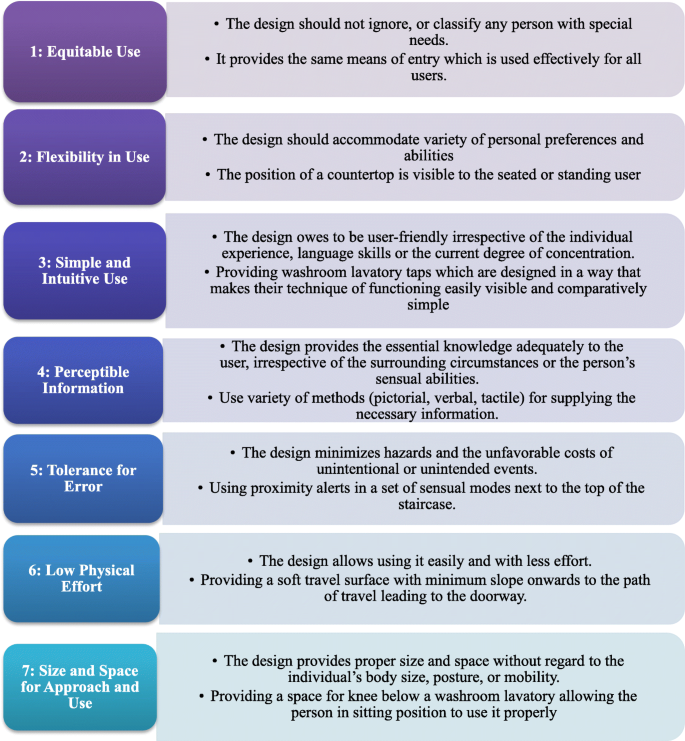

Architects, Engineers, and Environmental Design Researchers developed seven principles of Universal Design to help guide professionals to create a space to be more inclusive.

Equitable Use: The design transpires to be useful and marketable to people with diverse disabilities. Flexibility in use: The design tends to accommodate a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. Simple and intuitive: Regardless of the user’s experience, language skills, knowledge , or concentration level, the use of design is easy to understand. Perceptible information: Communication through design conveys necessary information effectively to the user, heedless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. Tolerance for error: The design intends to attenuate hazards and therefore the adverse consequences of accidental or unintentional actions. Low physical effort: The design is used efficiently and comfortably with ease and effortlessly. Size and space for approach and use: Size and space are aptly provided for approach, reach manipulation, and use nevertheless of user’s posture, body size, or mobility.

Eight Goals of Universal Design Architecture

The Eight goals of Universal Design were recently developed to clarify the concept of universal design, health, and wellness, to incorporate human performance, outcomes from social participation, and to address contextual and cultural issues. Addressing the barrier to adopt universal design in middle and low-income countries is acknowledged by having a perception that is often discerned as idealistic, expensive, or an imposition of western values. Hence, these goals link universal design with a knowledge base to identify measurable outcomes.

Body fit: The design accommodates a wide range of body sizes and abilities. Comfort: Demands that can be within desirable limits of body function. Awareness: Assuring the critical information to be easily perceived. Understanding: The methods of operation and use are made intuitive, explicit, and unambiguous. Wellness: Advancing in promoting health, avoiding diseases, and preventing injuries. Social integration: Regarding all individuals with dignity and respect. Personalization: Inculcating opportunities for choice and expressing individual preferences. Cultural appropriateness: The design project predominantly includes social, economic, and environmental context along with respecting and reinforcing cultural values.

Even though universal design has yet to gain acceptance in the design community, the focus of implementing universal design principles in outdoor as well as indoor environments is slowly expanding.

A manifestation of inner rejuvenation and community building, through master planning and adaptive reuse, the Enabling Village is an inclusive space that is an integration of work, education, retail, training, and connecting people with disabilities to society. The holistically integrated environment of the Nest navigates you through new linkages tracing the pedestrian flow throughout the space. The timber terrace laid over the courtyard stepping down as an amphitheater is integrated with ramps for people having disabilities that blend in with the seating area. Wayfinding is developed with a series of points of contact at strategic junctions that helps the user with orientation and navigation. With a barrier-free design and sustainable design solutions, the Enabling Village is a beacon of encouragement towards social interaction within a biophilic environment.

The Musholm extension envisions new experiences by including a traditional approach to accessible design and enhancing the quality of life for people with disabilities. To replenish the differences, a range of physical activities guides the handicapped to extend their boundaries. The multi-purpose hall has been integrated with accessibility and creative elements that inspire and challenge them. The 110-meter ramp running through the circular building distinguishes the path around the central spaces.

The Tongva Park and Ken Genser Square in Santa Monica were designed as a public space to be inclusive of all people. To navigate through the built environment and apply the principles of universal design that includes people with a wide array of disabilities such as physical, auditory, or visual disabilities, even neuro-cognitive disabilities is a challenge that we should face with creative certainty. The design of this urban landscape project embodies an experience that is active, resource-conscious, innovative, and natural. The urban space is precisely defined by wide fluid pathways, native landscape, seating areas with arms, play areas, lush green lawns that promote health and well-being.

Universal design plays a significant role in solving social situations and design responses based on usability and social participation. The integration of universal design has been growing and advancing every day and professionals are building a strong relationship with universal design to contribute to improving accessibility . In this stage of evolution of universal design, it is essential not to limit our designs to a certain group of users and make the space inclusive to all be it sustainability, workplaces, public places, or indoor spaces.

Universal design architecture will potentially reduce the effort and accommodate people with short-term and chronic disabilities.

References: | Universal Design Architecture

- Archdaily [Online]

Available at: www.archdaily.com

- Whole Building Design Guide: WBDG [Online]

Available at: https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/accessible/beyond-accessibility-universal-design

- American Society of Landscape Architects: ASLA [Online]

Available at: https://www.asla.org/universaldesign.aspx

Abha Haval is an Architect who has a vivid imagination of this world. She believes that every place has a story to tell and is on a mission to photograph the undiscovered whereabouts of various cities and narrate the story of its existence.

Preparing for the future cities in India

The Future is “Responsive” Architecture

Related posts.

The Role of Architectural Archives in Restoration Projects

Using meme culture to express social issues in architecture

The Theoretical Role of Soft Furnishings in Shaping Spatial Narratives

The New Architects: Designing the Future in Virtual Realms

Buildings redefining the Architectural trends

Revitalizing Vernacular Architecture

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

- Open access

- Published: 18 October 2021

Towards inclusion and diversity in the light of Universal Design: three administrative buildings in Aswan city as case studies

- M. E. Khalil 1 ,

- N. A. Mohamed 1 &

- E. A. Morghany 2

Journal of Engineering and Applied Science volume 68 , Article number: 15 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2671 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Publisher Correction to this article was published on 28 November 2021

This article has been updated

Social inclusion aims to achieve an inclusive society that entails respect for human diversity and upholds principles of equality and equity, allowing all groups to take part in the society. Universal Design (UD) promotes inclusiveness by supporting access for all and easy use of the built environment, thus eliminating any form of exclusion and discrimination.

This study examines the UD application in Aswan’s administrative buildings. The study relied on the descriptive, analytical, and inductive approach, through the identification of deficiencies in the selected administrative buildings’ design, and the clarification of development strategies to make these buildings for all. The case study method has two processes (approaches) in evaluating the case study buildings; the first was by the researchers according to UD requirements using the study’s checklist; the second was by users according to UD principles using interviews and task sheets.

This research aims at emphasizing the positive effects of UD application on the selected buildings. In addition, it also aims at determining the compatibility of those buildings with the UD concept.

