- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

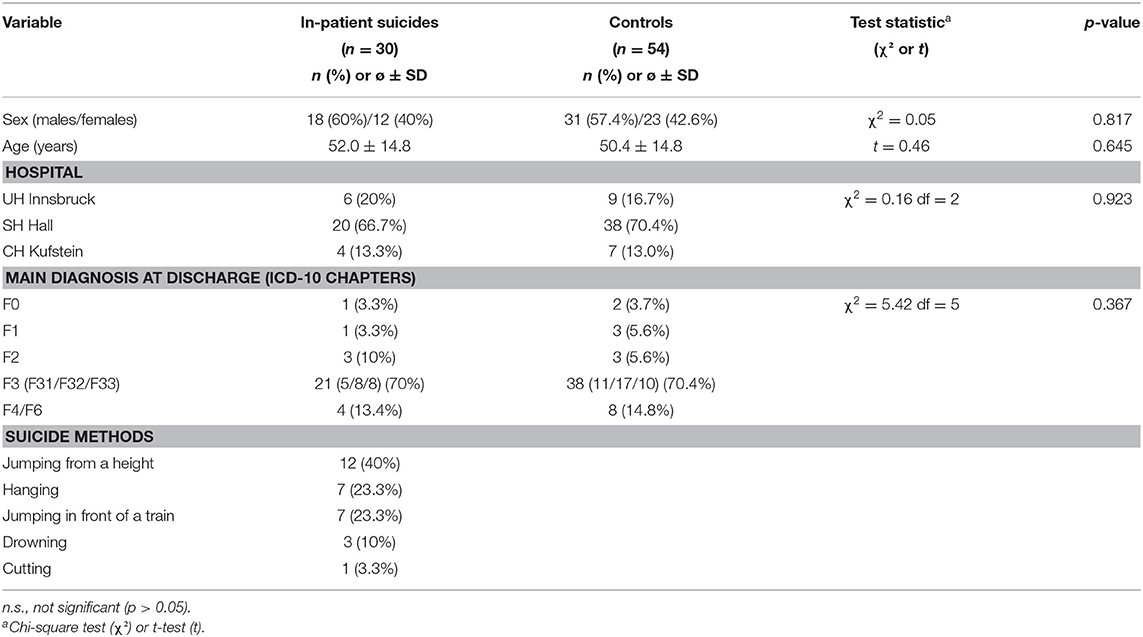

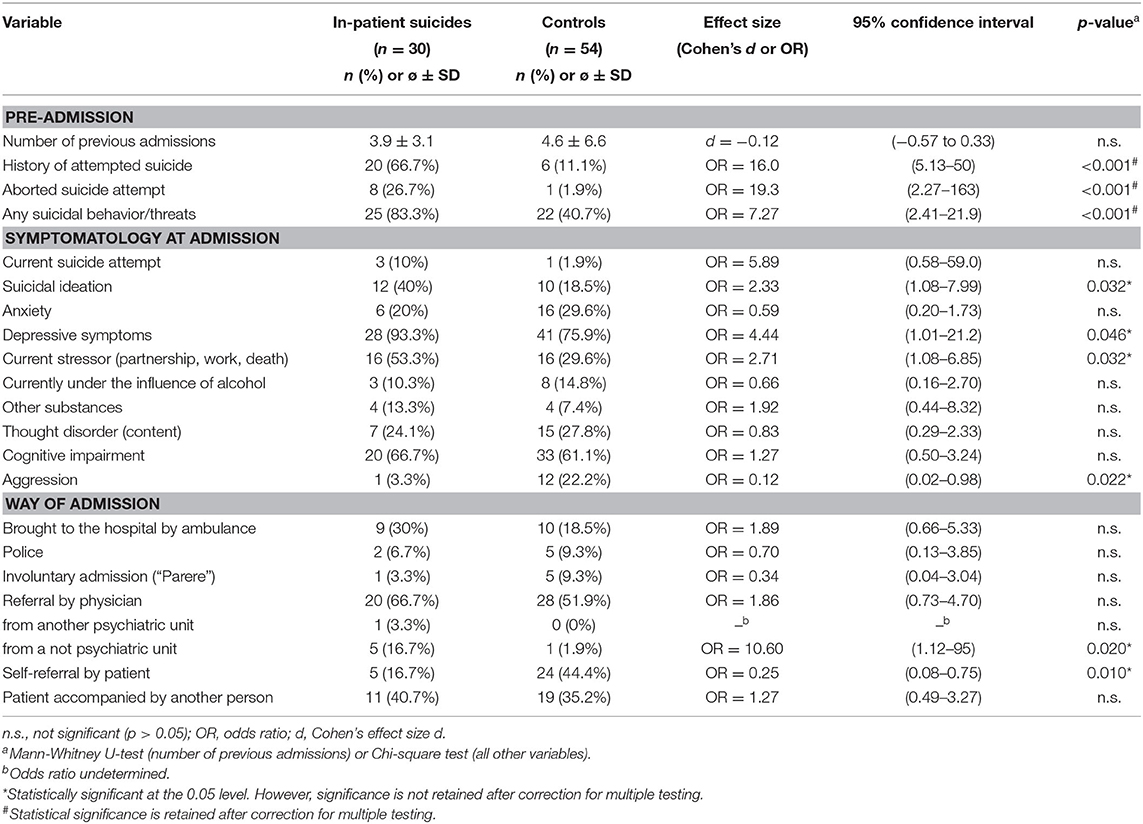

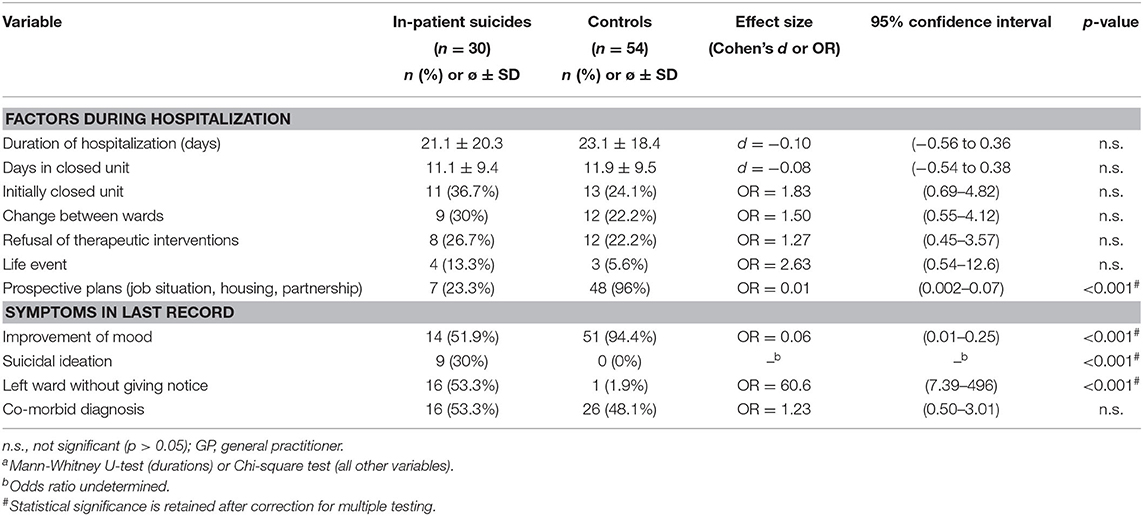

Flowchart describing the derivation of the study sample of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes (as defined in the eAppendix in Supplement 1 ), including the matched study sample of patients with MDD with and without suicidal behavior (SB). Suicidal behavior was defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes X60 to X84 (intentional self-harm) recorded in any diagnosis position and in both outpatient and inpatient health care settings. The Methods section provides more information. For MDD with SB, the index is the date of first SB within the MDD episode. The matched controls (patients with MDD without SB) are given the same index date as their matched case. The matching procedure is explained in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 .

Definition of an MDD episode is provided in the eAppendix in Supplement 1 . Suicidal behavior was defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes X60 to X84 (intentional self-harm) recorded in any diagnosis position and in both outpatient and inpatient health care settings. The Methods section provides more information. For MDD with SB, index is the date of first SB within the MDD episode. The matched controls (MDD without SB) are given the same index date as their matched case. The matching procedure is explained in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 .

