5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

by Sarah Kliff

It is never easy to contemplate the end-of-life, whether its own our experience or that of a loved one.

This has made a recent swath of beautiful essays a surprise. In different publications over the past few weeks, I've stumbled upon writers who were contemplating final days. These are, no doubt, hard stories to read. I had to take breaks as I read about Paul Kalanithi's experience facing metastatic lung cancer while parenting a toddler, and was devastated as I followed Liz Lopatto's contemplations on how to give her ailing cat the best death possible. But I also learned so much from reading these essays, too, about what it means to have a good death versus a difficult end from those forced to grapple with the issue. These are four stories that have stood out to me recently, alongside one essay from a few years ago that sticks with me today.

My Own Life | Oliver Sacks

As recently as last month, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. In a beautiful op-ed , published in late February in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he'll face his final moments. What I liked about this essay is how Sacks describes how his world view shifts as he sees his time on earth getting shorter, and how he thinks about the value of his time.

Before I go | Paul Kalanithi

Kalanthi began noticing symptoms — "weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough" — during his sixth year of residency as a neurologist at Stanford. A CT scan revealed metastatic lung cancer. Kalanthi writes about his daughter, Cady and how he "probably won't live long enough for her to have a memory of me." Much of his essay focuses on an interesting discussion of time, how it's become a double-edged sword. Each day, he sees his daughter grow older, a joy. But every day is also one that brings him closer to his likely death from cancer.

As I lay dying | Laurie Becklund

Becklund's essay was published posthumonously after her death on February 8 of this year. One of the unique issues she grapples with is how to discuss her terminal diagnosis with others and the challenge of not becoming defined by a disease. "Who would ever sign another book contract with a dying woman?" she writes. "Or remember Laurie Becklund, valedictorian, Fulbright scholar, former Times staff writer who exposed the Salvadoran death squads and helped The Times win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the 1992 L.A. riots? More important, and more honest, who would ever again look at me just as Laurie?"

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat | Liz Lopatto

Dorothy Parker was Lopatto's cat, a stray adopted from a local vet. And Dorothy Parker, known mostly as Dottie, died peacefully when she passed away earlier this month. Lopatto's essay is, in part, about what she learned about end-of-life care for humans from her cat. But perhaps more than that, it's also about the limitations of how much her experience caring for a pet can transfer to caring for another person.

Yes, Lopatto's essay is about a cat rather than a human being. No, it does not make it any easier to read. She describes in searing detail about the experience of caring for another being at the end of life. "Dottie used to weigh almost 20 pounds; she now weighs six," Lopatto writes. "My vet is right about Dottie being close to death, that it’s probably a matter of weeks rather than months."

Letting Go | Atul Gawande

"Letting Go" is a beautiful, difficult true story of death. You know from the very first sentence — "Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die" — that it is going to be tragic. This story has long been one of my favorite pieces of health care journalism because it grapples so starkly with the difficult realities of end-of-life care.

In the story, Monopoli is diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, a surprise for a non-smoking young woman. It's a devastating death sentence: doctors know that lung cancer that advanced is terminal. Gawande knew this too — Monpoli was his patient. But actually discussing this fact with a young patient with a newborn baby seemed impossible.

"Having any sort of discussion where you begin to say, 'look you probably only have a few months to live. How do we make the best of that time without giving up on the options that you have?' That was a conversation I wasn't ready to have," Gawande recounts of the case in a new Frontline documentary .

What's tragic about Monopoli's case was, of course, her death at an early age, in her 30s. But the tragedy that Gawande hones in on — the type of tragedy we talk about much less — is how terribly Monopoli's last days played out.

Most Popular

Red lobster’s mistakes go beyond endless shrimp, cholera is making a comeback — and the world doesn’t have enough vaccines, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, 20 years of bennifer, explained, the air quality index and how to use it, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Politics

Birth control is good, actually

3 theories for America’s anti-immigrant shift

What the Biden administration is doing about ludicrously expensive concert tickets

The Supreme Court's new voting rights decision is a love letter to gerrymandering

How worried should we be about Russia putting a nuke in space?

“Everyone is absolutely terrified”: Inside a US ally’s secret war on its American critics

The Comstock Act, the long-dead law Trump could use to ban abortion, explained

Red Lobster’s mistakes go beyond endless shrimp Audio

The sundress discourse, explained

The science of near-death experiences Audio

People bet on sports. Why not on anything else?

- Death And Dying

8 Popular Essays About Death, Grief & the Afterlife

Updated 05/4/2022

Published 07/19/2021

Joe Oliveto, BA in English

Contributing writer

Cake values integrity and transparency. We follow a strict editorial process to provide you with the best content possible. We also may earn commission from purchases made through affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure .

Death is a strange topic for many reasons, one of which is the simple fact that different people can have vastly different opinions about discussing it.

Jump ahead to these sections:

Essays or articles about the death of a loved one, essays or articles about dealing with grief, essays or articles about the afterlife or near-death experiences.

Some fear death so greatly they don’t want to talk about it at all. However, because death is a universal human experience, there are also those who believe firmly in addressing it directly. This may be more common now than ever before due to the rise of the death positive movement and mindset.

You might believe there’s something to be gained from talking and learning about death. If so, reading essays about death, grief, and even near-death experiences can potentially help you begin addressing your own death anxiety. This list of essays and articles is a good place to start. The essays here cover losing a loved one, dealing with grief, near-death experiences, and even what someone goes through when they know they’re dying.

Losing a close loved one is never an easy experience. However, these essays on the topic can help someone find some meaning or peace in their grief.

1. ‘I’m Sorry I Didn’t Respond to Your Email, My Husband Coughed to Death Two Years Ago’ by Rachel Ward

Rachel Ward’s essay about coping with the death of her husband isn’t like many essays about death. It’s very informal, packed with sarcastic humor, and uses an FAQ format. However, it earns a spot on this list due to the powerful way it describes the process of slowly finding joy in life again after losing a close loved one.

Ward’s experience is also interesting because in the years after her husband’s death, many new people came into her life unaware that she was a widow. Thus, she often had to tell these new people a story that’s painful but unavoidable. This is a common aspect of losing a loved one that not many discussions address.

2. ‘Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat’ by Elizabeth Lopatto

Not all great essays about death need to be about human deaths! In this essay, author Elizabeth Lopatto explains how watching her beloved cat slowly die of leukemia and coordinating with her vet throughout the process helped her better understand what a “good death” looks like.

For instance, she explains how her vet provided a degree of treatment but never gave her false hope (for instance, by claiming her cat was going to beat her illness). They also worked together to make sure her cat was as comfortable as possible during the last stages of her life instead of prolonging her suffering with unnecessary treatments.

Lopatto compares this to the experiences of many people near death. Sometimes they struggle with knowing how to accept death because well-meaning doctors have given them the impression that more treatments may prolong or even save their lives, when the likelihood of them being effective is slimmer than patients may realize.

Instead, Lopatto argues that it’s important for loved ones and doctors to have honest and open conversations about death when someone’s passing is likely near. This can make it easier to prioritize their final wishes instead of filling their last days with hospital visits, uncomfortable treatments, and limited opportunities to enjoy themselves.

3. ‘The terrorist inside my husband’s brain’ by Susan Schneider Williams

This article, which Susan Schneider Williams wrote after the death of her husband Robin Willians, covers many of the topics that numerous essays about the death of a loved one cover, such as coping with life when you no longer have support from someone who offered so much of it.

However, it discusses living with someone coping with a difficult illness that you don’t fully understand, as well. The article also explains that the best way to honor loved ones who pass away after a long struggle is to work towards better understanding the illnesses that affected them.

4. ‘Before I Go’ by Paul Kalanithi

“Before I Go” is a unique essay in that it’s about the death of a loved one, written by the dying loved one. Its author, Paul Kalanithi, writes about how a terminal cancer diagnosis has changed the meaning of time for him.