The study result showed that the case study buildings are not compatible considerably with the requirements of the UD and its principles. The research concluded that architects should consider UD requirements and principles when designing administrative buildings and when rehabilitating and developing the existing ones.

Thus, the study’s outputs could be used as a guidance tool by architects and construction managers in introducing universally designed buildings to all users.

Introduction

Human diversity is a concept that sums up how different everyone is not just based on looks or their ethnicities, but on body shape or size, age, or abilities, while social inclusion is defined as the way to improve social participation conditions, especially for disadvantaged people, by improving opportunities, accessing services, and respecting rights to avoid insularity [ 1 ]. Exclusion is the main issue that faces permanent or temporary disabled people, and elders . Discrimination happens because all buildings are designed for only one category of people: those who do not have any kind of disability [ 2 ].

A fundamental goal of Universal Design (UD) is to consider the abilities and limitations of people to ensure that products and environments can be accessed and used easily with regard to all. To apply and activate this framework of UD in Egypt, it is necessary to be aware of the UD concept and its principles. In case that the authorities, the designers, and the owners are aware of UD, they will respect the UD concept and principles in any public and private building [ 3 ]. Clearly, there is a need for implementing UD well in Egypt. Also, it is essential to provide expert engineers, and researchers in this field, to raise awareness about UD in Egypt and to contribute to providing universally designed buildings to all users. Thus, this study is targeted to enhance social inclusion , accessibility, and UD implementation in administrative buildings in Egypt.

Public buildings mostly serve the aim of providing a service to citizens. Many of those services are provided gratis to residents. There are many varieties of public buildings including public schools, hospitals, libraries, courthouses, governmental offices, post offices, and administrative buildings [ 4 ]. Thus, this study focuses on administrative buildings to be evaluated in the light of UD. The research problem is to determine the extent of the compatibility of administrative buildings with the UD considerations, also to help in highlighting the concept of UD and its importance, and define how to apply it in administrative buildings.

The research’s aims are to contribute to highlighting the UD conception and how important it is to apply it to administrative buildings and to clarify that universally designed buildings are a crucial key factor in ensuring social inclusion and creating social sustainability , by assessing the extent of applying the UD approach in three significant administrative buildings in Aswan, which leads to determine if the elements of the buildings match the UD standards and principles and are accessible to all users. The scope of the study is focused on the aforementioned three administrative buildings as case studies at Aswan city, Egypt.

Literature review

History of universal design.

Within the 1970s, expanding people’s vision of people with disabilities galvanized the handicap movement to increase the demand for the removal of architectural barriers. In 1985, Universal Design expression was for the 1st time adopted across the USA thanks to Ronald Mace, in spite of the fact that relevant approaches of UD prevailed earlier in Europe [ 5 ].

Ron Mace, the constructor of the Center for Universal Design in 1985, anticipated Universal Design as a keystone for a more friendly and helpful world for everyone. First defined by Mace as an approach to design that allows for individual participation regardless of age and physical capabilities when UD is executed properly it introduces the advantages reachable world to any person, for instance, handicapped and normal people [ 6 ].

Universal Design concept

Human diversity is defined broadly; it encompasses groups defined by race, culture, gender, class, religion, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental ability, and national origin. Human diversity, in essence, is an all-encompassing notion that encompasses a wide range of people [ 7 ]. One major problem that faces contemporary society is the accessibility and usability for the physically disabled, elderly person. Usability and accessibility are two linked but distinct related aspects of a building. Usability implies accessibility in the sense that if the user cannot physically access the building, it is not usable by default. However, accessibility does not denote usability. For instance, an individual may be able to physically enter a building, but it may be too hard to obtain services inside, rendering the building inoperable [ 8 ]. There is a crucial need to increase awareness of accessibility and usability issues that face people with physical disabilities and to address their needs [ 9 ]. Design standards and practices based on a normal person fail to accommodate many users of varying capabilities; this led to the exclusion of many categories of people from the social and economic mainstream because of the inaccessible environment. UD places human differences in the core of the designing process so the designed building fits all types of people [ 10 ]. UD consequently, caters to all people, including any persons of different ages and sizes as well as people with different abilities or disabilities [ 11 ]. It is around to obtain a perfect design so that individuals can utilize, access, and recognize the environment as far as possible, and within the utmost autonomy, without the demand for adjustments or specialized designs. UD is not an accessibility synonym. In general, accessibility indicates minimum compliance with codes and requirements for people with disabilities [ 12 ]. UD is generally defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the utmost best extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” [ 13 ].

- Universal Design principles

The reason for creating the principles of UD and their related rules was to articulate the conception of UD in an entire way. The principles explain the authors’ conviction that essential UD principles could be applicable in all design specialties. The principles were set for the aim of leading the design process, enabling organized assessment of designs in addition to helping in clarifying the features of more user-friendly design solutions to the architects and consumers [ 14 ].

The Universal Design principles with examples are shown in Fig. 1 .

The principles of Universal Design [ 15 ]

Methodology

This study focuses on three administrative buildings as case studies to be assessed in light of the UD concept. The chosen case studies were selected based on their significance for the users, and the frequency of users’ visits to them. The three case studies are “the administrative building of the local unit of Aswan city (A)”, “Administrative building of Aswan University (B)”, and “Office of the National organization for Social Insurance—Government Sector (C)”.

The analytical approach was used to describe the current situation of the three buildings. Moreover, a case study research method was adopted in collecting data from three different administrative buildings in Aswan. The study was conducted with a qualitative description and direct observation in the three buildings. Site observations were made in light of the UD concept. The checklist and photographic documentation were analyzed qualitatively.

In 2001, Danford and Tauke defined the six elements of the design of a universally designed city which should be taken into consideration when implementing the 7 principles of the UD in built environments [ 16 ]. The six elements were Using Circulation Systems, Entering and Exiting, Wayfinding, Parking and Passenger Loading Zones, Obtaining product/services, and Using Public Amenities, also office rooms for administrative building. This study concentrated on the three basic elements from those six ones depending on their importance and great effectiveness on the building users. The assessment was confined to the accessible areas by the public only on all floors of the buildings. The three elements that were addressed in this research are as follows:

Using Circulation Systems : Mechanical Circulation Systems (Elevators), Ramps and Stairs, Hallways and Corridors

Entering and Exiting : identifying the Entrance and the Exit and maneuvering through them, departing the Entrance and Exit Areas

Wayfinding: paths/circulation, information system design, sign content, orientation aids

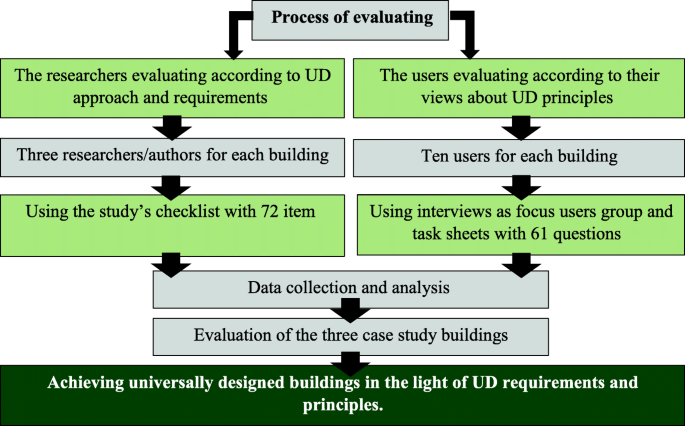

Two processes of evaluating were conducted in this study as shown in Fig. 2 .

