Gender-Based Violence (Violence Against Women and Girls)

Photo: Simone D. McCourtie / World Bank

Gender-based violence (GBV) or violence against women and girls (VAWG), is a global pandemic that affects 1 in 3 women in their lifetime.

The numbers are staggering:

- 35% of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence.

- Globally, 7% of women have been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner.

- Globally, as many as 38% of murders of women are committed by an intimate partner.

- 200 million women have experienced female genital mutilation/cutting.

This issue is not only devastating for survivors of violence and their families, but also entails significant social and economic costs. In some countries, violence against women is estimated to cost countries up to 3.7% of their GDP – more than double what most governments spend on education.

Failure to address this issue also entails a significant cost for the future. Numerous studies have shown that children growing up with violence are more likely to become survivors themselves or perpetrators of violence in the future.

One characteristic of gender-based violence is that it knows no social or economic boundaries and affects women and girls of all socio-economic backgrounds: this issue needs to be addressed in both developing and developed countries.

Decreasing violence against women and girls requires a community-based, multi-pronged approach, and sustained engagement with multiple stakeholders. The most effective initiatives address underlying risk factors for violence, including social norms regarding gender roles and the acceptability of violence.

The World Bank is committed to addressing gender-based violence through investment, research and learning, and collaboration with stakeholders around the world.

Since 2003, the World Bank has engaged with countries and partners to support projects and knowledge products aimed at preventing and addressing GBV. The Bank supports over $300 million in development projects aimed at addressing GBV in World Bank Group (WBG)-financed operations, both through standalone projects and through the integration of GBV components in sector-specific projects in areas such as transport, education, social protection, and forced displacement. Recognizing the significance of the challenge, addressing GBV in operations has been highlighted as a World Bank priority, with key commitments articulated under both IDA 17 and 18, as well as within the World Bank Group Gender Strategy .

The World Bank conducts analytical work —including rigorous impact evaluation—with partners on gender-based violence to generate lessons on effective prevention and response interventions at the community and national levels.

The World Bank regularly convenes a wide range of development stakeholders to share knowledge and build evidence on what works to address violence against women and girls.

Over the last few years, the World Bank has ramped up its efforts to address more effectively GBV risks in its operations , including learning from other institutions.

Addressing GBV is a significant, long-term development challenge. Recognizing the scale of the challenge, the World Bank’s operational and analytical work has expanded substantially in recent years. The Bank’s engagement is building on global partnerships, learning, and best practices to test and advance effective approaches both to prevent GBV—including interventions to address the social norms and behaviors that underpin violence—and to scale up and improve response when violence occurs.

World Bank-supported initiatives are important steps on a rapidly evolving journey to bring successful interventions to scale, build government and local capacity, and to contribute to the knowledge base of what works and what doesn’t through continuous monitoring and evaluation.

Addressing the complex development challenge of gender-based violence requires significant learning and knowledge sharing through partnerships and long-term programs. The World Bank is committed to working with countries and partners to prevent and address GBV in its projects.

Knowledge sharing and learning

Violence against Women and Girls: Lessons from South Asia is the first report of its kind to gather all available data and information on GBV in the region. In partnership with research institutions and other development organizations, the World Bank has also compiled a comprehensive review of the global evidence for effective interventions to prevent or reduce violence against women and girls. These lessons are now informing our work in several sectors, and are captured in sector-specific resources in the VAWG Resource Guide: www.vawgresourceguide.org .

The World Bank’s Global Platform on Addressing GBV in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings facilitated South-South knowledge sharing through workshops and yearly learning tours, building evidence on what works to prevent GBV, and providing quality services to women, men, and child survivors. The Platform included a $13 million cross-regional and cross-practice initiative, establishing pilot projects in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Nepal, Papua New Guinea, and Georgia, focused on GBV prevention and mitigation, as well as knowledge and learning activities.

The World Bank regularly convenes a wide range of development stakeholders to address violence against women and girls. For example, former WBG President Jim Yong Kim committed to an annual Development Marketplace competition, together with the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) , to encourage researchers from around the world to build the evidence base of what works to prevent GBV. In April 2019, the World Bank awarded $1.1 million to 11 research teams from nine countries as a result of the fourth annual competition.

Addressing GBV in World Bank Group-financed operations

The World Bank supports both standalone GBV operations, as well as the integration of GBV interventions into development projects across key sectors.

Standalone GBV operations include:

- In August 2018, the World Bank committed $100 million to help prevent GBV in the DRC . The Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Project will reach 795,000 direct beneficiaries over the course of four years. The project will provide help to survivors of GBV, and aim to shift social norms by promoting gender equality and behavioral change through strong partnerships with civil society organizations.

- In the Great Lakes Emergency Sexual and Gender Based Violence & Women's Health Project , the World Bank approved $107 million in financial grants to Burundi, the DRC, and Rwanda to provide integrated health and counseling services, legal aid, and economic opportunities to survivors of – or those affected by – sexual and gender-based violence. In DRC alone, 40,000 people, including 29,000 women, have received these services and support.

- The World Bank is also piloting innovative uses of social media to change behaviors . For example, in the South Asia region, the pilot program WEvolve used social media to empower young women and men to challenge and break through prevailing norms that underpin gender violence.

Learning from the Uganda Transport Sector Development Project and following the Global GBV Task Force’s recommendations , the World Bank has developed and launched a rigorous approach to addressing GBV risks in infrastructure operations:

- Guided by the GBV Good Practice Note launched in October 2018, the Bank is applying new standards in GBV risk identification, mitigation and response to all new operations in sustainable development and infrastructure sectors.