Kalanithi describes believing he will die when his daughter is so young that she will likely never have any memories of him. As such, each new day brings mixed feelings. On the one hand, each day gives him a new opportunity to see his daughter grow, which brings him joy. On the other hand, he must struggle with knowing that every new day brings him closer to the day when he’ll have to leave her life.

Coping with grief can be immensely challenging. That said, as the stories in these essays illustrate, it is possible to manage grief in a positive and optimistic way.

5. Untitled by Sheryl Sandberg

This piece by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s current CEO, isn’t a traditional essay or article. It’s actually a long Facebook post. However, many find it’s one of the best essays about death and grief anyone has published in recent years.

She posted it on the last day of sheloshim for her husband, a period of 30 days involving intense mourning in Judaism. In the post, Sandberg describes in very honest terms how much she learned from those 30 days of mourning, admitting that she sometimes still experiences hopelessness, but has resolved to move forward in life productively and with dignity.

She explains how she wanted her life to be “Option A,” the one she had planned with her husband. However, because that’s no longer an option, she’s decided the best way to honor her husband’s memory is to do her absolute best with “Option B.”

This metaphor actually became the title of her next book. Option B , which Sandberg co-authored with Adam Grant, a psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, is already one of the most beloved books about death , grief, and being resilient in the face of major life changes. It may strongly appeal to anyone who also appreciates essays about death as well.

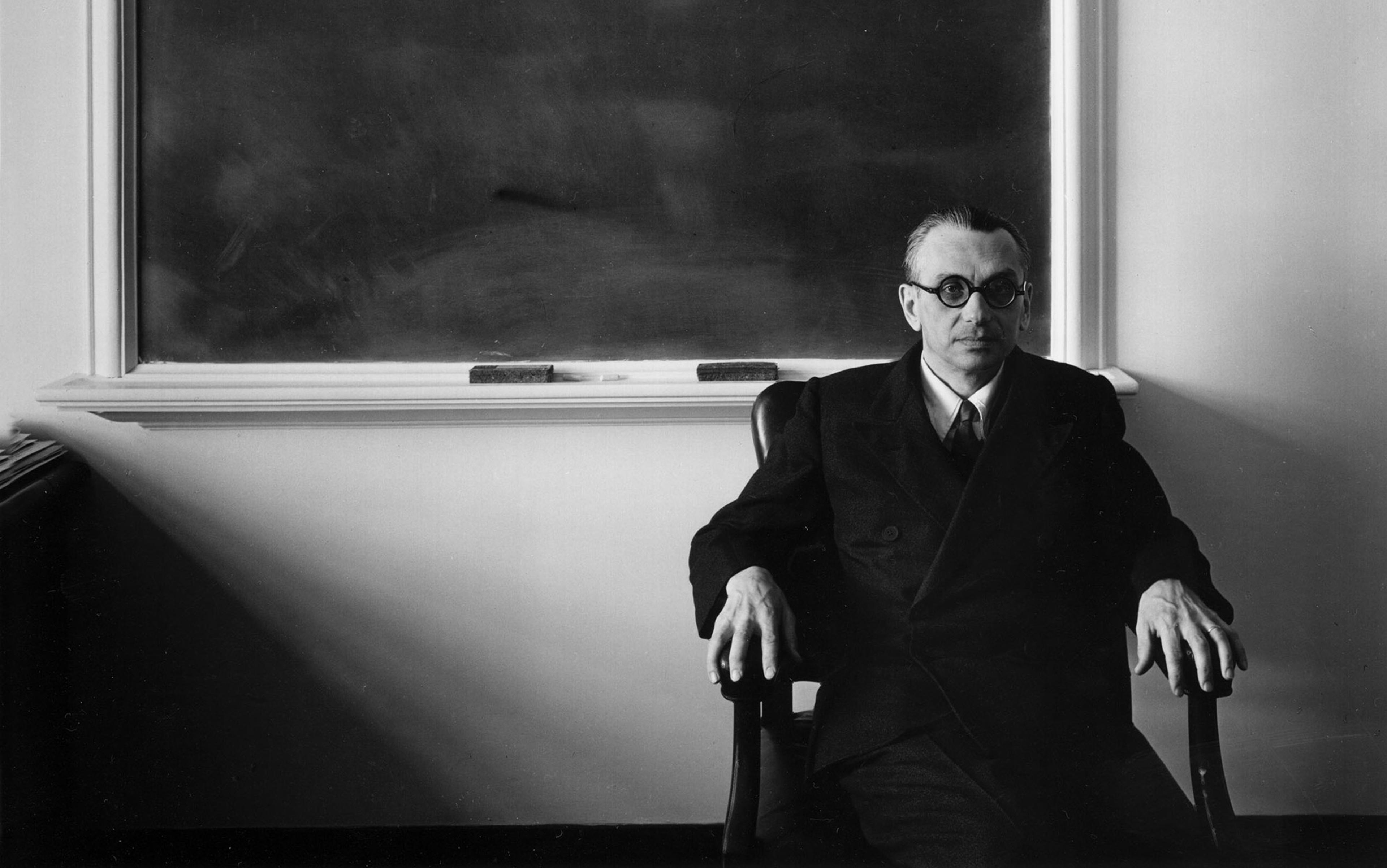

6. ‘My Own Life’ by Oliver Sacks

Grief doesn’t merely involve grieving those we’ve lost. It can take the form of the grief someone feels when they know they’re going to die.

Renowned physician and author Oliver Sacks learned he had terminal cancer in 2015. In this essay, he openly admits that he fears his death. However, he also describes how knowing he is going to die soon provides a sense of clarity about what matters most. Instead of wallowing in his grief and fear, he writes about planning to make the very most of the limited time he still has.

Belief in (or at least hope for) an afterlife has been common throughout humanity for decades. Additionally, some people who have been clinically dead report actually having gone to the afterlife and experiencing it themselves.

Whether you want the comfort that comes from learning that the afterlife may indeed exist, or you simply find the topic of near-death experiences interesting, these are a couple of short articles worth checking out.

7. ‘My Experience in a Coma’ by Eben Alexander

“My Experience in a Coma” is a shortened version of the narrative Dr. Eben Alexander shared in his book, Proof of Heaven . Alexander’s near-death experience is unique, as he’s a medical doctor who believes that his experience is (as the name of his book suggests) proof that an afterlife exists. He explains how at the time he had this experience, he was clinically braindead, and therefore should not have been able to consciously experience anything.

Alexander describes the afterlife in much the same way many others who’ve had near-death experiences describe it. He describes starting out in an “unresponsive realm” before a spinning white light that brought with it a musical melody transported him to a valley of abundant plant life, crystal pools, and angelic choirs. He states he continued to move from one realm to another, each realm higher than the last, before reaching the realm where the infinite love of God (which he says is not the “god” of any particular religion) overwhelmed him.

8. “One Man's Tale of Dying—And Then Waking Up” by Paul Perry

The author of this essay recounts what he considers to be one of the strongest near-death experience stories he’s heard out of the many he’s researched and written about over the years. The story involves Dr. Rajiv Parti, who claims his near-death experience changed his views on life dramatically.

Parti was highly materialistic before his near-death experience. During it, he claims to have been given a new perspective, realizing that life is about more than what his wealth can purchase. He returned from the experience with a permanently changed outlook.

This is common among those who claim to have had near-death experiences. Often, these experiences leave them kinder, more understanding, more spiritual, and less materialistic.

This short article is a basic introduction to Parti’s story. He describes it himself in greater detail in the book Dying to Wake Up , which he co-wrote with Paul Perry, the author of the article.

Essays About Death: Discussing a Difficult Topic

It’s completely natural and understandable to have reservations about discussing death. However, because death is unavoidable, talking about it and reading essays and books about death instead of avoiding the topic altogether is something that benefits many people. Sometimes, the only way to cope with something frightening is to address it.

