Theories, Models, & Frameworks

One of the cornerstones of implementation science is the use of theory.

Unfortunately, the vast number of theories, models, and frameworks available in the implementation science toolkit can make it difficult to determine which is the most appropriate to address or frame a research question. There are dozens of theories, models, and frameworks used in implementation science that have been developed across a wide range of disciplines, and more are published each year.

Two reviews provide schemas to organize implementation science theories, models, and frameworks and narrow the range of choices:

Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research (Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2013) Tabak et al’s schema organizes 61 dissemination and implementation models based on three variables: 1) construct flexibility, 2) focus on dissemination and/or implementation activities, and 3) socio-ecological framework level.

Doing Research

Frame your question, ⇥ pick a theory, model, or framework, identify implementation strategies, select research method, select study design, choose measures, get funding, report results.

The authors argue that classification of a model based on these three variables will assist in selecting a model to inform D&I science study design and execution. For more information, check out this archived NCI webinar with presenters Dr. Rachel Tabak and Dr. Ted Skolarus: 💻 Applying Models and Frameworks to D&I Research: An Overview & Analysis .

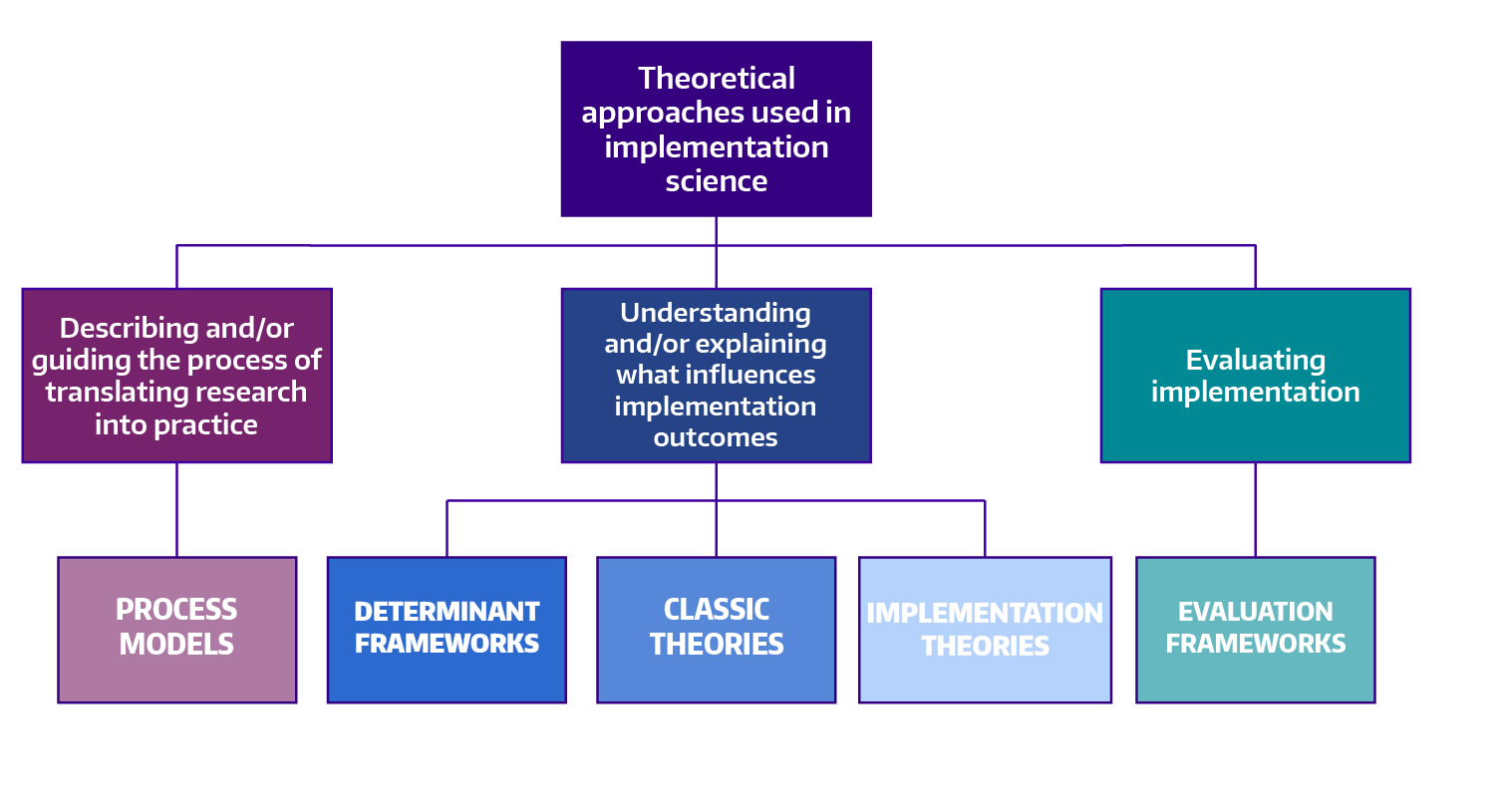

✪ Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks (Nilsen, 2015) Per Nilsen's schema sorts implementation science theories, models, and frameworks into five categories: 1) process models, 2) determinants frameworks, 3) classic theories, 4) implementation theories, and 5) evaluation frameworks.

Adapted from: Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci . 2015;10(1):1-13.

Below, we borrow from Nilsen’s schema to organize overviews of a selection of implementation science theories, models, and frameworks. In each overview, you will find links to additional resources.

Open Access articles will be marked with ✪ Please note some journals will require subscriptions to access a linked article.

What are you using implementation science to accomplish.

- To describe or guide the process of translating research into practice

- To understand and/or explain what influences implementation outcomes

- To evaluate implementation

Process Models

Examples of use.

- ✪ Results-based aid with lasting effects: Sustainability in the Salud Mesoamérica Initiative ( Globalization and Health , 2018)

- ✪ Study Protocol: A Clinical Trial for Improving Mental Health Screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Pregnant Women and Mothers of Young Children Using the Kimberley Mum's Mood Scale ( BMC Public Health , 2019)

- ✪ Sustainability of Public Health Interventions: Where Are the Gaps? ( Health Research Policy and Systems , 2019)

In 2018 the authors refined the EPIS model into the cyclical EPIS Wheel, allowing for closer alignment with rapid-cycle testing. A model for rigorously applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study is available Open Access (✪) from Health & Justice .

- ✪ Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework ( Implementation Science , 2019)

- A Review of Studies on the System-Wide Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Veterans Health Administration ( Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 2016)

- Advancing Implementation Research and Practice in Behavioral Health Systems ( Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 2016)

- ✪ A model for rigorously applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study ( Health and Justice , 2018)

- Characterizing Shared and Unique Implementation Influences in Two Community Services Systems for Autism: Applying the EPIS Framework to Two Large-Scale Autism Intervention Community Effectiveness Trials ( Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 2019)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research: The EPIS framework: A phased and multilevel approach to implementation

- ✪ A two-way street: bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments ( Implementation Science , 2013)

- ✪ “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ Implementing measurement based care in community mental health: a description of tailored and standardized methods ( Implementation Science , 2018)

- ✪ "I Had to Somehow Still Be Flexible": Exploring Adaptations During Implementation of Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Primary Care ( Implementation Science , 2018)

- An Implementation Science Approach to Antibiotic Stewardship in Emergency Departments and Urgent Care Centers ( Academic Emergency Medicine , 2020)

- Using the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) to Qualitatively Assess Multilevel Contextual Factors to Help Plan, Implement, Evaluate, and Disseminate Health Services Programs ( Translational Behavioral Medicine , 2019)

- Stakeholder Perspectives on Implementing a Universal Lynch Syndrome Screening Program: A Qualitative Study of Early Barriers and Facilitators ( Genetics Medicine , 2016)

- Evaluating the Implementation of Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) in Five Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Hospitals ( The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety , 2018)

In 2012 Meyers, Durlak, and Wandersman synthesized information from 25 implementation frameworks with a focus on identifying specific actions that improve the quality of implementation efforts. The result of this synthesis was the Quality Implementation Framework (QIF) , published in the American Journal of Community Psychology . This framework is comprised of fourteen critical steps across four phases of implementation, and has been used widely in child and family services, behavioral health, and hospital settings.

