- Scroll to top

- Light Dark Light Dark

Cart review

No products in the cart.

7 Powerful Steps in Sampling Design for Effective Research

- Author Survey Point Team

- Published January 3, 2024

Unlock the secrets of effective research with these 7 powerful steps in sampling design. Elevate your research game and ensure precision from the outset. Dive into a world of insights and methodology that guarantees meaningful results.

Research forms the foundation of knowledge and understanding in any field. The quality and validity of research depend largely on the sampling design used. An effective sampling design ensures unbiased and reliable results that can be generalized to the entire population. In this article, we will explore seven powerful steps in sampling design that researchers can follow to conduct effective research.

Table of Contents

1. Define the Research Objectives

Before diving into the sampling design process, it is vital to define the research objectives. Clearly determining what you aim to achieve through the research will guide the entire sampling design. Whether it is to study consumer behavior, analyze market trends, or explore the impact of a specific intervention, outlining the research objectives provides a clear roadmap for sampling.

Example: Without a clear research objective, sampling becomes directionless, leading to inaccurate results that do not contribute to meaningful insights.

2. Identify the Target Population

After defining the research objectives, identifying the target population is the next crucial step. The target population represents the group of individuals or elements that the research aims to generalize the findings to. It is essential to clearly define and understand the demographics, characteristics, and parameters of the target population before moving forward with sampling.

Example: Identifying the target population allows researchers to ensure that the sampled individuals represent the broader group accurately, increasing the external validity of the study.

3. Determine the Sample Size

Determining the appropriate sample size is a critical factor in sampling design. A sample size that is too small may not accurately represent the target population, while a sample size that is too large may result in unnecessary costs and resources. Determining the sample size requires considering various factors, such as desired level of precision, variability within the population, and available resources.

Example: The sample size should strike a balance between statistical reliability and practical feasibility. A larger sample size increases the precision of the estimates, while a smaller sample size may result in wider confidence intervals.

4. Select the Sampling Technique

Various sampling techniques exist, each catering to different research scenarios. The choice of sampling technique depends on the nature of the research, available resources, and the level of precision required. Common sampling techniques include simple random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, and systematic sampling.

Example: Understanding the different sampling techniques allows researchers to choose the most appropriate method for their specific research, ensuring representative and reliable results.

5. Implement the Sampling Strategy

Once the sampling technique is selected, it is time to implement the sampling strategy. This involves identifying the potential sampling units and selecting the actual sample elements from the target population. Researchers must avoid any biases and ensure randomness in the selection process to maintain the integrity of the research findings.

Example: Implementing the sampling strategy meticulously enables researchers to minimize potential biases and increase the chances of obtaining accurate results that can be generalized to the larger population.

6. Collect Data from the Sample: Steps in Sampling Design

With the sample selected, data collection becomes the next crucial step. Researchers can use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments, to collect the necessary data. It is essential to follow the research design and consider data quality measures to ensure the reliability and validity of the collected information.

Example: Collecting data from the sample involves establishing effective communication channels, designing appropriate data collection instruments, and capturing the information accurately to minimize measurement errors.

7. Analyze and Interpret the Findings

Once the data is collected, it is time to analyze and interpret the findings. This involves applying statistical techniques, conducting hypothesis testing, and drawing meaningful conclusions. Researchers should ensure they have the necessary analytical skills or collaborate with experts in data analysis to derive accurate and insightful results.

Example: Analyzing and interpreting the findings allows researchers to draw meaningful conclusions and make informed decisions based on the evidence obtained through the research process.

Top 10 Sampling Techniques along with their respective Pros and Cons :

This table provides a quick overview of the strengths and weaknesses of each sampling technique, aiding researchers in selecting the most appropriate method for their specific research objectives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why is defining research objectives the first step in sampling design?

A: Defining research objectives sets a clear direction for the study, ensuring focus and purpose in the subsequent steps.

Q: How does the selection of a sampling frame impact research outcomes?

A: The sampling frame defines the accessible population, influencing the generalizability of results to the broader context.

Q: What factors influence the choice of a sampling technique?

A: Research objectives and the nature of the study guide the choice of a sampling technique, ensuring alignment with the research goals.

Q: Why is determining the sample size crucial in sampling design?

A: The sample size strikes a delicate balance, ensuring accuracy in representation while maintaining manageability.

Q: How do data collection methods align with the chosen sampling design?

A: The sampling design informs the selection of data collection methods, ensuring synergy for a comprehensive research approach.

Q: Why is analysis and interpretation the culmination of the sampling design process?

A: Analysis and interpretation transform raw data into actionable knowledge, realizing the objectives set at the beginning of the research journey.

Sampling design plays a fundamental role in conducting effective research. By following the seven powerful steps outlined in this article – defining research objectives, identifying the target population, determining the sample size, selecting the sampling technique, implementing the sampling strategy, collecting data from the sample, and analyzing and interpreting the findings – researchers can ensure reliable, valid, and generalizable results. Adopting a systematic and rigorous approach to sampling design will ultimately enhance the impact of research across various fields.

Remember, a solid sampling design empowers researchers to capture the essence of a larger population, revealing valuable insights that drive progress and innovation.

Survey Point Team

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Research Methods

Sampling and Sample Design

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Introduction to Research Methods

- Designing Research

- Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Designs

- Interviews for Research

- Focus Groups

- Qualitative Data from Interactions

- Quantitative Research Designs

- Surveys and Survey Design

- Observational Research and Secondary Data

- Analysing Research Data

- Analysing Qualitative Data

- Simple Statistical Analysis

- Statistical Analysis: Types of Data

- Understanding Correlations

- Understanding Statistical Distributions

- Significance and Confidence Intervals

- Developing and Testing Hypotheses

- Multivariate Analysis

Get the SkillsYouNeed Research Methods eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

When you collect any sort of data, especially quantitative data , whether observational, through surveys or from secondary data, you need to decide which data to collect and from whom.

