- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Thesis 101: A Guide for Social Science Thesis Writers

Welcome to the harvard library, finding a researchable question, finding scholarly resources in your field, covid-19 - information & resources, helpful library services & tools.

- Subject Guide

Sue Gilroy , Librarian for Undergraduate Writing Programs and Liaison to Social Studies ([email protected])

Diane Sredl , Data Reference Librarian and Liaison to the Department of Economics ([email protected])

Kathleen Sheehan , Research Librarian and Liaison to the Depts. of Government, Psychology & Sociology ([email protected])

Congratulations on choosing to write a senior thesis! This guide brings together resources and information to help you as you work though the thesis research and writing process.

What is Already Known

Handbooks are a stock-in-trade for academic researchers. Typically, they're edited volumes, with chapters written by authorities -- or recognized experts, and they synthesize current "consensus" thinking around a particular topic, the most widely accepted perspectives on a topic They usually contain extensive bibliographies which you can mine as well.

- Cambridge Handbooks O nline

- Cambridge Histories Online

- Oxford Handbooks Online

- Very Short Introductions

Current Trends & Questions

Literature reviews are essays that help you easily understand—and contextualize—the principal contributions that have been made in your field. They not only track trends over time in the scholarly discussions of a topic, but also synthesize and connect related work. They cite the trailblazers and sometimes the outliers, and they even root out errors of fact or concept. Typically, they include a final section that identifies remaining questions or future directions research might take.

Among the databases for finding literature reviews, we recommend you start with:

- Annual Reviews offers comprehensive collections of critical reviews by leading scholars.

- Web of Science can be a powerful tool in uncovering literature reviews. A keyword topic search in Web of Science much like HOLLIS, will return results that you can then sift through using a variety of left-side filter categories. Under document type, look for the review.

Prioritizing My Reading

- Oxford Bibliographies Online combine the best features of the annotated bibliography with an authoritative subject encyclopedia. Entries identify key contributions to a topic, idea, person, or event and indicate the value of the work.

- Anthropology

- Social Studies

- Multidisciplinary

Research Guide:

- Anthropology Research

Key Databases:

- Anthropology Plus

- Anthropology Online

Library Research Contact:

Susan Gilman , Librarian for Tozzer Library

- Economics Research

- Business Source Complete

- Business Premium Collection

Diane Sredl , Data Reference Librarian

- Library Research Guide for History

- America History & Life

- Historical Abstracts

Fred Burchsted , Research Librarian

Anna Assogba , Research Librarian

- Sociology: a Guide to Research Resources

- Sociology Database

- Social Sciences Premium

Kathleen Sheehan , Research Librarian

- Government: a Guide to Research Resources

- Worldwide Political Science Abstracts

Social Studies tends to be so interdisciplinary that it's sometimes hard to offer students a "one-size fits all" starting point.

Research Guides :

- Research Guides for Social Studies 98 (junior tutorials) may also cover -- broadly speaking -- an area of interest and you may find some leads there. But the 1:1 consult often can't be beat for locating the databases and the primary sources that are best suited to your project!

- If your thesis is applied, our Social Sciences Premium database is sometimes, along with HOLLIS , a good jumping off point.

- If your thesis is theoretical, resources like Phil Papers or Philosopher's Index are also recommended.

Sue Gilroy , Liaison to Social Studies, Lamont Library

- Contemporary Issues in Psychology

Key Database:

- Web of Science

Michael Leach , Head, Collection Development, Cabot Library

Research Guides:

- Research Travel Checklist

- HOLLIS User Guide

- Public Opinion Sources

- Beginner's Guide to Locating and Using Numeric Data

- Conducting Research Interviews: Selected Resources

- Academic Search Premier

- A Harvard COVID-19 Resource Roundup

- Harvard Library Restart Updates

- How to Borrow Materials and Use Our Services During COVID-19

- HathiTrust for digitized materials

- Scan & Deliver

- Harvard Library Purchase request

- Check Harvard Library Bookmark - Use this bookmarklet to get quick access to subscriptions purchased by Harvard Library.

- Zotero: Getting Started - A tool for saving, organizing and formatting your research sources.

- Ask a Librarian - Send us your question virtually.

- Borrow Direct & ILL to borrow materials not currently available from the Harvard Library

- Harvard Map Collection

- Visualization Support

- Qualitative Research Support

The contents of this Guide are drawn largely from other Guides authored by Sue Gilroy, Librarian for Undergraduate Writing Programs and Liaison to Social Studies.

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 1:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/thesis101

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How to Write a Social Science or Humanities Thesis/Dissertation

Writing a thesis/dissertation is a huge task, and it is common to feel overwhelmed at the start. A thesis and a dissertation are both long pieces of focused research written as the sum of your graduate or postgraduate course.

The difference between a thesis and a dissertation can depend on which part of the world you are in. In Europe, a dissertation is written as part of a Master’s degree, while a thesis is written by doctoral students. In the US, a thesis is generally the major research paper written by Master’s students to complete their programs, while a dissertation is written at the doctoral level.

The purpose of both types of research is generally the same: to demonstrate that you, the student, is capable of performing a degree of original, structured, long-term research. Writing a thesis/dissertation gives you experience in project planning and management, and allows you the opportunity to develop your expertise in a particular subject of interest. In that sense, a thesis/dissertation is a luxury, as you are allowed time and resources to pursue your own personal academic interest.

