- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

- Identify Empirical Articles

*Education: Identify Empirical Articles

- Google Scholar tips and instructions

- Newspaper Articles

- Video Tutorials

- EDUC 508 Library Session

- Statistics and Data

- Tests & Measurements

- Citation Managers

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Scan & Deliver and Interlibrary Loan

- Educational Leadership

- Global Executive Ed.D.

- Marriage & Family Therapy

- Organizational Change & Leadership

- Literacy Education

- Accreditation

- Journal Ranking Metrics

- Publishing Your Research

- Education and STEM Databases

How to Recognize Empirical Journal Articles

Definition of an empirical study: An empirical research article reports the results of a study that uses data derived from actual observation or experimentation. Empirical research articles are examples of primary research.

Parts of a standard empirical research article: (articles will not necessary use the exact terms listed below.)

- Abstract ... A paragraph length description of what the study includes.

- Introduction ...Includes a statement of the hypotheses for the research and a review of other research on the topic.

- Who are participants

- Design of the study

- What the participants did

- What measures were used

- Results ...Describes the outcomes of the measures of the study.

- Discussion ...Contains the interpretations and implications of the study.

- References ...Contains citation information on the material cited in the report. (also called bibliography or works cited)

Characteristics of an Empirical Article:

- Empirical articles will include charts, graphs, or statistical analysis.

- Empirical research articles are usually substantial, maybe from 8-30 pages long.

- There is always a bibliography found at the end of the article.

Type of publications that publish empirical studies:

- Empirical research articles are published in scholarly or academic journals

- These journals are also called “peer-reviewed,” or “refereed” publications.

Examples of such publications include:

- American Educational Research Journal

- Computers & Education

- Journal of Educational Psychology

Databases that contain empirical research: (selected list only)

- List of other useful databases by subject area

This page is adapted from Eric Karkhoff's Sociology Research Guide: Identify Empirical Articles page (Cal State Fullerton Pollak Library).

Sample Empirical Articles

Roschelle, J., Feng, M., Murphy, R. F., & Mason, C. A. (2016). Online Mathematics Homework Increases Student Achievement. AERA Open . ( L INK TO ARTICLE )

Lester, J., Yamanaka, A., & Struthers, B. (2016). Gender microaggressions and learning environments: The role of physical space in teaching pedagogy and communication. Community College Journal of Research and Practice , 40(11), 909-926. ( LINK TO ARTICLE )

- << Previous: Newspaper Articles

- Next: Workshops and Webinars >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 8:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/education

Penn State University Libraries

Empirical research in the social sciences and education.

- What is Empirical Research and How to Read It

- Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases

- Designing Empirical Research

- Ethics, Cultural Responsiveness, and Anti-Racism in Research

- Citing, Writing, and Presenting Your Work

Contact the Librarian at your campus for more help!

Introduction: What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools used in the present study

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

Reading and Evaluating Scholarly Materials

Reading research can be a challenge. However, the tutorials and videos below can help. They explain what scholarly articles look like, how to read them, and how to evaluate them:

- CRAAP Checklist A frequently-used checklist that helps you examine the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of an information source.

- IF I APPLY A newer model of evaluating sources which encourages you to think about your own biases as a reader, as well as concerns about the item you are reading.

- Credo Video: How to Read Scholarly Materials (4 min.)

- Credo Tutorial: How to Read Scholarly Materials

- Credo Tutorial: Evaluating Information

- Credo Video: Evaluating Statistics (4 min.)

- Next: Finding Empirical Research in Library Databases >>

- Last Updated: Feb 18, 2024 8:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

- Ask a Librarian

Research: Overview & Approaches

- Getting Started with Undergraduate Research

- Planning & Getting Started

- Building Your Knowledge Base

- Locating Sources

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Creating a Literature Review

- Productivity & Organizing Research

- Scholarly and Professional Relationships

Introduction to Empirical Research

Databases for finding empirical research, guided search, google scholar, examples of empirical research, sources and further reading.

- Interpretive Research

- Action-Based Research

- Creative & Experimental Approaches

Your Librarian

- Introductory Video This video covers what empirical research is, what kinds of questions and methods empirical researchers use, and some tips for finding empirical research articles in your discipline.

- Guided Search: Finding Empirical Research Articles This is a hands-on tutorial that will allow you to use your own search terms to find resources.

- Study on radiation transfer in human skin for cosmetics

- Long-Term Mobile Phone Use and the Risk of Vestibular Schwannoma: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study

- Emissions Impacts and Benefits of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Vehicle-to-Grid Services

- Review of design considerations and technological challenges for successful development and deployment of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

- Endocrine disrupters and human health: could oestrogenic chemicals in body care cosmetics adversely affect breast cancer incidence in women?

- << Previous: Scholarly and Professional Relationships

- Next: Interpretive Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/research_approaches

- University of La Verne

- Subject Guides

Identify Empirical Research Articles

- Interactive Tutorial

- Literature Matrix

- Guide to the Successful Thesis and Dissertation: A Handbook for Students and Faculty

- Practical Guide to the Qualitative Dissertation

- Guide to Writing Empirical Papers, Theses, and Dissertations

What is a Literature Review--YouTube

Literature Review Guides

- How to write a literature review

- The Literature Review:a few steps on conducting it Permission granted from Writing at the University of Toronto

- Six steps for writing a literature review This blog, written by Tanya Golash-Bozal PhD an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California at Merced, offers a very nice and simple advice on how to write a literature review from the point of view of an experience professional.

- The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Permission granted to use this guide.

- Writing Center University of North Carolina

- Literature Reviews Otago Polytechnic in New Zealand produced this guide and in my opinion, it is one of the best. NOTE: Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. However, all images and Otago Polytechnic videos are copyrighted.

What Are Empirical Articles?

As a student at the University of La Verne, faculty may instruct you to read and analyze empirical articles when writing a research paper, a senior or master's project, or a doctoral dissertation. How can you recognize an empirical article in an academic discipline? An empirical research article is an article which reports research based on actual observations or experiments. The research may use quantitative research methods, which generate numerical data and seek to establish causal relationships between two or more variables.(1) Empirical research articles may use qualitative research methods, which objectively and critically analyze behaviors, beliefs, feelings, or values with few or no numerical data available for analysis.(2)

How can I determine if I have found an empirical article?

When looking at an article or the abstract of an article, here are some guidelines to use to decide if an article is an empirical article.

- Is the article published in an academic, scholarly, or professional journal? Popular magazines such as Business Week or Newsweek do not publish empirical research articles; academic journals such as Business Communication Quarterly or Journal of Psychology may publish empirical articles. Some professional journals, such as JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association publish empirical research. Other professional journals, such as Coach & Athletic Director publish articles of professional interest, but they do not publish research articles.

- Does the abstract of the article mention a study, an observation, an analysis or a number of participants or subjects? Was data collected, a survey or questionnaire administered, an assessment or measurement used, an interview conducted? All of these terms indicate possible methodologies used in empirical research.

- Introduction -The introduction provides a very brief summary of the research.

- Methodology -The method section describes how the research was conducted, including who the participants were, the design of the study, what the participants did, and what measures were used.

- Results -The results section describes the outcomes of the measures of the study.

- Discussion -The discussion section contains the interpretations and implications of the study.

- Conclusion -

- References -A reference section contains information about the articles and books cited in the report and should be substantial.

- How long is the article? An empirical article is usually substantial; it is normally seven or more pages long.

