- Download PDF

- CME & MOC

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Management of Food Allergies and Food-Related Anaphylaxis

- 1 Division of Allergy, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee

- 2 Thurston Arthritis Research Center, Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill

- 3 University of North Carolina Food Allergy Initiative, Division of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill

- JAMA Patient Page What Is Alpha-Gal Syndrome? Fatema Mollah, MD; Mark A. Zacharek, MD; Mariel R. Benjamin, MD JAMA

- Original Investigation Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction and Risk of Immunoglobulin E–Mediated Food Allergy Roberta Scarpone, MD, MPH; Parisut Kimkool, MD; Despo Ierodiakonou, MD, PhD; Jo Leonardi-Bee, PhD; Vanessa Garcia-Larsen, PhD; Michael R. Perkin, MD, PhD; Robert J. Boyle, MD, PhD JAMA Pediatrics

Importance An estimated 7.6% of children and 10.8% of adults have IgE-mediated food-protein allergies in the US. IgE-mediated food allergies may cause anaphylaxis and death. A delayed, IgE-mediated allergic response to the food-carbohydrate galactose-α-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) in mammalian meat affects an estimated 96 000 to 450 000 individuals in the US and is currently a leading cause of food-related anaphylaxis in adults.

Observations In the US, 9 foods account for more than 90% of IgE-mediated food allergies—crustacean shellfish, dairy, peanut, tree nuts, fin fish, egg, wheat, soy, and sesame. Peanut is the leading food-related cause of fatal and near-fatal anaphylaxis in the US, followed by tree nuts and shellfish. The fatality rate from anaphylaxis due to food in the US is estimated to be 0.04 per million per year. Alpha-gal syndrome, which is associated with tick bites, is a rising cause of IgE-mediated food anaphylaxis. The seroprevalence of sensitization to alpha-gal ranges from 20% to 31% in the southeastern US. Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for food-related anaphylaxis. The cornerstone of IgE-food allergy management is avoidance of the culprit food allergen. There are emerging immunotherapies to desensitize to one or more foods, with one current US Food and Drug Administration–approved oral immunotherapy product for treatment of peanut allergy.

Conclusions and Relevance IgE-mediated food allergies, including delayed IgE-mediated allergic responses to red meat in alpha-gal syndrome, are common in the US, and may cause anaphylaxis and rarely, death. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to food requires prompt treatment with epinephrine injection. Both food-protein allergy and alpha-gal syndrome management require avoiding allergenic foods, whereas alpha-gal syndrome also requires avoiding tick bites.

Read More About

Iglesia EGA , Kwan M , Virkud YV , Iweala OI. Management of Food Allergies and Food-Related Anaphylaxis. JAMA. 2024;331(6):510–521. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.26857

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns

Affiliations.

- 1 Allergy and Clinical Immunology Unit, San Giuseppe Moscati Hospital, 83100 Avellino, Italy.

- 2 Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry "Scuola Medica Salernitana", University of Salerno, 84081 Baronissi, Italy.

- 3 Division of Allergy and Immunology, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

- PMID: 34068047

- PMCID: PMC8152468

- DOI: 10.3390/nu13051638

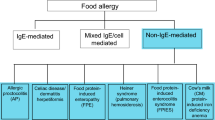

Adverse food reactions include immune-mediated food allergies and non-immune-mediated intolerances. However, this distinction and the involvement of different pathogenetic mechanisms are often confused. Furthermore, there is a discrepancy between the perceived vs. actual prevalence of immune-mediated food allergies and non-immune reactions to food that are extremely common. The risk of an inappropriate approach to their correct identification can lead to inappropriate diets with severe nutritional deficiencies. This narrative review provides an outline of the pathophysiologic and clinical features of immune and non-immune adverse reactions to food-along with general diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Special emphasis is placed on specific nutritional concerns for each of these conditions from the combined point of view of gastroenterology and immunology, in an attempt to offer a useful tool to practicing physicians in discriminating these diverging disease entities and planning their correct management. We conclude that a correct diagnostic approach and dietary control of both immune- and non-immune-mediated food-induced diseases might minimize the nutritional gaps in these patients, thus helping to improve their quality of life and reduce the economic costs of their management.

Keywords: food allergy; food intolerance; nutrition; nutritional concerns.

Publication types

- Diet Therapy / adverse effects

- Diet Therapy / methods

- Food / adverse effects

- Food Hypersensitivity / diagnosis

- Food Hypersensitivity / immunology

- Food Hypersensitivity / physiopathology*

- Food Hypersensitivity / therapy

- Food Intolerance / diagnosis

- Food Intolerance / immunology

- Food Intolerance / physiopathology*

- Food Intolerance / therapy

- Nutritional Status*

Update on Therapies and Management of Food Allergies

The primary therapeutic strategy to manage food allergy is avoidance of the culprit allergen. However, now active management options, such as food immunotherapy, offer patients alternatives.

Cecelia Damask, DO, Chair, Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Committee

For me, time spent with my family and friends over good food and conversation is the best way to feel fully engaged in the moment. Food is a huge part of living la dolce vita . But what if the food you eat could kill you, even accidentally?

The prevalence of childhood peanut allergy in the United States has been rising, with reported rates of 0.4% in 1997 and 2.2% in 2016. 1,2 During this same period, the guideline recommendations for introducing peanut-containing products to infants changed several times.

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended to avoid feeding peanut-containing products to children until 3 years of age. In 2008, the recommendations were revised because there were not significant data to recommend delaying. Despite this, many experts continued to recommend delaying introduction. In 2013, a landmark article on the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study was published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 3 The study demonstrated that early introduction of peanuts decreased the frequency of peanut allergy by 80% among children at high risk for developing it. Subsequently, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) released Addendum Guidelines in 2017 encouraging the early introduction of peanuts, especially in high-risk infants, after testing and discussion with physician. 4 The American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI), American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI), and Canadian Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology put out guidance in the form of a consensus document in 2021 5 further clarifying that screening before introduction is not required but may be preferred by some families.

The primary therapeutic strategy in the management of food allergy remains avoidance of the culprit allergen; there is currently no cure for food allergy . Prompt administration of epinephrine is recommended to treat anaphylaxis should accidental exposure occur.

Peanut allergen-dnfp, a powder, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 for children ages 4 to 17 years. It works by desensitizing patients by gradually increasing the dosage of peanut exposure. OIT does carry significant risk of allergic reactions and administration can be burdensome as it requires daily dosing (possibly indefinitely) with dosing restricted around exercise and illness. Multiple office visits (11+ visits during a six-month build-up period) are required.