This is called the sample .

There are a variety of ways to select your sample, and to make sure that it gives you results that will be reliable and credible.

The difference between population and sample

Ideally, research would collect information from every single member of the population that you are studying. However, most of the time that would take too long and so you have to select a suitable sample: a subset of the population.

Principles Behind Choosing a Sample

The idea behind selecting a sample is to be able to generalise your findings to the whole population, which means that your sample must be:

Representative of the population. In other words, it should contain similar proportions of subgroups as the whole population, and not exclude any particular groups, either by method of sampling or by design, or by who chooses to respond.

Large enough to give you enough information to avoid errors . It does not need to be a specific proportion of your population, but it does need to be at least a certain size so that you know that your answers are likely to be broadly correct.

If your sample is not representative, you can introduce bias into the study. If it is not large enough, the study will be imprecise .

However, if you get the relationship between sample and population right, then you can draw strong conclusions about the nature of the population.

Sample size: how long is a piece of string?

How large should your sample be? It depends how precise you want the answer. Larger samples generally give more precise answers.

Your desired sample size depends on what you are measuring and the size of the error that you’re prepared to accept. For example:

To estimate a proportion in a population:

Sample size =[ (z-score)² × p(1-p) ] ÷ (margin of error)²

- The margin of error is what you are prepared to accept (usually between 1% and 10%);

- The z-score, also called the z value, is found from statistical tables and depends on the confidence interval chosen (90%, 95% and 99% are commonly used, so choose which one you want);

- p is your estimate of what the proportion is likely to be. You can often estimate p from previous research, but if you can’t do that then use 0.5.

To estimate a population mean:

Margin of error = t × (s ÷ square root of the sample size).

- Margin of error is what you are prepared to accept (usually between 1% and 10%);;

- As long as the sample size is larger than about 30, t is equivalent to the z score, and available from statistical tables as before;

- s is the standard deviation, which is usually guessed, based on previous experience or other research.

If you’re not very confident about this kind of thing, then the best way to deal with it is to find a friendly statistician and ask for some help. Most of them will be delighted to help you make sense of their specialty.

It is better to be imprecisely right than precisely wrong.

How bias and precision interact:

Source: Management Research (4th Edition), Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Jackson

Imprecisely right means that you know broadly what the correct answer is. Precisely wrong means that you think you know the answer, but you don’t. In other words, if you can only worry about one, worry about bias.

Selecting a Sample

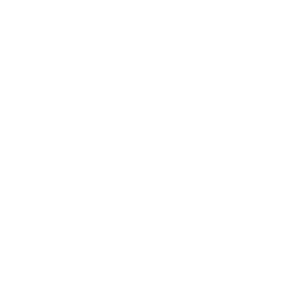

Probability sampling is where the probability of each person or thing being part of the sample is known. Non-probability sampling is where it is not.

Probability Sampling

Probability sampling methods allow the researcher to be precise about the relationship between the sample and the population.

This means that you can be absolutely confident about whether your sample is representative or not, and you can also put a number on how certain you are about your findings (this number is called the significance , and is discussed further in our page on Significance and Confidence Intervals ).

