A Summary and Analysis of Margaret Atwood’s ‘Happy Endings’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Happy Endings’ is a short story (or, perhaps more accurately, a piece of metafiction) which was first published in Margaret Atwood’s 1983 collection, Murder in the Dark . The story offers six alternative storylines which feature a relationship between a man and a woman.

Because of its postmodern and metafictional elements, ‘Happy Endings’ requires a few words of analysis to be fully understood. Before we begin, it might be worth summarising the plot (or plots) of the various storylines which Atwood presents to us.

‘Happy Endings’: plot summary

The story is divided into eight sections, the first six of which posit six different storylines. In the first one, labelled ‘A’, John and Mary meet and fall in love and get married. They both have good jobs and buy a nice house, and in time, they have children. When the time comes, they retire, enjoy their hobbies, and die.

In the second storyline, labelled ‘B’, Mary falls in love with John but John doesn’t love Mary back. He uses her for sex and she hopes that he will come to love (or at least need) her, in time. He never takes her out to a restaurant and instead comes round to hers and she cooks for him.

When her friends tell her he is cheating on her with another woman named Madge, she takes an overdose, hoping that John will discover her and feel so guilty that he’ll marry her. However, this doesn’t happen and she dies, and John marries Madge.

In the third storyline, ‘C’, John is an older married man who is having an affair with Mary, who is twenty-two. She really likes James, who is the same age as her, but he is too young and free to be tied down to a relationship. She takes a shine to John because he is older and worried about losing his hair, and this evokes pity in her.

John, meanwhile, is married to Madge. When Mary ends up having sex with James, John discovers them both and buys a handgun and shoots them dead, before killing himself. Madge, his widow, subsequently marries a man named Fred.

In ‘D’, Fred and Madge are happy together until a tidal wave approaches their coastal home and they narrowly escape. However, they remain together.

In ‘E’, Fred has a bad heart, and eventually dies; afterwards, Madge devotes herself to charity work. However, the narrator acknowledges that these details can be changed: Madge could be the one who is unwell, and Fred might take up bird-watching (rather than charity work) when she dies.

In the final scenario, ‘F’, the narrator suggests that the story can be made less middle-class by making John a revolutionary and Mary a secret agent who starts a relationship with him in order to spy on him. However, the story will still ultimately come to resemble ‘A’.

‘Happy Endings’ concludes with two brief sections in which the narrator (author? Atwood herself?) observes that the endings of all of these stories are the same, ultimately: John dies and Mary dies. After all, death is the ending that comes to all of us, and therefore to all characters. This is the only true authentic ending.

Having treated endings, the narrator remarks that beginnings are more fun, but mostly people are interested in the middle bits. Plot is, fundamentally, just one thing happening after another. The questions of ‘how’ something happens and ‘why’ it does are more interesting, and require attention.

‘Happy Endings’: analysis

‘Happy Endings’ is an example of metafiction : self-conscious fiction that is itself about fiction. It is, in other words, a story about stories and storytelling. Rather than work at creating a realist picture of John and Mary, the two protagonists of ‘Happy Endings’, so that we immerse ourselves in the story and view them as ‘real’ people, Atwood deliberately distances us from them, keeping them at arm’s length by reminding us that they are nothing more than authorial constructs.

Much of Atwood’s story is about delineating the six different scenarios, each of which involves a relationship between a man and a woman.

But as the story develops, the author breaks in on her characters more and more, ‘breaking the fourth wall’ to remind us that they are mere ciphers and that the things being described do not exist outside of the author’s own head (and the reader’s: Atwood’s fiction, and especially the short pieces contained in Murder in the Dark , are about how we as readers imagine those words on the page and make them come alive, too).

Why does Atwood do this? Partly, one suspects, because she wishes to interrogate both the nature of romantic plots in fiction and readers’ attitudes towards them. It’s a commonplace that happy endings in romantic novels ‘sell’: it gives readers what they want. Boy meets girl, girl falls in love with boy, and after various rocky patches they end up living, in the immortal words, ‘happily ever after’.

Atwood wants to put such plot lines under the microscope, as it were, and subject them to closer scrutiny. By the time we get to the fifth plot, ‘E’, the narrator is happily encouraging us to view the plot details as interchangeable between Fred and Madge, as if they don’t really matter. After all, do they? Perhaps the more important details are, as the closing paragraphs of ‘Happy Endings’ have it, not What but How and Why. Character motivation is more important than what they do or what is done to them.

Of course, as so often in Margaret Atwood’s fiction, there’s a feminist angle to all this. Relationships are not equal in a society where men have things easier than women, and the third of Atwood’s six scenarios, in which Mary is the key player, makes this point plainly.

Freedom, Atwood tells us, isn’t the same for girls as it is for boys, and while James is off on his motorcycle, she is forced by societal expectations to do other things. (It is not that she isn’t free herself – she is, after all, carrying on an affair with a married, older man even though society wouldn’t exactly view that kindly – but her freedoms are of a different kind. A woman motorcycling across America on her own would not feel as safe, for one, as a man doing so.)

In the last analysis, ‘Happy Endings’ is a kind of postmodern story about stories: postmodern because it freely and self-consciously announces itself as metafiction, as being more interested in how stories work than in telling a story itself.

But within the narratives Atwood presents to us, she also addresses some of the inequalities between men and women, and exposes how relationships are rarely a level playing field for the two sexes.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Analysis of Margaret Atwood’s Happy Endings

Analysis of Margaret Atwood’s Happy Endings

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on May 25, 2021

An innovative and oft-anthologized story that demonstrates the arbitrariness of any author’s choice of an ending, “Happy Endings” offers six different endings from which the reader may choose. “Happy Endings” was first published in the Canadian collection Murder in the Dark (1983) and then became available in the United States in Good Bones and Simple Murders (1994). Intentionally written in only 1,500 words, the story contains little plot, little character development, and little motivation. Readers, however, should not be deceived: Margaret Atwood is, according to the critic Reingard M. Nischik, “a chronicler of our times, exposing and warning, disturbing and comforting, opening up chasms of meaning as soon as she closes them, and challenging us to question conventions and face up to hitherto unarticulated truths” (159). “Happy Endings” is a story about writing a story, with thoughtful advice to both readers and would-be writers. In this unusual tale she demonstrates why “who and what” are insuff cient; the reader must ask (and the writer must supply) “how and why.” In addition to analyzing the appropriateness of the six endings, the reader might profit from comparing “Happy Endings” to Robert Coover’ s “The Babysitter,” in which the author offers several possibilities of what happens to the babysitter, leaving the decision to the reader’s imagination; and Akira Kurosawa’s 1951 film Roshomon , which depicts the rape of a bride and the murder of her husband through various eyewitness accounts; it demonstrates the near-impossibility of arriving at the actual “truth” of the events.

Atwood’s technique differs from that of Coover and Kurosawa, however, in that she fl eshes out nothing: Indeed, the six possible endings to the story of John and Mary are written as a skeletal outline. She opens with the words, “John and Mary meet. What happens next? If you want a happy ending, try A.” (1).

In A, John and Mary live a richly fulfilling life in terms of careers, sex life, children, vacations, and retirement, until they die. In Ending B, however, Mary loves John but he does not return her love, instead using and abusing her in classical doormat fashion. When Mary learns of John’s affair with Madge, she commits suicide, John marries Madge, and we are told to move to Ending A. In Ending C, John is an older man married to Madge and the father of two children. He falls for the 22-year-old Mary, but when he finds her in the arms of James, he shoots all three of them. Madge marries a man named Fred and proceeds to Ending A. In Ending D, Fred and Madge are the sole survivors of a tidal wave, and, despite the loss of their home, they are grateful to have survived the calamity that killed thousands and continue to Ending A.