Ongoing treatment with antidepressant therapy at 12 months before and 12 months after index.

eAppendix. Definition of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episode

eFigure 1. Matching Procedure for Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) With and Without Suicidal Behavior (SB)

eTable 1. Definitions of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, Treatments, and Comorbid Conditions

eTable 2. Definition of Variables Included in the Development of the Cox Proportional Hazards Model on Determinants for Suicidal Behavior (SB) Within 1 Year After Start of a Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episode

eFigure 2. Cumulative Proportion of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episodes With Records of Suicidal Behavior (SB) After Start of an MDD Episode, by Age Strata

eTable 3. Specification of Type of Suicidal Behavior (SB) Events in Descending Order Among the 2,240 Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and SB

eFigure 3. Cumulative Probability of All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) With and Without Suicidal Behavior (MDD-SB) Compared With MDD-Non-SB, Sensitivity Analysis

eTable 4. Characteristics at Start of the Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episodes (MDD-Baseline) Among Patients With Records of Suicidal Behavior (SB) Within the Current MDD Episode Compared With All MDD Episodes (With and Without Records of SB)

eFigure 4. Prevalence of Psychiatric Comorbid Conditions 12 Months Before and 12 Months After Index (Time of First Suicidal Behavior [SB] Within the Major Depressive Disorder [MDD] Episode)

eFigure 5. Mean Monthly Health Care Resource Utilization (HCRU) and Work Loss 12 Months Before and 12 Months After Index (Time of First Suicidal Behavior [SB] Within the Major Depressive Disorder [MDD] Episode)

eFigure 6. Nonogram for the Cox Proportional Hazards Model on Determinants for Suicidal Behavior Within 1 Year After Start of a Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episode, Based on Patients With MDD Episodes Between 2015 and 2017 Residing in Stockholm for at Least 3 Year Prior to Start of MDD

eFigure 7. Calibration of the Cox Proportional Hazards Model on Determinants for Suicidal Behavior (SB) Within 1 Year After Start of a Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Episode

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Lundberg J , Cars T , Lampa E, et al. Determinants and Outcomes of Suicidal Behavior Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(12):1218–1225. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2833

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Determinants and Outcomes of Suicidal Behavior Among Patients With Major Depressive Disorder

- 1 Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, and Stockholm Health Care Services, Stockholm, Sweden

- 2 Sence Research AB, Uppsala, Sweden

- 3 Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

- 4 Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

- 5 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

- 6 Janssen-Cilag AB, Solna, Sweden

Question What are the clinical and societal outcomes, including all-cause mortality, associated with suicidal behavior in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD)?

Findings In this cohort study of 158 169 unipolar MDD episodes, 1.4% involved records of suicidal behavior. The all-cause mortality among patients with suicidal behavior was 2.6 times higher than among matched patients with MDD without records of suicidal behavior.

Meaning These findings show an association between suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with MDD and warrant additional interventional studies in health care practice.

Importance Major depressive disorder (MDD) is an important risk factor of suicidal behavior, but the added burden of suicidal behavior and MDD on the patient and societal level, including all-cause mortality, is not well studied. Also, the contribution of various prognostic factors for suicidal behavior has not been quantified in larger samples.

Objective To describe the clinical and societal outcomes, including all-cause mortality, of suicidal behavior in patients with MDD and to explore associated risk factors and clinical management to inform future research and guidelines.

Design, Setting, and Participants This population-based cohort study used health care data from the Stockholm MDD Cohort. Patients aged 18 years or older with episodes of MDD diagnosed between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2017, in any health care setting were included. The dates of the data analysis were February 1 to November 1, 2022.

Exposures Patients with MDD with and without records of suicidal behavior.

Main Outcomes and Measures The main outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were comorbid conditions, medications, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and work loss. Using Region Stockholm registry variables, a risk score for factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode was calculated.

Results A total of 158 169 unipolar MDD episodes were identified in 145 577 patients; 2240 (1.4%) of these episodes, in 2219 patients, included records of suicidal behavior (mean [SD] patient age, 40.9 [18.6] years; 1415 episodes [63.2%] in women and 825 [36.8%] in men). A total of 11 109 MDD episodes in 9574 matched patients with MDD without records of suicidal behavior were included as controls (mean [SD] patient age, 40.8 [18.5] years; 7046 episodes [63.4%] in women and 4063 [36.6%] in men). The all-cause mortality rate was 2.5 per 100 person-years at risk for the MDD-SB group and 1.0 per 100 person-years at risk for the MDD-non-SB group, based on 466 deaths. Suicidal behavior was associated with higher all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 2.62 [95% CI, 2.15-3.20]), as well as with HCRU and work loss, compared with the matched controls. Patients with MDD and suicidal behavior were younger and more prone to have psychiatric comorbid conditions, such as personality disorders, substance use, and anxiety, at the start of their episode. The most important factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode were history of suicidal behavior and age, history of substance use and sleep disorders, and care setting in which MDD was diagnosed.

Conclusions and Relevance This cohort study’s findings suggest that high mortality, morbidity, HCRU, and work loss associated with MDD may be substantially accentuated in patients with MDD and suicidal behavior. Use of medication aimed at decreasing the risk of all-cause mortality during MDD episodes should be systematically evaluated to improve long-term outcomes.

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 5% of the adult population worldwide experienced depression in 2021. 1 Depression is associated with increased all-cause mortality. 2 A recent populationwide study showed that all-cause mortality was more than doubled in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) compared with population controls and that mortality is further increased in patients with treatment-resistant MDD. 3 , 4 Suicidal thoughts or behaviors are recognized as diagnostic criteria for MDD in the DSM-5 , and suicidal behavior, defined as self-inflicted harm with or without concurrent suicidal ideation, has been reported in up to 50% of patients with MDD; the longer the episodes, the higher the occurrence. 5 , 6 Furthermore, suicidal behavior and previous suicide attempts have been shown to increase the risk of death from suicide. Approximately 7% to 13% of patients with nonfatal suicide attempts have been reported to die from suicide at a later time, 7 , 8 and up to 7% of patients with MDD who are in contact with specialized psychiatric care have been reported to die from suicide. 6

However, most patients with MDD are not treated in specialized care, 9 , 10 and studies to date have been limited by nonrandom sampling due to nonuniversal access to health care and/or exclusion of primary care data. Thus, it is not established to what extent the aforementioned estimates are representative of patients with MDD as a whole or to what extent suicidal behavior is a risk factor for all-cause mortality. The focus on a specific cause of death (ie, suicide) may underestimate the overall risk of death in the population of patients with MDD and suicidal behavior. Thus, focusing on suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in a population-wide observational study may result in more clinically relevant and replicable data. In Sweden, all residents have universal access to health care, 11 with a nominal copayment for health care visits, hospitalizations, and drugs. The opportunities for individual record linkage, together with near-complete information on population health care coverage, including mortality, help to overcome some of the limitations in data that may exist in other countries and from clinical cohorts.

In this study, we investigated the all-cause mortality associated with MDD episodes with suicidal behavior (MDD-SB) compared with MDD episodes without records of suicidal behavior (MDD-non-SB). We also aimed to describe patient clinical characteristics, such as comorbid conditions, treatment patterns, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and work loss. Furthermore, in a separate analysis, we identified risk factors of suicidal behavior in patients with MDD based on information available at the start of an MDD episode.

In this population-based cohort study, we used data from the Stockholm MDD Cohort (SMC), 3 , 4 which comprises all patients diagnosed with MDD according to International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision ( ICD-10 ) codes F32 to F33 in any health care setting in the region of Stockholm (approximate population, 2.4 million) between 2010 and 2018. 12 The data in SMC are based on the Regional Healthcare Data Warehouse of Region Stockholm, including information on all individual contacts with health care in Region Stockholm. The information in the data warehouse includes date of death but not cause of death. This project is a part of a framework to facilitate research collaboration between research-based companies and Region Stockholm and registered at the European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorisation Studies No. 256646). The study was approved by the regional ethics committee, Stockholm, Sweden (No. 2018/546-31), with a waiver for informed consent because all analyses were performed using pseudonymized data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

We identified all recorded MDD episodes between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2017, when patients were aged 18 years or older at the start of the episode (MDD baseline) (eAppendix in Supplement 1 ). Each patient could contribute more than 1 episode. To allow for analyses of MDD baseline conditions, patients residing in Stockholm for 12 months or less before the start of the MDD episode were excluded. We also excluded patients with a history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, manic episode, or dementia. Diagnostic criteria for MDD include suicidal thoughts or attempts (suicidal behavior); therefore, suicidal behavior was defined as ICD-10 codes for intentional self-harm (X60-X84). Diagnoses of harm of undetermined intent ( ICD-10 codes Y10-Y34) were not included in this study. Records in outpatient or inpatient health care settings were collected, and the date of the first recorded diagnosis of suicidal behavior within an MDD episode was set as the index. At the start of an MDD episode (MDD baseline), patients with MDD and suicidal behavior (MDD-SB group) were compared with all patients with MDD. At index, patients in the MDD-SB group were compared with patient with MDD but without records of suicidal behavior (MDD-non-SB group) by matching each patient in the MDD-SB group (ie, cases) on age (within 2 years), sex, year of MDD diagnosis, and sociodemographic status with up to 5 patients in the MDD-non-SB group (ie, controls). To be eligible for matching, controls were required to have an MDD episode duration at least as long as their matched case’s time from the start of MDD until record of first suicidal behavior. Controls were given the same index date as their matched case (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 ). Definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in eTable 1 in Supplement 1 .