Categories:

- Coping With Grief

You may also like

What is a 'Good Death' in End-of-Life Care?

11 Popular Websites About Death and End of Life

18 Questions About Death to Get You Thinking About Mortality

15 Best Children’s Books About the Death of a Parent

Essays About Death: Top 5 Examples and 9 Essay Prompts

Death includes mixed emotions and endless possibilities. If you are writing essays about death, see our examples and prompts in this article.

Over 50 million people die yearly from different causes worldwide. It’s a fact we must face when the time comes. Although the subject has plenty of dire connotations, many are still fascinated by death, enough so that literary pieces about it never cease. Every author has a reason why they want to talk about death. Most use it to put their grievances on paper to help them heal from losing a loved one. Some find writing and reading about death moving, transformative, or cathartic.

To help you write a compelling essay about death, we prepared five examples to spark your imagination:

1. Essay on Death Penalty by Aliva Manjari

2. coping with death essay by writer cameron, 3. long essay on death by prasanna, 4. because i could not stop for death argumentative essay by writer annie, 5. an unforgettable experience in my life by anonymous on gradesfixer.com, 1. life after death, 2. death rituals and ceremonies, 3. smoking: just for fun or a shortcut to the grave, 4. the end is near, 5. how do people grieve, 6. mental disorders and death, 7. are you afraid of death, 8. death and incurable diseases, 9. if i can pick how i die.

“The death penalty is no doubt unconstitutional if imposed arbitrarily, capriciously, unreasonably, discriminatorily, freakishly or wantonly, but if it is administered rationally, objectively and judiciously, it will enhance people’s confidence in criminal justice system.”

Manjari’s essay considers the death penalty as against the modern process of treating lawbreakers, where offenders have the chance to reform or defend themselves. Although the author is against the death penalty, she explains it’s not the right time to abolish it. Doing so will jeopardize social security. The essay also incorporates other relevant information, such as the countries that still have the death penalty and how they are gradually revising and looking for alternatives.

You might also be interested in our list of the best war books .

“How a person copes with grief is affected by the person’s cultural and religious background, coping skills, mental history, support systems, and the person’s social and financial status.”

Cameron defines coping and grief through sharing his personal experience. He remembers how their family and close friends went through various stages of coping when his Aunt Ann died during heart surgery. Later in his story, he mentions Ann’s last note, which she wrote before her surgery, in case something terrible happens. This note brought their family together again through shared tears and laughter. You can also check out these articles about cancer .

“Luckily or tragically, we are completely sentenced to death. But there is an interesting thing; we don’t have the knowledge of how the inevitable will strike to have a conversation.”

Prasanna states the obvious – all people die, but no one knows when. She also discusses the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Research also shows that when people die, the brain either shows a flashback of life or sees a ray of light.

Even if someone can predict the day of their death, it won’t change how the people who love them will react. Some will cry or be numb, but in the end, everyone will have to accept the inevitable. The essay ends with the philosophical belief that the soul never dies and is reborn in a new identity and body. You can also check out these elegy examples .

“People have busy lives, and don’t think of their own death, however, the speaker admits that she was willing to put aside her distractions and go with death. She seemed to find it pretty charming.”

The author focuses on how Emily Dickinson ’s “ Because I Could Not Stop for Death ” describes death. In the poem, the author portrays death as a gentle, handsome, and neat man who picks up a woman with a carriage to take her to the grave. The essay expounds on how Dickinson uses personification and imagery to illustrate death.

“The death of a loved one is one of the hardest things an individual can bring themselves to talk about; however, I will never forget that day in the chapter of my life, as while one story continued another’s ended.”

The essay delve’s into the author’s recollection of their grandmother’s passing. They recount the things engrained in their mind from that day – their sister’s loud cries, the pounding and sinking of their heart, and the first time they saw their father cry.

Looking for more? Check out these essays about losing a loved one .

9 Easy Writing Prompts on Essays About Death

Are you still struggling to choose a topic for your essay? Here are prompts you can use for your paper:

Your imagination is the limit when you pick this prompt for your essay. Because no one can confirm what happens to people after death, you can create an essay describing what kind of world exists after death. For instance, you can imagine yourself as a ghost that lingers on the Earth for a bit. Then, you can go to whichever place you desire and visit anyone you wish to say proper goodbyes to first before crossing to the afterlife.

Every country, religion, and culture has ways of honoring the dead. Choose a tribe, religion, or place, and discuss their death rituals and traditions regarding wakes and funerals. Include the reasons behind these activities. Conclude your essay with an opinion on these rituals and ceremonies but don’t forget to be respectful of everyone’s beliefs.

Smoking is still one of the most prevalent bad habits since tobacco’s creation in 1531 . Discuss your thoughts on individuals who believe there’s nothing wrong with this habit and inadvertently pass secondhand smoke to others. Include how to avoid chain-smokers and if we should let people kill themselves through excessive smoking. Add statistics and research to support your claims.

Collate people’s comments when they find out their death is near. Do this through interviews, and let your respondents list down what they’ll do first after hearing the simulated news. Then, add their reactions to your essay.

There is no proper way of grieving. People grieve in their way. Briefly discuss death and grieving at the start of your essay. Then, narrate a personal experience you’ve had with grieving to make your essay more relatable. Or you can compare how different people grieve. To give you an idea, you can mention that your father’s way of grieving is drowning himself in work while your mom openly cries and talk about her memories of the loved one who just passed away.

Explain how people suffering from mental illnesses view death. Then, measure it against how ordinary people see the end. Include research showing death rates caused by mental illnesses to prove your point. To make organizing information about the topic more manageable, you can also focus on one mental illness and relate it to death.

Check out our guide on how to write essays about depression .

Sometimes, seriously ill people say they are no longer afraid of death. For others, losing a loved one is even more terrifying than death itself. Share what you think of death and include factors that affected your perception of it.

People with incurable diseases are often ready to face death. For this prompt, write about individuals who faced their terminal illnesses head-on and didn’t let it define how they lived their lives. You can also review literary pieces that show these brave souls’ struggle and triumph. A great series to watch is “ My Last Days .”

You might also be interested in these epitaph examples .

No one knows how they’ll leave this world, but if you have the chance to choose how you part with your loved ones, what will it be? Probe into this imagined situation. For example, you can write: “I want to die at an old age, surrounded by family and friends who love me. I hope it’ll be a peaceful death after I’ve done everything I wanted in life.”

To make your essay more intriguing, put unexpected events in it. Check out these plot twist ideas .

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

May 3, 2023

Contemplating Mortality: Powerful Essays on Death and Inspiring Perspectives

The prospect of death may be unsettling, but it also holds a deep fascination for many of us. If you're curious to explore the many facets of mortality, from the scientific to the spiritual, our article is the perfect place to start. With expert guidance and a wealth of inspiration, we'll help you write an essay that engages and enlightens readers on one of life's most enduring mysteries!

Death is a universal human experience that we all must face at some point in our lives. While it can be difficult to contemplate mortality, reflecting on death and loss can offer inspiring perspectives on the nature of life and the importance of living in the present moment. In this collection of powerful essays about death, we explore profound writings that delve into the human experience of coping with death, grief, acceptance, and philosophical reflections on mortality.

Through these essays, readers can gain insight into different perspectives on death and how we can cope with it. From personal accounts of loss to philosophical reflections on the meaning of life, these essays offer a diverse range of perspectives that will inspire and challenge readers to contemplate their mortality.

The Inevitable: Coping with Mortality and Grief

Mortality is a reality that we all have to face, and it is something that we cannot avoid. While we may all wish to live forever, the truth is that we will all eventually pass away. In this article, we will explore different aspects of coping with mortality and grief, including understanding the grieving process, dealing with the fear of death, finding meaning in life, and seeking support.