OUtMATCH is a three-stage phase 3 multicenter, randomized double-anonymized placebo-controlled trial. 6 Stage 1 has been completed, which consisted of an omalizumab arm (dosed based on IgE level and patient weight) and a placebo arm over 16 to 20 weeks. The study population included participants aged one to 55 years with a peanut allergy and an allergy to at least two of six other foods. The primary outcome was the number of participants able to consume > 600 mg peanut protein without dose-limiting symptoms during the food challenge at the end of stage 1. A total of 67% of those treated with omalizumab tolerated peanut (consumption of > 600 mg peanut protein) versus 7% of those receiving placebo. Omalizumab also improved tolerance of other foods (milk, egg, cashew) versus placebo. 7

In February 2024, the FDA approved omalizumab for IgE-mediated food allergy in adults and children (age 1 year and up) for the reduction of allergic reactions (Type I), including reducing the risk of anaphylaxis, that may occur with accidental exposure to one or more foods. 7 Patients who receive omalizumab must still continue to avoid foods to which they are allergic, and they still need to have an epinephrine auto-injector.

This newly approved indication for omalizumab provides a treatment option to reduce the risk of allergic reactions in patients with IgE-mediated food allergies. It will not eliminate their food allergy, nor will it allow patients to consume their food allergen freely, but repeated use of omalizumab will help reduce the risk of reactions if accidental exposure does occur. Another potential benefit is that this may help to decrease the anxiety from living a life consumed by fear of accidental exposure to their food allergen—one more step toward living la dolce vita .

- Gupta, RS, Warren, CM, Smith, BM, Blumenstock, JA, Jiang, J, Davis, MM, and Nadeau, KC. "The public health impact of parent-reported childhood food allergies in the United States." Pediatrics 142, no. 6 (2018): e20181235.

- Gupta, RS, Warren, CM, Smith, BM, Jiang, J, Blumenstock, JA, Davis, MM, Schleimer, RP, and Nadeau, KC. "Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults." JAMA Network Open 2, no. 1 (2019): e185630-e185630.

- Du Toit, G, Roberts, G, Sayre, PH, Bahnson, HT, Radulovic, S, Santos, AF, Brough HA, et al. “Randomized Trial of Peanut Consumption in Infants at Risk for Peanut Allergy.” New England Journal of Medicine (2016) 372, no. 9 (n.d.): 803–13. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414850.

- Togias, Alkis et al. “Addendum Guidelines for the Prevention of Peanut Allergy in the United States: Summary of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–Sponsored Expert Panel” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics , 117, no. 5 (2017): 788 – 793

- Fleischer, DM, Chan, ES, Venter, C, Spergel, JM, Abrams, EM, Stukus, D, Groetch, M, et al. "A consensus approach to the primary prevention of food allergy through nutrition: guidance from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and the Canadian Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology." The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology : In Practice 9, no. 1 (2021): 22-43.

- Wood, RA, Chinthrajah, RS, Rudman-Spergel, AK, Babineau, DC, Sicherer, SH, Kim, EH, Shreffler, WG, et al. "Protocol design and synopsis: omalizumab as monotherapy and as adjunct therapy to multiallergen OIT in children and adults with food allergy (OUtMATCH)." Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology : Global 1, no. 4 (2022): 225-232.

- Wood, RA, Togias, A, Sicherer, SH, Shreffler, WG, Kim, EH, Jones, SM, Leung, DYM, et al. "Omalizumab for the Treatment of Multiple Food Allergies." New England Journal of Medicine (2024).

WATCH | The Otolaryngology Core Curriculum, A Deeper Dive

Stories from the Road: Pittsburgh to Peru

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in the Age of Neuromodulation

Optimizing Audiology and Hearing Aid Ancillaries

Perspective: Employing Allyship to Move from Good Intentions to Action

Spotlight on Hearing Health in May

All Together

2024 Above and Beyond Awards

Our Commitment to Our Mission, Vision, and Strategic Goals Travels with Us

Allergy Season Got a Jumpstart This Year

LISTEN: Updates on Chronic Cough Podcast

Pearls from Your Peers: Gene Therapy for Hearing Loss

Consumer Sleep Technologies and Wearables: Integration into Practice

A Culture of Perfectionism Is Poisoning Young Surgeons

Finding Your Happy Place in Otolaryngology

Experiences of the 2023 URM Away Rotation Grant Recipients: Part 3

For Your Patients: Stay ENT Healthy this Allergy Season!

AAO-HNSF 2023 Humanitarian Travel Grant Report: Kampala, Uganda

“A Few of My Favorite Things” for #OTOMTG24

The Treasures of the 2024 Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO℠

Submit to the #OTOMTG24 Call for Simulation Abstracts

Advertisement

Differentiating Food Allergies from Food Intolerances

- Published: 27 July 2011

- Volume 13 , pages 426–434, ( 2011 )

Cite this article

- Stefano Guandalini 1 &

- Catherine Newland 1

2545 Accesses

25 Citations

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Adverse reactions to foods are extremely common, and generally they are attributed to allergy. However, clinical manifestations of various degrees of severity related to ingestion of foods can arise as a result of a number of disorders, only some of which can be defined as allergic, implying an immune mechanism. Recent epidemiological data in North America showed that the prevalence of food allergy in children has increased. The most common food allergens in the United States include egg, milk, peanut, tree nuts, wheat, crustacean shellfish, and soy. This review examines the various forms of food intolerances (immunoglobulin E [IgE] and non–IgE mediated), including celiac disease and gluten sensitivity.

Immune mediated reactions can be either IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated. Among the first group, Immediate GI hypersensitivity and oral allergy syndrome are the best described.

Often, but not always, IgE-mediated food allergies are entities such as eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastroenteropathy.

Non IgE-mediated immune mediated food reactions include celiac disease and gluten sensitivity, two increasingly recognized disorders.

Finally, non–immune mediated reactions encompass different categories such as disorders of digestion and absorption, inborn errors of metabolism, as well as pharmacological and toxic reactions.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity

Pathophysiology and Symptoms of Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis

Food Allergies, Food Intolerances, and Carbohydrate Malabsorption

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • of importance •• of major importance.

•• Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 Suppl):S1-58. This article is a result of an expert consensus convened by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the NIH. It provides new guidelines regarding diagnosis and management of food allergies in the United States .

PubMed Google Scholar

•• Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183–91. The American Academy of Pediatrics new policy statement on dietary management for the prevention of atopic disease. The recommendations in this important update represent a somewhat revolutionary change from the previous guidelines, acknowledging the lack of evidence for the delayed introduction of some food proteins in children at risk of atopy .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(9):1217–25.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):88–93.

Branum AM, Lukacs SL. Food allergy among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1549–55.

Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Burks AW, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the US determined by a random digit dial telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(4):559–62.

Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self-reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3–20

• Lack G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1331–6. This article reviews possible risk factors and theories for the development of food allergy and proposes a provocative alternative hypothesis, suggesting that sensitization to allergen occurs through environmental exposure to allergen through the skin and that consumption of food allergen induces oral tolerance .

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2 Suppl Mini-Primer):S470–5.

Skripak JM, Matsui EC, Mudd K, Wood RA. The natural history of IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1172–7.

Savage JH, Matsui EC, Skripak JM, Wood RA. The natural history of egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1413–7.

Savage JH, Kaeding AJ, Matsui EC, Wood RA. The natural history of soy allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(3):683–6.