The data analysis for this study was performed between February 1 and November 1, 2022. All data management and analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.0 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Patient characteristics were described at MDD baseline and index (date of suicidal behavior). In the time-to-event analyses, patients were censored at first instance of emigration from Stockholm, death, a record of an exclusion criterion, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. The time to first suicidal behavior was calculated as the time from MDD baseline until index, and in this analysis, end dates of MDD episodes also qualified as censoring events. To evaluate the association of suicidal behavior with all-cause mortality, we used the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards regression models. Robust SEs were used to account for nonindependence (ie, that 1 patient could have had >1 case of suicidal behavior per MDD episode). Episodes of MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB were followed up from index until the outcome. In a sensitivity analysis, end dates of MDD episodes were also included as censoring events. Departures from the proportional hazards assumption were evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals.

We analyzed psychiatric comorbid conditions, ongoing antidepressant therapy, HCRU, and work loss from 12 months before to 12 months after the index date. Psychiatric comorbid conditions were expressed as cumulative proportions per month; ie, patients were included the first month they were diagnosed with a psychiatric comorbid condition, and this information was carried forward to all later time points. Ongoing treatment with antidepressant therapy (antidepressants, add-on medication, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT], repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy) (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ) was calculated as the proportion of patients treated per month. To be defined as receiving ongoing treatment with antidepressant and add-on medication, each patient had to have at least 1 pharmacy dispensation of medication that month or be covered with a medical supply from a previous dispensation. For electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or psychotherapy, patients were required to have at least 1 record of a clinical procedure code for that procedure that month. Health care resource utilization was defined as the mean number of outpatient physician visits and inpatient bed days per month, and work loss was defined as the mean number of days not worked per month. Analyses of work loss were performed for patients aged between 20 years and 64 years. Sick leave episodes lasting 14 days or less were not included, as they are not recorded in patient records.

Risk factors for suicidal behavior among patients with MDD were assessed using a study sample restricted to MDD episodes between 2015 and 2017. Only patients residing in Stockholm for 3 years or more prior to the start of the MDD episode were included to ensure a sufficient period of baseline data. Episodes where the start date of the MDD and date of suicidal behavior coincided were excluded. In the model, the outcome of interest was a record of suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode. Potential risk factors (eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ) were selected based on previous reports and data availability, 13 - 16 and a Cox proportional hazards regression model was fitted following the steps by Harrell 17 (details provided in eFigure 6 in Supplement 1 ). The final prediction model was presented as a nomogram. The importance of each risk factor was measured by partial Wald χ 2 minus the predictor df . We adhered to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis ( TRIPOD ) statement 18 in reporting of the results of the prediction model.

A total of 158 169 unipolar MDD episodes were identified between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2017 ( Figure 1 ). Among these episodes, 2240 (1.4%) in 2219 patients had at least 1 record of suicidal behavior (MDD-SB group; mean [SD] patient age, 40.9 [18.6] years; 1415 episodes [63.2%] in women and 825 [36.8%] in men), and 552 (24.6%) of these contained 2 or more records of suicidal behavior. In MDD episodes lasting 5 years or more, 430 of 14 170 (3.0%) had at least 1 suicidal behavior (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 ). The most common form of suicidal behavior was intentional self-poisoning (eTable 3 in Supplement 1 ). The median time from MDD baseline (ie, from start of episode until first suicidal behavior) was 165 days (IQR, 12-510 days). The matched MDD-non-SB control group included 11 109 MDD episodes in 9574 patients (mean [SD] patient age, 40.8 [18.5] years; 7046 episodes [63.4%] in women and 4063 [36.6%] in men) ( Figure 1 ). Patient characteristics at the time of the first suicidal behavior within an MDD episode (index) for the matched study sample are presented in the Table .

The all-cause mortality rate was 2.5 per 100 person-years at risk for the MDD-SB group and 1.0 per 100 person-years at risk for the MDD-non-SB group, based on 466 deaths. This rate corresponds to a hazard ratio of 2.62 (95% CI, 2.15-3.20) ( Figure 2 ). In a sensitivity analysis, MDD episodes were censored at the end of the MDD episode (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1 ).

Already at the start of the MDD episode, patients in the MDD-SB group appeared different compared with all patients with MDD. For example, they were younger, more often diagnosed while in specialized care, and had higher work loss (eTable 4 in Supplement 1 ). Patients in the MDD-SB group also had a gradual increase in the prevalence of comorbid conditions from approximately 12 months before index (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1 ). This increase was most pronounced for anxiety, stress, substance use, and personality disorders. These differences persisted at index between the MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB groups ( Table ). eFigure 5 in Supplement 1 displays the temporal distribution of monthly HCRU and work loss, with a clear peak at index for the MDD-SB group.

Up until index, 1880 patients (83.9%) in the MDD-SB group and 9012 patients (81.1%) in the MDD-non-SB group were treated with antidepressants ( Table ). The proportion of patients treated with add-on medication (including lithium in 21 patients [0.9%] and 25 patients [0.2%] in the MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB groups, respectively) and ECT was higher among those in the MDD-SB group both at index and 12 months after compared with the MDD-non-SB group. A total of 82 patients (3.8%) in the MDD-SB group received ECT during the index month, and the provision of psychotherapy ranged between 248 (11.5%) and 275 (14.2%) patients starting at the index month and through the 12 months after the index month ( Figure 3 ).

A risk score for factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode (outcome) was calculated using available variables. The 2 most important risk factors for suicidal behavior were a history of suicidal behavior together with age, which had a U-shaped association with the outcome, with individuals younger than 20 years or 70 years or older having the highest risks. The final risk score also included the following factors (in descending order), the presence of which increased the risk for the outcome: history of substance use, history of sleep disorders, health care level in which MDD was diagnosed, history of antidepressant use, and history of anxiety disorders. eFigure 6 in Supplement 1 displays the final prediction model, presented as a nomogram; all variables evaluated for entry are defined in eTable 2 in Supplement 1 . The risk score yielded a C index of 0.78, and the internal bootstrap validation indicated only minimal overfitting. The risk score was well calibrated (eFigure 7 in Supplement 1 ).

In this cohort study, we analyzed more than 158 000 MDD episodes during 6 years, of which 2240 (1.4%) also included suicidal behavior, with an average time from MDD diagnosis to first record of suicidal behavior of less than 6 months. We found that all-cause mortality was more than doubled in adults with MDD who had a diagnosis of suicidal behavior compared with those with MDD without suicidal behavior, which in and of itself is associated with a doubled risk compared with control patients without MDD. 2 , 3 We found an immediate increase in mortality after the first suicidal behavior event, which appeared to be elevated throughout the whole observation period. This suggests that suicidal behavior may be a marker for MDD episodes with an increased risk of mortality; although the SMC data were not linked to information regarding cause of death, and any inference regarding causality remains speculative. However, the incidence of somatic disorders was not increased in the MDD-SB group, indicating that unnatural causes, such as accidents and suicides, may have been the main contributors to the increased mortality.

The proportion of patients with suicidal behavior in our study appears to be lower than in other registry-based studies of patients with MDD 19 and compared with self-reports from a general population. 5 A possible explanation could be the virtually full coverage of the patient population with MDD with data from all health care settings in our study, thus not limiting the sample to populations that could be considered to have a higher risk of suicidal behavior, such as patients treated in hospitals or other specialized settings. To reduce the risk of misclassifications, we also chose a stricter definition of suicidal behavior by only including self-harm with intent diagnosed during an ongoing MDD episode. Although previous studies have shown that suicidal behavior is underdiagnosed, 5 our findings suggest that suicidal behavior in all patients with MDD may not be as common as previously described, although any estimate of suicidal behavior and/or suicide attempt could be subject to uncertainty and methodological considerations. However, in our data, suicidal behavior might be seen as a marker for a subgroup of MDD episodes with more psychiatric comorbidity, higher work loss, and substantially higher all-cause mortality. Thus, developing an evidence-based clinical guideline for both acute and long-term interventions for patients with MDD and suicidal behavior may be warranted.

In our study, the majority of patients were treated with antidepressants at the time of their suicidal behavior, indicating that the treatment may not have been sufficiently effective in ameliorating depressive symptoms and associated suicidal behavior. Although the proportion of patients in the MDD-SB group treated with add-on medications, ECT, and/or psychotherapy increased after the first record of suicidal behavior, the proportions were still low. This finding suggests that treatments for a majority of patients with MDD and suicidal behavior could be improved both before and especially after an suicidal behavior event. Specifically, long-term lithium treatment could be indicated given its suggested association with decreased all-cause mortality in affective disorders. 20 Still, our findings showed that less than 1% of patients with MDD and suicidal behavior had initiated treatment with lithium at the time of their first recorded suicidal behavior.