When in doubt if an article is an empirical research article, share the article citation and abstract with your professor or a librarian so that we can help you become better at recognizing the differences between empirical research and other types of scholarly articles.

How can I search for empirical research articles using the electronic databases available through Wilson Library?

- A quick and somewhat superficial way to look for empirical research is to type your search terms into the database's search boxes, then type STUDY OR STUDIES in the final search box to look for studies on your topic area. Be certain to use the ability to limit your search to scholarly/professional journals if that is available on the database. Evaluate the results of your search using the guidelines above to determine if any of the articles are empirical research articles.

- In EbscoHost databases, such as Education Source , on the Advanced Search page you should see a PUBLICATION TYPE field; highlight the appropriate entry. Empirical research may not be the term used; look for a term that may be a synonym for empirical research. ERIC uses REPORTS-RESEARCH. Also find the field for INTENDED AUDIENCE and highlight RESEARCHER. PsycArticles and Psycinfo include a field for METHODOLOGY where you can highlight EMPIRICAL STUDY. National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts has a field for DOCUMENT TYPE; highlight STUDIES/RESEARCH REPORTS. Then evaluate the articles you find using the guidelines above to determine if an article is empirical.

- In ProQuest databases, such as ProQuest Psychology Journals , on the Advanced Search page look under MORE SEARCH OPTIONS and click on the pull down menu for DOCUMENT TYPE and highlight an appropriate type, such as REPORT or EVIDENCE BASED. Also look for the SOURCE TYPE field and highlight SCHOLARLY JOURNALS. Evaluate the search results using the guidelines to determine if an article is empirical.

- Pub Med Central , Sage Premier , Science Direct , Wiley Interscience , and Wiley Interscience Humanities and Social Sciences consist of scholarly and professional journals which publish primarily empirical articles. After conducting a subject search in these databases, evaluate the items you find by using the guidelines above for deciding if an article is empirical.

- "Quantitative research" A Dictionary of Nursing. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. University of La Verne. 25 August 2009

- "Qualitative analysis" A Dictionary of Public Health. Ed. John M. Last, Oxford University Press, 2007. Oxford Reference Online . Oxford University Press. University of La Verne. 25 August 2009

Empirical Articles:Tips on Database Searching

- Identifying Empirical Articles

- Next: Interactive Tutorial >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 4:49 PM

- URL: https://laverne.libguides.com/empirical-articles

- Belk Library

Psychology Research Guide

- What are Empirical Articles?

- Developing a Topic

- Finding Sources

- Searching Effectively

- Scholarly and Popular Sources

- Additional Help

Citation Resources

The most often used citation style for Psychology is:

DOIs and URLs

Follow these instructions from the American Psychological Association to correctly include DOIs and URLs in your list of references.

DOIs & URLs in APA Style

What are empirical articles?

In psychology, empirical research articles are peer-reviewed and report on new research that answers one or more specific questions. Empirical research is based on measurable observation and experimentation. When reading an empirical article, think about what research question is being asked or what experiment is being conducted.

How are they organized?

Empirical research articles in psychology typically follow APA style guidelines. They are organized into the following major sections:

- Abstract (An abstract provides a summary of the study.)

- Introduction (This section includes a literature review.)

- Method (How was the experiment or study conducted?)

- Results (What are the findings?)

- Discussion (What did the researchers conclude? What are the implications of the research?)

How should I read an empirical article?

Because empirical research articles follow a particular format, you can dip into the article at multiple points and move around in a non-linear way. First, think about why you're reading the article. Are you looking for specific information or trying to get research ideas? Are you reading it for a course or for your own knowledge? Next, read the abstract to get an overview of the study. Skim the first and last paragraphs of the introduction and results to deepen your understanding of the article as a whole. Read the methods section to understand how the study was organized and conducted. Review the charts, graphs, and statistics to understand the analyses. Skim the remaining pieces of the article, before going back and reading it more closely from the beginning to the end. Don't forget that the references can be a great source for additional empirical articles.

Don't confuse empirical articles with other types of articles.

Be careful not to confuse an empirical article with other types of articles that you might find when researching a psychology topic. Meta-analyis, systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and other types of literature reviews are not empirical articles. Instead, these articles are designed to analyze and summarize the existing literature on a topic. Similarly, don't confuse book reviews with empirical articles. These types of articles might be helpful in your research, but they are not empirical research articles.

- << Previous: Developing a Topic

- Next: Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 1:11 PM

- URL: https://elon.libguides.com/Psychology

- quicklinks Academic admin council Academic calendar Academic stds cte Admission Advising African studies Alumni engagement American studies Anthropology/sociology Arabic Arboretum Archives Arcus center Art Assessment committee Athletics Athletic training Biology Biology&chem center Black faculty&staff assoc Bookstore BrandK Business office Campus event calendar Campus safety Catalog Career & prof dev Health science Ctr for civic engagement Ctr for international pgrms Chemistry Chinese Classics College communication Community & global health Community council Complex systems studies Computer science Copyright Counseling Council of student reps Crisis response Critical ethnic studies Critical theory Development Dining services Directories Disability services Donor relations East Asian studies Economics and business Educational policies cte Educational quality assmt Engineering Environmental stewardship Environmental studies English Experiential education cte Facilities management Facilities reservations Faculty development cte Faculty executive cte Faculty grants Faculty personnel cte Fellowships & grants Festival playhouse Film & media studies Financial aid First year experience Fitness & wellness ctr French Gardens & growing spaces German Global crossroads Health center Jewish studies History Hornet hive Hornet HQ Hornet sports Human resources Inclusive excellence Index (student newspaper) Information services Institutional research Institutional review board Intercultural student life International & area studies International programs Intramural sports Japanese LandSea Learning commons Learning support Lgbtqai+ student resources Library Mail and copy center Math Math/physics center Microsoft Stream Microsoft Teams Moodle Movies (ch 22 online) Music OneDrive Outdoor programs Parents' resources Payroll Phi Beta Kappa Philharmonia Philosophy Physics Physical education Political science Pre-law advising Provost Psychology Public pol & urban affairs Recycling Registrar Religion Religious & spiritual life Research Guides (libguides) Residential life Safety (security) Sexual safety Shared passages program SharePoint online Sophomore experience Spanish Strategic plan Student accounts Student development Student activities Student organizations Study abroad Support staff Sustainability Teaching and learning cte Teaching commons Theatre arts Title IX Webmail Women, gender & sexuality Writing center

PSYC 301: Intro to Research Methods

- Advanced Search Strategies

- Tracking the Research Process

- Annotations

- Article Cards

- Organizing Sources

- Writing an Outline

- Citing Sources

Finding Empirical Research

Empirical research is published in books and in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals. PsycInfo offers straightforward ways to identify empirical research, unlike most other databases.

Finding Empirical Research in PsycInfo

- PsycInfo Choose "Advanced Search" Scroll down the page to "Methodology," and choose "Empirical Study" Type your keywords into the search boxes Choose other limits, such as publication date, if needed Click on the "Search" button

Slideshow showing how to find empirical research in APA PsycInfo

Video of finding empirical articles in psycinfo.

- Searching for Peer-Reviewed Empirical Articles (YouTube Video) Created by the APA

What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

Adapted from PennState University Libraries, Empirical Research in the Social Sciences and Education

Using PsycInfo

- Narrowing a Search (Canva Slideshow) Created by K Librarians

- Searching with the Thesaurus and Index Terms (YouTube Video) Created by the APA

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Advanced Search Strategies >>

- Last Updated: Apr 29, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kzoo.edu/psyc301

- Introduction & Help

- DSM-5 & Reference Books

- Books & E-Books

- Find Empirical Research Articles

- Search Tips

- Streaming Video

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

Finding Empirical Research Articles

- Introduction

- Methods or Methodology

- Results or Findings

The method for finding empirical research articles varies depending upon the database* being used.

