Research Topics & Ideas: Sociology

50 Topic Ideas To Kickstart Your Research Project

If you’re just starting out exploring sociology-related topics for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll help kickstart your research by providing a hearty list of research ideas , including real-world examples from recent sociological studies.

PS – This is just the start…

We know it’s exciting to run through a list of research topics, but please keep in mind that this list is just a starting point . These topic ideas provided here are intentionally broad and generic , so keep in mind that you will need to develop them further. Nevertheless, they should inspire some ideas for your project.

To develop a suitable research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan to fill that gap. If this sounds foreign to you, check out our free research topic webinar that explores how to find and refine a high-quality research topic, from scratch. Alternatively, consider our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Sociology-Related Research Topics

- Analyzing the social impact of income inequality on urban gentrification.

- Investigating the effects of social media on family dynamics in the digital age.

- The role of cultural factors in shaping dietary habits among different ethnic groups.

- Analyzing the impact of globalization on indigenous communities.

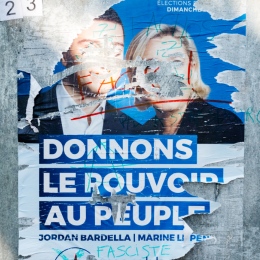

- Investigating the sociological factors behind the rise of populist politics in Europe.

- The effect of neighborhood environment on adolescent development and behavior.

- Analyzing the social implications of artificial intelligence on workforce dynamics.

- Investigating the impact of urbanization on traditional social structures.

- The role of religion in shaping social attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights.

- Analyzing the sociological aspects of mental health stigma in the workplace.

- Investigating the impact of migration on family structures in immigrant communities.

- The effect of economic recessions on social class mobility.

- Analyzing the role of social networks in the spread of disinformation.

- Investigating the societal response to climate change and environmental crises.

- The role of media representation in shaping public perceptions of crime.

- Analyzing the sociocultural factors influencing consumer behavior.

- Investigating the social dynamics of multigenerational households.

- The impact of educational policies on social inequality.

- Analyzing the social determinants of health disparities in urban areas.

- Investigating the effects of urban green spaces on community well-being.

- The role of social movements in shaping public policy.

- Analyzing the impact of social welfare systems on poverty alleviation.

- Investigating the sociological aspects of aging populations in developed countries.

- The role of community engagement in local governance.

- Analyzing the social effects of mass surveillance technologies.

Sociology Research Ideas (Continued)

- Investigating the impact of gentrification on small businesses and local economies.

- The role of cultural festivals in fostering community cohesion.

- Analyzing the societal impacts of long-term unemployment.

- Investigating the role of education in cultural integration processes.

- The impact of social media on youth identity and self-expression.

- Analyzing the sociological factors influencing drug abuse and addiction.

- Investigating the role of urban planning in promoting social integration.

- The impact of tourism on local communities and cultural preservation.

- Analyzing the social dynamics of protest movements and civil unrest.

- Investigating the role of language in cultural identity and social cohesion.

- The impact of international trade policies on local labor markets.

- Analyzing the role of sports in promoting social inclusion and community development.

- Investigating the impact of housing policies on homelessness.

- The role of public transport systems in shaping urban social life.

- Analyzing the social consequences of technological disruption in traditional industries.

- Investigating the sociological implications of telecommuting and remote work trends.

- The impact of social policies on gender equality and women’s rights.

- Analyzing the role of social entrepreneurship in addressing societal challenges.

- Investigating the effects of urban renewal projects on community identity.

- The role of public art in urban regeneration and social commentary.

- Analyzing the impact of cultural diversity on education systems.

- Investigating the sociological factors driving political apathy among young adults.

- The role of community-based organizations in addressing urban poverty.

- Analyzing the social impacts of large-scale sporting events on host cities.

- Investigating the sociological dimensions of food insecurity in affluent societies.

Recent Studies & Publications: Sociology

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a research topic, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual sociology-related studies to see how this all comes together in practice.

Below, we’ve included a selection of recent studies to help refine your thinking. These are actual studies, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Social system learning process (Subekti et al., 2022)

- Sociography: Writing Differently (Kilby & Gilloch, 2022)

- The Future of ‘Digital Research’ (Cipolla, 2022).

- A sociological approach of literature in Leo N. Tolstoy’s short story God Sees the Truth, But Waits (Larasati & Irmawati, 2022)

- Teaching methods of sociology research and social work to students at Vietnam Trade Union University (Huu, 2022)

- Ideology and the New Social Movements (Scott, 2023)

- The sociological craft through the lens of theatre (Holgersson, 2022).

- An Essay on Sociological Thinking, Sociological Thought and the Relationship of a Sociologist (Sönmez & Sucu, 2022)

- How Can Theories Represent Social Phenomena? (Fuhse, 2022)

- Hyperscanning and the Future of Neurosociology (TenHouten et al., 2022)

- Sociology of Wisdom: The Present and Perspectives (Jijyan et al., 2022). Collective Memory (Halbwachs & Coser, 2022)

- Sociology as a scientific discipline: the post-positivist conception of J. Alexander and P. Kolomi (Vorona, 2022)

- Murder by Usury and Organised Denial: A critical realist perspective on the liberating paradigm shift from psychopathic dominance towards human civilisation (Priels, 2022)

- Analysis of Corruption Justice In The Perspective of Legal Sociology (Hayfa & Kansil, 2023)

- Contributions to the Study of Sociology of Education: Classical Authors (Quentin & Sophie, 2022)

- Inequality without Groups: Contemporary Theories of Categories, Intersectional Typicality, and the Disaggregation of Difference (Monk, 2022)

As you can see, these research topics are a lot more focused than the generic topic ideas we presented earlier. So, for you to develop a high-quality research topic, you’ll need to get specific and laser-focused on a specific context with specific variables of interest. In the video below, we explore some other important things you’ll need to consider when crafting your research topic.

Get 1-On-1 Help

If you’re still unsure about how to find a quality research topic, check out our Research Topic Kickstarter service, which is the perfect starting point for developing a unique, well-justified research topic.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Political Sociology

Introduction.