Understanding the Grieving Process

Grief is a natural and normal response to loss. It is a process that we all go through when we lose someone or something important to us. The grieving process can be different for each person and can take different amounts of time. Some common stages of grief include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. It is important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve and that it is a personal process.

Denial is often the first stage of grief. It is a natural response to shock and disbelief. During this stage, we may refuse to believe that our loved one has passed away or that we are facing our mortality.

Anger is a common stage of grief. It can manifest as feelings of frustration, resentment, and even rage. It is important to allow yourself to feel angry and to express your emotions healthily.

Bargaining is often the stage of grief where we try to make deals with a higher power or the universe in an attempt to avoid our grief or loss. We may make promises or ask for help in exchange for something else.

Depression is a natural response to loss. It is important to allow yourself to feel sad and to seek support from others.

Acceptance is often the final stage of grief. It is when we come to terms with our loss and begin to move forward with our lives.

Dealing with the Fear of Death

The fear of death is a natural response to the realization of our mortality. It is important to acknowledge and accept our fear of death but also to not let it control our lives. Here are some ways to deal with the fear of death:

Accepting Mortality

Accepting our mortality is an important step in dealing with the fear of death. We must understand that death is a natural part of life and that it is something that we cannot avoid.

Finding Meaning in Life

Finding meaning in life can help us cope with the fear of death. It is important to pursue activities and goals that are meaningful and fulfilling to us.

Seeking Support

Seeking support from friends, family, or a therapist can help us cope with the fear of death. Talking about our fears and feelings can help us process them and move forward.

Finding meaning in life is important in coping with mortality and grief. It can help us find purpose and fulfillment, even in difficult times. Here are some ways to find meaning in life:

Pursuing Passions

Pursuing our passions and interests can help us find meaning and purpose in life. It is important to do things that we enjoy and that give us a sense of accomplishment.

Helping Others

Helping others can give us a sense of purpose and fulfillment. It can also help us feel connected to others and make a positive impact on the world.

Making Connections

Making connections with others is important in finding meaning in life. It is important to build relationships and connections with people who share our values and interests.

Seeking support is crucial when coping with mortality and grief. Here are some ways to seek support:

Talking to Friends and Family

Talking to friends and family members can provide us with a sense of comfort and support. It is important to express our feelings and emotions to those we trust.

Joining a Support Group

Joining a support group can help us connect with others who are going through similar experiences. It can provide us with a safe space to share our feelings and find support.

Seeking Professional Help

Seeking help from a therapist or counselor can help cope with grief and mortality. A mental health professional can provide us with the tools and support we need to process our emotions and move forward.

Coping with mortality and grief is a natural part of life. It is important to understand that grief is a personal process that may take time to work through. Finding meaning in life, dealing with the fear of death, and seeking support are all important ways to cope with mortality and grief. Remember to take care of yourself, allow yourself to feel your emotions, and seek support when needed.

The Ethics of Death: A Philosophical Exploration

Death is an inevitable part of life, and it is something that we will all experience at some point. It is a topic that has fascinated philosophers for centuries, and it continues to be debated to this day. In this article, we will explore the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, considering questions such as what it means to die, the morality of assisted suicide, and the meaning of life in the face of death.

Death is a topic that elicits a wide range of emotions, from fear and sadness to acceptance and peace. Philosophers have long been interested in exploring the ethical implications of death, and in this article, we will delve into some of the most pressing questions in this field.

What does it mean to die?

The concept of death is a complex one, and there are many different ways to approach it from a philosophical perspective. One question that arises is what it means to die. Is death simply the cessation of bodily functions, or is there something more to it than that? Many philosophers argue that death represents the end of consciousness and the self, which raises questions about the nature of the soul and the afterlife.

The morality of assisted suicide

Assisted suicide is a controversial topic, and it raises several ethical concerns. On the one hand, some argue that individuals have the right to end their own lives if they are suffering from a terminal illness or unbearable pain. On the other hand, others argue that assisting someone in taking their own life is morally wrong and violates the sanctity of life. We will explore these arguments and consider the ethical implications of assisted suicide.

The meaning of life in the face of death

The inevitability of death raises important questions about the meaning of life. If our time on earth is finite, what is the purpose of our existence? Is there a higher meaning to life, or is it simply a product of biological processes? Many philosophers have grappled with these questions, and we will explore some of the most influential theories in this field.

The role of death in shaping our lives

While death is often seen as a negative force, it can also have a positive impact on our lives. The knowledge that our time on earth is limited can motivate us to live life to the fullest and to prioritize the things that truly matter. We will explore the role of death in shaping our values, goals, and priorities, and consider how we can use this knowledge to live more fulfilling lives.

The ethics of mourning

The process of mourning is an important part of the human experience, and it raises several ethical questions. How should we respond to the death of others, and what is our ethical responsibility to those who are grieving? We will explore these questions and consider how we can support those who are mourning while also respecting their autonomy and individual experiences.

The ethics of immortality

The idea of immortality has long been a fascination for humanity, but it raises important ethical questions. If we were able to live forever, what would be the implications for our sense of self, our relationships with others, and our moral responsibilities? We will explore the ethical implications of immortality and consider how it might challenge our understanding of what it means to be human.

The ethics of death in different cultural contexts

Death is a universal human experience, but how it is understood and experienced varies across different cultures. We will explore how different cultures approach death, mourning, and the afterlife, and consider the ethical implications of these differences.

Death is a complex and multifaceted topic, and it raises important questions about the nature of life, morality, and human experience. By exploring the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, we can gain a deeper understanding of these questions and how they shape our lives.

The Ripple Effect of Loss: How Death Impacts Relationships

Losing a loved one is one of the most challenging experiences one can go through in life. It is a universal experience that touches people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds. The grief that follows the death of someone close can be overwhelming and can take a significant toll on an individual's mental and physical health. However, it is not only the individual who experiences the grief but also the people around them. In this article, we will discuss the ripple effect of loss and how death impacts relationships.

Understanding Grief and Loss

Grief is the natural response to loss, and it can manifest in many different ways. The process of grieving is unique to each individual and can be affected by many factors, such as culture, religion, and personal beliefs. Grief can be intense and can impact all areas of life, including relationships, work, and physical health.

The Impact of Loss on Relationships

Death can impact relationships in many ways, and the effects can be long-lasting. Below are some of how loss can affect relationships:

1. Changes in Roles and Responsibilities

When someone dies, the roles and responsibilities within a family or social circle can shift dramatically. For example, a spouse who has lost their partner may have to take on responsibilities they never had before, such as managing finances or taking care of children. This can be a difficult adjustment, and it can put a strain on the relationship.

2. Changes in Communication

Grief can make it challenging to communicate with others effectively. Some people may withdraw and isolate themselves, while others may become angry and lash out. It is essential to understand that everyone grieves differently, and there is no right or wrong way to do it. However, these changes in communication can impact relationships, and it may take time to adjust to new ways of interacting with others.

3. Changes in Emotional Connection

When someone dies, the emotional connection between individuals can change. For example, a parent who has lost a child may find it challenging to connect with other parents who still have their children. This can lead to feelings of isolation and disconnection, and it can strain relationships.

4. Changes in Social Support

Social support is critical when dealing with grief and loss. However, it is not uncommon for people to feel unsupported during this time. Friends and family may not know what to say or do, or they may simply be too overwhelmed with their grief to offer support. This lack of social support can impact relationships and make it challenging to cope with grief.

Coping with Loss and Its Impact on Relationships

Coping with grief and loss is a long and difficult process, but it is possible to find ways to manage the impact on relationships. Below are some strategies that can help:

1. Communication

Effective communication is essential when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to talk about how you feel and what you need from others. This can help to reduce misunderstandings and make it easier to navigate changes in relationships.