• Kotaniemi-Syrjanen A, Palosuo K, Jartti T, Kuitunen M, Pelkonen AS, Makela MJ. The prognosis of wheat hypersensitivity in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2 Pt 2):e421-8. The study aimed to determine the natural history of wheat hypersensitivity and to define risk factors for persistent wheat hypersensitivity. The authors showed that almost all children with wheat hypersensitivity can tolerate wheat by adolescence .

Keet CA, Matsui EC, Dhillon G, Lenehan P, Paterakis M, Wood RA. The natural history of wheat allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(5):410–5.

Byrne AM, Malka-Rais J, Burks AW, Fleischer DM. How do we know when peanut and tree nut allergy have resolved, and how do we keep it resolved? Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(9):1303–11.

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S116–25.

• Chafen JJ, Newberry SJ, Riedl MA, et al. Diagnosing and managing common food allergies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1848–56. A comprehensive and rigorous systematic review of publications regarding the diagnosis and management of food allergies from 1988 to 2009. The authors conclude that the evidence for the prevalence and management of food allergy is greatly limited by a lack of uniformity for criteria for making a diagnosis .

Sampson HA, Ho DG. Relationship between food-specific IgE concentrations and the risk of positive food challenges in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:444–51.

Sampson HA. Utility of food-specific IgE concentration in predicting symptomatic food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:891–6.

Edwards HE. Oral Desensitization in Food Allergy. Can Med Assoc J. 1940;43(3):234–6.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

•• Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):654–60. A multicenter study, the first of its kind double blind and placebo controlled, investigating the safety and effectiveness of oral immunotherapy (desensitization) for peanut allergy in 28 children. The study shows that peanut oral immunotherapy was able to induce desensitization and concurrent immune modulation .

Zapatero L, Alonso E, Fuentes V, Martinez MI. Oral desensitization in children with cow's milk allergy. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18(5):389–96.

Morisset M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Guenard L, et al. Oral desensitization in children with milk and egg allergies obtains recovery in a significant proportion of cases. A randomized study in 60 children with cow's milk allergy and 90 children with egg allergy. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39(1):12–9.

Meglio P, Bartone E, Plantamura M, Arabito E, Giampietro PG. A protocol for oral desensitization in children with IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy. Allergy. 2004;59(9):980–7.

Martorell A, De la Hoz B, Ibanez MD, et al. Oral desensitization as a useful treatment in 2-year-old children with cow's milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. Apr 11 2011.

Kim JS, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sicherer SH, Noone S, Moshier EL, Sampson HA. Dietary baked milk accelerates the resolution of cow's milk allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. May 20 2011.

• Land MH, Kim EH, Burks AW. Oral desensitization for food hypersensitivity. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31(2):367–76. This article examines the mechanisms of oral tolerance and the breakdown that leads to food allergy, as well as the history and current state of oral and sublingual immunotherapy development .

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):346–9.

Google Scholar

Host A, Halken S, Muraro A, et al. Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(1):1–4.

Fifty-Fourth World Health Assembly Provisional Agenda Item 13.1.1. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding: the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

•• Berg A, Kramer U, Link E, et al. Impact of early feeding on childhood eczema: development after nutritional intervention compared with the natural course - the GINIplus study up to the age of 6 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(4):627–36. A study in almost 6000 children aiming to compare the course of eczema in predisposed children after nutritional intervention with hydrolyzed formulas to the natural course of eczema. The results suggest that early intervention with hydrolyzed infant formulas can substantially compensate up until the age of 6 years for an enhanced risk of childhood eczema due to familial predisposition to allergy .

Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Wood RA, Sicherer SH. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome caused by solid food proteins. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):829–35.

Caubet JC, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Current understanding of the immune mechanisms of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(3):317–27.

Mehr S, Kakakios A, Frith K, Kemp AS. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: 16-year experience. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e459–64.

Katz Y, Goldberg MR, Rajuan N, Cohen A, Leshno M. The prevalence and natural course of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome to cow's milk: a large-scale, prospective population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):647–653 e641-643.

Chang JW, Wu TC, Wang KS, Huang IF, Huang B, Yu IT. Colon mucosal pathology in infants under three months of age with diarrhea disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(3):387–90.

Chehade M, Magid MS, Mofidi S, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Sicherer SH. Allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis with protein-losing enteropathy: intestinal pathology, clinical course, and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42(5):516–21.

•• Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3–20. Updated consensus recommendations for eosinophilic esophagitis. The paper includes a review of previous guidelines, summary of the literature, committee recommendations and recommendations for the future .

Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 1:S1–S35.

Verdu EF. Editorial: Can gluten contribute to irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):516–8.

Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, et al. Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med. 2011;9:23.

Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):508–514; quiz 515.

• Troncone R, Jabri B. Coeliac disease and gluten sensitivity. J Intern Med. 2011;269(6):582–590. A timely review on celiac disease and gluten sensitivity, examining the possible immunological mechanisms underlying these conditions. Emphasis is given to specific autoantibodies as markers of the celiac spectrum and to the hypothesis that innate epithelial stress can exist independently from adaptive intestinal immunity in gluten sensitivity .

Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB, Jabri B. Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:493–525.

Dickey W, Hughes DF, McMillan SA. Patients with serum IgA endomysial antibodies and intact duodenal villi: clinical characteristics and management options. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(10):1240–3.

Kurppa K, Ashorn M, Iltanen S, et al. Celiac disease without villous atrophy in children: a prospective study. J Pediatr. 2010;157(3):373–80, 380 e371.

Kurppa K, Collin P, Viljamaa M, et al. Diagnosing mild enteropathy celiac disease: a randomized, controlled clinical study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):816–23.

Tosco A, Salvati VM, Auricchio R, et al. Natural history of potential celiac disease in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(4):320–5; quiz e336.

Fleischer DM, Bock SA, Spears GC, et al. Oral food challenges in children with a diagnosis of food allergy. J Pediatr. 2011;158(4):578–83 e571.

Download references

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Section of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Celiac Disease Center, University of Chicago, 5839 S. Maryland Ave, MC 4065, Chicago, IL, 60637, USA

Stefano Guandalini & Catherine Newland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefano Guandalini .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Guandalini, S., Newland, C. Differentiating Food Allergies from Food Intolerances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 13 , 426–434 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-011-0215-7

Download citation

Published : 27 July 2011

Issue Date : October 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-011-0215-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Food allergy

- Food intolerance

- Food sensitivity

- Celiac disease

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2024

Sublingual immunotherapy for allergy to shrimp: the nine-year clinical experience of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice

- Lydia M. Theodoropoulou ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-7344-5818 1 &

- Niamh A. Cullen 2

Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology volume 20 , Article number: 33 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

153 Accesses

Metrics details

Diet restrictions and fear of adverse reactions put a significant burden on the nutrition, growth and life style of children and adults with food allergies. While various disease-modifying options are pursued, there are so far no published clinical data on immunotherapy for crustaceans. The efficacy and safety of desensitization to crustaceans by means of sublingual immunotherapy is assessed for the first time in this study with a view of validating it as a clinical-practice modality.

Charts of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice from the period January 2014–June 2023 were reviewed to identify patients with allergy to shrimp treated with sublingual immunotherapy and to retrospectively evaluate their responses to oral challenge.

