Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity

This essay about humanism explores the enduring pursuit of humanity’s essence amidst modern challenges. It into the core principles of humanism, emphasizing empathy, equality, and action against injustice. Through reflection on the role of culture, creativity, and technology, it underscores the imperative of embracing our shared humanity. Ultimately, it advocates for a world where dignity and inclusivity reign, inviting readers to join in the collective endeavor of creating a more just and compassionate society.

How it works

In the grand tapestry of human history, amidst the tumultuous shifts of empires, ideologies, and technologies, one enduring thread has woven through every era: the pursuit of humanism. It is a beacon that has guided thinkers, artists, and activists alike, beckoning them to rediscover the essence of humanity in a world often veiled by division and discord.

Humanism, at its core, is a celebration of the human spirit—the recognition of our capacity for reason, empathy, and creativity. It is a philosophy that places human welfare and dignity at the forefront, advocating for the liberation of individuals from oppression, ignorance, and prejudice.

Yet, in our modern age, as we stand on the precipice of unprecedented technological advancement and societal transformation, the essence of humanity can sometimes feel obscured, overshadowed by the clamor of progress and the pursuit of material gain.

In such times, the call to rediscover humanism becomes ever more urgent. It is a call to pause amidst the frenetic pace of life, to reflect on what it truly means to be human—to cultivate empathy in an age of indifference, to nurture solidarity in a world fractured by division, and to champion justice in the face of injustice.

At the heart of humanism lies the belief in the inherent worth and dignity of every individual. It is a belief that transcends the boundaries of race, gender, religion, and nationality—a belief that recognizes the fundamental equality of all human beings. In a world where prejudice and discrimination continue to plague societies, embracing humanism means embracing the imperative of equality and inclusivity. It means standing in solidarity with the marginalized and the oppressed, amplifying their voices, and advocating for their rights.

Moreover, humanism calls upon us to cultivate a deep sense of empathy—the ability to understand and share in the experiences of others. In a world that often seems defined by conflict and polarization, empathy serves as a bridge that connects us across our differences. It enables us to recognize our shared humanity in the face of adversity and to forge bonds of compassion and understanding. Through acts of empathy, whether small gestures of kindness or bold acts of solidarity, we reaffirm our interconnectedness as members of the human family.

Yet, humanism is not merely a philosophy of passive contemplation—it is a philosophy of action. It compels us to confront the injustices and inequalities that pervade our societies and to strive for meaningful change. It calls upon us to challenge systems of oppression and to work towards creating a more just and equitable world for all. Whether through grassroots activism, policy advocacy, or community organizing, humanism inspires us to be agents of positive transformation, to stand up for what is right, and to champion the cause of justice.

In our quest to rediscover the essence of humanity, we must also recognize the profound role of culture and creativity. Art, literature, music, and other forms of expression have the power to illuminate the human experience, to evoke empathy, and to inspire change. They serve as mirrors that reflect the beauty, the complexity, and the resilience of the human spirit. By embracing and nurturing the arts, we enrich our understanding of ourselves and of others, forging connections that transcend the boundaries of language and culture.

In the digital age, technology has become an integral part of the human experience, shaping the way we interact, communicate, and navigate the world. Yet, even as we marvel at the wonders of technological innovation, we must not lose sight of our humanity. Humanism challenges us to harness the power of technology for the greater good—to use it as a tool for advancing knowledge, fostering connections, and promoting human flourishing. It reminds us that behind every line of code, every algorithm, and every interface, there lies the imprint of human ingenuity and aspiration.

Ultimately, the journey of rediscovering the essence of humanity is a deeply personal and collective endeavor. It requires us to look inward, to confront our biases and limitations, and to strive for growth and self-improvement. It also calls upon us to reach outwards, to forge meaningful connections with others, and to work together towards a shared vision of a better world.

In a time marked by uncertainty and upheaval, humanism offers us a guiding light—a timeless philosophy that reminds us of our common humanity, our capacity for empathy, and our collective responsibility to create a more just and compassionate world. It is a philosophy that invites us to embrace the fullness of our humanity—to celebrate our differences, to cultivate empathy, and to strive for a future where the dignity and worth of every individual are upheld and cherished.

Cite this page

Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity. (2024, Jun 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/

"Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity." PapersOwl.com , 1 Jun 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/ [Accessed: 2 Jun. 2024]

"Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity." PapersOwl.com, Jun 01, 2024. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/

"Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity," PapersOwl.com , 01-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/. [Accessed: 2-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Humanism: Rediscovering the Essence of Humanity . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/humanism-rediscovering-the-essence-of-humanity/ [Accessed: 2-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing Strong Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable

An argumentative or persuasive piece of writing must begin with a debatable thesis or claim. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on. If your thesis is something that is generally agreed upon or accepted as fact then there is no reason to try to persuade people.

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

This thesis statement is not debatable. First, the word pollution implies that something is bad or negative in some way. Furthermore, all studies agree that pollution is a problem; they simply disagree on the impact it will have or the scope of the problem. No one could reasonably argue that pollution is unambiguously good.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

This is an example of a debatable thesis because reasonable people could disagree with it. Some people might think that this is how we should spend the nation's money. Others might feel that we should be spending more money on education. Still others could argue that corporations, not the government, should be paying to limit pollution.

Another example of a debatable thesis statement:

In this example there is also room for disagreement between rational individuals. Some citizens might think focusing on recycling programs rather than private automobiles is the most effective strategy.

The thesis needs to be narrow

Although the scope of your paper might seem overwhelming at the start, generally the narrower the thesis the more effective your argument will be. Your thesis or claim must be supported by evidence. The broader your claim is, the more evidence you will need to convince readers that your position is right.