- ✪ Practical Implementation Science: Developing and Piloting the Quality Implementation Tool ( American Journal of Community Psychology , 2012)

- Survivorship Care Planning in a Comprehensive Cancer Center Using an Implementation Framework ( The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology , 2016)

- ✪ The Application of an Implementation Science Framework to Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs: Be a Champion! ( Frontiers in Public Health , 2017)

- ✪ Developing and Evaluating a Lay Health Worker Delivered Implementation Intervention to Decrease Engagement Disparities in Behavioural Parent Training: A Mixed Methods Study Protocol ( BMJ Open , 2019)

- Implementation Process and Quality of a Primary Health Care System Improvement Initiative in a Decentralized Context: A Retrospective Appraisal Using the Quality Implementation Framework ( The International Journal of Health Planning and Management , 2019)

Determinant Frameworks

Learn more:.

- Statewide Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs ( Exceptional Children , 2013)

- Active Implementation Frameworks for Successful Service Delivery: Catawba County Child Wellbeing Project ( Research on Social Work Practice , 2014)

- The Active Implementation Frameworks: A roadmap for advancing implementation of Comprehensive Medication Management in primary care ( Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy , 2017)

For additional resources, please visit the CFIR Technical Assistance Website . The website has tools and templates for studying implementation of innovations using the CFIR framework, and these tools can help you learn more about issues pertaining to inner and outer contexts. You can read the original framework development article in the Open Access (✪) journal Implementation Science .

- ✪ Evaluating and Optimizing the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review ( Implementation Science , 2020)

- ✪ A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Advancing implementation science through real-world applications, adaptations, and measurement ( Implementation Science , 2015)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research: Pragmatic application and scientific advancement of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Dr. Laura Damschroder, National Cancer Institute of NIH Fireside Chat Series )

In 2005, Dr. Susan Michie and colleagues published the Theoretical Domains Framework in BMJ Quality & Safety , the result of a consensus process to develop a theoretical framework for implementation research. The primary goals of the development team were to determine key theoretical constructs for studying evidence based practice implementation and for developing strategies for effective implementation, and for these constructs to be accessible and meaningful across disciplines.

- ✪ Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research ( Implementation Science , 2012)

- ✪ Theoretical domains framework to assess barriers to change for planning health care quality interventions: a systematic literature review ( Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare , 2016)

- ✪ Combined use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF): a systematic review ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and targeted interventions to enhance nurses’ use of electronic medication management systems in two Australian hospitals ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ Hospitals Implementing Changes in Law to Protect Children of Ill Parents: A Cross-Sectional Study ( BMC Health Services Research , 2018)

- Addressing the Third Delay: Implementing a Novel Obstetric Triage System in Ghana ( BMJ Global Health , 2018)

The original framework development article, Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework is available Open Access (✪) from BMJ Quality & Safety .

- Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework ( BMJ Quality & Safety , 2002)

- Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARIHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges ( Implementation Science , 2008)

- ✪ A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework ( Implementation Science , 2010)

- ✪ A Guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation ( Implementation Science , 2011)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research; Pragmatic application and scientific advancement of the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) framework

Classic Theories

In 2017 Dr. Sarah Birken and colleagues published their application of four organizational theories to published accounts of evidence-based program implementation. The objective was to determine whether these theories could help explain implementation success by shedding light on the impact of the external environment on the implementing organizations.

Their paper, ✪ Organizational theory for dissemination and implementation research , published in the journal Implementation Science utilized transaction cost economics theory , institutional theory , contingency theories , and resource dependency theory for this work.

In 2019, Dr. Jennifer Leeman and colleagues applied these same three organizational theories to case studies of the implementation of colorectal cancer screening interventions in Federally Qualified Health Centers, in ✪ Advancing the use of organization theory in implementation science ( Preventive Medicine , 2019).

In 2005 the NIH published ✪ Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice 2.0, an overview of behavior change theories. Below are selected theories from the intrapersonal and interpersonal ecological levels most relevant to implementation science.

There are two intrapersonal behavioral theories most often used to interpret individual behavior variation:

The Health Belief Model : An initial theory of health behavior, the HBM arose from work in the 1950s by a group of social psychologists in the U.S. wishing to understand why health improvement services were not being used. The HBM posited that in the health behavior context, readiness to act arises from six factors: perceived susceptibility , perceived severity . perceived benefits , perceived barriers , a cue to action , and self-efficacy . To learn more about the Health Belief Model, please read "Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model" ( Health Education Monographs ).

The Theory of Planned Behavior : This theory, developed by Ajzen in the late 1980s and formalized in 1991 , sees the primary driver of behavior as being behavioral intention . Through the lens of the TPB, behavioral intention is believed to be influenced by an individual's attitude , their perception of peers' subjective norms , and the individual's perceived behavioral control .

At the interpersonal behavior level , where individual behavior is influenced by a social environment, Social Cognitive Theory is the most widely used theory in health behavior research.

Social Cognitive Theory : Published by Bandera in the 1978 article, Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change , SCT consists of six main constructs: reciprocal determinism , behavioral capability , expectations , observational learning , reinforcements , and self-efficacy (which is seen as the most important personal factor in changing behavior).

Examples of use in implementation science:

The Health Belief Model

- ✪ Using technology for improving population health: comparing classroom vs. online training for peer community health advisors in African American churches ( Implementation Science , 2015)

The Theory of Planned Behavior

- ✪ Assessing mental health clinicians’ intentions to adopt evidence-based treatments: reliability and validity testing of the evidence-based treatment intentions scale ( Implementation Science , 2016)

Social Cognitive Theory

- ✪ Systematic development of a theory-informed multifaceted behavioural intervention to increase physical activity of adults with type 2 diabetes in routine primary care: Movement as Medicine for Type 2 Diabetes ( Implementation Science , 2016)

- Diffusion of preventive innovations ( Addictive Behaviors , 2002)

- ✪ Diffusion of Innovation Theory ( Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics , 2011)

Implementation Theories

- ✪ Implementing community-based provider participation in research: an empirical study ( Implementation Science , 2012)

- ✪ Context matters: measuring implementation climate among individuals and groups ( Implementation Science , 2014)

- ✪ Determining the predictors of innovation implementation in healthcare: a quantitative analysis of implementation effectiveness ( BMC Health Services Research , 2015)

- Review: Conceptualization and Measurement of Organizational Readiness for Change ( Medical Care Research and Review , 2008)

- ✪ Organizational factors associated with readiness to implement and translate a primary care based telemedicine behavioral program to improve blood pressure control: the HTN-IMPROVE study ( Implementation Science , 2013)

- ✪ Towards evidence-based palliative care in nursing homes in Sweden: a qualitative study informed by the organizational readiness to change theory ( Implementation Science , 2018)

- ✪ Assessing the reliability and validity of the Danish version of Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change (ORIC) ( Implementation Science , 2018)

- ✪ Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory ( Implementation Science , 2009)

- ✪ Implementation, context and complexity ( Implementation Science , 2016)

- ✪ Exploring the implementation of an electronic record into a maternity unit: a qualitative study using Normalisation Process Theory ( BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making , 2017)

- ✪ Implementation of cardiovascular disease prevention in primary health care: enhancing understanding using normalisation process theory ( BMC Family Practice , 2017)

- ✪ Using Normalization Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review ( Implementation Science , 2018)

Evaluation Frameworks

The framework development article, ✪ Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda , is available through Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research .