1. The PsycARTICLES and PsycInfo databases (both from the APA) includes a Methodology filter that can be used to identify empirical studies. Look for the filter on the Advanced Search screen. To see a list and description of all of the of methodology filter options in PsycARTICLES and PsycInfo visit the APA Databases Methodology Field Values page .

2. When using databases that do not provide a methodology filter—including ProQuest Psychology Journals and Academic Search Complete—experiment with using keywords to retrieve articles on your topic that contain empirical research. For example:

- empirical research

- empirical study

- quantitative study

- qualitative study

- longitudinal study

- observation

- questionnaire

- methodology

- participants

Qualitative research can be challenging to find as these methodologies are not always well-indexed in the databases. Here are some suggested keywords for retrieving articles that include qualitative research.

- qualitative

- ethnograph*

- observation*

- "case study”

- "focus group"

- "phenomenological research"

- "conversation analysis"

*Recommended databases are listed on the Databases: Find Journal Articles page of this guide.

- << Previous: Databases: Find Journal Articles

- Next: Search Tips >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 9:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.bentley.edu/psychology

- Search Site

- Campus Directory

- Online Forms

- Odum Library

- Visitor Information

- About Valdosta

- VSU Administration

- Virtual Tour & Maps Take a sneak peek and plan your trip to our beautiful campus! Our virtual tour is mobile-friendly and offers GPS directions to all campus locations. See you soon!

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Meet Your Counselor

- Visit Our Campus

- Financial Aid & Scholarships

- Cost Calculator

- Search Degrees

- Online Programs

- How to Become a Blazer Blazers are one of a kind. They find hands-on opportunities to succeed in research, leadership, and excellence as early as freshman year. Think you have what it takes? Click here to get started.

- Academics Overview

- Academic Affairs

- Online Learning

- Colleges & Departments

- Research Opportunities

- Study Abroad

- Majors & Degrees A-Z You have what it takes to change the world, and your degree from VSU will get you there. Click here to compare more than 100 degrees, minors, endorsements & certificates.

- Student Affairs

- Campus Calendar

- Student Access Office

- Safety Resources

- University Housing

- Campus Recreation

- Health and Wellness

- Student Life Make the most of your V-State Experience by swimming with manatees, joining Greek life, catching a movie on the lawn, and more! Click here to meet all of our 200+ student organizations and activities.

- Booster Information

- V-State Club

- NCAA Compliance

- Statistics and Records

- Athletics Staff

- Blazer Athletics Winners of 7 national championships, VSU student athletes excel on the field and in the classroom. Discover the latest and breaking news for #BlazerNation, as well as schedules, rosters, and ticket purchases.

- Alumni Homepage

- Get Involved

- Update your information

- Alumni Events

- How to Give

- VSU Alumni Association

- Alumni Advantages

- Capital Campaign

- Make Your Gift Today At Valdosta State University, every gift counts. Your support enables scholarships, athletic excellence, facility upgrades, faculty improvements, and more. Plan your gift today!

Psychology Research: Finding Empirical Articles

- Finding Empirical Articles

- PubMed Guide This link opens in a new window

- What is Peer Review?

- Primary versus Secondary Resources

- Citation Styles and Plaigarism This link opens in a new window

- Using the Library This link opens in a new window

Search Tips

- Empirical Study in PsycINFO & PsycARTICLES

- Common Limiters

- Search Results

- PsycINFO PsycINFO, American Psychological Association's (APA) resource for abstracts of scholarly journal articles, book chapters, books, and dissertations, is the largest resource devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science, psychology, and mental health. Part of the Database Offerings in GALILEO, Georgia’s Virtual Library.

- PsycARTICLES Full-text collection of psychology articles in general psychology and specialized basic, applied, clinical, and theoretical research in psychology. Part of the Database Offerings in GALILEO, Georgia’s Virtual Library.

PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES are two APA databases that include a limiter for Empirical Study. When you limit your search to Empirical Study, all the search results will be empirical studies.

The APA defines an empirical study as a "Study based on facts, systematic observation, or experiment, rather than theory or general philosophical principle." An empirical research article reports on the results of research that uses data collected from observation or experiment. Empirical research articles are primary research articles.

Empirical Studies:

Type your search terms into the search boxes., on the advanced search screen, scroll down to methodology, and select empirical study., click search..

PsycINFO

PsycARTICLES

As you search in the database, you can select certain options, known as limiters, to make your search results fit with your research needs or the instructions in your assignment. Often, professors provide guidelines on the type of publication or when the article was published.

Common Limiters

Full text .

All your search results will be Full text.

Peer Reviewed

Search results will only include articles that are Peer Reviewed.

Search results published within a certain date range.

The EBSCOhost databases have several features to help manage your research results.

Create a free account in EBSCOhost to save item records or searches.

Go into any EBSCOhost database

Click on Sign In

Click on Create a new Account

Fill in the information

You do not have to use your BlazeVIEW username or password, this is an entirely separate system

Your password must be "strong" or the system will not accept it

Once you are logged into an EBSCOhost database, you will see a small yellow icon that reads "My"

Save item records in your folder.

When you find a book record, article record, etc. that you want to keep...

Click on the blue folder icon to add it to your folder

The blue folder icon is available on the search results page and in the item's record

Warning! If you add a record to your folder but you are not logged in, it will disappear when you close the browser. Be sure you are logged in!

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: PubMed Guide >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 3:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.valdosta.edu/psychologyresearch

- Virtual Tour and Maps

- Safety Information

- Ethics Hotline

- Accessibility

- Privacy Statement

- Site Feedback

- Clery Reporting

- Request Info

Identifying Empirical Research Articles

- Identifying Empirical Articles

- Searching for Empirical Research Articles

Where to find empirical research articles

Finding empirical research.

When searching for empirical research, it can be helpful to use terms that relate to the method used in empirical research in addition to keywords that describe your topic. For example:

- (generalized anxiety AND treatment*) AND (randomized clinical trial* OR clinical trial*)

You might also try using terms related to the type of instrument used:

- (generalized anxiety AND intervention*) AND (survey OR questionnaire)

You can also narrow your results to peer-review . Usually databases have a peer-review check box that you can select. To learn more about peer review, see our related guide:

- Understand Peer Review

Searching by Methodology

Some databases give you the option to do an advanced search by methodology, where you can choose "empirical study" as a type. Here's an example from PsycInfo:

Other filters includes things like document type, age group, population, language, and target audience. You can use these to narrow your search and get more relevant results.

Databasics: How to Filter by Methodology in ProQuest's PsycInfo + PsycArticles

Part of our Databasics YouTube series, this short video shows you how to limit by methodology in ProQuest's PsycInfo + PsycArticles database.

Attribution

Information in this guide adapted from Boston College Libraries' guide to " Finding Empirical Research "; Brandeis Library's " Finding Empirical Studies "; and CSUSM's " How do I know if a research article is empirical? "

- << Previous: Identifying Empirical Articles

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 8:24 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

Identify Empirical Research Articles

- What is empirical research?

- Finding empirical research in library databases

- Research design

- Need additional help?