Example of a thesis that is too broad:

There are several reasons this statement is too broad to argue. First, what is included in the category "drugs"? Is the author talking about illegal drug use, recreational drug use (which might include alcohol and cigarettes), or all uses of medication in general? Second, in what ways are drugs detrimental? Is drug use causing deaths (and is the author equating deaths from overdoses and deaths from drug related violence)? Is drug use changing the moral climate or causing the economy to decline? Finally, what does the author mean by "society"? Is the author referring only to America or to the global population? Does the author make any distinction between the effects on children and adults? There are just too many questions that the claim leaves open. The author could not cover all of the topics listed above, yet the generality of the claim leaves all of these possibilities open to debate.

Example of a narrow or focused thesis:

In this example the topic of drugs has been narrowed down to illegal drugs and the detriment has been narrowed down to gang violence. This is a much more manageable topic.

We could narrow each debatable thesis from the previous examples in the following way:

Narrowed debatable thesis 1:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just the amount of money used but also how the money could actually help to control pollution.

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate focus.

Qualifiers such as " typically ," " generally ," " usually ," or " on average " also help to limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the rule.

Types of claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to approach your topic, or, in other words, what type of claim you want to make, is one way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of your broader topic.

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

Claims about value: These are claims made of what something is worth, whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:

Claims about solutions or policies: These are claims that argue for or against a certain solution or policy approach to a problem. Example:

Which type of claim is right for your argument? Which type of thesis or claim you use for your argument will depend on your position and knowledge of the topic, your audience, and the context of your paper. You might want to think about where you imagine your audience to be on this topic and pinpoint where you think the biggest difference in viewpoints might be. Even if you start with one type of claim you probably will be using several within the paper. Regardless of the type of claim you choose to utilize it is key to identify the controversy or debate you are addressing and to define your position early on in the paper.

What Makes a Thesis Statement Spectacular? — 5 things to know

Table of Contents

What Is a Thesis Statement?

A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that states the primary idea of an essay or a research paper . In this statement, the authors declare their beliefs or what they intend to argue in their research study. The statement is clear and concise, with only one or two sentences.

Thesis Statement — An Essential in Thesis Writing

A thesis statement distills the research paper idea into one or two sentences. This summary organizes your paper and develops the research argument or opinion. The statement is important because it lets the reader know what the research paper will talk about and how the author is approaching the issue. Moreover, the statement also serves as a map for the paper and helps the authors to track and organize their thoughts more efficiently.

A thesis statement can keep the writer from getting lost in a convoluted and directionless argument. Finally, it will also ensure that the research paper remains relevant and focused on the objective.

Where to Include the Thesis Statement?

The thesis statement is typically placed at the end of the introduction section of your essay or research paper. It usually consists of a single sentence of the writer’s opinion on the topic and provides a specific guide to the readers throughout the paper.

6 Steps to Write an Impactful Thesis Statement

Step 1 – analyze the literature.

Identify the knowledge gaps in the relevant research paper. Analyze the deeper implications of the author’s research argument. Was the research objective mentioned in the thesis statement reversed later in the discussion or conclusion? Does the author contradict themselves? Is there a major knowledge gap in creating a relevant research objective? Has the author understood and validated the fundamental theories correctly? Does the author support an argument without having supporting literature to cite? Answering these or related questions will help authors develop a working thesis and give their thesis an easy direction and structure.

Step 2 – Start with a Question

While developing a working thesis, early in the writing process, you might already have a research question to address. Strong research questions guide the design of studies and define and identify specific objectives. These objectives will assist the author in framing the thesis statement.

Step 3 – Develop the Answer

After initial research, the author could formulate a tentative answer to the research question. At this stage, the answer could be simple enough to guide the research and the writing process. After writing the initial answer, the author could elaborate further on why this is the chosen answer. After reading more about the research topic, the author could write and refine the answers to address the research question.

Step 4 – Write the First Draft of the Thesis Statement

After ideating the working thesis statement, make sure to write it down. It is disheartening to create a great idea for a thesis and then forget it when you lose concentration. The first draft will help you think clearly and logically. It will provide you with an option to align your thesis statement with the defined research objectives.

Step 5 – Anticipate Counter Arguments Against the Statement

After developing a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This list of arguments will help you refute the thesis later. Remember that every argument has a counterargument, and if yours does not have one, what you state is not an argument — it may be a fact or opinion, but not an argument.

Step 6 – Refine the Statement

Anticipating counterarguments will help you refine your statement further. A strong thesis statement should address —

- Why does your research hold this stand?

- What will readers learn from the essay?

- Are the key points of your argumentative or narrative?

- Does the final thesis statement summarize your overall argument or the entire topic you aim to explain in the research paper?

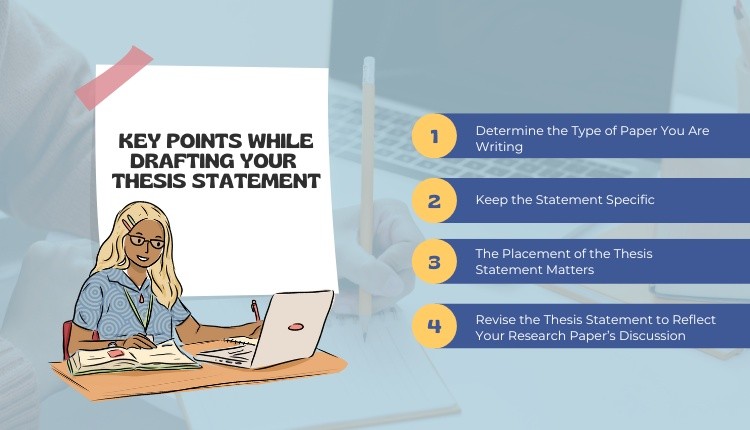

5 Tips to Create a Compelling Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a crucial part of any academic paper. Clearly stating the main idea of your research helps you focus on the objectives of your paper. Refer to the following tips while drafting your statement:

1. Keep it Concise

The statement should be short and precise. It should contain no more than a couple of sentences.

