Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight

Wonderful discussion. and yes, homework helps in learning and building skills in students.

not true it just causes kids to stress

Homework can be both beneficial and unuseful, if you will. There are students who are gifted in all subjects in school and ones with disabilities. Why should the students who are gifted get the lucky break, whereas the people who have disabilities suffer? The people who were born with this “gift” go through school with ease whereas people with disabilities struggle with the work given to them. I speak from experience because I am one of those students: the ones with disabilities. Homework doesn’t benefit “us”, it only tears us down and put us in an abyss of confusion and stress and hopelessness because we can’t learn as fast as others. Or we can’t handle the amount of work given whereas the gifted students go through it with ease. It just brings us down and makes us feel lost; because no mater what, it feels like we are destined to fail. It feels like we weren’t “cut out” for success.

homework does help

here is the thing though, if a child is shoved in the face with a whole ton of homework that isn’t really even considered homework it is assignments, it’s not helpful. the teacher should make homework more of a fun learning experience rather than something that is dreaded

This article was wonderful, I am going to ask my teachers about extra, or at all giving homework.

I agree. Especially when you have homework before an exam. Which is distasteful as you’ll need that time to study. It doesn’t make any sense, nor does us doing homework really matters as It’s just facts thrown at us.

Homework is too severe and is just too much for students, schools need to decrease the amount of homework. When teachers assign homework they forget that the students have other classes that give them the same amount of homework each day. Students need to work on social skills and life skills.

I disagree.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what’s going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Homework is helpful because homework helps us by teaching us how to learn a specific topic.

As a student myself, I can say that I have almost never gotten the full 9 hours of recommended sleep time, because of homework. (Now I’m writing an essay on it in the middle of the night D=)

I am a 10 year old kid doing a report about “Is homework good or bad” for homework before i was going to do homework is bad but the sources from this site changed my mind!

Homeowkr is god for stusenrs

I agree with hunter because homework can be so stressful especially with this whole covid thing no one has time for homework and every one just wants to get back to there normal lives it is especially stressful when you go on a 2 week vaca 3 weeks into the new school year and and then less then a week after you come back from the vaca you are out for over a month because of covid and you have no way to get the assignment done and turned in

As great as homework is said to be in the is article, I feel like the viewpoint of the students was left out. Every where I go on the internet researching about this topic it almost always has interviews from teachers, professors, and the like. However isn’t that a little biased? Of course teachers are going to be for homework, they’re not the ones that have to stay up past midnight completing the homework from not just one class, but all of them. I just feel like this site is one-sided and you should include what the students of today think of spending four hours every night completing 6-8 classes worth of work.

Are we talking about homework or practice? Those are two very different things and can result in different outcomes.

Homework is a graded assignment. I do not know of research showing the benefits of graded assignments going home.

Practice; however, can be extremely beneficial, especially if there is some sort of feedback (not a grade but feedback). That feedback can come from the teacher, another student or even an automated grading program.

As a former band director, I assigned daily practice. I never once thought it would be appropriate for me to require the students to turn in a recording of their practice for me to grade. Instead, I had in-class assignments/assessments that were graded and directly related to the practice assigned.

I would really like to read articles on “homework” that truly distinguish between the two.

oof i feel bad good luck!

thank you guys for the artical because I have to finish an assingment. yes i did cite it but just thanks

thx for the article guys.

Homework is good

I think homework is helpful AND harmful. Sometimes u can’t get sleep bc of homework but it helps u practice for school too so idk.

I agree with this Article. And does anyone know when this was published. I would like to know.

It was published FEb 19, 2019.

Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college.

i think homework can help kids but at the same time not help kids

This article is so out of touch with majority of homes it would be laughable if it wasn’t so incredibly sad.

There is no value to homework all it does is add stress to already stressed homes. Parents or adults magically having the time or energy to shepherd kids through homework is dome sort of 1950’s fantasy.

What lala land do these teachers live in?

Homework gives noting to the kid

Homework is Bad

homework is bad.

why do kids even have homework?

Comments are closed.

Latest from Bostonia

Could boston be the next city to impose congestion pricing, alum has traveled the world to witness total solar eclipses, opening doors: rhonda harrison (eng’98,’04, grs’04), campus reacts and responds to israel-hamas war, reading list: what the pandemic revealed, remembering com’s david anable, cas’ john stone, “intellectual brilliance and brilliant kindness”, one good deed: christine kannler (cas’96, sph’00, camed’00), william fairfield warren society inducts new members, spreading art appreciation, restoring the “black angels” to medical history, in the kitchen with jacques pépin, feedback: readers weigh in on bu’s new president, com’s new expert on misinformation, and what’s really dividing the nation, the gifts of great teaching, sth’s walter fluker honored by roosevelt institute, alum’s debut book is a ramadan story for children, my big idea: covering construction sites with art, former terriers power new professional women’s hockey league, five trailblazing alums to celebrate during women’s history month, alum beata coloyan is boston mayor michelle wu’s “eyes and ears” in boston neighborhoods.