The framework of the evaluation process of the case study buildings

The researchers’ evaluation

Site observations were made by the researcher in light of the UD concept for each building. The three buildings were evaluated individually by the researcher, using a checklist that evaluates the requirements of UD to each element of the building. The checklist of 72 items was designed to collect data. Each item gets “3 points if it fully achieved UD requirement”, “2 points if it partially achieved UD requirement”, and “1 point if it fully not achieved UD requirement”, so the total points for each building are 216. The points collected by the building are calculated and then divided by 216 to obtain the percentage of the building’s compliance with UD requirements

The users’ evaluation

The evaluation process in the light of universal design principles was done by ten users “evaluators” for each building, those users diverse in education level, gender, age, and abilities, including those who had the experience of a temporary movement disability, and who had a visual impairment. Each participant has a task sheet containing the required assignments to be performed. The evaluation process requires visiting the case study building and using the mentioned building elements. Then, interviews with users “evaluators” were conducted as focus users groups. For data collection about each case study building, a prepared list was used which consisted of 61 questions to be answered by the users through their interviews’ time.

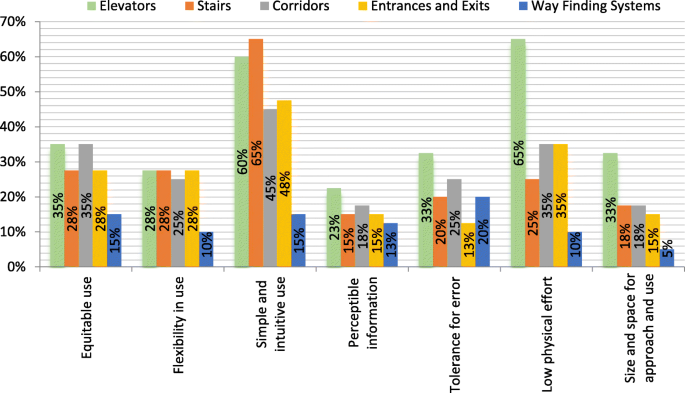

The respondents assessed the five selected elements (Using circulation system, Entering and Exiting, Wayfinding ) for each building of the three case studies. The assessment was through the seven principles of UD (equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, size, and space for approach and use).

The completed surveys were coded and entered into an SPSS 25.0 database for analysis. The results of the study tasks and list of 61 questions are statistically analyzed by using SPSS Ver. 25 program. Prevalent statistical techniques such as “descriptive statistics” and “cross-tabulation” were used. The completed surveys were coded and entered into an SPSS 23.0 database for analysis. Then, the validity of the data entered was ensured, that there are no missing data, which may affect the validity of the data. Each variable was calculated through its mean (average), according to each element, and each principle. The Reliability of Scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha test. Thereafter, descriptive statistics was made for the sample according to each building, calculating the average of each element with each one of the 7 UD principles. Afterward, the result of each building was compared with the relative weight of each principle of the seven ones (Table 1 ). The relative weights of the 7 UD principles were clarified according to their significance.

The checklist and the study tasks

The checklist was prepared depending on the UD approach, standards, and requirements. The facilities within the three selected case studies were assessed by the researcher’s observation as shown in Tables 2 & 3 .

Thereafter, the study tasks for the selected evaluators “users” were prepared depending on the UD seven principles. The task list contained 61 questions for each building of the three ones.

The case study

The local unit of aswan city.

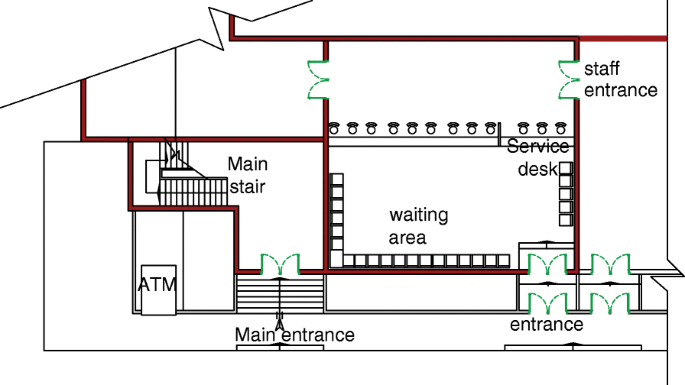

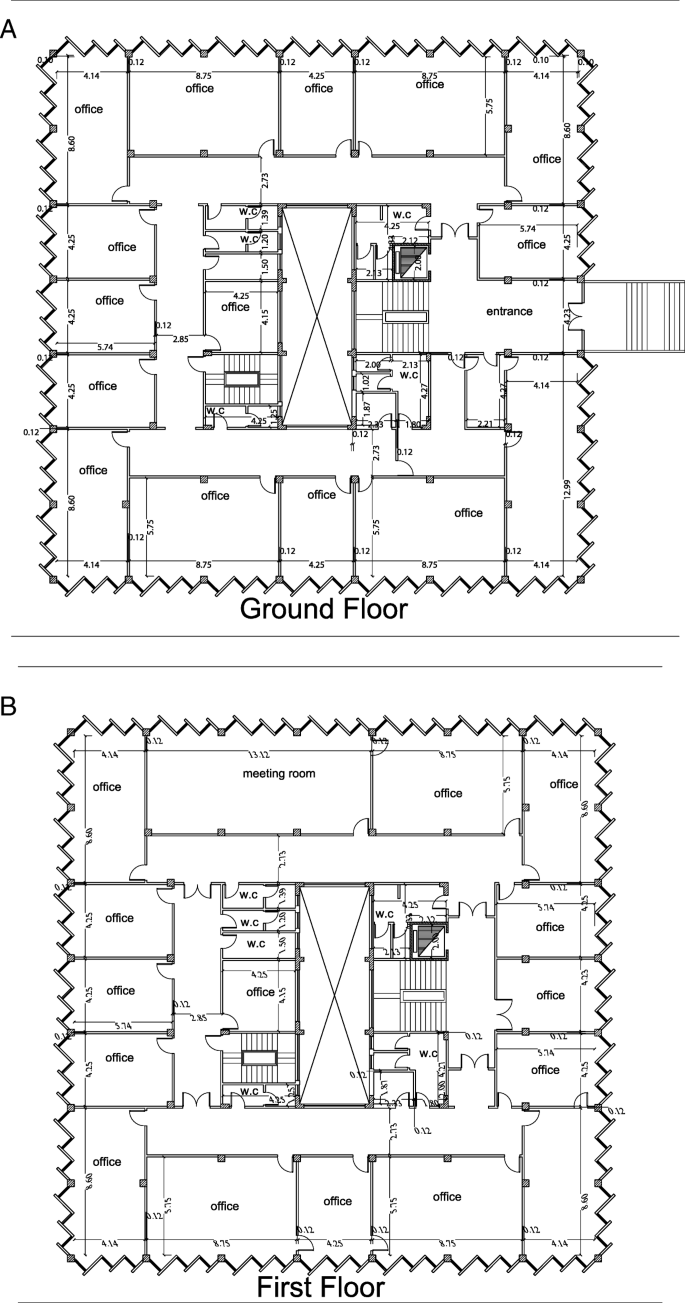

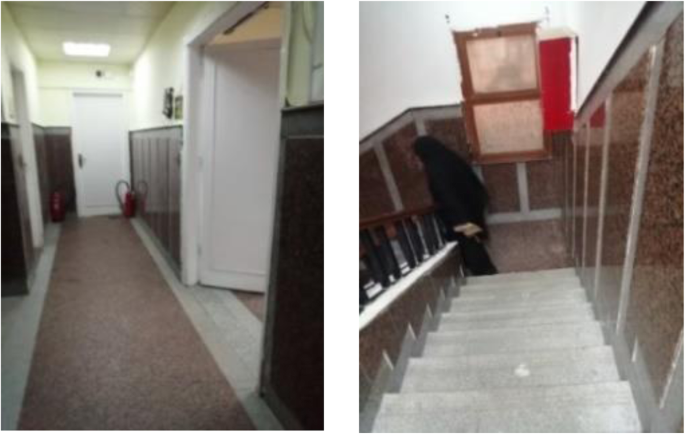

The local unit of Aswan city’s building is located in its downtown area; it has two entrances. The first entrance leads to “the technological center for the citizens’ service”, whereas the second one leads to “the presidency of Aswan city’s local unit”. The local unit building consists of 4 floors but does not have elevators or any other means of vertical contact except stairs, which led to the emergence of a problem concerning the difficulty of the vertical communication between the building’s floors (Fig. 3 ).