Ending E follows Fred to his death of a “bad heart.” Madge soldiers on with charity and volunteer work in Ending A, until she dies of cancer—or, if the reader prefers, becomes guilt-ridden or begins bird-watching. Finally, for those who find Endings A through E “too bourgeois,” Atwood suggests making John and Mary spies and revolutionaries. Still, though, they will end up at Ending A because, after all, “this is Canada” (3). The only authentic ending, says Atwood, is this one: “ John and Mary die. John and Mary die. John and Mary die. ” As the critic Nathalie Cooke points out, “For Atwood, writing is a fascinating but dark art—one where shadows lurk, not only in the subject matter . . . but also in the author’s role as a double being, and in the writing process itself, in which the writer must not only face the darkness, but learn to see in and through it” (19). As Atwood suggests to the readers at the conclusion of “Happy Endings,” that process is achieved by understanding motivation through asking “how” and “why.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY Cooke, Nathalie. Margaret Atwood: A Critical Companion. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004. Nischik, Reingard M. “Margaret Atwood’s Short Stories and Shorter Fictions.” In The Cambridge Companion to Margaret Atwood, edited by Coral Ann Howells, 145– 160. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Share this:

Categories: Literature , Short Story

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , appreciation of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , Canadian Literature , criticism of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , guide of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , Literary Criticism , Margaret Atwood , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings appreciation , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings criticism , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings guide , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings notes , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings plot , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings story , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings structure , Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings themes , plot of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , story of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , structure of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , summary of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings , themes of Margaret Atwood's Happy Endings

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Disguised as Fiction: “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood Essay (Review)

Introduction, works cited.

The only happy ending is the absence of it. In her short story, Canadian writer Margaret Atwood rebuts the idea of happy endings in fiction and life, since the author argues that every story always has the same end, which is death (Atwood 326). Thus, in her story, Atwood employs a vast range of repetitions of words and sentence structures, so that to demonstrate a recurrent character of any fictional plot, which focuses upon the ending.

The story presents a brilliant example of metafiction. Therefore, it describes how, due to the author, the plot of any story should be revealed. Besides, Margaret Atwood emphasizes the questions, which should be answered by any author. These questions are “How?” and “Why?”, instead of the commonplace “What?” that is always the same.

Under the coverage of a short story, Margaret Atwood disguises the essay about story-telling. The author focuses upon the universal ending of a story. She describes it in the Aversion and refers to it in every other part of the story. Thus, Atwood centers her idea around the fact that it is a common mistake to write the story for the sake of its ending. Any author needs to focus his/her attention upon the development of the story.

Through her metafiction story, Margaret Atwood brings up the idea of true-to-life writing. This concept has a long scholarly history and was regarded by many scientists in their research works. For instance, Keith Oatley, in her study on fiction, explored how fictional plots can become facts for the readers. Due to the scientist, fiction is a simulation of life, which resembles computer simulations. Therefore, Oatley argues that any fictional plot possesses huge psychological power since it makes the readers experience certain emotions. The readers usually transmit this experience into real life. Consequently, the author of fiction has to consider the impact he/she can produce upon the reader through the plot of the story. It is, thus, crucial to consider the development of this plot and to relate it to the true life, instead of concentrating upon the effective closure of the fictional story (Oatley 101).

The story is structurally divided into 6 parts that are marked by letters. The A part of the text provides the background version of the whole story. It refers to two characters – Mary and John. The author chooses the technique of listing the facts from the personages’ lives, rather than developing their common story. Atwood does not provide the readers with any particular ideas about Mary and John’s personalities. Though the author uses some adjectives to characterize the occupations of Mary and John (challenging, stimulating), it does not allow the readers to perceive what these occupations are. Therefore, the A version of the story is a raw account of fundamental parts of human life: birth-marriage-death.

The following versions of the story provide some variations of the plot development and introduce some additional characters (Madge, James, and Fred). In the BF parts, Atwood considers the feelings and inner thoughts of the personages. For instance, in the B version, the author verifies Mary’s emotions and her attitude towards John with the true nature of this man. C version provides the readers with some reflections upon a betrayal. In this part, the author describes John’s despair at the moment when he finds Mary cheating on him with James. The two following versions of the text provide the scenarios of events that happened in Fred and Madge’s lives. The D version outlines the story about the tidal wave that destroyed the couple’s life, while in the E version, Atwood dwells on the experience that Madge had to go through struggling against Fred’s disease. Thus, the author demonstrates that plot development is the only significant part of the story.

The last version of the text is a straight example of metafiction. The author tries to involve the reader in the process of writing and lists some instructions on the possible plot developments of the story. Atwood embraces the 2nd person narration so that to underline that any fictional story can change if the reader alternates the central actions that are revealed in it. However, neither author nor the reader can change anything in the story if he/she alternates its ending. In this part, Margaret Atwood also recapitulates the main point of her story in a straightforward way. The author claims that there are no happy or unhappy endings. Life endings are always the same. Thus, the main obligation of any author, due to Margaret Atwood, is to develop an exciting plot in the story and to relate this plot to real life.

To sum it up, Margaret Atwood’s short story on happy endings is an example of an essay disguised as fiction. In a form of plot verifications, the author focuses on the idea that every story has a single authentic ending, which she expresses by the sentence: “John and Mary die” (Atwood 326). Since the author supports the idea of fiction being the representation of true life, Atwood states that there is no need for the author to concentrate upon the ending of the story. It is crucial to pay attention to the realistic and exciting representation of plot actions.

Atwood, Margaret. “Literature: A Portable Enthology.” Happy Endings . Ed. Janet E. Gardiner. Boston, NY: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012. 326-329. Print.

Oatley, Keith. “Why Fiction May Be Twice as True as Fact: Fiction as Cognitive and Emotional Simulation.” Review of General Psychology 3.2 (2009): 101-117. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, January 25). Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood. https://ivypanda.com/essays/happy-endings-by-margaret-atwood/

"Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood." IvyPanda , 25 Jan. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/happy-endings-by-margaret-atwood/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood'. 25 January.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood." January 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/happy-endings-by-margaret-atwood/.

1. IvyPanda . "Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood." January 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/happy-endings-by-margaret-atwood/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Disguised as Fiction: "Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood." January 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/happy-endings-by-margaret-atwood/.

- “Lusus Naturae” by Margaret Atwood

- The "You Fit Into Me" Poem by Margaret Atwood

- "The Handmaid's Tale" a Novel by Margaret Atwood

- J.Joyce’s “Eveline” and the Notion of Paralysis

- The Art of Being Concise

- Who Is Charles Dickens?