Are You Down With or Done With Homework?

- Posted January 17, 2012

- By Lory Hough

The debate over how much schoolwork students should be doing at home has flared again, with one side saying it's too much, the other side saying in our competitive world, it's just not enough.

It was a move that doesn't happen very often in American public schools: The principal got rid of homework.

This past September, Stephanie Brant, principal of Gaithersburg Elementary School in Gaithersburg, Md., decided that instead of teachers sending kids home with math worksheets and spelling flash cards, students would instead go home and read. Every day for 30 minutes, more if they had time or the inclination, with parents or on their own.

"I knew this would be a big shift for my community," she says. But she also strongly believed it was a necessary one. Twenty-first-century learners, especially those in elementary school, need to think critically and understand their own learning — not spend night after night doing rote homework drills.

Brant's move may not be common, but she isn't alone in her questioning. The value of doing schoolwork at home has gone in and out of fashion in the United States among educators, policymakers, the media, and, more recently, parents. As far back as the late 1800s, with the rise of the Progressive Era, doctors such as Joseph Mayer Rice began pushing for a limit on what he called "mechanical homework," saying it caused childhood nervous conditions and eyestrain. Around that time, the then-influential Ladies Home Journal began publishing a series of anti-homework articles, stating that five hours of brain work a day was "the most we should ask of our children," and that homework was an intrusion on family life. In response, states like California passed laws abolishing homework for students under a certain age.

But, as is often the case with education, the tide eventually turned. After the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, a space race emerged, and, writes Brian Gill in the journal Theory Into Practice, "The homework problem was reconceived as part of a national crisis; the U.S. was losing the Cold War because Russian children were smarter." Many earlier laws limiting homework were abolished, and the longterm trend toward less homework came to an end.

The debate re-emerged a decade later when parents of the late '60s and '70s argued that children should be free to play and explore — similar anti-homework wellness arguments echoed nearly a century earlier. By the early-1980s, however, the pendulum swung again with the publication of A Nation at Risk , which blamed poor education for a "rising tide of mediocrity." Students needed to work harder, the report said, and one way to do this was more homework.

For the most part, this pro-homework sentiment is still going strong today, in part because of mandatory testing and continued economic concerns about the nation's competitiveness. Many believe that today's students are falling behind their peers in places like Korea and Finland and are paying more attention to Angry Birds than to ancient Babylonia.

But there are also a growing number of Stephanie Brants out there, educators and parents who believe that students are stressed and missing out on valuable family time. Students, they say, particularly younger students who have seen a rise in the amount of take-home work and already put in a six- to nine-hour "work" day, need less, not more homework.

Who is right? Are students not working hard enough or is homework not working for them? Here's where the story gets a little tricky: It depends on whom you ask and what research you're looking at. As Cathy Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework , points out, "Homework has generated enough research so that a study can be found to support almost any position, as long as conflicting studies are ignored." Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement. In other words, it's hard to tease out how homework is really affecting test scores and grades. Did one teacher give better homework than another? Was one teacher more effective in the classroom? Do certain students test better or just try harder?

"It is difficult to separate where the effect of classroom teaching ends," Vatterott writes, "and the effect of homework begins."

Putting research aside, however, much of the current debate over homework is focused less on how homework affects academic achievement and more on time. Parents in particular have been saying that the amount of time children spend in school, especially with afterschool programs, combined with the amount of homework given — as early as kindergarten — is leaving students with little time to run around, eat dinner with their families, or even get enough sleep.

Certainly, for some parents, homework is a way to stay connected to their children's learning. But for others, homework creates a tug-of-war between parents and children, says Liz Goodenough, M.A.T.'71, creator of a documentary called Where Do the Children Play?

"Ideally homework should be about taking something home, spending a few curious and interesting moments in which children might engage with parents, and then getting that project back to school — an organizational triumph," she says. "A nag-free activity could engage family time: Ask a parent about his or her own childhood. Interview siblings."

Instead, as the authors of The Case Against Homework write, "Homework overload is turning many of us into the types of parents we never wanted to be: nags, bribers, and taskmasters."

Leslie Butchko saw it happen a few years ago when her son started sixth grade in the Santa Monica-Malibu (Calif.) United School District. She remembers him getting two to four hours of homework a night, plus weekend and vacation projects. He was overwhelmed and struggled to finish assignments, especially on nights when he also had an extracurricular activity.