- These standards are also being integrated into active operations; GBV risk management approaches are being applied to a selection of operations identified high risk in fiscal year (FY) 2019.

- In the East Asia and Pacific region , GBV prevention and response interventions – including a code of conduct on sexual exploitation and abuse – are embedded within the Vanuatu Aviation Investment Project .

- The Liberia Southeastern Corridor Road Asset Management Project , where sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) awareness will be raised, among other strategies, as part of a pilot project to employ women in the use of heavy machinery.

- The Bolivia Santa Cruz Road Corridor Project uses a three-pronged approach to address potential GBV, including a Code of Conduct for their workers; a Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM) that includes a specific mandate to address any kinds gender-based violence; and concrete measures to empower women and to bolster their economic resilience by helping them learn new skills, improve the production and commercialization of traditional arts and crafts, and access more investment opportunities.

- The Mozambique Integrated Feeder Road Development Project identified SEA as a substantial risk during project preparation and takes a preemptive approach: a Code of Conduct; support to – and guidance for – the survivors in case any instances of SEA were to occur within the context of the project – establishing a “survivor-centered approach” that creates multiple entry points for anyone experiencing SEA to seek the help they need; and these measures are taken in close coordination with local community organizations, and an international NGO Jhpiego, which has extensive experience working in Mozambique.

Strengthening institutional efforts to address GBV

In October 2016, the World Bank launched the Global Gender-Based Violence Task Force to strengthen the institution’s efforts to prevent and respond to risks of GBV, and particularly sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) that may arise in World Bank-supported projects. It builds on existing work by the World Bank and other actors to tackle violence against women and girls through strengthened approaches to identifying and assessing key risks, and developing key mitigations measures to prevent and respond to sexual exploitation and abuse and other forms of GBV.

In line with its commitments under IDA 18 , the World Bank developed an Action Plan for Implementation of the Task Force’s recommendations , consolidating key actions across institutional priorities linked to enhancing social risk management, strengthening operational systems to enhance accountability, and building staff and client capacity to address risks of GBV through training and guidance materials.

As part of implementation of the GBV Task Force recommendations, the World Bank has developed a GBV risk assessment tool and rigorous methodology to assess contextual and project-related risks. The tool is used by any project containing civil works.

The World Bank has developed a Good Practice Note (GPN) with recommendations to assist staff in identifying risks of GBV, particularly sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment that can emerge in investment projects with major civil works contracts. Building on World Bank experience and good international industry practices, the note also advises staff on how to best manage such risks. A similar toolkit and resource note for Borrowers is under development, and the Bank is in the process of adapting the GPN for key sectors in human development.

The GPN provides good practice for staff on addressing GBV risks and impacts in the context of the Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) launched on October 1, 2018, including the following ESF standards, as well as the safeguards policies that pre-date the ESF:

- ESS 1: Assessment and Management of Environmental and Social Risks and Impacts;

- ESS 2: Labor and Working Conditions;

- ESS 4: Community Health and Safety; and

- ESS 10: Stakeholder Engagement and Information Disclosure.

In addition to the Good Practice Note and GBV Risk Assessment Screening Tool, which enable improved GBV risk identification and management, the Bank has made important changes in its operational processes, including the integration of SEA/GBV provisions into its safeguard and procurement requirements as part of evolving Environmental, Social, Health and Safety (ESHS) standards, elaboration of GBV reporting and response measures in the Environmental and Social Incident Reporting Tool, and development of guidance on addressing GBV cases in our grievance redress mechanisms.

In line with recommendations by the Task Force to disseminate lessons learned from past projects, and to sensitize staff on the importance of addressing risks of GBV and SEA, the World Bank has developed of trainings for Bank staff to raise awareness of GBV risks and to familiarize staff with new GBV measures and requirements. These trainings are further complemented by ongoing learning events and intensive sessions of GBV risk management.

Last Updated: Sep 25, 2019

- FEATURE STORY To End Poverty You Have to Eliminate Violence Against Women and Girls

- TOOLKIT Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) Resource Guide

DRC, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, and Rwanda Join Forces to Fight Sexual and Gender-...

More than one in three women worldwide have experienced sexual and gender-based violence during their lifetime. In contexts of fragility and conflict, sexual violence is often exacerbated.

Supporting Women Survivors of Violence in Africa's Great Lakes Region

The Great Lakes Emergency SGBV and Women’s Health Project is the first World Bank project in Africa with a major focus on offering integrated services to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

To End Poverty, Eliminate Gender-Based Violence

Intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence are economic consequences that contribute to ongoing poverty. Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez, Senior Director at the World Bank, explains the role that social norms play in ...

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C59 - Other

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F19 - Other

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F66 - Labor

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H27 - Other Sources of Revenue

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H61 - Budget; Budget Systems

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L97 - Utilities: General

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M53 - Training

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N77 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P14 - Property Rights

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P43 - Public Economics; Financial Economics

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q25 - Water

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- Browse content in Y - Miscellaneous Categories

- Y8 - Related Disciplines

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About The World Bank Research Observer

- About the World Bank

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Addressing Gender-Based Violence: A Critical Review of Interventions

Andrew Morrison (corresponding author) is a lead economist in the Gender and Development Group at the World Bank; his email address is [email protected] .

Mary Ellsberg is senior advisor for Gender, Violence, and Human Rights at PATH; her email address is [email protected] .