The baseline prevalence of nonpsychiatric comorbid conditions was lower in patients with MDD and suicidal behavior compared with all patients with MDD. This finding could be explained by the lower age at baseline, as the differences disappeared after matching. At baseline, patients in the MDD-SB group also had greater proportions of anxiety disorders and substance use than the MDD-non-SB group, which have previously been shown to be factors linked to suicide, suicide attempts, and deliberate self-harm. 13 , 15 , 21 - 25 Sleep disorders and substance use disorders have previously been reported to be associated with increased all-cause mortality, 26 , 27 whereas anxiety has not. 28 These specific comorbidities were all found to be associated with suicidal behavior in our data. Personality disorders have been linked to suicidal behavior, 13 and they constituted the highest relative difference in proportions between the MDD-SB group and MDD-non-SB group in our study. In addition, the number of patients with personality disorders almost doubled during the follow-up period, suggesting that they were previously underdiagnosed. In absolute numbers, however, the majority of suicidal behavior events were not linked to personality disorders.

The frequency of health care contacts and high rates of psychiatric comorbidity among patients with MDD who later develop suicidal behavior presents important opportunities for health care to identify and treat these patients at an early stage. A comprehensive approach that also includes diagnosing and addressing these comorbidities, in addition to treating depressive symptoms, would be beneficial. Should evidence-based guidelines be developed on how to best optimize treatments to avoid suicidal behavior, they should include early detection of potential patients with MDD and suicidal behavior. With future evidence-based guidelines in mind, we calculated a risk score based on variables present in our data. The risk score could be explored as a tool to help identify the risk of suicidal behavior among patients with MDD in clinical practice. In the risk score, the most important factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode were history of suicidal behavior and age, followed by history of substance use and sleep disorders. However, it is important to emphasize that the predictive ability of this tool needs to be evaluated in other patient populations and to acknowledge that some important variables, such as family history of psychiatric conditions, were not included. 23 Thus, this tool should be used as a complement and should not supersede a thorough clinical evaluation. It is important to acknowledge that not all patients with suicidal behavior present for treatment, 29 even in a universal health care system, which limits the assessment of risk factors and possibilities for prevention.

This study had several limitations. We defined suicidal behavior as any diagnosis of intentional self-harm ( ICD-10 codes X60-X84) and did not include diagnoses of harm of undetermined intent ( ICD-10 codes Y10-Y34). Even so, this broad definition probably gives a comprehensive picture of suicidal behavior among patients with MDD. An suicidal behavior episode was defined by records of consecutive events, and any additional records of suicidal behavior at later time points were attributed to a new episode. This strict definition might have slightly overestimated the number of suicidal behavior episodes, which should be contrasted to previous reports that suicidal behavior is underdiagnosed. 5 The study population consisted of unipolar MDD episodes and excluded patients with records of bipolar disorder, dementia, or psychosis before or at baseline, and patients who developed any of these conditions later were censored in time-to-event analyses, limiting our ability to draw conclusions on MDD-SB in these patient groups. However, suicidal behavior may also be associated with an increased risk of mortality in other psychiatric disorders. Other comorbid conditions, such as anxiety, substance use, and personality disorders, were included, which is important since they are common among patients with MDD in general, as well as among patients with MDD and suicidal behavior in particular.

In this cohort study, we found that 1.4% of MDD episodes in Stockholm, Sweden, involved records of suicidal behavior, which is lower than previously reported. 6 - 8 Among these patients, the all-cause mortality was more than doubled compared with MDD episodes without records of suicidal behavior. Our results also indicate that patients at risk for suicidal behavior can be identified at an early stage to allow for enhanced monitoring and optimized treatment with the goal of preventing suicidal behavior and reducing mortality.

Accepted for Publication: June 9, 2023.

Published Online: August 16, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2833

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Lundberg J et al. JAMA Psychiatry .

Corresponding Author: Johan Lundberg, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, and Stockholm Health Care Services, Region Stockholm, Norra Stockholms Psykiatri, Vårdvägen 3, SE-112 81 Stockholm, Sweden ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Lundberg and Cars had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Lundberg, Cars, Leval, Gannedahl, Själin, Björkholm, Hellner.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Lundberg, Cars, Lampa, Ekholm Selling, Leval, Själin, Björkholm, Hellner.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lundberg, Cars, Lampa, Ekholm Selling, Gannedahl, Björkholm, Hellner.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lundberg, Cars, Lampa, Ekholm Selling, Leval, Själin, Björkholm, Hellner.

Statistical analysis: Lundberg, Cars, Lampa, Ekholm Selling.

Obtained funding: Leval.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lundberg, Ekholm Selling, Leval, Björkholm, Hellner.

Supervision: Själin, Hellner.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Car reported being a co-owner of Sence Research, which is an independent company in epidemiology and biostatistics; Janssen-Cilag AB has funded Sence Research for statistical analyses within this research project. Dr Lampa reported receiving consulting fees from Biogen outside of the submitted work. Dr Leval reported holding shares from Johnson and Johnson outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by Region Stockholm and Janssen-Cilag AB. This research project is part of a framework aimed to facilitate research collaborations between the public health care authorities in Stockholm County, Sweden, and research-based companies. All pharmaceutical companies in Sweden were invited to participate in this depression research program via the pharmaceutical industry trade association. Region Stockholm was the initiator of this research project and governed all research data. Region Stockholm further supported this project with scientific and clinical expertise.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The sponsor (research authority) Region Stockholm was responsible for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Janssen-Cilag participated, provided scientific expertise, and supported the analytic work for this project via an external company in biostatistics (Sence Research). No financial transfers were made between Janssen-Cilag AB and Region Stockholm.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

Additional Contributions: The authors thank Karolinska University Hospital, Danderyds sjukhus AB, Södersjukhudet AB, TioHundra AB, Södertälje sjukhus, Stockholms läns sjukvårdsområde, and the public Health Care Services Administration for providing data for this study.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 13, Issue 10

- Severe psychiatric disturbance and attempted suicide in a patient with COVID-19 and no psychiatric history

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0270-9369 George Gillett 1 and

- Iain Jordan 2

- 1 Oxford University Clinical Academic Graduate School , University of Oxford , Oxford , UK

- 2 Oxford Psychological Medicine Centre , Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust , Oxford , UK

- Correspondence to Dr George Gillett; george.gillett{at}live.co.uk

A previously fit and well 37-year-old male healthcare worker presented with confusion, psychotic symptoms and a suicide attempt in the context of a new COVID-19 diagnosis. Following surgical interventions and an extended admission to the intensive care unit, he made a good recovery in terms of both his physical and mental health. A number of factors likely contributed to his presentation, including SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe insomnia, worry, healthcare worker-related stress, and the unique social and psychological stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. This case highlights the need to further characterise the specific psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 in community settings, and should remind general medical clinicians to be mindful of comorbid psychiatric symptoms when assessing patients with newly diagnosed COVID-19.

- psychotic disorders (incl schizophrenia)

- public health

- infectious diseases

- suicide (psychiatry)

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ’s website terms and conditions for the duration of the covid-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-239191

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, remains an emerging disease with poorly defined psychological sequelae. Previous reports have identified that confusion, low mood, anxiety and insomnia are associated with severe coronavirus infection, 1 although the precise risk factors and mechanisms by which these symptoms develop are unclear.

It has been speculated that healthcare workers may be especially vulnerable to the neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 due to work-related stress, bereavement and their increased risk of infection. 2 3 Emerging evidence suggests healthcare workers may be at greater risk of depression, anxiety and insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic, 3 although the prevalence of severe psychiatric symptoms among healthcare workers has not been thoroughly investigated.

We present the case of a 37-year-old healthcare worker presenting with severe psychiatric disturbance and attempted suicide following SARS-CoV-2 infection. We explore a number of potential contributing factors including encephalopathy, severe worry, ethnicity and work-related stress. The case highlights the importance of vigilance towards psychiatric symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in both inpatient and community settings.

Case presentation

The patient is a 37-year-old married man with two young children. Prior to this admission, he had no notable medical or psychiatric history, took no regular medications and had no allergies. He is a mental health nurse and works in the UK, where he has raised a family and lived for a number of years. He is of Black ethnicity. Regarding family history, his sister, aunt and grandfather were described as having experienced psychotic episodes, although the circumstances surrounding these and any subsequent diagnoses are not known.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the patient experienced a 5-day history of fever, cough, breathlessness and myalgia. He experienced severe insomnia during this period, and reported feeling worried that he may infect his family. He had recently lost a number of patients to COVID-19 in the facility he worked at, which had been severely affected by the pandemic. Later, the patient would recall that he became preoccupied with biblical passages during this period, believing they were connected to the events happening in his life.