- Paul's Case: A Study in Temperament

- “Yellow Wallpaper” – A Creepy Shade of Yellow

Happy Endings

Margaret atwood, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Sex and Gender

In “Happy Endings,” Atwood describes a variety of scenarios involving stock characters she calls John and Mary in order to reflect upon gender and sexuality. Throughout these iterations of character arcs and story stereotypes, Atwood presents sexuality as heavily conditioned by social and gender norms, most often to the detriment of women. In particular, women’s sexuality is often socially dependent upon men, whose needs are put first, over and above women’s. The story’s title itself…

Relationships and Marriage

Throughout the story, the character arcs of John , Mary , and others are all described in relation to one another, most often in terms of romance and eventual marriage. Atwood highlights the way in which these events function less as interesting narrative developments and more as necessary fulcrums in the plot, moving the story along inexorably toward its ending. Once marriage happens, the story’s usually over—barring plot-worthy tragedies like natural disaster or disease—and the…

Storytelling Tropes

Beyond illustrating the problematic dynamics underpinning sexual and romantic relationships, “Happy Endings” is concerned with the nature of storytelling itself. “Happy Endings” details the broad plot arcs of a variety of different stories, poking fun at the traditional structure that underpins so many of them. In doing so, Atwood asserts that the broad strokes of a life—who sleeps with whom, who marries whom, who dies and how—as less interesting than the day to day trials…

Throughout “Happy Endings,” the various romantic scenarios and plot features the story describes all end in death. In all of the archetypal plot elements she caricatures, Atwood emphasizes that death and loss are a fundamental part of any story. While marriage may be an ending of a sort, of the “lived happily ever after” variety, it’s never the true ending: death is the ultimate conclusion of any story, and there’s no use pretending otherwise. Accepting…

Analysis of Margaret Atwood's "Happy Endings"

Six Versions Provide Unique Perspectives

Craig Sunter/CJS*64/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

- Short Stories

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Children's Books

- Ph.D., English, State University of New York at Albany

- B.A., English, Brown University

"Happy Endings" by Canadian author Margaret Atwood is an example of metafiction . That is, it's a story that comments on the conventions of storytelling and draws attention to itself as a story. At approximately 1,300 words, it's also an example of flash fiction . "Happy Endings" was first published in 1983, two years before Atwood's iconic " The Handmaid's Tale ."

The story is actually six stories in one. Atwood begins by introducing the two main characters , John and Mary, and then offers six different versions—labeled A through F—of who they are and what might happen to them.

Version A is the one Atwood refers to as the "happy ending." In this version, everything goes well, the characters have wonderful lives, and nothing unexpected happens.

Atwood manages to make version A boring to the point of comedy. For example, she uses the phrase "stimulating and challenging" three times—once to describe John and Mary's jobs, once to describe their sex life, and once to describe the hobbies they take up in retirement.

The phrase "stimulating and challenging," of course, neither stimulates nor challenges readers, who remain uninvested. John and Mary are entirely undeveloped as characters. They're like stick figures that move methodically through the milestones of an ordinary, happy life, but we know nothing about them. Indeed, they may be happy, but their happiness seems to have nothing to do with the reader, who is alienated by lukewarm, uninformative observations, like that John and Mary go on "fun vacations" and have children who "turn out well."

Version B is considerably messier than A. Though Mary loves John, John "merely uses her body for selfish pleasure and ego gratification of a tepid kind."

The character development in B—while a bit painful to witness—is much deeper than in A. After John eats the dinner Mary cooked, has sex with her and falls asleep, she stays awake to wash the dishes and put on fresh lipstick so that he'll think well of her. There is nothing inherently interesting about washing dishes—it's Mary's reason for washing them, at that particular time and under those circumstances, that is interesting.

In B, unlike in A, we are also told what one of the characters (Mary) is thinking, so we learn what motivates her and what she wants . Atwood writes:

"Inside John, she thinks, is another John, who is much nicer. This other John will emerge like a butterfly from a cocoon, a Jack from a box, a pit from a prune, if the first John is only squeezed enough."

You can also see from this passage that the language in version B is more interesting than in A. Atwood's use of the string of cliches emphasizes the depth of both Mary's hope and her delusion.

In B, Atwood also starts using second person to draw the reader's attention toward certain details. For instance, she mentions that "you'll notice that he doesn't even consider her worth the price of a dinner out." And when Mary stages a suicide attempt with sleeping pills and sherry to get John's attention, Atwood writes:

"You can see what kind of a woman she is by the fact that it's not even whiskey."

The use of second person is particularly interesting because it draws the reader into the act of interpreting a story. That is, second person is used to point out how the details of a story add up to help us understand the characters.

In C, John is "an older man" who falls in love with Mary, 22. She doesn't love him, but she sleeps with him because she "feels sorry for him because he's worried about his hair falling out." Mary really loves James, also 22, who has "a motorcycle and a fabulous record collection."

It soon becomes clear that John is having an affair with Mary precisely to escape the "stimulating and challenging" life of Version A, which he is living with a wife named Madge. In short, Mary is his mid-life crisis.

It turns out that the barebones outline of the "happy ending" of version A has left a lot unsaid. There's no end to the complications that can be intertwined with the milestones of getting married, buying a house, having children, and everything else in A. In fact, after John, Mary, and James are all dead, Madge marries Fred and continues as in A.

In this version, Fred and Madge get along well and have a lovely life. But their house is destroyed by a tidal wave and thousands are killed. Fred and Madge survive and live as the characters in A.

Version E is fraught with complications—if not a tidal wave, then a "bad heart." Fred dies, and Madge dedicates herself to charity work. As Atwood writes:

"If you like, it can be 'Madge,' 'cancer,' 'guilty and confused,' and 'bird watching.'"

It doesn't matter whether it's Fred's bad heart or Madge's cancer, or whether the spouses are "kind and understanding" or "guilty and confused." Something always interrupts the smooth trajectory of A.

Every version of the story loops back, at some point, to version A—the "happy ending." As Atwood explains, no matter what the details are, "[y]ou'll still end up with A." Here, her use of second person reaches its peak. She's led the reader through a series of attempts to try to imagine a variety of stories, and she's made it seem within reach—as if a reader really could choose B or C and get something different from A. But in F, she finally explains directly that even if we went through the whole alphabet and beyond, we'd still end up with A.

On a metaphorical level, version A doesn't necessarily have to entail marriage, kids, and real estate. It really could stand in for any trajectory that a character might be trying to follow. But they all end the same way: "John and Mary die . " Real stories lie in what Atwood calls the "How and Why"—the motivations, the thoughts, the desires, and the way the characters respond to the inevitable interruptions to A.

- Biography of Margaret Atwood, Canadian Poet and Writer

- Analysis of "Oliver's Evolution" by John Updike

- A Summary of Margaret Atwood's The Edible Woman

- Analysis of 'The School' by Donald Barthelme

- Analysis of 'How to Talk to a Hunter' by Pam Houston

- Eliza Doolittle's Final Monologues from 'Pygmalion'

- The Great Love Story of Cupid and Psyche

- Important Quotes From 'The Handmaid's Tale'

- An Early Verson of Flash Fiction by Poet Langston Hughes

- 'The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas' Analysis

- Mary Wollstonecraft: A Life

- How to Write a Character Analysis

- The 6 Creepiest Fairy Tales

- Analysis of The Bear Came Over the Mountain by Alice Munro

- 5 Tips to Help You Read a Play Script

- 3 Reasons Why 'The Handmaid’s Tale' Remains Relevant

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

“Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood: A Critical Analysis

“Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood was first published in the literary magazine “Canadian Forum” in 1983.

Introduction: “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

Table of Contents

“Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood was first published in the literary magazine “Canadian Forum” in 1983. The story gained popularity and was later included in Atwood’s short story collection “Murder in the Dark.” Atwood’s unique approach to storytelling and her focus on metafiction drew readers’ attention to “Happy Endings.” The story presents multiple scenarios that explore the possibilities of human lives, and the different paths that individuals can take. It challenges the traditional notion of a happy ending and the idea that life can be reduced to a simple, linear narrative. Atwood’s use of a detached and ironic tone, as well as her commentary on the writing process, adds to the story’s popularity and relevance.

Main Events in “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- Story A: The Idealized Ending (ll. 10-20): This path offers a seemingly perfect scenario. John and Mary find love, marry, and achieve professional success. They raise well-adjusted children, enjoy stimulating hobbies, and eventually die peacefully (ll. 13-19). This ending serves as a benchmark against which the narrator dissects the artificiality of happily-ever-after narratives.

- Story B: The Unhappy Reality (ll. 21-54): This path presents a stark contrast. John exploits Mary for his own gratification, treating her with disregard (ll. 22-27). Mary withers under his emotional neglect, leading to depression and suicide (ll. 48-50). John remains unaffected and continues his life with another woman, Madge (ll. 52-54). This path highlights the potential for manipulation and heartbreak within relationships.