2. Make it Specific

The statement should be focused on a specific topic or argument. Covering too many topics will only make your paper weaker.

3. Express an Opinion

The statement should have an opinion on an issue or controversy. This will make your paper arguable and interesting to read.

4. Be Assertive

The statement should be stated assertively and not hesitantly or apologetically. Remember, you are making an argument — you need to sound convincing!

5. Support with Evidence

The thesis should be supported with evidence from your paper. Make sure you include specific examples from your research to reinforce your objectives.

Thesis Statement Examples *

Example 1 – alcohol consumption.

High levels of alcohol consumption have harmful effects on your health, such as weight gain, heart disease, and liver complications.

This thesis statement states specific reasons why alcohol consumption is detrimental. It is not required to mention every single detriment in your thesis.

Example 2 – Benefits of the Internet

The internet serves as a means of expediently connecting people across the globe, fostering new friendships and an exchange of ideas that would not have occurred before its inception.

While the internet offers a host of benefits, this thesis statement is about choosing the ability that fosters new friendships and exchange ideas. Also, the research needs to prove how connecting people across the globe could not have happened before the internet’s inception — which is a focused research statement.

*The following thesis statements are not fully researched and are merely examples shown to understand how to write a thesis statement. Also, you should avoid using these statements for your own research paper purposes.

A gripping thesis statement is developed by understanding it from the reader’s point of view. Be aware of not developing topics that only interest you and have less reader attraction. A harsh yet necessary question to ask oneself is — Why should readers read my paper? Is this paper worth reading? Would I read this paper if I weren’t its author?

A thesis statement hypes your research paper. It makes the readers excited about what specific information is coming their way. This helps them learn new facts and possibly embrace new opinions.

Writing a thesis statement (although two sentences) could be a daunting task. Hope this blog helps you write a compelling one! Do consider using the steps to create your thesis statement and tell us about it in the comment section below.

Great in impactation of knowledge

An interesting expository. Thanks for the concise explanation.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![thesis statement about humanity What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement.

Your thesis statement is one of the most important parts of your paper. It expresses your main argument succinctly and explains why your argument is historically significant. Think of your thesis as a promise you make to your reader about what your paper will argue. Then, spend the rest of your paper–each body paragraph–fulfilling that promise.

Your thesis should be between one and three sentences long and is placed at the end of your introduction. Just because the thesis comes towards the beginning of your paper does not mean you can write it first and then forget about it. View your thesis as a work in progress while you write your paper. Once you are satisfied with the overall argument your paper makes, go back to your thesis and see if it captures what you have argued. If it does not, then revise it. Crafting a good thesis is one of the most challenging parts of the writing process, so do not expect to perfect it on the first few tries. Successful writers revise their thesis statements again and again.

A successful thesis statement:

- makes an historical argument

- takes a position that requires defending

- is historically specific

- is focused and precise

- answers the question, “so what?”

How to write a thesis statement:

Suppose you are taking an early American history class and your professor has distributed the following essay prompt:

“Historians have debated the American Revolution’s effect on women. Some argue that the Revolution had a positive effect because it increased women’s authority in the family. Others argue that it had a negative effect because it excluded women from politics. Still others argue that the Revolution changed very little for women, as they remained ensconced in the home. Write a paper in which you pose your own answer to the question of whether the American Revolution had a positive, negative, or limited effect on women.”

Using this prompt, we will look at both weak and strong thesis statements to see how successful thesis statements work.

While this thesis does take a position, it is problematic because it simply restates the prompt. It needs to be more specific about how the Revolution had a limited effect on women and why it mattered that women remained in the home.

Revised Thesis: The Revolution wrought little political change in the lives of women because they did not gain the right to vote or run for office. Instead, women remained firmly in the home, just as they had before the war, making their day-to-day lives look much the same.

This revision is an improvement over the first attempt because it states what standards the writer is using to measure change (the right to vote and run for office) and it shows why women remaining in the home serves as evidence of limited change (because their day-to-day lives looked the same before and after the war). However, it still relies too heavily on the information given in the prompt, simply saying that women remained in the home. It needs to make an argument about some element of the war’s limited effect on women. This thesis requires further revision.

Strong Thesis: While the Revolution presented women unprecedented opportunities to participate in protest movements and manage their family’s farms and businesses, it ultimately did not offer lasting political change, excluding women from the right to vote and serve in office.

Few would argue with the idea that war brings upheaval. Your thesis needs to be debatable: it needs to make a claim against which someone could argue. Your job throughout the paper is to provide evidence in support of your own case. Here is a revised version:

Strong Thesis: The Revolution caused particular upheaval in the lives of women. With men away at war, women took on full responsibility for running households, farms, and businesses. As a result of their increased involvement during the war, many women were reluctant to give up their new-found responsibilities after the fighting ended.

Sexism is a vague word that can mean different things in different times and places. In order to answer the question and make a compelling argument, this thesis needs to explain exactly what attitudes toward women were in early America, and how those attitudes negatively affected women in the Revolutionary period.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a negative impact on women because of the belief that women lacked the rational faculties of men. In a nation that was to be guided by reasonable republican citizens, women were imagined to have no place in politics and were thus firmly relegated to the home.