Sketch floor plan for entrances and the stairs in building A. Drawn by the researcher

Despite the vertical communication problem in the building, it is limited to its second section only, “the presidency of Aswan city’s local unit”; the first section is supposed to be easily accessible due to its composition of one ground floor only, but the entrance is difficult to be reached too by wheelchair users because of the existence of two stairsteps with no curb ramp. Likewise, the entrances’ doors for the building are less than 1.5-m wide as illustrated in Fig. 4 A. The signage system in the second section of the building “the presidency of Aswan city’s local unit” does not suit all users, as it does not adopt the Braille system and its high-level theme does not allow wheelchair users to read it as displayed in Fig. 4 B.

The entrance and the signage in the first section of the building, 2020

The building’s second partition is not accessible enough due to the two grades at the entrance pavement, beside the seven grades at the entrance, as seen in Fig. 5 A moreover, the absence of elevators, no or rudimentary service desk as presented in Fig. 5 B, and no waiting areas. Corridors and stairs have suitable widths but still do not suit the blind or the deaf users as shown in Fig. 6 . The internal doors of the building vary in width, but they all need a considerable effort to be opened, and their handles’ height does not suit all users, and they do not accommodate different users and movement types as displayed in Fig. 7 ; there is no guidance system or uniform pattern of signs, and if they are found, some of them are unclear; they do not have the Braille system and no proper level of placement that is easy to be touched or read, and there are no tactile, sound, and visual indicators in entrances, exits, and the path of travel. Floor levels and their uses are not well-defined as shown in Fig. 8 .

The entrance in the second section, the service desk is rudimentary, 2020

The corridors and the stairs, 2020

Different types of interior doors, 2020

There are no maps, directories, and displays, 2020

Aswan University administrative building

The building is located in Aswan University campus at Sahari city, Aswan. The administrative building includes 4 floors and a basement; the building has two entrances; the first entrance is located on the ground floor, while the second one is located in the basement, as shown in the plans of the building as illustrated in Fig. 9 . However, there is a problem in entering the building, because the entries do not have any ramps or blocks to guide the visually impaired people, or a tactile form of alert in the beginning and the end of the stairs as presented in Fig. 10 . Next to each entrance, there is a stair on its edge; the main staircase is next to the main entrance, while the emergency stair is alongside the second entrance. Both of them do not have more than 10 risers between landings, but there are no tactile indicators on railings like grooves or bumps to mark the beginning and the end of a stairway as seen in Fig. 11 . The building has one elevator close to the main entrance, with a front space that allows people to gather before entry, but obstructing the circulation flow in the building; the elevator’s space is not enough to allow wheelchair users to rotate 180°; there are no contrasts between objects like doorway frames, calling buttons, faceplate, key numbering, and their backgrounds. Operable parts of all calling buttons and control panels are more than 120 cm so it cannot serve all users; the elevator car has a bar in the front wall which can help users with different abilities as displayed in Fig. 12 . There is no voice alert for the elevator’s floor number. Corridors’ width is suitable for anyone but when using them as waiting areas or when placing cabinets, their widths do not suit all users, in addition to the lack of audio, visual, or tactile means as shown in Fig. 13 . The interior doors’ widths are suitable, but the handle’s height is unsuitable for people in a sitting position and need more force to be opened, and have bottom bumpers with a height of 20 cm used as wheel bumpers and a resistance to friction and shock material, but their height should be 40 cm. The double doors in the corridors are wide enough and always open to avoid obstructing the circulation flow as seen in Fig. 14 . The building lacks in the Information System Design—no directional signs and no maps. Sectional names are clearly identified in the elevator lobby, but there is a lack of tactile, sound, and visual indicators as presented in Fig. 15 .

Plans of Aswan University’s administrative building. Photo source: Architectural Engineering Department at Aswan University

The entrance is difficult to be used due to lack of ramps and guiding blocks (2020)

The main stair is 1.7 m in width, while the emergency stair is 1 m in width (2020)

The building has one elevator (2020)

The corridors’ widths are suitable for wheelchair users (2020)

The interior doors’ widths are 80–90 cm (2020)

The building lacks the Information System Design (2020)

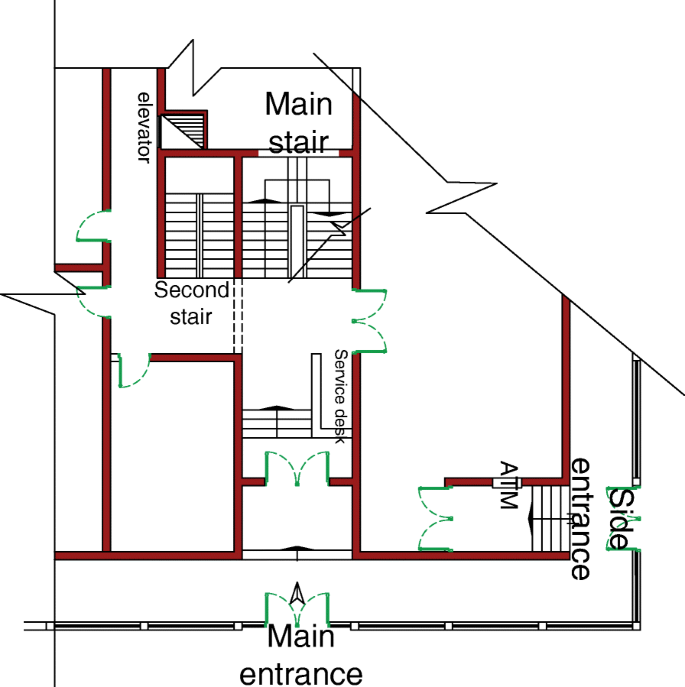

The National Organization for Social Insurance—Government Sector

The building is located in the downtown area in “Nafak” neighborhood. The building consists of a ground floor and five stories. The social insurance building is newly constructed in the latest 10 years; it presents services to pensioners, that is, more than 60% of its users are elderly users; despite that, it is not designed to accommodate their different abilities.

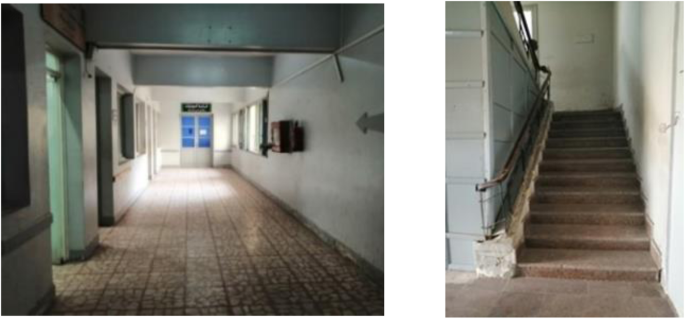

The building has two entrances —main and side entrances. However, there is a problem in entering the building, because the entries do not have any ramps or blocks to guide the visually impaired people, or a tactile form of alert in the beginning and the end of the stairs as presented in Fig. 16 . The automated teller machine (ATM) is next to the side entrance stairs, which disturbs movement. As for the main entrance, it is next to the Service Desk; this creates confusion and crowding from the users of the Service Desk and users of the main entrance stair. The entrance has two raised thresholds that prevent the use of people with different mobility abilities (Fig. 16 ). The width of corridors is small to allow two people to pass in two different directions, as illustrated in Fig. 17 .