"Ultimately, we felt compelled to have Bobby quit karate — he's a black belt — to allow more time for homework," she says. And then, with all of their attention focused on Bobby's homework, she and her husband started sending their youngest to his room so that Bobby could focus. "One day, my younger son gave us 15-minute coupons as a present for us to use to send him to play in the back room. … It was then that we realized there had to be something wrong with the amount of homework we were facing."

Butchko joined forces with another mother who was having similar struggles and ultimately helped get the homework policy in her district changed, limiting homework on weekends and holidays, setting time guidelines for daily homework, and broadening the definition of homework to include projects and studying for tests. As she told the school board at one meeting when the policy was first being discussed, "In closing, I just want to say that I had more free time at Harvard Law School than my son has in middle school, and that is not in the best interests of our children."

One barrier that Butchko had to overcome initially was convincing many teachers and parents that more homework doesn't necessarily equal rigor.

"Most of the parents that were against the homework policy felt that students need a large quantity of homework to prepare them for the rigorous AP classes in high school and to get them into Harvard," she says.

Stephanie Conklin, Ed.M.'06, sees this at Another Course to College, the Boston pilot school where she teaches math. "When a student is not completing [his or her] homework, parents usually are frustrated by this and agree with me that homework is an important part of their child's learning," she says.

As Timothy Jarman, Ed.M.'10, a ninth-grade English teacher at Eugene Ashley High School in Wilmington, N.C., says, "Parents think it is strange when their children are not assigned a substantial amount of homework."

That's because, writes Vatterott, in her chapter, "The Cult(ure) of Homework," the concept of homework "has become so engrained in U.S. culture that the word homework is part of the common vernacular."

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn.

"Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week). … This commitment to the idea of homework in the abstract is accepted by the overwhelming majority of schools — public and private, elementary and secondary."

Brant had to confront this when she cut homework at Gaithersburg Elementary.

"A lot of my parents have this idea that homework is part of life. This is what I had to do when I was young," she says, and so, too, will our kids. "So I had to shift their thinking." She did this slowly, first by asking her teachers last year to really think about what they were sending home. And this year, in addition to forming a parent advisory group around the issue, she also holds events to answer questions.

Still, not everyone is convinced that homework as a given is a bad thing. "Any pursuit of excellence, be it in sports, the arts, or academics, requires hard work. That our culture finds it okay for kids to spend hours a day in a sport but not equal time on academics is part of the problem," wrote one pro-homework parent on the blog for the documentary Race to Nowhere , which looks at the stress American students are under. "Homework has always been an issue for parents and children. It is now and it was 20 years ago. I think when people decide to have children that it is their responsibility to educate them," wrote another.

And part of educating them, some believe, is helping them develop skills they will eventually need in adulthood. "Homework can help students develop study skills that will be of value even after they leave school," reads a publication on the U.S. Department of Education website called Homework Tips for Parents. "It can teach them that learning takes place anywhere, not just in the classroom. … It can foster positive character traits such as independence and responsibility. Homework can teach children how to manage time."

Annie Brown, Ed.M.'01, feels this is particularly critical at less affluent schools like the ones she has worked at in Boston, Cambridge, Mass., and Los Angeles as a literacy coach.

"It feels important that my students do homework because they will ultimately be competing for college placement and jobs with students who have done homework and have developed a work ethic," she says. "Also it will get them ready for independently taking responsibility for their learning, which will need to happen for them to go to college."

The problem with this thinking, writes Vatterott, is that homework becomes a way to practice being a worker.

"Which begs the question," she writes. "Is our job as educators to produce learners or workers?"

Slate magazine editor Emily Bazelon, in a piece about homework, says this makes no sense for younger kids.

"Why should we think that practicing homework in first grade will make you better at doing it in middle school?" she writes. "Doesn't the opposite seem equally plausible: that it's counterproductive to ask children to sit down and work at night before they're developmentally ready because you'll just make them tired and cross?"

Kohn writes in the American School Board Journal that this "premature exposure" to practices like homework (and sit-and-listen lessons and tests) "are clearly a bad match for younger children and of questionable value at any age." He calls it BGUTI: Better Get Used to It. "The logic here is that we have to prepare you for the bad things that are going to be done to you later … by doing them to you now."

According to a recent University of Michigan study, daily homework for six- to eight-year-olds increased on average from about 8 minutes in 1981 to 22 minutes in 2003. A review of research by Duke University Professor Harris Cooper found that for elementary school students, "the average correlation between time spent on homework and achievement … hovered around zero."