- Story C: The Loveless Triangle and Violence (ll. 55-97): This path explores the complexities of love and desire. John, an insecure older man, seeks solace with Mary, who is young and unattached (ll. 56-58). Mary uses John for comfort while pining for James, her true love (ll. 59-63). John, burdened by his failing marriage, feels trapped (ll. 64-66). The discovery of Mary’s infidelity triggers a violent outburst. John kills Mary, James, and himself in a desperate act (ll. 88-92). John’s wife, Madge, remains oblivious and finds happiness with a new partner (ll. 95-97). This path emphasizes the destructive potential of unfulfilled desires and societal pressures.

- Story D: Nature’s Intervention (ll. 98-110): This path introduces an external force that disrupts a seemingly idyllic life. Fred and Madge live contentedly until a devastating tidal wave destroys their home (ll. 99-101). The narrative shifts to focus on the cause of the wave and their escape (ll. 102-110). This path injects a sense of powerlessness in the face of nature’s unpredictable forces.

- Story E: Facing Mortality (ll. 111-122): This path explores the inevitability of death. Fred, seemingly healthy, suffers from a heart condition (l. 112). Despite this, they cherish their time together until his death (ll. 113-114). Madge dedicates herself to charity work, finding solace in helping others (ll. 116-117). This path offers a more realistic portrayal of a happy life eventually ending, but with a sense of purpose and acceptance.

Literary Devices in “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- Allusion – a reference to a person, place, or event in history, literature, or culture. Example: “Mary and John met at the beach, just like Romeo and Juliet.”

- Anaphora – repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses or sentences. Example: “And so on. And so on. And so on.”

- Irony – a contrast between what is said and what is meant or what is expected and what actually happens. Example: “John had always dreamed of being a millionaire, but in the end, he won the lottery and lost all his money.”

- Juxtaposition – placing two or more ideas, characters, or objects side by side for the purpose of comparison and contrast. Example: “In the story, John is presented as the perfect husband, while Mary is depicted as flawed and insecure.”

- Metaphor – a comparison of two unlike things without using the words “like” or “as”. Example: “Life is a journey, and we are all just travelers on this road.”

- Paradox – a statement that seems contradictory or absurd but is actually true. Example: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

- Personification – giving human qualities to non-human objects or animals. Example: “The sun smiled down on us, and the wind whispered through the trees.”

- Repetition – the use of the same word or phrase multiple times for emphasis. Example: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.”

- Satire – the use of humor, irony, or exaggeration to expose and criticize foolishness or corruption in society. Example: “The story mocks the unrealistic expectations of traditional romance novels.”

- Simile – a comparison of two unlike things using the words “like” or “as”. Example: “The stars shone like diamonds in the sky.”

- Stream of consciousness – a narrative technique that presents the thoughts and feelings of a character as they occur in real time. Example: “The story shifts abruptly from one character’s point of view to another, mimicking the flow of thoughts and emotions.”

- Symbolism – the use of objects, characters, or actions to represent abstract ideas or concepts. Example: “The apple symbolizes temptation and sin in the story.”

- Tone – the author’s attitude toward the subject or characters in the story. Example: “The tone of the story is ironic and detached, highlighting the artificiality of traditional happy endings.”

- Understatement – a statement that intentionally downplays the significance or magnitude of something. Example: “After winning the Nobel Prize, the author remarked, ‘It’s a nice honor, I guess.'”

- Unreliable narrator – a narrator whose credibility is compromised, often because they are mentally unstable, dishonest, or biased. Example: “The narrator in the story is unreliable, as evidenced by their contradictory and inconsistent descriptions of the characters and events.”

Characterization in “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

While the story focuses on plot variations, Atwood provides glimpses into the characters, revealing their motivations and flaws:

- John : Across the stories, John appears self-centered and emotionally unavailable.

- In Story A, she blends seamlessly into the idealized narrative (ll. 10-20).

- In Story B, she embodies the vulnerability of being emotionally neglected, ultimately succumbing to despair (ll. 48-50).

- In Story C, she appears caught between affection for John and love for James, highlighting the complexities of desire (ll. 59-63).

- Madge : John’s wife in Story C, Madge remains largely unseen. She represents the “happily ever after” John fails to achieve, existing primarily as a contrast to Mary (ll. 95-97). In Stories D and E, she embodies resilience, rebuilding her life after loss (ll. 99-122).

- In Story A (Happy Ending), he fulfills the stereotypical role of the charming husband, but his true nature remains unexplored (ll. 10-20).

- In Story B, he exploits Mary for his physical desires without reciprocating her affection (ll. 22-27).

- In Story C, his insecurity and neediness drive him into a loveless affair with Mary (ll. 55-58). His inability to cope with his failing marriage and Mary’s betrayal leads to a violent act (ll. 88-92).

- Even in Stories D and E (where he’s not the central character), he remains somewhat of an enigma, existing primarily in relation to Mary or Madge.

Overall Character Portrayal:

- Archetypes: Atwood utilizes archetypes like the charming prince (John in Story A) and the femme fatale (Mary in Story B) to subvert traditional expectations.

- Limited Development: The characters are not fully fleshed out, serving as tools to explore the narrative variations and the artificiality of happily-ever-after tropes.

- Focus on Relationships: The story prioritizes how characters interact and manipulate each other, rather than their individual personalities.

Major Themes in “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

Writing style in “happy endings” by margaret atwood.

Margaret Atwood’s writing style in “Happy Endings” is characterized by its concise and straightforward prose, which effectively conveys the author’s ironic and satirical tone. Atwood uses active voice verbs to draw the reader in and maintain their engagement throughout the story. The narrative style is fragmented, with abrupt shifts in tone and perspective that challenge the reader’s expectations and highlight the artificiality of conventional storytelling. Atwood’s use of metafiction further reinforces this theme, as she breaks down the fourth wall and comments on the process of storytelling itself. The result is a provocative and thought-provoking work that challenges the reader to question their assumptions about the nature of storytelling and the meaning of “happy endings.”

Literary Theories and Interpretation of “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- Metafiction : Atwood’s story can be viewed through the lens of metafiction, a genre that self-consciously reflects on the act of storytelling itself ([Hutcheon, 1980]). Her use of a narrator who directly addresses the reader (“Now try How and Why,” l. 121) and the exploration of various plot possibilities highlight the constructed nature of fiction and challenge readers’ expectations of a singular, definitive narrative.

- Feminist Theory : A feminist critique of “Happy Endings” reveals how Atwood portrays the limitations placed on women within societal structures. Characters like Mary (Stories B & C) endure emotional manipulation and societal pressure to conform to idealized roles, highlighting the challenges women face in relationships ([Showalter, 2011]). The story deconstructs the stereotypical “happily ever after” that often objectifies women and undermines their agency.

- Postmodernism : The fragmented structure and multiple endings in “Happy Endings” resonate with postmodern themes. Atwood subverts traditional narrative expectations, rejecting a linear plot with a clear resolution ([Jameson, 1991]). The story reflects a postmodern view of the fragmented nature of experience and the instability of meaning-making in a world without absolute truths.

- Reader-Response Theory : Atwood’s use of second-person narration (“you can see what kind of a woman she is…” l. 45) and direct addresses to the reader (“So much for endings,” l. 118) embody reader-response theory ([Iser, 1978]). She invites active participation in the story, encouraging readers to consider their own experiences and expectations of love, relationships, and happy endings. The multiple endings emphasize the importance of the reader’s interpretation in shaping the meaning of the text.