- Data Sources

- Classic Works

- State Formation

- Welfare State

- Globalization and the State

- Nationalism and the Nation-State

- Development and the Developmental State

- War, Violence, and Revolutionary Social Change

- Civil Society

- Elections, Political Participation, and Public Opinion

- Race, Ethnicity, and Politics

- Gender and Politics

- Class Inequalities and Politics

- Culture and Politics

- Contemporary Controversies and New Directions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Charles Tilly

- Citizenship

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Conservatism

- Daniel Bell

- Law and Society

- Marxist Sociology

- Nationalism

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Public Opinion

- S.M. Lipset

- Social Change

- Social Movements

- Social Psychology

- Welfare States

- World-Systems Analysis

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Economic Globalization

- Global Inequalities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Political Sociology by Jeff Manza LAST REVIEWED: 27 July 2011 LAST MODIFIED: 27 July 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0001

Political sociology is the study of power and the relationship between societies, states, and political conflict. It is a broad subfield that straddles political science and sociology, with “macro” and “micro” components. The macrofocus has centered on questions about nation-states, political institutions and their development, and the sources of social and political change (especially those involving large-scale social movements and other forms of collective action). Here, researchers have asked “big” questions about how and why political institutions take the form that they do, and how and when they undergo significant change. The micro orientation, by contrast, examines how social identities and groups influence individual political behavior, such as voting, attitudes, and political participation. While both the macro- and micro-areas of political sociology overlap with political science, the distinctive focus of political sociologists is less on the internal workings or mechanics of the political system and more on the underlying social forces that shape the political system. Political sociology can trace its origins to the writings of Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber, among others, but it only emerged as a separate subfield within sociology after World War II. Many of the landmark works of the 1950s and 1960s centered on microquestions about the impact of class, religion, race/ethnicity, or education on individual and group-based political behavior. Beginning in the 1970s, political sociologists increasingly turned toward macrotopics, such as understanding the sources and consequences of revolutions, the role of political institutions in shaping political outcomes, and large-scale comparative-historical studies of state development. Today both micro- and macroscholarship can be found in political sociology.

For beginning students, several introductory political sociology textbooks provide a more basic entrée to the field. While covering much of the same ground, these also vary somewhat in topics emphasized or covered. The most comprehensive introductory work, rare for giving significant attention to both micro- and macrotraditions in political sociology while still providing a discussion of theoretical classics, is that of Orum and Dale 2009 . Neuman 2008 provides a comprehensive introduction to the field in terms of topics treated (although giving relatively little attention to microquestions). Nash 2007 focuses on globalization, gender dynamics, and political change. Lachmann (2010 ) provides a historically grounded introduction to the rise of states and the relationship between states and domestic power structures.

Lachmann, Richard. 2010. States and power . Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2010.

A wide-ranging survey of the rise of modern states across five continents, with a special focus on war-making and taxation that provides a key introduction to the macro-tradition in political sociology.

Nash, Kate. 2007. Contemporary political sociology: Globalization, politics, and power . Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Focuses on gender issues and globalization factors, as well as examining how culture impacts politics, and how cultural analysis might be brought into political sociology.

Neuman, W. Lawrence. 2008. Power, state, and society: An introduction to political sociology . Waveland.

Covers a wider range of topics than do other textbooks and introductions to political sociology, although it gives little attention to microquestions. Includes a chapter on the political sociology of policymaking.

Orum, Anthony, and John G. Dale. 2009. Political sociology: Power and participation in the modern world . 5th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

A strong single volume introduction to the field that covers classical theoretical writings in political sociology, along with both the macro and micro sides of the field. A chapter on urban power describes political sociological work on local contexts. Two chapters on social movements provide an excellent introduction to the field.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Civil Rights

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social History

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Networks

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Stratification

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

- Utility Menu

Bart Bonikowski Associate Professor of Sociology Resident Faculty, The Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies

bonikowski_-_head_shot_-_full_size.jpg

Introduction to Political Sociology

Semester: , offered: .

Politics is a struggle for power—power over access to and the distribution of resources, over personal and collective status, and over the ability to define legitimate categories of thought. While politics can be found in all domains of social life, the ultimate site of political contestation is the state, which holds the legitimate monopoly on physical and symbolic violence. Hence, much political sociology is concerned with the relationship between the state and society: how the modern state came to exist, how it came to be viewed as legitimate, what factors shaped processes of democratization, how cleavages based on class, race, and gender affect democratic representation, how liberal democracies structure their welfare state policies, how states create and manage markets, and how social movements strive to effect political change by making claims on state actors. This course will offer an overview of these varied substantive topics, while exposing students to the analytical power of a sociological approach to politics.

Link:

- Utility Menu

Department of Sociology

- Political and Historical Sociology

This cluster explores interdisciplinary scholarship in socio-economic, cultural and political history. The focus is on the nature, dynamics and interacting influences of culture, politics and institutions, explored at all levels of analysis. Research is guided by the recurring theoretical problems of causality, origins, continuity and change. Research topics include the divergent developmental paths of capitalism and socialism; slavery, colonialism and their post-colonial consequences; the historical constructions of race-ethnicity and anti-racist strategies; the relationships between collective identities, political discourse, and political change; political and economic consequences of global and regional integration; and the origins, development and diffusion of major politico-cultural values and institutions such as freedom, liberalism and democracy. The department¹s Workshop in History, Culture and Sociology provides a forum for the presentation of scholarship in this cluster from across the university and region.

The department sponsors the Workshop in History, Culture, and Society .

Affiliated Graduate Students

News related to Political & Historical Sociology

Ya-Wen Lei discusses her book in new video series, Fairbank Center-On Books and in The Wire China.

... Read more about Ya-Wen Lei discusses her book in new video series, Fairbank Center-On Books and in The Wire China.

Jocelyn Viterna's research featured in CNN Report

Professor Skocpol's historical badge collection featured in Gazette.

Theda Skocpol shares her badge collection with the Gazette . She first became familiar with the badges, and the groups behind them, in the late 1990s, when she was researching her award-winning book Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life .

... Read more about Professor Skocpol's historical badge collection featured in Gazette.

The long reach of racism in the u.s..

Why America can’t escape its racist roots

- Comparative Sociology and Social Change

- Crime and Punishment

- Economic Sociology and Organizations

- Education and Society

- Gender and Family

- Health and Population

- Race, Ethnicity and Immigration

- Urban Poverty and the City

Associated Faculty

- Jason Beckfield

- Paul Y. Chang

- Frank Dobbin

- Ira Jackson

- Liz McKenna

- Christopher Muller

- Orlando Patterson

- Stephanie Ternullo

- Adaner Usmani

- Jocelyn Viterna

- Tyler Woods

Related Publications

Patterson, Orlando . 2019. The Confounding Island: Institutions, Culture and Mis-development in Post-Colonial Jamaica . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Beckfield, Jason . 2018. Political Sociology and the People's Health (Small Books Big Ideas in Population Health) . edited by Nancy Krieger . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, Harris H., and Paul Y. Chang . 2018. “ The Impact of Delinquent Friendship Networks and Neighborhood Quality on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation in South Korea ”. Social Forces 97 (1):347-376.