So should homework be eliminated? Of course not, say many Ed School graduates who are teaching. Not only would students not have time for essays and long projects, but also teachers would not be able to get all students to grade level or to cover critical material, says Brett Pangburn, Ed.M.'06, a sixth-grade English teacher at Excel Academy Charter School in Boston. Still, he says, homework has to be relevant.

"Kids need to practice the skills being taught in class, especially where, like the kids I teach at Excel, they are behind and need to catch up," he says. "Our results at Excel have demonstrated that kids can catch up and view themselves as in control of their academic futures, but this requires hard work, and homework is a part of it."

Ed School Professor Howard Gardner basically agrees.

"America and Americans lurch between too little homework in many of our schools to an excess of homework in our most competitive environments — Li'l Abner vs. Tiger Mother," he says. "Neither approach makes sense. Homework should build on what happens in class, consolidating skills and helping students to answer new questions."

So how can schools come to a happy medium, a way that allows teachers to cover everything they need while not overwhelming students? Conklin says she often gives online math assignments that act as labs and students have two or three days to complete them, including some in-class time. Students at Pangburn's school have a 50-minute silent period during regular school hours where homework can be started, and where teachers pull individual or small groups of students aside for tutoring, often on that night's homework. Afterschool homework clubs can help.

Some schools and districts have adapted time limits rather than nix homework completely, with the 10-minute per grade rule being the standard — 10 minutes a night for first-graders, 30 minutes for third-graders, and so on. (This remedy, however, is often met with mixed results since not all students work at the same pace.) Other schools offer an extended day that allows teachers to cover more material in school, in turn requiring fewer take-home assignments. And for others, like Stephanie Brant's elementary school in Maryland, more reading with a few targeted project assignments has been the answer.

"The routine of reading is so much more important than the routine of homework," she says. "Let's have kids reflect. You can still have the routine and you can still have your workspace, but now it's for reading. I often say to parents, if we can put a man on the moon, we can put a man or woman on Mars and that person is now a second-grader. We don't know what skills that person will need. At the end of the day, we have to feel confident that we're giving them something they can use on Mars."

Read a January 2014 update.

Homework Policy Still Going Strong

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Commencement Marshal Sarah Fiarman: The Principal of the Matter

Making Math “Almost Fun”

Alum develops curriculum to entice reluctant math learners

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

Advertisement

Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 January 2021

- Volume 50 , pages 631–651, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Melissa Holland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8349-7168 1 ,

- McKenzie Courtney 2 ,

- James Vergara 3 ,

- Danielle McIntyre 4 ,

- Samantha Nix 5 ,

- Allison Marion 6 &

- Gagan Shergill 1

18k Accesses

8 Citations

127 Altmetric

16 Mentions

Explore all metrics

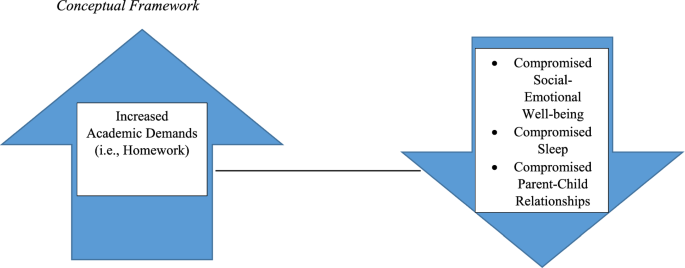

Increasing academic demands, including larger amounts of assigned homework, is correlated with various challenges for children. While homework stress in middle and high school has been studied, research evidence is scant concerning the effects of homework on elementary-aged children.

The objective of this study was to understand rater perception of the purpose of homework, the existence of homework policy, and the relationship, if any, between homework and the emotional health, sleep habits, and parent–child relationships for children in grades 3–6.

Survey research was conducted in the schools examining student ( n = 397), parent ( n = 442), and teacher ( n = 28) perception of homework, including purpose, existing policy, and the childrens’ social and emotional well-being.

Preliminary findings from teacher, parent, and student surveys suggest the presence of modest impact of homework in the area of emotional health (namely, student report of boredom and frustration ), parent–child relationships (with over 25% of the parent and child samples reporting homework always or often interferes with family time and creates a power struggle ), and sleep (36.8% of the children surveyed reported they sometimes get less sleep) in grades 3–6. Additionally, findings suggest misperceptions surrounding the existence of homework policies among parents and teachers, the reasons teachers cite assigning homework, and a disconnect between child-reported and teacher reported emotional impact of homework.

Conclusions

Preliminary findings suggest homework modestly impacts child well-being in various domains in grades 3–6, including sleep, emotional health, and parent/child relationships. School districts, educators, and parents must continue to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support children’s overall well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding the Quality of Effective Homework

Relationships between perceived parental involvement in homework, student homework behaviors, and academic achievement: differences among elementary, junior high, and high school students.