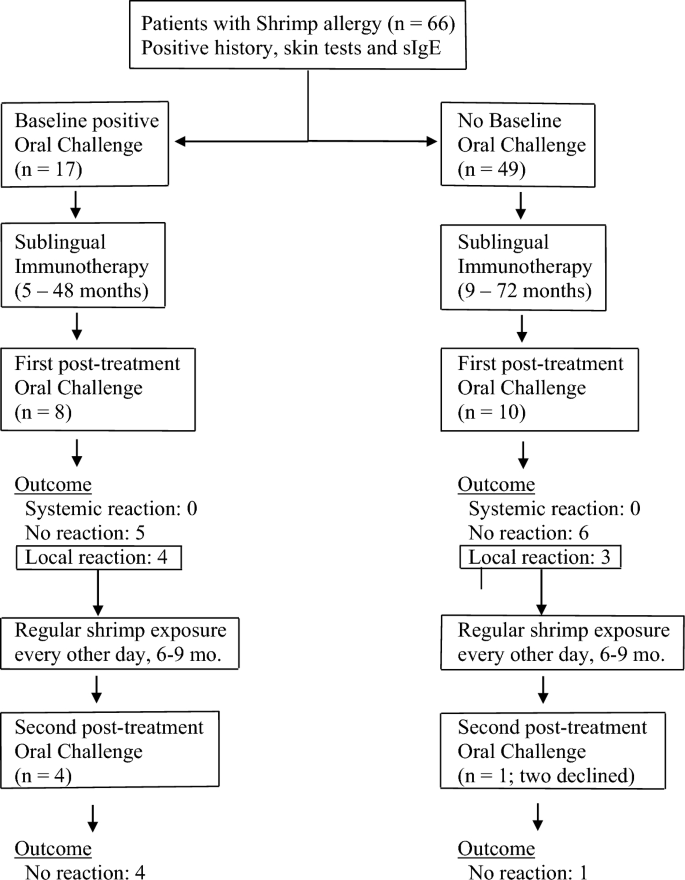

Sixty-six patients were identified who had been treated by sublingual immunotherapy for either systemic or localized reactions to shrimp. Demographics and relevant comorbidities were consistent with those of the atopic population. Sublingual immunotherapy with serially diluted mixtures was initiated at 64–320 ng/dose and was gradually escalated to 0.5 mg/dose three times a day. The sublingual immunotherapy course ranged from 5 to 72 months (average: 51 months), following which, 18 patients underwent shrimp oral challenge. No systemic reactions occurred upon challenge; no patient required epinephrine. Tolerance of target dose equal to or exceeding 42 g shrimp was achieved in 11 patients (61%), seven of whom had originally presented with systemic reactions to crustaceans. Seven patients (38%) developed one or more of the following localized reactions: oral itching, nasal symptoms, localized perioral hives, localized hives at pressure points, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain upon exposure to a cumulative dose of 39.2–148.2 g of shrimp during the 4 h of the challenge. Five of these patients had originally presented with systemic reactions to crustaceans. Five of the 7 patients who developed localized symptoms during the challenge were subsequently placed on routine exposure to 12–20 g shrimp every other day. Two patients continued sublingual immunotherapy but declined routine exposure to shrimp every other day because they had no intention to incorporate crustaceans to their routine diet. On repeat challenge 6–9 months after original challenge, all five patients who had routine exposure to 12–20 g shrimp every other day tolerated the procedure to target dose without any symptoms.

Conclusions

Desensitization to shrimp by sublingual immunotherapy appears to be safe and effective as shown in this study. Whether the immune modification induced by sublingual immunotherapy is permanent resulting in sustained tolerance, or the achieved degree of desensitization depends on regular exposure is not known; therefore, following challenge, regular consumption three-four times per week was recommended.

Introduction

IgE-mediated food allergies affect 4–10% of children and 2–3% of adults [ 1 ]. After early childhood, permanent IgE-mediated food allergies are unlikely to spontaneously resolve, and their systemic manifestations upon exposure may lead to life-threatening events. Food allergies of systemic nature become a cause of anxiety for patients and their family affecting all aspects of life that pertain to food consumption [ 2 ]. Regarding shellfish, and shrimp in particular, anxiety is further heightened by the common catering practice to include shrimps as hors d’oeuvres and appetizers in social events where food is served, thus increasing the risk for contamination of all other foods offered.

There is no treatment that would eradicate a permanent allergy, and guidelines focus on prevention and management of accidental exposures with epinephrine, antihistamines, steroids, and other means to control systemic manifestations of acute mast cell activation and degranulation [ 2 ]. The clinical and pathological manifestations of the allergy status however can be altered by effective manipulation of immune responses to induce a level of tolerance [ 3 ]. In the past, such desensitization was attempted by means of subcutaneous immunotherapy with disappointing results [ 4 ]. It is for this reason that desensitization followed by subsequent continuous exposure to food allergen is now focusing on protocols of sublingual and/or oral administration [ 5 , 6 ]. While a remarkable level of understanding and clinical applications has been attained in the induction of peanut tolerance, this is not the case with other foods [ 3 , 5 , 6 ]. Regarding allergy to crustaceans and desensitization treatment, practical approaches remain quite limited in spite of the fact that incidence of shellfish allergy is one of the most rapidly increasing food allergies, especially in the East Asian and Pacific populations [ 7 , 8 ]. Immunotherapy for crustaceans is poorly researched and there are no standardized protocols for its implementation. The demand, however, for treatment is substantial, and several practitioners have developed genuine methods to treat allergy to crustaceans and eventually introduce to diet. As a result, many allergists have introduced to their practices desensitization protocols based on unpublished previous experience. Advanced basic research as well as wide-scale clinical trials are needed to delineate the nature of shellfish allergy and assess the sustainability of tolerance induced by immunotherapy. So far, no series or case reports of successful desensitization to crustaceans have been published following an immunotherapy protocol specific to crustaceans. There is, however, a case report of clinical improvement of symptoms upon exposure in a patient with shrimp allergy treated with sublingual immunotherapy tablets for house dust mite allergy. This report is consistent with the known cross-reactivity between shrimp and dust mite [ 9 ]. Herewith, desensitization to shrimp by means of sublingual immunotherapy is assessed for efficacy and safety with a view of validating it as a disease-modifying modality.

Charts of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice from the period January 2014–June 2023 were reviewed to identify patients with allergy to crustaceans treated with sublingual immunotherapy and to retrospectively evaluate their responses to oral challenge. Patients with a presenting history of systemic or localized reactions to crustaceans were included based on history, positive IgEs to shrimp and positive skin tests to shrimp and other crustaceans. Patients with food allergies other than crustaceans were all included in the study if they had a history of systemic reactions to crustaceans. Patients who were not compliant with the immunotherapy protocol for at least 65% of doses, averaged per year of immunotherapy, were excluded. All patients had been previously evaluated and diagnosed with shrimp allergy by a Board certified Allergist-Immunologist.