Research in Political Sociology

- Recent Chapters

All books in this series (13 titles)

Recent chapters in this series (18 titles)

- A Naturalistic Observation of Mask Wearing Behavior in a Southeastern United States Town during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- A Reflection on Biodiversity in a Time of Covid-19 Pandemic: A Foundation of Environmental Sustainability

- Birdsong and the Diseased Gaia in the Anthropocene: An Ecofeminist Reading of Terry Tempest Williams' Memoirs – Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place and When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice

- Care Ethics in the Time of COVID-19: Are We Our Brother's Keepers? Some Insights from the Efforts of “Food for Chennai,” India

- Corporate Mining, Sustainable Development, and Human Rights of the Indigenous People in the Philippines: Implications for Building Resiliency to the Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic *

- COVID-19 in Chile: Personal and Political Outcomes

- Gender Relations and Dynamics of Internal Committee: Case Studies from Private and Public Institutions in South India

- Gender-Based Violence and COVID-19: Legislative and Judicial Measures for Protection and Support of the Women Victims of Domestic Violence in Sri Lanka

- Genealogies of Sustainable Development? Life Stories of Frugal, Inventive, and Creative Women

- Impact of COVID-19 on Employment in Himachal Pradesh – A Case Study

- Invisible Frontline Warriors of COVID-19: An Intersectional Feminist Study of ASHA Workers in India

- Iranian Dating Sites in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study on Muslim Married Women

- Selected Aspects of Discrimination against the Elderly in the Polish Health Care System

- Social Determinants of Health Disparities and COVID-19 in Black Belt Communities in Alabama: Geospatial Analyses

- Systemic Inequality, Sustainability and COVID-19 in US Prisons: A Sociological Exploration of Women's Prison Gardens in Pandemic Times

- Coalitions that Clash: California's Climate Leadership and the Perpetuation of Environmental Inequality

- Creative Disappointment: How Movements for Democracy: Spawn Movements for Even More Democracy *

- Crises of Social Reproduction among Women of Color: The State and Local Politics of Inequality within Neoliberal Capitalism

- Professor Barbara Wejnert

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Research subject Political Sociology

Political sociology can be understood as the study of how “society” engages in political processes. Another way of approaching this relationship is to consider how political power is contested by, distributed among, and impacting different social groups.

Topics pertaining to political sociology include power, nation-states and empires, the state as a political actor, political participation, revolutions, social movements, and globalization. A central, overarching theme is the interplay between macro-sociological processes and micro-sociological actors.

Related research subject

On this page

Researchers

Vanessa Lynn Barker

Professor of Sociology

Elida Izani Binti Ibrahim

Phd Student

Zeth Isaksson

Zeynep Melis Kirgil

PhD student

Daniel Ritter

Senior Lecturer, Docent

Weiqian Xia

Research projects

The overarching aim of the project is to further knowledge about the role of the welfare state for climate policy attitudes. Are people more willing to accept decarbonization policies if they are compensated by a generous welfare state?

This research project explains the dramatic trends in European elections in the 21st century. The project’s primary hypothesis is that these trends result not from attitudinal changes amongst Europeans, but from variation in what they see as the most important political issues of the day–issue salience.

Research on the historical origins of gender equality in political representation is scarce. This project applies insights about the historical origins of gender inequality on labor markets on the case of political representation.

How have policies influenced changes in everyday life one year after the coronavirus outbreak? Cross-national analysis of parents’ experiences with employment, work and care

The purpose of this research project is to conduct a comparative study of radical right-wing parties in Europe.The general aim is to identify factors that explain why such parties have succeeded in some countries, while largely failing in others.

The overall aim of the project is to increase knowledge about the importance of social class relations for social cohesion and political divides in modern welfare states. A central focus is how social networks and existing political institutions together shape contemporary sociopolitical cleavages, from a country-comparative perspective.

In this project we study how student support and tuition fee systems in different countries are associated with student welfare, and whether this has consequences for higher education participation.

Investigating forms of collective action and their influence on environmental policies.

The project "Why Do Working Class Voters Support the Populist Radical Right? A Mixed-Methods Study of a Changing Political Landscape in Sweden" explores the relationship between class politics and support for the populist radical right.

Courses and programmes

Departments and centres.

The research activities takes place at the Department of Sociology.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Political Science Research

iResearchNet

Political Sociology

Political sociology is a major subfield on the border of sociology and political science, combining explanatory factors and research interests of both disciplines. It developed from the work of the early founders of social science to include areas of inquiry that tackle the salient social and political processes of the twentieth century and the contemporary world. We discuss important theoretical and empirical advancements and the subfield’s continuous preoccupation with the interrelationships of ‘politics’ and ‘society’, political and social changes, and with issues of power, domination, and exploitation.

Introduction

Marx and class domination, capitalism, and revolution, weber and political authority, bureaucracy, and the modern state, the durkheimian tradition and pluralism, the mid- and late twentieth-century period, the contemporary period.

Political sociology bridges the fields of sociology and political science by addressing issues of power and authority with a focus on state/civil society relations. Political sociology differs from political science in that it includes and often focuses on the civil society side of the equation rather than placing an emphasis on the state and/or political elites. Core areas of research include state formation and change, forms of political rule, major social policies, political institutions and challenges to them (including reform-oriented and revolutionary social movements), political parties and the social bases of political attitudes and behaviors, class/power relations, and the political consequences of globalization. The field includes distinct major approaches, yet theoretical combination and synthesis is common. Many early and contemporary studies utilize comparative historical analysis, especially with regard to critical junctures and historical processes and developments, whereas current work has become methodologically more eclectic. Contemporary political issues and events, regimes in power, and cases relating to the United States and Europe tend to garner the most scholarly attention, though there is a steadily growing body of theory and empirical work beyond the core capitalist democracies.