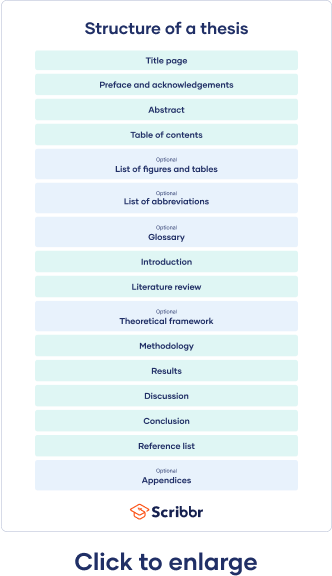

Writing a thesis/dissertation is a larger project than the shorter papers you likely wrote in your coursework. Therefore, the structure of a thesis/dissertation can differ from what you are used to. It may also differ based on what field you are in and what kind of research you do. In this article, we’ll look at how to structure a humanities or social science thesis/dissertation and offer some tips for writing such a big paper. Once you have a solid understanding of how your thesis/dissertation should be structured, you will be ready to begin writing.

How are humanities and social science thesis/dissertations structured?

The structure of a thesis/dissertation will vary depending on the topic, your academic discipline, methodology, and the place you are studying in. Generally, social science and humanities theses/dissertations are structured differently from those in natural sciences, as there are differences in methodologies and sources. However, some social science theses/dissertations can use the same format as natural science dissertations, especially if it heavily uses quantitative research methods. Such theses/dissertations generally follow the “IMRAD” model :

- Introduction

Social science theses/dissertations often range from 80-120 pages in length.

Humanities thesis/dissertations, on the other hand, are often structured more like long essays. This is because these theses/dissertations rely more heavily on discussions of previous literature and/or case studies. They build up an argument around a central thesis citing literature and case studies as examples. Humanities theses/dissertations tend to range from between 100-300 pages in length.

The parts of a dissertation: Starting out

Never assume what your reader knows! Explain every step of your process clearly and concisely as you write, and structure your thesis/dissertation with this goal in mind.

As you prepare your topic and structure your social science or humanities thesis/dissertation, always keep your audience in mind. Who are you writing for? Even if your topic is other experts in the field, you should aim to write in sufficient detail that someone unfamiliar with your topic could follow along. Never assume what your reader knows! Explain every step of your process clearly and concisely as you write, and structure your thesis/dissertation with this goal in mind.

While the structure of social science and humanities theses/dissertations differ somewhat, they both have some basic elements in common. Both types will typically begin with the following elements:

What is the title of your paper?

A good title is catchy and concisely indicates what your paper is about. This page also likely has your name, department and advisor information, and ID number. However, the specific information listed varies by institution.

Acknowledgments page

Many people probably helped you write your thesis/dissertation. If you want to say thank you, this is the place where it can be included.

Your abstract is a one-page summary (300 words or less) of your entire paper. Beginning with your thesis/dissertation question and a brief background information, it explains your research and findings. This is what most people will read before they decide whether to read your paper or not, so you should make it compelling and to the point.

Table of contents

This section lists the chapter and subchapter titles along with their page numbers. It should be written to help your reader easily navigate through your thesis/dissertation.

While these elements are found at the beginning of your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation, most people write them last. Otherwise, they’ll undergo a lot of needless revisions, particularly the table of contents, as you revise, edit, and proofread your thesis/dissertation.

The parts of a humanities thesis/dissertation

As we mentioned above, humanities and some social science theses/dissertations follow an essay-like structure . A typical humanities thesis/dissertation structure includes the following chapters:

- References (Bibliography)

The number of themes above was merely chosen as an example.

In a humanities thesis/dissertation, the introduction and background are often not separate chapters. The introduction and background of a humanities thesis/dissertation introduces the overall topic and provides the reader with a guide for how you will approach the issue. You can then explain why the topic is of interest, highlight the main debates in the field, and provide background information. Then you explain what you are investigating and why. You should also specifically indicate your hypothesis before moving on to the first thematic chapter.

Thematic chapters (and you can have as many of them as your thesis/dissertation guidelines allow) are generally structured as follows:

- Introduction: Briefly introduce the theme of the chapter and inform the reader what you are going to talk about.

- Argument : State the argument the chapter presents

- Material : Discuss the material you will be using

- Analysis : Provide an analysis of the materials used

- Conclusion : How does this relate to your main argument and connect to the next theme chapter?

Finally, the conclusion of your paper will bring everything together and summarize your argument clearly. This is followed by the references or bibliography section, which lists all of the sources you cited in your thesis/dissertation.

The parts of a social science thesis/dissertation

In contrast to the essay structure of a humanities thesis/dissertation, a typical social science thesis/dissertation structure includes the following chapters:

- Literature Review

- Methodology

Unlike the humanities thesis/dissertation, the introduction and literature review sections are clearly separated in a social science thesis/dissertation. The introduction tells your reader what you will talk about and presents the significance of your topic within the broader context. By the end of your introduction, it should be clear to your reader what you are doing, how you are doing it, and why.

The literature review analyzes the existing research and centres your own work within it. It should provide the reader with a clear understanding of what other people have said about the topic you are investigating. You should make it clear whether the topic you will research is contentious or not, and how much research has been done. Finally, you should explain how this thesis/dissertation will fit within the existing research and what it contributes to the literature overall.

In the methodology section of a social science thesis/dissertation, you should clearly explain how you have performed your research. Did you use qualitative or quantitative methods? How was your process structured? Why did you do it this way? What are the limitations (weaknesses) of your methodological approach?

Once you have explained your methods, it is time to provide your results . What did your research find? This is followed by the discussion , which explores the significance of your results and whether or not they were as you expected. If your research yielded the expected results, why did that happen? If not, why not? Finally, wrap up with a conclusion that reiterates what you did and why it matters, and point to future matters for research. The bibliography section lists all of the sources you cited, and the appendices list any extra information or resources such as raw data, survey questions, etc. that your reader may want to know.