J. C. Núñez, N. Suárez, … J. L. Epstein

Collaboration between School and Home to Improve Subjective Well-being: A New Chinese Children’s Subjective Well-being Scale

Meijie Chu, Zhiwei Fang, … Yi-Chen Chiang

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s social-emotional health is moving to the forefront of attention in schools, as depression, anxiety, and suicide rates are on the rise (Bitsko et al. 2018 ; Child Mind Institute 2016 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Perou et al. 2013 ). This comes at a time when there are also intense academic demands, including an increased focus on academic achievement via grades, standardized test scores, and larger amounts of assigned homework (Pope 2010 ). This interplay between the rise in anxiety and depression and scholastic demands has been postulated upon frequently in the literature, and though some research has looked at homework stress as it relates to middle and high school students (Cech 2008 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Kackar et al. 2011 ; Katz et al. 2012 ), research evidence is scant as to the effects of academic stress on the social and emotional health of elementary children.

Literature Review

The following review of the literature highlights areas that are most pertinent to the child, including homework as it relates to achievement, the achievement gap, mental health, sleep, and parent–child relationships. Areas of educational policy, teacher training, homework policy, and parent-teacher communication around homework are also explored.

Homework and Achievement

With the authorization of No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards, teachers have felt added pressures to keep up with the tougher standards movement (Tokarski 2011 ). Additionally, teachers report homework is necessary in order to complete state-mandated material (Holte 2015 ). Misconceptions on the effectiveness of homework and student achievement have led many teachers to increase the amount of homework assigned. However, there has been little evidence to support this trend. In fact, there is a significant body of research demonstrating the lack of correlation between homework and student success, particularly at the elementary level. In a meta-analysis examining homework, grades, and standardized test scores, Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) found little correlation between the amount of homework assigned and achievement in elementary school, and only a moderate correlation in middle school. In third grade and below, there was a negative correlation found between the variables ( r = − 0.04). Other studies, too, have evidenced no relationship, and even a negative relationship in some grades, between the amount of time spent on homework and academic achievement (Horsley and Walker 2013 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ). High levels of homework in competitive high schools were found to hinder learning, full academic engagement, and well-being (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Ironically, research suggests that reducing academic pressures can actually increase children’s academic success and cognitive abilities (American Psychological Association [APA] 2014 ).

International comparison studies of achievement show that national achievement is higher in countries that assign less homework (Baines and Slutsky 2009 ; Güven and Akçay 2019 ). In fact, in a recent international study conducted by Güven and Akçay ( 2019 ), there was no relationship found between math homework frequency and student achievement for fourth grade students in the majority of the countries studied, including the United States. Similarly, additional homework in science, English, and history was found to have little to no impact on respective test scores in later grades (Eren and Henderson 2011 ). In the 2015 “Programme of International Student Assessment” results, Korea and Finland are ranked among the top countries in reading, mathematics, and writing, yet these countries are among those that assign the least amount of homework (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2016 ).

Homework and Mental Wellness

Academic stress has been found to play a role in the mental well-being of children. In a study conducted by Conner et al. ( 2009 ), students reported feeling overwhelmed and burdened by their exceeding homework loads, even when they viewed homework as meaningful. Academic stress, specifically the amount of homework assigned, has been identified as a common risk factor for children’s increased anxiety levels (APA 2009 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Leung et al. 2010 ), in addition to somatic complaints and sleep disturbance (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Stress also negatively impacts cognition, including memory, executive functioning, motor skills, and immune response (Westheimer et al. 2011 ). Consequently, excessive stress impacts one’s ability to think critically, recall information, and make decisions (Carrion and Wong 2012 ).

Homework and Sleep

Sleep, including quantity and quality, is one life domain commonly impacted by homework and stress. Zhou et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors in school-aged children, with findings suggesting that staying up late to study was one of the leading risk factors most associated with severe tiredness and depression. According to the National Sleep Foundation ( 2017 ), the recommended amount of sleep for elementary school-aged children is 9 – 11 h per night; however, approximately 70% of youth do not get these recommended hours. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), elementary-aged children also acknowledge lack of sleep. Perfect et al. ( 2014 ) found that sleep problems predict lower grades and negative student attitudes toward teachers and school. Eide and Showalter ( 2012 ) conducted a national study that examined the relationship between optimum amounts of sleep and student performance on standardized tests, with results indicating significant correlations ( r = 0.285–0.593) between sleep and student performance. Therefore, sleep is not only impacted by academic stress and homework, but lack of sleep can also impact academic functioning.