We consider four somewhat distinct periods in the development of political sociology, while prioritizing the most recent period: (1) We trace political sociology’s inspiration in the mid-nineteenth century to the earlier philosophers who considered the state and social life, but note that it was not until the founding fathers of nineteenth-century social science began thinking of society and the state as distinct entities and analyzing the relationships between them, that political sociology was born; (2) The post–World War II period, which shifted the subfield’s focus to the prerequisites of democracy and voting patterns; (3) The late twentieth-century period, which saw political sociologists move toward a focus on state building and political change, using Marxist theories of capitalism and class as well as other theories; and (4) The contemporary period, which is characterized by a proliferation of topics relevant to politics such as globalization, race, gender, and culture. (Sections Historical Developments through Midand Late Twentieth-Century Period are largely abridged, paraphrased, and enhanced versions of the previous survey by E. Allardt in this publication. See Allardt (2001) for full references to these sections. Additionally, for broad works on political sociology, see Alford and Friedland, 1985; Janoski et al., 2005; Amenta et al., 2012.)

Historical Development of Political Sociology

The foundations of social sciences emerged in a context of epochal social and political transformations, including the development and unfolding of capitalist social systems and the modern state. These developments encouraged conceptualizations of the state and society as separate entities, making it possible to investigate their interrelations. Relying on earlier works on social life and politics by philosophers, historians, and legal theorists, sociology’s three founding fathers made important contributions to political sociology’s beginnings. Karl Marx challenged the idea that power concentrates solely in political offices and officeholders. Instead he focused on politics as emerging primarily from class conflict, just as the bourgeoisie and industrial working classes were becoming the principal social groups. He also emphasized the role of ideology in sustaining the powers that be. Max Weber responded to and critiqued Marx and added important analyses of authority, status categories, and social institutions (especially bureaucracy). Sociology’s third founding father, Emile Durkheim, did not have an explicitly political focus, yet his emphasis on social order, integration, and solidarity had important implications for analyses of society and politics. Others more directly associated with the emergence of political sociology include: Talcott Parsons, who was inspired by Durkheim, Vilfredo Pareto, and Gaetano Mosca, who made independent contributions by emphasizing the role of elites for social and political change (along with others who continued this concern, including Robert Michels, C. Wright Mills, G. William Domhoff, Alexis de Tocqueville, and Seymour Martin Lipset).

Marx was among the first to articulate an empirical political sociology, marking out historical materialism in his systematic general insistence on exploring the relationships between the mode of economic production and social property relations with state/political forms, social and political struggles, and consciousness, with a particular focus on capitalism and classes in capitalist societies. His was a firmly historical sociology, which emphasized human agency and historical contingency as being conditioned and constrained by structural features and processes, and consequently critically analytical of the character and dynamics of capitalism. Broadly, Marx argued that the division of societies into social classes is based on objective relations of domination and that the dominant class’ exploitation of dominated classes is central to many historically specific forms of economic production. In such situations, the state or central political power and authority generally maintains and reproduces the basic social systems, which are riven by the potentially explosive or revolutionary social antagonisms rooted in these relations of domination and exploitation. Despite varying and often contradictory interpretations of his extensive body of work, Marx’s framework is often seen as the primary source of political economy and class approaches.

Like Marx himself, several later Marxists had wide-ranging influence both in and outside of academia. Vladimir Lenin developed theories on revolutionary politics and change, imperialism, the state, and liberal democracy. Leon Trotsky’s work on the Russian Revolution is a milestone in scholarship on revolution and historical sociology, prioritizing mass political participation and the study of the political processes of the masses themselves in relation to political leaders and parties. He emphasized the historical unfolding of revolutionary struggles and the necessity of analyzing the structural conditioning, if not constitution, of such intense sociopolitical struggles in forms of economic development (hence the theory of combined and uneven development). Antonio Gramsci offered influential theories on hegemony, political conflict, and the distinction and relation between political society and civil society in capitalist democracies. Central to his work was the notion that bourgeois cultural values and institutions, (both those centered in the state and those that were not), help create situations of consented coercion, with continuous state formation acting to balance the interests of the ‘fundamental group and those of the subordinate groups’. These analyses demonstrate that political sociology includes politically-oriented analyses, and also that important historical actors are included as political sociologists.

Max Weber wrote many of his works in response to Marx, with considerable overlap and agreement as well as divergence. Also largely historical, Weber traced the “elective affinity” of capitalist development and Protestantism in Europe, highlighting their functional compatibility and the eventual coconstitutional development of economic forms with culture and ideology. Additionally, Weber’s work examined ideal typical forms of legitimate authority and domination, bases of individual and group social action, and perhaps most important, he offered a general theory of rationalization (i.e., instrumental rationality) as embodied in bureaucratic organizational forms and the wide-ranging bureaucratization of modern life – the latter process tied into the dynamic development of capitalism and the modern state. In contrast to Marx, who saw the modern state more or less in relation to powerful class interests, class struggles, and capital accumulation processes, Weber emphasized the modern state as an autonomous source of interests and power. Cultural scholars at times refer to Weber’s wide-ranging body of work and theory, yet his work is more often than not associated with and taken as a basis for statist approaches.

Many theorists have been influenced by Weber, including those who furthered the study of elites and bureaucracy. Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca were pioneers in the sociological study of elites. Pareto identified the governing elite, who ruled with a psychological preference for either force or fraud. He argued that the elite class is maintained by the circulation of especially apt nonelites into the ruling group. Mosca takes a more sociological approach to the study of elites by emphasizing structural and organizational factors in the maintenance of elite classes, such as their superior organization and their control of resources.

Robert Michels’ seminal work criticized party bureaucracies in modern states and addressed central themes such as the role of elites, leftist political movements, bureaucratization, and the gap between democratic theory and practice. Michels developed a thesis called “the iron law of oligarchy”, which argues that organization necessarily leads to oligarchy. In Michel’s words: “it is organization which gives birth to the dominion of the elected over the electors, of the mandataries over the mandators, of the delegates over the delegators. Who says ‘organization’, says ‘oligarchy’” (1911/1968).

While Marx and Weber were clearly social and political theorists, Emile Durkheim is less often noted as a scholar of politics. However, his concern with social order, integration, and solidarity had clear implications for analyses of politics and society (Allardt, 2001). Durkheim attempted to overhaul the traditional concept of an increasing division of labor and social cohesion, in his insistence that modern societies can achieve a degree of cohesion surpassing their predecessors. He is often associated with those who emphasize culture, values and norms, and functionalism, with a linkage to later pluralist theorists that would come to dominate American social science.