Getting started

According to the APA , empirical research is defined as the following: "Study based on facts, systematic observation, or experiment, rather than theory or general philosophical principle." Empirical research articles are generally located in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals and often follow a specific layout known as IMRaD: 1) Introduction - This provides a theoretical framework and might discuss previous studies related to the topic at hand. 2) Methodology - This describes the analytical tools used, research process, and the populations included. 3) Results - Sometimes this is referred to as findings, and it typically includes statistical data. 4) Discussion - This can also be known as the conclusion to the study, this usually describes what was learned and how the results can impact future practices.

In addition to IMRaD, it's important to see a conclusion and references that can back up the author's claims.

Characteristics to look for

In addition to the IMRaD format mentioned above, empirical research articles contain several key characteristics for identification purposes:

- The length of empirical research is often substantial, usually eight to thirty pages long.

- You should see data of some kind, this includes graphs, charts, or some kind of statistical analysis.

- There is always a bibliography found at the end of the article.

Publications

Empirical research articles can be found in scholarly or academic journals. These types of journals are often referred to as "peer-reviewed" publications; this means qualified members of an academic discipline review and evaluate an academic paper's suitability in order to be published.

The CRAAP Checklist should be utilized to help you examine the currency, relevancy, authority, accuracy, and purpose of an information resource. This checklist was developed by California State University's Meriam Library .

This page has been adapted from the Sociology Research Guide: Identify Empirical Articles at Cal State Fullerton Pollak Library.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Finding empirical research in library databases >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:12 AM

- URL: https://paloaltou.libguides.com/empiricalresearch

Empirical Research in the Social Sciences and Education

What is empirical research.

- Finding Empirical Research

- Designing Empirical Research

- Ethics & Anti-Racism in Research

- Citing, Writing, and Presenting Your Work

Academic Services Librarian | Research, Education, & Engagement

Gratitude to Penn State

Thank you to librarians at Penn State for serving as the inspiration for this library guide

An empirical research article is a primary source where the authors reported on experiments or observations that they conducted. Their research includes their observed and measured data that they derived from an actual experiment rather than theory or belief.

How do you know if you are reading an empirical article? Ask yourself: "What did the authors actually do?" or "How could this study be re-created?"

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process or methodology used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (example: surveys, questionnaires, etc)

- You can readily describe what the authors actually did

Layout of Empirical Articles

Scholarly journals sometimes use a specific layout for empirical articles, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. There are four main components:

- Introduction : aka "literature review". This section summarizes what is known about the topic at the time of the article's publication. It brings the reader up-to-speed on the research and usually includes a theoretical framework

- Methodology : aka "research design". This section describes exactly how the study was done. It describes the population, research process, and analytical tools

- Results : aka "findings". This section describes what was learned in the study. It usually contains statistical data or substantial quotes from research participants

- Discussion : aka "conclusion" or "implications". This section explains why the study is important, and also describes the limitations of the study. While research results can influence professional practices and future studies, it's important for the researchers to clarify if specific aspects of the study should limit its use. For example, a study using undergraduate students at a small, western, private college can not be extrapolated to include all undergraduates.

- Next: Finding Empirical Research >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 3:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.stthomas.edu/empiricalresearcheducation

© 2023 University of St. Thomas, Minnesota

Experimental (Empirical) Research Articles

- Library vs. Google

- Background Reading

- Keyword Searching

- Evaluating Sources

- Citing Sources

- Professional Organizations

- Need more help?

How Can I Find Experimental (Empirical) Articles?

Many of the recommended databases in this research guide contain scholarly experimental articles (also known as empirical articles or research studies or primary research). Search in databases like:

- APA PsycInfo

- ScienceDirect

Because those databases are rich in scholarly experimental articles, any well-structured search that you enter will retrieve experimental/empirical articles. These searches, for example, will retrieve many experimental/empirical articles:

- caffeine AND "reaction time"

- aging AND ("cognitive function" OR "cognitive ability")

- "child development" AND play

Experimental (Empirical) Articles: How Will I Know One When I See One?

Scholarly experimental articles to conduct and publish an experiment, an author or team of authors designs an experiment, gathers data, then analyzes the data and discusses the results of the experiment. a published experiment or research study will therefore look very different from other types of articles (newspaper stories, magazine articles, essays, etc.) found in our library databases..

In fact, newspapers, magazines, and websites written by journalists report on psychology research all the time, summarizing published experiments in non-technical language for the general public. Although that kind of article can be interesting to read (and can even lead you to look up the original experiment published by the researchers themselves), to write a research paper about a psychology topic, you should, generally, use experimental articles written by researchers. The following guidelines will help you recognize an experimental article, written by the researchers themselves and published in a scholarly journal.

Structure of a Experimental Article Typically, an experimental article has the following sections:

- The author summarizes her article

- The author discusses the general background of her research topic; often, she will present a literature review, that is, summarize what other experts have written on this particular research topic

- The author describes the experiment she designed and conducted

- The author presents the data she gathered during her experiment

- The author offers ideas about the importance and implications of her research findings, and speculates on future directions that similar research might take

- The author gives a References list of sources she used in her paper

Look for articles structured in that way--they will be experimental/empirical articles.

Also, experimental/empirical articles are written in very formal, technical language (even the titles of the articles sound complicated!) and will usually contain numerical data presented in tables.

As noted above, when you search in a database like APA PsycInfo, it's really easy to find experimental/empirical articles, once you know what you're looking for. Just in case, though, here is a shortcut that might help:

First, do your keyword search, for example:

In the results screen, on the left-hand side, scroll down until you see "Methodology." You can use that menu to refine your search by limiting the articles to empirical studies only:

You can learn learn more about advanced search techniques in APA PsycInfo here .

- << Previous: Resources

- Next: Research Tips >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 3:14 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/counseling

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Content Index

Empirical research: Definition

Empirical research: origin, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, steps for conducting empirical research, empirical research methodology cycle, advantages of empirical research, disadvantages of empirical research, why is there a need for empirical research.

Empirical research is defined as any research where conclusions of the study is strictly drawn from concretely empirical evidence, and therefore “verifiable” evidence.

This empirical evidence can be gathered using quantitative market research and qualitative market research methods.

For example: A research is being conducted to find out if listening to happy music in the workplace while working may promote creativity? An experiment is conducted by using a music website survey on a set of audience who are exposed to happy music and another set who are not listening to music at all, and the subjects are then observed. The results derived from such a research will give empirical evidence if it does promote creativity or not.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You must have heard the quote” I will not believe it unless I see it”. This came from the ancient empiricists, a fundamental understanding that powered the emergence of medieval science during the renaissance period and laid the foundation of modern science, as we know it today. The word itself has its roots in greek. It is derived from the greek word empeirikos which means “experienced”.

In today’s world, the word empirical refers to collection of data using evidence that is collected through observation or experience or by using calibrated scientific instruments. All of the above origins have one thing in common which is dependence of observation and experiments to collect data and test them to come up with conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Causal Research

Types and methodologies of empirical research

Empirical research can be conducted and analysed using qualitative or quantitative methods.

- Quantitative research : Quantitative research methods are used to gather information through numerical data. It is used to quantify opinions, behaviors or other defined variables . These are predetermined and are in a more structured format. Some of the commonly used methods are survey, longitudinal studies, polls, etc

- Qualitative research: Qualitative research methods are used to gather non numerical data. It is used to find meanings, opinions, or the underlying reasons from its subjects. These methods are unstructured or semi structured. The sample size for such a research is usually small and it is a conversational type of method to provide more insight or in-depth information about the problem Some of the most popular forms of methods are focus groups, experiments, interviews, etc.