- Existentialism : An existentialist reading of “Happy Endings” recognizes the characters’ grappling with meaninglessness and mortality. John’s despair at his aging and failed relationships (Story C) and the characters’ ultimate deaths reflect the existentialist concern with human struggles to find purpose in an indifferent universe ([Sartre, 1943]). The various unhappy endings suggest the characters’ inability to control their destinies and the inevitability of death.

Questions and Thesis Statements about “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- How does Atwood’s use of metafiction contribute to her exploration of the concept of “happy endings” in literature?

- Thesis statement: Through the use of metafiction, Atwood challenges traditional notions of happy endings in literature and forces the reader to confront the harsh realities of human relationships and the unpredictability of life.

- In what ways does Atwood use irony and satire to critique societal expectations of relationships and gender roles in “Happy Endings”?

- Thesis statement: Through the use of irony and satire, Atwood exposes the limitations and unrealistic expectations placed on individuals in romantic relationships, highlighting the gendered power dynamics that underlie these societal expectations.

- How does Atwood use repetition and variation of the story’s structure to convey her message about the nature of storytelling and human existence?

- Thesis statement: By utilizing repetition and variation in the structure of the story, Atwood comments on the nature of storytelling and the unpredictable nature of human existence, challenging readers to question their own expectations of narrative form and the stories they consume.

- In what ways does Atwood use the character Mary to subvert traditional gender roles and expectations in “Happy Endings”?

- Thesis statement: Through the character of Mary, Atwood challenges traditional gender roles and expectations, highlighting the constraints placed on women in romantic relationships and the societal pressure to conform to traditional norms.

- How does the absence of traditional narrative structure in “Happy Endings” contribute to the story’s message about the unpredictable nature of life and relationships?

- Thesis statement: The absence of traditional narrative structure in “Happy Endings” highlights the unpredictable nature of life and relationships, challenging readers to question their own expectations of story structure and the inevitability of certain endings.

Short Question/Answer Topics for “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- Deconstructing the “Happily Ever After”: Atwood’s Purpose: Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings” isn’t your typical love story. Her purpose lies in satirizing and deconstructing the conventional idea of a “happily ever after” (l. 118) often found in traditional narratives. By presenting six variations of the same story’s beginning (“John and Mary meet,” l. 10), each leading to vastly different outcomes, Atwood reveals the limitations and predictability of these narratives. The story becomes less about the characters themselves and more about exposing the artificiality of the “happily ever after” trope and the lack of universality in happy endings (ll. 10-122).

- Active Participation: The Impact of Second-Person Narration: Atwood’s use of second-person narration is a significant tool in “Happy Endings.” By directly addressing the reader with phrases like “Now try How and Why” (l. 121), she dismantles the traditional roles of reader and writer. The reader is thrust into the story, becoming an active participant who questions their own expectations of a happy ending. Witnessing the different choices characters make in each variation (“you can see what kind of a woman she is…” l. 45) and the resulting consequences adds to the story’s complexity and depth. The reader is forced to confront the lack of a singular, satisfying conclusion, mirroring the messy realities of life.

- Unveiling the Craft: Metafiction and its Contribution: “Happy Endings” is a prime example of metafiction, a genre that self-consciously reflects on the act of storytelling itself. Atwood’s use of metafiction allows her to explore themes of power, control, and the limitations of storytelling. The narrator directly addresses the reader, questioning the purpose of plot and happy endings (“So much for endings,” l. 118). By exposing the conventions and limitations of traditional narratives through the multiple endings, Atwood challenges the power dynamics between author and reader, and between characters and their pre-determined narratives. She questions the way stories are often used to exert control and manipulate the reader’s perception of reality.

- “And Then”: A Repetition with Meaning: The repeated phrase “and then” throughout “Happy Endings” is far from insignificant. It serves to emphasize the predictability and repetitiveness often found in traditional narratives. Each variation begins with “and then,” highlighting the formulaic nature of storytelling and its reliance on clichés (ll. 21, 55, 98, 111). This repetition underscores the limitations of storytelling and how narratives can be used to reinforce idealized and often unrealistic social norms and expectations. By highlighting this repetitiveness, Atwood critiques how stories can oversimplify real-life complexities and shy away from the messy realities of human relationships.

Literary Works Similar to “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

- Cat’s Cradle (1963) by Kurt Vonnegut: This satirical science fiction novel employs a dark and playful tone akin to Atwood’s. It dissects themes of war, religion, and technology, exposing societal flaws akin to the deconstruction of happy endings.

- “Her Body and Other Stories” (2017) by Carmen Maria Machado: This collection of short stories, much like “Happy Endings,” challenges expectations around love and relationships. Machado’s unsettling narratives explore themes of gender, sexuality, and the body in innovative ways, mirroring Atwood’s exploration of unconventional love stories.

- If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979) by Italo Calvino: This work, similar to “Happy Endings,” blurs the lines between fiction and reality. A metafictional exploration of reading and the reader-author relationship, Calvino’s novel playfully dismantles traditional storytelling tropes, echoing Atwood’s use of metafiction.

- Pale Fire (1962) by Vladimir Nabokov: Nabokov’s complex novel, like “Happy Endings,” challenges readers’ assumptions. Through an unreliable narrator and a blurring of truth and fiction, “Pale Fire” compels readers to question their understanding of the narrative, mirroring Atwood’s deconstruction of happy endings.

- The Vegetarian (2015) by Han Kang: This disturbing and thought-provoking novel, similar to “Happy Endings,” delves into the darker aspects of human relationships. Kang explores themes of alienation, violence, and the female experience, challenging traditional narratives of domesticity, much like Atwood’s subversion of conventional love stories.

Suggested Readings: “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

Scholarly articles:.

- Brooker, Peter. “‘Atwood’s Gynocentric Narratives? “Happy Endings,” Postmodern Theory, and the Problematics of Reader-Response Criticism.'” Studies in Canadian Literature , vol. 16, no. 1 (1991), pp. 71-87. [JSTOR]. (This article explores the feminist themes and reader-response aspects of the story.)

- Millicent, Barry. “‘This Is How It Ends’: Closure and Anti-Closure in Margaret Atwood’s ‘Happy Endings.'” Essays on Canadian Writing , no. 63 (1994), pp. 147-162. [JSTOR]. (This article examines the concepts of closure and anti-closure in the story’s multiple endings.)

- Howells, Coral Ann. _ Margaret Atwood . Routledge, 2006. (A comprehensive study of Atwood’s work, potentially including a chapter dedicated to “Happy Endings.” Availability of specific chapters may vary by library.)

- Surgeoner, Catherine. _ Margaret Atwood . Manchester University Press, 2008. (Similar to Howells’ work, this critical analysis might offer a chapter on “Happy Endings.” Check library databases for chapter availability.)

Online Resources:

- GradeSaver: Happy Endings: https://www.gradesaver.com/happy-endings (Offers students a summary, analysis, and helpful resources to understand the story.)

- LitCharts: Happy Endings by Margaret Atwood: https://www.litcharts.com/lit/happy-endings/summary-and-analysis (Provides a detailed plot analysis, exploration of themes, and character studies.)

Related posts:

- “The Use of Force” by William Carlos Williams

- “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” by Ambrose Bierce: Analysis

- “Civil Peace” by Chinua Achebe: Analysis

- “Good Country People” by Flannery O’Connor: Analysis

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Happy Endings

29 pages • 58 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Story Analysis

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: "happy endings".

“Happy Endings” is a short story by Canadian writer Margaret Atwood. After the story’s trio of opening lines, the narrative is divided into five sections, labeled A-F. The story’s opening lines are: “John and Mary meet. What happens next? If you want a happy ending, try A” (43).