This thesis addresses too large of a topic for an undergraduate paper. The terms “social,” “political,” and “economic” are too broad and vague for the writer to analyze them thoroughly in a limited number of pages. The thesis might focus on one of those concepts, or it might narrow the emphasis to some specific features of social, political, and economic change.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution paved the way for important political changes for women. As “Republican Mothers,” women contributed to the polity by raising future citizens and nurturing virtuous husbands. Consequently, women played a far more important role in the new nation’s politics than they had under British rule.

This thesis is off to a strong start, but it needs to go one step further by telling the reader why changes in these three areas mattered. How did the lives of women improve because of developments in education, law, and economics? What were women able to do with these advantages? Obviously the rest of the paper will answer these questions, but the thesis statement needs to give some indication of why these particular changes mattered.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a positive impact on women because it ushered in improvements in female education, legal standing, and economic opportunity. Progress in these three areas gave women the tools they needed to carve out lives beyond the home, laying the foundation for the cohesive feminist movement that would emerge in the mid-nineteenth century.

Thesis Checklist

When revising your thesis, check it against the following guidelines:

- Does my thesis make an historical argument?

- Does my thesis take a position that requires defending?

- Is my thesis historically specific?

- Is my thesis focused and precise?

- Does my thesis answer the question, “so what?”

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Seven Theses on Human Rights: (1) The Idea of Humanity

by Costas Douzinas | 16 May 2013

If ‘humanity’ is the normative source of moral and legal rules, do we know what ‘humanity’ is? Important philosophical and ontological questions are involved here. Let me have a brief look at its history.

Pre-modern societies did not develop a comprehensive idea of the human species. Free men were Athenians or Spartans, Romans or Carthaginians, but not members of humanity; they were Greeks or barbarians, but not humans. According to classical philosophy, a teleologically determined human nature distributes people across social hierarchies and roles and endows them with differentiated characteristics. The word humanitas appeared for the first time in the Roman Republic as a translation of the Greek word paideia. It was defined as eruditio et institutio in bonas artes (the closest modern equivalent is the German Bildung ). The Romans inherited the concept from Stoicism and used it to distinguish between the homo humanus, the educated Roman who was conversant with Greek culture and philosophy and was subjected to the jus civile , and the homines barbari, who included the majority of the uneducated non-Roman inhabitants of the Empire. Humanity enters the western lexicon as an attribute and predicate of homo , as a term of separation and distinction. For Cicero as well as the younger Scipio, humanitas implies generosity, politeness, civilization, and culture and is opposed to barbarism and animality. 1 Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Viking Press, 1965), 107. “Only those who conform to certain standards are really men in the full sense, and fully merit the adjective ‘human’ or the attribute ‘humanity.’” 2 B.L. Ullman, “What are the Humanities?” Journal of Higher Education 17/6 (1946), at 302. Hannah Arendt puts it sarcastically: ‘a human being or homo in the original meaning of the word indicates someone outside the range of law and the body politic of the citizens, as for instance a slave – but certainly a politically irrelevant being.’ 3 H.C. Baldry, The Unity of Mankind in Greek Thought , (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1965), 201.

If we now turn to the political and legal uses of humanitas , a similar history emerges. The concept ‘humanity’ has been consistently used to separate, distribute, and classify people into rulers, ruled, and excluded. ‘Humanity’ acts as a normative source for politics and law against a background of variable inhumanity. This strategy of political separation curiously entered the historical stage at the precise point when the first proper universalist conception of humanitas emerged in Christian theology, captured in the St Paul’s statement, that there is no Greek or Jew, man or woman, free man or slave (Epistle to the Galatians 3:28). All people are equally part of humanity because they can be saved in God’s plan of salvation and, secondly, because they share the attributes of humanity now sharply differentiated from a transcended divinity and a subhuman animality. For classical humanism, reason determines the human: man is a zoon logon echon or animale rationale . For Christian metaphysics, on the other hand, the immortal soul, both carried and imprisoned by the body, is the mark of humanity. The new idea of universal equality, unknown to the Greeks, entered the western world as a combination of classical and Christian metaphysics.

The divisive action of ‘humanity’ survived the invention of its spiritual equality. Pope, Emperor, Prince, and King, these representatives and disciples of God on earth were absolute rulers. Their subjects, the sub-jecti or sub-diti , take the law and their commands from their political superiors. More importantly, people will be saved in Christ only if they accept the faith, since non-Christians have no place in the providential plan. This radical divide and exclusion founded the ecumenical mission and proselytizing drive of Church and Empire. Christ’s spiritual law of love turned into a battle cry: let us bring the pagans to the grace of God, let us make the singular event of Christ universal, let us impose the message of truth and love upon the whole world. The classical separation between Greek (or human) and barbarian was based on clearly demarcated territorial and linguistic frontiers. In the Christian empire, the frontier was internalized and split the known globe diagonally between the faithful and the heathen. The barbarians were no longer beyond the city as the city expanded to include the known world. They became ‘enemies within’ to be appropriately corrected or eliminated if they stubbornly refused spiritual or secular salvation.

The meaning of humanity after the conquest of the ‘New World’ was vigorously contested in one of the most important public debates in history. In April 1550, Charles V of Spain called a council of state in Valladolid to discuss the Spanish attitude towards the vanquished Indians of Mexico. The philosopher Ginés de Sepulveda and the Bishop Bartholomé de las Casas, two major figures of the Spanish Enlightenment, debated on opposite sides. Sepulveda, who had just translated Aristotle’s Politics into Spanish, argued that “the Spaniards rule with perfect right over the barbarians who, in prudence, talent, virtue, humanity are as inferior to the Spaniards as children to adults, women to men, the savage and cruel to the mild and gentle, I might say as monkey to men.” 4 Ginés de Sepulveda, Democrates Segundo of De las Justas Causa de la Guerra contra los Indios (Madrid: Institute Fransisco de Vitoria, 1951), 33 quoted in Tzvetan Todorov, The Conquest of America trans. Richard Howard (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 153. The Spanish crown should feel no qualms in dealing with Indian evil. The Indians could be enslaved and treated as barbarian and savage slaves in order to be civilized and proselytized.