Data collected from these will need to be analysed. Empirical evidence can also be analysed either quantitatively and qualitatively. Using this, the researcher can answer empirical questions which have to be clearly defined and answerable with the findings he has got. The type of research design used will vary depending on the field in which it is going to be used. Many of them might choose to do a collective research involving quantitative and qualitative method to better answer questions which cannot be studied in a laboratory setting.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Quantitative research methods aid in analyzing the empirical evidence gathered. By using these a researcher can find out if his hypothesis is supported or not.

- Survey research: Survey research generally involves a large audience to collect a large amount of data. This is a quantitative method having a predetermined set of closed questions which are pretty easy to answer. Because of the simplicity of such a method, high responses are achieved. It is one of the most commonly used methods for all kinds of research in today’s world.

Previously, surveys were taken face to face only with maybe a recorder. However, with advancement in technology and for ease, new mediums such as emails , or social media have emerged.

For example: Depletion of energy resources is a growing concern and hence there is a need for awareness about renewable energy. According to recent studies, fossil fuels still account for around 80% of energy consumption in the United States. Even though there is a rise in the use of green energy every year, there are certain parameters because of which the general population is still not opting for green energy. In order to understand why, a survey can be conducted to gather opinions of the general population about green energy and the factors that influence their choice of switching to renewable energy. Such a survey can help institutions or governing bodies to promote appropriate awareness and incentive schemes to push the use of greener energy.

Learn more: Renewable Energy Survey Template Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

- Experimental research: In experimental research , an experiment is set up and a hypothesis is tested by creating a situation in which one of the variable is manipulated. This is also used to check cause and effect. It is tested to see what happens to the independent variable if the other one is removed or altered. The process for such a method is usually proposing a hypothesis, experimenting on it, analyzing the findings and reporting the findings to understand if it supports the theory or not.

For example: A particular product company is trying to find what is the reason for them to not be able to capture the market. So the organisation makes changes in each one of the processes like manufacturing, marketing, sales and operations. Through the experiment they understand that sales training directly impacts the market coverage for their product. If the person is trained well, then the product will have better coverage.

- Correlational research: Correlational research is used to find relation between two set of variables . Regression analysis is generally used to predict outcomes of such a method. It can be positive, negative or neutral correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

For example: Higher educated individuals will get higher paying jobs. This means higher education enables the individual to high paying job and less education will lead to lower paying jobs.

- Longitudinal study: Longitudinal study is used to understand the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing the subject over a period of time. Data collected from such a method can be qualitative or quantitative in nature.

For example: A research to find out benefits of exercise. The target is asked to exercise everyday for a particular period of time and the results show higher endurance, stamina, and muscle growth. This supports the fact that exercise benefits an individual body.

- Cross sectional: Cross sectional study is an observational type of method, in which a set of audience is observed at a given point in time. In this type, the set of people are chosen in a fashion which depicts similarity in all the variables except the one which is being researched. This type does not enable the researcher to establish a cause and effect relationship as it is not observed for a continuous time period. It is majorly used by healthcare sector or the retail industry.

For example: A medical study to find the prevalence of under-nutrition disorders in kids of a given population. This will involve looking at a wide range of parameters like age, ethnicity, location, incomes and social backgrounds. If a significant number of kids coming from poor families show under-nutrition disorders, the researcher can further investigate into it. Usually a cross sectional study is followed by a longitudinal study to find out the exact reason.

- Causal-Comparative research : This method is based on comparison. It is mainly used to find out cause-effect relationship between two variables or even multiple variables.

For example: A researcher measured the productivity of employees in a company which gave breaks to the employees during work and compared that to the employees of the company which did not give breaks at all.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Some research questions need to be analysed qualitatively, as quantitative methods are not applicable there. In many cases, in-depth information is needed or a researcher may need to observe a target audience behavior, hence the results needed are in a descriptive analysis form. Qualitative research results will be descriptive rather than predictive. It enables the researcher to build or support theories for future potential quantitative research. In such a situation qualitative research methods are used to derive a conclusion to support the theory or hypothesis being studied.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

- Case study: Case study method is used to find more information through carefully analyzing existing cases. It is very often used for business research or to gather empirical evidence for investigation purpose. It is a method to investigate a problem within its real life context through existing cases. The researcher has to carefully analyse making sure the parameter and variables in the existing case are the same as to the case that is being investigated. Using the findings from the case study, conclusions can be drawn regarding the topic that is being studied.

For example: A report mentioning the solution provided by a company to its client. The challenges they faced during initiation and deployment, the findings of the case and solutions they offered for the problems. Such case studies are used by most companies as it forms an empirical evidence for the company to promote in order to get more business.

- Observational method: Observational method is a process to observe and gather data from its target. Since it is a qualitative method it is time consuming and very personal. It can be said that observational research method is a part of ethnographic research which is also used to gather empirical evidence. This is usually a qualitative form of research, however in some cases it can be quantitative as well depending on what is being studied.

For example: setting up a research to observe a particular animal in the rain-forests of amazon. Such a research usually take a lot of time as observation has to be done for a set amount of time to study patterns or behavior of the subject. Another example used widely nowadays is to observe people shopping in a mall to figure out buying behavior of consumers.

- One-on-one interview: Such a method is purely qualitative and one of the most widely used. The reason being it enables a researcher get precise meaningful data if the right questions are asked. It is a conversational method where in-depth data can be gathered depending on where the conversation leads.

For example: A one-on-one interview with the finance minister to gather data on financial policies of the country and its implications on the public.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are used when a researcher wants to find answers to why, what and how questions. A small group is generally chosen for such a method and it is not necessary to interact with the group in person. A moderator is generally needed in case the group is being addressed in person. This is widely used by product companies to collect data about their brands and the product.

For example: A mobile phone manufacturer wanting to have a feedback on the dimensions of one of their models which is yet to be launched. Such studies help the company meet the demand of the customer and position their model appropriately in the market.

- Text analysis: Text analysis method is a little new compared to the other types. Such a method is used to analyse social life by going through images or words used by the individual. In today’s world, with social media playing a major part of everyone’s life, such a method enables the research to follow the pattern that relates to his study.

For example: A lot of companies ask for feedback from the customer in detail mentioning how satisfied are they with their customer support team. Such data enables the researcher to take appropriate decisions to make their support team better.

Sometimes a combination of the methods is also needed for some questions that cannot be answered using only one type of method especially when a researcher needs to gain a complete understanding of complex subject matter.

We recently published a blog that talks about examples of qualitative data in education ; why don’t you check it out for more ideas?

Since empirical research is based on observation and capturing experiences, it is important to plan the steps to conduct the experiment and how to analyse it. This will enable the researcher to resolve problems or obstacles which can occur during the experiment.

Step #1: Define the purpose of the research

This is the step where the researcher has to answer questions like what exactly do I want to find out? What is the problem statement? Are there any issues in terms of the availability of knowledge, data, time or resources. Will this research be more beneficial than what it will cost.

Before going ahead, a researcher has to clearly define his purpose for the research and set up a plan to carry out further tasks.

Step #2 : Supporting theories and relevant literature

The researcher needs to find out if there are theories which can be linked to his research problem . He has to figure out if any theory can help him support his findings. All kind of relevant literature will help the researcher to find if there are others who have researched this before, or what are the problems faced during this research. The researcher will also have to set up assumptions and also find out if there is any history regarding his research problem

Step #3: Creation of Hypothesis and measurement

Before beginning the actual research he needs to provide himself a working hypothesis or guess what will be the probable result. Researcher has to set up variables, decide the environment for the research and find out how can he relate between the variables.