Sarah Bott is an independent consultant; her email address is [email protected] .

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Andrew Morrison, Mary Ellsberg, Sarah Bott, Addressing Gender-Based Violence: A Critical Review of Interventions, The World Bank Research Observer , Volume 22, Issue 1, Spring 2007, Pages 25–51, https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkm003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article highlights the progress in building a knowledge base on effective ways to increase access to justice for women who have experienced gender-based violence, offer quality services to survivors, and reduce levels of gender-based violence. While recognizing the limited number of high-quality studies on program effectiveness, this review of the literature highlights emerging good practices. Much progress has recently been made in measuring gender-based violence, most notably through a World Health Organization multicountry study and Demographic and Health Surveys. Even so, country coverage is still limited, and much of the information from other data sources cannot be meaningfully compared because of differences in how intimate partner violence is measured and reported. The dearth of high-quality evaluations means that policy recommendations in the short run must be based on emerging evidence in developing economies (process evaluations, qualitative evaluations, and imperfectly designed impact evaluations) and on more rigorous impact evaluations from developed countries.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1564-6971

- Print ISSN 0257-3032

- Copyright © 2024 World Bank

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Engaging in Gender-Based Violence Research: Adopting a Feminist and Participatory Perspective

- First Online: 18 February 2021

Cite this chapter

- Sanne Weber 3 &

- Siân Thomas 3

2 Citations

Researching gender-based violence involves different challenges for both participants and researchers, including risks to their mental well-being and physical safety. The possibilities of such research having adverse effects for participants are often stronger in cross-cultural research, since researchers are not always well aware of the locally and culturally specific sensitivities in relation to the issue of gender-based violence. The unequal power relations between researcher and participants, which can exist in all settings, may be exacerbated in contexts of cultural difference. To mitigate these risks and instead attempt to make research a beneficial or even transformative experience for participants, researchers can consider adopting feminist and participatory approaches. After explaining in more detail the risks of gender-based violence research, this chapter describes how feminist and participatory research methods respond to these risks, highlighting particularly the scope for creative approaches to such research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

True J. The political economy of violence against women. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Book Google Scholar

Thomas SN, Weber S, Bradbury-Jones C. Using participatory and creative methods to research gender-based violence in the global south and with indigenous communities: findings from a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020.

Google Scholar

Taylor J, Bradbury-Jones C. Sensitive issues in healthcare research: the protection paradox. J Res Nurs. 2011;16(4):303–6.

Article Google Scholar

Malpass A, Sales K, Feder G. Reducing symbolic violence in the research encounter: collaborating with a survivor of domestic abuse in a qualitative study in UK primary care. Sociol Health Illn. 2016;38(3):442–58.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ponic P, Jategaonkar N. Balancing safety and action: ethical protocols for photovoice research with women who have experienced violence. Arts Health. 2012;4(3):189–202.

Adams V. Metrics: what counts in global health. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2016.

Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(1):1–16.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Merry SE. The seductions of quantification: measuring human rights, gender violence, and sex trafficking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2016.

Ryan L, Golden A. “Tick the box please”: a reflexive approach to doing quantitative social research. Sociology. 2006;40(6):1191–200.

Alhabib S, Nur U, Jones R. Domestic violence against women: systematic review of prevalence studies. J Fam Violence. 2009;25(4):369–82.

Hughes C, Cohen RL. Feminists really do count: the complexity of feminist methodologies. Soc Res Method. 2010;13(3):189–96.

Ellsberg M, Heise L. Researching violence against women: a practical guide for researchers and activists. Washington, DC: World Health Organisation/PATH; 2005.

Hyden M. Narrating sensitive topics. In: Andrews M, Squire C, Tamboukou M, editors. Doing narrative research. London: Sage; 2008. p. 121–36.

Westmarland N, Bows H. Researching gender, violence and abuse: theory, methods, action. Abingdon: Routledge; 2019.

Sikweyiya Y, Jewkes R. Perceptions and experiences of research participants on gender-based violence community based survey: implications for ethical guidelines. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35495.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hossain M, McAlpine A. Gender-based violence research methodologies in humanitarian settings: an evidence review and recommendations. Cardiff: Elrha; 2017.

McGarry J, Ali P. Researching domestic violence and abuse in healthcare settings: challenges and issues. J Res Nurs. 2016;21(5–6):465–76.

World Health Organization (WHO). Ethical and safety recommendations for intervention research on violence against women. In: Building on lessons from the WHO publication ‘Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women’. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Ellsberg M, Potts A. Ethical considerations for research and evaluation on ending violence against women and girls: guidance paper prepared by the global Women’s institute (GWI) for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Canberra: DFAT; 2018.

Van der Heijden I, Harries J, Abrahams N. Ethical considerations for disability-inclusive gender-based violence research: reflections from a south African qualitative case study. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(5):737–49.

Jewkes R, Wagman J. Generating needed evidence while protecting women research participants in a study of domestic violence in South Africa: a fine balance. In: Lavery JV, Wahl ER, Grady C, Emanuel EJ, editors. Ethical issues in international biomedical research: a case book. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 350–5.

Skinner T, Hester M, Malos E. Methodology, feminism and gender violence. In: Skinner T, Hester M, Malos E, editors. Researching gender violence: feminist methodology in action. Cullompton: Willan; 2005. p. 1–22.