In social science theses/dissertations that rely more heavily on qualitative rather than quantitative methods, the above structure can still be followed. However, sometimes the results and discussion chapters will be intertwined or combined. Certain types of social science theses/dissertations, such as public policy, history, or anthropology, may follow the humanities thesis/dissertation structure as we mentioned above.

Critical steps for writing and structuring a humanities/social science thesis/dissertation

If you are still struggling to get started, here is a checklist of steps for writing and structuring your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation.

- Choose your thesis/dissertation topic

- What is the word count/page length requirement?

- What chapters must be included?

- What chapters are optional?

- Conduct preliminary research

- Decide on your own research methodology

- Outline your proposed methods and expected results

- Use your proposed methodology to choose what chapters to include in your thesis/dissertation

- Create a preliminary table of contents to outline the structure of your thesis/dissertation

By following these steps, you should be able to organize the structure of your humanities or social science thesis/dissertation before you begin writing.

Final tips for writing and structuring a thesis/dissertation

Although writing a thesis/dissertation is a difficult project, it is also very rewarding. You will get the most out of the experience if you properly prepare yourself by carefully learning about each step. Before you decide how to structure your thesis/dissertation, you will need to decide on a thesis topic and come up with a hypothesis. You should do as much preliminary reading and notetaking as you have time for.

Since most people writing a thesis/dissertation are doing it for the first time, you should also take some time to learn about the many tools that exist to help students write better and organize their citations. Citation generators and reference managers like EndNote help you keep track of your sources and AI grammar and writing checkers are helpful as you write. You should also keep in mind that you will need to edit and proofread your thesis/dissertation once you have the bulk of the writing complete. Many thesis editing and proofreading services are available to help you with this as well.

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

What are the parts of a social science thesis/dissertation? +

A social science thesis/dissertation is usually structured as follows:

How long is a typical social science thesis/dissertation? +

What are the parts of a humanities thesis/dissertation +.

Humanities theses/dissertations are usually structured like this:

- Thematic Chapters

What is the typical structure of a thematic chapter in a humanities thesis/dissertation? +

A thematic chapter in a humanities thesis/dissertation is structured like this:

How long is a typical humanities thesis/dissertation? +

A typical humanities thesis/dissertation tends to range from 100 to 300 pages in length.

How to Write a Bachelor/Master Thesis in Social Sciences (Step-by-Step + Examples)

- Post published: April 19, 2021

- Post category: Resources

- Post last modified: September 10, 2024

Hello Auré from 2021!

It’s 2024 and we now have AI (and a bunch of other tools) to help us!

I recommend you use the following tools to write your thesis:

- Consensus app : Find and summarize papers with AI.

- S cispace : same thing as Consensus.

- Grammarly : find and correct grammar and vocabulary mistakes in your text. Alternatively, you can use Microsoft Editor or QuillBot which, if you get the paid version, will also offer an AI assistant and a plagiarism checker.

- Research Rabbit : Visualize and organize information from papers.

- Zotero : collect, organize, and annotate research papers.

- Notion : it’s a note-taking app with an embedded AI helping you build your own Wikipedia. Some people also like Obsidian and Microsoft has created its own Loop . Recently, somebody else made AirGraph .

- Turboscribe : Turboscribe transcribes videos and recordings. It’s the cheapest service and the cheapest way to get the entire lecture automatically written down.

- Notta : Notta will record, transcribe, translate, and summarize your live and online lectures. There’s also Otter , Jamworks , and Studyfetch .

- Kipper.ai : Kipper will rewrite an AI-written essay so that it doesn’t look like AI. Not sure what it’s worth but you can also build a GPT that does that in ChatGPT.

- Mem : Mem enables you to ask an AI that will search for the answer to your question in the notes you’ve taken with it. Voicenotes does the same thing but also enables you to record an unlimited number of voicenotes an unlimited number of times. Voicenotes is priced at $10/month or $59 for a lifetime.

- Microsoft to-do : the best to-do list app out there.

- Sci-hub : Sci-hub’s mission is to make access to science free for all. The URL may change as time passes. You can always check this to find the updated one.

- Libgen : the biggest free library in the world.

- Anna’s archive : a team merged Sci-Hub and Libgen together to create Anna’s archive.

- ChatGPT , Claude , Gemini , Grok : I use AI to get feedback on what I write and to understand complex ideas and concepts. I use ChatGPT which I pay for because they let you create GPTs which improve productivity a lot. I share the subscription with a friend of mine, so we only pay €10 per month each.

- Perplexity : AI search engine.

- Microsoft Math Solver : it helps you understand, solve, and do math, like Photomath . For advanced level, use Wolfram Alpha .

Good luck! I didn’t change the rest of the article so always remember that whatever you need help with, there will be an AI tool for that.

When it comes to theses, the guidelines depend on your university, your program, and your supervisor. Always make sure to follow these rules first.

I have written three theses in my academic career and passed all of them the first time.

This article will explain how to write a bachelor or a master thesis in social sciences.

You’ll learn:

- how I found my research question and two guaranteed methods to do so

- how I structured my work

- the five parts of theses and how to write them

- the different research methods and which ones to select

- how to find respondents

- the mindset to adopt to write your thesis

- how not to be late

You can also download my three theses to have a look at them yourself.

Table of Content

Click to expand/collapse

Part 1: The Theory

- Finding Yout Topic

What to Do if You Cannot Find a Thesis Topic?

Finding the research question and the introduction of your thesis, how to establish the theoretical framework of your thesis, which research method to select for your thesis, how to conduct the research for your thesis, how to find respondents for your interview, transcript analysis and presenting the results of your research, how to conclude your thesis, part 2: the mental behind writing a thesis.

- Don’t Focus on the End Goal – Focus on the Next Step Instead

Break the Routine

Load up on things to do, realize what your time is worth.