2. Seek Support

It is important to seek support from friends, family, or a professional if you are struggling to cope with grief and loss. Having someone to talk to can help to alleviate feelings of isolation and provide a safe space to process emotions.

3. Self-Care

Self-care is critical when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to take care of your physical and emotional well-being. This can include things like exercise, eating well, and engaging in activities that you enjoy.

4. Allow for Flexibility

It is essential to allow for flexibility in relationships when dealing with grief and loss. People may not be able to provide the same level of support they once did or may need more support than they did before. Being open to changes in roles and responsibilities can help to reduce strain on relationships.

5. Find Meaning

Finding meaning in the loss can be a powerful way to cope with grief and loss. This can involve creating a memorial, participating in a support group, or volunteering for a cause that is meaningful to you.

The impact of loss is not limited to the individual who experiences it but extends to those around them as well. Relationships can be greatly impacted by the death of a loved one, and it is important to be aware of the changes that may occur. Coping with loss and its impact on relationships involves effective communication, seeking support, self-care, flexibility, and finding meaning.

What Lies Beyond Reflections on the Mystery of Death

Death is an inevitable part of life, and yet it remains one of the greatest mysteries that we face as humans. What happens when we die? Is there an afterlife? These are questions that have puzzled us for centuries, and they continue to do so today. In this article, we will explore the various perspectives on death and what lies beyond.

Understanding Death

Before we can delve into what lies beyond, we must first understand what death is. Death is defined as the permanent cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. This can occur as a result of illness, injury, or simply old age. Death is a natural process that occurs to all living things, but it is also a process that is often accompanied by fear and uncertainty.

The Physical Process of Death

When a person dies, their body undergoes several physical changes. The heart stops beating, and the body begins to cool and stiffen. This is known as rigor mortis, and it typically sets in within 2-6 hours after death. The body also begins to break down, and this can lead to a release of gases that cause bloating and discoloration.

The Psychological Experience of Death

In addition to the physical changes that occur during and after death, there is also a psychological experience that accompanies it. Many people report feeling a sense of detachment from their physical body, as well as a sense of peace and calm. Others report seeing bright lights or visions of loved ones who have already passed on.

Perspectives on What Lies Beyond

There are many different perspectives on what lies beyond death. Some people believe in an afterlife, while others believe in reincarnation or simply that death is the end of consciousness. Let's explore some of these perspectives in more detail.

One of the most common beliefs about what lies beyond death is the idea of an afterlife. This can take many forms, depending on one's religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, many Christians believe in heaven and hell, where people go after they die depending on their actions during life. Muslims believe in paradise and hellfire, while Hindus believe in reincarnation.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is the belief that after we die, our consciousness is reborn into a new body. This can be based on karma, meaning that the quality of one's past actions will determine the quality of their next life. Some people believe that we can choose the circumstances of our next life based on our desires and attachments in this life.

End of Consciousness

The idea that death is simply the end of consciousness is a common belief among atheists and materialists. This view holds that the brain is responsible for creating consciousness, and when the brain dies, consciousness ceases to exist. While this view may be comforting to some, others find it unsettling.

Death is a complex and mysterious phenomenon that continues to fascinate us. While we may never fully understand what lies beyond death, it's important to remember that everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives on the matter. Whether you believe in an afterlife, reincarnation, or simply the end of consciousness, it's important to find ways to cope with the loss of a loved one and to find peace with your mortality.

Final Words

In conclusion, these powerful essays on death offer inspiring perspectives and deep insights into the human experience of coping with mortality, grief, and loss. From personal accounts to philosophical reflections, these essays provide a diverse range of perspectives that encourage readers to contemplate their mortality and the meaning of life.

By reading and reflecting on these essays, readers can gain a better understanding of how death shapes our lives and relationships, and how we can learn to accept and cope with this inevitable part of the human experience.

If you're looking for a tool to help you write articles, essays, product descriptions, and more, Jenni.ai could be just what you need. With its AI-powered features, Jenni can help you write faster and more efficiently, saving you time and effort. Whether you're a student writing an essay or a professional writer crafting a blog post, Jenni's autocomplete feature, customized styles, and in-text citations can help you produce high-quality content in no time. Don't miss out on the opportunity to supercharge your next research paper or writing project – sign up for Jenni.ai today and start writing with confidence!

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

Reflections on Death in Philosophical/Existential Context

- Symposium: Reflections Before, During, and Beyond COVID-19

- Published: 27 July 2020

- Volume 57 , pages 402–409, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Nikos Kokosalakis 1

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Is death larger than life and does it annihilate life altogether? This is the basic question discussed in this essay, within a philosophical/existential context. The central argument is that the concept of death is problematic and, following Levinas, the author holds that death cannot lead to nothingness. This accords with the teaching of all religious traditions, which hold that there is life beyond death, and Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories about the immortality of the soul. In modernity, since the Enlightenment, God and religion have been placed in the margin or rejected in rational discourse. Consequently, the anthropocentric promethean view of man has been stressed and the reality of the limits placed on humans by death deemphasised or ignored. Yet, death remains at the centre of nature and human life, and its reality and threat become evident in the spread of a single virus. So, death always remains a mystery, relating to life and morality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Death, Immortality, and Meaning in Life: Precis and Further Reflections

An Attempt at Clarifying Being-Towards-Death

Death and the modern imagination.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! In form and moving, how express and admirable! In action, how like an angel! in apprehension, how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? William Shakespeare ( 1890 : 132), Hamlet, Act 2, scene 2, 303–312.

In mid-2019, the death of Sophia Kokosalakis, my niece and Goddaughter, at the age of 46, came like a thunderbolt to strike the whole family. She was a world-famous fashion designer who combined, in a unique way, the beauty and superb aesthetics of ancient and classical Greek sculptures and paintings with fashion production of clothes and jewellery. She took the aesthetics and values of ancient and classical Greek civilization out of the museums to the contemporary art of fashion design. A few months earlier she was full of life, beautiful, active, sociable and altruistic, and highly creative. All that was swept away quickly by an aggressive murderous cancer. The funeral ( κηδεία ) – a magnificent ritual event in the church of Panaghia Eleftherotria in Politeia Athens – accorded with the highly significant moving symbolism of the rite of the Orthodox Church. Her parents, her husband with their 7-year-old daughter, the wider family, relatives and friends, and hundreds of people were present, as well as eminent representatives of the arts. The Greek Prime Minister and other dignitaries sent wreaths and messages of condolences, and flowers were sent from around the world. After the burial in the family grave in the cemetery of Chalandri, some gathered for a memorial meal. This was a high profile, emotional final goodbye to a beloved famous person for her last irreversible Journey.

Sophia’s death was circumscribed by social and religious rituals that help to chart a path through the transition from life to death. Yet, the pain and sorrow for Sophia’s family has been very deep. For her parents, especially, it has been indescribable, indeed, unbearable. The existential reality of death is something different. It raises philosophical questions about what death really means in a human existential context. How do humans cope with it? What light do religious explanations of death shed on the existential experience of death and what do philosophical traditions have to say on this matter?

In broad terms religions see human life as larger than death, so that life’s substance meaning and values for each person are not exhausted with biological termination. Life goes on. For most religions and cultures there is some notion of immortality of the soul and there is highly significant ritual and symbolism for the dead, in all cultures, that relates to their memory and offers some notion of life beyond the grave. In Christianity, for example, life beyond death and the eternity and salvation of the soul constitutes the core of its teaching, immediately related to the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ. Theologically, Christ’s death and resurrection, declare the defeat of death by the death and the resurrection of the son of God, who was, both, God and perfectly human (theanthropos). This teaching signifies the triumph of life over death, which also means, eschatologically, the salvation and liberation of humankind from evil and the injustice and imperfection of the world. It refers to another dimension beyond the human condition, a paradisiac state beyond the time/space configuration, a state of immortality, eternity and infinity; it points to the sublimation of nature itself. So, according to Christian faith, the death of a human being is a painful boundary of transition, and there is hope that human life is not perishable at death. There is a paradox here that through death one enters real life in union with God. But this is not knowledge. It is faith and must be understood theologically and eschatologically.