Las Casas disagreed. The Indians have well-established customs and settled ways of life, he argued, they value prudence and have the ability to govern and organize families and cities. They have the Christian virtues of gentleness, peacefulness, simplicity, humility, generosity, and patience, and are waiting to be converted. They look like our father Adam before the Fall, wrote las Casas in his Apologia, they are ‘unwitting’ Christians. In an early definition of humanism, las Casas argued that “all the people of the world are humans under the only one definition of all humans and of each one, that is that they are rational … Thus all races of humankind are one.” 5 Bartholomé de las Casas, Obras Completas , Vol. 7 (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1922), 536–7. His arguments combined Christian theology and political utility. Respecting local customs is good morality but also good politics: the Indians would convert to Christianity (las Casas’ main concern) but also accept the authority of the Crown and replenish its coffers, if they were made to feel that their traditions, laws, and cultures are respected. But las Casas’ Christian universalism was, like all universalisms, exclusive. He repeatedly condemned “Turks and Moors, the veritable barbarian outcasts of the nations” since they cannot be seen as “unwitting” Christians. An “empirical” universalism of superiority and hierarchy (Sepulveda) and a normative one of truth and love (las Casas) end up being not very different. As Tzvetan Todorov pithily remarks, there is “violence in the conviction that one possesses the truth oneself, whereas this is not the case for others, and that one must furthermore impose that truth on those others.” 6 Todorov, The Conquest of America 166, 168.

The conflicting interpretations of humanity by Sepulveda and las Casas capture the dominant ideologies of Western empires, imperialisms, and colonialisms. At one end, the (racial) other is inhuman or subhuman. This justifies enslavement, atrocities, and even annihilation as strategies of the civilizing mission. At the other end, conquest, occupation, and forceful conversion are strategies of spiritual or material development, of progress and integration of the innocent, naïve, undeveloped others into the main body of humanity.

These two definitions and strategies towards otherness act as supports of western subjectivity. The helplessness, passivity, and inferiority of the “undeveloped” others turns them into our narcissistic mirror-image and potential double. These unfortunates are the infants of humanity. They are victimized and sacrificed by their own radical evildoers; they are rescued by the West who helps them grow, develop and become our likeness. Because the victim is our mirror image, we know what his interest is and impose it “for his own good.” At the other end, the irrational, cruel, victimizing others are projections of the Other of our unconscious. As Slavoj Žižek puts it, “there is a kind of passive exposure to an overwhelming Otherness, which is the very basis of being human … [the inhuman] is marked by a terrifying excess which, although it negates what we understand as ‘humanity’ is inherent to being human.” 7 Slavoj Žižek, “Against Human Rights 56,” New Left Review (July–August 2005), 34. We have called this abysmal other lurking in the psyche and unsettling the ego various names: God or Satan, barbarian or foreigner, in psychoanalysis the death drive or the Real. Today they have become the “axis of evil,” the “rogue state,” the “bogus refugee,” or the “illegal” migrant. They are contemporary heirs to Sepulveda’s “monkeys,” epochal representatives of inhumanity.

A comparison of the cognitive strategies associated with the Latinate humanitas and the Greek anthropos is instructive. The humanity of humanism (and of the academic Humanities) 8 Costas Douzinas, “For a Humanities of Resistance,” Critical Legal Thinking, December 7, 2010, https://www.criticallegalthinking.com/2010/12/07/for-a-humanities-of-resistance/ unites knowing subject and known object following the protocols of self-reflection. The anthropos of physical and social anthropology, on the other hand, is the object only of cognition. Physical anthropology examines bodies, senses, and emotions, the material supports of life. Social anthropology studies diverse non-western peoples, societies, and cultures, but not the human species in its essence or totality. These peoples emerged out of and became the object of observation and study through discovery, conquest, and colonization in the new world, Africa, Asia, or in the peripheries of Europe. As Nishitani Osamu puts it, humanity and anthropos signify two asymmetrical regimes of knowledge. Humanity is civilization, anthropos is outside or before civilization. In our globalized world, the minor literatures of anthropos are examined by comparative literature, which compares “civilization” with lesser cultures.

The gradual decline of Western dominance is changing these hierarchies. Similarly, the disquiet with a normative universalism, based on a false conception of humanity, indicates the rise of local, concrete, and context-bound normativities.

In conclusion, because ‘humanity’ has no fixed meaning, it cannot act as a source of norms. Its meaning and scope keeps changing according to political and ideological priorities. The continuously changing conceptions of humanity are the best manifestations of the metaphysics of an age. Perhaps the time has come for anthropos to replace the human. Perhaps the rights to come will be anthropic (to coin a term) rather than human, expressing and promoting singularities and differences instead of the sameness and equivalences of hitherto dominant identities.

Costas Douzinas is Professor of Law and Director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, University of London.

- 1 Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Viking Press, 1965), 107.

- 2 B.L. Ullman, “What are the Humanities?” Journal of Higher Education 17/6 (1946), at 302.

- 3 H.C. Baldry, The Unity of Mankind in Greek Thought , (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1965), 201.

- 4 Ginés de Sepulveda, Democrates Segundo of De las Justas Causa de la Guerra contra los Indios (Madrid: Institute Fransisco de Vitoria, 1951), 33 quoted in Tzvetan Todorov, The Conquest of America trans. Richard Howard (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 153.

- 5 Bartholomé de las Casas, Obras Completas , Vol. 7 (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1922), 536–7.

- 6 Todorov, The Conquest of America 166, 168.