- You’ll End up Dying at Some Point…

- Use Parkison’s Law

The Bottom Line

How to write a thesis, finding your topic.

The first thesis was the most complicated to write.

Even though I was studying communication, the theme I had chosen was “business model innovation” because it looked interesting to me.

Initially, I had decided to write something related to online news websites.

I wrote my research proposal and sent it to my supervisor.

He hated it and gave me zero.

While everyone in my class was already contacting people to interview, I had to do it all over again.

But I didn’t want to.

I was angry, and I considered quitting my bachelor’s altogether.

I wrote an email to the faculty asking to change group and join a political-themed thesis class.

They said no. Great.

I wouldn’t graduate then.

As I was weighing my options, an idea came to me.

I had written days earlier a paper for another course about the challenges that TV stations had to face due to Netflix and Amazon.

I thought the theme was great for my thesis because it had all I needed: innovation, media, and business.

I asked my supervisor if I could research this theme, he said yes, and off I was.

The second thesis was easier. Written in the context of a master’s in management, I had decided to base it on the first one but with another industry.

Instead of writing about Netflix VS TV stations, I wrote about hotels VS Airbnb.

I bought a ticket to Colombia and wrote the paper under the sun of Medellin.

For my third thesis, I wanted to analyze the power of the US, China, and Russia.

However, it was more suited for a book, so I didn’t do it and wrote instead about an idea I wanted to publish in Quillette (but they never accepted it).

One day, as I was daydreaming, I wondered how we could improve political decision-making.

So I looked at how private companies handled their own decision-making.

Turns out that they use data, algorithms, and AI.

So I thought that political decision-making would probably come to that point as well, with all the consequences on democracy.

That idea stayed in my mind, so I wrote about technological decision-making in politics, namely data science within the EU Commission.

Take a paper you already wrote and derive your thesis topic from this paper.

Let’s be honest, it is difficult to randomly come up with ideas to research.

Look at what you have already done, and go deeper.

The alternative is to take a paper you enjoyed reading and to look at their “suggestion for follow-up research” section.

A thesis is no more than an answer to a question.

Look around you, read the newspapers, ask questions.

What are people wondering about? What are the impacts of new technologies? What could be the link between such a field and another one?

How do people perceive such a phenomenon? What does it mean for both people and the phenomenon?

Find what you wonder about, and go research it.

Personal trick: think for yourself.

When I was studying for my master’s in political science, everyone went to research boring topics in international relations. As a result, they all struggled to find supervisors.

I did not research a boring topic in international relations. I went for a topic that was different and that I liked . As a result, I had four different professors ready to supervise me, when most students couldn’t even find one.

Look outside the box and stop caring about other people.

The best way to succeed is not to be better than anyone else, but to escape competition and rule over your own empire.

To summarize, here are all of the ways you can find a thesis topic:

- Take an assignment or a topic you have already written about and go further for your thesis.

- Take a previous thesis that you apply to another area (like I did with hotels and Airbnb).

- Find an interesting scientific paper and look at the “further research” section.

- Same thing as 3, but with a thesis from a student that wrote it the previous year.

- Be aware of what you are daydreaming about and see if it could apply to a thesis.

- Ask a researcher or professor about the unanswered questions in their domain of expertise. Don’t be obvious though, they shouldn’t know that this is because you want to write about it. Make it sound like it’s a simple conversation you are interested in.

- Read a bunch of papers about a topic and see which question has not been answered yet.

- Replicate: take a study, do it again, and see if it replicates (great for psychology).

Back to my first thesis.

As soon as my supervisor gave me the green light, I worked like a madman for the next few days.

The first step is to find a research question, aka, a problem to solve.

The problem should be as simple and as small as possible.

That’s what makes research difficult.

It’s easy to find big philosophical questions. It is less so to answer them.

Find the smallest problem possible for your question, or your theme will be too broad and you’ll have issues.

My question, as we said, was the survival of TV stations. I imagined they were going to die because of Netflix.

To make sure this problem was real, I had to read maybe 4 or 5 academic papers talking about this problem.

Once I had my proofs, I could come up with a research question.

Originally, I wrote:

“What is public TV stations’ strategy and response to counter new competitors in the TV landscape such as streaming companies?”

But my supervisor didn’t like it and told me to write this instead:

“What societal remit should PSBs (public service broadcasters) fulfill in an increasingly innovative and competitive media landscape?”

Now, I kid you not, I understood the question only weeks after I had gotten my final mark.

I had no clue what I was writing about until after I had finished writing it.

Instead of focusing on what TV stations did to survive, my supervisor wanted me to focus on what was public TV stations’ role in society.

Instead of asking “what do you do to survive”, it was asking “why do you even exist?”.

That guy was smart.

Next up, you’ll have to formulate hypotheses (some people work without them as I did).

Hypotheses are answers you believe you will find. They are based on the current literature.

When you write hypotheses, it will help you later on to structure your questionnaire into different parts so that you can answer your research question.

While I’m not a fan of hypotheses because it gives you more work, I do admit it eases your task.

Ask your supervisor.

For my second thesis, I did the exact same thing as for the first one, but with Airbnb’s and hotels instead of TV and Netflix.

I could have also chosen Uber and taxis, but that looked more like a done deal since they are the same service.

Hotels and Airbnb still differ to some extent.

The research question was:

How do high-end hotels use innovative strategies to overcome challenges and be more competitive in the hospitality business?

My third thesis was written in the context of a master’s in political science and EU studies.

“How does the EU Commission use data throughout the policymaking process?”

As you can see, the second and third research questions suck. They are badly phrased.

Since a thesis is built on a research question, a bad research question will give a bad thesis.

Don’t do what I did. Do it better. Do it simpler.