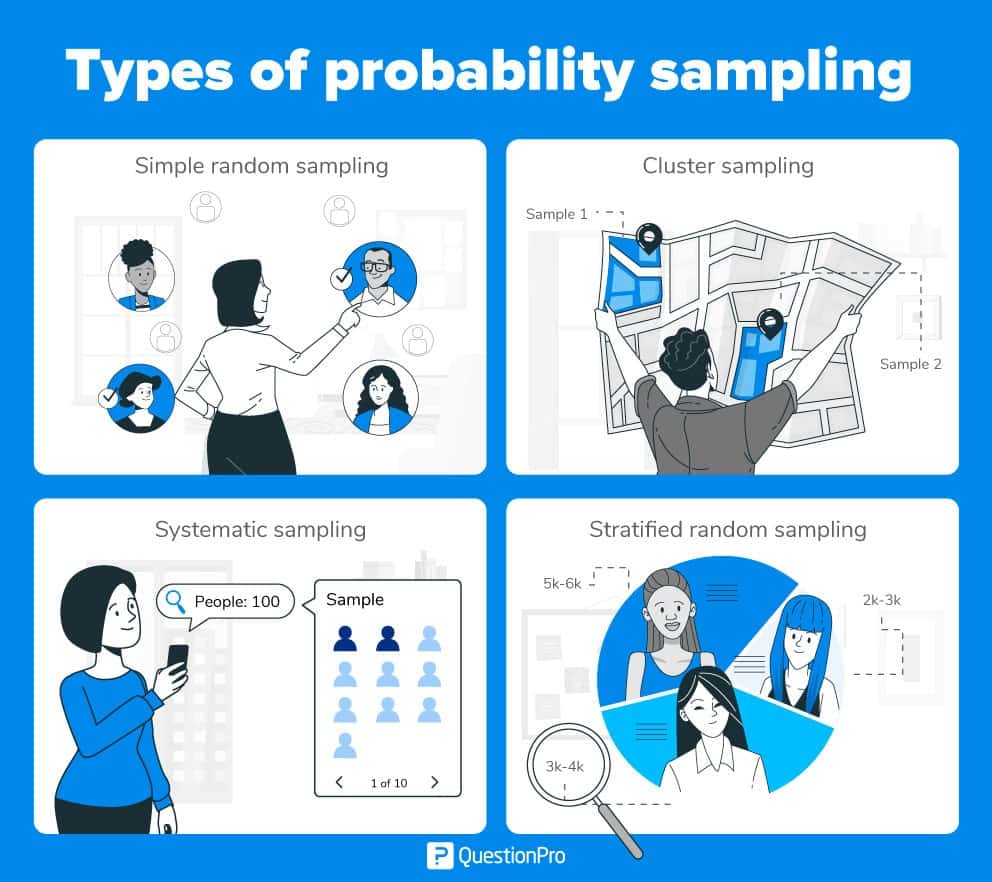

In simple random sampling , every member of the population has an equal chance of being chosen. The drawback is that the sample may not be genuinely representative. Small but important sub-sections of the population may not be included.

Researchers therefore developed an alternative method called stratified random sampling . This method divides the population into smaller homogeneous groups, called strata, and then takes a random sample from each stratum.

Proportional stratified random sampling takes the same proportion from each stratum, but again suffers from the disadvantage that rare groups will be badly represented. Non-proportional stratified sampling therefore takes a larger sample from the smaller strata, to ensure that there is a large enough sample from each stratum.

Systematic random sampling relies on having a list of the population, which should ideally be randomly ordered. The researcher then takes every n th name from the list.

There are many different methods of selecting ‘random samples’. If you are the lead researcher for a project and instructing others to ‘take a random sample’, or indeed asked to take a ‘random sample’, make sure you are all using the same method!

Cluster sampling is designed to address problems of a widespread geographical population. Random sampling from a large population is likely to lead to high costs of access. This can be overcome by dividing the population into clusters, selecting only two or three clusters, and sampling from within those. For example, if you wished to find out about the use of transport in urban areas in the UK, you could randomly select just two or three cities, and then sample fully from within these.

It is, of course, possible to combine all these in several stages, which is often done for large-scale studies.

Non-Probability Sampling

Using non-probability sampling methods, it is not possible to say what is the probability of any particular member of the population being sampled. Although this does not make the sample ‘bad’, researchers using such samples cannot be as confident in drawing conclusions about the whole population.

Convenience sampling selects a sample on the basis of how easy it is to access. Such samples are extremely easy to organise, but there is no way to guarantee whether they are representative.

Quota sampling divides the population into categories, and then selects from within categories until a sample of the chosen size is obtained within that category. Some market research is this type, which is why researchers often ask for your age: they are checking whether you will help them meet their quotas for particular age groups.

Purposive sampling is where the researcher only approaches people who meet certain criteria, and then checks whether they meet other criteria. Again, market researchers out and about with clipboards often use this approach: for example, if they are looking to examine the shopping habits of men aged between 20 and 40, they would only approach men, and then ask their age.

Snowball sampling is where the researcher starts with one person who meets their criteria, and then uses that person to identify others. This works well when your sample has very specific criteria: for example, if you want to talk to workers with a particular set of responsibilities, you might approach one person with that set, and ask them to introduce you to others.

Non-probability sampling methods have generally been developed to address very specific problems. For example, snowball sampling deals with hard-to-find populations, and convenience sampling allows for speed and ease.

However, although some non-probability sampling methods, particularly quota and purposive sampling, ensure the sample draws from all categories in the population, samples taken using these methods may not be representative.

A Word in Conclusion

Almost all research is a compromise between the ideal and the possible.

Ideally, you would study the whole population; in practice, you don’t have time or capacity. But care in your sample selection, both size and method, will ensure that your research does not fall into the traps of either introducing bias, or lacking precision. This, in turn, will give it that vital credibility.

Continue to: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods Surveys and Survey Design

See also: Designing Research Analysing Qualitative Data Simple Statistical Analysis

An overview of sampling methods

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

When researching perceptions or attributes of a product, service, or people, you have two options:

Survey every person in your chosen group (the target market, or population), collate your responses, and reach your conclusions.

Select a smaller group from within your target market and use their answers to represent everyone. This option is sampling .

Sampling saves you time and money. When you use the sampling method, the whole population being studied is called the sampling frame .

The sample you choose should represent your target market, or the sampling frame, well enough to do one of the following:

Generalize your findings across the sampling frame and use them as though you had surveyed everyone

Use the findings to decide on your next step, which might involve more in-depth sampling

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

How was sampling developed?

Valery Glivenko and Francesco Cantelli, two mathematicians studying probability theory in the early 1900s, devised the sampling method. Their research showed that a properly chosen sample of people would reflect the larger group’s status, opinions, decisions, and decision-making steps.

They proved you don't need to survey the entire target market, thereby saving the rest of us a lot of time and money.

- Why is sampling important?

We’ve already touched on the fact that sampling saves you time and money. When you get reliable results quickly, you can act on them sooner. And the money you save can pay for something else.

It’s often easier to survey a sample than a whole population. Sample inferences can be more reliable than those you get from a very large group because you can choose your samples carefully and scientifically.

Sampling is also useful because it is often impossible to survey the entire population. You probably have no choice but to collect only a sample in the first place.

Because you’re working with fewer people, you can collect richer data, which makes your research more accurate. You can:

Ask more questions

Go into more detail

Seek opinions instead of just collecting facts

Observe user behaviors

Double-check your findings if you need to

In short, sampling works! Let's take a look at the most common sampling methods.

- Types of sampling methods

There are two main sampling methods: probability sampling and non-probability sampling. These can be further refined, which we'll cover shortly. You can then decide which approach best suits your research project.