Judkins-Cohn TM, Kielwasser-Withrow K, Owen M, Ward J. Ethical principles of informed consent: exploring nurses’ dual role of care provider and researcher. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2014;45(1):35–42.

Letherby G. Feminist research in theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2003.

Roberts H. Women and their doctors: power and powerlessness in the research process. In: Roberts H, editor. Doing feminist research. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1993. p. 7–29.

Stanley L, Wise S. Breaking out again: feminist ontology and epistemology. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1993.

Nagy Hesse-Biber S. Feminist research: exploring, interrogating, and transforming the interconnections of epistemology, methodology and method. In: Nagy Hesse-Biber S, editor. The handbook of feminist research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2012. p. 2–26.

Chapter Google Scholar

Oliveira E. The personal is political: a feminist reflection on a journey into participatory arts-based research with sex worker migrants in South Africa. Gender Dev. 2019;27(3):523–40.

Jaggar AM. Love and knowledge: emotion in feminist epistemology. Inquiry. 1989;32(2):151–76.

Krystalli R. Narrating violence: feminist dilemmas and approaches. In: Shepherd LJ, editor. Handbook on gender and violence. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2019. p. 173–88.

Haraway DJ. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud. 1988;14(3):575–99.

hooks, b. Yearning: race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press; 1990.

Lorde A. The Master’s tools will never dismantle the Master’s house. In: Sister outsider: essays and speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press; 2007. p. 110–4.

Tuhiwai Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books; 2012.

Ahmed S. A phenomenology of whiteness. Fem Theory. 2007;8(2):149–68.

Mannell J, Guta A. The ethics of researching intimate partner violence in global health: a case study from global health research. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(8):1035–49.

Nnawulezi N, Lippy C, Serrata J, Rodriguez R. Doing equitable work in inequitable conditions: an introduction to a special issue on transformative research methods in gender-based violence. J Fam Violence. 2018;33:507–13.

Narayan U. Dislocating cultures: identities, traditions, and third world feminism. Abingdon: Routledge; 1997.

Palmary I. “In your experience”: research as gendered cultural translation. Gend Place Cult. 2011;18(1):99–113.

Vara R, Patel N. Working with interpreters in qualitative psychological research: methodological and ethical issues. Qual Res Psychol. 2011;9(1):75–87.

Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–99.

Connell R. Gender, health and theory: conceptualising the issue, in local and world perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1675–83.

Lykes MB, Scheib H. The artistry of emancipatory practice: photovoice, creative techniques, and feminist anti-racist participatory action research. In: Bradbury H, editor. The SAGE handbook of action research. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2017. p. 130–41.

Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(12):1667–76.

Kesby M, Kindon S, Pain R. “Participatory” approaches and diagramming techniques. In: Flowerdew R, Martin D, editors. Methods in human geography. A guide for students doing a research project. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education; 2005. p. 144–66.

Fals-Borda O. The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. Int Sociol. 1987;2(4):329–47.

Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. 2nd ed. London: Penguin Books; 1996.

Gaventa J, Cornwall A. Power and knowledge. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, editors. The SAGE handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2008. p. 172–89.

Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–87.

Clark T. “We’re over-researched here!”: exploring accounts of research fatigue within qualitative research engagements. Sociology. 2008;42(5):953–70.

Weber S. Participatory visual research with displaced persons: “listening” to post-conflict experiences through the visual. J Refug Stud. 2019;32(3):417–35.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Sanne Weber & Siân Thomas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sanne Weber .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Institute of Clinical Sciences, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Caroline Bradbury-Jones

Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Louise Isham

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Weber, S., Thomas, S. (2021). Engaging in Gender-Based Violence Research: Adopting a Feminist and Participatory Perspective. In: Bradbury-Jones, C., Isham, L. (eds) Understanding Gender-Based Violence. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65006-3_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65006-3_16

Published : 18 February 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-65005-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-65006-3

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Free Associations Podcast

- Quantitative Methods Review and Primer

- Practically Speaking

- Mini-Master of Public Health (MPH)

- Compassionate Leadership

- Teaching Excellence in Public Health

- Climate Change

- Communication

- Data Visualization

- Environmental Health

- Epidemiology

- Health Equity

- Healthcare Management

- Mental Health

- Monitoring and Evaluation

- Research Methods

- Statistical Computing

- Library Expand Navigation

- Custom Expand Navigation

- About Expand Navigation

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive the latest on events, programs, and news.

- Learning Opportunities

- Summer Institute

- Gender-Based Violence: Research Methods and Analysis (SI 18)

Gender-Based Violence: Research Methods and Analysis

Nafisa halim, phd, ma(s) , research assistant professor, global health, busph, monica adhiambo onyango, phd, rn, mph, ms (nursing) , clinical assistant professor, global health, busph, program description.

Gender-based violence affects people around the world every day. This violence, mainly towards women, reinforces power dynamics and impacts overall health, including physical and psychological development.

This program aims to enhance participants’ ability to conduct technically rigorous, ethically-sound, and policy-oriented research on various forms of gender-based violence. Individuals working on and interested in the areas of sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, adolescent health, HIV, mental health and substance use will most benefit from taking this program.

The program will cover the following topics:

- Conceptualizing and researching various forms of gender-based violence;

- Developing conceptual frameworks for violence and health research;

- Ethics and safety;

- Survey research on violence and questionnaire design;

- Intervention research: approaches and challenges;

- Qualitative research on violence;

- Violence research in healthcare settings

The program will be taught through a series of interactive lectures, practical exercises, group work and assigned reading.