Researcher will also need to define the units of measurements, tolerable degree for errors, and find out if the measurement chosen will be acceptable by others.

Step #4: Methodology, research design and data collection

In this step, the researcher has to define a strategy for conducting his research. He has to set up experiments to collect data which will enable him to propose the hypothesis. The researcher will decide whether he will need experimental or non experimental method for conducting the research. The type of research design will vary depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Last but not the least, the researcher will have to find out parameters that will affect the validity of the research design. Data collection will need to be done by choosing appropriate samples depending on the research question. To carry out the research, he can use one of the many sampling techniques. Once data collection is complete, researcher will have empirical data which needs to be analysed.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Step #5: Data Analysis and result

Data analysis can be done in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. Researcher will need to find out what qualitative method or quantitative method will be needed or will he need a combination of both. Depending on the unit of analysis of his data, he will know if his hypothesis is supported or rejected. Analyzing this data is the most important part to support his hypothesis.

Step #6: Conclusion

A report will need to be made with the findings of the research. The researcher can give the theories and literature that support his research. He can make suggestions or recommendations for further research on his topic.

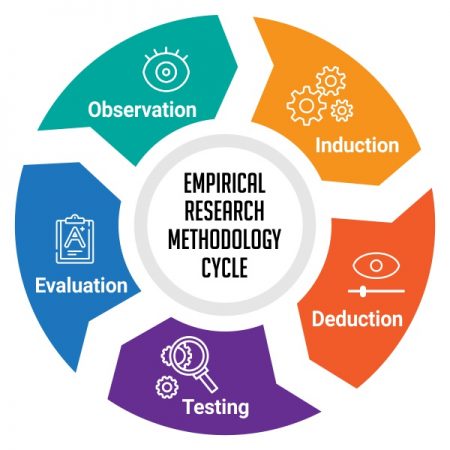

A.D. de Groot, a famous dutch psychologist and a chess expert conducted some of the most notable experiments using chess in the 1940’s. During his study, he came up with a cycle which is consistent and now widely used to conduct empirical research. It consists of 5 phases with each phase being as important as the next one. The empirical cycle captures the process of coming up with hypothesis about how certain subjects work or behave and then testing these hypothesis against empirical data in a systematic and rigorous approach. It can be said that it characterizes the deductive approach to science. Following is the empirical cycle.

- Observation: At this phase an idea is sparked for proposing a hypothesis. During this phase empirical data is gathered using observation. For example: a particular species of flower bloom in a different color only during a specific season.

- Induction: Inductive reasoning is then carried out to form a general conclusion from the data gathered through observation. For example: As stated above it is observed that the species of flower blooms in a different color during a specific season. A researcher may ask a question “does the temperature in the season cause the color change in the flower?” He can assume that is the case, however it is a mere conjecture and hence an experiment needs to be set up to support this hypothesis. So he tags a few set of flowers kept at a different temperature and observes if they still change the color?

- Deduction: This phase helps the researcher to deduce a conclusion out of his experiment. This has to be based on logic and rationality to come up with specific unbiased results.For example: In the experiment, if the tagged flowers in a different temperature environment do not change the color then it can be concluded that temperature plays a role in changing the color of the bloom.

- Testing: This phase involves the researcher to return to empirical methods to put his hypothesis to the test. The researcher now needs to make sense of his data and hence needs to use statistical analysis plans to determine the temperature and bloom color relationship. If the researcher finds out that most flowers bloom a different color when exposed to the certain temperature and the others do not when the temperature is different, he has found support to his hypothesis. Please note this not proof but just a support to his hypothesis.

- Evaluation: This phase is generally forgotten by most but is an important one to keep gaining knowledge. During this phase the researcher puts forth the data he has collected, the support argument and his conclusion. The researcher also states the limitations for the experiment and his hypothesis and suggests tips for others to pick it up and continue a more in-depth research for others in the future. LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

There is a reason why empirical research is one of the most widely used method. There are a few advantages associated with it. Following are a few of them.

- It is used to authenticate traditional research through various experiments and observations.

- This research methodology makes the research being conducted more competent and authentic.

- It enables a researcher understand the dynamic changes that can happen and change his strategy accordingly.

- The level of control in such a research is high so the researcher can control multiple variables.

- It plays a vital role in increasing internal validity .

Even though empirical research makes the research more competent and authentic, it does have a few disadvantages. Following are a few of them.

- Such a research needs patience as it can be very time consuming. The researcher has to collect data from multiple sources and the parameters involved are quite a few, which will lead to a time consuming research.

- Most of the time, a researcher will need to conduct research at different locations or in different environments, this can lead to an expensive affair.

- There are a few rules in which experiments can be performed and hence permissions are needed. Many a times, it is very difficult to get certain permissions to carry out different methods of this research.

- Collection of data can be a problem sometimes, as it has to be collected from a variety of sources through different methods.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

Empirical research is important in today’s world because most people believe in something only that they can see, hear or experience. It is used to validate multiple hypothesis and increase human knowledge and continue doing it to keep advancing in various fields.

For example: Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause. This way, they prove certain theories they had proposed for the specific drug. Such research is very important as sometimes it can lead to finding a cure for a disease that has existed for many years. It is useful in science and many other fields like history, social sciences, business, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

With the advancement in today’s world, empirical research has become critical and a norm in many fields to support their hypothesis and gain more knowledge. The methods mentioned above are very useful for carrying out such research. However, a number of new methods will keep coming up as the nature of new investigative questions keeps getting unique or changing.

Create a single source of real data with a built-for-insights platform. Store past data, add nuggets of insights, and import research data from various sources into a CRM for insights. Build on ever-growing research with a real-time dashboard in a unified research management platform to turn insights into knowledge.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Top 10 Employee Engagement Survey Tools

Top 20 Employee Engagement Software Solutions

May 3, 2024

15 Best Customer Experience Software of 2024

May 2, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Open access

- Published: 22 December 2022

A systematic review of high impact empirical studies in STEM education

- Yeping Li 1 ,

- Yu Xiao 1 ,

- Ke Wang 2 ,

- Nan Zhang 3 , 4 ,

- Yali Pang 5 ,

- Ruilin Wang 6 ,

- Chunxia Qi 7 ,

- Zhiqiang Yuan 8 ,

- Jianxing Xu 9 ,

- Sandra B. Nite 1 &

- Jon R. Star 10

International Journal of STEM Education volume 9 , Article number: 72 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