The English translations of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America and The Old Regime and the Revolution are standards in political sociology. In the former, he specified the conditions for pluralism and institutional democracy, arguing that in industrially developed societies, social cleavages, and group/strata competition are necessary for consensus. Plural democracy is created and sustained by voluntary associations and active, relatively autonomous local communities. Thus, de Tocqueville emphasized the role of social conflicts and cleavages in developing consensus in democracies (Allardt, 2001).

The Institutionalization of Political Sociology after World War II

In the postwar period, the prerequisites of democracy and the role of parliamentary elections as the major mechanism for establishing and securing democratic rule became important foci. After the war there were great hopes attached to the possibility of building a better world with the aid of social science and research. As political science became more preoccupied with constitutional problems and modes of state management and sociology focused on social structure and social group behavior, political sociology moved between the disciplines (Allardt, 2001).

Political sociologists undertook large-scale studies of voting behavior and developed fruitful theories and hypotheses, such as Lazarsfeld’s argument that cross-pressures lead to political passivity (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944; Allardt, 2001). Seymour Martin Lipset had already published important works, and his Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics (1960) became a leading text of the period and helped give birth to institutional political sociology. Lipset’s and Rokkan’s Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives (1967) would later apply Parson’s A-G-I-L scheme (an analytic model designed to explain stability by considering Adaption, Goal Attainment, Integration, and Latency) in an attempt to combine structural and institutional approaches to understand the social bases of politics and the effects of politics on social structures (Allardt, 2001).

It was in this context that the pluralist conceptualizations of social and political action arose in earnest. In this vein, Smelser emphasized the state, collective behavior, and culturalvalue change (1967); Easton focused on the political system (1965); and Gurr on political violence and relative deprivation (1970). Broadly, these studies tended to equate the political system with the state and considered individuals with distinct preferences and values to be the constitutive units of both organizations and societies (Alford and Friedland, 1985: p. 35).

While the study of electoral behavior and voting patterns became a specialized area of inquiry, political sociologists’ basic interest was in studying the conditions for democracy, regime type and breakdowns, state and nation building, modernization, and other processes of social and political change (Allardt, 2001).

Political sociologists, for example, have explored many aspects of democracy: the conditions for democracy in labor unions (Lipset et al., 1956), in the local community (Robert Dahl, 1961) and the conditions of conflict regulation in industrial society (Dahrendorf, 1959). Others focused on the breakdown of democracy and the rise and appeal of Fascism and Communism, such as Raymond Aron in The Opium of Intellectuals (1955) and William Kornhauser in The Politics of Mass Society (1959). C. Wright Mills The Power Elite (1990) examined the relationships and shared interests among US corporate, political, and military leaders; leading to the concentration of economic power and cultural influence in the hands of the relatively few and interchangeability of positions within these three institutions.

With the maturity and incorporation of electoral studies and studies of some other original political sociology topics in the 1960s and 1970s along with new critiques from the left, these topics disappeared from political sociology’s central agenda. Increasingly, the focus became large-scale patterns of societal change. S.N. Eisenstadt (1963/1993) examined the formation and fall of empires, Rokkan studied the historical formation of European centers and peripheries (Rokkan and Urwin, 1983) and Juan Linz analyzed the breakdown of democratic regimes (Linz and Stepan, 1978) (Allardt, 2001).

Yet the period was perhaps most substantially marked by the outpouring of Marxist or Marxist-oriented scholarship on class politics and major sociopolitical transformations as well as the structural contours and dynamics of global capitalism (Allardt, 2001). Unfortunately, a full review of this literature is not possible, here, and thus several important examples must suffice. Barrington Moore wrote an often-quoted major work The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (1966), using indepth historical case studies to show how the varying class coalitions that emerged during agricultural commercialization impacted the forms of ‘political modernization’ in the modern world. E.P. Thompson (1963) explored workers’ life experiences and cultural outlooks in his historical analysis of the formation and consciousness of the British working-class. Jeffery Paige (1975) explored how specific agrarian organization and class relations encouraged certain forms of political action and revolution. Maurice Zeitlin (1984) and Zeitlin and Ratcliff (1988) analyzed the development of the Chilean state in light of struggles between segments of the dominant class and the interactions between international and domestic forces. G. William Domhoff (1967, 1990) combined class and institutional analysis to build his class dominance theory and explore how the power elite in the US (owners and top managers of major corporations) actually dominate policymaking. Immanuel Wallerstein (1974/2011) focused on international divisions of labor in his study of the origins and structural contours of the world capitalist system. On the borders of political sociology were the critical sociologists in the Frankfurt School of dialectical sociology and the Dependency theorists who pointed out how underdeveloped countries were enmeshed in a world dominated by international capitalism.

Interest in master patterns of change and in state and nation building proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s. Theda Skocpol (1979) helped reintroduce the state as the originator of social outcomes and Charles Tilly (1992) stressed a complicated web of warfare, fiscal policy, bureaucratization, and state-making as forming national developments. Goran Therborn’s (1995) studies of European states emphasized that national development is multidimensional and may be reversible.

Developments from this period onward made the borders of political sociology more permeable. For instance, studies considering the roles of ethnicity, ethnic groups, and ethnic identities in the formation of nations straddle the line between political sociology and race/ethnic studies. Studies in the political sociology tradition often emphasize the macro-level role that ethnicity and ethnic identities may play in the formation of nations and political development (Rokkan and Urwin, 1983).

Over the last few decades, scholars have expanded political sociology’s theoretical and empirical scope. Established approaches have persisted and developed, and have been challenged or supplemented by theories of rational choice (Tsebelis, 1990; Chong, 2000), culture (B. Anderson, 1983/2006; Bourdieu, 1984/2013; Inglehart, 1997), race (Gilroy, 1991; Winant, 1994), gender (Orloff, 1993; Paxton et al., 2007), and several institutionalisms (Amenta and Ramsey, 2010; Thelen, 1999). Oftentimes, these approaches influenced political sociology after migrating from political science, economics, or the humanities. While ‘new’ theoretical perspectives and explanatory models may initially seem to displace established approaches, their overly bold early claims may recede as scholars implicitly or explicitly adopt theoretical synthesis or accommodation, or bolster their approaches by accounting for or appropriating salient factors or processes emphasized by others. So, while Marxist scholarship which flourished in the 1970s lost much of its early fervor by the mid-1980s, political sociology has remained theoretically eclectic.