The entrance does not meet the universal design principles’ standard. Researcher, 2021

The corridors and the stairs. 2021

The building contains the main stair with a width of 110 cm and the emergency stair with a width of 90 cm. The two stairs do not have any tactile indicators to indicate their beginning or end; also, their widths are not suitable to accommodate the expected traffic flow (Fig. 17 ). There are no signs to direct the users inside the building or show the services provided on each floor, and the existing signs do not serve those with different visual capabilities; signs are explaining the required administrative papers and signs of the room’s labels, but they are not designed universally (Fig. 18 ). There is one elevator in the building, it has an unclear location from the entrance, and there is no adequate waiting area for the public to gather in front of it, its area does not allow full rotation for wheelchair users. Figure 19 shows the ground floor sketch plan for the evaluated elements “entrance and stairs” in building C, by the researchers.

Signs of required administrative papers and room’s labels. 2021

The floor sketch plan for entrance and stairs in building C. Drawn by the researcher

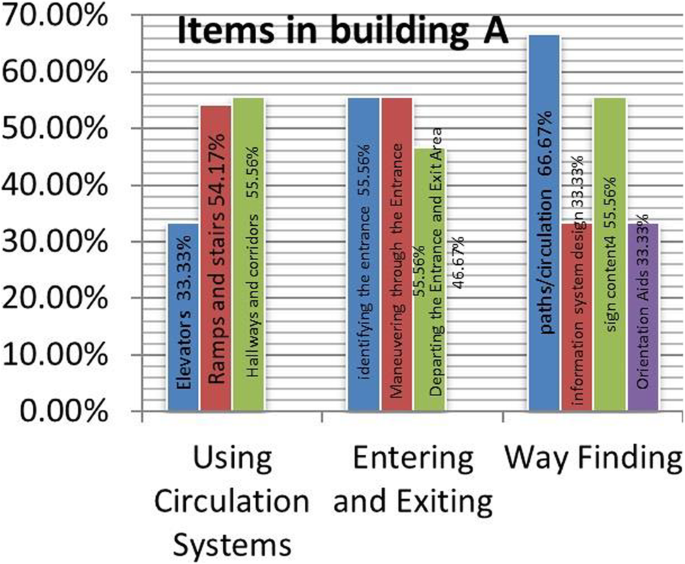

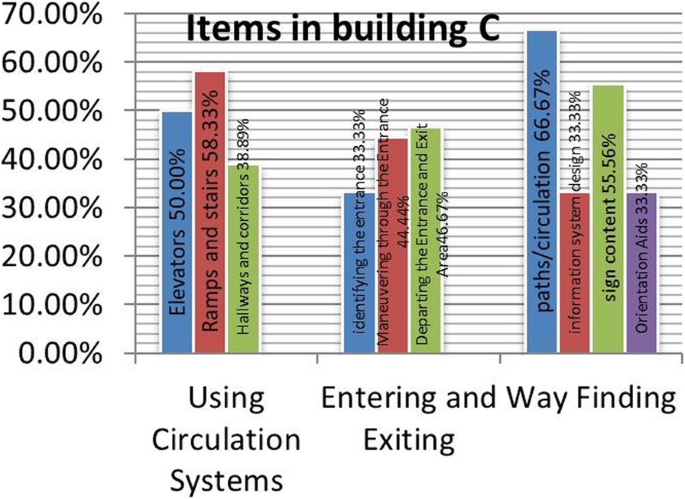

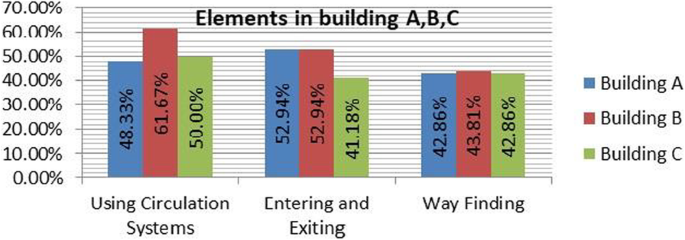

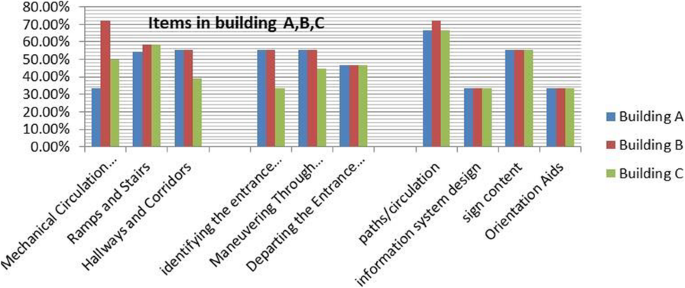

Result of the researchers’ evaluation according to UD requirements

The researcher evaluation results showed that building A “ The Local Unit of Aswan City ” obtained 46.76% of compliance to UD requirements, while the total percentage of their compliance to UD requirements was 50.93% for building B “ Aswan University administrative building ”. Building C “ The National Organization for Social Insurance—Government Sector ” obtained 44.44% of compliance with UD requirements. In a more detailed analysis, the percentage of the UD requirements for each design element is shown by the ratios in Figs. 20 , 21 , and 22 .

Percentage of compliance to UD for the elements in building A

Percentage of compliance to UD for the elements in building B

Percentage of compliance to UD for the elements in building C

Based on the abovementioned detailed percentage, the study observed that “ Using Circulation systems ” in building B achieved the highest percentage ( 61.67% ) than building C ( 50.00% ) and building A ( 48.33% ) as illustrated in Fig. 23 . The absence of elevators in building A has an effective role in the building score. More detailed analysis showed that the item “ Hallways and Corridors ” in buildings A and B were equal with 55.56%, while “ Mechanical Circulation Systems ” ( Elevators ) was the lowest item with 33.33% in building A. Regarding the “ Ramps and Stairs ” item, the ratios were close to each other in the three buildings as illustrated in Fig. 24 .

The summation score of compliance to UD for each element in the three buildings

Percentage of compliance to UD for the detailed items in the three buildings

The design element “ Entering and Exiting ” and its items were equal in buildings A and B by 52.94% as shown in Fig. 23 ; “Departing the Entrance and Exit Area” item achieved the percentage of 46.67% in the three buildings due to the absence of multiple physical signs which participate in recognizing the building outlets. Regarding the “Identifying the entrance and exit” and “Maneuvering through the Entrance or Exit” items, the ratios were equal in buildings A and B with 55.56% for both, and 33.33%, 44.44% in building C, as illustrated in Fig. 24 ).

The study result showed that the “ Wayfinding ” element was equal in buildings A and C and obtained 42.86% even though, building B ratio was 43.81% as illustrated in Fig. 23 . The Convergence of “ Wayfinding ” ratios, in the three buildings is due to the absence of a clear information system design in all of them. In detail, the research showed that the item “ Paths / Circulation ” in building B achieved the highest percentage of 72.22% than buildings B and C, while the items “ Information System Design ”, “ Sign Content ” and Orientation Aids were equal in the three buildings as illustrated in Fig. 24 .

It is clear from the previous ratios that building “C” has the least compliance with UD requirements, despite the fact that it is the most recent of them in terms of construction and provides its services to elderly users. And after analyzing the previous results, it became clear that there were no tactile, sound, and visual indicators in any element of the study buildings. The absence of ramps limits accessibility to the entrances in all case study buildings, even the newly constructed ones. Corridors have a very appropriate width in old study buildings, but the misuse reduces the efficiency of their performance. In the newly constructed building, the small widths of the corridors impede access to rooms for those in the sitting position. The omission of the Information System Design in all study buildings limits the accessibility within the buildings.