The story then moves into Section A, in which John and Mary “fall in love and get married…have jobs they find “stimulating and challenging…buy a house…have two children…who turn out well…retire…[and] die” (43). Atwood concludes this section with the sentence, “This is the end of the story” (43).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,650+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Section B—which theoretically could be skipped to straight from the story’s opening three lines—also feature characters named John and Mary, though it is left somewhat ambiguous as to whether or not these two characters are the same John and Mary found in Section A. Mary falls in love with John, but John only uses Mary for sex. When Mary finds out from friends that John is seeing another woman, Madge , Mary commits suicide, though leaves a suicide note for John and hopes he will find her and save her life. Mary dies, and John marries Madge. Atwood concludes this section by stating “everything continues as in [Section] A” (44).

In Section C, we are again introduced to two characters named John and Mary, and, much like Section B, it’s worth noting that a reader could skip from the opening lines of the story straight to Section C, and have Section C be read largely independently of Sections A and B.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Here, John, who is older, falls in love with Mary, who is twenty-two. Mary meets John at work but is in love with James , “who has a motorcycle and a fabulous record collection” (44). James isn’t in love with Mary. John has two children and is married to Madge. One day, James shows up to Mary’s apartment with marijuana, after which John shows up, finds the two lovers in bed together, and kills them, before killing himself.

Madge, now John’s widow, “marries an understanding man named Fred ,” though only “after a suitable period of mourning” (44). Atwood concludes the section by saying that “everything continues as in A, but under different names” (44).

Section D focuses on Fred and Madge, who would seem to be the same Fred and Madge mentioned in Section C. The two get along well and own a house but a “one day a giant tidal wave approaches” (44). Real estate values decrease, thousands die, but Fred and Madge survive. Again, Atwood concludes this section by saying that everything “continue[s] as in [Section] A” (45).

Section E, which is only four sentences, offers that Fred has a bad heart and dies, after which Madge “devotes herself to charity work until the end of [Section] A” (45). This section concludes with: “If you like, it can be ‘Madge,’ ‘cancer,’ ‘guilty and confused,’ and ‘bird watching’ (45).

Section F, the story’s last section, begins with Atwood again directly addressing the reader, and offering perhaps the story’s most metafictional content to this point. Atwood then asserts that all endings are the same and that “the only authentic ending is the one provided here: John and Mary die. John and Mary die. John and Mary die” (45).

Atwood closes the story by saying plots, and plot, “are just one thing after another, a what and a what and a what. Now try How and Why.” (45).

The citations in this guide refer to the story as it appears in the anthology, The Story and Its Writer , 7th Edition.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Margaret Atwood

Alias Grace

Margaret Atwood

Backdrop Addresses Cowboy

Cat's Eye

Death By Landscape

Hag-Seed: William Shakespeare's The Tempest Retold

Helen of Troy Does Countertop Dancing

Lady Oracle

Life Before Man

Oryx and Crake

Rape Fantasies

Stone Mattress

The Blind Assassin

The Circle Game

The Edible Woman

The Handmaid's Tale

The Heart Goes Last

The Landlady

Featured Collections

Canadian Literature

View Collection

How to Write a Believable Happy Ending

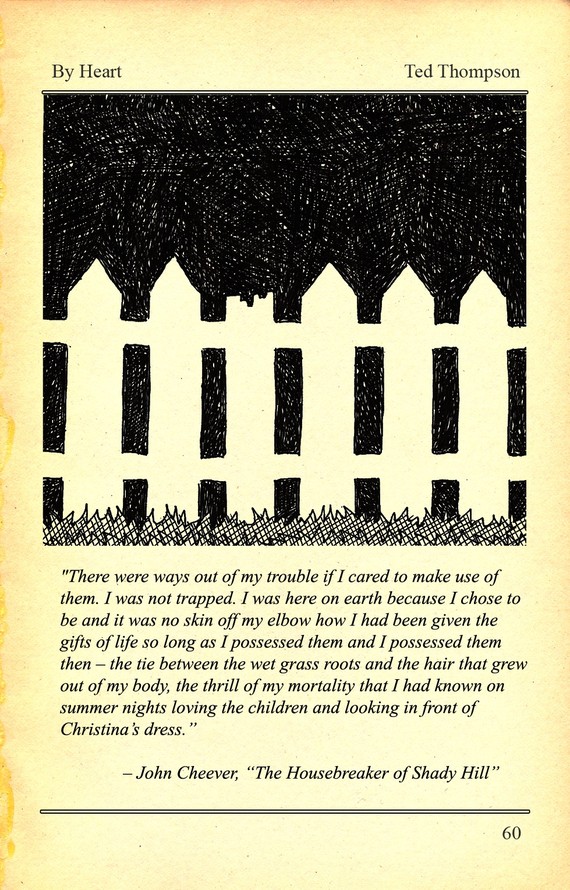

As author Ted Thompson learned from John Cheever, a redemptive resolution doesn't erase the darkness of a story, but instead finds the light within it.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Claire Messud, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Happy endings are famously rare in literature. We turn to great books for emotional and ethical complexity, and broad-scale resolution cheats our sense of what real life is like. Because complex problems rarely resolve completely, the best books tend to haunt and unnerve readers even as they edify and entertain.

This is especially true in writing about the suburbs, perhaps because that setting has served as a symbolic happy ending to the broader American cultural narrative. It’s no accident that the best-known stories about the upper middle class—books like John Updike’s Rabbit, Run ; Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road ; Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm , to name a few, and films like American Beauty —tend to have exceptionally brutal finales. These works, in their final moments, devastate and eviscerate their characters—and with them the notion that suburban living is the proper happy ending for the American life.

Recommended Reading

Why is there financing for everything now.

The Weekly Planet : The Best Way to Donate to Fight Climate Change (Probably)

Dads Prefer Sons, Moms Prefer Daughters

When I spoke with Ted Thompson, author of The Land of Steady Habits , we discussed how John Cheever’s ecstatic and ultimately redemptive vision makes him singular among the suburbs’ sad bards; Cheever is rare among writers for his ability to consistently pull off believable happy endings. Thompson unpacked his favorite Cheever story, an overlooked gem called “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill,” and showed how the master makes a joyful moment complex, palpable, and real. He went on to explain how Cheever has challenged him to write about people—and the landscape he knows best—with greater generosity, and to always balance darkness with light.

The Land of Steady Habits , Thompson’s first book, takes its name from an informal state nickname for Connecticut. (The author grew up in Westport.) Anders Hill, a celebrated Wall Street financier quietly disturbed by the human and environmental costs of his profit-making, decides to amputate himself from the two dominant features of his life: his job and his wife. Unmoored, he begins to suspect his former responsibilities did much more than hem him in—they also gave him crucial shape.

Thompson is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop; his fiction has appeared in Tin House and Best New American Voices . He spoke to me by phone from his home in Brooklyn.

Ted Thompson: I first came across “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” when I was still living in Iowa City, the year after I graduated from the Writers’ Workshop. In those days I’d keep two or three books on my writing desk, not to read seriously but to open and dip into while I worked—just to hear the rhythm of certain people’s sentences and let their music guide me. Around that time, Cheever’s sentences especially worked a kind of magic on me. I used to love to pick up that thick, red-orange Collected Stories and leaf through it when I got stuck. One day, in the middle of a draft of a doomed short story I was working on, I opened randomly to “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” and began to read it for the first time. It was early in the morning, very quiet and still, and I remember being taken with the tone, and the sort of tossed-off mastery of those first sentences:

My name is Johnny Hake. I’m thirty-six years old, stand five feet eleven in my socks, weigh one hundred and forty-two pounds stripped, and am, so to speak, naked at the moment and talking into the dark.

I thought I’d read a paragraph or two, just the setup, to see how he slips into a story, but the next thing I knew I was halfway through the thing, way beyond what I had allowed myself, and reading it aloud to my computer screen.