While the deeply faithful, may accept and understand death as passage to their union with God, Sophia’s death shows that, for ordinary people, the fear of death and the desperation caused by the permanent absence of a beloved person is hard to bear – even with the help of strong religious faith. For those with lukewarm religious faith or no faith at all, religious discourse and ritual seems irrelevant or even annoying and irrational. However, nobody escapes the reality of death. It is at the heart of nature and the human condition and it is deeply ingrained in the consciousness of adult human beings. Indeed, of all animals it is only humans who know that they will die and according to Heidegger ( 1967 :274) “death is something distinctively impending”. The fear of death, consciously or subconsciously, is instilled in humans early in life and, as the ancients said, when death is near no one wants to die. ( Ην εγγύς έλθει θάνατος ουδείς βούλεται θνήσκειν. [Aesopus Fables]). In Christianity even Christ, the son of God, prayed to his father to remove the bitter cup of death before his crucifixion (Math. 26, 38–39; Luke, 22, 41–42).

The natural sciences say nothing much about the existential content and conditions of human death beyond the biological laws of human existence and human evolution. According to these laws, all forms of life have a beginning a duration and an end. In any case, from a philosophical point of view, it is considered a category mistake, i.e. epistemologically and methodologically wrong, to apply purely naturalistic categories and quantitative experimental methods for the study, explanation and interpretation of human social phenomena, especially cultural phenomena such as the meaning of human death and religion at large. As no enlightenment on such issues emerges from the natural sciences, maybe insights can be teased out from philosophical anthropological thinking.

Philosophical anthropology is concerned with questions of human nature and life and death in deeper intellectual, philosophical, dramaturgical context. Religion and the sacred are inevitably involved in such discourse. For example, the verses from Shakespeare’s Hamlet about the nature of man, at the preamble of this essay, put the matter in a nutshell. What is this being who acts like an angel, apprehends and creates like a god, and yet, it is limited as the quintessence of dust? It is within this discourse that I seek to draw insights concerning human death. I will argue that, although in formal logical/scientific terms, we do not know and cannot know anything about life after/beyond death, there is, and always has been, a legitimate philosophical discourse about being and the dialectic of life/death. We cannot prove or disprove the existence and content of life beyond death in scientific or logical terms any more than we can prove or disprove the existence of God scientifically. Footnote 1

Such discourse inevitably takes place within the framework of transcendence, and transcendence is present within life and beyond death. Indeed, transcendence is at the core of human consciousness as humans are the only beings (species) who have culture that transcends their biological organism. Footnote 2 According to Martin ( 1980 :4) “the main issue is… man’s ability to transcend and transform his situation”. So human death can be described and understood as a cultural fact immediately related to transcendence, and as a limit to human transcendental ability and potential. But it is important, from an epistemological methodological point of view, not to preconceive this fact in reductionist positivistic or closed ideological terms. It is essential that the discourse about death takes place within an open dialectic, not excluding transcendence and God a priori, stressing the value of life, and understanding the limits of the human potential.

The Problem of Meaning in Human Death

Biologically and medically the meaning and reality of human death, as that of all animals, is clear: the cessation of all the functions and faculties of the organs of the body, especially the heart and the brain. This entails, of course, the cessation of consciousness. Yet, this definition tells us nothing about why only the human species, latecomers in the universe, have always worshiped their gods, buried their dead with elaborate ritual, and held various beliefs about immortality. Harari ( 2017 :428–439) claims that, in the not too distant future, sapiens could aim at, and is likely to achieve, immortality and the status of Homo Deus through biotechnology, information science, artificial intelligence and what he calls the data religion . I shall leave aside what I consider farfetched utopian fictional futurology and reflect a little on the problem of meaning of human death and immortality philosophically.

We are not dealing here with the complex question of biological life. This is the purview of the science of biology and biotechnology within the laws of nature. Rather, we are within the framework of human existence, consciousness and transcendence and the question of being and time in a philosophical sense. According to Heidegger ( 1967 :290) “Death, in the widest sense, is a phenomenon of life. Life must be understood as a kind of Being to which there belongs a Being-in-the-world”. He also argues (bid: 291) that: “The existential interpretation of death takes precedence over any biology and ontology of life. But it is also the foundation for any investigation of death which is biographical or historiological, ethnological or psychological”. So, the focus is sharply on the issue of life/death in the specifically human existential context of being/life/death . Human life is an (the) ultimate value, (people everywhere raise their glass to life and good health), and in the midst of it there is death as an ultimate threatening eliminating force. But is death larger than life, and can death eliminate life altogether? That’s the question. Whereas all beings from plants to animals, including man, are born live and die, in the case of human persons this cycle carries with it deep and wide meaning embodied within specific empirical, historical, cultural phenomena. In this context death, like birth and marriage, is a carrier of specific cultural significance and deeper meaning. It has always been accompanied by what anthropologists refer to as rites of passage, (Van Gennep, 1960 [1909]; Turner, 1967; Garces-Foley, 2006 ). These refer to transition events from one state of life to another. All such acts and rites, and religion generally, should be understood analysed and interpreted within the framework of symbolic language. (Kokosalakis, 2001 , 2020 ). In this sense the meaning of death is open and we get a glimpse of it through symbols.

Death, thus, is an existential tragic/dramatic phenomenon, which has preoccupied philosophy and the arts from the beginning and has been always treated as problematic. According to Heidegger ( 1967 : 295), the human being Dasein (being-there) has not explicit or even theoretical knowledge of death, hence the anxiety in the face of it. Also, Dasein has its death, “not in isolation, but as codetermined by its primordial kind of Being” (ibid: 291). He further argues that in the context of being/time/death, death is understood as being-towards-death ( Sein zum Tode ). Levinas Footnote 3 ( 2000 :8), although indebted to Heidegger, disagrees radically with him on this point because it posits being-towards death ( Sein zum Tode) “as equivalent to being in regard to nothingness”. Leaving aside that, phenomenologically the concept of nothingness itself is problematic (Sartre: 3–67), Levinas ( 2000 :8) asks: “is that which opens with death nothingness or the unknown? Can being at the point of death be reduced to the ontological dilemma of being or nothingness? That is the question that is posed here.” In other words, Levinas considers this issue problematic and wants to keep the question of being/life/death open. Logically and philosophically the concept of nothingness is absolute, definitive and closed whereas the concept of the unknown is open and problematic. In any case both concepts are ultimately based on belief, but nothingness implies knowledge which we cannot have in the context of death.

Levinas (ibid: 8–9) argues that any knowledge we have of death comes to us “second hand” and that “It is in relation with the other that we think of death in its negativity” (emphasis mine). Indeed, the ultimate objective of hate is the death of the other , the annihilation of the hated person. Also death “[is] a departure: it is a decease [deces]”. It is a permanent separation of them from us which is felt and experienced foremost and deeply for the departure of the beloved. This is because death is “A departure towards the unknown, a departure without return, a departure with no forward address”. Thus, the emotion and the sorrow associated with it and the pain and sadness caused to those remaining. Deep-down, existentially and philosophically, death is a mystery. It involves “an ambiguity that perhaps indicates another dimension of meaning than that in which death is thought within the alternative to be/not- to- be. The ambiguity: an enigma” (ibid: 14). Although, as Heidegger ( 1967 :298–311) argues, death is the only absolute certainty we have and it is the origin of certitude itself, I agree with Levinas (ibid: 10–27) that this certitude cannot be forthcoming from the experience of our own death alone, which is impossible anyway. Death entails the cessation of the consciousness of the subject and without consciousness there is no experience. We experience the process of our dying but not our own death itself. So, our experience of death is primarily that of the death of others. It is our observation of the cessation of the movement, of the life of the other .