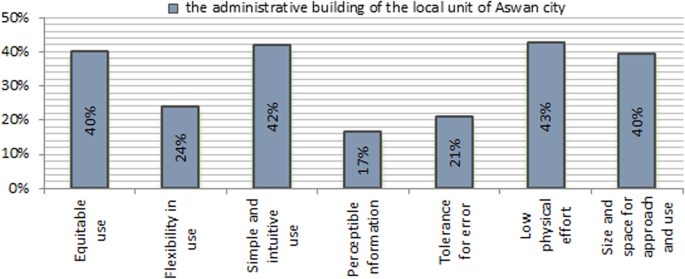

Result of the users’ evaluation according to UD principals

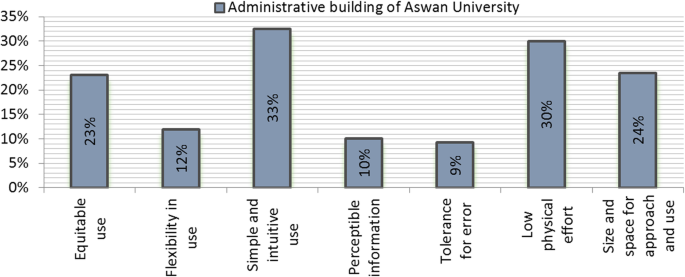

Regarding building A, the users’ evaluation results revealed that the UD principles (simple and intuitive use, and low physical effort) achieved the highest percentage 42% and 43%, respectively, though their “relative weights” were 11.12%, which referred to their middle importance. Also, the principle “perceptible information” achieved the lowest ratio of 17% that is compatible with its relative weight of 7.9% as shown in Fig. 25 .

The users’ evaluation results about compliance of all elements with each UD principle in building A “the administrative building of the local unit of Aswan city”

It is clear that Building A has no “Elevator”, and the results showed that “Stairs” achieved the highest percentage in compliance with each UD principle, although, “Wayfinding” obtained the lowest percentage with each UD principle as, there is no “Wayfinding” system, as in Fig. 26 .

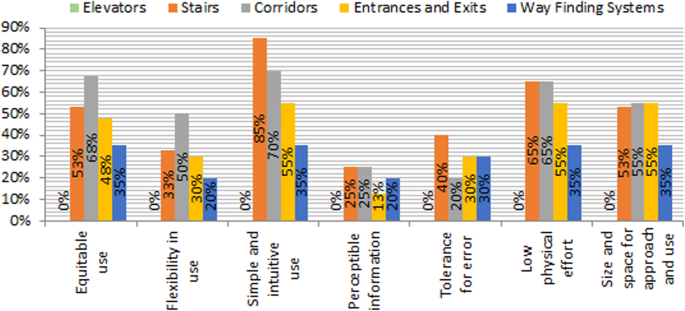

Compliance of each element with each one of UD principles in building A “the administrative building of the local unit of Aswan city”

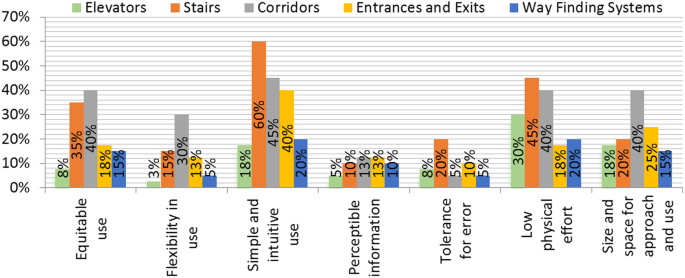

With respect to building B, the highest percentage was achieved by principles (simple and intuitive use, and low physical effort) 33% and 30%, respectively. For Size and space for approach and use principles, the results affirmed that its ratio was 24%, despite its relative weight was 25.26%, which referred to its highest significance, as presented in Fig. 27 .

The users’ evaluation results about compliance of all elements with each UD principle in building B “Administrative building of Aswan University”

The “elevators” attained a low percentage in compliance with UD principles. “Stairs” and “Corridors” accomplished convergent percentages with each UD principle. Also, “Entering and exit” obtained a decreased percentage with UD principles excluding “Simple and intuitive use” and “Size and space for approach and use” as displayed in Fig. 28 .

Compliance of each element with each one of UD principles in building B “Administrative building of Aswan University”

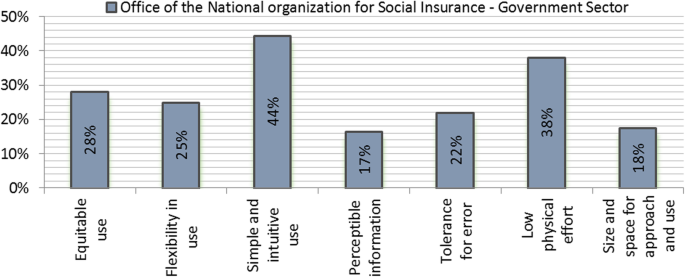

Concerning building C, the users’ results displayed that the principles “Size and Space for Approach and Use” and “Perceptible Information” achieved the decreased percentage of 18% and 17%, respectively. Though “Perceptible Information principle” has the lowest relative weight of 7.91%; nevertheless, “Size and Space for Approach and Use principle” attained the highest relative weight of 25.26%. It is obvious that “Equitable Use principle” had the middle significance with a relative weight of 14.34% and obtained 28% of compliance of UD principles, as shown in Fig. 29 .

The users’ evaluation results about compliance of all elements with each UD principle in building C “The National Organization for Social Insurance—Government Sector”

“Elevators” accomplished 56% in compliance with the UD principles. Even though, “Stairs”, “Corridors”, and “Entrances and exits” achieved convergent percentage with all principles of UD except the stairs with “Simple and Intuitive Use” obtain the highest percentage of 65%. Thus, “Wayfinding” obtained the lowest percentage with all UD principles excluding “Tolerance for Error principle”, as shown in Fig. 30 .

Compliance of each element with each one of UD principles in building C “The National Organization for Social Insurance—Government Sector”

Ultimately, it is apparent in the three case study buildings, that Perceptible Information principle is the most absent and not applied one, while, Simple and Intuitive Use principle is the most existing and applied one

It was clear from the result that the case studies do not apply considerably the UD requirements and principle. So, it is required to amend many design elements of the building to improve its usability to all users to ensure social inclusion and create social sustainability.

A comparison between the “UD requirements” and “The Egyptian code for designing outdoor spaces and buildings for the disabled” (CODE 601) was done by the researcher in a previous study. The comparison outcomes revealed that the UD approach and its principles are broad and inclusive.

After reviewing the results of the researchers and users of the case study buildings, the outcomes’ convergence was proven. Without a doubt, the users’ evaluation besides the researchers is recommended in future researches. But, the users’ opinion should be an assistive tool not basic for assessing and obtaining more accurate results, since most normal users do not feel the problems facing others.

From the study and analysis of the previous results, a set of problems of usability, accessibility and inclusiveness were identified in the three case studies. These problems led to discrimination and social exclusion for a specific group of people who have weak physical abilities. Hence, it is necessary to study and focus on these problems and classify them to be solved, consequently, preventing this social discrimination.

Many of these problems can be solved by either adding some elements or integrating a particular system or creating some architectural elements. However, some problems are difficult to be resolved as shown in Table 4 .