Getting your research question is the most difficult and critical step of any research work .

Once you got it, you just need to put your brain on “pause” for one or two months, and follow the plan.

Theses in the humanities and social sciences are not about thinking, but about writing what people tell you to write.

Once I got my RQ (research question), I could write my introduction: for the first thesis, I wrote about the challenges of TV, then of public TV, then about the specific challenges that these streaming newcomers represented for public TV, then I introduced my RQ.

Afterward, I presented an outline of how I researched the problem (technically, an intro is the last thing you write, so if you write it first, write in the past tense) and what research method I used.

And boom. I got my intro.

Don’t forget to add the “academic relevance” (why your research is academically interesting) and the “societal relevance” (how it can be applied to society).

Next up is the theoretical framework, also called “literature review”.

The literature review consists of reading a bunch of academic papers and make them speak to each other .

What you need to write is who says what about what and who agrees with who or contradicts who.

You’d think that writing a thesis is about writing, but it’s not.

It’s mainly about reading, then rephrasing whatever you read ( that’s one of the reasons why science stagnates , it has too many protocols and people are mostly concerned about what has been written instead of writing new stuff, but that’s a topic for another time).

So, reading then re-writing about 20-40 academic papers will do for your theoretical framework.

“40?! But Auré, how could you remember what you read?”

I didn’t, because I never read them entirely.

Here’s why.

First of all, time is important (remember that at the end of the article).

You’ll most likely die before you turn 80 because of the micro-plastic in your body and the low-quality air you breathe, so you want to maximize your time spent doing cool stuff, not writing papers no one gives a crap about.

When you read an academic paper, you want to focus on three parts only : the abstract, the introduction, and the conclusion/discussion.

The rest has not been written for you and you can ignore it.

Here’s what I did. I read the paper, then write a summary on a word document that I called “sources”.

This document was my database containing everything I had read.

If I didn’t remember where I had read a particular piece of information, all I had to do was a quick search in my database, and boom, I got what I wanted.

Sometimes, I’d just copy-past the abstract or the conclusion and add some keywords to find them easily in the database.

Since I often had +- 50 sources for my theoretical framework, this database was huge.

Once you established your database with the academic papers, you can start writing your TF (theoretical framework). Basically, you should define and explain all the concepts of your RQ.

For my first thesis, I explained the evolution of the TV landscape, then explained Netflix and all of the issues and strategic problems they caused for public TV (well, “explained” is a big word, you’re not allowed to explain, only to rewrite what other people had already written for you).

For my thesis on data and the EU Commission, I explained the entire policymaking process, defined “data”, and defined the few evidence-based policymaking strategies that I could find (research was lagging, I couldn’t find much).

Once you got your RQ, your introduction, and TF in order, congratulations!

You’ve done about 69% of the thesis.

I have no clue about theses in engineering or math, but theses in humanities and social sciences can choose between quantitative research (numbers) or qualitative research (people).

Needless to say, you should never go for quantitative research.

Here’s why:

1. You need a lot of respondents: every year, Facebook is assaulted with “hey, I’m writing a thesis for my master in gender studies, can you please fill up this short survey that will only take 5 minutes of your time? Thaanks!!”

Students often need to find 100-250 respondents for their results to be valid, and that’s when you realize that your 1000 friends on Facebook are completely useless when you can’t even get 20 people to fill up your survey.

A girl I know was smart. She paid a company whose job is to find respondents and got her results within 2 days.

Trust me, you don’t want to waste time and alienate your Facebook friends, nor do you want to pay to find people.

2. Analysis is hard: dunno which software you’ll have to use, but if you’re not in love with statistics, the analysis of your data will be difficult. You’ll have to perform regression analysis and who knows what else.

Let’s not even speak of results interpretation.

A girl I knew paid a guy in Bangladesh to analyze the results for her.

That only cost her 25€, but still.

-> quantitative research is dumb.

Qualitative research is much better (if you don’t know what it is, google it).

Whether you interview people (5-15) or do content analysis, you are the master of your time.

I did interviews for my three theses and never regretted it.

The only annoying thing was transcribing them, but it gets faster as you progress and gain skills.

In order to avoid interviews that are too long, don’t hesitate to interrupt your respondents if they give answers not relevant to your research.

The next part of your thesis is the “research method”.

I am not sure if what I’m about to tell you is correct. The three research method sections I wrote were done differently according to the wishes of my three supervisors.

Make sure to always follow the guidelines you are given since they are the requirements on what you will be judged on.

For the first thesis, I had to write a mini-theoretical framework about the research method, basically explaining what is qualitative research, in which context it is used, and why it was suitable for my work.

For the second thesis, I had to add a small part on how I had conducted my research.

For the third thesis, I had to scrap this research explanation structure to explain the steps I had taken instead.

I believe the third one is the best.

If you haven’t done so yet, now is the time to create the questionnaire you will use for your interviews.

The questionnaire should whether answer your hypotheses (or your theoretical framework) and overall, answer your RQ.

Count around 5-10 questions.

Be specific in what you’re asking, and don’t hesitate to elicit more answers if your respondents remain vague and elusive.

One easy way is to ask your supervisor if they don’t know anyone to interview. Usually, people in small industries know each other.

If they don’t, you’ll have to find respondents by yourself.

Contacting people by email is best.

If you’re a girl, you’ll have more success contacting men.

If you’re a guy, you’ll have to offer value in exchange for the time you’ll spend interviewing the person.

Start your email by briefly introducing yourself, then introduce your research project.

Ask if you can interview them, by Skype or in real life, whatever suits them best.

Don’t forget to add that you will share your results with them (they usually give you an interview because of that specifically).

If they answer they can’t give you an interview, ask them if they know anyone else.