Scholars are also more likely to explore historical or contemporary empirical phenomena of diverse geographical settings, a trend bolstered by the growing numbers and diversity of academics and research institutions worldwide, e.g., political sociologists regularly examine social and political processes in cases outside of Europe and the United States. Further, not only do emergent and changing social and political circumstances tend to impact what is being explored (by providing cases) but also salient political trends and/or the configuration of political power holders may impact the explanations given.

Moreover, recent scholarship has benefited from methodological advances. While quantitative methods may predominate in the social sciences, the flourishing of work in comparative and historical methodologies (Abrams, 1982; Ragin, 1987; Mahoney and Rueschemeyer, 2003) has found fertile ground in political sociological research, both through within-case analyses and cross-case comparisons.

In this context, the following section not so much adjudicates theories but instead introduces empirical studies covering a range of research questions asked by scholars from different theoretical traditions. It is not an exhaustive review of recent literature; rather, it provides a brief look at some vital political sociology research areas, such as states and society, revolution, globalization, culture, immigration, macro-social theory, and also notes other substantive themes.

Scholarship on state formation continued in the decades after World War II, exploring processes of the formation of early modern European states, the global diffusion (uneven and varied) of their general political models, variations in regime type, welfare state formation, developmental states, and so on. While states differ along multiple axes, including over time and place, it is commonly held that national states originally emerged in early modern Europe (along with capitalism) and have thus received due diligence to the degree that it was from this temporal and geographical source that they exerted extensive gravitational pull on world history, so that state formation processes in later centuries – often accompanying Western imperialism – were reproduced across the globe as approximations of a single model. More generally, scholars explore modern states’ formation with varying emphases on processes of capitalist development, war, international relations, resource extraction, class or elite coalitions, and culture.

Political sociologists emphasize the ways in which social factors impact state formation processes, considering capitalism and class as well as culture and institutions. Seminal Marxist explanations focus on rural classes and capitalist agricultural development to explain the origins of liberal democracies and Communist or Fascist dictatorships in major states (Moore, 1966); or investigate the centralized states of European Absolutism, its regional variation, and its role in the transition from feudalism to capitalism (Anderson, 1974/2013). Tilly (1992) adopts a bellecist approach to explore the formation of national states in an environment of incessant military-strategic competition, and system-wide convergence on that model in Europe. The interplay of war making, state making, and capitalist consolidation, Tilly argues, proceeds in a dialectic of the increasing concentration and accumulation of capital and coercion, pressed by war making and preparation, fiscal extraction, administrative expansion, and the making of social alliances. Ertman (1997) prioritizes local political institutional path dependency and the timing of the onset of sustained geopolitical-military competition, to account for the diverse range of regime types and state infrastructures across Europe in the eighteenth century, whereas Gorski (2003) shifts to culture to unravel the emergence of strong centralized states in Germany and the Netherlands, arguing that Calvinism and its emphasis on public order and discipline heightened state capacities and functions, regarding education, crime and punishment, and military effectiveness.

While extending insights from European cases to other regions, scholars often avoid transplanting some universal European trajectory and note the impact of colonialism, Western geopolitical dominance, and how being ‘late’ developers may impact state formation in the Third World. Heydemann (2000) notes that interstate war between Middle Eastern and North African states was rare in the twentieth century, but that extensive war preparation and militarized government produced deep political consequences, with variation in state formation linked to discrete modes of resource extraction. Centeno (2003) likewise describes interstate warfare as rare in post-independence Latin America, and argues that this absence corresponds to the weakness of Latin American states and the national elites’ unwillingness to ally with them.

Scholars also study the development of welfare states and public social provision, the emergence and character of such systems, and/or their perceived ongoing decline in neoliberal capitalism (see Marshell 1950; Korpi, 1983; Huber and Stephens, 2001; Pierson, 1994). In general, political sociology emphasizes social inequalities along various dimensions and their impact on welfare states. Esping-Andersen (1990) explores the origins and role of welfare states in European capitalist countries, emphasizing the impact of working class power and varying class coalitions on the character of welfare states and regimes of public social provision. Fox (2012) explores the American social welfare system and how different racial and immigrant groups receive differential access to social welfare programs, whereas Misra (1998, 2003) analyzes family allowance policies, and the role of women’s movements and the perceived value of women’s paid and unpaid labor for variations in public social provision. Venturing to the global South, Sandbrook et al. (2007) look at social democratic movements and democratic developmental states, and how some peripheral states have balanced the achievement of economic growth through globalized markets with relatively progressive social and political policies.

In a world of stark international inequalities, studies of development attempt to unravel the social and political processes behind prosperous economies with a focus on class relations, the state, and economic institutions. These works often center on the concerted efforts of post–World War II ‘developmental’ states, traversing state building, economic development, and postcolonialism. A major thrust in this literature explores conditions in which states and state leaders gain the wherewithal to ignite and sustain industrialization. One broad statist explanation focuses on state capacity and autonomy to guide and discipline capitalists (and labor), thus bolstering state planning agencies to drive developmental policies (Amsden, 1989; Evans, 1995; Wade, 1990). Some challenge, or refine, this state autonomy/capacity thesis. Chibber (2003) brings back in structural political economy to consider class alliances and interests, state capacity and autonomy, and international economic opportunity to explain situations where local capitalists gain from, and thus support, the strengthening autonomous state economic planning agencies (as in South Korea) and, conversely, (in cases where capitalists would suffer from, and thus stifle these institutions), robust development agencies and planning (as in India). His study illuminates crucial class and state processes impacting relative success versus relative failure, and deepens the understanding of capitalist classes in developmental states. Finally, Mahoney (2010) studies the impact of colonial arrangements on postcolonial development, and how institutional fit (or non-fit) between colonizer and colonized greatly influenced longer-term economic development.

Recent scholarship on revolution has shifted focus from the ‘great’ social revolutions (Moore, 1966; Skocpol, 1979) to political revolutions and revolutionary movements, and their varying forms and outcomes, in the post–World War II world. Political sociologists emphasize social compositional factors, regime types, and socioeconomic structure. Parsa (1989) offers a sophisticated articulation of the multi-class coalition thesis, arguing that the ‘success’ of the Iranian revolution was rooted in multiple social classes mobilizing in a common oppositional front outside the formal power structure of the Shah’s autocratic regime. Accepting the import of class struggle, Goodwin (2001) refines a statist approach in his study of revolutions in Latin America, SE Asia, and East Europe, arguing that particular neopatrimonial state-regime types may not only incubate and encourage revolutionary movements but also impact the success of such movements in engendering political revolution. In a cultural turn, Slater (2009) holds that the political posture and emotive appeals of communal elites – those with religious and cultural authority – determines the emergence and outcome of revolutionary mobilization. Finally, Achcar (2013) extends and modifies Marx’s theory of social revolution to analyze recent uprisings in the Arab world, arguing that it is the specific modality of an economic mode of production, especially in the political and legal structures that block social and economic development, rather than the generic economic mode itself, that may provide crucial causes for popular uprisings and thus become the object of political revolution.