Homework and the Achievement Gap

Homework creates increasing achievement variability among privileged learners and those who are not. For example, learners with more resources, increased parental education, and family support are likely to have higher achievement on homework (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; Moore et al. 2018 ; Ndebele 2015 ; OECD 2016 ). Learners coming from a lower socioeconomic status may not have access to quiet, well-lit environments, computers, and books necessary to complete their homework (Cooper 2001 ; Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Additionally, many homework assignments require materials that may be limited for some families, including supplies for projects, technology, and transportation. Based on the research to date, the phrase “the homework gap” has been coined to describe those learners who lack the resources necessary to complete assigned homework (Moore et al. 2018 ).

Parent–Teacher Communication Around Homework

Communication between caregivers and teachers is essential. Unfortunately, research suggests parents and teachers often have limited communication regarding homework assignments. Markow et al. ( 2007 ) found most parents (73%) report communicating with their child’s teacher regarding homework assignments less than once a month. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) indicated children in primary grades spend substantially more time on homework than predicted by educators. For example, they found first grade students had three times more homework than the National Education Association’s recommendation of up to 20 min of homework per night for first graders. While the same homework assignment may take some learners 30 min to complete, it may take others up to 2 or 3 h. However, until parents and teachers have better communication around homework, including time completion and learning styles for individual learners, these misperceptions and disparities will likely persist.

Parent–Child Relationships and Homework

Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) defined homework as a “double-edged sword” when it comes to the parent–child relationship. While some parental support can be construed as beneficial, parental support can also be experienced as intrusive or detrimental. When examining parental homework styles, a controlling approach was negatively associated with student effort and emotions toward homework (Trautwein et al. 2009 ). Research suggests that homework is a primary source of stress, power struggle, and disagreement among families (Cameron and Bartel 2009 ), with many families struggling with nightly homework battles, including serious arguments between parents and their children over homework (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). Often, parents are not only held accountable for monitoring homework completion, they may also be accountable for teaching, re-teaching, and providing materials. This is particularly challenging due to the economic and educational diversity of families. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) found that as parents’ personal perceptions of their abilities to assist their children with homework declined, family-related stressors increased.

Teacher Training

As homework plays a significant role in today’s public education system, an assumption would be made that teachers are trained to design homework tasks to promote learning. However, only 12% of teacher training programs prepare teachers for using homework as an assessment tool (Greenberg and Walsh 2012 ), and only one out of 300 teachers reported ever taking a course regarding homework during their training (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). The lack of training with regard to homework is evidenced by the differences in teachers’ perspectives. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), less experienced teachers (i.e., those with 5 years or less years of experience) are less likely to to believe homework is important and that homework supports student learning compared to more experienced teachers (i.e., those with 21 plus years of experience). There is no universal system or rule regarding homework; consequently, homework practices reflect individual teacher beliefs and school philosophies.

Educational and Homework Policy

Policy implementation occurs on a daily basis in public schools and classrooms. While some policies are made at the federal level, states, counties, school districts, and even individual school sites often manage education policy (Mullis et al. 2012 ). Thus, educators are left with the responsibility to implement multi-level policies, such as curriculum selection, curriculum standards, and disability policy (Rigby et al. 2016 ). Despite educational reforms occurring on an almost daily basis, little has been initiated with regard to homework policies and practices.

To date, few schools provide specific guidelines regarding homework practices. District policies that do exist are not typically driven by research, using vague terminology regarding the quantity and quality of assignments. Greater variations among homework practices exist when comparing schools in the private sector. For example, Montessori education practices the philosophy of no examinations and no homework for students aged 3–18 (O’Donnell 2013 ). Abeles and Rubenstein ( 2015 ) note that many public school districts advocate for the premise of 10 min of homework per night per grade level. However, there is no research supporting this premise and the guideline fails to recognize that time spent on homework varies based on the individual student. Sartain et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed and evaluated homework policies of multiple school districts, finding the policies examined were outdated, vague, and not student-focused.

The reasons cited for homework assignment, as identified by teachers, are varied, such as enhancing academic achievement through practice or teaching self-discipline. However, not all types of practice are equally effective, particularly if the student is practicing the skill incorrectly (Dean et al. 2012 ; Trautwein et al. 2009 ). The practice of reading is one of the only assignments consistently supported by research to be associated with increased academic achievement (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ). Current literature supports 15–20 min of daily allocated time for reading practice (Reutzel and Juth 2017 ). Additionally, research supports project-based learning to deepen learners’ practice and understanding of academic material (Williams 2018 ).