Recommendation

The following are recommendations from this study’s results:

▪ Working on implementing the proposed amendments to improve access in the case studies buildings

▪ The importance of conducting analytical surveys involving Administrative Buildings to rehabilitate them to be in line with the Universal Design requirements

▪ Educating designers, architects, and engineers on the necessity of paying attention to the needs of all people by using the UD requirements, considering future changes when designing and constructing Administrative Buildings

▪ The need to create and design a new Egyptian code for the requirements of the UD in Administrative Buildings in Egypt which differed from The Egyptian code for designing outdoor spaces and buildings for the disabled

▪ Making a possible adjustment that follows the UD approach in the existing Administrative Buildings to accommodate the needs of all users

▪ Ensure the inclusion of all types of people in the design process, construction, and administration

Universal design (UD) is not a privilege or a luxury for places, communities, or cities. UD is the creation of goods and environments that can be used as much as possible by all individuals, with no need for modification or specialized design. The goal of the research is to help emphasize the concept of UD and how important it is to apply it to administrative buildings and to acknowledge that universally designed constructions are a key factor in ensuring social integration and social sustainability. This study explores the compatibility of the administrative buildings in Aswan city with the UD requirements and principles. The assessment of administrative buildings in the light of the UD concept was through many elements; this study focused on some of them. The findings of this research revealed that the three case studies did not adequately meet the UD concept and principles. The study outcomes which were concluded together by the researchers and buildings’ users were more accurate. Therefore, it is recommended to utilize the building users’ evaluation in future researches. Also, the study recommends some modifications and improvements for the building elements to ensure usability and inclusion to all users.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this submitted article.

Change history

28 november 2021.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-021-00048-2

Abbreviations

Universal design

The automated teller machine

United Nations Deparment of Economic and Social Affairs. (2016). Report on the World Social Situation. In Report on the World Social Situation (pp. 17–32). https://www.un-ilibrary.org/economic-and-social-development/report-on-the-world-social-situation-2016_5890648c-en

Afacan, Y., & Erbug, C. (2009). An interdisciplinary heuristic evaluation method for universal building design. Appl Ergon, 40(4), 731–744. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2008.07.002

Policy, E., Application, B. L., Services, V. H., Planning, V., Services, H., Approval, P. B., & Building, P. (2011). Guidelines for public buildings. July.

Copeland, E. (2014). Promoting Universal Design in public buildings: an action research study of community participation. http://aut.researchgateway.ac.nz/handle/10292/7713

Yuen, F. K. O., & Pardeck, J. T. (1998). Impact of human diversity education on social work students. Int J Adolesc Youth, 7(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.1998.9747827

Blanck, D. (n.d.). The coming importance of Universal Design - progressive AE. https://www.progressiveae.com/importance-universal-design/

Erlandson, R. F., & Group, F. (2008). Universal and accessible design for products, services, and processes. In Universal and Accessible Design for Products, Services, and Processes. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420007664

Al-Tal, S. M. (2002). Integrated Universal Design: a solution for everyone. The Unioa Institute.

Souza, S. C. de, & Post, A. P. D. de O. (2016). Universal Design: an urgent need. Procedia Soc Behav Sci, 216(October 2015), 338–344. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.046

Ahmed MEK (2016) An assessment of street design with Universal Design principles: case in Aswan / As-Souq. MEGARON Yıldız Tech Univ Fac Arch E-J 11(4):616–628 https://doi.org/10.5505/megaron.2016.98704

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Ahmed, M. E. K. (2020). Exploring inclusiveness in green hotels for sustainable development in Egypt. 1(1), 15–23.

Wolfgang F., E. P., & Korydon H., S. (2011). Universal desigh handbook. In Universal Design Hand Book.

Kadir, S. A., & Jamaludin, M. (2012). Applicability of Malaysian standards and Universal Design in public buildings in Putrajaya. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.072

Danford, G. S., & Tauke, B. (2001). Universal Design NewYork 2. Center for inclusive design & environmental access, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

North Carolina State University, T. C. for U. D. (1997). The center for Universal Design - Universal Design principles. In the Principles of Universal Design (pp. 1–4). https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciplestext.htm

ÖZDEMİR Y, ÖZDEMİR Ş (2020) Weighthing the Universal Design principles using multi-criteria decision making techniques. Mühendislik Bilimleri ve Tasarım Dergisi 8(1):105–118 https://doi.org/10.21923/jesd.427505

Article Google Scholar

Kapedani E, Herssens J, Verbeeck G (2019) Designing for the future? Integrating energy efficiency and universal design in Belgian passive houses. Energy Res Soc Sci 50(July 2018):215–223 https://doi.org/gercdd

Download references

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the helpful plans of Aswan University’s administrative building under this study provided by the Architectural Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering at Aswan University.

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan, Egypt

M. E. Khalil & N. A. Mohamed

Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Assuit University, Assuit, Egypt

E. A. Morghany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ME analyzed and interpreted the data regarding the study buildings. NA collected the data and photographic documentation. EA was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to M. E. Khalil or N. A. Mohamed .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khalil, M.E., Mohamed, N.A. & Morghany, E.A. Towards inclusion and diversity in the light of Universal Design: three administrative buildings in Aswan city as case studies. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 68 , 15 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-021-00020-0

Download citation

Received : 07 May 2021

Accepted : 30 August 2021

Published : 18 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-021-00020-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Universal Design (UD)

- Administrative buildings

- Human diversity

- Social inclusion

- Universal Design

- Case Studies & Evidence-Based Design

- Design for All Ages

- Products & Materials

- Boards & Presentations

- Feedback for us on this page? Please share it here.

Log in to Read Ebooks (DI Students, Faculty and Staff)

To read these ebooks, click the links below and use your Microsoft 365 login credentials (your DI email address and password).

You can also click the LIRN Library tab in Canvas , which will take you to the LIRN Library Portal and log you into all of the library resources. Need help? Contact the DI Library .

Ebooks - login required

- AIA COTE Top Ten by Varun Kohli - Find Award-Winning Projects

- Buildings by Type | Architectural Record

- Universal Design Case Study Collection | Institute for Human Centered Design

- Research 101, Part I: Research-Based Practice The first of a 3-part series that provides an introduction to research methods and how you might use research in design practice.

- Research 101, Part II: Research Vocabulary The second of a 3-part series that provides an introduction to research methods and how you might use research in design practice.

- Research 101, Part III: Research Methods The second of a 3-part series that provides an introduction to research methods and how you might use research in design practice.

Books and Magazines in the DI Library

Cite Your Sources

When your instructor doesn’t care how you cite as long as you do cite, make sure to include the information someone would need to find your source on their own. A citation for a case study might look like this:

“The Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building” case study. AIA Top Ten. http://www.aiatopten.org/node/494 .

Cite It Where You Use It

Every time you use a quotation, a piece of information, or an image from another source, cite the source right where you use it , whether it’s on your project board or in your paper, job book or presentation.

Include enough information to allow your audience to figure out which source (from your complete list at the end) you’re citing. For example, if you use the case study in the example above, the citation on your board or presentation slide might be “Edith Green."

- Library materials about evidence-based design, including case studies

- Websites about evidence-based design, including case studies

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: Universal Design >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 1:28 PM

- URL: https://disd.libguides.com/universal-design

The Design Institute of San Diego Library

The Design Institute of San Diego | 855 Commerce Avenue | San Diego, CA 92121 | (858) 566-1200 x 1019

Sign up for our free newsletter and get more of Development Asia delivered to your inbox.

Using Universal Design to Make the Built Environment More Accessible

Singapore is making buildings and living and work spaces accessible to all.