13 Citations

33 Altmetric

Metrics details

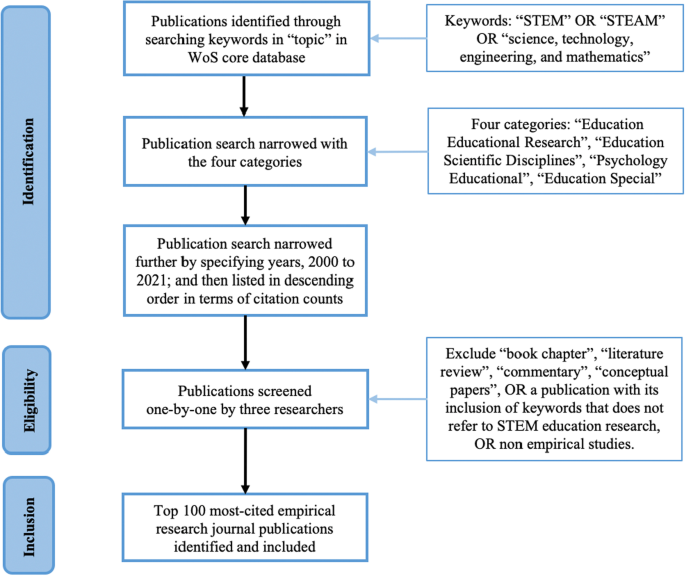

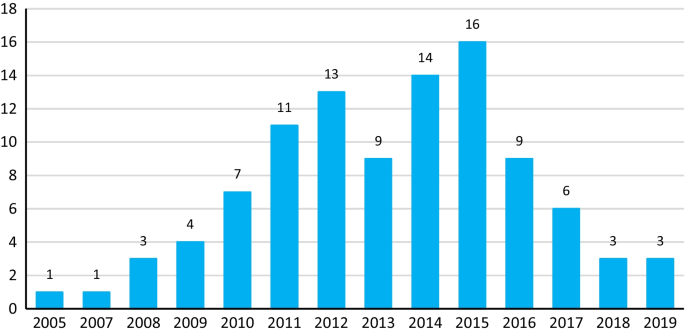

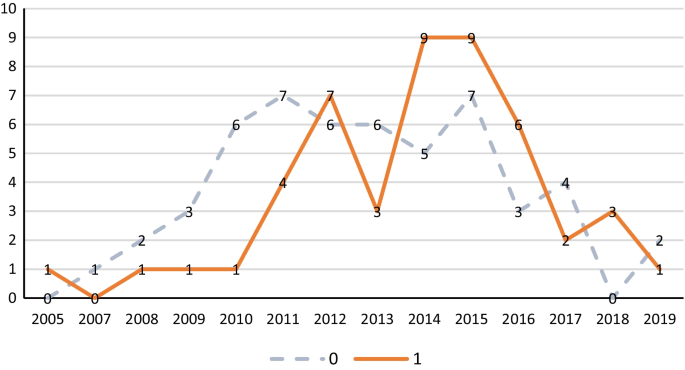

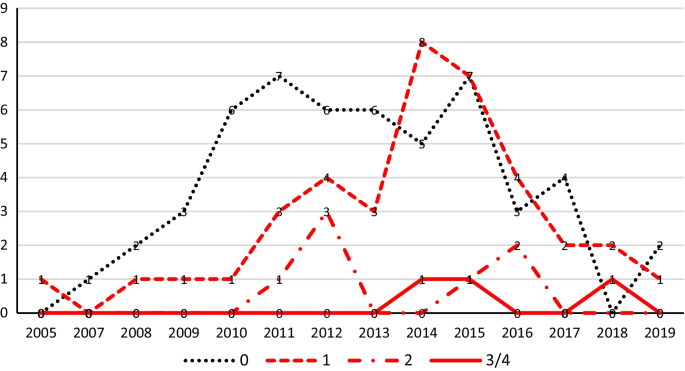

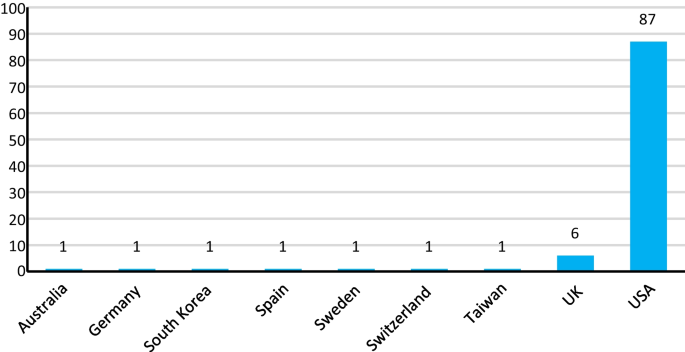

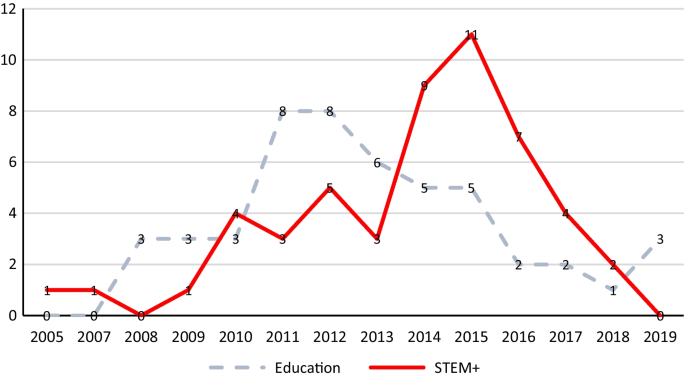

The formation of an academic field is evidenced by many factors, including the growth of relevant research articles and the increasing impact of highly cited publications. Building upon recent scoping reviews of journal publications in STEM education, this study aimed to provide a systematic review of high impact empirical studies in STEM education to gain insights into the development of STEM education research paradigms. Through a search of the Web of Science core database, we identified the top 100 most-cited empirical studies focusing on STEM education that were published in journals from 2000 to 2021 and examined them in terms of various aspects, including the journals where they were published, disciplinary content coverage, research topics and methods, and authorship’s nationality/region and profession. The results show that STEM education continues to gain more exposure and varied disciplinary content with an increasing number of high impact empirical studies published in journals in various STEM disciplines. High impact research articles were mainly authored by researchers in the West, especially the United States, and indicate possible “hot” topics within the broader field of STEM education. Our analysis also revealed the increased participation and contributions from researchers in diverse fields who are working to formulate research agendas in STEM education and the nature of STEM education scholarship.

Introduction

Two recent reviews of research publications, the first examining articles in the International Journal of STEM Education (IJSTEM) and the second looking at an expanded scope of 36 journals, examined how scholarship in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education has developed over the years (Li et al., 2019 , 2020a ). Although these two reviews differed in multiple ways (e.g., the number of journals covered, the time period of article publications, and article selection), they shared the common purpose of providing an overview of the status and trends in STEM education research. The selection of journal publications in these two reviews thus emphasized the coverage and inclusion of all relevant publications but did not consider publication impact. Given that the development of a vibrant field depends not only on the number of research outputs and its growth over the years but also the existence and influence of some high impact research articles, here we aimed to identify and examine those high impact research publications in STEM education in this review.

Learning from existing reviews of STEM education research

Existing reviews of STEM education have provided valuable insights about STEM education scholarship development over the years. In addition to the two reviews mentioned above, there are many other research reviews on different aspects of STEM education. For example, Chomphuphra et al. ( 2019 ) reviewed 56 journal articles published from 2007 to 2017 covering three popular topics: innovation for STEM learning, professional development, and gender gap and career in STEM. They identified and selected these journal articles through searching the Scopus database and two additional journals in STEM education that were not indexed in Scopus at that time. Several other reviews have been conducted and published with a focus on specific topics, such as the assessment of the learning assistant model (Barrasso & Spilios, 2021 ), STEM education in early childhood (Wan et al., 2021 ), and research on individuals' STEM identity (Simpson & Bouhafa, 2020 ). All of these reviews helped in summarizing and synthesizing what we can learn from research on different topics related to STEM education.