In 2023, Dr. Proctor and several colleagues published Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review in the journal Implementation Science , a scoping review of 'the field’s progress in implementation outcomes research.'

- Toward Evidence-Based Measures of Implementation: Examining the Relationship Between Implementation Outcomes and Client Outcomes ( Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment , 2016)

- ✪ Toward criteria for pragmatic measurement in implementation research and practice: a stakeholder-driven approach using concept mapping ( Implementation Science , 2017)

- ✪ German language questionnaires for assessing implementation constructs and outcomes of psychosocial and health-related interventions: a systematic review ( Implementation Science , 2018)

- The Elusive Search for Success: Defining and Measuring Implementation Outcomes in a Real-World Hospital Trial ( Frontiers In Public Health , 2019)

In 1999, authors Glasgow, Vogt, and Boles developed this framework because they felt tightly controlled efficacy studies weren’t very helpful in informing program scale-up or in understanding actual public health impact of an intervention. The RE-AIM framework has been refined over time to guide the design and evaluation of complex interventions in order to maximize real-life public health impact.

This framework helps researchers collect information needed to translate research to effective practice, and may also be used to guide implementation and potential scale-up activities. You can read the original framework development article in The American Journal of Public Health . Additional resources, support, and publications on the RE-AIM framework can be found at RE-AIM.org . The 2021 special issue of Frontiers in Public Health titled Use of the RE-AIM Framework: Translating Research to Practice with Novel Applications and Emerging Directions includes more than 20 articles on RE-AIM.

- What Does It Mean to “Employ” the RE-AIM Model? ( Evaluation & the Health Professions , 2012)

- The RE-AIM Framework: A Systematic Review of Use Over Time (The American Journal of Public Health , 2013)

- ✪ Fidelity to and comparative results across behavioral interventions evaluated through the RE-AIM framework: a systematic review ( Systematic Reviews , 2015)

- ✪ Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods ( BMC Health Services Research , 2018)

- ✪ RE-AIM in Clinical, Community, and Corporate Settings: Perspectives, Strategies, and Recommendations to Enhance Public Health Impact ( Frontiers in Public Health , 2018)

- ✪ RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review ( Frontiers in Public Health , 2019)

- ✪ RE-AIM in the Real World: Use of the RE-AIM Framework for Program Planning and Evaluation in Clinical and Community Settings ( Frontiers in Public Health , 2019)

Be boundless

Connect with us:.

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

- Policy & Compliance

- Changes Coming To NIH Applications and Peer Review In 2025

Changes Coming to NIH Applications and Peer Review in 2025

This page serves as a central location where you can learn more about multiple changes coming in 2025 that will affect the submission and review of NIH grant applications.

These changes include updates to the peer review and submission of most research project grants, fellowships, and training grants; Common Forms for NIH biographical sketch and Current and Pending (Other) Support; updated instructions for reference letters; and the transition to FORMS-I application instructions. Although each of these initiatives has specific goals, they are all meant to simplify, clarify, and/or promote greater fairness towards a level playing field for applicants throughout the application and review processes.

Upcoming Webinars

Learn more and have the opportunity to ask questions at the following upcoming webinars:

- June 5, 2024 : Webinar on Updates to NIH Training Grant Applications (registration open)

- September 19, 2024 : Webinar on Revisions to the Fellowship Application and Review Process (registration open)

Simplified Review Framework for Most Research Project Grants (RPGs)

NIH is implementing a simplified framework for the peer review of the majority of competing research project grant (RPG) applications, beginning with submissions with due dates on or after January 25, 2025.

Revisions to the NIH Fellowship Application and Review Process

NIH is revising the fellowship review criteria used to evaluate fellowship applications and modifying the PHS Fellowship Supplemental Form to align with the restructured review criteria beginning with submissions with due dates on or after January 25, 2025.

Updates to Training Grant Applications

The NIH Training Program applications are undergoing changes that take effect for submissions with due dates on or after January 25, 2025.

Updates to Reference Letter Instructions for Referees

NIH is updating the instructions for reference letters submitted for due dates on or after January 25, 2025 to provide more structure so letters will better assist reviewers in understanding the candidate’s strengths, weaknesses, and potential to pursue a productive career in biomedical science. Updated instructions will be posted on the NIH Grants page for Reference Letters as soon as they are available (later in 2024).

Updated Application Forms and Instructions (FORMS-I)

NIH is updating application forms to support many of the changes coming in 2025. These new forms will provide the needed form fields to efficiently implement policy updates and align form instructions and field labels with current terminology. Updated application forms will be posted with active funding opportunities in the Fall of 2024, and updated instructions will be available on the How to Apply - Application Guide at that time.

Common Forms for Biographical Sketch and Current and Pending (Other) Support

NIH is adopting the Biographical Sketch Common Form and the Current and Pending (Other) Support Common Form in 2025. Information on the timing and details of implementation are expected in the coming months.

NIH will provide applicants with plenty of training and resources throughout 2024. The below resources discuss the collective changes coming in January 2025. Additional resources for each initiative can be found on their respective pages.

- Overview of Grant Application and Review Changes for Due Dates on or after January 25, 2025: NOT-OD-24-084

- Drop-in slides on changes coming in 2025 (PowerPoint)

This page last updated on: May 17, 2024

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Help Downloading Files

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

Active Implementation is an integrated approach to implementation practice, science, and policy. It has developed from a set of practitioner-scientist activities that span several decades. Current information about Active Implementation is provided in this section. It is important to note that 10 years ago Active Implementation did not exist in this format and it is expected that similar advancements will be made in the next 10 years.

As a mid-range theory of implementation the Active Implementation Frameworks make predictions that are testable in practice. Implementation as a science will advance as implementation practices are operationalized and repeatable so that implementation independent variables (the basis for if-then predictions) can be available for study. Thus, the Active Implementation Frameworks contribute to practice and science in multiple ways.

The information on this website is updated as new learning occurs among the global network engaged in implementation practice, science, and policy.

Download: Active Implementation Overview

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2024

Navigating the future of Alzheimer’s care in Ireland - a service model for disease-modifying therapies in small and medium-sized healthcare systems

- Iracema Leroi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1822-3643 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Helena Dolphin 1 , 4 ,

- Rachel Dinh 5 ,

- Tony Foley 6 ,

- Sean Kennelly 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Irina Kinchin 1 , 2 ,

- Rónán O’Caoimh 3 , 7 ,

- Sean O’Dowd 1 , 4 , 8 ,

- Laura O’Philbin 9 ,

- Susan O’Reilly 10 ,

- Dominic Trepel 1 , 2 &

- Suzanne Timmons 1 , 3 , 11

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 705 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

A new class of antibody-based drug therapy with the potential for disease modification is now available for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the complexity of drug eligibility, administration, cost, and safety of such disease modifying therapies (DMTs) necessitates adopting new treatment and care pathways. A working group was convened in Ireland to consider the implications of, and health system readiness for, DMTs for AD, and to describe a service model for the detection, diagnosis, and management of early AD in the Irish context, providing a template for similar small-medium sized healthcare systems.

A series of facilitated workshops with a multidisciplinary working group, including Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) members, were undertaken. This informed a series of recommendations for the implementation of new DMTs using an evidence-based conceptual framework for health system readiness based on [1] material resources and structures and [2] human and institutional relationships, values, and norms.

We describe a hub-and-spoke model, which utilises the existing dementia care ecosystem as outlined in Ireland’s Model of Care for Dementia, with Regional Specialist Memory Services (RSMS) acting as central hubs and Memory Assessment and Support Services (MASS) functioning as spokes for less central areas. We provide criteria for DMT referral, eligibility, administration, and ongoing monitoring.