Competencies

Participants will learn:

- Current gold standard methods to conceptualize and measure gender-based violence;

- Validity and reliability of GBV measures;

- Tool development and validation methods;

- Ethical and safety issues in GBV research;

Intended Audience

Participants interested in investigating gender-based violence as part of a quantitative or qualitative study or an intervention evaluation will find it particularly relevant.

Required knowledge/pre-requisites

Participants are expected have some prior familiarity or experience with conducting research.

Discounts available—visit our FAQs page to learn more.

Low-cost, on-campus housing is also available. Contact us for more information.

The Summer Institute process was very easy and well organized

Nafisa Halim

is a sociologist with expertise in monitoring and evaluation of public health programs. As a PI/Co-I, Halim served on twelve evaluation studies, and conducted a wide range of activities including data processing and analysis; sampling and sample size calculations; database development and management; and study implementation and field training. Halim has consulted with WHO, served on research projects funded by USAID, NIH, the Medical Research Council (South Africa) and private foundations, and partnered with several implementing organizations including Pathfinder, Pact Save the Children, World Education Initiatives, icddr,b. Halim was recognized for her excellence in teaching in 2016.

Monica Adhiambo Onyango

has over 25 years’ experience in health care delivery, teaching and research. Her experience includes Kenya Ministry of Health as a nursing officer in management positions at two hospitals and as a lecturer at the Nairobi’s Kenya Medical Training College, School of Nursing. Dr. Onyango also worked as a health team leader with international non-governmental organizations in relief and development in South Sudan, Angola, and a refugee camp in Kenya. In addition to her teaching engagement, she also takes up consultancies on health care delivery, management and research in relief and development contexts. In 2011, Dr. Onyango co-founded the global nursing caucus, whose mission is to advance the role of nursing in global health practice, education and policy through advocacy, collaboration, engagement, and research.

Program Details

-Monday, 9:00am-4:00pm -Tuesday, 9:00am-4:00pm -Wednesday, 9:00am-3:00pm

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Afr Health Sci

- v.22(1); 2022 Mar

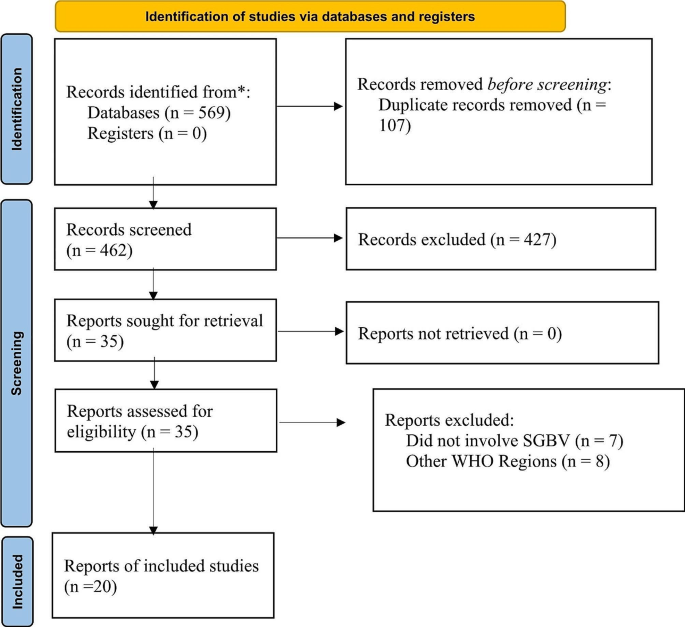

Reporting of sexual and gender-based violence and associated factors among survivors in Mayuge, Uganda

Reporting of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) allows survivors to access support services to minimize the impact of the violence on their lives. However, research shows that most SGBV survivors do not report.

We aimed to determine the proportion of survivors of SGBV in Mayuge District, Uganda, who report SGBV and the factors associated with reporting.

Using a cross-sectional study design, we analyzed data of SGBV survivors in eight villages in Mayuge district collected in a baseline survey of a larger experimental study. Data were analysed using Modified Poisson Regression.

Of the 723 participants, 65% were female. Only 31.9% had reported the SGBV experienced. Reporting was 43% lower among survivors aged 45 years and older (p-value = 0.003), and 41% lower among survivors with higher than a primary school education (p-value = 0.005). Likewise, reporting was 37% lower among survivors who relied on financial support from their partners (p-value = 0.001). Female survivors were also 63% more likely to report (p-value = 0.001), while survivors who were separated/widowed were 185% more likely to report than those who were never married (p-value = 0.006).

Conclusions

Reporting of SGBV by survivors in Mayuge was found to below.

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV), especially against women, remains a major public health problem worldwide. The term SGBV encompasses different forms of violence including sexual violence; physical and emotional violence by an intimate partner; harmful traditional practices; and socio-economic violence 1 . Globally, about 1 in 3 women aged 15 years and older have ever experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence during their lifetime 2 . In Uganda, 22% of women and 8% of men have ever experienced some form of sexual violence 3 .

This violence is more prevalent in the rural and poorer parts of the country like Mayuge district 3 . It is fuelled by society attitudes and practices that promote gender inequality and put women in a subordinate position in relation to men 1 . In all its forms, SGBV is a violation of human rights and undermines the health and dignity of its survivors. Among women, intimate partner violence has been shown to be associated with HIV, sexually transmitted infections 4 , depressive symptoms and suicide attempts 5 . These effects are often worse if survivors do not report or seek help.