Probability sampling method

Probability sampling is used in quantitative research , so it provides data on the survey topic in terms of numbers. Probability relates to mathematics, hence the name ‘quantitative research’. Subjects are asked questions like:

How many boxes of candy do you buy at one time?

How often do you shop for candy?

How much would you pay for a box of candy?

This method is also called random sampling because everyone in the target market has an equal chance of being chosen for the survey. It is designed to reduce sampling error for the most important variables. You should, therefore, get results that fairly reflect the larger population.

Non-probability sampling method

In this method, not everyone has an equal chance of being part of the sample. It's usually easier (and cheaper) to select people for the sample group. You choose people who are more likely to be involved in or know more about the topic you’re researching.

Non-probability sampling is used for qualitative research. Qualitative data is generated by questions like:

Where do you usually shop for candy (supermarket, gas station, etc.?)

Which candy brand do you usually buy?

Why do you like that brand?

- Probability sampling methods

Here are five ways of doing probability sampling:

Simple random sampling (basic probability sampling)

Systematic sampling

Stratified sampling.

Cluster sampling

Multi-stage sampling

Simple random sampling.

There are three basic steps to simple random sampling:

Choose your sampling frame.

Decide on your sample size. Make sure it is large enough to give you reliable data.

Randomly choose your sample participants.

You could put all their names in a hat, shake the hat to mix the names, and pull out however many names you want in your sample (without looking!)

You could be more scientific by giving each participant a number and then using a random number generator program to choose the numbers.

Instead of choosing names or numbers, you decide beforehand on a selection method. For example, collect all the names in your sampling frame and start at, for example, the fifth person on the list, then choose every fourth name or every tenth name. Alternatively, you could choose everyone whose last name begins with randomly-selected initials, such as A, G, or W.

Choose your system of selecting names, and away you go.

This is a more sophisticated way to choose your sample. You break the sampling frame down into important subgroups or strata . Then, decide how many you want in your sample, and choose an equal number (or a proportionate number) from each subgroup.

For example, you want to survey how many people in a geographic area buy candy, so you compile a list of everyone in that area. You then break that list down into, for example, males and females, then into pre-teens, teenagers, young adults, senior citizens, etc. who are male or female.

So, if there are 1,000 young male adults and 2,000 young female adults in the whole sampling frame, you may want to choose 100 males and 200 females to keep the proportions balanced. You then choose the individual survey participants through the systematic sampling method.

Clustered sampling

This method is used when you want to subdivide a sample into smaller groups or clusters that are geographically or organizationally related.

Let’s say you’re doing quantitative research into candy sales. You could choose your sample participants from urban, suburban, or rural populations. This would give you three geographic clusters from which to select your participants.

This is a more refined way of doing cluster sampling. Let’s say you have your urban cluster, which is your primary sampling unit. You can subdivide this into a secondary sampling unit, say, participants who typically buy their candy in supermarkets. You could then further subdivide this group into your ultimate sampling unit. Finally, you select the actual survey participants from this unit.

- Uses of probability sampling

Probability sampling has three main advantages:

It helps minimizes the likelihood of sampling bias. How you choose your sample determines the quality of your results. Probability sampling gives you an unbiased, randomly selected sample of your target market.

It allows you to create representative samples and subgroups within a sample out of a large or diverse target market.

It lets you use sophisticated statistical methods to select as close to perfect samples as possible.

- Non-probability sampling methods

To recap, with non-probability sampling, you choose people for your sample in a non-random way, so not everyone in your sampling frame has an equal chance of being chosen. Your research findings, therefore, may not be as representative overall as probability sampling, but you may not want them to be.

Sampling bias is not a concern if all potential survey participants share similar traits. For example, you may want to specifically focus on young male adults who spend more than others on candy. In addition, it is usually a cheaper and quicker method because you don't have to work out a complex selection system that represents the entire population in that community.

Researchers do need to be mindful of carefully considering the strengths and limitations of each method before selecting a sampling technique.

Non-probability sampling is best for exploratory research , such as at the beginning of a research project.

There are five main types of non-probability sampling methods:

Convenience sampling

Purposive sampling, voluntary response sampling, snowball sampling, quota sampling.

The strategy of convenience sampling is to choose your sample quickly and efficiently, using the least effort, usually to save money.

Let's say you want to survey the opinions of 100 millennials about a particular topic. You could send out a questionnaire over the social media platforms millennials use. Ask respondents to confirm their birth year at the top of their response sheet and, when you have your 100 responses, begin your analysis. Or you could visit restaurants and bars where millennials spend their evenings and sign people up.

A drawback of convenience sampling is that it may not yield results that apply to a broader population.

This method relies on your judgment to choose the most likely sample to deliver the most useful results. You must know enough about the survey goals and the sampling frame to choose the most appropriate sample respondents.

Your knowledge and experience save you time because you know your ideal sample candidates, so you should get high-quality results.

This method is similar to convenience sampling, but it is based on potential sample members volunteering rather than you looking for people.

You make it known you want to do a survey on a particular topic for a particular reason and wait until enough people volunteer. Then you give them the questionnaire or arrange interviews to ask your questions directly.

Snowball sampling involves asking selected participants to refer others who may qualify for the survey. This method is best used when there is no sampling frame available. It is also useful when the researcher doesn’t know much about the target population.

Let's say you want to research a niche topic that involves people who may be difficult to locate. For our candy example, this could be young males who buy a lot of candy, go rock climbing during the day, and watch adventure movies at night. You ask each participant to name others they know who do the same things, so you can contact them. As you make contact with more people, your sample 'snowballs' until you have all the names you need.