After self-isolating at home in line with current guidance, an ambulance was eventually called in relation to his worsening breathlessness. He was assessed by paramedics at home. It was agreed that he did not require hospital review, and he was advised to self-isolate at home.

That night, the patient’s family noted that he became increasingly confused and began acting bizarrely. He reported that he had both seen and heard the devil, and was also observed responding to auditory hallucinations. During the night he became increasingly anxious and was specifically preoccupied about dying and concerned he would infect his family. At approximately 04:00, he began to clean out the garden shed to sleep in, in order to be safely distanced from his children. In a phone-call with a family member, he was reported as being ‘confused’ and ‘paranoid’. He was also incontinent of urine.

Later that morning, the patient presented to the emergency department of a local hospital with ongoing concerns about his breathlessness. Clinical assessment, bloodwork and imaging (chest radiograph and CT of the head) did not indicate a need for admission. A swab test for SARS-CoV-2 was taken, and the patient was advised to return home and continue self-isolating. His family raised concerns about his mental state, but recall that no formal psychiatric assessment was performed.

The patient was driven home by a family member. On return, he went to the bathroom, stating he would wash to avoid infecting his family. Within approximately 20 minutes, his wife heard loud noises. On investigating, she found that the patient had lacerated his neck and jumped from an upstairs window. Emergency service attended the scene; the patient was heard telling clinicians “this is not me”. He was sedated, intubated, fluid resuscitated and transferred to a local trauma centre. On arrival, he was noted to have a deep anterior neck laceration (12 cm by 4 cm) and an open wound of his right knee.

Investigations

CT imaging of the patient’s neck and chest revealed pneumomediastinum and surgical emphysema of the neck secondary to tracheal injury, and ground glass opacification and consolidation in keeping with moderate COVID-19. A CT of the head revealed no intracranial pathology. Fractures of the left radius, left ulna, left and right ankles were noted on imaging, alongside a vertebral compression fracture of L1. Bloodwork revealed an elevated white cell count (24.18×10 9 /L) with lymphopenia (0.51×10 9 /L), normal C reactive protein (1.5 mg/L) and electrolytes within normal range. Toxicology tests (ethanol, paracetamol, salicylate) were all negative. A SARS-CoV-2 PCR test was positive.

During his subsequent intensive care admission, a repeat CT of the head, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies (lactate, glucose, protein, microscopy, cytology, flow cytology and NMDA receptor antibodies) and serology tests (CASPPR2, LGI1, voltage-gated potassium channel and NMDA receptor antibodies, HIV and syphilis) were performed; all were negative.

Differential diagnosis

This patient’s case likely represents either a manifestation of either delirium, a single acute psychotic episode or a manic episode in keeping with bipolar affective disorder. Factors supporting a diagnosis of delirium include the lack of any personal psychiatric history, the rapid onset of symptoms, quick recovery, amnesia and predominance of confusion throughout the event. Meanwhile, the patient’s family history of psychotic episodes may support the diagnosis of a single acute psychotic episode. A manifestation of bipolar-spectrum illness is also possible, given the patient’s apparent decreased need for sleep, increased energy and psychotic symptoms. Regardless, the underlying causes are similar; SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe insomnia, stress, preoccupation and worry are likely to have contributed to the patient’s mental deterioration.

The patient was taken to operating theatres for an anterior tracheal repair and tracheostomy. The injury was noted to involve very deep lacerations of his larynx and neck resulting in severed cricothyroid joints, an open hole in the airway and bilateral external jugular venous haemorrhage. After surgery, he was kept sedated and admitted to the intensive care unit for ongoing support. Orthopaedic open reduction internal fixation and manipulation under anaesthesia were performed for his left radius and ankle fractures 2 days later.

The patient’s intensive care admission was complicated by haemodynamic instability, line sepsis, renal failure, refeeding syndrome and agitation. When sedative agents were reduced, he was noted to be agitated on a number of occasions, resulting in him pulling out his tracheostomy tube. Difficulty weaning sedative agents (propofol and fentanyl) contributed to a prolonged 32-day admission.

Regular olanzapine was commenced alongside PRN diazepam. The latter of these was introduced to facilitate weaning from intravenous sedatives rather than for primary treatment of psychiatric symptoms. Intravenous sedation was gradually weaned and the patient eventually began to wake safely. Communication was difficult due to the patient’s tracheostomy and oxygen requirements, however he smiled when family members visited and video-called, and he engaged with staff appropriately. At a bedside assessment, using a whiteboard to communicate, he calmly introduced himself to the consultant psychiatrist. He was orientated to being in hospital and the current year, and retained information about the exact date. The patient had no recollection of events leading to admission and was surprised to discover that he had jumped from a window. Although appearing tearful at times, he showed no signs of overt distress. He denied any current suicidal thoughts and expressed eagerness to recover and see his family.

The patient was weaned off oxygen support and stepped down to ward-level care. He remained settled, and worked cooperatively with physiotherapists both on and off the ward. His speech improved, and the psychiatry team assessed him on a number of occasions during this period. The patient recalled experiencing frightening disorientation, paranoia and hallucinations on the intensive care unit. It was explained that these are common features of delirium.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient continued to have limited recollection of the events leading up to admission, other than recalling severe worry about SARS-CoV-2 infection, insomnia and some religious preoccupation. He discussed the possibility of psychiatric illness openly and was curious towards a diagnosis to explain the events leading to admission. On the ward, he showed no signs of psychosis or suicidality, although did feel inexplicably tearful on occasion, struggled to concentrate while reading and had fragmented memories of the past week. These symptoms improved within days. At further assessments, he remained fully orientated, remembered previous conversations at each assessment and showed no signs of psychiatric illness. The patient’s tracheostomy was decannulated, and he was discharged on olanzapine, with appropriate medical and community mental health follow-up.

Since his discharge, the patient has remained well. On returning home, he initially experienced flashbacks of the events of deliberate self-harm, although these intrusions have now ceased. He is sleeping well, spending time with his family and showing no signs of agitation. He has been counselled on the importance of sleep and vigilance for signs of recurrence, and continues to take olanzapine while awaiting further community mental health review.

COVID-19 remains an emerging disease, with unknown psychological sequelae. A meta-analysis of severe coronavirus infection identified both delirium and insomnia to be common among such patients. 1 Delirium was especially prevalent despite the relatively young age of the sample. 1 Likewise, a separate analysis of 40 469 patients’ electronic medical records identified insomnia and delirium to be prevalent manifestations of COVID-19. 4

Neuroinflammation, neurotropic SARS-CoV-2 infection, hypoxia, cerebrovascular events and the effect of steroid treatment have all been speculated to act as biological mediators of psychiatric disturbance in COVID-19, although the quality of evidence is poor. 1 5 Previous reports have observed new-onset psychotic symptoms in patients with coronavirus infection, 6–9 although the difficulty of differentiating delirium and psychosis has been noted. 10 The vast majority of evidence focuses on psychiatric presentations in hospitalised patients and may be less generalisable to those with mild or moderate physical symptoms in community settings. 1 In this case, both neuroimaging and CSF studies were normal, although these findings cannot exclude the role of neuroinflammation, neurotropic infection or hypoxia as potential biological mediators of the patient’s psychiatric disturbance.

Evidence supporting an aetiological role for neuroinflammation triggered by COVID-19 includes the finding that patients with psychiatric disorders have elevated serum levels of IgG to human coronaviruses compared with controls, and that this association may be partially specific to psychotic, compared with mood, disorders. 11 Coronavirus strains tested include 229E, HKU1, NL63 and OC43, although to our knowledge, similar studies focused on immunoglobulins against SARS-CoV-2 are yet to be performed.

Neurotropic SARS-CoV-2 infection is also a plausible explanation of the patient’s psychiatric presentation in the above case. The functional receptor by which SARS-CoV-2 enters host cells is the ACE2 receptor, which is expressed in brain endothelium, allowing a plausible mechanism for neurotropic SARS-CoV-2 infection. 12 Peripheral nerve invasion has also been hypothesised as a potential route for neurotropic infection, while neuronal degeneration has been identified in the brains of patients with SARS-CoV infection, suggesting that neurotropism may plausibly mediate the psychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. 13 14

The coagulopathy associated with COVID-19 may also represent a potential aetiological factor in this case. Of particular interest are studies which have identified abnormalities consistent with hypercoagulability in patients with psychosis, and proteomic evidence which suggests complement activation and hypercoagulation may precede psychosis in the general population. 15 Although such evidence is limited, if associations between coagulation abnormalities and psychosis are rigorously established, hypercoagulability may represent a plausible mechanism by which COVID-19 mediates its neuropsychiatric sequelae.