I’m always surprised that it’s not one of his canonized stories, up there with “The Swimmer” and “Goodbye, My Brother” as what people first think of when they hear this writer’s name. It has the hallmarks of all the things that I love about Cheever: a kind of humorous premise, a character on the edge of emotional collapse, a world that is superficially stiff but always undercut by a kind of wildness. And more strikingly, his prose just soars through the whole thing (hence the urge to speak it aloud, which I have nearly every time I read it). Still, when I mention the story to others, they rarely know it. Or if they do, it hasn’t struck them. And it’s not one of the stories that often gets read at the Cheever celebrations, like the one I went to a few years ago at the 92nd Street Y. I’ve always wondered why.

It’s a pretty simple story on the surface. A man with a family in the suburbs loses his job at company that manufactures parablendeum, which seems to be kind of color-tinted Saran wrap. (I’m pretty sure Cheever invented this word because neither Google nor I seem to have heard of it.) He gets fired, decides to go into business on his own, and does a pretty pathetic job of it. Quickly, things get bleak. He runs out of money and can’t bring himself to tell his wife. And once that charade starts, he feels that his only hope is to break into his neighbors’ houses and steal their cash in the middle of the night.

He lives in a fictional neighborhood called Shady Hill, an opulent hamlet not unlike like the one in Ossining, New York, where Cheever really lived. One night after a late dinner party, he returns to house of his rich hosts and breaks into it. He tiptoes into their bedroom where they’re sleeping, sees a pair of pants hanging over a chair, and fishes out his friend’s wallet. There’s $900 cash inside. He flees with all of it into the night. This one act haunts the narrator for the rest of the story, and very nearly undoes him completely. He becomes totally convinced of his criminality. He starts seeing theft and sin everywhere he goes. He starts feeling as though everyone knows he’s done wrong. He starts to behave like person being eaten alive by guilt.

And still, his desperation is such that he has to break into a second neighbor’s house when he needs more money. He knows he won’t be caught: These friends are drunks, “booze fighters,” he calls them, and there’s no way they’ll wake up. As he’s walking to their house—this where Cheever becomes difficult to describe—the narrator’s shame and guilt have escalated to a place where he’s about to have a nervous breakdown. But rather than come apart at the seams, the natural world intervenes. The sky opens and it rains.

Now this is definitely dangerous territory for a writer. Precipitation has been tempting young writers as a dramatic climax for a long time: Write yourself into a corner and you always have the weather. To me, it’s the deus ex machina of everyday spiritual crises—guilt and sin cleansed by rain—and it just might be the most handy cop-out available. (When I get caught in the rain, I have yet to find God—I mostly get cold and wet and pissed.) But somehow, in the way the prose functions, Cheever, goddamn, he pulls it off. Despite all of my resistances, I believe the character really is relieved of his guilt. It’s a beautiful, redemptive passage, one I’ve probably read out loud a hundred times:

I was thinking sadly about my beginnings, about how I was made by a riggish couple in a midtown hotel after a six-course dinner with wines, and my mother had told me so many times that if she hadn’t drunk so many Old-Fashioneds before that famous dinner I would still be unborn on a star. And I thought about my old man and that night at the Plaza and the bruised thighs of the peasant women of Picardy and all the brown-gold angels that held the theatre together and my terrible destiny. While I was walking towards the Pewter’s, there was the harsh stirring and all the trees and gardens, like a draft on a bed of fire, and I wondered what it was until I felt the rain on my hand and face, and I began to laugh. I wish I could say that a kindly lion had set me straight, or an innocent child, or the strains of distant music from some church, but it was no more than the rain on my head—the smell of it flying up my nose—that showed me the extent of my freedom from the bones in Fontainebleau and the works of a thief. There were ways out of my trouble if I cared to make use of them. I was not trapped. I was here on earth because I chose to be. And it was no skin off my elbow how I had been given the gifts of life so long as I possessed them, and I possessed them then—the tie between the wet grass roots and the hair that grew out of my body, the thrill of my mortality that I had known on summer nights, loving the children, and looking in front of Christina’s dress.

I don’t completely know how Cheever lifts us straight off the page and into the skies here. The more that I look at it and try to pick it apart the less I can make sense of it. The only thing that I can say is that through the music of that language, and perhaps the repetition of certain images from earlier in the story, he’s able to conjure in me a convincing experience of something that is about as abstract and fuzzy as you can get: a man being set free of his conscience.

I also can’t imagine anyone else being able to write “the bruised thighs of the peasant women of Picardy,” or “the brown-gold angels that held the theatre together.” So strange, these images! And yet there’s something about the unexpectedness of them that disarms me, and opens me to whatever else the story wants to do.

And what that is, at least to me, comes in this line: “The tie between the wet grass roots and the hair that grew out of my body.” God, that just flays me. It comes out of nowhere—the narrator comes alive to beauty in that moment, and it enables him, ennobles him, to make a dignified choice about how to live his life. He can decide what kind of man he wants to be. And so he turns around and goes home, whistling in the dark.

After that, his life sort of comes back together—he’s rehired at the job and returns the money that he stole. Ultimately the story has a comedic structure: The world gets more and more disordered, but in the end it’s put back together anew.

This is one of the things that’s so apparent when you’re reading Cheever: his openness to redemptive beauty. His suburbs aren’t corrupt, awful places. They’re not places that have dark, ugly roots that he’s trying to expose—which is often the basic project in the subgenre of American suburban fiction (and film and TV). Cheever’s world is one that, no matter how buttoned-up it may be, is continuously ruptured by unexpected beauty. For me, finding this on the page was a revelation. You aren’t supposed to write about suburban neighborhoods like that—to acknowledge their beauty, and locate great meaning in it. It’s pretty clear why writers like Jim Harrison spend so much time describing the natural world, but we’ve become almost conditioned to believe that manicured suburban aesthetics are only an illusion to conceal some fundamental rottenness.

In Cheever, this isn’t really the case. No matter how cruel his characters are to each other, no matter how much they disappoint each other or what sins they commit, there’s still a sense that there’s light in his world. It comes through in the way he describes trees so well, and smells and breezes and the ocean. The landscape balances out the torment of the tortured characters within it—and sometimes, that beauty is even enough to save them.

Writing a happy ending that feels meaningful is probably one of the hardest tricks in literature. There’s a lot of comedy out there (particularly in movies and television) that follows that ancient structure of the world falling apart and then being put back together again, but so much of it feels like, okay, those problems were solved and now I can forget about them. You don’t want a literary story to have that effect—you want it to have a resonance with the reader beyond the last page, and I feel like it’s a lot easier to do with tragedy than comedy.

There’s an essay I think about a lot by Italo Calvino called “Lightness,” in which he talks about levity as a virtue in literature and storytelling: He argues for the necessity of lightness, and insists we need it if we’re going to be telling dark and hard truths. A guiding image of the piece is the way that Perseus cannot look at Medusa’s ugliness directly—only by watching her reflected in his shield can he see her without becoming petrified to stone. (As Calvino says, “Perseus’s strength always lies in a refusal to look directly, but not in a refusal of the reality in which he is fated to live.”) I suppose that this was a part of what I was hoping to do in my own book—to explore the wounded and lost, yes, and to render the deficiencies and strains of even the most conventional and responsible ways of life. But at the same time I was invariably thinking of Cheever’s wide-eyed wonder, and was inspired to look again at the memories of my own childhood in that way, to find reverence for the frozen marshlands of those Connecticut towns, and the stone archways of the Merritt Parkway, and for all those suited men riding the shoreline trains.

Happy Endings

By margaret atwood, happy endings summary and analysis of sections a – c.

The narrator announces that John and Mary meet, and asks the reader what will happen next.