Research also shows that homework only teaches responsibility and self-discipline when parents have that goal in mind and systematically structure and supervise homework (Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Non-academic activities, such as participating in chores (University of Minnesota 2002 ) and sports (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ) were found to be greater predictors of later success and effective problem-solving.

Consistent with the pre-existing research literature, the following hypotheses are offered:

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s social-emotional well-being.

The purposes cited for the assignment of homework will be varied between parents and teachers.

Schools will lack well-formulated and understood homework policies.

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s sleep and parent–child relationships.

This quantitative study explored, via perception-based survey research, the social and emotional health of elementary children in grades 3 – 6 and the scholastic pressures they face, namely homework. The researchers implemented newly developed questionnaires addressing student, teacher, and parent perspectives on homework and on children’s social-emotional well-being. Researchers also examined perspectives on the purpose of homework, the existence of school homework policies, and the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and family relationships. Given the dearth of prior research in this area, a major goal of this study was to explore associations between academic demands and child well-being with sufficient breadth to allow for identification of potential associations that may be examined more thoroughly by future research. These preliminary associations and item-response tendencies can serve as foundation for future studies with causal, experimental, or more psychometrically focused designs. A conceptual framework for this study is offered in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework

Research Questions

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and the children themselves?

What are the primary purposes of homework according to parents and teachers?

How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?

The present quantitative descriptive study is based on researcher developed instruments designed to explore the perceptions of children, teachers and parents on homework and its impact on social-emotional well-being. The use of previously untested instruments and a convenience sample preclude any causal interpretations being drawn from our results. This study is primarily an initial foray into the sparsely researched area of the relationship of homework and social-emotional health, examining an elementary school sample and incorporating multiple perspectives of the parents, teachers, and the children themselves.

Participants

The participants in this study were children in six Northern California schools in grades third through sixth ( n = 397), their parents ( n = 442), and their teachers ( n = 28). The mean grade among children was 4.56 (minimum third grade/maximum sixth grade) with a mean age of 9.97 (minimum 8 years old/maximum 12 years old). Approximately 54% of the children were male and 45% were female, with White being the most common ethnicity (61%), followed by Hispanic (30%), and Pacific Islander (12%). Subjects were able to mark more than one ethnicity. Detailed participant demographics are available upon request.

Instruments

The instruments used in this research include newly developed student, parent, and teacher surveys. The research team formulated a number of survey items that, based on existing research and their own professional experience in the schools, have high face validity in measuring workload, policies, and attitudes surrounding homework. Further psychometric development of these surveys and ascertation of construct and content validity is warranted, with the first step being their use in this initial perception-based study. Each of the surveys, developed specifically for this study, are discussed below.

Student Survey

The Student Survey is a 15-item questionnaire wherein the child was asked closed- and open-ended questions regarding their perspectives on homework, including how homework makes them feel.

Parent Survey

The Parent Survey is a 23-item questionnaire wherein the children’s parents were asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives on their child’s homework, as well as their child’s social-emotional health. Additionally, parents were asked whether their child’s school has a homework policy and, if so, if they know what that policy specifies.

Teacher Survey

The Teacher Survey is a 22-item questionnaire wherein the children’s teacher was asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives of the primary purposes of homework, as well as the impact of homework on children’s social-emotional health. Additionally, teachers were asked whether their school has a homework policy and, if so, what that policy specifies.

Data was collected by the researchers after following Institutional Review Board procedures from the sponsoring university. School district approval was obtained by the lead researcher. Upon district approval, individual school approval was requested by the researchers by contacting site principals, after which, teachers of grades 3 – 6 at those schools were asked to voluntarily participate. Each participating teacher was provided a packet including the following: a manila envelope, Teacher Instructions, Administration Guide, Teacher Survey, Parent Packet, and Student Survey. Surveys and classrooms were de-identified via number assignment. Teachers then distributed the Parent Packet to each child’s guardian, which included the Parent Consent and Parent Survey, corresponding with the child’s assigned number. A coded envelope was also enclosed for parents/guardians to return their completed consent form and survey, if they agreed to participate. The Parent Consent form detailed the purpose of the research, the benefits and risks of participating in the research, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of completing the survey. Parents who completed the consent form and survey sent the completed materials in the enclosed envelope, sealed, to their child’s teacher. After obtaining returned envelopes, with parent consent, teachers were instructed to administer the corresponding numbered survey to the children during a class period. Teachers were also asked to complete their Teacher Survey. All completed materials were to be placed in envelopes provided to each teacher and returned to the researchers once data was collected.