A range of unique psychological and social factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may also have contributed to the patient’s presentation. Policy measures may detrimentally affect general population’s mental health regardless of infection through social distancing, decreased physical exercise, unemployment, domestic violence, loss of routine and health anxiety. 16 17 Social stress associated with the pandemic has been implicated in a number of reports of psychotic symptoms in patients without SARS-CoV-2 infection 18 19 and preliminary evidence suggests increased rates of new schizophrenia diagnoses in a region affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. 16

Similarly, social factors may specifically exacerbate the psychiatric consequences of COVID-19 compared with other physical illnesses. Quarantine measures may lead to psychiatric distress and insomnia, 20 while SARS-CoV-2 infection may be associated with greater anxiety symptoms compared with other non-COVID-19 pneumonias. 1 Specific anxieties commonly relate to transmission of the virus to family members and to death. 1

The patient’s occupation as a healthcare worker may have contributed to his presentation. Healthcare workers are thought to be at increased risk of mental ill-health during pandemic situations due to overwork, exhaustion, frustration, bereavement, risk of infection and discrimination. 2 3 Data from the COVID-19 pandemic suggests frontline healthcare workers, especially nursing staff, appear to be especially at risk of experiencing psychological symptoms and insomnia. 3 Specific to this case, the patient had lost a number of patients to COVID-19 at the facility he worked at, which may have contributed to his psychological distress and influenced the nature of his preoccupation and anxiety relating to the transmission of the virus to family members.

Another potentially relevant factor in the patient’s case is his ethnicity. The emerging literature suggests that COVID-19 disproportionately affects BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities in terms of prevalence and mortality, 21 and more recently concerns have been expressed about a potentially disproportionate impact on the mental health of such communities. 22 Posited reasons for a racial disparity in mental ill-health include fear of contracting the virus, bereavement of social contacts and the disproportionate impact of social distancing measures on BAME communities. 23 Although the patient did not report any direct discrimination by healthcare workers during the admission, his ethnicity may have contributed to his presentation through the indirect risk factors previously described in the literature. 22 23

Regardless of whether any potential association between COVID-19 and mental illness is mediated through biological, psychological or social factors, this case should make general medical clinicians alert to psychiatric presentations and their associated risk when assessing patients with COVID-19. Of particular concern is a similar case of a man who jumped from a third-floor window during self-isolation with SARS-CoV-2 24 and a number of reports of nurses attempting suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic. 25 Likewise, psychiatrists should be mindful of the contribution of biological, psychological and social factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic when assessing patients with primarily psychiatric presentations. Such associations are likely to be multifactorial, may require careful assessment and will likely go beyond the projected rise in post-traumatic symptoms associated with critical illness.

As well as aetiology, the treatment detailed in this case is also relevant to the association between SARS-CoV-2 and its psychiatric sequelae. This case adds to two previous reports of manic or psychotic episodes which have responded well to conventional antipsychotic treatments. 14 26 This preliminary evidence may reassure clinicians that COVID-19-associated psychiatric presentations are treatable with established pharmacotherapies. However, as aetiological factors are elucidated, it is possible that more specific therapies are identified for presentations involving psychiatric symptoms. For instance, the hypercoagulable state associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection may represent a potential area of future therapeutic interest.

In conclusion, we report on the case of a 37-year-old man with no psychiatric history, who presented with confusion, psychotic symptoms and a suicide attempt in the context of a new COVID-19 diagnosis. We suggest this case may represent delirium, psychosis or a manic episode, and discuss a number of potential precipitating factors including SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe insomnia, worry and healthcare worker-related stress. The array of psychiatric manifestations associated with COVID-19 remains unclear and the majority of literature focuses on secondary psychiatric symptoms among patients hospitalised for severe infection. This case may therefore highlight the need to further characterise the specific psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 in community settings, which may be in part achieved by performing case–control serological studies as in previous epidemics. 1

Learning points

General medical clinicians should be alert to psychiatric symptoms in patients recently diagnosed with COVID-19 and their associated risks.

Psychiatrists should be mindful of the wide contribution of biological, psychological and social factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic which may precipitate or perpetuate primarily psychiatric presentations.

The majority of research literature investigating comorbid psychiatric symptoms in COVID-19 has focused on patients hospitalised for severe infection. There may be an unmet need to characterise the specific psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 in community settings.

- Rogers JP ,

- Chesney E ,

- Oliver D , et al

- McMahon L , et al

- Spoorthy MS ,

- Pratapa SK ,

- Nalleballe K ,

- Reddy Onteddu S ,

- Sharma R , et al

- Troyer EA ,

- Varatharaj A ,

- Ellul MA , et al

- Leung HCM , et al

- Losada CP , et al

- Ferrando SJ ,

- Klepacz L ,

- Lynch S , et al

- Rentero D ,

- Severance EG ,

- Dickerson FB ,

- Viscidi RP , et al

- Hamming I ,

- Bulthuis MLC , et al

- Li S , et al

- Mawhinney JA ,

- Wilcock C ,

- Haboubi H , et al

- Lo Monaco S , et al

- Zhao M , et al

- Valdés-Florido MJ ,

- López-Díaz Álvaro ,

- Palermo-Zeballos FJ , et al

- Huarcaya-Victoria J ,

- Herrera D ,

- Brooks SK ,

- Webster RK ,

- Smith LE , et al

- Webb Hooper M ,

- Nápoles AM ,

- Pérez-Stable EJ

- Kapilashrami A ,

- Bailey S , et al

- Epstein D ,

- Andrawis W ,

- Lipsky AM , et al

- Komisar JR ,

- Mourad A , et al

Twitter @george_gillett

Contributors Both authors made a substantial contribution to the conception, design, drafting and revising of the article. GG wrote the first draft of the manuscript and IJ supervised the project.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Obtained.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- Spring 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 2 Autism Across the Lifespan CURRENT ISSUE pp.147-262

- Winter 2024 | VOL. 22, NO. 1 Reproductive Psychiatry: Postpartum Depression is Only the Tip of the Iceberg pp.1-142

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Ethics Commentary: Suicide Risk: Ethical Considerations in the Assessment and Management of Suicide Risk

- Rebecca A. Bernert , Ph.D , and

- Laura Weiss Roberts , M.D., M.A.

Search for more papers by this author

Suicide is the tragic outcome of a diverse interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Suicide affects all people and has long been considered a complex, but preventable, cause of disease burden throughout the world. Despite improvements in awareness and treatment, suicide continues to account for 1 million deaths annually—one life lost every 40 seconds. Suicide occurs in the general population at a rate of 11.3/100,000 in the United States. Suicide attempts occur even more frequently. For every death by suicide, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports that an additional 25 nonfatal suicide attempts (100-200 for youth) are estimated to occur. Suicide attempts are associated with approximately 500,000 emergency room visits every year in the United States alone ( 1 ). Risk for suicide cuts across mental disorders, socioeconomic status, age, and gender, and “psychological autopsy” studies indicate that nearly all suicide decedents have at least one psychiatric disorder at the time of death ( 2 ).

The detection, prediction, and management of suicidality present a diverse array of ethical challenges. Suicidal behaviors, now defined in a standardized nomenclature ( 3 ), exist on a spectrum, ranging in severity from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts to death by suicide. In seeking to prevent self-harm, clinicians ideally will use what have emerged as “best practice” techniques to assess suicide risk and intervene if necessary, yet fear of losing a patient to suicide, and worry surrounding malpractice claims, are significant concerns reported by clinicians ( 4 ). This may result in two kinds of responses: 1) a “better safe than sorry” approach, where suicidal risk is overestimated, and 2) an avoidant or dismissive approach, where risk is inadequately assessed, and thereby underestimated ( 5 ). An overestimation of suicide risk may deprive a patient of their rights and may misuse clinical resources. On the other hand, an underestimation of suicide risk may jeopardize the safety of the patient and increase the liability of the provider ( 6 ). Inaccurate assumptions about best practice treatment of suicidal behaviors may also heighten the fear and worry of clinicians. For example, despite advances in evidence-based suicide risk assessment and treatment, an inaccurate belief may persist that hospitalization is the optimal clinical response to a distressed patient. This is a problem, given the absence of evidence supporting the enduring efficacy of acute hospitalization, particularly compared to randomized controlled behavioral treatment trials reporting reduction of risk using psychosocial outpatient interventions for suicidal behaviors ( 7 , 8 ). Dispelling myths, or inaccurate beliefs that may result in harmful consequences to the patient or clinician, is thus critical within a discussion of ethical considerations on this topic. Ethically and legally, best practice and reasonable care should likewise be distinguished from the prediction of suicide, or the legal construct of foreseeability ( 9 ). Given its low rate of occurrence, suicide is not an outcome that clinicians can reliably predict. Rather, evidence-driven approaches and established guidelines in the assessment and management of suicide risk represent the optimal ethical approach in caring for patients at risk for suicide.