Conclusions

Healthcare systems worldwide are acknowledging the need for advanced clinical pathways for AD, driven by better diagnostics and the emergence of DMTs. Despite facing significant challenges in integrating DMTs into existing care models, the potential for overcoming challenges exists through increased funding, resources, and the development of a structured national treatment network, as proposed in Ireland’s Model of Care for Dementia. This approach offers a replicable blueprint for other healthcare systems with similar scale and complexity.

Peer Review reports

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent type of dementia, constitutes approximately 70% of all dementia cases globally among people aged 60 and above. Projections suggest that the current 35–40 million individuals affected by AD worldwide will rise to at least 100 million by 2050, with substantial implications for individuals, their families, and healthcare expenditure [ 1 ]. Age stands out as the primary risk factor for AD, indicating a heightened vulnerability due to the aging population, and representing a significant gap in medical care [ 2 ].

Until 2021, there was no licenced treatment to delay or slow the progression of the neurodegeneration that characterises AD [ 3 ]. However, over the past decade, evidence supporting the potential for dementia prevention through risk reduction has increased [ 4 ], alongside a growing pipeline of medications with the potential for disease modification [ 5 ], targeting the very earliest stages of AD, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and the early-stage dementia. Of the current ongoing trials of 126 agents for AD worldwide, about 80% are classified as ‘disease modifying therapties’ (DMTs), as opposed to symptomatic therapies for cognitive enhancement or management of neuropsychiatric symptoms [ 5 ]. Current potential DMTs for AD include human monoclonal antibody-based agents targeting beta amyloid.

Recently, regulatory approval was obtained in both the United States of America (USA) and Japan for two anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies showing potential DMT properties: aducanumab and lecanemab. Aducanumab underwent review by the European Medicines Agency, but did not secure approval for use in Europe. Conversely, lecanemab is currently undergoing regulatory review in Europe. Additionally, recent data have revealed promising results for another DMT candidate, donanemab, which is progressing towards approval. Notably, all anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody DMTs currently approved or on the approval pathway require biomarker confirmation of the diagnosis of AD through demonstrating ‘β-amyloid positivity’, using either PET-ligand neuroimaging, or amyloid-tau ratio cut offs from cerebrospinal fluid, obtained via lumbar puncture [ 3 ]. Plasma-derived levels of tau/β-amyloid are not yet approved for clinical use. The early evidence of these monoclonal antibody treatments is associated with potentially high-risk side effects such as brain oedema or microhaemorrhages (i.e., amyloid-associated imaging abnormalities; ARIA) which require serial monitoring with brain MRIs and close clinical follow-up during treatment [ 6 ]. This represents a departure in the current approach to AD, warranting the urgent need to ascertain care pathways for these new drugs. Although these medications have yet to receive licencing approval outside of the USA and Japan, a policy analysis on how such DMTs could be incorporated into existing services is also needed.

Ireland as a case study

In Ireland, a MCI prevalence estimate of 6% of adults over age 60 years is accepted [ 3 ], suggesting that about 57,000 of people in this age group may have MCI, although the MCI may not always be due to an underlying neurodegenerative disorder. Nonetheless, this number, together with those with early-stage AD dementia, represents a significant number of people who may benefit from approaches to prevent or delay the onset of dementia. Considering the specific inclusion criteria for the current DMTs, it is estimated that up to 20,000 people might qualify. However, when patients present to memory clinics with subjective memory complaints (SMC), or MCI, they are often discharged back to primary care without further support or intervention. Thus, it is imperative to consider systematic approaches to managing early-stage cognitive decline, since evidence suggests early interventions are associated with larger clinical benefits [ 7 ], and foster potential for access to DMT. Details of how the estimates for potentially eligible patients in Ireland were arrived at are outlined in Supplementary Material.

Memory clinics, initially established as tertiary referral medication-management clinics, were introduced to the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom in the 1990’s, when cognitive-enhancing medications for AD were first licensed. However, memory clinics are now specialist centres that diagnose and treat memory disorders, including dementia. Until recently, Ireland had only 25 such memory clinics, across 13 counties, but many operated less than weekly and were cohorted medical clinics, without a full range of disciplines. Currently, however, driven by Ireland Health Service Executive’s National Dementia Office (NDO), there are plans to expand diagnostic capability significantly over the next five years. This will add new services, as outlined in the recently launched national ‘Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland’ [ 8 ].

This new Irish model of diagnosis and care for AD, and other forms of dementia, was informed by the European research project “ACT on Dementia” [ 9 ]. The model describes a three-tiered national service, increasing the number of existing local Memory Assessment and Support Services (MASS;level 2), which are supported by primary-care led diagnostic services for low complexity cases (level 1), and by new Regional Specialist Memory Clinics (RSMC; level 3) for higher complexity cases. The RSMC focusses on complex diagnoses, while the MASS provides a full range of services, including brain health and post-diagnostic management and support. Under this new model, neurology, psychiatry of later life and older person’s medicine (medical gerontology) provide integrated services for diagnosis and post-diagnostic care.

The Model of Care for Dementia [ 8 ] includes one MASS per local population of 150,000 people (i.e., three Community Health Networks), and a minimum of five RSMCs nationally, with at least two of these based outside Dublin. The first phase of this expansion has taken place, with ten new MASS clinics and two new RSMCs, across the country, funded in 2021 and 2022. Prior to this, existing memory clinics had limited capacity to diagnose, administer and monitor complex new therapies such as DMTs, particularly regarding the anticipated increased need for biomarker ascertainment and safety monitoring including radiological surveillance. Thus, careful consideration regarding the requirement to deliver a new DMT service are outlined below, addressing minimal service requirements.

Local service audit of the prevalence of patient anti-amyloid treatment eligibility

Since the prevalence estimates of potential DMT recipients are based on numerous assumptions, we present audit data, including CSF biomarker data collected from 184 patients between 2017 and 2023, from a local MASS in Tallaght University Hospital, Ireland. Of these patients, 39.6% (73/184) were positive for AD biomarkers (low AB-42 and high P-Tau), 25% (46/184) were negative (both AB-42 and P-Tau in normal range), and 35.3% (65/184) were indeterminate (i.e., one of low AB-42 or high P-Tau) [ 10 ]. Retrospective case note review was available for 70 CSF-positive patients with AD. Of these, 40 (57%) met potential eligibility criteria for aducanumab therapy by ‘Appropriate Use Criteria’ guidelines [ 11 ]. Thus, we can conclude that over half the patients with positive AD biomarkers presenting with prodromal to early-stage AD to a MASS, may be suitable for DMTs based on current treatment indications [ 12 ]. We note that patients receiving anti-coagulation therapy generally do not undergo lumbar punctures and thus would not be offered anti-amyloid DMTs.

In 2022, the NDO in Ireland convened an Expert Reference Group (ERG) on preparedness for the imminent licensing of new DMTs for AD. Here, we report on the findings of the group’s workshop-style discussions in the form of a blueprint for the implementation of DMTs for prodromal (i.e., MCI) and early-stage dementia due to AD in Ireland. This blueprint extends existing and more detailed guidance on the infrastructure required for the administration of DMTs for AD [ 11 , 13 ] Footnote 1

Approach and framework

Facilitated workshops were convened by Ireland’s NDO, following a qualitative research model. The workshops were attended by an 11-member multidisciplinary ERG. The aim of the workshops was to scope the current capability and capacity of MASS/RSMC in Ireland, to project demand for DMTs based on Ireland’s population and the current prevalence of AD, and to define system readiness for the introduction of the DMTs. Additionally, potential challenges to developing such a service were identified. The discussions were informed by a new conceptual framework of health system readiness described by Palagyi et al., 2019 [ 14 ]. Originally devised to assess system preparedness for emerging infectious diseases, the framework, consisting of six core constructs, also has utility for the proposed DMT service. Four of the constructs focus on material resources and structures (i.e., system ‘hardware’), including (i) Surveillance, (ii) Infrastructure and medical supplies, (iii) Workforce, and (iv) Communication mechanisms; and two constructs focus on human and institutional relationships, values and norms (i.e. system ‘software’), including (i) Governance, and (ii) Trust.