This sampling method involves collecting the specific number of units (quotas) from your predetermined subpopulations. Quota sampling is a way of ensuring that your sample accurately represents the sampling frame.

- Uses of non-probability sampling

You can use non-probability sampling when you:

Want to do a quick test to see if a more detailed and sophisticated survey may be worthwhile

Want to explore an idea to see if it 'has legs'

Launch a pilot study

Do some initial qualitative research

Have little time or money available (half a loaf is better than no bread at all)

Want to see if the initial results will help you justify a longer, more detailed, and more expensive research project

- The main types of sampling bias, and how to avoid them

Sampling bias can fog or limit your research results. This will have an impact when you generalize your results across the whole target market. The two main causes of sampling bias are faulty research design and poor data collection or recording. They can affect probability and non-probability sampling.

Faulty research

If a surveyor chooses participants inappropriately, the results will not reflect the population as a whole.

A famous example is the 1948 presidential race. A telephone survey was conducted to see which candidate had more support. The problem with the research design was that, in 1948, most people with telephones were wealthy, and their opinions were very different from voters as a whole. The research implied Dewey would win, but it was Truman who became president.

Poor data collection or recording

This problem speaks for itself. The survey may be well structured, the sample groups appropriate, the questions clear and easy to understand, and the cluster sizes appropriate. But if surveyors check the wrong boxes when they get an answer or if the entire subgroup results are lost, the survey results will be biased.

How do you minimize bias in sampling?

To get results you can rely on, you must:

Know enough about your target market

Choose one or more sample surveys to cover the whole target market properly

Choose enough people in each sample so your results mirror your target market

Have content validity . This means the content of your questions must be direct and efficiently worded. If it isn’t, the viability of your survey could be questioned. That would also be a waste of time and money, so make the wording of your questions your top focus.

If using probability sampling, make sure your sampling frame includes everyone it should and that your random sampling selection process includes the right proportion of the subgroups

If using non-probability sampling, focus on fairness, equality, and completeness in identifying your samples and subgroups. Then balance those criteria against simple convenience or other relevant factors.

What are the five types of sampling bias?

Self-selection bias. If you mass-mail questionnaires to everyone in the sample, you’re more likely to get results from people with extrovert or activist personalities and not from introverts or pragmatists. So if your convenience sampling focuses on getting your quota responses quickly, it may be skewed.

Non-response bias. Unhappy customers, stressed-out employees, or other sub-groups may not want to cooperate or they may pull out early.

Undercoverage bias. If your survey is done, say, via email or social media platforms, it will miss people without internet access, such as those living in rural areas, the elderly, or lower-income groups.

Survivorship bias. Unsuccessful people are less likely to take part. Another example may be a researcher excluding results that don’t support the overall goal. If the CEO wants to tell the shareholders about a successful product or project at the AGM, some less positive survey results may go “missing” (to take an extreme example.) The result is that your data will reflect an overly optimistic representation of the truth.

Pre-screening bias. If the researcher, whose experience and knowledge are being used to pre-select respondents in a judgmental sampling, focuses more on convenience than judgment, the results may be compromised.

How do you minimize sampling bias?

Focus on the bullet points in the next section and:

Make survey questionnaires as direct, easy, short, and available as possible, so participants are more likely to complete them accurately and send them back

Follow up with the people who have been selected but have not returned their responses

Ignore any pressure that may produce bias

- How do you decide on the type of sampling to use?

Use the ideas you've gleaned from this article to give yourself a platform, then choose the best method to meet your goals while staying within your time and cost limits.

If it isn't obvious which method you should choose, use this strategy:

Clarify your research goals

Clarify how accurate your research results must be to reach your goals

Evaluate your goals against time and budget

List the two or three most obvious sampling methods that will work for you

Confirm the availability of your resources (researchers, computer time, etc.)

Compare each of the possible methods with your goals, accuracy, precision, resource, time, and cost constraints

Make your decision

- The takeaway

Effective market research is the basis of successful marketing, advertising, and future productivity. By selecting the most appropriate sampling methods, you will collect the most useful market data and make the most effective decisions.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur J Gen Pract

- v.24(1); 2018

Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis

Albine moser.

a Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre Autonomy and Participation of Chronically Ill People , Zuyd University of Applied Sciences , Heerlen, The Netherlands

b Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Family Medicine , Maastricht University , Maastricht, The Netherlands

Irene Korstjens

c Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre for Midwifery Science , Zuyd University of Applied Sciences , Maastricht, The Netherlands

In the course of our supervisory work over the years, we have noticed that qualitative research tends to evoke a lot of questions and worries, so-called frequently asked questions (FAQs). This series of four articles intends to provide novice researchers with practical guidance for conducting high-quality qualitative research in primary care. By ‘novice’ we mean Master’s students and junior researchers, as well as experienced quantitative researchers who are engaging in qualitative research for the first time. This series addresses their questions and provides researchers, readers, reviewers and editors with references to criteria and tools for judging the quality of qualitative research papers. The second article focused on context, research questions and designs, and referred to publications for further reading. This third article addresses FAQs about sampling, data collection and analysis. The data collection plan needs to be broadly defined and open at first, and become flexible during data collection. Sampling strategies should be chosen in such a way that they yield rich information and are consistent with the methodological approach used. Data saturation determines sample size and will be different for each study. The most commonly used data collection methods are participant observation, face-to-face in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. Analyses in ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and content analysis studies yield different narrative findings: a detailed description of a culture, the essence of the lived experience, a theory, and a descriptive summary, respectively. The fourth and final article will focus on trustworthiness and publishing qualitative research.

Key points on sampling, data collection and analysis

- The data collection plan needs to be broadly defined and open during data collection.