She directs them toward version A, which she labels as a happy ending. In version A, John and Mary fall in love, work fulfilling jobs, and buy a house. They have two children, take enjoyable vacations, and retire, each with their own interesting hobbies. Eventually, John and Mary die.

In version B, Mary loves John but John does not love Mary. Instead, he uses her for pleasures like sex, food, and company. Mary feels compelled to please John, and she cooks for him whenever he comes to her apartment. He is a selfish lover, but Mary cannot help wanting to be with him.

Everyone in Mary's life tells her that John is not good for her, but she believes deep down that she can change him and that he is a better person than he seems. Her friends tell her that they have seen John at a restaurant with another woman named Madge . Heartbroken, Mary attempts to overdose on sleeping pills. She secretly hopes John will appear at the last minute and save her, but he does not, and Mary dies.

John eventually marries Madge and lives the same life described in version A, with Madge instead of Mary.

In version C, John is married to Madge but is having an affair with the much younger Mary. Mary pities John because of his age, but does not love him. She loves James , a twenty-two-year-old man who is not ready to commit. James spends his time riding around on his motorcycle.

One day, James brings marijuana to Mary's and they get high and have sex. John finds them together, and is so overcome with despair that he purchases a handgun and kills James, Mary, and himself. Madge mourns John and eventually marries a man named Fred , and Madge and Fred continue to live out the life described in version A.

The beginning half of " Happy Endings " is characterized by three different versions of two characters' lives, with the characters themselves shifting in personality, age, and temperament among each of the stories.

Readers will immediately notice the uniqueness of such a structure for a short story: rather than simply relaying a single narrative about characters John and Mary, the author instead presents the characters' and their stories as changeable and arbitrary. In so doing, the author immediately draws readers' attention to the artifice of fiction-writing and the relationship between writers and readers.

The pick-your-own structure of the story ultimately dramatizes how writers create and alter characters to better communicate with readers, and how the concept of "character" in fiction writing is fundamentally unstable because characters are not real people. In this way, the story introduces itself not as a story with a singular narrative but as a commentary on the nature of storytelling more generally.

The author also presents a cynical interpretation of its titular "happy endings." Version A of John and Mary's lives is notably mundane, punctuated only by happiness, comfort, and fulfillment. This "happy ending," the story suggests, does not make for interesting reading or writing.

Instead, she presents alternatives like versions B and C, where John and Mary both experience unrequited love for one another. In both B and C, this unrequited love or emotional disparity between the characters fosters conflict and drama, two elements of fiction that many would argue are absolutely necessary for producing a story of quality. These versions are notably longer and more complex, thereby suggesting that "happy endings" like version A – two people who fall in love and grow old together – are not as compelling as stories fraught with sadness, anger, confusion, and hardship.

Happy Endings Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Happy Endings is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for Happy Endings

Happy Endings study guide contains a biography of Margaret Atwood, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Happy Endings

- Happy Endings Summary

- Character List

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Satire — “Happy Endings” by Margaret Atwood

"Happy Endings" by Margaret Atwood

- Categories: Satire Short Story

About this sample

Words: 1959 |

10 min read

Published: Mar 14, 2019

Words: 1959 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read

Analysis Of Happy Endings by Margaret Atwood

Works cited.

- Atwood, M. (1983). Happy Endings. In Dancing Girls and Other Stories (pp. 41-45). McClelland and Stewart.

- Atwood, M. (1983). Happy Endings. The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction (8th ed., pp. 289-291). W.W. Norton & Company.

- Hemingway, E. (1927). Hills Like White Elephants. In Men Without Women (pp. 402-407). Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Wyche, D. (2010). The Cycles of Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants". The Hemingway Review, 29(2), 59-78. doi:10.1353/hem.0.0123

- Mead, R. (2015). Deconstructing the Hero: A Critical Analysis of John in Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings”. Interdisciplinary Humanities, 32(2), 39-47.

- Mead, R. (2018). Subverting Stereotypes: The Role of Mary in Margaret Atwood’s “Happy Endings”. Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée, 45(1), 42-56. doi:10.1353/crc.2018.0004

- Smith, J. (2013). The Use of Imagery in Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants". The Hemingway Review, 33(1), 90-95. doi:10.1353/hem.2013.0003

- Johnson, L. (2017). Symbols and Symbolism in Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants". Explicator, 75(3), 193-195. doi:10.1080/00144940.2017.1359460

- Davis, C. (2012). From "Once Upon a Time" to "Happy Endings": Hemingway's Conceptualization of Storytelling in "Hills Like White Elephants". Journal of the Short Story in English, (58), 119-131. doi:10.4000/jsse.1160

- Atwood, M. (1994). Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing. Cambridge University Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1117 words

1 pages / 551 words

5 pages / 2236 words

4 pages / 1748 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele in 2017, is a satirical horror film that delves into white insecurities about black sexuality and the lingering effects of slavery on the national psyche (Johnston 2). Premiering on January 23, [...]

In Kurt Vonnegut's short story "Harrison Bergeron," the author employs satire to critique the concept of equality taken to its extreme in a dystopian society. This aspect of satire in the story is particularly relevant in [...]

Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein has become a classic of Gothic literature, known for its eerie and atmospheric setting. The novel has been praised for its creation of a dark and foreboding world that mirrors the inner turmoil [...]

Satire is a powerful form of comedy that uses humor to criticize and ridicule societal issues, often through exaggeration and absurdity. South Park is known for its use of satire to address a wide range of topics, including [...]

Writer and satirist Jonathan Swift stated that “satire is a sort of glass, wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own” (Swift). Such beholders, as Swift mentions, use satiric narrative to convey [...]

Throughout history there have been no shortages of western Christian writers. In a field so competitive, only those who have created work that is theologically influential are remembered by the masses. Martin Luther is [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

10 Most Satisfying Movie Endings of All Time, According to Reddit

"Baby, you are gonna miss that plane."

While a captivating opening to a movie makes for a key element throughout its runtime, playing a huge role in keeping audiences invested and intrigued, a well-crafted finale is just as important. Endings do not have to be grand to be memorable. However, they should be thoroughly considered and offer proper closure, as a bad landing can easily undo a good film.

Because the final moments in films are so defining – or redefining – and help shape a good story, we look back at some of the best ever provided to cinephiles according to Reddit, where many movie enthusiasts users share their favorite final moments, from Before Sunset to The Truman Show .

10 'Before Sunset' (2004)

The second installment to a beautifully-written trilogy, Before Sunset follows Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke 's characters as they reunite nine years after having an affair. The two share a stroll in Paris, walking over the city and catching up on each other's lives in this Richard Linklater film.

From the heartfelt conversations to the beautiful landscapes it features, there are many great things about the Before trilogy. On Reddit, users agree that the ending to the second entry is one of them: When a user quoted the characters' final lines on the platform, a now-deleted Reddit account highlighted how "good" the film is.

9 'The Shawshank Redemption' (1994)

Starring Morgan Freeman and Tim Robbins , Frank Darabont 's 1994 emotional film The Shawshank Redemption tells the story of the tight bond between two convicts as they find solace and consolation in each other, as well as redemption and friendship.

Spidey10 reveals that, although they know that the book's ending is ambiguous, they're very happy that the movie went on another path and "showed us that Andy and Red reunited on the beach." On top of that, they also highlight how incredible Thomas Newman 's score is.

8 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly' (1966)

This iconic 1966 Spaghetti Western by Sergio Leone stars Clint Westwood in one of his most memorable roles and centers on a race to uncover a fortune in gold buried in a rural cemetery, illustrating the beginning of an uneasy partnership between three men and against a fourth.

In addition to an unforgettable storyline and amazing performances, the landing of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is also what makes it stand out, according to Redditors. " The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly . The grave yard to credits is goated," allthereeses said.

7 'Arrival' (2016)