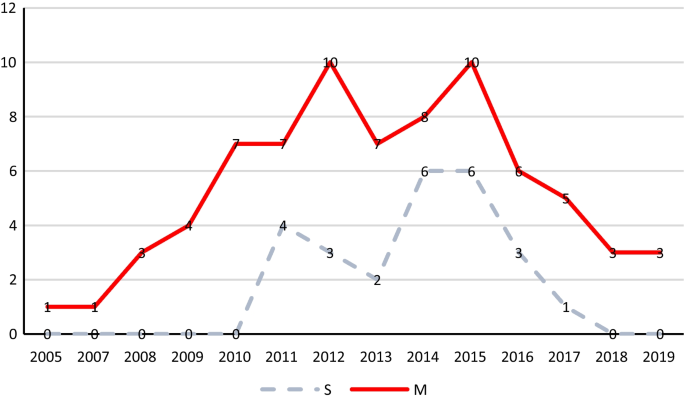

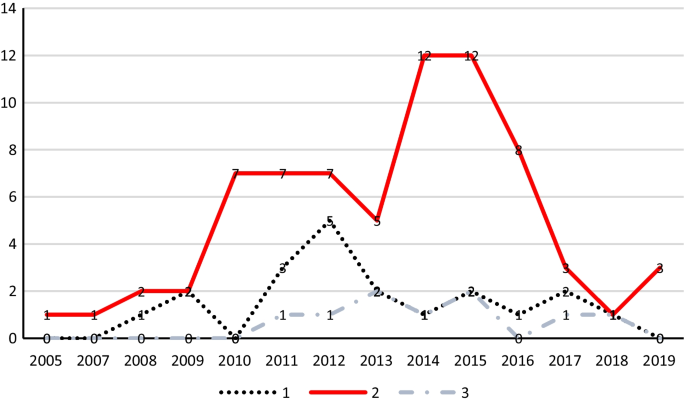

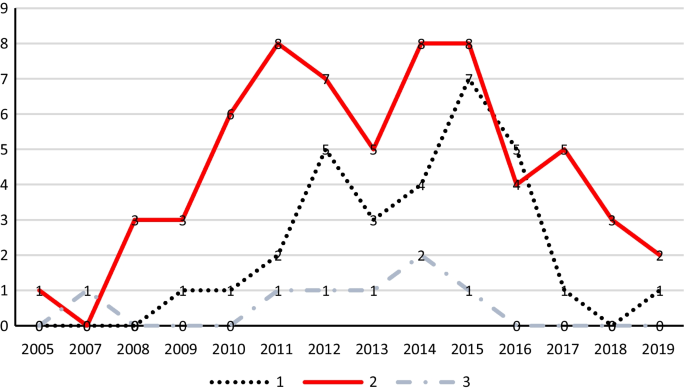

Given the on-going rapid expansion of interest in STEM education, the number of research reviews in STEM education research has also been growing rapidly over the years. For example, there were only one or two research reviews published yearly in IJSTEM just a few years ago (Li, 2019 ). However, the situation started to change quickly over the past several years (Li & Xiao, 2022 ). Table 1 provides a summary list of research reviews published in IJSTEM in 2020 and 2021. The journal published a total of five research reviews in 2020 (8%, out of 59 publications), which then increased to seven in 2021 (12%, out of 59 publications).

Taking a closer look at these research reviews, we noticed that three reviews were conducted with a broad perspective to examine research and trends in STEM education (Li et al., 2020a , 2020b ) or STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) education (Marin-Marin et al., 2021 ). Relatively large numbers of publications/projects were reviewed in these studies to provide a general overview of research development and trends. The other nine reviews focused on research on specific topics or aspects in STEM education. These results suggest that, with the availability of a rapidly accumulating number of studies in STEM education, researchers have started to go beyond general research trends to examine and summarize research development on specific topics. Moreover, across these 12 reviews, researchers used many different approaches to search multiple data sources (often with specified search terms) to identify and select articles, including journal publications, research reports, conference papers, or dissertations. It appears that researchers have been creative in developing and using specific approaches to select and review publications that are pertinent to their topics. At the same time, however, none of these reviews were designed and conducted to identify and review high impact research articles that had notable influences on the development of STEM education scholarship.

The importance of examining high impact empirical research publications in STEM education

STEM education differs from many other fields, as STEM itself is not a discipline. There are diverse perspectives about the disciplinarity of STEM and STEM education (e.g., Erduran, 2020 ; Li et al., 2020a ; Takeuchi et al., 2020 ; Tytler, 2020 ). The complexity and ambiguity in viewing and examining STEM and STEM education presents challenges as well as opportunities for researchers to explore and specify what and how they do in ways different from and/or connected with traditional education in the individual disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Although the field of STEM education is still in an early stage of its development, STEM education has experienced tremendous growth over the past decade. This field has evolved from traditional individual discipline-based education in STEM fields to multi- and interdisciplinary education in STEM. The development of STEM education has been supported by multiple factors, including research funding (Li et al., 2020b ) and the growth of research publications (Li et al., 2020a ). High impact publications play a very large role in the growth of the field, as they are read and cited frequently by others and serve to shape the development of scholarship in the field more than other publications.

Among high impact research publications, we can identify several different types of articles, including empirical studies, research reviews, and conceptual or theoretical papers. Research reviews and conceptual/theoretical papers are very valuable, as they synthesize existing research on a specific topic and/or provide new perspective(s) and direction(s), but they are typically not empirical studies. Review articles aim to provide a summary of the current state of the research in the field or on a particular topic, and they help readers to gain an overview about a topic, key issues and publications. Thus, they are more about what has been published in the literature about a topic and less about reporting new empirical evidence about a topic. Similarly, theoretical or conceptual papers tend to draw on existing research to advance theory or propose new perspectives. In contrast, empirical studies require the use and analysis of empirical data to provide empirical evidence. While reporting original research has been typical in empirical studies in education, these studies can also be secondary analyses of empirical data that test hypotheses not considered or addressed in previous studies. Empirical studies are generally published in academic, peer-reviewed journals and consist of distinct sections that reflect the stages in the research process. With the aim to gain insights about research development in STEM education, we thus decided to focus here on empirical studies in STEM education. Examining and reviewing high impact empirical research publications can help provide us a better understanding about emerging trends in STEM education in terms of research topics, methods, and possible directions in the future.

Considerations in identifying and selecting high impact empirical research publications

Publishing as a way of disseminating and sharing knowledge has many types of outlets, including journals, books, and conference proceedings. Different publishing outlets have different advantages in reaching out to readers. Researchers may search different data sources to identify and select publications to review, as indicated in Table 1 . At the same time, journal publications are commonly chosen and viewed as one of the most important outlets valued by the research community for knowledge dissemination and exchange. Specifically, there are two important advantages in terms of evaluating the quality and impact of journal publications over other formats. First, journal publications typically go through a rigorous peer-review process to ensure the quality of manuscripts for publication acceptance based on certain criteria. In educational research, some common criteria being used include “Standards for Reporting on Empirical Social Science Research in AERA Publications” (AERA, 2006 ), “Standards for Reporting on Humanities-Oriented Research in AERA Publications” (AERA, 2009 ), and “Scientific Research in Education” (NRC, 2002 ). Although the peer-review process is also employed in assessing and selecting proposals or papers for publication acceptance in other formats such as books and conference proceedings, the peer-review process employed by journals (esp. those reputable and top journals in a field) tends to be more rigorous and selective than other publication formats. Second, the impact of journals and their publications has frequently been evaluated by peers and different indexing services for inclusion, such as Clarivate’s Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Elsevier’s Scopus. The citation information collected and evaluated by indexing services provides another important measure about the quality and impact of selected journals and their publications. Based on these considerations, we decided to select and review those journal publications that can be identified as having high citations to gain an overview of their impact on the research development of STEM education.