Reporting allows survivors of SGBV to access the medical, psychosocial and legal services they need to minimize the impact of the violence on their health and also allows perpetrators to be held accountable. Moreover, formal reporting of SGBV, for example to medical personnel, legal officers or community leaders, allows accurate estimation of the prevalence of the violence. This enables proper resource allocation towards interventions to reduce SGBV and provide appropriate care to survivors. However, data from Demographic and Health Surveys of 24 countries worldwide showed that only 7% of all women who had experienced gender-based violence reported to a formal source 6 . In Uganda, among survivors of sexual and physical violence, only 33% of the female survivors and 30% of the males were reported to have sought help, while 51% of the women and 49% of the men neither sought help nor told anyone about the violence 3 .

The barriers to reporting of SGBV include shame, guilt and stigma associated with, especially, sexual violence; lack of access to medical care 7 ; concerns about confidentiality and being believed 8 ; and barriers specific to seeking help from police like the fear of reprisal resulting from reporting 9 . Similarly, poverty and the costs associated with reporting of SGBV such as transport for the complainant also sometimes hinder reporting and lead to settling cases out of court 10 . Gender inequality has also been cited as a barrier to reporting of SGBV, especially among female survivors. This is because it renders a lot of women submissive and economically dependent on their male partners who may at times be the perpetrators of the violence. 11

However, most previous research on SGBV reporting has focused on sexual and intimate partner violence, overlooking emotional and socio-economic violence. Other studies have only focused on specific vulnerable groups like the women 6 , the disabled 12 , and refuge populations 13 , leaving the reporting behaviour of some groups ununderstood. This study, therefore, aimed to determine the proportion of survivors of emotional, physical, socio-economic and sexual violence who report the violence experienced and to determine the factors associated with reporting. This information will guide the design of interventions to enhance reporting of SGBV experienced.

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was used. The study used baseline data collected in a larger experimental study testing a community intervention to reduce SGBV in Mayuge (14).

Study setting

Data were collected in October 2019 from eight villages in Mayuge, a district in the Eastern part of Uganda. The 2014 National Population and Housing Census put the total population of the district at 473,239 people, with 51.6% of the total population being female and the majority (58.7%) aged between 0 to 17 years 15 .

Participants

The study included men and women aged 18 years and older who reported experiencing at least one form of SGBV. Those aged 15 to 17 years were also included if they were considered emancipated minors who were already married, had children or were pregnant. Participants were only included if they normally resided in the visited households; were domestic servants who had slept in the households for at least five nights a week; or were visitors who had slept in the household for at least the past four weeks.

Sampling procedure

For the larger experimental study, all villages in Mayuge were stratified as either rural or urban and a random sample of four villages was drawn from each stratum. Quota sampling was then used to select an equal number of men and women from each village, with one eligible person per household randomly selected for interview. 14 To select participants for inclusion in this cross-sectional study, all those who reported at least one form of SGBV in the baseline survey of the experimental study were included in the analysis.

A total of 995 participants were included in the larger experimental study 14 . Data of all 723 participants who reported experiencing at least one form of SGBV in their lifetime in the larger study were included in this study.

Participants were considered to have experienced SGBV if they had experienced either physical violence by an intimate partner, emotional violence by an intimate partner, sexual violence or socio-economic violence in their lifetime. Physical, emotional and sexual violence were assessed using questions adopted from Garcia-Moreno, Jansen 16 . Socio-economic violence was used to refer to the denial of access to social and economic rights based on one's gender 1 . It was defined as: the respondent being denied access to education, health assistance or remunerated employment because of their gender; being denied property rights because of their gender 1 ; being prohibited by their partner from getting a job, going to work, trading or earning money; or their partner taking their earnings against their will 17 .

The outcome of interest, reporting of SGBV was assessed using the question: “Have you told anyone about the violence you experienced?” Participants who responded “Yes” were further asked who they had told, and those who had reported to a health worker, police, social services organisation, local leader, religious leader or a counsellor were considered to have reported formally. Survivors who reported to friends, family members and neighbours were considered to have reported to informal sources.

Potential covariates identified from previous literature were also measured. These included; the participants' age, gender, education, marital status, residence, perceived availability of support from their family of birth, their main source of financial support and their attitudes towards wife-beating. The attitudes towards wife-beating were assessed using the question, “In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations: if she goes out without telling him; if she neglects the children; if she argues with him; if she refuses to have sex with him; or if she burns the food”. Respondents who answered “Yes” to at least one of the scenarios were coded as having attitudes accepting of SGBV. 3

Data collection

Data on SGBV, its reporting and the covariates were collected using an interviewer-administered electronic questionnaire through a household survey. This questionnaire was administered in Lusoga, the language predominantly spoken in the area. The interviews were conducted by male and female research assistants, depending on the respondents' preference.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata Version 14 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). Modified Poisson Regression with robust standard errors was used for both bivariate and multivariable analysis, and associations were presented as prevalence ratios and adjusted prevalence ratios (APRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Only variables with p-values less than 0.2 at bivariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was sought from Makerere University School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 702) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Reference Number: HS457ES). Written informed consent was also sought from all study participants. Data were collected according to the World Health Organisation's Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women 18 .