Furthermore, Levinas (Ibid: 10–13) argues that “it is not certain that death has the meaning of annihilation” because if death is understood as annihilation in time, “Here, we are looking for other dimension of meaning, both for the meaning of time Footnote 4 and for the meaning of death”. Footnote 5 So death is a phenomenon with dimensions of meaning beyond the historical space/time configuration. Levinas dealt with such dimensions extensively not only in his God, Death and Time (2000) but also in his: Totality and Infinity (1969); Otherwise than Being, or Beyond Essence (1991); and, Of God Who comes to mind (1998). So, existentially/phenomenologically such dimensions inevitably involve the concept of transcendence, the divine, and some kind of faith. Indeed, the question of human death has always involved the question of the soul. Humans have been generally understood to be composite beings of body/soul or spirit and the latter has also been associated with transcendence and the divine. In general the body has been understood and experienced as perishable with death, whereas the soul/spirit has been understood (believed) to be indestructible. Thus beyond or surviving after/beyond death. Certainly this has been the assumption and general belief of major religions and cultures, Footnote 6 and philosophy itself, until modernity and up to the eighteenth century.

Ancient and classical Greek philosophy preoccupied itself with the question of the soul. Footnote 7 Homer, both in the Iliad and the Odyssey, has several reference on the soul in hades (the underworld) and Pythagoras of Samos (580–496 b.c.) dealt with immortality and metempsychosis (reincarnation). Footnote 8 In all the tragedies by Sophocles (496–406 b,c,), Aeschylus (523–456 b. c.), and Euripides (480–406 b.c.), death is a central theme but it was Plato Footnote 9 (428?-347 b.c.) and Aristotle Footnote 10 (384–322 b.c.) – widely acknowledged as the greatest philosophers of all times – who wrote specific treatises on the soul. Let us look at their positions very briefly.

Plato on the Soul

Plato was deeply concerned with the nature of the soul and the problem of immortality because such questions were foundational to his theory of the forms (ideas), his understanding of ethics, and his philosophy at large. So, apart from the dialogue Phaedo , in which the soul and its immortality is the central subject, he also referred to it extensively in the Republic , the Symposium and the Apology as well in the dialogues: Timaeus , Gorgias, Phaedrus, Crito, Euthyfron and Laches .

The dialogue Phaedo Footnote 11 is a discussion on the soul and immortality between Socrates (470–399 b.c.) and his interlocutors Cebes and Simias. They were Pythagorians from Thebes, who went to see Socrates in prison just before he was about to be given the hemlock (the liquid poison: means by which the death penalty was carried out at the time in Athens). Phaedo, his disciple, who was also present, is the narrator. The visitors found Socrates very serene and in pleasant mood and wondered how he did not seem to be afraid of death just before his execution. Upon this Socrates replies that it would be unreasonable to be afraid of death since he was about to join company with the Gods (of which he was certain) and, perhaps, with good and beloved departed persons. In any case, he argued, the true philosopher cannot be afraid of death as his whole life, indeed, is a practice and a preparation for it. So for this, and other philosophical reasons, death for Socrates is not to be feared. ( Phaedo; 64a–68b).

Socrates defines death as the separation of the soul from the body (64c), which he describes as prison of the former while joined in life. The body, which is material and prone to earthly materialistic pleasures, is an obstacle for the soul to pursue and acquire true knowledge, virtue, moderation and higher spiritual achievements generally (64d–66e). So, for the true philosopher, whose raison-d’être is to pursue knowledge truth and virtue, the liberation of the soul from bodily things, and death itself when it comes, is welcome because life, for him, was a training for death anyway. For these reasons, Socrates says is “glad to go to hades ” (the underworld) (68b).

Following various questions of Cebes and Simias about the soul, and its surviving death, Socrates proceeds to provide some logical philosophical arguments for its immortality. The main ones only can be mentioned here. In the so called cyclical argument, Socrates holds that the immortality of the soul follows logically from the relation of opposites (binaries) and comparatives: Big, small; good, bad; just, unjust; beautiful, ugly; good, better; bad; worse, etc. As these imply each other so life/death/life are mutually inter-connected, (70e–71d). The second main argument is that of recollection. Socrates holds that learning, in general, is recollection of things and ideas by the soul which always existed and the soul itself pre-existed before it took the human shape. (73a–77a). Socrates also advises Cebes and Simias to look into themselves, into their own psych e and their own consciousness in order to understand what makes them alive and makes them speak and move, and that is proof for the immortality of the soul (78ab). These arguments are disputed and are considered inadequate and anachronistic by many philosophers today (Steadman, 2015 ; Shagulta and Hammad, 2018 ; and others) but the importance of Phaedo lies in the theory of ideas and values and the concept of ethics imbedded in it.

Plato’s theory of forms (ideas) is the basis of philosophical idealism to the present day and also poses the question of the human autonomy and free will. Phaedo attracts the attention of modern and contemporary philosophers from Kant (1724–1804) and Hegel (1770–1831) onwards, because it poses the existential problems of life, death, the soul, consciousness, movement and causality as well as morality, which have preoccupied philosophy and the human sciences diachronically. In this dialogue a central issue is the philosophy of ethics and values at large as related to the problem of death. Aristotle, who was critical of Plato’s idealism, also uses the concept of forms and poses the question of the soul as a substantive first principle of life and movement although he does not deal with death and immortality as Plato does.

Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle’s conception of the soul is close to contemporary biology and psychology because his whole philosophy is near to modern science. Unlike many scholars, however, who tend to be reductionist, limiting the soul to naturalistic/positivistic explanations, (as Isherwood, 2016 , for instance, does, unlike Charlier, 2018 , who finds relevance in religious and metaphysical connections), Aristotle’s treatment of it, as an essential irreducible principle of life, leaves room for its metaphysical substance and character. So his treatise on the soul , (known now to scholars as De Anima, Shields, 2016 ), is closely related to both his physics and his metaphysics.

Aristotle sees all living beings (plants, animals, humans) as composite and indivisible of body, soul or form (Charlton, 1980 ). The body is material and the soul is immaterial but none can be expressed, comprehended or perceived apart from matter ( ύλη ). Shields ( 2016 ) has described this understanding and use of the concepts of matter and form in Aristotle’s philosophy as hylomorphism [ hyle and morphe, (matter and form)]. The soul ( psyche ) is a principle, arche (αρχή) associated with cause (αιτία) and motion ( kinesis ) but it is inseparable from matter. In plants its basic function and characteristic is nutrition. In animals, in addition to nutrition it has the function and characteristic of sensing. In humans apart from nutrition and sensing, which they share with all animals, in addition it has the unique faculty of noesis and logos. ( De Anima ch. 2). Following this, Heidegger ( 1967 :47) sees humans as: “Dasein, man’s Being is ‘defined’ as the ζωον λόγον έχον – as that living thing whose Being is essentially determined by the potentiality for discourse”. (So, only human beings talk, other beings do not and cannot).

In Chapter Five, Aristotle concentrates on this unique property of the human soul, the logos or nous, known in English as mind . The nous (mind) is both: passive and active. The former, the passive mind, although necessary for noesis and knowledge, is perishable and mortal (φθαρτός). The latter, the poetic mind is higher, it is a principle of causality and creativity, it is energy, aitia . So this, the poetic the creative mind is higher. It is the most important property of the soul and it is immaterial, immortal and eternal. Here Aristotle considers the poetic mind as separate from organic life, as substance entering the human body from outside, as it were. Noetic mind is the divine property in humans and expresses itself in their pursuit to imitate the prime mover, God that is.