Retrofitting and revamping access to all buildings in a whole country is a massive task. The Building and Construction Authority has been driving the Singapore government’s efforts in creating a barrier-free country that is accessible to people of all ages and abilities. Since the Code on Barrier-Free Accessibility in Buildings was implemented in 1990, the accessibility of buildings in Singapore has improved significantly. As the Code was applied only to new building projects, the Building Construction Authority had to come up with various ways to upgrade the existing building stock. This was a enormous task, given the sheer number of properties built before the Code came into effect.

This case study was adapted from Urban Solutions of the Centre for Liveable Cities in Singapore .

Along with Singapore’s rapid urbanization from the 1950s to 1980s, a dense, high-rise built environment was created. As the majority of the population then was young and able, the need to provide barrier-free accessibility was not a critical concern. The focus was on maximizing land resources for the economic and social needs of a growing population.

The year 1990 saw a milestone in Singapore’s accessibility efforts. Although the population was still fairly young, the Code on Barrier-Free Accessibility in Buildings was introduced to help improve accessibility standards, especially for wheelchair users. The design and construction requirements set out in the Code were mandatory for all new building projects. The Code benefits anyone with physical limitations, including elderly individuals who are not wheelchair bound.

It had been estimated that between 2006 and 2030, the number of senior citizens, many of whom would face deteriorating physical abilities, would increase threefold. Thus, the goal of cultivating an inclusive built environment that supported “ageing-in-place” was conceived, to help individuals adapt to ageing in their homes—surroundings familiar to them. This would also allow families to care for older members more easily.

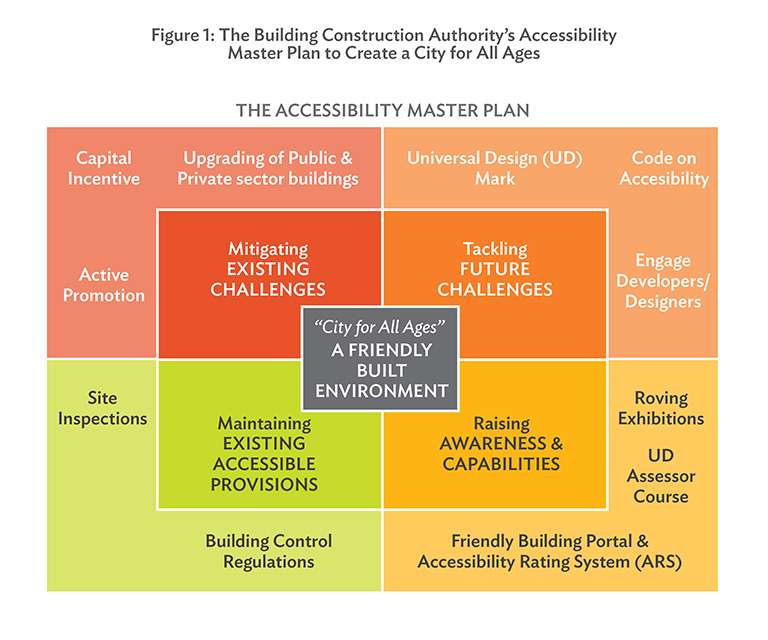

The Building Construction Authority has incorporated the concept of universal design, or “design for all,” into its mission to address the needs of people of all ages and abilities. With this goal, a key challenge was upgrading the large existing stock of buildings built before the 1990 Accessibility Code came into force. There was also a need to go beyond providing barrier-free accessibility within buildings and ensure that the surroundings of buildings are similarly barrier-free.

In 2006, the Building Construction Authority started a big push for universal design with the launch of the Accessibility Master Plan. Holistic and collaborative in nature, the plan allows the Building Construction Authority to work with other government agencies to tackle the challenges of creating a user-friendly built environment in Singapore.

To address older buildings that were not barrier-free, the Building Construction Authority implemented an accessibility upgrading program from 2006 to 2011, targeting buildings and areas regularly visited by the public.

Since 2007, the Building Construction Authority has been advising government agencies on the upgrading of public-sector buildings with a set of basic features for accessibility, which covers the approach to buildings and the first story of the buildings, including a toilet on that level. The Building Construction Authority has also played a role in facilitating and monitoring the upgrading process.

To incentivize owners of private-sector buildings to upgrade their premises to be barrier-free, the Building Construction Authority introduced the Accessibility Fund in 2007, which co-pays up to 80% of the total cost of refurbishing buildings to include basic accessibility features. In particular, the Building Construction Authority worked with building owners to improve accessibility along Orchard Road, a popular shopping district where most of the buildings were built before the introduction of mandatory requirements in 1990.

The Accessibility Code has undergone several revisions and updates to meet the needs of the time. The last review of the Code was conducted between 2011 and 2013. It was a collaborative effort involving the people, private and public sectors. Numerous public consultations, focus group discussions and user trials with stakeholders were held to ensure that the Code was comprehensive and could benefit more Singaporeans.

For example, the 2013 Code review highlighted the need for more facilities that could cater to people with diverse needs. Child-friendly sanitary facilities and family car park lots have thus become required in buildings such as sports complexes and large shopping malls. Other features that have become mandatory include Braille and tactile information for public toilet signs, and hearing enhancement systems in venues such as function rooms and auditoriums. The Code was also refined to include wider corridors to allow easy access for wheelchairs and prams.

At the same time, the Building Construction Authority continues to encourage developers, building owners, designers and other industry stakeholders to apply universal design in new developments and those undergoing upgrading. To encourage stakeholders to do more than just comply with the Code, the Building Construction Authority promotes universal design through courses, roving exhibitions and seminars. It also began giving out Universal Design Awards in 2007 to recognize development projects that show extensive efforts in applying universal design concepts with user-friendly features. A “sensory garden” open for public viewing at the Building Construction Authority Academy serves as a model to demonstrate the universal design concept.

To widen outreach efforts, the Building Construction Authority has begun to rate the user-friendliness of buildings. This information is available in the Friendly Buildings Portal, where users can check the level of accessibility of a building. A mobile application has also been developed for this purpose.

Today, people using wheelchairs and other mobility aids are no longer confined to their homes. They can often be seen moving around neighborhood markets, food centers, shopping malls and activity centers with ease. As of March 2012, close to 100% of public-sector buildings regularly frequented by the public had achieved basic accessibility, while the proportion of buildings along the Orchard Road shopping belt providing basic accessibility had increased significantly to 88%, from 41% in 2006.

In 2012, the Universal Design Awards was replaced by the Building Construction Authority Universal Design Mark, a voluntary certification scheme that recognizes building owners for their efforts in incorporating universal design into their developments. As of May 2017, 149 building projects had received the Building Construction Authority Universal Design Mark. As part of their design briefs, many developers now indicate their desire to achieve Platinum rating, the highest standard, for the Building Construction Authority Universal Design Mark. In 2013, the Building Construction Authority Universal Design Mark was recognized as an innovative practice at the international Zero Project Conference at the United Nations Office in Vienna, Austria.

John Keung. 2015. No More Barriers: Promoting Universal Design in Singapore. Urban Solutions, Issue 6: Active Mobility . February 2015. The Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore.

Case study: Enhancing Urban Spaces with Pedestrian-Friendly, Mixed-Use Development

Case study: Rejuvenating an Old Residential Area by Crafting and Activating New Civic Spaces

Case Study: How to Build a Competitive and Livable City

Ask the Experts

The mission of the Centre for Liveable Cities in Singapore is to distil, create and share knowledge on liveable and sustainable cities. CLC’s work spans four main areas—Research, Capability Development, Knowledge Platforms, and Advisory. Through these activities, CLC hopes to provide urban leaders and practitioners with the knowledge and support needed to make our cities better.

View the discussion thread.

You Might Also Like

How Can Asian Banks Navigate the Uncertain Macro Environment?

Five Emerging Key Technologies Driving a Clean Energy Transition in the US

The Economics of Climate Change in the Pacific