- 7 Slavoj Žižek, “Against Human Rights 56,” New Left Review (July–August 2005), 34.

- 8 Costas Douzinas, “For a Humanities of Resistance,” Critical Legal Thinking, December 7, 2010, https://www.criticallegalthinking.com/2010/12/07/for-a-humanities-of-resistance/

12 Comments

Good morning Costas! Does the problem lie, as you write, with “the idea of humanity”? Or does it instead lie with isolating and examining the history of ANY social or ethical concept in this step-by-step way? Is there any meaningful normative concept for which we can NOT perform the same kind of history, only to find that it, too, rests on millennia of manipulation, hierarchy and oppression? Suppose I do the same kind of geneology of the concept of “liberation”, or “tolerance”, or “cosmopolitanism”, or “open-mindedness”, or “love”, or “altruism”, or “empathy”, or “non-discrimination”, or “receptiveness”, or indeed even “revolution”. Won’t I obviously get the same kind of result? Does the history of a concept equate with some a priori meaning and necessary destiny? Are we no longer active agents over the concepts we use? Are we no longer able to intervene in history? Perhaps the concept of “human rights” collapses because ANY axiomatised ethical system collapses. Any ethics is always manipulable. Can we, or rather should we try, to imagine some “purer” one that isn’t? Isn’t “purity” the most manipulable notion of all? After Wittgenstein and Heidegger, can any analysis of such a deeply political concept as “humanity” really be plucked out and placed under a historical microscope in such a straightforward way? Is the problem, then, that any isolation of such a concept will inevitably deliver the same result, namely, a necessarily contingent history, which is then presented as a priori and unalterable? Doesn’t this style of analysis fall into the binarist trap it seeks to overcome, namely, of opposing a faulty concept to some un-stated assumption of an impeccable one, a “pure” one? I might even stray so far as to argue that injustice is not, as this analysis suggests, the opposite of justice, but rather its constant product. Hugs from Eric.

PS: As to the conclusion, “Perhaps the rights to come will be anthropic (to coin a term) rather than human, expressing and promoting singularities and differences instead of the sameness and equivalences of hitherto dominant identities.” But don’t countless philosophies promise to “express and promote singularities and differences instead of the sameness and equivalences.” (Some might call it the stock formula of run-of-the-mill liberalism!) How, then, will the “anthropic” avoid the fate of the “human” as narrated here? E

A small historical aside; in a legend recorded in Mesopotamian literature, the Akkadian king Naram Sin is engaged in a battle with the ‘Umman Manda’, incredibly powerful creatures of distinct physiognomy. Wondering if they are humans, he orders one of his officials to try and hit them to see if they bleed and are humans. Indeed, one of the proposed etymologies for their name is ‘humans? maybe’. I guess this shows how ancient is our preoccupation with ‘humanity’ and ‘human nature.’

IT IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER , ACCORDING TO HUMAN NATURE IT FULFILL ALL THINGS

And what of the ancient Greek word ἄνθρωπος?

“Humanity is civilization, anthropos is outside or before civilization.”

I don’t think that is how the Greeks used ἄνθρωπος at all. And what about the Greek concept of ‘mortals’ (βροτῶν), which includes men both inside and outside civilization. See Book 6 of the Odyssey (for example): ὤ μοι ἐγώ, τέων αὖτε βροτῶν ἐς γαῖαν ἱκάνω; ἦ ῥ᾽ οἵ γ᾽ ὑβρισταί τε καὶ ἄγριοι οὐδὲ δίκαιοι, ἦε φιλόξεινοι καί σφιν νόος ἐστὶ θεουδής;

Plato uses ἄνθρωπος a lot, but he certainly does NOT use it to mean ‘outside or before civilization’.

Can you give examples of where the Greeks used the word this way?

Dingus: Brilliant, and probative, point about Plato. I would argue that Plato has no real concept of “civilisation” at all, and certainly not in the way Aristotle does, or in the way early European modernity would later develop. Aristotle tells what we would today call an “Enlightenment narrative”, clearly referring to “primitive” and “advanced” stages of human society (with Greeks at the summit), and he repeats that point constantly. Plato, by contrast, tends to narrate history far more sceptically (or, as in Τίμαιος, cyclically).

Plato certainly (perhaps self-parodically) constructs notions of superior and inferior humans (infamously in Πολιτεία), but mostly in his oddly meritocratic scheme. He discusses differences between Greeks and non-Greeks, but never in Aristotle’s stringent, emphatic terms, nor does he really share Aristotle’s categorical notions of natural slaves. (Nor of women’s inferiority. After all, a woman can in theory become a philosopher ruler.)

And remember the “mere slave” who performs an extended dialectical operation in Μένων), of the type Plato thought appropriate only to philosophers. Curiously, then, Plato (even if he does pointedly ask whether that slave “speaks Greek”) does not so rigidly construct notions of humanity or civilisation in ethnic terms.

Thanks very much for your observation. Eric

I was thinking about the slave in Meno the other day. It’s a really remarkable and beautiful passage. I don’t think I understand the dialogue – or how that scene in particular fits into the whole corpus – but it would be a rich topic of research re: natural equality. It’s always unclear what Plato is actually saying and how much is ironic or eristic.

Really, the concept “Greek” is not really clear in a lot of ancient sources. It’s definitely non-existent in Homer. When Odysseus shows up somewhere, he doesn’t wonder ‘are they Greeks or not?’, he wonders if they are good to strangers and respect the gods (that is, civilization is defined ethically, not ethnically).