The ERG consisted of geographically dispersed individuals experienced in various facets of AD care in Ireland, including an academic geriatric psychiatrist, a specialist trainee geriatrician, two consultant geriatricians who are memory clinic leads, a consultant cognitive neurologist, a GP with special interest in cognitive health, two health economists, a memory clinic specialist nurse practitioner, and a representative from the HSE and third sector partner, the Alzheimer Society of Ireland, representing people with lived experience of AD and their care partners. Five workshops were held serially, either face-to-face or remotely and were facilitated by a chairperson.

Data collection and analysis

Workshops were recorded and field notes obtained for subsequent narrative and descriptive analysis. Modelling of projected demand for DMTs was informed by current national and international prevalence data of prodromal (MCI) and early-stage dementia due to AD, AD biomarker positivity, and other factors relevant for DMT eligibility.

Purpose of an early diagnosis and DMT intervention service for AD

The ERG agreed that a new DMT service for AD should be fully embedded in existing or proposed RSMC units. As such, it would be an additional layer of service integrated into the pathway for diagnosis, initial care planning, and post-diagnostic interventions. Patients would retain close ties with their local MASS to access brain health support, and the full range of post-diagnostic interventions, in parallel with the provision of DMTs. Table 1 outlines the specific purposes of the DMT service.

Material resources and structures (‘system hardware’)

Surveillance to detect early disease.

Early detection and monitoring of progression of cognitive decline in the earliest stages (prodromal AD or early-stage dementia due to AD) should be a key element of DMT preparedness, supported by evidence of the potential effectiveness of disease modifying approaches prior to moderate- or advanced-stage dementia. This requires early detection at the clinical level, but also greater public awareness and health literacy for timely help seeking.

Early clinical detection

Ideally, blood-based biomarkers, available in primary care, would be available to enable early detection. Since such biomarkers are as yet not widely available in clinical settings, raising awareness amongst the public and primary care providers needs to take place to foster early clinical detection. Importantly, initiatives to introduce widespread cognitive screening for older people in the UK were not supported [ 15 ] due to the risk of over-diagnosis and the lack of meaningful interventions in the early stages of AD. With the advent of DMTs, such screening initiatives may need to be revisited.

Public awareness and health literacy needs

To enable successful implementation of the new DMTs, it is important to harness political willpower by presenting DMTs as a public health investment, rather than a cost, with a clear narrative around economic savings that could accrue from delaying conversion to or progression of dementia. Economic data specific to Ireland is currently not available. However, a model developed in the USA to assess the impact of DMTs on AD highlights substantial benefits [ 16 ]. It predicts that a 5-year delay in the onset of AD, leading to a 25% reduction in its prevalence by 2050, could result in cumulative savings of over $3 trillion between 2022 and 2050 [ 16 ].

Research at a national scale that captures public perception, expectations, and concerns about DMTs is also required, and any public health literacy campaign should be designed in collaboration with stakeholders, including PPI contributors, capitalising on existing resources (e.g., Ireland’s ‘Understand Together’ dementia campaign). Finally, public health messaging should highlight the importance of an early diagnosis, while managing expectations regarding the efficacy and narrow eligibility criteria for DMTs.

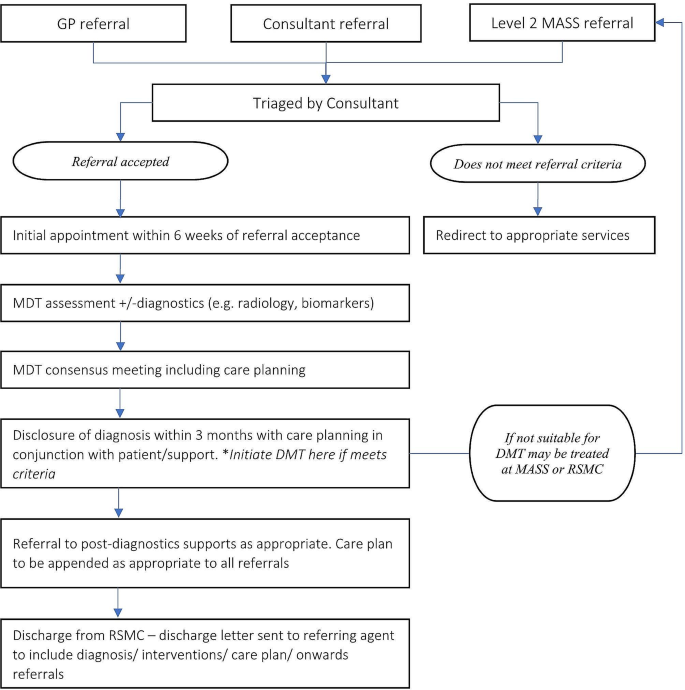

Infrastructure and provision for an early diagnosis and intervention service for AD

The EGR debated the utility of a distributed versus centralised service model for DMT delivery. One commonly used model in Irish healthcare is a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model (e.g., in hyper-acute stroke care), which can provide a practical compromise, as shown in Fig. 1 . This entails one or more RSMC acting as a central hub, ideally in different regions of the country, and local MASS acting as spokes across the country. Rolling out DMT provision in one or two highly resourced pilot sites in the first instance, rather than starting with a fully distributed service, would ascertain eligibility rates and DMTs uptake, and develop experience around the administration and monitoring of DMTs. In the meantime, existing MASS services (spokes) will see relatively small numbers of people potentially eligible for DMTs. Thus, local referral pathways will be needed from these services to a nearby RSMC, or a MASS that has elected to provide DMTs in the first wave, so that the person can have detailed eligibility assessment and access to a DMT.

Schematic of infrastructure and provision for an early diagnosis and intervention service for Alzheimer’s’ Disease (AD) in Ireland

Minimal service capacity to deliver DMT

The minimal service capacity requirements to deliver DMTs are detailed in Table 1 and include: [ 1 ] capacity to ascertain biomarker status for AD; [ 2 ] medication administration infrastructure (e.g., infusion facilities); [ 3 ] sufficient MRI neuroimaging capacity for both diagnosis and monitoring; and [ 4 ] links to brain health pathways and post-diagnostic support.

Patient referral criteria to the DMT service

It was agreed that the service providing access to anti-amyloid DMTs would identify its own pool of eligible patients within its MASS/RSMC remit, as well as accepting referrals from other MASS, diverting a patient directly to the MASS/RSMC or performing an initial assessment/full diagnosis and disclosure prior to referral. Suggested patient referral criteria to the DMT service are listed in Table 1 . Patients would not be accepted into the service if they had non-degenerative cognitive impairment due to another identified cause at the point of referral (e.g., depression, alcohol, or drug misuse, Vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, and others). If cognitive complaints persisted after effective treatment of a primary illness, then referral could be considered.

Components of the DMT intervention pathway

The DMT arm of a memory service would have three main components: [ 1 ] assessment and diagnosis; [ 2 ] intervention administration; and [ 3 ] ongoing monitoring and care . These components would run parallel to a brain health clinic model offered by local MASS services and are also outlined in Table 1 , along with a list of eligibility criteria for DMT, which align broadly with the inclusion criteria of the relevant clinical trials of these same DMT [ 3 ]. It is noted that at the point of referral to local MASS, it is expected that a basic medical and cognitive work-up will have been completed in primary care to rule out reversible causes for cognitive complaints (e.g., alcohol, or drug misuse, vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, and others) and to establish that the patient is in the prodromal or mild dementia stage. Once a referral has been accepted, a detailed assessment including biomarkers would be undertaken, as summarized in Table 1 under the first component of the service, ‘ Assessment domains . This will ascertain diagnostic sub-type and prognosis of early-stage cognitive decline. The assessment would include clinical, lifestyle, behavioural, functional, and cognitive assessments as well as biomarker detection. Key biomarkers, as recommended under the International Working Group (IWG-2) criteria for AD [ 6 ] are briefly outlined in Table 1 . Specifically, these criteria define the clinical phenotypes of AD (typical or atypical), integrating pathophysiological biomarker consistent with the presence of AD into the diagnostic process [ 17 ]. The use of biomarkers in the diagnosis of AD in the prodromal stage has altered the characterization of AD from being a syndrome-based diagnosis to a biologically-based diagnosis. A biomarker-based approach will support more personalized therapeutic approaches to the prevention of aging-related brain disorders, taking individual biological, genetic and cognitive profiles into account [ 18 ].