Sublingual immunotherapy with five-fold serially diluted mixtures was to be initiated at 64 ng or 320 ng/dose (0.064 mg or 0.32 mg/dose). Commercially available extracts 50% v/v by Greer formulated for skin testing for Farfantepenaeus aztecus were used to prepare the serial dilutions used for immunotherapy. Initiating doses were empirically inversely titrated against IgE levels with the 64 ng dose assigned to patients who presented with shrimp IgE > 100 kU/L and the 320 ng dose for patients who presented with IgE < 10 kU/L. In-house IgE testing was with ImmunoCAP f24. Depending on availability and patients’ circumstances, doses were escalated gradually on variable intervals which ranged from weekly to quarterly, with an intention to reach maintenance dosing over a period of 6–48 months. Target dose was 0.5 mg/dose three times a day. Within six months of reaching target dose and while immunotherapy at this level was still going on, patients were to undergo shrimp oral challenge. Challenges were performed while patients were still receiving target-dose immunotherapy at 0.5 mg/dose.

Oral challenges by administration of gradually increasing doses were performed at the Allergy Associates of La Crosse–Challenges and Biologics Unit under continuous supervision by qualified personnel. Escalation of administered doses was every 20 min. Administration of each dose was preceded by vital signs, pulse oximetry and physical examination of eyes, ear-nose-throat, skin, respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Baseline spirometry was performed at the beginning of the challenge.

The initiating oral-challenge dose was 2 mg shrimp protein. This amount was administered in the form of 0.5 ml of 0.4% w/v shrimp-protein extract, which was diluted in glycerin/water solution to make up a volume of 10 ml. This step was followed by increasing doses of fresh, lightly boiled shrimp with a starting dose of 0.425 g. Boiling time was 45–60 s depending on size. Weight was expressed as the weight of peeled (shelled), deveined and lightly boiled shrimp (as opposed to shrimp protein, which is approximately 25% of a shrimp’s weight). Target dose was 42 g shrimp weight—approximately 4 medium-size shrimps. Cumulative amount at target dosing was 81.2 g of shrimp weight. Because of availability and convenient size, three shrimp species were used for the challenges: Farfantapenaeus aztecus (red shrimp), Litopenaeus vannamei (whiteleg sprimp) and Acetes japonicus .

Reactions to increasing doses were classified as localized versus systemic. Localized Reaction was defined as:

one of any of the following: oral/peri-oral itching/numbness, peri-oral hives, hives limited to pressure points, nasal symptoms (congestion/runny nose/repetitive sneezing); or

two symptoms if any one of the above was present and the second symptom was: malaise, dizziness, abdominal cramps, nausea/vomiting, anxiety, palpitations, provided that no hypotension or hypoxia were observed and no worsening of objective clinical signs occurred with advancement to the next- higher challenge dose.

Isolated malaise, dizziness, abdominal cramps, nausea/vomiting, and signs of anxiety were recorded as localized reactions.

Systemic Reaction was defined as:

sudden drop in systolic blood pressure as a single symptom; or

generalized hives/flushing, angioedema, throat, lower respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation and involving at least two different systems, as commonly defined [ 10 ].

Sixty-six patients were identified who had been treated by sublingual immunotherapy for either systemic or localized reactions to shrimp and other crustaceans. All subjects fulfilled the criteria for diagnosis: history of reaction upon exposure consistent with immediate type (Coombs I) reaction; positive skin tests; positive shrimp IgE. Distribution of shrimp IgE concentrations and sizes of positive shrimp reactions to skin prick test are presented in Table 1 . Prior to initiation of treatment, seventeen patients (25%) had had oral challenges to confirm the diagnosis of shrimp allergy (Table 1 ). Demographics and relevant comorbidities were consistent with those of the atopic predisposition (Table 2 ). Sublingual immunotherapy with five-fold serially diluted mixtures was initiated at 6.4, 64, 160 or 320 ng/dose and was gradually escalated to target dose of 0.5 mg/dose three times a day. The sublingual immunotherapy course ranged from 5 to 72 months (average: 51 months). When length of immunotherapy exceeded the intended maximum of 48 months, the target dose of 0.5 mg protein per dose was maintained until the date of the challenge.

Eighteen patients underwent shrimp oral challenge. Twelve of the eighteen patients (66%) who were challenged after immunotherapy had originally presented with systemic reactions to crustaceans by history. Eight of them had had previous oral challenge(s) for shrimp which had resulted in systemic reactions, i.e. reactions originating in more than one system and associated changes in vital signs (Fig. 1 ).

Patients with shrimp allergy were treated with sublingual immunotherapy and challenged at the end of immunotherapy treatment to cumulative doses of 81.2–148.2 g of lightly boiled shrimp over a period of 4 h. Patients with localized symptoms upon challenge were placed on 12–20 g every other day and re-challenged after 6–9 months of regular shrimp exposure

No systemic reactions occurred during or after challenges; no patient required epinephrine (Table 2 ). Tolerance of target dose of 42 g or more was achieved in 11 patients (61%), with cumulative amount of 81.2 g for 5 patients, and cumulative amount varying from 106.2 to 148.2 g for six. Seven of these patients had originally presented with systemic reactions to crustaceans. Patients who passed the oral challenge were advised to consume shrimp and other crustaceans on a regular basis, one-two servings two–three times per week (Fig. 1 ). Since shrimp boiling time for the challenge was kept at minimum, variations in boiling time in post-challenge exposures did not appear to have an impact on tolerance as long as boiling time exceeded 60 s, according to instructions upon discharge.

Seven patients (38%) developed one or more of the following localized reactions: oral itching, nasal symptoms, localized perioral hives, localized hives at pressure points, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain upon exposure to a cumulative amount of 39.2–148.2 g shrimp during the 4 h of the challenge. Five of these patients had originally presented with systemic reactions to crustaceans (Table 2 ).

Five of the seven patients who developed localized symptoms during the challenge were subsequently placed on routine exposure to 12–20 g of shrimp (two medium-size Gulf Shrimps or one Jumbo Shrimp) every other day with a view to repeating the challenge (Fig. 1 ). Two patients who experienced localized symptoms during challenge elected to continue sublingual immunotherapy but declined regular every-other-day intake of 12–20 g shrimp because at that time they decided against introduction of crustaceans to their routine diet; on follow up, they were satisfied with the outcome of the first challenge and wished to continue immunotherapy without having to undergo a repeat challenge. Repeat challenges were performed at 6–9 months of regular every-other-day consumption. On repeat challenge, all five patients who had followed regular every-other-day consumption of 12–20 g shrimp tolerated the procedure to target doses, which ranged from 42 and 67 g (cumulative amount 81.2 and 106.2 g respectively), without symptoms (Fig. 1 ). In summary:

on 1st attempt, 11 patients (61%) passed and 7 patients (39%) experienced localized reactions

on 2nd attempt, 5 patients (100%) passed.

On routine follow-up, none of the patients who passed the original or the repeat challenge reported any adverse reactions with regular intake of shrimp at the prescribed amounts or with larger amounts of other crustaceans—lobster, crab, crayfish included—consumed with meals.