Hello again. I think there’s no doubt that Plato has a strong notion of dialectic as non-eristic (although we could certainly doubt its plausibility!), as emerges, for example, in the contrast with speech-making in Πρωταγόρας. Arguably the criticism of Plato in those “pure” dialectical passages is not against its dialectical artifice per se, but against its dialogical artifice — Socrates makes every point, and the interlocutor mostly just agrees (although I think that pattern does become a bit more complex in some passages in the other dialogues). So many have argued that Plato lacks any real notion of a participatory dialectic, i.e., that his dialectic is really just a monologue. That criticism will later come back to haunt figures as different as Aquinas, Hegel, and, I think, at least some of Marx.

Part of the significance of the slave in Μένων might have to do with Plato’s constant sarcasm about Athenian democracy, and its “free” citizens, having sacrificed any interest in truth-seeking (and therefore in justice), by throwing it open to a “mob” who, within that populist and market-driven context, merely end up seeking individual gain, and end up, so to speak, “lost to truth”, and “lost” to its primary tool, i.e., dialectic.

The character Socrates certainly has a strong notion of dialectic as non-eristic in some dialogues, but I’m hesitant to say what Plato’s position was. The way the dialogues are written seems to undermine the seemingly protreptic nature of the speeches. What do you make of the Euthydemus? Or the horribly unreliable narrator of the Symposium? It’s very unclear to me what Plato was doing.

In any case, the original blog post overstates its case against the Greeks and doesn’t provide evidence for its strong claims. I think it’s clear from Homer (to give one example) that there was an ancient conception of humanity that was not connected to ethnicity or ‘cultural superiority’. The split was between mortals and gods or man and beast. Even the Phaeacians, who are totally cut off from other people and compared to the Cyclops and Giants, are considered part of humanity.

Another (related) question is: how “Platonic” or “Aristotelian” was ancient Athens? How accepted were their ideas? There probably isn’t enough evidence to say.

What I do think is clear is that the ancient world – indeed, even Aristotle himself – was not “Aristotelian” in the same way as his Medieval followers (either Christian or Islamic).

G’morning again. Many 5th century Athenians certainly become chauvinist after the Persian wars. But with important dissenters. Plato, and probably Socrates, pokes fun at Athenian supremicism. They ironise it and parody it. And Plato, like Thucydides, certainly warns against its dangers, even seeing in it a crucial cause of Athens’s demise. Plato’s refusal to qualify Athenians, or even Greeks, as superior, in the categorical way that Aristotle does, is certainly no oversight.

(PS — I certainly agree that Plato and Aristotle do not play the role in Athens that they would later play in the Middle Ages, either in influence or in substance. The staunch democratic faction of Anytus and Meletus would have fallen dumbstruck reading Augustine and Aquinas!).

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Submit Comment

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Facebook 14k Followers

- Twitter 5k Followers

POSTS BY EMAIL

Email Address

We respect your privacy .

FAIR ACCESS* PUBLISHER IN LAW AND THE HUMANITIES

*fair access = access according to ability to pay on a sliding scale down to zero.

JUST PUBLISHED

PUBLISH ON CLT

Publish your article with us and get read by the largest community of critical legal scholars, with over 4500 subscribers.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Human Trafficking — Thesis Statement for Human Trafficking

Thesis Statement for Human Trafficking

- Categories: Human Trafficking

About this sample

Words: 612 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 612 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Prevalence of human trafficking, causes of human trafficking, impact on victims, measures to combat human trafficking.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 861 words

3 pages / 1267 words

3 pages / 1430 words

3 pages / 1531 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a modern-day form of slavery that involves the illegal trade of human beings for exploitation or commercial gain. It is a grave violation of human rights that affects millions of people around the world, [...]

International Labor Organization. (2020). Global Estimates of Child Labour: Results and trends, 2012-2016. ILO.Public Safety Canada. (n.d.). Human Trafficking. [...]

The term forced labor is often associated with historical atrocities, but unfortunately, it remains a pervasive issue in the modern world. This essay delves into the complex and distressing phenomenon of forced labor, examining [...]

Sex trafficking is a global issue that has gained significant attention in recent years. It involves the exploitation of individuals, primarily women and children, for the purpose of forced labor, sexual exploitation, and other [...]

Child trafficking is a devastating reality that plagues our society, robbing innocent children of their basic human rights and exploiting their vulnerability for profit. It is a cruel and heinous crime that must be addressed [...]

Throughout history millions of people have been denied basic human rights. In the 21st century it is now known as modern day slavery. Modern day slavery is “holding someone in compelled service, treating people like objects, or [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.3: Outlining

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4540

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Identify the steps in constructing an outline

- Construct a topic outline and a sentence outline

Your prewriting activities and readings have helped you gather information for your assignment. The more you sort through the pieces of information you found, the more you will begin to see the connections between them. Patterns and gaps may begin to stand out. But only when you start to organize your ideas will you be able to translate your raw insights into a form that will communicate meaning to your audience.

Longer papers require more reading and planning than shorter papers do. Most writers discover that the more they know about a topic, the more they can write about it with intelligence and interest.

Organizing Ideas

When you write, you need to organize your ideas in an order that makes sense. The writing you complete in all your courses exposes how analytically and critically your mind works. In some courses, the only direct contact you may have with your instructor is through the assignments you write for the course. You can make a good impression by spending time ordering your ideas.

Order refers to your choice of what to present first, second, third, and so on in your writing. The order you pick closely relates to your purpose for writing that particular assignment. For example, when telling a story, it may be important to first describe the background for the action. Or you may need to first describe a 3-D movie projector or a television studio to help readers visualize the setting and scene. You may want to group your supporting ideas effectively to convince readers that your point of view on an issue is well reasoned and worthy of belief.

In longer pieces of writing, you may organize different parts in different ways so that your purpose stands out clearly and all parts of the essay work together to consistently develop your main point.