The outcome of the assessment will enable patients to be assigned to one of three risk-based ‘streams’: [ 1 ] begin the DMT care pathway; [ 2 ] be refered to local MASS for brain health pathway or relevant care for non-AD neurodegenerative disorders; and/or [ 3 ] be referred for a research study. Details of an approach to brain health management along with the new DMTs has been outlined elsewhere [ 13 ]. Under the ‘ intervention administration ’ domain, guidelines for rationalization of prescribed medications, managing comorbidity, and pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions are outlined, and under the ‘ ongoing monitoring and care ’ domain, guidelines for periodic MRI monitoring and possible cessation of therapy are listed. Coordination of care is an important, yet challenging, issue. Ideally, an ‘early diagnosis navigator’ is needed to ensure all patients receive optimal care and foster a pathway back to the main clinic should they be diverted down an alternative path, such as research, brain health, or DMT.

Workforce: roles and education

Roles and expertise required.

The availability of frontline healthcare workers in sufficient numbers and with appropriate training and expertise to administer and monitor DMTs is a key feature. Whilst the specialist assessments and initial interventions will be undertaken by members of the core MASS/RSMC team, they will link in with a range of services and providers, both internal and external, as per the Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland. The MASS/RSMC team should meet regularly in person or virtually for multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings. Finally,, there are additional MDT roles specifically for DMT provision, which exceed the role of the MDT as outlined in the Model of Care for Dementia (see Table 2 ).

Education and training of workforce

Delivery of an accurate diagnosis, identification of suitable treatment candidates, and monitoring of ongoing DMTs will require a standardised training program. Clinicians from multiple specialities (older person’s medicine, psychiatry of later life, neurology, general practice) involved in the work-up and diagnosis of dementia will require training delivered via the Royal College of Physicians Ireland, Irish College of General Practitioners, and the Irish College of Psychiatry. This would involve the application of AD biomarkers and therapeutic indications for prescribing DMTs. Radiologists will require training in the interpretation of evolving imaging modalities supporting the diagnosis of AD and other dementia subtypes. Training for clinicians on the identification of adverse drug reactions (e.g., ARIA) will be required and delivered as an ongoing iterative process as the field advances.

Communication mechanisms

Considering the hub-and-spoke model across the geography of Ireland, robust, timely, and standardized communication between the hub and spokes is necessary for ensuring patient safety. Additionally, the use of visual representations of the health system structure, such as the one detailed in Fig. 1 , will facilitate decision-making and preparedness among users and policy makers.

Human and institutional relationships, values, and norms (i.e., system ‘software’)

Governance: need for a national ad dmt patient registry.

Governance emphasizes the creation and monitoring of the rules that govern the supply and demand of health services. There should be a national AD DMT patient registry for accurate patient safety monitoring at a national level, and to support service planning. These data can be recorded along with other mandatory data from the developing MASS and RSMC (as an adjunct to the already proposed minimum dataset), but there may be additional monitoring requirements, dictated by Ireland Health Products Regulatory Agency (HPRA). It should be noted, however, that establishing a patient treatment registry is complex and requires significant resources, both human and financial. Challenges to consider in setting up a registry include ensuring the quality of the data, sustainability, governance, financing, and data protection. It is very likely that the pharmaceutical industry will play an important part in the set up and support of a registry, possibly linked to their licensing agreement [ 19 ].

Trust is a fundamental component of health system preparedness, incorporating both interpersonal trust (between patient and provider) and institutional trust (between individuals and the health system or government) [ 20 ]. Furthermore, trust is a prerequisite for health system resilience, particularly as new paradigms of care are being introduced. Health systems that have the trust of the population and political leaders by providing quality services prior to a health urgency have greater resilience [ 21 ].

Current provision of services in Ireland that are ‘DMT ready’ and the projected need

If and when a DMT such as lecanemab gains approval for use Ireland, the additional demand on services would be significant, including additional diagnostic services for biomarker detection (i.e., lumbar puncture, ligand-based PET scans), drug administration (i.e., infusion facilities such as day hospitals), and treatment-related safety monitoring capacity (i.e. serial brain MRIs). Considering these minimum requirements to offer an infusion-based DMT in Ireland, it is likely that it could only be offered by a limited number of centres in Ireland.

Projected neuroimaging requirements

Currently, an MRI scan is the preferred imaging modality in a memory service to assist with early diagnosis and detection of subcortical vascular changes [ 12 ]. Since the amyloid-based DMTs are associated with ARIA, ongoing monitoring for those on treatment would be needed. Based on the estimated prevalence figures above, and an anticipated need for at least three routine monitoring scans per person, this would necessitate 10,140 − 65,640 scheduled MRIs. Footnote 2 Additionally, about 40% of patients on DMTs may require up to three additional MRIs due to the actual development of ARIA or neurological sequelae, equating to 4056-26,656 non-routine MRI scans, so that the total early requirement for additional MRI scans would be 14,196 − 92,296 scans, required over the first two to three years post-licencing. 3 Steady-state MRI demand by 2030 is estimated to be 5,720 − 30,879 scans per annum.

Challenges to delivery of DMT for Alzheimer’s in Ireland

Table 3 summaries several areas that may pose both structural and ethical challenges to these new treatments for AD in Ireland.

Using a conceptual model of health system preparedness, we have presented a proposal for the delivery of anti-amyloid DMTs for AD, integrated within a hub-and-spoke model as part of the newly launched Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland. We acknowledge that the implementation of any healthcare model requires both system ‘hardware’ (tangible components such as infrastructure and workforce) and system ‘software’ (intangible components such as human values and power dynamics) [ 22 ]. As such, our current systems would likely face challenges in implementing DMT services without active efforts towards building individual and institutional trust and obtaining additional resources. Therefore, we anticipate that the full evolution to a national network of MASS with supporting RSMC, will take approximately three to five years to achieve and is subject to funding.

Moreover, while DMTs for AD offer the potential to revolutionize the management of the disease, it’s crucial to approach their development and implementation with careful consideration of both their benefits and limitations. Potential benefits include slowing of disease progression, improved quality of life, and delayed institutionalisation, along with associated economic benefits. However, these potential benefits need to be weighed against limitations such as moderate effectiveness of the drugs, potentially serious side effects, and ethical considerations such as treatment accessibility and affordability, and ascertaining what is meaningful to patients and their families [ 23 ].

Actions for the future

It will be important for healthcare systems to remain abreast of developments in order to offer those affected by AD the latest and most effective therapies. Part of this effort involves playing a role in drug discovery and evaluation. Recently, the Irish Health Research Board’s Clinical Trials Network funded a 5-year dementia clinical trials’ infrastructure development program, Dementia Trials Ireland, to grow Ireland’s capacity to conduct dementia trials [ 24 ]. In addition, over the past five years, there has been an additional focus on risk factor modification through lifestyle changes for prevention of dementia [ 4 ]. This approach is critical, and Ireland needs to keep pace with the rest of the world in addressing this issue. Finally, it is important to highlight inherent structural risks to the implementation of the proposed model. The future delivery of DMTs is complicated by long-standing capacity constraints within the Irish healthcare system, insufficient universal primary care coverage, and growing waiting lists [ 25 ]. As structural and policy reform continues as manifested by the publishing of National Dementia Strategy (2014) the establishment of the NDO (2017), and the launch of the Model of Care for Dementia (2023), this must be underpinned by targeted spending.