Several cardinal medical ethical principles in psychiatry shape ethical approaches to the care of patients at risk for suicide and inform “best practices” in this aspect of clinical care ( 10 ):

Respect for Persons —a deep regard for an individual’s worth and dignity;

Autonomy —self-governance;

Beneficence —the responsibility to act in a way that seeks to provide the greatest benefit and, for this reason, the notion of clinical excellence is an imperative in fulfilling this principle.

Other key principles include:

Fidelity —faithfulness to the interests of the patient;

Nonmaleficence —primum non nocere (“first, do no harm”);

Veracity —the duty of truth and honesty;

Justice —the act of fair treatment, without prejudice;

Privacy —protection of patients’ personal information; and

Integrity —honorable conduct within the profession.

Best practices in suicide risk assessment and management

Approaching the patient—informed consent.

Informed consent to treatment and risk management may be defined as informing the patient of all procedures that will be used in the evaluation and management of suicide risk, clinical decision-making, and emergency assessment and referral practices ( 9 ). Like evidence-based psychosocial interventions for suicidal behaviors, this process should be highly transparent, collaborative, and initiated at the onset of treatment to disclose ethical and legal responsibilities of the provider, limits to confidentiality, and to enhance understanding of treatment ground rules ( 11 , 12 ). In deeply respecting the rights and dignity of the individual, this process strongly supports the Autonomy of the patient, as well as Respect for Persons .

Informed consent to suicide risk management can be collaboratively described as working together to keep the patient safe. Such language compassionately stresses the equal importance of both the patient and clinician in safety planning. Assessment procedures, routinized clinical-decision making, and specific circumstances prompting an emergency referral should be made unambiguous as part of the informed consent process. Adequate time and effort should be devoted to answering questions and confirming understanding of such procedures. For example, a clinician can inform the patient about questions he or she may expect in a suicide risk assessment, under what circumstances they will be asked, how this information will be used, and any limits to confidentiality. The collaborative, transparent aspect of this approach embraces principles of Privacy and Veracity , as well as the dignity and the self-governing rights of the patient. Beneficence is also represented in informed consent, given that explanation of best-practice assessment both standardizes assessment and routinizes clinical decision-making ( 13 ). In this way, informed consent maximizes benefits, while minimizing risks to the fullest extent possible.

An opportunity to strengthen the therapeutic relationship is inherent to this process. Suicidal ideation is associated with significant distress, yet patients may be reluctant to disclose symptoms because of fear of stigma or judgment. This may promote shame, isolation, and secrecy in treatment. Informed consent of risk assessment and management has the potential to directly address these fears and compassionately correct harmful misperceptions, if present. Providing diagnostic feedback about risk (i.e., education that suicidal ideation is a symptom of depression, among a constellation of other diagnostic criteria) may empower the patient with accurate information about his or her symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment plan, whereas education about suicidal symptom severity and risk categorizations may address fears of involuntary hospitalization. The collaborative and transparent nature of assessments may here again be emphasized, with risk categorizations delineated (e.g., minimal, mild, moderate, serious, imminent risk) ( 14 ). The way in which risk categorizations guide decision-making may also be made explicit to clarify questions about circumstances that would prompt emergency referrals (e.g., informing the patient that referral for involuntary services will only be pursued when risk is judged to be serious/imminent, the patient is offered emergency services on a voluntary basis, and he or she refuses voluntary services).

Undertaking the next steps—assessing and managing patients at-risk

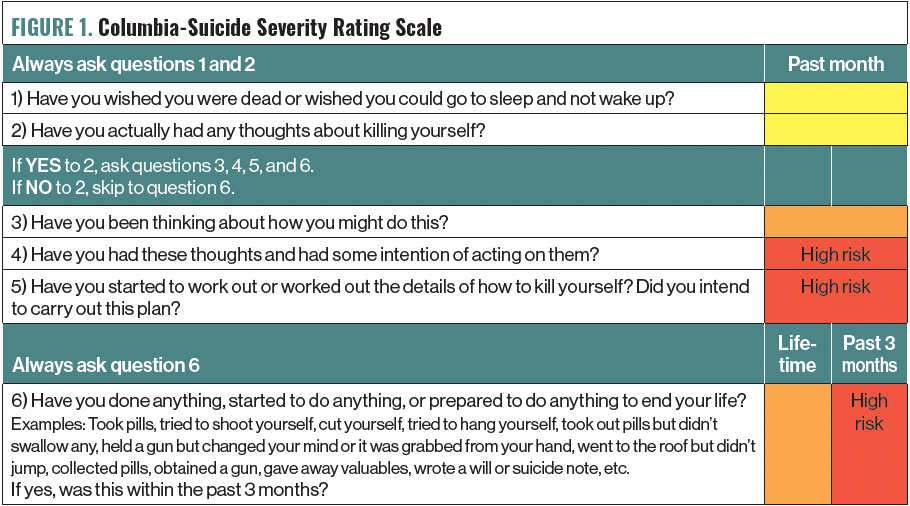

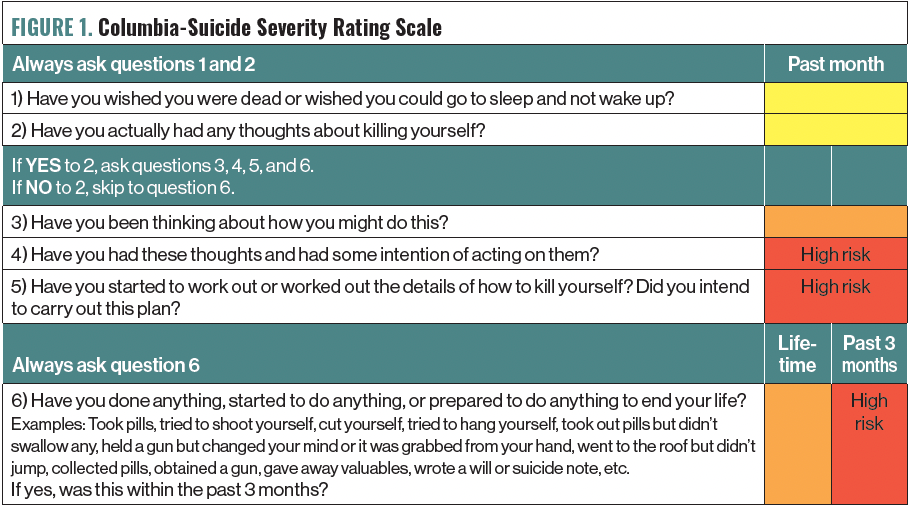

The ability to perform an adequate assessment of suicidality and to manage patients who are at risk for suicide is an essential clinical skill for psychiatrists. Because clinical excellence is vital to fulfilling one’s professional obligations, the ability to assess and manage high-risk patients is also an ethical commitment for psychiatrists. Psychiatric practitioners, acting on knowledge from training years ago, may rely on inadequate interventions, such as the “no-harm contract,” and may not be as knowledgeable about empirically supported behavioral treatments for suicidal behaviors ( 9 , 15 ). Best practice techniques in standardized suicide risk assessment and evidence-based clinical decision-making are strongly rooted in clinical science, and emerging standards that derive from the field of suicidology. Modern clinical practice requires knowledge and use of 1) suicide risk factors and warning signs; 2) standardized suicide risk assessment frameworks, risk categorizations, and decision-tree rules for outpatient management; and 3) suicidal symptom severity scales. For a list of evidence-based guidelines and materials, we refer clinicians to those listed in Figure 1 .