Participant characteristics

Of the 723 participants who reported having experienced at least one form of SGBV in their lifetime, 65% were female ( Table 1 ). Only 16% of the women and 30.4% of the men had attained education higher than primary school. The majority, 78.7% of the women and 80.6% of the men, were married or living with their partners. Most of the men (93.3%) derived their main source of financial support from their incomes, while 45.5% of women relied on their partners for financial support. Among the women, 48.1% found wife-beating justifiable in at least one situation as compared to 26.5% of the men. The commonest type of violence among both sexes was emotional while sexual violence was the least prevalent.

Participant characteristics (N = 723)

Reporting of SGBV

Of the 723 survivors of SGBV, only 231 (31.9%) had reported the violence they had experienced to anyone, and of these, 12.5% had reported formally.

Factors associated with reporting of SGBV

At bivariate analysis, reporting of SGBV appeared to be more prevalent among females and among the separated/widowed, and less prevalent among survivors who had higher than a primary school education and those who did not find wife-beating justifiable in any situation. ( Table 2 )

Bivariate and multivariable analysis of factors associated with reporting to any source. (N = 723)

However, at multivariable analysis, the prevalence of reporting was found to be 43% lower among survivors who were aged 45 years and older as compared to those who were less than 25 years old, APR = 0.57 (95% CI: 0.39, 0.83; p-value = 0.003). Reporting was also 41% lower among those who had attained higher than primary school education, as compared to those with no education at all, APR = 0.59 (CI: 0.41, 0.85; p-value = 0.005). Likewise, reporting was 37% lower among survivors who relied on their partners for financial support as compared to those who relied on their incomes, APR = 0.63 (CI: 0.47, 0.84; p-value = 0.001).

On the other hand, reporting was 63% higher among females than males, APR=1.63 (CI: 1.22, 2.18; p-value = 0.001). Survivors who were separated from their partners or widowed were also more than twice as likely to report the violence experienced as compared to those who were never married, APR = 2.85 (CI: 1.35, 5.99; p-value = 0.006).

We found the level of reporting of SGBV among survivors in Mayuge to be low, even lower than the 39.9% reported for female survivors of gender-based violence in 24 developing countries, including Uganda. However, formal reporting in our study was higher than the 7% recorded for these survivors.6 Reporting was also found to be more prevalent among women. This could be related to the patriarchal nature of many societies in Uganda (19). These uphold masculinity idealisations that condition male survivors of SGBV to remain silent about the violence experienced 20. Similar underreporting of SGBV has been documented in conflict-afflicted Democratic Republic of Congo among male rape survivors because of feelings of shame, stigma and emasculation21. Such society ideals of what is expected of a man hinder reporting of SGBV.

We found reporting to be lower among survivors aged 45 years and older as compared to those younger than 25. This finding may imply that, because of awareness creation, survivors have gradually become more knowledgeable about the importance of reporting and the available reporting channels. And, because life-time experience of SGBV was used in the assessment, the younger survivors who had more recent experiences of SGBV may have been more likely to report than those 45 years and older who may have experienced violence over a longer period. However, this result is contrary to findings by Palermo, Bleck6 where increasing age was shown to be associated with an increased likelihood of reporting among female survivors of gender-based violence in developing countries.

Reporting was also lower among survivors who had higher than a primary school education as compared to those with no education at all. Older and educated community members are usually looked up to by others, and this lower reporting may be related to the need to uphold this social standing. However, education creates awareness about the available reporting channels and would be expected to increase reporting, although this is contrary to our findings. Palermo, Bleck 6 also found contradicting results about the effect of education on reporting of SGBV: in some countries like Nigeria, women with no education were less likely to report SGBV while in others like Tanzania and Philippines, women with higher education were less likely to report. Reporting was lower among survivors who relied on their partners for financial support as compared to those who relied on their income. In Uganda, employed women and men were found to be more likely than the unemployed to seek help to end violence 3 . Women's financial dependency on their partners was also cited as a barrier to help-seeking by abused women in Rwanda because their partners controlled the family resources and made decisions about how money could be spent 11 . In our study, more women reported relying on their partners for financial support than men, further highlighting the need for economic empowerment of those most vulnerable to SGBV to increase their autonomy in relationships and ability to report and seek help in case of violence.

Survivors who were separated from their partners or widowed had a higher prevalence of SGBV reporting than those who were never married. This is comparable to what Palermo, Bleck 6 found in 15 of 24 developing countries, where formerly married women were more likely to report the violence experienced than currently married women. The 2016 UDHS also found separated and divorced men and women to be most likely to seek help for the violence experienced, as compared to the married and those who were never-married 3 . This could be related to the ignorance among the married about the fact that marital rape is a crime that needs to be reported 11 . Umubyeyi, Persson 11 also reported that family matters, including violence and abuse against women, in Rwanda were considered secrets to be retained within the family, which also affected reporting and help-seeking among survivors of intimate partner violence. As such, divorced and separated survivors may feel less bound by such expectations of secrecy and may be more open to speaking out about the violence experienced both in and outside marriage. We, however, did not observe any statistical difference in reporting between the married and those who were never married.

Limitations

Since a quantitative cross-sectional study design was used, we were unable to establish temporality between the exposure variables and reporting. We were therefore limited in our understanding of the true relationship between variables like marital status and the reporting of SGBV. Furthermore, we were limited in our ability to understand the institutional barriers to reporting. More research using qualitative methods is recommended to further explore and understand the barriers to SGBV reporting.

Additionally, because SGBV is a sensitive issue, underreporting of the violence experienced by the study participants could have occurred. We, however, minimised this by training research assistants to conduct interviews in private spaces, away from any interruptions to encourage accurate reporting.