Limitations

The analysis was based on a consensus exercise including mostly healthcare professionals supported by consultation with healthcare recipients. Ideally, people with lived experience of AD and their care partners should be included in the main consensus process. Additionally, our data on the numbers of potential DMT recipients are broad estimates. To date, we lack robust epidemiological data on biomarker-positive individuals who may be eligible for the drugs. Additionally, the system readiness model we used is limited by the lack of consideration of funding, which is critical to future developments and implementation of DMTs. Moreover, risk-prediction modelling is not considered in the model, and although it is an active area of research, it has not been clinically implemented on a wide scale.

Other limitations include the dynamic nature of healthcare policies and the need to continuously adapt the system to consider changes in healthcare polices, funding structures and regulatory frameworks. Changes in population demographics also need to be considered, along with technological and IT infrastructure demands. Finally, other models besides the hub-and-spoke model may have merit and could provide alternative approaches to addressing this impending change in dementia care.

Healthcare systems around the world are recognising the urgent need for next-generation clinical care pathways for AD, prompted by enhanced diagnostics and the emergence of DMTs. Concerns about the ability of existing delivery models to introduce such therapies efficiently and equitably have been highlighted in several European countries [ 26 ]. Echoing European colleagues, Ireland’s healthcare system faces challenges to fully incorporate the prescription of DMTs into routine clinical pathways. However, these challenges may be overcome with additional resources, financial investment, and evolution to a structured, national treatment network, as envisaged by the recently launched ‘Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland’ [ 8 ]. We suggest that the blueprint outlined in this paper, developed in conjunction with facilitated workshops, including PPI representatives, is replicable for other healthcare systems of comparable size and scope in Europe and further afield.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

At the time of writing, whilst Biogen was granted an accelerated approval for their monoclonal antibody (aducanumab) by the US food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA) rejected the marketing authorisation application based on results from the two-phase III clinical trials.

As detailed earlier, we anticipate 3,380 to 21,880 people with prevalent AD-MCI or mild AD may proceed to DMT after licencing. As at least 3 monitoring scans are required per person, this equates to 10,140 − 65,640 additional “routine” MRIs.

In addition, 40% of these are expected to develop ARIAs (from trial data), where up to 3 additional MRIs would be required (depending on speed of resolution), equating to 4,056 − 26,656 non-routine MRI scans required over a specified period.

Once the existing pool of “prevalent” people is treated, steady-state MRI demand will be due to incident AD-MCI and mild AD. Based on the projections for an increased population with these two conditions, and also increased uptake of DMTs within this eligible pool, we estimate 1,362 to 7,350 people proceeding to DMT (see workings in footnote 2). This equates to 4,086 − 22,050 routine MRIs (3 per person), and 1634-8,820 non-routine MRIs for ARIAs (40% occurrence of ARIAs, and 3 scans per person for ARIA monitoring). Thus, the total annual MRI requirement by 2030 is 5720-30,879.

2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021;17(3):327–406.

Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Reviews Neurol. 2011;7(3):137–52.

Article Google Scholar

Cummings J, Lee G, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Taghva K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2021. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Translational Res Clin Interventions. 2021;7(1):e12179.

Google Scholar

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cummings J, Zhou Y, Lee G, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Cheng F. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2023. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Translational Res Clin Interventions. 2023;9(2):e12385.

Frölich L, Jessen F, Lecanemab. Appropriate Use recommendations — a Commentary from a European perspective. J Prev Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023;10(3):357–8.

16th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD). Boston, MA (USA) October 24–27, 2023: Symposia. J Prev Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023;10(1):4–55.

Model of Care for. Dementia in Ireland [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 10].

Krolak-Salmon P, Maillet A, Vanacore N, Selbaek G, Rejdak K, Traykov L, et al. Toward a sequential strategy for diagnosing Neurocognitive disorders: a Consensus from the Act on Dementia European Joint Action. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72:363–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dolphin H, Fallon A, McHale C, Dookhy J, O’Neill D, Coughlan T, IN SUPPORTING ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE DIAGNOSIS: CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES FROM AN IRISH REGIONAL SPECIALIST MEMORY SERVICE. 89 CSF BIOMARKER UTILITY. Age Ageing. 2021;50(Supplement3):ii9–41.

Cummings J, Apostolova L, Rabinovici GD, Atri A, Aisen P, Greenberg S, et al. Lecanemab: appropriate use recommendations. J Prev Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023;10(3):362–77.

CAS Google Scholar

Togher Z, Dolphin H, Russell C, Ryan M, Kennelly SP, O’Dowd S. Potential eligibility for Aducanumab therapy in an Irish specialist cognitive service—utilising cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and appropriate use criteria. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(8).

Leroi IPC, Davenport R, et al. Blueprint for a Brain Health Clinic to Detect and Manage Early-Stage Cognitive decline: a Consensus Exercise. J Neurodegener Disord. 2020;3(1):54–64.

Palagyi A, Marais BJ, Abimbola S, Topp SM, McBryde ES, Negin J. Health system preparedness for emerging infectious diseases: a synthesis of the literature. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(12):1847–68.

Chambers LW, Sivananthan S, Brayne C. Is dementia screening of apparently healthy individuals justified? Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2017;2017:9708413.

Tahami Monfared AA, Tafazzoli A, Ye W, Chavan A, Deger KA, Zhang Q. A Simulation Model to evaluate the potential impact of Disease-modifying treatments on Burden of Illness in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol Therapy. 2022;11(4):1609–23.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–29.

Gauthier S, Zhang H, Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Rosa-Neto P. Impact of the biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease using amyloid, tau and neurodegeneration (ATN): what about the role of vascular changes, inflammation, Lewy body pathology? Translational Neurodegeneration. 2018;7(1):12.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gliklich RELM, Dreyer NA, editors. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide [Internet]. 4th edition Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020 Sep Chap. 2, Planning a Registry https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK208616/

Topp SM, Chipukuma JM. A qualitative study of the role of workplace and interpersonal trust in shaping service quality and responsiveness in Zambian primary health centres. Health Policy Plann. 2015;31(2):192–204.

Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1910–2.

Sheikh K, Gilson L, Agyepong IA, Hanson K, Ssengooba F, Bennett S. Building the field of Health Policy and Systems Research: framing the questions. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8):e1001073.

Assunção SS, Sperling RA, Ritchie C, Kerwin DR, Aisen PS, Lansdall C, et al. Meaningful benefits: a framework to assess disease-modifying therapies in preclinical and early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):54.

About Dementia Trials Ireland [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 10]. https://dementiatrials.ie/about-dementia-trials-ireland/ .

Turner B. Putting Ireland’s health spending into perspective. Lancet. 2018;391(10123):833–4.

Hlavka JP, Mattke S, Liu JL. Assessing the Preparedness of the Health Care System Infrastructure in Six European Countries for an Alzheimer’s Treatment. Rand Health Q 2019 May 16. 2019;8(3).

Carney P, O’ Shea E, Pierse T. Estimates of the prevalence, incidence and severity of dementia in Ireland. Ir J Psychol Med. 2019;36(2):129–37.

Angioni D, Hansson O, Bateman RJ, Rabe C, Toloue M, Braunstein JB, et al. Can we use blood biomarkers as Entry Criteria and for Monitoring Drug Treatment effects in clinical trials? A report from the EU/US CTAD Task Force. J Prev Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023;10(3):418–25.

Sperling R, Salloway S, Brooks DJ, Tampieri D, Barakos J, Fox NC, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease treated with bapineuzumab: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(3):241–9.