Find below an email template I sent to people I wanted to interview for my first thesis,

“Dear Mister X,

My name is Auré.

I am a communication and media student at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. I am currently writing my thesis on the innovative strategies that public service broadcasters have implemented/are implementing in order to overcome the challenges of the media landscape.

In order to do so, I’m currently interviewing media innovation experts/managers from public service broadcasters.

Would it be possible for me to interview you?

I would be happy to come to Brussels to do so, or to do it over Skype, whatever suits you best.

I would of course be happy to share the results of my research with you, once it is completed.

Looking forward to hearing from you,

Best regards,

Auré”

Tip! Sending emails manually is a waste of time. There are many free email software out there you can use to send a high number of personalized emails easily (I use Zoho Campaigns, but use the one most adapted to your needs.)

Also, the Chrome extension Email Hunter will automatically capture any emails you run across on the web, and hunter.io enables you to find the email of an important person.

The second way to find respondents is to ask for names at the end of each interview . If you manage to find one respondent that gives you the name of one other respondent that gives you the name of etc, you will easily find all respondents you need.

As such, finding 3-4 respondents should be enough, as these people will likely help you find more people.

When I wrote my political science thesis, I only found 3 respondents myself, and the 9 others had been introduced to me by the 3 original respondents.

Don’t underestimate people’s willingness to help you.

We’re all humans and as humans, we are wired to enjoy helping others. It’s important to frame your work as you helping them rather than the opposite since you are the one tackling a problem they have.

No one has ever said no to free value.

Send as many emails as you can. I must have sent about 50 emails for my first thesis, more than 200 for my second thesis, and about 40 for my third thesis.

Writing a thesis is not hard. Like all things of value, it just takes time.

Side note: some industries have professionals that are sick and tired to answer students’ questions (marketing). Avoid well-known industries and choose a rare topic where experts are seldom interviewed.

Once you have all of your interviews and transcripts, you can do your analysis. First, I made a list of all the concepts I had asked questions. Then, I assigned a color to each of them.

Then, I’d read all the transcripts and highlight the corresponding concepts to the right color.

That made the organization easy when I had to write the results section.

When I wrote my first thesis, my supervisor told me to “make experts speak to each other”.

Basically, I had structured the section like I had structured the TF. Who says what, about what, and who contradicts who and why.

Afterward, I had written a conclusion and that was it.

For my second thesis, I was told to add a summary of the main findings. For my third thesis, my supervisor screwed me up (no, not in that way).

As I had finished a nice-looking analysis that had taken me two full weeks, she told me it wasn’t “enough”. My research also had to include content analysis.

So I went back to my computer, looked for content, and analyzed it. I subsequently presented the findings according to the hypotheses I had developed in the research question part.

The summary of the findings was included in the conclusion part.

The conclusion is the easiest part. If it doesn’t include the “summary of the main findings”, it usually includes the following: recommendations, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Recommendations are the part where you can freely express yourself without having to cite anyone else.

It’s you, as an expert, advising people that have the problems you researched.

Limitations are the problems with your thesis or the reasons why people that read it shouldn’t believe what you wrote.

The suggestions are what you think should be researched next.

To summarize, here’s how your thesis should look like:

1. Introduction part: introduce the topic with some background information and present your RQ, research method, possible hypotheses, academic and societal relevance.

2. Theoretical framework: the academic knowledge onto which your RQ is built.

3. Methodology: what methods you used, how (and why).

4. Your results: the part where you answer your RQ whether through your hypotheses or the structure of the TF.

5. Your conclusion: the part where you give your main findings, recommendations, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Congratulations! You know now how to write a thesis.

If you’re interested in having a look at how the final result looks like, you can download below the three theses that I’ve written.

Obviously, I had to take down names and personal details.

Here are some tips to make the process of writing a thesis easier.

Don’t Focus on the End-Goal – Focus on the Next Step Instead

First of all, take your eyes off the “final moment” when you’ll “be free”.

When Dilma Roussef was getting tortured, she’d think “one more minute, all it takes is one more minute” not to give up.

She could handle 20-25 minutes this way.

You should do the same: only look at what remains to do for the day.

You’ll reach the end before you know it.

Writing a thesis is like sex: you’ll go nuts if you always do the same thing at the same place at the same time.

Go write at the library, in a café, at your friends’ house, change rooms in your apartment and never write in the room where you sleep.

On Procrastination

Procrastination is what happens when doing something is more costly than not doing it.

When you enjoy what you do, you don’t procrastinate.

So make sure you find actual, meaningful reasons to write your thesis. Or choose a topic that’s fun to write.

Another way to look at it is to think about why you are studying/what are the perks you’ll get once you finish your studies.

It motivates and breaks procrastination.

“What?? But I already don’t have enough time, why would I load up on activities too?”

Technically, writing a thesis would take about one month if you wrote 6-8 hours/day every day, but no one does that nowadays because we’re all lazy and unfocused.

Let me tell you a story.

When I was a kid, I was doing music, sport, and theater. I’d perform best when I “didn’t have enough time” because I didn’t have time to procrastinate which forced me to create a schedule to be on time.

Hence, I was on time. Had I had a week to write something, I would have written it last minute because “I have the entire week, why bother now?”, but since I had many activities, I didn’t procrastinate.

People that procrastinate are those that have time to do so, hence, they end up wasting it.

If I told you that a bomb will explode in a month if you don’t finish on time, trust me, you will.

So the best way to finish on time is to give yourself just enough time to finish.

Load up on activities so that it stresses you out a bit before you run out of time to finish your work.

Sometimes, I get paid 10€/hour, sometimes, 15€/hour. That’s what my time is currently worth.

If I spend one hour on Instagram, I’ll “lose” 10€.