- Sampling strategies should be chosen in such a way that they yield rich information and are consistent with the methodological approach used.

- Data saturation determines sample size and is different for each study.

- The most commonly used data collection methods are participant observation, face-to-face in-depth interviews and focus group discussions.

- Analyses of ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and content analysis studies yield different narrative findings: a detailed description of a culture, the essence of the lived experience, a theory or a descriptive summary, respectively.

Introduction

This article is the third paper in a series of four articles aiming to provide practical guidance to qualitative research. In an introductory paper, we have described the objective, nature and outline of the Series [ 1 ]. Part 2 of the series focused on context, research questions and design of qualitative research [ 2 ]. In this paper, Part 3, we address frequently asked questions (FAQs) about sampling, data collection and analysis.

What is a sampling plan?

A sampling plan is a formal plan specifying a sampling method, a sample size, and procedure for recruiting participants ( Box 1 ) [ 3 ]. A qualitative sampling plan describes how many observations, interviews, focus-group discussions or cases are needed to ensure that the findings will contribute rich data. In quantitative studies, the sampling plan, including sample size, is determined in detail in beforehand but qualitative research projects start with a broadly defined sampling plan. This plan enables you to include a variety of settings and situations and a variety of participants, including negative cases or extreme cases to obtain rich data. The key features of a qualitative sampling plan are as follows. First, participants are always sampled deliberately. Second, sample size differs for each study and is small. Third, the sample will emerge during the study: based on further questions raised in the process of data collection and analysis, inclusion and exclusion criteria might be altered, or the sampling sites might be changed. Finally, the sample is determined by conceptual requirements and not primarily by representativeness. You, therefore, need to provide a description of and rationale for your choices in the sampling plan. The sampling plan is appropriate when the selected participants and settings are sufficient to provide the information needed for a full understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Sampling strategies in qualitative research. Based on Polit & Beck [ 3 ].

Some practicalities: a critical first step is to select settings and situations where you have access to potential participants. Subsequently, the best strategy to apply is to recruit participants who can provide the richest information. Such participants have to be knowledgeable on the phenomenon and can articulate and reflect, and are motivated to communicate at length and in depth with you. Finally, you should review the sampling plan regularly and adapt when necessary.

What sampling strategies can I use?

Sampling is the process of selecting or searching for situations, context and/or participants who provide rich data of the phenomenon of interest [ 3 ]. In qualitative research, you sample deliberately, not at random. The most commonly used deliberate sampling strategies are purposive sampling, criterion sampling, theoretical sampling, convenience sampling and snowball sampling. Occasionally, the ‘maximum variation,’ ‘typical cases’ and ‘confirming and disconfirming’ sampling strategies are used. Key informants need to be carefully chosen. Key informants hold special and expert knowledge about the phenomenon to be studied and are willing to share information and insights with you as the researcher [ 3 ]. They also help to gain access to participants, especially when groups are studied. In addition, as researcher, you can validate your ideas and perceptions with those of the key informants.

What is the connection between sampling types and qualitative designs?

The ‘big three’ approaches of ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory use different types of sampling.

In ethnography, the main strategy is purposive sampling of a variety of key informants, who are most knowledgeable about a culture and are able and willing to act as representatives in revealing and interpreting the culture. For example, an ethnographic study on the cultural influences of communication in maternity care will recruit key informants from among a variety of parents-to-be, midwives and obstetricians in midwifery care practices and hospitals.

Phenomenology uses criterion sampling, in which participants meet predefined criteria. The most prominent criterion is the participant’s experience with the phenomenon under study. The researchers look for participants who have shared an experience, but vary in characteristics and in their individual experiences. For example, a phenomenological study on the lived experiences of pregnant women with psychosocial support from primary care midwives will recruit pregnant women varying in age, parity and educational level in primary midwifery practices.

Grounded theory usually starts with purposive sampling and later uses theoretical sampling to select participants who can best contribute to the developing theory. As theory construction takes place concurrently with data collection and analyses, the theoretical sampling of new participants also occurs along with the emerging theoretical concepts. For example, one grounded theory study tested several theoretical constructs to build a theory on autonomy in diabetes patients [ 4 ]. In developing the theory, the researchers started by purposefully sampling participants with diabetes differing in age, onset of diabetes and social roles, for example, employees, housewives, and retired people. After the first analysis, researchers continued with theoretically sampling, for example, participants who differed in the treatment they received, with different degrees of care dependency, and participants who receive care from a general practitioner (GP), at a hospital or from a specialist nurse, etc.

In addition to the ‘big three’ approaches, content analysis is frequently applied in primary care research, and very often uses purposive, convenience, or snowball sampling. For instance, a study on peoples’ choice of a hospital for elective orthopaedic surgery used snowball sampling [ 5 ]. One elderly person in the private network of one researcher personally approached potential respondents in her social network by means of personal invitations (including letters). In turn, respondents were asked to pass on the invitation to other eligible candidates.

Sampling is also dependent on the characteristics of the setting, e.g., access, time, vulnerability of participants, and different types of stakeholders. The setting, where sampling is carried out, is described in detail to provide thick description of the context, thereby, enabling the reader to make a transferability judgement (see Part 3: transferability). Sampling also affects the data analysis, where you continue decision-making about whom or what situations to sample next. This is based on what you consider as still missing to get the necessary information for rich findings (see Part 1: emergent design). Another point of attention is the sampling of ‘invisible groups’ or vulnerable people. Sampling of these participants would require applying multiple sampling strategies, and more time calculated in the project planning stage for sampling and recruitment [ 6 ].