The diagnosis of an IgE-mediated permanent food allergy is a life-changing event for patients and their families. The risk of a systemic reaction upon exposure and the possibility of anaphylaxis makes a life-threatening event out of any accidental exposure even when minute amounts of protein are involved or, especially in the case of crustaceans, when aerosolized particles are likely to be inhaled. Furthermore, each systemic episode is an entirely independent event which may turn out more severe than previous ones [ 1 , 2 , 11 ]. Adding to the uncertainty of systemic reactions due to food allergies, there is no diagnostic modality that would predict severity of reaction: skin tests and immunological assays for IgE antibody levels only predict likelihood of reaction and not severity [ 12 ]. The unpredictability of each reaction and the possibility of a fatal outcome places a constant burden on affected people who live under the threat of a sudden systemic reaction on practically every encounter, no matter how trivial, with food. Further complicating things, information on ingredients lists of manufactured foods is often misleading or erratic, and personnel involved in the preparation and serving of meals may lack access to relevant information. In light of these facts, long-term continuous control of immune responses to food allergens is a pressing necessity. Allergen-specific immunotherapy is the only disease-modifying modality for food allergy. Its implementation in a feasible, efficient, cost-effective, and safe way is the mainstay of long-term management [ 13 ]. With the present report, sublingual immunotherapy is presented, for the first time, as a useful modality in the long-term management of allergy to crustaceans. Administration of sublingual immunotherapy at home three times a day was tolerated by all patients and compliance remained satisfactory during the treatment period. During challenges, no systemic reactions were observed. Subsequent regular exposure to shrimp every other day was also tolerated without problems. Patients who remained asymptomatic during challenge, as well as patients who developed symptoms of localized nature with their first challenge and were placed on a limited-exposure protocol of 15–20 g every other day, have not developed symptoms with subsequent exposures to larger amounts of crustaceans. Consumption of shrimp at standard-serving (3 oz.) was not associated with symptoms on follow-up in either group.

The mechanisms of tolerance induction through sublingual immunotherapy have been extensively studied for long, but several of its long-term aspects are yet to be delineated [ 14 ]. Sublingual immunotherapy is user-friendly, inexpensive, free of significant complications, and is characterized by compliance levels superior to those of other forms of immunotherapy for allergens [ 15 ].

Regarding the long-term sustained outcome of desensitization, little is known and is mostly derived from experience with other food desensitization protocols. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy has been shown to result in decreased peanut-specific basophil activation and skin prick reactivity, as well as other parameters of IgE-effected sensitivity [ 16 ]. Upon discontinuation of sublingual immunotherapy, however, less than 11% of followed subjects had achieved sustained unresponsiveness [ 16 ]. Since sustained-unresponsiveness studies cannot be pursued in a private-practice setting, this issue will have to be addressed by larger-scale research projects. The patients of this cohort have all been advised to continue exposure to shrimp indefinitely at a minimum dose of 20 g every other day. As of the time of writing this report, no adverse events have been reported following regular intake of said amounts or with consumption of usual servings of crustaceans.

A pertinent feature of the present study is the assessment of symptoms and their evaluation in regard to their characterization as systemic or not. The resulting decision to continue with the challenge versus halting it was of major importance for the outcome of the challenges. By consensus, the emergence of a second symptom from a different system calls for an obligatory definition of the reaction at hand as an immune response of systemic nature [ 2 , 10 , 11 ]. In view of the risk for anaphylaxis, such a development would have led to cessation of the challenge and its assessment as a failure. For certain symptoms, however, a departure from the literary application of these criteria practice may be necessary, if these symptoms can be safely attributed to non-immune events, especially anxiety-related responses. In our study, certain symptoms were characterized as localized events even if they occurred along with other localized symptoms from a different system. Specific criteria for such an assessment were applied. Symptoms were termed as localized if: (i) they could be directly and unequivocally ascribed to anxiety, (ii) their severity had no measurable equivalent in objective parameters, (iii) increasing challenge doses led to no worsening of any other symptom and no escalation of the reaction was observed. The highly variable, subjective, and heterogenous nature of malaise, dizziness, nausea/vomiting, abdominal cramps, anxiety, tachycardia, and flushing is to be considered before the clinician in charge of the challenge arrives at the conclusion that mast cell degranulation of systemic magnitude has occurred. Without this modification and careful evaluation of symptoms within their context and timeliness, the rate of falsely-assessed failed food challenges is likely to be over-appreciated to the detriment of the patient’s interest.

A limitation of this study is that the challenges reported were all conducted with shrimp and this experience does not reflect established outcomes regarding other crustaceans, even though on follow up patients reported tolerance to other crustaceans. There is also a certain possibility that the tolerance that is demonstrated here may be limited to the three shrimp species that were exclusively used in the challenges. Furthermore, tropomyosin component testing was not performed and sensitization to Pen a 1 versus other shrimp allergens was not assessed [ 17 ]. Cross-reactivity with dust mite antigens was not studied either.

Fifty-three (80%) of the shrimp-allergic patients of the study had a history of a systemic reaction to shrimp, which was confirmed in 17 (25%) by baseline oral challenge. However, among the patients who underwent a post-treatment challenge, 12 patients (68%) had a history of systemic reactions and only 8 patients (44%) also had a positive oral shrimp baseline challenge before initiation of treatment. These discrepancies reflect a relatively higher willingness among patients with a history of localized-nature reactions to undergo a challenge, as well as for providers to order one.

A significant limitation of this study was the lack of pre-treatment baseline oral challenges for shrimp for 49 (75%) subjects. In a prospective study, routine baseline oral challenges would have been the standard of diagnosis. This drawback is inherent to the conditions of this study which was conducted in the setting of a private practice. The safety of the diagnosis of shrimp allergy for 75% subjects was based on the combination of the following positive findings: (i) all patients had been assessed by at least two Board certified Allergists from different practices, all of whom confirmed either the diagnosis of a systemic response, or a risk for a response serious enough to necessitate presription of Epinephrine and specific diet measures; (ii) all patients had positive shrimp skin tests performed by at least two different Allergists; (iii) by the time the post-treatment challenge was attempted, all patients had positive shrimp IgEs on at least 6 different occasions, several months apart, performed by different laboratories. The specificity of these combined data, although not as valid as a baseline oral challenge, was considered satisfactory for the purpose of treatment.

Desensitization to shrimp by sublingual immunotherapy over a period of 5–72 months is assessed as a safe and effective treatment modality in the chronic management of allergy to crustacean. Tolerance to exposure is achieved and maintained while regular administration of modest amounts of shrimp continues. Whether the immune modification induced by sublingual immunotherapy is permanent resulting in sustained tolerance, or the achieved degree of desensitization depends on regular exposure is not known; therefore, following oral challenge, regular consumption three-four times per week is recommended.

Data availability

Study data are available at the Allergy Associates of La Crosse.

Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, et al. Food Allergy: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1016–25.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy. 2014;69(5):590–601.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mansfield L. Successful oral desensitization for systemic peanut allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(2):266–76.

Nelson HS, Lahr J, Rule R, et al. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:744–51.

Vickery BP, Vereda A, Casale TB, et al. AR 101 oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. PALISADE Group of Clinical Investigators. NEJM. 2018;379(21):1991–2001.