Globalization naturally attracts considerable scholarly attention, providing numerous areas of inquiry. Political sociologists tend to focus on power relations in global capitalism and the consequences for development, the political institutions that undergird attendant policies, as well as salient spatial and organizational transformations. Dependency scholars Cardoso and Faletto (1979) critique Modernization theory’s universal linear stage model of development, and prioritize asymmetrical and partially constitutive international power relations and their affects on national political and economic development. The world-systems tradition has long analyzed national and regional development in the light of the character and dynamic of global capitalism (Wallerstein, 1974/2011) and imperial hegemonies (Arrighi, 1994); yet many drop a level of analysis to examine crucial shorterterm political processes linked to a globalizing world. Babb (2009) explores institutional linkages between the American state (especially the legislative branch) and multilateral development banks, and Washington’s political sway over them. Others explore China’s rise and how it has helped reshape the structure and dynamics of global capitalism, as well as its geopolitical impact on China’s close neighbors (Hung, 2009), global cities (Sassen, 2001), international organizations (Boli and Thomas, 2003), and so on.

Relatedly, neoliberal globalization, many argue, fundamentally includes financialization and attendant transformations that diminish the quality of public social provision, and political sociologists have analyzed multiple facets of these phenomena. Tabb (2012) investigates the restructuring of capitalism from the 1970s onward, specifically with regard to banking practices, financial motives, and regulatory policies. Krippner (2011) studies the historical development of the US financial market and the creation of market policies conducive to financialization, arguing that these were not policymakers’ deliberate goals but the inadvertent results of attempts to solve pressing economic problems. Prechel and Morris (2010) explore the causes of financial malfeasance from 1995 to 2004 and how certain social structures create dependencies, incentives, and opportunities to engage in such behavior, i.e., neoliberal policies permit such activities, and largely result from well-financed and systematic corporate political strategy.

Immigration and citizenship in the globalizing world continues to capture scholars’ attention, with the migration of people across countries clearly linked to potentially salient social, political, and economic transformations. Portes and Rumbaut (2006) provide a prominent overview of immigrant social and political dynamics in the US, honing in on micro- and macro-level processes impacting immigrants’ individual lives as well as the wider social and political formations to which they belong. Bloemraad (2006) queries how countries that allow the entrance of immigrants and refugees can foster civic cohesion and political community, and tempers the widespread emphasis on features of immigrant communities by considering the impact of state policy for outcomes of citizenship acquisition and political participation. Furthermore, the global salience of ‘market fundamentalism’, argues Somers (2008), subjugates notions and practices of citizenship to market logic and yields deleterious results for people’s lives.

Scholars continue to investigate social bases of politics and political behavior, which has been a hallmark of political sociology since at least the 1950s. Domhoff (1990) and Domhoff and Webber (2011) refine the class dominance theory to look at social networks of power and the role of capitalist class segments on the origins of major social policies; while Manza and Brooks (1999) consider more broadly the role social group cleavages have on electoral politics. Clawson et al. (1998) investigate the role of financial contributions in policy formation, and the relationships that may develop between politicians and private contributors. Scholars in this general line of inquiry also explore issues surrounding political parties (Panebianco, 1988; Shefter, 1994), public opinion (Dalton, 2008), and interest groups and other political organizations (Wilson, 1995).

The concept of culture is not only disputed in terms of its specific meaning(s), but it is also broad, multifaceted, and at times muddled, with cultural studies of politics employing the concept in wide-ranging and varying ways. Using a dynamic theoretical framework, Campbell (1998) explores how ideas – paradigms, public sentiments, programs, and frames – may influence major policy-making innovations. For Ermakoff (2008), subjective orientations and patterns of interactions impact major political change and the surrender of democratic to nondemocratic authority, while Ikegami (2005) details the interconnections of arts and esthetics with state–society relations in a case of state formation where esthetic socialization compensated for state policies that fostered extreme social fragmentation. Others explore folk music’s unifying and galvanizing power, and the relation between cultural forms and social or labor movement activities (Roscigno and Danaher, 2004). In a different vein, important studies of the media examine the mass media in multiple ways, seeing a powerful and effective ideological institution that props the political status quo (Chomsky and Herman, 1988/2008) – society’s “master arena” where individual or collective political actors engage in contests over social meanings (Gamson and Andre, 2004), the interactions of media discourse and public opinion formation (Gamson and Modigliani, 1989), and the news media as a political institution (Schudson, 2002). Also, in an ambitious macrophenomelogical approach and in macro-social theory, the world societal perspective prioritizes global culture in the production and spread of ideas, policies, and institutions (Meyer et al., 1997).

Other than world-systems scholars (Wallerstein and Arrighi), Michael Mann (1986, 1993, 2012, 2013) is one of the few contemporary political sociologists who attempts to rigorously identify the principal social-structural trends across history and to explain the development and expansion of fundamental power structures. Mann proposes the IEMP model, which holds that human societies form around four power relations – ideological, economic, military, and political – that are intertwined although none is purely reducible to another. For Mann, contemporary globalization is the “plural extension” of these four relations, with the primary modern power organizations (capitalism, nation-states, and empires) congealing around them. This globalization thus consists of three main institutional processes, the globalization of capitalism, the nation-state, and empires (eventually just the American empire). These processes, however, crystalize in various, often competing forms and have thus been geographically and institutionally polymorphous.