The reporting of SGBV was found to be low among survivors in Mayuge. Reporting was more prevalent among female survivors and those who were separated from their partners or widowed. On the other hand, it was less prevalent among survivors aged 45 years and older, those with higher than a primary education and among those who received their main source of financial support from their partners.

We recommend interventions that promote dialogues about SGBV and its reporting, especially among the men, older survivors and the educated to encourage reporting and promote help-seeking to stop the violence and to increase utilisation of the available support services for survivors. We also recommend economic empowerment for those most vulnerable to SGBV to increase their autonomy in relationships and ability to report the violence experienced.

Additionally, leaders at the community level, such as the religious and local leaders, should be empowered with information and resources to effectively provide support to survivors of SGBV in their communities, as these are sometimes the survivors' first points of contact.

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and the research assistants for their contribution to the data collection procedures.

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Release of the National Plan to End Gender-Based Violence: Strategies for Action

May 25, 2023

Today, the White House released the first-ever U.S. National Plan to End Gender-Based Violence: Strategies for Action . When President Biden issued the Executive Order establishing the first-ever White House Gender Policy Council , he called on the Gender Policy Council to develop the first U.S. government-wide plan to prevent and address sexual violence, intimate partner violence, stalking, and other forms of gender-based violence (referred to collectively as GBV).

Gender-based violence is a public safety and public health crisis, affecting urban, suburban, rural, and Tribal communities in the United States. It is experienced by individuals of all backgrounds and can occur across the life course. Though we have made significant progress to expand services and legal protections for survivors, much work remains.

Through this National Plan to End Gender-Based Violence (National Plan), the Biden-Harris Administration is advancing a comprehensive, government-wide approach to preventing and addressing GBV in the United States. The National Plan identifies seven strategic pillars undergirding this approach: 1) Prevention; 2) Support, Healing, Safety, and Well-Being; 3) Economic Security and Housing Stability; 4) Online Safety; 5) Legal and Justice Systems; 6) Emergency Preparedness and Crisis Response; and 7) Research and Data. Building upon existing federal initiatives, the National Plan provides an important framework for strengthening ongoing federal action and interagency collaboration, and for informing new research, policy development, program planning, service delivery, and other efforts across each of these core issue areas. It is guided by the lessons learned and progress made as the result of tireless and courageous leadership from GBV survivors, advocates, researchers, and policymakers, as well as other dedicated professionals and community members who lead prevention and response efforts.

And while the Plan is focused specifically on federal action, it is designed to be accessible and useful to public and private stakeholders across the United States for adaptation and expansion—because all communities are vital to ending GBV.

The priorities in this National Plan to End GBV, as well as those included in the 2022 update to the U.S. Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Gender-Based Violence Globally , reflect our nation’s ongoing commitment to advancing efforts to prevent and address gender-based violence both at home and abroad. As stated in the National Plan, “Ending gender-based violence is, quite simply, a matter of human rights and justice.”

While the National Plan provides a roadmap to guide future efforts, addressing GBV has been a core priority since the start of the Biden-Harris Administration, as reflected in the highlights below of recent and longer-term actions undertaken to prevent and address GBV.

Recent Federal Initiatives to Prevent and Address GBV in the United States Include:

- Elevating the Office of Family Violence Prevention and Services : The Assistant Secretary of the Administration of Children and Families (ACF) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) established the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA) Program as its own office under the ACF Immediate Office of the Assistant Secretary in March 2023, now known as the Office of Family Violence Prevention and Services (OFVPS) . The establishment of OFVPS reflects the importance of work to prevent and address intimate partner violence, domestic violence, dating violence, and sexual assault; to coordinate trauma informed services and support across ACF, HHS, and the federal government; and to strengthen attention to policy and practice issues relating to addressing the needs of survivors.

- Establishing New FVPSA Discretionary Grant Programs: Funding for FVPSA programs increased by 20% in the FY 2023 federal budget. In addition to allocating increased funding for existing FVPSA programs, the OFVPS is publishing four new competitive discretionary notice of funding opportunities in May 2023. This includes $7.5 million to fund thirty cooperative agreements to support Culturally Specific Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault grants for community-based organizations to build and sustain organizational capacity in delivering trauma-informed, developmentally sensitive, culturally relevant services for children, individuals, and families affected by sexual assault and domestic violence. It also includes for the first time cooperative agreements in the amount of $500,000 each to fund two Sexual Assault Capacity Building Centers to provide national technical assistance to states, territories, and tribal governments in supporting comprehensive services for rape crisis centers, sexual assault programs, culturally specific programs, and other nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations or tribal programs that provide direct intervention and related assistance to victims of sexual assault, without regard to age.

- Announcing Grant Awards for the Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership through Alliances Initiative : On May 3,the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) announced funding awards for thirteen state domestic violence coalitions under the Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances (DELTA): Achieving Health Equity through Addressing Disparities (AHEAD) initiative . DELTA AHEAD recipients will work to decrease risk factors and increase protective factors related to intimate partner violence by addressing social determinants of health and health equity.

- Launching the HRSA Strategy to Address Intimate Partner Violence : On May 16, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the Department of Health and Human Services launched the 2023-2025 HRSA Strategy to Address Intimate Partner Violence . The agency-wide Strategy identifies strategic objectives and activities for HRSA Bureaus and Offices to undertake that will contribute to these aims to enhance HRSA coordination of efforts to strengthen infrastructure and workforce capacity to address intimate partner violence and promote prevention through evidence-based programs.