Kim EH, Yang L, Ye P, et al. Long-term sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy in children: clinical and immunological evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(5):1320–6.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wai CY, Leung PS. Emerging approaches in the diagnosis and therapy in shellfish allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;22(3):202–12.

Wai CY, Leung NY, Hou Chou K, et al. Overcoming shellfish allergy: How far have we come? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2234.

Cortellini G, Spandolini I, Santucci A, et al. Improvement of shrimp allergy after sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites: a case report. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;43(5):162–4.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Randolph C, et al. Anaphylaxis – a practice parameter update 2015. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(5):341–84.

Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary, report—Second National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:391–7.

Ochfeld EN, Makhija M. In vitro testing for allergic and immunological diseases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40:480–4.

Lei DK, Saltoun CA. Allergen immunotherapy: definition, indications, and reactions. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40:369–71.

Allam JP, Novak N. Immunological mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(6):564–9.

Okubo K, Izuhara K. The status of sublingual immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67(3):299–300.

Burks AW, Wood RA, Jones SM, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: long-term follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(5):1240.

Gámez C, Sánchez-García S, Ibáñez MD, et al. Tropomyosin IgE-positive results are a good predictor of shrimp allergy. Allergy. 2011;66(10):1375–83.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Cheng Her, Allergy Associates of La Crosse, Wisconsin; and Anne Hendrickson and Beth Davidson, Allergy Choices, Inc., Onalaska, Wisconsin for their valuable technical support.

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Aquinas High School, La Crosse, WI, USA

Lydia M. Theodoropoulou

Allergy Associates of La Crosse, Onalaska, WI, USA

Niamh A. Cullen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Lydia M. Theodoropoulou: collection and analysis of data, writing of manuscript, presentation of abstract and incorporation of feedback. Niamh A. Cullen: design of study, supervision, editing of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lydia M. Theodoropoulou .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Consent to initiate immunotherapy and to proceed with immunotherapy and supervised oral challenges was obtained by all subjects or subjects’ parent(s).

Consent for publication

Hereby, the authors L.M. Theodoropoulou and N.A. Cullen grant permission to publish the present research paper with the title: “Sublingual immunotherapy for allergy to shrimp: the nine-year clinical experience of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice.”

Competing interests

Both authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to this study.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Theodoropoulou, L.M., Cullen, N.A. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergy to shrimp: the nine-year clinical experience of a Midwest Allergy-Immunology practice. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 20 , 33 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-024-00895-7

Download citation

Received : 13 August 2023

Accepted : 28 April 2024

Published : 11 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-024-00895-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology

ISSN: 1710-1492

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Switch language:

Food Allergy Awareness Week 2024: How can new treatments target an unmet need?

IgGenix is planning to initiate a clinical trial later this year investigating its peanut allergy monoclonal antibody IGXN001.

- Share on Linkedin

- Share on Facebook

Food Allergy Awareness Week, which runs from 12 to 18 May this year, is drawing attention to the innovations under development for treating food allergies.

Earlier this year, a breakthrough in the food allergy space was when Novartis and Roche’s Xolair (omalizumab) won US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Initially approved for asthma in 2003, its label was expanded, making it the first FDA-approved drug to reduce allergic reactions in people with IgE-mediated food allergies. This classification includes food-based allergens such as peanuts, milk, eggs, wheat, cashew nuts, hazelnut, or walnut.

Go deeper with GlobalData

LOA and PTSR Model - Lirentelimab in Peanut Allergy

Peanut allergy drugs in development by stages, target, moa, roa, mo..., premium insights.

The gold standard of business intelligence.

Find out more

Related Company Profiles

Novartis ag, roche diagnostics international ltd, eli lilly and co, aimmune therapeutics inc.

Still, despite the observed efficacy with Xolair, the drug can take a few months to start working properly, highlights Jessica Grossman, CEO of San-Francisco-based allergy company IgGenix.

“Xolair is a great step forward for the allergic community. However, there still are some limitations if it takes 16 weeks to work,” she said.

IgGenix is developing an IgG4 monoclonal antibody-based therapeutic called IGXN001 specifically for peanut allergies. The candidate is expected to protect against accidental exposure to peanut allergens within days of administration.

The company, which spun out of Stanford University in 2019, closed a $40m Series B financing round in February 2024 to advance IGXN001 to the clinic. The funding round was led by Alexandria Venture Investments and Eli Lilly and Company.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

Grossman said the company is initiating a Phase I clinical trial later this year following positive preclinical pharmacokinetic (PK) studies: “In our animal studies, the PK of the antibody is modelled to be about 30 days in humans. What we’re hoping that means in humans is that that the antibody will have a relatively long PK or a relatively long concentration time in the blood, longer than Xolair.”

The Phase I trial start, targeting late Q3 or Q4 2024, will measure safety as the primary endpoint in otherwise healthy individuals with peanut allergies. The trial design will involve a single-ascending dose across three cohorts and will also examine the blood concentration PK of IGXN001.

“We are thinking from some of our modelling [data] that we’ll be able to dose every other month, which would be a big advantage,” added Grossman.

There is certainly innovation in the peanut allergy space, highlighted by Intrommune Therapeutics’ desensitisation immunotherapy , which is delivered as toothpaste. The company announced positive results from the Phase I OMEGA clinical trial (NCT04603300) investigating INT301 in November 2023. Data highlighted that 100% of those treated with the toothpaste consistently tolerated the highest dose of the allergen.

There are also approved medications to treat peanut allergies, including Palforzia (arachis hypogaea) . Nestlé acquired Palforzia through its $2.6bn takeover of Aimmune Therapeutics in 2020. However, Nestlé shifted the drug to Swiss biopharma Stallergenes Greer in September 2023, following a “ slower than expected adoption by patients and healthcare professionals”.

Palforzia needs to be taken daily and carries a warning for anaphylaxis on its label. Grossman commented on oral medications in the young patient population: “Generally, oral immunotherapy isn’t for them. There’s definitely an unmet need in the young adult population.”

DBV Technologies , which is developing an allergen patch called Viaskin, has faced multiple challenges in getting it to the market in the past few years, following a clinical hold and the FDA requesting additional data in April 2023.

According to a report on GlobalData’s Pharma Intelligence Center, the food allergy market was valued at $213.9m in 2020 globally and is forecast to reach $2.7bn by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 28.8%. In the eight major markets (UK, US, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Australia, and Canada), GlobalData epidemiologists forecast that there will be more than seven million peanut allergy cases in 2027.

Sign up for our daily news round-up!

Give your business an edge with our leading industry insights.

More Relevant

CinDome Pharma secures $40m to advance gastroparesis treatment

Amgen's imdelltra receives fda approval for lung cancer treatment, gene-modified cell therapy to target cd33 for relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia by sichuan kelun biotech biopharmaceutical for relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: likelihood of approval, gene-modified cell therapy to target cd33 for relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia by sichuan kelun biotech biopharmaceutical for refractory acute myeloid leukemia: likelihood of approval, sign up to the newsletter: in brief, your corporate email address, i would also like to subscribe to:.