How do sample size and data saturation interact?

A guiding principle in qualitative research is to sample only until data saturation has been achieved. Data saturation means the collection of qualitative data to the point where a sense of closure is attained because new data yield redundant information [ 3 ].

Data saturation is reached when no new analytical information arises anymore, and the study provides maximum information on the phenomenon. In quantitative research, by contrast, the sample size is determined by a power calculation. The usually small sample size in qualitative research depends on the information richness of the data, the variety of participants (or other units), the broadness of the research question and the phenomenon, the data collection method (e.g., individual or group interviews) and the type of sampling strategy. Mostly, you and your research team will jointly decide when data saturation has been reached, and hence whether the sampling can be ended and the sample size is sufficient. The most important criterion is the availability of enough in-depth data showing the patterns, categories and variety of the phenomenon under study. You review the analysis, findings, and the quality of the participant quotes you have collected, and then decide whether sampling might be ended because of data saturation. In many cases, you will choose to carry out two or three more observations or interviews or an additional focus group discussion to confirm that data saturation has been reached.

When designing a qualitative sampling plan, we (the authors) work with estimates. We estimate that ethnographic research should require 25–50 interviews and observations, including about four-to-six focus group discussions, while phenomenological studies require fewer than 10 interviews, grounded theory studies 20–30 interviews and content analysis 15–20 interviews or three-to-four focus group discussions. However, these numbers are very tentative and should be very carefully considered before using them. Furthermore, qualitative designs do not always mean small sample numbers. Bigger sample sizes might occur, for example, in content analysis, employing rapid qualitative approaches, and in large or longitudinal qualitative studies.

Data collection

What methods of data collection are appropriate.

The most frequently used data collection methods are participant observation, interviews, and focus group discussions. Participant observation is a method of data collection through the participation in and observation of a group or individuals over an extended period of time [ 3 ]. Interviews are another data collection method in which an interviewer asks the respondents questions [ 6 ], face-to-face, by telephone or online. The qualitative research interview seeks to describe the meanings of central themes in the life world of the participants. The main task in interviewing is to understand the meaning of what participants say [ 5 ]. Focus group discussions are a data collection method with a small group of people to discuss a given topic, usually guided by a moderator using a questioning-route [ 8 ]. It is common in qualitative research to combine more than one data collection method in one study. You should always choose your data collection method wisely. Data collection in qualitative research is unstructured and flexible. You often make decisions on data collection while engaging in fieldwork, the guiding questions being with whom, what, when, where and how. The most basic or ‘light’ version of qualitative data collection is that of open questions in surveys. Box 2 provides an overview of the ‘big three’ qualitative approaches and their most commonly used data collection methods.

Qualitative data collection methods.

What role should I adopt when conducting participant observations?

What is important is to immerse yourself in the research setting, to enable you to study it from the inside. There are four types of researcher involvement in observations, and in your qualitative study, you may apply all four. In the first type, as ‘complete participant’, you become part of the setting and play an insider role, just as you do in your own work setting. This role might be appropriate when studying persons who are difficult to access. The second type is ‘active participation’. You have gained access to a particular setting and observed the group under study. You can move around at will and can observe in detail and depth and in different situations. The third role is ‘moderate participation’. You do not actually work in the setting you wish to study but are located there as a researcher. You might adopt this role when you are not affiliated to the care setting you wish to study. The fourth role is that of the ‘complete observer’, in which you merely observe (bystander role) and do not participate in the setting at all. However, you cannot perform any observations without access to the care setting. Such access might be easily obtained when you collect data by observations in your own primary care setting. In some cases, you might observe other care settings, which are relevant to primary care, for instance observing the discharge procedure for vulnerable elderly people from hospital to primary care.

How do I perform observations?

It is important to decide what to focus on in each individual observation. The focus of observations is important because you can never observe everything, and you can only observe each situation once. Your focus might differ between observations. Each observation should provide you with answers regarding ‘Who do you observe?’, ‘What do you observe’, ‘Where does the observation take place?’, ‘When does it take place?’, ‘How does it happen?’, and ‘Why does it happen as it happens?’ Observations are not static but proceed in three stages: descriptive, focused, and selective. Descriptive means that you observe, on the basis of general questions, everything that goes on in the setting. Focused observation means that you observe certain situations for some time, with some areas becoming more prominent. Selective means that you observe highly specific issues only. For example, if you want to observe the discharge procedure for vulnerable elderly people from hospitals to general practice, you might begin with broad observations to get to know the general procedure. This might involve observing several different patient situations. You might find that the involvement of primary care nurses deserves special attention, so you might then focus on the roles of hospital staff and primary care nurses, and their interactions. Finally, you might want to observe only the specific situations where hospital staff and primary care nurses exchange information. You take field notes from all these observations and add your own reflections on the situations you observed. You jot down words, whole sentences or parts of situations, and your reflections on a piece of paper. After the observations, the field notes need to be worked out and transcribed immediately to be able to include detailed descriptions.

Further reading on interviews and focus group discussion.

Qualitative data analysis.

What are the general features of an interview?

Interviews involve interactions between the interviewer(s) and the respondent(s) based on interview questions. Individual, or face-to-face, interviews should be distinguished from focus group discussions. The interview questions are written down in an interview guide [ 7 ] for individual interviews or a questioning route [ 8 ] for focus group discussions, with questions focusing on the phenomenon under study. The sequence of the questions is pre-determined. In individual interviews, the sequence depends on the respondents and how the interviews unfold. During the interview, as the conversation evolves, you go back and forth through the sequence of questions. It should be a dialogue, not a strict question–answer interview. In a focus group discussion, the sequence is intended to facilitate the interaction between the participants, and you might adapt the sequence depending on how their discussion evolves. Working with an interview guide or questioning route enables you to collect information on specific topics from all participants. You are in control in the sense that you give direction to the interview, while the participants are in control of their answers. However, you need to be open-minded to recognize that some relevant topics for participants may not have been covered in your interview guide or questioning route, and need to be added. During the data collection process, you develop the interview guide or questioning route further and revise it based on the analysis.