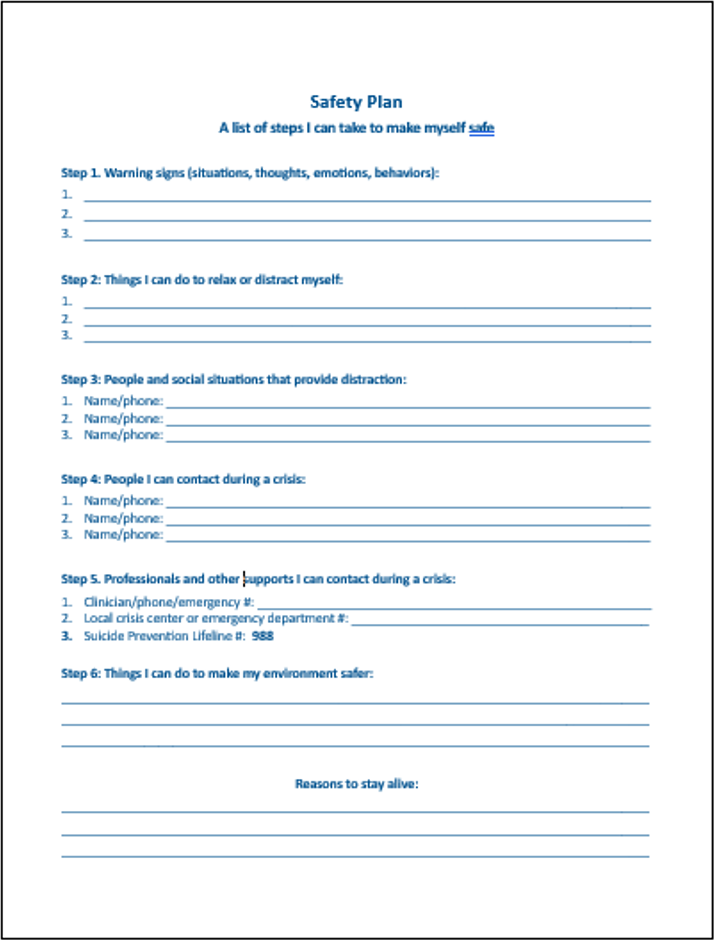

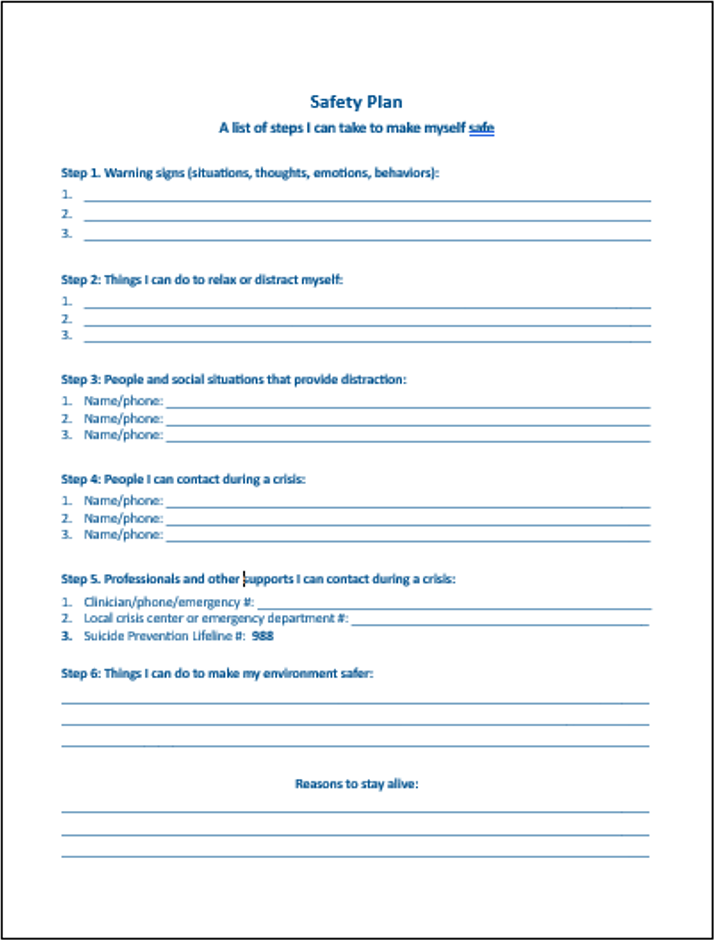

Evidence-based suicide risk assessment frameworks structure the assessment process in an alliance-based and nondefensive manner. Symptom measures (clinician administered or self-reported) are straightforward to use, and they aid the clinician in assessing the severity of suicidal symptoms across empirically derived domains (i.e., onset, duration, frequency, and intensity of suicidal ideation; suicidal intent and planning; history of suicidal behaviors; access to means for a suicide attempt). The structure, severity, and intensity of symptoms translate into quantifiably different risk categorizations, and may be reliably addressed using established measures. For example, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is a brief measure of suicidal ideation and behaviors that may be used in clinical practice to assess and regularly monitor suicide risk. It has excellent psychometric properties and is accessible and available in 103 languages; administration training is also offered in its use for research and clinical practice ( Figure 1 ). Among those at high risk for suicide, the use of evidence-based interventions, particularly those informed by cognitive-behavioral frameworks, is associated with a significantly decreased risk for suicide attempts, in some cases, reducing risk by half ( 8 , 16 ). In outpatient management of suicide risk, safety planning may be used to identify emergency resources, as well as cognitive and behavioral coping strategies, for the patient to elicit during a suicidal crisis.

Safety planning is highly tailored to the individual and is patient-driven, preferably with the patient identifying and recording his or her own internal coping strategies, in addition to mental health resources (e.g., contact information for local hospitals and emergency clinics, 24-hour crisis hotlines). Safety planning should be comprehensive, concise, and easily accessible and available to the patient. As with evidence-based psychosocial psychotherapies, safety planning is collaborative, transparent, and stresses agency on the part of the patient during the crisis. This honors the Autonomy of the patient, Respect for Persons , as well as Nonmaleficence, in protecting a patient from harm.

Throughout the processes of suicide risk assessment and the management of patient safety, wise and thoughtful clinicians use additional strategies to uphold the highest standards of care: 1) consultation with colleagues, and possible use of decisions by consensus, for difficult or complex cases; 2) regular documentation (i.e., risk level, action taken, safety planning); 3) diligence surrounding continuity of care, given that attrition in treatment is common, yet dangerous, for this high-risk group; and 4) continued education in suicidology. Beyond these strategies, mental health professionals carry an implicit ethical obligation to work to dispel myths about suicide, raise awareness about suicide prevention, and remove language that may be inaccurate, misleading, and potentially harmful to patients ( 9 ). Removal of harmful language related to suicidal behaviors, and dissemination that promotes suicide prevention, values the principles of Autonomy , Respect for Persons , Beneficence , and Nonmaleficence . Deconstructing misunderstandings about suicide is a clear expression of these ethical ideals. For instance, the myth that suicidal “gestures” should be “ignored” rather than “gratified” with a clinical response should be challenged—a dismissive approach to risk assessment is always inappropriate. When a patient endorses or behaves in a manner that suggests suicidality, it must be taken seriously and should be recognized as an opportunity for intervention that may prevent loss of life. Another harmful myth includes the belief that asking about suicidal thoughts and plans may produce suicidality—that questions regarding suicide create “iatrogenic” conditions. This is not grounded in clinical science. Research suggests that assessing suicidal thoughts and risk regularly and frequently does not exacerbate symptoms ( 17 ). Myths like these may discourage questioning about suicidal ideation and increase stigma and, in this way, thwart intervention and suicide prevention efforts. To help clarify optimal ways of addressing these difficult issues with patients, particularly with subgroups that may have heightened risk, several professional and advocacy organizations have worked together to propose guidelines for reporting on suicide to prevent language or nomenclature that may sensationalize or stigmatize suicide or result in suicide contagion. These guidelines, available online by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, are an excellent resource for clinicians. One recommendation from such guidelines, which may be easily adopted into our daily nomenclature, is removal of the term “committed suicide” and replacement with “death by suicide.” Rationale is based on the stigma often tied to descriptions of suicide, in this case nuanced by negative connotations of the verb “committed,” as it is typically only used to describe sins or crimes. Dissemination of accurate, nonjudgmental information regarding suicide and its prevention is thus an expression of professional Integrity as well as fulfillment of the obligations of Beneficence and Nonmaleficence . These foundational principles are embraced both in continuing education (e.g., CE credits, curriculum development of residency training) and promotion of suicide prevention awareness.

Case vignette

Jane is a 46-year-old physician employed full-time at an emergency room, where she has worked for 2 years. She very recently ended her marriage of 8 years and has no children. She began feeling depressed around the time of her divorce 6 months ago and sought treatment from a psychiatrist. Jane reports having only a few friends in the area and becoming more isolative following the separation. She states that she felt depressed only one other time in her life—in college, for approximately 1 year.

Diagnosis and treatment

Jane was diagnosed with major depressive disorder—recurrent type with moderate severity—and initiated weekly psychotherapy with a psychiatrist. Jane was prescribed an SSRI, as well as a hypnotic for insomnia. Difficulty falling asleep began during her marital separation. She reports significant distress about the insomnia, which appears worsened by her rotating, extended shift work schedule. Jane recently reported thoughts of suicide—although she quickly stated that she would never act on such thoughts. This prompted questions from her psychiatrist about the frequency and quality of such thoughts, as well as her history of hospitalizations and past suicidal behaviors. She reported that she had been hospitalized once, when she was 20 years old, following a suicide attempt, but noted that she was “all screwed up back then.” The method of the attempt was by overdose, which required medical treatment. Regarding her current symptoms, Jane stated that on several occasions in the past week she thought about driving off the road and “ending it all.” Her psychiatrist asked when the symptoms began, and whether she had made plans for a suicide attempt. Jane denied any plans or preparation for an attempt, and said the thoughts began after signing her divorce papers several weeks ago.