Analysis of Data

This descriptive and quantitative research design utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to analyze data. The researchers developed coding keys for the parent, teacher, and student surveys to facilitate data entry into SPSS. Items were also coded based on the type of data, such as nominal or ordinal, and qualitative responses were coded and translated where applicable and transcribed onto a response sheet. Some variables were transformed for more accurate comparison across raters. Parent, teacher, and student ratings were analyzed, and frequency counts and percentages were generated for each item. Items were then compared across and within rater groups to explore the research questions. The data analysis of this study is primarily descriptive and exploratory, not seeking to imply causal relationships between variables. Survey item response results associated with each research questionnaire are summarized in their respective sections below.

The first research question investigated in this study was: “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and children?” For this question the examiners looked at children’s responses to how homework makes them feel from a list of feelings. As demonstrated in Table 1 , approximately 44% of children feel “Bored” and about 25% feel “Annoyed” and “Frustrated” toward homework. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 1 . Similar to the student survey, parents also responded to a question regarding their child’s emotional experience surrounding homework. Based on parent reports, approximately 40% of parents perceive their child as “Frustrated” and about 37% acknowledge their child feeling “Stress/Anxiety.” Conversely, about 37% also report their child feels “Competence.” These results are reported in Table 1 .

Additionally, parents and teachers both responded to the question, “How does homework affect your student’s social and emotional health?” One notable finding from parent and teacher reports is that nearly half of both parents and teachers reported homework has “No Effect” on children’s social and emotional health. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 2 .

The second research question investigated in this study was: “What are parent and teacher perspectives on the primary purposes of homework?” For this question the examiners looked at three specific questions across parent and teacher surveys. Parents responded to the questions, “Does homework relate to your child’s learning?” and “How often is homework busy work?” While the majority of parents reported homework “Always” (45%) or “Often” (39%) relates to their child’s learning, parents also feel homework is “Often” (29%) busy work. The corresponding frequencies and percentages are summarized in Table 3 . Additionally, teachers were asked, “What are the primary reasons you assign homework?” The primary purposes of homework according to the teachers in this sample are “Skill Practice” (82%), “Develop Work Ethic” (61%), and “Teach Independence and Responsibility” (50%). The frequencies and percentages of teacher responses are displayed in Table 4 . Notably, on this survey item, teachers were instructed to choose one response (item), but the majority of teachers chose multiple items. This suggests teachers perceive themselves as assigning homework for a variety of reasons.

The third research question investigated was, “How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?” For this question the examiners analyzed parent and teacher responses to the question, “Does your school have a homework policy?” Frequencies and percentages are displayed in Table 5 . Notably, only two out of the six schools included in this study had homework policies. Results indicate that both parents and teachers are uncertain regarding whether or not their school had a homework policy.

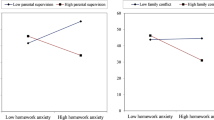

The fourth research question investigated was, “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?” Children were asked if they get less sleep because of homework and parents were asked if their child gets less sleep because of homework. Finally, teachers were asked about the impact of sleep on academic performance. Frequencies and percentages of student, parent, and teacher data is reported in Table 6 . Results indicate disagreement among parents and children on the impact of homework on sleep. While the majority of parents do not feel their child gets less sleep because of homework (77%), approximately 37% of children report sometimes getting less sleep because of homework. On the other hand, teachers acknowledge the importance of sleep in relation to academic performance, as nearly 93% of teachers report sleep always or often impacts academic performance.

To investigate the perceived impact of homework on the parent–child relationship, parents were asked “How does homework impact your child’s relationships?” Almost 30% of parents report homework “Brings us Together”; however, 24% report homework “Creates a Power Struggle” and nearly 18% report homework “Interferes with Family Time.” Additionally, parents and children were both asked to report if homework gets in the way of family time. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 7 . Data was further analyzed to explore potentially significant differences between parents and children on this perception as described below.

In order to prepare for analysis of significant differences between parent and child perceptions regarding homework and family time, a Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted. Results of the Levene’s test showed that equal variances could not be assumed, and results should be interpreted with caution. Despite this, a difference in mean responses on a Likert-type scale (where higher scores equal greater perceived interference with family time) indicate a disparity in parent ( M = 2.95, SD = 0.88) and child ( M = 2.77, SD = 0.99) perceptions, t (785) = 2.65, p = 0.008. Results suggest that children were more likely to feel that homework interferes with family time than their parents. However, follow up testing where equal variances can be assumed is warranted upon further data collection.

The purpose of this research was to explore perceptions of homework by parents, children, and teachers of grades 3–6, including how homework relates to child well-being, awareness of school homework policies and the perceived purpose of homework. A discussion of the results as it relates to each research question is explored.

Perceived Impact of Homework on Children’s Social-Emotional Well-Being Across Teachers, Parents, and Students