The interview guide and questioning route might include open and general as well as subordinate or detailed questions, probes and prompts. Probes are exploratory questions, for example, ‘Can you tell me more about this?’ or ‘Then what happened?’ Prompts are words and signs to encourage participants to tell more. Examples of stimulating prompts are eye contact, leaning forward and open body language.

Further reading on qualitative analysis.

What is a face-to-face interview?

A face-to-face interview is an individual interview, that is, a conversation between participant and interviewer. Interviews can focus on past or present situations, and on personal issues. Most qualitative studies start with open interviews to get a broad ‘picture’ of what is going on. You should not provide a great deal of guidance and avoid influencing the answers to fit ‘your’ point of view, as you want to obtain the participant’s own experiences, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. You should encourage the participants to speak freely. As the interview evolves, your subsequent major and subordinate questions become more focused. A face-to-face or individual interview might last between 30 and 90 min.

Most interviews are semi-structured [ 3 ]. To prepare an interview guide to enhance that a set of topics will be covered by every participant, you might use a framework for constructing a semi-structured interview guide [ 10 ]: (1) identify the prerequisites to use a semi-structured interview and evaluate if a semi-structured interview is the appropriate data collection method; (2) retrieve and utilize previous knowledge to gain a comprehensive and adequate understanding of the phenomenon under study; (3) formulate a preliminary interview guide by operationalizing the previous knowledge; (4) pilot-test the preliminary interview guide to confirm the coverage and relevance of the content and to identify the need for reformulation of questions; (5) complete the interview guide to collect rich data with a clear and logical guide.

The first few minutes of an interview are decisive. The participant wants to feel at ease before sharing his or her experiences. In a semi-structured interview, you would start with open questions related to the topic, which invite the participant to talk freely. The questions aim to encourage participants to tell their personal experiences, including feelings and emotions and often focus on a particular experience or specific events. As you want to get as much detail as possible, you also ask follow-up questions or encourage telling more details by using probes and prompts or keeping a short period of silence [ 6 ]. You first ask what and why questions and then how questions.

You need to be prepared for handling problems you might encounter, such as gaining access, dealing with multiple formal and informal gatekeepers, negotiating space and privacy for recording data, socially desirable answers from participants, reluctance of participants to tell their story, deciding on the appropriate role (emotional involvement), and exiting from fieldwork prematurely.

What is a focus group discussion and when can I use it?

A focus group discussion is a way to gather together people to discuss a specific topic of interest. The people participating in the focus group discussion share certain characteristics, e.g., professional background, or share similar experiences, e.g., having diabetes. You use their interaction to collect the information you need on a particular topic. To what depth of information the discussion goes depends on the extent to which focus group participants can stimulate each other in discussing and sharing their views and experiences. Focus group participants respond to you and to each other. Focus group discussions are often used to explore patients’ experiences of their condition and interactions with health professionals, to evaluate programmes and treatment, to gain an understanding of health professionals’ roles and identities, to examine the perception of professional education, or to obtain perspectives on primary care issues. A focus group discussion usually lasts 90–120 mins.

You might use guidelines for developing a questioning route [ 9 ]: (1) brainstorm about possible topics you want to cover; (2) sequence the questioning: arrange general questions first, and then, more specific questions, and ask positive questions before negative questions; (3) phrase the questions: use open-ended questions, ask participants to think back and reflect on their personal experiences, avoid asking ‘why’ questions, keep questions simple and make your questions sound conversational, be careful about giving examples; (4) estimate the time for each question and consider: the complexity of the question, the category of the question, level of participant’s expertise, the size of the focus group discussion, and the amount of discussion you want related to the question; (5) obtain feedback from others (peers); (6) revise the questions based on the feedback; and (7) test the questions by doing a mock focus group discussion. All questions need to provide an answer to the phenomenon under study.

You need to be prepared to manage difficulties as they arise, for example, dominant participants during the discussion, little or no interaction and discussion between participants, participants who have difficulties sharing their real feelings about sensitive topics with others, and participants who behave differently when they are observed.

How should I compose a focus group and how many participants are needed?

The purpose of the focus group discussion determines the composition. Smaller groups might be more suitable for complex (and sometimes controversial) topics. Also, smaller focus groups give the participants more time to voice their views and provide more detailed information, while participants in larger focus groups might generate greater variety of information. In composing a smaller or larger focus group, you need to ensure that the participants are likely to have different viewpoints that stimulate the discussion. For example, if you want to discuss the management of obesity in a primary care district, you might want to have a group composed of professionals who work with these patients but also have a variety of backgrounds, e.g. GPs, community nurses, practice nurses in general practice, school nurses, midwives or dieticians.

Focus groups generally consist of 6–12 participants. Careful time management is important, since you have to determine how much time you want to devote to answering each question, and how much time is available for each individual participant. For example, if you have planned a focus group discussion lasting 90 min. with eight participants, you might need 15 min. for the introduction and the concluding summary. This means you have 75 min. for asking questions, and if you have four questions, this allows a total of 18 min. of speaking time for each question. If all eight respondents participate in the discussion, this boils down to about two minutes of speaking time per respondent per question.

How can I use new media to collect qualitative data?