Once you realize that time is the scarcest commodity on earth, you stop wasting it.

You’ll End up Dying at Some Point…

This thought scares the hell out of me.

Not dying per se, but not having had time to do all I want to do.

It’s when I realized I wasn’t immortal that I started being productive and stopped losing time like I did when I was a teenager.

Contemplating your own death is a formidable motivational experience.

Use Parkison’s Law

Parkinson’s law says that an assignment will take you the time you allow yourself to take to complete it.

Should you decide to write your thesis within a month, you will.

This law though, is tricky. You may decide upon a period of time that will end up being bigger than needed.

For example, I had given myself until the 15th of May to finish the thesis but was done by the 22nd of April.

While I did use Parkinson’s law as a safety, I didn’t plan my work around it. I worked let’s say…reasonably.

I could have worked faster, but I didn’t want to because we were in lockdown and I had enough working 4-6 hours per day on my piece.

I used to be a last-minute guy until I realized that the ultimate last-minute moment is not the deadline: it’s death.

That was a life-changing realization. Also, as life got more and more complex, I realized I wanted to enjoy full brain capacity and that couldn’t be done if I had a list of things to do in the back of my mind.

If you are a last-minute person, then simply move back in time your deadline and make your own.

If you have a week to write something and think it will take two days, make sure you load up your week with activities two days from now.

Not only you’ll do more stuff, but you’ll have more time and will feel more productive, happy, and energetic.

Personally, the best periods of my life were the ones where I was working 10-14 hours a day.

But well, not everyone is crazy like that.

Photo by Vadim Bozhko on Unsplash

Subscribe to my monthly newsletter and I'll send you a list of the articles I wrote during the previous month + insights from the books I am reading + a short bullet list of savvy facts that will expand your mind. I keep the whole thing under three minutes.

How does that sound?

You Might Also Like

Self-development, Psychology, and Relationships Resources

Worldwide Butchery Directory: How and Where to Buy Cheap, Local, and Delicious Meat

Achieve Explosive Growth With These 7 Mindset Shifts

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE: Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE: If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2024 10:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Home > College of Social Sciences > Sociology and Interdisciplinary Social Sciences > Social Science Master's Theses

Master’s Theses and Graduate Research, Social Sciences

Theses/dissertations from 2004 2004.

www.to-get-her.org : a global cyber community for Taiwanese lesbians , Ping-Ying Chang

Theses/Dissertations from 2003 2003

The role of attachment in the social production of place in Pajaro Valley , Lori Burgman

The Nishimutas: the oral history of a Japanese/Spanish family, who lived in Oklahoma from 1917 , Juli Ann Ora Nishimuta

Muslim women speak their mind , Alexandra Maria da Silva Rubens

Theses/Dissertations from 2002 2002

Gay bars of Silicon Valley : a study of the decline of a social institution , William M. Coker

Legacies transforming memories into memorials , Bonnie Evans

Identity and political consciousness : community involvement of Mexican/Chicano youth , Etsuko Maruyama

Theses/Dissertations from 2001 2001

Homophonbia : a socio-cultural barrier to U.S female athletes in Olympic tryouts , Natalie L. Wells

Theses/Dissertations from 2000 2000

The Vietnamese elderly refugees' experience in America , Thanh Dac Tran

Theses/Dissertations from 1999 1999

The social construction of nature as the other and its human consequences , Shannon Abernathy

Telecommuting and its impact on business and personal relationships , Margaret G. Dreher

American family/work relationships : a case study of hospital nurses , Valora Glandt

Differential diagnosis of vertebral lytic lesions from an Ohlone cemetery site CA-SCL-038 , Victoria M. Wu

Theses/Dissertations from 1998 1998

Audre Lorde and poetic activism , Jennifer Blackman

Sons of alcoholic fathers : psychological and methodological considerations , Dennis Haines

Doing quality time : development of a feminist treatment program for women prisoners and their children , Ann Rebecca Pierce Harrison

Women's education and employment in Yugoslavia and California , Milina Jovanovic

Understanding aging and the aged through mainstream films , Linda Janet Proudfoot

Theses/Dissertations from 1997 1997

California Native American college students' experience : an ethnographic study , Linda Jane Christie

The Paleodemography of the Yukisma Site, CA-SCI-38 : a prehistoric cemetery of the South San Francisco Bay , Susan Morley

Beyond princess and squaw : Wilma Mankiller and the Cherokee gynocentric system , Maureen O'Dea Caragliano

The feminization of poverty : welfare to work research project , Kim S. Petersen

Theses/Dissertations from 1996 1996

Every woman her own midwife : a study of empowerment through wise woman health care , Kimberly A. Bick-Maurischat

Cultural diversity training : corporate stratification or cultural diversity , Judy Lynn Carrico

On the trail to the coast : a view from CA-MEN-2136 : the Zeni Site , Patricia A. Dunning

Walker's way : an oral history of Mark Walker , Elizabeth L. Lake

Marketing culture : an ethnographic case study of organizational culture in Silicon Valley , Kathleen MacKenzie

Korean women in the labor market , Jeamin Seung

Theses/Dissertations from 1995 1995

The public response to homelessness , Celine-Marie Pascale

Theses/Dissertations from 1994 1994

An archaeological survey of some major drainages within Henry W. Coe State Park, Santa Clara and Stanislaus Counties, California , Theodora Goodrich

Oral histories of black gay men and a black transgender person in the San Francisco Bay Area , Nina Schjelderup

Theses/Dissertations from 1993 1993

Four problems, one solution , Edward Emmanuel Corneille

Women, child-free and single , Margaret Hood Hynan

A reinterpretation of some Bay Area shellmound sites : a view from the mortuary complex from Ca-Ala-329, the Ryan Mound , Alan Leventhal