Pharma Technology Focus : Pharmaceutical Technology Focus (monthly)

Thematic Take (monthly)

I consent to Verdict Media Limited collecting my details provided via this form in accordance with Privacy Policy

Thank you for subscribing

View all newsletters from across the GlobalData Media network.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Allergy

Nutritional management of food allergies: Prevention and treatment

Ludovica leone.

1 Pediatric Unit - Foundation, IRCCS Ca' Granda - Ospedale, Maggiore, Policlinico, Milan, Italy

Alessandra Mazzocchi

2 Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milano, Milano, Italy

Laura Maffeis

Valentina de cosmi, carlo agostoni.

An individualized allergen avoidance plan is the cornerstone of the nutritional management of food allergy (FA). In pediatric age, the main objective is preventing the occurrence of acute and chronic symptoms by avoiding the offending food(s) and providing an adequate, nutritionally balanced and personalized diet at the same time. For this reason, the presence of a trained dietitian is recommended in order to meet nutritional needs of patients with FA and to provide a tailored nutritional plan, minimizing the impact of FA on quality of life and maintaining optimal growth.

1. Introduction

Data from the most recent literature show the prevalence of allergic disorders increasing. In particular, to date, in every ten people, one lives with a food allergy (FA) and the prevalence is higher in the pediatric population.

Being a multifactorial disease, FA is influenced by genetics, environment, and their interactions. The main risk factors involved in the expression or sensitization to FA include: sex (in particular, being male in children), race/ethnicity (the risk is higher among Asian and black children); genetics. Moreover, other potential risk factors can also contribute: atopic comorbidity, increased hygiene, microbiome, serum vitamin D levels, diet (i.e., low intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids, reduced consumption of antioxidants), increased use of antiacids, obesity, timing of food introduction and exposure to foods in a different way from the gastrointestinal one.

In high-income countries, cow's milk, eggs, wheat, fish and shellfish, peanuts, nuts, and soy are the most frequent responsible for FA in children. Above them, some food allergies have a high rate of resolution before adolescence. Data from literature say that milk allergy resolves in up to 50% of patients by age 5–10 years, egg allergy resolves about in half of the cases by ages 2–9 years, wheat allergy in 50% of children affected by age 7 years, and soy allergy in 45% by age 6 years.

Other food allergies typically persist in childhood; peanut allergy is estimated to resolve in about 20% of patients by age 4 years, tree nut allergy in only 10% of patients. Allergy to seeds, fish, and shellfish are considered persistent ( 1 ).

Excluding nutritionally essential foods from the diet on one's own initiative may cause harm rather than benefit, especially in a young child. Proper dietary guidance should be given only on the basis of a definite diagnosis of FA through specific examinations.

A precise identification of the culprit foods is essential for an individualized management of the patient. In this perspective, diagnostic methods, like component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) and the epitope reactivity, can allow a more targeted analysis of the disease and a tailored therapeutic plan. Clinical history, skin prick test, food-allergen IgE, exclusion diets and subsequent oral food challenges are important FA diagnostic tools ( 2 ).

The oral food challenge (OFC) can be performed either open or single-blind food challenge, or better as double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). Actually, DBPCFC is still the gold standard for FA diagnosis ( 3 ) even if its execution in pediatric age can be more difficult that in adults. Moreover, OFC is a procedure that is not free from major risks (i.e., serious anaphylactic reactions) ( 4 ).

Recently, other diagnostic test in vitro , such as CRD and the basophil activation test (BAT) have been developed to estimate the risk of serious, life-threating reactions before OFC ( 5 ).

The diagnosis of FA makes it possible to identify which foods need to be eliminated and is essential in order to be able to devise a nutritionally balanced, individualized exclusion diet. Allergic children and parents must, in addition, be well educated in the interpretation and reading of nutrition labels in order to learn how to avoid specific and hidden allergens, all of which make it possible to prevent new allergic reactions and thus the onset of more severe symptoms.

2. Growth in allergic children: A wake-up call

Inadequate growth in children affected by food allergy, compared with their healthy peers, is well documented. Some studies have found lower energy intake in the diets of allergic children and different growth patterns compared with healthy children, even when nutrient intake is similar. The hypothesis for the poor growth in this pediatric population can be related not only to the high number of foods to be excluded due to allergy but also to a persistent sub-inflammatory state of the gastrointestinal mucosa. It may reduce the absorption of fuels and substrates and increase intestinal permeability and, consequently, nutrient loss ( 6 ).

In contrast, other studies point out that obesity can also occur in allergic children due to unbalanced diets and poor food choices ( 7 ).

This potential difference in growth highlights the need to make every effort to optimize nutritional intervention.

From a nutritional point of view, measuring growth in children reflects the adequacy of the diet. However, growth control must be followed by regular evaluation of other signs of deficiency. Recurrent reviews of food intake to assess possible supplementation are also essential; this highlights the importance of appropriate counseling by an expert dietitian, who can promptly and early manage nutritional problems resulting from the exclusion of specific foods.

It is well known that childhood is a period of rapid growth and that optimal and balance intake of micro and macronutrients is fundamental for optimal growth.

Weight, length, Body mass index, and head circumference are the indicators mainly used to measure growth rates in infants and children.

Nowadays, World Health Organization propose cutoff points, expressed in z-score units, to evaluate inappropriate nutritional status. The same z-score units are used in epidemiological studies, too.

3. Nutritional intervention

3.1. prevention and treatment.

The first three years of life are considered an age of opportunity and intervention. During this period of life nutritional factors, among others, may impact the risk of developing allergies through epigenetic mechanisms. Consequently, the nutritional interventions are well recognized as central players both in the prevention and treatment of food allergies. Recently, different clinical approaches emerged. The traditional approach consisted of protracted food allergen avoidance.

This practice contributed to a dramatic increase of anaphylaxis.

On the contrary, the new approach suggests to introduce complementary foods in the diet between 4 and 6 months of life, even in infants at higher allergic risk. Others nutritional strategies potentially able to educate the immune system towards oral tolerance are the approach of gradual introduction of small quantities of foods allergens in a less allergenic form to higher and more allergenic quantities of food allergens.

Delaying food introduction does not protect against allergy development. Excessive delay in the introduction of allergenic foods could increase the risk of sensitization, instead. Two randomized clinical trials showed that the early introduction of peanuts and other food allergens can reduce the risk of FA ( 8 , 9 ). More recently, two population-based studies including more than 7,000 participants in Melbourne, Australia, examined the impact of earlier peanut introduction on the frequency of peanut allergy. Peanut introduction in the first year of life increased from 28 to 88% over this time period. However, there was a slight diminution in peanut allergy prevalence, from 3.1 to 2.6%. This result highlighted that other interventions should be done in order to prevent peanut allergy in the general population ( 10 ).

This led to the hypothesis that similar mechanisms of defense may be present for other food as for peanut and that different “windows of opportunity” may exist for each food. Additional approaches will be necessary to prevent food allergies in infants who fail to benefit from early allergen introduction.