So, Aristotle arrives here at the problem of immortality of the soul by another root than Plato but, unlike him, he does not elaborate on the metaphysics of this question beyond the properties of the poetic mind and he focuses on life in the world. King ( 2001 :214) argues that Aristotle is not so much concerned to establish the immortality of the human individual as that of the human species as an eidos. Here, however, I would like to stress that we should not confuse Aristotle’s understanding with contemporary biological theories about the dominance and survival of the human species. But whatever the case may be, both Aristotle’s and Plato’s treatises on the soul continue to be inspiring sources of debate by philosophers and others on these issues to the present day.

Death in Modernity

By modernity here is meant the general changes which occurred in western society and culture with the growth of science and technology and the economy, especially after the Enlightenment, and the French and the Industrial Revolutions, which have their cultural roots in the Renaissance, the Reformation and Protestantism.

It is banal to say that life beyond death does not preoccupy people in modernity as it did before and that, perhaps, now most people do not believe in the immortality of the soul. In what Charles Taylor ( 2007 ) has extensively described as A SECULAR AGE he frames the question of change in religious beliefs in the west as follows: “why was it virtually impossible not to believe in God in, say, 1500 in our western society, while in 2000 many of us find this not only easy, but even inescapable?” (p. 25). The answer to this question is loaded with controversy and is given variously by different scholars. Footnote 13 Taylor (ibid: 65–75, 720–726) shows how and why beliefs have changed radically in modernity. Metaphysical transcendent beliefs on life and death have shrunk into this-worldly secular conceptions in what he calls, “the immanent frame”. As a consequence, transcendence and the sacred were exiled from the world or reduced to “closed world structures”. Footnote 14 In this context many scholars spoke of “the death of God” (ibid: 564–575).

In criticizing postmodern relativism, which brings various vague conceptions of God and transcendence back in play, Gellner ( 1992 :80–83) praises what he calls Enlightenment Rationalist fundamentalism, which “at one fell swoop eliminates the sacred from the world”. Although he acknowledges that Kant, the deepest thinker of the Enlightenment, left morality reason and knowledge outside the purview of the laws of nature, thus leaving the question of transcendence open, he still claims that Enlightenment rationalism is the only positive scientific way to study religious phenomena and death rituals. This position seems to be epistemologically flawed, because it pre-empts what concerns us here, namely, the assumptions of modernity for the nature of man and its implications for the meaning and reality of death.

In rejecting religion and traditional conceptions of death, Enlightenment rationalism put forward an overoptimistic, promethean view of man. What Vereker ( 1967 ) described as the “God of Reason” was the foundation of eighteenth century optimism. The idea was that enlightened rationalism, based on the benevolent orderly laws of nature, would bring about the redeemed society. Enlightened, rational leaders and the gradual disappearance of traditional religious beliefs, obscurantism and superstitions, which were sustained by the ancient regime, would eventually transform society and would abolish all human evil and social and political injustice. Science was supportive of this view because it showed that natural and social phenomena, traditionally attributed to divine agencies and metaphysical forces, have a clear natural causation. These ideas, developed by European philosophers (Voltaire 1694–1778; Rousseau, 1712–1778; Kant, 1724–1804; Hume, 1711–1776; and many others), were foundational to social and political reform, and the basis of the French Revolution (1789–1799). However, the underlying optimism of such philosophical ideas about the benevolence of nature appeared incompatible with natural phenomena such as the great earthquake in Lisbon in 1755, which flattened the city and killed over 100,000 people. Enlightenment rationalism overemphasised a promethean, anthropocentric view of man without God, and ignored the limits of man and the moral and existential significance of death.

In his critique of capitalism, in the nineteenth century, Marx (1818–1883), promoted further the promethean view of man by elevating him as the author of his destiny and banishing God and religion as “the opium of the people”. In his O rigin of the Species (1859), Charles Darwin also showed man’s biological connections with primates, thereby challenging biblical texts about the specific divine origin of the human species. He confirmed human dominance in nature. Important figures in literature, however, such as Dostoevsky (1821–1881) and Tolstoy (1828–1910), pointed out and criticised the conceit and arrogance of an inflated humanism without God, promoted by the promethean man of modernity.

By the end of the twentieth century the triumph of science, biotechnology, information technology, and international capitalist monetary economics, all of them consequences of modernity, had turned the planet into a global village with improved living standards for the majority. Medical science also has doubled average life expectancy from what it was in nineteenth century and information technology has made, almost every adult, owner of a mobile smart phone. Moreover, visiting the moon has inflated man’s sense of mastery over nature, and all these achievements, although embodying Taylor’s ( 1992 ) malaise of modernity at the expense of the environment, have strengthen the promethean view and, somehow, ignored human limits. As a consequence, the reality of death was treated as a kind of taboo, tucked under the carpet.

This seems a paradox because, apart from the normal death of individuals, massive collective deaths, caused by nature and by hate and barbarity from man to man, were present in the twentieth century more than any other in history. The pandemic of Spanish flue 1917–1919 killed 39 million of the world’s population according to estimates by Baro et al. (2020). In the First World War deaths, military and civilians combined, were estimated at 20.5 million (Wikipedia). In the Second World War an estimated total of 70–85 million people perished, (Wikipedia). This did not include estimates of more than seven million people who died in the gulags of Siberia and elsewhere under Stalin. But Auschwitz is indicative of the unlimited limits, which human barbarity and cruelty of man to man, can reach. Bauman ( 1989 :x), an eminent sociologist, saw the Holocaust as a moral horror related to modernity and wrote: “ The Holocaust was born and executed in modern rational society, at the high stage of our civilization and at the peak of human cultural achievement, and for this reason it is a problem of that society, civilization and culture. ”

Questions associated with the mass death are now magnified by the spread of the coronavirus (Covid-19). This has caused global panic and created unpredictability at all levels of society and culture. This sudden global threat of death makes it timely to re-examine our values, our beliefs (secular or religious), and the meaning of life. Max Weber (1948: 182), who died a hundred years ago in the pandemic of great influenza, was sceptical and pessimistic about modernity, and argued that it was leading to a cage with “ specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it had attained a level of civilization never before achieved. ”

So, what does this examination of philosophical anthropology illuminate in terms of questions of human nature and life and death in deeper intellectual, philosophical, dramaturgical context? Now, we are well into the twenty-first century, and with the revolution in information science, the internet, biotechnology and data religion , the promethean view of man seems to have reached new heights. Yet, massive death, by a single virus this time, threatens again humanity; are there any lessons to be learned? Will this threat, apart from the negativity of death, bring back the wisdom, which T. S. Elliot said we have lost in modern times? Will it show us our limits? Will it reduce our conceit and arrogance? Will it make us more humble, moderate, prudent, and more humane for this and future generations, and for the sake of life in this planet at large? These are the questions arising now amongst many circles, and it is likely that old religious and philosophical ideas about virtuous life and the hope of immortality (eschatologically) may revive again as we are well within late modernity (I do not like the term postmodernity, which has been widely used in sociology since the 1980s).

The central argument of this essay has been that death has always been and remains at the centre of life. Philosophically and existentially the meaning of death is problematic, and the natural sciences cannot produce knowledge on this problem. Religious traditions always beheld the immortality of the soul and so argued great philosophers like Plato and Aristotle. Modernity, since the Enlightenment, rejected such views as anachronistic and advanced an anthropocentric promethean, view of man, at the expense of the sacred and transcendence at large. Instead, within what Taylor (1967: 537–193) has described as the immanent frame, it developed “closed world structures,” which are at the expense of human nature and human freedom. One consequence of this has been massive death during the twentieth century.

Following Levinas ( 2000 ), I argued that death should not be understood to lead to nothingness because nothingness means certitude and positive knowledge, which we cannot have existentially in the case of death. In this sense the reality of death should not be understood to lead to annihilation of life and remains a mystery. Moreover, the presence and the reality of death as a limit and a boundary should serve as educative lesson for both the autonomy and creativity of man and against an overinflated promethean view of her/his nature.