Maharani A, Pendleton N, Leroi I, Hearing Impairment. Loneliness, social isolation, and cognitive function: longitudinal analysis using English Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019;27(12):1348–56.

Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR). Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–a.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sikkes SAM, de Lange-de Klerk ESM, Pijnenburg YAL, Gillissen F, Romkes R, Knol DL, et al. A new informant-based questionnaire for instrumental activities of daily living in dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012;8(6):536–43.

Ismail Z, Agüera-Ortiz L, Brodaty H, Cieslak A, Cummings J, Fischer CE, et al. The Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C): A Rating Scale for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Pre-Dementia Populations. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;56:929 − 38.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. London; 2018.

Goldman JS, Hahn SE, Catania JW, Larusse-Eckert S, Butson MB, Rumbaugh M, et al. Genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer disease: joint practice guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Genet Sci. 2011;13(6):597–605.

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Öhrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673–84.

Gates NJ, Rutjes AWS, Di Nisio M, Karim S, Chong LY, March E et al. Computerised cognitive training for 12 or more weeks for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in late life. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2020(2).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the Working Group for Disease Modifying Treatments for Dementia convened by the Irish Health Service Executive’s National Dementia Office, who contributed to discussions that informed this paper, including the authors, and Professor Brian Lawlor, Dr Justin Kinsella, Mr Pat McLoughlin, Ms Anne Horgan, and Dr Tim Dukelow, and members of the Patient and Public Involvement panel of Alzheimer Society Ireland.

This work was unfunded but supported administratively by the HSE’s National Dementia Office, Ireland.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Global Brain Health Institute, School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Lloyd Building, Dublin 2, Dublin, Ireland

Iracema Leroi, Helena Dolphin, Sean Kennelly, Irina Kinchin, Sean O’Dowd, Dominic Trepel & Suzanne Timmons

Global Brain Health Institute, Dublin, Ireland

Iracema Leroi, Sean Kennelly, Irina Kinchin & Dominic Trepel

HRB-CTN Dementia Trials Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

Iracema Leroi, Sean Kennelly, Rónán O’Caoimh & Suzanne Timmons

Institute of Memory and Cognition, Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Helena Dolphin, Sean Kennelly & Sean O’Dowd

Centre for Global Health, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Rachel Dinh

Department of General Practice, School of Medicine, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Department of Geriatric Medicine, Mercy University Hospital, Cork, Ireland

Rónán O’Caoimh

Health Service Executive’s National Dementia Office, Dublin, Ireland

Sean O’Dowd

Alzheimer Society Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

Laura O’Philbin

Health Services Executive, Dublin, Ireland

Susan O’Reilly

Centre for Gerontology and Rehabilitation, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Suzanne Timmons

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors meet all four ICMJE criteria for authorship. IL conceived and planned the project, supported by the NDO and other members of the working group. All authors carried participated in the workshops and contributed to the consensus statements, interpretation and presentation of the results. IL, HD, and RD took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. None of the other authors declare any conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Iracema Leroi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Given that this study relied solely on the analysis of publicly available and previously published data, including Dolphin, Fallon [ 10 ], ethical approval was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

IL, SK, and SOD participated in Advisory Groups with Biogen and Roche. The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained. None of the other authors declare any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Leroi, I., Dolphin, H., Dinh, R. et al. Navigating the future of Alzheimer’s care in Ireland - a service model for disease-modifying therapies in small and medium-sized healthcare systems. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 705 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11019-7

Download citation

Received : 02 October 2023

Accepted : 19 April 2024

Published : 05 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11019-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Disease modifying therapies

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Service readiness

- Memory assessment service

- Anti-amyloid drugs

- Brain health clinic

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Active Implementation Formula Framework Overviews (Modules)

Author(s): SISEP Team; NIRN Team

Publication Date: March 2023

Resource Type : Read

Here is a comprehensive list of the AI Hub Modules PDF versions. The content remains the same, and the resources and hyperlinks are improved!

- Active Implementation Overview (Module 1)

- Implementation Drivers Overview (Module 2)

- Implementation Teams Overview (Module 3)

- Implementation Stages Overview (Module 4)

- Improvement Cycles Overview (Module 5)

- Usable Innovations Overview (Module 6)

Search form

Publications & resources, a practice guide to supporting implementation.

For more resources related to competencies for implementation support practice, visit our Implementation Practice page .

How the freshly selected regional centres will bolster the implementation of the Biodiversity Plan

At the fourth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI 4) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the Parties selected 18 regional organizations spanning the globe in a multilateral push to bolster the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, also known as the Biodiversity Plan , through science, technology and innovation:

- Africa: The Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC), the Ecological Monitoring Center (CSE), the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD), the Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS), and the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI).

- Americas: The Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute, the Secretariat of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), and the Central American Commission on Environment and Development (CCAD).

- Asia: ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (ACB); IUCN Asia Regional Office; IUCN Regional Office for West Asia (ROWA); Nanjing Institute of Environmental Sciences (NIES); Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia (CAREC).

- Europe: European Commission - Joint Research Centre of the European Commission (JRC); IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation; IUCN Regional Office for Eastern Europe and Central Asia (ECARO); Royal Belgian Institute for Natural Sciences (RBINS).

- Oceania: The Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP).

Here are five facts about the selection of these centres and the way they will bring the Parties to the CBD closer to halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030 :

1. Nested in existing institutions for efficiency and rapid deployment

The selected centres are hosted by existing institutions that have responded to the CBD Secretariat’s call for expression of interest. The applications received translate a global commitment to implementing the Biodiversity Plan. This global network of centres forms part of the technical and scientific cooperation mechanism under the CBD. They will contribute to filling gaps in international cooperation and catering to the needs of countries in the regions that they cover.

2. One-stop-shop for scientific, technical and technological support

The mandate of the centres is to catalyse technical and scientific cooperation among the Parties to the Convention in the geographical regions they cover. The support they offer may include the sharing of scientific knowledge, data, expertise, resources, technologies, including indigenous and traditional technologies, and technical know-how with relevance to the national implementation of the 23 targets of the Biodiversity Plan. Other forms of capacity building and development may also be provided.

3. Complementarity with existing initiatives

The expected contributions of the centres will constitute a surge of capacity, complementing small-scale initiatives for technical and scientific cooperation among its Parties through programmes such as the Bio-Bridge Initiative . The newly selected centres will expand, scale-up and accelerate efforts in support of the implementation of the Biodiversity Plan.

4. Delivering field support tailored to regional specificities

Countries around the world face well recognized challenges in aligning with universally agreed targets while considering biophysical specificities and national circumstances. The regional centres will provide regionally appropriate solutions.

5. Building on and amplifying existing cooperation

Many examples around the world demonstrate the benefits of transboundary cooperation. In South Africa, the “Black Mambas” Anti-Poaching Unit has benefited from Dutch expertise in fitting rhinoceros with subcutaneous sensors and horn transmitters to track their movements across the Greater Kruger National Park.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, non-governmental organization Corales de Paz (Colombia) shared their “Caribbean Reef Check” methodology and “Reef Repair Diver “programs with Ecuador-based CONMAR. Participants in CONMAR-organized training camps could thus benefit from expertise in coral reef monitoring and coral gardening.

The newly selected centres will seek to expand this constellation of bright spots of cooperation for nature and for people.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Request Supports from NIRN. NIRN is excited to share its service and support request page where Implementation Practice meets Implementation Research and Evaluation in perfect synergy. As pioneers in the field, we seamlessly integrate evidence-based strategies with real-world applications, providing a comprehensive platform for organizations ...

The Active Implementation Frameworks In 2005, the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) released a monograph1 synthesizing implementation research findings across a range of fields. The NIRN also conducted a series of meetings with experts to focus on implementation best practices2. Based on these findings and subsequent research and ...