Methods of Organizing Writing

The three common methods of organizing writing are chronological order, spatial order, and order of importance, which you learned about in Chapter 4 You need to keep these methods of organization in mind as you plan how to arrange the information you have gathered in an outline. An outline is a written plan that serves as a skeleton for the paragraphs you write. Later, when you draft paragraphs in the next stage of the writing process, you will add support to create “flesh” and “muscle” for your assignment.

When you write, your goal is not only to complete an assignment but also to write for a specific purpose—perhaps to inform, to explain, to persuade, or a combination of these purposes. Your purpose for writing should always be in the back of your mind, because it will help you decide which pieces of information belong together and how you will order them. In other words, choose the order that will most effectively fit your purpose and support your main point.

Table 5.2: Order versus Purpose shows the connection between order and purpose.

Writing an Outline

For an essay question on a test or a brief oral presentation in class, all you may need to prepare is a short, informal outline in which you jot down key ideas in the order you will present them. This kind of outline reminds you to stay focused in a stressful situation and to include all the good ideas that help you explain or prove your point. For a longer assignment, like an essay or a research paper, many instructors will require you to submit a formal outline before writing a major paper as a way of making sure you are on the right track and are working in an organized manner. The expectation is you will build your paper based on the framework created by the outline.

When creating outlines, writers generally go through three stages: a scratch outline , an informal or topic outline , and a formal or sentence outline. The scratch outline is basically generated by taking what you have come up with in your freewriting process and organizing the information into a structure that is easy for you to understand and follow (for example, a mind map or hierarchical outline). An informal outline goes a step further and adds topic sentences, a thesis, and some preliminary information you have found through research. A formal outline is a detailed guide that shows how all your supporting ideas relate to each other. It helps you distinguish between ideas that are of equal importance and ones that are of lesser importance. If your instructor asks you to submit an outline for approval, you will want to hand in one that is more formal and structured. The more information you provide for your instructor, the better he or she will be able to see the direction in which you plan to go for your discussion and give you better feedback.

Instructors may also require you to submit an outline with your final draft to check the direction and logic of the assignment. If you are required to submit an outline with the final draft of a paper, remember to revise it to reflect any changes you made while writing the paper.

There are two types of formal outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline . You format both types of formal outlines in the same way.

Place your introduction and thesis statement at the beginning, under Roman numeral I.

Use Roman numerals (II, III, IV, V, etc.) to identify main points that develop the thesis statement.

Use capital letters (A, B, C, D, etc.) to divide your main points into parts.

Use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) if you need to subdivide any As, Bs, or Cs into smaller parts.

End with the final Roman numeral expressing your idea for your conclusion.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

1) Introduction

Thesis statement

2) Main point 1 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

3) Main point 2 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2 [same use of subpoints as with Main point 1]

- Supporting detail

4) Main point 3 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3[same use of subpoints as with Main points 1&2]

5) Conclusion

In an outline, any supporting detail can be developed with subpoints. For simplicity, the model shows subpoints only under the first main point.

Formal outlines are often quite rigid in their organization. As many instructors will specify, you cannot subdivide one point if it is only one part. For example, for every Roman numeral I, there needs to be an A. For every A, there must be a B. For every Arabic numeral 1, there must be a 2. See for yourself on the sample outlines that follow.

Constructing Informal or Topic Outlines An informal topic outline is the same as a sentence outline except you use words or phrases instead of complete sentences. Words and phrases keep the outline short and easier to comprehend. All the headings, however, must be written in parallel structure.

Here is the informal topic outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing. Her purpose is to inform, and her audience is a general audience of her fellow college students. Notice how Mariah begins with her thesis statement. She then arranges her main points and supporting details in outline form using short phrases in parallel grammatical structure.

Checklist 5.2 : Writing an Effective Topic Outline

This checklist can help you write an effective topic outline for your assignment. It will also help you discover where you may need to do additional reading or prewriting.

Do I have a controlling idea that guides the development of the entire piece of writing?

Do I have three or more main points that I want to make in this piece of writing? Does each main point connect to my controlling idea?

Is my outline in the best order—chronological order, spatial order, or order of importance—for me to present my main points? Will this order help me get my main point across?

Do I have supporting details that will help me inform, explain, or prove my main points?

Do I need to add more support? If so, where?

Do I need to make any adjustments in my working thesis statement before I consider it the final version?

Writing at Work

Word processing programs generally have an automatic numbering feature that can be used to prepare outlines. This feature automatically sets indents and lets you use the tab key to arrange information just as you would in an outline. Although in business this style might be acceptable, in college or university your instructor might have different requirements. Teach yourself how to customize the levels of outline numbering in your word processing program to fit your instructor’s preferences.

Exercise 5.8

Using the working thesis statement you wrote in Exercise 5 . 3 and the reading you did in Section 5.1: Apply Prewriting Models , construct a topic outline for your essay. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and Arabic numerals and capital letters.

Collaboration: P lease share with a classmate and compare your outline. Point out areas of interest from your classmate’s outline and what you would like to learn more about.

Exercise 5.9

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration: P lease share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Constructing Formal or Sentence Outlines

A sentence outline is the same as a topic outline except you use complete sentences instead of words or phrases. Complete sentences create clarity and can advance you one step closer to a draft in the writing process.

Here is the formal sentence outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing.

The information compiled under each Roman numeral will become a paragraph in your final paper. Mariah’s outline follows the standard five-paragraph essay arrangement, but longer essays will require more paragraphs and thus more Roman numerals. If you think that a paragraph might become too long, add an additional paragraph to your outline, renumbering the main points appropriately.

As you are building on your previously created outlines, avoid saving over the previous version; instead, save the revised outline under a new file name. This way you will still have a copy of the original and any earlier versions in case you want to look back at them.