Institutional inequality : a case of educational tracking , Mary Etta Marshall

Chicanas in higher education : the road to success , Laura Alicia Salazar

U.S. policy toward Vietnam, 1960-1990 , An Ngoc Vu

Theses/Dissertations from 1992 1992

Strong hopes/shattered dreams : study of college females and perceived economic future , Heather M. David

The Vietnamese refugee experience : a fundamental redefinition of an ethnic identity , Laura A. Furcinitti

Prelude, interludes, and etudes : a study of the feminist/spiritual journey and designs for its nurture and practice , Maureen Hilliard

Not in his image : a study of male priesthood and catholic women , Marilyn Faye Crnich Nutter

The Formation of an ethnic identity : the life history of a Filipino/Native American , Mark Pasion

The Problem of black access to American higher education is connected to institutional underpreparation , Daryl M. Poe

San Jose State University students and domestic violence , Bette S. Ruch Rose

A leadership model for a woman in the U.S. presidency , Patricia Anne Stroup

Theses/Dissertations from 1991 1991

Archaic milling cultures of the southern San Francisco Bay region , Richard Thomas, Jr Fitzgerald

The use of terrorism as a means to create a homeland for stateless refugees in the Middle East , Chris D. Funk

A new method of skeletal aging using stages of sacral fusion as seen in the CA-Ala-329 burial population , Charlane Susan Gross

A breach of conduct : James A. Garfield and the court-martial of Fitz John Porter , William Warren Holland

Prehistoric native American adaptations along the central California coast of San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties , Mark Gerald Hylkema

The Culpability of James VI of Scotland, later James I of England, in the North Berwick witchcraft trials of 1590-91 , Margaret Carol Kintscher

Black Berets for Justice , Arturo Villarreal

Theses/Dissertations from 1990 1990

A history of the Ohlone Indians of Mission Santa Clara , Debra Kitsmiller Barth

Women reclaiming ourselves : the conflict between affiliation and individuation , Jana Bartley

The cycle of the feminine spirit : women, the earth, and athe return of the goddess , Wendy Denton

Sourcing Monterey banded chert, a cryptocrystalline hydrosilicate : with emphasis on its physical and thermal traits as applied to central California archaeology , Gary Alan Parsons

Theses/Dissertations from 1989 1989

Concerned women for America : the handmaidens of the new right , Teri Ann Bengiveno

Daughter of the landlord : life history of a Chinese immigrant , Joan M. Beck Coulson

Self-esteem of sexually abused adolescent girls in group home placement , Audrey Damon

The U.S. policy toward China during the Nixon presidency , Tuan Khac Truong

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Sociology and Interdisciplinary Social Sciences Website

- San José State University

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Sponsored by San José State University Library

San José State University Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library One Washington Square, San Jose, CA 95192-0028

Writing in Political Science

Like any discourse community, political scientists have their own rules and norms. Much of this description will not seem anathema to other forms of writing, but some guidelines are somewhat unique to the kind of writing that students in Politics classes need to do. Keep in mind that, even within the department, different professors have different expectations. Admittedly, most of the guidelines laid out below are taken from David Elliott of the Politics Department, though many of his suggestions, guidelines, and strategies would be acceptable to most, if not all, political scientists.

Developing a Thesis

Like in many disciplines, the thesis for a politics paper must both respond to and invite a debate. Ask the following questions of a thesis to see if it meets expectations:

Does it respond to the prompt?

Could someone disagree with the writer’s thesis?

Does the thesis draw on, and derive a generalization from, a broad array of facts?

While the second question is perhaps the most important, and like each of the other two, must be answered affirmatively for the thesis to pass muster, the third is essential as well. The argument must be based on the facts presented in class readings, but a litany of facts alone will not suffice. After doing the reading, the student must glean a one or two sentence generalization from those facts, creating a model in which each of those facts fit. This is arguably the most difficult part of writing the paper.

For example, consider the response to the prompt: “Describe the changes in U.S. foreign policy following September 11, 2001.” There are many appropriate theses that can respond to the prompt, including the following: “The morning of September 11th has been viewed by many as a great turning point for U.S. foreign policy, a day that shaped our guiding principles just as it clarified the type of challenges we faced. Yet in reality, these trends did not begin that fateful autumn morning when nearly three thousand Americans lost their lives—they merely accelerated. The United States had already come a long way from the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the world entered what Charles Krauthamer accurately termed the “Unipolar Moment,” a moment of unprecedented American power.”

After stating the thesis in the introductory section, some background is most likely required. While some professors may say that no background is desired, some context must be laid before an argument can be effectively developed. To continue with the example above, a discussion of Bush I and Clinton’s foreign policy is necessary before one can argue that Bush II’s foreign policy was an acceleration of, rather than a departure from, the policies that came before. Such context should follow the thesis-containing introduction and precede the argument.

The argument itself can be structured any variety of ways, but a solely chronological approach for time-sensitive arguments rarely suffices. Such an argument often traps students into producing a summary of, rather than an argument employing, relevant information from the readings. Arguments that are broken down into thematic chunks, while more difficult to effectively organize, are preferable.

It is important to differentiate the student’s ideas from those they are citing. Whenever someone else’s opinion is referenced, preface that opinion with “John Smith states” or “Jane Doe writes,” etc. For arguments made by the author that are stated in response to other facts or opinions, use phrases like “It is clear that…,” or “It seems more likely that…,” in order to make clear that the student is speaking without employing the first person. Also, be mindful of the professor’s expectations with regards to quotations—some prefer approximately 10% of the text to be quoted, others say that students may not include any quotations. It is essential that the student be aware of this, as well as the means by which quoting can be avoided in favor of paraphrasing.

Write the Introduction Last