Certainly there are remarkable areas of social and political inquiry not included in the above survey, and even those discussed are only briefly introduced. There are veritable literatures on the political processes of empire and imperialism (Harvey, 2003; Wood, 2005), nationalism (Breuilly, 1994; Hobsbawm, 1990), labor and labor movements (Stepan-Norris and Zeitlin, 2003; Fantasia, 1989), ethnicity and ethnic conflict (Varshney, 2003; Gutiérrez, 1995), and so on. Nonetheless, there are several clear features or trends that manifest in this survey. Political sociology literature continues to emphasize civil society and potentially vital socioeconomic factors, in contrast to much of political science. With the aid of methodological advances, political sociologists continue to develop various theoretical frameworks and to expand the substantive breadth and depth of this border field. Scholars enter empirical cases from differing levels of analysis to address an inherently wide set of questions.With these diverse research approaches, political sociologists continue to cultivate useful knowledge through rigorous empirical research on social and political change as well as the basic problems afflicting societies, and thus remain relevant to policy-oriented debates. Echoing the previous entry from the first edition, political sociology’s main general problem areas continue to revolve around the origins, character, and practices of social and political power and conflict; dominant and emerging cleavages; patterns of social, political, economic, and cultural change; the formation of states and nations as well as the breakdown of social and political orders; the conditions of different regime-types (e.g., democracy or authoritarianism); capitalist development; and multifaceted international relationships. For better or worse, these are vital areas of inquiry that will continue to provide attendant puzzles and problems to be scrutinized by political sociologists.

References:

- Abrams, Philip, 1982. Historical Sociology. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- Achcar, Gilbert, 2013. The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Alford, Robert R., Friedland, Roger, 1985. Powers of Theory: Capitalism, the State, and Democracy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Allardt, Erik, 2001. Political Sociology. In: Neil Smelser, J., Paul Baltes, B. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, vol. 11. Elsevier, New York and Amsterdam, pp. 11701–11706.

- Amenta, Edwin, Ramsey, Kelly, 2010. “Institutional Theory” Handbook of Politics. Springer, New York, pp. 15–39.

- Amenta, Edwin, Nash, Kate, Scott, Alan (Eds.), 2012. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Political Sociology. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Amsden, Alice, 1989. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Anderson, Benedict, 1983/2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, New York.

- Anderson, Perry, 1974/2013. Lineages of the Absolutist State. Verso, New York.

- Aron, Raymond, 2009. The Opium of the Intellectuals. Transaction Books, New York.

- Arrighi, Giovanni, 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. Verso, New York.

- Babb, Sarah, 2009. Behind the Development Banks: Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Bloemraad, Irene, 2006. Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Boli, John, Thomas, George M., 2003. Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations since 1875. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, 1984/2013. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Routledge, New York.

- Breuilly, John, 1994. Nationalism and the State. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Campbell, John L., 1998. Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society 27 (3), 377–409.

- Cardoso, Fernando, Faletto, Enzo, 1979. Dependency and Development in Latin America. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Centeno, Miguel A., 2003. Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park.

- Chibber, Vivek, 2003. Locked in Place: State-Building and Capitalist Industrialization in India, 1940–1970. Princeton University Press, New Haven.

- Chomsky, Noam, Herman, Edward S., 1988/2008. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Random House, USA.

- Chong, Dennis, 2000. Rational Lives: Norms and Values in Politics and Society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Clawson, Dan, Neustadtl, Alan, Weller, Mark, 1998. Dollars and Votes: How Business Campaign Contributions Subvert Democracy. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

- Dahl, Robert A., 1961. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Dahrendorf, Ralf, 1959. Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

- Dalton, Russell J., 2008. Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Sage, New York.

- Domhoff, G., Webber, Michael J., 2011. Class and Power in the New Deal: Corporate Moderates, Southern Democrats, and the Liberal-Labor Coalition. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto.

- Domhoff, William G., 1967. Who Rules America? Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Domhoff, William G., 1990. The Power Elite and the State: How Policy is Made in America. Aldine de Gruyter, Hawthorne, NY.

- Easton, David, 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. Wiley, New York.

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N., 1963/1993. The Political Systems of Empires. Transaction, New York.

- Ermakoff, Ivan, 2008. Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications. Duke University Press, North Carolina.

- Ertman, Thomas, 1997. Birth of the Leviathan: Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta, 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Evans, Peter, 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

- Fantasia, Rick, 1989. Cultures of Solidarity: Consciousness, Action, and Contemporary American Workers. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Fox, Cybelle, 2012. Three Worlds of Relief: Race, Immigration, and the American Welfare State from the Progressive Era to the New Deal. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

- Gamson, William A., Andre, Modigliani, 2004. Bystanders, public opinion, and the media. In: Snow, David A., Soule, Sarah A., Hanspeter, Kriesi (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Blackwell Publishers, Malden, pp. 242–261.

- Gamson, William A., Modigliani, Andre, 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95 (1), 1–37.

- Gilroy, Paul, 1991. ‘There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Goodwin, Jeff, 2001. No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945–1991. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Gorski, Philip S., 2003. The Disciplinary Revolution: Calvinism and the Rise of the State in Early Modern Europe. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Gurr, Ted, 1970. Why Men Rebel. Paradigm, New York.

- Gutiérrez, David G., 1995. Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Harvey, David, 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Heydemann, Steven (Ed.), 2000. War, Institutions, and Social Change in the Middle East. University of California Press, Los Angeles and Berkeley.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, 1990. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Huber, Evelyne, Stephens, John D., 2001. Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Hung, Ho-fung, 2009. China and the Transformation of Global Capitalism. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

- Ikegami, Eiko, 2005. Bonds of Civility: Aesthetic Networks and the Political Origins of Japanese Culture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Inglehart, Ronald, 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

- Janoski, Thomas, Alford, Robert R., Hicks, Alexander M., Schwartz, Mildred A. (Eds.), 2005. The Handbook of Political Sociology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Kornhauser, William, 1959/2013. Politics of Mass Society. Routledge, New York. Korpi, Walter, 1983. The Democratic Class Struggle. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

- Krippner, Greta, 2011. Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Lazarsfeld, Paul F., Berelson, Bernard, Gaudet, Hazel, 1944. The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Linz, Juan J., Stepan, Alfred C. (Eds.), 1978. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes, Latin America. Johns Hopkins University Press, DC.

- Lipset, Seymour M., 1960. Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Washington, DC.

- Lipset, Seymour M., Rokkan, Stein (Eds.), 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. Free Press, New York.

- Lipset, Seymour M., Trow, Martin A., Coleman, James S., 1956. Union Democracy: The Internal Politics of the International Typographical Union. Free Press, Glencoe.

- Mahoney, James, 2010. Colonialism and Postcolonial Development. Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), New York.

- Mahoney, James, Rueschemeyer, Dietrich (Eds.), 2003. Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Mann, Michael, 1986, 1993, 2012, 2013. The Sources of Social Power, vols. 1–4. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Manza, Jeff, Brooks, Clem, 1999. Social Cleavages and Political Change: Voter Alignments and US Party Coalitions. Oxford University Press, Oxford.